Abstract

Despite the development of advanced therapeutic regimens such as molecular targeted therapy and immunotherapy, the 5-year survival of patients with lung cancer is still less than 20%, suggesting the need to develop additional treatment strategies. The molecular chaperone heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) plays important roles in the maturation of oncogenic proteins and thus has been considered as an anticancer therapeutic target. Here we show the efficacy and biological mechanism of a Hsp90 inhibitor NCT-50, a novobiocin-deguelin analog hybridizing the pharmacophores of these known Hsp90 inhibitors. NCT-50 exhibited significant inhibitory effects on the viability and colony formation of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells and those carrying resistance to chemotherapy. In contrast, NCT-50 showed minimal effects on the viability of normal cells. NCT-50 induced apoptosis in NSCLC cells, inhibited the expression and activity of several Hsp90 clients including hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, and suppressed pro-angiogenic effects of NSCLC cells. Further biochemical and in silico studies revealed that NCT-50 downregulated Hsp90 function by interacting with the C-terminal ATP-binding pocket of Hsp90, leading to decrease in the interaction with Hsp90 client proteins. These results suggest the potential of NCT-50 as an anticancer Hsp90 inhibitor.

Introduction

To maintain homeostasis during various extracellular and intracellular insults, cancer cells rely on heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) to stabilize many proteins, constructing signaling networks responsible for cell survival, growth, and proliferation1,2. Indeed, Hsp90 client proteins are associated with the hallmarks of cancer3,4 and thus targeting Hsp90 has been considered an efficient anticancer therapeutic strategy4. Several Hsp90 inhibitors with various structural backbones have shown potent anticancer activities in vitro and in vivo5. However, none of these inhibitors have been approved for use in the clinic, and several clinical trials using Hsp90 inhibitors have been discontinued due to minimal effects and toxicity. Hence, it is necessary to develop safer and more effective Hsp90 inhibitors.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related human deaths worldwide. Despite extensive efforts to develop efficient therapeutic interventions, the 5-year survival rate for lung cancer is less than 20%6,7. Based on several problems with chemotherapy, such as unselective toxicity, drug resistance, and recurrence, agents selectively targeting overactivated signaling pathways in cancer cells have been extensively developed and now several drugs are used as the first-line therapy for patients with lung cancer carrying relevant genetic alterations8. Although some therapies have initially shown remarkable anticancer effects9,10, recurrence due to drug resistance is an inevitable consequence of these targeted therapies in most cases. Thus, there is an urgent unmet need to develop more efficacious anticancer agents that can be utilized as a monotherapy or an adjuvant therapy with other anticancer drugs.

Natural products are considered an important source for the development of anticancer drugs11. We have demonstrated the anticancer and cancer chemopreventive effects of a naturally occurring rotenoid deguelin12–17. Further studies revealed Hsp90 as the molecular target for deguelin’s antitumor effect18. However, the potential toxic effects of deguelin, such as a Parkinson’s disease-like syndrome19, hamper the further clinical utility of deguelin. Novobiocin, another natural product, is derived from Streptomyces and is a coumarin antibiotics with Hsp90 inhibiting activity2,20,21. However, it’s half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) has been reported to be up to 700 μM22, making it difficult to utilize as a clinical therapeutic.

To circumvent the limitation of deguelin, we have developed several deguelin analogs that harbor less or no potential toxicity to various normal cells16,23–27. We and others previously demonstrate the involvement of the dimethoxy benzopyran moiety of deguelin in the interaction with Hsp9018 and the crucial association of the acylamino moiety with the antiproliferative activity of novobiocin28. Importantly, the structural features of deguelin and novobiocin, which are highlighted in three different colors, indicate that they share principal pharmacophores (Fig. 1a). Thus, in addition to our previous efforts on the development of ring-truncated deguelin analogs23–27, here we synthesized a novel novobiocin-deguelin analog, designated 5-methoxy-N-(3-methoxy-4-(2-(pyridin-4-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)-2,2-dimethyl-2H-chromene-6-carboxamide (NCT-50), by hybridizing pharmacophores of these compounds and evaluated the effects of NCT-50 on the viability of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells, which account for 80–85% of lung cancer29. NCT-50 displayed significant inhibitory effects on the viability and colony formation of NSCLC cells with minimal effects on the viability of normal cells. NCT-50 also induced apoptosis in NSCLC cells and inhibited pro-angiogenic activities of NSCLC cells. Further mechanistic investigation revealed that NCT-50 disrupted Hsp90 function by interacting with the ATP-binding pocket in the C-terminal domain of Hsp90 and concomitantly suppressed the expression and activity of multiple Hsp90 clients, including hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α. These results demonstrate the potential use of NCT-50 as an Hsp90-targeting anticancer agent.

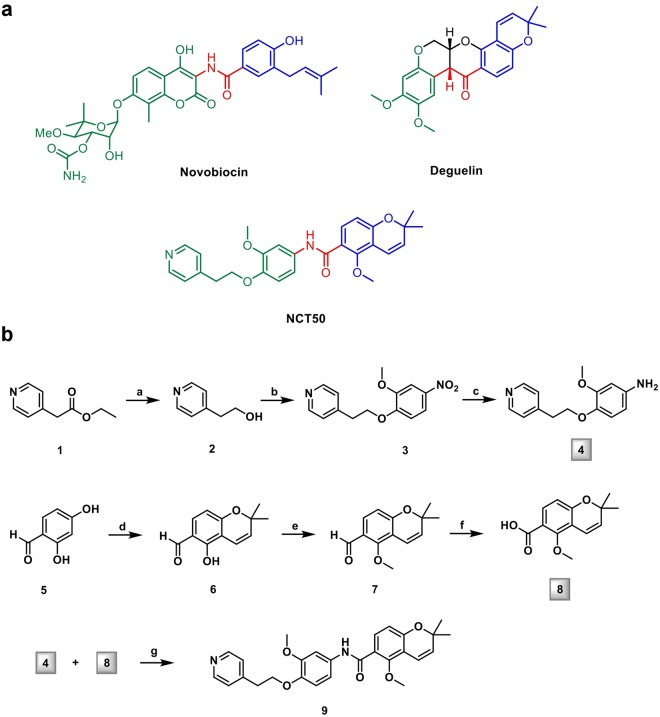

Figure 1.

Synthesis of NCT-50. (a) The chemical structures of novobiocin, deguelin, and NCT-50. (b) Synthetic scheme of NCT-50.

Results

Synthesis of NCT-50

NCT-50 is a derivative designed as a simplified hybrid of novobiocin and deguelin to form the three principal pharmacophores. Structurally, NCT-50 has 2,2-dimethyl-2H-chromene and 1-methoxy-2-((pyridin-4-yl)ethoxy)phenyl rings linked by an amide bond (Fig. 1a). Two key intermediates, the aniline in the left part (4) and the carboxylic acid of the chromene moiety (8), were synthesized and then coupled to each other (Fig. 1b).

NCT-50 significantly inhibits the viability and colony-forming ability of NSCLC cells with minimal effect on the viability of normal cells

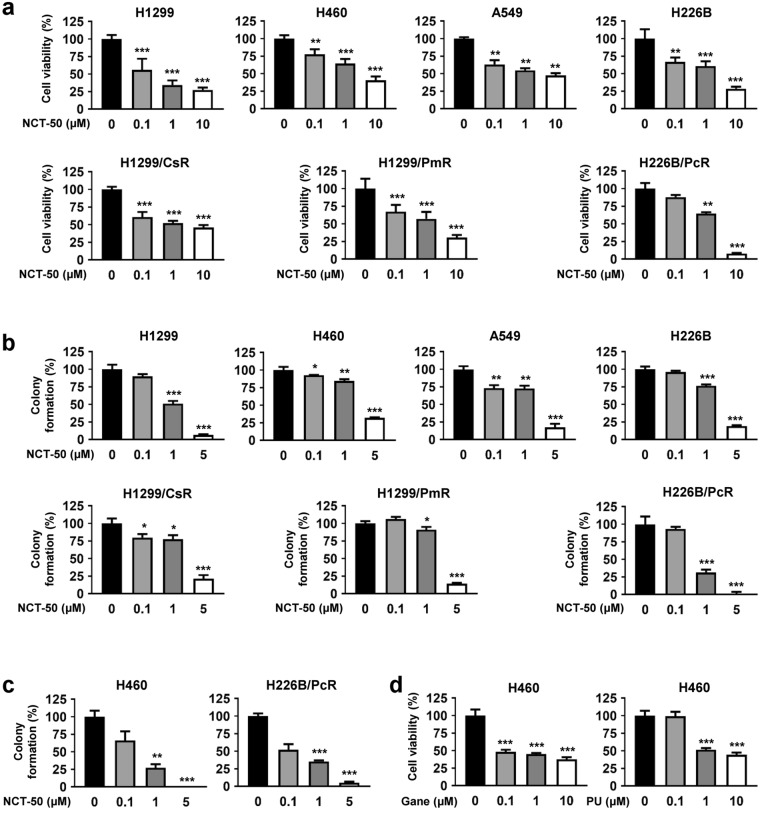

We then examined the effect of NCT-50 on the viability and colony formation of human NSCLC cells, either naïve or resistant to anticancer drugs23, considering that resistance to chemotherapy is a large obstacle for efficient anticancer therapeutics. NCT-50 significantly inhibited the viability and anchorage-dependent colony formation of NSCLC cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2a,b). The IC50 values of NCT-50 on the inhibition of NSCLC cell viability were about 2 μM on average (Table 1), which was comparable or superior to previously developed deguelin analogs23,24,26, novobiocin, and its analogs22,28,30. The inhibitory effect of NCT-50 on the viability and anchorage-dependent colony formation of drug-resistant sublines (H1299/CsR, H1299/PmR, and H226B/PcR) was comparable with that on the corresponding naïve cells (H1299 and H226B), suggesting the effectiveness of NCT-50 for both chemo-naïve and chemo-resistant NSCLC cells (Fig. 2a,b). Consistent with these results, the colony formation of NSCLC cells (either chemo-naïve or chemoresistant), under anchorage-independent culture conditions, was also markedly suppressed by treatment with NCT-50, especially at the concentration of 5 μM (Fig. 2c), indicating the effectiveness of NCT-50 in suppressing the tumorigenicity of NSCLC cells, regardless of their drug resistance status. NCT-50 displayed weak but comparable cytotoxic effects in NSCLC cells compared with known Hsp90 inhibitors that have been evaluated in clinical trials such as ganetespib and PU-H7131,32 (Fig. 2d). These results suggest that NCT-50 suppresses the survival and the colony-forming ability of both chemo-naïve and chemo-resistant NSCLC cells.

Figure 2.

Effects of NCT-50 on the viability and colony formation of NSCLC cells. (a) NSCLC (H1299, H460, A549 and H226B) cells and those carrying resistance to cisplatin (H1299/CsR), pemetrexed (H1299/PmR), and paclitaxel (H226B/PcR) were treated with increasing concentrations of NCT-50 (a) for 3 days. Cell viability was determined by the MTT assay. (b,c) The anchorage-dependent (b) and -independent (c) colony formation of NSCLC cells treated with increasing concentrations of NCT-50 was determined as described in Methods. (d) H460 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of ganetespib (Gane) or PU-H71 (PU) for 3 days. Cell viability was determined by the MTT assay. The bars represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test compared with vehicle-treated control group.

Table 1.

The IC50 values showing the inhibitory effects of NCT-50 on the cell viability.

| Type | Name | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| NSCLC cells | H1299 | 0.23 |

| H460 | 3.44 | |

| A549 | 2.22 | |

| H226B | 1.63 | |

| H1299/CsR | 1.47 | |

| H1299/PmR | 1.42 | |

| H226B/PcR | 1.54 | |

| Retinal pigment epithelial cells | RPE | >10 |

| Human umbilical vein endothelial cells | HUVEC | >10 |

| Human lung epithelial cells | HBE | >10 |

| BEAS-2B | >10 | |

| Murine hippocampal neuronal cells | HT-22 | >10 |

The IC50 values of NCT-50 for the suppression of the viability of indicated cells were calculated by non-linear regression analysis.

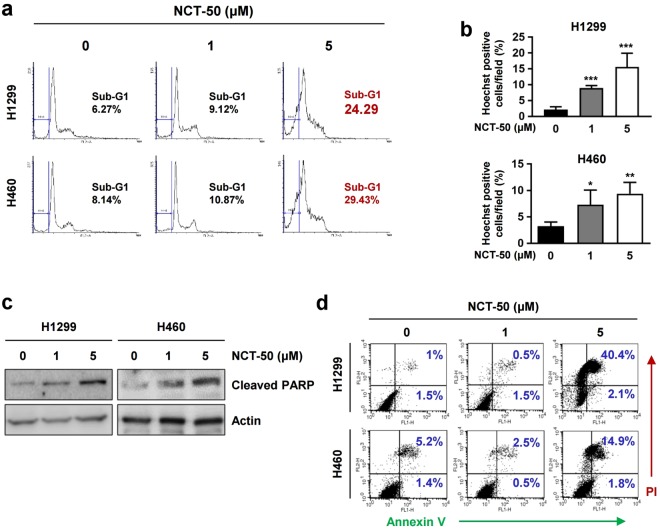

Induction of apoptosis is associated with NCT-50-medated suppression of NSCLC cell viability

According to the efficient inhibitory effects of NCT-50 on the viability and colony-forming ability of NSCLC cells, we investigated the underlying mechanism. First, using flow cytometry, we examined the effect of NCT-50 on cell cycle progression. As shown in Fig. 3a, approximately 30% of the cell population was accumulated in the sub-G1 phase in H1299 and H460 cells after treatment with 5 μM NCT-50. Hoechst 33258 staining also showed increased chromatin condensation, a feature of apoptotic cells33, in NCT-50-treated cells (Fig. 3b). Western blot analysis also revealed obviously increased levels of poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage in the two cell lines after the drug treatment (Fig. 3c). Consistently, the Annexin V-positive population was markedly increased in the drug-treated cells (Fig. 3d). These results indicated apoptotic activities of NCT-50 in NSCLC cells, suggesting that the reduced NSCLC cell viability after treatment with NCT-50 is due, in part, to increased apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Association of apoptosis with NCT-50-induced cell death. (a–d) H1299 and H460 cells were treated with NCT-50 for 2 days. (a) The distribution of cells in each phase of the cell cycle was analyzed by flow cytometry. (b) Condensed, fragmented or degraded nuclei was analyzed by Hoechst 33258 staining and counted. (c) The level of cleaved PARP expression was analyzed by Western blot analysis. (d) The annexin V-positive cell population was determined by flow cytometry as described in Methods. The bars represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test compared with vehicle-treated control group.

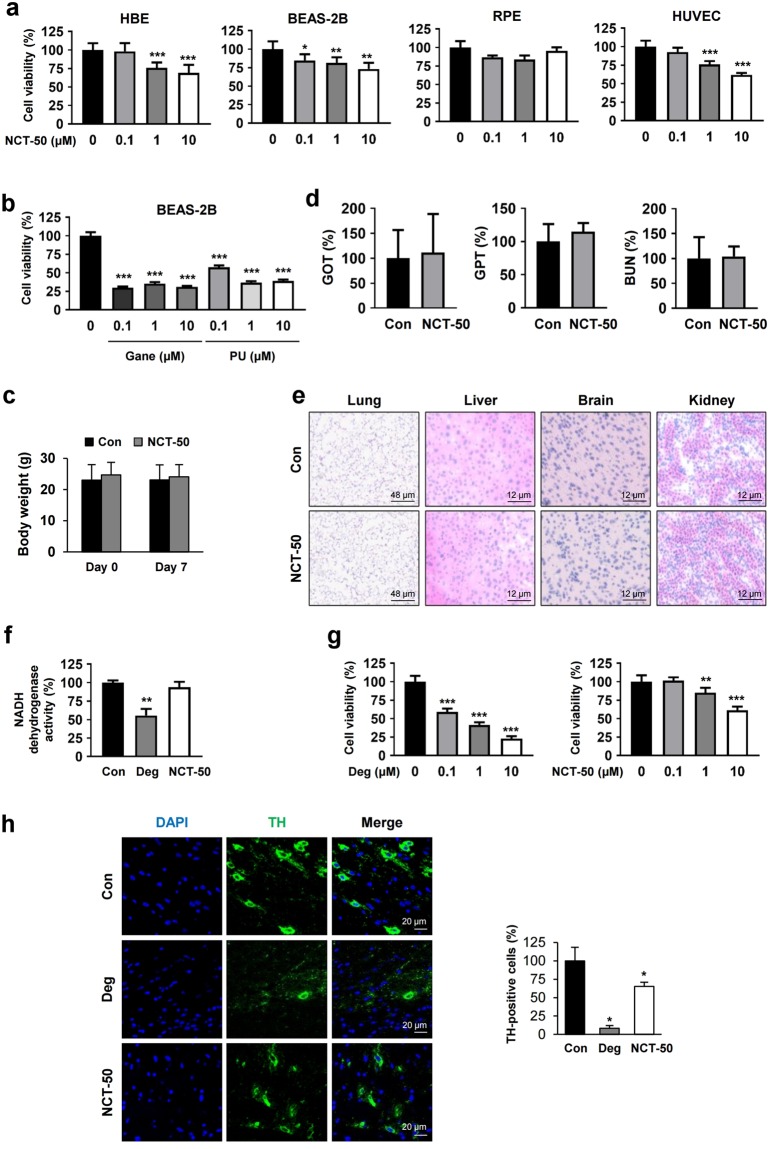

NCT-50 displays improved safety profiles compared with known Hsp90 inhibitors and deguelin

Considering the potential toxic effect of Hsp90 inhibitors34 and deguelin19, we next examined whether NCT-50 has improved safety profiles compared to these known Hsp90 inhibitors. First, we assessed cytotoxicity of NCT-50 at the cellular levels by testing the effects of NCT-50 on the viability of several normal cells, including two human normal lung epithelial cells (HBE and BEAS-2B), human retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE), and human vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs). Compared to various cancer cell lines treated with NCT-50 (Fig. 2), these normal cell lines showed minimal changes in their viability after the treatment with NCT-50 (10 μM) (Fig. 4a). The IC50 values of NCT-50 on the viability of these normal cells was over 10 μM (Table 1). Moreover, in contrast to minimal cytotoxic effect of NCT-50, known Hsp90 inhibitors such as ganetespib and PU-H71 displayed remarkable cytotoxic effects in BEAS-2B cells, suggesting reduced toxicity of NCT-50 compared with these Hsp90 inhibitors (Fig. 4b). We further performed several in vivo experiments to evaluate toxicity profiles of NCT-50. Mice in a FVB background were orally administered with 4 mg/kg NCT-50 twice a day for 7 consecutive days. Compared with vehicle-treated mice, NCT-50-treated mice displayed no significant changes in body weight (Fig. 4c). The serum levels GOT (glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase), GPT (glutamate pyruvate transaminase), and blood urea nitrogen (BUN), indicators of liver and renal function35,36, were not significantly different between vehicle- and NCT-50-treated mice (Fig. 4d). Moreover, histological analyses of H&E-stained tissue samples obtained from several organs (lung, liver, brain, and kidney) of NCT-50-treated mice revealed no remarkable histopathological changes (Fig. 4e). These results collectively indicate minimal toxicities of NCT-50.

Figure 4.

Improved safety of NCT-50 compared with known Hsp90 inhibitors and deguelin. (a) Various normal cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or NCT-50 (0.1, 1, and 10 μM) for 3 days. Cell viability was determined by the MTT assay. (b) BEAS-2B cells were treated with increasing concentrations of Hsp90 inhibitors [ganetespib (Gane) or PU-H71 (PU)] for 2 days. Cell viability was determined by the MTT assay. (c) Body weight changes between vehicle- (control) and NCT-50-treated mice. (d) The level of GOT, GPT, and BUN in the serum was determined as described in Methods and expressed as a percentage of vehicle-treated control group. (e) The histopathological changes in liver, lung, brain, and kidney from mice treated with vehicle or NCT-50 were evaluated by H&E-stained section of the tissues. The representative images were shown. (f) Spectrophotometric analysis of NADH dehydrogenase activity using mitochondria-enriched fractions was performed as described in Methods. (g) HT-22 cells were treated with various concentrations of deguelin or NCT-50 for 2 days. Cell viability was determined by the MTT assay. (h) Representative images showing tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the midbrain from vehicle, deguelin, or NCT-50-treated mice. Right. Quantitative analysis of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in each group, expressed as a percentage of vehicle-treated control group. The bars represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test compared with vehicle-treated control group.

According to the concern that deguelin may induce Parkinson’s-like syndrome19, which was manifested by decreased tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the rat brain19, we evaluated the potential neurotoxicity of NCT-50. Because inhibition of NADH dehydrogenase activity was responsible for the potential neurotoxicity of deguelin19, we first determined the effects of NCT-50 and deguelin on NADH dehydrogenase activity using a mitochondria enriched fraction. In contrast to the significant inhibitory effects of deguelin, NCT-50 showed no detectable impact on the mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase activity (Fig. 4f). We further compared the effect of NCT-50 and deguelin on the viability of mouse hippocampal neuronal cell line (HT-22). Compared to deguelin, NCT-50 induced minimal changes in HT-22 cells viability (Fig. 4g).

To verify these in vitro results, we determined in vivo neurotoxicity of NCT-50. To this end, mice were orally administered with NCT-50 or deguelin (4 mg/kg) twice a day for 7 consecutive days. We compared the effects of NCT-50 and deguelin on the immunoreactivity of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), an enzyme in the late-limiting step of dopamine synthesis that has been used as a marker of dopaminergic neuron37,38, in the mouse midbrain. Consistent with the previous findings in the rat brain19,25, the TH immunoreactivity was significantly decreased by deguelin treatment in the mouse midbrain (Fig. 4h). In contrast, NCT-50 treatment minimally altered the level of the TH immunoreactivity. Taken together, these results indicate the markedly improved safety profile of NCT-50 compared with deguelin.

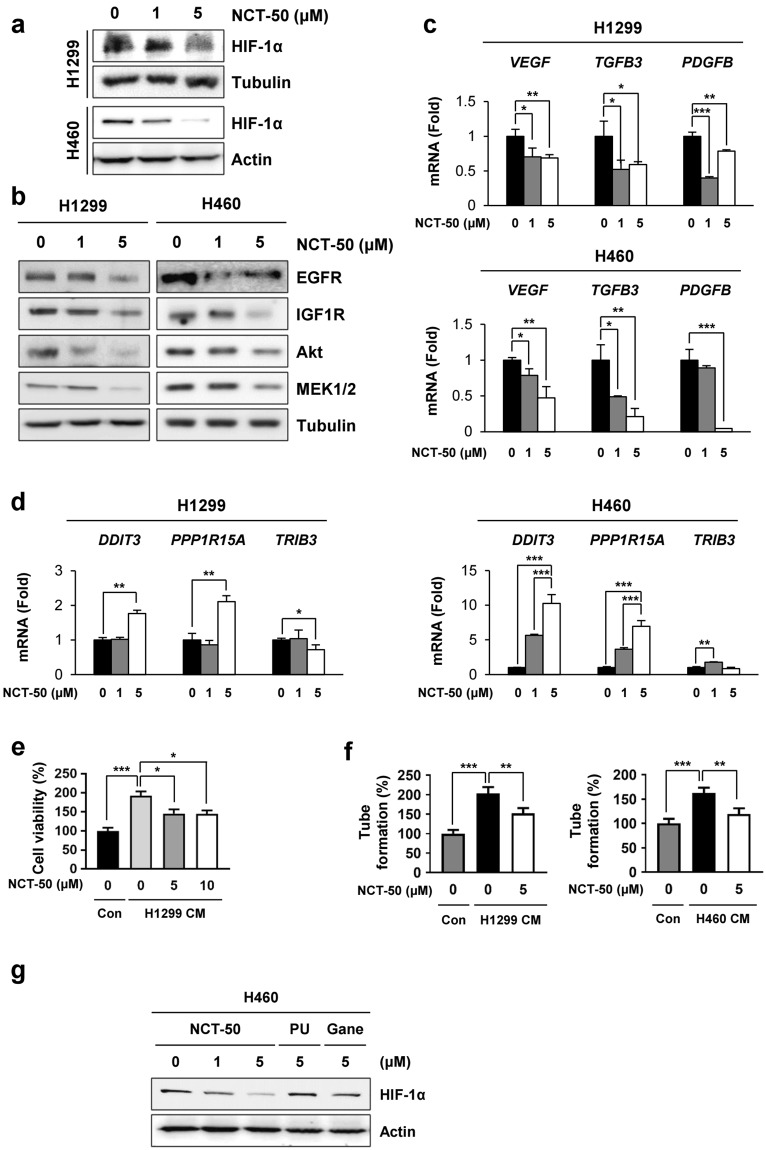

NCT-50 inhibits expression of client proteins of Hsp90 and shows anti-angiogenic activities

Based on the previous studies demonstrating the inhibitory effect of novobiocin20 and deguelin18, we assessed whether NCT-50 could suppress expression of Hsp90 client proteins. Treatment with NCT-50 in hypoxic conditions decreased HIF-1α expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5a). The NCT treatment also inhibited the expression of several Hsp90 client proteins, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), insulin-like growth factor receptor-1 (IGF-1R), Akt, and MEK1/24,39 in normoxic conditions. Moreover, NCT-50 markedly suppressed the expression of HIF-1α target genes (VEGF, TGFB3, and PDGFB40) (Fig. 5b) but not non-HIF target genes [DDIT3 (encoding GADD153/CHOP)41, PPPIR15A (a GADD153-target gene42), and TRIB343] in H1299 and H460 cells (Fig. 5c). According to previous studies on the role of HIF-1α in angiogenesis44 and the antiangiogenic effects of deguelin and its derivatives23,25,45,46, we further examined the antiangiogenic property of NCT-50. Because vascular endothelial cell tube formation ability in Matrigel is a general feature related to angiogenesis47 and angiogenic factors are produced by cancer cells and endothelial or stromal cells48, we assessed the effects of NCT-50 on the tube formation and proliferation of vascular endothelial cells, using the conditioned medium (CM) collected from NCT-50-treated NSCLC cells. In contrast to CM from vehicle-treated H1299 and H460 cells, exposure of HUVECs to CM from NCT-50-treated cells resulted in decreased proliferation (Fig. 5d) and tube formation (Fig. 5e) of HUVECs, indicating that NCT-50 inhibits the production of angiogenic factors by NSCLC cells. Moreover, NCT-50 exhibited improved suppressive effects on HIF-1α expression compared with the known Hsp90 inhibitors, including ganetespib and PU-H71 (Fig. 5f). These findings suggested that Hsp90 function was effectively suppressed by treatment with NCT-50.

Figure 5.

Downregulation of Hsp90 function by treatment with NCT-50. (a,b) H1299 and H460 cells were treated with NCT-50 for 24 h under hypoxic (a) or normoxic (b) conditions. The level of Hsp90 client proteins such as HIF-1α (a), EGFR, IGF1R, Akt, and MEK1/2 (b) was determined by Western blot analysis. (c,d) H1299 and H460 cells were treated with NCT-50 for 24 h. The mRNA expression of HIF-1α target genes (VEGF, TGFB3, and PDGFB) (c) or non-HIF-1α target genes (DDIT3, PPP1R15A, and TRIB3) (d) were determined by real-time PCR analysis. (e,f) HUVECs were treated with CM obtained from NSCLC cells treated with vehicle or NCT-50 (5 or 10 μM). The proliferation (e) and tube formation (f) of HUVECs were determined as described in Methods. (g) H460 cells were treated with NCT-50, ganetespib (Gane) or PU-H71 (PU) for 24 h under hypoxic conditions. The level of HIF-1α expression was determined by Western blot analysis. The bars represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test compared with vehicle-treated control group.

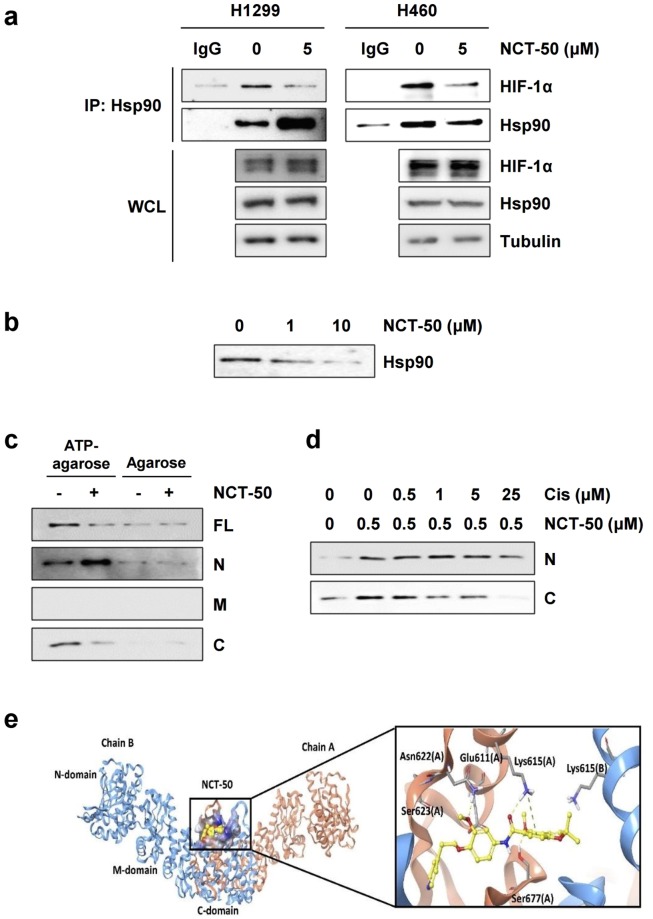

NCT-50 inhibits Hsp90 function by binding to the C-terminal ATP binding pocket of Hsp90

We investigated the inhibitory effect of NCT-50 on Hsp90 function. Because the interaction of Hsp90 with client proteins is essential for its chaperone function49, we examined the effect of NCT-50 on the interaction between Hsp90 and HIF-1α. Under hypoxic conditions, the physical interaction between Hsp90 and HIF-1α was clearly reduced in H1299 and H460 cells after treatment with NCT-50 for 1 hour, when HIF-1α and Hsp90 expression was minimally affected (Fig. 6a). These findings indicated that NCT-50 biologically induce the dissociation of HIF-1α with Hsp90. Hsp90 has been proposed to possesses the ATP-binding pockets in the N-terminal and C-terminal domains2,25,50. To obtain evidence for NCT-50 binding to the ATP-binding pockets of Hsp90, we analyzed the effects of NCT-50 on the binding capacity of recombinant Hsp90 protein to ATP-agarose. We found that the ATP interaction with full length (FL) Hsp90 protein was suppressed by treatment with NCT-50 in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 6b). Subsequent analysis with truncated N-terminal (N) and C-terminal (C) domains revealed that ATP binding to the C domain, but not to the N domain, was markedly affected by NCT-50 treatment (Fig. 6c). To ensure the binding of NCT-50 to the C-terminal ATP-binding site of Hsp90, we performed a competition assay using biotinylated NCT-50 and a known C-terminal Hsp90 inhibitor cisplatin. Preincubation with cisplatin gradually suppressed the binding of biotinylated NCT-50 to the C-terminal domain of Hsp90 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6d). These results collectively suggest the potential of NCT-50 as a C-terminal Hsp90 inhibitor

Figure 6.

NCT-50-mediated inhibition of Hsp90 function by binding to the ATP binding pocket in the C-terminal domain of Hsp90. (a) H1299 and H460 cells were treated with NCT-50 (5 μM) for 1 h, followed by hypoxic incubation for 4 h. Total cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-Hsp90 antibodies. The interaction between HIF-1α and Hsp90 was analyzed by Western blot analysis. (b) Recombinant Hsp90 protein was incubated with ATP-agarose in the presence or absence of NCT-50. The protein bound to the ATP-agarose beads was determined by Western blot analysis. (c) The binding of NCT-50 (5 μM) to full-length (FL) and truncated domains (N: N-terminal; M: middle; C: C-terminal) of recombinant Hsp90 proteins was determined by pull-down assay using ATP-agarose beads. Agarose beads without ATP were used to determine specific binding of Hsp90 proteins to ATP. (d) Competition between NCT-50 and cisplatin for the binding to the N and C domains of Hsp90 was determined by pull-down assay using biotinylated NCT-50. (e) Left. Binding site for NCT-50 in the dimerization interface of open state hHsp90. Chain A is rendered in orange ribbon, and chain B is blue ribbon. The active site is shown as electrostatic property surface map. Red, blue, and white colored regions correspond to negatively charged, positively charged, and neutral areas, respectively. Right. Docked pose of NCT-50 (carbon in yellow). Key amino acid residues within the binding site are rendered in grey capped stick. Hydrogen bonding interactions are depicted as yellow dashed lines and pi-cation interaction is depicted as green dashed lines. A and B indicate chain names.

We further conducted molecular docking analysis using the Surflex-Dox program to evaluate the binding capability of NCT-50. Previously published Hsp90 homology model structure23,25 was used as a receptor for docking in this study. As shown in Fig. 6d, NCT-50 fits well into the C-terminal ATP-binding cavity, locating at central region of dimerization interface of Hsp90 homodimer51. The oxygen atom of acylamino group forms a hydrogen bond with the side-chain of Lys615 in chain A, and the oxygen in the methoxy group forms additional hydrogen bond with the side-chain of Ser677 (A). In addition, benzopyran ring of NCT-50 engages in a cation-π interaction with the side-chain amine of Lys615. These two residues (Lys615 and Ser677) were confirmed as key residues for ATP binding in Hsp90 C-terminal domain by ATP-agarose binding assay in our previous study25. The pyridine and benzene fragment locate in a polar region and oxygen in the methoxy group in the benzene ring forms a hydrogen bond with side chain of Asn622. Overall, our docking model suggests that NCT-50 can efficiently bind to the C-terminal ATP binding site, stabilizing the open conformation of Hsp90 homodimer, which leads to the inhibition of Hsp90.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate the potential of NCT-50 as an Hsp90-targeting anticancer agent with reduced toxicity. NCT-50 significantly inhibited the viability, colony-forming ability, and proangiogenic effect of NSCLC cells. NCT-50 induced the apoptotic cell death of NSCLC cells, but the viability of normal cells was minimally affected by NCT-50 treatment. Moreover, NCT-50 displayed comparable inhibitory effects on the survival and colony formation of NSCLC cells with acquired chemoresistance. Mechanistically, NCT-50 effectively disrupted Hsp90 function by directly binding to the C-terminal ATP-binding pocket of Hsp90, leading to downregulation of the expression and activity of several Hsp90 client proteins including HIF-1α. These data suggest that NCT-50 may have potential as an anticancer drug targeting Hsp90.

An ATPase-containing molecular chaperone, Hsp90 plays an important role in the maintenance and stabilization of numerous client proteins in response to heat shock or other stresses1,2. Cancer cells easily undergo proteotoxic pressure due, in part, to the accumulation of mutated molecules that could lead to cell lethality52. Numerous Hsp90 client proteins are often mutated or overexpressed in several types of human cancer, including NSCLC2,53, and these proteins mediate cancer cell proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, invasion, metastasis, and resistance to conventional or targeted anticancer drugs, such as erlotinib, trastuzumab, paclitaxel, and cisplatin1,2,54–57. Hence, targeting Hsp90 would be an effective way to treat cancer and overcome anticancer drug resistance. Although several clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of Hsp90 inhibitors in lung cancer treatment are ongoing58, the main issues with Hsp90 inhibitors are undesirable side effects, poor water solubility, and toxicity1. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a novel anticancer Hsp90 inhibitor with additional chemical entities or mechanisms of action.

Previously, we demonstrated the potential of a naturally occurring rotenoid deguelin as a potent anticancer agent targeting Hsp90 through direct interaction with the ATP-binding pocket of Hsp9018. However, the potential neurotoxicity of deguelin due to its inhibitory effect on NADH dehydrogenase19 raises concern for its use in cancer patients. Hence, we have attempted to synthesize deguelin analogs to develop novel Hsp90 inhibitors16,23–27. According to the similar structural and mechanistic features between deguelin and novobiocin, here we synthesized a novobiocin-deguelin analog NCT-50 and demonstrated its potential to suppress NSCLC cell viability and proangiogenic ability by inhibiting Hsp90 function. We observed some features of NCT-50 that identify it as a potential hit or chemical lead for the development of anticancer Hsp90 inhibitor. NCT-50 displayed significant cytotoxic and proapoptotic effects on NSCLC cells without significantly affecting the growth of normal cells derived from lung epithelium, retinal pigment epithelium, vascular endothelium and hippocampus. The potency of the inhibitory effect of NCT-50 on the viability of NSCLC cells and Hsp90 function were comparable or superior to that of previously developed deguelin analogs, novobiocin and its analogs, and Hsp90 inhibitors in clinical trials22–24,26,28,30, emphasizing the potential of NCT-50 as a novel and efficacious Hsp90 inhibitor. In addition, considering liver and ocular toxicities are drawbacks of the currently available Hsp90 inhibitors58, the reduced toxicity of NCT-50 in vitro and in vivo compared with known Hsp90 inhibitors or deguelin appears to be a clinically favorable feature. In addition, NCT-50 significantly suppressed proangiogenic ability of NSCLC cells. Because angiogenesis is crucial for tumor growth and metastasis59, the antiangiogenic effect of NCT-50 may disrupt primary tumor growth and lower metastatic burden. Moreover, consistent with previous reports suggesting an association of Hsp90 with anticancer drug resistance and overcoming the resistance to chemo- or targeted anticancer therapies by using Hsp90 inhibitors54–57, NCT-50 was effective in both chemo-naïve and chemoresistant NSCLC cells.. Although additional studies such as animal experiments should be performed to evaluate the effectiveness and toxicity of NCT-50, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy, our results suggest the potential utility of NCT-50 to overcome resistance to paclitaxel, cisplatin, or pemetrexed, which are generally used to treat patients with NSCLC60,61.

Our study reveals that Hsp90 is a molecular target of NCT-50 for its anticancer and antiangiogenic effects. Consistent with the ability of deguelin analogs and novobiocin to interact with the C-terminal ATP binding pocket of Hsp9023,25,62, NCT-50 can interact with the C-terminal ATP binding pocket of Hsp90. Importantly, the acylamino moiety and the benzopyran ring of NCT-50 are crucial for the interaction with Lys615 and Ser677 residues of Hsp90, key residues for ATP binding in the C-terminal ATP binding pocket of Hsp9025. These moieties were previously defined as an important pharmacophore for the interaction of deguelin with Hsp9018 and the antiproliferative effect of novobiocin28. Thus, together with previous findings, our study provides key structural backbone for the development of C-terminal Hsp90 inhibitors.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that NCT-50 exhibits significant cytotoxic and antiangiogenic activities in NSCLC cells by suppressing Hsp90 function through directly binding to the C-terminal ATP-binding pocket of Hsp90, suggesting that NCT-50 can be considered a novel hit compound to further develop as an anticancer Hsp90 inhibitors. Further studies are warranted to investigate the effectiveness of NCT-50 in additional preclinical and clinical settings.

Methods

Reagents

Antibodies against EGFR, Akt, MEK1/2 and tubulin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies against cleaved PARP and HIF-1α were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Antibodies against IGF-1R and actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-goat secondary antibodies were purchased from GeneTex (Irvine, CA, USA). An anti-Hsp90 antibody was purchased from Enzo Life Science (Farmingdale, NY, USA). Ni-NTA agarose was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). ATP-agarose was acquired from Innova Biosciences (Cambridge, UK). The first-strand cDNA synthesis kit was purchased from Dakara Korea Biomedical, Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea). 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), propidium iodide (PI), crystal violet, and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise specified.

Cell culture

H1299, H460, A549, H226B, and BEAS-2B cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) or kindly provided by Dr. John V. Heymach (The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells were kindly provided by Dr. Jeong Hun Kim (College of Medicine, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea). Murine hippocampal neuronal cell line HT-22 was kindly provided by Dr. Dong Gyu Jo (College of Pharmacy, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon, Republic of Korea). Human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells were kindly provided by Dr. John Minna (The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA). H1299/PmR, H1299/CsR, and H226B/PcR cells were generated by continuous exposure to increasing concentrations of pemetrexed (for PmR), cisplatin (for CsR), or paclitaxel (for PcR) for more than 6 months25. All NSCLC cell lines were authenticated and validated. NSCLC cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (all from Welgene Inc., Gyeongssan-si, Republic of Korea). RPE and HT-22 cells were cultured in DMEM (Welgene) supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. HBE and BEAS-2B cells were cultured in Keratinocyte-SFM (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 5 ng/ml recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF), 50 μg/ml bovine pituitary extracts, and antibiotics. HUVECs were grown in VascuLife basal medium supplemented with VascuLife VEGF life factors (Lifeline Cell Technology, Frederick, MD, USA). Cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere.

MTT assay

Cells [2 × 103 cells/well (for NSCLC and HT-22 cells) or 3 × 103 cells/well (for HBE, BEAS-2B, RPE, and HUVEC) in 96-well plates] were treated with increasing concentrations of NCT-50, deguelin, ganetespib, or PU-H71 (0.1, 1, and 10 μM) for 2 or 3 days. After incubation, the cells were incubated with MTT solution (final concentration of 200 μg/ml) and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The formazan products were dissolved in DMSO, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm. The data are presented as a percentage of the control group.

Anchorage-dependent and anchorage-independent colony formation

For the anchorage-dependent colony formation assay, cells were plated at a density of 300 cells/well in six-well plates and were treated with increasing concentrations of NCT-50 for 2 weeks. Colonies were fixed with 100% methanol, stained with 0.02% crystal violet solution at room temperature, photographed, and counted.

For the anchorage-independent colony formation assay, cells were mixed with sterile 1% agar solution (final concentration of 0.4%) and then poured onto the 1% base agar in 12- or 24-well plates. After solidification, NCT-50 diluted in complete medium was added to the agar and incubated for 2 weeks. Colonies were stained with the MTT solution, photographed, and counted.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were treated with 0, 1, and 5 μM NCT-50 for three days. All adherent or floating cells were collected and washed with PBS. Cells were fixed with 100% methanol and stained with 50 μg/ml PI solution containing 50 μg/ml RNase A for 30 min at room temperature. Changes in the cell cycle distribution by NCT-50 treatment were determined by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur® flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Annexin V/PI double staining

Cells were plated into a 6-well plate at a density of 1.2 × 105 cells (for H1299 cells) or 1.5 × 105 cells (for H460) and incubated for 24 h. Cells were treated with vehicle or NCT-50 (1 or 5 μM) for additional two days. Cells were harvested by trypsinization, stained with Annexin V-FITC or PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry according to the manufacturer’s recommended procedure (BD Biosciences).

Tube formation assay

NSCLC cells were treated with NCT-50 for 24 h. Then, cell media were exchanged with fresh serum-free media. Conditioned media (CM) were collected 24 h after incubation. A 96-well plate was coated with growth factor reduced Matrigel (Corning, Corning, NY, USA). Then, HUVECs were seeded at a 104 cells/well density. For CM treated groups, each CM were mixed (1:1) with VasCulife media with 0.4% FBS. After 18 h, tube formation was analyzed under a microscope.

Nuclear morphology analysis

H1299 and H460 cells were treated with different dose of NCT-50 for 36 h. After treatment, the cells were incubated with Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) diluted in fresh serum containing media (20 μM) for 30 min, then observed under fluorescent microscope to survey condensed, fragmented or degraded nuclei in each cell and counted.

Western blot analysis

Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of NCT-50 (0, 1, and 5 μM) for 24 h. When necessary, the cells were further incubated under hypoxic conditions (1% O2 for 4 h). The cells were harvested with RIPA lysis buffer as described previously18. Equal amounts of cell lysates were resolved by 8–15% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked with blocking buffer [3% skim milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST)] for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies diluted in TBST containing 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed three times with TBST for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies diluted in 3% skim milk in TBST (1:5000) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were washed three times with TBST and visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Real-time PCR

Cells were treated with various concentrations of NCT-50 for 24 h and then harvested. Total RNA was prepared using an easy-BLUE total RNA extraction kit (Intron Biotechnology, Sungnam-si, Kyunggi-do, Republic of Korea) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. We performed a SYBR Green-based real-time PCR analysis according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (Bioneer Corp., Daejeon, Republic of Korea). The primer sequences used for real-time PCR are as follows: human vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) forward, 5′-CTT GCC TTG CTG CTC TAC C-3′; human VEGF reverse, 5′-CAC ACA GGA TGG CTT GAA G-3′; human transforming growth factor beta 3 (TGFB3) forward, 5′-TCT CCC AGA TCG GTG ACA GT-3′; human TGFB3 reverse, 5′-TGT CGG AAG TCA ATG TAG AG-3′; human platelet derived growth factor (PDGFB) forward, 5′- TTT CTC ACC TGG ACA GG CG-3′; human PDGFB reverse, 5′-GAA GGA GCC TGG GTT CCC T-3′; human DDIT3 forward, 5′- GGA GCA TCA GTC CCC CAC TT-3; human DDIT3 reverse, 5′- TGT GGG ATT GAG GGT CAC ATC-3; human PPP1R15A forward, 5′- CCC AGA AAC CCC TAC TCA TGA TC -3; human PPP1R15A reverse, 5′- GCC CAG ACA GCC AGG AAA T -3; human TRIB3 forward, 5′- TGC GTG ATC TCA AGC TGT GT -3; human TRIB3 reverse, 5′- GCT TGT CCC ACA GGG AAT CA -3; human ACTB forward, 5′- GCG AGA AGA TGA CCC AGA TC-3′; human ACTB reverse, 5′-GAT CCA CAT CTG CTG GAA-3′. The thermocycler conditions for real-time PCR were as follows: pre-incubation at 95 °C for 5 min, 30–40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 sec, 60 °C for 10 sec, and 72 °C for 10 sec, and melting curve analysis was performed to determine reaction specificity. Relative quantification of mRNA expression was performed by the comparative CT (cycle threshold) method as described previously63.

NADH dehydrogenase activity assay

NADH dehydrogenase activity assay was performed according to the previously reports with some modifications64,65. Confluent H460 cells in 100 mm culture dishes were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and harvested by scraping in PBS. After centrifugation, cell pellets were suspended in 1 ml ice-cold 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4) and mechanistically disrupted by sonication using Vibra-cell ultrasonic processor (Sonics & Materials Inc., Newtown, CT, USA). After adding 0.2 ml ice-cold 1.5 M sucrose, the suspension was centrifuged at 600 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were further centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C.Pellets were suspended in 100 μl 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4). Protein concentration was determined using BCA assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A mitochondria enriched fraction (20 μl, containing 20 μg of protein) was incubated with 960 μl of the incubation mixture containing 25 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.8), 3.5 g/L fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), 60 μM 2,6-dichloroindophenol, 70 μM decylubiquinone, and 1 μM antimycin A for 1 min at room temperature. The mixture was treated with vehicle or test compounds (5 μM NCT-50 or deguelin). After measuring the absorbance at 600 nm, 20 μl of 10 mM NADH solution was added, and the absorbance was monitored at 1 min intervals for 10 min. Enzyme activity of the test group was calculated according to the following formula and expressed as a percentage of the vehicle-treated control group; enzyme activity (nmol/min/mg) = (Δ Absorbance/min × 1,000)/[(extinction coefficient of DCIP × volume of sample used in 1 ml) × (sample protein concentration in mg/ml)]65. Extinction coefficient of DCIP was 19.1 mM−1cm−1 64,65.

Immunoprecipitation and pull-down assay

Immunoprecipitation, the purification of Hsp90 proteins, and a pull-down assay to determine the competitive binding to the ATP-binding pocket using ATP-agarose were performed according to our previous report18.

In vivo toxicity test

Animal experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Seoul National University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were fed standard mouse chow and water ad libitum and housed in temperature- and humidity-controlled facilities with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. 6-weeks-old FVB mice were treated with vehicle (10% DMSO in corn oil) or test compounds (deguelin or NCT-50, 4 mg/kg) twice a day for 7 consecutive days. Body weight changes were monitored during the treatment. In vivo toxicity test was perform as described previously66. Briefly, blood was collected from euthanized mice by cardiac puncture. Serum was collected by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The level of GOT, GPT, and BUN in the serum was analyzed using a veterinary hematology analyzer (Fuji DRI-Chem 3500 s, Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s recommended procedure. The histopathological changes in liver, lung, brain, and kidney were evaluated by using H&E-stained section of the tissues.

Immunofluorescence

Frozen sections of the mouse midbrain were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. After washing twice with PBS for 5 min each, sections were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 solution for 15 min at room temperature. Sections were washed three times with PBS for 5 min each. Sections were blocked with blocking buffer (3% BSA solution containing 10% normal donkey serum) for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated with anti-tyrosine hydroxylase primary antibody (EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA; 1:200 dilution) for overnight at 4 °C. Slides were washed three times with PBS for 10 min each at room temperature. Slides were further incubated with corresponding Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 1:500 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were washed six times with PBS for 10 min each and then mounted with mounting medium with DAPI. Images were acquired with a confocal microscope (LSM 700; Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany).

Docking modeling

All performances of computational works were carried out on the Tripos Sybyl-X 2.1 (Tripos Inc, St Louis, MO, USA) molecular modeling package.

Preparation of ligands

The ligands were prepared as Mol2 format using sketch modules embedded in Sybyl. Gasteiger-Hückel charges were assigned to all ligands atoms. Each ligand was energy-minimized using a standard Tripos force field with convergence to maximum derivatives of 0.001 kcal mol-1.Å-1.

Homology modeling of open conformation of hHsp90 homodimer

We conducted the homology modeling of full-length of human Hsp90α by using ORCHESTRAR module. It was reported that the function of Hsp90 C-terminal inhibitors was related with binding to the open form of homodimer Hsp90 structure67. Based on this information, we built up an open conformation of human Hsp90 dimer based on the extended SAXS model of E. coli Hsp90 homodimer including N-, middle and C-terminal domain. The template structure was retrieved from Agard’ lab website (http://www.msg.ucsf.edu/agard, PDB id: hsp90). The sequence identity of Hsp90 between E-coli and human is 42.9%. First, alignment file was defined using complete partial model. Then, based on this alignment file, structurally conserved regions (SCRs) were built automatically, and structurally variable region was identified. SCRs including loops were optimized by loop-search option. Side chains of amino acids were fixed with set side chain option. To remove the bad contacts in the protein structure, the brief energy-minimization of model was performed with assigning Kollman all charges to all the atoms of protein and convergence to maximum derivatives of 0.05 kcal mol-1.Å-1.

Molecular docking

The compound NCT-50 was docked into the active site of hHsp90 homology model structure using Surflex-Dock algorithm. The active site was defined by generating a protomol based on the ATP- binding pocket of the C-terminal domain. The protomol was built using the hydrogen-containing protein mol2 file with optimized parameters (threshold factor of 0.4 Å and bloat of 1 Å). Docking was performed with setting default parameters and 20 maximum ligand conformers to generate. Binding affinity of each docking pose of ligand was calculated by Surflex-Dock score (-log Kd). Based on the docking score and visual inspection, top-ranked docking model was selected.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± SD. The statistical significance was determined using a two-sided Student’s t-test using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The IC50 values were determined by non-linear regression analysis using Graphpad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). A P value less than 0.05 was statistically significant.

Synthesis of NCT-50

General Methods

All chemical reagents were commercially available. Melting points were determined on a melting point Buchi B-540 apparatus. Silica gel column chromatography was performed on silica gel 60, 230–400 mesh, Merck. 1H-NMR analyses were recorded on a JEOL JNM-LA 300 at 300 MHz. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm units with Me4Si as a reference standard. Mass spectra were recorded on a VG Trio-2 GC−MS instrument and a 6460 Triple Quad LC−MS instrument. All final compounds were assessed for purity by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on Agilent 1120 Compact LC (G4288A) system via the following conditions: column: Agilent TC-C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm). Mobile phase A: 0.1% TFA water. Mobile phase B: 0.1% TFA MeOH (50:50, v/v). Wavelength: 254 nM. Flow: 0.50 mL/min.

2-(Pyridin-4-yl)ethan-1-ol (2)

To a cooled solution of ethyl 2-(pyridin-4-yl)acetate (1, 200 mg, 1.21 mmol) in THF (6 mL) at 0 °C, lithium aluminium hydride (92 mg, 2.42 mmol) was added portionwise. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and monitored by TLC. Upon completion, the reaction was terminated by adding H2O. The organic layer was extracted with CH2Cl2, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (CH2Cl2/CH3OH, 20:1) to give 2 as a yellow oil (110 mg, 74%). 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.47 (dd, 2 H, J = 4.38, 1.65 Hz, H2, H6-pyridine), 7.15 (dd, 2 H, J = 4.38, 1.65 Hz, H3, H5-pyridine), 3.89 (t, 2 H, J = 6.42 Hz, -CH2CH2OH), 2.84 (t, 2 H, J = 6.42 Hz, -CH2CH2OH).

4-(2-(2-Methoxy-4-nitrophenoxy)ethyl)pyridine (3)

To a cooled solution of 2 (110 mg, 0.89 mmol), 4-nitroguaiacol (227.26 mg, 1.34 mmol) and triphenylphosphine (352.6 mg, 1.34 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (20 mL) at 0 °C, diethyl azodicarboxylate (0.6 mL, 1.34 mmol, 40% solution in toluene) was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at ambient temperature. Upon completion, the reaction was terminated by adding H2O. The organic layer was extracted with CH2Cl2, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (CH2Cl2/CH3OH, 20:1) to give 3 as a yellow solid (66 mg, 26%). 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.53 (dd, 2 H, J = 4.38, 1.65 Hz, H2,H6-pyridine), 7.86 (dd, 1 H, J = 8.97, 2.55 Hz, H5-benzene), 7.73 (d, 1 H, J = 2.55 Hz, H3-benzene), 7.22 (dd, 2 H, J = 4.38, 1.65 Hz, H3,H5-pyridine), 6.86 (d, 1 H, J = 8.97 Hz, H6-benzene), 4.30 (t, 2 H, J = 6.78 Hz, -CH2CH2O-), 3.92 (s, 3 H, CH3O-), 3.17 (t, 2 H, J = 6.78 Hz, -CH2CH2O-).

3-Methoxy-4-(2-(pyridin-4-yl)ethoxy)aniline (4)

A mixture of 3 (65.96 mg, 0.24 mmol) and 10% Pd/C (6 mg) in CH3OH (5 mL) was hydrogenated under a balloon of hydrogen for 2 h. The reaction mixture was filtered over Celite and the combined filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (CH2Cl2/CH3OH, 10:1) to give 4 as a brown solid (49.1 mg, 84%). 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.50 (dd, 2 H, J = 4.41, 1.65 Hz, H2, H6-pyridine), 7.21 (dd, 2 H, J = 4.41, 1.65 Hz, H3, H5-pyridine), 6.67 (d, 1 H, J = 8.43 Hz, H5-benzene), 6.27 (d, 1 H, J = 2.55 Hz, H2-benzene), 6.17 (dd, 1 H, J = 8.43, J = 2.58 Hz, H6-benzene), 4.13 (t, 2 H, J = 6.96 Hz, -CH2CH2O-), 3.77 (s, 3 H, CH3O-), 3.49 (br, 2 H, -NH2), 3.05 (t, 2 H, J = 6.78 Hz, -CH2CH2O-).

5-Hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-2H-chromene-6-carbaldehyde (6)

To a stirred solution of 2,4-dihydroxybenzaldehye (5, 5.53 g, 40 mmol) in pyridine (50 ml), 3-methylbutenal (2 mL, 20 mmol) was added and then the reaction mixture was refluxed for 15 h. Upon completion, the reaction was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and quenched with 1 N HCl. The organic layer was extracted with EtOAc, dried over MgSO4, concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc, 1:1) to give 6 as yellow solid (1.35 g, 32%). 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.62 (s, 1 H, OH), 9.63 (s, 1 H, -CHO), 7.26 (d, 1 H, J = 8.43 Hz, H7-chromene), 6.66 (d, 1 H, J = 10.05 Hz, H4-chromene), 6.40 (dd, 1 H J = 8.61, 0.72 Hz, H8-chromene), 5.58 (d, 1 H, 10.08 Hz, H3-chromene), 1.49 (s, 6 H, -(CH3)2).

5-Methoxy-2,2-dimethyl-2H-chromene-6-carbaldehyde (7)

To a stirred solution of 6 (1.35 g, 6.6 mmol) in DMF (50 mL), potassium carbonate (3.69 g, 26.7 mmol) followed by iodomethane (1.24 mL, 19.9 mmol) was added and then the reaction mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 h. Upon completion, the reaction was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and quenched with H2O and extracted with EtOAc, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc, 1:1) to give 7 as a brown oil (1.05 g, 72%). 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.15 (s, 1 H, -CHO), 7.63 (d, 1 H, J = 8.58 Hz, H7-chromene), 6.62 (d, 1 H, J = 8.61 Hz, H4-chromene), 6.57 (d, 1 H, J = 10.08 Hz, H8-chromene), 5.67 (d, 1 H, J = 10.08, H3-chromene), 3.88 (s, 3 H, CH3O-), 1.44 (s, 6 H, -(CH3)2).

5-Methoxy-2,2-dimethyl-2H-chromene-6-carboxylic acid (8)

To a stirred solution of 7 (1.05 g, 4.81 mmol), NaH2PO4 (114 mg, 0.95 mmol), 30% H2O2 (1.82 mL, 4.81 mmol) in Acetonitrile (50 mL) at room temperature, NaClO2 (652.8 mg, 7.22 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was extracted with EtOAc, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc, 1:1) to give 8 as yellow solid (710.8 mg, 63%). 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.89 (d, 1 H, J = 8.79 Hz, H7-chromene), 6.68 (dd, 1 H, J = 8.79, 0.72 Hz, H4-chromene), 6.52 (dd, 1 H, J = 10.05, 0.54 Hz, H8-chromene), 5.72 (d, 1 H, J = 9.87 Hz, H3-chromene), 3.93 (s, 3 H, CH3O-), 1.45 (s, 6 H, -(CH3)2).

5-Methoxy-N-(3-methoxy-4-(2-(pyridin-4-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)-2,2-dimethyl-2H-chromene-6-carboxamide (9)

To a stirred solution of 4 (48.8 mg, 0.2 mmol), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (57.5 mg, 0.3 mmol), hydroxybenzotriazole (40.6 mg, 0.3 mmol) and triethylamine (0.07 mL, 0.5 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (20 mL), 8 (47.1 mg, 0.2 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) was added and the reaction mixture was refluxed for 15 h. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was extracted with EtOAc, dried over Mg2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc, 1:1) to give 9 as a brown solid (71.2 mg, 77%). Anal. HPLC 99% (Rt = 4.5 min), mp = 112–118 °C, 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.61 (s, 1 H, -CNHCO-), 8.51 (dd, 2 H, J = 4.38, 1.65 Hz, H2, H6-pyridine), 7.93 (d, 1 H, J = 8.79 Hz, H7-chromene), 7.62 (d, 1 H, J = 2.37 Hz, H2-benzene), 7.23 (dd, 2 H, J = 4.38, 1.65 Hz, H2, H5-pyridine), 6.89 (dd, 1 H, J = 8.61, 2.37 Hz, H6-benzene), 6.80 (d, 1 H, J = 8.43 Hz, H8-chromene), 6.70 (d, 1 H, J = 8.61 Hz, H5-benzene), 6.57 (d, 1 H, J = 9.90 Hz, H4-chromene), 5.71 (d, 1 H, J = 10.08 Hz, H3-chromene), 4.22 (t, 2 H, J = 6.78 Hz, -CH2CH2O-), 3.88 (s, 3 H, CH3O-), 3.58 (s, 3 H, CH3O-), 3.11 (t, 2 H, J = 6.78 Hz, -CH2CH2O-), 1.44 (s, 6 H, -(CH3)2). HRMS (ESI) calc. for C27H28N2O5 [M + H]+ 461.2071, found 461.2064.

Ethical approval and informed consent

Animal experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Seoul National University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee..

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), Republic of Korea (No. NRF-2016R1A3B1908631) and the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (No. 1520250).

Author Contributions

S.Y.H., H.T.L., Y.S.Y., J.S.L. and H.Y.M. performed in vitro experiments and analyzed the data. S.Y.H. and H.J.L. performed in vivo toxicity test. H.J.B. performed immunofluorescence analysis of the mouse midbrain sections. C.T.L., J.A. and J.L. conducted or contributed to synthesis of NCT-50. J.C. and H.J.P. carried out docking modeling. H.Y.M. wrote the manuscript. H.Y.L. conceived and designed this study and wrote the manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Seung Yeob Hyun, Huong Thuy Le and Cong-Truong Nguyen contributed equally.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-32196-6.

References

- 1.Trepel J, Mollapour M, Giaccone G, Neckers L. Targeting the dynamic HSP90 complex in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:537–549. doi: 10.1038/nrc2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitesell L, Lindquist SL. HSP90 and the chaperoning of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:761–772. doi: 10.1038/nrc1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu W, Neckers L. Targeting the molecular chaperone heat shock protein 90 provides a multifaceted effect on diverse cell signaling pathways of cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1625–1629. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Carbonero R, Carnero A, Paz-Ares L. Inhibition of HSP90 molecular chaperones: moving into the clinic. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e358–369. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dobbelstein M, Moll U. Targeting tumour-supportive cellular machineries in anticancer drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:179–196. doi: 10.1038/nrd4201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma SV, Bell DW, Settleman J, Haber DA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:169–181. doi: 10.1038/nrc2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CK, et al. Impact of EGFR inhibitor in non-small cell lung cancer on progression-free and overall survival: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:595–605. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J Nat Prod. 2012;75:311–335. doi: 10.1021/np200906s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chun KH, et al. Effects of deguelin on the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway and apoptosis in premalignant human bronchial epithelial cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:291–302. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suh YA, et al. A novel antitumor activity of deguelin targeting the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor pathway via up-regulation of IGF-binding protein-3 expression in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013;332:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H, Lee JH, Jung KH, Hong SS. Deguelin promotes apoptosis and inhibits angiogenesis of gastric cancer. Oncol Rep. 2010;24:957–963. doi: 10.3892/or.2010.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee HY, et al. Chemopreventive effects of deguelin, a novel Akt inhibitor, on tobacco-induced lung tumorigenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1695–1699. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim WY, et al. A novel derivative of the natural agent deguelin for cancer chemoprevention and therapy. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2008;1:577–587. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woo JK, et al. Liposomal encapsulation of deguelin: evidence for enhanced antitumor activity in tobacco carcinogen-induced and oncogenic K-ras-induced lung tumorigenesis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:361–369. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh SH, et al. Structural basis for depletion of heat shock protein 90 client proteins by deguelin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:949–961. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caboni P, et al. Rotenone, deguelin, their metabolites, and the rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:1540–1548. doi: 10.1021/tx049867r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcu MG, Schulte TW, Neckers L. Novobiocin and related coumarins and depletion of heat shock protein 90-dependent signaling proteins. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:242–248. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allan RK, Mok D, Ward BK, Ratajczak T. Modulation of chaperone function and cochaperone interaction by novobiocin in the C-terminal domain of Hsp90: evidence that coumarin antibiotics disrupt Hsp90 dimerization. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7161–7171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcu MG, Chadli A, Bouhouche I, Catelli M, Neckers LM. The heat shock protein 90 antagonist novobiocin interacts with a previously unrecognized ATP-binding domain in the carboxyl terminus of the chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37181–37186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SC, et al. Synthesis and Evaluation of a Novel Deguelin Derivative, L80, which Disrupts ATP Binding to the C-terminal Domain of Heat Shock Protein 90. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;88:245–255. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.096883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HS, et al. Ring-truncated deguelin derivatives as potent Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1alpha (HIF-1alpha) inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;104:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SC, et al. Deguelin Analogue SH-1242 Inhibits Hsp90 Activity and Exerts Potent Anticancer Efficacy with Limited Neurotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2016;76:686–699. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim HS, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of C-ring truncated deguelin derivatives as heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2016;24:6082–6093. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang DJ, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel deguelin-based heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) inhibitors targeting proliferation and angiogenesis. J Med Chem. 2012;55:10863–10884. doi: 10.1021/jm301488q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burlison JA, et al. Development of Novobiocin Analogues That Manifest Anti-proliferative Activity against Several Cancer Cell Lines. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2008;73:2130–2137. doi: 10.1021/jo702191a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD, Schild SE, Adjei AA. Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:584–594. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60735-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao H, et al. Engineering an antibiotic to fight cancer: optimization of the novobiocin scaffold to produce anti-proliferative agents. J Med Chem. 2011;54:3839–3853. doi: 10.1021/jm200148p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hendriks LEL, Dingemans AC. Heat shock protein antagonists in early stage clinical trials for NSCLC. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26:541–550. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2017.1302428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Speranza G, et al. First-in-human study of the epichaperome inhibitor PU-H71: clinical results and metabolic profile. Invest New Drugs. 2018;36:230–239. doi: 10.1007/s10637-017-0495-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saraste A, Pulkki K. Morphologic and biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis. Cardiovascular Research. 2000;45:528–537. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neckers L, Workman P. Hsp90 molecular chaperone inhibitors: are we there yet? Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:64–76. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnston DE. Special considerations in interpreting liver function tests. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:2223–2230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salazar JH. Overview of Urea and Creatinine. Laboratory Medicine. 2014;45:e19–e20. doi: 10.1309/LM920SBNZPJRJGUT. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daubner SC, Le T, Wang S. Tyrosine hydroxylase and regulation of dopamine synthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;508:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White RB, Thomas MG. Moving beyond tyrosine hydroxylase to define dopaminergic neurons for use in cell replacement therapies for Parkinson’s disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2012;11:340–349. doi: 10.2174/187152712800792758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scaltriti M, Dawood S, Cortes J. Molecular pathways: targeting hsp90–who benefits and who does not. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4508–4513. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Semenza GL. Hydroxylation of HIF-1: oxygen sensing at the molecular level. Physiology (Bethesda) 2004;19:176–182. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00001.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koditz J, et al. Oxygen-dependent ATF-4 stability is mediated by the PHD3 oxygen sensor. Blood. 2007;110:3610–3617. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-094441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marciniak SJ, et al. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3066–3077. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wennemers M, et al. Tribbles homolog 3 denotes a poor prognosis in breast cancer and is involved in hypoxia response. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R82. doi: 10.1186/bcr2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia: role of the HIF system. Nat Med. 2003;9:677–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jo DH, et al. Hypoxia-mediated retinal neovascularization and vascular leakage in diabetic retina is suppressed by HIF-1alpha destabilization by SH-1242 and SH-1280, novel hsp90 inhibitors. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oh SH, et al. Identification of novel antiangiogenic anticancer activities of deguelin targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:5–14. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodwin AM. In vitro assays of angiogenesis for assessment of angiogenic and anti-angiogenic agents. Microvasc Res. 2007;74:172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tonini T, Rossi F, Claudio PP. Molecular basis of angiogenesis and cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22:6549–6556. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karagöz GE, Rüdiger SGD. Hsp90 interaction with clients. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2015;40:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taipale M, Jarosz DF, Lindquist S. HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: emerging mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:515–528. doi: 10.1038/nrm2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sgobba M, Degliesposti G, Ferrari AM, Rastelli G. Structural models and binding site prediction of the C-terminal domain of human Hsp90: a new target for anticancer drugs. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2008;71:420–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bagatell R, Whitesell L. Altered Hsp90 function in cancer: a unique therapeutic opportunity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1021–1030. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.10.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimamura T, Shapiro GI. Heat shock protein 90 inhibition in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:S152–159. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318174ea3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solar P, et al. Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin increases the sensitivity of resistant ovarian adenocarcinoma cell line A2780cis to cisplatin. Neoplasma. 2007;54:127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sawai A, et al. Inhibition of Hsp90 down-regulates mutant epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression and sensitizes EGFR mutant tumors to paclitaxel. Cancer Res. 2008;68:589–596. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bao R, et al. Targeting heat shock protein 90 with CUDC-305 overcomes erlotinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:3296–3306. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wainberg ZA, et al. Inhibition of HSP90 with AUY922 induces synergy in HER2-amplified trastuzumab-resistant breast and gastric cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:509–519. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jhaveri K, Taldone T, Modi S, Chiosis G. Advances in the clinical development of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) inhibitors in cancers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:742–755. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nishida N, Yano H, Nishida T, Kamura T, Kojiro M. Angiogenesis in cancer. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2006;2:213–219. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2006.2.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramalingam S, Belani CP. Paclitaxel for non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:1771–1780. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.8.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson DH, Schiller JH, Bunn PA., Jr. Recent clinical advances in lung cancer management. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:973–982. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Soti C, Racz A, Csermely P. A Nucleotide-dependent molecular switch controls ATP binding at the C-terminal domain of Hsp90. N-terminal nucleotide binding unmasks a C-terminal binding pocket. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7066–7075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T)(-Delta Delta C) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Janssen AJ, et al. Spectrophotometric assay for complex I of the respiratory chain in tissue samples and cultured fibroblasts. Clin Chem. 2007;53:729–734. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.078873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pollard AK, Craig EL, Chakrabarti L. Mitochondrial Complex 1 Activity Measured by Spectrophotometry Is Reduced across All Brain Regions in Ageing and More Specifically in Neurodegeneration. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee HJ, et al. Development of a 4-aminopyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine-based dual IGF1R/Src inhibitor as a novel anticancer agent with minimal toxicity. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:50. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0802-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sgobba M, Forestiero R, Degliesposti G, Rastelli G. Exploring the binding site of C-terminal hsp90 inhibitors. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50:1522–1528. doi: 10.1021/ci1001857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article