Abstract

Introduction:

The etiology of diabetes is mainly attributed to insulin deficiency due to the lack of β cells (type 1), or to insulin resistance that eventually results in β cell dysfunction (type 2). Therefore, an ultimate cure for diabetes requires the ability to replace the lost insulin-secreting β cells. Strategies for regenerating β cells are under extensive investigation.

Areas covered:

Herein, the authors first summarize the mechanisms underlying embryonic β cell development and spontaneous adult β cell regeneration, which forms the basis for developing β cell regeneration strategies. Then the rationale and progress of each β cell regeneration strategy is reviewed. Current β cell regeneration strategies can be classified into two main categories: in vitro β cell regeneration using pluripotent stem cells and in vivo reprogramming of non-β cells into β cells. Each has its own advantages and disadvantages.

Expert opinion:

Regenerating β cells has shown its potential as a cure for the treatment of insulin-deficient diabetes. Much progress has been made, and β cell regeneration therapy is getting closer to a clinical reality. Nevertheless, more hurdles need to be overcome before any of the strategies suggested can be fully translated from bench to bedside.

Keywords: β cell regeneration, diabetes, stem cells, reprogramming

1. Introduction

Diabetes is a common chronic disease marked by high blood glucose, which can cause serious complications if not controlled. According to the National Diabetes Statistics Report, diabetes affects 30.3 million people in the United States in 2015, which is ~9.4% of the total population, with a trend of increasing prevalence1. The Etiology of diabetes is mainly attributed to the lack of insulin-producing β cells that are located in pancreatic islets (type 1 diabetes, T1D) or as a result of insulin resistance that eventually leads to β cell failure (type 2 diabetes, T2D). Therefore, an ultimate cure for diabetes requires the ability to replace the lost β cells, not just the hormone insulin. Indeed, replenishing the lost β cells in T1D patients via islet transplantation has shown remarkable benefits in stabilizing blood glucose control, to a degree that is vastly superior to insulin therapy2–5. Specifically, glycemic control is smoother and hypoglycemia less prevalent in the islet recipients, even though they might not have achieved insulin independence2, 5, 6.

Despite many progresses on islet transplantation, the major challenge is a limited supply of human islets—a large number of pancreatic islets are needed to achieve insulin-independence, but the available pancreas donors are limited. This has significantly limited the use of islet transplantation for a broader patient range. Therefore, alternative strategies to generate functional β cells for replacement therapy are under intensive investigation on both basic and translational aspects of diabetes research. In this article, we review the progresses made thus far, and discuss the pros and cons of each strategy.

2. Mechanisms of β cell development and β cell regeneration

2.1. Embryonic development of β cells

Native β cells are located in the islets of Langerhans in pancreas, co-residing with 4 additional islet cell types which include the glucagon-producing α cells, somatostatin-producing δ cells, ghrelin-producing ε cells, and pancreatic polypeptide-producing PP cells. These islets form the endocrine compartment of the pancreas where islet cells produce and secrete hormones into blood stream. The pancreas also contains an exocrine compartment, which is composed of acinar cells that produce and secrete digestive enzymes into pancreatic ducts. The exocrine compartment comprises 95% of the total pancreatic mass, whereas the endocrine compartment (islets) only represents about 5% of the pancreatic mass.

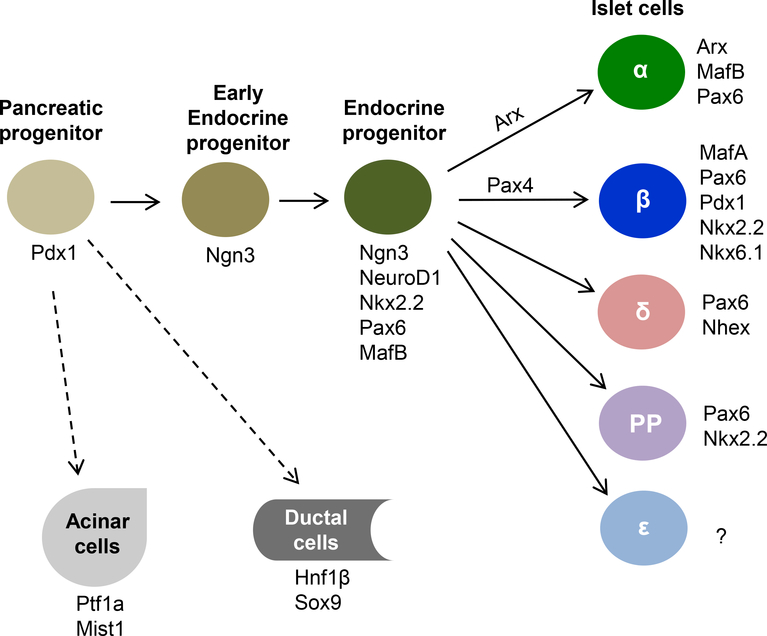

The formation of β cells during embryonic development is controlled by sequential activation of a series of transcription factors7–**12. Illustrated in Fig. 1 are the major transcription factors involved in islet cell lineage specifications. The first critical one is pancreatic and duodenal homeobox factor (Pdx1, also called IPF1 /STF-1), which appears to be the determining factor for pancreas lineage since Pdx1-deficient mice fail to develop a pancreas13–15 and a human patient with Pdx1 mutation shows pancreas agenesis16. Indeed, a detailed genome-wide analysis of transcription factor expression in early developing pancreas shows that Pdx1+ multipotent progenitors, which are located at the distal tips of the branching pancreatic tree, also express the transcription factor Ptf1a, and they have the capacity to proliferate and differentiate into all pancreatic cells including exocrine, endocrine and duct cells17. Additional studies have shown Pdx1 is essential for β cell differentiation and its functional maintenance in both rodents and human18–21. Consistent with these roles, Pdx1 is expressed in pancreatic precursor cells during pancreas development and its expression becomes restricted to β cells in mature pancreas.

Figure 1:

Diagram of major transcription factors involved in lineage specifications of pancreatic cells during embryonic development.

The second key transcription factor is neurogenin 3 (Ngn3), a member of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family. Ngn 3 is the main regulator for the development of endocrine cells because its deficiency prevents the generation of endocrine cells in the pancreas and intestine22–24. During early pancreatic branching morphogenesis, Ngn3+ cells are observed exclusively in the trunk of the branches17. Further studies suggest that Ngn3 expression is tightly regulated to maintain the proper size and cell composition of the endocrine pancreas, and its function is highly dependent on its temporal expression during pancreas development25, 26.

Islet cell lineage is further specified by expression of other transcription factors such as NeuroD1, Nkx2.2, and Pax6 —genetic deletion of these proteins results in small disorganized islets, and decreased numbers of all endocrine lineages10, **12, 27–29. The endocrine cells eventually differentiate into different islet cell types by expressing cell-type specific transcription factors. For instance, expression of Arx leads to the formation of glucagon-producing α cells, expression of Pax4 triggers the differentiation of β cells, whereas loss of both Arx and Pax4 promotes the formation of somatostatin-producing δ cells30, 31. Differentiation of β cells is also coupled with a loss of MafB expression and induction of MafA expression32. The mature β cells express several key transcription factors including MafA, Nkx2.2, Nkx6.1, Pax6 and Pdx1, all of which are essential for maintaining β cell identity and function18, 32–35.

2.2. Spontaneous β cell regeneration and sources of new β cells

As terminally differentiated cells, the pancreatic β cells need to be replenished for normal tissue turnover under physiological conditions. Therefore, β cell regeneration occurs naturally throughout adult life. In search of strategies to regenerate β cells, scientists have undertaken numerous studies to understand how β cell regeneration occurs in vivo. To date, three main mechanisms (cellular sources) for β cell regeneration have been identified, which include β cell neogenesis from progenitor cells*36–39, replication of pre-existing β cells*40–42, and transdifferentiation from other islet cell types including α and δ cells*43–45. It appears that all three mechanisms are responsible for spontaneous and adaptive β cells regeneration, whereas the significance of each pathway depends on the nature of the situation*36, *43, 46.

2.2.1. β cell replication as a major mechanism to accommodate normal β cell turnover and adaptive expansion in response to increased physiological needs

Among many studies in search of the origins of new β cells is a pioneering lineage tracing study published by Dor et al in 2004*40. Using a transgenic mouse model in which the pre-existing β cells are pre-labelled, the authors have demonstrated that the terminally differentiated β cells hold a significant proliferative capacity, and their self-duplication plays an important role in normal tissue turnover and following partial pancreatectomy. Since then, β cell replication has been confirmed by many other studies in various systems including in isolated human islets and diabetic patients41, 42, 47–49. In addition, using DNA-labelling-based lineage tracing technique that involves the use of two different thymidine analogs, Teta et al have shown that adult β cells have equal proliferation potential—most β cells divide eventually, with a replication refractory period that prevents them from immediate re-dividing41.

Another interesting question is whether the capacity of β cell proliferation is affected by age. A detailed examination by Rankin and Kushner has shown that basal β cell proliferation significantly decreases with aging, and mice that are 12-month or older have minimal adaptive β cell proliferation capacity in response to partial pancreatectomy, or low-doses of streptozotocin49. On the other hand, in an islet transplantation study, after the donor islets isolated from young (3 months old) or old (24 months old) mice are transplanted into diabetic recipients, β cells of the young and old donor islets appear to have similar proliferation capacity50. Since the recipient mice used in the study are at young age (~3 months old), it is likely that the physiological environment has had an impact on the proliferation capacity of the donor β cells.

2.2.2. β cell regeneration from progenitor cells in response to pancreatic injury

The presence of islet progenitor cells and its role in islet cell regeneration has been proposed based on many observations. For instance, islet (β cell) neogenesis is observed following >70% pancreatectomy or ductal ligation in rodents39, 46, 51; insulin+ cells are occasionally detected in the pancreatic ducts and up-regulated under certain circumstances in humans52, 53. With the development of lineage-tracing and genetic labeling techniques, the role of progenitor cells in adult β cell regeneration has now been confirmed by many studies. Despite some controversies, it is reasonable to conclude that there are two pools of islet cell progenitors: those located in pancreatic ducts and those within pancreatic islets. Guided by the expression of Ngn3, the earliest endocrine cell-specific transcription factor, Xu et al has demonstrated that multipotent progenitor cells exist along the ductal lining of the pancreas in adult mice, and they can be activated to differentiate into β cells following partial ductal ligation*36. Similarly, in adult rats, after 90% pancreatectomy, extensive branching morphogenesis emerges from the common pancreatic duct, which forms regenerating foci to subsequently give rise to both endocrine and exocrine tissues, essentially mimicking embryonic pancreatic development process39. Formation of new β cells from ductal cells is also observed in adult mice that overexpress TGF-β receptor54. Further investigation suggests that the pancreatic ductal cells first de-differentiate to become multipotent progenitor cells, and then re-differentiate into various cell types including β cells39. Moreover, it appears that there are progenitor cell niches located in the pancreatic ductal glands (i.e., the epithelial compartment of the mesenchymal structures surrounding pancreatic ducts)55, 56. These cells are identified as heterogeneous populations of OCT4-/Pdx1+/Sox9+ cells, and they are associated with pancreatic ducts and occasionally localized in continuity with islet clusters.

In addition to pancreatic ductal cells, islet progenitor cells have also been found within the islets. The first line of evidence comes from in vitro culture of purified islets, in which multipotent progenitor cells can be isolated and differentiated into β-like cells57–60. Additional evidence comes from the observation that β cell regeneration occurs within existing islets following streptozotocin-induced β cell destruction61, 62. However, one argument is that those progenitor cells may have arisen from de-differentiation or induced by artificial factors of in vitro culture59, 63. In order to have a definitive answer, Liu et al have performed a lineage-tracing study, and their results show that the islets indeed contain precursor cells that can be differentiated into β cells after streptozotocin-induced β cell damage37. Moreover, after comparing the number of islet precursor-cells derived β cells in mice of different ages (3, 6, and 12 months old), the authors conclude that precursor cells play an important role in β cell renewal during aging. This is consistent with an earlier study showing β cell replication is severely restricted in aged mice49. Taken together, despite some discrepancies in these studies, it is reasonable to conclude that, while β cell duplication appears to be sufficient for normal tissue turnover and slow mass expansion, islet progenitor cells are needed for rapid β cell regeneration during major pancreatic injuries and for β cell renewal in mice with advanced age*36, 37, 39.

Furthermore, van der Meulen et al have recently reported an interesting discovery—a population of immature (virgin) β cells are present throughout life in both mice and human islets, and they are located at a specialized area in the islet periphery, namely neogenic niche64. These virgin β cells express insulin, but not other key β cell markers; they are incapable of sensing glucose, and are functionally immature. They appear to be at an intermediate stage between α and β cells, and are a lifelong source of new β cells. Since these cells have a nearly-determined fate, they are essentially β cell progenitors.

2.2.3. β cell regeneration from other islet cells via transdifferentiation following extreme β cell loss

Another interesting hypothesis regarding β cell regeneration is transdifferentiation of other cell types such as acinar cells, ductal cells, or other islet cells in adult pancreas. This hypothesis has gained critical support in an elegant and comprehensive study by Thorel et al*43. In the study, the authors have demonstrated that β cell regeneration occurs after acute, near-total β cell ablation, and a large fraction of the regenerated β cells are derived from pre-existing α cells that are located in the pancreatic islets. Further study has shown the capacity of α-to-β cell conversion after extreme β cell loss is not restricted by age—the capacity is maintained from puberty through adulthood, and in aged individuals45. Interestingly, the somatostatin-producing δ can also be transdifferentiated into β cells, especially in young mice (before puberty) after β cell loss. The δ-to-β conversion in juveniles appears to involve dedifferentiation, proliferation, and re-differentiation, and is partly dependent on FoxO1 expression45. On the other hand, it should be noted that, lineage-tracing of exocrine cells, specifically acinar and ductal cells, shows that exocrine-to-endocrine transdifferentiation is undetectable in adult mice, although it can be detected during embryonic development in uninjured pancreas65. Taken together, β cells can be regenerated spontaneously through transdifferentiation of other endocrine cells in adult pancreas, especially after extreme β cell loss.

3. Regenerating β cells from stem cells—in vitro β cell regeneration

An ultimate cure for T1D requires replenishment of the lost β cells. Although islet transplantation has proven its efficacy in this regard, its use in clinic is severely limited due to the shortage of human islet donors. During the past decade, a great deal of effort has been invested in the search of alternative means to regenerate functional β cells. One of the most attractive and logic strategies is to generate functional β cells from pluripotent stem cells in culture. Pluripotent stem cells have two key features: their ability to proliferate indefinitely and their ability to differentiate into any somatic cells upon induction. Therefore, regenerating β cells from stem cells in vitro, if succeeded, would provide unlimited supply for β cell replacement therapy. After decades of exploration, significant progresses have been made over the past few years. Promising results are derived from several stem cell sources, including pancreatic stem cells, embryonic stem cells (ESCs), and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)66–69.

3.1. Regenerating β cells from pancreatic stem cells

Pancreatic tissue has certain capacity to regenerate following injury such as partial pancreatectomy and ductal ligation. Therefore, many studies have focused on searching for pancreatic stem cells and developing protocols to differentiate them into functional β cells. Some early attempts are directed towards multipotent progenitor cells within islets, in which purified islets are cultured under various conditions so that the potential progenitor cells can be enriched and differentiated into islet cells57, 59, 63. For instance, Lechner et al have developed a 3-step culture protocol for dispersed human islet cells that result in the expansion of islet cells in vitro and the differentiation of insulin-secreting cell clusters59. In their protocol, serum-free medium, high glucose, and matrigel (3D culture system) appear to be essential for the formation of islet-like clusters and endocrine differentiation. The results are consistent with a later in vivo lineage-tracing study showing the presence of islet progenitor cells in mice37. On the other hand, it has been shown that human islet cells in culture may dedifferentiate into a more primitive and proliferative epithelial phenotype that can expand in vitro, probably through a process called epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)57, 58, 63, 70. Because the starting material in the human islet cultures contains all types of cells, it is difficult to determine whether the β-like cells are generated from pre-existing progenitor cells or from the dedifferentiated cells—it is highly likely that they are from both.

Another major source of pancreatic stem cells appears to be the pancreatic ducts. It has been noted that budding of new islets from ductal epithelium is not only a feature of embryonic pancreatic development, but also happens during pancreatic regeneration following pancreatic injury in adults. Therefore, many efforts have been taken to regenerate β cells from cultured pancreatic ductal cells38, 69, 71. One of the first successful attempts comes from Ramiya et al, in which the authors have isolated ductal epithelial cells from non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice, cultured them in vitro, and differentiated them into islet-like structures72. When implanted into the kidney capsule, these in vitro-generated islets are able to reverse hyperglycemia of the diabetic mice. The duct-derived stem cells are able to survive long-term (>3 years) in culture with regular passaging, and maintain their ability to be differentiated into islet-like structures. In the meantime, Bonner-Weir et al have developed a matrigel-based 3D culturing system, successfully expanded adult human ductal tissue, and differentiated them into islet-like clusters that secreted insulin in response to glucose stimulation*73. This is further supported by a study showing CK19+ nonendocrine epithelial cells of adult human pancreas can be differentiated into β cells in vitro74.

Since then, many progresses have been made in optimizing the in vitro culture condition and in improving the differentiation protocol. Purification of duct-derived stem cells from human pancreas is improved with the identification of membrane proteins that are specific for these cells such as CA19–9 and CD133, allowing the cells to be purified by flow cytometry75–77. Studies have reported that growth factors such as EGF, HGF, and KGF stimulate the proliferation of human pancreatic-duct-derived stem cells*73, 78, 79. Nicotinamide and dexamethasone have also been shown to be beneficial for ductal cell growth in culture80. With regard to differentiation of these cells into β cells, it appears that pancreas-derived progenitor cells from either islets or ducts have the capacity to spontaneously differentiate into endocrine cells59, *73. In addition, the purified CA19–9+ ductal cells shows increased capacity to spontaneously differentiate into insulin-producing β cells after co-cultured with pancreatic stromal cells77, 81. Differentiation of CD133+ cells can be greatly improved by overexpressing β cell specific transcription factors such as Pdx1, MafA, Ngna3, and Pax676.

3.2. Regenerating β cells from embryonic stem cells

Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) are valuable sources for cell replacement therapies of all types of diseases because they are highly proliferative, and have the capacity to differentiate into any cell types under appropriate induction in a manner similar to embryonic development of the cells. To date, efforts on regenerating functional β cells from hESCs have achieved a few key breakthroughs, and lead the way to clinical trials67, 82.

The first critical breakthrough is the development of a differentiation process that converts hESCs to endocrine cells capable of synthesizing all pancreatic hormones including insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, pancreatic peptide and ghrelin83. The process is designed to mimic pancreatic organogenesis by directing cells through stages resembling definitive endoderm, gut-tube endoderm, pancreatic endoderm, and endocrine precursors, which is achieved by sequential stimulation or inhibition of key signaling pathways with small molecules and growth factors. The hESCs-derived islet-like cells have insulin content close to adult β cells, but functionally they are more like fetal β cells because they show minimal insulin secretion in response to glucose stimulation83, 84. However, using similar protocols with some modifications, the hESCs-derived pancreatic endoderm cells can continue to differentiate in vivo and become mature, glucose-responsive endocrine cells when implanted in mice85, 86. Human C-peptide becomes detectable in the recipient mice 30 days after transplantation, persist for more than 3 months, and can reach to the level comparable to that in mice transplanted with 3000 human islets. Immunofluorescence staining shows the implanted hESCs-derived β cells express the critical β cell transcription factors, and have mature endocrine secretory granules. More importantly, transplantation of these hESCs-derived endocrine precursor cells protects the mice from streptozotocin-induced, insulin-deficient diabetes.

Another key breakthrough is the generation of functional β cells from hESCs in vitro in a scalable and reproducible fashion**87. Although previous studies demonstrate that in vitro hESCs-derived pancreatic progenitor cells can be transplanted to treat T1D because they have the capacity to spontaneously differentiate into functional β cells in vivo, it takes at least 4 weeks for them to show any detectable therapeutic effects85, 86. Building on the studies showing pancreatic progenitors could be further differentiated in vitro into some insulin+ cells along with polyhormonal cells83, 84, 88, 89, Pagliuca et al in Melton group have developed an in vitro differentiation protocol that successfully induces hESCs (and induced pluripotent stem cells, iPSCs) into functional human β cells, namely SC-β cells (for stem cell-derived β cells)**87. This protocol employs sequential culture steps and involves unique combination of many factors that affect various signaling pathways, including signaling by wnt, activin, hedgehog, EGF, TGFβ, thyroid hormone, and retinoic acid, as well as γ-secretase inhibition. The whole process takes about 4–5 weeks, and the in vitro generated SC-β cells have essentially the same property as the bona fide β cells. When transplanted into T1D mice, these cells ameliorate hyperglycemia immediately with the same efficacy as transplantation of human islets. Taken together, these studies support the idea that hESCs can be used to regenerate functional β cells, providing an alternative source to cadaveric islets for treating insulin-deficient diabetes.

A major obstacle in translating the discoveries into clinical use, however, is safety concern: the high proliferative nature of stem cells, if not reined in by terminal differentiation, can lead to tumor formation in vivo. Indeed, transplantation of hESCs-derived pancreatic endocrine precursor cells into mice has resulted in the formation of teratomas in 2.2% of recipient mice85. One strategy to mitigate the problem is to place the transplanted cells in an encapsulation device—this will not only allow the transplanted cells to be removed should they grow into tumors, but also protect them from immune attack. In the past few years, key progresses are made in the development of encapsulation devices that allow hESCs-derived precursor cells to differentiate and function in vivo90–93. Most notably, the microencapsulation device, TheraCyte, featuring a billaminar polytetrafluoreoethylene (PTFE) membrane system, has shown full capacity to allow the maturation and function of hESCs-derived pancreatic progenitors inside the device following transplant into mice, resulting in the reversal of diabetes within 3 months90, 91, 93. Vegas et al has encapsulated stem cell-derived β cells with alginate derivative-based polymers, and has successfully implanted them into immune-competent mice without immunosuppression, achieving long-term glycemic control in diabetic mice*92.

These progresses provide basis for the first clinical trial (phase I/II) using hESCs-derived pancreatic progenitors to treat T1D patients (Clinical trials identifier: NCT02239354, by ViaCyte, Inc). The trial is currently ongoing, and the results will provide information on the safety, tolerability and therapeutic efficacy of encapsulated hESCs-derived β cells in T1D patients.

3.3. Regenerating β cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells

The induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are generated by reprogramming adult somatic cells (fibroblasts or blood leukocytes) to a pluripotent state through forced expression of several transcription factors such as Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and cMyc94, 95. The in vitro SC-β cell differentiation protocol developed in Melton lab also applies to human iPSCs as they have tested two human iPSC cell lines (hiPSC-1 and hiPSC-2) in addition to a human ESC line (HUES8)**87. The successful differentiation of hiPSCs into SC-β cells opens the door to individualized regenerative medicine in which the patient’s own cells can be used to regenerate their lost β cells, minimizing immune rejection of the transplanted cells.

Studies aiming at regenerating β cells from T1D-derived iPSCs have shown major success. For instance, Millman et al have reported the generation of functional β cells from the iPSCs that are generated from the skin fibroblast of T1D patients*96. The T1D iPSCs-derived SC-β cells appear to have the same property as normal human iPSCs-derived SC-β cells, and both function the same way as mature bona fide β cells: expressing β cell markers, responding to glucose both in vitro and in vivo, and preventing alloxan-induced diabetes in mice. These results support the potential use of the autologous cells for β cell replacement therapy in the treatment of T1D patients.

4. Reprogramming non-β cells into β cells—in vivo β cell regeneration

Reprogramming one type of specialized cells into another without reverting to pluripotent status, i.e., transdifferentiation, is an interesting and challenging strategy that has been explored for β cell regeneration. Despite the challenges, some progresses have been made using liver cells, gut cells, acinar cells, and pancreatic α cells, mostly in preclinical cell or mouse studies.

4.1. Reprogramming liver cells into β cells

Liver is one of the largest organs in the body, and contains cells with a high level of proliferation potential and functional redundancy97. In addition, the liver and the pancreas are both derived from the primitive ventral endoderm during organogenesis, suggesting their cell lineages may be converted by reprogramming strategies. On this basis, liver cells become one of the first reprogramming targets for β cell regeneration in vivo. It has been shown that, when delivered into mouse liver by adenoviral vectors, the transcription factor Pdx1 activates insulin expression in the liver, causing a substantial increase in plasma insulin levels, which in turn ameliorates hyperglycemia of diabetic mice*98. The efficiency of liver-to-β cell reprogramming is improved by co-treatment of liver cells with Pdx1 and other transcription factors including Nkx6.1, Pax4 and MafA*98–100. Using human primary liver cells, Berneman-Zeitouni et al have discovered that sequential application of transcription factors in the order of Pdx1, Pax4, and MafA results in the formation of sustantially more mature β cells100. This indicates liver-to-β cell transdifferentiation is a progressive and hierarchical process. Together, these studies support that transdifferentiation using proper transcription factors is a viable strategy to induce β cells regeneration from liver cells.

4.2. Reprogramming gastrointestinal tract cells into β cells

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract epithelium is a highly regenerative tissue. It contains a large number of adult stem/progenitor cells that constantly generate epithelial cells including hormone-secreting enteroendocrine cells. More importantly, embryonic development of gut enteroendocrine and pancreatic endocrine cells are related, and they share common critical factors such as Ngn322, 23. Therefore, GI tract tissues have been explored as reprogramming target for β cell regeneration101–103. Chen et al has shown that transient expression of Ngn3, Pdx1, and MafA in mouse intestine induces rapid conversion of intestinal crypt cells into endocrine cells that coalesce into “neoislets” below the crypt base*102. Similarly, expression of these factors in human intestinal “organoids” stimulates the conversion of the intestinal epithelial cells into β-like cells. Moreover, co-expression of the three transcription factors (Ngn3, Pdx1, and MafA) in antral stomach has also been shown to reprogram the epithelial cells into insulin+ cells that respond to glucose stimulation and are able to ameliorate hyperglycemia in diabetic mice for at least 6 months103. In addition, it has been found that ablation of one transcription factor, FoxO1, in the enteroendocrine cells is found to result in the formation of β-like cells in the gut, and these cells are able to reverse streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemia101. In summary, reprogramming the GI tract epithelial cells into β cells can be achieved by manipulation of transcription factors.

4.3. Reprogramming pancreatic exocrine cells into β cells

The pancreatic exocrine cells, specifically acinar cells, are located in the native environment of β cells; they are abundant; and they share pancreatic progenitors with β cells (i.e., pancreatic endoderm) during embryonic development. In addition, as discussed above, pancreatic progenitor cells exist in pancreatic exocrine including acinar and ductal tissues. Therefore, the acinar cells are logic and attractive targets to be reprogrammed into β cells. In search of an appropriate acinar-to-β reprogramming protocol, Zhou et al have attempted to ectopically express different combinations of key transcription factors in the mouse pancratic exocrine**104. Their results show that a combination of Ngn3, Pdx1 and MafA, all of which are essential for embryonic β cell development, can reprogram acinar cells into functional β cells in vivo. The regenerated β cells have similar size, shape, and ultrastructure to that of endogenous islet β cells, and they are able to ameliorate hyperglycemia in T1D mice. Interestingly, further studies show that Ngn 3 alone is able to convert acinar cells into δ-like cells, whereas a combination of Ngn3 and MafA reprograms the acinar cells into α-like cells105. These studies suggest that acinar cells can be reprogrammed into three endocrine cell subtypes via forced expression of different transcription factors.

In addition to transcription factors, cytokines such as EGF and ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) have also been shown to induce acinar-to-β cell reprogramming*106. Specifically, co-administration of EGF and CNTF into the peritoneum of alloxan-induced T1D mice stimulates β cell regeneration and restores normoglycemia. Further lineage-tracing experiments demonstrate that the new β cells are originated from existing acinar cells. The cytokines-induced acinar-to-β cell conversion appears to involve Stat3 signaling pathway and re-expression of the transcription factor Ngn3.

4.4. Reprogramming pancreatic α cells into β cells

Another reprogramming target for β cell regeneration is the pancreatic α cells. Both α and β cells reside in the same pancreatic islets; both respond to blood glucose variations; and they share a similar differentiation pathway during embryonic development until very late stage10, **12 (Fig. 1). Therefore, reprogramming α cells into β cells is expected to be achieved by the least manipulation of transcription factors compared to that with liver, gut or pancreatic exocrine cells.

Indeed, the paired-domain containing transcription factor, Pax4, appears to have the capacity to convert α cells into β cells. Studies have shown Pax4 is mainly expressed in pancreatic islets during embryonic development, and it plays critical roles in the formation of islet cell progenitors and subsequent β- and δ-cell differentiation30, 107. Genetic knockout of Pax4 results in mice without mature β cells or δ-cells, but with substantially more α cells107, demonstrating Pax4 is essential in determining β cell lineage. This is further confirmed by genetic Pax4 knock-in studies, which have shown forced Pax4 expression in α cells converts them into β cells108, 109. In humans, Pax4 mutations are found in early-onset T2D patients and maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY)110–112.

On another note, ectopic Pax4 expression in α cells via genetic knock-in results in adverse effects: continuous α-to-β cell conversion leads to β cell hyperplasia and glucagon deficiency108, 109. Therefore, a more controllable α-to-β reprogramming strategy is needed for therapeutic purpose. Recently, Zhang et al explored a gene therapy strategy, in which Pax4 is delivered into α cells by an adenoviral vector*113. The authors have shown Pax4 gene transfer into a clonal α cell line, αTC1.9, induces insulin expression, and reduces glucagon expression. In addition, Pax4 gene transfer into primary human islets has resulted in significantly more insulin+/glucagon+ bi-hormonal cells, arguing for a possible transition between α and β cells. Although the evidence is indirect and circumstantial without lineage tracing, the results support the hypothesis that manipulating a single transcription factor, Pax4, via appropriate gene delivery, is a viable strategy for the treatment of insulin deficient diabetes.

Alternatively, since the transcription factor Arx is essential for the development of α cells, and it plays opposing roles to Pax4 in α vs β cell lineage determination, α-to-β reprogramming may be achieved via Arx inhibition. Indeed, recently Li et al have established a cell-line based screening system to identify small molecules that inhibit Arx and cause α-to-β cell transdifferentiation*114. By screening thorugh a library of approved drugs with the system, the authors have discovered the anti-malarial drug, artemisinin, as a functional Arx inhibitor. Further examinations have shown that artemininin is able to induce α-to-β conversion in various systems including cultured αTC1 cells, primary human islets, as well as in vivo in zebrafish and rodent models. Mechanistic studies suggest artemininin enhances GABAA receptor signaling by stabilizing its binding protein gephrin, which subsequently inhibits glucagon secretion, induces Arx to relocate from nucleus to cytoplasm and impairs α cell identity, eventually leading them to take β cell identity*114. Clearly, the findings in this study represent a new regime for reprogramming strategies.

5. Conclusion

During the past few years, many progresses have been made in regenerating β cells, of which the ultimate goal is to find a cure for the treatment of insulin-deficient diabetes (i.e., T1D). The β cell regeneration strategies can be classified into two main categories: in vitro β cell regeneration using pluripotent stem cells and in vivo reprogramming of non-β cells into β cells. The better understanding of the underlying mechanisms for embryonic β cell development and adult β cell regeneration has clearly benefited the exploration of strategies to regenerate β cells in vitro and in vivo.

In vitro regeneration of β cells are focused on human pluripotent stem cells. This involves the proliferation of the stem cells in vitro, and differentiating them into functional β cells (or endocrine progenitor cells so that they can continue to differentiate in vivo after transplantation). Significant progresses have been made to date, which set the foundation for the stem cell-based β cell replacement therapy to be moved into clinical trials. Another β cell regeneration strategy under investigation is to reprogram non-β cells into β cells in vivo. Different cell types have been explored as the potential targets, and progresses have been made with liver cells, gut cells, pancreatic exocrine cells, and islet α cells. However, it should be noted that, because of the in vivo nature of this strategy, the therapeutic efficacy and safety are of major concern. More studies with different models are needed before the strategies can be translated into clinical studies.

6. Expert opinion

Regenerating β cells has shown its potential as a cure for the treatment of insulin-deficient diabetes. The most promising strategy is based on pluripotent stem cells, in which both human ESCs and iPSCs can be proliferated and differentiated into functional β cells in vitro. One of the most critical advancements is the development of an efficient and scalable differentiation protocol for in vitro β cell regeneration from cultured human ESCs and iPSCs**87, *96. This strategy essentially circumvents the major limitation in islet transplantation—islet availability. On the other hand, a major safety concern in stem cell-based therapy is the potential of tumorigenesis, which is largely due to the high proliferative nature of the undifferentiated stem cells. Therefore, a means to efficiently remove the undifferentiated cells needs to be developed. Implementation of islet encapsulation is also necessary because it allows easy removal of any tumors formed by the implanted cells, therefore mitigating the safety concern.

Another major issue concerning in vitro β cell regeneration is host immune response—immune rejection of the transplanted stem cell-derived β (SC-β) cells and autoimmunity against β cells that caused the original β cell loss in the T1D recipients. In current clinical islet transplantation settings, immunosuppression regimes are incorporated to minimize immune rejection. Similar settings are required for the transplantation of SC-β cells in most cases. Immune rejection can be minimized if the SC-β cells are generated from the patients’ own iPSCs, which is a major advantage with individualized β cell replacement therapy. The islet encapsulation devices, if implemented properly, should also reduce immune rejection. How to circumvent the autoimmunity against β cells, however, is a big challenge. Many studies have attempted to induce immune tolerance, and progresses reported in animal studies67, 115. A combination of β cell regeneration and immune tolerance induction is apparently essential to achieve long-term therapeutic benefits for T1D treatment.

Of note, compared to human ESCs and iPSCs, pancreatic stem cells are more closely related to β cells and are thus easier to be differentiated into β cells. In fact, spontaneous differentiation into β cells occurs when pancreatic stem cells are transplanted into mice in vivo. Currently most pancreatic stem cells are isolated directly from human pancreatic donors (leftovers after islet isolation). Therefore there is also a donor limitation issue. In addition, isolation and culturing of pancreatic stem cells are more complicated than the culturing of human ESC and iPSC lines. Therefore, a more sophisticated protocol is needed before β cell regeneration from pancreatic stem cells can be moved from pre-clinical to clinical studies.

The in vivo reprogramming of non-β cells into β cells is an attractive but challenging strategy. Thus far, four types of tissues/cells have been explored in preclinical studies, which include liver cells, GI tract cells, pancreatic exocrine cells, and islet α cells. More remotely related cells require more complicated manipulation of gene expression. For example, liver-to-pancreas transdifferentiation appears to be a progressive and hierarchical process, which needs sequential expression of transcription factors in the order of Pdx1, Pax4, and MafA. The epithelium of antral stomach can be reprogrammed into insulin+ cells by co-expression of Ngn3, Pdx1, and MafA. The acinar cells in pancreas can be reprogrammed into 3 types of islet cells with different transcription factors, and a combination of Ngn3, Pdx1 and MafA results in acinar-to-β cell conversion. Transdifferentiating α cells to β cells can be achieved by forced expression of a single transcription factor Pax4 or by inhibition of Arx.

The major limitation of the in vivo reprogramming strategies is how to deliver the reprogramming factors into the target tissues/cells efficiently and specifically. The problem is even more challenging when multiple or sequential gene delivery of transcription factors is needed, as in the cases of liver, stomach and acinar cells. In addition, although in vivo reprogramming does not have the issue of immune rejection of the transplanted SC-β cells, there is another immune response-related problem: currently viral vectors are needed to deliver the transcription factors in vivo, and these vectors often cause major inflammatory responses, which is a safety concern in clinic. In fact, these gene delivery-related issues have been the long-standing obstacles limiting the success of gene therapy strategies in clinic in general116. On the other hand, employment of small molecules (such as artemininin) and cytokines (EGF and CNTF) minimizes such problems, and thus provides an important avenue towards clinical realization of reprogramming strategies.

Finally, with regard to converting α cells into β cells, it should be noted that α cells are not as abundant as acinar, liver or gut cells; in addition, it is more difficult to achieve efficient and specific gene delivery into islet α cells compared to the other cells. Nonetheless, there are some unique advantages with α cell reprogramming. Islet α and β cells are closely related, so α-to-β conversion only requires one transcription factor Pax4. More interestingly, there is an emerging theory regarding β cell failure in T2D, which is β-to-α cell dedifferentiation117, 118. In other words, it appears that in T2D, β cells are not dead; instead, they have simply lost their key transcription factors and gradually become glucagon-producing α cells119. Similarly, β-to-α phenotypic change has been observed in the re-aggregated human islet cells in vitro and in the pancreas of recently diagnosed T2D patients120, 121. The β-to-α dedifferentiation implicates that restoring β cell identity would be a key to the treatment of β cell dysfunction in T2D. A means to induce α-to-β cell conversion would reverse β-to-α dedifferentiation, and thus provides therpeutic benefits for T2D patients with insulin deficiency. Therefore, reprogramming α cells into β cells have its own advantage and clinical relevance as it may be beneficial for both T1D and T2D patients.

Taken together, regenerating β cells has become a potential cure for the treatment of insulin deficient diabetes. Many progresses have been made, and it is getting close to clinical reality. Nevertheless, more hurdles need to be overcome before any of the β cell regeneration strategies can be fully translated from bench to bedside.

Article highlights:

An ultimate cure for type 1 diabetes requires the replacement of the lost β cells, and many progresses have been made in search of strategies to regenerate β cells to date.

Current β cell regeneration strategies can be classified into two categories: in vitro β cell regeneration using pluripotent stem cells, and in vivo reprogramming of non-β cells into β cells.

In vitro regeneration of β cells has been explored with human pancreatic stem cells, human embryonic stem cells, and human induced pluripotent cells. An efficient and scalable in vitro β cell differentiation protocol has been developed.

The development of efficient β cell differentiation protocol and implementation of islet encapsulation devices have helped to move stem cell-based β cell regeneration strategy from preclinical to clinical studies.

In vivo regeneration of β cells are focused on reprogramming of non-β cells into β cells. Four types of tissues/cells have been explored in preclinical studies, which include liver cells, gut cells, pancreatic exocrine cells, and islet α cells.

β cell regeneration strategies have shown their potential for the treatment of insulin deficient diabetes, but more hurdles need to be overcome before they can be fully translated from bench to bedside.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This project was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grants DK081463 and DK107412.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose

References:

- 1.CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report. cdcgov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-reportpdf 2017.

- 2.Ryan EA, Lakey JR, Paty BW, et al. Successful islet transplantation: continued insulin reserve provides long-term glycemic control. Diabetes 2002. July;51(7):2148–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *3.Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, et al. International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. The New England journal of medicine 2006. September 28;355(13):1318–30. A milestone clinical study showing the success of islet transplantation for the treatment of T1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Hering B. Edmonton’s islet success has indeed been replicated elsewhere. Lancet 2003. October 11;362(9391):1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Adra DP, Gill RS, Imes S, et al. Single-donor islet transplantation and long-term insulin independence in select patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Transplantation 2014. November 15;98(9):1007–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bretzel RG, Brandhorst D, Brandhorst H, et al. Improved survival of intraportal pancreatic islet cell allografts in patients with type-1 diabetes mellitus by refined peritransplant management. J Mol Med 1999. January;77(1):140–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorenzo PI, Juarez-Vicente F, Cobo-Vuilleumier N, et al. The Diabetes-Linked Transcription Factor PAX4: From Gene to Functional Consequences. Genes 2017. March 09;8(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaneto H, Miyatsuka T, Kawamori D, et al. PDX-1 and MafA play a crucial role in pancreatic beta-cell differentiation and maintenance of mature beta-cell function. Endocr J 2008. May;55(2):235–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afelik S, Rovira M. Pancreatic beta-cell regeneration: Facultative or dedicated progenitors? Mol Cell Endocrinol 2017. April 15;445:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernardo AS, Hay CW, Docherty K. Pancreatic transcription factors and their role in the birth, life and survival of the pancreatic beta cell. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2008. November 6;294(1–2):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rukstalis JM, Habener JF. Neurogenin3: a master regulator of pancreatic islet differentiation and regeneration. Islets 2009. Nov-Dec;1(3):177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **12.Oliver-Krasinski JM, Stoffers DA. On the origin of the beta cell. Genes Dev 2008. August 1;22(15):1998–2021. A comprehensive review on transcription factors involved in pancreatic organogenesis and beta cell development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonsson J, Carlsson L, Edlund T, et al. Insulin-promoter-factor 1 is required for pancreas development in mice. Nature 1994. October 13;371(6498):606–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Offield MF, Jetton TL, Labosky PA, et al. PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development 1996. March;122(3):983–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahlgren U, Jonsson J, Edlund H. The morphogenesis of the pancreatic mesenchyme is uncoupled from that of the pancreatic epithelium in IPF1/PDX1-deficient mice. Development 1996. May;122(5):1409–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoffers DA, Zinkin NT, Stanojevic V, et al. Pancreatic agenesis attributable to a single nucleotide deletion in the human IPF1 gene coding sequence. Nature genetics 1997. January;15(1):106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Q, Law AC, Rajagopal J, et al. A multipotent progenitor domain guides pancreatic organogenesis. Dev Cell 2007. July;13(1):103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahlgren U, Jonsson J, Jonsson L, et al. beta-cell-specific inactivation of the mouse Ipf1/Pdx1 gene results in loss of the beta-cell phenotype and maturity onset diabetes. Genes Dev 1998. June 15;12(12):1763–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brissova M, Shiota M, Nicholson WE, et al. Reduction in pancreatic transcription factor PDX-1 impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem 2002. March 29;277(13):11225–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holland AM, Hale MA, Kagami H, et al. Experimental control of pancreatic development and maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002. September 17;99(19):12236–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H, Maechler P, Ritz-Laser B, et al. Pdx1 level defines pancreatic gene expression pattern and cell lineage differentiation. J Biol Chem 2001. July 06;276(27):25279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CS, Perreault N, Brestelli JE, et al. Neurogenin 3 is essential for the proper specification of gastric enteroendocrine cells and the maintenance of gastric epithelial cell identity. Genes Dev 2002. June 15;16(12):1488–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenny M, Uhl C, Roche C, et al. Neurogenin3 is differentially required for endocrine cell fate specification in the intestinal and gastric epithelium. Embo J 2002. December 02;21(23):6338–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gradwohl G, Dierich A, LeMeur M, et al. neurogenin3 is required for the development of the four endocrine cell lineages of the pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000. February 15;97(4):1607–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johansson KA, Dursun U, Jordan N, et al. Temporal control of neurogenin3 activity in pancreas progenitors reveals competence windows for the generation of different endocrine cell types. Dev Cell 2007. March;12(3):457–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villasenor A, Chong DC, Cleaver O. Biphasic Ngn3 expression in the developing pancreas. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 2008. November;237(11):3270–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.St-Onge L, Sosa-Pineda B, Chowdhury K, et al. Pax6 is required for differentiation of glucagon-producing alpha-cells in mouse pancreas. Nature 1997. May 22;387(6631):406–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naya FJ, Huang HP, Qiu Y, et al. Diabetes, defective pancreatic morphogenesis, and abnormal enteroendocrine differentiation in BETA2/neuroD-deficient mice. Genes Dev 1997. September 15;11(18):2323–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sussel L, Kalamaras J, Hartigan-O’Connor DJ, et al. Mice lacking the homeodomain transcription factor Nkx2.2 have diabetes due to arrested differentiation of pancreatic beta cells. Development 1998. June;125(12):2213–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collombat P, Mansouri A, Hecksher-Sorensen J, et al. Opposing actions of Arx and Pax4 in endocrine pancreas development. Genes Dev 2003. October 15;17(20):2591–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collombat P, Hecksher-Sorensen J, Broccoli V, et al. The simultaneous loss of Arx and Pax4 genes promotes a somatostatin-producing cell fate specification at the expense of the alpha- and beta-cell lineages in the mouse endocrine pancreas. Development 2005. July;132(13):2969–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishimura W, Kondo T, Salameh T, et al. A switch from MafB to MafA expression accompanies differentiation to pancreatic beta-cells. Dev Biol 2006. May 15;293(2):526–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papizan JB, Singer RA, Tschen SI, et al. Nkx2.2 repressor complex regulates islet beta-cell specification and prevents beta-to-alpha-cell reprogramming. Genes Dev 2011. November 01;25(21):2291–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sander M, Sussel L, Conners J, et al. Homeobox gene Nkx6.1 lies downstream of Nkx2.2 in the major pathway of beta-cell formation in the pancreas. Development 2000. December;127(24):5533–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swisa A, Avrahami D, Eden N, et al. PAX6 maintains beta cell identity by repressing genes of alternative islet cell types. J Clin Invest 2017. January 03;127(1):230–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *36.Xu X, D’Hoker J, Stange G, et al. Beta cells can be generated from endogenous progenitors in injured adult mouse pancreas. Cell 2008. January 25;132(2):197–207. An essential study demonstrating the presence of islet progenitors in adult mouse pancreas and their role in beta cell regeneration following injury. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu H, Guz Y, Kedees MH, et al. Precursor cells in mouse islets generate new beta-cells in vivo during aging and after islet injury. Endocrinology 2010. February;151(2):520–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonner-Weir S, Toschi E, Inada A, et al. The pancreatic ductal epithelium serves as a potential pool of progenitor cells. Pediatric diabetes 2004;5 Suppl 2:16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li WC, Rukstalis JM, Nishimura W, et al. Activation of pancreatic-duct-derived progenitor cells during pancreas regeneration in adult rats. Journal of cell science 2010. August 15;123(Pt 16):2792–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *40.Dor Y, Brown J, Martinez OI, et al. Adult pancreatic beta-cells are formed by self-duplication rather than stem-cell differentiation. Nature 2004. May 6;429(6987):41–6. First study demonstrating new beta cells are generated by replication of existing beta cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teta M, Rankin MM, Long SY, et al. Growth and regeneration of adult beta cells does not involve specialized progenitors. Dev Cell 2007. May;12(5):817–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meier JJ, Lin JC, Butler AE, et al. Direct evidence of attempted beta cell regeneration in an 89-year-old patient with recent-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2006. August;49(8):1838–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *43.Thorel F, Nepote V, Avril I, et al. Conversion of adult pancreatic alpha-cells to beta-cells after extreme beta-cell loss. Nature 2010. April 22;464(7292):1149–54. First study describing alpha-to-beta cell transdifferentiation as a mechanism of beta cell regeneration. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung CH, Hao E, Piran R, et al. Pancreatic beta-cell neogenesis by direct conversion from mature alpha-cells. Stem Cells 2010. September;28(9):1630–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chera S, Baronnier D, Ghila L, et al. Diabetes recovery by age-dependent conversion of pancreatic delta-cells into insulin producers. Nature 2014. October 23;514(7523):503–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonner-Weir S, Li WC, Ouziel-Yahalom L, et al. Beta-cell growth and regeneration: replication is only part of the story. Diabetes 2010. October;59(10):2340–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bone RN, Icyuz M, Zhang Y, et al. Gene transfer of active Akt1 by an infectivity-enhanced adenovirus impacts beta-cell survival and proliferation differentially in vitro and in vivo. Islets 2012. Nov-Dec;4(6):366–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brennand K, Huangfu D, Melton D. All beta cells contribute equally to islet growth and maintenance. PLoS biology 2007. July;5(7):e163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rankin MM, Kushner JA. Adaptive beta-cell proliferation is severely restricted with advanced age. Diabetes 2009. June;58(6):1365–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen X, Zhang X, Chen F, et al. Comparative study of regenerative potential of beta cells from young and aged donor mice using a novel islet transplantation model. Transplantation 2009. August 27;88(4):496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang RN, Kloppel G, Bouwens L. Duct- to islet-cell differentiation and islet growth in the pancreas of duct-ligated adult rats. Diabetologia 1995. December;38(12):1405–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meier JJ, Butler AE, Galasso R, et al. Increased islet beta cell replication adjacent to intrapancreatic gastrinomas in humans. Diabetologia 2006. November;49(11):2689–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phillips JM, O’Reilly L, Bland C, et al. Patients with chronic pancreatitis have islet progenitor cells in their ducts, but reversal of overt diabetes in NOD mice by anti-CD3 shows no evidence for islet regeneration. Diabetes 2007. March;56(3):634–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.El-Gohary Y, Wiersch J, Tulachan S, et al. Intraislet Pancreatic Ducts Can Give Rise to Insulin-Positive Cells. Endocrinology 2016. January;157(1):166–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamaguchi J, Liss AS, Sontheimer A, et al. Pancreatic duct glands (PDGs) are a progenitor compartment responsible for pancreatic ductal epithelial repair. Stem cell research 2015. July;15(1):190–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carpino G, Renzi A, Cardinale V, et al. Progenitor cell niches in the human pancreatic duct system and associated pancreatic duct glands: an anatomical and immunophenotyping study. Journal of anatomy 2016. March;228(3):474–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beattie GM, Itkin-Ansari P, Cirulli V, et al. Sustained proliferation of PDX-1+ cells derived from human islets. Diabetes 1999. May;48(5):1013–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gao R, Ustinov J, Korsgren O, et al. In vitro neogenesis of human islets reflects the plasticity of differentiated human pancreatic cells. Diabetologia 2005. November;48(11):2296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lechner A, Nolan AL, Blacken RA, et al. Redifferentiation of insulin-secreting cells after in vitro expansion of adult human pancreatic islet tissue. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2005. February 11;327(2):581–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seaberg RM, Smukler SR, Kieffer TJ, et al. Clonal identification of multipotent precursors from adult mouse pancreas that generate neural and pancreatic lineages. Nat Biotechnol 2004. September;22(9):1115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guz Y, Nasir I, Teitelman G. Regeneration of pancreatic beta cells from intra-islet precursor cells in an experimental model of diabetes. Endocrinology 2001. November;142(11):4956–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fernandes A, King LC, Guz Y, et al. Differentiation of new insulin-producing cells is induced by injury in adult pancreatic islets. Endocrinology 1997. April;138(4):1750–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gershengorn MC, Hardikar AA, Wei C, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition generates proliferative human islet precursor cells. Science 2004. December 24;306(5705):2261–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van der Meulen T, Mawla AM, DiGruccio MR, et al. Virgin Beta Cells Persist throughout Life at a Neogenic Niche within Pancreatic Islets. Cell metabolism 2017. April 04;25(4):911–26 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kopinke D, Murtaugh LC. Exocrine-to-endocrine differentiation is detectable only prior to birth in the uninjured mouse pancreas. BMC developmental biology 2010. April 08;10:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fryer BH, Rezania A, Zimmerman MC. Generating beta-cells in vitro: progress towards a Holy Grail. Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity 2013. April;20(2):112–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lilly MA, Davis MF, Fabie JE, et al. Current stem cell based therapies in diabetes. American journal of stem cells 2016;5(3):87–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Godfrey KJ, Mathew B, Bulman JC, et al. Stem cell-based treatments for Type 1 diabetes mellitus: bone marrow, embryonic, hepatic, pancreatic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association 2012. January;29(1):14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Otonkoski T, Gao R, Lundin K. Stem cells in the treatment of diabetes. Annals of medicine 2005;37(7):513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Russ HA, Sintov E, Anker-Kitai L, et al. Insulin-producing cells generated from dedifferentiated human pancreatic beta cells expanded in vitro. PLoS One 2011;6(9):e25566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Corritore E, Lee YS, Sokal EM, et al. beta-cell replacement sources for type 1 diabetes: a focus on pancreatic ductal cells. Therapeutic advances in endocrinology and metabolism 2016. August;7(4):182–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ramiya VK, Maraist M, Arfors KE, et al. Reversal of insulin-dependent diabetes using islets generated in vitro from pancreatic stem cells. Nature medicine 2000. March;6(3):278–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *73.Bonner-Weir S, Taneja M, Weir GC, et al. In vitro cultivation of human islets from expanded ductal tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000. July 05;97(14):7999–8004. Article on the generation of islet-like clusters in vtiro from human ductal tissue using matrigel-based 3D culturing system. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hao E, Tyrberg B, Itkin-Ansari P, et al. Beta-cell differentiation from nonendocrine epithelial cells of the adult human pancreas. Nature medicine 2006. March;12(3):310–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gmyr V, Belaich S, Muharram G, et al. Rapid purification of human ductal cells from human pancreatic fractions with surface antibody CA19–9. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2004. July 16;320(1):27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee J, Sugiyama T, Liu Y, et al. Expansion and conversion of human pancreatic ductal cells into insulin-secreting endocrine cells. eLife 2013. November 19;2:e00940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yatoh S, Dodge R, Akashi T, et al. Differentiation of affinity-purified human pancreatic duct cells to beta-cells. Diabetes 2007. July;56(7):1802–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rescan C, Le Bras S, Lefebvre VH, et al. EGF-induced proliferation of adult human pancreatic duct cells is mediated by the MEK/ERK cascade. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology 2005. January;85(1):65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoesli CA, Johnson JD, Piret JM. Purified human pancreatic duct cell culture conditions defined by serum-free high-content growth factor screening. PLoS One 2012;7(3):e33999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roche E, Jones J, Arribas MI, et al. Role of small bioorganic molecules in stem cell differentiation to insulin-producing cells. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry 2006. October 01;14(19):6466–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Corritore E, Dugnani E, Pasquale V, et al. beta-Cell differentiation of human pancreatic duct-derived cells after in vitro expansion. Cellular reprogramming 2014. December;16(6):456–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dominguez-Bendala J, Lanzoni G, Klein D, et al. The Human Endocrine Pancreas: New Insights on Replacement and Regeneration. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM 2016. March;27(3):153–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.D’Amour KA, Bang AG, Eliazer S, et al. Production of pancreatic hormone-expressing endocrine cells from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 2006. November;24(11):1392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hrvatin S, O’Donnell CW, Deng F, et al. Differentiated human stem cells resemble fetal, not adult, beta cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014. February 25;111(8):3038–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kroon E, Martinson LA, Kadoya K, et al. Pancreatic endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells in vivo. Nat Biotechnol 2008. April;26(4):443–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rezania A, Bruin JE, Riedel MJ, et al. Maturation of human embryonic stem cell-derived pancreatic progenitors into functional islets capable of treating pre-existing diabetes in mice. Diabetes 2012. August;61(8):2016–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **87.Pagliuca FW, Millman JR, Gurtler M, et al. Generation of functional human pancreatic beta cells in vitro. Cell 2014. October 9;159(2):428–39. Article on the development of an in vitro differentiation protocol that induces human stem cells into functional β cells in a reproducible and scalable fashion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rezania A, Bruin JE, Arora P, et al. Reversal of diabetes with insulin-producing cells derived in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 2014. November;32(11):1121–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Basford CL, Prentice KJ, Hardy AB, et al. The functional and molecular characterisation of human embryonic stem cell-derived insulin-positive cells compared with adult pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 2012. February;55(2):358–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bruin JE, Rezania A, Xu J, et al. Maturation and function of human embryonic stem cell-derived pancreatic progenitors in macroencapsulation devices following transplant into mice. Diabetologia 2013. September;56(9):1987–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kirk K, Hao E, Lahmy R, et al. Human embryonic stem cell derived islet progenitors mature inside an encapsulation device without evidence of increased biomass or cell escape. Stem cell research 2014. May;12(3):807–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *92.Vegas AJ, Veiseh O, Gurtler M, et al. Long-term glycemic control using polymer-encapsulated human stem cell-derived beta cells in immune-competent mice. Nature medicine 2016. March;22(3):306–11. Impressive results from the transplantation of encapsulated beta cells that are generated from stem cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Motte E, Szepessy E, Suenens K, et al. Composition and function of macroencapsulated human embryonic stem cell-derived implants: comparison with clinical human islet cell grafts. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism 2014. November 01;307(9):E838–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006. August 25;126(4):663–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cho HJ, Lee CS, Kwon YW, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult somatic cells by protein-based reprogramming without genetic manipulation. Blood 2010. July 22;116(3):386–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *96.Millman JR, Xie C, Van Dervort A, et al. Generation of stem cell-derived beta-cells from patients with type 1 diabetes. Nature communications 2016. May 10;7:11463 Successful beta cell regeneration from iPSCs derived from Type 1 Diabetic patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Meivar-Levy I, Ferber S. Reprogramming of liver cells into insulin-producing cells. Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism 2015. December;29(6):873–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *98.Ferber S, Halkin A, Cohen H, et al. Pancreatic and duodenal homeobox gene 1 induces expression of insulin genes in liver and ameliorates streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemia. Nature medicine 2000. May;6(5):568–72. First study showing liver cells can be reprogrammed into beta cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gefen-Halevi S, Rachmut IH, Molakandov K, et al. NKX6.1 promotes PDX-1-induced liver to pancreatic beta-cells reprogramming. Cellular reprogramming 2010. December;12(6):655–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Berneman-Zeitouni D, Molakandov K, Elgart M, et al. The temporal and hierarchical control of transcription factors-induced liver to pancreas transdifferentiation. PLoS One 2014;9(2):e87812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Talchai C, Xuan S, Kitamura T, et al. Generation of functional insulin-producing cells in the gut by Foxo1 ablation. Nature genetics 2012. April;44(4):406–12, S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *102.Chen YJ, Finkbeiner SR, Weinblatt D, et al. De novo formation of insulin-producing “neo-beta cell islets” from intestinal crypts. Cell reports 2014. March 27;6(6):1046–58. First study showing intestinal crypt cells can be reprogrammed into islet-like cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ariyachet C, Tovaglieri A, Xiang G, et al. Reprogrammed Stomach Tissue as a Renewable Source of Functional beta Cells for Blood Glucose Regulation. Cell stem cell 2016. March 03;18(3):410–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **104.Zhou Q, Brown J, Kanarek A, et al. In vivo reprogramming of adult pancreatic exocrine cells to beta-cells. Nature 2008. October 2;455(7213):627–32. A key study identifying the transcription factors that can reprogram exocrine cells into beta cells in vivo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li W, Nakanishi M, Zumsteg A, et al. In vivo reprogramming of pancreatic acinar cells to three islet endocrine subtypes. eLife 2014. January 01;3:e01846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *106.Baeyens L, Lemper M, Leuckx G, et al. Transient cytokine treatment induces acinar cell reprogramming and regenerates functional beta cell mass in diabetic mice. Nat Biotechnol 2014. January;32(1):76–83. Article on reprogramming acinar cells into beta cells with cytokines. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 107.Sosa-Pineda B, Chowdhury K, Torres M, et al. The Pax4 gene is essential for differentiation of insulin-producing beta cells in the mammalian pancreas. Nature 1997. March 27;386(6623):399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Collombat P, Xu X, Ravassard P, et al. The ectopic expression of Pax4 in the mouse pancreas converts progenitor cells into alpha and subsequently beta cells. Cell 2009. August 7;138(3):449–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Al-Hasani K, Pfeifer A, Courtney M, et al. Adult duct-lining cells can reprogram into beta-like cells able to counter repeated cycles of toxin-induced diabetes. Dev Cell 2013. July 15;26(1):86–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kooptiwut S, Plengvidhya N, Chukijrungroat T, et al. Defective PAX4 R192H transcriptional repressor activities associated with maturity onset diabetes of the young and early onset-age of type 2 diabetes. Journal of diabetes and its complications 2012. Jul-Aug;26(4):343–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Plengvidhya N, Kooptiwut S, Songtawee N, et al. PAX4 mutations in Thais with maturity onset diabetes of the young. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007. July;92(7):2821–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sujjitjoon J, Kooptiwut S, Chongjaroen N, et al. Aberrant mRNA splicing of paired box 4 (PAX4) IVS7–1G>A mutation causing maturity-onset diabetes of the young, type 9. Acta diabetologica 2015. May 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *113.Zhang Y, Fava GE, Wang H, et al. PAX4 Gene Transfer Induces alpha-to-beta Cell Phenotypic Conversion and Confers Therapeutic Benefits for Diabetes Treatment. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 2016. February;24(2):251–60. Article on reprogramming alpha cells into beta cells with Pax4-based gene therapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *114.Li J, Casteels T, Frogne T, et al. Artemisinins Target GABAA Receptor Signaling and Impair alpha Cell Identity. Cell 2017. January 12;168(1–2):86–100 e15. Article on reprogramming alpha cells into beta cells by artemisinin-induced Arx inhibition. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Szot GL, Yadav M, Lang J, et al. Tolerance induction and reversal of diabetes in mice transplanted with human embryonic stem cell-derived pancreatic endoderm. Cell stem cell 2015. February 05;16(2):148–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nayak S, Herzog RW. Progress and prospects: immune responses to viral vectors. Gene Ther 2010. March;17(3):295–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Talchai C, Xuan S, Lin HV, et al. Pancreatic beta cell dedifferentiation as a mechanism of diabetic beta cell failure. Cell 2012. September 14;150(6):1223–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang Z, York NW, Nichols CG, et al. Pancreatic beta cell dedifferentiation in diabetes and redifferentiation following insulin therapy. Cell metabolism 2014. May 6;19(5):872–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Guo S, Dai C, Guo M, et al. Inactivation of specific beta cell transcription factors in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest 2013. August 1;123(8):3305–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.White MG, Marshall HL, Rigby R, et al. Expression of mesenchymal and alpha-cell phenotypic markers in islet beta-cells in recently diagnosed diabetes. Diabetes care 2013. November;36(11):3818–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Spijker HS, Ravelli RB, Mommaas-Kienhuis AM, et al. Conversion of mature human beta-cells into glucagon-producing alpha-cells. Diabetes 2013. July;62(7):2471–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]