Abstract

While the molecular events involved in cell responses to heat stress have been extensively studied, our understanding of the genetic basis of basal thermotolerance, and particularly its evolution within the green lineage, remains limited. Here, we present the 13.3-Mb haploid genome and transcriptomes of a halotolerant and thermotolerant unicellular green alga, Picochlorum costavermella (Trebouxiophyceae) to investigate the evolution of the genomic basis of thermotolerance. Differential gene expression at high and standard temperatures revealed that more of the gene families containing up-regulated genes at high temperature were recently evolved, and less originated at the ancestor of green plants. Inversely, there was an excess of ancient gene families containing transcriptionally repressed genes. Interestingly, there is a striking overlap between the thermotolerance and halotolerance transcriptional rewiring, as more than one-third of the gene families up-regulated at 35 °C were also up-regulated under variable salt concentrations in Picochlorum SE3. Moreover, phylogenetic analysis of the 9,304 protein coding genes revealed 26 genes of horizontally transferred origin in P. costavermella, of which five were differentially expressed at higher temperature. Altogether, these results provide new insights about how the genomic basis of adaptation to halo- and thermotolerance evolved in the green lineage.

Keywords: Trebouxiophyceae, gene family evolution, cotolerance, phylostratigraphy, horizontal gene transfer

Introduction

Chlorophyta, comprising a dozen Classes of green algae (Leliaert et al. 2012), and its closest sister phylum Streptophyta (land plants) evolved from a common ancestor 1.8 billion years ago (Sagan 1967; Yoon et al. 2004). While the classes Chlorophyceae and Ulvophyceae so far have received the most attention from taxonomists, the Trebouxiophyceae (Friedl 1995) is also very rich, with over 840 described species (Guiry and Guiry 2017). It includes morphologically very diverse green algae, such as flagellates, coccoid, or colonial multicellular algae (De Clerck et al. 2012) with different lifestyles, including parasitism (Aboal and Werner 2011; Pombert et al. 2014) and photosynthetic symbiosis (Blanc 2010). Among the Trebouxiophyceae, Picochlorum (Henley et al. 2004) constitutes a genus of marine and brackish water unicellular coccoid microalgae displaying broad halotolerance, with cultures supporting freshwater to hypersaline media changes (Henley et al. 2002; Foflonker et al. 2015, 2016). Their high lipid and protein content, and ease of culture (Watanabe and Fujii 2016) fostered the use of several Picochlorum strains for biotechnological applications in aquaculture (Chen et al. 2012), health (Becker 2007; de la Vega et al. 2011), and biofuel production (de la Vega et al. 2011; Park et al. 2012; Zhu and Dunford 2013; Tran et al. 2014). Additionally, P. eukaryotum could be maintained in culture with cultivated retinal human cells (Black et al. 2014), potentially expanding the functionality of the human cells, opening novel medical applications.

In an attempt to further increase the knowledge about the diversity of marine green algae, we have isolated a Picochlorum strain from the estuary of a river flowing into the Mediterranean Sea. This strain grew not only on a wide spectrum of salinity concentrations but also grew at 35 °C, an unreported temperature in its natural aquatic environment, consistent with earlier observations of cell division at temperatures up to 40 °C in other Picochlorum strains (de la Vega et al. 2011). The acclimation to temperature variation, thermotolerance (Bokszczanin and Fragkostefanakis 2013), was an essential adaption in the first green algae conquesting the coastal terrestrial habitat (Vries and Archibald 2018) and is presently crucial for sustained crop production because of global warming (Li and Cui 2014). While the molecular events involved in plant cell responses to heat stress have been extensively studied (Lindquist 1986; Vierling 1991; Queitsch et al. 2000; Kotak et al. 2007; Mishkind et al. 2009; Mittler et al. 2012; Guo et al. 2016), our understanding of the genetic basis of basal thermotolerance, and particularly its evolution within the green lineage, remains limited. Where acquired thermotolerance is induced by a short acclimation period at moderately high but survivable temperatures, basal tolerance refers to the inherent ability of an organism to survive exposure to temperatures above the optimal for growth in the absence of an acclimation period.

Here, we take advantage of the complete genome sequence of a novel species, P. costavermella, available genome data in two related Picochlorum species (Foflonker et al. 2015; Gonzalez-Esquer et al. 2018) and 17 sequenced Viridiplantae species, to investigate the evolutionary history of gene families involved in thermotolerance in the green lineage. Based on detailed transcript profiling experiments, we analyze the phylostratigraphy of genes which are differentially expressed at 20 and 35 °C and study the overlap in transcriptional responses required for thermotolerance and halotolerance.

Materials and Methods

Strain Isolation and Environmental Metabarcoding

Picochlorum costavermella (strain RCC4223) was isolated from the estuary of the coastal river “La Massane” (42°32′36 N, 3°03′09 E, June 2011, NW Mediterranean Sea, France). A water sample was plated in agarose (0.15%) enriched with L1 medium (Guillard and Hargraves 1993). One colony was isolated, cloned, and kept in L1 seawater medium flasks by repeated subculturing. Its karyotype was obtained by pulse field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (Yamamoto et al. 2001). To investigate its habitat range, we searched for 18S rDNA signatures in 42 metagenomes of seawater sampled between 2012 and 2013 from nearby marine sites (13 samples from SOLA, 42° 29′ 20.4″N, 3° 8′ 42″E; 7 samples from MOLA, 42° 27′ 10.8″N, 3° 32′ 34.8″E) and from the Leucate lagoon (22 samples, 42° 48′ 18″ N, 3° 1′ 15.6″E) (Lebredonchel 2016). Two hyper-variable regions of the 18S rDNA sequence were amplified using degenerate primers: V4 (380 bp, using the CCAGCASCYGCGGTAATTCC forward and ACTTTCGTTCTTGATYRA reverse primers) and V9 (94 bp, using the TTGTACACACCGCCC forward and CCTTCYGCAGGTTCACCTAC reverse primers). Sequencing was performed by Illumina MiSeq (GATC biotech, Konstanz, Germany) and analyzed using the Mothur pipeline (Schloss et al. 2009; Kozich et al. 2013).

Sequencing and Genome Assembly

DNA was extracted using a modified CTAB protocol (Winnepenninckx et al. 1993) from 50 ml cultures with 107 cells per ml. The whole genome was sequenced with the SMRT Technology PacBio RS II by GATC biotech (Konstanz, Germany) and assembled by GATC biotech (Konstanz, Germany) with InView De novo Genome 2.0. HGAP (Chin et al. 2013). A complementary sequencing data set was obtained by Illumina MiSeq technology (300 bp paired-end reads) at GATC biotech (Konstanz, Germany), and assembled with ABySS (Simpson et al. 2009). The final version of the genome was obtained by merging both ABySS and HGAP assemblies to build scaffolds with three assembly programs: SSPACE (Boetzer et al. 2011), SGA (Simpson and Durbin 2012), and Geneious (Kearse et al. 2012). Bacterial contigs were identified using BLASTn against Genbank and discarded from downstream analysis.

Genome Annotation

Total RNA was extracted from pooling 8 total flasks of 15 ml cultures taken every 3 h, in L1 medium at 20 °C under 8 h light–16 h dark cycles. mRNAs were purified using the Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo Research). Libraries and sequencing were performed using Illumina HiSeq technology by GATC biotech (Konstanz, Germany). Gene prediction was performed using the preinformed gene-caller software Eugene (Foissac et al. 2003). To inform the prediction process, extrinsic data were used: protein data sets from other available algae (Coccomyxa, P.SE3, Mamiellales), and RNAseq reads (200 bp paired-end) as preassembled contigs and as junctions from individual reads. 1,705 out of the 9,304 predicted genes were further corrected by expert annotators using the online resource for community annotation ORCAE (Sterck et al. 2012).

When organellar genomes were inspected both appeared to have a direct repeat around the sequencing break point, which were supported by only half read coverage compared with the rest of the sequence. Thus, these repeats have been manually deleted from the original assembly (8 kb in mtDNA, 4 kb in ptDNA). Organelles were first annotated using GeSeq (Tillich et al. 2017) with following criteria: for BLAT protein searches, require identity of 25, and for rRNA, tRNA, DNA BLAT searches, 85, while allowing short matches. In addition, de novo tRNA search was performed using tRNAscan-SE v1.2.1 with mitochondrial/chloroplast tRNAs (max length for introns 3,000 bp, threshold 15). Infernal (Nawrocki 2014) was used to predict rRNA. To annotate the chloroplast, MPI-MP chloroplast references (CDS + rRNA) where used and an additional HMMER profile search (CDS + rRNA) was ran. To annotate the mitochondrion, the CDS sequences from Chlorellales mitochondrial genomes present in NCBI RefSeq were used as a reference (Auxenochlorella protothecoides NC_026009.1, Chlorella sorokiniana NC_024626.1, Chlorella variabilis NC64A NC_025413.1, Helicosporidium sp. ex Simulium jonesi ATCC 50920 NC_017841.1, Lobosphaera protothecoides NC_027060.1, Prototheca wickerhamii NC_001613.1). Last, manual curation was performed to adjust gene model borders by examining protein-coding genes by BLASTx searches against the NCBI nonredundant protein (nr) database. If necessary, frameshifts were manually corrected (4 frameshifts in 1 gene in the cpDNA and 11 frameshifts in 3 genes in the mtDNA). The organelles were visualized using OGDRAW v1.2 (Lohse et al. 2007). Circos (Krzywinski et al. 2009) was used to generate GC plots.

Analysis of Genome Completeness

The completeness of the produced gene space was estimated by assessing the representation of Chlorophyta core gene families, retrieved from the pico-PLAZA database (Vandepoele et al. 2013). Core gene families correspond to a set of gene families that are highly conserved in a majority of species (at least 90%) within defined evolutionary lineages and here, a set of 2,410 Chlorophyta core gene families was defined. Each pico-PLAZA gene family was then given a weight as described by Van Bel and coworkers (Van Bel et al. 2012).

The Chlorophyta core gene family completeness analysis was performed as follows: i) a protein similarity search of the predicted proteins against the pico-PLAZA proteome (i.e., protein sequences from all species of the database) using RapSearch2 (Zhao et al. 2012) with an e-value cut-off of 10−5; ii) for each query, association of the ten top hits to their gene family followed by scoring and selection of the best gene family; iii) report of the number of represented and missing Chlorophyta core genes families; and iv) calculation of a completeness score (sum of the weights of represented Chlorophyta core gene families on total weight of Chlorophyta core gene families). In order to compare the results obtained for P. costavermella, the same analysis was also performed for 15 other Chlorophyta (see species list supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online).

Analysis of Gene Family Gain and Loss

All predicted genes were loaded into a custom instance of pico-PLAZA (Vandepoele et al. 2013) containing 38 eukaryotic species (including Metazoa, Fungi, Chlorophyta, Embryophyta, Rhodophyta, Haptobionta, and Stramenopiles, see supplementary table S8, Supplementary Material online) to assign genes to gene families. For species denoted with asterisk in supplementary table S8, Supplementary Material online, functional annotations (GO annotations and InterPro domains) were retrieved using the Uniprot Gene Association File (downloaded September 10, 2015). For all other species InterPro was run (January 2016) and mapped to GO terms. Following an “all-versus-all” BLASTP (Altschul et al. 1990) (version 2.2.27+, e-value threshold 10−5, max hits 500) protein sequence similarity search, both TribeMCL (Enright et al. 2002) (version 10-201) and OrthoMCL (Li et al. 2003) (version 2.0, mcl inflation factor 3.0) were used to delineate gene families and subfamilies, respectively. Collinear regions (regions with conserved gene content and order) were computed using i-ADHoRe 3.0 (Proost et al. 2012) (alignment method: gg2, gap size 30, tandem gap 30, cluster gap 35, q value 0.85, probability cut-off 0.01, anchor_points 3, level_2_only FALSE, FDR as method for multiple hypothesis correction).

To further study gene family expansion in Chlorellales, gene family sizes were calculated for all TribeMCL gene families (excluding orphans). The number of genes per species for each family was transformed into a matrix of z-scores in order to center and normalize the data (Martens et al. 2008). After filtering for transposases, gene families were sorted based on variance and the 100 most varying gene families were used in hierarchical clustering with a Euclidean distance function (heatmap.2 function in R-package gplots).

The phylogenetic profile of TribeMCL gene families (excluding orphans, these are gene families having only one copy in one species) and the inferred species tree topology (see section “Phylogenetic analysis”) were provided to reconstruct the most parsimonious gain and loss scenario for every gene family using the Dollop program from the PHYLIP package (version 3.69) (Felsenstein 2005). This allows the set of gene families at every (ancestral) node of the phylogenetic tree to be determined. Gene family losses and gains were further analyzed by performing Gene Ontology (GO) and InterPro domain term analysis (P value ≤ 0.05, minimum hits 2). Multiple hypothesis testing was constrained using the Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple hypotheses testing (q value < 0.05). As the number of ancient gene family gain and losses is affected by the choice of species included in the analysis, we checked that our conclusions are robust to the inclusion of P.soloecismus (Gonzalez-Esquer et al. 2018) and the charophyte Klebsormidium flaccidum (Hori et al. 2014) (supplementary fig. S40, Supplementary Material online).

Identification of Horizontal Gene Transfer Candidates

The nonredundant protein database was downloaded from NCBI (date June 30, 2017). Protein sequences from P. costavermella were used as query to search against this database using DIAMOND (Buchfink et al. 2015) in sensitive mode (e-value cut-off =1e−05), retaining up to 1,000 hits. Hit sequences per query gene were then retrieved from the queried database with no more than five sequences for each order, 15 sequences per phylum, requiring a percent alignment length of > 50% and percentage identity of >27.5%. Query proteins having a bacterial hit in their top 20 hits were subjected to further examination. Orthologous sequences for every remaining query gene were determined in Picochlorum SE3 using the custom pico-PLAZA instance, requiring at least two methods within the integrative orthologous gene detection to confirm this orthologous relationship (Integrative Orthology viewer) (Van Bel et al. 2012). The resulting sequences were aligned using MUSCLE version 3.8.31 (Edgar 2004) under default settings. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using IQtree version 1.5.5 (Nguyen et al. 2015) under the best amino acid substitution model selected by the build-in model-selection function (ModelFinder) (Kalyaanamoorthy et al. 2017) using the following set as potential models: JTT, LG, WAG, Blosum62, VT, and Dayhoff. Empirical AA frequencies were calculated from the data and the FreeRate model (Yang 1995) was used to account for rate-heterogeneity across sites. Branch supports were estimated using ultrafast bootstrap (UFboot) approximation approach (Minh et al. 2013) with 1,000 bootstrap replicates (-bb 1000).The resulting phylogenetic trees were sorted using PhySortR (Stephens et al. 2016) to detect nonexclusive bacterial clades. Trees containing >20 genes were using following parameters: sortTrees(“Bacteria,” min.support = 95, clade.exclusivity = 0.9, min.prop.target = 0.7). Trees containing <20 genes on the other hand, required only a 0.66 threshold for clade.exclusivity and min.prop.target. Finally, a manual inspection was performed to identify sequences of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) origin among the sorted trees, which required an UFboot support value ≥ 95%. The detected HGT events were compared with those previously identified in Picochlorum SE3 (Foflonker et al. 2015).

Phylogenetic Analysis

Single gene families from TribeMCL (Enright et al. 2002) were defined as highly conserved families if they were present in all 18 species (P. costavermella, Picochlorum SE3, 3 land plants, 6 Mamiellophyceae, 2 Chlorophyceae, and 5 Trebouxiophyceae). For each of the 66 identified single-copy conserved families, protein sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (version 3.8.31) (Edgar 2004), and all alignments were concatenated per species. This unedited alignment (34,547 amino acid positions) was used to construct a phylogenetic tree using RaxML (Stamatakis 2014) (version 8.2.8) (model PROTGAMMAWAG, 100 bootstraps).

Since the 18S rDNA gene is a widely used molecular barcode for taxonomic affiliation in phytoplankton (Piganeau et al. 2011), we investigated the molecular phylogeny of this gene within the Picochlorum clade. The analysis involved 21 nucleotide sequences, from GenBank or from manual annotation of the complete genome sequence (Gonzalez-Esquer et al. 2018), when available. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 1,634 positions in the final data set. Maximum Likelihood (ML) methods were conducted based on the Tamura-Nei model (Tamura and Nei 1993) and Bayesian method was conducted based on the GTR model (Tavaré 1986). A discrete Gamma distribution and a proportion of invariable sites were used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites. The tree was drawn to scale, with branch lengths proportional to the number of substitutions per site. Maximum Likelihood analysis was conducted in MEGA7 (Kumar et al. 2016) and Bayesian analysis in MrBayes (Ronquist et al. 2012).

Salinity and Temperature Tolerance Assays

Halotolerance was tested using a salinity gradient of 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 g l−1 (i.e., 0.17–1.20 M). The different salinities were obtained from filtered (0.2 µm) and sterile marine water (35 g l−1). Sterile sea salt was added to the marine water to reach the salinities >35 g l −1. The lower salinity media were obtained by adjustment of sea water and distilled water. To each medium, we added the standard L1 medium nutrients, including trace elements and vitamins (Guillard and Hargraves 1993), thereby increasing the overall salinity of each of the media by 0.11 g l −1. Algae were grown in 48-well plates inoculated with 5,000 cells ml −1 in exponential phase, with three replicates per condition and five controls in standard L1 medium with a 12:12 h light-dark cycle. In all conditions, cell concentrations were determined by flow cytometry (FACS Canto, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). After 7 days, growth rates were determined with the following equation:

| (1) |

d is the number of cell divisions per day, N0 and Nt the initial and final cell concentration, and t is the time in days.

For comparison, another marine green alga isolated in the same area (Gulf of Lion), Ostreococcus tauri RCC4221 (Blanc-Mathieu et al. 2014) was exposed to the same experimental conditions as P. costavermella.

Growth rates were estimated at two temperatures (20 and 35 °C) in standard L1 medium. No culture survived at 40 °C (results not shown). To remove variation in gene expression due to the circadian cycle, cultures were grown under constant light and sampled at the same time. Three cultures, serving as biological replicates, were started from 106 cells at 20 °C and sampled at 20 and 35 °C after 7 days. RNA was extracted with the Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo Research), libraries and sequencing were performed using Illumina HiSeq 2000 (125 bp paired-end) GATC biotech (Konstanz, Germany).

Statistical Analysis of Differential Gene Expression and Phylostratum Information

RNA reads were aligned on the reference genome using STAR version 2.02.01 (Dobin et al. 2013) with default parameters (∼13 million paired-end reads of 250 bp per sample, 93% of reads mapped).

The number of reads aligned to each gene was determined by HTSeq (Anders et al. 2015) using standard options and the differential gene expression analysis was performed with the DEseq2 package (Love et al. 2014, 2). A P value of ≤ 0.01 and a log2-fold change of 1 were defined as cut-offs for calling differentially expressed genes. These differentially expressed genes were investigated further by performing GO and gene family enrichment analysis (P value ≤ 0.05, gene family enrichment minimum two hits). Multiple hypothesis testing was constrained using the Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple hypotheses testing (q value < 0.05).

All differentially expressed genes were divided according to their phylostratum based on the DOLLO analysis and compared with the phylostratum distribution of all genes in the genome. Statistical significance was determined by randomly sampling 10,000 times the number of differentially expressed genes from all genes and counting how many times the overlap between all genes in a phylostratum and the sampled genes was higher than the observed fraction.

To compare this trend across the green lineage, phylostratum distribution was assessed in heat shock experiments performed in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Arabidopsis thaliana. All probe sequences from the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii 10 K v1.0 (GPL10173) were downloaded and those who were differentially expressed according to (Voss et al. 2011) were mapped against the Chlamydomonas transcript sequences to assign to the latest genome annotation (annotation version v5.5). Differentially expressed genes identified in (Matsuura et al. 2010; Nguyen et al. 2015) were subjected to phylostratum analysis based on PLAZA 3.0 dicots (Proost et al. 2015). Significance testing was performed as described earlier.

The proportion of each estimated amino-acid frequency between the two temperature conditions was compared with a Student’s t-test. The distribution of the amino acid content of each culture was estimated by weighting the number of amino acids in a gene by its RNA-Seq coverage, and normalizing by the total number of reads.

Data Availability

The genome data and annotation have been submitted to Genbank under accession number PRJNA389600. The complete sequences of the P. costavermella plastid and mitochondrial genomes have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers ERS2253286 (chloroplast) and ERS2253287 (mitochondrion). The Miseq raw data have been submitted to the SRA archive under accession numbers SAMN07739529:30. The RNAseq data have been submitted to SRA archive under accession numbers SAMN07739531:44.

Results

Picochlorum costavermella sp. nov. Hemon, and Grimsley (Trebouxiophyceae)

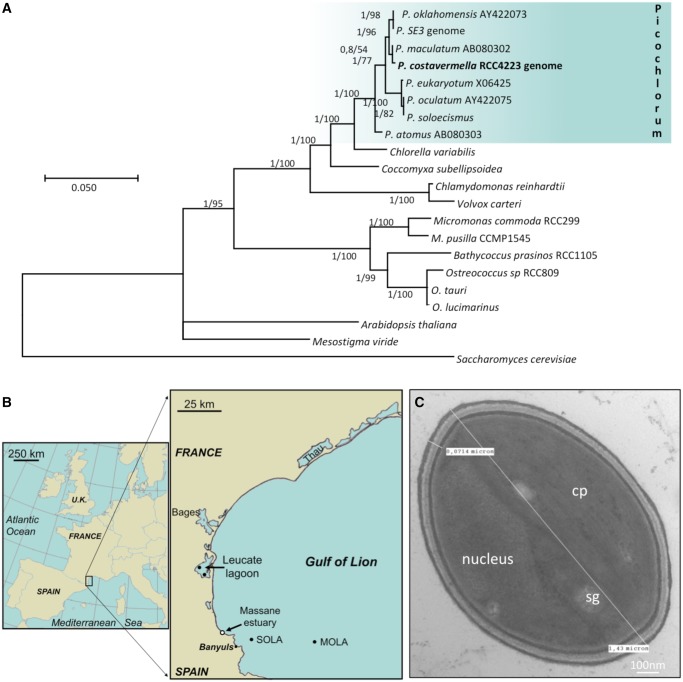

The taxonomy of unicellular coccoid green alga has been a complicated and heavily discussed issue, as a consequence of debates about discriminating morphological or physiological characters (Henley et al. 2004). Identification of this strain was based on molecular studies of the complete 1,791 bp 18S rDNA sequence, which is unique, and is closest to P. maculatum (AB080302), isolated from the East Atlantic (Yamamoto et al. 2003). The four previously described Picochlorum (Henley et al. 2004); P. atomus, P. eukaryotum, P. oculatum, and P. oklahomensis, are more distantly related, while there are five nucleotide differences with the 18S rDNA gene in the genome of strain P. SE3 (fig. 1A). The sequences of the hypervariable V4 and V9 regions of this strain were found in four sites, which were sampled over a year in the vicinity of the initial isolation site (fig. 1B). These sequences were slightly more prevalent in the Leucate lagoon (19/22 metagenomes) than in marine coastal sites (11/20). None of the additional 18S rDNA available from GenBank are identical to the sequence of this strain (e.g., there are two differences with AJ131691; PicochlorumRCC011, isolated from the equatorial Pacific ocean). The V4 region is unique compared with the other described Picochlorum species, while the V9 region is identical to P. maculatum. Therefore, the detection of the V4 sequence of this strain in the environmental sequencing data indicates the presence of closely related strains in nearby lagoonar and sea marine environments. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) pictures revealed nonflagellate small ovoid cells 1–2 μm long and 1 µm wide, with a ∼70-nm thick trilaminar cell wall (fig. 1C), one single chloroplast and one single mitochondrion.

Fig. 1.—

Molecular characterization and cell features. (A) Phylogenetic tree of 18SrDNA alignment (1,634 sites) resulting from ML analysis with the highest log likelihood. Both posterior probabilities (PP) and bootstrap (BP) values are indicated next to each node as follows: PP/BP. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths proportional to the number of substitutions per site. (B) Geographical location of all sampling sites: unfilled circle (Massane estuary) denotes the isolation site, while black circles represent environmental sampling sites. (C) Picochlorum costavermella transmission electron micrograph. The nucleus, the chloroplast (cp) with two starch granules (sg) can be easily identified. Note the 71-nm thick cell wall. Cell length 1–2 µm.

Diagnosis

The morphological features we observed for this strain are shared with all previously described Picochlorum species (Henley et al. 2004), and the evidence for a yet unreported novel Picochlorum species is provided by the unique molecular signatures of its complete 18SrDNA sequence. A culture of this strain (accession RCC4223) is available from the Roscoff culture collection (Vaulot et al. 2004). We propose to name this novel species in reference to its sampling origin, Picochlorum costavermella ([lat.] meaning “Côte Vermeille” in French and “Vermillion Coast” in English). Previously described Picochlorum species have been isolated from 1) a seawater aquarium in Germany (P. eukaryotum), 2) a marine fish tank in Cyprus, NE Mediterranean sea (P. atomus), 3) the York river estuary NW Atlantic (P. oculatum), 4) the coast of the Isle of Wight, NE Atlantic, United Kingdom (P. maculatum—CCAP 251/3), and 5) an ephemeral pond in north-western Oklahoma (P. oklahomense) (Henley et al. 2004). Picochlorumcostavermella is thus the first described Picochlorum from the NW Mediterranean sea.

Phenotypic assays revealed that P. costavermella was able to grow in all salinities tested, from 10 to 70 g l −1 of NaCl added to a medium with basal salts (see Materials and Methods), with an optimal growth rate at 20 g l −1 (0.34 M) NaCl (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). Temperature assays (at standard salinity of 35 g l −1) showed that P. costavermella could grow at temperatures up to 35 °C (G = 1.19 cell divisions per day at 35 °C, G = 1.25 cell divisions per day at 20 °C), in contrast to cultures of Ostreococcus tauri, which were isolated from the same sampling sites (Grimsley et al. 2010) (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online).

Genome Sequencing, Gene Annotation, and Phylogenetic Analysis

PacBio sequencing of P. costavermella generated 266,217 reads, with an average length of 6,215 bp, corresponding to 70× genome coverage. The resulting HGAP assembly contained 361 contigs (21.3 Mb, N50 = 244 kb, complete genome statistics are provided in supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). Illumina MiSeq sequencing generated 2.3×106 300 bp paired-end reads and its assembly with ABySS resulted in 19,896 contigs (41.62 Mb, N50 = 11 kb, supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). HGAP and ABySS assemblies were used to generate the final assembly with Geneious (Kearse et al. 2012), which contained 31 scaffolds after filtering out bacterial contigs (N50 = 764 kb, 46.5% GC), corresponding to a total genome size of 13.3 Mb (table 1). These values are similar to those obtained for Picochlorum SE3 (Foflonker et al. 2015) (13.3 Mb, 46.1% GC content). Pulsed field gel electrophoresis of total DNA provided evidence for at least 10 distinct bands from ∼95 to ∼1,800 kb, adding up to a total size of ∼10 Mb (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online), consistent with several chromosomes of similar sizes that cannot be distinguished with this technique. While sizes of the largest scaffolds correspond to the PFGE predicted sizes (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online), none of the scaffolds contained TTTAGGG repeats, contrarily to what has been observed in most telomeric sequences across the green lineage (Fajkus et al. 2005). Because the repeat was also absent in all the intermediate assemblies and other available Picochlorum genomes, this may indicate an alternative system of telomere maintenance in Picochlorum, as previously suggested in plant species lacking this telomere repeat (Fajkus et al. 2005).

Table 1.

Genome Features of Picochlorum costavermella and Other Sequenced Green Alga

| P. costavermella RCC4223 | P. SE3 | P. soloecismus | Chlorella variabilis NC64A | Coccomyxa subellipsoidea | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Ostreococcus tauri RCC4221 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (Mb) | 13.33 | 13.28 | 15.36 | 46.16 | 49.19 | 112.53 | 12.57 |

| GC content (%) | 46.50 | 46.04 | 44.27 | 67.14 | 52.92 | 64.00 | 59.03 |

| Number of scaffolds | 31 | 1,266 | 40 | 414 | 47 | 90 | 22 |

| Largest scaffold (bp) | 1,794,128 | 564,282 | 1,551,012 | 3,119,887 | 4,035,500 | 9,982,135 | 1,076,297 |

| N50 (bp) | 764,180 | 126,215 | 724,710 | 1,469,606 | 1,959,569 | 6,617,689 | 739,027 |

| Protein coding genes | 9,304 | 7,367 | 6,869 | 9,791 | 9,629 | 17,741 | 7,668 |

| Average CDS length (bp) | 1,144 | 1,390 | 1,432 | 1,367 | 1,282 | 2,207 | 1,390 |

| Genes with introns (%) | 3,703 (40%) | 3,585 (49%) | 5,130 (74%) | 9,551 (98%) | 9,099 (95%) | 16,390 (92%) | 1,391 (18%) |

| Mean intron length (bp) | 88 | 101 | 133 | 208 | 285 | 270 | 139 |

| Mean intergenic length (bp) | 220 | 364 | 613 | 1,714 | 1,780 | 2,029 | 256 |

| Coding fraction (%) | 80% | 78% | 64% | 33% | 26% | 36% | 82% |

| Nuclear tRNAs | 42 | 24a | 75a | 43a | 91a | 260 | 47 |

| mtDNA (bp) | 34,178 | / | 38,672 | 78,500 | 65,497 | 15,758 | 44,237 |

| cpDNA (bp) | 74,290 | / | 72,741 | 124,579 | 175,731 | 203,828 | 71,666 |

| References | This study | (Foflonker et al. 2015) | (Gonzalez-Esquer et al. 2018) | (Blanc 2010) | (Foflonker et al. 2015) | (Merchant et al. 2007) | (Robbens et al. 2007; Blanc-Mathieu et al. 2014) |

Estimated from tRNAscanSE (Lowe and Eddy 1997) on available assembly.

Genome annotation revealed 9,304 protein coding genes (table 1), of which 94.5% have RNAseq coverage and 61 are part of putative transposable elements. All predicted protein-coding genes were compared against a set of evolutionary conserved Chlorophyta gene families (Veeckman et al. 2016) to estimate the completeness of the genome assembly. The results of the Chlorophyta core gene family completeness analysis (summarized in supplementary fig. S3, Supplementary Material online) suggest that P.costavermella’s gene repertoire is more complete than Picochlorum sp. SE3 (Chlorophyta core gene family completeness score of 0.94 and 0.91, respectively; 135 vs. 201 missing Chlorophyta core gene families, respectively). Inspection of missing core genes enabled us to correct mis-annotations; one gene (RCC4223.17g01452 encoding for a ubiquitin hydrolase) inside an intron of another gene (RCC4223.17g00730), or open reading frames predicted on the wrong strand. These manual annotations led to a decrease of missing gene families from 135 (94% completeness) to 99 (96% completeness) in the final genome version.

To examine the phylogenetic position of P. costavermella from its protein coding genes, we compared the sequences of 66 conserved single-copy genes of 18 species (P. costavermella, P. SE3, 3 land plants, 6 Mamiellophyceae, 2 Chlorophyceae, and 5 Trebouxiophyceae). The phylogenetic tree constructed based on this concatenated amino acid sequence alignment (34,547 amino acid positions) is consistent with the 18S rDNA phylogeny: it groups the two Picochlorum species together within the Trebouxiophyceae, as a sister clade to a clade containing the Chlorellales Auxenochlorella protothecoides, Helicosporidium sp., and Chlorella variabilis NC64 (supplementary fig. S4, Supplementary Material online).

Extreme Gene Compactness in Nuclear and Organellar Genomes

Complete chloroplast and mitochondria are both included in the assembly (supplementary table S4-S7 and figs. S5 and S6, Supplementary Material online). The absence and presence of all genes shared by at least two green algal plastid/mitochondrial genomes were examined, and proved the completeness of the newly annotated organelles in P. costavermella (supplementary tables S4–S7, Supplementary Material online). The complete chloroplast genome of P. costavermella (supplementary fig. S6, Supplementary Material online) is one of the smallest of all photosynthetic Trebouxiophyceae algae so far, AT-rich (68%), and circular with no inverted repeats or introns. Plastid genomes lacking an inverted repeat region have been reported in many Trebouxiophyceae (Yan et al. 2015). Although the genome is not as reduced as that seen in heterotrophic algae such as Prototheca wickerhamii (55 kb) and Helicosporidum sp. ATCC50920 (37 kb), the protein coding density is the highest among this algal class (supplementary fig. S7A, Supplementary Material online). This extreme gene compaction is also observed in the mitochondrion (34 kb, 41% GC), being the smallest mitochondrial genome with the highest protein coding density (supplementary fig. S7B, Supplementary Material online) to date within Trebouxiophyceae, while retaining all common functionalities.

Coding sequences make up 80% of the P. costavermella genome, having a mean intron length and a mean intergenic length of 80 and 220 bp, respectively (table 1), a range similar to other streamlined genomes such as the Mamiellophyceae Ostreococcus tauri (82%) and Bathycoccus prasinos (83%). Picochlorumcostavermella is the most gene dense genome sequenced so far belonging to the UTC algae (Ulvophyceae, Trebouxiophyceae, and Chlorophyceae), apart from the parasitic green alga Helicosporidium sp. (87%). Genomes in the Picochlorum genus display an ongoing genome reduction, with P. soloecismus being less compact than the closely related species P. SE3 and P. costavermella. However, genome reduction is slightly more severe in P. costavermella.

Gene Family Gain and Loss in Picochlorum

To study the evolution of gene families, we compiled genome information from 38 eukaryotic species: 8 Trebouxiophyceae (including P. costavermella and P. SE3), 2 Chlorophyceae, 6 Mamiellophyceae, 4 Embryophyta, 3 Rhodophyta, 7 Stramenopiles, 1 Alveolata, 1 Haptophyta, and 6 Ophisthokonta (supplementary table S8, Supplementary Material online). Sequence similarity and TribeMCL was used to delineate gene families grouping homologous genes. In total, 7,892 protein-coding genes of P. costavermella were assigned to 5,441 gene families, while 1,412 genes were assigned as orphans. A gene family refers to a group of two or more homologous genes, while an orphan is a single-copy species-specific gene lacking homologs in the set of compiled genomes. Supplementary table S9, Supplementary Material online, contains all gene identifiers of genes belonging to these gene families. Overall, 80% of the protein-coding genes had homologs in one or more other species. In addition, functional annotation was inferred using InterPro and known Gene Ontology (GO) terms in model species: 72% of the P. costavermella genes could be annotated with an InterPro domain and 53% with a GO term.

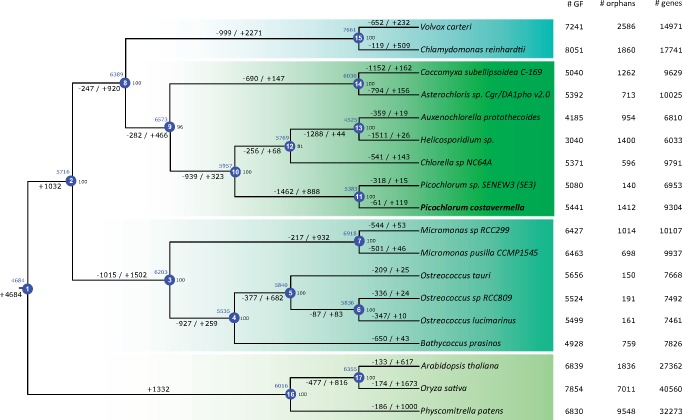

To detect all (ancestral) gene family gains and losses in Chlorophyta, a Dollo parsimony analysis was performed, which assumes that novel gene families can only arise once during evolution but can be lost independently multiple times. There was an excess of gene family losses over gains in the branch leading to the Picochlorum genus; with 1,462 gene families lost and 888 gained (fig. 2 and supplementary fig. S40, Supplementary Material online).

Fig. 2.—

Gene family evolution along the phylogenetic tree of Chlorophyta. Blue circles indicate internal nodes and bootstrap values are mentioned on the right of every node. Colored blocks refer, from top to bottom, to Chlorophyceae, Trebouxiophyceae, Mamiellophyceae and Streptophyta. Losses and gains are indicated along branches and blue numbers above the nodes refer to the ancestral gene family count. The number of gene families, orphans (single-copy gene families) and predicted genes are indicated next to each species. GF, gene family.

Gene families lost in Picochlorum were analyzed using their Interpro protein domains and Gene Ontology annotations. Enriched InterPro domains in lost gene families were the WD40 repeat, Glutathione S-transferase (C-terminal) and an ADP-ribosylation domain. The WD40 repeat is ∼40 amino acids long with tandem copies of tryptophan-aspartic acid, to form a type of circular solenoid protein involved in large panel of cell functions such as transcription, signal transduction, or apoptosis (Wang et al. 2015). GO terms enriched for these lost gene families (q value < 0.05), not containing a functionally corresponding Interpro domain, were carbohydrate metabolic process, cellular amino acid catabolic process, arabinose metabolic process, double-strand break repair via nonhomologous end joining, cellular response to DNA damage stimulus and DNA repair. Two examples are detailed below.

First, within the lost gene families involved in the carbohydrate metabolic process, the glyoxylate bypass has been lost in the Picochlorum genus, while being present in all of the other UTC algae compared (Ulvophyceae, Trebouxiophyceae, and Chlorophyceae). Both isocitrate lyase and malate synthase, specific to this pathway, and not shared with the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, have been lost. This pathway is typically localized in peroxisomes and used for generation of complex structural polysaccharides in absence of simple carbohydrates, for example, glucose, from lipids via acetate generated by fatty acid β-oxidation. This pathway allows the decarboxylation steps that take place in the TCA cycle to be bypassed, so that simple carbon compounds can be used for subsequent synthesis of macromolecules, including glucose. This pathway has also been lost independently in Metazoans (Kondrashov et al. 2006).

Second, within the cellular amino acid catabolic process, the Picochlorum genus misses three enzymes that degrade phenylalanine and tyrosine: homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase, maleylacetoacetate isomerase, and fumarylacetoacetase. These enzymes convert homogentisate into fumarate and acetoacetate. However, homogentisate might be converted into vitamin E by homogentisate phytyltransferase, an enzyme that is encoded in the Picochlorum genome.

Enriched InterPro domains in gained gene families in the Picochlorum genus were xylanase inhibitor (N-terminal), zinc finger (SWIM-type), PAN/Apple domain which is part of serine proteases, aspartic peptidase domain, sulfotransferase, FAS1 domain, fibronectin type III and pectin lyase fold. No significant GO enrichment was found for these genes. In addition to these gene family gains, 14 expanded gene families were identified in P. costavermella compared with other sequenced Chlorellales (table 2). Examples include 1) a polyketide synthase family (Beta-ketoacyl-ACP synthase), involved in the fatty acid chain formation and production of secondary metabolites (Hopwood 1997); 2) a DNA helicase Pif1 family involved in DNA repair and genome stability in telomeres in yeast (Pinter et al. 2008); and 3) a Zinc finger SWIM-type family, whose members bind DNA and thus may encode transcription factors (Laity et al. 2001). Supplementary figure S8, Supplementary Material online, shows the original expansion plot.

Table 2.

Expanded Gene Families with Functional Annotation in Picochlorum costavermella

| Gene Family | Annotation | Thermotolerance | pco | pse3 | cnc64a | hes | apr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOM03P000145 | Beta-ketoacyl synthase, N-terminal | 23 | 6 | 11 | 10 | 8 | |

| HOM03P000255 | DNA helicase Pif1-like | 2 UP | 21 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HOM03P003865 | DNA helicase activity | 1 UP | 9 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HOM03P007225 | Zinc finger, SWIM-type | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| HOM03P004586 | NA | 1 DOWN | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HOM03P005416 | NA | 1 DOWN | 16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HOM03P005472 | NA | 1 DOWN | 15 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HOM03P005761 | NA | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| HOM03P006264 | NA | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| HOM03P006665 | NA | 2 DOWN | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HOM03P006777 | NA | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| HOM03P008212 | NA | 1 DOWN | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HOM03P008563 | NA | 1 DOWN | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HOM03P009301 | NA | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note.—Columns 4–8 show the number of genes per family in each species (pco = P. costavermella, pse3 = Picochlorum SE3, cnc64a = Chlorella variabilis NC64A, hes = Helicosporidium sp., apr = Auxenochlorella protothecoides). The list of genes of each gene family is detailed in supplementary table S9, Supplementary Material online.

Most genes (71%) in these 14 expanded gene families underwent a tandem duplication event, compared with 8% in the genome (hypergeometric test, P value: 2.7e-104). On the other hand, the fraction of genes in these expanded gene families which underwent a block duplication is 37.5%, compared with 4.5% in the genome (P value: 4.6e-48). Block duplicates refer to genes located in duplicated collinear regions that originated through segmental, chromosomal, or genome duplication. However, for genes uniquely duplicated through block duplication, there was no enrichment compared with the global frequency of block duplication (9.4% vs. 15.4% genome-wide). Hence, tandem duplication seems to have been the main contributor to the expansion of these gene families.

Horizontal Gene Transfers

An automated phylogenetic pipeline was developed to identify horizontal gene transfer events in Picochlorum. Hence, 928 trees were built using IQ-TREE in combination with running a model-selection function (ModelFinder), which were subsequently sorted using PhySortR to detect nonexclusive bacterial clades. Phylogenies of interest were manually inspected to identify candidates for HGT with at least 95% ultrafast bootstrap support for the sister-group relationship between the Picochlorum genus and prokaryotes and to detect trees containing only prokaryotes next to Picochlorum sequences. Twenty-six bacterial HGT candidates could be identified using this approach, of which 8 were previously reported as HGT events in Picochlorum SE3 (Foflonker et al. 2015) (table 3, asterisk). The HGT genes are distributed globally across the genome (supplementary fig. S9, Supplementary Material online). It is worth noting that 22 out of 26 HGT candidates contain no intron, a higher fraction compared with the rest of the genome (P value= 0.007), reflecting their bacterial origin. Phylogenetic trees for each new candidate are shown in supplementary figures S10–S35, Supplementary Material online.

Table 3.

Overview of All Detected HGT Genes

| Picochlorum costavermella | Annotation | P. SE3 | Intron Length (bp) | P. soloecismus | Expression in Standard Culture | MMETSP | Thermotolerance | Halotolerance P. SE3 | ModelFinder | Supplementary Figure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCC4223.01g00410 | Aldolase-type TIM barrel | contig_19.g49 | / | NSC_05964 | ✓ | DOWN | DE | WAG+F+R2 | S10 | |

| RCC4223.01g01950 | Concanavalin A-like lectin/glucanase domain | contig_89.g395 | / | VT+F+R2 | S11 | |||||

| RCC4223.01g10000 | Peptidase S9 | contig_85.g647 | 73 | DE | WAG+F+R7 | S12 | ||||

| RCC4223.01g10500 | Sulfatase-modifying factor enzyme | contig_85.g685* | / | UP | WAG+F+R2 | S13 | ||||

| RCC4223.02g02200 | Glycosyl transferase, group 2 family protein | contig_231.g589* | 72 | DE | LG+F+R6 | S14 | ||||

| RCC4223.02g09070 | Alkaline phosphatase-like / Sulfatase | / | / | ✓ | LG+F+R6 | S15 | ||||

| RCC4223.03g07630 | Polyketide synthase, phosphopantetheine-binding domain | contig_45.g406 | 75 | DE | WAG+F+R6 | S16 | ||||

| RCC4223.03g09660 | / | contig_45.g248 | / | ✓ | UP | DE | WAG+F+R2 | S17 | ||

| RCC4223.04g03490 | UvrD-like Helicase, ATP-binding domain | contig_144.g770 | / | DE | LG+F+R7 | S18 | ||||

| RCC4223.04g04250 | Glycerol dehydrogenase | contig_91.g462 | / | ✓ | DE | LG+F+R5 | S19 | |||

| RCC4223.05g03280 | / | contig_41.g86* | / | ✓ | LG+F+R4 | S20 | ||||

| RCC4223.05g04070 | Alpha-1,2-mannosidase | contig_15.g22* | / | NSC_00617 | WAG+F+R6 | S21 | ||||

| RCC4223.07g00090 | NTF2-like domain | contig_122.g492 | / | ✓ | DE | WAG+F+R3 | S22 | |||

| RCC4223.08g00570 | Sheath polysaccharide-degrading enzyme | contig_28.g272* | / | NSC_03444 | ✓ | UP | DE | WAG+F+R5 | S23 | |

| RCC4223.08g02730 | / | / | / | NSC_06393 | LG+F+R4 | S24 | ||||

| RCC4223.08g04290 | Glucose-methanol-choline oxidoreductase | contig_227.g893 | / | DE | WAG+F+R2 | S25 | ||||

| RCC4223.09g01720 | / | / | / | VT+F+R5 | S26 | |||||

| RCC4223.09g01760 | Pyridoxal phosphate-dependent transferase | / | / | ✓ | UP | LG+F+R3 | S27 | |||

| RCC4223.09g01800 | Hexapeptide repeat | / | / | ✓ | LG+F+R2 | S28 | ||||

| RCC4223.09g03890 | Sheath polysaccharide-degrading enzyme | contig_201.g667* | / | DE | WAG+F+R5 | S29 | ||||

| RCC4223.09g04341 | Glycosyl transferase, family 1 | / | 138 | VT+F+R5 | S30 | |||||

| RCC4223.10g04270 | Carbohydrate-binding family v xii | contig_205.g902* | / | ✓ | ✓ | VT+F+R5 | S31 | |||

| RCC4223.11g02450 | Glycosyltransferase 2-like | contig_275.g915 | / | NSC_02286 | WAG+F+R5 | S32 | ||||

| RCC4223.12g02700 | Glycosyltransferase 2-like | contig_275.g915 | / | NSC_02286 | WAG+F+R6 | S33 | ||||

| RCC4223.18g00250 | Cellulase (glycosyl hydrolase family 5) | contig_29.g85* | / | ✓ | LG+F+R3 | S34 | ||||

| RCC4223.23g00090 | / | / | / | ✓ | WAG+F+R3 | S35 |

Note.—Differentially expressed genes in heat stress are marked in the column thermotolerance. HGT events which are shared with P. SE3 and present in the MMETSP Picochlorum transcriptomes are displayed in the last two columns. Previously detected HGT genes in P. SE3 are denoted by an asterisk. *Picochlorum SE3 refer to Foflonker et al. (2016).

To investigate whether these HGT genes are common and expressed in the Picochlorum genus, a protein similarity search using BLAST was performed against the relevant transcriptomes present in the MMETSP project (Keeling et al. 2014) (MMETSP1161: P. oklahomensis CCMP2329, MMETSP1330: P. sp. RCC944). Hits having at least 75% sequence identity and 75% alignment coverage were considered homologous to the gene of horizontal origin, yielding six expressed HGT genes (table 3). Eight genes show expression using a transcript per million (TPM) cut-off >2 profiled in a nontreated culture. Five out of the eight previously reported HGT cases in P. SE3 where found to be expressed having an EST coverage > 10 (Foflonker et al. 2015). In total, 19 genes were found to be expressed in the Picochlorum genus and 18 genes have shared ancestry for the HGT event.

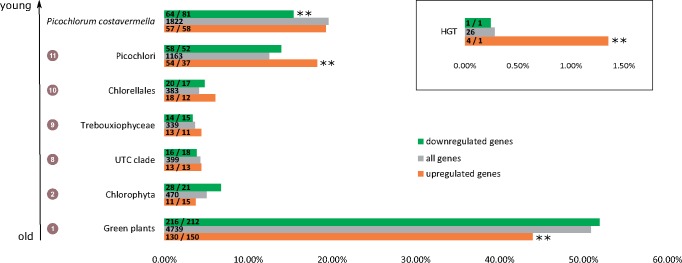

Differential Expressed Genes at Higher Temperature

To study the transcriptional response of P. costavermella genes to growth under high temperature, RNA-Seq transcript profiling was performed. Differential gene expression comparing 20 and 35 °C found 712 genes (P value <0.01, log2-fold change of 1, 3 biological replicates), that is, ∼8% of all protein-coding genes, of which 296 were up-regulated and 416 were down-regulated (supplementary table S10, Supplementary Material online). Four up-regulated and one down-regulated gene are of horizontal descent, which is a significantly higher proportion than expected by chance (fig. 3, inset). Furthermore, three and seven up- and down-regulated genes are also part of eight expanded gene families, containing genes with helicase activity and unknown functions, respectively (table 2).

Fig. 3.—

Phylogenetic stratification of differentially expressed genes in Picochlorum costavermella. One asterisk denotes significant variations compared with background (gray bar) at P value ≤0.05, ** at ≤0.01. Numbers in circles indicate ancestral nodes in figure 2. The numbers in the bars refer to the actual (left) and expected (right) instances for each phylostratum category.

Using transcript abundance as a proxy for amino-acid abundance, there is a change in the amino-acid composition in the up-regulated versus the down-regulated genes; with significantly more Leu, Ser, and Trp and significantly less Asp, Ala, and Met (supplementary fig. S36, Supplementary Material online). This amino acid composition shift is also reflected in amino acid content estimation of all transcripts of the cell: the proteome of cells growing at 35 °C contains significantly more Pro and Thr, and significantly less Met, Gly, Phe, and Val, though the estimated percentage amino acid content difference is small (with a maximum 3% decrease of Met frequency and a maximum 2% increase in Thr frequency).

GO enrichment analysis (supplementary tables S11 and S12, Supplementary Material online) suggests that many genes up-regulated at 35 °C are involved in proteolysis and encode serine-type endopeptidases and proteins with nucleosome and DNA helicase activity. Among the enriched gene families for up-regulated genes, is a serine incorporator/TMS membrane protein (TDE1/TMS) family, which can function in incorporating serine into membranes (Inuzuka et al. 2005). In addition, there is an enrichment for the heat shock protein Hsp90, histone H2A, a serine peptidase family, a ubiquitin-specific protease family and a serine protein kinase family. In contrast, GO terms appearing more frequently in the down-regulated genes at 35 °C are: 1) metal ion and cation binding proteins; 2) catabolic process associated to glycine metabolism; 3) proteins of the thylakoid membrane, photosynthesis, and photosystem reaction.

Among the overrepresented families in the down-regulated responsive genes, are gene families involved in photosynthesis such as RuBisCO, a light harvesting chlorophyll a/b binding family and an ATPase F0 complex protein. It is important to note that while expression of these genes is down-regulated, expression of these genes is maintained at 35 °C. In addition, gene families of down-regulated genes are involved in metal binding, that is, a family required for maturation of [4Fe–4S] proteins, the SufB FeS assembly machinery family, and a calcium-binding EF-hand domain family. Other gene families are fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, a SMP lipid binding domain family, universal stress protein A family, a FAS1 domain family, a HAD hydrolase family, a biotin carboxylase family, and a DNA helicase family.

Phylostratigraphy of Differentially Expressed Gene Families

To investigate the role of ancient and young genus- or species-specific genes in thermotolerance transcriptional responses, we investigated the age of the gene families of differentially expressed genes at 20 and 35 °C based on the results of the DOLLOP analysis, where each gene was assigned to a phylostratum. A phylostratum describes, for each gene, the lowest common ancestor of the species that contain a homolog of the gene. Here, seven phylostrata were defined, from the green plants stratum to the P. costavermella specific stratum (fig. 3). A general trend was that up-regulated genes tend to belong to younger gene families and are significantly underrepresented in the ancient gene families (44% up-regulated gene families are dated at the ancestor of green plants, while 51% gene families genome wide belong to this phylostratum). Down-regulated genes on the other hand were significantly underrepresented in P. costavermella specific gene families (14 and 15% of down-regulated gene families are Picochlorum genus specific or P. costavermella specific, respectively). The same observation can be made in the long-term response to both hyper-and hyposalinity in Picochlorum SE3 (supplementary fig. S37, Supplementary Material online), indicating that similar phylostrata are over- or underrepresented for different stresses in Picochlorum species. Publicly available heat stress data sets in C. reinhardtii (Voss et al. 2011) and A. thaliana (Matsuura et al. 2010; Nguyen et al. 2015) were examined to determine whether this pattern might be evolutionary conserved (supplementary fig. S38, Supplementary Material online). Intriguingly, downregulated genes exhibit enrichment for old genes and depletion for younger ones during heat stress in C. reinhardtii, while upregulated genes do not display the opposite pattern. Upregulated genes due to heat stress applied for 1 h in A. thaliana (Nguyen et al. 2015) displayed the expected described pattern, while responsive genes to short-term heat treatment did not (Matsuura et al. 2010).

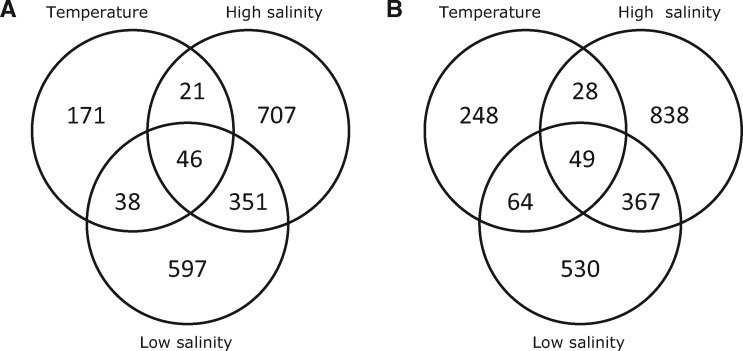

Analysis of the Overlap between Halotolerance and Thermotolerance Response

To analyze whether the thermotolerance response overlaps with the response to higher or lower salinity in P. costavermella, the thermal gene expression changes were compared, gene family-wise, to the response to high and low salinity in P. SE3 (Foflonker et al. 2016). Surprisingly, a third of the gene families up-regulated at 35 °C were also up-regulated under increasing salt concentration (fig. 4A and supplementary table S13, Supplementary Material online) (105/276, binomial test, P value <0.001), and a third of the down-regulated gene families were shared in both conditions (fig. 4B and supplementary table S14, Supplementary Material online) (141/389, binomial test, P value <0.001), suggesting positive cotolerance to changes in osmolarity and temperature (Vinebrooke et al. 2004). Many shared up-regulated gene families are related to DNA maintenance, such as histone families H2A/H2B/H3, DNA-directed DNA polymerase family B, a structural maintenance of chromosome protein (SMC), the DNA replication initiation factor CDC45 and a regulator of chromosome condensation family (RCC1). Heat shock factor Hsp90 family, a family enriched at 35 °C, is up-regulated under both hyper and hyposalinity. Another up-regulated family is a SBP-box transcription factor family. Common down-regulated gene families include families related to photosynthesis, such as multiple chlorophyll A–B binding protein families, two photosystem II (PSII) oxygen-evolving complex PsbP families, a cytochrome b5 family and an ATPase (F0 complex—subunit B) family. Several thioredoxin domain families, one iron hydrogenase, one FeS cluster insertion protein and one 4Fe–4S ferredoxin-type, iron–sulphur binding domain family were down regulated. In addition, two zinc finger (GATA-type and CCCH-type) transcription factor families are part of the common response.

Fig. 4.—

Venn diagrams of the overlap between the up-regulated (A) and down-regulated (B) gene families in high temperature in Picochlorum costavermella, low and high salt concentration in P. SE3.

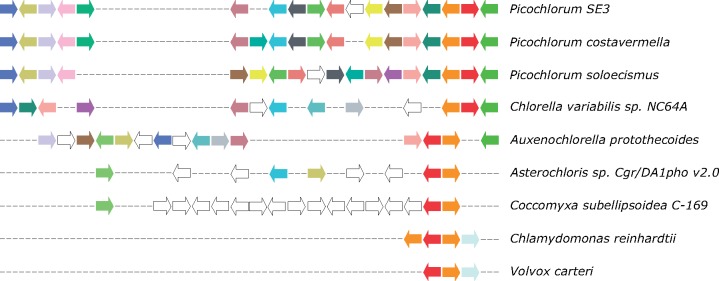

Evolution of Syntenic Regions

To investigate the conservation of genome organization, we determined collinear regions showing conserved gene content and order in Trebouxiophyceae. Globally, 6,184 genes are syntenic between the two Picochlorum genomes. The fraction of syntenic genes in P. costavermella (66.7%) is lower than in P. SE3 (88.9%), probably because of the higher number of genes in P. costavermella (see fig. 2). However, the synteny between P. costavermella and Chlorella CNC64A is higher (30.5%) compared with the synteny between P. SE3 and Chlorella CNC64A (27.9%), probably reflecting the more contiguous assembly of the former. Only six large within-species syntenic blocks containing at least five syntenic genes were found, indicating the absence of genome duplications in P. costavermella. Synteny plots are available in Supplementary Material online (supplementary fig. S39, Supplementary Material online).

To estimate how deep collinearity is conserved, we identified 4,008 P. costavermella genes which are collinear with at least one member of the Chlorellales, being Chlorella variabilis NC64A, Auxenochlorella protothecoides, and Helicosporidium sp. On the other hand, 428 genes are retained across Trebouxiophyceae, thus being collinear with at least one member of the Chlorellales and Asterochloris sp. or Coccomyxa subellipsoidea C-169. Next, we determined which fraction of these genes form divergent gene pairs. These are genes facing away from each other, implying the possibility for a bidirectional promoter. 29% of genes conserved across Chlorellales formed these divergent gene pairs, while 15% did across Trebouxiophyceae. To check whether this specific gene configuration can be linked with conserved stress response, we selected those divergent gene pairs where both members are differentially expressed during thermotolerance and had the same expression pattern. Two cases were found to comply to these rules across Chlorellales: a pair consisting out of one gene with a fatty acid desaturase domain and one with unknown function (RCC4223.17g00510–RCC4223.17g00520), the second pair involves a HAD hydrolase and gene with unknown function (RCC4223.07g01190–RCC4223.07g01180). One differential expressed divergent gene pair (fig. 5) specifically conserved across the UTC clade was found, namely a heat shock protein 70 family member (orange; RCC4223.07g00490) and a heat shock protein 90 family member (red; RCC4223.07g00500). Not only are both proteins up-regulated at 35 °C, their orthologs in P. SE3 (contig_16.g26.t1 and contig_16.g27.t1, respectively) were also differentially expressed in high and low salinity (Foflonker et al. 2016). This indicates that the Hsp70–Hsp90 gene pair is not only evolutionary constrained as a syntenic region specific to the UTC clade but also shows a transcriptional stress response in Picochlorum.

Fig. 5.—

Representation of the genomic region around the Hsp70–Hsp90 gene pair in the UTC clade. The heat shock protein 70 family member (orange; RCC4223.07g00490) and a heat shock protein 90 family member (red; RCC4223.07g00500) were found to occur in a divergent gene pair across the UTC clade.

Discussion

Diversity and Environmental Prevalence of Picochlorum

Picochlorum species are small (1–3 µm) unicellular oblong cells surrounded by a cell wall with no morphological discriminating character and a dozen strains have been isolated in diverse marine and saline habitats (Henley et al. 2004) from the Mediterranean sea, the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean. Picochlorumcostavermella was isolated from an estuary, but metabarcoding of water from nearby marine sampling sites suggests that this species is present both in a coastal (SOLA) and an offshore marine station (MOLA), as well as in a lagoon (fig. 1B). Compared with another unicellular green picoalga (cell diameter <2 µm) isolated from the same environment, O. tauri (Mamiellophyceae), P. costavermella has a broader ecological range: while it is not as competitive in standard temperature and salinity conditions, it outcompetes O. tauri in more extreme salinities and temperatures (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). Its genome divergence with P. SE3, estimated by the average amino acid identity between orthologous genes is 88%, one percent higher than the amino-acid identity between humans and mice. Its unique sequence of the highly conservative 18S rDNA gene makes us confident that this is a novel species (Piganeau et al. 2011). The democratization of genomic approaches is poised to hasten further genome-based progress in understanding the diversity and evolution of the green clade (Peers and Niyogi 2008). The large halotolerance spectrum of the Picochlorum species stresses the difficulty to restrict the habitat of some microalga to marine or freshwater. Interestingly, additional evidence of halotolerance in microalgae may shed new light on the debate about the low versus high salinity habitat of early photosynthetic eukaryotes (Nakov et al. 2017; Sanchez-Baracaldo et al. 2017).

Genome Streamlining

Genome reduction is a dominant mode of genome evolution, consistent with the optimization of initially more complex larger genomes, witnessing the acquisition of adaptive innovations (Wolf and Koonin 2013). Genome reduction is manifested in two ways in Picochlorum. First, by a reduction of intergenic size; P. costavermella has a very gene dense nuclear genome of 13.3 Mb, with a mean intergenic and intron length of 220 and 88 bp, respectively. This contraction is particularly extreme in the organellar genomes, as they represent some of the most reduced but completely functional organellar genomes described in Trebouxiophyceae. Both chloroplast and mitochondria have the highest protein coding density among the Trebouxiophyceae (supplementary fig. S7, Supplementary Material online), while retaining all common functionalities (supplementary tables S4–S7, Supplementary Material online).

Second, a reduction of the number of gene families; Picochlorum has lost 1,462 gene families, the largest number of losses observed in our assembled Chlorophyta data set of 18 species, except for Helicosporidium. The gene families’ impoverishment in Helicosporidium may be a consequence of its lifestyle as an obligate parasite (Pombert et al. 2014). However, the reason for the large number of losses in the Picochlorum genus, and also in the Mamiellales ancestor, remains enigmatic, as these species do not show parasitic lifestyles.

In the following sections, the transcriptomic responses observed under basal thermotolerance at 35 °C in P. costavermella (supplementary table S10, Supplementary Material online) will be discussed.

Gene Expression Changes Impacting Cell Wall and Membrane Fluidity

The cell wall is a complex and biochemically incredibly diverse structure that changes with abiotic stresses, including heat stress (Gall et al. 2015). In Brassica rapa, the up-regulation of genes involved in cell wall modification has been linked to an increased cell wall size and acquired thermotolerance (Yang et al. 2006). While the biochemical composition of microalgal cell wall requires further investigation (He et al. 2016), genes involved in cell wall are globally upregulated in P. costavermella (supplementary table S10, Supplementary Material online). In particular, three glycoside hydrolase family members, three glycosyl transferase genes, an alpha-1,2-mannosyltransferase, a plastid alpha-amylase which generates maltose and functions as an alternative energy source, and a peptidoglycan binding protein, are up-regulated.

Higher temperature results in increased membrane fluidity (Mittler et al. 2012). To counter this effect and to restore normal membrane viscosity, fatty acid metabolism is fine-tuned. First, polyunsaturated fatty acids are exchanged for de novo synthesized saturated fatty acids. Second, longer fatty acid chains are favored over shorter chains. Consistent with the former expectation, two fatty acid desaturases (RCC4223.12g01860 and RCC4223.17g00510), which convert saturated into unsaturated fatty acids, are strongly down-regulated at high temperature. The orthologous gene of RCC4223.17g00510 in C. reinhardtii is a ω-3 fatty acid desaturase that localizes to the chloroplast, but affects both plastidic and extraplastidic membrane lipids (Nguyen et al. 2013). Consistent with the second expectation, a mitochondrial and cytosolic β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase involved in the biosynthesis of unsaturated VLCFA (very long chain fatty acids) are up-regulated, performing the second step in the biosynthesis of fatty acids. Moreover, long chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase is down-regulated. This enzyme catalyses the prestep reaction for β-oxidation (breakdown) of fatty acids. In addition, the mitochondrial electron transfer flavoprotein ETF beta, which can function as a sink for FADH2 generated in the first step of this oxidation, is down-regulated. The net effect is the presence of more saturated FAs, which fits with the previously described way of dealing with increased fluidity due to heat stress.

Gene Expression Changes Impacting Photosynthesis and the Calvin Cycle

Both components of photosystem I (PsaC, PsaE, PsaF, PsaK, PsaL, PsaN, PPD1), photosystem II (PsbP, PsbR, PsbW), and chlorophyll a/b binding proteins (PsbS, LHCA3, LHCB1, LHCB2, ELIP) were down-regulated. The decrease in gene expression of both PSI/II genes, albeit still expressed, strongly suggests that light reactions were reduced in dividing P. costavermella cells at high temperatures.

The Calvin cycle, the process that fixes CO2 into carbohydrates, was also down-regulated. Both members of the Rubisco small subunit along with its activator Rubisco activase, sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, and ribulose-5-phosphate-3-epimerase were down-regulated, the first three enzymes control the metabolic flux of the pathway. The decrease in four key enzymes of the Calvin Cycle strongly supports the notion that light-independent reactions were inhibited. Rubisco deactivation may be a protective acclimation strategy to achieve heat tolerance. Again, these results corroborate the observed pattern of down-regulation, but not complete suppression of light-related energy generation.

Gene Expression Changes Impacting Maintenance of Protein Homeostasis

A temperature increase causes protein unfolding and the cell must maintain a balance between protein stability and turnover, that is, the synthesis and degradation of proteins. Chaperones prevent protein aggregation by assisting in proper folding or targeting of substrates to one of the many proteases. In contrast to mainly up-regulation of HSP genes in early heat stress response in Chlamydomonas, in thermotolerance profiled in P. costavermella, heat shock factors were both up-and down-regulated. A ClpB chaperone, two HSP90 members, and one HSP70 member were up-regulated. Among those upregulated chaperones were the HSP70 and HSP90 family members, which form a conserved collinear gene pair (fig. 5). Four genes with a DnaJ domain and one gene belonging to the Clp/Hsp100 family were down-regulated. Finally, two genes with a peptidylprolyl isomerases domain, which accelerates protein folding, were up-regulated and another one was down-regulated.

Protein degradation machineries are expressed as part of the stress response, mainly in unicellular organisms, to remove irreversibly damaged proteins. Some chaperones can perform a temperature-dependent switch to a protease function (Spiess et al. 1999). Proteases and peptidases were found to be both up- and down-regulated. Seven peptidases, two genes with an ubiquitinyl hydrolase activity and a serine protease were up-regulated. Seven peptidases and a chloroplast ATP-dependent Clp protease were down-regulated.

Many ribosomal proteins were found to be decreased by high temperature including L1, L6, L13, L17/L22, L28, L29, L31, and L35, while chloroplast-encoded proteins S12 and S18 are up-regulated. Such decreases in many ribosomal proteins demonstrate suppression of ribosome biogenesis, and thus lowering the level of the resource-demanding process of protein synthesis. The down-regulation of photosynthesis and translation processes observed is consistent with the cell monitoring and regulation of the level of translation according to energy status (Kusnadi et al. 2015). N-(5′-phosphoribosyl) anthranilate isomerase (PRAI), the enzyme that catalyzes the third step of tryptophan biosynthesis was also down-regulated. Recently, mutations in the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5B gene (eIF5B, AT1G76810) in Arabidopsis thaliana were shown to produce a thermosensitive phenotype, perhaps arising from the disruption of specific eIF5B interactions with the ribosome, causing translational defects (Zhang et al. 2017). Likewise, the orthologous gene of eIF5B in P. costavermella (RCC4223.03g06830) was up-regulated at 35 °C. On the other hand, neither the orthologous genes in P. SE3 (contig_45.g474.t1) nor in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, were differentially expressed in salt stress and short-term heat stress, respectively, pointing to a specific response of eIF5B in basal thermotolerance in Picochlorum.

Evolutionary Origin of the Thermotolerance Response

Phylostratigraphy analysis revealed that 49% of differentially expressed genes were present in the ancestor of the green lineage. The transcriptomic responses observed under increased temperature in P. costavermella are in part consistent with previous reports following heat and salt stresses in Streptophyta (Larkindale and Vierling 2007). In addition to these previously characterized responses, we observed that genes involved in vitamin B1 (thiamine) production were up-regulated. The TH1 tandem duplicate pair (RCC4223.08g01110–RCC4223.08g01120) and the adjacent THI1 (RCC4223.08g01130) gene share a bidirectional promoter and were up-regulated. This gene organization is only conserved in the genus Picochlorum. Thiamine biosynthesis is up-regulated during heat stress in plants (Ferreira et al. 2006) and up-regulation of THI1 is also seen in short-term heat stress in Chlamydomonas (Hemme et al. 2014). However, the transcription of some genes involved in the resistance to heat shock in Streptophytes, such as ascorbate peroxidase, thioredoxin reductase, protein phosphatase PP7 and multiprotein bridging factor 1c (Mittler et al. 2012; Bokszczanin and Fragkostefanakis 2013; Chae et al. 2013), showed no significant increase in gene expression, highlighting the important distinction between the heat shock and the thermotolerance cellular states.

On the other hand, up-regulated genes were overrepresented in young gene families present only in the genus Picochlorum, including candidate HGT genes. Notably, a HGT gene encoding a sulfatase-modifying factor enzyme is the third most upregulated gene at 35 °C (48-fold change difference), while another HGT gene with unknown function is also 16-fold upregulated and lacks expression data at 20 °C. This suggests that they have conferred an advantage for growth at higher temperatures. Most of the identified HGT genes (19 out of 26) are expressed in at least one member of the Picochlorum genus, implying that these acquisitions occurred in their common ancestor. Although both the amount and the mechanisms of HGT in eukaryotes are under debate (Deschamps and Moreira 2012; Martin 2017; Leger et al. 2018), several previous studies reported that HGT from Bacteria to Archaeplastidae, such as B. prasinos RCC1105 (Moreau et al. 2012), Picochlorum SE3 (Foflonker et al. 2015), C. variabilis NC64A (Blanc et al. 2010), and the red alga Galdiera phlegrea (Qiu et al. 2013), is more prevalent than previously thought. HGT is a fundamental mechanism of adaptation in Bacteria and Archaea enabling the acquisition of new genes involved in metabolic pathways and resistance to stress. Our results support the role of HGT in conferring survival capacity of eukaryotes to extreme environments (Schönknecht et al. 2014).

Author Contributions

M.K., C.H., S.S.B., H.M., N.G. conceived and performed phenotypic assays, RNA and DNA extraction. M.K. and G.P. performed genome assembly. H.L. and S.Y. extracted and analyzed environmental sequence data. S.R. performed nuclear genome annotation and data submission to NCBI and ORCAE. M.K., H.M., G.P., N.G. performed expert annotation. E.V., F.B., and K.V. performed bioinformatic comparative analysis of gene content, gene families, and functional predictions. E.V. performed analysis of gene expression data, HGT detection and organellar genome annotation. K.V. and G.P. conceived the project. M.K., E.V., K.V., and G.P. wrote the first version of the manuscript, which was edited and approved by all authors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all members of the GENOPHY lab for support and stimulating discussions, Marie-Line Escande for help with electron microscopy, and the GenoToul Bioinformatics platform from Toulouse, France, for bioinformatics analysis support and GenoToul cluster availability. Metabarcoding was funded by ANR DECOVIR (coordinator: Yves Desdevises), and S.Y. was funded by ANR REVIREC ANR 12-BSV7-0006-01 (coordinator: N.G.). F.B. was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. H2020-MSCA-ITN-2015-675752. This work was funded by BOF project GOA01G01715 to K.V. and E.V. and ANRJCJC-SVSE6-2013-0005 to G.P. and S.S.B.

Literature Cited

- Aboal M, Werner O.. 2011. Morphology, fine structure, life cycle and phylogenetic analysis of Phyllosiphon arisari, a siphonous parasitic green alga. Eur J Phycol. 46(3):181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ.. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 215(3):403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W.. 2015. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 31(2):166–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker EW. 2007. Micro-algae as a source of protein. Biotechnol Adv. 25(2):207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black CK, Mihai DM, Washington I.. 2014. The photosynthetic eukaryote Nannochloris eukaryotum as an intracellular machine to control and expand functionality of human cells. Nano Lett. 14(5):2720–2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G, et al. 2010. The Chlorella variabilis NC64A genome reveals adaptation to photosymbiosis, coevolution with viruses, and cryptic sex. Plant Cell 22(9):2943–2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc-Mathieu R, et al. 2014. An improved genome of the model marine alga Ostreococcus tauri unfolds by assessing Illumina de novo assemblies. BMC Genomics 15(1):1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boetzer M, Henkel CV, Jansen HJ, Butler D, Pirovano W.. 2011. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics 27(4):578–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokszczanin KL, Fragkostefanakis S.. 2013. Perspectives on deciphering mechanisms underlying plant heat stress response and thermotolerance. Front Plant Sci. 4:315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH.. 2015. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods 12(1):59–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae HB, et al. 2013. Thioredoxin reductase type C (NTRC) orchestrates enhanced thermotolerance to Arabidopsis by its redox-dependent holdase chaperone function. Mol Plant 6(2):323–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T-Y, Lin H-Y, Lin C-C, Lu C-K, Chen Y-M.. 2012. Picochlorum as an alternative to Nannochloropsis for grouper larval rearing. Aquaculture 338–341:82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Chin C-S, et al. 2013. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat Methods 10(6):563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clerck O, Bogaert KA, Leliaert F.. 2012. Diversity and evolution of algae: primary endosymbiosis. Adv Bot Res. 64:55–86. [Google Scholar]

- de la Vega M, Díaz E, Vila M, León R.. 2011. Isolation of a new strain of Picochlorum sp. and characterization of its potential biotechnological applications. Biotechnol Prog. 27(6):1535–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps P, Moreira D.. 2012. Reevaluating the green contribution to diatom genomes. Genome Biol Evol. 4(7):683–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, et al. 2013. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 29(1):15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32(5):1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright AJ, Van Dongen S, Ouzounis CA.. 2002. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 30(7):1575–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajkus J, Sykorova E, Leitch AR.. 2005. Telomeres in evolution and evolution of telomeres. Chromosome Res Int J Mol Supramol Evol Asp Chromosome Biol. 13(5):469–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. 2005. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package) version 3.6. Distributed by the author. Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle.

- Ferreira S, et al. 2006. Proteome profiling of Populus euphratica Oliv. Upon heat stress. Ann Bot. 98(2):361–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foflonker F, et al. 2015. Genome of the halotolerant green alga Picochlorum sp. reveals strategies for thriving under fluctuating environmental conditions. Environ Microbiol. 17(2):412–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foflonker F, et al. 2016. The unexpected extremophile: tolerance to fluctuating salinity in the green alga Picochlorum. Algal Res. 16:465–472. [Google Scholar]

- Foissac S, Bardou P, Moisan A, Cros M-J, Schiex T.. 2003. EUGENE’HOM: a generic similarity-based gene finder using multiple homologous sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 31(13):3742–3745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl T. 1995. Inferring taxonomic positions and testing genus level assignments in coccoid green lichen algae: a phylogenetic analysis of 18s ribosomal RNA sequences from dictyochloropsis reticulata and from members of the genus Myrmecia (chlorophyta, Trebouxiophyceae Cl. Nov.)1. J Phycol. 31(4):632–639. [Google Scholar]

- Gall HL, et al. 2015. Cell wall metabolism in response to abiotic stress. Plants 4(1):112–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Esquer CR, Twary SN, Hovde BT, Starkenburg SR.. 2018. Nuclear, chloroplast, and mitochondrial genome sequences of the prospective microalgal biofuel strain Picochlorum soloecismus. Genome Announc. 6(4):e01498–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]