Abstract

Notch ligand Delta-like ligand 4 (DLL4) has been shown to regulate CD4 T-cell differentiation, including regulatory T cells (Treg). Epigenetic alterations, which include histone modifications, are critical in cell differentiation decisions. Recent genome-wide studies demonstrated that Treg have increased trimethylation on histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) around the Treg master transcription factor, Foxp3 loci. Here we report that DLL4 dynamically increased H3K4 methylation around the Foxp3 locus that was dependent upon upregulated SET and MYDN domain containing protein 3 (SMYD3). DLL4 promoted Smyd3 through the canonical Notch pathway in iTreg differentiation. DLL4 inhibition during pulmonary respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection decreased Smyd3 expression and Foxp3 expression in Treg leading to increased Il17a. On the other hand, DLL4 supported Il10 expression in vitro and in vivo, which was also partially dependent upon SMYD3. Using genome-wide unbiased mRNA sequencing, novel sets of DLL4- and Smyd3-dependent differentially expressed genes were discovered, including lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (Lag3), a checkpoint inhibitor that has been identified for modulating Th cell activation. Together, our data demonstrate a novel mechanism of DLL4/ Notch-induced Smyd3 epigenetic pathways that maintain regulatory CD4 T cells in viral infections.

INTRODUCTION

Many infectious and chronic inflammatory diseases are characterized by inappropriate or dysregulated CD4 + T-cell immunity with diverse cytokine expression profiles and distinct effector functions. Naive CD4 T cells differentiate into subsets of CD4 T-helper cell (Th) upon T-cell receptor activation, cell-associated co-stimulatory proteins, and cytokine stimulation. Regulatory T cells (Treg), especially induced Treg (iTreg), constrain airway allergic inflammation1–3 and immunopathology upon viral infection, e.g., respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).4–6 Forkhead box P3 (Foxp3) is the master transcription factor of Treg and is induced by T cell receptor (TCR) activation in the presence of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β.7,8 Both Foxp3 + and Foxp3-CD4 give rise to interleukin (IL)-10 secretion to limit immunopathology of airway inflammation such as RSV infection.9–12 In contrast, Treg have shown considerable plasticity and can convert to IL-17A-producing cells that exacerbate airway inflammation accompanied by asthma-associated polymorphisms.13 Both transcription factors and posttranslational modifications fine-tune the activity of Foxp3 promoter and its conserved non-coding DNA sequence (CNS) 1, 2, 3 to control the expression of Foxp3, as well as the function and stability of Treg populations.8,14 However, the molecular basis for Foxp3 regulation in Treg during pulmonary viral infections have not been fully elucidated.

DNA modifications alter gene expression without changing the bases of DNA sequence to establish epigenetic changes that can alter cell phenotypes. Epigenetic modifications, including histone modifications, DNA methylation, chromatin remodeling, and microRNAs, are indispensable for optimized Th cell differentiation. 15,16 One of the permissive epigenetic marks histone 3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) is enriched around the activated gene promoters, whereas the suppressive marks H3K27me3 are removed compared with uncommitted naive CD4 T cells.17 In Treg, H3K4me3 are mostly enriched around Foxp3 CNS1 and its promoter but not as significantly around CNS2 and CNS3.14 Another mechanism, DNA methylation on CpG motifs was reported to contribute to Foxp3 instability,18,19 in part through DNMTs and TETs.20,21 Histone modification by EZH2 through the removal of H3K27me3 around Foxp3-bound genes stabilizes Treg identity22 and enhances suppressive function in response to inflammation.23 Our lab previously identified that SET and MYND domain containing protein 3 (SMYD3), which is a H3K4 di- and trimethyltransferase,24 was induced by transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and promoted iTreg differentiation to ameliorate immunopathogenesis in the pulmonary viral infection.25 The present studies further extend those earlier findings by identifying a Notch-mediated epigenetic mechanism to regulate Treg function by inducing SMYD3 and regulating Treg function.

Notch signaling is well-conserved throughout metazoans and orchestrates T-cell development and differentiation decisions.26–28 In CD4 T cells, Notch signaling directly initiates Th signature transcription, such as Ifng in Th1,29 Il4 and Gata3 in Th2,30 Il17a and Rorc in Th17,31 and Il9 in Th9 differentiation.32 The mechanism of Notch in iTreg cell differentiation is complex. Notch directly induces Treg master transcription factor—Foxp3—through RBP-Jκ in iTreg differentiation,33 and Delta-like ligand 4 (DLL4)/Notch supported the iTreg phenotype in vitro and in vivo in airway inflammation.34,35 In addition, constitutively active Notch1 in already differentiated Foxp3 + Treg destabilized peripheral Treg in part through CpG motif methylation on Foxp3 CNS2.36 Thus, Notch activation has a context-dependent activation function in Th cells that appears to be cell and disease specific.

Here we report that Notch signaling through its ligand DLL4 directly regulated Smyd3 expression during early stages of iTreg differentiation leading to increased H3K4me3 around the Foxp3 locus to stabilize Foxp3 expression. DLL4 inhibition and Smyd3 deletion introduced cytokine dysregulation including increased IL-17A and decreased IL-10 to confer immunopathology upon viral infection. Using genome-wide RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), we further identified Treg signature genes—including lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (Lag3)—which are regulated by DLL4 and Smyd3. These latter studies also strongly suggest that these same signals have an overall effect on the immune environment by altering both putative Foxp3 + Treg and Foxp3-T cells. Together, our study reveals a novel pathway of DLL4/Notch activation that epigenetically can control iTreg differentiation and function through a SMYD3-induced mechanism altering immune environment in pulmonary viral infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Six- to 8-week-old female C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Six- to 8-week-old female Foxp3EGFP mice (B6.Cg-Foxp3tm2(EGFP)Tch/J) were bought from Jackson Laboratory and bred in-house. CD4-specific SMYD3 knockout mice (Smyd3 f/f x Cd4-Cre) were generated in-house as described.25 7~9 week olds CD4-specific dominant-negative MAML1 mice (DNMAML) mice (ROSA26DNMAMLf × Cd4-Cre) and CD4-specific RBP-Jκ knockout mice (Rbpj f/f × Cd4-Cre) were generated as described.37–39 All mice were housed in the University Laboratory Animal Facility under animal protocols approved by the Animal Use Committee in the University of Michigan.

RSV infection

RSV Line 19 was clinical isolate originally from a sick infant in University of Michigan Health System to mimic human infection.40 Mice were anesthetized and infected intratracheally (i.t) with 1 × 105 pfu of Line 19 RSV, as previously described.41

Histopathology

Left lobe of lung was fixed with 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin, and 4 μm of sections were stained with Periodic acid-Schiff stain to detect mucus.

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) by following the manufacturer’s protocol, and 500 ng of total RNA were reverse transcribed to cDNA to determine gene expression using TaqMan gene expression primer/probe sets. Muc5ac and Gob5 expression were assessed by custom primers as described.42 Dll4 were detected by SYBR as described.43 Dll4 primers: 5′-AGGTGC CACTTCGGTTACACAG-3′ and 5′-CAATCACACACTCGTTCCTCTCTT C-3′. Smyd3 were detected by TaqMan probes (Catalog number 4331182, Applied Biosystems) that expanded the junction of exon 9–10. Detection was performed in ABI 7500 Real-time PCR system. Gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt=experimental Ct − input Ct) − (control Ct−input Ct) and normalized with Gapdh as input control.

Murine lung cells isolation

Mice lungs were chopped. Lung and mediastinal lymph node (mLN) were enzymatically digested using 1 mg/mL Collagenase A (Roche) and 25 U/mL DNaseI (Sigma-Aldrich) in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal calf serum for 45 min at 37 °C. Tissue were further dispersed through 18 gauge needle/5 mL syringe and filtered through 100 μm nylon mesh twice.

Cytokine production assay

Cells (5 × 105) from mLN cells were plated in 96-well plates and re-stimulated with 105 pfu RSV Line 19 for 48 h. IL-17A and IL-10 levels in supernatant were measured with Bio-plex™ cytokine assay (Bio-Rad).

Extracellular and intracellular flow cytometry analysis

Single-cell suspension of lung and lymph node were stimulated with 100 ng/mL Phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate, 750 ng/mL Ionomycin, 0.5 μL/mL GolgiStop (BD), and 0.5 μL/mL GolgiPlug (BD) for 5 h if mentioned. After excluding dead cells with LIVE/ DEAD Fixable Yellow stain (Invitrogen), cells were pre-incubated with anti-FcγR III/II (Biolegend) for 15 min and labeled with the following antibody from Biolegend, unless otherwise specified: anti-CD3 (145-2C11), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8α (53-6.7), CD25 (PC61). After 30 min of incubation at 4 °C, cells were washed and proceed to intracellular staining. For intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized with Transcription factors staining buffer set (eBioscience). Cells were labeled with directly conjugated antibody from eBioscience: Foxp3 (FJK-16s) for 30 min at room temperature. Flow cytometry data were acquired from LSRII (BD) or Novocyte (ACEA) flow cytometer and were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

For intracellular H3K4me3 staining, single-cell suspension were fixed and permeabilized with Transcription factors staining buffer set (eBioscience) overnight at 4 °C to have optimal permeabilization into nucleus. After three washes, sample were labeled with primary antibody anti-H3K4me3 (Millipore #07-473) in 1:200 dilution for 30 min at room temperature and secondary antibody antigen presenting cell (APC) or fluorescein isothiocyanate-antirabbit antibody for 20 min at room temperature.

Naïve CD4 T-cell isolation and stimulation

CD4+ CD25−CD62LhiCD44lo naive T cells were enriched from spleen using the naive CD4 T cells isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) with more than 92% purity. Naive T cells were then plated and cultured in 24-well plates. Naive T cells (106/0.5 mL) were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (2.5 μg/mL; eBioscience), soluble anti-CD28 (3 μg/mL; eBioscience), and plate-bound recombinant DLL4 (1.65 μg/mL, R&D). In addition, recombinant cytokines and neutralizing antibodies were added to skew toward different Th cells in vitro. For Th1: mouse IL-12 (10 ng/mL), anti-IL-4 neutralizing antibody (10 μg/mL; eBioscience); for Th2: mouse IL-4 (10 ng/mL; R&D System), anti-IFNγ neutralizing antibody (10 μg/mL; eBioscience), anti-IL-12/23 p40 neutralizing antibody (10 μg/mL); for Th17 cells: mouse IL-6 (10 ng/mL; R&D System), human TGF-β1 (2 ng/mL; R&D System), anti-IFNγ neutralizing antibody (10 μg/mL; eBioscience), anti-IL-4 neutralizing antibody (10 μg/mL; eBioscience), and anti-IL-12/23 p40 neutralizing antibody (10 μg/mL; eBioscience) were added; for IL-27-inducing TR1, mouse IL-27 (20 ng/mL, R&D) were added; to skew toward in vitro-iTreg cells (iTreg), human TGFβ1 (2 ng/mL; R&D System) and mouse IL-2 (10 ng/mL; R&D System) were added at the same time.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed based on the manufacturer’s instruction (Upstate Biotechnology) as described.44 In brief, more than 2 × 106 stimulated T cells were cross-linked with 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min in room temperature. After stop cross-linking with 125 mM glycine, cells were steep frozen. After lysing cell pellet in 200 μL SDS lysis buffer, the resulting lysate were sonicated a Branson Sonifier 450 (VWR, West Chester) under the following condition: 3 times for periods of 11 s each. After centrifuging, the supernatant was diluted and 5% were saved as Input control. Other diluted supernatant underwent immunoprecipitation under 4 °C overnight with the following antibodies: IgG control (Millipore), anti-H3K4me (Milllipore #07-436), anti-H3K4me3 (Millipore #07-473 for Fig. 1; Abcam #ab8580 for Fig. 3), and anti-RBP-Jκ (Abcam, #ab25949). After pulling down precipitated complex by protein A beads, cross-linking was reversed by high salt in 5 h under 65 °C. DNA was purified by standard phenol/chloroform and ethanol precipitation and was subjected to real-time PCR. ChIP-specific enrichment was calculated using the ΔCt method as 2−(experimental Ct−input Ct)

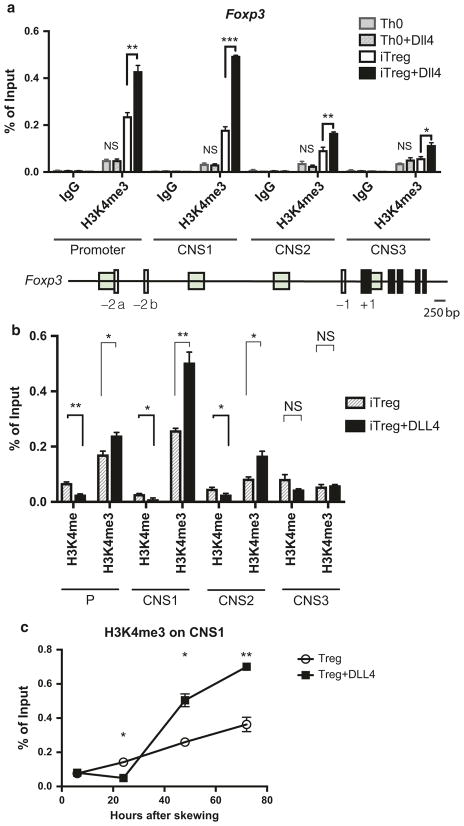

Fig. 1.

DLL4-enriched permissive histone mark H3K4me3 around Foxp3 promoter and consensus non-coding sequences during iTreg differentiation. a 2 × 106 of naive CD4 T cells were skewed toward Th0 or iTreg differentiation with or without DLL4 stimulation in vitro. Chromatin immunoprecipitation were performed to detect H3K4me3 around Foxp3 promoter, consensus non-coding sequence (CNS)1, CNS2, CNS3 after 72 h. b Changes of H3K4me and H3K4me3 by DLL4 stimulation during iTreg differentiation was detected at 48 h of skewing. c H3K4me3 kinetics at Foxp3 CNS1 after 6 h, 24 h, 48 h and 72 h post iTreg differentiation were measured with or without DLL4 stimulation in vitro. Data represent mean ± SEM. Data were from one experiment representative of two to three experiments. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.005; *** P < 0.0005; NS, no significance (unpaired two-tailed t-test)

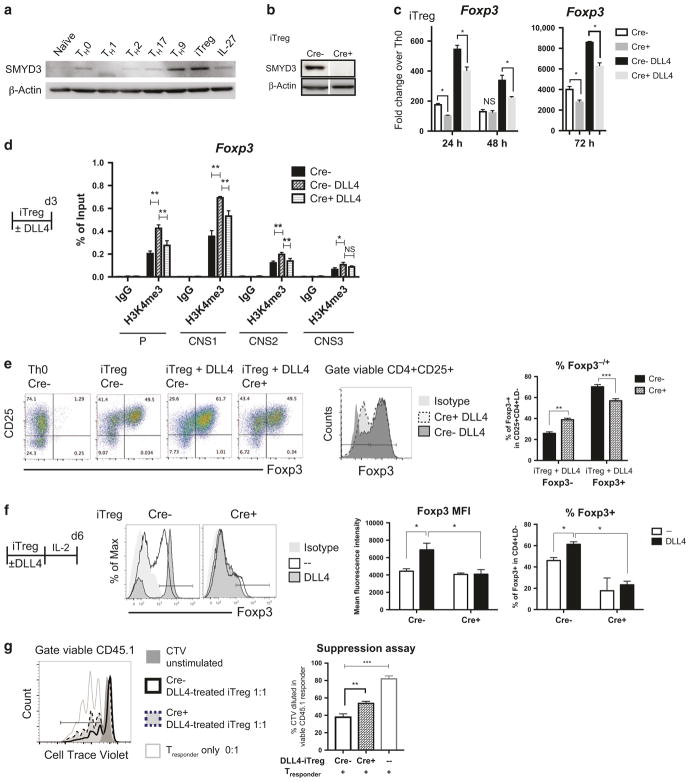

Fig. 3.

Smyd3 regulated DLL4-enhanced iTreg differentiation and function in vitro. a Naive CD4 T cells (106) from wild-type B6 spleen were activated (Th0) or differentiated to Th1, Th2, Th17, Th9, iTreg, and IL-27 TR1. After 72 h, SMYD3 were blotted. b Naive CD4 T cells (106) from Cre− control or Cre + CD4-specific SMYD3 conditional knockout (cKO) were differentiated to iTreg. After 72 h, SMYD3 level were quantified by western blotting. c Smyd3 mRNA level were measure in iTreg and DLL4-stimulated iTreg differentiation at 24, 48, and 72 h from Cre− control and Cre + Smyd3 cKO. d Naive CD4 T cells (2 × 106) from Cre− control with or without DLL4 stimulation or Cre + CD4-specific SMYD3 were differentiated to iTreg. After 72 h, H3K4me3 were precipitated, and Foxp3 promoter and CNS1, 2, 3 were qPCR quantified compared with input control. e Naive CD4 T cells (106) from Cre− control or Cre + SMYD3 cKO were activated (Th0) or differentiated to iTreg with or without DLL4. After 72 h of differentiation, Foxp3 and CD25 were labeled and quantified by flow cytometry. f Naive CD4 T cells (106) from Cre− control or Cre + SMYD3 cKO were activated (Th0) or differentiated to iTreg with or without DLL4. After 72 h of differentiation, both Th0 and iTreg were rested in IL-2 10 ng/mL for another 72 h. Foxp3 were detected and quantified by flow cytometry. g After 6 days of iTreg differentiation with DLL4 as described in f, viable DLL4-exposed iTreg were sorted out as DAPI−CD25+ and co-cultured with Cell Trace violet (CTV) labeled CD45.1+ naive T cells with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads. After 3 days in co-culture, proliferation was assessed by CTV dilution in CD45.1 + responder cells. Data represent mean ± SEM. Data were from one experiment representative of two to three experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005; *** P < 0.0005; NS, no significance (unpaired two-tailed t-test)

Smyd3 primers P0: 5′-GCCATCAAGGTCCTGGTGAA-3′ and 5′-CTTAGGCTTCGGTTGGCAGA-3′; Smyd3 primers P2: 5′-ACAGGG CTTCTCTGTTGTATAGC-3′ and 5′-GAGTTTAAAGCCAGCGTGGT-3′.

Foxp3 promoter and CNS1, 2, 3 primers were designed as described.14

Immunoblot analysis

Total cells lysates were prepared using 1 × Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling). Same amount of 3~10 μg of total proteins were separated by Nu-PAGE (Invitrogen) and transferred on nitrocellulose membrane. The primary Ab anti-SMYD3 (Abcam, ab16027 for Fig. 3a, b, ab187149 for Fig. 2g) and anti-β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) were diluted in 5% bovine serum albumin in 1 × TBST with 1:1000 and 1:5000, respectively.

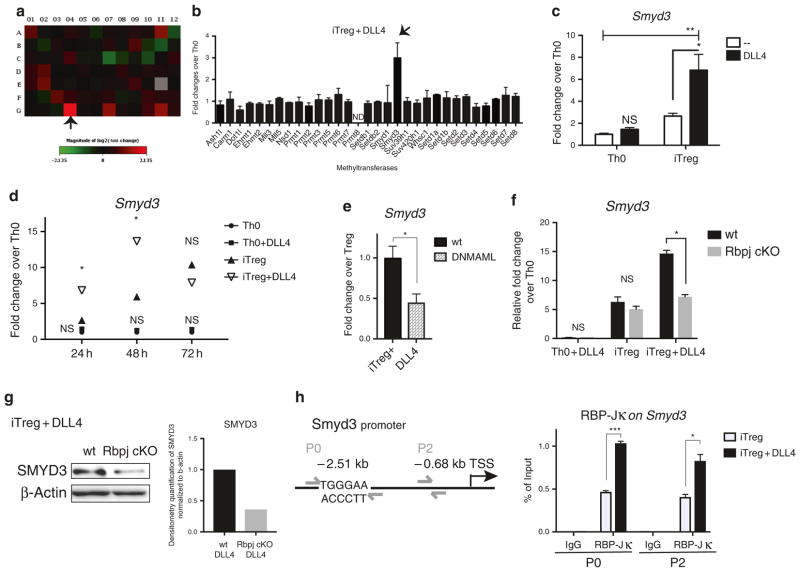

Fig. 2.

DLL4/Notch upregulated SET and MYND domain containing protein 3 (Smyd3). a The expression of 87 epigenetic enzymes in epigenetic PCR array (SA Bioscience, PAMM-085) were measured in DLL4-stimulated iTreg compared to Th0 after 48 h of skewing. Fold changes were indicated with a heatmap. The following genes were either up or downregulated more than twofold: Dnmt1 (A11), Hdac9 (C7), Nek6 (E2), Smyd3 (G4), Ube2a (G7), Usp21 (G11). b All the methyltransferases in the PCR array were presented. The arrow indicated Smyd3 as the most-expressed methyltransferase in vitro. c Smyd3 expression level were measured after 24 h of Th0 and iTreg differentiation with or without DLL4 activation in vitro. d Kinetics of Smyd3 expression during Th0 and iTreg differentiation with or without DLL4 activation at 24, 48, 72 h. e Naive CD4 T cells were isolated from wild-type B6 or CD4-specific Dominant-negative MAML1 (DNMAML) mice. Smyd3 were measured after 48 h of iTreg differentiation + DLL4 stimulation in vitro. f Naive CD4 T cells were isolated from CD4-specific Rbpj knockout mice (Rbpj cKO) or Wild-type unfloxed littermate control (wt). Activated (Th0) or iTreg differentiation with or without DLL4 were performed. After 48 h, CD4 T cells were harvest and Smyd3 were measured. g SMYD3 expression was blotted after 72 h of iTreg differentiation in wt and Rbpj cKO. The relative SMYD3 level in Rbpj cKO versus wt were quantified by densitometry software (ImageJ) and normalized with internal control—β-actin. This was repeated in 3 different experiments with similar results. h Naive CD4 T cells (2X106) were isolated from wild-type B6 mice. After iTreg differentiation with or without DLL4 stimulation for 6 h, RBP-Jκ were precipitated and RBP-Jκ-bound DNA sequence were PCR with Smyd3 primer P0 and P2. Data represent mean ± SEM. Data were from one experiment representative of two to three experiments. PCR array is one-time experiment. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.005; *** P < 0.0005; NS, no significance (unpaired two-tailed t-test)

Cell sorting and in vitro suppression assay

Single-cell sorting was performed on FACSAria II (BD). DAPI− CD4+ Foxp3-EGFP+ or DAPI-CD4 + Foxp3-EGFP− from mLN were sorted with more than 93% efficiency and the sorted cells were directly collected in TRIzol for mRNA; for in vitro suppression assay, DAPI−CD4 + CD25 + viable iTreg were sorted. Suppression assay was performed as described with small modification.45 In brief, naive T cells isolated from CD45.1 mice were labeled with Cell Trace Violet (CTV) (Invitrogen). Labeled CD45.1 + naive T cells (2.5 × 104) were co-cultured with same number of iTreg in 96-well round-bottom plate. Dynabeads® mouse T activator CD3/CD28 (0.625 μL; Invitrogen) were added to 0.2 mL of culture. After 72 h, cells were collected and CD45.1+ responder cell proliferation were accessed by CTV dilution.

RNA-seq sample preparation and data analysis

Naive CD4 T cells were enriched as described above from three female Cre-control and three Cre + Smyd3 conditional knockout mice. After 48 h of iTreg differentiation, total RNA was extracted and cleaned up with QIAGEN RNeasy kit. Total RNA (100 ng) isolated from each biological replicate was subjected to poly-A selection, followed by next-generation sequencing library preparation using TruSeq RNA library prep kit (Illumina). The libraries were sequenced on HiSeq4000 platform by single-end, 50 nt method with around 30 million reads per sample. The library prep and sequencing were performed by DNA sequencing core in the University of Michigan Medical School.

After trimming with Trimmomatic and FastQC to generate the best reads quality in every sample, reads were aligned to reference genome GRCm38 using HISAT246 and counted the reads using HTSeq-count.47 Finally, DESeq2 was implemented to normalize the reads and to perform differential analysis with likelihood ratio test.48 Principle component analysis (PCA) was performed in DESeq2. Venn diagram, volcano plot, and heatmap were drawn in R. Gene Ontology were annotated using DAVID functional annotation and treemap were drawn with REVIGO.49

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by Prism6 (GraphPad). Data presented are mean values ± SEM. Comparison of two groups was performed in unpaired, two-tailed, Student’s t-test. Comparison of three or more groups was analyzed by analysis of variance with Tukey’s post tests. Significance was indicated at the level of *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005.

RESULTS

Notch ligand DLL4 promotes gene activation and histone modification around Foxp3 during iTreg differentiation in vitro

DLL4/Notch activation through the canonical Notch signaling pathway enhances Treg differentiation by stimulating Foxp3 gene expression.33,34 H3K4me3 is a permissive histone mark that represents gene activation and is enriched around Foxp3 locus in Foxp3 + Treg.50,51 Here we hypothesized that DLL4 may enrich H3K4me3 around the Foxp3 gene to enhance iTreg differentiation. Using ChIP analysis, the data showed that DLL4 stimulation drove the enhancement of H3K4me3 around the Foxp3 promoter as well as functional conserved non-coding sequence 1 (CNS1), CNS2, and CNS3 at 72 h, specifically in iTreg but not during Th0 activation (Fig. 1a). To characterize the level of H3K4 mono-methylation (H3K4me) and H3K4me3 in the Foxp3 promoter and enhancers during early iTreg differentiation, we immunoprecipitated both H3K4me and H3K4me3 at 48 h of iTreg differentiation. DLL4 decreased H3K4me, while it increased H3K4me3 around the Foxp3 promoter, as well as CNS1, 2, and 3 (Fig. 1b). Foxp3 induction in the presence of TGF-β-Smad3 is dependent on CNS1,3,7,8 allowing us to focus on the dynamics of H3K4me3 on Foxp3 CNS1. DLL4 stimulation increased H3K4me3 at 48 and 72 h post differentiation at the CNS1 enhancer (Fig. 1c). These data suggested that Notch ligand DLL4 activation changed the H3K4me3 around Foxp3 promoter and its functional enhancer during iTreg differentiation.

DLL4 and Notch signaling regulated SMYD3 during iTreg differentiation

The addition of methyl groups on H3K4 is mediated by histone lysine methyltransferases.52 Therefore, we hypothesized that DLL4 would regulate an epigenetic enzyme to catalyze H3K4me3 around the Foxp3 locus during iTreg differentiation. To examine epigenetic enzyme expression in iTreg, an epigenetic enzyme PCR array was used to compare the DLL4-stimulated gene profile in iTreg differentiation at 48 h. The array analysis indicated that Smyd3 was the most upregulated candidate in the iTreg + DLL4 activation (Fig. 2a). It was also the most highly upregulated methyltransferase when examining all methyltransferases in the array (Fig. 2b). Smyd3 expression was significantly increased by DLL4 stimulation in iTreg cells but not in Th0 as determined by reverse-transcription PCR (Fig. 2c). In the time-course study, DLL4 significantly increased Smyd3 expression during early iTreg differentiation (at 24 and 48 h) compared with iTreg without DLL4 and not in Th0 stimulation (Fig. 2d). To further investigate whether DLL4-upregulated Smyd3 expression is Notch-dependent, we used CD4-specific Rbpj knockout mice and CD4-specific DNMAML that deleted canonical Notch transcription factor and inactivated intracellular Notch signaling activation, respectively. The expression of Smyd3 was significantly decreased in Rbpj−/− CD4 T cells and DNMAML expressing CD4 T cells during DLL4-stimulated iTreg differentiation (Fig. 2e, f), and CD4 T cells from Rbpj knockout expressed less SMYD3 (Fig. 2g). These data suggest that both Smyd3 and SMYD3 are dependent on canonical Notch activation. To investigate whether Smyd3 is a potential target gene of canonical Notch signaling, we examined the Smyd3 promoter and found 5′-TGGGAA-3′ RBP-Jκ consensus binding sites31,53 upstream of the Smyd3 transcription start site using in silico analysis (Fig. 2h). We performed a promoter walk and representative primer sets where P0 and P2 showed that RBP-Jκ directly bound to the Smyd3 promoter with DLL4 stimulation further enriching RBP-Jκ binding at 6 h of early iTreg differentiation (Fig. 2h). Together, these data demonstrated that DLL4 and intracellular Notch signaling facilitated increased and accelerated Smyd3 expression during iTreg differentiation.

DLL4-facilitated Foxp3 expression was SMYD3 dependent

SMYD3 is enriched in TGF-β-induced iTreg differentiation.25 In addition, both iTreg and Th9 (TGF-β + IL-4) had enriched SMYD3 protein levels, but it was at a much lower level in naïve CD4, Th0, Th1, Th2, Th17, and IL-27 stimulation in vitro (Fig. 3a). Importantly, SMYD3 protein expression was negligible in iTreg cells from Cre + CD4-specific Smyd3 knockout (Smyd3 cKO) mice (Fig. 3b). As DLL4 upregulates Foxp3 expression during iTreg differentiation and DLL4/Notch further upregulated Smyd3, we hypothesized that DLL4 and Smyd3 cooperatively upregulated Foxp3. The data showed that DLL4 facilitated Foxp3 expression in Cre-littermate control, whereas deletion of Smyd3 decreased Foxp3 expression in the presence of DLL4 at 48 h during iTreg differentiation (Fig. 3c). Consistent with Fig. 1, DLL4 stimulation upregulated H3K4me3 around Foxp3 promoter as well as CNS1, 2, and 3 in Cre− control, whereas DLL4 did not increase H3K4me3 in Cre + Smyd3 cKO CD4 T cells (Fig. 3d). These data suggested that Smyd3 mediated DLL4-enriched H3K4me3 around Foxp3 regulatory elements, the promoter, CNS1 and CNS2. Finally, Smyd3 was shown help facilitate DLL4-induced iTreg differentiation and maintenance by flow cytometric analysis. Foxp3 + iTreg numbers were significantly decreased in Smyd3 cKO at 3 days post iTreg differentiation (Fig. 3e) and continued to be impaired after 6 days (Fig. 3f). These results revealed that Smyd3 promoted iTreg differentiation in vitro. To further specify the role Smyd3 in iTreg function, we performed a suppression assay. DLL4-treated Cre− control and Cre + Smyd3 cKO iTreg were sorted and cultured with CD45.1 responder cells in 1 to 1 ratio for 72 h, and the anti-CD3 + anti-CD28-stimulated responder cells proliferation were monitored by CTV dilution. Tresponder proliferation were indeed suppressed in the presence of iTreg. Importantly, Tresponder were more proliferative (more CTV dilution) when co-cultured with Cre + Smyd3 KO iTreg than control iTreg, suggesting that Smyd3 supported iTreg function in vitro (Fig. 3g). Thus, DLL4 appears to support Foxp3 expression in part through SMYD3 leading to histone modification and expression of Foxp3.

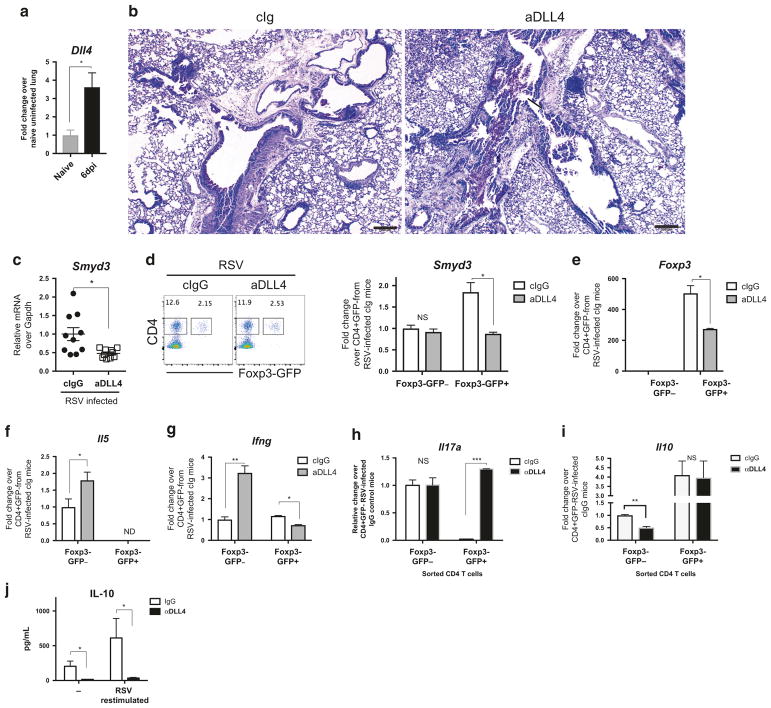

DLL4 blockade decreased Smyd3 and enriched Il17a expression in Foxp3 + Treg during RSV infection

Previous studies have demonstrated that dendritic cell expressed DLL4-induced peripheral Treg modulated immunopathology of RSV infection.34 To further investigate whether DLL4 regulated Smyd3 expression in peripheral Treg during mucosal inflammation in vivo, we utilized our RSV infection mouse model that triggers type 2 and Th17 inflammation54–57 with pathology controlled by Treg cells.4–6 The studies first confirmed that RSV infection increased Dll4 expression at 6 days post infection (6 dpi) and DLL4 inhibition by specific antibodies increased mucus production as described (Fig. 4b).34 Smyd3 was also significantly decreased by DLL4 inhibition in mLN (Fig. 4c), suggesting that DLL4 regulated Smyd3 expression in vivo. However, global H3K4me3 modification in CD4 T cells, especially Foxp− conventional CD4 were not significantly altered by DLL4 neutralization, whereas the Foxp3+ populations were reduced (Supplementary Figure 1A,B). To further examine the role of DLL4 on CD4 Treg cells, Foxp3EGFP knock-in mice were i.t. infected with RSV and treated with neutralizing anti-DLL4 antibody. At 6 dpi, viable CD4+Foxp3EGFP−/+cells from mLN were sorted. DLL4 neutralization decreased Smyd3 expression (Fig. 4d) and Foxp3 expression in GFP + (Foxp3 + ) CD4 T cells (Fig. 4e). Furthermore, DLL4 inhibition increased Il5 expression in GFP − but not GFP + (Fig. 4f), whereas DLL4 inhibition differentially affected Ifng expression in GFP − vs. GFP + (Fig. 4g). We further investigated IL-17A that exacerbates RSV immunopathology. 56 Il17a was increased in Foxp3-GFP + but not GFP − CD4 T cells (Fig. 4h). IL-10 from CD4 + T cells were reported to regulate RSV immunopathology5,11 and in these studies the data showed that DLL4 neutralization decreased Il10 mRNA expression in Foxp3EGFP− CD4 (Fig. 4i) and total IL-10 protein production in draining lymph node (Fig. 4j). These data suggest that DLL4 supports Smyd3 expression to regulate Th17-like Treg plasticity, with an additional effect on IL-10 in CD4 T cells in vivo during RSV infection.

Fig. 4.

DLL4 inhibition changed Th cytokine profile in vivo during RSV infection. a Wild-type Balb/c mice were intratracheally infected with Line 19 RSV. DLL4 expression were measured at 6 days post infection (dpi). N = 4 in each group. b DLL4 were neutralized at 0, 2, 4, 6 dpi. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining of formalin-fixed lung section from 8 dpi. Bar, 200 μm. ↑ indicates the detection of mucin, and

designates mononuclear cells aggregates. c Smyd3 expression in mediastinal lymph node (mLN) were measured at 6 dpi after DLL4 inhibition. N = 10 in each group. d Foxp3-EGFP knock-in mice were intratracheally infected with RSV. DLL4 were neutralized at 0, 2, 4 dpi. mLN cells were collected. Viable CD4 + Foxp3-EGFP+/− cells were sorted from mLN and Smyd3 expression were measured. N = 3 in each group. e Viable CD4 + Foxp3-EGFP+/− cells were sorted from mLN. Foxp3 mRNA were measured. N = 3 in each group. f

Il5 mRNA in both Foxp3-EGFP− and Foxp3-EGFP+ were measured. g

Ifng mRNA in both Foxp3-EGFP− and Foxp3-EGFP+ were measured. h Foxp3-EGFP knock-in mice were intratracheally infected with RSV. DLL4 were neutralized at 0, 2, 4, 6 dpi. mLN cells were collected at 8 dpi. Viable CD4 + Foxp3-EGFP+/− cells were sorted from mLN, and Il17a expression in both Foxp3-EGFP− and Foxp3-EGFP+ were measured. i

Il10 expression in both Foxp3-EGFP− and Foxp3-EGFP+ viable CD4 T cells in mLN were measured at 8 dpi. j IL-10 production by control IgG or anti-DLL4-treated mLN cells were harvest at 8 dpi and measured after 48 h of RSV re-stimulation. Data represent mean ± SEM. Data were from one experiment representative of two experiments with 3~10 mice per time point, with samples from each mouse processed and analyzed separately. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.005; *** P < 0.0005; NS, no significance (unpaired two-tailed t-test)

designates mononuclear cells aggregates. c Smyd3 expression in mediastinal lymph node (mLN) were measured at 6 dpi after DLL4 inhibition. N = 10 in each group. d Foxp3-EGFP knock-in mice were intratracheally infected with RSV. DLL4 were neutralized at 0, 2, 4 dpi. mLN cells were collected. Viable CD4 + Foxp3-EGFP+/− cells were sorted from mLN and Smyd3 expression were measured. N = 3 in each group. e Viable CD4 + Foxp3-EGFP+/− cells were sorted from mLN. Foxp3 mRNA were measured. N = 3 in each group. f

Il5 mRNA in both Foxp3-EGFP− and Foxp3-EGFP+ were measured. g

Ifng mRNA in both Foxp3-EGFP− and Foxp3-EGFP+ were measured. h Foxp3-EGFP knock-in mice were intratracheally infected with RSV. DLL4 were neutralized at 0, 2, 4, 6 dpi. mLN cells were collected at 8 dpi. Viable CD4 + Foxp3-EGFP+/− cells were sorted from mLN, and Il17a expression in both Foxp3-EGFP− and Foxp3-EGFP+ were measured. i

Il10 expression in both Foxp3-EGFP− and Foxp3-EGFP+ viable CD4 T cells in mLN were measured at 8 dpi. j IL-10 production by control IgG or anti-DLL4-treated mLN cells were harvest at 8 dpi and measured after 48 h of RSV re-stimulation. Data represent mean ± SEM. Data were from one experiment representative of two experiments with 3~10 mice per time point, with samples from each mouse processed and analyzed separately. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.005; *** P < 0.0005; NS, no significance (unpaired two-tailed t-test)

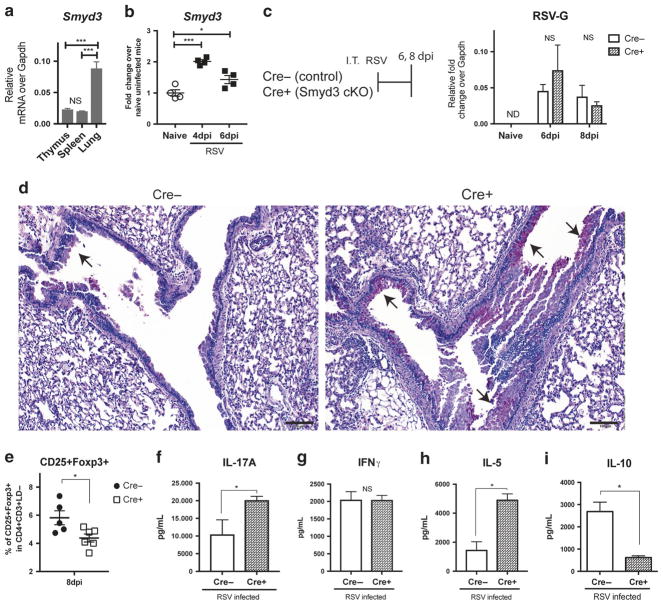

Smyd3 impeded RSV lung immunopathology, regulated Treg and cytokine productions in CD4 T cells

To examine the relative contribution of Smyd3 in lymphoid vs. non-lymphoid tissue, Smyd3 expression was measured in the thymus, spleen, and lung. Here, the data showed that Smyd3 was more highly expressed in the lung than either primary or secondary lymphoid organs (Fig. 5a) and RSV infection further upregulated Smyd3 in the lung (Fig. 5b). Next, we investigated Smyd3 function in CD4 T cells during RSV infection. Using CD4-specific Smyd3 knockout mice (Smyd3 cKO), more mucus staining and globlet cell hyperplasia in lung was observed, indicating more severe immunopathology in Smyd3 cKO at 8 dpi (Fig. 5d), whereas the viral clearance was maintained in Cre + knockout post RSV infection (Fig. 5c). Smyd3 cKO had decreased CD25 + Foxp3 + Treg (Fig. 5e) as previously described,25 with Treg functional markers such as CTLA-4, OX40, and ICOS that were not changed between Cre− control and Cre + Smyd3 cKO at both 6 dpi and 8 dpi (data not shown). Deletion of Smyd3 conferred the lower expression level of global H3K4me3 modification in CD4 in draining lymph nodes at 6 dpi post RSV infection (Supplementary Figure 1C). Moreover, deletion of Smyd3 led to increased IL-17A in mLN after RSV re-stimulation (Fig. 5f), while IFNγ was unchanged with type 2 cytokine IL-5 was increased in Smyd3 cKO (Fig. 5g, h). Both Foxp3 + Treg and Foxp3−IL-10-producing TR1 have been shown to be suppressive in RSV infection.5,6,11 Smyd3 cKO mice secreted less anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in re-stimulated mLN at 8 dpi (Fig. 5j). These data suggested that Smyd3 in CD4 T cells supported a regulatory phenotype with changes in key cytokines to regulate RSV-induced immunopathology.

Fig. 5.

Smyd3 deletion in T cells exacerbated RSV immunopathology and CD4 T cells cytokine production in vivo during RSV infection. a Smyd3 expression in primary lymphoid organ: thymus, secondary lymphoid organ: spleen, and non-lymphoid tissue: lung from uninfected wild-type B6 mice were measured. N= 4. b Smyd3 expression in uninfected naive mice and i.t. RSV infected mice in lung at 4 dpi and 6 dpi were measured. N = 4. c CD4-specific Smyd3 knockout (Cre + Smyd3 cKO) and Cre− littermate control were intratracheally infected with RSV. The residual quantity of RSV surface glycoprotein (RSV-G) expression in lung were measured at 6 dpi and 8 dpi. N = 5~6. d Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining of formalin-fixed lung section from 8 dpi. Bar, 100 μm. ↑ indicates the detection of mucin. N = 5~6. e Percent of viable CD25 + Foxp3 + Treg in lung were gated and quantified at 8 dpi. f mLN cells were harvest at 8 dpi and re-stimulated with RSV for 48 h. IL-17A in the supernatant were measured. g mLN cells were collected at 8 dpi and re-stimulated with RSV for 48 h. IFN-γ in the supernatant were measured. h mLN cells were harvest at 8 dpi and re-stimulated with RSV for 48 h. IL-5 in the supernatant were measured. i mLN cells were harvest at 8 dpi and re-stimulated with RSV for 48 h. IL-10 in the supernatant were measured. Data represent mean ± SEM. Data were from one experiment representative of two experiments with four to six mice per group, with samples from each mouse processed and analyzed separately. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.0005; ND, not-detectable; NS, no significance (unpaired two-tailed t-test)

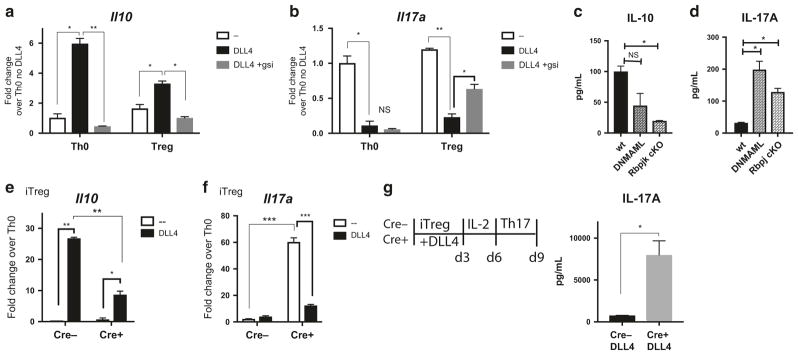

Notch and Smyd3 promote Il10 and inhibit Il17a in vitro during iTreg differentiation

To better understand if DLL4 and intracellular Notch regulated IL-10 and IL-17A in iTreg, naive CD4 T cells from wild-type B6 mice were skewed toward iTreg. DLL4 stimulation enhanced Il10 expression and inhibited Il17a at 24 h post iTreg differentiation, but the changes were reversed using a pan-Notch inhibitor of gamma-secretase (Fig. 6a, b). More specifically, naive CD4 T cells from Notch-inactivated DNMAML and canonical Notch-deleted Rbpj cKO mice secreted less IL-10 in the presence of DLL4 (Fig. 6c) and more IL-17A (Fig. 6d). To further understand whether DLL4 regulated Il10 and Il17a expression in a Smyd3-dependent manner, naive CD4 T cells from Cre + Smyd3 cKO and Cre-littermate control were activated in iTreg skewing conditions. DLL4-upregulated Il10 expression was partially Smyd3-dependent (Fig. 6e) with increased Il17a expression in primary iTreg differentiation in the absence of SMYD3 (Fig. 6f). Finally, we determined whether the presence of SMYD3 regulated the IL-17A associated plasticity from iTreg. After resting, DLL4-activated iTreg cultures were re-stimulated under Th17 skewing conditions. DLL4-exposed Smyd3 cKO secreted more IL-17A than Cre-control upon Th17 skewing and re-stimulation (Fig. 6g). These data indicate that DLL4 and Smyd3 cooperatively promote Il10 and inhibited Il17a.

Fig. 6.

Intracellular Notch and Smyd3 in CD4 T cells supported IL-10 production and inhibited IL-17A production in vitro. a Naive CD4 T cells were isolated and incubated with DMSO or 1 μm of gamma-secretase inhibitor (gsi) and proceed to Th0 or iTreg differentiation with or without DLL4 for 24 h. Il10 mRNA was detected. b After same procedure mentioned above, Il17a mRNA were detected. c Naive CD4 T cells from DNMAML mice and Rbpj cKO were activated with DLL4 for 48 h. IL-10 production in supernatant were measured. d Naive CD4 T cells from DNMAML mice and Rbpj cKO were differentiated to iTreg with DLL4 for 48 h. IL-17A production in supernatant were measured. e Naive CD4 T cells from Cre− control or Smyd3 cKO were differentiated to iTreg with or without DLL4 for 48 h. Il10 expression were detected. f After same procedure mentioned above, Il17a mRNA were detected. g Naive CD4 T cells from Cre-control or Cre + Smyd3 cKO were differentiated to iTreg with DLL4 stimulation for 72 h then rested in IL-2 10 ng/mL for another 72 h. Viable rested iTreg (5 × 105) were re-stimulated with Th17 skewing condition for 72 h. IL-17A in Th17 re-stimulation culture were measured. Data represent mean ± SEM. Data were from one experiment representative of two to three experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.0005; NS, no significance (unpaired two-tailed t-test)

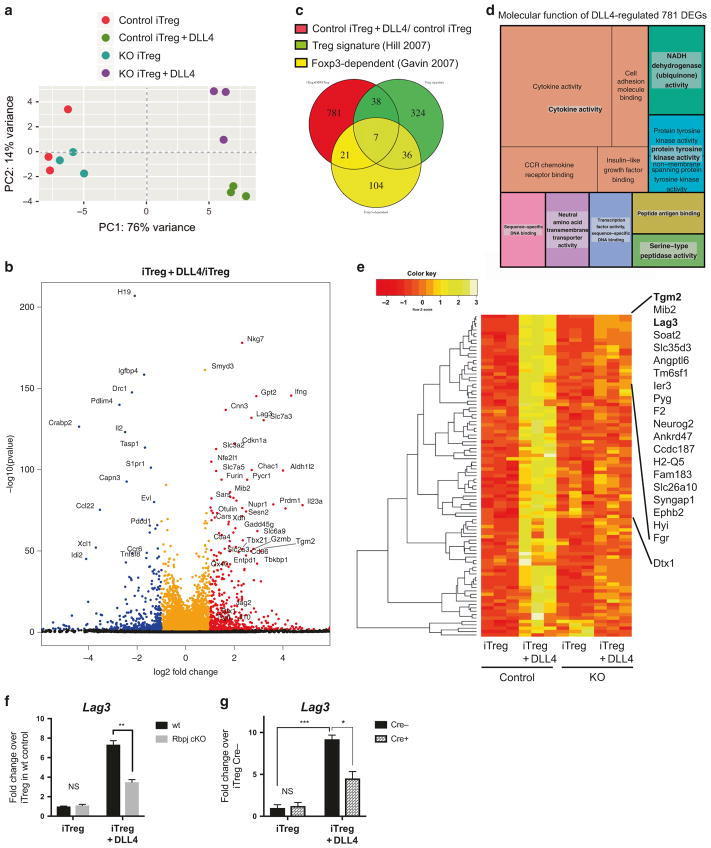

DLL4 and Smyd3 regulated gene expression profile in iTreg differentiation

In the above studies we identified that DLL4 increased Treg differentiation as well as promoted maintenance of the Treg phenotype in cooperation with a Smyd3 mechanism. Thus, although some of the Treg characteristics were enhanced by DLL4/Notch through a Smyd3-dependent mechanism, others were not. Therefore, we hypothesized that DLL4 and Smyd3 could differentially regulate additional genes during iTreg differentiation. To discover novel genes that are regulated by DLL4- and/or Smyd3-dependent pathways, we performed whole genome RNA-seq in iTreg differentiation (48 h after skewing). To distinguish the discrepancy between groups, PCA was performed in DESeq2. DLL4 stimulation introduced substantial variance (76%) in gene expression profile in wild-type mice and Smyd3 deletion changed the global gene expression on its own but was especially dramatic in the presence of DLL4 (Fig. 7a). These results demonstrated the interdependence on DLL4 and Smyd3. Next, we investigated what genes were differentially expressed by DLL4 stimulation using a likelihood ratio test in DESeq2. Some of the significantly upregulated (dots in red) or downregulated (dots in blue) differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were labeled in black text (Fig. 7b). Smyd3 was significantly upregulated by DLL4 along with a number of reported Treg functional genes, e.g., Ctla4, Gzmb, and Ox40 (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, Notch-related genes (Deltex1 (Dtx1), Notch3, and Jag2) and anti-inflammatory cytokine Il10 were also upregulated by DLL4 (Dtx1: 2.43 fold; Notch3: 1.98 fold; Jag2: 2.77 fold; and Il10: 1.42 fold) (Fig. 7b). Data also identified DEGs that were significantly upregulated (adjusted p-value < 0.05 and absolute fold change more than 2-fold) between wild-type iTreg+Dll4 and control iTreg. These differences were examined by comparing overlapping Treg signature genes58 and Foxp3-dependent genes.59 A Venn diagram illustrated the number of genes that were DLL4-stimulated DEGs, Treg signature genes, Foxp3-dependent genes, and the number of genes that were in two or even all three groups. Results indicate that only 5.3% of DLL4-stimulated DEGs were also Treg signature genes and 3.3 % of these DEGs were Foxp3-dependent (Fig. 7c). These results indicated that the majority of the DLL4-stimulated DEGs were neither Treg signatures nor Foxp3-dependent, and DLL4 stimulation introduced novel DEGs that may have a previously undefined role for Treg. To get a more informed understanding of the molecular function of DLL4 DEGs, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of the 781 DLL4 DEGs and plotted a treemap. The most significant GO term was cytokine activity with the highly significant p-value of 1.8 × 10−8. The p-value of each GO term was shown inversely to the area in treemap (Fig. 7d). Together, these data revealed that DLL4 not only regulated reported Treg signatures and Foxp3-dependent genes but also broadly impacted cytokine responses during differentiation. To further identify specific DEGs that were both regulated by DLL4 stimulation and Smyd3, we normalized the counts and did unsupervised cluster analysis with Pearson’s distribution of a heatmap showing the Z-score of DEGs. There were 95 DEGs that were significantly (padj < 0.05) regulated with a fold change more than 2 (log2FC > 1) in DLL4 stimulation and downregulated more than 1.51-fold (log2FC < − 0.6) in Smyd3 knockout (Fig. 7e). Heatmap analysis then clustered with rowMeans identified the top DEGs (Fig. 7e). Using this analysis, two Treg signature genes, Tgm2 and Lag3, were highly upregulated by DLL4 stimulation and downregulated in Smyd3 knockout (Fig. 7e). Interestingly, Notch target gene Dtx1 was also decreased in Smyd3-deficient Treg differentiation. We further confirmed that DLL4-upregulated Lag3 was canonical Notch-dependent using T cells from Rbpj cKO mice (Fig. 7f) and was also Smyd3-dependent (Fig. 7g) by quantitative PCR. These data uncovered a new set of DEGs, including a checkpoint inhibitory protein, Lag3, which were regulated by DLL4 and Smyd3 in iTreg differentiation. These results will help us further identify mechanisms that stabilize iTreg differentiation and function in future studies.

Fig. 7.

Smyd3 deletion changed gene expression profile in the presence of DLL4 stimulation during iTreg differentiation in vitro. a Principle component analysis of RNA-seq data sets of iTreg cells from Cre− control or Cre + Smyd3 cKO with or without DLL4 stimulation, assessed using the top 500 genes with the highest variance. Each symbol represented a single mouse. Each group have three biological triplicates. b Volcano plot showed the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in control iTreg + DLL4 over control iTreg; red dots indicated genes that were significantly (BH-adjusted p-value < 0.05) upregulated by DLL4 more than twofold (log2FoldChange > 1) and blue dots represents genes that were significantly downregulated by DLL4 more than twofold. The y axis represented the significance of the differential analysis. c Venn diagram demonstrated the overlap between current DLL4-regulated DEGs and published Treg signatures and Foxp3-dependent genes. d Gene Ontology (GO) of un-overlapped DLL4-regulated DEGs (781 genes). Treemap showed the significant GO term with False-discovery-rate (FDR)-adjusted global P-value < 0.05. P-value inversely proportional to area for each GO term. e Normalized expression of all the DEGs that were significantly upregulated by DLL4 stimulation for more than 2.00-fold, and downregulated more than 1.51-fold by Smyd3 deletion. Heatmap presented Z-score in a dendrogram clustered by Pearson’s distribution and ranked based on rowMeans. Top 20 DEGs and Deltex1 were indicated. f Naive CD4 T cells from wild-type control or Rbpj cKO were differentiated to iTreg with or without DLL4 for 24 h. Lag3 expression were detected. g Naive CD4 T cells from Cre− control or Smyd3 cKO were differentiated to iTreg with or without DLL4 for 48 h. Lag3 expression were detected

DISCUSSION

Infection and inflammation-experienced Treg cells acquired changes in chromatin modifications correlated with gene expression profiles60. Chromatin modifications contribute to long-term responses of Treg cell differentiation, subset specification, and cytokine-producing potential, such as histone 3 lysine 4 methylation and its methyltransferase.61 Previous studies have importantly demonstrated that methylation of DNA can regulate Foxp3 expression and Treg cell differentiation and stability coordinated with chromatin modifications.17,21,22,36,50 Our labs and others have previously identified that Notch ligand DLL4 was induced during pulmonary infection and inflammation to enhance Treg differentiation. 34,35 Here we report one specific methyltransferase, SMYD3, 24,62 which was directly regulated by DLL4/Notch. The present study demonstrates several novel findings and concepts: (1) Epigenetic enzymes are a part of the mechanism by which RSV infection could modify CD4 T cells lineage specification, including Treg differentiation; (2) DLL4/Canonical Notch signaling directly facilitates SMYD3 expression in vitro and in vivo during RSV infection; (3) DLL4 stimulation changed H3K4me3 gene activation marks around Foxp3 functional promoters and enhancers that are SMYD3-dependent; and (4) DLL4 confers cytokine expression changes in Treg through SMYD3 with each regulating additional gene expression. Together, our data highlight the broad impact of DLL4/Notch in Foxp3 + Treg and identified a novel mechanism through methyltransferase SMYD3-mediated histone modification.

SMYD3 was previously reported to be regulated in cancer cells by estrogen receptor, androgen receptor, and TGF-β25,63–65. Here we identify another novel regulatory signal, Notch. It is noteworthy that DLL4 stimulation and intracellular Notch activation alone does not activate Smyd3 expression in Th0, suggesting that iTreg environmental cues including TGF-β1 are required. One explanation may be the activation of Foxp3 itself through the individual transcription factors Smad3 (TGFβ) and RBP-Jκ (Notch) that together bind to Foxp3 promoter in order to optimally activate gene transcription.33 Given that Smad3 also binds to the Smyd3 promoter25 and the present study also showed RBP-Jκ binding on the Smyd3 promoter, the data suggested that TGF-β signaling and canonical Notch cooperatively facilitate Smyd3 expression as well as Foxp3 activation.

Treg-mediated suppression is tailored to fit in specific tissue and inflammatory settings with different regulatory mechanisms. For example, Foxp3/T-bet could suppress Th1 effector responses,66 Foxp3/IRF4 suppresses Th2,67 and Foxp3/STAT3 suppresses Th17.68 However, little is known about the direct role of Foxp3 for Treg cell specification. The RNA-seq results showed that Ifng was upregulated more than 16-fold by DLL4 in iTreg, suggesting that DLL4 stimulation provided a Th1-like profile in iTreg differentiation similar to previous observations in Th1 differentiation.69–71 Here we found that DLL4 inhibition decreased Ifng in Foxp3-EGFP + Treg but increased Il17a in Foxp3-EGFP +. These data in vitro and in vivo suggested a novel paradigm that DLL4 may favor a Th1-like suppressive program in Treg. It would be intriguing to further investigate whether DLL4 regulated effector function of T-bet + Foxp3 + Th1-like Treg. This program may have a significant advantage in a viral infection, where IFN-mediated programs are required for viral clearance yet Treg functions control more pathogenic Th2 and Th17 responses necessary to protect tissue function.

Besides Foxp3 + Treg, the RNA-seq results suggested that DLL4 stimulation promote a substantial amount of DEGs (819, 96.7% of total DLL4 DEGs) that are not Foxp3-dependent. The RNA-seq result further showed (at least) two other interesting candidates that were promoted by both DLL4 and Smyd3, Tgm2 and Lag3. Tgm2 encodes the TG2 protein that covalently crosslinks latent TGF-β1-binding protein and controls TGF-β1 maturation and activity72,73 and therefore increases TGF-β1 mRNA levels.74 In cancer cells, TGF-β-induced Tgm2 promotes epithelial to mesenchymal transition.75,76 These latter studies suggest that DLL4/Notch and Smyd3 may reinforce the positive feedback loop of TGF-β signaling to facilitate iTreg differentiation. Another Treg signature gene that was shown to be DLL4 and Smyd3 dependent was Lag3. Lag3 is required for maximal regulatory function of CD25 + Foxp3 + Treg 77 and a biomarker for IL-10 producing TR1 cells that enhances suppressor function to ameliorate mucosal inflammation and autoimmunity.78,79 The present study also found that both DLL4 and SMYD3 supported IL-10 production and Lag3 expression, together suggesting that DLL4 and SMYD3 may promote TR1 related function to support an overall regulatory environment along with Foxp3 + Treg. Given the number of different gene expression profiles,79 stability,50 and suppression function between in vitro derived iTreg and in vivo iTreg 50,79, it will be exciting to further investigate the role of DLL4/Notch and Smyd3 for specific genes such as Tgm2 and Lag3 regulation from in vivo iTreg. No doubt these data outline a complex interaction of Notch activation with epigenetic regulation for stabilization of Treg cells, as well as possibly other T-cell subsets. As Lag3 is a checkpoint inhibitor now targeted in cancer immunotherapy trials, it will also be exciting to investigate the efficacy of targeting Smyd3 in Notch-active cancers, including lymphoma/leukemias that have Notch activation signals.

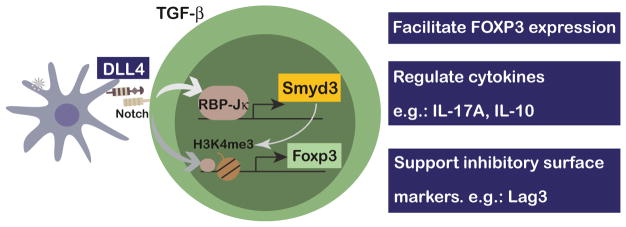

Together, these studies offer new and exciting data that demonstrate the mechanism by which Notch promotes iTreg cell differentiation and stability through a SMYD3-mediated epigenetic mechanisms to maintain Foxp3 Treg, their cytokine profile, and other regulatory signatures, such as Lag3 (Fig. 8). Overall, the research highlights DLL4-SMYD3 as potential target for manipulating iTreg during viral infection immunopathology, as well as other diseases.

Fig. 8.

Schematic summary of how DLL4 promotes Smyd3 expression to confer regulatory features of CD4 T cells

Acknowledgments

HT, DDN, MAS, and NWL designed the experiments. HT, AJR, DDN, and CM performed experiments. HT and NWL did data analysis and wrote the manuscript. We thank Dr. Matthew A Schaller and Consulting for Statistics, Computation, and Analytical Research (CSCAR) for consultations; Ivan Maillard for helpful discussions; Susan Morris, Lisa Riggs Johnson, for technical assistance; and Dr. Judith Connett for editing the manuscript. The manuscript was supported in part by NIH grant AI036302 (NWL).

Footnotes

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41385-018-0052-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Curotto de Lafaille MA, et al. Adaptive Foxp3+ regulatory T cell-dependent and -independent control of allergic inflammation. Immunity. 2008;29:114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang H, Ma Y, Dawicki W, Zhang X, Gordon JR. Comparison of induced versus natural regulatory T cells of the same TCR specificity for induction of tolerance to an environmental antigen. J Immunol. 2013;191:1136–1143. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Josefowicz SZ, et al. Extrathymically generated regulatory T cells control mucosal TH2 inflammation. Nature. 2012;482:395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature10772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durant LR, et al. Regulatory T cells prevent Th2 immune responses and pulmonary eosinophilia during respiratory syncytial virus infection in mice. J Virol. 2013;87:10946–10954. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01295-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loebbermann J, et al. Regulatory T cells expressing granzyme B play a critical role in controlling lung inflammation during acute viral infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:161–172. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fulton RB, Meyerholz DK, Varga SM. Foxp3+ CD4 regulatory T cells limit pulmonary immunopathology by modulating the CD8 T cell response during respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Immunol. 2010;185:2382–2392. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W, et al. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25-naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–1886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tone Y, et al. Smad3 and NFAT cooperate to induce Foxp3 expression through its enhancer. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:194–202. doi: 10.1038/ni1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubtsov YP, et al. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity. 2008;28:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maynard CL, et al. Regulatory T cells expressing interleukin 10 develop from Foxp3+ and Foxp3-precursor cells in the absence of interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:931–941. doi: 10.1038/ni1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss KA, Christiaansen AF, Fulton RB, Meyerholz DK, Varga SM. Multiple CD4+ T cell subsets produce immunomodulatory IL-10 during respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Immunol. 2011;187:3145–3154. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loebbermann J, et al. IL-10 regulates viral lung immunopathology during acute respiratory syncytial virus infection in mice. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massoud AH, et al. An asthma-associated IL4R variant exacerbates airway inflammation by promoting conversion of regulatory T cells to TH17-like cells. Nat Med. 2016;22:1013–1022. doi: 10.1038/nm.4147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng Y, et al. Role of conserved non-coding DNA elements in the Foxp3 gene in regulatory T-cell fate. Nature. 2010;463:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature08750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohkura N, Kitagawa Y, Sakaguchi S. Development and maintenance of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2013;38:414–423. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson CB, Rowell E, Sekimata M. Epigenetic control of T-helper-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:91–105. doi: 10.1038/nri2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei G, et al. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyao T, et al. Plasticity of Foxp3(+) T cells reflects promiscuous Foxp3 expression in conventional T cells but not reprogramming of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2012;36:262–275. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou X, et al. Foxp3 instability leads to the generation of pathogenic memory T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1000–1007. doi: 10.1038/ni.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lal G, et al. Epigenetic regulation of Foxp3 expression in regulatory T cells by DNA methylation. J Immunol. 2009;182:259–273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yue X, et al. Control of Foxp3 stability through modulation of TET activity. J Exp Med. 2016;213:377–397. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DuPage M, et al. The chromatin-modifying enzyme Ezh2 is critical for the maintenance of regulatory T cell identity after activation. Immunity. 2015;42:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arvey A, et al. Inflammation-induced repression of chromatin bound by the transcription factor Foxp3 in regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:580–587. doi: 10.1038/ni.2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamamoto R, et al. SMYD3 encodes a histone methyltransferase involved in the proliferation of cancer cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:731–740. doi: 10.1038/ncb1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagata DE, et al. Epigenetic control of Foxp3 by SMYD3 H3K4 histone methyltransferase controls iTreg development and regulates pathogenic T-cell responses during pulmonary viral infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:1131–1143. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandy AR, Maillard I. Notch signaling in the hematopoietic system. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:1383–1398. doi: 10.1517/14712590903260777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maillard I, Adler SH, Pear WS. Notch and the immune system. Immunity. 2003;19:781–791. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radtke F, Fasnacht N, Macdonald HR. Notch signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2010;32:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailis W, et al. Notch simultaneously orchestrates multiple helper T cell programs independently of cytokine signals. Immunity. 2013;39:148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang TC, et al. Notch directly regulates Gata3 expression during T helper 2 cell differentiation. Immunity. 2007;27:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukherjee S, Schaller MA, Neupane R, Kunkel SL, Lukacs NW. Regulation of T cell activation by Notch ligand, DLL4, promotes IL-17 production and Rorc activation. J Immunol. 2009;182:7381–7388. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elyaman W, et al. Notch receptors and Smad3 signaling cooperate in the induction of interleukin-9-producing T cells. Immunity. 2012;36:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samon JB, et al. Notch1 and TGFbeta1 cooperatively regulate Foxp3 expression and the maintenance of peripheral regulatory T cells. Blood. 2008;112:1813–1821. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ting HA, et al. Notch ligand delta-like 4 promotes regulatory T cell identity in pulmonary viral infection. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. 2017;198:1492–1502. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang MT, et al. Notch ligand DLL4 alleviates allergic airway inflammation via induction of a homeostatic regulatory pathway. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43535. doi: 10.1038/srep43535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charbonnier LM, Wang S, Georgiev P, Sefik E, Chatila TA. Control of peripheral tolerance by regulatory T cell-intrinsic Notch signaling. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:1162–1173. doi: 10.1038/ni.3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tu L, et al. Notch signaling is an important regulator of type 2 immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1037–1042. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maillard I, et al. Mastermind critically regulates Notch-mediated lymphoid cell fate decisions. Blood. 2004;104:1696–1702. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandy AR, et al. Notch signaling regulates T cell accumulation and function in the central nervous system during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2013;191:1606–1613. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lukacs NW, et al. Differential immune responses and pulmonary pathophysiology are induced by two different strains of respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:977–986. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaller MA, et al. Notch ligand Delta-like 4 regulates disease pathogenesis during respiratory viral infections by modulating Th2 cytokines. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2925–2934. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller AL, Bowlin TL, Lukacs NW. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced chemokine production: linking viral replication to chemokine production in vitro and in vivo. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1419–1430. doi: 10.1086/382958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amsen D, et al. Instruction of distinct CD4 T helper cell fates by different notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells. Cell. 2004;117:515–526. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wen H, Dou Y, Hogaboam CM, Kunkel SL. Epigenetic regulation of dendritic cell-derived interleukin-12 facilitates immunosuppression after a severe innate immune response. Blood. 2008;111:1797–1804. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-106443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collison LW, Vignali DAA. In vitro Treg suppression assays. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;707:21–37. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-979-6_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq--a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Supek F, Bošnjak M, Škunca N, Šmuc T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohkura N, et al. T cell receptor stimulation-induced epigenetic changes and Foxp3 expression are independent and complementary events required for Treg cell development. Immunity. 2012;37:785–799. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou L, Chong MMW, Littman DR. Plasticity of CD4+ T cell lineage differentiation. Immunity. 2009;30:646–655. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dillon SC, Zhang X, Trievel RC, Cheng X. The SET-domain protein super-family: protein lysine methyltransferases. Genome Biol. 2005;6:227. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-8-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Castel D, et al. Dynamic binding of RBPJ is determined by Notch signaling status. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1059–1071. doi: 10.1101/gad.211912.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borchers AT, Chang C, Gershwin ME, Gershwin LJ. Respiratory syncytial virus--a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45:331–379. doi: 10.1007/s12016-013-8368-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hashimoto K, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in the absence of STAT 1 results in airway dysfunction, airway mucus, and augmented IL-17 levels. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mukherjee S, et al. IL-17-induced pulmonary pathogenesis during respiratory viral infection and exacerbation of allergic disease. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stier MT, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection activates IL-13-producing group 2 innate lymphoid cells through thymic stromal lymphopoietin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:814–824.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hill JA, et al. Foxp3 transcription-factor-dependent and -independent regulation of the regulatory T cell transcriptional signature. Immunity. 2007;27:786–800. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gavin MA, et al. Foxp3-dependent programme of regulatory T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2007;445:771–775. doi: 10.1038/nature05543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Veeken J, et al. Memory of inflammation in regulatory T cells. Cell. 2016;166:977–990. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Placek K, et al. MLL4 prepares the enhancer landscape for Foxp3 induction via chromatin looping. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:1035–1045. doi: 10.1038/ni.3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mazur PK, et al. SMYD3 links lysine methylation of MAP3K2 to Ras-driven cancer. Nature. 2014;510:283–287. doi: 10.1038/nature13320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu H, et al. Elevated levels of SET and MYND domain-containing protein 3 are correlated with overexpression of transforming growth factor-β1 in gastric cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:579–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim H, et al. Requirement of histone methyltransferase SMYD3 for estrogen receptor-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19867–19877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu C, et al. SMYD3 as an oncogenic driver in prostate cancer by stimulation of androgen receptor transcription. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1719–1728. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koch MA, et al. The transcription factor T-bet controls regulatory T cell homeostasis and function during type 1 inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:595–602. doi: 10.1038/ni.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zheng Y, et al. Regulatory T-cell suppressor program co-opts transcription factor IRF4 to control T(H)2 responses. Nature. 2009;458:351–356. doi: 10.1038/nature07674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chaudhry A, et al. CD4+ regulatory T cells control TH17 responses in a Stat3-dependent manner. Science. 2009;326:986–991. doi: 10.1126/science.1172702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jankovic D, et al. In the absence of IL-12, CD4(+) T cell responses to intracellular pathogens fail to default to a Th2 pattern and are host protective in an IL-10(−/−) setting. Immunity. 2002;16:429–439. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Skokos D, Nussenzweig MC. CD8-DCs induce IL-12-independent Th1 differentiation through Delta 4 Notch-like ligand in response to bacterial LPS. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1525–1531. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kojima S, Nara K, Rifkin DB. Requirement for transglutaminase in the activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta in bovine endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:439–448. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang Z, Griffin M. TG2, a novel extracellular protein with multiple functions. Amino Acids. 2012;42:939–949. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-1008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Telci D, Collighan RJ, Basaga H, Griffin M. Increased TG2 expression can result in induction of transforming growth factor beta1, causing increased synthesis and deposition of matrix proteins, which can be regulated by nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29547–29558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cao L, et al. Tissue transglutaminase links TGF-β, epithelial to mesenchymal transition and a stem cell phenotype in ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31:2521–2534. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shao M, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and ovarian tumor progression induced by tissue transglutaminase. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9192–9201. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang CT, et al. Role of LAG-3 in regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2004;21:503–513. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Do JS, et al. An IL-27/Lag3 axis enhances Foxp3+ regulatory T cell-suppressive function and therapeutic efficacy. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:137–145. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sega EI, et al. Role of lymphocyte activation gene-3 (Lag-3) in conventional and regulatory T cell function in allogeneic transplantation. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e86551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Haribhai D, et al. A requisite role for induced regulatory T cells in tolerance based on expanding antigen receptor diversity. Immunity. 2011;35:109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]