Abstract

Objectives

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a systemic autoimmune disorder. Several molecular pathways and the activation of matrix metalloproteinases associated with the pathogenesis of SS participate in the initiation and progression of aortic aneurysm (AA) and aortic dissection (AD). In this study, we aimed to evaluate whether patients with SS exhibit an increased risk of AA or AD.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using a database extracted from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database. All medical conditions for each case and control were categorised using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision. HRs and 95% CIs for associations between SS and AA/AD were estimated using Cox regression and adjusted for comorbidities.

Results

Our analyses included 10 941 SS cases and 43 764 propensity score-matched controls. Compared with the controls, the patients with SS exhibited a significantly increased risk of developing an AA or AD (adjusted HR=3.642, p<0.001). Subgroup analysis revealed that compared with patients without SS, patients with primary and secondary SS both exhibited a significantly increased risk of developing AA or AD (adjusted HR=1.753, p=0.042; adjusted HR=3.693, p<0.001).

Conclusion

Patients with SS exhibit increased risks of developing AA or AD, and healthcare professionals should be aware of this risk when treating patients with SS. Increased aortic surveillance may be required for patients with SS.

Keywords: Sjögren’s syndrome, aortic dissection, aortic aneurysm

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strength of our study is its population-based cohort design with a large sample size.

The patients and controls were selected by 1:4 matching according to the following baseline variables: age, sex, comorbidities and medications used. This population-based cohort study was adjusted for potential risk factors to minimise study bias.

This was a retrospective cohort study.

National Health Insurance Research Database cannot provide detailed information regarding the laboratory results or lifestyle factors of the patients.

Our results are limited to human data. Both mechanistic and animal studies are required for further clarification.

Introduction

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a systemic autoimmune disorder commonly presenting with dry eyes and mouth. The prevalence of SS is between 0.1% and 4.8% in various populations when strictly defined according to the American-European Consensus Criteria, and it is one of the most common autoimmune diseases.1 SS may affect patients at any age, but more cases occur in the fourth decade of life, and there is a female predominance. The female-to-male ratio is approximately 9:1.2 Aortic aneurysms (AAs) are often diagnosed inadvertently and are a common cause of sudden death. Enlarged aneurysms can result in rupture. Aortic dissection (AD) is one of the deadliest complications of thoracic aortic disease. Estimates of the incidence of AD range from 6 cases per 100 000 to 16.3 per 100 000 in England and Sweden, respectively.3 4 Regarding the Asian population, the average annual incidence of AD is 5.6 per 100 000 persons in Taiwan and the prevalence is 19.9 per 100 000 persons, with a predominance noted among men 50–54 years of age (27.3 per 100 000 persons per year).5

Previous studies have demonstrated that AA is more prevalent in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) compared with the general population.6 7 Compared with age-matched and sex-matched healthy controls, patients with primary SS (PSS) exhibited a twofold increased prevalence of hypertension and hypertriglyceridaemia. Furthermore, hypertension is underdiagnosed and suboptimally treated in PSS.8 SS with positive autoantibodies is associated with a low ankle–brachial index which may indicate an increased risk of early atherosclerosis.9 Nonetheless, previous population-based studies indicated that SS is not associated with an increased risk of subsequent acute myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke.10 11

Several molecular mechanisms, including JNK, NF-κB and TGF-β signalling pathways, and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activation are associated with the pathogenesis of SS.12 13 These molecular mechanisms also actively participate in the initiation and progression of AA or AD.14 15 Based on these findings, we hypothesise that patients with SS may have an increased risk of AA or AD due to SS-related cardiovascular risks and shared molecular mechanisms. However, the association between SS and AA or AD has not been thoroughly evaluated in large-scale studies. Therefore, we aimed to determine whether patients with SS exhibited an increased risk of AA or AD using a nationwide healthcare insurance claim database.

Methods

Data source

The data described herein were acquired from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2005 (LHID 2005), a subgroup database of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) used for the nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. The National Health Insurance programme in Taiwan provides healthcare for 99% of the population (greater than 23 million people) and was implemented in 1995. The LHID 2005 provides information on medical service utilisation using a randomly selected sample of approximately one million people receiving benefits, representing approximately 5% of Taiwan’s population in 2005. The information was obtained from the NHIRD between 2000 and 2010. The accuracy of the diagnoses in the NHIRD, particularly the diagnoses of major diseases (eg, acute coronary syndrome and stroke), has been corroborated.16 17 The LHID is composed of ‘de-identified’ secondary data that are available to the public via open access for research. International Classification of Diseases, ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic and procedure codes (up to five each), sex, birthdays, patient identification numbers, dates of admission and discharge, and outcomes are coded. In addition, information regarding the medical institutions that served patients was obtained. Individual information was protected using encoded personal identification to prevent ethical violations related to the data. Our study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant guidelines.

Patient and public involvement

This is a database study using NHIRD. No patients or public were involved in setting out the research question or developing the outcome measures. No patients or public were involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No patients or public were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. No patients or public were the burden of the interventions on patients assessed. The results of the research were not disseminated to those study patients.

Sampled patients

We used study and comparison cohorts. Using the LHID 2005, we selected adult patients aged >20 years who were newly diagnosed with SS (recorded from both the LHID 2005 and the Registry of Catastrophic Illness Patient Database) after 2000 and who were followed up between 2000 and 2010. We excluded patients who were diagnosed with SS before 2000 and had AA or AD, Turner syndrome, aortic coarctation, bicuspid aortic valve, Marfan syndrome or Ehler-Danlos syndrome. Patients who had a tracking time <6 months were also excluded in order to decrease the probability of including AA/AD cases that went undiagnosed before SS diagnosis. The date of SS diagnosis was used as the index date. Control candidate sampling comparisons were selected from individuals in the LHID 2005 who lacked a history of SS. The patient and control cohorts were selected by 1:4 matching according to the following baseline variables: age; sex; comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), hyperlipidaemia, Behcet’s disease, giant cell arteritis, RA and other inflammatory polyarthropathies, relapsing polychondritis, Takayasu’s arteritis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); and medication history, including β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, diuretics and steroid history. We used COPD as a proxy variable for tobacco use to eliminate its potential confounding effect as previously described.18 The SS patient and control cohorts were matched 1:4 based on their propensity score matching, for which the matching tolerance was 0.15 with the nearest neighbour method. The independent variables were demographics, comorbidities, medications and SS. The dependent variables were AA and AD. We also divided patients with SS into PSS and secondary SS (SSS) patients and performed a subgroup analysis. SS previously diagnosed as SLE, RA, systemic sclerosis or primary biliary cirrhosis were defined as SSS. We integrated the ICD-9-CM codes of the above diseases into a table in the supplementary materials (online supplementary table 1). The index dates for control patients were the same as the corresponding dates for patients with AA/AD. The study outcome was a diagnosis of AA/AD during the 10-year follow-up period. AA/AD was identified using ICD-9 codes. The end point of the follow-up period was 31 December 2010 or the time at which AA/AD events occurred or the patient died or was lost to follow-up. We integrated the median follow-up time and follow-up year with AA/AD events in the supplementary materials (online supplementary table 2 and 3).

bmjopen-2018-022326supp001.pdf (213.6KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

Propensity-matching analysis was performed in the logistic regression model. The potential confounders were index year, gender, age, comorbidities and medications. The match tolerance was 0.15 with the nearest neighbour method. The study comparison cohort-matching ratio was fourfold (study: comparison=1:4). Categorical variables, presented as percentages, were compared using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. Continuous variables, presented as the means and SDs, were compared using a t-test. The primary goal of the study was to determine whether patients with SS exhibited an increased risk of developing AA/AD. The associations between those outcomes (prognoses) and clinical characteristics were investigated using Cox regression. As shown in online supplementary table 4, all explanatory variables in the fully adjusted model were retained. The results were presented as adjusted HRs with corresponding 95% CIs. Kaplan-Meier curves with the log-rank test were used to compare patients with and without SS in terms of the cumulative risk of AA or AD. The threshold for statistical significance was p<0.05. All data analyses were conducted using SPSS V.22.

Results

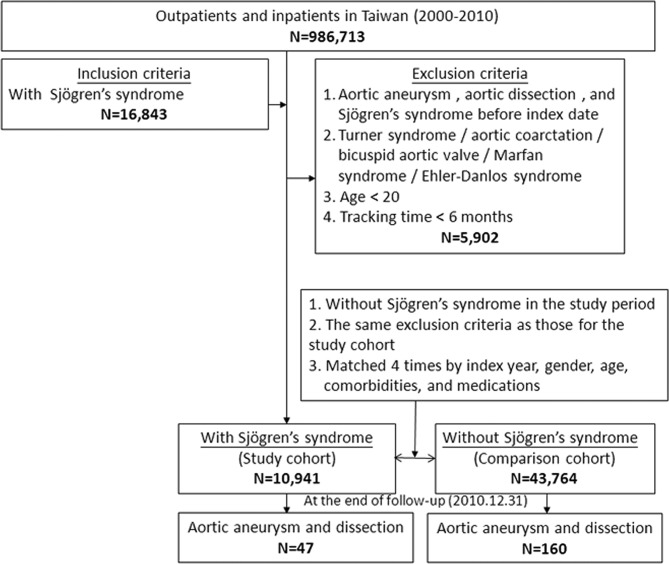

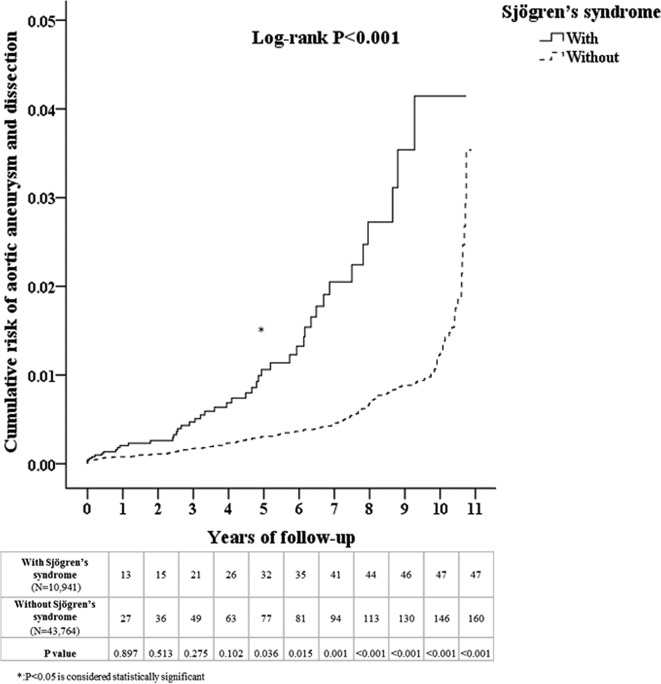

A flow diagram of our patient enrolment scheme is presented in figure 1. A total of 10 941 patients diagnosed with SS were identified in the NHIRD which contained a total of 986 713 individuals. An additional 43 764 age, sex, comorbidity and medication-matched patients were designated controls. As shown in table 1, no significant differences in sex, age, comorbidities, including DM, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, Behcet’s disease, giant cell arteritis, RA, relapsing polychondritis, Takayasu’s arteritis and COPD, or medications were noted between the two groups after matching. Patients with SS exhibited a significantly increased cumulative risk of developing AA/AD in subsequent years compared with patients without SS (log-rank test <0.001, figure 2). Table 2 presents the incidences of AA or AD during the 10-year follow-up period. At the end of the follow-up period, patients with SS exhibited significantly increased incidences of AA or AD (0.43% vs 0.37%, p=0.045) but lower incidences of DM (7.73% vs 15.44%, p<0.001) and COPD (5.96% vs 6.72%, p=0.004). In addition, patients with SS were younger and exhibited higher Charlson Comorbidity Index than patients without SS. The incidence for AA or AD was higher in males and older patients regardless of whether patients had SS or not (online supplementary figure 1 and 2). Regarding the use of Cox regression independent of the effects of sex, age, comorbidities and medication, compared with patients without SS, patients with SS also exhibited a significantly increased risk of developing AA or AD (adjusted HR=3.642, 95% CI 2.527 to 5.250, p<0.001, table 3). The subgroup analysis revealed that patients with PSS or SSS both exhibited significantly increased risks for developing AA/AD compared with patients without SS (adjusted HR=1.753, 95% CI 1.108 to 9.382, p=0.042; adjusted HR=3.693, 95% CI 2.520 to 5.411, p<0.001, table 4). We also have included the first event of AA/AD coding into the distribution analysis in the supplementary material (online supplementary table 5). All patients were coded with AA/AD for the first time in the inpatient and emergency room (ER) sections.

Figure 1.

Patient selection flow chart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants at baseline

| Sjögren’s syndrome | Total | With | Without | P values |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Total | 54 705 | 10 941 (20.00) | 43 764 (80.00) | |

| Sex | 0.999 | |||

| Male | 10 187 (18.63) | 2011 (18.44) | 8176 (18.68) | |

| Female | 44 485 (81.37) | 8897 (81.56) | 35 588 (81.32) | |

| Age (years) | 55.78±17.09 | 55.80±16.65 | 55.77±17.20 | 0.897 |

| DM | 3553 (6.49) | 724 (6.62) | 2829 (6.46) | 0.558 |

| Hypertension | 8091 (14.79) | 1578 (14.42) | 6513 (14.88) | 0.228 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 1145 (2.09) | 234 (2.14) | 911 (2.08) | 0.709 |

| Behcet’s disease | 321 (0.59) | 62 (0.57) | 259 (0.59) | 0.834 |

| Giant cell arteritis | 15 (0.03) | 3 (0.03) | 12 (0.03) | 0.999 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 8907 (16.28) | 1784 (16.31) | 7123 (16.28) | 0.942 |

| Relapsing polychondritis | 71 (0.13) | 14 (0.13) | 57 (0.13) | 0.953 |

| Takayasu’s arteritis | 15 (0.03) | 3 (0.03) | 12 (0.03) | 0.999 |

| COPD | 2931 (5.36) | 581 (5.3) | 2350 (5.37) | 0.831 |

| Steroid | 16 799 (30.71) | 3345 (30.57) | 13 454 (30.74) | 0.737 |

| β Blocker | 12 588 (23.01) | 2513 (22.97) | 10 075 (23.02) | 0.919 |

| CCB | 11 553 (21.12) | 2342 (21.41) | 9211 (21.05) | 0.409 |

| ACEI | 13 586 (24.84) | 2711 (24.78) | 10 875 (24.85) | 0.878 |

| ARB | 12 718 (23.25) | 2620 (23.95) | 10 098 (23.07) | 0.054 |

| Diuretic | 12 440 (22.74) | 2429 (22.20) | 10 011 (22.87) | 0.136 |

| Statin | 13 922 (25.45) | 2811 (25.69) | 11 111 (25.39) | 0.516 |

P value (categorical variable: χ2/Fisher’s exact test; continuous variable: t-test).

ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of the cumulative risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection due to Sjögren’s syndrome.

Table 2.

Incidences of aortic aneurysm and dissection and other characteristics during the 10-year follow-up period

| Sjögren ’s syndrome | Total | With | Without | P values |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Total | 54 705 | 10 941 (20.00) | 43 764 (80.00) | |

| Aortic aneurysm and dissection | 207 (0.38) | 47 (0.43) | 160 (0.37) | 0.045 |

| Sex | 0.999 | |||

| Male | 10 187 (18.63) | 2011 (18.44) | 8176 (18.68) | |

| Female | 44 485 (81.37) | 8897 (81.56) | 35 588 (81.32) | |

| Age (years) | 61.36±5.41 | 60.90±4.98 | 61.47±5.51 | <0.001 |

| DM | 7603 (13.90) | 846 (7.73) | 6757 (15.44) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 8821 (16.12) | 1708 (15.61) | 7113 (16.25) | 0.102 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 1128 (2.06) | 240 (2.19) | 888 (2.03) | 0.279 |

| Behcet’s disease | 324 (0.59) | 63 (0.58) | 261 (0.60) | 0.802 |

| Giant cell arteritis | 16 (0.03) | 3 (0.03) | 13 (0.03) | 0.901 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 9033 (16.51) | 1774 (16.21) | 7259 (16.59) | 0.348 |

| Relapsing polychondritis | 80 (0.15) | 19 (0.17) | 61 (0.14) | 0.401 |

| Takayasu’s arteritis | 15 (0.03%) | 3 (0.03) | 12 (0.03) | 0.999 |

| COPD | 3593 (6.57) | 652 (5.96) | 2941 (6.72) | 0.004 |

| CCI_R | 0.78±1.53 | 0.83±1.39 | 0.77±1.56 | <0.001 |

| Steroid | 17 112 (31.28) | 3511 (32.09) | 13 601 (31.08) | 0.041 |

| β Blockers | 13 750 (25.13) | 2674 (24.44) | 11 076 (25.31) | 0.061 |

| CCB | 11 833 (21.63) | 2397 (21.91) | 9436 (21.56) | 0.430 |

| ACEI | 13 793 (25.21) | 2784 (25.45) | 11 009 (25.16) | 0.532 |

| ARB | 12 976 (23.72) | 2681 (24.50) | 10 295 (23.52) | 0.031 |

| Diuretic | 12 692 (23.20) | 2507 (22.91) | 10 185 (23.27) | 0.427 |

| Statin | 14 123 (25.82) | 2828 (25.85) | 11 295 (25.81) | 0.934 |

P value (categorical variable: χ2/Fisher’s exact test; continuous variable: t-test).

ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CCI_R, Charlson Comorbidity Index removed; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus.

Table 3.

Factors associated with aortic aneurysm and dissection according to Cox regression

| Variables | Crude HR | 95% CI | P values | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P values |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | 3.205 | 2.254 to 3.565 | <0.001 | 3.642 | 2.527 to 5.250 | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 2.645 | 1.974 to 3.597 | <0.001 | 2.035 | 1.534 to 2.700 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 1.049 | 1.032 to 1.057 | <0.001 | 1.043 | 1.032 to 1.055 | <0.001 |

| DM | 1.704 | 1.389 to 1.944 | 0.024 | 1.674 | 1.065 to 1.976 | 0.037 |

| Hypertension | 1.165 | 1.022 to 1.454 | 0.038 | 1.305 | 0.973 to 1.751 | 0.075 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 1.211 | 0.594 to 2.436 | 0.618 | 1.343 | 0.656 to 2.751 | 0.420 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1.645 | 0.774 to 3.496 | 0.196 | 0.801 | 0.362 to 1.769 | 0.583 |

| COPD | 1.838 | 1.256 to 2.691 | 0.002 | 1.170 | 0.790 to 1.735 | 0.433 |

| CCI_R | 1.036 | 0.945 to 1.087 | 0.074 | 1.016 | 0.968 to 1.065 | 0.527 |

| Steroid | 1.497 | 0.598 to 2.976 | 0.495 | 1.501 | 0.339 to 3.298 | 0.617 |

| β Blockers | 1.468 | 0.453 to 2.772 | 0.862 | 1.398 | 0.401 to 2.895 | 0.803 |

| CCB | 1.345 | 0.343 to 2.901 | 0.372 | 1.402 | 0.452 to 2.806 | 0.280 |

| ACEI | 1.298 | 0.426 to 3.041 | 0.601 | 1.288 | 0.395 to 2.845 | 0.334 |

| ARB | 1.346 | 0.379 to 1.986 | 0.711 | 1.345 | 0.343 to 1.886 | 0.682 |

| Diuretic | 1.198 | 0.598 to 2.511 | 0.652 | 1.201 | 0.490 to 2.907 | 0.703 |

| Statin | 1.364 | 0.667 to 4.972 | 0.798 | 1.335 | 0.679 to 4.787 | 0.897 |

Adjusted HR: adjusted variables listed in the table.

ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CCI_R, Charlson Comorbidity Index removed; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus.

Table 4.

Factors associated with aortic aneurysm and dissection stratified by primary/secondary Sjögren’s syndrome using Cox regression

| Patients with Sjögren’s syndrome | Patients without Sjögren’s syndrome | Ratio | Adjusted HR* | 95% CI | P values | |||||

| Events | PY | Incidence rate (per 105 PY) |

Events | PY | Incidence rate (per 105 PY) |

|||||

| Total | 47 | 55 860.08 | 84.14 | 160 | 253 779.88 | 63.05 | 1.335 | 3.642 | 2.527 to 5.250 | <0.001 |

| Without RA/SLE/ SS/PBC |

30 | 36 607.55 | 81.95 | 158 | 248 694.36 | 63.53 | 1.290 | 1.753 | 1.108 to 9.382 | 0.042 |

| With RA/SLE/ SS/PBC |

17 | 19 252.53 | 88.30 | 2 | 5085.52 | 39.33 | 2.245 | 3.693 | 2.520 to 5.411 | <0.001 |

Ratio, incidence of patients with AA/AD divided by the incidence of patients without AA/AD.

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Sjögren’s syndrome without SLE, RA, SS or PBC. Secondary Sjögren’s syndrome: Sjögren’s syndrome with SLE, RA, SS or PBC.

*Adjusted adjusted for age, sex, comorbidities and medications, as listed in table 3, using Cox regression.

AA, aortic aneurysm; AD, aortic dissection; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; PYs, person years; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SS, systemic sclerosis.

Discussion

This is a retrospective cohort study including 10 941 patients with SS and 43 764 patients without SS matched by age, sex, year of index date of the SS diagnosis, comorbidities and medication use from a large-scale nationwide population-based database. During follow-up, SS was associated with an increased incidence of the development of AA/AD compared with the comparison cohort.

Our research findings should remind healthcare providers of new information that patients with SS exhibit an increased risk for AA or AD. Healthcare professionals should be aware of these life-threatening aortic events and aim to make early diagnosis of AA or AD. When patients with SS present with chest, back or abdominal symptoms, the possibility of AA or AD should be considered, with a specific and rapid examination.

Patients with SS exhibit an increased prevalence of developing traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and dyslipidaemia, which predispose patients to endothelial dysfunction and premature atherosclerosis. However, the disease-specific mechanisms associated with premature atherosclerosis in SS are not fully understood.19 In a recent review article, cardiovascular disease was reported to be one of the primary causes of mortality in patients with SS.20 PSS shares clinical and serological features with RA and SLE, and these two diseases are associated with acceleration of atherosclerosis.21 However, the pathophysiology between SS and AA or AD remains unclear, although several possible mechanisms have been proposed. Previous studies have demonstrated that both SS and AA/AD are induced by chronic inflammation.22–25 Recent studies have provided convincing evidence indicating that several signalling pathways are involved in both AA and SS, including the MAPK, TGF-β and MMP signalling pathways.12–15 Activation of the innate immune system and the production of interferons (IFNs) could be the first stages of PSS pathogenesis.26 IFNs and interleukin-21 could induce B-cell-activating factor and further activate B cell activity. In human salivary gland cells, IFN-γ modulates and increases MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression.27 The circulating levels of MMP-9 were increased in patients with definite SS compared with patients with possible SS.28 Furthermore, MMP-2 and MMP-9 also display a critical role in abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) formation.29 MMPs play roles in tissue destruction and the weakening of the matrix, as noted in liver cirrhosis, fibrotic lung disease, otosclerosis, atherosclerosis and multiple sclerosis.30 Several molecules that are activated in the salivary glands, including JNK, NF-κB and TGF-β, also lead to inflammation and reactive oxygen species production in the aortic matrix. This process may be a possible mechanistic pathway by which SS aggravates AA or AD.12 13 22 31–34

Low-dose steroids, such as prednisone, may be used to treat SS-induced joint and muscle pain. Prolonged or high-dose corticosteroid treatment likely causes disintegration of connective tissue of the media possibly together with primary aortic wall involvement and/or vascular damage in patients with autoimmune disorders which can result in AA enlargement and AD.30 35 In this study, the medical condition of steroids was matched. Therefore, the effect of steroids was mitigated. The strength of our study involves its population-based database design. We accounted for several aneurysm-related confounding factors. Although we adjusted the results extensively using Cox regression models, our study had several limitations and unmeasured confounders. The NHIRD registry is not able to provide detailed information on laboratory results, family histories and health-related lifestyle factors, such as alcohol consumption and tobacco use, which can increase the risk of AA/AD and were potential confounding factors in this study. This is a database study using NHIRD. All medical conditions for each case and the controls were categorised using the ICD-9-CM, in which diagnostic codes (up to five each) are coded. There may be a small number of coding errors or missing information when using this kind of administrative data, and limitations are bound to exist in any statistical method, even the propensity score matching. In our study, we also considered COPD incidence as a proxy variable for tobacco use to eliminate its potential confounding effect.18 The limitation is that not all smokers develop disease. Although our study identified the association between SS and AA/AD, the cohort study design did not enable determination of the cause–effect relationship. Further prospective follow-up studies, mechanistic studies and animal experiments should be performed.

Conclusion

Patients with SS exhibit an increased risk for developing AA or AD, and healthcare professionals should be aware of this risk when treating patients with SS. Increased aortic surveillance may be required in patients with SS.

bmjopen-2018-022326supp002.jpg (258.7KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2018-022326supp003.jpg (424.6KB, jpg)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Y-DT, J-CW and S-HT conceived and designed the study. W-CC provided the materials for the study. C-HC and S-JC analysed the data. C-JY and M-TL contributed reagents, materials and analysis tools. Y-DT, J-CW, W-IL and S-HT wrote the manuscript. All the authors approved the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei, Taiwan (TSGH-C105-058), Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei, Taiwan (TSGH-C105-173), Taoyuan Armed Forces General Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan (10514) and the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 106-2314-B-016 -008 -MY3).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei, Taiwan (TSGH IRB No.2-105-05-082) and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, et al. Classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:554–8. 10.1136/ard.61.6.554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mavragani CP, Moutsopoulos HM. The geoepidemiology of Sjögren’s syndrome. Autoimmun Rev 2010;9:A305–A310. 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Howard DP, Banerjee A, Fairhead JF, et al. Population-based study of incidence and outcome of acute aortic dissection and premorbid risk factor control: 10-year results from the Oxford Vascular Study. Circulation 2013;127:2031–7. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Olsson C, Thelin S, Ståhle E, et al. Thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection: increasing prevalence and improved outcomes reported in a nationwide population-based study of more than 14,000 cases from 1987 to 2002. Circulation 2006;114:2611–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.630400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yeh TY, Chen CY, Huang JW, et al. Epidemiology and medication utilization pattern of aortic dissection in taiwan: A population-based study. Medicine 2015;94:e1522 10.1097/MD.0000000000001522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shovman O, Tiosano S, Comaneshter D, et al. Aortic aneurysm associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cross-sectional study. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:2657–61. 10.1007/s10067-016-3372-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guy A, Tiosano S, Comaneshter D, et al. Aortic aneurysm association with SLE - a case-control study. Lupus 2016;25:959–63. 10.1177/0961203316628999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Juarez M, Toms TE, de Pablo P, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in women with primary sjögren’s syndrome: United kingdom primary sjögren’s syndrome registry results. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:757–64. 10.1002/acr.22227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garcia AB, Dardin LP, Minali PA, et al. Asymptomatic atherosclerosis in primary sjögren syndrome: Correlation between low ankle brachial index and autoantibodies positivity. J Clin Rheumatol 2016;22:295–8. 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chiang CH, Liu CJ, Chen PJ, et al. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome and risk of ischemic stroke: a nationwide study. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33:931–7. 10.1007/s10067-014-2573-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chiang CH, Liu CJ, Chen PJ, et al. Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome and the Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction: a nationwide study. Acta Cardiol Sin 2013;29:124–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Soejima K, Nakamura H, Tamai M, et al. Activation of mkk4 (sek1), jnk, and c-jun in labial salivary infiltrating t cells in patients with sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatol Int 2007;27:329–33. 10.1007/s00296-006-0229-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nakamura H, Kawakami A, Yamasaki S, et al. Expression of mitogen activated protein kinases in labial salivary glands of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 1999;58:382–5. 10.1136/ard.58.6.382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ito S, Ozawa K, Zhao J, et al. OLmesartan inhibits cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cell death induced by cyclic mechanical stretch through the inhibition of the c-jun n-terminal kinase and p38 signaling pathways. J Pharmacol Sci 2015;127:69–74. 10.1016/j.jphs.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang Y, Naggar JC, Welzig CM, et al. Simvastatin inhibits angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice: possible role of ERK. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009;29:1764–71. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.192609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheng CL, Kao YH, Lin SJ, et al. Validation of the national health insurance research database with ischemic stroke cases in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:236–42. 10.1002/pds.2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mao CT, Tsai ML, Wang CY, et al. Outcomes and characteristics of patients undergoing percutaneous angioplasty followed by below-knee or above-knee amputation for peripheral artery disease. PLoS One 2014;9:e111130 10.1371/journal.pone.0111130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu TM, Chuang YW, Yu MC, et al. Risk of cancer in patients with polycystic kidney disease: a propensity-score matched analysis of a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1419–25. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30250-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Valim V, Gerdts E, Jonsson R, et al. Atherosclerosis in Sjögren’s syndrome: evidence, possible mechanisms and knowledge gaps. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34:133–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Singh AG, Singh S, Matteson EL. Rate, risk factors and causes of mortality in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Rheumatology 2016;55:450–60. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sezis Demirci M, Karabulut G, Gungor O, et al. Is there an increased arterial stiffness in patients with primary sjögren’s syndrome? Intern Med 2016;55:455–9. 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.3472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sawada H, Hao H, Naito Y, et al. Aortic iron overload with oxidative stress and inflammation in human and murine abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015;35:1507–14. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vadacca M, Margiotta D, Sambataro D, et al. [BAFF/APRIL pathway in Sjögren syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus: relationship with chronic inflammation and disease activity]. Reumatismo 2010;62:259–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cifani N, Proietta M, Tritapepe L, et al. Stanford-A acute aortic dissection, inflammation, and metalloproteinases: a review. Ann Med 2015;47:441–6. 10.3109/07853890.2015.1073346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eagleton MJ. Inflammation in abdominal aortic aneurysms: cellular infiltrate and cytokine profiles. Vascular 2012;20:278–83. 10.1258/vasc.2011.201207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nocturne G, Mariette X. Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013;9:544–56. 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu AJ, Lafrenie RM, Park C, et al. Modulation of MMP-2 (gelatinase A) and MMP-9 (gelatinase B) by interferon-gamma in a human salivary gland cell line. J Cell Physiol 1997;171:117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hulkkonen J, Pertovaara M, Antonen J, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) gene polymorphism and MMP-9 plasma levels in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology 2004;43:1476–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dale MA, Suh MK, Zhao S, et al. Background differences in baseline and stimulated MMP levels influence abdominal aortic aneurysm susceptibility. Atherosclerosis 2015;243:621–9. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Amălinei C, Căruntu ID, Giuşcă SE, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases involvement in pathologic conditions. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2010;51:215–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zoukhri D, Macari E, Choi SH, et al. C-Jun NH2-terminal kinase mediates interleukin-1beta-induced inhibition of lacrimal gland secretion. J Neurochem 2006;96:126–35. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03529.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tsai SH, Huang PH, Peng YJ, et al. Zoledronate attenuates angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm through inactivation of Rho/ROCK-dependent JNK and NF-κB pathway. Cardiovasc Res 2013;100:501–10. 10.1093/cvr/cvt230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hall BE, Zheng C, Swaim WD, et al. Conditional overexpression of TGF-beta1 disrupts mouse salivary gland development and function. Lab Invest 2010;90:543–55. 10.1038/labinvest.2010.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jones JA, Spinale FG, Ikonomidis JS. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in thoracic aortic aneurysm development: a paradox in pathogenesis. J Vasc Res 2009;46:119–37. 10.1159/000151766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sholter DE, Armstrong PW. Adverse effects of corticosteroids on the cardiovascular system. Can J Cardiol 2000;16:505–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022326supp001.pdf (213.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022326supp002.jpg (258.7KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2018-022326supp003.jpg (424.6KB, jpg)