Abstract

Proteins in the RAS family are important regulators of cellular signaling and, when mutated, can drive cancer pathogenesis. Despite considerable effort over the last 30 years, RAS proteins have proven to be recalcitrant therapeutic targets. One approach for modulating RAS signaling is to target proteins that interact with RAS, such as the guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) son of sevenless homologue 1 (SOS1). Here, we report hit-to-lead studies on quinazoline-containing compounds that bind to SOS1 and activate nucleotide exchange on RAS. Using structure-based design, we refined the substituents attached to the quinazoline nucleus and built in additional interactions not present in the initial HTS hit. Optimized compounds activate nucleotide exchange at single-digit micromolar concentrations in vitro. In HeLa cells, these quinazolines increase the levels of RAS-GTP and cause signaling changes in the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK) pathway.

Keywords: RAS, SOS1, nucleotide exchange, structure-based design, quinazolines

The three RAS genes—HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS—constitute the most frequently mutated gene family in human cancers.1 With RAS mutations found in approximately one-third of all human tumors, these oncogenes represent important targets in the field of drug discovery.2,3RAS genes encode small GTP-binding proteins that function as molecular switches, transmitting extracellular stimuli to intracellular signaling pathways. Canonically, RAS proteins exist in two states: the guanosine diphosphate (GDP)-bound “off” state and the guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound “on” state.4,5 RAS activity is tightly governed by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) and guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs).6 Mutations in RAS genes can render the proteins that they encode constitutively active, and cells harboring mutated RAS proteins often display the hallmarks of cancer.7−9 To date, multiple strategies for targeting RAS have been developed, but each has been met with limited success.3,10−13

Our group has reported an approach for modulating RAS signaling that entails binding to and activating the protein son of sevenless homologue 1 (SOS1), a GEF that interacts directly with RAS and catalyzes the exchange of GDP for GTP.14−16 In these studies, we described compounds from an indole series that bind to the CDC25 domain of SOS1 in the RAS:SOS1:RAS complex, activate nucleotide exchange at submicromolar concentrations in vitro, increase the levels of RAS-GTP in cancer cells, and cause biphasic signaling changes in the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK) pathway. Here, we describe the discovery of another series of compounds, based on a quinazoline scaffold, that bind to the same pocket on SOS1, but in a different manner, which is characterized by the rotation of a Phe residue inside the binding pocket. Importantly, compounds exhibiting this alternative binding mode elicit similar effects in vitro and in cells as the previously reported indoles.

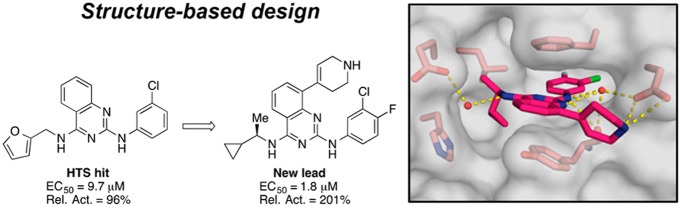

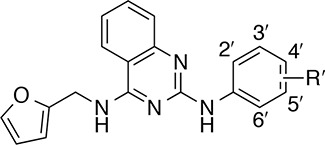

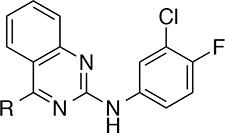

From a high throughput nucleotide exchange assay used to screen the Vanderbilt library of >160,000 compounds, 2,880 small molecules were identified that increased the rate of SOS1-mediated nucleotide exchange on RAS (1.8% initial hit rate).17 Among the hit molecules in the screen, the 2,4-diaminoquinazoline, 1, was identified for its ability to activate nucleotide exchange with similar efficacy as the positive control (Rel. Act. = 96%) and with good potency (EC50 = 9.7 μM) (Figure 1). An advantage of the quinazoline scaffold was the potential for rapid diversification. Indeed, the amine substituents at positions 2 and 4 could each be readily exchanged, and the carbon atoms of the quinazoline arene ring offered additional vectors into distinct areas of chemical space.

Figure 1.

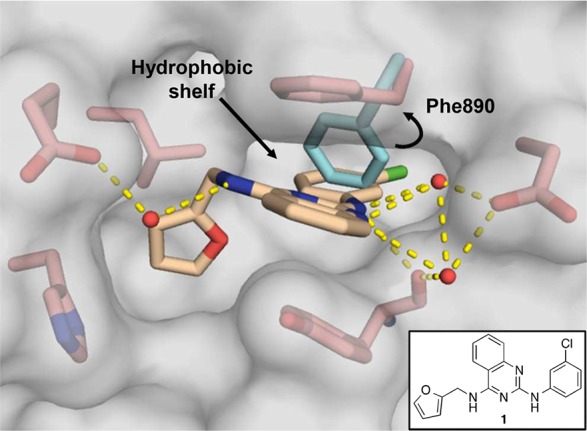

X-ray co-crystal structure of compound 1 (beige; PDB ID code 6CUO) bound to SOS1 in the RAS:SOS1:RAS ternary complex. SOS1 protein surface is shown in gray with key binding site residues displayed in pink. The alternative orientation of Phe890 is shown in cyan.

To guide the first round of compound synthesis, the binding mode of the HTS hit, 1, was identified by X-ray crystallography. As shown in the X-ray co-crystal structure depicted in Figure 1, compound 1 binds to a hydrophobic pocket on SOS1 in the RAS:SOS1:RAS complex. While this is the same binding site occupied by compounds in the indole series, the aromatic ring of Phe890 is flipped approximately 90° relative to its position in the co-crystal structures obtained with the indole compounds.14,16 A similar rotation of this residue was also observed during a fragment screening campaign conducted by a group from AstraZeneca.18 This rotation unveiled a new hydrophobic shelf inside of the binding pocket that is partially occupied by the 3′-chloroaniline substituent on compound 1. This region of chemical space, which was unexplored by the compounds in the indole series, provided an excellent starting point for structure-based design.

In the X-ray co-crystal structure depicted in Figure 1, the space beneath Phe890—around the aniline ring of compound 1—appeared to be mainly hydrophobic in nature. Thus, lipophilic groups seemed to be well suited for this area of the binding pocket. For reference, the unsubstituted phenyl derivative, 2, was prepared and proved to be inactive (Table 1). Reintroduction of a lipophilic substituent at the 3′-position of the aniline ring restored activity, as in the 3′-methyl derivative, 3, and the 3′-bromo derivative, 4. Conversely, less lipophilic groups, such as the 3′-methoxy group in compound 5 and the 3′-(1-hydroxyethyl) group in compound 6 were not well tolerated.

Table 1. SAR of the Aniline Ringa.

| Compd | R′ | EC50 (μM)b | Rel. Act. (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3′-Cl | 9.7 ± 1.16 | 96 ± 13.9 |

| 2 | H | — | 47 ± 13.6 |

| 3 | 3′-Me | 16.4 ± 0.35 | 96 ± 2.1 |

| 4 | 3′-Br | 7.1 ± 1.93 | 87 ± 12.5 |

| 5 | 3′-OMe | — | 38 ± 8.5 |

| 6 | 3′-(1-hydroxyethyl) | — | 10 ± 4.8 |

| 7 | 4′-Me | — | 8 ± 1.4 |

| 8 | 4′-Br | — | 16 ± 4.0 |

| 9 | 4′-OMe | — | 19 ± 0.9 |

| 10 | 3′,4′-diMe | — | 37 ± 11.3 |

| 11 | 3′,5′-diMe | — | 44 ± 20.4 |

| 12 | 3′,4′-diCl | — | 22 ± 5.6 |

| 13 | 3′,5′-diCl | — | 41 ± 26.5 |

| 14 | 3′-Cl-4′-F | 13.1 ± 1.20 | 96 ± 10.6 |

Each value represents the mean ± SD of at least two separate experiments.

“—” denotes an EC50 value of >100 μM or an EC50 value that was not calculated due to low efficacy in vitro.

Having explored the 3′-position of the aniline ring, we next investigated alternative substitution patterns. Moving the substituent from the 3′-position to the 4′-position compromised both potency and efficacy in vitro—compare, for example, the 4′-methyl analogue, 7, and the 4′-bromo analogue, 8, with their respective 3′-regioisomers 3 and 4—suggesting that the 3′-substituent was important for compound activity. With this consideration in mind, several quinazolines featuring disubstituted aniline rings were then prepared. Appending a second substituent to either C-4′ or C-5′ of the aniline ring was detrimental to activity when this substituent was either methyl (10 and 11) or chloro (12 and 13). However, smaller atoms such as fluorine were well tolerated, as illustrated by compound 14, which was of similar potency and efficacy to 1. Being among the most potent and efficacious analogues in Table 1, compound 14 was identified as the scaffold upon which to build further SAR.

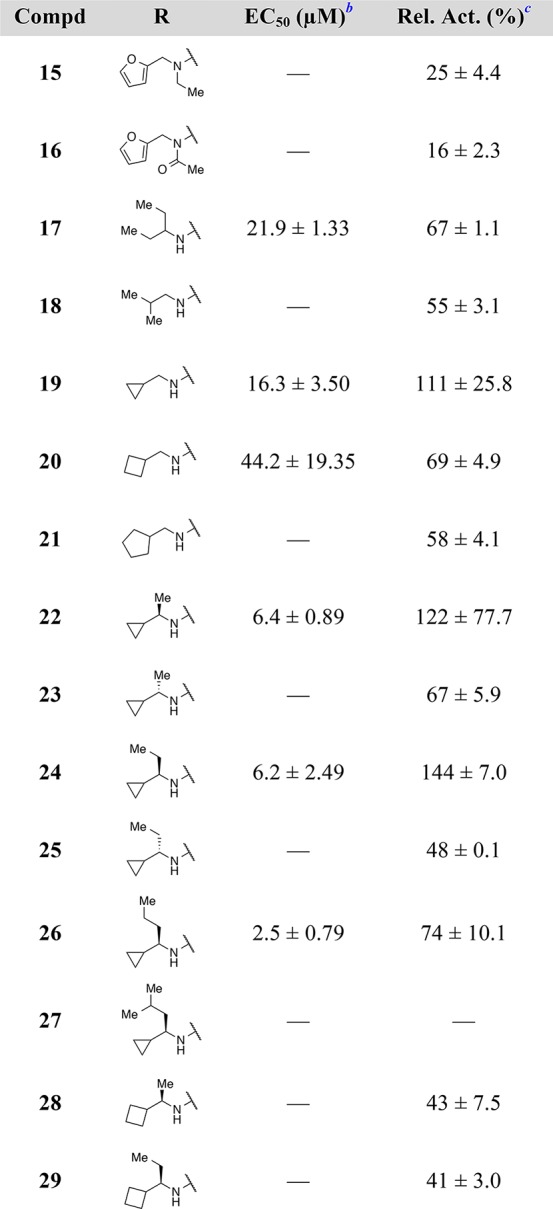

With adequate SAR established at the 2-position of the quinazoline scaffold, our focus shifted to filling the unoccupied space near the (aminomethyl)furan of the HTS hit, 1. The exocyclic nitrogen atom at the 4-position of the quinazoline appeared to offer a vector into this area of the binding pocket; however, in the X-ray co-crystal structure depicted in Figure 1, this nitrogen atom is solvent exposed and engaged in a water-mediated interaction with Glu902. It was not clear, a priori, whether substituents on this nitrogen atom would be tolerated. Thus, the N-ethyl analogue, 15, and the N-acetyl analogue, 16, were prepared (Table 2). Unfortunately, both of these analogues displayed low efficacy in the nucleotide exchange assay, which suggested that substituting this nitrogen atom would not be a viable design strategy.

Table 2. SAR of the Quinazoline 4-Positiona.

Each value represents the mean ± SD of at least two separate experiments.

“—” denotes an EC50 value of >100 μM or an EC50 value that was not calculated due to low efficacy in vitro.

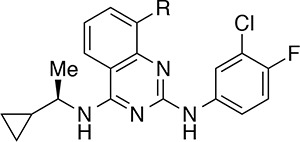

A more productive approach for increasing the occupancy of the binding pocket involved branching from the carbon atoms of the amine substituent. This strategy allowed us to introduce more sp3 character into these quinazoline compounds19 and provided an opportunity to move away from the furan moiety, a known metabolic liability.20,21 As illustrated in Table 2, promising results were obtained with α-branched amines, such as the pentan-3-amine featured in compound 17, and smaller cycloalkyl rings, such as the cyclopropyl group featured in compound 19. Further potency improvements were realized when these two design elements were combined, as in the (R)-1-cyclopropylethan-1-amine featured in compound 22, which activated the nucleotide exchange process at 122% relative to control, with an EC50 value of 6.4 μM. Remarkably, the (S)-enantiomer matched pair 23 demonstrated a large drop-off in exchange activity. To clarify the binding mode of the new lead compound 22, and to further guide structure-based design, the X-ray co-crystal structure of this compound bound to the RAS:SOS1:RAS complex was obtained.

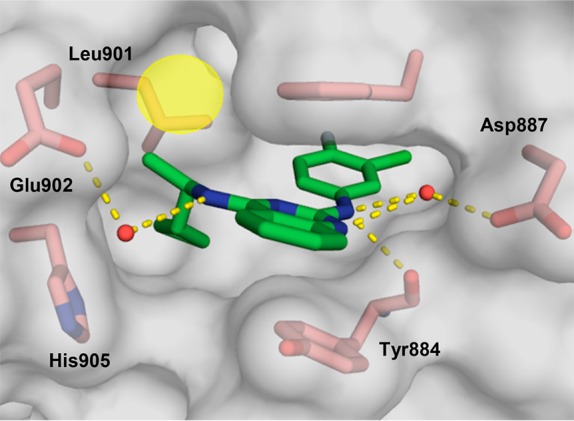

As shown in Figure 2, the cyclopropyl substituent of compound 22 sits behind His905 of SOS1, while the methyl branch partially fills the hydrophobic space near Leu901 (Figure 2, yellow circle). This arrangement is enforced by the (R)-configuration of the stereogenic carbon. Our analysis of this co-crystal structure further suggested that additional pocket occupancy could be achieved by extending the alkyl branch into the hydrophobic area near Leu901. Thus, several compounds were prepared to explore this region of chemical space. The preference for the (R)-enantiomer was confirmed with the ethyl derivatives, 24 and 25, but no marked improvement in activity was realized. While the propyl derivative, 26, was more potent than the methyl comparator, 22, a noticeable decrease in efficacy was observed, and further increasing the size of the alkyl branch, as with the isobutyl analogue, 27, ablated nucleotide exchange activity altogether. Decreases in activity were also observed as the size of the cycloalkyl substituent extended beyond cyclopropyl. This general trend is exemplified by the cyclobutyl analogues, 28 and 29, both of which were inactive.

Figure 2.

X-ray co-crystal structure of compound 22 (green; PDB ID code 6CUP) bound to SOS1 in the RAS:SOS1:RAS ternary complex. SOS1 protein surface is shown in gray with key binding site residues displayed in pink. Yellow circle indicates hydrophobic space near Leu901.

The X-ray co-crystal structure of compound 22 presented an additional avenue for further compound design. As shown in Figure 2, the exocyclic nitrogen at the 2-position of the quinazoline scaffold and the endocyclic N-1 ring nitrogen engage the carboxylate group of Asp887 through a molecule of water. During the AstraZeneca fragment screening campaign (vide supra), several ligands were also shown to interact directly with this Asp residue.18 Furthermore, whereas mutation of Asp887 did not affect the activity of our previously reported indole compounds,14 several of the HTS hits lost the ability to activate nucleotide exchange when tested with the Asp887Ala and Asp887His mutant forms of SOS1.22 Thus, we speculated that this residue could be leveraged to improve the activity of the compounds in this quinazoline series.

To this end, several 8-substituted quinazolines intended to directly engage Asp887 via a charge–charge interaction or a hydrogen bond were designed. For these studies, the (R)-1-cyclopropylethan-1-amine was retained at the 4-position of the quinazoline scaffold. The data for compounds 22 and 24 reported in Table 2 as well as data for other matched pairs (not shown) suggested that the methyl branch (e.g., 22) and the ethyl branch (e.g., 24) could be used to similar effect, and the commercial availability of the (R)-1-cyclopropylethan-1-amine made it a more attractive choice for subsequent rounds of compound synthesis.

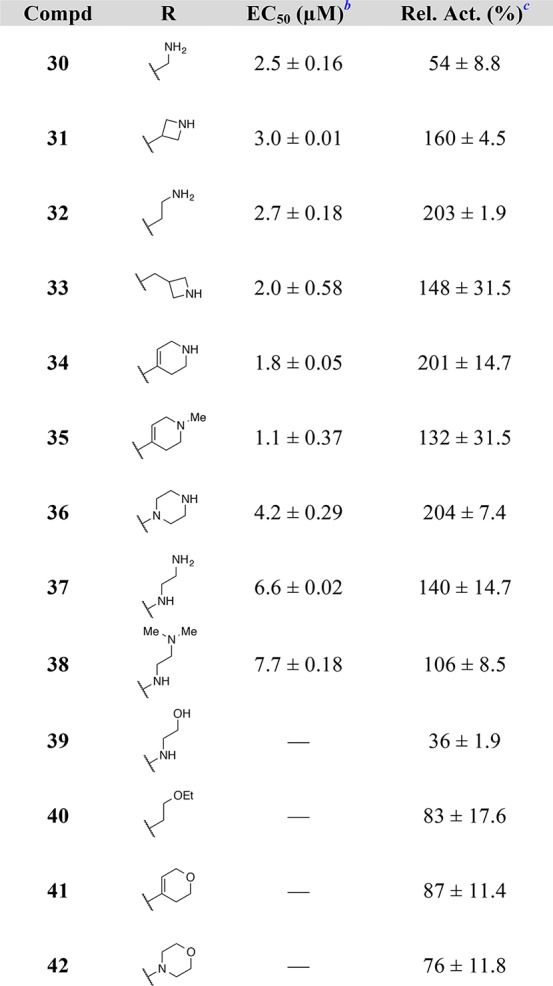

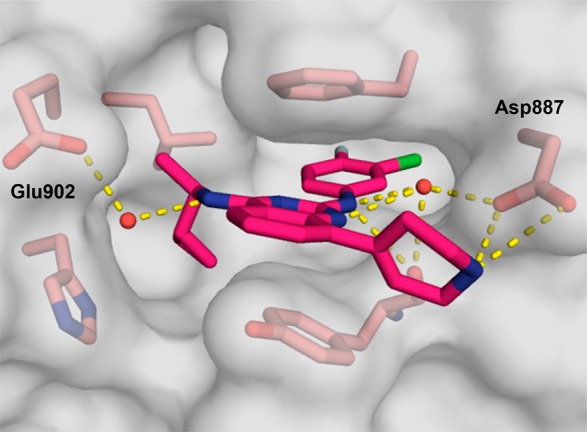

As the data in Table 3 illustrate, many of the 8-substituted quinazolines demonstrated improved potency and efficacy relative to the parent 8H-quinazoline, 22. In particular, analogues containing a substituent bearing an amino group performed especially well in the assay. The length of the tether connecting the amine to the quinazoline had a noticeable effect on compound activity. For example, 8-(aminomethyl)quinazoline 30 exhibited good potency but was less efficacious than the homologous 8-(aminoethyl)quinazoline 32. Cyclic amines were well tolerated (e.g., 34–36) as were acyclic amines (e.g., 32, 37, and 38). On the other hand, compounds featuring amino alcohols (e.g., 39) and ethers (e.g., 40–42) were essentially inactive, establishing a clear preference for amine-containing substituents that presumably engage in a charge–charge interaction with the carboxylate side chain of Asp887. To test this hypothesis, the X-ray co-crystal structure of compound 34 bound to SOS1 in the RAS:SOS1:RAS ternary complex was obtained (Figure 3). In the crystallized binding pose, the exocyclic nitrogen atom at the 4-position of the quinazoline nucleus interacts with Glu902 via a molecule of water. A second molecule of water bridges the exocylic amine at the 2-position and the endocylic N-1 nitrogen atom to Asp887. As designed, the secondary amine of the tetrahydropyridine moiety at the 8-position of the quinazoline interacts directly with the carboxylate side chain of Asp887 via a charge-assisted hydrogen bond.23−25 This additional interaction appears to improve both potency and efficacy in vitro, as evidenced by comparing the nucleotide exchange activity of compound 34 with that of the parent 8H-quinazoline, 22, and the dihydropyran analogue, 41.

Table 3. SAR of the Quinazoline 8-Positiona.

Each value represents the mean ± SD of at least two separate experiments.

“—” denotes an EC50 value of >100 μM or an EC50 value that was not calculated due to low efficacy in vitro.

Figure 3.

X-ray co-crystal structure of compound 34 (magenta; PDB ID code 6CUR) bound to SOS1 in the RAS:SOS1:RAS ternary complex. SOS1 protein surface is shown in gray with key binding site residues displayed in pink.

Having improved the biochemical activity of these quinazoline compounds using structure-based design, we sought to assess compound-mediated effects in HeLa cells. We have previously suggested that rapid and robust activation of RAS signaling to an intolerably high threshold may elicit anticancer effects.14−17 In our proposed biological mechanism, SOS1 agonist compounds induce (1) an increase in the levels of RAS-GTP and (2) biphasic modulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation, where increased levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2T202/Y204) are observed at lower compound concentrations and decreased levels of pERK1/2T202/Y204 are observed at higher concentrations. Mechanistically, inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation is achieved at higher treatment concentrations through negative feedback on SOS1 by pERK1/2T202/Y204.15−17

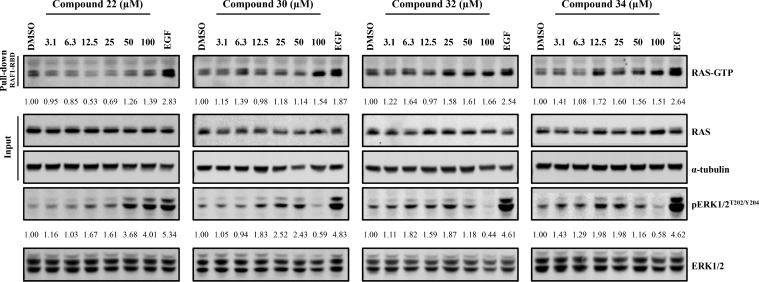

To test whether these quinazolines, which bind to SOS1 with Phe890 in a different conformation than was observed previously,14,16 elicit the same signaling changes in cells as our indole compounds, the effects of four exemplar compounds—22, 30, 32, and 34—were assessed by western blotting. The levels of endogenous cellular RAS-GTP were measured in response to compound treatment, along with the associated levels of pERK1/2T202/Y204 and the total ERK1/2 protein levels.

As shown in Figure 4, an increase in the levels of RAS-GTP was observed after treatment with compounds 32 and 34. Compound 30 elicited a small increase in RAS-GTP levels only at higher concentrations, consistent with its lower relative percent activation. All three of these compounds elicited the expected biphasic modulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. The cellular activity of quinazolines 30, 32, and 34 is thus consistent with that of the previously reported indoles14−16 and exemplifies the characteristic activity of our SOS1 agonist compounds. Together, these data suggest that the compounds from these two distinct chemical series, which demonstrate different binding modes to SOS1, likely act via the same biological mechanism. In contrast, compound 22 did not induce a marked increase in the levels of RAS-GTP at the concentrations tested. Despite this lack of RAS-GTP induction, a substantial increase in the levels of pERK1/2T202/Y204 was noted. The anticipated decrease in ERK1/2 phosphorylation at higher treatment concentrations, however, was not observed. The effects on pERK1/2T202/Y204 signaling elicited by five less active compounds—13, 25, 27, 28, and 29—were also measured and resemble the effects elicited by compound 22, namely, an increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation at higher compound concentrations (Figure S1).

Figure 4.

RAS-GTP and corresponding pERK1/2T202/Y204 levels from HeLa cells that were treated for 30 min with up to 100 μM of compound 22, 30, 32, or 34. EGF treatment (50 ng/mL for 5 min) was used as a positive control for pathway activation. Quantification values for RAS-GTP and pERK1/2T202/Y204 levels are displayed under the respective blots for each compound and are also provided in Table S1. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

At present, the discrepancy between RAS-GTP and pERK1/2T202/Y204 induction after treatment with compound 22 is not fully understood but may be indicative of either insufficient cellular potency or off-target effects resulting in pERK1/2T202/Y204 activation independent of RAS-GTP induction. It is notable that, although compound 22 was found to weakly inhibit ERK1/2 kinase activity (Table S3), this compound elicits enhanced pERK1/2T202/Y204 levels in cells.

In this Letter, an SAR study involving the structure-guided design and synthesis of a series of quinazolines is described. These molecules bind to SOS1 in the same pocket as the previously reported indoles, but in a distinctive manner, which is characterized by the rotation of Phe890. This rotation revealed a new area of chemical space and provided a starting point for the structure-based design of improved compounds. By exploring different substituents on the aniline ring at the 2-position of the quinazoline nucleus, optimizing the branched alkyl amine at the 4-position, and tethering an amino group to the 8-position, the overall nucleotide exchange activity of the initial HTS hit, 1, was improved. Lead compounds identified in the biochemical assay, 32 and 34, were tested in HeLa cells where they elicited an increase in the levels of RAS-GTP and caused biphasic changes in ERK1/2 phosphorylation. These new findings suggest that the preferred profile for a SOS1 agonist from this quinazoline series should include both a high Rel. Act. (approximately ≥50%) and a low EC50 (approximately ≤2.5 μM) to elicit potent activation of RAS and biphasic modulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in HeLa cells.

SOS1 agonist compounds from two distinct chemical series—indole and quinazoline—elicit the same biochemical and cellular effects that we propose are characteristic of SOS1 activation. In particular, the biphasic modulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation elicited by compounds from these two chemically unrelated series further illustrates and supports our recently proposed biological mechanism.15−17 Importantly, these studies show that compounds that bind to SOS1 with the Phe890 residue in the alternative conformation described here also activate nucleotide exchange. Based on our hypothesis that rapid and robust activation of RAS signaling may elicit anticancer effects, current efforts in this series are focused on improving compound potency in the biochemical and cellular assays, and on identifying potential sources of off-target activity. The goal of these future studies is to identify a tool compound that can be used to explore the in vivo consequences of modulating RAS signaling through SOS1 in cancer cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following core facilities for their contributions to this work: Experiments were performed in the Vanderbilt High Throughput Screening (HTS) Core Facility with assistance provided by C. David Weaver, Paige Vinson, Chris Farmer, and Corbin Whitwell. The HTS Core receives support from the Vanderbilt Institute of Chemical Biology and the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center (P30 CA68485). The Vanderbilt University Biomolecular NMR Facility for instrumentation. This facility receives support from an NIH SIG Grant (1S-10RR025677-01) and Vanderbilt University matching funds. The U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences for use of the Advanced Photon Source (Contract: DE-AC02-06CH11357). Funding for this work came from the following sources: U.S. National Institutes of Health, NIH Director’s Pioneer Award (DP1OD006933/DP1CA174419) to S.W.F. Lustgarten Foundation Research Investigator Grant to S.W.F. National Cancer Institute SPORE Grant in GI Cancer (5P50A095103–09) to R.J.C.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- ERK1/2

extracellular regulated kinases 1 and 2

- GAP

GTPase-activating protein

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- EC50

half maximal effective concentration

- HTS

high throughput screen/screening

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- pERK1/2

phosphorylated ERK1/2

- SOS1

son of sevenless homologue 1

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00296.

General experimental considerations, detailed experimental procedures, and characterization data for all new compounds; biochemical and cellular assay conditions; quantification tables for western blotting experiments; western blotting experiments involving compounds 13, 25, 27, 28, and 29; details regarding protein expression and purification; details regarding crystallization, X-ray data collection, structure solution, and refinement; a table containing X-ray data collection and refinement statistics; and a Reaction Biology Corp. kinase profiling report for compound 22 (PDF)

Accession Codes

Compound 1 (PDB ID code 6CUO), Compound 22 (PDB ID code 6CUP), and Compound 34 (PDB ID code 6CUR).

Author Present Address

∥ P.A.P.: PharmAgra Labs, Brevard, North Carolina 28712, United States.

Author Present Address

∇ J.P.K.: Truetiva, Inc., Monterey, California 93940, United States.

Author Present Address

⊥ M.C.B.: Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois 60208, United States.

Author Present Address

# C.F.B.: Wright Medical Group N.V., Franklin, Tennessee 37067, United States.

Author Present Address

¶ Q.S.: AbbVie, Inc., North Chicago, Illinois 60064, United States.

Author Present Address

○ O.W.R.: The Institute of Cancer Research, London SM2 5NG, U.K.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): RAS activator compounds have been licensed to Boehringer Ingelheim.

Supplementary Material

References

- Papke B.; Der C. J. Drugging RAS: Know the Enemy. Science 2017, 355 (6330), 1158–1163. 10.1126/science.aam7622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior I. A.; Lewis P. D.; Mattos C. A Comprehensive Survey of Ras Mutations in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2012, 72 (10), 2457–2467. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox A. D.; Fesik S. W.; Kimmelman A. C.; Luo J.; Der C. J. Drugging the Undruggable RAS: Mission Possible?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2014, 13 (11), 828–851. 10.1038/nrd4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulgar T. G. D.; Lacal J. C.. GTPase. In Encyclopedia of Cancer; Schwab M., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp 1609–1613. [Google Scholar]

- Cox A. D.; Der C. J. Ras History. Small GTPases 2010, 1 (1), 2–27. 10.4161/sgtp.1.1.12178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigil D.; Cherfils J.; Rossman K. L.; Der C. J. Ras Superfamily GEFs and GAPs: Validated and Tractable Targets for Cancer Therapy?. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10 (12), 842–857. 10.1038/nrc2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D.; Weinberg R. A. The Hallmarks of Cancer. Cell 2000, 100 (1), 57–70. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D.; Weinberg R. A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144 (5), 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pylayeva-Gupta Y.; Grabocka E.; Bar-Sagi D. RAS Oncogenes: Weaving a Tumorigenic Web. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11 (11), 761–774. 10.1038/nrc3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco E.; Spinelli M.; Vanoni M. Approaches to Ras Signaling Modulation and Treatment of Ras-Dependent Disorders: A Patent Review (2007–Present). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2012, 22 (11), 1263–1287. 10.1517/13543776.2012.728586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H.; Longo D. L.; Chabner B. A. Improving Prospects for Targeting RAS. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33 (31), 3650–3659. 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrem J. M. L.; Shokat K. M. Direct Small-Molecule Inhibitors of KRAS: From Structural Insights to Mechanism-Based Design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2016, 15 (11), 771–785. 10.1038/nrd.2016.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C. Y.; Tolias P. Recent Advances in Cancer Drug Discovery Targeting RAS. Drug Discovery Today 2016, 21 (12), 1915–1919. 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns M. C.; Sun Q.; Daniels R. N.; Camper D.; Kennedy J. P.; Phan J.; Olejniczak E. T.; Lee T.; Waterson A. G.; Rossanese O. W.; Fesik S. W. Approach for Targeting Ras With Small Molecules That Activate SOS-Mediated Nucleotide Exchange. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111 (9), 3401–3406. 10.1073/pnas.1315798111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes J. E.; Akan D. T.; Burns M. C.; Rossanese O. W.; Waterson A. G.; Fesik S. W. Small Molecule-Mediated Activation of RAS Elicits Biphasic Modulation of Phospho-ERK Levels That Are Regulated Through Negative Feedback on SOS1. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17 (5), 1051–1060. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott J. R.; Hodges T. R.; Daniels R. N.; Patel P. A.; Kennedy J. P.; Howes J. E.; Akan D. T.; Burns M. C.; Sai J.; Sobolik T.; Beesetty Y.; Lee T.; Rossanese O. W.; Phan J.; Waterson A. G.; Fesik S. W. Discovery of Aminopiperidine Indoles That Activate the Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor SOS1 and Modulate RAS Signaling. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61 (14), 6002–6017. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns M. C.; Howes J. E.; Sun Q.; Little A. J.; Camper D. V.; Abbott J. R.; Phan J.; Lee T.; Waterson A. G.; Rossanese O. W.; Fesik S. W. High-Throughput Screening Identifies Small Molecules That Bind to the RAS:SOS:RAS Complex and Perturb RAS Signaling. Anal. Biochem. 2018, 548, 44–52. 10.1016/j.ab.2018.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter J. J. G.; Anderson M.; Blades K.; Brassington C.; Breeze A. L.; Chresta C.; Embrey K.; Fairley G.; Faulder P.; Finlay M. R. V.; Kettle J. G.; Nowak T.; Overman R.; Patel S. J.; Perkins P.; Spadola L.; Tart J.; Tucker J. A.; Wrigley G. Small Molecule Binding Sites on the Ras:SOS Complex Can Be Exploited for Inhibition of Ras Activation. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58 (5), 2265–2274. 10.1021/jm501660t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering F.; Bikker J.; Humblet C. Escape from Flatland: Increasing Saturation as an Approach to Improving Clinical Success. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52 (21), 6752–6756. 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. F.Designing Drugs to Avoid Toxicity. In Progress in Medicinal Chemistry; Lawton G.; Witty D. R., Eds.; Elsevier: 2011; Vol. 50, pp 1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson L. A. Reactive Metabolites in the Biotransformation of Molecules Containing a Furan Ring. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2013, 26 (1), 6–25. 10.1021/tx3003824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns M. C.Small Molecule Modulation of the Ras-SOS Interaction in Cancer. Dissertation, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gilli G.; Gilli P. Towards an Unified Hydrogen-Bond Theory. J. Mol. Struct. 2000, 552 (1), 1–15. 10.1016/S0022-2860(00)00454-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meot-Ner M. The Ionic Hydrogen Bond. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105 (1), 213–284. 10.1021/cr9411785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilli P.; Gilli G. Hydrogen Bond Models and Theories: The Dual Hydrogen Bond Model and Its Consequences. J. Mol. Struct. 2010, 972 (1), 2–10. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2010.01.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.