Abstract

Purpose

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection plays a critical role in the process of gastric carcinogenesis. However, the complicated pathogenic mechanism is still unclear. Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) is involved in the development of multiple human malignancies, including gastric cancer. Therefore, this study aimed to elucidate the role of PLK1 in H. pylori-induced gastric carcinogenesis and the underlying signaling mechanism.

Materials and methods

We detected the expression of PLK1 in 166 patients in different stages of gastric carcinogenesis as well as the established Mongolian gerbil model with H. pylori infection by immunohistochemistry. Cell Counting Kit-8 was used to estimate the survival of gastric cancer cells.

Results

We found that PLK1 expression in gastric cancer tissues was significantly higher than that of paired adjacent mucosa. PLK1 expression was increased in intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and gastric cancer tissues compared to chronic non-atrophic gastritis tissues. Notably, PLK1 expression was much lower in H. pylori-negative tissues than in H. pylori-positive tissues at intestinal metaplasia stage. In addition, H. pylori infection increased PLK1 expression in the gastric epithelial cells of the Mongolian gerbil model, which was positively related to the duration of H. pylori infection. Inhibition of PLK1 significantly reduced H. pylori-induced cell proliferation. Furthermore, incubation of MKN-28 cells with H. pylori resulted in a significant increase in PLK1, p-PTEN, and the downstream PI3K/Akt pathway, and pretreatment with a PLK1 inhibitor reversed these molecular changes.

Conclusion

PLK1 is involved in H. pylori-induced gastric carcinogenesis at the early stage by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. These results may contribute to the development of new control strategies for H. pylori infection-related gastric cancer.

Keywords: gastric carcinogenesis, Helicobacter pylori, PLK1, PI3K/Akt pathway, cell survival

Introduction

Gastric cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide and the third and fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths among females and males, respectively. Despite the decrease in incidence and mortality, gastric cancer is still one of the heaviest health burdens worldwide.1,2 To date, surgical resection remains the preferred curative method to improve survival of gastric cancer patients. However, for patients who have reached the terminal stage or are not accepted for surgical treatment, chemotherapy is an alternative, but it has some limitations due to its serious side effects.3 Therefore, it is necessary to elucidate the mechanism underlying gastric cancer development and progression, which will help to develop novel and effective strategies for gastric cancer treatment.

Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) is a serine/threonine kinase that participates in the regulation of various processes, including mitosis, cytokinesis, and the DNA damage response.4 A number of studies have shown that PLK1 is highly expressed in multiple digestive tumors, such as esophageal cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, liver cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, and pancreatic cancer.5–10 Additionally, the high expression of PLK1 in gastric cancer is positively related to tumor stage, metastasis, invasion, and poor prognosis.6,11,12

Helicobacter pylori is a common bacterium with a high infection rate, which shows severe pathogenicity. With its unique virulence factors, it can adapt to the highly acidic microenvironment in the stomach cavity, colonize in the host body for a long period of time, and then induce a series of related diseases. Epidemiology confirms that gastritis, peptic ulcer, non-cardia gastric cancer, and low-grade B-cell MALT lymphoma are all associated with H. pylori infection.13,14 As early as 1994, the International Agency for Research on Cancer defined H. pylori as a class I carcinogen for gastric cancer, and it may act as a “promoter” to trigger the following cascade lesions: normal gastric mucosa – chronic non-atrophic gastritis – atrophic gastritis – intestinal epithelial metaplasia – dysplasia – gastric cancer.15 According to the data from WHO in 2012, approximately 15.4% of cancers worldwide were attributed to infection. Among these infections, H. pylori infection, which causes gastric cancer, ranks first (35.4%). In China, approximately 24.2% of cancers were attributed to infection, and H. pylori infection-related cancer accounted for 45%.16 In 2015, the Kyoto global consensus report directly defined H. pylori-positive gastritis as an infectious disease and included it in the “International Classification of Diseases”.17 At the same time, it passed a new consensus that once H. pylori infection is detected, patients need to accept eradication therapy.

H. pylori infection plays a critical role in the process of carcinogenesis through a series of complex regulations. It can promote the proliferation of epithelial cells and directly activate signaling pathways related to early proliferation, leading to increased DNA synthesis and a higher risk of malignant tumors.18 In our previous study, we found that H. pylori could accelerate PTEN phosphorylation, which activated the PI3K/Akt signaling and promoted cell survival.19 Furthermore, PLK1 was reported to induce PTEN phosphorylation, activating the PI3K/Akt pathway, which increases tumor susceptibility.20 Therefore, in this study, we aimed to determine the role of PLK1 in H. pylori infection-induced gastric carcinogenesis. In addition, the effect of H. pylori infection on PLK1/p-PTEN/PI3K/Akt signaling was assessed to identify its underlying mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue specimens

A total of 166 gastric tissue samples were collected from patients who underwent a gastroduodenoscopy at The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University from January 2010 to February 2017, which included 38 cases of chronic non-atrophic gastritis (18 H. pylori positive, 20 H. pylori negative), 43 cases of intestinal metaplasia (21 H. pylori positive, 22 H. pylori negative), 40 cases of dysplasia (20 H. pylori positive, 20 H. pylori negative), and 45 cases of gastric cancer (23 H. pylori positive, 22 H. pylori negative). The clinical characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table 1, and there was no significant difference in the age and gender distribution among these groups. Pathologic diagnosis and classification were carried out as previously described, and all patients were examined for H. pylori infection using Giemsa staining and a rapid urease test.21 This study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee and the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. Written informed consent was obtained from the study subjects.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with different stages of gastric carcinogenesis

| Group | n | Gender

|

Age, years (mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| CNAG | 38 | 19 | 19 | 50.16±11.02 |

| IM | 43 | 21 | 22 | 54.26±9.06 |

| Dys | 40 | 21 | 19 | 53.63±10.55 |

| GC | 45 | 23 | 22 | 56.80±12.14 |

| Total | 166 | 84 | 82 | 53.86±11.01 |

Abbreviations: CNAG, chronic non-atrophic gastritis; IM, intestinal metaplasia; Dys, dysplasia; GC, gastric cancer.

Mongolian gerbils

Five- to eight-week-old specific-pathogen-free male Mongolian gerbils (30–50 g) were provided by Zhejiang Academy of Medical Sciences (Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China). As previously described, they were maintained in an isolated clean room with a regulated temperature (20°C–22°C), humidity (approximately 55%), and 12/12-h light/dark cycle, with ad libitum rodent diet and water, and then infected with H. pylori after 1 week of observation.17 Animals were euthanized at 6 months, 12 months, and 18 months post-infection, and linear strips of gastric tissue extending from the squamocolumnar junction through the proximal duodenum were collected.19 All protocols for animal experiments using gerbils were approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (No: 018).

H. pylori strain and cell lines

The CagA+ and VagA+ H. pylori type strain ATCC43504 was obtained from the National Institute for Communicable Diseases and Prevention of Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Beijing, China). H. pylori was cultured on Campylobacter agar plates at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions for 24 h and then subcultured in Brucella broth (Shanghai Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 37°C under a microaerophilic atmosphere for 16–18 h.19 Gastric cancer MKN-28 cells were obtained from the Beijing Institute for Cancer Research (Beijing, China). MKN-28 was cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Reagents

Inhibition of PLK1 was achieved with BI2536 (200 nM; Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA) and a CCK-8 kit (BB-4202-2; BestBio, Shanghai, China) was used.

Immunoblotting

Western blotting was performed according to standard methods as described previously21 using anti-PTEN (#9559; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; 1:1,000), anti-phosphorylated (p)-PTEN (Ser380/Thr382/383) (#9554; Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1,000), anti-PI3K (#4249; Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1,000), anti-Akt (#4691; Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1,000), anti-phosphorylated (p)-Akt (Ser473) (#9271; Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1,000), anti-Cyclin D1 (#2978; Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1,000), anti-Bad (#9239; Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1,000), anti-phosphorylated (p)-Bad (Ser136) (#4366; Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1,000), anti-GAPDH (#2118; Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1,000), and anti-PLK1 antibodies (ab17056; 1:1,000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin sections of human biopsy specimens or Mongolian gerbil gastric tissues using an anti-PLK1 antibody (ab17056; 1:400 [biopsy], [human gastric tissues]; 1:200 [biopsy], [Mongolian gerbil gastric tissues]; Abcam) following previously described methods.21 The negative control sections were incubated with PBS without the primary antibodies. The stained sections were chosen, reviewed, and scored from five randomly selected high-power fields (40× objective lens) by two pathologists blinded to the histopathologic data. Grading discrepancies were re-reviewed and discussed to obtain a final score. Epithelial cells with yellow or brown staining in the nucleus and/or cytoplasm were defined as positive for immunoreactivity. The percentage of immunoreactive cells from 100 cells in each field was averaged from the five fields and scored as follows: 0 <5.0% immunoreactive; 1 = 5.1%–25.0%; 2 = 25.1%–50.0%; 3 = 50.1%–75.0%; and 4 >75.0%. Moreover, the staining intensity was also semi quantitatively assessed as follows: 0 = no staining; 1 = weak staining; 2 = moderate staining; and 3 = strong staining. The overall protein expression level was then reported as a grade calculated from an integral score of the “area × intensity” as follows: grade 1 = score 0–2 (negative); grade 2 = score 3–5 (weakly positive); grade 3 = score 6–8 (moderately positive); and grade 4 = score 9–12 (strongly positive).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as a percentage of the control or the mean ± SD. Differences in categorical variables were examined using chi-square tests. Differences in numerical variables, such as patient age, were analyzed using ANOVA among the groups. The differences in numerical variables between differently defined groups were evaluated using Kruskal–Wallis tests or Mann–Whitney tests. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

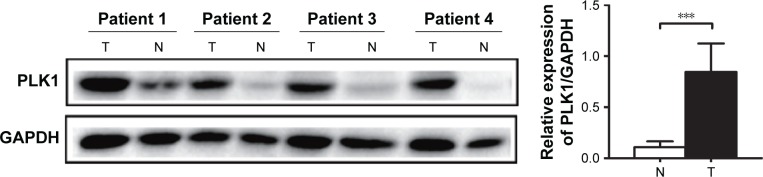

PLK1 is upregulated in gastric cancer tissues

Western blot was performed to assess PLK1 expression in protein samples from gastric cancer tissues and the paired adjacent mucosa of patients. An increase in PLK1 expression was detected in gastric cancer tissues compared to the paired adjacent mucosa (23/26, 88.46%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PLK1 is upregulated in gastric cancer tissues. Expression level of PLK1 was measured in gastric tumor samples (T) and their non-cancerous counterparts (N). GAPDHwas used as an internal control. Densitometric units of T are expressed as a fold of its corresponding N. ***p<0.001.

Abbreviation: PLK1, polo-like kinase 1.

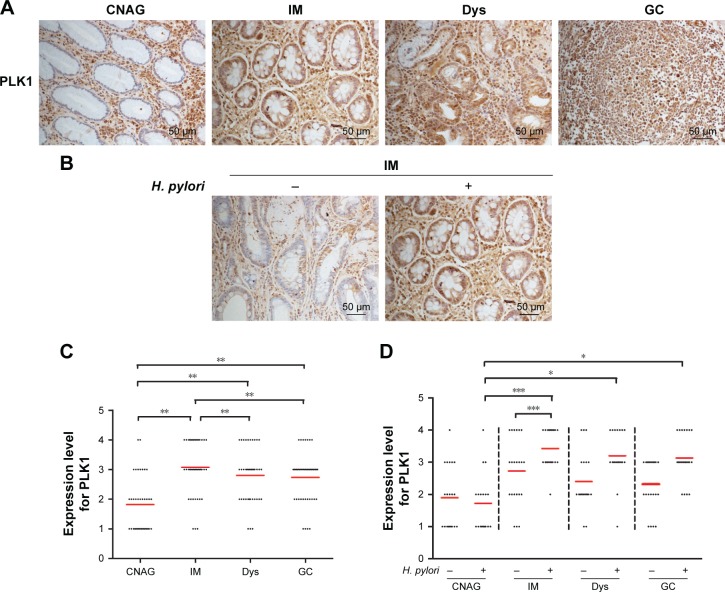

Expression of PLK1 in different stages of gastric carcinogenesis in relation to H. pylori infection

Immunohistochemistry was performed to evaluate the expression of PLK1 in patients with different stages of gastric carcinogenesis. PLK1 was increased in intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and gastric cancer tissues compared to chronic non-atrophic gastritis tissues (p<0.01), and PLK1 was significantly lower in intestinal metaplasia than dysplasia and gastric cancer (p<0.05, p<0.01) (Figure 2A and C). These data suggest that PLK1 may contribute to gastric carcinogenesis at the early stage.

Figure 2.

Expression of PLK1 in different stages of gastric carcinogenesis in relation to Helicobacter pylori. Gastric tissue samples were stained with antibodies against PLK1; (A) immunoreactive cells positive for PLK1 were semi quantitatively assessed and the protein expression levels are expressed as grade 1–4; (B) all patients in various stages of gastric lesions; (C, D) patients with various stages of gastric lesions with or without H. pylori infection. Mean grades () for protein expression are shown. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Abbreviations: PLK1, polo-like kinase 1; CNAG, chronic non-atrophic gastritis; IM, intestinal metaplasia; Dys, dysplasia; GC, gastric cancer.

As it has been postulated that H. pylori infection may trigger gastric carcinogenesis, the same cohort of patients were divided into H. pylori-positive and -negative groups, and the expression of PLK1 was compared between these two groups. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that there was a significant difference among these four groups in H. pylori-positive patients. PLK1 expression was decreased in chronic non-atrophic gastritis compared to intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and gastric cancer tissues from H. pylori-positive tissues (p<0.05) (Figure 2D). Furthermore, in intestinal metaplasia tissues, PLK1 was much higher in H. pylori-positive patients than in H. pylori-negative patients (p<0.001) (Figure 2B and D). These results suggest that PLK1 is related to H. pylori infection in the process of gastric carcinogenesis.

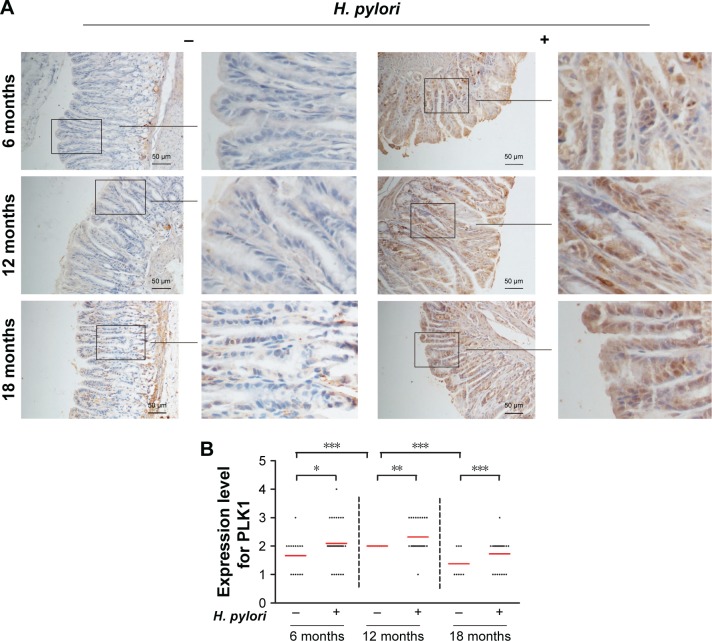

H. pylori infection induces high expression of PLK1 in gastric tissue from Mongolian gerbils

To confirm that PLK1 is related to H. pylori infection in the process of gastric carcinogenesis in vivo, we performed immunohistochemical analysis of PLK1 in gastric tissue samples of Mongolian gerbils with or without H. pylori infection. Our results showed that expression of PLK1 was greatly enhanced in the H. pylori-positive group compared to the H. pylori-negative group at all time points, such as at the 6th month, the 12th month, and the 18th month post-bacterial inoculation (p<0.05, p<0. 01, p<0.001). In addition, the significance was more obvious with longer H. pylori infection (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Helicobacter pylori infection induces high expression of PLK1 in gastric tissue from Mongolian gerbils. (A) Gastric tissue sections from H. pylori-infected gerbils were stained with antibodies against PLK1. (B) Immunoreactive cells were semi quantitatively assessed and the protein expression levels are expressed as grade 1–4. Mean grades () for protein expression are shown. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Abbreviation: PLK1, polo-like kinase 1.

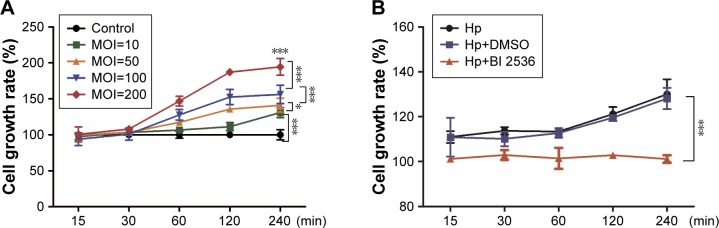

PLK1 is involved in H. pylori-promoted cancer cell proliferation

Cell proliferation assessment using a CCK8 assay showed that H. pylori could increase MKN-28 cell viability in both dose- and time-dependent manner (p<0.05) (Figure 4A). To determine the role of PLK1 in H. pylori-promoted cancer cell proliferation, MKN-28 cells were pretreated with the pharmacological PLK1 inhibitor BI 2536. As expected, the growth rate of MKN-28 cells significantly decreased even with H. pylori (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 200) infection after pretreatment with BI 2536, and the viability of cells pretreated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) had a similar trend to that observed in untreated cells (p<0.05) (Figure 4B), suggesting that H. pylori infection also induces cell survival in vitro and that PLK1 is involved in the regulation.

Figure 4.

PLK1 is involved in Helicobacter pylori-promoted cancer cell proliferation. Cell survival was evaluated by a CCK-8 assay and the cell growth rate was expressed as a percentage of the control or MKN-28 cells at various time points after (A) incubation with different doses of H. pylori (MOI = 10, 50, 100, 200) and (B) pretreatment with an inhibitor of PLK1 BI 2536. The data are representative of three independent experiments. *p<0.05; ***p<0.001.

Abbreviations: MOI, multiplicity of infection; PLK1, polo-like kinase 1.

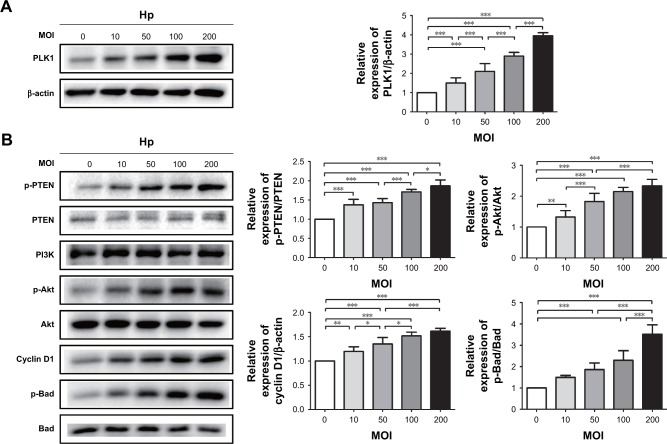

H. pylori infection induces PLK1-mediated activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway

Incubation of MKN-28 cells with different doses of H. pylori (MOI = 10, 50, 100, 200) resulted in a dose-dependent increase of PLK1 (Figure 5A). At the same time, we observed gradually enhanced expression of p-PTEN, p-Akt, cyclin D1, and p-Bad with the increased dose of H. pylori infection (p<0.05) (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Helicobacter pylori infection induces PLK1-mediated activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway in a dose-dependent manner. Cultures of MKN-28 cells were incubated with various doses of H. pylori (at 2 h) in the H. pylori group or with medium in control group. Immunoblotting was used to quantify the expression levels of PLK1 (A) and Akt pathway-related proteins (B). The data are representative of three independent experiments. The samples were derived from the same experiment, and the blots were processed in parallel. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Abbreviations: PLK1, polo-like kinase 1; MOI, multiplicity of infection.

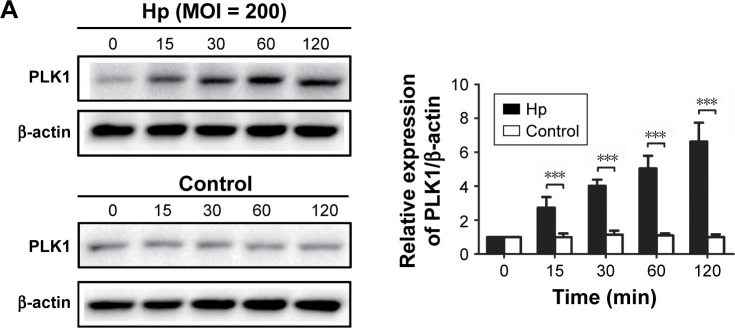

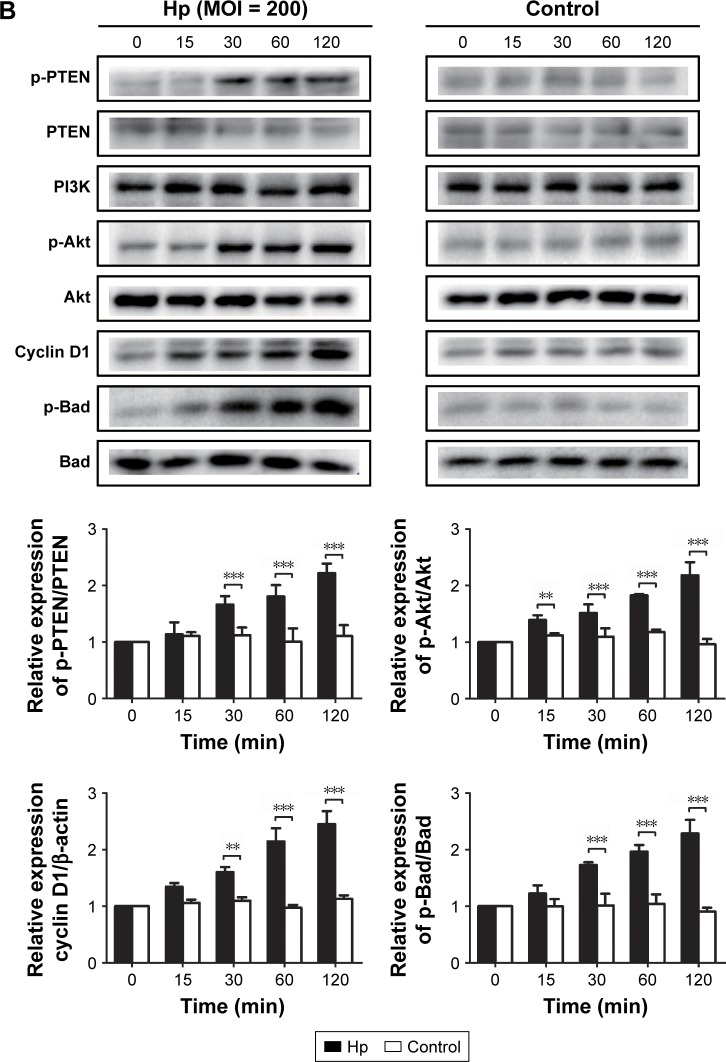

To further confirm the effect of H. pylori infection on activation of the PLK1 and Akt pathway, we incubated MKN-2 8 cells with H. pylori (MOI = 200) at different time points. We found that the expression levels of PLK1 and cyclin D1 and the ratios of p-PTEN/PTEN, p-Akt/Akt, and p-Bad/Bad were increased in a time-dependent manner (p<0.05); however, there were no significant differences in the control (Figure 6A and B).

Figure 6.

Helicobacter pylori infection induces PLK1-mediated activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway in a time-dependent manner. Cultures of MKN-28 cells were incubated at different time points with H. pylori infection (MOI = 200). Immunoblotting was used to quantify the expression levels of PLK1 (A) and Akt pathway-related proteins (B). The data are representative of three independent experiments. The samples were derived from the same experiment and the blots were processed in parallel. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Abbreviations: MOI, multiplicity of infection; PLK1, polo-like kinase 1.

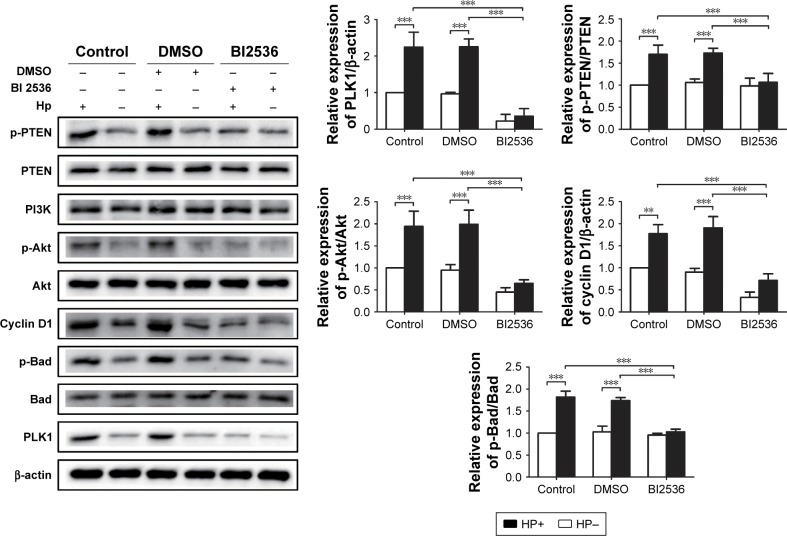

To certify whether H. pylori-induced activation of Akt pathway is dependent on PLK1, we used the PLK1 inhibitor BI 2536 to pretreat MKN-28 cells prior to H. pylori infection. We found that after H. pylori infection, expression levels of PLK1, p-PTEN, p-Akt, cyclin D1, and p-Bad were significantly decreased in the BI-2536-treated group compared to the DMSO and the untreated group (p<0.05) (Figure 7), suggesting that PLK1 is involved in H. pylori infection-induced activation of the Akt pathway.

Figure 7.

PLK1 inhibition blocks Helicobacter pylori-induced activation of the Akt pathway. Immunoblotting was used to quantify the expression levels of PLK1 and Akt pathway-related proteins in MKN-28 cells incubated with H. pylori for 24 h and treated with BI 2536 (200 nM pretreatment before incubation with H. pylori). The data are representative of three independent experiments. The samples were derived from the same experiment and the blots were processed in parallel. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Abbreviation: PLK1, polo-like kinase 1.

Discussion

Development of gastric cancer is a multistaged and orderly process, which proceeds from normal mucosa to chronic non-atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and finally gastric cancer. H. pylori infection often plays the initial and leading role in this process. We previously reported that increased PTEN phosphorylation at residues Ser380/Thr382/383 contributed to H. pylori infection-induced gastric carcinogenesis.19 PLK1 could promote PTEN phosphorylation at these residues.22 Therefore, the present study focused on the unknown role of PLK1 in H. pylori-regulated cancer occurrence and development.

Normally, PLK1 is expressed highly in tissues with an actively proliferating cell population, and PLK1 is expressed poorly in gastric tissues. Jang et al23 detected the expression of PLK1 in 280 patients with gastric cancer and found that 95% of cancer patients had high expression of PLK1, while there was almost no expression of PLK1 in its paired adjacent mucosa, which is consistent with our findings. A sustained increase of PLK1 in intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and gastric cancer tissues could be detected in our study. Additionally, the data showed that PLK1 was significantly lower in patients with chronic non-atrophic gastritis who were infected with H. pylori, but there was no significant difference among patients at later stages, suggesting that PLK1 related to H. pylori may contribute to gastric carcinogenesis at the early stage. To confirm the human sample results, we established H. pylori-infected Mongolian gerbil models to further demonstrate the role of PLK1 in H. pylori-induced cancer occurrence. We found that PLK1 expression was positively related with the duration of H. pylori infection, which supported our human sample results.

According to numerous studies and our preliminary experiments, PTEN can negatively regulate the PI3K/Akt pathway, and the latter is important in promoting proliferation, controlling cell survival, and inhibiting apoptosis.24–27 Our present study revealed that H. pylori infection could increase expression of PLK1, thus inducing PTEN phosphorylation and then the activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway. Meanwhile, expression of p-PTEN, p-Akt, cyclin D1, and p-Bad began to increase 30 min after H. pylori infection and continued throughout the duration of the infection. The control group, which was not exposed to infection, exhibited no significant changes in the expression of p-PTEN, p-Akt, cyclin D1, and p-Bad. This suggests that H. pylori may activate the PTEN/Akt signaling pathway at the early stage of infection in vitro. Furthermore, a broad range of studies confirmed that H. pylori infection could activate the Akt signaling pathway at the early stage.19,28,29 We, therefore, hypothesized that at the early stage of infection, H. pylori can increase PLK1 by activation of the Akt signaling pathway. We believe this process underlies the disordered proliferation of gastric mucosal cells, which ultimately contributes to gastric carcinogenesis and increased risk of tumor proliferation.

Is PLK1 really involved in H. pylori-promoted cancer cell proliferation? To answer this question, we added the PLK1 inhibitor BI 2536. We pretreated MKN-28 cells with BI 2536 and DMSO and then co-cultured them with H. pylori at an MOI of 200:1. The growth rate of MKN-28 cells significantly decreased in the BI 2536-pretreated group, suggesting that H. pylori infection induces cell survival in vitro and that PLK1 is involved in the regulation. Additionally, we observed that the expression levels of p-PTEN, p-Akt, cyclin D1, and p-Bad in the BI 2536-pretreated group were significantly downregulated. Inhibition of PLK1 blocked the activation of the PTEN/Akt pathway, demonstrating that activation of the Akt pathway by H. pylori is dependent on PLK1.

Although our results contribute to a deeper understanding of H. pylori infection-related gastric carcinogenesis, there are some limitations in the present study. The study focused only on a CagA+ and VagA+ strain of H. pylori, actually in addition to CagA+ and VagA+, H. pylori also secretes many other virulence factors, including iceA, oipA, urease, babA2, Lewis b, hrgA, dupA, picA, picB, and so on. These virulence factors encode genetic polymorphism of their proteins which can cause different pathogenicity of H. pylori and then determine the clinical outcome of H. pylori infection-related diseases. However, the virulence factors responsible for PLK1/Akt interactions and related cancer prognosis are still not clear.

Conclusion

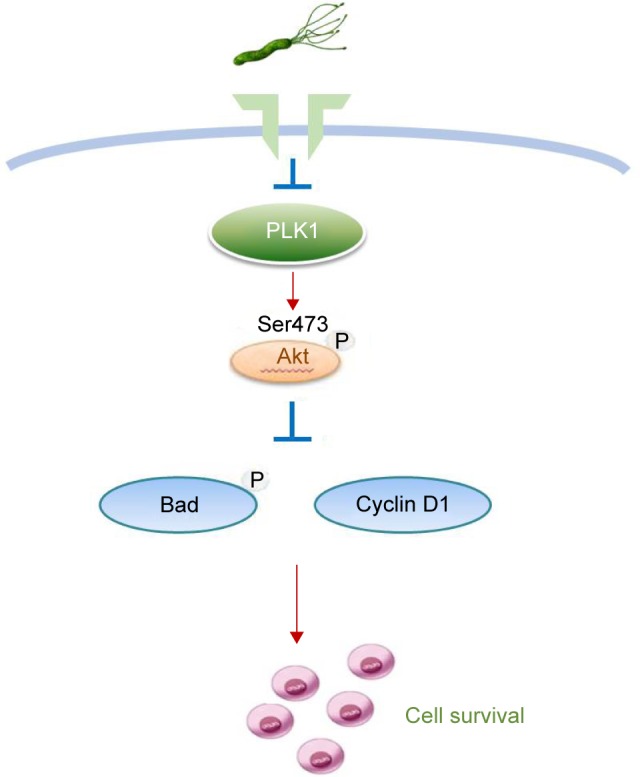

We confirmed the role of PLK1/p-PTEN/PI3K/Akt in H. pylori-induced carcinogenesis (detail in Figure 8). The elucidation of this mechanism may aid the development of new control strategies for H. pylori infection-related disease.

Figure 8.

A schematic model of GC development. Helicobacter pylori promotes gastric epithelial cell survival through the PLK1/PI3K/Akt pathway.

Abbreviation: GC, gastric cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81460377, 81270479, 81470832, and 81670507), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province, China (20151BAB205041), the Graduate Student Innovation Foundation of Jiangxi Province, China (YC2015-B021), the Jiangxi Province Talent 555 Project, and the National Science and Technology Major Projects program for “Major New Drugs Innovation and Development” of China (2011ZX09302-007-03). We thank Prof JZ Zhang at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases and Prevention of Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for providing the H. pylori type strain ATCC43504.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu W, Yang Z, Lu N. Molecular targeted therapy for the treatment of gastric cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:1. doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0276-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith MR, Wilson ML, Hamanaka R, et al. Malignant transformation of mammalian cells initiated by constitutive expression of the polo-like kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234(2):397–405. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao CL, Ju JY, Gao W, Yu WJ, Gao ZQ, Li WT. Downregulation of PLK1 by RNAi attenuates the tumorigenicity of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells via promoting apoptosis and inhibiting angiogenesis. Neoplasma. 2015;62(5):748–755. doi: 10.4149/neo_2015_089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai XP, Chen LD, Song HB, Zhang CX, Yuan ZW, Xiang ZX. PLK1 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of gastric carcinoma cells. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8(10):4172–4183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han DP, Zhu QL, Cui JT, et al. Polo-like kinase 1 is overexpressed in colorectal cancer and participates in the migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(6):BR237–BR246. doi: 10.12659/MSM.882900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun W, Su Q, Cao X, et al. High expression of polo-like kinase 1 is associated with early development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Genomics. 2014;2014:312130. doi: 10.1155/2014/312130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thrum S, Lorenz J, Mossner J, Wiedmann M. Polo-like kinase 1 inhibition as a new therapeutic modality in therapy of cholangiocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(10):3289–3299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahajan UM, Teller S, Sendler M, et al. Tumour-specific delivery of siRNA-coupled superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, targeted against PLK1, stops progression of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2016;65(11):1838–1849. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu L, Xing S, Zhang L, Yu JM, Lin C, Yang WJ. Involvement of Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) in quiescence regulation of cancer stem-like cells of the gastric cancer cell lines. Oncotarget. 2017;8(23):37633–37645. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otsu H, Iimori M, Ando K, et al. Gastric cancer patients with high PLK1 expression and DNA aneuploidy correlate with poor prognosis. Oncology. 2016;91(1):31–40. doi: 10.1159/000445952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kao CY, Sheu BS, Wu JJ. Helicobacter pylori infection: an overview of bacterial virulence factors and pathogenesis. Biomed J. 2016;39(1):14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Biological agents. Volume 100 B. A review of human carcinogens. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100(Pt B):1–441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Some industrial chemicals. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Humans. 1994;60:1–560. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plummer M, de Martel C, Vignat J, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: a synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(9):e609–e616. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, et al. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64(9):1353–1367. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito K, Yamaoka Y, Yoffe B, Graham DY. Disturbance of apoptosis and DNA synthesis by Helicobacter pylori infection of hepatocytes. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(9):2532–2540. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0163-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Z, Xie C, Xu W, et al. Phosphorylation and inactivation of PTEN at residues Ser380/Thr382/383 induced by Helicobacter pylori promotes gastric epithelial cell survival through PI3K/Akt pathway. Oncotarget. 2015;6(31):31916–31926. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z, Li J, Bi P, et al. Plk1 phosphorylation of PTEN causes a tumor-promoting metabolic state. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(19):3642–3661. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00814-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Z, Yuan XG, Chen J, Luo SW, Luo ZJ, Lu NH. Reduced expression of PTEN and increased PTEN phosphorylation at residue Ser380 in gastric cancer tissues: a novel mechanism of PTEN inactivation. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37(1):72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi BH, Pagano M, Dai W. Plk1 protein phosphorylates phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and regulates its mitotic activity during the cell cycle. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(20):14066–14074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.558155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jang YJ, Kim YS, Kim WH. Oncogenic effect of Polo-like kinase 1 expression in human gastric carcinomas. Int J Oncol. 2006;29(3):589–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stambolic V, Suzuki A, de la Pompa JL, et al. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell. 1998;95(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun H, Lesche R, Li DM, et al. PTEN modulates cell cycle progression and cell survival by regulating phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5,-trisphosphate and Akt/protein kinase B signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(11):6199–6204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi DM, Bian XY, Qin CD, Wu WZ. miR-106b-5p promotes stem cell-like properties of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by targeting PTEN via PI3K/Akt pathway. OncoTargets Ther. 2018;11:571–585. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S152611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tapia O, Riquelme I, Leal P, et al. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is activated in gastric cancer with potential prognostic and predictive significance. Virchows Archiv. 2014;465(1):25–33. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shu X, Yang Z, Li ZH, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection activates the Akt-Mdm2-p53 signaling pathway in gastric epithelial cells. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(4):876–886. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei J, Nagy TA, Vilgelm A, et al. Regulation of p53 tumor suppressor by Helicobacter pylori in gastric epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(4):1333–1343. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]