Abstract

Ethnopharmacological relevance

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a multifactorial neurodegenerative disorder affecting 5% of the population over the age of 85 years. Current treatments primarily involve dopamine replacement therapy, which leads to temporary relief of motor symptoms but fails to slow the underlying neurodegeneration. Thus, there is a need for safe PD therapies with neuroprotective activity. In this study, we analyzed contemporary herbal medicinal practices used by members of the Pikuni-Blackfeet tribe from Western Montana to treat PD-related symptoms, in an effort to identify medicinal plants that are affordable to traditional communities and accessible to larger populations.

Aim of the study

The aims of this study were to (i) identify medicinal plants used by the Pikuni-Blackfeet tribe to treat individuals with symptoms related to PD or other CNS disorders, and (ii) characterize a subset of the identified plants in terms of antioxidant and neuroprotective activities in cellular models of PD.

Materials and Methods

Interviews of healers and local people were carried out on the Blackfeet Indian reservation. Plant samples were collected, and water extracts were produced for subsequent analysis. A subset of botanical extracts was tested for the ability to induce activation of the Nrf2-mediated transcriptional response and to protect against neurotoxicity elicited by the PD-related toxins rotenone and paraquat.

Results

The ethnopharmacological interviews resulted in the documentation of 19 medicinal plants used to treat various ailments and diseases, including symptoms related to PD. Seven botanical extracts (out of a total of 10 extracts tested) showed activation of Nrf2-mediated transcriptional activity in primary cortical astrocytes. Extracts prepared from Allium sativum cloves, Trifolium pratense flowers, and Amelanchier arborea berries exhibited neuroprotective activity against toxicity elicited by rotenone, whereas only the extracts prepared from Allium sativum and Amelanchier arborea alleviated PQ-induced dopaminergic cell death.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the potential clinical utility of plants used for medicinal purposes over generations by the Pikuni-Blackfeet people, and they shed light on mechanisms by which the plant extracts could slow neurodegeneration in PD.

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder affecting 5% of the population over the age of 85 (Shulman et al., 2011). Although PD is an age-related disorder, some familial forms of the disease occur with early onset. Environmental insults such as exposure to the pesticide rotenone, the herbicide paraquat (PQ), or drugs such as methamphetamine have been epidemiologically linked to increased PD risk (Callaghan et al., 2012; Tanner et al., 2011). Characteristic symptoms of PD include motor symptoms such as tremor, rigidity of the limbs, and postural instability (Massano and Bhatia, 2012), and non-motor symptoms such as olfactory deficits (Doty, 2012). Underlying pathological features include the death of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta, aggregation of the pre-synaptic protein alpha-synuclein (aSyn), and high levels of oxidative stress in the brain (Sanders and Greenamyre, 2013; Shulman et al., 2011; Spillantini et al., 1997). Impairment of mitochondrial complex I, resulting in a leakage of electrons from the electron transport chain, and changes in the metabolism/oxidation of dopamine in dopaminergic neurons are thought to trigger a buildup of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to oxidative damage and aSyn aggregation and neurotoxicity (Betarbet et al., 2000; Conway et al., 2001; Graham, 1978; Sanders and Greenamyre, 2013). Available treatments only reduce the symptoms without slowing the progressive neurodegeneration (Jankovic and Poewe, 2012).

The Blackfeet or Blackfoot Confederacy of the Northwestern Great Plains, located in Montana, USA (Blackfeet) and Alberta, Canada (Blackfoot), originally included five distinct tribes. Three of these – the Blackfoot or Siksikau, Blood or Kainah, and Piegan or Pikuni tribes, spoke the same Algonquian language, as did two additional allied tribes, the Sarcee (Athabascan) and GrosVentre or Atsina (Algonquian) tribes, who broke away from this confederacy during the 1860s. Today the Pikuni are divided into two nations separated by the USA-Canada border – Amskapi Pikuni residing on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in Montana, and the Aupotosi Pikaani on their own reserve in Brocket, Alberta. All modern “Blackfoot” tribes remain closely affiliated despite the international border (Vest 1988). Throughout their history, Native American tribes including the Pikuni-Blackfeet tribe have considered plants to play a key role in defining their identity. As medicines, physical symbols of spiritual powers, or ornaments/adornments, plants hold a central importance in the culture and identity of the Pikuni-Blackfeet people (Johnston, 1987).

Although modern medicine is available in local hospitals, the Pikuni-Blackfeet people have preserved their traditional practices. This article is aimed at documenting and analyzing contemporary herbal medicinal practices by the members of the Pikuni-Blackfeet tribe from Western Montana, with an emphasis on practices used to treat symptoms related to PD and other CNS disorders. We describe medicinal plants identified as being readily available to traditional communities, and we discuss the evolution of Pikuni-Blackfeet traditional medicine in response to contemporary influences. We also report on the characterization of a subset of the identified plants in terms of their ability to induce activation of the nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-mediated antioxidant pathway, which could play a critical role in the cellular antioxidant response and in cellular clearance mechanisms relevant to neuroprotection in PD. Moreover, we examine the capacity of a subset of extracts to protect against neuronal death and neurite loss induced by PD stresses. Our findings highlight the potential therapeutic utility of plants used for medicinal purposes over generations by the Blackfeet people, and they shed light on mechanisms by which the plant extracts could alleviate neurotoxicity in PD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Unless otherwise stated, chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Dulbecco’s Minimal Essential Media (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin streptomycin, and trypsin-EDTA were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Nuserum was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). The SH-SY5Y cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). The vector pSX2_d44_luc (Alam et al., 1999) was provided by Dr. Ning Li (UCLA) with the permission of Dr. Jawed Alam (LSU Health Sciences Center). Plant specimens were collected and deposited as described below.

2.2. Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: chicken anti-MAP2 (catalog number CPCA-MAP2, EnCor Biotechnology, Gainesville, FL); rabbit anti-TH (catalog number AB152, Millipore, Billerica, MA or catalog number 2025-THRAB, PhosphoSolutions, Aurora, CO, with similar results for both); and anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 488 and anti-chicken IgG-Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

2.3. Study area

This study was carried out in the city of Browning, Montana and in areas in close proximity. Browning is located within the Blackfeet Indian reservation, less than 30 miles from Glacier National Park and 45 miles from the border with Canada. The Blackfeet reservation is located in an ecological transition zone where the Western Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains meet to form the Rocky Mountain Front, providing a unique ecological pattern and a sanctuary for unique wildlife (Kudray, 2006). Pikuni-Blackfeet traditional medicine is intimately connected to this wildlife zone and natural areas such as the Badger-Two Medicine wildlands that bear religious significance (Vest, 1988; Zedeño, 2007).

2.4. Ethnopharmacological interviews

Ethnopharmacological interviews were carried out with the approval of the Purdue Institutional Review Board (IRB). The participants were informed about the anonymity of the survey and the fact that they could terminate the interview process at any time. The interview objectives and process were defined as described previously (de Rus Jacquet et al., 2014). Briefly, open-ended interviews were performed to question the participants about medicinal plants used to treat symptoms related to PD. Our approach was to ask the participants about medicinal plants used to treat both motor symptoms (tremor, weakness, and paralysis) and non-motor symptoms (inflammation, aches, anxiety, depression, and mental disorders). Our rationale for this approach was that medicinal plants used to treat these symptoms could potentially have protective effects in preclinical models relevant to PD pathogenesis. The choice of inflammation as a non-motor symptom for this study is based on evidence that (i) peripheral inflammation can play a role in perturbations of the innate immune response in the brain, including microglial activation; and (ii) peripheral anti-inflammatory compounds can alleviate these perturbations (Couch et al., 2011; Sanchez-Guajardo et al., 2013). Mental health conditions including anxiety and depression were of particular interest as medicines for treating these disorders likely cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) to target various regions of the brain including the midbrain (Chaudhury et al., 2013). Information about herbal remedies used to treat cancers was also considered relevant based on evidence that pathogenic mechanisms such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and the dysregulation of certain key proteins are common to both PD and some cancers (de Rus Jacquet et al., 2014; Devine et al., 2011; West et al., 2005).

2.5. Identification of plant species

When available, voucher specimens were collected, assigned a collection number, and deposited at the Purdue Kriebel Herbarium for future reference. When plant specimens were not available, we searched for previously documented scientific names corresponding to the common name. When the potential scientific name(s) was found, we listed the species from this particular genus that are reported to grow in Montana according to the USDA Plants Database. We then showed the participants photographs found in the USDA database or provided in academic websites, and the participants were asked if they recognized the plants that they collect from the photographs. All plant names were verified using the weblink: www.theplantlist.org (date accessed: 01–25–2016).

2.6. Preparation of botanical extracts

Plant material was harvested or obtained in dried form from Friends of the Trees Society (Hot Springs, MT). Freshly harvested plant material was dried at 37 °C with a food processor. To remain faithful to traditional practices, we avoided the use of potentially destructive techniques at each step of the extraction process. The use of water decoctions remains faithful to most traditional practices and avoids exposure of the plant materials to strong organic solvents or high pressures, both of which can change the chemical composition of the extract and lead to a loss of activity (Silva, 1998). For each sample, 10 g of plant material was extracted in 50 to 100 mL of deionized water by incubating for 45 min at 50 to 60 °C with constant stirring. Fresh samples of Datura stramonium leaves and roots, Allium sativum cloves, and Amelanchier arborea berries were processed in the same manner but without heating. To remove plant debris, samples were centrifuged at 19,800 × g for 30 to 60 min. The supernatant was then filtered through a 0.2 micron membrane, freeze-dried, and stored at −80 °C. The samples were protected from light during all steps of the extraction procedure. Prior to each experiment, freeze-dried extracts were dissolved in sterile deionized water.

2.7. Folin-Ciocalteu assay

The total polyphenolic content of the extracts was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu assay (Strathearn et al., 2014; Waterhouse, 2002). A mixture of 2 µL of botanical extract or gallic acid standard, 10 µL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, and 158 µL of H2O was prepared in a 96-well format and incubated for 5 min at 22 °C. Subsequently, 30 µL of Na2CO3 (200 g/L) was added with careful mixing, and the solution was incubated for 1 h at 22 °C. Absorbance was read at 765 nm with a Synergy 4 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc.). The total polyphenol content (in %) was estimated as the gallic acid equivalent.

2.8. Preparation of ARE-EGFP reporter adenovirus

A cDNA encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was subcloned as a KpnI-XhoI fragment into pENTR1A, yielding the construct pENTR-EGFP (Ysselstein et al., 2015). A DNA fragment encoding the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase polyadenylation signal (TKpolyA) was amplified from pAd/CMV/V5 by PCR and subcloned as an XhoI-EcoRV fragment into pENTR-EGFP, yielding the construct pENTR-EGFP-TKpolyA. A DNA fragment encompassing the 5’ SX2 enhancer and the minimal promoter of the mouse heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) gene was amplified from the vector pSX2_d44_luc (Alam et al., 1999) by PCR and subcloned as a BamHI-KpnI fragment into the vector pENTR-EGFP-TKpolyA, yielding pENTR-ARE-EGFP-TKpolyA (‘ARE’ refers to the two antioxidant response elements in the SX2 enhancer). The ARE-EGFP-TKpolyA insert from this construct was transferred into the pAd/PL-DEST ‘promotorless’ adenoviral vector via recombination using Gateway LR Clonase. The sequence of the DNA insert in the resulting adenoviral construct (pAd-ARE-EGFP-TKpolyA) was verified using an Applied Biosystems (ABI3700) DNA sequencer (Purdue Genomics Core Facility). The adenoviral construct was packaged into virus via lipid-mediated transient transfection of the HEK293A packaging cell line.

2.9. Preparation and treatment of cortical astrocytes

Cultures enriched with cortical astrocytes were prepared via dissection of E17 embryos obtained from pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) using methods approved by the Purdue Animal Care and Use Committee. The cortical regions were isolated stereoscopically, and the cells were dissociated with trypsin (final concentration, 13 µg/mL in 0.9% (w/v) NaCl). The cells were plated in a 175 cm2 flask pre-treated with rat collagen (25 µg/mL) at a density of ~14.5 × 106 cells per dish in media consisting of DMEM, 10% (v/v) FBS, 10% (v/v) horse serum (HS), penicillin (10 U/mL), and streptomycin (10 µg/mL). After 48 h, new media consisting of DMEM, 10% (v/v) FBS, 10% (v/v) HS, penicillin (20 U/mL), and streptomycin (20 µg/mL) was added to selectively propagate the astrocyte population (which at this stage consisted of clusters of cells attached to the dish) and remove unattached neurons. The media was replaced with fresh media every 2 days until most of the astrocytes had spread out on the plate, generally by 7 days in vitro (DIV). The astrocyte-rich culture was passaged at least once (and no more than twice) before being used for the described experiments.

Primary cortical astrocytes were plated on a 96-well, black clear-bottom plate (pretreated with rat collagen, 25 µg/mL) at a density of 5,000 cells/well. After 24 h, the cells were transduced with Nrf2 reporter adenovirus derived from the construct pAd-ARE-EGFP-TKpolyA at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 25. After 48 h, the virus-containing media was removed, and the cells were incubated in fresh media supplemented with botanical extract for 24 h. Control cells were transduced with the ARE-EGFP virus for 48 h and then incubated in fresh media for another 24 h, in the absence of extract (negative control) or in the presence of curcumin (5 µM) (positive control). The cells were then treated with Hoechst nuclear stain (2 µg/mL in HBSS) for 15 min at 37 °C, washed in HBSS, and imaged in HBSS at 37 °C using a Cytation 3 Cell Imaging Reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT) equipped with a 4X objective. Quantification of EGFP and Hoechst fluorescence was carried out with Gen 5 2.05 data analysis software (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT). For quantification of EGFP fluorescence, ROIs were generated by the software based on a cellular size range of 40 to 400 µm and a designated fluorescence intensity threshold. For each experiment, the threshold was adjusted so that the overall fluorescence intensity in the curcumin-treated culture was 1.5- to 2.5-fold greater than in the negative-control culture. For quantification of Hoechst fluorescence, ROIs were generated by the software based on a cellular size range of 10 – 40 µm. The fluorescence intensity threshold was set so that most of the nuclei stained with Hoechst were included among the detected ROIs. Finally, the number of ROIs for EGFP was divided by the total cell number (ROIs obtained from Hoechst fluorescence) for each condition and normalized to the control value to obtain a fold-change value.

2.10. Treatment of SH-SY5Y cells

To determine the optimal (sub-toxic) concentration of each extract over an extended treatment time, human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were cultured in RPMI media supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 µg/mL) in the absence or presence of extract for 7 days. The cells were then washed with PBS and incubated in a solution consisting of RPMI media and MTT (final concentration 0.25 mg/mL) for 2 h at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator. Subsequently, a lysis buffer consisting of 0.025N HCl, 2.0% (v/v) CH3COOH, 37.5% (v/v) N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), and 20% (w/v) SDS was added to each well, and the samples were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Absorbance was measured at 560 nM using a GENios microplate reader (Tecan, Durham, USA). Each absorbance value was normalized to the control value to obtain a % control value. A concentration below the lowest toxic concentration was selected for subsequent analyses of neuroprotective activity.

To determine the neuroprotective activity of the botanical extracts in cells exposed over an extended period to the environmental toxin rotenone, SH-SY5Y cells were treated with rotenone (20 nM) in the absence or presence of each extract. After 7 days, the total number of live (trypan-blue excluding) cells was determined using a Countess automated cell counter (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

2.11. Preparation and treatment of primary mesencephalic cultures

Primary midbrain cultures were prepared via dissection of E17 embryos obtained from pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) using methods approved by the Purdue Animal Care and Use Committee (Strathearn et al., 2014; Ysselstein et al., 2015). Briefly, the mesencephalic region containing the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area was isolated stereoscopically, and the cells were dissociated with trypsin (final concentration, 26 µg/mL in 0.9% (w/v) NaCl). The cells were plated in the wells of a 48 well plate (pretreated with poly-L-lysine, 5 µg/mL) at a density of 163,500 cells per well in media consisting of DMEM, 10% (v/v) FBS, 10% (v/v) HS, penicillin (10 U/mL), and streptomycin (10 µg/mL). After 5 DIV, the cultures were treated with AraC (20 µM, 48 h) to slow the proliferation of glial cells. At 7 DIV, ~10–20% of the total cell population consisted of neurons with extended processes.

Primary midbrain cultures (7 DIV) were incubated in the absence or presence of botanical extract for 72 h. Next, the cultures were incubated in fresh media containing rotenone (25 nM) or PQ (2.5 µM), in the absence or presence of extract for another 24 h. Control cultures were incubated in media without rotenone, PQ, or extract. The cultures were then fixed, permeabilized, and blocked (Strathearn et al., 2014; Ysselstein et al., 2015). After washing with PBS (136 mM NaCl, 0.268 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.76 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4), the cells were treated for 48 h at 4 °C with primary antibodies specific for microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) (chicken, 1:2000) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (rabbit, 1:500). The cells were then washed with PBS and treated with a goat anti-chicken antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (1:1000) and a goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000) for 1 h at 22 °C. After a final round of washing with PBS, prolong gold antifade reagent with DAPI was applied to each culture well before sealing with a coverslip.

Relative dopaminergic cell viability was assessed by counting MAP2- and TH-immunoreactive neurons in a blinded manner using a Nikon TE2000-U inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) equipped with a 20× objective, or using images acquired with a Cytation 3 Cell Imaging Reader equipped with a 4× objective. A minimum of 10 random fields of view were selected, and approximately 500–1000 MAP2+ neurons were counted per experiment for each treatment. Each experiment was conducted at least 3 times using embryonic cultures prepared from different pregnant rats. The data were expressed as the percentage of MAP2+ neurons that were also TH+ (thus ensuring that the data were normalized for variations in cell plating density).

Neurite length measurements were carried out on images taken with an automated Cytation 3 Cell Imaging Reader using a 4× objective (in general these images were the same as those used to determine dopaminergic cell viability as outlined above). Lengths of MAP2+ processes extending from TH+/MAP2+ neurons with an intact cell body (~60 neurons per sample) were assessed in a blinded manner using the manual length measurement tool of the NIS Elements software (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY).

2.12. Statistical analysis

Data obtained from measurements of SH-SY5Y cell survival and primary neuron viability were analyzed via ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (La Jolla, CA). In analyzing percentage cell viability data by ANOVA, square root transformations were carried out to conform to ANOVA assumptions. Neurite length data were analyzed using an approach that accounts for (i) the possibility of multiple neurites arising from a single cell, and (ii) comparison across experiments conducted on different days. Neurite lengths for multiple treatment groups were compared using a general linear model implemented in the GLM procedure of SAS Version 9.3 followed by the Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test (Cary, NC). For measurements of ARE-EGFP fluorescence, fold-change values were log-transformed, and the transformed data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 via a one-sample t-test to determine whether the mean of the log(fold-change) was different from the hypothetical value of 0 (corresponding to a ratio of 1) (Motulsky, 2014). For measurements of cell viability determined using the MTT assay, % control values were divided by 100, and the resulting fold-change values were log-transformed and analyzed via a one-sample t-test as described above for the ARE-EGFP fluorescence data.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pattern of the usage of medicinal plants

3.1.1. Herbal remedies to treat PD-related symptoms: Documentation of a contemporary traditional medicine

Healers and local members of the Pikuni-Blackfeet tribe were interviewed to document the medicinal uses of plants, with a focus on plants used to treat PD-related symptoms. There remains a thriving traditional community for which the use of plants is associated with the practice of herbal medicines, shamanic healing, and cultural identity (Johnston, 1987). The knowledge of medicinal plants is considered by the Pikuni-Blackfeet people to be of a sacred nature and to be passed ceremonially to selected healers (Johnston, 1987; Vest, 1988). The harvesting of plants and the preparation of medicines by healers involves a number of rituals including self-purification, songs, prayers, and the use of medicinal bundles, practices that are common to most Native American tribes (Buhner, 2006; Calloway, 1997). In this study, the uses of 18 medicinal plants to treat various ailments and diseases are reported in Supplementary Table 1. Leaves and fruits/berries are the most commonly used plant parts, accounting for 35% and 33% of the documented uses respectively, followed by roots (23%). Flowers and bark are used in 8% and 3% of the reported cases, respectively. Interestingly, only plants from the Lamiaceae family are used with a high level of preference for one plant part over others – i.e. leaves are the plant part chosen for 87.5% of the uses reported for this family, likely because of their aromatic properties.

We report the use of 10 medicinal plants encompassing 8 known botanical families to treat PD-related symptoms (Table 1). Previous Native American uses documented for these 10 plants are compiled in Supplementary Table 2. A review of the literature suggests that these plants could indeed have neuroprotective activities. A number of groups have reported that the berries of Sambucus nigra exhibit antioxidant and radical scavenger activities (Jakobek et al., 2007; Roy et al., 2002; Youdim et al., 2000). Elderberries are highly enriched in anthocyanins (Milbury et al., 2002; Veberic et al., 2009), and anthocyanin-rich extracts prepared from elderberries or other botanicals, in addition to individual anthocyanins, exhibit an array of antioxidant activities (Netzel et al., 2005; Strathearn et al., 2014; Zafra-Stone et al., 2007). The flower portion of the elderberry plant (referred to here as ‘elderflower’) also contains high levels of polyphenolic constituents, including quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, the most abundant component in the methanolic extract (Celik et al., 2014; Rieger et al., 2008). Analyses of elderflower extracts in cell culture models revealed neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities (Barros et al., 2011; Harokopakis et al., 2006) (see accompanying article, de Rus Jacquet et al., submitted).

Table 1.

Medicinal plants used by the Pikuni-Blackfeet people to treat PD-related symptoms

| Scientific name local name (Family), status1 |

Medicinal use | Part used | Mode of administration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arnica mollis Hook, Arnica (Asteraceae), N | Inflammation, anxiolytic, anti-depressant | Oil | Make a joint and muscle rub |

| Betula occidentalis Hook, Black birch (Betulaceae), N | Analgesic, anxiolytic, sleep regulation, calming | Bark | Make a tea of bark. Chew the bark for analgesic properties. |

| Filipendula ulmaria (L.) Maxim., Meadow sweet (Rosaceae), A/U | Relaxant, treatment for headaches | Leaves, flower tops | Make a tea of leaves and flower tops. |

| Hypericum perforatum L., St John’s Wort (Hypericaceae), I | Relaxant | - | Mix with valerian, red willow bark, St.John’s Wort and make a tea |

| Mentha × piperita L., Peppermint (Lamiaceae), N | Cold, antipyretic, clear the mind, see and hear better, earache, stomach problems | Leaves | Make a tea of leaves, drink 1 cup a day. For earache: smash the fresh leaves, let them dry, and place in the ear. Combine with sage for a more potent effect |

| Sambucus nigra L., Elderberry (Adoxaceae), N | Good for everything | Leaves, flowers | - |

| Scutellaria galericulata L., Scullcap (Lamiaceae), N | Calming, center the person | Leaves, flowers | Make a tea of leaves and flowers |

| Valeriana occidentalis A. Heller, Valerian (Valerianaceae), N | Anxiolytic | Whole plant | Boil in water and drink |

| Relaxant | Root | Mix with valerian, red willow bark, St.John’s Wort and make a tea |

Status (in Montana): N, native; I, introduced; A/U, absent, unreported. Data obtained from the USDA plants database: http://plants.usda.gov

The main plant species reported by members of the Pikuni-Blackfeet tribe to treat inflammation was Arnica mollis. Anti-inflammatory effects of Arnica sp. have been validated extensively in cellular and animal models and in humans (Kawakami et al., 2011; Knuesel et al., 2002; Lyss et al., 1998; Lyss et al., 1997; Macedo et al., 2004). Potential analgesic, sedative, and anxiolytic activities of Arnica sp. have also been reported (Ahmad, 2013; Widrig et al., 2007). Arnica preparations examined in randomized double-blind human clinical trials exhibited a potent analgesic effect in patients suffering from osteoarthritis (Knuesel et al., 2002; Widrig et al., 2007). A sesquiterpene lactone isolated from Arnica flowers, helenalin, showed anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting NFκB (Lim et al., 2012; Lyss et al., 1997), a transcription factor involved in inflammatory responses, suggesting that this constituent could be involved in Arnica’s medicinal activity.

A number of plants were documented in our study as having anxiolytic and sedative properties, including Betula occidentalis, Filipendula ulmaria, Hypericum perforatum, Scutellaria galericulata, and Valeriana occidentalis. Hypericum perforatum, a widely studied medicinal plant also known as St John’s Wort, was shown to modulate levels of the monoamines dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin via inhibition of reuptake (Nathan, 2001; Singer et al., 1999). Hypericin, an active constituent of this plant, was found to inhibit the release of glutamate (Chang and Wang, 2010), and pharmacological agents that interfere with glutamate signaling have been shown to alleviate symptoms and slow disease progression in preclinical models of PD (Johnson et al., 2009). Clinical trials revealed a significant relief of depression symptoms in patients treated with an extract prepared from Hypericum perforatum versus placebo (Gaster and Holroyd, 2000; Schrader, 2000; Woelk, 2000). The plant extract of Scutellaria laterifolia and two of its flavonoid constituents, baicalein and wogonin, were reported to have anxiolytic properties (Awad et al., 2003; de Carvalho et al., 2011; Hui et al., 2002). An extract prepared from Scutellaria baicalensis exhibited neuroprotective activities in a model of global cerebral ischemia (Kim et al., 2001), and baicalein was shown to be neuroprotective in cellular models of PD (Li et al., 2012b) and to interfere with aSyn aggregation in cells and in solutions of the recombinant protein (Lu et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2004). Moreover, wogonin was found to reduce microglial activation and neuroinflammation in a model of brain injury (Lee et al., 2003a). Finally Valeriana officinalis, another widely studied medicinal plant, was reported to reduce sleep disorders in patients (Bent et al., 2006; Leathwood et al., 1982) and to elicit neuroprotection in cellular and animal models of PD and Alzheimer’s disease (Malva et al., 2004; Sudati et al., 2013).

Although Betula occidentalis was an additional plant reported by members of the Pikuni-Blackfeet tribe to be used as a calming or anxiolytic agent, previous studies have been largely focused on documenting this plant’s anti-nociceptive properties. Betula platyphylla var. japonica and Betula alnoides showed anti-inflammatory properties in cultured fibroblasts (Sur et al., 2002) and antinociceptive properties in rat models of inflammation (Huh et al., 2011). The plant consists largely of the pentacyclic triterpenes betulinic acid and betulin, and these were reported to have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory activities (Alakurtti et al., 2006; Cichewicz and Kouzi, 2004; Yi et al., 2010; Yun et al., 2003).

Another plant documented in this study as being used to treated PD-related symptoms, Mentha × piperita (peppermint), is a widely used medicinal plant with potent pharmacological activities. The oil extracted from peppermint contains mainly menthol, menthone, isomenthone, and eucalyptol, although the relative levels of these constituents vary among different extracts (e.g. as a result of differences in plant varieties or the eco-geographical areas in which the plants were grown) (McKay and Blumberg, 2006). Previously reported properties of peppermint plant extracts or essential oils that are potentially relevant to PD therapy include analgesic effects in mouse models of pain and the ability to scavenge free radicals (McKay and Blumberg, 2006; Riachi and De Maria, 2015).

In addition to documenting the medicinal uses of plants revealed by members of the Pikuni-Blackfeet tribe, we searched the Native American Ethnobotany database (http://herb.umd.umich.edu/) to identify additional plant species with potential neuroprotective activities (Supplementary Table 3). Because no results were found for the motor symptom ‘tremor’, related symptoms such as “memory strengthener” and “paralysis” were chosen as primary keywords. This search led to the identification of 10 plant species, a subset of which were selected to be further characterized in terms of their neuroprotective activities (see ‘Study Design’).

3.1.2. Anti-cancer activities

Some of the plants reported by Pikuni-Blackfeet Indians as being used to treat PD-related symptoms show chemopreventive activities in cancer models, consistent with findings from a previous study (de Rus Jacquet et al., 2014). Betulin, a constituent of Betula sp., has been found to induce cytotoxicity and apoptosis in cellular models of cancer (Dehelean et al., 2012; Jonnalagadda et al., 2013). Botanical extracts prepared from anthocyanin-rich plants such as elderberries and individual anthocyanins exhibit anti-cancer activities (Jing et al., 2008; Thole et al., 2006; Wang and Stoner, 2008) and have chemopreventive effects that correlate with their ability to enhance quinone reductase activity and inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 activity (Thole et al., 2006). An extract prepared from Scutellaria sp. and its phytochemical constituents wogonin and baicalein have demonstrated cytotoxic, chemopreventive activity in cellular and in vivo models (Huang et al., 2012; Ikemoto et al., 2000; Li-Weber, 2009; Taniguchi et al., 2008).

Salvia sp. (sage) and Mentha × piperita extract or essential oil and bioactive constituents of these preparations, including polyphenols (apigenin, hesperitin, eriodictyol, luteolin, rosmarinic acid) and terpenes (menthol, limonene), also have cytotoxic and chemopreventive activities (Areias et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2007; Crowell and Gould, 1994; Kaefer and Milner, 2008; Kamatou et al., 2013; McKay and Blumberg, 2006; Shukla and Gupta, 2010; Tanaka et al., 1997; Xavier et al., 2009). The monoterpene d-limonene has been shown to interfere with tumor initiation and progression and to induce tumor regression in multiple rodent models of carcinogenesis (Crowell, 1999). The bioactive polyphenol apigenin is a promising anti-proliferative compound, as demonstrated in breast carcinoma cells (Yin et al., 2001) and a rodent model of metastasis (Caltagirone et al., 2000). In a pancreatic cancer combination therapy model, apigenin potentiated the anti-tumor effect of the chemotherapeutic agent gemcitabine both in cell culture and in vivo (Lee et al., 2008). The dietary polyphenol luteolin has also been shown to elicit chemopreventive activity in a variety of experimental settings and via multiple mechanisms of action (Lin et al., 2008), including disruption of signaling related to cell proliferation (Lee et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 1998), induction of apoptosis (Lee et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2002), and inhibition of angiogenesis (Bagli et al., 2004; Hasebe et al., 2003). Finally, data from a number of reports suggest that rosmarinic acid has anti-proliferative, anti-angiogenic, and anti-mutagenic activity (Furtado et al., 2008; Huang and Zheng, 2006; Makino et al., 2000), although one study failed to reveal anti-proliferative effects of rosmarinic acid on seven different human cancer types (Yesil-Celiktas et al., 2010).

3.1.3. Evolution of medicinal uses and external influences

It is interesting to note that some of the plants documented in this study are not native to North America and/or the State of Montana. One example of a non-native plant is Arctium lappa, commonly referred to as burdock (Stephens, 2012). Burdock is documented as an herbal medicine for skin diseases both in this study and in previous ethnopharmacological records focused on Native Americans (Chandler et al., 1979; Densmore, 1932; Mechling, 1959). Interestingly, burdock is mentioned in the French Codex as a remedy for skin diseases (French Pharmacopoeia Commission, 1837). Therefore, it seems reasonable to suggest that the dermatological use of burdock could be derived from European traditional uses. Additionally, Valeriana occidentalis, an herbaceous perennial plant, is documented here as an anti-anxiety and relaxing herbal medicine, but there is no record of its use in the many studies referenced in the Native American Ethnobotany online database (Supplementary table 2). However, the related species Valeriana officinalis was already described in the 1700s and 1800s as a medicine against hysteria (in the form of an aqua antihysterica) in the French Codex, English dispensatory, and German pharmacopoeia (Colborne, 1753; French Pharmacopoeia Commission, 1837; Lochman, 1873). The use of Valeriana occidentalis in Native American traditional medicine is not recorded in the Native American Ethnobotany database that groups papers generally published in the 1920s to 1990s, although it mentions the use of Valeriana uliginosa as a sedative (“feeble sedative to the nervous system”) (Smith, 1923). Collectively, these observations pertaining to burdock and Valeriana occidentalis suggest a contemporary adaptation of traditional herbal practices and support the idea of an evolving traditional medicine, benefiting from the latest advances in scientific validation of botanical safety and efficacy as well as broad communication of these advances in various media such as herbal books (Falquet, 2007; Popper-Giveon, 2009; Willcox et al., 2011).

3.2. Neuroprotective activities of medicinal plants traditionally used to treat PD-related symptoms

3.2.1. Study design

A total of 9 medicinal plants were selected for characterization as neuroprotective candidates based on their traditional uses and availability at the time of the study. Filipendula ulmaria and Mentha × piperita were documented in this study as herbal remedies to treat PD-related symptoms as defined in the Materials and Methods (Table 1). Salvia officinalis and Trifolium pratense were reported by the Pikuni-Blackfeet Indians to be anti-cancer remedies (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, Salvia sp. was traditionally used to treat paralysis and as a sedative and analgesic medicine (Bocek, 1984; Train, 1941; Zigmond, 1981). A species related to Trifolium pratense, Trifolium repens, was previously reported to treat paralysis (Herrick, 1977) (Supplementary Table 3). Achillea millefolium was selected because it is used as an analgesic (Supplementary Table 1) (Black, 1980; Hellson, 1974; Raymond, 1945). Acorus calamus was selected because it alleviates paralysis (Leighton, 1985), has analgesic, anticonvulsive, and stimulant properties (Hamel, 1975; Hart, 1981; Johnston, 1987; Smith, 1973), and is used as a psychological aid (Supplementary Table 3) (Gilmore, 1919). We chose to study the ubiquitous plant Allium sativum as a potential neuroprotective candidate based on evidence that Allium sp. has been used as a stimulant (Hamel, 1975) (Supplementary Table 3). We note that similar pro-health effects have been reported for different Allium species, likely because these species have a similar chemical content characterized by high levels of organosulfur compounds (Bianchini and Vainio, 2001; Rahman, 2003; Rose et al., 2005). Amelanchier alnifolia has febrifuge and tonic properties and is used as an adjuvant for medicinal preparations (Leighton, 1985; Turner, 1980) (Supplementary Table 3). We chose to study Amelanchier arborea because of its availability at the time of harvest. Finally, Datura stramonium was selected on the basis of evidence that Datura sp. has a range of traditional uses consistent with the mitigation of PD-like symptoms (e.g. it is used as an analgesic, stimulant, sedative, anti-inflammatory agent, or psychological aid; see Supplementary Table 3) (Colton, 1974; de Rus Jacquet et al., 2014; Speck, 1942; Swank, 1932; Whiting, 1939).

The 9 medicinal plants selected as outlined above were prepared as 10 extracts (the roots and leaves of Datura stramonium were extracted) and screened for their ability to induce activation of the Nrf2-mediated cellular antioxidant response in primary cortical astrocytes. The transcription factor Nrf2 regulates the expression of genes encoding cytoprotective and antioxidant proteins including glutamate cysteine ligase (GCL), heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), and NAD(P)H dehydrogenase quinone 1 (NQO-1) through interactions with the antioxidant response element (ARE) (Kumar et al., 2014). In the cytosol, Nrf2 is subject to rapid degradation by the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)-Cul3 ubiquitin E3 ligase complex, but modification of Keap1 by reactive molecules, including ROS and plant polyphenols, results in a disruption of Keap1-dependent Nrf2 degradation, increased Nrf2 accumulation and nuclear entry, and the expression of Nrf2-regulated antioxidant response genes (Bryan et al., 2013; Erlank et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2014; Satoh et al., 2013; Surh et al., 2008). In the brain Nrf2 is mostly active in astrocytes, where it plays a key role in astrocyte-mediated neuroprotection in part by producing glutathione metabolites that are taken up and reassembled by neighboring neurons (Shih et al., 2003). Evidence suggests that the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant pathway could be an important drug target for neurodegenerative diseases such as PD (de Vries et al., 2008; Kumar et al., 2012; Satoh et al., 2013).

Based on the rationale that plant extracts that stimulate the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant pathway should have a high propensity to alleviate cell death triggered by oxidative insults, two extracts that were found to induce a robust activation of Nrf2 signaling were further assayed for (i) protective activity in SH-SY5Y dopaminergic neuronal cells chronically exposed to rotenone, an inhibitor of mitochondrial complex I that triggers oxidative stress (Betarbet et al., 2000; Sherer et al., 2003); and (ii) the ability to attenuate dopaminergic cell death in primary midbrain cultures exposed to PQ, a cellular model that reproduces many features of the affected brain region in PD patients (Strathearn et al., 2014; Ysselstein et al., 2015).

3.2.2. A screen for plant extracts that activate the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response

In an initial screen of cellular antioxidant activity, the panel of 10 plant extracts described above was tested for the ability to activate Nrf2 signaling using a fluorescence-based reporter assay. Primary cortical astrocytes were transduced with a reporter adenovirus encoding EGFP downstream of the SX2 enhancer (encompassing two AREs) and the HO-1 minimal promoter. Astrocytes treated with a water extract of Achillea millefolium leaves, Allium sativum cloves, Datura stramonium leaves, Datura stramonium root, Filipendula ulmaria leaves and flowers, Salvia officinalis leaves, or Trifolium pratense flowers exhibited increased EGFP fluorescence compared to untreated cells, suggesting that these extracts induced increased binding of Nrf2 to the ARE and activation of Nrf2-mediated transcription (Fig. 1). In contrast, astrocytes treated with an extract prepared from Amelanchier arborea berries, Acorus calamus rhizome, or Mentha × piperita leaves did not exhibit a significant increase in EGFP fluorescence (Fig. 2). The absence of activity in these extracts may be the result of a failure during the preparation of the extract to recover compounds that would normally activate the Nrf2 pathway. However, it is also possible that extracts that appear to be inactive in the Nrf2 reporter assay in primary cortical astrocytes could in fact activate the Nrf2 antioxidant response in other cellular models that better recapitulate the complexity of the brain environment, including primary midbrain cultures prepared by co-culturing neurons, astrocytes, and microglia.

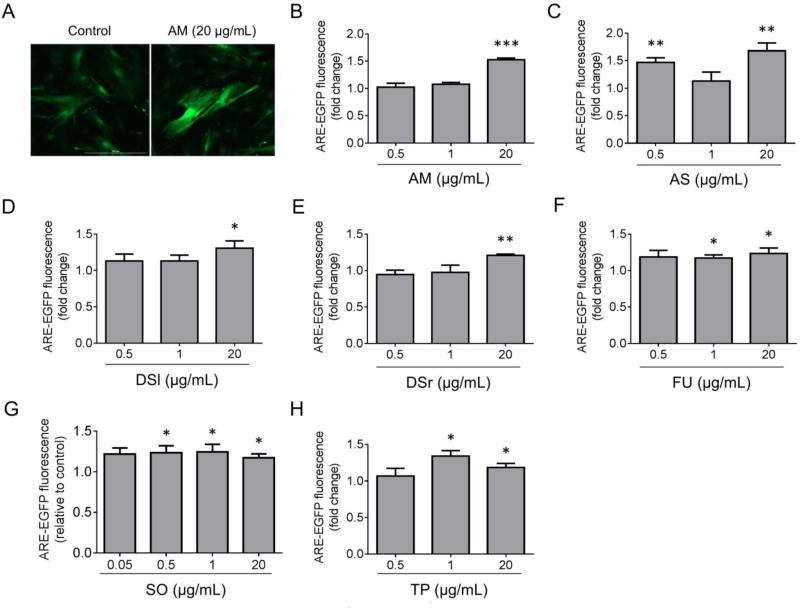

Figure 1. A subset of botanical extracts activate Nrf2-mediated transcription.

Primary cortical astrocytes were transduced with an ARE-EGFP reporter adenovirus and incubated in the presence of botanical extract. Control cells were transduced with the reporter virus and incubated in the absence of extract. Images (A) and graphs (B–H) show an increase in EGFP fluorescence (fold change relative to control) in astrocytes treated with extract prepared from Achillea millefolium (AM) (A, B)), Allium sativum (AS) (C), Datura stramonium leaves (DSl) (D), Datura stramonium root (DSr) (E), Filipendula ulmaria (FU) (F), Salvia officinalis (SO) (G), or Trifolium pratense (TP) (H). Scale bar in A, 300 µm. The data in (B–D) are presented as the mean ± SEM; n = 4; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus a predicted ratio of 1; log transformation followed by one-sample t-test.

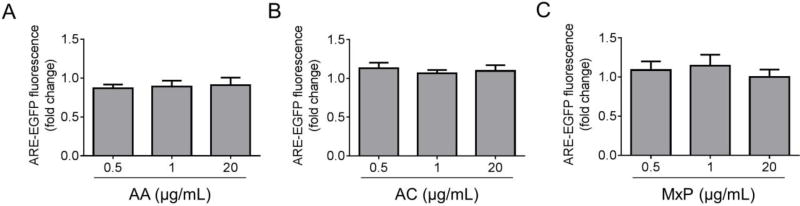

Figure 2. A subset of botanical extracts failed to activate the Nrf2/ARE response.

Primary cortical astrocytes were transduced with an ARE-EGFP reporter adenovirus and incubated in the presence of botanical extract. Control cells were transduced with the reporter virus and incubated in the absence of extract. Graphs show no increase in EGFP fluorescence (fold change relative to control) in astrocytes treated with extract prepared from Amelanchier arborea (AA) (A), Acorus calamus (AC) (B), or Mentha × piperita (MxP) (C). The data are presented as the mean ± SEM; n = 3–5.

To our knowledge, this is the first report that crude extracts prepared from Achillea millefolium, Datura stramonium, Filipendula ulmaria, and Trifolium pratense activate Nrf2-mediated signaling. The stimulatory effects of Allium sativum extracts on Nrf2 signaling were described previously in a cellular model of cadmium-induced toxicity, in an animal model of chromium toxicity, and in human endothelial cells (Hiramatsu et al., 2015; Kalayarasan et al., 2008; Lawal and Ellis, 2011). In addition, phenolic diterpenes isolated from Salvia officinalis were previously shown to induce activation of Nrf2-dependent transcription in mouse primary cortical cultures (Fischedick et al., 2013). However, the data presented herein are the first documented results showing stimulatory effects of extracts prepared from Allium sativum and Salvia officinalis on Nrf2 signaling in cortical astrocytes. A number of other plant extracts have been shown to induce Nrf2-dependent transcription, including green tea (Newsome et al., 2014) and extracts prepared from turmeric (Balstad et al., 2011), broccoli (Balstad et al., 2011; McWalter et al., 2004), and rosemary (Yan et al., 2015) (see accompanying article, de Rus Jacquet et al., submitted). The activation of Nrf2 signaling by some of these botanicals has been attributed to their polyphenolic constituents, some of which could also be present in the Nrf2-activating extracts described here. Analysis of the total polyphenolic content of the extracts with a Folin-Ciocalteu assay revealed that the extract with the highest concentration of polyphenols (Filipendula ulmaria), had a relatively weak propensity to activate Nrf2 signaling in terms of maximum response or efficacy. Furthermore, extracts prepared from Mentha × piperita, Salvia officinalis, and Trifolium pratense have the same total polyphenolic content, but only the Salvia officinalis and Trifolium pratense extracts activated the Nrf2 response. Accordingly, we infer that the composition rather than total polyphenolic content is most important to modulate Nrf2 signaling. Quercetin and kaempferol, two highly ubiquitous flavonol aglycones (Manach et al., 2004), have been shown to efficiently activate the Nrf2/ARE pathway and induce the expression of Nrf2 downstream target genes (Kumar et al., 2014; Magesh et al., 2012; Surh et al., 2008). Red clover isoflavone-rich extracts and individual isoflavones were also found to activate Nrf2 signaling and prevent oxidative damage (Li et al., 2014; Occhiuto et al., 2009; Park et al., 2011). Allium sativum is characterized by high contents of organosulfur compounds that were previously found to activate Nrf2 in cellular and animal models (Chen et al., 2004; Kay et al., 2010; Tobon-Velasco et al., 2012). These polyphenolic and organosulfur constituents could activate Nrf2 signaling by directly reacting with Keap1 or by engaging in redox cycling reactions that lead to a build-up of ROS, which in turn can react with Keap1 (Erlank et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2014; Magesh et al., 2012; Satoh et al., 2013). Nrf2 activation by these extracts would be expected to lead to the enhancement of a range of activities likely important for neuroprotection in the brains of PD patients, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities (Alam et al., 1999). In contrast, extracts that were prepared from plants used by the Pikuni-Blackfeet Indians to treat PD-related symptoms but failed to induce up-regulation of Nrf2 signaling could potentially achieve neuroprotective effects in the brains of patients via other mechanisms.

3.2.3. Effects of botanical extracts on the viability of neuronal cells exposed to PD-related insults

Environmental poisons that trigger increased oxidative stress, including the pesticide rotenone and the herbicide PQ, have been linked epidemiologically to increased PD risk (Tanner et al., 2011). Rats treated chronically with low doses of rotenone have a phenotype that reproduces key features of human PD, including motor dysfunction, preferential nigral dopaminergic cell death, and aSyn aggregation, oxidative damage, and microglial activation in the midbrain (Betarbet et al., 2000; Cannon et al., 2009; Sherer et al., 2003). A number of these features (cytotoxicity, oxidative stress, aSyn aggregation) are also observed in cultures of immortalized neuronal cells exposed for prolonged periods to low levels of rotenone (Borland et al., 2008; Sherer et al., 2002). In this study, we characterized the Allium sativum, Trifolium pratense, and Amelanchier arborea extracts in terms of their effects on the viability of human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells treated chronically with a low dose of rotenone (20 nM, 7 d). Extracts prepared from Allium sativum and Trifolium pratense were selected based on their activation of Nrf2 with relatively high potency and efficacy (Fig. 1) and their chemical profiles (presence of organosulfur compounds and isoflavones, respectively). The extract prepared from Amelanchier arborea was selected based on our finding that this extract activated Nrf2 in primary midbrain cultures (data not shown) and on previous reports suggesting that this extract has high levels of anthocyanins (Bakowska-Barczak and Kolodziejczyk, 2008; Lavola et al., 2012). An advantage of choosing these three botanical species is that this approach enabled us to compare the neuroprotective activities of extracts with very different chemical profiles. In a preliminary experiment, we determined that extracts prepared from Allium sativum, Trifolium pratense, and Amelanchier arborea were non-toxic to SH-SY5Y cells at concentrations up to 100 µg/mL, 10 µg/mL, and 25 µg/mL, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1). In experiments designed to examine neuroprotective effects of the extracts at concentrations below these maximal non-toxic concentrations, we observed an increase in the viability of cells treated with rotenone plus extract compared to cells exposed to rotenone alone (Fig. 3). These results suggested that all three extracts interfered with the toxic effects of rotenone.

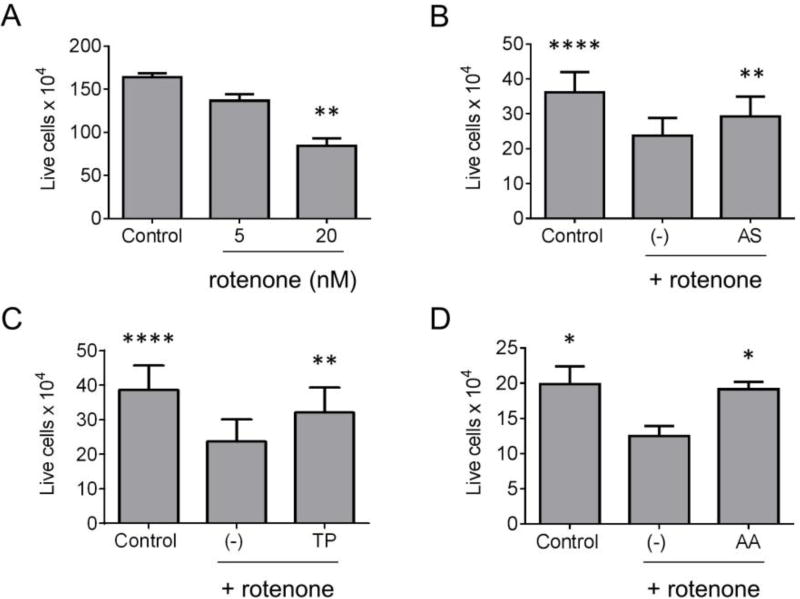

Figure 3. Botanical extracts protect neuroblastoma cells against toxicity elicited by rotenone.

(A) SH-SY5Y cells were incubated in the absence or presence of rotenone (5 or 20 nM) for 7 days to identify a toxic concentration of rotenone to use in assays of protection by botanical extracts. (B–D) SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to rotenone (20 nM) in the absence or presence of extract prepared from Allium sativum (AS) (50 µg/mL) (B), Trifolium pratense (TP) (1 µg/mL) (C), or Amelanchier arborea (AA) (5 µg/mL) (D) for 7 days. In panels B-D, control cells were incubated in the absence of rotenone or extract. The data are presented as the number of trypan blue-excluding cells (live cells) per well. Mean +/− SEM; n = 3 (A), n = 9 total replicates from 5 independent experiments (B), n = 5 total replicates from 3 independent experiments (C), n = 4 total replicates from 2 independent experiments (D); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 versus control (A) or versus rotenone alone (−) (B–D); one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test.

Next, the three extracts were further characterized in terms of their ability to alleviate dopaminergic cell death in a primary midbrain culture model of PD. An advantage of midbrain cultures is that they consist of post-mitotic neurons (including dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic neurons) and glial cells (including astrocytes and microglia), and thus they can be used to examine neurotoxic or neuroprotective mechanisms in a native-like environment similar to the midbrain region affected in PD (Strathearn et al., 2014; Ysselstein et al., 2015). Primary midbrain cultures were treated with the PD-related toxin PQ, a pro-oxidant, in the absence or presence of extract prepared from Allium sativum, Trifolium pratense, or Amelanchier arborea. The cultures were co-stained for MAP2, a general neuronal marker, and TH, a selective marker of dopaminergic neurons, and the relative viability of dopaminergic neurons was assessed by determining the ratio of TH+ to MAP2+ neurons. The relative number of TH+ neurons was greater in cultures treated with PQ plus extract prepared from Allium sativum or Amelanchier arborea (but not Trifolium pratense) compared to cultures exposed to PQ alone (Fig. 4). Additional examination of the same cultures revealed a decrease in the lengths of neurites extending from TH+/MAP2+ neurons in cultures treated with PQ alone, whereas this effect was alleviated in cultures exposed to PQ in the presence of extract prepared from Allium sativum or Amelanchier arborea (Fig. 5). Because neurite lengths were determined by examining the MAP2 stain, these results suggest that the increase in TH+ neurons induced by these two extracts as shown in Fig. 4 involves an increase in dopaminergic cell survival rather than an increase in TH expression. The lengths of neurites extending from TH−/MAP2+ neurons were only slightly reduced in cultures treated with PQ compared to control cultures, suggesting that PQ was preferentially toxic to dopaminergic neurons in our primary midbrain culture model (Supplementary Fig. 2).

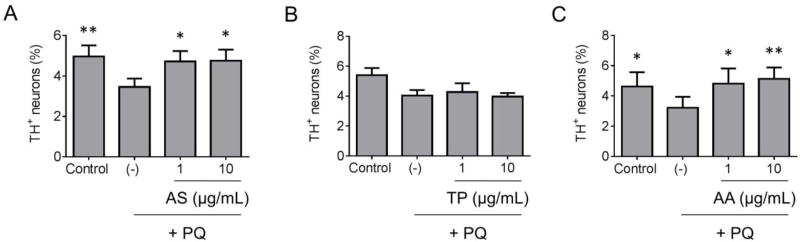

Figure 4. Botanical extracts alleviate PQ-mediated dopaminergic cell death.

Primary midbrain cultures pre-incubated in the absence or presence of extract prepared from Allium sativum (AS) (A), Trifolium pratense (TP) (B), or Amelanchier arborea (AA) (C) were exposed to PQ (2.5 µM) in the absence or presence of extract. Control cells were incubated in the absence of PQ or extract. The cells were stained with antibodies specific for MAP2 and TH and scored for relative dopaminergic cell viability. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM; n = 6 (A), n = 3 (B), n = 4 (C); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus PQ alone (−); square root transformation, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test.

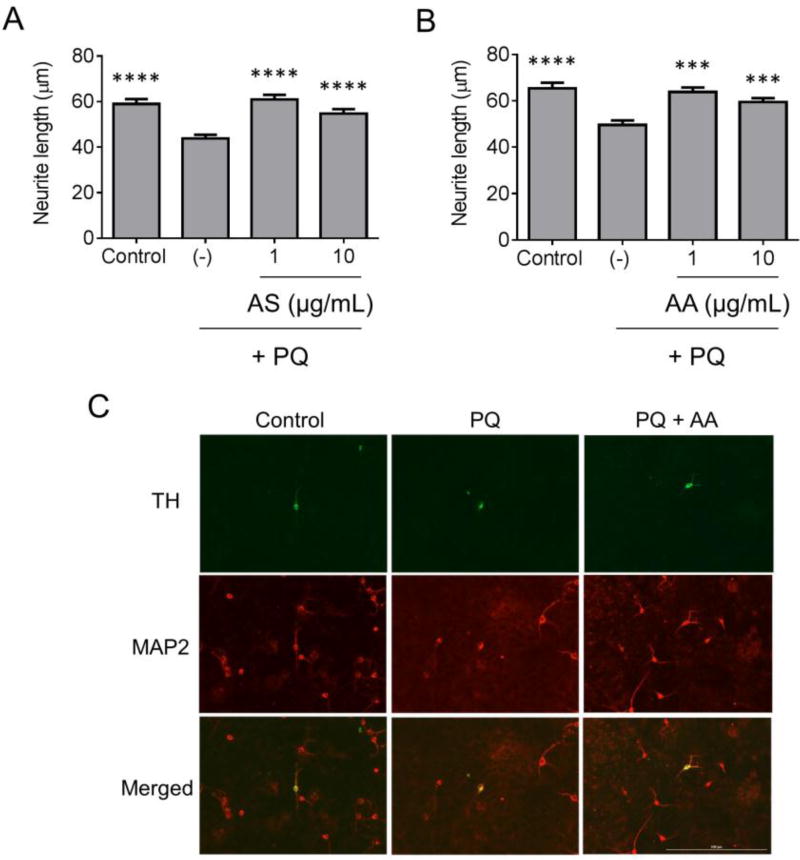

Figure 5. Botanical extracts rescue PQ-induced neurite loss.

Primary midbrain cultures pre-incubated in the absence or presence of botanical extract were exposed to PQ (2.5 µM) in the absence or presence of extract. Control cells were incubated in the absence of PQ or extract. The cells were stained with antibodies specific for MAP2 and TH, and MAP2+/TH+ neurons were scored for neurite lengths. Graphs (A, B) and images (C) show protective effects of extracts prepared from Allium sativum (AS) (A) or Amelanchier arborea (AA) (B, C) against PQ-induced neurite retraction. Scale bar in C, 200 µm. The data in (A) and (B) are presented as the mean +/− SEM; n = 3; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 versus PQ alone (−); Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test after general linear model implementation.

Collectively, these data reveal for the first time that extracts prepared from Allium sativum, Trifolium pratense, or Amelanchier arborea can interfere with neurotoxicity elicited by PD-related insults. All three extracts alleviated the toxic effects of rotenone in a dopaminergic neuronal cell line, whereas extracts prepared from Allium sativum or Amelanchier arborea (but not Trifolium pratense) attenuated PQ-mediated dopaminergic cell death in primary midbrain cultures. The fact that different profiles of extracts exhibited protective effects against toxicity elicited by rotenone versus PQ likely reflects the different mechanisms of action of the two toxicants. Rotenone elicits oxidative stress via inhibition of mitochondrial complex I, whereas PQ triggers a buildup of ROS by engaging in redox cycling reactions in the cytosol and has only weak inhibitory effects on complex I activity (Cristovao et al., 2009; Richardson et al., 2005; Sherer et al., 2003). Accordingly, the alleviation of rotenone neurotoxicity by the Trifolium pratense extract could reflect the extract’s ability to enhance mitochondrial function. Consistent with this idea, we have found that this extract interferes with rotenone-induced dopaminergic cell death in primary midbrain cultures and ameliorates rotenone-mediated deficits in mitochondrial O2 consumption (de Rus Jacquet et al., manuscript in preparation). In contrast, attenuation of neurotoxicity elicited by both rotenone and PQ by extracts prepared from Allium sativum or Amelanchier arborea could reflect the ability of these extracts to activate cellular pathways that mitigate the pro-oxidant effects of both toxicants, including potentially the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response. This reasoning is supported by evidence that Nrf2-dependant transcription attenuates neurodegeneration triggered by rotenone or PQ in cellular and animal models (Lee et al., 2003b; Li et al., 2012a) and by our finding that Nrf2 expression from a viral construct at levels similar to those observed in astrocytes treated with the Allium sativum extract (Fig. 1C) results in an increase in dopaminergic cell survival in primary midbrain cultures exposed to rotenone or PQ (Tambe et al., manuscript in preparation). In this regard, our observation that the Trifolium pratense extract activates Nrf2 signaling in astrocytes but fails to alleviate PQ neurotoxicity in primary midbrain cultures is unexpected. Interestingly, we have found that the Trifolium pratense extract fails to induce astrocytic Nrf2-mediated transcription in primary midbrain cultures (de Rus Jacquet et al., manuscript in preparation), and this failure to activate Nrf2 signaling could potentially account for the inability of the extract to alleviate PQ neurotoxicity in this setting.

A number of other plant extracts have been shown to alleviate neurotoxicity elicited by rotenone (Li et al., 2013; Song et al., 2012; Strathearn et al., 2014) or PQ (Li et al., 2013; Prakash et al., 2013; Yadav et al., 2013). The protective effects of some of these extracts have been attributed to certain polyphenolic constituents, some of which could also be present in the neuroprotective extracts described here. For example, Trifolium pratense contains high levels of isoflavones such as biochanin A and formononetin, and lower concentrations of daidzein and genistein (Krenn et al., 2002; Tsao et al., 2006). Isoflavones from Trifolium pratense have been shown to protect dopaminergic neurons against LPS-induced inflammation and neurotoxicity (Chen et al., 2008) and to alleviate H2O2-induced oxidative stress in HCN 1-A neuronal cultures (Occhiuto et al., 2009), and individual isoflavones have been found to elicit neuroprotection in cellular and in vivo PD models (Baluchnejadmojarad et al., 2009; Chinta et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2008). Although the Amelanchier extract examined in this study had a low polyphenol content based on data obtained using the Folin-Ciocalteu assay (Table 3), data from other studies indicate that Amelanchier sp. extracts are typically enriched in anthocyanins (Bakowska-Barczak and Kolodziejczyk, 2008; Lavola et al., 2012; Zadernowski et al., 2005). Anthocyanin-rich berry extracts have been shown to interfere with rotenone-induced dopaminergic cell loss, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction (Kim et al., 2010; Roghani et al., 2010; Strathearn et al., 2014). Similar to the Amelanchier extract, the Allium sativum extract examined in this study was found to contain low levels of polyphenols (Table 3). The neuroprotective effects of this extract could reflect the presence of organosulfur compounds derived from alliin (L-(+)-S-allylcysteine sulfoxide), such as allyl thiosulfinates, and sulfur compounds not derived from alliin, including ɣ-glutamyl-S-allylcysteine (Lawson and Gardner, 2005). In a previous study, S-allylcysteine and aged garlic extract were found to inhibit oxidative damage in animal and cellular models via radical scavenging and by up-regulating the antioxidant response (Colin-Gonzalez et al., 2012).

Table 3.

Total polyphenolic content determined with the Folin-Ciocalteu assay

| Plant species | Plant Part | % total polyphenols1 |

|---|---|---|

| Achillea millefolium | Leaves | 6.2 |

| Acorus calamus | Rhizome | 1.2 |

| Allium sativum | Cloves | bd2 |

| Amelanchier arborea | Fruits | 0.5 |

| Datura stramonium | Leaves | 1.6 |

| Datura stramonium | Roots | 0.5 |

| Filipendula ulmaria | Leaves and flowers | 15.8 |

| Mentha × piperita | Leaves | 11.2 |

| Salvia officinalis | Leaves | 9.7 |

| Trifolium pratense | Flowers | 5.2 |

% total polyphenols in extract (mass/mass), estimated with the Folin-Ciocalteu assay.

bd: below detection level

In summary, our findings indicate that extracts prepared from Allium sativum cloves, Trifolium pratense flowers, and Amelanchier arborea berries alleviate neurodegeneration elicited by environmental PD-related insults. A number of the extracts’ polyphenolic constituents, including isoflavones, anthocyanins, and organosulfur compounds, are bioavailable and have been shown to penetrate the BBB (Andres-Lacueva et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2000; Lawson and Gardner, 2005; Manach et al., 2004). Accordingly, we infer that these extracts could potentially be of clinical benefit in reducing PD risk or slowing neurodegeneration in the brains of patients. Importantly, the ability of extracts prepared from Allium sativum and Amelanchier arborea to alleviate dopaminergic cell death triggered by rotenone or PQ implies that these extracts could potentially interfere with neurodegeneration in individuals with elevated PD risk resulting from exposure to a range of environmental stresses.

4. Conclusion

In our modern economy, the Pikuni-Blackfeet people have managed to preserve traditional practices related to the use of medicinal plants. Such preservation efforts have resulted in an extensive knowledge of various medicinal herbs and plants that have been reported to cure many ailments. This research was aimed at (i) documenting traditional Pikuni-Blackfeet medicine and contemporary uses of medicinal plants for general diseases as well as PD-related symptoms, (ii) evaluating the influence of the surrounding environment on the practice of Pikuni-Blackfeet traditional medicine, and (iii) characterizing the neuroprotective activities of a selection of plants documented in this study.

The insights obtained from our interviews reflect the contemporary herbal medicine of the Pikuni-Blackfeet people, characterized by a combination of native and introduced plant species. Our findings indicate that the uses of various plant species are unchanged relative to ancestral traditions, and that healers adapt to a changing environment with the introduction of additional plant species (e.g. Arctium lappa, Valeriana occidentalis). Interestingly, this progressive incorporation of knowledge into traditional practices is taking place in a society that has retained its ancient medicinal model, where a complex interrelationship between healers and the natural world is considered essential for providing cures. Preservation of wildlands considered sacred by the Pikuni-Blackfeet people will enable healers in this tribe to continue to practice their traditional medicine within this framework. Plant species documented in this study may prove useful for treating a variety of diseases, and it is critical to balance the use of this information with the need to ensure natural conservation. Many Native Americans are reluctant to share their herbal knowledge in part because of overexploitation that has occurred following previous studies. The careful use of traditional plants will ensure that their medicinal potential will be realized in local and broader communities not only for today’s patients, but also for those of future generations.

Based on ethnopharmacological data from our interviews and other studies, a primary screen designed to monitor stimulation of the Nrf2/ARE antioxidant pathway resulted in the identification of seven extracts with potential neuroprotective activities. Two of these extracts (prepared from Allium sativum cloves and Trifolium pratense flowers) and a third extract of interest (prepared from Amelanchier arborea berries) alleviated toxicity elicited by PD-related insults and are thus attractive neuroprotective candidates for humans at risk of developing PD as a result of environmental exposures. The ethnopharmacological approach used in this study enabled us to identify suitable plant candidates for neuroprotection studies, and the data from these analyses in turn have enabled us to better interpret the clinical effects of the extracts documented during the interviews. This study lays the foundation for further characterization of mechanisms by which the three extracts outlined above interfere with neurodegeneration in cellular and animal models of PD. In particular, a goal for future studies will be to determine whether the neuroprotective effects of these extracts depend on the extracts’ ability to activate Nrf2 signaling and/or ameliorate mitochondrial dysfunction.

Supplementary Material

SHSY5Y cells were exposed to extract prepared from Allium sativum (AS) (A), Trifolium pratense (TP) (B), or Amelanchier arborea (AA) (C). Control cells were incubated in the absence of extract. Cell viability was assessed using an MTT assay. The data obtained for cells treated with extract (determined as % of the control value) are presented as the mean ± SEM; n = 5–6 total replicates from 2 independent experiments; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p < 0.0001 versus a predicted value of 100%; log transformation followed by one-sample t-test.

Primary midbrain cultures were incubated in the absence or presence of PQ (2.5 μM). The cultures were stained with antibodies specific for MAP2 and TH, and MAP2+/TH−neurons were scored for neurite lengths. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM; n = 3.

Table 2.

Pharmacological activities of plant species used to treat PD-related symptoms

| Scientific name local name (Family) |

PD-related uses reported in this study |

Scientifically validated activities1 |

|---|---|---|

| Arnica mollis Hook, Arnica (Asteraceae) | Anti-inflammatory, anxiolytic, anti-depression | Anti-inflammatory (Ekenas et al., 2008; Lyss et al., 1997), analgesic and anxiolytic (Ahmad, 2013), sedative (Widrig et al., 2007) |

| Betula occidentalis Hook, Black birch (Betulaceae) | Analgesic, anxiolytic, sleep regulation, calming | Betulinic acid, a constituent of Betula sp. (Zhao et al., 2007): anti-inflammatory (Alakurtti et al., 2006), anti-antioxidant (Cichewicz and Kouzi, 2004), immunomodulatory (Yi et al., 2010; Yun et al., 2003). |

| Betulin: anti-cancer (Dehelean et al., 2012; Jonnalagadda et al., 2013). | ||

| Filipendula ulmaria (L.) Maxim., Meadowsweet (Rosaceae) | Treatment for headache, relaxing | Immunomodulatory (Halkes et al., 1997) |

| Hypericum perforatum L., Saint John’s Wort (Hypericaceae) | Relaxant | Antidepressant (Barnes et al., 2001), modulation of neurotransmitter reuptake (Nathan, 2001) and levels (Calapai et al., 1999; Chang and Wang, 2010) |

| Mentha × piperita L., Peppermint (Lamiaceae) | Clear the mind, see and hear better | Wide range of activities including anti-cancer, analgesic, antioxidant (McKay and Blumberg, 2006) |

| Sambucus nigra L., Elderberry (Adoxaceae) | Good for everything | Berries: anticancer, inhibition of quinone reductase and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (Thole et al., 2006), antioxidant (Youdim et al., 2000) Flowers: anti-inflammatory (Harokopakis et al., 2006) |

| Scutellaria galericulata L., Scullcap (Lamiaceae) | Calming, center the person | Anxiolytic (Awad et al., 2003), neuroprotective (Kim et al., 2001; Shang et al., 2010), anti-cancer (Li-Weber, 2009; Zhang et al., 2010), radical scavenger (Senol et al., 2010) |

| Wogonin: anxiolytic (Hui et al., 2002) and reduces inflammation of microglia (Lee et al., 2003) | ||

| Baicalein: anxiolytic, sedative (de Carvalho et al., 2011), neuroprotective in PD models (Li et al., 2012) | ||

| Valeriana occidentalis A. Heller, Valerian (Valerianaceae) | Anxiety, relaxant | Anxiolytic, antidepressant (Hattesohl et al., 2008; Murphy et al., 2010), antioxidant (Sudati et al., 2009), neuroprotection against rotenone-induced toxicity (Sudati et al., 2013) and Aβ-induced toxicity (Malva et al., 2004). |

Species documented in this study and/or related species

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R21 AG039718 and 1R03 DA027111 (J.-C. R), a grant from the Showalter Trust (J.-C. R.), a fellowship from the Botany in Action program, Phipps Botanical Garden, Pittsburgh (A. d. R. J.), and a fellowship from the Purdue Research Foundation (A. d. R. J.). The research described herein was conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grants Number C06-14499 and C06-15480 from the National Center for Research Resources of the NIH. The authors would like to thank Pauline Matt (Red Root Herbs) for her kind and extensive contribution and feedback throughout the study, Sandy K. Schildt for her constant guidance and all other participants from the Pikuni-Blackfeet tribe for their trust and valuable insight into Blackfeet traditional medicine, members of the Rochet lab for valuable discussions, and Dr. Vartika Mishra for assistance with the preparation of primary mesencephalic cultures. We are grateful to Dr. Ning Li (UCLA) and Dr. Jawed Alam (LSU Health Sciences Center) for providing the vector pSX2_d44_luc and. We are grateful to Dr. Jeffery Hubbard (University of Florida) and Nick Harby for assistance with the collection and identification of plant specimens.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmad M, Saeed F, Mehjabeen Jahan N. Neuro-pharmacological and analgesic effects of Arnica montana extract. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013:5. [Google Scholar]

- Alakurtti S, Makela T, Koskimies S, Yli-Kauhaluoma J. Pharmacological properties of the ubiquitous natural product betulin. European journal of pharmaceutical sciences : official journal of the European Federation for Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2006;29:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam J, Stewart D, Touchard C, Boinapally S, Choi AM, Cook JL. Nrf2, a Cap’n’Collar transcription factor, regulates induction of the heme oxygenase-1 gene. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:26071–26078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres-Lacueva C, Shukitt-Hale B, Galli RL, Jauregui O, Lamuela-Raventos RM, Joseph JA. Anthocyanins in aged blueberry-fed rats are found centrally and may enhance memory. Nutr Neurosci. 2005;8:111–120. doi: 10.1080/10284150500078117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areias FM, Valentao P, Andrade PB, Ferreres F, Seabra RM. Phenolic fingerprint of peppermint leaves. Food Chem. 2001;73:307–311. [Google Scholar]

- Awad R, Arnason JT, Trudeau V, Bergeron C, Budzinski JW, Foster BC, Merali Z. Phytochemical and biological analysis of skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora L.): a medicinal plant with anxiolytic properties. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology. 2003;10:640–649. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagli E, Stefaniotou M, Morbidelli L, Ziche M, Psillas K, Murphy C, Fotsis T. Luteolin inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis; inhibition of endothelial cell survival and proliferation by targeting phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinase activity. Cancer research. 2004;64:7936–7946. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakowska-Barczak AM, Kolodziejczyk P. Evaluation of Saskatoon berry (Amelanchier alnifolia Nutt.) cultivars for their polyphenol content, antioxidant properties, and storage stability. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:9933–9940. doi: 10.1021/jf801887w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balstad TR, Carlsen H, Myhrstad MC, Kolberg M, Reiersen H, Gilen L, Ebihara K, Paur I, Blomhoff R. Coffee, broccoli and spices are strong inducers of electrophile response element-dependent transcription in vitro and in vivo - studies in electrophile response element transgenic mice. Molecular nutrition & food research. 2011;55:185–197. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluchnejadmojarad T, Roghani M, Nadoushan MR, Bagheri M. Neuroprotective effect of genistein in 6-hydroxydopamine hemi-parkinsonian rat model. Phytotherapy research : PTR. 2009;23:132–135. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros L, Cabrita L, Boas MV, Carvalho AM, Ferreira ICFR. Chemical, biochemical and electrochemical assays to evaluate phytochemicals and antioxidant activity of wild plants. Food Chem. 2011;127:1600–1608. [Google Scholar]

- Bent S, Padula A, Moore D, Patterson M, Mehling W. Valerian for sleep: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of medicine. 2006;119:1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betarbet R, Sherer TB, MacKenzie G, Garcia-Osuna M, Panov AV, Greenamyre JT. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson’s disease. Nature neuroscience. 2000;3:1301–1306. doi: 10.1038/81834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini F, Vainio H. Allium vegetables and organosulfur compounds: do they help prevent cancer? Environmental health perspectives. 2001;109:893–902. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MJ. Algonquin Ethnobotany: An Interpretation of Aboriginal Adaptation in South Western Quebec. National Museums of Canada; Ottawa: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bocek BR. Ethnobotany of Costanoan Indians, California, Based on Collections by Harrington, John, P. Econ Bot. 1984;38:240–255. [Google Scholar]

- Borland MK, Trimmer PA, Rubinstein JD, Keeney PM, Mohanakumar K, Liu L, Bennett JP., Jr Chronic, low-dose rotenone reproduces Lewy neurites found in early stages of Parkinson’s disease, reduces mitochondrial movement and slowly kills differentiated SH-SY5Y neural cells. Molecular neurodegeneration. 2008;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan HK, Olayanju A, Goldring CE, Park BK. The Nrf2 cell defence pathway: Keap1-dependent and -independent mechanisms of regulation. Biochemical pharmacology. 2013;85:705–717. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhner SH. Sacred plant medicine : the wisdom in Native American herbalism, New ed. Bear & Co; Rochester, Vt: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan RC, Cunningham JK, Sykes J, Kish SJ. Increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in individuals hospitalized with conditions related to the use of methamphetamine or other amphetamine-type drugs. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2012;120:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calloway CG. New worlds for all : Indians, Europeans, and the remaking of early America. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Caltagirone S, Rossi C, Poggi A, Ranelletti FO, Natali PG, Brunetti M, Aiello FB, Piantelli M. Flavonoids apigenin and quercetin inhibit melanoma growth and metastatic potential. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2000;87:595–600. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20000815)87:4<595::aid-ijc21>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon JR, Tapias V, Na HM, Honick AS, Drolet RE, Greenamyre JT. A highly reproducible rotenone model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of disease. 2009;34:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celik SE, Ozyurek M, Guclu K, Capanoglu E, Apak R. Identification and anti-oxidant capacity determination of phenolics and their glycosides in elderflower by on-line HPLC-CUPRAC method. Phytochemical analysis : PCA. 2014;25:147–154. doi: 10.1002/pca.2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler RF, Freeman L, Hooper SN. Herbal Remedies of the Maritime Indians. Journal of ethnopharmacology. 1979;1:49–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(79)90016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HC, Churchwell MI, Delclos KB, Newbold RR, Doerge DR. Mass spectrometric determination of Genistein tissue distribution in diet-exposed Sprague-Dawley rats. J Nutr. 2000;130:1963–1970. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.8.1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Wang SJ. Hypericin, the active component of St. John’s wort, inhibits glutamate release in the rat cerebrocortical synaptosomes via a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway. European journal of pharmacology. 2010;634:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]