Abstract

Cyclic peptides are an exciting class of molecules with a variety of applications. However, design strategies for cyclic peptide therapeutics, for example, are generally limited by a poor understanding of their sequence–structure relationships. This knowledge gap often leads to a trial-and-error approach for designing cyclic peptides for a specific purpose, which is both costly and time-consuming. Herein, we describe the current experimental and computational efforts in understanding and designing head-to-tail cyclic peptides along with their respective challenges. In addition, we provide several future directions in the field of computational cyclic peptide design to improve its accuracy, efficiency and applicability. These advances, combined with experimental techniques, shall ultimately provide a better understanding of these interesting molecules and a reliable working platform to rationally design cyclic peptides with desired characteristics.

Introduction

Cyclic peptides (CPs) are a unique class of molecules with interesting properties. Notably, CPs have been developed for various nanotechnologies, including alternatives to carbon nanotubes,1 transmembrane transport channels2 and artificial photosynthetic systems.3 Additionally, CPs have emerged as important players in drug development.4–6 CPs have been shown to modulate protein–protein interactions with high affinity and specificity7–10 and act as potent antimicrobial peptides by disrupting cell membranes.11–15 On one hand, design principles of CPs for applications such as self-assembling nanotubes are reasonably well formulated.16 For example, the internal diameter of CP nanotubes can be modulated by the number of residues used and typically contain alternating D- and L-amino acids.1,17,18 The properties of the nanotubes can be tuned through incorporation of canonical as well as non-canonical amino acids to achieve a variety of functionalities.16 On the other hand, many of the current CP protein–protein interaction modulators and antimicrobial peptides are natural products or their derivatives.4,19 Their rational design remains rare, owing to our inability to predict CP structures de novo and our poor understanding of CP sequence–structure relationships. Consequently, the full potential of CPs is currently severely underexplored.

When designing novel CPs, numerous components must be considered. For example, various cyclization strategies are available, including head-to-tail,20 side-chain to side-chain21,22 and side-chain to terminus bonding.23,24 Recently, ring expansion has been shown as a promising alternative to head-to-tail cyclization, mitigating the entropic barriers of cyclization using the more traditional method.25–30 Multiple cyclizations can also be incorporated to generate bicyclic peptides, tricyclic peptides, etc., where these additional cyclizations can provide further restraints to rigidify the peptides and afford an even greater complexity of design space.31–34 In this review we will focus on head-to-tail cyclized peptides. In addition to the canonical amino acids, N-methylated amino acids, D-amino acids, β-amino acids and other non-natural amino acids can be implemented to optimize CP properties. With many variables to consider and compounded by synthetic challenges, experimentally generating, testing and analyzing large CP libraries can be arduous and time consuming. Furthermore, CPs typically form structural ensembles in solution rather than adopting one single dominant conformation.35–46 This feature makes their experimental structural characterization particularly difficult and understanding how their sequences govern their conformations using a purely experimental approach almost impossible.

While using merely brute force synthesis and experimental structural characterization to understand and design CPs is challenging and likely intractable, the use of computational methods offers a promising and complementary alternative. In this review, we will provide an overview of previous experimental approaches to understand and design CPs as well as the challenges associated with them. We will also discuss recent advances in the computational design of CPs as well as provide commentary on areas of the field where further development is needed to ensure accurate and efficient structure predictions of CPs.

Experimental design of cyclic peptides

Experimental approaches for CP design often utilize non-canonical amino acids alongside a variety of cyclization strategies. Herein we focus on the use of various canonical and non-canonical amino acids with head-to-tail cyclization. With a number of systematic studies, several general rules and interesting observations have been made for CPs. For example, cyclic tripeptides are generally highly strained and contain at least one cis peptide bond, with the most energetically favorable conformation consisting of three cis peptide bonds.47 Cyclic tetrapeptides are the smallest CPs that can adopt an all-trans conformation,48 although they generally adopt either an all-cis49 or alternating cis/trans conformation.50–55

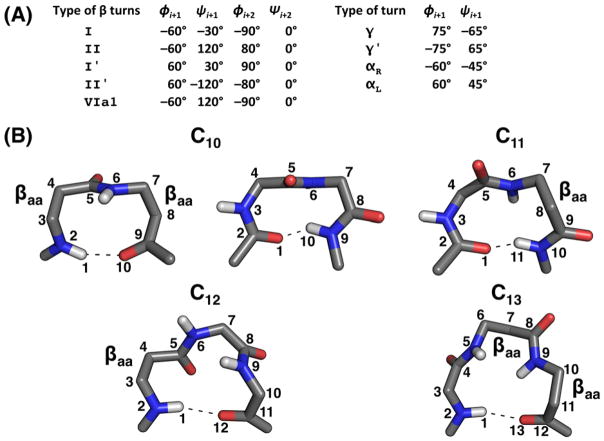

Cyclic pentapeptides commonly form structures consisting of a β-turn and a tighter turn (such as a γ/γ′- or an αR/αL-turn; ideal dihedral angles for these turns are shown in Figure 1A) opposite the β-turn. In these CPs, there is at least one hydrogen bond in the β-turn region, while a second hydrogen bond is only formed if the tight turn is a γ or γ′-turn.24,56–62 In order to understand how a D-amino acid affected the conformational preference of cyclic pentapeptides, CPs containing one D- and four L-amino acids were studied. These cyclic pentapeptides preferred a conformation with a type II′ β-turn + a γ/αR tight turn, where the D-amino acid was always at the i+1 position of the type II′ β-turn.58,61–63 To further explore sequence–structure relationships in cyclic pentapeptides, Gierasch et al. studied variants of cyclo-(GPX1GX2), where X1 was D-Phe or D-Ala and X2 was L-/D-Ala, L-Val or L-Phe.42 It was found that the residues PX1 adopted a type II β-turn and the identity of the tight turn was dependent on the amino acid composition and chirality of the rest of the sequence.42,64–66 For example, cyclo-(GPfGA), cyclo-(GPfGV), cyclo-(GPaGF), and cyclo-(GPfGa) all formed a type II β-turn at 2Px3, but formed a αL, αR, γ ′, and γ-turn at residue five, respectively.42

Figure 1.

(A) Ideal dihedral angles for five types of β-turns and four types of tight turns. Note that for type VIa1 β-turns the peptide bond between residues i+1 and i+2 must be cis. (B) Schematic representations of C10-, C11-, C12- and C13-like structures. C10-like structures comprised solely of β-amino acids (βaa, left) or α-amino acids (right) are shown. β-amino acids are labeled in all structures.

While cyclic pentapeptides commonly adopt a β-turn and a tight turn, cyclic hexapeptides generally form structures consisting of two β-turns at opposite ends with two intra-peptide hydrogen bonds. Much like the studies of cyclic pentapeptides, Gierasch et al. performed a systematic study of cyclo-(X1PX2X3PX4) cyclic hexapeptides, where X’s were various combinations of Gly, L/D-Ala, L/D-Phe or L/D-Val.67 From their experiments, three trends were established: (1) PG or Px (x indicates a D-amino acid) in a cyclic hexapeptide preferred a type II β-turn, where the Pro residue was at the i+1 position of the β-turn, (2) PX in a cyclic hexapeptide containing GPX, where X ≠ L-Val, formed a type I β-turn, where the Pro residue was at the i+1 position of the β-turn and (3) GP or xP in a cyclic hexapeptide containing GPV or xPX formed a type II′ β-turn, where the Pro residue was at the i+2 position of the β-turn.

Besides D-amino acids, β-amino acids can be incorporated into a CP to induce desired turn types.68–75 For example, by incorporating two β-Ala (Aβ) residues into cyclic tetrapeptides at different locations, Pavone et al. were able to control what types of turns those CPs would adopt.68,70,71 When the two Aβ residues were placed next to each other, the two consecutive Aβ residues tended to form a hydrogen bond in a C10-like structure, a 10-membered ring stabilized by a hydrogen bond (Figure 1B), allowing for the remaining two α-amino acids in the tetrapeptide to assume a β-turn type conformation. For example, the conformation of cyclo-(PFAβAβ) formed a type I β-turn at residues 1PF2 and a C10-like structure for the two Aβ residues opposite the β-turn.68 On the other hand, if the two Aβ residues were incorporated non-consecutively, then γ ′-turns were observed for the remaining two α-amino acids. For example, in both cyclo-(PAβPAβ) and cyclo-(PAβVAβ), two γ ′-turns were stabilized at the two α-amino acids.70,71 Therefore, the strategic placement of Aβ residues into a cyclic tetrapeptide can significantly impact the CP’s conformation.

Pavone et al. further performed similar types of studies for cyclic penta- and hexapeptides. For cyclic pentapeptides, they found that two consecutive Aβ residues could lead to different structural motifs.69,74,75 For example, cyclo-(PPFAβAβ) was found to adopt a type VIa1 β-turn at 1PP2, with a cis peptide bond between the two Pro residues (see Figure 1A for the ideal dihedral angles of a type VIa1 β-turn).69 In this conformation, the type VIa1 β-turn at 1PP2 adopted a C10-like structure, while 3FAβAβ5 adopted a C13-like structure (Figure 1B). On the other hand, cyclo-(PFFAβAβ) adopted an enlarged type II β-turn at 3FAβ4 and a cis peptide bond at 5AβP1.74 In this CP, residues 3FAβ4 formed a C11-like structure, while 5AβPF2 formed a C12-like structure (Figure 1B). For cyclic hexapeptides, it was found that Aβ residues have a low propensity to participate in forming a β-turn.72,73 For example, cyclo-(PFAβFFAβ) adopted two type I β-turns at residues 1PF2 and 4FF5, and cyclo-(PFAβPFAβ) adopted two type II β-turns at each PF, and the two Aβ amino acid served as the non-turning residues.72,73 These studies showed that β-amino acids could be used as a novel molecular tool for designing CPs with β-turns and γ-turns at specific locations.

Another example where non-canonical amino acids were incorporated into the CP design was the development of cyclo-(RGDfV) by Kessler et al (lower case letters in the peptide sequence indicate D-amino acids and underlined letters indicate N-methylated amino acids).76 First, systematic studies were performed on the parent CP, cyclo-(RGDFV), where the effects of single substitutions of L- to D-amino acids on the CP structure were investigated.57,77 It was found that the L- to D-amino substitution at 4F was the most beneficial and cyclo-(RGDfV) was selective towards its binding partner (integrin αVβ3) with a 1,000 times higher activity than a linear reference peptide GRGDSPK.76 Cyclo-(RGDfV) was then used as a template for various other modifications, including thioamide substitution,78 incorporation of turn mimetics,79 glycosylation,80 synthesis of retro-inverso analogues,81 and N-methylation76 in an attempt to further rigidify the peptide and improve its selectivity and activity for αVβ3. Of all these variants, N-methylation was found to be the most promising. In particular, cyclo-(RGDfV) demonstrated a four times higher activity for αVβ3 compared to the non-methylated cyclo-(RGDfV).76 These systematic studies showed how incorporation of one or multiple non-canonical amino acids can be utilized to optimize the selectivity and activity of CPs.

N-methylation has also been shown as a promising way of improving the oral bioavailability of CPs, an important pharmacokinetic property of therapeutics. In general, cyclization of small peptides tends to result in increased bioavailability,4,82,83 which can be further improved upon by incorporating N-methylated residue(s), as demonstrated in the cases of somatostatin and the melanocortin family.84,85 To shed more light on how N-methylation affects CP conformation and bioavailability, libraries of N-methylated CPs were synthesized and characterized.46,85–92 For example, Beck et al. characterized 54 N-methylated derivatives of cyclo-(aAAAAA) to understand how N-methylation affected the CP’s membrane permeability as well as its conformational preferences.46 In their study, eight N-methylated CPs showed higher membrane permeability as compared to the non-methylated parent sequence, while the other 46 CPs showed little or no improvement in membrane permeability. It is noted that while it is important for a compound to have high membrane permeability, it does not inherently mean that the compound will have high oral bioavailability, which is determined by numerous other factors including compound stability, gut transit time and first pass metabolism.93,94 Also, N-methyl groups need to be implemented with caution, as N-methylation at some sites can have a detrimental impact on the desired structure or function of the CP.86–89,95

Though experimental design strategies have been utilized with some success, there remain several formidable challenges. Arguably the most significant challenge in CP design is our poor understanding of their sequence–structure relationships. The current majority of experimental structural information for small CPs (≤8 amino acids) comes from X-ray crystal structures39,40,48–56,64,96–141 and NMR structures in organic solvent.13,36,37,42,58,61,63,66,67,77,111,113,118,126–132,134,139–171 However, X-ray crystal structures lack dynamic information, providing only a single snapshot among a possible ensemble of structures available in solution. Indeed, solution NMR studies of CPs show that they often adopt multiple poorly populated conformations, existing as structural ensembles rather than one dominant structure.35–46 Unfortunately, even the current state-of-the-art experimental methods lack the capability to fully characterize every individual conformation in a structural ensemble.172–175 Additionally, the structures adopted by CPs in organic solvent may not be the same structures those CPs adopt in water, the relevant solvent for biological studies and applications. Therefore, to experimentally establish valid sequence–structure relationships for CPs in aqueous solution, hundreds if not thousands of different sequences would first need to be synthesized to identify those rare instances where CPs adopt a single dominant conformation. Structures of these well-behaved CPs can then be obtained using multidimensional NMR spectroscopy to investigate how CP sequence controls structure. This trial-and-error approach of experimentally generating and rigorously characterizing thousands of CPs would be extremely costly and intractable. Therefore, in recent years computational simulations have emerged as being uniquely suited to aid in the development of sequence–structure relationships of CPs, as well as designing CPs to adopt desired conformations.

Computational design of cyclic peptides

Several computational methods have been used to design CPs, including virtual screening of CP libraries to identify CPs with high binding affinities for a given target,176–181 fragment-based algorithms to predict CP structures182–191 and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to characterize the conformational ensembles of CPs.192–201 While virtual screening has been shown to be an effective method of surveying sequence space and identifying residues crucial for binding, it currently lacks the capability to accurately describe CP–solvent interactions, which have been shown to play a crucial role in the structures CPs adopt.34,129,202–205 Additionally, virtual screening methods are typically based on libraries of linear peptide and protein systems, and therefore may not be suitable to describe the conformations of CPs.

Fragment-based approaches and loop closure algorithms have also been developed and used to predict CP structures. For example, kinematic closure (KIC), implemented in the Rosetta package, uses a multi-stage process for loop reconstruction.185 In the first stage, the backbone is optimized, with the side chains represented as centroids, and in the second stage the entire loop is optimized using an all-atom representation. This methodology was found to recapitulate the structures of many crystallographic loop conformations. However, similar to virtual screening, fragment-based approaches are also incapable of explicitly describing CP–solvent interactions. It is also noted that when fragment-based algorithms are developed to predict CP structures, they are often applicable to a limited set of CP sizes, cyclization strategies or residue types.182–184,186,187,189,191 Alternatively, explicit solvent MD simulations can describe CP–solvent interactions explicitly and have been used to predict the structural ensembles of various CPs.192–195,197–201 Herein, we will focus on how MD simulations have been used to understand and design CPs.

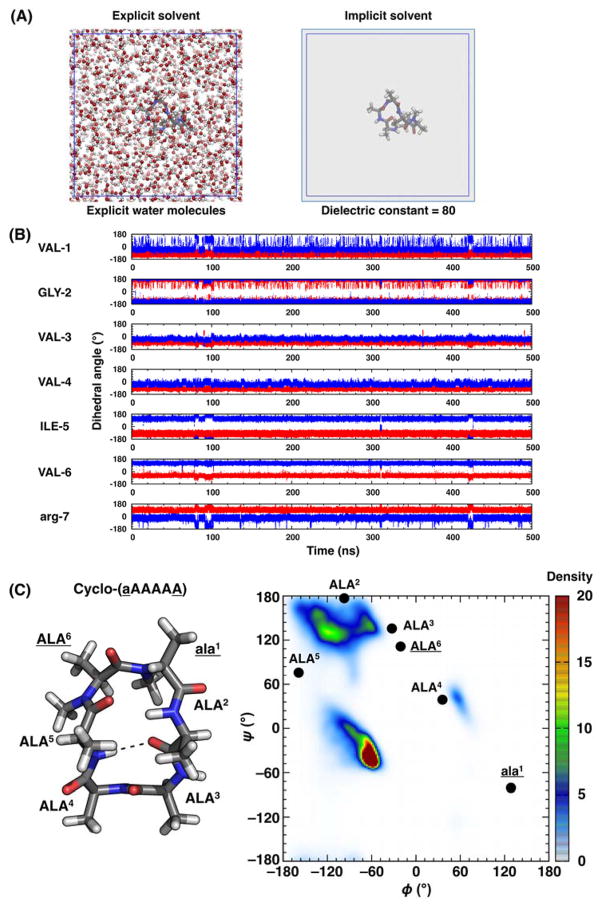

Several challenges are associated with using MD simulations to accurately and efficiently predict CP structures (Figure 2). (1) Both experimental and computational studies have shown that solvent plays a significant role in the structure a CP adopts.34,129,202–205 Therefore, to accurately account for direct CP–solvent interactions, explicit solvent simulations are necessary. However, explicit solvent simulations require substantial computational resources in order to evaluate the interactions and motions of a CP plus thousands of solvent molecules. (2) It remains challenging to efficiently explore the conformational space of a CP using conventional MD simulations. In small CPs (≤ 8 amino acids) large free energy barriers between conformations caused by ring strain usually prevents efficient sampling of relevant structures by standard MD,206 while large CPs (> 8 amino acids) can also present significant issues, because they often have vast conformational ensembles.47 (3) The ϕ/ψ dihedral angles of CPs, particularly of small ones, tend to fall outside the canonical regions in the Ramachandran space observed for linear peptides and proteins.207 Since most of the current peptide force fields are parameterized based on linear peptides and proteins, their accuracy at predicting CP structures must be verified.

Figure 2.

Challenges in CP design using MD simulations. (A) Explicit solvent simulations are necessary but computationally expensive. (B) Trajectories of φ (in red) and ψ (in blue) from a conventional MD simulation of cyclo-(VGVVIVr) show that the φ and ψ dihedrals do not frequently change within a 500 ns simulation (~2.2 days of simulation time on 16 CPU cores). (C) NMR structure of cyclo-(aAAAAA),46 where lowercase letters indicate D-amino acids and underlines indicate N-methylated residues, (left) and experimental φ/ψ angles overlaid on the typical Ramachandran plot for L-amino acids using the PDB database244 (right) show that many of φ/ψ angles fall outside the canonical α, β, or PPII regions.

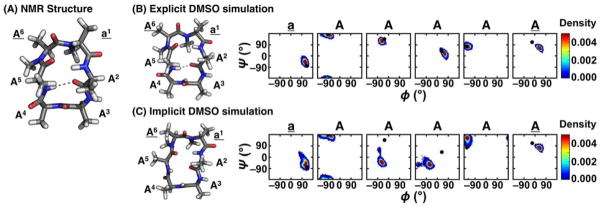

In a recent study, Quartararo et al. found that water was key to the structure of a bicyclic peptide.34 Using MD simulations, several water molecules with long-lived hydrogen bonds to the CP backbone atoms were identified. Subsequent NOESY and ROESY data showed cross peaks between the backbone atoms and water molecules, corroborating the observed MD results. This study provides an example of how water is important to the structure that constrained peptides adopt. Additionally, Beck et al. identified template structures through the synthesis and characterization of a library of N-methylated variants of the cyclic hexapeptide cyclo-(aAAAAA) as described previously. One of these template structures, cyclo-(aAAAAA) (underlines indicate N-methylated residues), contained all trans peptide bonds and two type II β-turns at residues 6Aa1 and 3AA4 in DMSO (Figure 3A). When simulated with explicit DMSO molecules, the simulation results accurately recapitulated the NMR structure (Figure 3B).201 However, this is not the case when simulated with implicit solvent using a dielectric constant equivalent to DMSO (ε = 47) (Figure 3C). The culmination of these results and similar shows that it is imperative to explicitly model solvent molecules in CP simulations.

Figure 3.

(A) NMR structure of cyclo-(aAAAAA), where lowercase letters indicate D-amino acids and underlines indicate N-methylated residues.46 (B) Most populated cluster from the explicit DMSO simulation of cyclo-(aAAAAA) using RSFF2.231 A representative structure and the Ramachandran plot for each residue are shown. Adapted from ref. 201 with permission from the PCCP Owner Societies. (C) Most populated cluster from the implicit DMSO simulation of cyclo-(aAAAAA) using AMBER96+GBSA/OBC (ε = 47).213,245–247 A representative structure and the Ramachandran plot for each residue are shown. The ϕ and ψ angles of the NMR structure are shown as black dots in the Ramachandran plots.

To tackle the CP conformational sampling problem, several enhanced sampling techniques have been applied.192–201 Two of the most common enhanced sampling techniques that have been applied to CP systems are replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD)208,209 and metadynamics (META).210,211 In REMD, several replicas are run in parallel, each at a different temperature. Throughout the simulation, exchanges are attempted between replicas at regular time intervals, allowing the conformational sampling of the low-temperature replicas to be enhanced by the high-temperature replicas.208,209 REMD simulations have been used to study the structural ensembles of several CPs.193,194,196,197 For example, Razavi et al. used a combination of computational screening and REMD simulations to design a CP that mimics a β-hairpin in LapD, a bacterial protein whose interaction with LapG is crucial to biofilm formation.194 Initially, implicit solvent REMD simulations were used to rapidly screen potential CP mimics. The four most favorable designs from the screening process were subsequently studied using explicit solvent simulations, ultimately leading to designs that mimic the LapD β-hairpin.

In REMD simulations, conformational sampling is enhanced for all degrees of freedom. However, if the slowest degree of freedom of the system is known, a more efficient enhanced sampling method such as META can be applied. In META, positive Gaussian hills are deposited along a specific reaction coordinate or collective variable (CV) at regular time intervals until the free energy surface along that CV is flat.210 To target multiple CVs at the same time, bias-exchange META (BE-META) simulations can be used, where multiple replicas are run in parallel, each biasing a different CV. At given time intervals, exchanges between replicas are attempted and the sampling of a single replica is enhanced by the sampling of the other replicas.211 BE-META simulations are the most effective at enhancing the conformational sampling when the slowest degrees of freedom can be identified and used as CVs. In a recent study, it was found that conformational changes of small CPs generally involve coupled dihedral changes of ϕi and ψi, or ψi and ϕi+1, and efficient conformational sampling could be achieved by targeting these coupled two-dihedral changes using BE-META.199 Using these essential transitional motions as CVs, systematic studies of cyclic hexapeptides in explicit water were performed, leading to the identification of a sequence with a single highly populated structure.200

As with any simulation of biomolecules, the reliability of CP structural prediction using MD simulations depends on the accuracy of the force field used. To study biomolecules, several force fields have been developed, including AMBER,212–219 CHARMM,220–222 GROMOS,223–225 OPLS-AA226–229 and residue-specific force fields.230,231 In general, current parameterization of protein force fields utilizes well-structured linear peptide and protein systems, whose ϕ and ψ dihedral angles typically occur in the α helix, β sheet and polyproline II regions of the Ramachandran plot. CPs, however, tend to have ϕ and ψ dihedral angles that fall outside these canonical regions, due to ring strain (Figure 2C).207 A recent study of a cyclic octapeptide, cyclo-(YNPFEEGG), showed that many peptide force fields tend to overstabilize these canonical regions of the ϕ/ψ space, leading to the mis-prediction of the NMR structure.198

In a 2016 study, Geng et al. compared how well four peptide force fields, Amber99sb-ildn,218 OPLS-AA/L,227 RSFF1230 and RSFF2,231 were able to predict the crystal structures of 20 all-trans CPs ranging in size from 5–12 amino acids.232 Here RSFF1 and RSFF2 are residue specific force fields 1 and 2, both of which were parameterized based on the protein coil library and were found to perform the best at predicting the CP crystal structures. For example, RSFF2 correctly recapitulated the crystal structures of 17 out of the 20 CPs with an RMSD < 1.1 Å.232 While RSFF2 appears promising at predicting CP structures, it is noted that all the 20 CP structures utilized in the study by Geng et al. were crystal structures of all-trans peptides composed of natural amino acids. Therefore, it remains to be tested whether RSFF2 can successfully predict solution structures of CPs, or those CPs containing cis peptide bonds and/or non-natural amino acids. In a recent study, it was shown that RSFF2 was not capable of reliably predicting the cis/trans isomers of simple N-methylated cyclic hexapeptides.201 Further optimization of the force field to describe the ratio between the cis and trans conformations is thus required if de novo structure prediction including the cis/trans isomer state is desired. Additionally, modifications of the force field to include non-natural amino acids would greatly enhance its utility for CP design.

Conclusions and perspectives

Owing to our current inability to reliably and efficiently predict CP structure and our poor understanding of CP sequence–structure relationships, it is currently difficult to design CPs to adopt specific conformations or to exhibit desired properties. For example, several methods have been developed to identify crucial binding regions in protein–protein interactions. These include the identification of “hot segments” using Rosetta Peptiderive,233–235 “hot loops” using LoopFinder,236–238 helical interfaces using HippDB239–241 and β-sheets at interfaces.242 Additionally, PepComposer developed a methodology to design peptides given a target structure and binding site.243 The capability to use CPs to mimic these regions could afford development of potent inhibitors of protein–protein interactions. We expect a better understanding of and ability to design CPs will ultimately emerge from a combined computational and experimental approach. In computationally understanding and designing CPs, current challenges include the need for the use of a computationally expensive explicit water model to describe CP–water interactions, the need for an efficient enhanced sampling technique to rapidly explore CP conformational space and the need for a force field to accurately predict the solution structures of CPs with potential cis peptide bonds and non-natural amino acids. In experimentally understanding and designing CPs, more efficient synthetic schemes and improved methods to characterize individual conformations within the structural ensembles of CPs will be beneficial. Combined, these two approaches will complement one another and provide synergistic feedback. The resolution of these challenges shall lead to an improved understanding of CP sequence–structure relationships and ultimately the ability to efficiently design CPs de novo.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01GM124160. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Hourani R, Zhang C, van der Weegen R, Ruiz L, Li C, Keten S, Helms BA, Xu T. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:15296. doi: 10.1021/ja2063082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sánchez-Quesada J, Kim HS, Ghadiri MR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:2503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brea RJ, Castedo L, Granja JR, Herranz MA, Sanchez L, Martin N, Seitz W, Guldi DM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609506104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Driggers EM, Hale SP, Lee J, Terrett NK. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:608. doi: 10.1038/nrd2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marsault E, Peterson ML. J Med Chem. 2011;54:1961. doi: 10.1021/jm1012374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yudin AK. Chem Sci. 2015;6:30. doi: 10.1039/c4sc03089c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiong J-P, Stehle T, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Frech M, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. Science. 2002;296:151. doi: 10.1126/science.1069040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kling A, Lukat P, Almeida DV, Bauer A, Fontaine E, Sordello S, Zaburannyi N, Herrmann J, Wenzel SC, Konig C, et al. Science. 2015;348:1106. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morse RP, Willett JLE, Johnson PM, Zheng J, Credali A, Iniguez A, Nowick JS, Hayes CS, Goulding CW. J Mol Biol. 2015;427:3766. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardote TAF, Ciulli A. ChemMedChem. 2016;11:787. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201500450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dathe M, Nikolenko H, Klose J, Bienert M. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9140. doi: 10.1021/bi035948v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wessolowski A, Bienert M, Dathe M. J Pept Res. 2004;64:159. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2004.00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appelt C, Wessolowski A, Soderhall JA, Dathe M, Schmieder P. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:1654. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craik DJ. Toxins. 2012;4:139. doi: 10.3390/toxins4020139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nawae W, Hannongbua S, Ruengjitchatchawalya M. Sci Rep. 2014;4:3933. doi: 10.1038/srep03933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman R, Danial M, Koh ML, Jolliffe KA, Perrier S. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:6023. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35172b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Santis P, Morosetti S, Rizzo R. Macromolecules. 1974;7:52. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghadiri MR, Granja JR, Buehler LK. Nature. 1994;369:301. doi: 10.1038/369301a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee DW, Kim BS. Plant Pathol J. 2015;31:1. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.RW.08.2014.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alcaro MC, Sabatino G, Uziel J, Chelli M, Ginanneschi M, Rovero P, Papini AM. J Pept Sci. 2004;10:218. doi: 10.1002/psc.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson DY, King DS, Chmielewski J, Singh S, Schultz PG. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:9391. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundquist JT, IV, Pelletier JC. Org Lett. 2002;4:3219. doi: 10.1021/ol026416u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Botti P, Pallin TD, Tam JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:10018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demmer O, Frank AO, Kessler H. In: Peptide and Protein Design for Biopharmaceutical Applications. Jensen KJ, editor. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2009. p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costil R, Lefebvre Q, Clayden J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:14602. doi: 10.1002/anie.201708991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendoza-Sanchez R, Corless VB, Nguyen QNN, Bergeron-Brlek M, Frost J, Adachi S, Tantillo DJ, Yudin AK. Chem Eur J. 2017;23:13319. doi: 10.1002/chem.201703616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitsiou C, Hindes JJ, I’Anson P, Jackson P, Wilson TC, Daly EK, Felstead HR, Hearnshaw P, Unsworth WP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:15794. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baud LG, Manning MA, Arkless HL, Stephens TC, Unsworth WP. Chem Eur J. 2017;23:2225. doi: 10.1002/chem.201605615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donald JR, Unsworth WP. Chem Eur J. 2017;23:8780. doi: 10.1002/chem.201700467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephens TC, Lodi M, Steer AM, Lin Y, Gill MT, Unsworth WP. Chem Eur J. 2017;23:13314. doi: 10.1002/chem.201703316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavone V, Lombardi A, Nastri F, Saviano M, Maglio O, D’Auria G, Quartara L, Maggi CA, Pedone C. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1995;2:987. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lombardi A, D’Auria G, Saviano M, Maglio O, Nastri F, Quartara L, Pedone C, Pavone V. Biopolymers. 1997;40:505. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0282(1996)40:5<505::aid-bip8>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lombardi A, D’Auria G, Maglio O, Nastri F, Quartara L, Pedone C, Pavone V. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:5879. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quartararo JS, Eshelman MR, Peraro L, Yu H, Baleja JD, Lin Y-S, Kritzer JA. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22:6387. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kopple KD, Go A, Logan RJJ, Savrda J. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:973. doi: 10.1021/ja00758a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tonelli AE, Brewster AI. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:2851. doi: 10.1021/ja00763a052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kopple KD, Go A, Schamper TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:4289. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blout ER. Biopolymers. 1981;20:1901. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varughese KI, Kartha G, Kopple KD. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:3310. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang C-H, Brown JN, Kopple KD. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:1715. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kopple KD, Wang Y-S, Cheng AG, Bhandary KK. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:4168. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stradley SJ, Rizo J, Bruch MD, Stroup AN, Gierasch LM. Biopolymers. 1990;29:263. doi: 10.1002/bip.360290130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alberg DG, Schreiber SL. Science. 1993;262:248. doi: 10.1126/science.8211144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kopple KD, Bean JW, Bhandary KK, Briand J, D’Ambrosio CA, Peishoff CE. Biopolymers. 1993;33:1093. doi: 10.1002/bip.360330711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marshall GR, Beusen DD, Nikiforovich GV. In: Peptides: Synthesis, Structures, and Applications. Gutte B, editor. 1995. p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beck JG, Chatterjee J, Laufer B, Kiran MU, Frank AO, Neubauer S, Ovadia O, Greenberg S, Gilon C, Hoffman A, et al. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:12125. doi: 10.1021/ja303200d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramakrishnan C, Paul PKC, Ramnarayan K. J Bioscience. 1985;8:239. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flippen JL, Karle IL. Biopolymers. 1976;15:1081. doi: 10.1002/bip.1976.360150605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ueno K, Shimizu T. Biopolymers. 1983;22:633. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Groth P. Acta Chem Scand. 1970;24:780. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swepston PN, Cordes AW, Kuyper LF, Meyer WL. Acta Cryst. 1981;B37:1139. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chiang CC, Karle IL. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1982;20:133. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1982.tb02665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ueda I, Ueda T, Sada I, Kato T, Mikuriya M, Kida S, Izumiya N. Acta Cryst. 1984;C40:111. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shoham G, Burley SK, Lipscomb WN. Acta Cryst. 1989;C45:1944. doi: 10.1107/s0108270189004257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chakraborty S, Tyagi P, Tai D-F, Lee G-H, Peng S-M. Molecules. 2013;18:4972. doi: 10.3390/molecules18054972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karle IL. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:1286. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gurrath M, Mullen G, Kessler H, Aumailley M, Timpl R. Eur J Biochem. 1992;210:911. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mierke DF, Kurz M, Kessler H. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:1042. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nagarajaram HA, Ramakrishnan C. J Bioscience. 1995;20:591. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davies JS. In: Cyclic Polymers. Semlyen ER, editor. 2000. p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nikiforovich GV, Kover KE, Zhang W-J, Marshall GR. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3262. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang X, Nikiforovich GV, Marshall GR. J Med Chem. 2007;50:2921. doi: 10.1021/jm070084n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heller M, Sukopp M, Tsomaia N, John M, Mierke DF, Reif B, Kessler H. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13806. doi: 10.1021/ja063174a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stroup AN, Rheingold AL, Rockwell AL, Gierasch LM. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:7146. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bruch MD, Rizo J, Gierasch LM. Biopolymers. 1992;32:1741. doi: 10.1002/bip.360321215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu Z-P, Gierasch LM. Biopolymers. 1992;32:1727. doi: 10.1002/bip.360321214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gierasch LM, Deber CM, Madison V, Niu C-H, Blout ER. Biochemistry. 1981;20:4730. doi: 10.1021/bi00519a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pavone V, Lombardi A, Yang X, Pedone C, Di Blasio B. Biopolymers. 1990;30:189. doi: 10.1002/bip.360311006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Di Blasio B, Lombardi A, Yang X, Pedone C, Pavone V. Biopolymers. 1991;31:1181. doi: 10.1002/bip.360311006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pavone V, Lombardi A, D’Auria G, Saviano M, Nastri F, Paolillo L, Di Blasio B, Pedone C. Biopolymers. 1992;32:173. doi: 10.1002/bip.360320207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Di Blasio B, Lombardi A, D’Auria G, Saviano M, Isernia C, Maglio O, Paolillo L, Pedone C, Pavone V. Biopolymers. 1993;33:621. doi: 10.1002/bip.360330411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pavone V, Lombardi A, Saviano M, Di Blasio B, Nastri F, Fattorusso R, Maglio O, Isernia C. Biopolymers. 1994;34:1505. doi: 10.1002/bip.360341108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pavone V, Lombardi A, Saviano M, Nastri F, Fattorusso R, Maglio O, Isernia C, Paolillo L, Pedone C. Biopolymers. 1994;34:1517. doi: 10.1002/bip.360341109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lombardi A, Saviano M, Nastri F, Maglio O, Mazzeo M, Peodone C, Isernia C, Pavone V. Biopolymers. 1996;38:683. doi: 10.1002/bip.360380602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lombardi A, Saviano M, Nastri F, Maglio O, Mazzeo M, Isernia C, Paolillo L, Pavone V. Biopolymers. 1996;38:693. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199602)38:6%3C693::AID-BIP2%3E3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dechantsreiter MA, Planker E, Matha B, Lohof E, Holzemann G, Jonczyk A, Goodman SL, Kessler H. J Med Chem. 1999;42:3033. doi: 10.1021/jm970832g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aumailley M, Gurrath M, Muller G, Calvete J, Timpl R, Kessler H. FEBS Lett. 1991;291:50. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81101-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Geyer A, Mueller G, Kessler H. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:7735. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Haubner R, Schmitt M, Holzemann G, Goodman SL, Jonczyk A, Kessler H. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7881. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lohof E, Planker E, Mang C, Burkhart F, Dechantsreiter MA, Haubner R, Wester H-J, Schwaiger M, Holzemann G, Goodman SL, et al. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:2761. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000804)39:15<2761::aid-anie2761>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wermuth J, Goodman SL, Jonczyk A, Kessler H. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:1328. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Samanen J, Ali F, Romoff T, Calvo R, Sorenson E, Vasko J, Storer B, Berry D, Bennett D, Strohsacker M, et al. J Med Chem. 1991;34:3114. doi: 10.1021/jm00114a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Craik DJ, Fairlie DP, Liras S, Price D. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2013;81:136. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Biron E, Chatterjee J, Ovadia O, Langenegger D, Brueggen J, Hoyer D, Schmid HA, Jelinek R, Gilon C, Hoffman A, et al. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:2595. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Doedens L, Opperer F, Cai M, Beck JG, Dedek M, Palmer E, Hruby VJ, Kessler H. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8115. doi: 10.1021/ja101428m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chatterjee J, Mierke D, Kessler H. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15164. doi: 10.1021/ja063123d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chatterjee J, Mierke DF, Kessler H. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:1508. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Laufer B, Chatterjee J, Frank AO, Kessler H. J Pept Sci. 2009;15:141. doi: 10.1002/psc.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.White TR, Renzelman CM, Rand AC, Rezai T, McEwen CM, Gelev VM, Turner RA, Linington RG, Leung SSF, Kalgutkar AS, et al. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:810. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bockus AT, Schwochert JA, Pye CR, Townsend CE, Sok V, Bednarek MA, Lokey RS. J Med Chem. 2015;58:7409. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hewitt WM, Leung SS, Pye CR, Ponkey AR, Bednarek M, Jacobson MP, Lokey RS. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:715. doi: 10.1021/ja508766b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fouche M, Schafer M, Berghausen J, Desrayaud S, Blatter M, Piechon P, Dix I, Garcia AM, Roth H-J. ChemMedChem. 2016;11:1048. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201600082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang CK, Craik DJ. Biopolymers. 2016;106:901. doi: 10.1002/bip.22878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nielsen DS, Shepherd NE, Xu W, Lucke AJ, Stoermer MJ, Fairlie DP. Chem Rev. 2017;117:8094. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Koay YC, Richardson NL, Zaiter SS, Kho J, Nguyen SY, Tran DH, Lee KW, Buckton LK, McAlpine SR. ChemMedChem. 2016;11:881. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201500572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Karle IL, Karle J. Acta Cryst. 1963;16:969. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Karle IL, Gibson JW, Karle J. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:3755. doi: 10.1021/ja00715a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kartha G, Ambady G, Shankar PV. Nature. 1974;247:204. doi: 10.1038/247204a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kartha G, Ambady GK. Acta Cryst. 1975;B31:2035. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brown JN, Teller RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:7565. doi: 10.1021/ja00440a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Druyan ME, Coulter CL, Walter R, Kartha G, Ambady GK. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:5496. doi: 10.1021/ja00434a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hossain MB, Van der Helm D. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:5191. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Brown JN, Yang CH. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:445. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hossain MB, Van der Helm D. Acta Cryst. 1979;B35:2781. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Karle IL. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:181. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kostansek EC, Lipscomb WN, Thiessen WE. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:834. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kostansek EC, Thiessen WE, Schomburg D, Lipscomb WN. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:5811. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Barnes CL, Van der Helm D. Acta Cryst. 1982;B38:2589. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Czugler M, Sasvari K, Hollosi M. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4465. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Steyn PS, Tuinman AA, van Heerden FR, van Rooyen PH, Wessels PL, Rabie CJ. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1983;1983:47. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kartha G, Bhandary KK, Kopple KD, Go A, Zhu P-P. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:6844. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nakashima T, Yamane T, Tanaka I, Ashida T. Acta Cryst. 1984;C40:171. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gierasch LM, Karle IL, Rockwell AL, Yenal K. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:3321. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kopple KD, Kartha G, Bhandary KK, Romanowska K. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:4893. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Karle IL. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1986;28:420. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1986.tb03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kartha G, Aimoto S, Varughese KI. Chem Biol Drug Des. 1986;27:112. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1986.tb01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kessler H, Klein M, Muller A, Wagner K, Bats JW, Ziegler K, Frimmer M. Angew Chem. 1986;25:997. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kopple KD, Bhandary KK, Kartha G, Wang YS, Parameswaran KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:4637. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Stroup AN, Rockwell AL, Rheingold AL, Gierasch LM. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:5157. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Pavone V, Benedetti E, Di Blasio B, Lombardi A, Pedone C, Tomasich L, Lorenzi GP. Biopolymers. 1989;28:215. doi: 10.1002/bip.360280123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Barnes CL, Hassain MB, Fidelis K, Van der Helm D. Acta Cryst. 1990;B46:238. doi: 10.1107/s0108768189010633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Declercq JP, Tinant B, Bashwira S, Hootele C. Acta Cryst. 1990;C46:1259. doi: 10.1107/s0108270189010656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bhandary KK, Kopple KD. Acta Cryst. 1991;C47:1280. doi: 10.1107/s0108270190012860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bhandary KK, Kopple KD. Acta Cryst. 1991;C47:1483. doi: 10.1107/s0108270190012860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Eggleston DS, Baures PW, Peishoff CE, Kopple KD. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4410. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kessler H, Matter H, Gemmecker G, Kottenhahn M, Bats JW. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:4805. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pettit GR, Srirangam JK, Herald DL, Erickson KL, Doubek DL, Schmidt JM, Tackett LP, Bakus GJ. J Org Chem. 1992;57:7217. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Morita H, Kayashita T, Takeya K, Itokawa H, Shiro M. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:12539. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Morita H, Yun YS, Takeya K, Itokawa H, Shiro M. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:5987. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pettit GR, Srirangam JK, Herald DL, Xu J-P, Boyd MR, Cichacz Z, Kamano Y, Schmidt JM, Erickson KL. J Org Chem. 1995;60:8257. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Morita H, Kayashita T, Takeya K, Itokawa H, Shiro M. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:1607. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Zanotti G, Saviano M, Saviano G, Tancredi T, Rossi F, Pedone C, Benedetti E. J Pept Res. 1998;51:460. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1998.tb00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Dittrich B, Koritsanszky T, Grosche M, Scherer W, Flaig R, Wagner A, Krane HG, Kessler H, Riemer C, Schreurs AMM, et al. Acta Cryst. 2002;B58:721. doi: 10.1107/s0108768102005839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wang C, Zhang L-L, Lu Y, Zheng Q-T, Cheng Y-X, Zhou J, Tan N-H. J Mol Struct. 2004;688:67. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wiiliams DE, Patrick BO, Behrisch HW, Van Soest R, Roberge M, Andersen RJ. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:327. doi: 10.1021/np049711r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wu L, Lu Y, Zheng Q-T, Tan N-H, Li C-M, Zhou J. J Mol Struct. 2007;827:145. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Dolle RE, Michaut M, Martinez-Teipel B, Seida PR, Ajello CW, Muller AL, DeHaven RN, Carroll PJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:3647. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.04.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Vicente J, Vera B, Rodriguez AD, Rodriguez-Escudero I, Raptis RG. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:4571. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.05.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Wélé A, Mayer C, Quentin D, Zhang Y, Blond A, Bodo B. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:275. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Tian J-M, Ou-Yang S-S, Zhang X, Di Y-T, Jiang H-L, Li H-L, Dai W-X, Chen K-Y, Liu M-L, Hao X-J, et al. RSC Adv. 2012;2:1126. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Tong Y, Luo JG, Wang R, Wang XB, Kong LY. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:1908. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Torchia DA, Di Corato A, Wong SCK, Deber CM, Blout ER. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:609. doi: 10.1021/ja00757a048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Torchia DA, Wong SCK, Deber CM, Blout ER. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:616. doi: 10.1021/ja00757a049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Pease LG, Watson C. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:1279. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Pease LG, Niu CH, Zimmermann G. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:184. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Williamson KL, Pease LG, Roberts JD. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:714. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Bach AC, ll, Bothner-By AA, Gierasch LM. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:572. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Bruch MD, Noggle JH, Gierasch LM. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:1400. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kessler H, Bats JW, Griesinger C, Koll S, Will M, Wagner K. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:1033. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Bean JW, Kopple KD, Peishoff CE. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:5328. [Google Scholar]

- 151.Stroup AN, Rockwell AL, Gierasch LM. Biopolymers. 1992;32:1713. doi: 10.1002/bip.360321213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Kobayashi J, Tsuda M, Nakamura T, Mikami Y, Shigemori H. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:2391. [Google Scholar]

- 153.Pettit GR, Cichacz Z, Barkoczy J, Dorsaz A-C, Herald DL, Williams MD, Doubek DL, Schmidt JM, Tackett LP, Brune DC, et al. J Nat Prod. 1993;56:260. doi: 10.1021/np50092a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Tsuda M, Shigemori H, Mikami Y, Kobayashi J. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:6785. [Google Scholar]

- 155.Ma S, McGregor MJ, Cohen FE, Pallai PV. Biopolymers. 1994;34:987. doi: 10.1002/bip.360340802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Morita H, Kayashita T, Kobata H, Gonda A, Takeya K, Itokawa H. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:9975. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Pettit GR, Gao F, Cerny RL, Doubek DL, Tackett LP, Schmidt JM, Chapuis J-C. J Med Chem. 1994;37:1165. doi: 10.1021/jm00034a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Morita H, Kayashita T, Shimomura M, Takeya K, Itokawa H. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:280. doi: 10.1021/np960123q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Morita H, Kayashita T, Shishido A, Takeya K, Itokawa H, Shiro M. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:1165. [Google Scholar]

- 160.Bonnington LS, Tanaka J, Higa T, Kimura J, Yoshimura Y, Nakao Y, Yoshida WY, Scheuer PJ. J Org Chem. 1997;62:7765. [Google Scholar]

- 161.Satoh T, Aramini JM, Li S, Friedman TM, Gao J, Edling AE, Townsend R, Koch U, Choksi S, Germann MW, et al. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Tan LT, Williamson RT, Gerwick WH. J Org Chem. 2000;65:419. doi: 10.1021/jo991165x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Desai P, Prachand M, Coutinho E, Saran A, Bodi J, Suli-Vargha H. Int J Biol Macromolec. 2002;30:187. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(02)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Tan LT, Cheng XC, Jensen PR, Fenical W. J Org Chem. 2003;63:8767. doi: 10.1021/jo030191z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Mohammed R, Peng J, Kelly M, Hammann MT. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1739. doi: 10.1021/np060006n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Mongkolvisut W, Sutthivaiyakit S, Leutbecher H, Mika D, Klaiber I, Möller W, Rösner H, Beifuss U, Conrad J. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1435. doi: 10.1021/np0602012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Wélé A, Mayer C, Dermigny Q, Zhang Y, Blond A, Bodo B. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:154. [Google Scholar]

- 168.Williams DE, Yu K, Behrisch HW, Van Soest R, Andersen RJ. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:1253. doi: 10.1021/np900121m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Cychon C, Kock M. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:738. doi: 10.1021/np900664f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Zhao J, Zhou LL, Li X, Xiao HB, Hou FF, Cheng YX. J Nat Prod. 2011;74:1392. doi: 10.1021/np200048u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Aviles E, Rodriguez AD. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:10797. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2013.10.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Brookes DH, Head-Gordon T. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:4530. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Bhowmick A, Brookes DH, Yost SR, Dyson HJ, Forman-Kay JD, Gunter D, Head-Gordon M, Hura GL, Pande VS, Wemmer DE, et al. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:9730. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Best RB. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;42:147. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Bonomi M, Heller GT, Camilloni C, Vendruscolo M. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;42:106. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Rayan A, Senderowitz H, Goldblum A. J Mol Graphics Model. 2004;22:319. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Izrailev S, Zhu F, Agrafiotis DK. J Comput Chem. 2006;27:1962. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Li J, Ehlers T, Sutter J, Varma-O’Brien S, Kirchmair J. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:1923. doi: 10.1021/ci700136x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Zhu F, Agrafiotis DK. J Comput Chem. 2007;28:1234. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Hawkins PCD, Skillman AG, Warren GL, Ellingson BA, Stahl MT. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50:572. doi: 10.1021/ci100031x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Duffy FJ, Verniere M, Devocelle M, Bernard E, Shields DC, Chubb AJ. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:829. doi: 10.1021/ci100431r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Jacobson MP, Pincus DL, Rapp CS, Day TJ, Honig B, Shaw DE, Friesner RA. Proteins. 2004;55:351. doi: 10.1002/prot.10613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Thomas A, Deshayes S, Decaffmeyer M, Van Eyck MH, Charloteaux B, Brasseur R. Proteins. 2006;65:889. doi: 10.1002/prot.21151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Zhang Y. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Mandell DJ, Coutsias EA, Kortemme T. Nat Methods. 2009;6:551. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0809-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Beaufays J, Lins L, Thomas A, Brasseur R. J Pept Sci. 2012;18:17. doi: 10.1002/psc.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Thevenet P, Shen Y, Maupetit J, Guyon F, Derreumaux P, Tuffery P. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W288. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Chen IJ, Foloppe N. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:7898. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Shen Y, Maupetit J, Derreumaux P, Tuffery P. J Chem Theory Comput. 2014;10:4745. doi: 10.1021/ct500592m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Watts KS, Dalal P, Tebben AJ, Cheney DL, Shelley JC. J Chem Inf Model. 2014;54:2680. doi: 10.1021/ci5001696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Singh S, Singh H, Tuknait A, Chaudhary K, Singh B, Kumaran S, Raghava GPS. Biol Direct. 2015;10:73. doi: 10.1186/s13062-015-0103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Spitaleri A, Ghitti M, Mari S, Alberici L, Traversari C, Rizzardi GP, Musco G. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:1832. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Damas JM, Filipe LCS, Campos SRR, Lousa D, Victor BL, Baptista AM, Soares CM. J Chem Theory Comput. 2013;9:5148. doi: 10.1021/ct400529k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Razavi AM, Wuest WM, Voelz VA. J Chem Inf Model. 2014;54:1425. doi: 10.1021/ci500102y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.Paissoni C, Ghitti M, Belvisi L, Spitaleri A, Musco G. Chem Eur J. 2015;21:14165. doi: 10.1002/chem.201501196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.Wakefield AE, Wuest WM, Voelz VA. J Chem Inf Model. 2015;55:806. doi: 10.1021/ci500768u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Yedvabny E, Nerenberg PS, So C, Head-Gordon T. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:896. doi: 10.1021/jp505902m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198.Yu H, Lin Y-S. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2015;17:4210. doi: 10.1039/c4cp04580g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199.McHugh SM, Rogers JR, Yu H, Lin Y-S. J Chem Theory Comput. 2016;12:2480. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 200.McHugh SM, Yu H, Slough DP, Lin Y-S. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2017;19:3315. doi: 10.1039/c6cp06192c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 201.Slough DP, Yu H, McHugh SM, Lin Y-S. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2017;19:5377. doi: 10.1039/c6cp07700e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 202.Tayar NE, Mark AE, Vallet P, Brunne RM, Testa B, van Gunsteren WF. J Med Chem. 1993;36:3757. doi: 10.1021/jm00076a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 203.Butterfoss GL, Yoo B, Jaworski JN, Chorny I, Dill KA, Zuckermann RN, Bonneau R, Kirshenbaum K, Voelz VA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:14320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209945109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 204.Chen Y, Deng K, Qiu X, Wang C. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2461. doi: 10.1038/srep02461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 205.Merten C, Li F, Bravo-Rodriguez K, Sanchez-Garcia E, Xu Y, Sander W. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16:5627. doi: 10.1039/c3cp55018d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 206.Riemann RN, Zacharias M. J Pept Res. 2004;63:354. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2004.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 207.McHugh SM, Rogers JR, Solomon SA, Yu H, Lin Y-S. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2016;34:95. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 208.Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Chem Phys Lett. 1999;314:141. [Google Scholar]

- 209.Earl DJ, Deem MW. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2005;7:3910. doi: 10.1039/b509983h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 210.Laio A, Parrinello M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202427399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 211.Piana S, Laio A. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:4553. doi: 10.1021/jp067873l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 212.Cornell WD, Cieplak P, Bayly CI, Gould IR, Merz KMJ, Ferguson DM, Spellmeyer DC, Fox T, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:5179. [Google Scholar]

- 213.Kollman PA. Acc Chem Res. 1996;29:461. [Google Scholar]

- 214.Wang J, Cieplak P, Kollman PA. J Comput Chem. 2000;21:1049. [Google Scholar]

- 215.Duan Y, Wu C, Chowdhury S, Lee MC, Xiong G, Zhang W, Yang R, Cieplak P, Luo R, Lee T, et al. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:1999. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 216.Hornak V, Abel R, Okur A, Strockbine B, Roitberg A, Simmerling C. Proteins. 2006;65:712. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 217.Best RB, Hummer G. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:9004. doi: 10.1021/jp901540t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 218.Lindorff-Larsen K, Piana S, Palmo K, Maragakis P, Klepeis JL, Dror RO, Shaw DE. Proteins. 2010;78:1950. doi: 10.1002/prot.22711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 219.Gao Y, Li Y, Mou L, Hu W, Zheng J, Zhang JZ, Mei Y. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:4188. doi: 10.1021/jp510215c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 220.Mackerell AD, Jr, Bashford D, Bellott M, LDR, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, et al. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 221.Mackerell AD, Jr, Feig M, Brooks CL., 3rd J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1400. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 222.Piana S, Lindorff-Larsen K, Shaw DE. Biophys J. 2011;100:L47. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 223.Schuler LD, Daura X, van Gunsteren WF. J Comput Chem. 2001;22:1205. [Google Scholar]

- 224.Oostenbrink C, Villa A, Mark AE, van Gunsteren WF. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1656. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 225.Schmid N, Eichenberger AP, Choutko A, Riniker S, Winger M, Mark AE, van Gunsteren WF. Eur Biophys J. 2011;40:843. doi: 10.1007/s00249-011-0700-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 226.Jorgensen WL, Maxwell DS, Tirado-Rives J. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:11225. [Google Scholar]

- 227.Kaminski GA, Friesner RA, Tirado-Rives J, Jorgensen WL. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:6474. [Google Scholar]

- 228.Robertson MJ, Tirado-Rives J, Jorgensen WL. J Chem Theory Comput. 2015;11:3499. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 229.Harder E, Damm W, Maple J, Wu C, Reboul M, Xiang JY, Wang L, Lupyan D, Dahlgren MK, Knight JL, et al. J Chem Theory Comput. 2016;12:281. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 230.Jiang F, Zhou C-Y, Wu Y-D. J Phys Chem B. 2014;118:6983. doi: 10.1021/jp5017449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 231.Zhou C-Y, Jiang F, Wu Y-D. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:1035. doi: 10.1021/jp5064676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 232.Geng H, Jiang F, Wu Y-D. J Phys Chem Lett. 2016;7:1805. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 233.London N, Raveh B, Movshovitz-Attias D, Schueler-Furman O. Proteins. 2010;78:3140. doi: 10.1002/prot.22785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 234.London N, Raveh B, Schueler-Furman O. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:952. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 235.Sedan Y, Marcu O, Lyskov S, Schueler-Furman O. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W536. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 236.Gavenonis J, Sheneman BA, Siegert TR, Eshelman MR, Kritzer JA. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:716. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 237.Siegert TR, Bird MJ, Makwana KM, Kritzer JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:12876. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 238.Siegert TR, Bird M, Kritzer JA. In: Methods in Molecular Biology. Schueler-Furman O, London N, editors. Vol. 1561. Humana Press; New York, NY: 2017. p. 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 239.Jochim AL, Arora PS. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:919. doi: 10.1021/cb1001747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 240.Bullock BN, Jochim AL, Arora PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14220. doi: 10.1021/ja206074j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 241.Bergey CM, Watkins AM, Arora PS. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2806. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 242.Watkins AM, Arora PS. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:1747. doi: 10.1021/cb500241y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 243.Obarska-Kosinska A, Iacoangeli A, Lepore R, Tramontano A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W522. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 244.Lovell SC, Davis IW, Arendall WB, III, de Bakker PIW, Word JM, Prisant MG, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Proteins. 2003;50:437. doi: 10.1002/prot.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 245.Still WC, Tempczyk A, Hawley RC, Hendrickson T. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:6127. [Google Scholar]

- 246.Onufriev A, Bashford D, Case DA. Proteins. 2004;55:383. doi: 10.1002/prot.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 247.Shell MS, Ritterson R, Dill KA. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:6878. doi: 10.1021/jp800282x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]