This report provides tools for robust and predictable control of gene expression in the model lithoautotroph C. necator H16. To address a current need, we designed, built, and tested promoters and RBSs for controlling gene expression in C. necator H16. To answer a question on how existing and newly developed inducible systems compare, two positively (AraC/ParaBAD-l-arabinose and RhaRS/PrhaBAD-l-rhamnose) and two negatively (AcuR/PacuRI-acrylate and CymR/Pcmt-cumate) regulated inducible systems were quantitatively evaluated and their induction kinetics analyzed. To establish if gene expression can be further improved, the effect of genetic elements, such as mRNA stem-loop structure and A/U-rich sequence, on gene expression was evaluated. Using isoprene production as an example, the study investigated if and to what extent chemical compound yield correlates to the level of gene expression of product-synthesizing enzyme.

KEYWORDS: promoter, ribosome binding site, functional genetic element, gene expression, isoprene, Cupriavidus necator H16

ABSTRACT

A robust and predictable control of gene expression plays an important role in synthetic biology and biotechnology applications. Development and quantitative evaluation of functional genetic elements, such as constitutive and inducible promoters as well as ribosome binding sites (RBSs), are required. In this study, we designed, built, and tested promoters and RBSs for controlling gene expression in the model lithoautotroph Cupriavidus necator H16. A series of variable-strength, insulated, constitutive promoters exhibiting predictable activity within a >700-fold dynamic range was compared to the native PphaC, with the majority of promoters displaying up to a 9-fold higher activity. Positively (AraC/ParaBAD-l-arabinose and RhaRS/PrhaBAD-l-rhamnose) and negatively (AcuR/PacuRI-acrylate and CymR/Pcmt-cumate) regulated inducible systems were evaluated. By supplying different concentrations of inducers, a >1,000-fold range of gene expression levels was achieved. Application of inducible systems for controlling expression of the isoprene synthase gene ispS led to isoprene yields that exhibited a significant correlation to the reporter protein synthesis levels. The impact of designed RBSs and other genetic elements, such as mRNA stem-loop structure and A/U-rich sequence, on gene expression was also evaluated. A second-order polynomial relationship was observed between the RBS activities and isoprene yields. This report presents quantitative data on regulatory genetic elements and expands the genetic toolbox of C. necator.

IMPORTANCE This report provides tools for robust and predictable control of gene expression in the model lithoautotroph C. necator H16. To address a current need, we designed, built, and tested promoters and RBSs for controlling gene expression in C. necator H16. To answer a question on how existing and newly developed inducible systems compare, two positively (AraC/ParaBAD-l-arabinose and RhaRS/PrhaBAD-l-rhamnose) and two negatively (AcuR/PacuRI-acrylate and CymR/Pcmt-cumate) regulated inducible systems were quantitatively evaluated and their induction kinetics analyzed. To establish if gene expression can be further improved, the effect of genetic elements, such as mRNA stem-loop structure and A/U-rich sequence, on gene expression was evaluated. Using isoprene production as an example, the study investigated if and to what extent chemical compound yield correlates to the level of gene expression of product-synthesizing enzyme.

INTRODUCTION

Cupriavidus necator H16 is a Gram-negative betaproteobacterium, formerly known as Ralstonia eutropha, Alcaligenes eutrophus, Wautersia eutropha, and Hydrogenomonas eutropha. It has been extensively studied for its capacity to store large amounts of organic carbon in the form of poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) that can be utilized as a source of bioplastics (1, 2). Importantly, this chemolithoautotrophic bacterium possesses the ability to use both organic compounds and molecular hydrogen (H2) as sources of energy, utilizing them to power metabolic processes and fix carbon dioxide (CO2) (3). In the absence of oxygen (O2), C. necator H16 can switch to anaerobic respiration-denitrification, exploiting alternative electron acceptors such as nitrite (NO2−) or nitrate (NO3−) (4). Such flexible energy metabolism of this bacterium enables an unrestricted exchange between heterotrophic, mixotrophic, and autotrophic growth conditions. Moreover, the ongoing research into the metabolism of C. necator reveals a wide range of metabolic activities, which can offer unique pathways, intermediates, and products of biotechnological interest (5–8).

Alongside its beneficial use in the process of production of biodegradable plastics (1), C. necator H16 has gained prominence as a chassis for the production of fuels, chemicals, and proteins (9–11), including ethanol, isopropanol, isobutanol, 3-methyl-1-butanol, methyl ketones, alkanes and alkenes, 2-hydroxyisobutyrate, and fatty acids (12–19). Several studies demonstrated that use of C. necator allows achievement of a high cell density, more than 200 g/liter of biomass, without accumulating growth inhibitory organic acids and seemingly precluding formation of inclusion bodies in recombinant protein production (9, 10, 20). These beneficial characteristics imply that C. necator H16 can be used as an alternative expression host.

To develop and optimize biosynthetic pathways in metabolically engineered microorganisms, genome alterations often require either an adjustment of gene expression or an introduction of heterologous genes, in both cases utilizing functional genetic elements that control the gene expression (21). Such genetic elements include promoters (constitutive and inducible) and ribosome binding sites (RBSs), with latter containing Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence and in some cases other regulatory mRNA elements, such as palindromic (forming stem-loop structure) or/and A/U-rich sequences (22–26). A few studies have reported on the characterization of functional genetic elements in C. necator H16. The heterologous inducible promoters ParaBAD (l-arabinose), PxylS (m-toluic acid), Plac (lactose), PhpdH (3-hydroxypropionic acid), and PrhaBAD (l-rhamnose) (16, 27–29), the synthetic anhydrotetracycline- and cumate-inducible promoters (30, 31), and several native promoters (27) have been shown to be suitable to control and drive gene expression in C. necator. Escherichia coli-derived promoters PlacUV5, Ptrc, and Ptrp have been applied to regulate expression of R-specific enoyl coenzyme A (enoyl-CoA) hydratases, allowing modulation of the proportion of the (R)-3-hydroxyhexanoate monomer in poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate] (32). A few constitutive promoters, derived from bacteriophage T5, containing only a core promoter sequence displayed much higher activity in C. necator than the commonly used strong promoter Ptac (20). In addition, Bi and coworkers (16) have demonstrated that inclusion of a 5′ mRNA stem-loop structure upstream of the RBS sequence increases gene expression from inducible promoter ParaBAD 2-fold in C. necator H16.

A strong need to expand the synthetic biology toolbox remains, aiming to broaden the range of functional genetic elements for controlling gene expression in C. necator. Inducible control systems involving either positive or negative regulators are also required for highly controllable circuits in synthetic biology and biotechnology applications. Importantly, the quantitative and comparative evaluation of existing and new functional genetic elements is needed to facilitate genetic and metabolic engineering. The aim of this study was to design, build, and quantitatively characterize sets of constitutive promoters and RBSs, which would provide a wide range of strengths for gene expression control. Four inducible systems, known to have practical application in other microbial chassis, were assembled and characterized in a comparative manner. Inducible systems and a set of RBSs are applied for controlling expression of the ispS gene, leading to variable isoprene production.

RESULTS

Assembly and quantitative evaluation of insulated constitutive promoters.

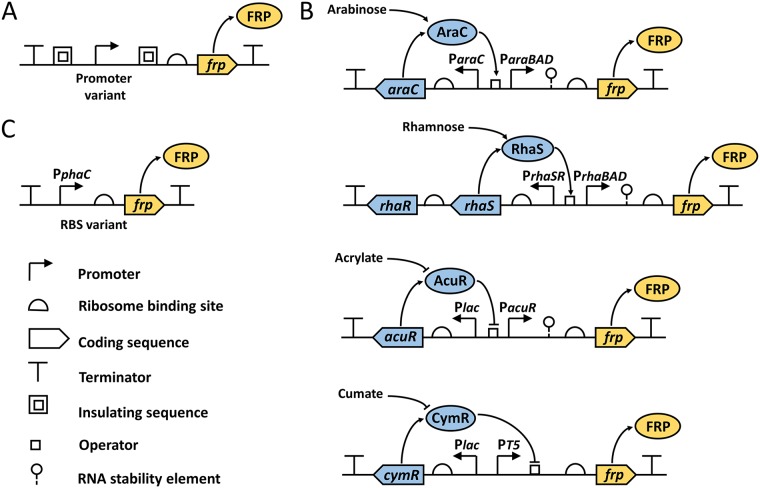

To generate libraries of functional genetic elements, a quick, reliable and preferably one-pot-reaction strategy allowing a simultaneous assembly of multiple DNA fragments is desirable. Taking this into account, for assembly of the promoter library we chose to employ the uracil-specific excision reagent (USER)-based engineering and cloning method (33). Using pBBR1MCS-2 (34) and modular pMTL71101 as plasmid backbones, we constructed vectors pBBR1-USER and pMTL71107, respectively, containing a USER cassette to assist with the assembly (see Materials and Methods for details). In total, 26 promoter variants were constructed in both vectors. To enable measurement of their strengths, promoters were transcriptionally fused to a gene encoding enhanced yellow fluorescence protein (eYFP) and a strong RBS, a 27-nucleotide upstream sequence of the bacteriophage T7 gene 10 (T7g10) (35), was placed directly upstream of the reporter gene. A variety of promoter strengths was achieved by combining core promoter sequences of previously characterized promoters from C. necator, E. coli, and bacteriophages T4 and T5 (3, 36–38) with upstream and downstream insulation sequences (Fig. 1A). Such insulation sequences have been reported to increase the predictability of promoters by reducing the influence of the different sequence/genomic context (39). The core promoter sequences used in this study are listed in Table 1.

FIG 1.

Design of promoter and RBS constructs. Shown are SBOL (67) visual representations of constructs that contain constitutive promoter (A), four inducible systems (B) and RBS (C). SBOL visual icons are specified. FRP, fluorescent reporter protein.

TABLE 1.

Core promoter sequences used for insulated constitutive promoter library

aThe core promoter sequence containing bacterial RNA polymerase binding determinants, −10 and −35 boxes (underlined), and transcription start site (in bold) was predicted using the Neural Network Promoter Prediction tool (68).

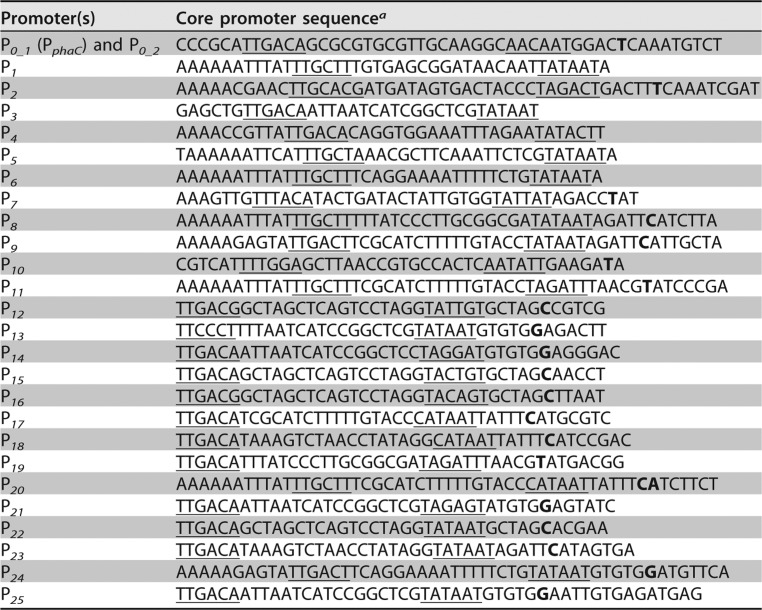

Plasmids with insulated constitutive promoters were transformed into C. necator H16 by electroporation. A promoterless construct (P0) was included as negative control. Resulting C. necator strains were cultured in minimal medium (MM) and the single-time-point fluorescence of the logarithmically growing cells was determined as a measure of eYFP protein concentration normalized to the cell density (Fig. 2). A majority of promoters were significantly stronger than the native PphaC (P0_1+SD) or any other C. necator promoters characterized so far, with promoters P22 and P24 showing 9-fold higher activity. Strengths of respective promoters were comparable in the pBBR1MCS-2 and pMTL71101 vector backbones (Fig. 2, inset). Activities of the insulated promoters P1, P2, P4, P5, and P6, which contained core promoters PT5, PH16_B1772, Pj5, Ph207, and Pn25, respectively, correlated with previously published data (20) obtained using enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) as a reporter and corresponding core promoter elements (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Notably, a wide coverage of promoter strengths spanning over a 700-fold range was achieved in the developed promoter library.

FIG 2.

Quantitative evaluation of constitutive promoter strengths. The strengths of different promoters were determined by their abilities to drive expression of the fluorescence reporter. C. necator H16 cells harboring the variants of promoter-reporter constructs in either the pBBR1MCS-2 or pMTL71101 backbone were grown in MM as described in Materials and Methods. To determine normalized absolute fluorescence, the optical density at 600 nm and EYFP fluorescence were measured. Error bars represent standard deviations from three biological replicates. The asterisk indicates statistically significant difference between promoter strengths in different vector backbones (P < 0.05, unpaired t test). Correlation between strengths of respective promoters placed in two different plasmid backbones, pBBR1MCS-2 and pMTL71101, is shown in the inset.

Inducible systems and their quantitative evaluation in C. necator H16.

Inducible promoters are indispensable tools within the context of synthetic biology to control gene expression. To date, a number of transcription-based inducible systems have been tested in C. necator (16, 27–31). However, the genetic contexts in which they have been evaluated differ considerably, making it difficult to compare their outputs.

We chose to evaluate and compare two positively and two negatively regulated inducible systems. The AraC/ParaBAD-l-arabinose-, RhaRS/PrhaBAD-l-rhamnose-, and CymR/Pcmt-cumate-inducible systems have been employed previously in C. necator (16, 29, 31). The fourth system is regulated by AcuR, a repressor protein from Rhodobacter sphaeroides mediating gene expression from PacuRI in the presence of acrylate (40). Reporter systems were designed as described recently for the modular reporter plasmid pEH006. It contains the l-arabinose-inducible system and was demonstrated to be a suitable original vector for the evaluation of inducible systems (28). Vectors were constructed in such a way that the transcriptional regulator (TR) coding sequences are located in opposite direction of the rfp reporter gene (Fig. 1B). The genes encoding the activator proteins AraC and RhaRS are expressed from their native promoters to maintain TR-mediated autoregulation (41, 42), whereas the E. coli lac promoter including lacI operator was used to control transcription of the genes encoding the transcriptional repressors AcuR and CymR. Utilization of repressible lac promoter enabled elimination of a toxic effect caused by overexpression of transcriptional repressors in E. coli when assembling vectors. Expression of rfp is driven by the corresponding inducible promoter. The native l-arabinose-, l-rhamnose-, and acrylate-inducible promoters were designed to harbor a T7g10 mRNA stem-loop structure with the aim to enhance gene expression through improved RNA stability (43). For the cumate-inducible system, a synthetic promoter composed of the phage T5 promoter and the operator sequence of the cmt operon was employed (44). The same RBS as for the constitutive promoters was used in all of the constructs.

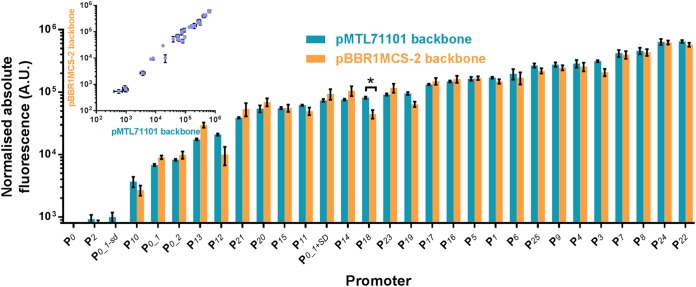

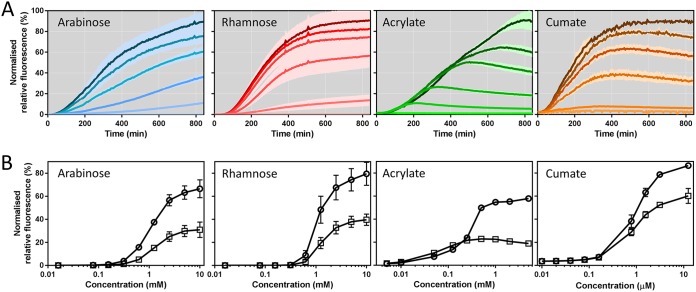

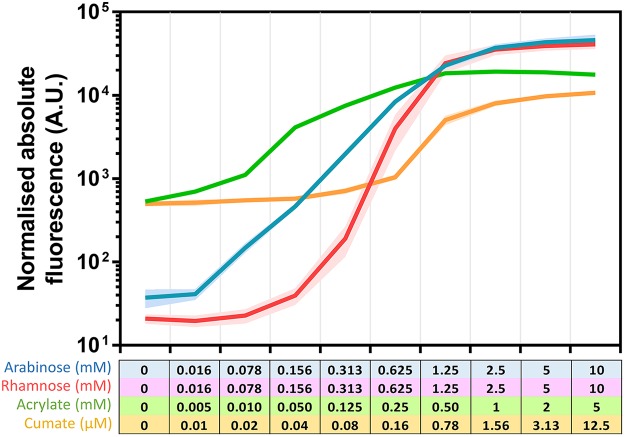

Plasmids harboring inducible systems were transformed into C. necator H16 and analyzed for fluorescence output over time at different inducer concentrations (Fig. 3A). The resulting dose-response curves provide information about each system's dynamic range (Fig. 3B). For example, gene expression controlled by the l-arabinose-inducible system can be fine-tuned in the range between 0.313 and 2.5 mM l-arabinose for a linear output. The exponential increase in fluorescence output stretches more widely, between 0.016 and 1.25 mM. Furthermore, absolute normalized fluorescence values were used to calculate the red fluorescent protein (RFP) synthesis rate at any time point during the time course of experiment. The resulting maximum synthesis rate was fitted to the corresponding inducer concentration using a Hill function (Fig. S2), providing key parameters such as the maximum possible rate of RFP synthesis, the Hill coefficient, or the inducer concentration mediating half-maximal RFP synthesis (Table S3). According to the fitted data, the l-rhamnose-inducible system demonstrated the highest induction cooperativity (h = 3.88). It requires a minimum concentration of 0.156 mM l-rhamnose to be activated and achieves about 85% of maximum expression at 2.5 mM. The acrylate- and cumate-inducible systems generally require lower inducer levels to initiate gene expression. Moreover, the range of inducer concentration mediating a linear fluorescence output spans more than 1 order of magnitude (5 to 125 μM and 0.08 to 1.56 μM, for acrylate and cumate, respectively) and therefore can be fine-tuned more easily.

FIG 3.

Induction kinetics and dose response for the l-arabinose-, l-rhamnose-, acrylate-, and cumate-inducible systems. (A) Normalized relative fluorescence of C. necator H16 harboring the l-arabinose-, l-rhamnose-, acrylate-, and cumate-inducible systems. Inducers were added at time zero and fluorescence was monitored for 14 h. The darker the color shade, the higher the inducer concentration. l-Arabinose was supplemented to final concentrations of 10, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, and 0.313 mM or omitted. l-Rhamnose was supplemented to final concentrations of 10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, and 0.625 mM or omitted. Acrylate was supplemented to final concentrations of 5, 1, 0.5, 0.25, and 0.05 mM or omitted. Cumate was supplemented to final concentrations of 12.5, 3.13, 1.56, 0.78, and 0.16 μM or omitted. The standard deviations from three biological replicates are illustrated as lighter shading above and below the induction kinetics curve. (B) Dose response of C. necator H16 harboring the l-arabinose-, l-rhamnose-, acrylate-, and cumate-inducible systems four (square) and eight (circle) hours after inducer addition. Error bars represent SDs from three biological replicates.

Regardless of inducer concentration, we noticed that the absolute fluorescence, corrected by fluorescence that derives from basal promoter activity, generally increased during the time course of experiment. This was not the case for the acrylate-inducible system. Six hours after inducer addition, the increase in absolute fluorescence output facilitated by acrylate concentrations of 1.25 mM and less was at the same level as mediated by basal PacuRI activity. This behavior is also reflected in its dose-response curve (Fig. 3B). Normalized fluorescence values for acrylate concentrations of 1.25 mM and less were lower after 8 h of induction than that after 4 h, whereas the increase in the acrylate concentration enabled extended expression of the reporter gene. We hypothesized that this type of transient gene expression can be caused by inducer degradation. To test whether acrylate is catabolized by C. necator H16, a metabolite consumption assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. As predicted, acrylate was coconsumed simultaneously with the primary carbon source fructose (Fig. S4). Four hours after supplementation with 5 mM acrylate, 49% of the initial amount was consumed. Upon depletion of inducer, gene expression was maintained at the level of basal promoter activity. Neither of the other three inducers, l-arabinose, l-rhamnose, or cumate, appeared to be consumed. C. necator H16 was not able to grow in MM supplemented with these three inducers as the sole carbon source (data not shown).

In addition to their dynamic range, another important characteristic of inducible systems is their induction factor. It was calculated for cells in exponential growth phase, 6 h after the inducer was supplemented. Dividing the maximum normalized fluorescence resulting from the highest inducer concentration by the normalized fluorescence of the uninduced sample yielded induction factors of 1,232, 1,960, 33, and 22 for the l-arabinose-, l-rhamnose-, acrylate-, and cumate-inducible systems, respectively. The induction factors that were achieved by AcuR/PacuRI and CymR/Pcmt were much lower than for the two positively regulated systems due to high background levels of reporter gene expression in the absence of inducer (Fig. 4). The order from the highest to the lowest normalized absolute fluorescence achieved by the four tested systems throughout the time course of experiment for the highest inducer concentration is as follows: l-arabinose > l-rhamnose > acrylate > cumate. The same order applies to the maximum possible RFP synthesis rate, with l-arabinose demonstrating the highest value (Table S3). All of the systems can be considered to activate reporter gene transcription immediately after inducer addition. Fluorescence above background levels could be detected within 30 min, representing the time which is required for RFP production and maturation (45).

FIG 4.

Induction dynamics for the l-arabinose-, l-rhamnose-, acrylate-, and cumate-inducible systems. Shown is normalized absolute fluorescence of C. necator H16 harboring the l-arabinose-, l-rhamnose-, acrylate-, and cumate-inducible systems. Fluorescence was determined for cells in exponential growth phase 6 h after inducer addition. Inducer concentrations are indicated for each system. The standard deviations from three biological replicates are illustrated as lighter shading above and below the dynamics curve.

To evaluate the influence of the T7g10 mRNA stem-loop structure sequence on inducible gene expression, it was removed from the plasmid containing the l-arabinose-inducible system. The relationship between fluorescence response and inducer concentration for the l-arabinose-inducible system without the stem-loop structure sequence was similar to the construct harboring the stem-loop (Fig. S5). A linear fluorescence output was achieved by addition of l-arabinose from 0.313 to 2.5 mM. The induction factor was considerably higher (2,900-fold), mainly due to an 8-fold lower background level of RFP synthesis. However, removing the stem-loop also decreased absolute normalized fluorescence levels 3.6-fold at an inducer concentration of 10 mM (Fig. 4; see also Fig. S5).

Assembly and quantitative evaluation of RBS library.

Similarly to the promoter, an RBS has a large impact on the protein synthesis level and, therefore, can govern compound biosynthesis in engineered microorganisms. To balance quantities of enzymes in a metabolic pathway, use of RBSs with variable strengths can help achieve different levels of protein synthesis from individual genes that are organized in a single operon and transcribed from the same promoter.

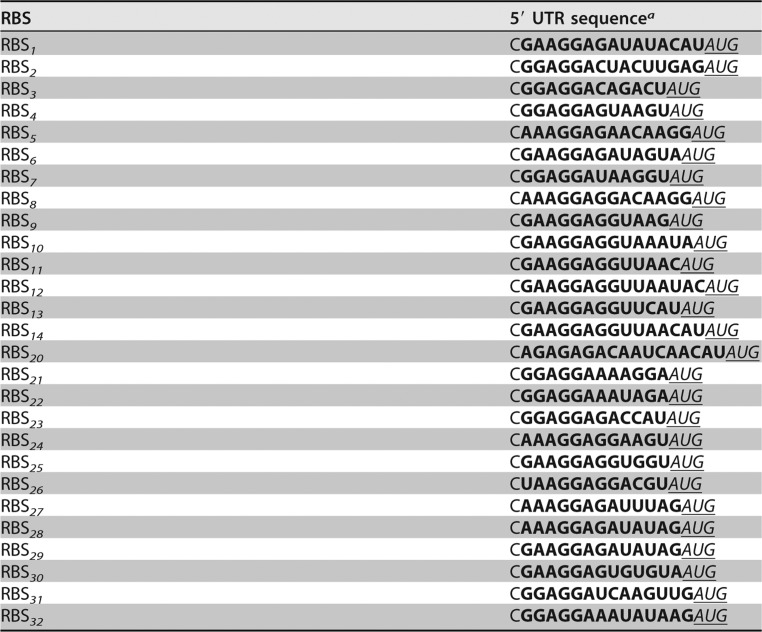

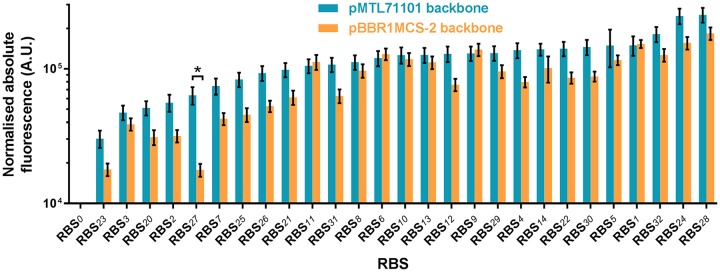

In this study, we used an RBS calculator (46) to develop a range of RBSs with variable strengths (Table 2). Employing the USER-based method similarly to the constitutive promoter library, 27 RBS sequences were assembled in two alternative vector backbones, pBBR1MCS-2 and pMTL71101, under the control of the phaC promoter (Fig. 1C). Resulting constructs were transformed into C. necator H16. The RBS strengths were evaluated by measuring the single time point fluorescence of cells in exponential growth phase (Fig. 5). A majority of RBSs showed similar activities in the two pBBR1MCS-2 and pMTL71101 vector backbones, exhibiting more than a 10-fold dynamic range. Only one RBS variant (RBS27) showed a significantly (P < 0.05) lower fluorescence output in the pBBR1MCS-2 vector backbone than that in pMTL71101.

TABLE 2.

RBSs with variable strengths

aThe unique RBS is in bold, and the gene start codon AUG is in italic and underlined. UTR, untranslated region.

FIG 5.

Quantitative evaluation of RBSs. The strengths of different RBSs were evaluated by using the fluorescence reporter. C. necator H16 cells harboring the variants of RBS-reporter constructs in either pBBR1MCS-2 or pMTL71101 backbone were grown in MM as described in Materials and Methods. To determine normalized absolute fluorescence, the optical density at 600 nm and EYFP fluorescence were measured. Error bars represent standard deviations from three biological replicates. The asterisk indicates statistically significant difference between RBS strengths in different vector backbones for (P < 0.05, unpaired t test).

It should be noted that the activity of an RBS can vary extensively depending on the sequence context (21). To assess this, three selected RBSs—weak (RBS2), medium (RBS8), and strong (RBS1)—were evaluated using constructs containing combinations of upstream (promoter) and downstream (reporter) genetic elements, including eyfp, driven by the PphaC, P1, or PrhaBAD promoter, and rfp, driven by PphaC. As expected, the change from medium-strength PphaC to the strong P1 promoter contributed to the overall increase in gene expression but had little effect on the relative strength of the three cognate RBSs, displaying unchanged hierarchy of strengths RBS1 > RBS8 > RBS2 (Fig. S6A). Strikingly, the downstream change of genetic element (rfp gene) had a more pronounced effect on the relative strength of RBSs, significantly increasing it for RBS1 and RBS8 but not for RBS2 (Fig. S6B). These findings suggest that variable-strength RBSs can aid in achieving differential levels of protein synthesis. However, depending on the genetic context, the absolute levels of gene expression should be fine-tuned by testing a range of RBS alternatives.

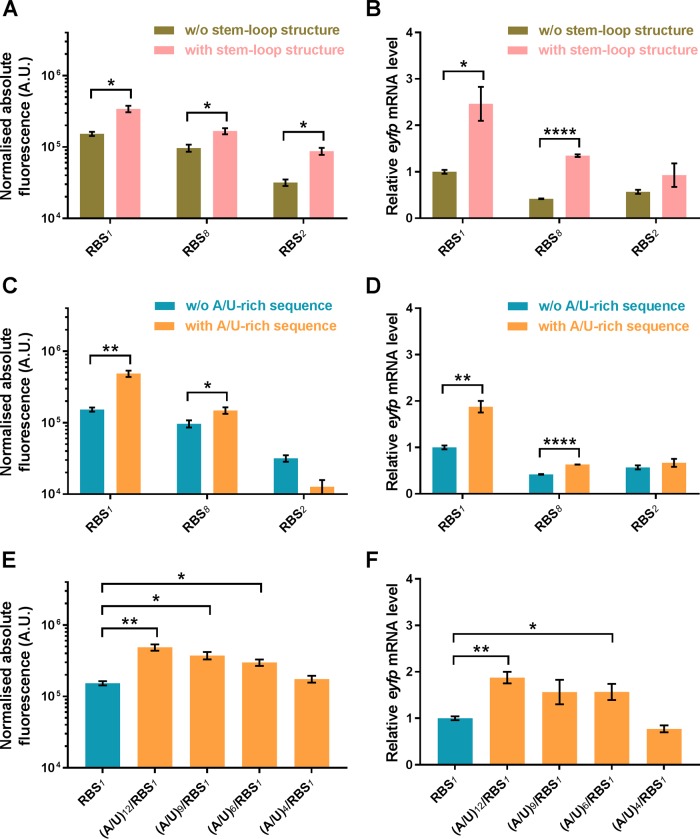

mRNA stem-loop structure and A/U-rich sequence.

An mRNA stem-loop structure and A/U-rich sequence have been reported previously to increase mRNA stability and/or translation efficiency, contributing to improved gene expression in E. coli (22, 23, 43). To test this in C. necator, the T7g10 mRNA stem-loop structure (43) and different-length A/U-rich sequences were inserted upstream to the SD sequence of the RBS. The introduction of the stem-loop structure increased fluorescent reporter protein synthesis 1.5- to 3-fold for constructs with all three RBSs (Fig. 6A), whereas the A/U-rich sequence exhibited a significant increase only in case of the construct with RBS1 (Fig. 6C). The stepwise lengthening of an A/U-rich sequence from 4 to 12 nucleotides resulted in a linear increase of reporter protein synthesis (Fig. 6E). Moreover, the introduction of either mRNA stem-loop structure or A/U-rich sequence contributed to mRNA stabilization (Fig. 6B, D, and F). Overall, these data suggest that depending on the RBS sequence context, A/U-rich sequences can be applied as genetic elements for altering and fine-tuning gene expression, whereas the mRNA stem-loop structure can be used as a universal gene expression enhancer in C. necator H16.

FIG 6.

Effect of upstream mRNA stem-loop structure and A/U-rich sequence on translational activity and mRNA abundance. The translational activities of three different RBSs (RBS1, RBS2, and RBS8) with and without upstream T7g10 mRNA stem-loop structure sequence (A), with and without upstream A/U-rich sequence (C), and with upstream A/U-rich sequences of different lengths (E) were evaluated by using the EYFP fluorescence reporter. To determine normalized absolute fluorescence, the optical density at 600 nm and EYFP fluorescence were measured. The mRNA abundance from constructs with and without upstream T7g10 mRNA stem-loop structure sequence (B), with and without upstream A/U-rich sequence (D), and with upstream A/U-rich sequences of different lengths (F) were measured by RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars represent standard deviations from three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant increase in translational activity or eyfp mRNA abundance in the presence of stem-loop structure (A and B) or A/U-rich (C to F) sequences as follows: *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001; and ****, P < 0.00001 (unpaired t test).

Control of isoprene biosynthesis using inducible promoters and RBS variants.

Gene expression can result in different output patterns for reporter molecules and metabolites. To evaluate how the variation in gene expression can affect product biosynthesis, a simple, one-enzymatic-reaction pathway extension based on a single gene addition was chosen as a suitable model for investigation. Among several potential targets particularly relevant to the industrial application, production of isoprene using isoprene synthase (IspS) emerged as the most significant. IspS has been demonstrated previously to catalyze production of isoprene from dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) (47, 48), which in C. necator can be produced via the 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate/1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate (MEP/DOXP) pathway. Notably, due to the poor catalytic properties of the enzyme (high Km and low kcat), isoprene synthase is considered one of key bottlenecks in isoprene biosynthesis (49).

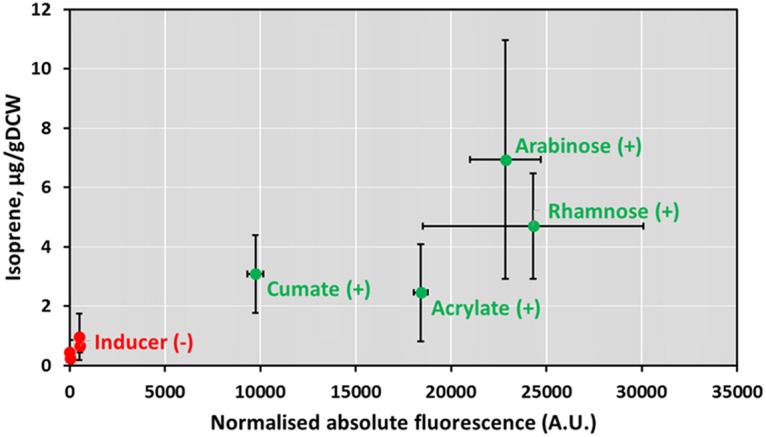

First, to establish whether production of isoprene can be achieved in C. necator H16, and to investigate how gene expression of the enzyme (isoprene synthase) translates into the product of enzymatic reaction (isoprene), Populus alba ispS under the control of two positively (AraC/ParaBAD and RhaRS/PrhaBAD) and two negatively (AcuR/PacuRI and CymR/Pcmt) regulated inducible systems was introduced into C. necator on a plasmid. Induction of ispS expression with l-arabinose, l-rhamnose, acrylate, or cumate confirmed that isoprene was biosynthesized to different levels, resulting in a yield up to 7 μg/g of cells (dry weight) (Fig. 7). Moreover, the isoprene yield showed a moderate positive linear correlation with gene expression (measured as fluorescence output) of corresponding inducible systems (r = 0.625; only data of induced samples were used in the analysis).

FIG 7.

Correlation between gene expression levels and isoprene yields using l-rhamnose-, l-arabinose-, acrylate-, and cumate-inducible systems. Normalized absolute fluorescence of C. necator H16 strains carrying l-rhamnose (RhaRS/PrhaBAD)-, l-arabinose (AraC/ParaBAD)-, acrylate (AcuR/PacuRI)-, and cumate (CymR/Pcmt)-inducible systems is plotted against isoprene yield, resulting from strains carrying the ispS gene under the control of corresponding inducible systems, in the presence [(+), green dots] or absence [(−), red dots] of inducers. The plotted values represent the normalized fluorescence 6 h and isoprene yield 18 h after induction with 1.25 mM l-rhamnose, 1.25 mM l-arabinose, 0.5 mM acrylate, or 3.13 μM cumate. Error bars represent standard deviations from three biological replicates.

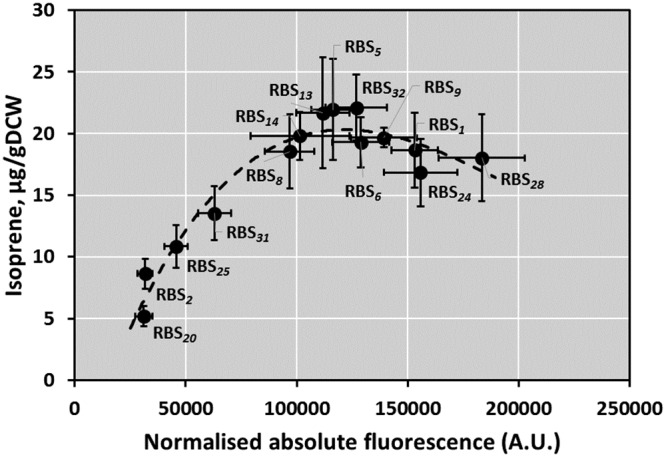

Second, to evaluate how the designed RBSs can be applied for fine-tuning of gene expression in biotechnology applications and how metabolite production correlates with the translational efficiency, ispS was cloned under the control of the PphaC promoter and different RBS variants. Isoprene production was measured after 24 h of plasmid-transformed C. necator cell growth as described in Materials and Methods. By applying a range of RBS variants to control translation, we were able to explore the relationship between IspS abundance and isoprene production efficiency (Fig. 8). The data revealed that the highest isoprene yield, 22 μg/g of cells (dry weight), was achieved using medium-strength RBSs, whereas an additional increase in the level of ispS expression did not contribute to the further improvement of isoprene production and could potentially have an adverse effect.

FIG 8.

Impact of increase in the strength of RBS on isoprene production. Normalized absolute fluorescence of C. necator H16 strains carrying set of plasmids (pBBR1MCS-2-RBSx-ispS) with ispS gene under the control of the phaC promoter and different RBSs is plotted against isoprene yield. Error bars represent standard deviations from three biological replicates.

DISCUSSION

Recently, the use of C. necator as a metabolic engineering chassis and biosynthesis host has received renewed interest from academic and industry researchers for its potential to produce proteins, chemicals, and fuels (11, 17, 50). Ability to fix CO2 and opportunity to redirect carbon flux from PHB to alternative chemicals open opportunities for use of C. necator in biotechnology applications. However, for production of biotechnology-relevant compounds, the engineering of C. necator is often required, involving genome alterations either by adjusting gene expression or by introducing heterologous genes, in both cases utilizing functional genetic elements that contribute to gene expression control.

The application of functional genetic elements for controlling gene expression has proven useful in metabolic engineering, particularly when building biosynthetic pathways and fine-tuning cellular metabolism. At the same time, achieving distinctive steady-state levels of gene product has been shown to play a critical role for optimal function of the pathway or whole metabolic network (51). Steady-state levels of gene expression can be controlled by using promoters of different strengths, for regulating transcriptional levels, and RBSs, for managing translational efficiency (52). Notably, a substantial amount of research has been dedicated to characterization of promoter and RBS variants in biotechnology-relevant bacterial chassis (21, 26, 53–56).

Building on previous studies with E. coli and bacteriophages (36–38), we quantitatively evaluated a set of variable-strength constitutive promoters composed of −35 and −10 sequences with upstream and downstream insulation. By using the latter, the influence of genomic context can be reduced, as demonstrated previously (39). This concept was supported by a high level of correlation between experimental data of this study and previously reported strengths for a small set of promoters (20). Within our library, promoters were identified with strength spanning a >700-fold dynamic range. At least four promoter variants possessed a higher activity than the strongest promoter currently characterized for C. necator H16, Pj5 (20).

Several heterologous inducible promoters, including l-arabinose, m-toluic acid, lactose, 3-hydroxypropionic acid, and l-rhamnose, have been individually characterized previously (16, 27–29). In this study, we have taken a more systematic approach, by evaluating two positively (l-arabinose and l-rhamnose) and two negatively (acrylate and cumate) regulated inducible systems using standardized experimental conditions. In our experimental design and using MM, the positively regulated inducible systems exhibited a tighter control of gene expression than the negatively regulated ones. The highest induction level was achieved using the l-arabinose-inducible system, whereas the l-rhamnose-inducible system exhibited the highest induction factor. The acrylate- and cumate-inducible systems showed significantly lower induction and higher background levels. The application of the acrylate-inducible system in C. necator is limited due to consumption of acrylate by this bacterium. l-Arabinose-, l-rhamnose-, and cumate-inducible systems are suitable for continuous activation of gene expression as well as biosensors. Notably, the cumate-inducible system appeared to be most sensitive, responding to the nanomolar to micromolar range of inducer concentrations. Overall, the systems' dose-response curves are consistent with data from previous induction experiments with C. necator and E. coli (29, 31, 57). However, even though the induction factor of the l-arabinose-inducible system corresponded to the one obtained using sodium gluconate as a carbon source (28), induction factors of the two positively regulated systems were higher than in other studies published so far (16, 27, 29). This variation exemplifies the importance of standardized experimental conditions and comparative studies.

The mRNA secondary structure as well as nucleotide sequence composition, such as the A/U-rich sequence, can also contribute significantly to gene expression regulation. The introduction of A/U-rich sequences into the RBS, upstream of the SD sequence, increases translational efficiency and the stability of mRNA in E. coli, which is thought to result from improved 30S ribosomal subunit binding to the RBS sequence, accelerating recruitment of the ribosome (22). On the other hand, A/U-rich regions have been shown to be a target for RNase E that initiates a decay of mRNA (58). These observations can be explained by two alternative rationales that are, however, not mutually exclusive: (i) the A/U-rich sequence reduces the probability of forming mRNA secondary structures in the translation initiation region, facilitating ribosome binding, which, in turn, hinders both RNase E access to and cleavage of A/U-rich sequence, and (ii) 30S ribosomal protein S1, contributing to the 30S/mRNA interaction, protects from RNase E cleavage and accelerates recruitment of the ribosome. In C. necator H16, we observed that the inclusion of an A/U-rich sequence in the RBS region has a positive effect on gene expression, contributing to increased translational efficiency and the stability of mRNA. Notably, C. necator possesses both the gene rpsA (locus tag H16_A0798), encoding protein S1 with 67% identity (94% coverage) to the E. coli K-12 homologue, and the genes cafA1 and cafA2 (locus tags H16_A0909 and H16_A2580), encoding potential RNase E/G superfamily members with 38% identity (42% coverage) and 52% identity (67% coverage), respectively, to the E. coli K-12 homologues. These results underline existing similarities of gene expression control between members of gammaproteobacteria (E. coli) and betaproteobacteria (C. necator).

The application of inducible systems and selection of RBSs to control isoprene production revealed that it is important to fine-tune the gene expression to the specific level in order to achieve the optimal yield of isoprene. C. necator H16 cells transformed with plasmids harboring the ispS gene under the control of medium-strength RBS yielded the highest isoprene production, while further increases in gene expression resulted in no further increase and even decreases in levels of the product. This was somewhat surprising, since the gene expression data using fluorescence reporter showed that the increase in strength of RBS translated to higher yields of protein. The observed limitation in the isoprene production can be explained by several lines of reasoning: (i) if the overproduction of isoprene synthase is toxic, cells can potentially reduce this effect by either turning down expression or increasing degradation of IspS protein; (ii) due to the inherently high Km of IspS, the reduced availability of substrate can become a limiting factor in the biosynthesis of isoprene (49, 59); (iii) since isoprene synthase competes with geranyl pyrophosphate synthase and farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase for DMAPP, the overexpression of IspS can cause a depletion of prenyl phosphates (e.g., undecaprenyl phosphate) required for biosynthesis of various cell wall polymers (60); (iv) as it has been previously reported that isoprene synthase forms inclusion bodies when overexpressed (49), protein aggregation can inhibit the enzymatic activity of IspS.

To conclude, the previous work has delivered a limited toolbox of functional genetic elements suitable for application in the metabolic engineering of C. necator. In this study, we have quantitatively evaluated and compared an array of new genetic elements, including constitutive and inducible promoters, RBSs, mRNA stem-loop structure, and A/U-rich sequences, expanding the choice of tools. Our quantitative results will inform design and engineering of synthetic pathways and genetic circuitry in C. necator H16 and other related bacterial species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

C. necator H16 (DSMZ-428, ATCC 17669) was purchased from DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany) and used in all experiments, including fluorescence assays, RNA isolation, and isoprene production, as described in the following sections. E. coli TOP10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used for cloning and plasmid propagation.

Oligonucleotides, chemicals, and enzymes.

Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by Eurofins Genomics (Ebersberg, Germany) and are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. l-(+)-Arabinose (99% purity; Acros Organics, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA; catalogue no. 365181000), l-rhamnose monohydrate (≥99% purity; Sigma-Aldrich, USA; catalogue no. R3875), magnesium acrylate (95% purity; Alfa Aesar, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA; catalogue no. 42002; lot no. L14619), 4-isopropylbenzoic acid (cumic acid; ≥98% purity; Acros Organics, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA; catalogue no. 412800050), and d-(−)-fructose (≥99% purity; Sigma-Aldrich, USA; catalogue no. F0127) were used as inducers for assaying inducible systems or substrates in metabolite consumption assays. Isoprene (99% purity; Alfa Aesar, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA; catalogue no. L14619) was used as a standard for isoprene yield quantification. Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs (USA).

Plasmid construction. (i) Insulated constitutive promoter and RBS libraries.

The core promoter sequences used to construct the library of insulated constitutive promoters are listed in Table 1. The following is an example of insulated promoter sequence: promoter P15, GCTGAGGGAAAGTACCCAAAAATTCATCCTTCTCGCCTATGCTCTGGGGCCTCGGCAGATGCGAGCGCTGCATACCGTCCGGTAGGTCGGGAAGCGTGCAGTGCCGAGGCGGATTAATCGATttgacagctagctcagtcctaggtactgtgctagcaacctGAATTCACTAGTTTAACTTTAAGAA. The insulations preceding (122 bases) and following (25 bases) the core promoter are both shown in uppercase and are partially derived from the upstream region of the phaC promoter and upstream nucleotide sequence of the T7 gene 10 RBS, respectively. For each insulated promoter, only the core sequence (in lowercase), including the −35 and −10 hexamers (underlined), up to 12 bases upstream of the −35 box, the 17-base spacer between the −35 and −10 boxes, and up to 20 bases downstream of the −10 box, vary between library members (Table 1). The expected transcription start site is in bold.

Plasmids with insulated constitutive promoters and RBS variants (Table 2) were constructed using the uracil-specific excision reagent (USER) method as described previously (33). In order to generate the USER-compatible vector, a DNA cassette containing lacZα (for blue-white color screening of colonies) flanked by inversely oriented nicking endonuclease Nt.BbvCI sites and restriction endonuclease XbaI sites was synthesized by PCR using oligonucleotide primers P001 and P002 and pGEM-T plasmid (Promega) as a DNA template. To exclude any possible transcriptional readthrough, rrnB terminator T2 (5′-AAATTAAGCAGAAGGCCATCCTGACGGATGGCCTTTTTGCGTTT-3′) and truncated version of terminator T1 (5′-ATCAAATAAAACGAAAGGCCTTCGGGCCTTTCGTTTTATCTGTTGTTT-3′) (61) were inserted upstream and downstream, respectively, of the cassette flanked by Nt.BbvCI sites. Within the cassette, each XbaI site was separated from the adjacent Nt.BbvCI site by unique, 5-nucleotide-long spacer sequences, GAAAG and TGTCT. The PCR fragment containing the USER cassette was digested with KpnI and AgeI and cloned into pBBR1MCS-2-PphaC-eyfp-c1 (62). The resulting plasmid, pBBR1MCS-2-USER, was used to excise the KpnI-NheI DNA fragment including the USER cassette. This DNA fragment was also subcloned into modular vector pMTL71101 (see Fig. S1 and Materials and Methods in the supplemental material) through KpnI and NheI restriction sites, yielding plasmid pMTL71107.

All insulated constitutive promoters and RBSs were assembled in vectors pBBR1MCS-2-USER and pMTL71107 by employing the USER method. For this purpose, two overlapping DNA fragments, including promoter, RBS and eyfp gene sequences, were generated by PCR with two pairs of oligonucleotide primers, P003 with P005_pX_r (or P007_rbsX_r; “p” and “rbs” represent promoter and RBS, respectively, while “X” is the corresponding number of the promoter or RBS) and P006_pX_f (or P008_rbsX_f) with P004 using plasmid pBBR1MCS-2-PphaC-eyfp-c1 as a template. The overlapping primers, P005_pX_r (or P007_rbsX_r) and P006_pX_f (or P008_rbsX_f), were designed in such a way so that the desired promoter (or RBS sequence) is integrated into the primer sequence. The resulting plasmids with promoter and RBS variants are referred to as pBBR1MCS-2-P0 to pBBR1MCS-2-P25 and pBBR1MCS-2-RBS0 to pBBR1MCS-2-RBS32 in the pBBR1MCS-2 vector backbone and as pMTL71107-P0 to pMTL71107-P25 and pMTL71107-RBS0 to pMTL71107-RBS32 in the pMTL71107 vector backbone.

For use as negative controls, the promoterless construct P0 and SD sequence-free construct RBS0 (including the complement SD sequence) were generated. P0 was assembled from the DNA fragment that was PCR amplified using oligonucleotide primers P006_p0_f and P004 from pBBR1MCS-2-PphaC-eyfp-c1 and was cloned into either the pBBR1MCS-2-USER or pMTL71107 vector. The assembly of RBS0 involved two overlapping DNA fragments generated by PCR with two pairs of primers, P003-P007_rbs0_r and P008_rbs0_f-P004, using same template as described above.

(ii) mRNA stem-loop and A/U-rich sequence variants.

To construct plasmids pBBR1MCS-2-SL/RBS1, pBBR1MCS-2-SL/RBS2, and pBBR1MCS-2-SL/RBS8, containing RBS variants with upstream T7g10 mRNA stem-loop (43) (SL), primer P007_SL/rbs_r overlapping with primers P008_SL/rbs1_f, P008_SL/rbs2_f, and P008_SL/rbs8_f were used, respectively. The plasmids pBBR1MCS-2-(A/U)12/RBS1, pBBR1MCS-2-(A/U)9/RBS1, pBBR1MCS-2-(A/U)6/RBS1, and pBBR1MCS-2-(A/U)4/RBS1, bearing RBS variants with A/U-rich (A/U) sequences, were generated using corresponding primers P007_(A/U)12/rbs1_r, P007_(A/U)9/rbs1_r, P007_(A/U)6/rbs1_r and P007_(A/U)4/rbs1_r, which all overlapped with primer P008_rbs1_f. The use of primers P007_(A/U)12/rbs2_r and P007_(A/U)12/rbs8_r overlapping with primers P008_rbs2_f and P008_rbs8_f allowed construction of plasmids pBBR1MCS-2-(A/U)12/RBS2, and pBBR1MCS-2-(A/U)12/RBS8, respectively.

(iii) Inducible systems.

The inducible systems were cloned into the C. necator-E. coli shuttle vector pEH006 (28), based on the modular vector system which has been developed previously (63). All constructed plasmids contained following functional modules: (i) a broad-host-range pBBR1 origin of replication (34), (ii) antibiotic (chloramphenicol or kanamycin) resistance gene, and (iii) promoter/RBS-reporter gene (eyfp or rfp) fusion. The utilization of restriction sites for rare-cutter enzymes SbfI, PmeI, FseI, and AscI made these functional modules interchangeable (63) for pMTL71107- and pEH006-derived plasmids.

The l-rhamnose-inducible system RhaRS/PrhaBAD was amplified with oligonucleotide primers EH007_f and EH008_r from pJOE7784.1 (64) and cloned into pEH006 by AatII and XbaI restriction sites, resulting in pEH002.

pEH005 served as the backbone for assembly of negatively regulated systems. It is the same vector as pEH006 except for two elements. Instead of an rrnb terminator, T1, downstream of the inducible system's transcriptional regulator, it contains an rrnb terminator, T2. Furthermore, the l-arabinose-inducible system was replaced by Plac-tetR and PtetA. It was assembled by using the NEBuilder Hifi DNA assembly method. Oligonucleotide primers EH025_f and EH026_r, EH027_f and EH028_r were used to amplify the vector backbone and tetR from pEH006 and pJOE7801.1 (64), respectively. Primer overhangs were designed to contain rrnb terminator T2 and a PvuI restriction site to be able to replace the incorporated lac promoter.

The vector containing the acrylate-inducible system, pEH020, was assembled by using the NEBuilder Hifi DNA assembly method. Oligonucleotide primers EH048_f and EH057_r and primers EH056_f and EH055_r were used to amplify the vector backbone for negatively regulated systems and the acrylate inducible system (40) from pEH005 and Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 genomic DNA, respectively.

The vector containing the cumate-inducible system, pEH040, was assembled by using the NEBuilder Hifi DNA assembly method. Oligonucleotide primers EH048_f and EH012_r, EH011_f and EH109_r, EH112_f and EH111_r, and EH114_r and EH113_f were used to amplify the vector backbone for negatively regulated systems, the transcriptional regulator cymR, and the cumate-inducible promoter Pcmt from pEH005 and pNEW (44), respectively.

The l-arabinose-inducible system without the T7g10 stem-loop structure was amplified with oligonucleotide primers EH310_f and EH016_r from E. coli MG1655 genomic DNA and cloned into pEH006 by AatII and NdeI restriction sites, resulting in pEH176.

(iv) Plasmids for isoprene production.

Plasmids harboring codon-optimized Populus alba isoprene synthase gene (ispS; sequence can be found in Materials and Methods in the supplemental material) under the control of either different RBS variants or inducible systems were used for isoprene production. To construct pBBR1MCS-2-RBSx-ispS series with RBS variants (“x” is the corresponding number of RBSs), eyfp was replaced with ispS gene through restriction sites NdeI and BamHI or by the USER method. To construct plasmids for isoprene production using l-rhamnose-, l-arabinose-, acrylate-, and cumate-inducible systems, rfp was replaced with ispS through restriction sites NdeI and BamHI for plasmids pEH002, pEH006, and pEH020 and through NdeI and AflII for plasmid pEH040, resulting in pEH002-ispS, pEH006-ispS, pEH020-ispS, and pEH040-ispS, respectively. The DNA fragment containing ispS was prepared by either restriction digestion of plasmid pBBR1MCS-2-RBS1-ispS with NdeI and BamHI or by PCR amplification using plasmid pBBR1MCS-2-RBS1-ispS as a template and oligonucleotide primers P009_ispS_f and P010_ispS_r, followed by restriction digestion with NdeI and AflII.

All plasmids constructed in this work were verified by Sanger sequencing and listed in Table S2.

Fluorescence measurements.

For single time point fluorescence measurements, plasmid-transformed C. necator H16 cells were grown in minimal medium (MM) (65) with 4 mg/ml of fructose and 300 μg/ml of kanamycin at 30°C. Cells forming fresh single colonies were inoculated into 2 ml of medium and grown overnight. Ten microliters of overnight culture was added to 390 μl of medium in a 96-deep-well plate (2.0 ml, round wells with round bottoms; STARLAB International GmbH, Germany; catalogue no. E2896-2110) and grown for 24 h. Subsequently, 20 μl of cell culture was subcultured into 380 μl of fresh medium and grown for up to 24 h in a 96-deep-well plate. A total of 150 μl of cell culture in exponential growth phase was transferred into a 96-well microtiter plate (flat and clear bottom, black; Greiner One International, Germany; catalogue no. 655090). The fluorescence was measured in an Infinite M1000 PRO (Tecan, Switzerland) plate reader by using a fluorescence bottom reading mode. For eYFP fluorescence measurement, an excitation wavelength of 495 nm with a 10-nm bandwidth, an emission wavelength of 530 nm with a 10-nm bandwidth, and gain were manually set to 65%. To normalize fluorescence by optical cell density, absorbance was measured using wavelength of 600 nm with a 5-nm bandwidth at the same time. RFP fluorescence was measured using 585 nm as the excitation wavelength and 620 nm as the emission wavelength. The gain factor was set manually to 80%. Time course fluorescence measurements were performed in MM with 4 mg/ml of fructose as the carbon source as described previously (28).

Normalized relative fluorescence and fluorescent protein synthesis rate.

Relative normalized fluorescence values were calculated to display the fluorescence output of the four evaluated inducible systems on a common axis. This was performed by dividing absolute normalized fluorescence values by 110% of the highest value achieved during the time course of experiment.

The normalized absolute fluorescence values were used to calculate the RFP synthesis rate for each inducer concentration at any time as reported previously (57). The resulting maximum synthesis rate was fit to the corresponding inducer concentration using the Hill function:

| (1) |

The parameters correspond to the time (t), the maximum RFP synthesis rate (vmax), the inducer concentration (I), the Hill coefficient (h), the inducer concentration that results in half-maximal RFP synthesis (Km), and the basal rate of RFP synthesis (vmin). The fitted data for each system are illustrated in Fig. S2. The resulting parameters are summarized in Table S3.

RNA preparation and real-time PCR.

The wild-type and plasmid-transformed C. necator H16 strains were grown in MM containing 4 mg/ml of fructose and 300 μg/ml of kanamycin. The cells were subcultured twice and grown aerobically for up to 24 h each time in 50-ml conical centrifuge tubes with orbital shaking at 30°C. Subsequently, the culture volume equivalent to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1 for cells in exponential growth phase was pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 1 min. The pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of TRI reagent (Sigma) and stored at −80°C. RNA was extracted using TRI reagent (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The samples were treated with 2 units of RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega), and 2 μg of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis in a 20-μl reaction volume using the ProtoScript II first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (New England BioLabs). A real-time PCR analysis was performed in a 20-μl reaction volume using LuminoCt SYBR green qPCR ReadyMix (Sigma) and a Light Cycler 480 II (Roche). The relative quantification of mRNA levels was performed using the threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) method (66). All biological samples were assayed in duplicates. Primers used for RT-PCR were P011_16S_f and P012_16S_r (for 16S RNA) and P013_yfp_f and P014_yfp_r (for the eyfp gene).

Isoprene production.

Freshly grown overnight cultures of plasmid-transformed C. necator H16 strains were inoculated to an OD600 of 0.1 into 10 ml of MM containing 4 mg/ml of fructose and 50 μg/ml of chloramphenicol and incubated at 30°C with vigorous shaking in sealed 60-ml serum bottles. For constructs with the ispS gene under the control of inducible promoters, the medium was supplemented with either 1.25 mM l-rhamnose, 1.25 mM l-arabinose, 0.5 mM acrylate, or 3.13 μM cumate. Gas samples from the headspace were taken for isoprene analysis 18 h after induction. Cultures of C. necator H16 strains containing plasmids with different RBS variants and ispS under the control of the constitutive promoter PphaC were sampled after 24 h of growth in sealed 60-ml serum bottles.

Analytical methods.

The cell absorbance was measured in a 1-cm-path-length cuvette using BioMate 3S UV-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometer at 600 nm (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

For isoprene quantification, gas samples were collected from the headspace of sealed 60-ml serum bottles containing 10 ml of culture. Isoprene was detected by gas chromatography (GC) using the instrument Focus GC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) equipped with a flame ionization detector and an HP-AL/S column (30-m length, 0.25-mm diameter; Agilent Technologies). Nitrogen gas was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. The injector, oven, and detector temperatures were maintained at 220°C, 120°C, and 250°C, respectively. The injection volume was 1 ml. The yields of isoprene per gram of cells (dry weight) were estimated from standard curves generated by analyzing known quantities of isoprene. Dry weight was determined by washing cells from a 20-ml culture in distilled water and separation by centrifugation, followed by vacuum-freeze-drying and weighing cell pellet with microbalance.

The metabolite consumption assay was performed as described previously (28). Cells were inoculated to an OD600 of 0.5 in MM supplemented with 20 mM fructose and 5 mM acrylate as carbon sources and allowed to grow for 48 h. Fructose and acrylate concentrations were measured by taking supernatant samples at 0, 2, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h and subjecting them to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) in combination with UV spectroscopy using a Thermo Scientific Ultimate 3000 HPLC system equipped with a Phenomenex Rezex ROA-organic acid H+ (8%) column and a diode array detector with the wavelength set at 210 nm. The concentrations of metabolites in the supernatant were estimated from standard curves generated by analyzing known concentrations of magnesium acrylate and D-(−)-fructose.

Statistical analysis.

The unpaired t test was applied to identify statistically significant differences in the normalized absolute fluorescence and relative mRNA levels. The correction for multiple comparisons was performed using Holm-Sidak method, and alpha level was set at 0.05. The Pearson correlation coefficient r was calculated to establish the degree of linear correlation between two variables (e.g., normalized absolute fluorescence and isoprene yield). The t test and correlation analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism 7.01 built-in equations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC; grant number BB/L013940/1) and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) under the same grant number. We thank The University of Nottingham for providing the SBRC-DTProg Ph.D. studentship to E.K.R.H.

We thank Matthew Abbott and James Fothergill for assistance with HPLC and GC analysis, Carlos Miguez, Josef Altenbuchner, and Jonathan Todd for gifting plasmids pNEW, pJOE7784.1, and pJOE7801.1 and genomic DNA of R. sphaeroides 2.4.1, and all members of the SBRC who helped in carrying out this research.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00878-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reinecke F, Steinbüchel A. 2009. Ralstonia eutropha strain H16 as model organism for PHA metabolism and for biotechnological production of technically interesting biopolymers. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 16:91–108. doi: 10.1159/000142897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jendrossek D. 2009. Polyhydroxyalkanoate granules are complex subcellular organelles (carbonosomes). J Bacteriol 191:3195–3202. doi: 10.1128/JB.01723-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pohlmann A, Fricke WF, Reinecke F, Kusian B, Liesegang H, Cramm R, Eitinger T, Ewering C, Pötter M, Schwartz E, Strittmatter A, Voß I, Gottschalk G, Steinbüchel A, Friedrich B, Bowien B. 2006. Genome sequence of the bioplastic-producing “Knallgas” bacterium Ralstonia eutropha H16. Nat Biotechnol 24:1257–1262. doi: 10.1038/nbt1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cramm R. 2009. Genomic view of energy metabolism in Ralstonia eutropha H16. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 16:38–52. doi: 10.1159/000142893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukui T, Chou K, Harada K, Orita I, Nakayama Y, Bamba T, Nakamura S, Fukusaki E. 2014. Metabolite profiles of polyhydroxyalkanoate-producing Ralstonia eutropha H16. Metabolomics 10:190–202. doi: 10.1007/s11306-013-0567-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riedel SL, Lu J, Stahl U, Brigham CJ. 2014. Lipid and fatty acid metabolism in Ralstonia eutropha: relevance for the biotechnological production of value-added products. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:1469–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5430-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alagesan S, Minton NP, Malys N. 2018. 13C-assisted metabolic flux analysis to investigate heterotrophic and mixotrophic metabolism in Cupriavidus necator H16. Metabolomics 14:9. doi: 10.1007/s11306-017-1302-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raberg M, Volodina E, Lin K, Steinbüchel A. 2018. Ralstonia eutropha H16 in progress: applications beside PHAs and establishment as production platform by advanced genetic tools. Crit Rev Biotechnol 38:494–510. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2017.1369933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srinivasan S, Barnard GC, Gerngross TU. 2003. Production of recombinant proteins using multiple-copy gene integration in high-cell-density fermentations of Ralstonia eutropha. Biotechnol Bioeng 84:114–120. doi: 10.1002/bit.10756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnard GC, McCool JD, Wood DW, Gerngross TU. 2005. Integrated recombinant protein expression and purification platform based on Ralstonia eutropha. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:5735–5742. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5735-5742.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nybo SE, Khan NE, Woolston BM, Curtis WR. 2015. Metabolic engineering in chemolithoautotrophic hosts for the production of fuels and chemicals. Metab Eng 30:105–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Müller J, MacEachran D, Burd H, Sathitsuksanoh N, Bi C, Yeh YC, Lee TS, Hillson NJ, Chhabra SR, Singer SW, Beller HR. 2013. Engineering of Ralstonia eutropha H16 for autotrophic and heterotrophic production of methyl ketones. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:4433–4439. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00973-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grousseau E, Lu J, Gorret N, Guillouet SE, Sinskey AJ. 2014. Isopropanol production with engineered Cupriavidus necator as bioproduction platform. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:4277–4290. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5591-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HM, Jeon BY, Oh MK. 2016. Microbial production of ethanol from acetate by engineered Ralstonia eutropha. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng 21:402–407. doi: 10.1007/s12257-016-0197-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fei Q, Brigham CJ, Lu J, Fu R, Sinskey AJ. 2013. Production of branched-chain alcohols by recombinant Ralstonia eutropha in fed-batch cultivation. Biomass Bioenergy 56:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2013.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bi C, Su P, Müller J, Yeh YC, Chhabra SR, Beller HR, Singer SW, Hillson NJ. 2013. Development of a broad-host synthetic biology toolbox for Ralstonia eutropha and its application to engineering hydrocarbon biofuel production. Microb Cell Fact 12:107. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crépin L, Lombard E, Guillouet SE. 2016. Metabolic engineering of Cupriavidus necator for heterotrophic and autotrophic alka(e)ne production. Metab Eng 37:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Przybylski D, Rohwerder T, Dilßner C, Maskow T, Harms H, Müller RH. 2015. Exploiting mixtures of H2, CO2, and O2 for improved production of methacrylate precursor 2-hydroxyisobutyric acid by engineered Cupriavidus necator strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:2131–2145. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen JS, Colön B, Dusel B, Ziesack M, Way JC, Torella JP. 2015. Production of fatty acids in Ralstonia eutropha H16 by engineering β-oxidation and carbon storage. PeerJ 3:e1468. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gruber S, Hagen J, Schwab H, Koefinger P. 2014. Versatile and stable vectors for efficient gene expression in Ralstonia eutropha H16. J Biotechnol 186:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mutalik VK, Guimaraes JC, Cambray G, Mai QA, Christoffersen MJ, Martin L, Yu A, Lam C, Rodriguez C, Bennett G, Keasling JD, Endy D, Arkin AP. 2013. Quantitative estimation of activity and quality for collections of functional genetic elements. Nat Methods 10:347–353. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komarova AV, Tchufistova LS, Dreyfus M, Boni IV. 2005. AU-rich sequences within 5′ untranslated leaders enhance translation and stabilize mRNA in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 187:1344–1349. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.4.1344-1349.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dreyfus M. 1988. What constitutes the signal for the initiation of protein synthesis on Escherichia coli mRNAs? J Mol Biol 204:79–94. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90601-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balzer S, Kucharova V, Megerle J, Lale R, Brautaset T, Valla S. 2013. A comparative analysis of the properties of regulated promoter systems commonly used for recombinant gene expression in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact 12:26. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vimberg V, Tats A, Remm M, Tenson T. 2007. Translation initiation region sequence preferences in Escherichia coli. BMC Mol Biol 8:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Englund E, Liang F, Lindberg P. 2016. Evaluation of promoters and ribosome binding sites for biotechnological applications in the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Sci Rep 6:36640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukui T, Ohsawa K, Mifune J, Orita I, Nakamura S. 2011. Evaluation of promoters for gene expression in polyhydroxyalkanoate-producing Cupriavidus necator H16. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 89:1527–1536. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanko E, Minton N, Malys N. 2017. Characterisation of a 3-hydroxypropionic acid-inducible system from Pseudomonas putida for orthogonal gene expression control in Escherichia coli and Cupriavidus necator. Sci Rep 7:1724. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01850-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sydow A, Pannek A, Krieg T, Huth I, Guillouet SE, Holtmann D. 2017. Expanding the genetic tool box for Cupriavidus necator by a stabilized L-rhamnose inducible plasmid system. J Biotechnol 263:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Liao JC. 2015. A synthetic anhydrotetracycline-controllable gene expression system in Ralstonia eutropha H16. ACS Synth Biol 4:101–106. doi: 10.1021/sb4001189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gruber S, Schwendenwein D, Magomedova Z, Thaler E, Hagen J, Schwab H, Heidinger P. 2016. Design of inducible expression vectors for improved protein production in Ralstonia eutropha H16 derived host strains. J Biotechnol 235:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arikawa H, Matsumoto K. 2016. Evaluation of gene expression cassettes and production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) with a fine modulated monomer composition by using it in Cupriavidus necator. Microb Cell Fact 15:184. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0583-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bitinaite J, Rubino M, Varma KH, Schildkraut I, Vaisvila R, Vaiskunaite R. 2007. USER™ friendly DNA engineering and cloning method by uracil excision. Nucleic Acids Res 35:1992–2002. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovach ME, Phillips RW, Elzer PH, Roop RM II, Peterson KM. 1994. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. Biotechniques 16:800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balzer D, Ziegelin G, Pansegrau W, Kruft V, Lanka E. 1992. Korb protein of promiscuous plasmid rp4 recognizes inverted sequence repetitions in regions essential for conjugative plasmid transfer. Nucleic Acids Res 20:1851–1858. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.8.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kosuri S, Goodman DB, Cambray G, Mutalik VK, Gao Y, Arkin AP, Endy D, Church GM. 2013. Composability of regulatory sequences controlling transcription and translation in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:14024–14029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301301110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gentz R, Bujard H. 1985. Promoters recognized by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase selected by function: highly efficient promoters from bacteriophage T5. J Bacteriol 164:70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller ES, Kutter E, Mosig G, Arisaka F, Kunisawa T, Rüger W. 2003. Bacteriophage T4 genome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67:86–156. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.1.86-156.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis JH, Rubin AJ, Sauer RT. 2011. Design, construction and characterization of a set of insulated bacterial promoters. Nucleic Acids Res 39:1131–1141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan MJ, Curson AR, Shearer N, Todd JD, Green RT, Johnston AW. 2011. Unusual regulation of a leaderless operon involved in the catabolism of dimethylsulfoniopropionate in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. PLoS One 6:e15972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hahn S, Schleif R. 1983. In vivo regulation of the Escherichia coli araC promoter. J Bacteriol 155:593–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tobin J, Schleif R. 1987. Positive regulation of the Escherichia coli L-rhamnose operon is mediated by the products of tandemly repeated regulatory genes. J Mol Biol 196:789–799. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mertens N, Remaut E, Fiers W. 1996. Increased stability of phage T7g10 mRNA is mediated by either a 5′- or a 3′-terminal stem-loop structure. Biol Chem 377:811–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi YJ, Morel L, Le François T, Bourque D, Bourget L, Groleau D, Massie B, Míguez CB. 2010. Novel, versatile, and tightly regulated expression system for Escherichia coli strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:5058–5066. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00413-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell RE, Tour O, Palmer AE, Steinbach PA, Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. 2002. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salis HM, Mirsky EA, Voigt CA. 2009. Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat Biotechnol 27:946–950. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silver GM, Fall R. 1991. Enzymatic synthesis of isoprene from dimethylallyl diphosphate in aspen leaf extracts. Plant Physiol 97:1588–1591. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.4.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silver GM, Fall R. 1995. Characterization of aspen isoprene synthase, an enzyme responsible for leaf isoprene emission to the atmosphere. J Biol Chem 270:13010–13016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vickers CE, Sabri S. 2015. Isoprene, p 289–317. In Schrader J, Bohlmann J (ed), Biotechnology of isoprenoids. Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Volodina E, Raberg M, Steinbüchel A. 2016. Engineering the heterotrophic carbon sources utilization range of Ralstonia eutropha H16 for applications in biotechnology. Crit Rev Biotechnol 36:978–991. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2015.1079698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santos CN, Stephanopoulos G. 2008. Combinatorial engineering of microbes for optimizing cellular phenotype. Curr Opin Chem Biol 12:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mutalik VK, Guimaraes JC, Cambray G, Lam C, Christoffersen MJ, Mai QA, Tran AB, Paull M, Keasling JD, Arkin AP, Endy D. 2013. Precise and reliable gene expression via standard transcription and translation initiation elements. Nat Methods 10:354–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guiziou S, Sauveplane V, Chang HJ, Clerte C, Declerck N, Jules M, Bonnet J. 2016. A part toolbox to tune genetic expression in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res 44:7495–7508. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Markley AL, Begemann MB, Clarke RE, Gordon GC, Pfleger BF. 2015. Synthetic biology toolbox for controlling gene expression in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002. ACS Synth Biol 4:595–603. doi: 10.1021/sb500260k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siegl T, Tokovenko B, Myronovskyi M, Luzhetskyy A. 2013. Design, construction and characterisation of a synthetic promoter library for fine-tuned gene expression in actinomycetes. Metab Eng 19:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pogrebnyakov I, Jendresen CB, Nielsen AT. 2017. Genetic toolbox for controlled expression of functional proteins in Geobacillus spp. PLoS One 12:e0171313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rogers JK, Guzman CD, Taylor ND, Raman S, Anderson K, Church GM. 2015. Synthetic biosensors for precise gene control and real-time monitoring of metabolites. Nucleic Acids Res 43:7648–7660. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaberdin VR, Bläsi U. 2006. Translation initiation and the fate of bacterial mRNAs. FEMS Microbiol Rev 30:967–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oku H, Inafuku M, Ishikawa T, Takamine T, Ishmael M, Fukuta M. 2015. Molecular cloning and biochemical characterization of isoprene synthases from the tropical trees Ficus virgata, Ficus septica, and Casuarina equisetifolia. J Plant Res 128:849–861. doi: 10.1007/s10265-015-0740-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bouhss A, Trunkfield AE, Bugg TD, Mengin-Lecreulx D. 2008. The biosynthesis of peptidoglycan lipid-linked intermediates. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:208–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Orosz A, Boros I, Venetianer P. 1991. Analysis of the complex transcription termination region of the Escherichia coli rrnB gene. Eur J Biochem 201:653–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pfeiffer D, Jendrossek D. 2011. Interaction between poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) granule-associated proteins as revealed by two-hybrid analysis and identification of a new phasin in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Microbiology 157:2795–2807. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.051508-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heap JT, Pennington OJ, Cartman ST, Minton NP. 2009. A modular system for Clostridium shuttle plasmids. J Microbiol Methods 78:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoffmann J, Altenbuchner J. 2015. Functional characterization of the mannitol promoter of Pseudomonas fluorescens DSM 50106 and its application for a mannitol-inducible expression system for Pseudomonas putida KT2440. PLoS One 10:e0133248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schlegel HG, Kaltwasser H, Gottschalk G. 1961. Ein Submersverfahren zur Kultur wasserstoffoxydierender Bakterien: Wachstumsphysiologische Untersuchungen. Arch Mikrobiol 38:209–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Peccoud J, Anderson JC, Chandran D, Densmore D, Galdzicki M, Lux MW, Rodriguez CA, Stan GB, Sauro HM. 2011. Essential information for synthetic DNA sequences. Nat Biotechnol 29:22. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reese MG. 2001. Application of a time-delay neural network to promoter annotation in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Comput Chem 26:51–56. doi: 10.1016/S0097-8485(01)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.