Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the impact of body mass index (BMI) on survival of a Chinese cohort of medical patients with sepsis.

Design

A single-centre prospective cohort study conducted from May 2015 to April 2017.

Setting

A tertiary care university hospital in China.

Participants

A total of 178 patients with sepsis admitted to the medical intensive care unit (ICU) were included.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was 90-day mortality while the secondary outcomes were in-hospital mortality, length of ICU stay and length of hospital stay.

Results

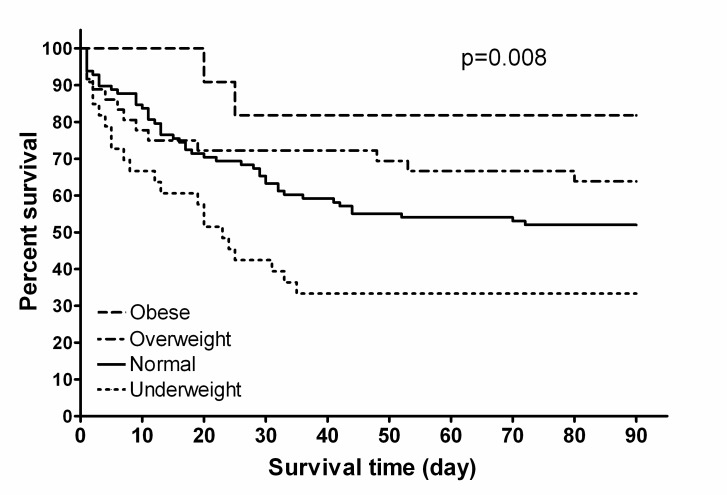

The median age (IQR) was 78 (66–84) years old, and 77.0% patients were older than 65 years. The 90-day mortality was 47.2%. The in-hospital mortality was 41.6%, and the length of ICU stay and hospital stay were 12 (5–22) and 15 (9–28) days, respectively. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis identified that Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (HR=1.229, p<0.001), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score (HR=1.050, p<0.001) and BMI (HR=0.940, p=0.029) were all independently associated with the 90-day mortality. Patients were divided into four groups based on BMI (underweight 33 (18.5%), normal 98 (55.1%), overweight 36 (20.2%) and obese 11 (6.2%)). The 90-day mortality (66.7%, 48.0%, 36.1% and 18.2%, p=0.015) and in-hospital mortality (60.6%, 41.8%, 30.6% and 18.2%, p=0.027) were statistically different among the four groups. Differences in survival among the four groups were demonstrated by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (p=0.008), with the underweight patients showing a lower survival rate.

Conclusions

BMI was an independent factor associated with 90-day survival in a Chinese cohort of medical patients with sepsis, with patients having a lower BMI at a higher risk of death.

Keywords: infectious diseases, thoracic medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This prospective observational cohort study focused on medical patients with sepsis and was conducted at a university hospital in China.

The impact of body mass index on 90-day survival of medical patients with sepsis was evaluated by Cox proportional hazard regression analysis and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis.

Our analyses were limited by the use of weight ascertained at intensive care unit admission rather than the patient’s baseline outpatient body weight.

Introduction

Sepsis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 Of these patients, half are treated in the intensive care unit (ICU).2 In a national population-based study of sepsis in Spain, medical diagnostic categories made up the majority of causes of sepsis, while surgical diagnoses were identified in only 26% of cases.3

Body mass index (BMI) is a simple index of weight-for-height that is commonly used to classify whether adults are underweight, overweight and obese.4 Several studies have examined the effects of BMI on mortality with conflicting conclusions. Lower mortality in the obese has been observed in some studies,5–9 but some researchers believe that the true paradox may lie in the variations in sepsis interventions, such as the administration of resuscitation fluids and antimicrobial therapy.6 In other studies, morbidly obese and underweight patients have been shown to be associated with higher mortality.10 11 Thus, the impact of BMI on survival of patients with sepsis is still controversial.12 13

As the relationship between BMI and clinical outcomes of sepsis is complex, we therefore set out to evaluate prospectively the impact of BMI on survival in a cohort of medical patients with sepsis admitted to the medical ICU in a university hospital.

Patients and methods

Design

This was a prospective cohort study, which was conducted in the medical ICU of a university-affiliated urban teaching hospital in China from May 2015 to April 2017.

Subjects

Sepsis was defined as the presence (probable or documented) of infection together with systemic manifestations of infection.14 Hospitalised patients admitted to the medical ICU with sepsis acquired in the community or in a hospital were eligible for the study if they met any of the following criteria of severe sepsis14: (1) sepsis-induced hypotension, (2) lactate above upper laboratory level limits (1.5 mmol/L in this study), (3) urine output <0.5 mL Kg-1 h-1 for more than 2 hours despite adequate fluid resuscitation, (4) acute lung injury with Pao2/Fio2 <250 in the absence of pneumonia as infection source, (5) acute lung injury with Pao2/Fio2 <200 in the presence of pneumonia as infection source, (6) creatinine >2.0 mg/dL (176.8 µmol/L), (7) bilirubin >2 mg/dL (34.2 µmol/L), (8) platelet count <100 000 µL and (9) coagulopathy (international normalised ratio (INR) >1.5).

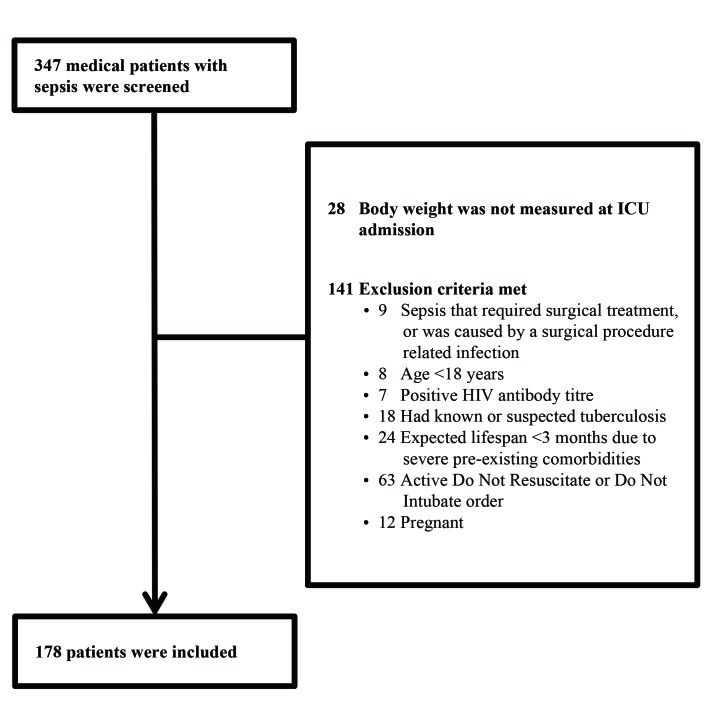

Patients were excluded from the study if they met one of the following criteria: (1) the patient had sepsis that required surgical treatment or was caused by a surgical procedure-related infection, (2) age <18 years, (3) the patient had a positive HIV antibody titre or had known/suspected tuberculosis at baseline, (4) expected lifespan <3 months due to severe pre-existing comorbidities, (5) active do not resuscitate or do not intubate order and (6) pregnant.

All patients accepted treatment according to the international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock.14 15 We collected the following demographic and clinical data: patient’s gender, age, weight, height, primary site of infection, community-acquired or hospital-acquired infection, blood pressure, lactate level, urine output, Pao2/Fio2, serum creatinine, total bilirubin, platelets, INR, Glasgow Coma Scale, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, non-invasive ventilation, intubation, positive blood culture, length of ICU stay and length of hospital stay. Those who survived to discharge were followed for at least 90 days.

BMI is defined as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres (kg/m2). Using the WHO criteria for designation of BMI,4 patients were classified as underweight (BMI <18.50 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI=18.50 to 24.99 kg/m2), overweight (BMI=25.0 to 29.99 kg/m2) and obese (BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was 90-day mortality, while the secondary outcomes were in-hospital mortality, length of ICU stay and length of hospital stay.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median (IQR) and categorical variables as numbers (%). Clinical data were compared between the in-hospital survivors and non-survivors. Continuous variables were compared using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test, and categorical variables were compared using the Χ 2 test. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was undertaken to assess the factors associated with 90-day mortality. The variables significantly associated with 90-day non-survival in the univariate analysis were used in the Cox proportional hazard regression analysis.

Patients were divided into four groups based on BMI (underweight, normal, overweight and obese). Clinical data were compared among the four groups, where continuous variables were compared using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis H test, and categorical variables were compared using the Χ2 test. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed to show the survival probabilities at day 90 according to BMI classification and compared using the log rank test.

All analyses were conducted using SPSS, V.22.0 (IBM). A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in developing the hypothesis, the specific aims or the research questions, nor were they involved in the design or implementation of this study. No patients were involved in the interpretation of study results or write up of the manuscript. There are no plans to involve patients in the dissemination of results.

Results

Figure 1 shows the patient selection process. In total, 178 medical patients with sepsis were included in this study, with male patients accounting for 65.2% (n=116). The median age (IQR) was 78 (66–84) years, and most patients were at least 65 years old (137/178, 77.0%). The most common primary site of infection was the lung (131 cases, 73.6%), followed by abdomen (15 cases, 8.4%), urinary tract (13 cases, 7.3%), gastrointestinal tract (12 cases, 6.7%) and other sites (7 cases, 3.9%). Patients with septic shock accounted for 33.1% (59 cases). Blood culture was positive in 38 patients (21.3%). The 90-day mortality was 47.2% (84/178 cases), and the in-hospital mortality was 41.6% (74/178 cases). The length of ICU stay and the length of hospital stay were 12 (5–22) and 15 (9–28) days, respectively.

Figure 1.

Patient selection. ICU, intensive care unit.

Compared with in-hospital survivors, non-survivors had significantly lower BMI and Pao2/Fio2 (both p<0.05), higher lactate, bilirubin, INR, SOFA score and APACHE II score (all p<0.05). Meanwhile, more patients died with healthcare-acquired infections, hypotension, oliguria, septic shock and intubation (all p<0.05) (table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographics and clinical data between groups defined by in-hospital clinical outcome in 178 patients with sepsis

| Characteristics | Survivors (n=104) |

Non-survivors (n=74) |

P values |

| Age (year) | 78.0 (60.0–84.0) | 78.0 (69.0–84.0) | 0.291 |

| Men | 67 (64.4) | 49 (66.2) | 0.805 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.2 (20.4–26.1) | 21.7 (18.4–24.2) | 0.006 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| COPD | 23 (22.1) | 9 (12.2) | 0.088 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 26 (25.0) | 21 (28.4) | 0.614 |

| Hypertension | 47 (45.2) | 31 (41.9) | 0.662 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 30 (28.8) | 15 (20.3) | 0.194 |

| Neoplasm | 18 (17.3) | 12 (16.2) | 0.848 |

| Liver disease | 5 (4.8) | 4 (5.4) | 1.000 |

| Heart failure | 20 (19.2) | 14 (18.9) | 0.958 |

| Chronic renal failure | 18 (17.3) | 11 (14.9) | 0.664 |

| Smoking (pack years) | 0 (0–30.0) | 0 (0–16.3) | 0.509 |

| Primary site of infection | |||

| Lung | 77 (74.0) | 54 (73.0) | 0.874 |

| Abdomen | 10 (9.6) | 5 (6.8) | 0.499 |

| Urinary tract | 7 (6.7) | 6 (8.1) | 0.728 |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 7 (6.7) | 5 (6.8) | 1.000 |

| Other site | 3 (2.9) | 4 (5.4) | 0.452 |

| Community-acquired infection | 85 (81.7) | 50 (67.6) | 0.030 |

| Hypotension | 22 (21.2) | 41 (55.4) | <0.001 |

| Lactate level (mmol/L) | 1.8 (1.0–3.4) | 2.7 (1.5–5.7) | 0.001 |

| Oliguria | 8 (7.7) | 16 (21.6) | 0.007 |

| Pao2/Fio2 (mm Hg) | 198.5 (119.3–287.5) | 152.5 (99.6–210.3) | 0.006 |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 97.0 (68.3–176.3) | 108.5 (64.0–194.3) | 0.868 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/mL) | 13.1 (9.9–22.3) | 18.0 (12.5–32.8) | 0.015 |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 161.0 (95.8–232.5) | 123.0 (75.0–204.3) | 0.067 |

| INR | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 0.015 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 15.0 (10.0–15.0) | 13.0 (10.0–15.0) | 0.117 |

| SOFA score | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 9.0 (7.0–11.0) | <0.001 |

| APACHE II score | 16.0 (12.0–22.0) | 21.0 (17.0–30.0) | <0.001 |

| Septic shock | 21 (20.2) | 38 (51.4) | <0.001 |

| Non-invasive ventilation | 28 (26.9) | 24 (32.4) | 0.426 |

| Intubated | 36 (34.6) | 43 (58.1) | 0.002 |

| Positive blood culture | 19 (18.3) | 19 (25.7) | 0.235 |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 12.0 (6.0–22.0) | 12.0 (3.0–25.0) | 0.521 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 18.0 (10.0–30.0) | 13.0 (3.0–25.0) | 0.009 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (IQR) unless stated otherwise.

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health evaluation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit; INR, international normalised ratio; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was conducted, and the independent factors for 90-day death were identified as SOFA score (HR=1.220, p<0.001), APACHE II score (HR=1.050, p<0.001) and BMI (HR=0.940, p=0.029) (table 2).

Table 2.

Risk factors for 90-day mortality of patients with sepsis or septic shock by Cox regression analysis

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P values |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.940 (0.889 to 0.994) | 0.029 |

| Hypotension | 0.781 (0.229 to 2.670) | 0.694 |

| Lactate level (mmol/L) | 1.018 (0.943 to 1.098) | 0.648 |

| Oliguria | 1.288 (0.715 to 2.321) | 0.399 |

| Pao2/Fio2 (mm Hg) | 1.000 (0.997 to 1.002) | 0.933 |

| Septic shock | 1.075 (0.320 to 3.615) | 0.907 |

| SOFA score | 1.229 (1.123 to 1.345) | <0.001 |

| APACHE II score | 1.050 (1.022 to 1.080) | <0.001 |

| Intubated | 1.511 (0.931 to 2.452) | 0.095 |

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

The variables significantly associated with 90-day non-survival in the univariate analysis were used in the Cox proportional hazard regression analysis.

Patients were divided into four groups based on BMI (underweight 33 (18.5%), normal 98 (55.1%), overweight 36 (20.2%) and obese 11 (6.2%)). The percentage of men (72.7%, 71.4%, 55.6% and 18.2%, p=0.002), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (24.2%, 21.4%, 0 and 27.3%, p=0.017), hypotension (57.6%, 34.7%, 25.0% and 9.1%, p=0.007), septic shock (57.6%, 30.6%, 25.0% and 9.1%, p=0.004), in-hospital mortality (60.6%, 41.8%, 30.6% and 18.2%, p=0.027) and 90-day mortality (66.7%, 48.0%, 36.1% and 18.2%, p=0.015) were statistically different among the four groups (table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of demographics and clinical data among groups defined by body mass index in patients with sepsis

| Characteristics | Underweight (n=33) |

Normal (n=98) |

Overweight (n=36) |

Obese (n=11) |

P values |

| Age (years) | 79.0 (69.0–86.0) | 78.0 (67.0–84.0) | 73.0 (57.0–83.0) | 77.0 (71.0–86.0) | 0.162 |

| Males | 24 (72.7) | 70 (71.4) | 20 (55.6) | 2 (18.2) | 0.002 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| COPD | 8 (24.2) | 21 (21.4) | 0 | 3 (27.3) | 0.017 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (24.2) | 25 (25.5) | 9 (25.0) | 5 (45.5) | 0.530 |

| Hypertension | 14 (42.4) | 38 (38.8) | 19 (52.8) | 7 (63.6) | 0.265 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 10 (30.3) | 24 (24.5) | 11 (30.6) | 0 | 0.193 |

| Neoplasm | 7 (21.2) | 14 (14.3) | 8 (22.2) | 1 (9.1) | 0.547 |

| Liver disease | 2 (6.1) | 5 (5.1) | 2 (5.6) | 0 | 0.879 |

| Heart failure | 8 (24.2) | 17 (17.3) | 5 (13.9) | 4 (36.4) | 0.319 |

| Chronic renal failure | 5 (15.2) | 14 (14.3) | 7 (19.4) | 3 (27.3) | 0.669 |

| Smoking (pack years) | 0 (0–20.5) | 0 (0–30.0) | 0 (0–3.0) | 0 (0–30.0) | 0.561 |

| Primary site of infection | |||||

| Lung | 27 (81.8) | 69 (70.4) | 27 (75.0) | 8 (72.7) | 0.637 |

| Abdomen | 2 (6.1) | 9 (9.2) | 3 (8.3) | 1 (9.1) | 0.956 |

| Urinary tract | 1 (3.0) | 9 (9.2) | 2 (5.6) | 1 (9.1) | 0.656 |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 2 (6.1) | 6 (6.1) | 3 (8.3) | 1 (9.1) | 0.955 |

| Other site | 1 (3.0) | 5 (5.1) | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 0.800 |

| Community-acquired infection | 25 (75.8) | 76 (77.6) | 26 (72.2) | 8 (72.7) | 0.925 |

| Hypotension | 19 (57.6) | 34 (34.7) | 9 (25.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0.007 |

| Lactate level (mmol/L) | 2.4 (1.6–7.2) | 2.1 (1.0–4.3) | 1.6 (1.2–3.3) | 1.9 (0.6–2.9) | 0.201 |

| Oliguria | 8 (24.2) | 13 (13.3) | 3 (8.3) | 0 | 0.121 |

| Pao2/Fio2 (mm Hg) | 180.0 (113.5–251.0) | 164.5 (102.3–240.5) | 188.0 (140.5–268.5) | 215.0 (153.0–300.0) | 0.340 |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 89.0 (57.0–127.0) | 118.5 (72.5–190.5) | 91.0 (60.0–212.5) | 86.0 (56.0–112.0) | 0.136 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/mL) | 18.0 (10.1–33.1) | 14.4 (10.1–28.4) | 17.2 (12.2–26.3) | 15.2 (11.3–20.0) | 0.819 |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 139.0 (75.0–213.0) | 147.0 (86.0–209.8) | 182.5 (128.3–253.8) | 115.0 (49.0–144.0) | 0.056 |

| INR | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.269 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 13.0 (10.0–15.0) | 15.0 (12.0–15.0) | 15.0 (11.0–15.0) | 13.0 (10.0–15.0) | 0.761 |

| SOFA score | 8.0 (5.0–11.0) | 7.0 (5.0–9.0) | 6.0 (4.0–8.0) | 5.0 (5.0–8.0) | 0.382 |

| APACHE II score | 18.0 (16.0–24.0) | 19.0 (13.0–25.0) | 18.0 (13.0–22.0) | 14.0 (9.0–17.0) | 0.060 |

| Septic shock | 19 (57.6) | 30 (30.6) | 9 (25.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0.004 |

| Non-invasive ventilation | 7 (21.2) | 30 (30.6) | 10 (27.8) | 5 (45.5) | 0.466 |

| Intubated | 19 (57.6) | 43 (43.9) | 13 (36.1) | 4 (36.4) | 0.305 |

| Positive blood culture | 7 (21.2) | 24 (24.5) | 4 (11.1) | 3 (27.3) | 0.383 |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 10.0 (4.0–25.0) | 13.0 (7.0–25.0) | 11.0 (4.0–19.0) | 9.0 (6.0–13.0) | 0.461 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 13.0 (4.0–29.0) | 16.0 (10.0–28.0) | 16.0 (8.0–32.0) | 13.0 (8.0–20.0) | 0.813 |

| In-hospital mortality | 20 (60.6) | 41 (41.8) | 11 (30.6) | 2 (18.2) | 0.027 |

| 90-day mortality | 22 (66.7) | 47 (48.0) | 13 (36.1) | 2 (18.2) | 0.015 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (IQR).

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit; INR, international normalised ratio; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed to show the survival probabilities at day 90 according to BMI classification, and these were compared using the log rank test, which also showed that higher BMI was associated with better prognosis (p=0.008) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot for 90-day survival of underweight, normal weight, overweight and obese patients with sepsis.

Discussion

This prospective observational cohort study focused on medical patients with sepsis admitted to the ICU, and the results showed that besides SOFA score and APACHE II score, BMI was identified as an independent factor for 90-day mortality by Cox regression analysis. The association of SOFA and APACHE II score with mortality in this cohort was consistent with previous studies.16–18 This study adds the finding that BMI was independently associated with survival, where 90-day mortality decreased with an increase in BMI. While studies examining the risk factors associated with outcomes in sepsis reached inconsistent conclusions on the association of BMI with mortality, our results confirmed that BMI was independently associated with mortality in patients with sepsis caused by medical conditions.

Globally, the prevalence of obesity has reached epidemic proportions, especially in developed countries.19 BMI is still a useful proxy of overall health because it is highly correlated with body surface area, which is commonly used as a surrogate measure in obesity classification. Even though it is widely accepted that obesity is a risk factor for diabetes mellitus, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases, the present study and several other studies have indicated that overweight and obese patients with sepsis tend to experience lower mortality. This has been called the ‘obesity paradox’.5–9 20 Although some researchers have expressed doubt that the true paradox may lie in the variations in sepsis interventions,6 21 a meta-analysis concluded that individuals who were overweight or obese had a reduced adjusted mortality when admitted to the ICU with sepsis or septic shock.8 Recently, another meta-analysis also concluded that being overweight was associated with lower mortality (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.97, p=0.02) compared with obese (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.10, p=0.29) and morbidly obese (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.08, p=0.09) patients who did not exhibit significantly reduced mortality compared with normal weight patients.12 In a large and nationally representative sample of over 1000 hospitals in the USA, obesity was found to be significantly associated with a 16% decrease in the odds of dying among patients with sepsis who were hospitalised.22

Underweight patients with sepsis may be more common in developing countries than in developed countries. In the present study, the percentages of underweight, normal weight, overweight and obese patients were 18.4%, 55.3%, 20.1% and 6.1%, respectively, while those with sepsis in a study in Canada and the USA represented 6.8%, 35.3%, 28.3% and 29.0%.6 Being underweight was found to be one of the independent risk factors of mortality in a study on the correlation between surgical site infection and mortality.10 Furthermore, Lee et al 11 also reported that being underweight was associated with mortality in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. However, BMI has not been shown to be an independent factor for clinical outcomes by multivariable analyses. In our cohort of medical patients with sepsis, which mainly included elderly and less obese patients, BMI was identified as an independent factor for survival, patients with lower BMI having a higher risk of death. Thus, our findings would be helpful for evaluating the clinical outcomes of medical patients with sepsis, although validation in future large sample, multi-centre studies is still needed.

The mechanism of the correlation between BMI and mortality of sepsis is unclear. There are several potential reasons that could explain this. First, higher BMI resulted in more fat reserves, and patients could have a greater capacity to cope with the inflammatory response during sepsis and sepsis-associated acute lung injury.23–25 Furthermore, they may be able to tolerate extensive weight loss and dysfunction associated with critical illness.26 Second, a higher BMI can lead to an increased level of lipoproteins. High-density lipoproteins may bind and inactivate lipopolysaccharide or other harmful bacterial products released during sepsis27 and modulate adhesion molecule expression, upregulate endothelial nitric oxide synthase and counteract oxidative stress.28 Third, higher BMI can lead to increased adipose tissue deposition. Adipose tissue is increasingly being considered as a functional endocrine organ and associated with increased renin–angiotensin system activity.29 It appears to have protective haemodynamic effects during sepsis and may decrease the need for fluid or vasopressor support.21 30

In general, sex has not been found to be an independent predictor for survival in patients with sepsis, which is the same as the results of our current study. But in some special populations, for example in patients with liver cirrhosis with bloodstream infection, male sex may be an independent risk factor for mortality.31

As the relationship between BMI and clinical outcomes of sepsis may be related partly to differences in patient characteristics, we therefore set out to evaluate the impact of BMI on survival in a cohort of medical patients with sepsis, which is different from surgical septic patients. Ranieri et al 32 reported that the primary sites of infection in adults with septic shock were lung (43.9%), abdomen (30.0%), urinary tract (12.3%), skin (5.5%) and other sites (8.3%). Scheer et al 33 found that the most common primary site of infection was different between medical and surgical patients. In medical patients, the lung was the most common primary site (42.0%–56.7%), while it was abdomen (48.4%–64.4%)%) in surgical patients. It should be noted that in the majority of our patients (73.6%), sepsis was associated with pulmonary infection, a much higher percentage as compared with other studies. He et al34 reported that pulmonary sepsis showed worse outcome than abdominal sepsis, and pulmonary infection was a risk factor for 1-year mortality and quality of life after sepsis.

There were several limitations to our study. First, the BMI of our patients ranged from 12.11 to 32.46. There was no morbidly obese patient in the current study. In fact, morbidly obese people are rare in this country. Ten severely underweight patients with BMI <16.0 were included in the present study, which introduces possible sample bias in patients in the low BMI category. However, the 90-day and in-hospital mortality of these 10 severely underweight patients were 70.0% and 60.0% respectively, not significantly different from that of all 33 underweight patients (66.7% and 60.6%, respectively). Second, the present study used weight ascertained at ICU admission, rather than the patient’s baseline outpatient body weight. This practice may misclassify the BMI category in as many as 21.9% of patients due to lack of fluid balance adjustment.35 Third, BMI was used to determine the nutritional status of patients in this study. BMI is a simple index and widely used in clinical practice, but other indices such as percent body fat might better reflect body composition.36 Finally, it was a single-centre study with 178 participants, and a large proportion of our patients were older than 65 years, which may have led to a sample-related bias.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective cohort study that focused on medical patients with sepsis, showing that BMI was independently associated with 90-day survival, with patients having a lower BMI at a higher risk of death.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: QTZ, YCS, YAZ: designed the study. QTZ, YCS, NS, YAZ, QBM: coordinated the study. MW, JZ, YLD, SL, HXG: were responsible for patient screening, enrollment and follow-up. QTZ, MW, YCS: analysed the data. QTZ: drafted the manuscript. YCS: critically revised the manuscript. All authors had full access to all study data, read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved (approval number M2015021) by the ethics committee of Peking University Third Hospital, Beijing, China.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

- 1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315:801–10. 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2063;2013:369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bouza C, López-Cuadrado T, Saz-Parkinson Z, et al. Epidemiology and recent trends of severe sepsis in Spain: a nationwide population-based analysis (2006-2011). BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:3863 10.1186/s12879-014-0717-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. WHO, 2015. WHO classification of body mass index (BMI). http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html (accessed on 2 Mar 2015).

- 5. Wurzinger B, Dünser MW, Wohlmuth C, et al. The association between body-mass index and patient outcome in septic shock: a retrospective cohort study. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2010;122:31–6. 10.1007/s00508-009-1241-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arabi YM, Dara SI, Tamim HM, et al. Clinical characteristics, sepsis interventions and outcomes in the obese patients with septic shock: an international multicenter cohort study. Crit Care 2013;17:R72 10.1186/cc12680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Prescott HC, Chang VW, O’Brien JM, et al. Obesity and 1-year outcomes in older Americans with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2014;42:1766–74. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pepper DJ, Sun J, Welsh J, et al. Increased body mass index and adjusted mortality in ICU patients with sepsis or septic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2016;20:181 10.1186/s13054-016-1360-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gaulton TG, Marshall MacNabb C, Mikkelsen ME, et al. A retrospective cohort study examining the association between body mass index and mortality in severe sepsis. Intern Emerg Med 2015;10:471–9. 10.1007/s11739-015-1200-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giles KA, Hamdan AD, Pomposelli FB, et al. Body mass index: surgical site infections and mortality after lower extremity bypass from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program 2005-2007. Ann Vasc Surg 2010;24:48–56. 10.1016/j.avsg.2009.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee SM, Kang JW, Jo YH, et al. Underweight is associated with mortality in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Med Exp 2015;3:A876 10.1186/2197-425X-3-S1-A876 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang S, Liu X, Chen Q, et al. The role of increased body mass index in outcomes of sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol 2017;17:118 10.1186/s12871-017-0405-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ng PY, Eikermann M. The obesity conundrum in sepsis. BMC Anesthesiol 2017;17:147 10.1186/s12871-017-0434-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med 2013;41:580–637. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:304–77. 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Carvalho MA, Freitas FG, Silva Junior HT, et al. Mortality predictors in renal transplant recipients with severe sepsis and septic shock. PLoS One 2014;9:e111610 10.1371/journal.pone.0111610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Innocenti F, Tozzi C, Donnini C, et al. SOFA score in septic patients: incremental prognostic value over age, comorbidities, and parameters of sepsis severity. Intern Emerg Med 2018;13:405–12. 10.1007/s11739-017-1629-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Song JE, Kim MH, Jeong WY, et al. Mortality risk factors for patients with septic shock after implementation of the surviving sepsis campaign bundles. Infect Chemother 2016;48:199–208. 10.3947/ic.2016.48.3.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N Engl J Med 2017;377:13–27. 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Atamna A, Elis A, Gilady E, et al. How obesity impacts outcomes of infectious diseases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2017;36:585–91. 10.1007/s10096-016-2835-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Taylor SP, Karvetski CH, Templin MA, et al. Initial fluid resuscitation following adjusted body weight dosing is associated with improved mortality in obese patients with suspected septic shock. J Crit Care 2018;43:7–12. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nguyen AT, Tsai CL, Hwang LY, et al. Obesity and Mortality, Length of Stay and Hospital Cost among Patients with Sepsis: A Nationwide Inpatient Retrospective Cohort Study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0154599 10.1371/journal.pone.0154599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stapleton RD, Dixon AE, Parsons PE, et al. The association between BMI and plasma cytokine levels in patients with acute lung injury. Chest 2010;138:568–77. 10.1378/chest.10-0014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stapleton RD, Suratt BT. Obesity and nutrition in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Chest Med 2014;35:655–71. 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zampieri FG, Jacob V, Barbeiro HV, et al. Influence of body mass index on inflammatory profile at admission in critically ill septic patients. Int J Inflam 2015;2015:1–6. 10.1155/2015/734857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003;348:683–93. 10.1056/NEJMoa022450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu A, Hinds CJ, Thiemermann C. High-density lipoproteins in sepsis and septic shock: metabolism, actions, and therapeutic applications. Shock 2004;21:210–21. 10.1097/01.shk.0000111661.09279.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murch O, Collin M, Hinds CJ, et al. Lipoproteins in inflammation and sepsis. I. Basic science. Intensive Care Med 2007;33:13–24. 10.1007/s00134-006-0432-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McGown C, Birerdinc A, Younossi ZM. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Clin Liver Dis 2014;18:41–58. 10.1016/j.cld.2013.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salgado DR, Rocco JR, Silva E, et al. Modulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in sepsis: a new therapeutic approach? Expert Opin Ther Targets 2010;14:11–20. 10.1517/14728220903460332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhao H, Gu X, Zhao R, et al. Evaluation of prognostic scoring systems in liver cirrhosis patients with bloodstream infection. Medicine 2017;96:e8844 10.1097/MD.0000000000008844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ranieri VM, Thompson BT, Barie PS, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in adults with septic shock. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2055–64. 10.1056/NEJMoa1202290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Scheer CS, Fuchs C, Kuhn SO, et al. Quality Improvement initiative for severe sepsis and septic shock reduces 90-day mortality: a 7.5-year observational study. Crit Care Med 2017;45:241–52. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. He XL, Liao XL, Xie ZC, et al. Pulmonary Infection is an independent risk factor for long-term mortality and quality of life for sepsis patients. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:421 10.1155/2016/4213712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. O’Brien JM, Philips GS, Ali NA, et al. The association between body mass index, processes of care, and outcomes from mechanical ventilation: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care Med 2012;40:1456–63. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823e9a80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Waisbren E, Rosen H, Bader AM, et al. Percent body fat and prediction of surgical site infection. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210:381–9. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.