The monobactam scaffold is attractive for the development of new agents to treat infections caused by drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria because it is stable to metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs). However, the clinically used monobactam aztreonam lacks stability to serine β-lactamases (SBLs) that are often coexpressed with MBLs.

KEYWORDS: Enterobacteriaceae, LYS228, beta-lactamases, drug resistance mechanisms, mechanisms of action, monobactam

ABSTRACT

The monobactam scaffold is attractive for the development of new agents to treat infections caused by drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria because it is stable to metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs). However, the clinically used monobactam aztreonam lacks stability to serine β-lactamases (SBLs) that are often coexpressed with MBLs. LYS228 is stable to MBLs and most SBLs. LYS228 bound purified Escherichia coli penicillin binding protein 3 (PBP3) similarly to aztreonam (derived acylation rate/equilibrium dissociation constant [k2/Kd] of 367,504 s−1 M−1 and 409,229 s−1 M−1, respectively) according to stopped-flow fluorimetry. A gel-based assay showed that LYS228 bound mainly to E. coli PBP3, with weaker binding to PBP1a and PBP1b. Exposing E. coli cells to LYS228 caused filamentation consistent with impaired cell division. No single-step mutants were selected from 12 Enterobacteriaceae strains expressing different classes of β-lactamases at 8× the MIC of LYS228 (frequency, <2.5 × 10−9). At 4× the MIC, mutants were selected from 2 of 12 strains at frequencies of 1.8 × 10−7 and 4.2 × 10−9. LYS228 MICs were ≤2 μg/ml against all mutants. These frequencies compared favorably to those for meropenem and tigecycline. Mutations decreasing LYS228 susceptibility occurred in ramR and cpxA (Klebsiella pneumoniae) and baeS (E. coli and K. pneumoniae). Susceptibility of E. coli ATCC 25922 to LYS228 decreased 256-fold (MIC, 0.125 to 32 μg/ml) after 20 serial passages. Mutants accumulated mutations in ftsI (encoding the target, PBP3), baeR, acrD, envZ, sucB, and rfaI. These results support the continued development of LYS228, which is currently undergoing phase II clinical trials for complicated intraabdominal infection and complicated urinary tract infection (registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under identifiers NCT03377426 and NCT03354754).

INTRODUCTION

The ongoing worldwide emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria, including carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), is increasingly recognized as a serious public health issue (1). Multidrug resistance in Gram-negative pathogens results from the accumulation of resistance mechanisms, including target mutations, active efflux, loss of outer membrane porins, and the expression of antibiotic-modifying enzymes that together can negate the therapeutic utility of clinically used antibiotics. Indeed, resistance to the current armamentarium of antibiotics has spawned a reluctant return to the use of more toxic antibiotics, such as colistin, as a last line of defense. Theoretically, novel antibacterial agents directed at new cellular targets could address some mechanisms of clinical resistance, but for a variety of reasons that approach has fallen short of expectations so far (2–5). Another strategy is to modify an effective and well-tolerated antibiotic, such as a β-lactam, to specifically address important mechanisms of resistance to that class of drug. A major mechanism of resistance to β-lactams is the expression of a broad range of ever-evolving serine β-lactamase enzymes (SBLs) that hydrolyze the β-lactam ring in penicillins, cephalosporins, monobactams, and, in some cases, carbapenems (6). Carbapenems were the least affected by this mechanism and are largely reserved for the treatment of difficult Gram-negative infections, but CRE are now spreading and pose a significant clinical challenge. Isolates producing Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), a class A SBL, are endemic to the United States, and numerous large-scale outbreaks have been reported (7). β-Lactamase inhibitors used in combination with cephalosporins and carbapenems can offset SBL activity, but there are no clinically available inhibitors for metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs), and the development of such inhibitors has been challenging (8). This is a serious concern (9) due to the emergence of MBLs such as New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1) in K. pneumoniae and Escherichia coli.

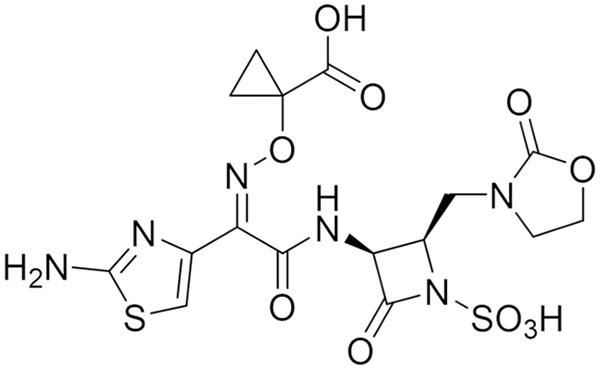

The monobactam class of β-lactams, exemplified by aztreonam (ATM), is unique in its intrinsic stability to MBLs (10, 11). However, ATM is not stable to SBLs, which are often expressed together with MBLs in resistant isolates. A strategy to address this is the combination of ATM with the β-lactamase inhibitor avibactam (AVI), where ATM is stable to MBLs and AVI will protect ATM from SBLs (12). This combination is currently undergoing phase III clinical trial studies (ClinicalTrials registration no. NCT03329092). An attractive alternative is to design a new monobactam that is stable to SBLs while retaining intrinsic stability to MBLs, providing a single-agent option for the treatment of CRE infections. With this in mind, we developed the novel monobactam LYS228 (13) (Fig. 1), which is currently in phase II clinical trials (ClinicalTrials registration no. NCT03354754). LYS228 was designed to retain stability to MBLs while gaining stability to a broad range of SBLs. Reflecting this, LYS228 exhibited a potent MIC90 of 2 μg/ml when tested against an Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolate panel comprised of 88 strains expressing ESBLs, KPCs, and MBLs (13) and a MIC90 of 1 μg/ml against a panel of 271 Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates (14). LYS228 appears to be less stable to a small number of β-lactamases tested, including VEB-1, -4, and -7 and PER-1, -2, and -4, which shifted susceptibility to LYS228 when expressed from a multicopy plasmid in isogenic strains of E. coli (MIC shifts from 0.125 to ≥8 μg/ml) (13). Smaller susceptibility shifts were mediated by expression of certain other enzymes using this isogenic panel, such as TEM-10, some OXA-family enzymes, and the class C enzyme DHA-1 (MIC shifts from 0.125 to ≤2 μg/ml) (13).

FIG 1.

Chemical structure of LYS228.

Here, we characterized the LYS228 mechanism of action and mutants selected in vitro with reduced susceptibility to LYS228. The antibacterial activity of the clinically established monobactam ATM is mediated mainly by inhibition of penicillin binding protein 3 (PBP3), interfering with peptidoglycan synthesis and cell division (septation) (15). Using a variety of approaches, we show that LYS228 retains this mechanism of antibacterial activity. The present study also examined the frequency of selecting single-step spontaneous mutants with decreased susceptibility to LYS228 or comparator antibiotics in 12 strains, comprised of E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Enterobacter cloacae expressing various β-lactamases. The decrease in susceptibility of E. coli after 20 serial passages in LYS228 or comparator antibiotics was also assessed, and the cumulative mutations altering susceptibility were identified. Our results suggest that LYS228 largely ameliorates the specific concern of SBL-mediated resistance while not sacrificing fundamental benefits of the monobactam scaffold, such as mechanism of action, potency, and in vitro frequencies of selecting mutants with decreased susceptibility that are comparable to clinically used antibiotics.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

LYS228 inhibits PBP3 in E. coli.

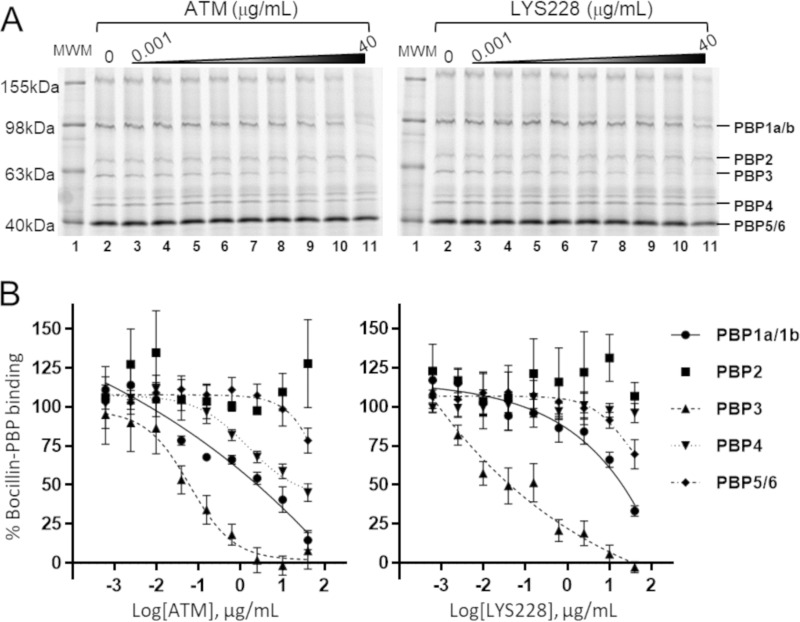

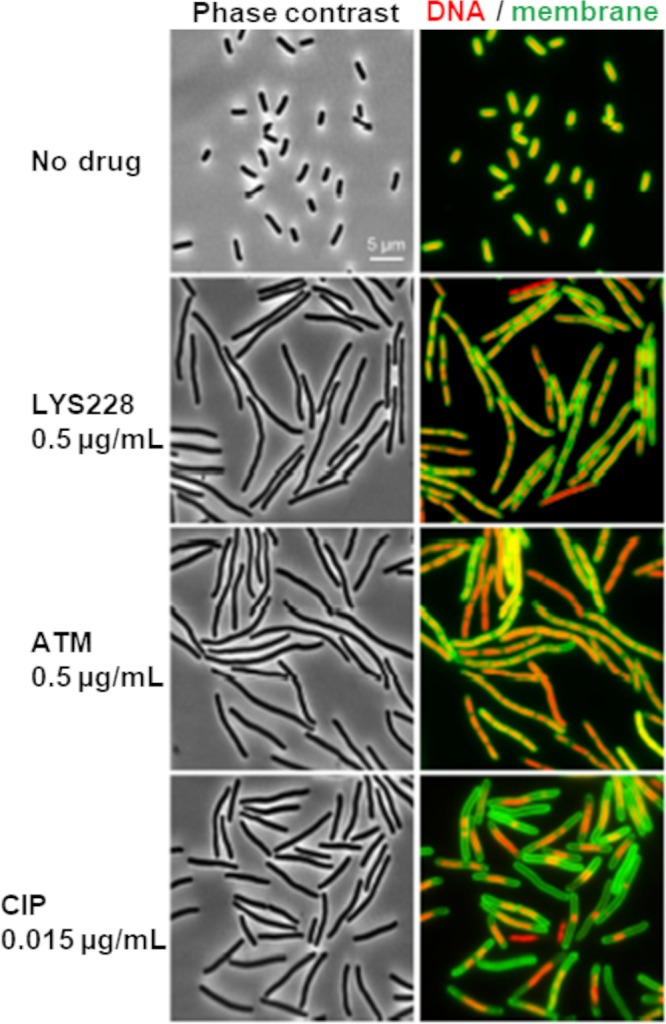

The well-characterized monobactam ATM undergoes covalent interaction with PBP3 that interferes with septal cell wall peptidoglycan synthesis and ultimately blocks cell division (15). To determine if this clinically validated mechanism of action was retained by LYS228, binding to PBPs was examined for LYS228 and ATM via a well-established gel-based PBP binding assay using crude bacterial membranes (Fig. 2A). Both compounds bound PBP3 with the highest affinity (Fig. 2B), indicating that PBP3 is their main cellular target. Each compound also bound PBP1a/b and PBP5/6 to a lesser extent. ATM appeared to engage PBP1s at somewhat higher affinity than did LYS228. Neither compound engaged PBP2 in this study. These results suggested that the antibacterial mechanism of LYS228 is similar to that of ATM and is primarily mediated by inhibition of PBP3. Inhibition of PBP3 is known to induce characteristic morphological changes in E. coli cells consisting of extensive filamentation combined with clearly segregated chromosomal DNA, reflecting an inability of cells to properly divide (16, 17). This contrasts with the filamentation phenotype induced by fluoroquinolones that is caused by upregulation of the SOS response upon interference with DNA replication (18). In the latter case the DNA appears condensed due to impairment of chromosome replication and segregation. Treatment of the cells with either LYS228 or ATM clearly induced the morphological changes expected of PBP3 inhibition, distinct from the phenotype induced by exposure to ciprofloxacin (Fig. 3). These results provided additional evidence that the antibacterial mechanism of PBP3 inhibition had been retained in LYS228. Having established that PBP3 is the primary cellular target of LYS228, the kinetics of LYS228 binding to purified E. coli PBP3 were compared to those of ATM using a rapid-mixing stopped-flow fluorimetry approach that measures compound binding-induced tryptophan signal quenching in PBP3 (Table 1). Interaction of β-lactam antibiotics with PBP3 initiates with a noncovalent interaction (represented by Kd) (Table 1), followed by an acylation of the PBP3 active-site serine (derived acylation rate, or k2) (Table 1). These values were similar for LYS228 and ATM, resulting in similar binding efficiencies for both compounds (k2/Kd of 367,504 and 409,230, respectively; Table 1). As expected for cefsulodin, which does not interact with PBP3 (19), no binding was detected by this method.

FIG 2.

(A) Binding of LYS228 or ATM to PBPs, measured qualitatively by gel-based PBP binding assay. (B) Densitometry analysis for PBP binding represents the means from 4 determinations (± standard errors of the means). Both compounds mainly bound PBP3, with lower but detectable binding to PBP1a/b and PBP5/6. ATM bound PBP1a/b with slightly higher affinity than did LYS228. Neither compound showed any detectable binding to PBP2.

FIG 3.

Morphology of E. coli cells exposed to LYS228 or control compounds. LYS228 and ATM caused cell filamentation with segregated chromosomal DNA (compare to CIP treatment), suggesting blocked cell division.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic and equilibrium binding constants for compounds binding to E. coli PBP3 determined by stopped-flow fluorimetrya

| Compound | k2 (s−1) | 95% CI (s−1) | Kd (μM) | 95% CI (μM) | k2/Kd (s−1 M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LYS228 | 162.4 ± 26.4 | 78.4 to 246.4 | 441.9 ± 90 | 153.6 to 730.3 | 367,504.0 |

| ATM | 147.2 ± 5.9 | 128.4 to 166.1 | 359.7 ± 20 | 298.9 to 420.5 | 409,229.9 |

| CFS | <10 | NA | ≫1,000 | NA | NA |

CI, confidence interval. NA, not applicable due to insufficient binding.

Selection of spontaneous mutants with decreased susceptibility to LYS228.

The frequency of selecting spontaneous mutants in vitro with reduced LYS228 susceptibility was determined and compared to that of clinically used comparator antibiotics. Twelve strains were tested, comprising 5 E. coli (NB27001, NB27119, NB27403, NB27169, and NB27306 [Table 2]), 6 K. pneumoniae (NB29001, NB29002, NB29082, NB29084, NB29257, and NB29268 [Table 2]), and 1 E. cloacae (NB25055 [Table 2]) strain. Most of these expressed clinically relevant β-lactamases. Comparator antibiotics were meropenem (MEM) and/or tigecycline (TGC), depending on the strain, and selections were carried out at 4× and 8× the broth MIC for all antibiotics. Note that ATM was not used as a comparator here, since several strains expressed β-lactamase(s) that impacted the potency of this antibiotic. No mutants were selected by LYS228 at 8 times the MIC (frequency of <2.5 × 10−9). At 4× the MIC, only one E. coli strain (NB27119; frequency of 4.2 × 10−9) (Table 3) and one K. pneumoniae strain (NB29002; frequency of 1.8 × 10−7) (Table 3) yielded mutants on the LYS228 concentrations tested. Mutants were selected on MEM and TGC in several strains at 4× and 8× the MIC at frequencies ranging from 10−7 to 10−8 (Table 3). Therefore, the frequency of selection of spontaneous mutants by LYS228 was comparable to selection with these marketed antibiotics.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Straina | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or referenceb |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| NB27001 | ATCC 25922, CLSI quality control strain | ATCC |

| NB27331 | BL21(DE3) | Novagen |

| NB27233 | BL21(DE3) ΔlamB, ΔompF, ΔompC, ΔompA | 60 |

| NB27273 | BW25110 psp::Kmr | E. coli Genetic Stock Center (Yale) |

| NB27043 | AG100 | Stuart Levy |

| NB27006 | AG100, ΔacrAB | Stuart Levy |

| NB27007 | AG100, acrR mutant, acrAB overexpressor | Stuart Levy |

| NB27119 (TEM-12) | blaTEM-12, culture is unstable and loses blaTEM-12 | NVS collection |

| NB27119-CDJ0129 (TEM-12) | NB27119 (TEM-12) baeS(D156Y) | This study |

| NB27119-CDJ0130 (TEM-12) | NB27119 (TEM-12) baeS(I170M) | This study |

| NB27119 (TEM-1 minus) | NB27119 derivative that has lost blaTEM-12 | This study |

| NB27119-JBA0001 | NB27119 (TEM-12 minus), baeS (12-bp deletion); selected on LYS228 | This study |

| NB27119-JBA0002 | NB27119 (TEM-12 minus), baeS(V270G), selected on LYS228 | This study |

| NB27119-CDJ0138 | NB27119 (TEM-12 minus), CAGTATAAAA to C 124 bp upstream of acrD (acrD expression upregulated) | This study |

| NB27169 | blaKPC-3 | NVS collection |

| NB27235 | blaCTX-M-15 | JMI Laboratories |

| NB27306 | blaNDM-1 | ATCC 1001728 |

| NB27001-JBC0001 | Serial passage mutant (LYS228); ftsI(Q536L), baeR(L22Q), envZ(L84Q), acrD(R629H), sucB(P27T), rfaI(Y112C), selected on LYS228 (serial passage) | This study |

| NB27001-JBC0006 | Serial passage mutant (ATM); ftsI(A413V), baeR(P111Q), rseA(W33R), rfaH(T72P), and yhbM (stop after W24), selected on ATM (serial passage) | This study |

| NB27001-JBC0029 | Serial passage mutant (MEM) | This study |

| NB27001-JBC0036 | Serial passage mutant (TGC) | This study |

| NB27001-JRW0008 | rfaI(Y112C) | This study |

| NB27001-JRW0009 | sucB(P27T) | This study |

| NB27001-JWM0093 | acrD(R629H) | This study |

| NB27001-JWM0094 | baeR(L22Q) | This study |

| NB27001-JWM0095 | ftsI(Q536L) | This study |

| NB27001-JWM0096 | envZ(L84Q) | This study |

| NB27001-JRW0027 | baeR(L22Q) acrD(R629H) double mutant | This study |

| NB27273-TUT0001 | ampC promoter mutation; upregulates expression of chromosomal ampC | This study |

| K. pneumoniae | This study | |

| NB29001 | blaSHV-18 | ATCC 700603 |

| NB29002 | blaSHV-1 | ATCC 43816 |

| NB29082 | blaKPC-2 | ATCC BAA-1903 |

| NB29084 | blaCTX-M-14 | JMI Laboratories |

| NB29257 | blaCMY-2, blaSHV-1, blaTEM-1-like | NVS collection |

| NB29268 | blaNDM-1 | ATCC 1002565 (61) |

| NB29002-JBA0001 | ramR (36-bp deletion), selected on LYS228 | This study |

| NB29002-JBA0004 | baeS(V295G), selected on LYS228 | This study |

| NB29002-JBA0007 | cpxA(L57V); VK055_RS01255; (I58T), selected on LYS228 | This study |

| NB29002-JBA0008 | baeS(V295G) single, selected on LYS228 | This study |

| NB29002-JBA0010 | ramR (406-bp deletion) single, selected on TGC | This study |

| NB29002-JWK0175 | cpxA(L57V), engineered | This study |

| NB29002-JWK0179 | VK055_RS01255 (I58T), engineered | This study |

| NB29002-CDY0308 | Separated from NB29002-JBA0007; cpxA(L57V); VK055_RS01255 (I58T) | This study |

| NB29002-CDY0309 | Separated from NB29002-JBA0007; cpxA(L57V); VK055_RS01255 (I58T); baeR(E19K) | This study |

| E. cloacae | ||

| NB25055 | blaCMY-2 | NVS collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| pNOV141 | P15A ori, lacI, araC, sacB, Ptac::cas9 (S. pyogenes), Para::gambet-exo-ori60a, bla | MH697720 |

| pNOV145 | Ptac(lacO-)::cpxA gRNA, sacB, aacC1(Gmr) | MH697721 |

| pNOV146 | Ptac(lacO-):: VK055_RS01255 gRNA, sacB, aacC1(Gmr) | MH697722 |

| pJW20 | Ptac(lacO-)::rfaI gRNA, sacB, aacC1(Gmr), ColE1 ori | MH697723 |

| pJW24 | Ptac(lacO-)::sucB gRNA, sacB, aacC1(Gmr), ColE1 ori | MH697724 |

| pMM21 | Ptac(lacO-)::acrD gRNA, sacB, aacC1(Gmr), ColE1 ori | MH697725 |

| pMM22 | Ptac(lacO-)::baeR gRNA, sacB, aacC1(Gmr), ColE1 ori | MH697726 |

| pMM23 | Ptac(lacO-)::ftsI gRNA, sacB, aacC1(Gmr), ColE1 ori | MH697727 |

| pMM24 | Ptac(lacO-)::envZ gRNA, sacB, aacC1(Gmr), ColE1 ori | MH697728 |

Novartis internal strain designations are used.

NVS, Novartis.

TABLE 3.

Frequency of spontaneous single-step mutant selection with LYS228, MEM, and TGCa

| Strain (β-lactamase) and selecting compound | MIC (μg/ml) | Spontaneous mutant frequency at: |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 4× MIC | 8× MIC | ||

| E. coli NB27001, ATCC 25922 | |||

| LYS228 | 0.25 | <4.3 × 10−9 | <4.3 × 10−9 |

| MEM | 0.03 | <3.3 × 10−9 | <3.3 × 10−9 |

| TGC | 0.125 | <2.9 × 10−9 | <2.9 × 10−9 |

| E. coli NB27119 (TEM-12)b | |||

| LYS228 | 0.125 | 4.2 × 10−9 | <4.2 × 10−9 |

| MEM | 0.03 | <3.1 × 10−9 | <3.1 × 10−9 |

| TGC | 0.25 | <2.5 × 10−9 | <2.5 × 10−9 |

| E. coli NB27119 (TEM-12)c | |||

| LYS228 | 0.125 | 1.6 × 10−8 | <5.3 × 10−9 |

| MEM | 0.03 | 1.1 × 10−8 | <5.3 ×10−9 |

| TGC | 0.25 | <5.3 ×10−9 | <5.3 × 10−9 |

| E. coli NB27119 (no TEM-12)d | |||

| LYS228 | 0.125 | 7.4 × 10−9 | ND |

| E. coli NB27169 (KPC-3) | |||

| LYS228 | 0.5 | <4.5 × 10−9 | <4.5 × 10−9 |

| TGC | 0.125 | <1.4 × 10−8 | <1.4 × 10−8 |

| E. coli NB27235 (CTX-M-15) | |||

| LYS228 | 0.25 | <1.1 × 10−8 | <1.1 × 10−8 |

| MEM | 0.03 | <4.5 × 10−9 | <4.5 × 10−9 |

| TGC | 0.5 | 4.6 × 10−8 | <3.8 × 10−9 |

| E. coli NB27306 (NDM-1) | |||

| LYS228 | 1 | <3.8 × 10−9 | <3.8 × 10−9 |

| TGC | 0.25 | 2.1 × 10−8 | <2.6 × 10−9 |

| K. pneumoniae NB29001 (SHV-18) | |||

| LYS228 | 0.25 | <4.5 × 10−9 | <4.5 × 10−9 |

| MEM | 0.03 | 2.4 × 10−7 | 1.2 × 10−7 |

| K. pneumoniae NB29002, ATCC 43816 | |||

| LYS228 | 0.06 | 1.8 × 10−7 | <9.1 × 10−9 |

| MEM | 0.06 | <1.1 × 10−8 | <1.1 × 10−8 |

| TGC | 0.25 | 2.9 × 10−7 | 8.9 × 10−8 |

| K. pneumoniae NB29082 (KPC-2) | |||

| LYS228 | 0.5 | <5.0 × 10−9 | <5.0 × 10−9 |

| TGC | 0.5 | <5.6 × 10−9 | <5.6 × 10−9 |

| K. pneumoniae NB29084 (CTX-M-14) | |||

| LYS228 | 0.5 | <3.1 × 10−9 | <3.1 × 10−9 |

| MEM | 0.03 | 1.0 × 10−7 | 9.4 × 10−8 |

| K. pneumoniae NB29257 (CMY-2, SHV-1, TEM-1) | |||

| LYS228 | 0.25 | <5.3 × 10−9 | <5.3 × 10−9 |

| MEM | 0.03 | 2.0 × 10−7 | <4.2 × 10−9 |

| TGC | 1 | 2.4 × 10−7 | <3.3 × 10−9 |

| K. pneumoniae NB29268 (NDM-1) | |||

| LYS228 | 0.25 | <2.5 × 10−9 | <2.5 × 10−9 |

| TGC | 1 | 2.4 × 10−7 | <2.5 × 10−9 |

| E. cloacae NB25055 (CMY-2) | |||

| LYS228 | 1 | <3.8 × 10−9 | <3.8 × 10−9 |

| MEM | 0.03 | 1.3 × 10−7 | <7.1 × 10−9 |

| TGC | 0.25 | 2.4 × 10−7 | <4.2 × 10−9 |

Strains from which mutants were selected on LYS228 are indicated in boldface. In instances where either MEM or TGC was not tested, susceptibility to that agent was too low to allow use in selection experiments. ND, not done.

Selection from heterogenous population of NB27119.

Selection from isolate NB27119 harboring TEM-12.

Selection from isolate NB27119 that had lost TEM-12.

Two E. coli mutants (NB27119-JBA0001 and NB27119-JBA0002) and four K. pneumoniae mutants (NB29002-JBA0001, NB29002-JBA0004, NB29002-JBA0007, and NB29002-JBA0008) were recovered for further study (Table 4). Antibiotic susceptibility profiles for these mutants are shown in Table 4. Notably, the LYS228 MIC did not exceed 2 μg/ml for any of these mutants. Addition of AVI at 4 μg/ml did not restore the LYS228 susceptibility of any of these mutants to that of their parental strains (data not shown), suggesting that reduced susceptibility was not related to upregulated expression of β-lactamases (chromosomal blaAmpC in NB27119 or blaSHV-1 in NB29002). This is consistent with the reported stability of LYS228 to most SBLs (13). The two parent strains of these sets of mutants (E. coli NB27119 and K. pneumoniae NB29002) were sensitive to ATM, so selected mutants could also be tested for shifts in susceptibility to ATM. Consistent with the structural and mechanistic similarities between LYS228 and ATM, all mutants were also less susceptible to ATM, and the ATM MIC did not exceed 1 μg/ml for any mutant (Table 4). There was a modest decrease in susceptibility to ceftazidime for all mutants, but the MIC did not exceed 1 μg/ml. No significant change in susceptibility to imipenem (IPM) or levofloxacin (LVX) was seen. One K. pneumoniae mutant, NB29002-JBA0001, showed decreased susceptibility to TGC (MIC 8 μg/ml) (Table 4). TGC is a known substrate of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump of several pathogens (20–23), suggesting that the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump is upregulated in this mutant, although this requires further confirmation.

TABLE 4.

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles for E. coli and K. pneumoniae spontaneous mutants selected on LYS228a

| Strain | Gene mutated (aa substitution) | MIC (μg/ml) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LYS228 | ATM | CAZ | IPM | LVX | CHL | TGC | ||

| E. coli | ||||||||

| NB27119 (minus TEM-12) | Parent (minus TEM-12) | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 8 | 0.5 |

| NB27119-JBA0001* (TEM-12 minus) | baeS (12-bp deletion)** | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 8 | 0.5 |

| NB27119-JBA0002 (TEM-12 minus) | baeS(V270G) | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 8 | 0.5 |

| NB27119-CDJ0138 | acrD promoter region | 4 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 4 | 0.25 |

| NB27119 (TEM-12) | Parent (TEM-12) | 0.25 | 2 | 32 | 0.25 | 0.06 | >64 | 0.25 |

| NB27119-CDJ0129 (TEM-12) | baeS(D156Y) | 2 | 2 | 32 | 0.125 | 0.06 | >64 | 0.25 |

| NB27119-CDJ0130 (TEM-12) | baeS(I170 M) | 2 | 2 | 32 | 0.125 | 0.06 | >64 | 0.25 |

| K. pneumoniae | ||||||||

| NB29002 | Parent | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 8 | 0.5 |

| NB29002-JBA0001* | ramR (36-bp deletion) | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | >64 | 8 |

| NB29002-JBA0010* | ramR (406-bp deletion)**, selected on TGC | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.25 | 1 | >64 | 8 |

| NB29002-JBA0004* | baeS(V295G)** | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 8 | 0.5 |

| NB29002-JBA0008* | baeS(V295G)** | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | ≤0.03 | 8 | 0.5 |

| NB29002-JBA0007* | cpxA(L57V); VK055_RS01255; (I58T) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 16 | 1 |

| NB29002-JWK0175 | cpxA(L57V) | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 8 | 0.5 |

| NB29002-JWK0180 | VK055_RS01255; (I58T) | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 8 | 0.5 |

| NB29002-CDY0308 | cpxA(L57V); VK055_RS01255; (I58T) | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 8 | 0.5 |

| NB29002-CDY0309 | cpxA(L57V) VK055_RS01255; (I58T) baeR(E19K) | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 8 | 0.5 |

E. coli mutants were selected on 0.5 μg/ml LYS228, and K. pneumoniae mutants were selected on 0.25 μg/ml LYS228. An asterisk indicates mutation identified by whole-genome sequencing. Two asterisks indicate this was the only mutation identified in this mutant by genome sequencing. All mutations were confirmed by PCR and sequencing.

Mutations mediating decreased susceptibility to LYS228 in spontaneous E. coli mutants.

Whole-genome sequencing of NB27119-JBA0001 identified a 12-bp deletion in baeS, which encodes the sensor kinase component of the BaeRS two-component cell wall stress regulatory pair. No other mutations were found, suggesting that this mutation was responsible for decreased susceptibility to LYS228. Mutant NB27119-JBA0002 also harbored a mutation in baeS that encoded BaeS V270G. Both mutants demonstrated modest shifts in susceptibility to LYS228, ATM, and ceftazidime (CAZ), with no shift in susceptibility to IPM, LVX, chloramphenicol (CHL), or TGC (Table 4). Susceptibility of the parent strain NB27119 to CHL and CAZ was found to be variable. We determined that NB27119 was unstable and lost blaTEM-12 (determined by PCR) at a high frequency, coincident with becoming more susceptible to CAZ and CHL (compare NB27119 [TEM-12 minus] and NB27119 [TEM-12]) (Table 4). This suggested that blaTEM-12 resided on a genetic element with other resistance determinants that could be lost at high frequency. The susceptibility results for CAZ and CHL against NB27119-JBA0001 and -JBA0002 indicated that they have been selected from the TEM-12-minus strain background. The selection experiment was repeated for separate NB27119 (TEM-12) and NB27119 (TEM-12 minus) isolates and yielded spontaneous mutant frequencies of 1.6 × 10−8 and 7.4 × 10−9 (Table 3), in line with previous results. Six of six mutants picked from the NB27119 (TEM-12) selection harbored a mutation in baeS encoding an amino acid substitution (D156Y and I170M for strains NB27119-CDJ0129 and NB27119-CDJ0130) (Table 4) and L291P, A265P, or P255Q, and one had a 12-bp deletion within baeS. Mutants began to lose blaTEM-12 unless maintained on CHL. Four of five mutants picked from the NB27119 (TEM-12 minus) selection harbored a mutation in baeS encoding amino acid substitutions (A172P, A224E, A191P, or G261N), also consistent with the original selection described above. The remaining mutant harbored a CAGTATAAAA-to-C change 124 bp upstream of the efflux pump gene acrD (NB27119-CDJ0138) (Table 4). Therefore, mutations in baeS are the predominant single-step mechanism selected by LYS228 in this strain of E. coli. Intriguingly, mutations in baeS mediated an approximately 8-fold shift in LYS228 susceptibility regardless of whether TEM-12 was present, whereas ATM susceptibility was only decreased in the TEM-12-minus strain background (Table 4).

The BaeSR two-component system controls expression of a small regulon that includes the mdtABCD-baeSR, acrD, and spy genes (24, 25). The mdtABC and acrD genes encode resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) family efflux pump components whose substrates include β-lactam antibiotics (26, 27). This suggested that upregulation of one or both of these pumps could be mediating the decrease in susceptibility to LYS228, ATM, and ceftazidime in these mutants. Overexpression of BaeR in an E. coli strain lacking the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump was previously reported to decrease susceptibility to a range of β-lactams, including ATM and CAZ, and this was mediated by MdtABCD and AcrD (26). Consistent with an ability of AcrD to reduce susceptibility to LYS228, mutant NB27119-CDJ00138, which had a genetic deletion upstream of acrD, was approximately 60-fold upregulated for acrD expression (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and was 32-fold and 16-fold less susceptible to LYS228 and ATM, respectively (Table 4). Susceptibility of E. coli to LYS228 was not affected by deletion of acrAB or by deletion of acrR, which upregulates pump expression (Table S1), suggesting that AcrAB-TolC is not a significant determinant of decreased susceptibility in E. coli.

An AmpC-upregulated mutant from our collection (previously selected using ATM) was less susceptible to ATM but not to LYS228 (strain NB27273-TUT0001) (Table S1), consistent with improved stability of LYS228 to this enzyme compared to that of ATM and with the apparent lack of selection of AmpC upregulation by LYS228 in E. coli in these studies. Finally, no mutations were identified in genes encoding major porins, the presumed uptake pathway of LYS228 across the outer membrane. However, E. coli deleted for ompC and ompF was 4-fold less susceptible to LYS228, and a strain deleted for ompC, ompF, ompA, and lamB was 32-fold less susceptible (Table S1). This supports the notion that porins are required for LYS228 to gain entry into cells but that multiple porins can be accessed. This may be consistent with the lack of porin gene mutations among the single-step mutants examined here.

Mutations mediating decreased susceptibility to LYS228 in K. pneumoniae spontaneous mutants.

Genome sequencing revealed a 36-bp deletion in ramR in mutant NB29002-JBA0001 (Table 4). Mutations in the repressor gene ramR can upregulate expression of the positive activator RamA, which in turn upregulates expression of the acrAB-tolC and oqxAB-tolC efflux pump genes along with other regulatory changes; ramR mutations have also been identified in clinical isolates (22, 28–32). RamA-mediated upregulation of AcrAB-TolC and/or OqxAB-TolC has also been reported to decrease susceptibility to a range of β-lactams, including ATM (33). Furthermore, NB29002-JBA0001 was also less susceptible to TGC and CHL, known substrates of AcrAB-TolC that are structurally unrelated to LYS228. Therefore, decreased susceptibility to LYS228 in both ramR mutants was likely due to upregulated efflux. Consistent with this, mutant NB29002-JBA0010, selected on TGC and having a 406-bp deletion in ramR as the only alteration found by genome sequencing, was less susceptible to LYS228 (Table 4). As noted above, mutants upregulated for AcrAB-TolC expression were not selected in vitro in E. coli by LYS228, and AcrAB-TolC pump status did not seem to significantly impact LYS228 susceptibility in E. coli (Table S1). This suggests that AcrAB-TolC is a more important determinant of LYS228 susceptibility in K. pneumoniae. However, additional concomitant regulation of other factors, such as the OqxAB-TolC pump, within the ramR-ramA regulon (E. coli lacks ramR-ramA and oqxAB) may be involved, and this needs to be further explored.

Mutants NB29002-JBA0004 and NB29002-JBA0008 (LYS228 MIC of 1 to 2 μg/ml, compared to a MIC of 0.06 μg/ml for the parent) (Table 4) harbored a mutation in baeS encoding a V295G substitution as the only change identified by genome sequencing. Four additional mutants from this experiment also harbored the same mutation and had antibiotic susceptibility profiles similar to those of NB29002-JBA0004 and NB29002-JBA0008 (data not shown). The baeS mutants were also approximately 8-fold less susceptible to ATM and CAZ (Table 4). As discussed above, the BaeSR two-component system in E. coli regulates the expression of efflux pumps to provide resistance to antibacterial compounds, and this has also been reported for other organisms, such as Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (34) and Acinetobacter baumannii (35). The regulon of the BaeSR two-component system in K. pneumoniae has not been fully characterized, and the identification of the specific element(s) within the regulon that decrease susceptibility to LYS228 awaits further study.

One mutant, NB29002-JBA0007, had mutations in cpxA (encoding a CpxA L57V amino acid substitution) and in a putative gene encoding a hypothetical protein of unknown function (VK055_RS01255; I58T substitution; according to the published genome sequence of NB29002 [36]). This mutant was 32-fold less susceptible to LYS228 (MIC 2 μg/ml) and 16-fold less susceptible to ATM (Table 4). To determine if either mutation independently altered susceptibility to these compounds, they were engineered into the genome of K. pneumoniae NB29002 using a clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat(s) (CRISPR) approach. Strain NB29002-JWK0175 (CpxA L57V variant) was 8-fold less susceptible to LYS228 (MIC, 0.5 μg/ml) (Table 4), whereas the VK055_RS01255 (I58T) alteration mediated only a 2-fold shift (NB29002-JWK0180) (Table 4).

CpxA is the sensor kinase of the two-component envelope stress response signal transduction system CpxAR, which is distributed among many Gram-negative pathogens. The CpxAR regulon is complex and has been associated with a diverse range of phenomena, including adaptation to protein misfolding, membrane lipid composition, virulence factor expression, peptidoglycan synthesis, and resistance to antibiotics, including β-lactams, depending on the pathogen (26, 37–43). Among the regulated genes are several encoding components of RND efflux pumps and outer membrane porins. Although the overall CpxAR regulon has not been elucidated in K. pneumoniae, deletion of the cpxAR genes was reported to increase susceptibility to β-lactams and reduce expression of the acrB, acrD, eefB, and kpnEF efflux pump genes, suggesting a link between the CpxAR system and efflux-mediated β-lactam resistance (39, 44). The CpxAR system was also implicated in regulation of the K. pneumoniae OmpC porin homolog (39), which could impact susceptibility to β-lactams. Upregulated efflux and/or porin downregulation may therefore contribute to decreasing susceptibility to LYS228 in this mutant, but this remains to be further explored. However, the originally selected cpxA/VK055_RS01255 mutant NB29002-JBA0007 or the engineered single cpxA mutant NB29002-JWK0175 was not less susceptible to TGC, a hallmark of AcrAB-TolC upregulation, implying that this pump does not play a role. Intriguingly, a recent report associated a mutation in PA3206, encoding a homolog of CpxA in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, with decreased susceptibility to ATM (45). Mutations in cpxA were also shown to suppress the viability defect and drug hypersensitivity engendered by deletion of the LytC-type peptidoglycan amidase genes amiA and amiB, important for divisome function in P. aeruginosa (46), raising the possibility of a more complex role of the CpxAR regulon in altering susceptibility to agents interfering in cell wall synthesis and cell division. The decrease in LYS228 susceptibility of the engineered cpxA mutant NB29002-JWK0175 (MIC of 0.5 μg/ml) was not of the same magnitude as that of the originally selected mutant, NB29002-JBA0007 (MIC of 2 μg/ml).

Reanalysis of the genome sequencing of NB29002-JBA0007 with a lower cutoff for single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection revealed a lower-quality SNP call within baeR (encoding E19K), suggesting the frozen stock was a mixed culture. Streaking NB29002-JBA0007 from the frozen stock indeed revealed a mixed population comprised of the original cpxA/VK055_RS01255 mutants (NB29002-CDY0308) (Table 4) and ones having the additional baeR (E19K) mutation (NB29002-CDY0309) (Table 4), suggesting that the baeR mutation emerged from the original cpxA mutant. Mutant NB29002-CDY0308 was 2-fold less susceptible to LYS228 and had no change in susceptibility to ATM relative to the parent, NB29002. Mutant NB29002-CDY0309 was 8-fold less susceptible to LYS228 and 4-fold less susceptible to ATM, suggesting that the baeR mutation was involved in decreasing susceptibility (Table 4). The emergence and contribution of the baeR mutation in NB29002-CDY0309 is consistent with BaeR being the response regulator partner of BaeS, described above as an important determinant of decreased LYS228 susceptibility in E. coli and K. pneumoniae. This also suggested that CpxAL57V is not well tolerated in K. pneumoniae, and we observed that growth of the engineered cpxA mutant NB29002-JWK0175 was impaired on agar plates. Faster-growing, LYS228-susceptible mutants emerged on plates, and these had either reverted to wild-type cpxA, acquired an early stop in cpxA [CpxA (L57V, A364*)], or had acquired a putative suppressor mutation in cpxR (encoding the response regulator partner of CpxA). The precise mechanism of decreased susceptibility to LYS228 in K. pneumoniae caused by the mutation in cpxA and the possible interrelationship of the CpxA and BaeRS regulatory pathways is under further investigation.

Decreased susceptibility to LYS228 emerging in E. coli during serial passaging.

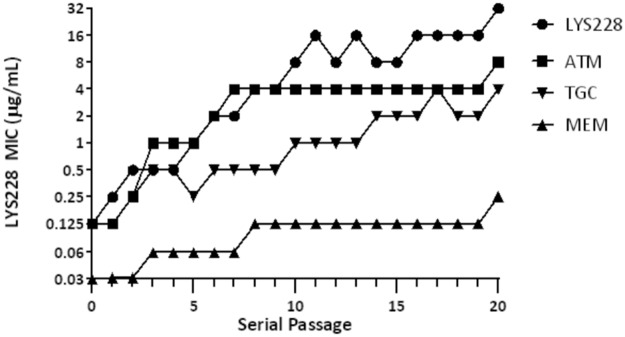

To explore the potential for decreased susceptibility to LYS228 resulting from the cumulative effect of multiple mutations in E. coli, strain NB27001 (Table 2) was subjected to 20 daily passages in the presence of LYS228, ATM, MEM, or TGC. Strain NB27001 was chosen since it does not possess any β-lactamases beyond its chromosomal ampC. Therefore, these studies assessed the potential only for selecting upregulation of ampC or the emergence of non-β-lactamase-based mechanisms. It took five serial passages for the culture to show a 4-fold decrease in susceptibility to LYS228 from that of the parent strain. After 20 passages susceptibility had decreased 256-fold (final MIC of 32 μg/ml and a starting MIC of 0.125 μg/ml) (Fig. 4). In comparison, susceptibility to the related molecule ATM decreased 64-fold after 20 passages (final MIC of 16 μg/ml with a starting MIC of 0.125) (Fig. 4). Susceptibility to MEM and TGC decreased 8-fold and 32-fold after 20 passages. An isolate with reduced susceptibility to each compound was recovered after passage day 20, and broth MICs were determined for several antibiotics (Table 5). For the isolate selected on LYS228 (NB27001-JBC0001), the MIC increased 256-fold for LYS228, 64-fold for ATM, and 16-fold for CAZ. The MIC for IPM decreased 4-fold, and there was no change for MEM, LVX, CHL, or TGC. For the isolate selected on ATM (NB27001-JBC0006), the MIC increased 128-fold for ATM and LYS228 and 4-fold for ceftazidime. This isolate was about 2- to 4-fold more susceptible to IPM, LVX, and CHL. For NB27001-JBC0029 selected on MEM, the MICs increased 4-fold for MEM and IPM and 32-fold and 8-fold, respectively, for LYS228 and ATM. The MIC values of LVX and CHL increased by 4-fold, while susceptibility to TGC did not change. For NB27001-JBC0036 selected on TGC, the MIC values of TGC increased 16-fold, whereas the MIC values of ATM, MEM, IPM, and LVX changed by no more than 2-fold. The MIC values of LYS228 and CHL increased 8-fold for this mutant, while the MIC of ceftazidime increased 4-fold.

FIG 4.

Decrease in E. coli NB27001 susceptibility to LYS228 and comparator antibiotics over 20 serial passages. Passage 0 represents the initial LYS228 MIC for NB27001.

TABLE 5.

Antibacterial susceptibilities of E. coli mutants selected after 20 serial passages

| Strain | Selection | MIC (μg/ml) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LYS228 | ATM | CAZ | MEM | IPM | LVX | CHL | TGC | ||

| NB27001 | None | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.015 | 4 | 0.125 |

| NB27001-JBC0001 | LYS228 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 8 | 0.125 |

| NB27001-JBC0006 | ATM | 16 | 16 | 4 | 0.06 | 0.06 | ≤0.008 | 2 | 0.125 |

| NB27001-JBC0029 | MEM | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.125 | 1 | 0.06 | 16 | 0.25 |

| NB27001-JBC0036 | TGC | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 32 | 2 |

Cumulative mutations emerging in E. coli during serial passage that decrease susceptibility to LYS228.

To identify mutations decreasing susceptibility to LYS228 and ATM that emerged during serial passage, culture from passage 20 was streaked onto solid medium, and five isolated colonies from each experiment were genome sequenced. Intriguingly, in each set, all five mutants had the same complement of mutations. Those selected on LYS228 (represented by NB27001-JBC0001; LYS228 MIC, 32 μg/ml; ATM MIC, 16 μg/ml) (Tables 5 and 6) had SNPs in ftsI (encoding Q536L), baeR (encoding L22Q), envZ (encoding L84Q), acrD (encoding R629H), sucB (encoding P27T), and rfaI (encoding Y112C). Those selected in ATM (represented by NB27001-JBC0006; LYS228 MIC, 16 μg/ml; ATM MIC, 16 μg/ml) (Tables 5 and 6) all had mutations in ftsI (encoding A413V), baeR (encoding P111Q), rseA (encoding W33R), rfaH (encoding T72P) and yhbM (encoding W24*), as well as frameshift mutations inactivating acrB, lrhA, and yghB.

TABLE 6.

Cumulative mutations decreasing susceptibility to LYS228 or ATM in E. coli over 20 serial passages

| Strain | Gene mutated (aa substitution) | MIC (μg/ml) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LYS228 (+ AVI) | ATM (+ AVI) | CAZ | CAZ/AVI | IPM | MEM | LVX | CIP | TGC | CHL | ||

| NB27001 | Parent | 0.125 (0.125) | 0.125 (0.125) | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.008 | 0.25 | 8 |

| NB27001-JBC0001a | Selected by LYS228; ftsI(Q536L), baeR(L22Q), envZ(L84Q), acrD(R629H), sucB(P27T), rfaI(Y112C) | 32 (8) | 16 (16) | 8 | 8 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.125 | 8 |

| NB27001-JWM0095 | ftsI(Q536L) | 0.5 (0.25) | 0.5 (0.25) | 2 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.008 | 0.125 | 4 |

| NB27001-JWM0094 | baeR(L22Q) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1) | 1 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.125 | 4 |

| NB27001-JWM0096 | envZ(L84Q) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.5 (1) | 1 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.25 | 4 |

| NB27001-JWM0093 | acrD(R629H) | 0.25 (0.25) | 0.25 (0.5) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.125 | 8 |

| NB27001-JRW0009 | sucB(P27T) | 0.125 (0.25) | 0.5 (0.25) | 0.5 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.5 | 8 |

| NB27001-JRW0008 | rfaI(Y112C) | 0.5 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0.5 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.008 | 0.5 | 8 |

| NB27001-JRW0027 | baeR(L22Q), acrD(R629H) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 | 2 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.25 | 4 |

| NB27001-JBC0006a | Selected by ATM; ftsI(A413V), baeR(P111Q), rseA(W33R), rfaH(T72P), yhbM(W24*), frameshifts in acrB, irhA, and yghB; | 16 (4) | 16 (8) | 4 | 2 | 0.06 | 0.06 | ≤0.008 | 0.008 | 0.125 | 2 |

| NB27001-JWM0101 | ftsI(A413V) | 1 (0.25) | 1 (0.5) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.008 | 0.25 | 4 |

| NB27001-JWK0180 | ftsI (YRIK insertion) | 0.5 (0.5) | 1 (1) | 1 | 2 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.008 | 0.125 | 4 |

| NB27001-JWK0181 | ftsI (YRIN insertion) | 0.5 (1) | 0.5 (1) | 1 | 2 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.008 | 0.06 | 8 |

Representative isolate of five that were genome sequenced and had the identical set of mutations. All mutations were confirmed by PCR and sequencing. Only ftsI(A413V) from NB27001-JBC006 was tested for impact on susceptibility to LYS228. Increased susceptibility to CHL in NB27001-JBC0006 is consistent with the identified frameshift mutation in acrB. Each individual mutation identified from the LYS228 serial passage was engineered into the genome of strain NB27001.

To establish which mutations in NB27001-JBC0001 could individually decrease susceptibility to LYS228, each was engineered separately back into strain NB27001 using a CRISPR approach. BaeRL22Q mediated an 8-fold decrease in susceptibility to LYS228 and ATM and also shifted susceptibility to CAZ (NB27001-JWM0094) (Table 6). FtsIQ536L, EnvZL84Q, and RfaIY112C yielded a 4-fold decreased susceptibility to LYS228 and ATM and shifted susceptibility to CAZ (NB27001-JWM0095, NB27001-JWM0096, and NB27001-JRW0008) (Table 6). AcrDR629H yielded a 2-fold decrease in susceptibility to LYS228 (NB27001-JWM0093) (Table 6), whereas there was no change for SucBP27T (NB27001-JRW0009) (Table 6). Growth curves of strains harboring these mutations in medium containing 0.5× MIC of LYS228 for the E. coli parent strain NB27001 also showed that all mutants except NB27001-JRW0009 grew better than the parent strain (Fig. S3A).

The emergence of a mutation in ftsI is consistent with PBP3 (encoded by ftsI) being a target of LYS228. The Q536L substitution may reduce target interaction with LYS228 (and ATM), but this remains to be shown in vitro. The ftsI mutation encoding A413V, which was selected by passaging in ATM (NB27001-JBC0006) (Table 6), was engineered into NB27001 and conferred a 4-fold decrease in susceptibility to both LYS228 and ATM (NB27001-JWM-0101) (Table 6). Mutations in ftsI (encoding YRIN or YRIK amino acid insertion) that reduce susceptibility to ATM in E. coli clinical isolates have been reported (47). We engineered these alterations into E. coli strain NB27001 and confirmed that they mediated an approximately 4-fold shift in susceptibility to LYS228 and a 4- to 8-fold shift to ATM (strains NB27001-JWK0180 and NB27001-JWK0181) (Table 6). Mutations in ftsI were also reported to emerge in E. coli during serial passaging in carbapenems (48) and in passaging of P. aeruginosa in ATM (45).

In this experiment, the only other mutated gene besides ftsI that emerged using either LYS228 or ATM was baeR, which encodes the response regulator of the BaeSR two-component envelope stress response system (37). Several of the single-step mutants described above had mutations in the baeR partner gene baeS, and a baeR mutation emerged in the cpxA mutant of K. pneumoniae, selected by LYS228 (NB29002-CDY0309 derived from NB29002-JBA0007). The appearance of a baeR mutation during serial passaging further implicates this two-component regulatory system in determining susceptibility to monobactams in E. coli and K. pneumoniae. The baeR mutation alone (strain NB27001-JWM0094) (Table 6) conferred an approximately 8-fold decrease in susceptibility to LYS228 and ATM (MIC of 0.5 to 1 μg/ml), which was similar to that of the baeS mutants isolated by single-step selection (NB27119-JBA0001 and NB27119-JBA0002) (Table 4).

The regulon of the BaeSR system contains genes for two efflux pumps, mdtABC and acrD (AcrD functions as part of AcrAD-TolC in E. coli) (25, 27). This suggests that upregulation of one or both pumps decreased susceptibility to LYS228 in these passaged mutants and, by extension, in the single-step baeS mutants. Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis of acrD and mdtA in strain NB27001-JBC0001 (passaged mutant) and NB27001-JWM0094 (engineered baeR mutant) showed increased expression of both genes relative to the parent strain NB27001 (Fig. S2), confirming that the specific BaeRL22Q alteration isolated here mediates pump upregulation. Upregulation of AcrD was of interest, since NB27001-JBC0001 (Table 6) also contained a structural mutation within the acrD gene. The encoded amino acid substitution (R629H) is located near residues important for recognition of β-lactams (27), suggesting this change increases pump recognition of LYS228. This could work together with increased AcrD expression, mediated by BaeRL22Q, to decrease susceptibility to LYS228. These results are reminiscent of a recent report where combinations of structural changes in the binding pockets of AcrB or AcrD and/or upregulated pump expression appeared to have decreased susceptibility to carbapenems in E. coli mutants generated via serial passaging (48). A combination of pump upregulation and structural mutations in efflux genes was also discussed for P. aeruginosa mutants emerging during serial passaging in ATM (45). The change in LYS228 susceptibility engendered by the acrD mutation alone was only 2-fold as measured by MIC, but there was also clearly improved growth in the presence of low levels of LYS228 relative to the parent strain (Fig. S3A), confirming its contribution to decreasing susceptibility. Furthermore, although a mutant harboring the combination of baeR and acrD mutations did not demonstrate a decrease in susceptibility by MIC compared to that of the baeR single mutant (NB27001-JRW0027 and NB27001-JWM0094) (Table 6), the double mutant did grow noticeably better at 0.5× MIC of LYS228 for strain NB27001-JWM0094, confirming a combined effect of these two mutations (Fig. S3B).

EnvZ is the kinase sensor component of the EnvZ-OmpR osmotic stress two-component regulatory pair controlling expression of the OmpC and OmpF major outer membrane porins in E. coli (49). EnvZL84Q (NB27001-JWM0096) may decrease susceptibility to LYS228 by altering expression of porins, reducing influx of LYS228. However, envZ mutations selected in E. coli by passaging in carbapenems appeared to decrease susceptibility via a porin-independent mechanism (48). RfaI is a lipopolysaccharide 1,3-galactosyltransferase involved in the synthesis of the core region of lipopolysaccharide. This suggests that RfaIY112C mediates alterations to the cell envelope that affect susceptibility to LYS228, but this remains to be explored. SucB is the dihydrolipoyllysine residue succinyltransferase component of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, which catalyzes the overall conversion of 2-oxoglutarate to succinyl-coenzyme A and CO2 (50). SucB thus plays a role in energy production, and sucB deletion mutants are defective in persister survival and have increased susceptibility to various antibiotics (50). SucBP27T did not appear to mediate a decrease in susceptibility as measured by MIC (NB27001-JRW0009) (Table 6) or growth curves (Fig. S3A), suggesting it does not play a role in reducing susceptibility. However, it is possible that it plays a role in combination with one or more of the other mutations emerging during passaging.

Interestingly, the activity of LYS228 in the LYS228- or ATM-selected passaging mutants NB27001-JBC0001 and NB27001-JBC0006 was improved 4-fold by the addition of the β-lactamase inhibitor AVI at 4 μg/ml (Table 6). There were also 2-fold and 4-fold improvements in activity of LYS228 in the engineered ftsI mutants NB27001-JWM0095 and NB27001-JWM0101 when tested in combination with AVI (Table 6). As described above, ATM is clearly more susceptible to AmpC activity than LYS228. AVI did not significantly increase susceptibility to ATM in either NB27001-JBC0001 or NB27001-JBC0006 (Table 6), implying that the increase in LYS228 susceptibility in the presence of AVI was not related to inhibition of AmpC. AVI is a member of the diazabicyclooctane family, which, in addition to possessing β-lactamase inhibitor activity, can also interact directly with penicillin binding proteins, in particular PBP2 (51). Inhibition of PBP2 can have a synergistic effect when combined with inhibition of PBP3, the target of LYS228 (52). This raises the possibility that the mutations in ftsI (encoding PBP3) of these passaged mutants somehow enables improved synergy between LYS228 and AVI, but this remains to be further investigated.

Concluding remarks.

LYS228 is a novel monobactam antibiotic designed to be stable to a broad range of SBLs while retaining the intrinsic stability of the monobactam scaffold to MBLs (13). Because of these properties, LYS228 demonstrated excellent potency across broad panels of MBL- and/or SBL-expressing Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates (13, 14). Here, we further characterized LYS228, showing that it inhibits growth of E. coli via inhibition of PBP3, similar to ATM. Single-step selection of mutants with decreased susceptibility to LYS228, using strains harboring various β-lactamase genes, occurred at a frequency comparable to that of clinically used antibiotics tested in the same experiments, and the shifts in susceptibility of the resulting mutants was modest. Upregulated expression of the β-lactamases present in these single-step test strains was not seen, consistent with the stability of LYS228 to most SBLs. Mutations associated with decreased susceptibility occurred mainly in regulators of the cell wall stress regulon and efflux. Twenty serial passages of E. coli in LYS228 engendered more substantial shifts in susceptibility, representing the cumulative effect of mutations in the target gene ftsI and in genes involved in cell wall stress regulons, among others.

For β-lactams in general, there has been a strong focus on the study of β-lactamase-mediated resistance. Our studies highlight various non-β-lactamase-based mechanisms, as might be expected, since LYS228 largely circumvents MBL- and SBL-mediated resistance. The lack of involvement of β-lactamases in reducing susceptibility in the mutants studied here reflects this stability; however, the number of strains used here was limited, therefore this study is not exhaustive. Expression of VEBs and PERs and other enzymes, such as OXA-181 and DHA-1, reduced susceptibility to LYS228 to various degrees in E. coli isogenic strain panels (13). Therefore, there may be cases where β-lactamases also contribute to reducing susceptibility, either through the selection of upregulated expression or changes in the bla structural gene that increase enzymatic hydrolysis of LYS228. Indeed, we also report involvement of plasmid-borne blaDHA-1 in reducing susceptibility to LYS228 in some K. pneumoniae clinical isolates, depending on expression level and/or the presence of other mechanisms decreasing susceptibility (53), as has been reported for other β-lactams. Should β-lactamases alone or together with the non-β-lactamase mechanisms identified in this study become a more important determinant of LYS228 insusceptibility in clinical isolates, this may be addressed by pairing LYS228 with an appropriate β-lactamase inhibitor. In conclusion, LYS228 is a new monobactam with increased stability to SBLs that retains the antibacterial mechanism of PBP3 inhibition and has an in vitro resistance selection profile comparable to those of clinically used antibiotics, which supports the continued development of LYS228 for the treatment of CRE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. Strains were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) (tryptone, 10 g/liter; yeast extract, 5 g/liter; NaCl, 10 g/liter), on LB plates solidified with 1.5% agar (LB agar), or in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB) or Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) plates (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). LYS228 was synthesized at Novartis. Avibactam (AVI), aztreonam (ATM), carbenicillin (CAR), ceftazidime (CAZ), cefsulodin (CFS), chloramphenicol (CHL), gentamicin (GEN) imipenem (IPM), kanamycin (KAN), levofloxacin (LVX), meropenem (MEM), gentamicin (GEN), and tigecycline (TGC) were obtained from commercial sources.

Expression and purification of EcPBP3.

An N-terminally poly-His-tagged truncated construct of E. coli PBP3 (EcPBP3), incorporating the tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease recognition sequence, was expressed and purified from E. coli using methods based on those of Sainsbury et al. (54). These are described in detail in the supplemental material.

Kinetic characterization of LYS228 in vitro binding to E. coli PBP3 using stopped-flow fluorimetry.

Stopped-flow fluorimetry has been successfully used to characterize kinetic parameters of β-lactam binding to PBPs (55), and we employed this approach to assess the kinetics of LYS228 binding to PBP3, as described in detail in the supplemental material.

Penicillin binding protein assay using crude bacterial membranes.

An E. coli NB27001 crude membrane fraction was prepared as described previously (56), with changes as described below. A 4-liter culture of NB27001 was grown to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.6 to 0.7) at 37°C in LB (1% NaCl), and cells were harvested by centrifugation (4,400 × g for 30 min at 4°C). The pellet was washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and suspended in 40 ml ice-cold PBS. The suspension was sonicated on ice (8 cycles of 40 s at 60% duty and output control at 4.5%, 2-min intervals between cycles) and centrifuged at 4,400 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was ultracentrifuged (150,000 × g) for 30 min at 4°C, and the pellet was washed by suspending in 10 ml ice-cold 1× PBS followed by a second ultracentrifugation. The pellet (total membrane fraction) was suspended in 4 ml of ice-cold PBS, and aliquots were stored at −80°C. Total protein content in the membrane fraction was measured using the Quick Start Bradford protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), using bovine serum albumin as the protein standard.

The PBP binding profiles of LYS228 and controls were determined by monitoring competition with BOCILLIN FL penicillin-PBP binding (BOCILLIN-PBP binding) using SDS-PAGE. For each compound, a 10-point, 4-fold dilution series was prepared (10% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] in PBS) at 10× the final assay concentration. The E. coli membrane fraction was prediluted to a final protein concentration of 1.33 mg/ml in PBS. Nine μl of diluted membrane fraction (12 μg) was combined with 1 μl of each 10× concentration solution of compound or 1 μl DMSO control (1% DMSO final concentration). Reaction mixtures were preincubated for 40 min at 37°C and then 1 μl of 200 μM BOCILLIN was added to each sample, followed by incubation at 37°C for 30 min. Samples were then denatured by adding 3 μl 4× NuPAGE LDS sample buffer and incubating for 10 min at 70°C. Ten-μl aliquots of each sample were separated by SDS-PAGE using 4 to 12% Tris-glycine gels (1.0 mm, 12 well) at a constant power of 20 mA for 2 h. BenchMark fluorescent protein standards (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were used as the molecular weight markers (MWMs). Bands were visualized with a Typhoon 9400 variable-mode imager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Densitometry analysis was conducted using ImageQuant v5.2 image analysis software (Molecular Dynamics). For each PBP band analyzed, the volume per area was calculated (i.e., volume divided by area, or V/A). An average background V/A value was also determined per sample lane and was subtracted from each sample band within the corresponding lane. The percent BOCILLIN-PBP binding value for each PBP at each compound concentration was then calculated, using the DMSO control band (per corresponding PBP) from the matching gel as the 100% control: % BOCILLIN-PBP binding = [((Vcompound PBPx/Acompound PBPx) − (Vbkgd/Abkgd))/((Vcontrol PBPx/Acontrol PBPx) − (Vbkgd/Abkgd))] × 100, where Vcompound PBPx is the volume of the compound treatment band for PBPx, Acompound PBPx is area of the compound treatment band for PBPx, Vbkgd is volume of the background band for the corresponding sample lane, Abkgd is area of the background band for the corresponding sample lane, Vcontrol PBPx is volume of the control treatment (DMSO) band for PBPx, and Acontrol PBPx is area of the control treatment (DMSO) band for PBPx.

Percent BOCILLIN-PBP binding values are indicative of the amount of BOCILLIN labeling in the presence of the compound, with decreasing values being indicative of higher levels of compound-PBP binding.

E. coli cell preparation and fluorescence microscopy.

E. coli strain NB27001 (Table 3) was used for this study. Cells were grown at 37°C overnight in Mueller-Hinton broth II, and 1% of the overnight culture was inoculated into 10 ml CAMHB to grow cells to late log phase (OD600 of 0.5). The culture was diluted 20-fold in CAMHB and grown for 2 h at 37°C in the absence or presence of 0.5 μg/ml of ATM (MIC, 0.125 μg/ml), 0.5 μg/ml of LYS228 (MIC, 0.25 μg/ml), or 0.015 μg/ml of ciprofloxacin (MIC, 0.008 μg/ml). The cells were stained with 5 μg/ml FM1-43fx and 5 μg/ml DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) and observed on a 1.2% agarose pad with fluorescence microscopy. All phase-contrast and fluorescence micrographs were captured by using a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope with a Nikon halogen illuminator (D-LH/LC), a Sola light engine from Lumencor (Beaverton, OR), and a Clara Interline charge-coupled device camera from Andor (South Windsor, CT). A Nikon CFI Plan Apo Lambda DM 100× oil objective lens (1.45 numeric aperture) was used for phase-contrast and fluorescent imaging. For FM 1-43fx images we used the FITC-5050ANTE-ZERO filter set from Semrock (Rochester, NY). The DAPI images were taken by using the BFP-A-Basic-NTE filter set (Semrock). The exposure time for DAPI images and green fluorescent protein (GFP) images were 500 ms and 100 ms, respectively. Images were captured by using Nikon Elements software and exported for figure preparation in ImageJ (57).

Selection of single-step spontaneous mutants.

A total of 12 isolates, comprised of E. coli (n = 5), K. pneumoniae (n = 6), and E. cloaecae (n = 1) from the Novartis collection, including isolates that produce β-lactamase enzymes (i.e., KPCs, CTX-M, and NDM-1), were used for selection experiments. For each bacterial strain, a concentrated cell suspension (target of ≥1010 CFU per ml) was prepared by growing cells overnight on three MHA plates and harvesting the cells from the entire surface of the plates using sterile cotton swabs. Cells were suspended in 3 ml of CAMHB–17% sterile glycerol and frozen at −80°C. The CFU per milliliter were then determined. Single-step selection was performed on plates containing test compounds at 4× and 8× multiples of the MIC mode for each compound in duplicate. Dilutions of cell suspension were also plated on drug-free medium to enumerate CFU per milliliter. Plates were incubated overnight at 35°C for 24 h and CFU were counted. Mutant frequencies were calculated by dividing the number of colonies on drug-containing plates by the number of CFU plated.

Multistep selection for reduced susceptibility to antibiotics (serial passaging).

Multistep in vitro resistance selection was performed using the broth macrodilution method (58). Serial passages were performed daily in 2 ml CAMHB. E. coli NB27001 was exposed to a series of 2-fold dilutions of LYS228, ATM, MEM, or TGC. A control tube in which E. coli ATCC 25922 was grown without antibiotic treatment was also prepared. For each subsequent daily passage, a new inoculum of 5 × 105 CFU/ml was prepared from the tube with a concentration of one to two dilutions below the MIC that matched the turbidity of a growth control tube and was used to inoculate the dilution series for the next passage. Twenty consecutive daily passages were performed, after which bacterial susceptibility to various antibiotics was measured. A significant increase in MIC was defined as greater than 4-fold. The stability of the >4-fold shift in MIC was evaluated after five daily passages in antibiotic-free CAMHB. A stable clone was defined as one that had the same elevated MIC after five daily drug-free passages (±1 doubling dilution). Five colonies isolated by plating culture from the final passage tube for both LYS228 and ATM were isolated for whole-genome sequencing.

Whole-genome sequencing.

Genomic DNA was prepared from bacterial cells using the Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, except that samples were eluted in and then diluted to 8 ng/μl with nuclease-free water. Genomic libraries were prepared using standard protocols, and sequencing runs were conducted using Illumina MiSeq or HiSeq sequencers (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Genetic variants were called from whole-genome sequencing data using a collection of software tools and custom scripts, as described in detail in the supplemental material.

RT-qPCR.

Oligonucleotide primers and probes used for gene expression studies (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT; San Diego, CA) and were designed using their PrimerQuest design tool. The probes were labeled with the fluorophore 6-carboxyfluorescein (6′-FAM) at the 5′ end and with the quencher dye 6-carboxytetramethylrodamine (TAMRA) at the 3′ end. RNA isolation and RT-qPCR were performed as described previously (23), with the following modifications: RT-qPCR was performed using a qScript XLT one-step RT-qPCR ToughMix kit (Quanta Biosciences, Beverly, MA) on a Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time detection system. The 25-μl RT-qPCRs sample consisted of 5 μl of a serial dilution of RNA template (range, 2 ng/μl to 200 μg/μl) and 20 μl of an RT mix containing RT-qPCR ToughMix, primers (450 nM), and probe (150 nM) as recommended by the manufacturer. The quantification cycle (Cq) values were determined using the Bio-Rad CFX Manager software (version 3.1). Target gene expression was quantified by normalizing to rrsE as previously described (23).

Introduction of mutations onto the chromosome of K. pneumoniae using CRISPR.

Oligonucleotide primers used for mutant constructions are listed in Table S2. K. pneumoniae expressing the CpxA L57V variant was constructed as follows. To assemble the CpxA L57V encoding construct, the upstream region from K. pneumoniae strain NB29001 was PCR amplified using primers KTT1277 and KTT1278, which attaches a linker encoding the L57V mutation and incorporates a silent mutation for the purpose of CRISPR engineering. The downstream region was amplified using primers KTT1279 and KTT1280, and a final construct was generated by stitching the upstream and downstream fragments using overlap extension PCR (59). The resulting linear fragment was cotransformed with plasmid pNOV145, which carries the guide RNA (gRNA), into the K. pneumoniae strain ATCC 43816, harboring pNOV141, which encodes the Cas9 nuclease protein, by electroporation. Following electroporation, the cells were plated on LB agar with carbenicillin (500 μg/ml for pNOV141), gentamicin (10 μg/ml for gRNA vector), and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; 0.5 mM for induction of Cas9 expression).

K. pneumoniae expressing the VK055_RS01255 I58T variant was constructed as follows. For the assembly of the VK055_RS01255 construct, the upstream region of VK055_RS01255 was PCR amplified using primers KTT1285 and KTT1286, which attaches a linker encoding the I58T mutation and incorporates a silent mutation for the purpose of CRISPR engineering. The downstream region of VK055_RS01255 was amplified using primers KTT1287 and KTT1288, and the final substrate was generated by stitching the upstream and downstream fragments using overlap extension PCR (59). This linear fragment was used to introduce the mutation onto the chromosome as described above. The correct mutation was verified by PCR with the primer pair cPCR G8VVY6 F and cPCR G8VVY6 R and sequencing. Mutants harboring only the silent mutation used for CRISPR were also created as a control. The correct clones were then streaked on 0.8% sucrose plates (no salt) to cure the plasmids. Isolated colonies were then patched on LB plates or LB plates with carbenicillin (30 μg/ml) or gentamicin (10 μg/ml) to confirm loss of plasmids. Clones cured of the plasmids then were sequencing verified again for the correct chromosomal mutation.

Introduction of mutations onto the chromosome of E. coli using CRISPR.

A series of vectors were made that contained specific gRNAs for introduction of point mutations into the genome of E. coli NB27001 via CRISPR. These plasmids, pMM2 (for ftsI), pJW20 (for rfaI), pMM21 (for acrD), pMM22 (for baeR), pMM23 (for envZ), and pJW24 (for sucB) (Table 3), were cotransformed with the corresponding oligonucleotides (Table S2) into E. coli NB27001 harboring pNOV141. Following electroporation, the cells were plated on LB agar with carbenicillin (30 μg/ml for pNOV141), gentamicin (10 μg/ml for gRNA vector), and IPTG (0.5 mM; for induction of Cas9 expression). Introduced mutations were confirmed by colony PCR using corresponding primers (Table S2). Confirmed mutants were then streaked on 0.8% sucrose plates (no salt) to cure the plasmids. The isolated colonies were then patched on LB plates or LB plates with carbenicillin (30 μg/ml) or gentamicin (10 μg/ml) to confirm loss of plasmids. Clones cured of the plasmids again were sequencing verified for the correct chromosomal mutation.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Susceptibility testing was performed using a broth microdilution assay by following the recommended methodology of the CLSI (58). The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of antibiotic at which the visible growth of the organism is completely inhibited. Compounds were tested several times against each strain, and the MIC mode was calculated. The 4× and 8× multiples of the MIC mode value obtained for each antimicrobial agent/strain combination were used for the selection of single-step spontaneous mutants.

Accession number(s).

Sequences for the plasmids reported in this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. MH697720 to MH697728.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Catherine Jones and Jennifer Leeds for editorial assistance and JMI Laboratories for strains.

Footnotes

For a companion article on this topic, see https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01202-18.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01200-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Watkins RR, Bonomo RA. 2016. Overview: global and local impact of antibiotic resistance. Infect Dis Clin North Am 30:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.East SP, Silver LL. 2013. Multitarget ligands in antibacterial research: progress and opportunities. Expert Opin Drug Discov 8:143–156. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2013.743991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Dwyer K, Spivak AT, Ingraham K, Min S, Holmes DJ, Jakielaszek C, Rittenhouse S, Kwan AL, Livi GP, Sathe G, Thomas E, Van Horn S, Miller LA, Twynholm M, Tomayko J, Dalessandro M, Caltabiano M, Scangarella-Oman NE, Brown JR. 2015. Bacterial resistance to leucyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitor GSK2251052 develops during treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:289–298. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03774-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Livermore DM, British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy Working Party on The Urgent Need: Regenerating Antibacterial Drug Discovery and Development. 2011. Discovery research: the scientific challenge of finding new antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother 66:1941–1944. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czaplewski L, Bax R, Clokie M, Dawson M, Fairhead H, Fischetti VA, Foster S, Gilmore BF, Hancock RE, Harper D, Henderson IR, Hilpert K, Jones BV, Kadioglu A, Knowles D, Olafsdottir S, Payne D, Projan S, Shaunak S, Silverman J, Thomas CM, Trust TJ, Warn P, Rex JH. 2016. Alternatives to antibiotics-a pipeline portfolio review. Lancet Infect Dis 16:239–251. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00466-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush K. 2013. Proliferation and significance of clinically relevant beta-lactamases. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1277:84–90. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Queenan AM, Bush K. 2007. Carbapenemases: the versatile beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:440–458. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drawz SM, Papp-Wallace KM, Bonomo RA. 2014. New beta-lactamase inhibitors: a therapeutic renaissance in an MDR world. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:1835–1846. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00826-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh TR, Weeks J, Livermore DM, Toleman MA. 2011. Dissemination of NDM-1 positive bacteria in the New Delhi environment and its implications for human health: an environmental point prevalence study. Lancet Infect Dis 11:355–362. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felici A, Amicosante G. 1995. Kinetic analysis of extension of substrate specificity with Xanthomonas maltophilia, Aeromonas hydrophila, and Bacillus cereus metallo-beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39:192–199. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.1.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felici A, Amicosante G, Oratore A, Strom R, Ledent P, Joris B, Fanuel L, Frere JM. 1993. An overview of the kinetic parameters of class B beta-lactamases. Biochem J 291(Part 1):151–155. doi: 10.1042/bj2910151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlowsky JA, Kazmierczak KM, de Jonge BLM, Hackel MA, Sahm DF, Bradford PA. 2017. In vitro activity of aztreonam-avibactam against Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated by clinical laboratories in 40 countries from 2012 to 2015. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00472-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00472-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reck F, Bermingham A, Blais J, Capka V, Cariaga T, Casarez A, Colvin R, Dean CR, Fekete A, Gong W, Growcott E, Guo H, Jones AK, Li C, Li F, Lin X, Lindvall M, Lopez S, McKenney D, Metzger L, Moser HE, Prathapam R, Rasper D, Rudewicz P, Sethuraman V, Shen X, Shaul J, Simmons RL, Tashiro K, Tang D, Tjandra M, Turner N, Uehara T, Vitt C, Whitebread S, Yifru A, Zang X, Zhu Q. 2018. Optimization of novel monobactams with activity against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae–identification of LYS228. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 28:748–755. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blais J, Lopez S, Li C, Ruzin A, Ranjitkar S, Dean CR, Leeds JA, Casarez A, Simmons RL, Reck F. 23 July 2018. In vitro activity of LYS228, a novel monobactam antibiotic, against multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother doi: 10.1128/AAC.00552-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgopapadakou NH, Smith SA, Sykes RB. 1982. Mode of action of azthreonam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 21:950–956. doi: 10.1128/AAC.21.6.950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nonejuie P, Burkart M, Pogliano K, Pogliano J. 2013. Bacterial cytological profiling rapidly identifies the cellular pathways targeted by antibacterial molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:16169–16174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311066110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pogliano J, Pogliano K, Weiss DS, Losick R, Beckwith J. 1997. Inactivation of FtsI inhibits constriction of the FtsZ cytokinetic ring and delays the assembly of FtsZ rings at potential division sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:559–564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huisman O, D'Ari R, Gottesman S. 1984. Cell-division control in Escherichia coli: specific induction of the SOS function SfiA protein is sufficient to block septation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81:4490–4494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curtis NA, Orr D, Ross GW, Boulton MG. 1979. Affinities of penicillins and cephalosporins for the penicillin-binding proteins of Escherichia coli K-12 and their antibacterial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 16:533–539. doi: 10.1128/AAC.16.5.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keeney D, Ruzin A, Bradford PA. 2007. RamA, a transcriptional regulator, and AcrAB, an RND-type efflux pump, are associated with decreased susceptibility to tigecycline in Enterobacter cloacae. Microb Drug Resist 13:1–6. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2006.9990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keeney D, Ruzin A, McAleese F, Murphy E, Bradford PA. 2008. MarA-mediated overexpression of the AcrAB efflux pump results in decreased susceptibility to tigecycline in Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother 61:46–53. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruzin A, Immermann FW, Bradford PA. 2008. Real-time PCR and statistical analyses of acrAB and ramA expression in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:3430–3432. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00591-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruzin A, Keeney D, Bradford PA. 2005. AcrAB efflux pump plays a role in decreased susceptibility to tigecycline in Morganella morganii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:791–793. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.2.791-793.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baranova N, Nikaido H. 2002. The BaeSR two-component regulatory system activates transcription of the yegMNOB (mdtABCD) transporter gene cluster in Escherichia coli and increases its resistance to novobiocin and deoxycholate. J Bacteriol 184:4168–4176. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.15.4168-4176.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leblanc SK, Oates CW, Raivio TL. 2011. Characterization of the induction and cellular role of the BaeSR two-component envelope stress response of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 193:3367–3375. doi: 10.1128/JB.01534-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirakawa H, Nishino K, Yamada J, Hirata T, Yamaguchi A. 2003. Beta-lactam resistance modulated by the overexpression of response regulators of two-component signal transduction systems in Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother 52:576–582. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi N, Tamura N, van Veen HW, Yamaguchi A, Murakami S. 2014. Beta-lactam selectivity of multidrug transporters AcrB and AcrD resides in the proximal binding pocket. J Biol Chem 289:10680–10690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.547794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Majumdar S, Yu J, Spencer J, Tikhonova IG, Schneiders T. 2014. Molecular basis of non-mutational derepression of ramA in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:2681–2689. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bratu S, Landman D, George A, Salvani J, Quale J. 2009. Correlation of the expression of acrB and the regulatory genes marA, soxS and ramA with antimicrobial resistance in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae endemic to New York City. J Antimicrob Chemother 64:278–283. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hentschke M, Wolters M, Sobottka I, Rohde H, Aepfelbacher M. 2010. ramR mutations in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae with reduced susceptibility to tigecycline. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:2720–2723. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00085-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenblum R, Khan E, Gonzalez G, Hasan R, Schneiders T. 2011. Genetic regulation of the ramA locus and its expression in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int J Antimicrob Agents 38:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jimenez-Castellanos JC, Wan Ahmad Kamil WN, Cheung CH, Tobin MS, Brown J, Isaac SG, Heesom KJ, Schneiders T, Avison MB. 2016. Comparative effects of overproducing the AraC-type transcriptional regulators MarA, SoxS, RarA and RamA on antimicrobial drug susceptibility in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:1820–1825. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jimenez-Castellanos JC, Wan Nur Ismah WAK, Takebayashi Y, Findlay J, Schneiders T, Heesom KJ, Avison MB. 2018. Envelope proteome changes driven by RamA overproduction in Klebsiella pneumoniae that enhance acquired beta-lactam resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 73:88–94. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishino K, Nikaido E, Yamaguchi A. 2007. Regulation of multidrug efflux systems involved in multidrug and metal resistance of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 189:9066–9075. doi: 10.1128/JB.01045-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin MF, Lin YY, Yeh HW, Lan CY. 2014. Role of the BaeSR two-component system in the regulation of Acinetobacter baumannii adeAB genes and its correlation with tigecycline susceptibility. BMC Microbiol 14:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Broberg CA, Wu W, Cavalcoli JD, Miller VL, Bachman MA. 2014. Complete genome sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae strain ATCC 43816 KPPR1, a rifampin-resistant mutant commonly used in animal, genetic, and molecular biology studies. Genome Announc 2:e00924-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00924-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]