Abstract

The data was obtained from a field survey aimed at measuring the patterns of utilization of mental healthcare services among people living with mental illness. The data was collected using a standardized and structured questionnaire from People Living with Mental Illness (PLMI) receiving treatment and the care-givers of People Living with Mental Illness. Three psychiatric hospitals in Ogun state, Nigeria were the population from which the samples were taken. Chi-square test of independence and correspondence analysis were used to present the data in analyzed form.

Keywords: Survey, Utilization questionnaire, Survey analytics, Statistics, Mental health, Psychiatry

Specification Table

| Subject Area | Psychology |

|---|---|

| More Specific subject area | Quantitative Psychology and Mental Health |

| Type of data | Table and text file |

| How data was acquired | Field survey |

| Data format | Raw, partial analyzed |

| Experimental factors | Pattern of utilization of mental healthcare services |

| Experimental features | Only those receiving treatments and the care-givers (in the case of very unstable patients) were considered. Also only those residents in the study areas were considered. Adults younger than 18 years were also excluded. |

| Data Source location | Covenant University Sociology Laboratory, Ota, Nigeria |

| Data accessibility | All the data are in this data article |

Significance of the data

-

•

The central theme is the study of utilization of mental healthcare facilities among people living with mental illness.

-

•

The data could be useful in monitoring the extent to which the mental health services are available and utilized.

-

•

The study can be replicated to other countries with similar demographic factors.

-

•

The data can be used in the overall study of mental health.

1. Data

The data is a summary of responses from a field survey. Structured questionnaires were administered to People Living with Mental Illness (PLWMI) and their caregivers and the aim is to measure the patterns of utilization of mental healthcare services among PLWMI.

Only those receiving treatments and the care-givers (in the case of very unstable patients) were considered. Also, those residents in the study areas that are of Yoruba origin were considered. Adults younger than 18 years were excluded from the study.

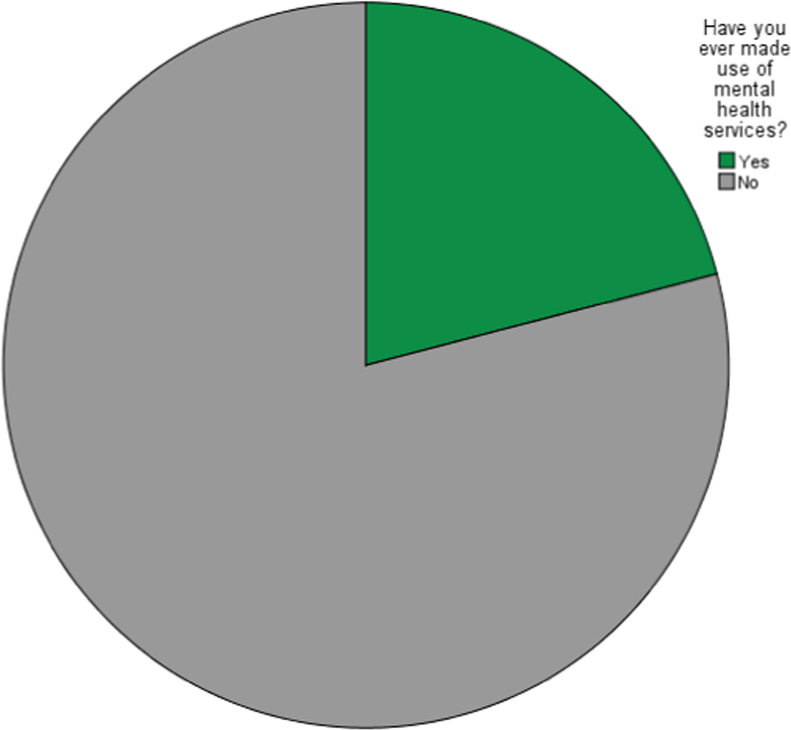

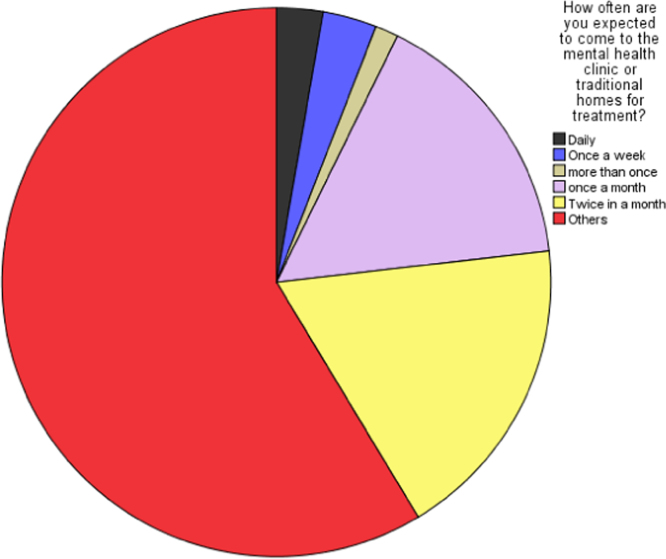

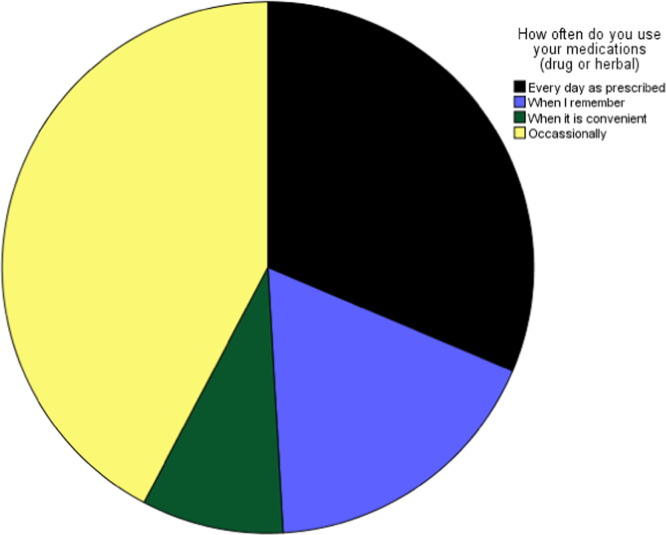

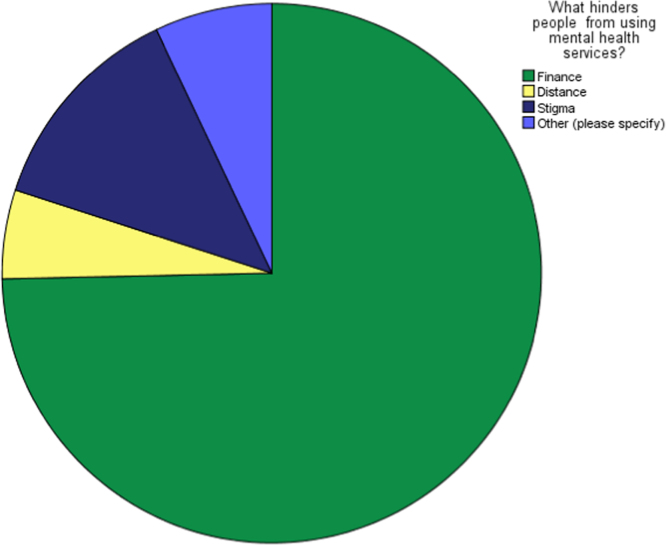

The pattern of utilization mental healthcare services in this context was determined by the perceived use of the mental healthcare services by the respondents, frequency of use, frequency of taking prescribed medications and the perceived obstacle of using the available mental healthcare services. These are shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4. The raw data can be assessed as Supplementary data 1 and the questionnaire can be assessed as Supplementary data 2.

Fig. 1.

Perceived use of the mental healthcare services by the respondents.

Fig. 2.

Perceived frequency of use of the mental healthcare services by the respondents.

Fig. 3.

Frequency of taking prescribed medications.

Fig. 4.

Perceived obstacle of using the available mental healthcare services.

2. Experimental design, materials and methods

Mental illness has been believed by numerous experts to be caused amongst others by depression, alcohol and substance abuse, stress, violence against women or minors, post-traumatic stress disorder, women׳s infertility and biological factors. Mental health in particular requires special help, care and management. The treatment may come as psychotherapy and medications which are available in mental healthcare services. The availability of mental health services determines their patterns of usage or utilization [1], [2], [3], [4], [5].

Utilization is connected with ease of use, excellence service, good customer relations, affordable fees charge, management and socio-economic factors.

Questionnaire was used in this article to measure the pattern of utilization of mental healthcare services in Psychiatric hospitals located in three local Government areas of Ogun state, Nigeria. The utilization of the mental healthcare services in the demographics of the study area in particular and Nigeria in general are historically low due to long distance, unavailability of medications, stigmatization, epileptic or skeletal services, poor road networks, poverty and dearth of skilled psychiatrics [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. Generally, the following statistical analysis and survey methods in these articles can be useful [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30].

2.1. Contingency analysis

Chi-square test of independence was used to determine the association between the measure of utilization of mental healthcare services and the socio-demographics of the respondents and is presented in Table 1, Table 2.

Table 1.

Contingency analysis between the usage of mental services and the soocio-demographic variables.

| Socio-demographic factors | Chi-square | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.153316 | 0.695387 |

| Age | 5.595044 | 0.347636 |

| Marital status | 12.941725 | 0.023931 |

| Religion | 2.046284 | 0.562856 |

| Level of education | 7.503471 | 0.483409 |

| Occupation/ Profession | 12.302178 | 0.138222 |

| Income | 3.307660 | 0.507719 |

| Duration of residency in the studied area | 5.069540 | 0.407453 |

| Family type | 2.222229 | 0.329192 |

| Form of marriage | 1.108207 | 0.574587 |

Table 2.

Contingency analysis between the perceived hindrance of mental services and the soocio-demographic variables.

| Socio-demographic factors | Chi-square | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 2.667740 | 0.445737 |

| Age | 40.262166 | 0.000414 |

| Marital status | 20.179331 | 0.165161 |

| Religion | 6.378052 | 0.701566 |

| Level of education | 32.969706 | 0.104714 |

| Occupation/ Profession | 31.410814 | 0.142287 |

| Income | 7.675522 | 0.809946 |

| Duration of residency in the studied area | 20.965525 | 0.137934 |

| Family type | 7.046988 | 0.316524 |

| Form of marriage | 4.321635 | 0.633238 |

Remarks: P-value less than 0.05 imply association.

2.2. Correlational analysis

The correlational studies are important to reveal the strength and nature of the observed linear relationship that exist between the measure of utilization and the socio-demographic variables. These are presented in Table 3, Table 4.

Table 3.

Correlational analysis between the usage of mental services and the soocio-demographic variables.

| Socio-demographic factors | Pearson׳s R | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | -0.012084 | 0.695721 |

| Age | 0.026051 | 0.399072 |

| Marital status | -0.088972 | 0.003910 |

| Religion | -0.017942 | 0.561412 |

| Level of education | -0.037189 | 0.228575 |

| Occupation/ Profession | -0.030210 | 0.328092 |

| Income | -0.036221 | 0.240918 |

| Duration of residency in the studied area | 0.015793 | 0.609235 |

| Family type | -0.009194 | 0.766027 |

| Form of marriage | -0.006283 | 0.838854 |

Table 4.

Correlational analysis between the perceived hindrance of mental services and the soocio-demographic variables.

| Socio-demographic factors | Pearson׳s R | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | -0.001236 | 0.968093 |

| Age | 0.078624 | 0.010815 |

| Marital status | -0.032353 | 0.294916 |

| Religion | 0.002405 | 0.937959 |

| Level of education | -0.025976 | 0.400421 |

| Occupation/ Profession | -0.038578 | 0.211642 |

| Income | 0.018045 | 0.559159 |

| Duration of residency in the studied area | 0.028956 | 0.348574 |

| Family type | 0.037799 | 0.221030 |

| Form of marriage | -0.032385 | 0.294450 |

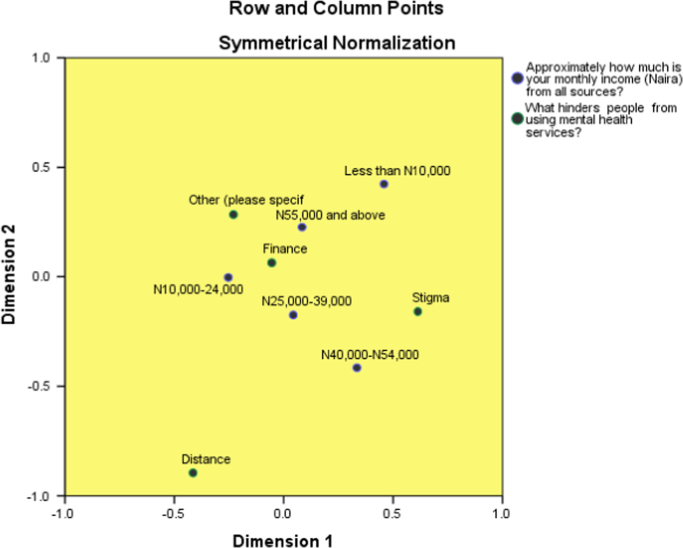

2.3. Correspondence analysis

Correspondence analysis is performed to visually display the contributions of the income of the respondents to the hindrance from using mental health services. Details on correspondence analysis can be found in [31], [32], [33], [34], [35].

The results are presented as follows: Correspondence table (Table 5), model summary (Table 6), overview row points (Table 7), overview column points (Table 8) and biplot (Fig. 5).

Table 5.

Correspondence table of patterns of utilization of mental healthcare services among people living with mental illness.

| What hinders people from using mental health services? | Approximately how much is your monthly income (Naira) from all sources? |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than N10,000 | N10,000–24,000 | N25,000–39,000 | N40,000-N54,000 | N55,000 and above | Active Margin | |

| Finance | 68 | 346 | 100 | 107 | 163 | 784 |

| Distance | 2 | 27 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 56 |

| Stigma | 14 | 50 | 18 | 25 | 29 | 136 |

| Other (please specify) | 6 | 34 | 8 | 9 | 17 | 74 |

| Active Margin | 90 | 457 | 134 | 151 | 218 | 1050 |

Table 6.

model summary of patterns of utilization of mental healthcare services among people living with mental illness.

| Dimension | Singular Value | Inertia | Chi Square | Sig. | Proportion of Inertia |

Confidence Singular Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accounted for | Cumulative | Standard Deviation | Correlation | |||||

| 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.064 | 0.004 | 0.557 | 0.557 | 0.031 | -0.098 | ||

| 2 | 0.055 | 0.003 | 0.411 | 0.968 | 0.029 | |||

| 3 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.032 | 1.000 | ||||

| Total | 0.007 | 7.676 | 0.810a | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||

The p value indicates that the income of the respondents is not associated with the hindrance they encountered in the utilization of mental healthcare services.

12 degrees of freedom

Table 7.

Overview row points table of patterns of utilization of mental healthcare services among people living with mental illness.

| What hinders people from using mental health services? | Mass | Score in Dimension |

Inertia | Contribution |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Of Point to Inertia of Dimension |

Of Dimension to Inertia of Point |

||||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Total | |||||

| Finance | .747 | -.055 | .065 | .000 | .035 | .057 | .409 | .484 | .893 |

| Distance | .053 | -.415 | -.896 | .003 | .144 | .780 | .199 | .799 | .998 |

| Stigma | .130 | .613 | -.158 | .003 | .762 | .059 | .943 | .054 | .997 |

| Other (please specify) | .070 | -.230 | .285 | .001 | .059 | .104 | .326 | .428 | .755 |

| Active Total | 1.000 | .007 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

Table 8.

Overview column points table of patterns of utilization of mental healthcare services among people living with mental illness.

| Approximately how much is your monthly income (Naira) from all sources? | Mass | Score in Dimension |

Inertia | Contribution |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Of Point to Inertia of Dimension |

Of Dimension to Inertia of Point |

||||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Total | |||||

| Less than N10,000 | .086 | .458 | .424 | .002 | .282 | .281 | .566 | .416 | .981 |

| N10,000–24,000 | .435 | -.254 | -.003 | .002 | .439 | .000 | 1.000 | .000 | 1.000 |

| N25,000–39,000 | .128 | .044 | -.174 | .000 | .004 | .071 | .048 | .644 | .691 |

| N40,000-N54,000 | .144 | .334 | -.416 | .002 | .252 | .453 | .426 | .565 | .991 |

| N55,000 and above | .208 | .084 | .227 | .001 | .023 | .195 | .124 | .780 | .905 |

| Active Total | 1.000 | .007 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

a. Symmetrical normalization

Fig. 5.

Biplot showing the perceived relationship in graphical form.

Remarks: The data was explained by two dimensions. Distance seems not to be perceived hindrance to utilization of mental healthcare services in the studied area.

Acknowledgements

The research was sponsored by the Covenant University Centre for Research, Innovation and Development (CUCRID), Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria.

Footnotes

Transparency data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2018.06.086.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2018.06.086.

Transparency document. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Makanjuola V., Esan Y., Oladeji B., Kola L., Appiah-Poku J., Harris B., Gureje O. Explanatory model of psychosis: impact on perception of self-stigma by patients in three sub-saharan African cities. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016;51(12):1645–1654. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1274-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heijnders M., Van Der Meij S. The fight against stigma: an overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2006;11(3):353–363. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jorm A.F., Korten A.E., Jacomb P.A., Christensen H., Henderson S. Attitudes towards people with a mental disorder: a survey of the Australian public and health professionals. Austr. New Zeal. J. Psychiatry. 1999;33(1):77–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.1999.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kabir M., Iliyasu Z., Abubakar I.S., Aliyu M.H. Perception and beliefs about mental illness among adults in Karfi village, northern Nigeria. BMC Int. Health Human. Rights. 2004;4:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-4-3. (art. no. 3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laganathan S., Murthy S.R. Experiences of stigma and discrimination endured by people suffering from schizophrenia. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2008;50:39–46. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.39758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ndetei D.M., Mutiso V., Maraj A., Anderson K.K., Musyimi C., McKenzie K. Stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness among primary school children in Kenya. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016;51(1):73–80. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olawande T.I., Jegede A.S., Edewor P.A., Fasasi L.T., Samuel G.W. An exploration of gender differences on availability of mental healthcare services among the Yoruba of Ogun State, Nigeria. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health Hum. Resil. 2018;20(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olawande T.I., Jegede A.S., Edewor P.A., Fasasi L.T. Gender differentials in the perception of mental illness among the Yoruba of Ogun State, Nigeria. Ife Psychol. 2018;26(1):134–153. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odejide A.O., Olatawura M.O. A survey of community attitudes to the concept and treatment of mental illness in Ibadan, Nigeria. Niger. Med. J. : J. Niger. Med. Assoc. 1979;9(3):343–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oduguwa T.O., Akinwotu O.O., Adeoye A.A. A comparative study of self stigma between HIV/AIDS and schizophrenia patients. J. Psychiatry. 2014;17(2):525–531. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ola B., Suren R., Ani C. Depressive symptoms among children whose parents have serious mental illness: association with children׳s threat-related beliefs about mental illness. South Afr. J. Psychiatry. 2015;21(3):74–78. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olugbile O., Zachariah M.P., Kuyinu A., Coker A., Ojo O., Isichei B. Yoruba world view and the nature of psychotic illness. Afr. J. Psychiatry. 2009;12(2):149–156. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v12i2.43733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ronzoni P., Dogra N., Omigbodun O., Bella T., Atitola O. Stigmatization of mental illness among Nigerian schoolchildren. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2010;56(5):507–514. doi: 10.1177/0020764009341230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose D., Thornicroft G., Pinfold V., Kassam A. 250 Labels used to stigmatise people with mental illness. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2007;7 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-97. (art. no. 97) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sartorius N. Iatrogenic stigma of mental illness. Br. Med. J. 2002;324(7352):1470–1471. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7352.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iroham C.O., Okagbue H.I., Ogunkoya O.A., Owolabi J.D. Survey data on factors affecting negotiation of professional fees between Estate Valuers and their clients when the mortgage is financed by bank loan: a case study of mortgage valuations in Ikeja, Lagos State, Nigeria. Data Brief. 2017;12:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okagbue H.I., Opanuga A.A., Oguntunde P.E., Ugwoke P.O. Random number datasets generated from statistical analysis of randomly sampled GSM recharge cards. Data Brief. 2017;10:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okagbue H.I., Opanuga A.A., Adamu M.O., Ugwoke P.O., Obasi E.C.M., Eze G.A. Personal name in Igbo Culture: a dataset on randomly selected personal names and their statistical analysis. Data Brief. 2017;15:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bishop S.A., Owoloko E.A., Okagbue H.I., Oguntunde P.E., Odetunmibi O.A., Opanuga A.A. Survey datasets on the externalizing behaviors of primary school pupils and secondary school students in some selected schools in Ogun State, Nigeria. Data Brief. 2017;13:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adejumo A.O., Ikoba N.A., Suleiman E.A., Okagbue H.I., Oguntunde P.E., Odetunmibi O.A., Job O. Quantitative exploration of factors influencing psychotic disorder ailments in Nigeria. Data Brief. 2017;14:175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li S., Su B., Sui P.C., Zhang G. Online survey data of public subjective well-being on high occupancy vehicle lane in China. Data Brief. 2017;15:862–867. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visscher S.J., van Stel H.F. Practice variation amongst preventive child healthcare professionals in the prevention of child maltreatment in the Netherlands: qualitative and quantitative data. Data Brief. 2017;15:665–686. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alzamil W. The urban features of informal settlements in Jakarta, Indonesia. Data Brief. 2017;15:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrero M.J., Domingo-Salvany A., De la Torre R. Data from roadside screening for psychoactive substances, alcohol and illicit drugs, among Spanish drivers in 2015. Data Brief. 2017;15:160–162. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson J.E. Survey data reflecting popular opinions of the causes and mitigation of climate change. Data Brief. 2017;14:412–439. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.07.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee R., Jones A., Woodgate F., Killough N., Bellamkonda K., Williams M., Handa A. Data for the Oxford Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Study international survey of vascular surgery professionals. Data Brief. 2017;14:298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mwungu C.M., Mwongera C., Shikuku K.M., Nyakundi F.N., Twyman J., Winowiecki L.A., Läderach P. Survey data of intra-household decision making and smallholder agricultural production in Northern Uganda and Southern Tanzania. Data Brief. 2017;14:302–306. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulugeta M., Mirotaw H., Tesfaye B. Dataset on child nutritional status and its socioeconomic determinants in Nonno District, Ethiopia. Data Brief. 2017;14:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alhammami M., Ooi C.-P., Tan W.-H. Violent actions against children. Data Brief. 2017;14:480–484. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charalambous M., Konstantinos M., Talias M.A. Data on motivational factors of the medical and nursing staff of a Greek Public Regional General Hospital during the economic crisis. Data Brief. 2017;11:371–381. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benzecri J.P. Marcel Decker; New York: 1992. Correspondence Analysis, Handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yelland P.M. An introduction to correspondence analysis. Math. J. 2010;12:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okagbue H.I., Edeki S.O., Opanuga A.A. Correspondence analysis for the trend of human African trypanosomiasis. Res. J. Appl. Sci., Eng. Technol. 2016;13(6):448–453. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okagbue H.I., Adamu M.O., Owoloko E.A., Opanuga A.A. Correspondence analysis of the global epidemiology of cutaneous and Visceral Leishmaniasis. Indian J. Nat. Sci. 2015;6(31):8634–8652. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doey L., Kurta J. Correspondence analysis applied to psychological research. Tutorials Quant. Method Psychol. 2011;7(1):5–14. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material