Key Points

DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs belong to a distinct subset of ALCLs lacking activated STAT3.

DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs have a unique molecular signature characterized by DNA hypomethylation and an immunogenic phenotype.

Abstract

Anaplastic large cell lymphomas (ALCLs) are CD30-positive T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas broadly segregated into ALK-positive and ALK-negative types. Although ALK-positive ALCLs consistently bear rearrangements of the ALK tyrosine kinase gene, ALK-negative ALCLs are clinically and genetically heterogeneous. About 30% of ALK-negative ALCLs have rearrangements of DUSP22 and have excellent long-term outcomes with standard therapy. To better understand this group of tumors, we evaluated their molecular signature using gene expression profiling. DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs belonged to a distinct subset of ALCLs that lacked expression of genes associated with JAK-STAT3 signaling, a pathway contributing to growth in the majority of ALCLs. Reverse-phase protein array and immunohistochemical studies confirmed the lack of activated STAT3 in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs. DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs also overexpressed immunogenic cancer-testis antigen (CTA) genes and showed marked DNA hypomethylation by reduced representation bisulfate sequencing and DNA methylation arrays. Pharmacologic DNA demethylation in ALCL cells recapitulated the overexpression of CTAs and other DUSP22 signature genes. In addition, DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs minimally expressed PD-L1 compared with other ALCLs, but showed high expression of the costimulatory gene CD58 and HLA class II. Taken together, these findings indicate that DUSP22 rearrangements define a molecularly distinct subgroup of ALCLs, and that immunogenic cues related to antigenicity, costimulatory molecule expression, and inactivity of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint likely contribute to their favorable prognosis. More aggressive ALCLs might be pharmacologically reprogrammed to a DUSP22-like immunogenic molecular signature through the use of demethylating agents and/or immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Anaplastic large cell lymphomas (ALCLs) make up a group of T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas that share common pathologic features but demonstrate marked heterogeneity in clinical presentation, genetic features, and outcomes.1-3 All ALCLs express the lymphocyte activation marker CD30 and contain at least a subpopulation of cells with characteristic cytological features, designated hallmark cells.4 The World Health Organization (WHO) subclassifies ALCLs according to clinical presentation and the presence or absence of ALK tyrosine kinase gene rearrangements encoding oncogenic ALK fusion proteins.5,6 Among systemic ALCLs, ALK-positive cases have overall survival (OS) rates superior to those of ALK-negative cases.7-9 Primary cutaneous ALCL is a separate entity with pathological features similar to ALK-negative ALCL and presentation in the skin, although with distinctly more favorable clinical outcomes than systemic ALK-negative ALCL10,11; rare ALK-positive ALCLs arising in the skin also have been reported.12 Finally, breast implant-associated ALCL is considered a new provisional entity by the WHO.13,14

Although ALK rearrangements drive lymphomagenesis by a variety of extensively studied mechanisms,15-18 the molecular pathogenesis of ALK-negative ALCL remains poorly understood. Our group has identified and characterized recurrent rearrangements of the DUSP22-IRF4 locus on 6p25.3 in ALK-negative ALCLs.9,19-22 DUSP22 rearrangements are seen in 28% to 30% of both systemic and cutaneous ALK-negative ALCLs and are associated with downregulation of DUSP22, a tumor suppressor gene encoding dual-specificity phosphatase-22, which inhibits T-cell receptor signaling and growth and promotes apoptosis in experimental models.9,20,21,23-26 DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs have an excellent prognosis, with a 5-year OS rate of 90%, similar to ALK-positive ALCL.9 These outcomes are significantly better than both ALCLs with TP63 rearrangements (5-year OS, 17%) and ALCLs lacking rearrangements of ALK, DUSP22, and TP63 (“triple-negative” ALCLs; 5-year OS, 42%),9,27 a finding recently validated in independent cohorts of systemic ALCL.28,29

Although the prognostic significance of DUSP22 rearrangements in ALCL is discussed in the WHO lymphoma classification5 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines,30 the molecular features of these tumors remain largely uncharacterized. A major oncogenic function of ALK is the activation of STAT3, which transcriptionally regulates ALCL-associated genes such as TNFRSF8 (CD30), GRZB (granzyme B), and IL2RA (interleukin 2 [IL-2] receptor-α/CD25).31-33 Notably, Crescenzo et al have shown that a subset of systemic and cutaneous ALK-negative ALCLs activate STAT3 through convergent events involving non-ALK tyrosine kinase genes, including rearrangements of ROS1 and TYK2 and mutations of JAK1 and STAT3 itself.33 In addition, we discovered recurrent rearrangements of the FRK tyrosine kinase gene that lead to an ALK-like gene expression signature and STAT3 activation in ALK-negative ALCLs.34 Loss of DUSP22 phosphatase activity in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs might recapitulate the downstream effects of ALK and non-ALK tyrosine kinase activity in other ALCLs; alternatively, DUSP22 rearrangements might identify a distinct ALCL subtype with novel biology.35 However, the relationship of DUSP22 rearrangements to STAT3 activation in ALCL is unknown, as are the molecular features underlying the favorable prognosis associated with these rearrangements. Understanding these features might not only lead to improved risk-adapted therapies for DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs but also uncover opportunities to pharmacologically reprogram aggressive ALCLs into more indolent, “DUSP22-like” disease. Therefore, we sought to characterize the molecular profile of DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs.

Materials and methods

Patients and specimens

Frozen tumor tissue specimens from 31 ALCLs (8 ALK positive, 16 ALK negative, and 7 primary cutaneous) constituted a discovery set (male:female, 20:11; mean age, 51 years; supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site).34 Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues from an independent set of ALCLs were analyzed in validation studies. Subsets of this group were used in FFPE validation experiments based on availability of tissue sections, DNA, and RNA; these subsets are detailed in supplemental Table 2. Cases were re-reviewed and diagnosed using 2016 WHO criteria.5,6,10 DUSP22 rearrangements were assessed by fluorescence in situ hybridization, as published.9,20,28 The study protocol was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Gene expression profiling

RNA was extracted from the 31 frozen ALCL samples and analyzed using Affymetrix Human U133 Plus 2.0 arrays, as published.34 CEL files were processed to extract perfect match probes, and raw intensities were normalized using robust multiarray average with background correction. Normalized intensities were log2-transformed before further analysis.

For unsupervised analysis, probes expressed in at least 4 samples that showed a coefficient of variation of at least 50% across the sample set were selected. Samples were clustered according to the Kendall rank correlation coefficient of these probes. The probability that cases of similar type clustered together was assessed by computing the number of similar and dissimilar neighbors for each sample in the clustering solution and calculating a 2-sided P value, using a Fisher’s exact 1×2 test configured to assume a uniform distribution as the null hypothesis.

Supervised analysis was performed to identify gene expression signatures associated with genetic subtypes by comparing expression of genes between samples belonging to each pair of subtypes with an analysis of variance test. P values were corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Genes overexpressed in samples of a single subtype when compared with the rest of the subtypes with an average log2 fold change of at least 5.0 and an average q-value of 0.05 or less were considered associated with that subtype. Array data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus, accession number GSE118238.

Additional methods are described in supplemental Material.

Results

DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs belong to a unique molecular subgroup distinct from ALK-positive ALCLs

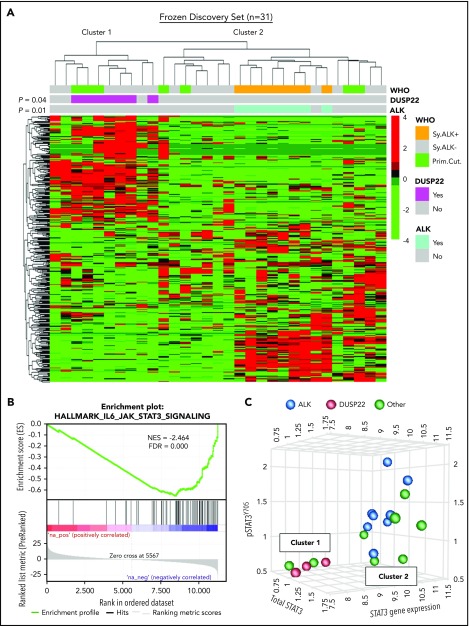

DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs have low expression of the DUSP22 phosphatase and favorable clinical outcomes similar to those of ALK-positive ALCLs.9,28,29 Because ALK fusion proteins and loss of DUSP22 both activate STAT3,31,32,36 we hypothesized that DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs might have a molecular profile similar to that of ALK-positive ALCLs. We performed unsupervised clustering of previously obtained34 gene expression data from 31 frozen ALCLs to evaluate agnostic distinctions among cases without a priori subtyping. This analysis identified 2 main clusters of cases containing 10 and 21 cases, respectively (Figure 1A). Notably, this highest branch point did not recapitulate the current WHO classification of ALCL; that is, it did not distinguish systemic from cutaneous cases, nor ALK-negative from ALK-positive cases, although the latter clustered together within a distinct subcluster in cluster 2 (P = .01). Cluster 1 contained all of the DUSP22-rearranged cases, which clustered together (P = .04) and comprised 7 of 10 cases in this cluster. ALK-negative ALCLs without DUSP22 rearrangements were present in both clusters. Three cases had TP63 rearrangements (1 in cluster 1 and 2 in cluster 2). These did not significantly cluster together (P = .69; not shown), and because of the small number of cases and their presence in both clusters, TP63-rearranged ALCLs were not considered separately in the remaining analyses. Cutaneous ALCLs were present in both clusters and did not significantly cluster with each other (P = .29). Taken together, these data indicate that DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs and ALK-positive ALCL belong to distinct molecular subgroups.

Figure 1.

ALCLs with DUSP22 rearrangements belong to a unique cluster of ALCLs. (A) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of gene expression data from 31 frozen ALCL samples shows that DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs segregate independently from ALK-positive ALCLs and are entirely contained within 1 of 2 main clusters (cluster 1). Genes shown were selected on the basis of coefficient of variation of at least 50% and expression in at least 4 samples across the entire data set, agnostic to subtype or cluster. P values reflect the probability that cases of similar type cluster together (Fisher exact test). WHO, WHO subtype. Primary cutaneous (Prim.Cut.) ALCLs did not cluster together significantly (P = .29). (B) Cluster 1 containing all DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs shows depletion of IL-6-JAK-STAT3-associated genes. (C) ALCLs in cluster 1 with low STAT3 gene expression also show low total STAT3 protein and low pSTAT3Y705 by reverse phase protein array. Genetic subtypes (ALK, DUSP22, or other ALK-negative) are indicated. The 3 cases indicated with DUSP22 rearrangements were systemic ALK-negative ALCLs and correspond to cases 1, 10, and 29 in supplemental Table 2.

DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs lack activated STAT3

Having found that ALCLs agnostically clustered into distinct molecular subgroups, we used gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to identify candidate biological features underlying this segregation (supplemental Tables 3 and 4). Notably, the top gene set negatively associated with cluster 1, containing all DUSP22-rearranged cases, reflected significant depletion of genes in the IL-6-JAK-STAT3 signaling pathway (normalized enrichment score [NES], −2.464; false discovery rate q-value [FDR], 0.000; Figure 1B). Although we had expected low DUSP22 expression to enhance STAT3 activation,37 expression of STAT3 itself was diminished 3.4-fold in DUSP22-rearranged cases (supplemental Figure 1), suggesting that reduced total STAT3 was available for phosphorylation. Expression of known STAT3 target genes such as GRZB and IL2RA also was low in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs. Other gene sets negatively associated with cluster 1 mainly related to inflammation, whereas positively associated gene sets related to cell cycle and mRNA processing. Although these latter findings merit further investigation, we focused on the unanticipated finding that DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs appeared to lack JAK-STAT3 signaling.

To assess the expression of STAT3 at the protein and phosphoprotein level, we evaluated reverse-phase protein arrays of protein lysates available in 19/31 cases in the frozen discovery set for total STAT3 and pSTAT3Y705. In addition to having reduced STAT3 gene expression, DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs and other ALK-negative ALCLs from cluster 1 had low levels of both total STAT3 protein and pSTAT3Y705; normalized expression of pSTAT3 (mean ± standard deviation, arbitrary units) was 1.36 ± 0.41, 0.57 ± 0.03, and 0.95 ± 0.39 for the ALK, DUSP22, and other ALCL subsets, respectively (P = .0095, Kruskal-Wallis test; Figure 1C). Because this small number of cases precluded definitive conclusions, we performed immunohistochemistry for pSTAT3Y705 in an independent validation set of 334 FFPE ALCLs (supplemental Table 2). Using the published cutoff of 20% or more nuclear staining,38 90.8% of ALK-positive ALCLs and 53.0% of ALK-negative ALCLs were positive for pSTAT3 (P < .0001, 2-tail Fisher’s exact test), 14.1% of ALCLs with DUSP22 rearrangements and 75.9% of ALCLs without DUSP22 rearrangements were positive for pSTAT3 (P < .0001; Figure 2A). Expressing percentage of positive tumor cells as mean ± standard deviation, DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs showed minimal pSTAT3 expression (8.1% ± 20.2%) compared with ALK-positive ALCLs (69.0% ± 27.6%; P < .0001, Wilcoxon test) or ALK-negative ALCLs without DUSP22 rearrangements (42.1% ± 34.4%; P < .0001; Figure 2B). The association between DUSP22 rearrangement and low pSTAT3 expression was seen for both systemic ALK-negative ALCL and primary cutaneous ALK-negative ALCL (both, P < .0001; supplemental Figure 2), whereas there was no significant difference in expression of pSTAT3 between systemic and cutaneous ALK-negative ALCLs of the same genetic subtype. These data indicate that pSTAT3 expression is associated with genetic subtype, but not systemic vs cutaneous presentation of ALCL.

Figure 2.

ALCLs with DUSP22 rearrangements lack phosphorylated STAT3 protein. (A) Immunohistochemistry for pSTAT3Y705 in ALK-positive ALCL and DUSP22-rearranged ALCL; note internal positive control staining in endothelial cells in the bottom image. Original magnification, ×400. (B) Results of pSTAT3Y705 staining in 334 FFPE ALCLs independent from the frozen discovery set, stratified by genetic subtype. (C) Prognostic significance of DUSP22 rearrangement in 59 systemic ALK-negative ALCLs that are negative for pSTAT3Y705 by immunohistochemistry (<20% of tumor cells with nuclear staining; log-rank test; see also supplemental Tables 6 and 7).

Because activated STAT3 is a critical driver of ALCL cell growth,32,33 we examined whether the relatively favorable prognosis in systemic DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs might be attributable to their lack of activated STAT3. We first asked whether systemic ALK-negative ALCLs in cluster 1 had uniformly favorable outcomes, regardless of the presence of DUSP22 rearrangements. We found, however, that the 3 ALCLs lacking DUSP22 rearrangements in cluster 1 demonstrated aggressive clinical behavior, dying of disease 1 month, 1 month, and 38 months after diagnosis, respectively (supplemental Table 5). Therefore, we studied 105 systemic patients with ALK-negative ALCL with available follow-up data, summarized in supplemental Table 6, to dissect the relative contributions of DUSP22 rearrangement and pSTAT3 expression to OS. Among ALCLs negative for pSTAT3Y705 by immunohistochemistry (n = 59), the presence of DUSP22 rearrangement (n = 27) remained a significant prognostic factor, with 5-year OS at 88% compared with 20% in systemic ALK-negative ALCLs without DUSP22 rearrangements (n = 32; P < .0001, log-rank test; Figure 2C). Furthermore, multivariate analysis of all 105 cases showed that in addition to age and international prognostic index score, the presence of DUSP22 rearrangement retained prognostic significance in systemic ALK-negative ALCL (hazard ratio, 0.14; 95% confidence interval, 0.04-0.41; P = .0001; supplemental Table 7). However, pSTAT3 expression was not significantly prognostic in either univariate or multivariate analysis. These findings indicate that the favorable prognosis observed in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs is not attributable solely to the lack of activated STAT3.

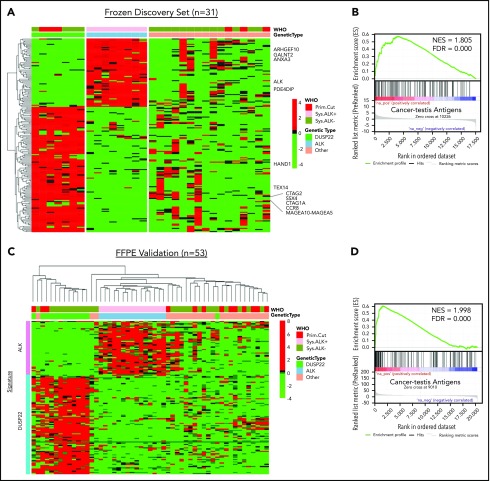

DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs have a unique molecular profile characterized by upregulation of cancer-testis antigen genes

Because the lack of activated STAT3 was insufficient to explain the favorable prognosis in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs and was also observed in a subset of ALK-negative ALCLs without DUSP22 rearrangements, we next sought to identify molecular characteristics more specific to the DUSP22-rearranged subgroup. Because DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs clustered separately from ALK-positive ALCLs by unsupervised analysis, we performed supervised analysis to examine in greater detail the genes differentially expressed among genetic subgroups. Although gene signatures could be derived for ALK-positive ALCL and DUSP22-rearranged ALCL (Figure 3A; supplemental Table 8 and 9), no unique signature could be derived for the remaining ALK-negative ALCLs, consistent with data indicating further genetic heterogeneity within this group, including alterations in TP63, ERBB4, ROS1, TYK2, FRK, VAV1, and other genes.27,33,34,39-41

Figure 3.

ALCLs with DUSP22 rearrangements overexpress CTA genes. (A) Affymetrix microarray analysis of 31 ALCLs in the frozen discovery set shows that DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs have a unique set of overexpressed genes, including multiple CTA genes and other genes regulated by methylation such as HAND1. WHO, WHO subtype. (B) CTA genes are significantly enriched in cases with DUSP22 rearrangements by GSEA. (C) Analysis of FFPE RNAseq gene expression data from an independent set of 53 ALCLs validates the DUSP22 and ALK molecular signatures shown in A. DUSP22 cases clustered together significantly (P = .0014), as did ALK cases (P < .0001). (D) GSEA of FFPE RNAseq data validates the enrichment of CTA genes in cases with DUSP22 rearrangements.

The ALK signature from this analysis yielded ALK and other ALK-associated genes, as we and others previously published.34,42,43 Genes in the DUSP22 signature included CCR8, as previously shown44; HAND1, a methylation-sensitive transcription factor gene critical in cardiac morphogenesis45; and notably, a group of genes in the cancer-testis antigen (CTA) family such as CTAG1A, CTAG2, MAGEA10-MAGEA5, and SSX4. CTAs are proteins expressed predominantly in the testis and other immune-privileged sites, but also in melanomas and other cancers, where their expression has been associated with DNA hypomethylation and induction of antitumor immune responses.46 GSEA, using a gene set containing all CTA genes in the CTpedia database, showed that DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs were significantly enriched for expression of CTA genes (NES, 1.805; FDR, 0.000; Figure 3B).

To validate the DUSP22 and ALK signatures identified in the frozen discovery set, we performed RNAseq on FFPE tissue samples from an independent validation set of 53 ALCLs (supplemental Table 2). Clustering based on the DUSP22 and ALK signature genes closely recapitulated the segregation of ALCLs into genetic subtypes (ALK, DUSP22, and other ALCLs; Figure 3C). Cases within the ALK and DUSP22 groups each clustered together significantly (P < .0001 and P = .0014, respectively). The highest branch point on the resulting dendrogram broadly segregated ALCLs with DUSP22 rearrangements from those without DUSP22 rearrangements. Interestingly, the single case without DUSP22 rearrangement in this cluster was an ALK-negative ALCL involving the testis; this segregation likely resulted because of testis-expressed genes in the DUSP22 signature. GSEA of FFPE RNAseq data validated enrichment of CTA genes in DUSP22-rearranged ALCL (NES, 1.998; FDR, 0.000; Figure 3D). As in the frozen discovery set, primary cutaneous ALCLs did not significantly cluster together.

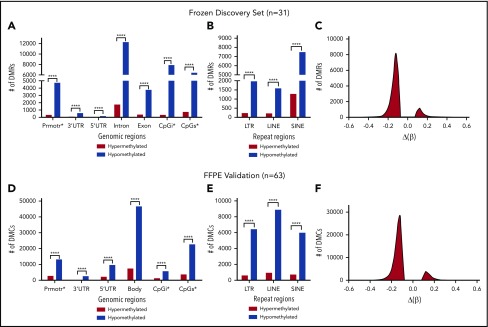

DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs are hypomethylated

Because expression of CTA genes is regulated by DNA methylation, we postulated that DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs would be hypomethylated. First, we performed reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) in the frozen discovery set of 31 ALCLs and examined differentially methylated regions (DMRs) in cases with vs without DUSP22 rearrangements. Indeed, DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs showed marked hypomethylation across all types of genomic regions of interest, including promoters, 3′-untranslated regions, 5′-untranslated regions, introns, exons, CpG islands, and CpG shores; all types of repeat regions, including long terminal repeats, long interspersed nuclear elements, and short interspersed nuclear elements; and based on global methylation changes (Figure 4A-C; supplemental Table 10; all comparisons, P ≤ .0001, χ-square test). We then performed 850K Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip arrays (Illumina) on an independent validation set of 63 FFPE ALCLs (supplemental Table 2) and confirmed that DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs were significantly hypomethylated across all genomic regions, repeat regions, and globally (Figure 4D-F; all P ≤ .0001). Using the same approach, we also specifically compared methylation in ALK-negative ALCLs with DUSP22 rearrangements with that in ALK-positive ALCLs and identified significant hypomethylation in DUSP22-rearranged cases in all analyses for both frozen discovery and FFPE validation sets (supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 4.

ALCLs with DUSP22 rearrangements are hypomethylated. (A) RRBS of DNA extracted from frozen tissue in the 31-sample ALCL discovery set. DMRs reflect comparison of ALCLs with vs without DUSP22 rearrangements and show marked hypomethylation in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs across all types of genomic regions, including promoters, 3′ and 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs), introns, exons, CpG islands (CpGi), and CpG shores (CpGs). (B) Hypomethylation in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs in the discovery set involves all types of noncoding regions, including long terminal repeats (LTRs), long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), and short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs). (C) Histogram showing the distribution of methylation changes [Δ(β)] for DMRs across the genome in the discovery set. (D) MethylationEPIC BeadChip array analysis of DNA extracted from FFPE tissue in an independent validation set of 63 ALCLs. Designations are similar to A, except differentially methylated CpG probes (DMCs) are shown and intron and exon data are represented together as gene bodies. DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs are hypomethylated across all types of genomic regions. (E) Hypomethylation in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs in the validation set involves all types of noncoding regions. (F) Histogram showing the distribution of methylation changes [Δ(β)] for DMRs across the genome in the validation set. ****P ≤ .0001.

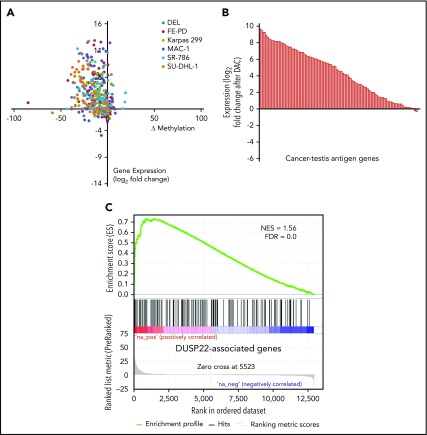

The gene expression signature of DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs is recapitulated by pharmacologic DNA demethylation

DNA demethylating agents are in clinical use for various hematologic and nonhematologic malignancies.47 Having shown that DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs were hypomethylated and overexpressed CTA genes, we next sought to confirm mechanistically that DNA demethylation contributed to this gene expression signature. We treated 6 ALCL cell lines (4 ALK positive, 2 ALK negative; supplemental Figure 4) with the demethylating agent decitabine (2'-deoxy-5-azacytidine; DAC) and used RNA sequencing and RRBS to evaluate gene expression and methylation, respectively. Of 75 evaluable methylation sites in 62 genes in the DUSP22 signature, 56 (75%) showed a decrease in methylation as well as a corresponding increase in gene expression by at least 1.5-fold in at least 2 cell lines on treatment with DAC (Figure 5A). Furthermore, 83 (81%) of 103 measurable CTA genes were upregulated at least 2-fold on DAC treatment (Figure 5B). Finally, genes whose expression was induced by DAC in ALCL cell lines showed enrichment for genes overexpressed in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs in the frozen tissue discovery set (NES, 1.56; FDR, 0.0; Figure 5C). Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that the DUSP22 signature is at least partly attributable to DNA hypomethylation, and indicate that pharmacologic DNA demethylation can partially recapitulate this gene expression signature, particularly for CTA genes.

Figure 5.

Pharmacologic DNA demethylation recapitulates the DUSP22 signature in ALCL cell lines. (A) Changes in percentage methylation (assessed by RRBS) and gene expression (assessed by RNA sequencing) for genes in the DUSP22 signature in 6 ALCL cell lines treated with decitabine (DAC). (B) Average change in expression for 103 CTA genes detectable in ALCL cell lines treated with DAC. (C) DUSP22-associated genes based on gene expression data from the frozen tissue discovery set were enriched among genes whose expression was induced by decitabine in cell lines (see supplemental Methods for additional details). A negative control gene set comprising genes significantly downregulated in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs showed no evidence of enrichment (FDR, 0.54).

DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs lack evidence of immune escape mechanisms

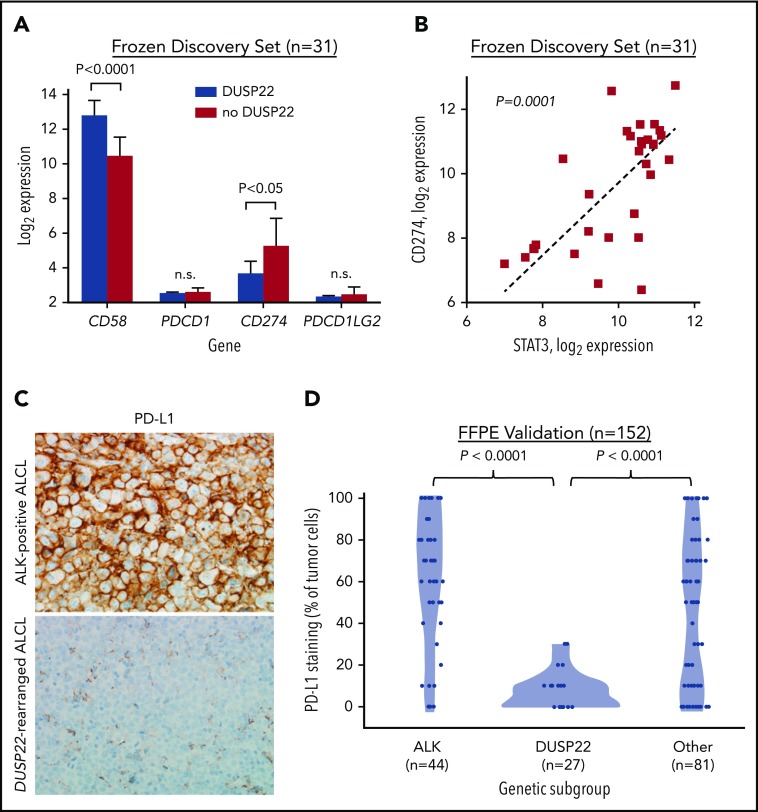

Because DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs showed hypomethylation with increased expression of CTAs and other methylation-regulated genes that might serve as tumor-associated antigens, we considered that the favorable outcomes observed in this subgroup might be a result of enhanced immunogenicity. Effective antitumor immune responses require not only tumor-associated antigens but also costimulatory molecules, immune checkpoint inhibition, and HLA expression, factors modulated by many tumors as mechanisms of immune escape.48 Notably, the costimulatory gene CD58 (encoding the CD2 ligand CD58/LFA3) was among the most overexpressed genes in the DUSP22 signature (8.2-fold higher in DUSP22-rearranged cases; P < .0001, Wilcoxon test; Figure 6A; supplemental Table 9).

Figure 6.

ALCLs with DUSP22 rearrangements show diminished expression of PD-L1 and overexpress CD58. (A) DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs show reduced expression of CD274 (encoding PD-L1) and increased expression of the costimulatory gene CD58. Significant differences in expression of PDCD1 (encoding PD-1) or PDCD1LG2 (encoding PD-L2) were not observed. P values, Wilcoxon test; n.s., not significant. (B) CD274 gene expression correlates with STAT3 gene expression in ALCL. Spearman ρ = 0.63; P = .0001. (C) Immunohistochemistry for PD-L1 in ALK-positive ALCL and DUSP22-rearranged ALCL. Original magnification, ×400. (D) DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs show significantly less tumoral staining for PD-L1 protein than either ALK-positive ALCL or other ALK-negative ALCLs (Wilcoxon test).

The immune checkpoint includes critical interactions between PD-1 expressed on reactive host T cells and its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, and we have directly shown that PD-L1 suppresses host immunity in T-cell lymphoma.49 By gene expression, we found 2.9-fold lower expression of CD274 (encoding PD-L1) in ALCLs with DUSP22 rearrangements than in ALCLs without DUSP22 rearrangements (P < .05), whereas PDCD1 (encoding PD-1) and PDCD1LG2 (encoding PD-L2) were only modestly expressed and were similar in ALCLs with and without DUSP22 rearrangements (Figure 6A). CD274 has been shown to be transcriptionally regulated by STAT3 in ALCL.50,51 Indeed, expression of CD274 correlated strongly with expression of STAT3 (P = .0001, Spearman rank correlation; Figure 6B). Thus, the low expression of CD274 in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs is consistent with the finding that they generally lack STAT3.

Because of the importance of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis to immune escape and immunotherapy, we examined PD-L1 and PD-1 expression at the protein level, using immunohistochemistry. Among 152 FFPE ALCLs independent from the frozen discovery set (supplemental Table 2), some degree of PD-L1 staining was seen in 81% of ALCLs, consistent with previously reported results.51-53 Mean tumoral PD-L1 staining in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs was 7.4% ± 9.0%, which was significantly lower than for either ALK-positive ALCLs (62.5% ± 32.4%; P < .0001, Wilcoxon test; Figure 6C-D) or ALK-negative ALCLs without DUSP22 rearrangements (44.6% ± 36.3%; P < .0001). PD-L1 staining was similar in systemic and cutaneous ALK-negative ALCLs (37.9% ± 37.1% and 30.3% ± 32.5%, respectively; P = .34, Wilcoxon test; not shown). These data confirm low PD-L1 expression in ALCLs with DUSP22 rearrangements. PD-1 expression in the microenvironment was not significantly associated with genetic subtype (supplemental Figure 5), nor with WHO subtype or tumoral PD-L1 staining (not shown).

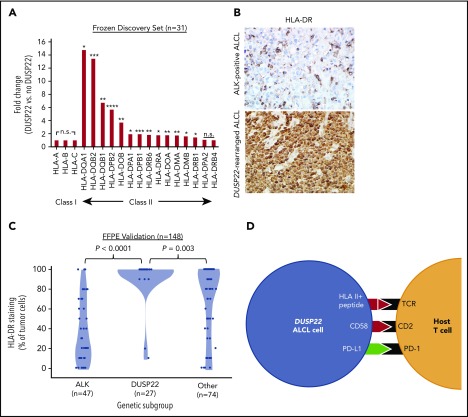

Downregulation of HLA molecules, particularly class II, is an important mechanism of immune escape in lymphoma cells.54,55 Of note, the DUSP22 gene signature included an HLA class II gene probe, HLA-DPB2 (5.7-fold higher in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs; P < .0001, Wilcoxon test; supplemental Table 9); indeed, expression was significantly higher in DUSP22-rearranged cases across nearly all class II, but not class I, HLA genes (Figure 7A). To assess this observation further at the protein level, we performed immunohistochemistry for HLA-DR in 148 FFPE ALCLs independent from the frozen discovery set (supplemental Table 2) and found mean tumoral staining in DUSP22-rearranged cases was 92.2% ± 22.6%, compared with 37.0% ± 31.7% in ALK-positive ALCLs (P < .0001, Wilcoxon test) and 70.0% ± 35.5% in other ALCLs (P = .003; Figure 7B-C). HLA-DR staining was similar in systemic and cutaneous ALK-negative ALCLs (78.2% ± 33.1% and 71.2% ± 35.6%, respectively; P = .30, Wilcoxon test; not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that in addition to hypomethylation-induced expression of tumor-associated antigens, DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs show preserved expression of HLA class II, increased costimulatory gene expression, and diminished expression of immune checkpoint molecules, all features associated with enhanced antitumor immune responses (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

ALCLs with DUSP22 rearrangements express major histocompatibility complex class II. (A) DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs show increased expression of class II but not class I HLA genes. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001; n.s., not significant (Wilcoxon test). (B) Immunohistochemistry for HLA-DR in ALCLs with and without DUSP22 rearrangements. Original magnification, ×400. (C) DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs show significantly more tumoral staining for HLA-DR than either ALK-positive ALCL or other ALK-negative ALCLs (Wilcoxon test). (D) Model of immunogenic cues from DUSP22-rearranged ALCL cells and expected interactions with host reactive T cells. Red indicates upregulated molecules; green indicates downregulated molecules.

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the molecular profile of ALCLs with DUSP22 rearrangements. Our findings, using a multi-omics approach incorporating gene expression profiling, methylation profiling, and protein analysis, indicate that DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs are a molecularly distinct type of ALCL contained within a subset of ALCLs that show downregulation of STAT3-associated genes and lack activated STAT3. Furthermore, DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs show global hypomethylation that contributes to their unique gene expression signature, including upregulation of CTA genes. Finally, DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs overexpress the costimulatory gene CD58, show marked downregulation of the PD-1 ligand PD-L1, and retain expression of HLA class II, suggesting intrinsic blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint and other immunogenic cues that likely contribute to their favorable prognosis.

DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs were entirely contained within a cluster of ALCLs with low expression of STAT3 and other genes in the IL-6-JAK-STAT3 pathway. Although this finding was unexpected, it has been recognized that only 38% to 47% of ALK-negative ALCLs are positive for pSTAT3 by immunohistochemistry.33,38,56 pSTAT3-negativity in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs provides a mechanistic basis for our previous observation that these cases lack expression of the STAT3 target granzyme B9 and may explain retained expression of pan-T-cell antigens such as CD3 in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs,9 as STAT3 inhibits the normal T-cell program.57 Ours is the largest series to date of pSTAT3 immunohistochemistry in ALCL and supports its possible use to select patients for JAK-STAT3 pathway inhibitor therapy.33,58 Notwithstanding, the observation that DUSP22 rearrangement retained prognostic significance among pSTAT3-negative ALCLs led us to investigate additional molecular features unique to ALCLs with this rearrangement.

DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs were markedly hypomethylated compared with other ALCL subgroups, and this hypomethylation drove a distinct DUSP22 gene expression signature that included CTA genes and other developmental genes such as HAND1. Hassler et al previously identified similarities in DNA methylation patterns between ALCL and specific thymic T-cell subsets, but did not identify significant methylation differences between ALK-positive (n = 5) and ALK-negative (n = 5) ALCLs.59 DUSP22 rearrangement status was not reported, but on the basis of the sample number, it is unlikely that heterogeneity in methylation among distinct ALK-negative ALCL subsets would have been discernible. DNA hypomethylation in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs may relate to the absence of pSTAT3, which promotes DNA methylation in ALK-positive ALCL by regulating DNA methyltransferase-1 expression.57 Diminished phosphatase activity in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs might also directly affect DNA methyltransferase activity, which is regulated in part by phosphorylation.60

In addition to CTA overexpression, we discovered other evidence of an immunogenic phenotype in DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs. These cases were characterized by high expression of the costimulatory gene CD58, which encodes the CD2 ligand CD58/LFA3 and is inactivated by a variety of mechanisms and contributes to immune evasion in both B- and T-cell lymphomas.40,61-63 Downregulation of PD-L1 and retained expression of HLA-DR similarly point to the absence of immune escape mechanisms commonly coopted by lymphoma cells.49,54,55,64-66 Although future studies should be aimed at functionally evaluating interactions between DUSP22-rearranged ALCL cells and host immune cells and identifying the antigens underlying these interactions, our data strongly suggest that enhanced immunogenicity contributes to the favorable outcomes observed in this patient subset. Notably, these favorable outcomes do not always indicate complete disease eradication; we have described very long persistence of the neoplastic clone with late recurrence in systemic ALCL with DUSP22 rearrangement in the absence of aggressive disease.67 We also identified DUSP22 rearrangements in a distinct subset of patients with lymphomatoid papulosis, a T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by waxing and waning skin lesions.68 These clinical observations are consistent with a role for the host immune response in controlling disease associated with DUSP22 rearrangements.

Taken together, these findings have important implications for the diagnosis, classification, and possibly treatment of ALCL. In addition to the presence of a unifying chromosomal translocation19,20 and favorable outcomes,9,28,29 DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs have previously been shown to have distinct morphologic features22,69 and phenotype.9,19 Here, we extend these findings and demonstrate that these cases share unique gene expression and DNA methylation profiles and differ from most other ALCLs in lacking activated STAT3. These data suggest that DUSP22 rearrangements identify a unique molecular subtype of ALCL. Identification of DUSP22 rearrangements might facilitate inclusion of lymphomas with variant morphologic patterns into the same disease entity,67 as is the case for ALK-positive ALCL4; however, the diagnosis and classification of ALCL should be made only in the proper clinicopathologic context, as either DUSP22 or ALK may be rearranged in other T-cell lymphomas and lymphoproliferative disorders.19,21,68,70,71 Of note, rare cases examined by gene expression profiling showed discordance between their DUSP22 rearrangement status and their clustering pattern. Possible explanations for this finding include alternate breakpoints or cryptic DUSP22 rearrangements not detectable by the fluorescence in situ hybridization assay used72; genetic events not involving DUSP22 that mimic the DUSP22 signature, as has been shown for the ALK signature34; and additional molecular heterogeneity not fully elucidated by the cases in the present series.

We have previously suggested that DUSP22-rearranged ALCLs may require less intensive therapy than other ALK-negative ALCLs, including possibly avoiding autologous stem-cell transplantation in first remission.9,28-30 The finding of retained immune cues absent in other ALCLs suggests risk-adapted therapy could include strategies to augment the antitumor immune response further, such as through vaccine approaches that have been effective in melanomas and other tumors with CTA overexpression.73 In parallel, our findings may uncover therapeutic opportunities for the more clinically aggressive group of ALK-negative ALCLs lacking DUSP22 rearrangements, which might be pharmacologically reprogrammed into a more immunogenic, “DUSP22-like” molecular signature by demethylating agents and/or immunomodulatory drugs such as checkpoint inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Darlene Knutson and Sara Kloft-Nelson in the Mayo Clinic Cytogenetics Core for fluorescence in situ hybridization scoring, and Fumihiko Tanioka (Iwata City Hospital, Japan), Toshio Oyama (Yamanashi Prefectural Central Hospital, Japan), and Tetsu Yamane (Tsuru City Hospital, Japan) for case collection.

Supported by award numbers R01 CA177734 (A.L.F.), P30 CA15083 (Mayo Clinic Cancer Center), and P50 CA97274 (University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic Lymphoma Specialized Program of Research Excellence [SPORE]) from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) grant number UL1 TR000135 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Science; the Fraternal Order of Eagles Cancer Research Fund; Mayo Clinic Cancer Center (R.A.L.); award number 123012-RSG-12-193-01-TBE from the American Cancer Society (A.L.F.); award number CI-48-09 from the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (A.L.F.); the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic; the Center for Individualized Medicine, Mayo Clinic; and the Predolin Foundation.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: R.A.L. designed the study, conducted experiments, and analyzed data; S.D. designed the study and performed bioinformatic and statistical analyses; N.O. performed and interpreted immunohistochemistry; G. Hu, K.L.R., R.P.K., A.D., N.S.K., J.M.C., J.C.P., W.-J.C., and G. Huang analyzed data; Z.S. and S.B. performed bioinformatic analyses; M.B.P., J.S., X.W., R.K., J.W.S., L.J., S.J.H.-D., M.B.M., P.N., N.N.B., B.K.L., F.F., J.R.C., F.d'A., and S.M.A. contributed samples and clinical data; J.C.P. conducted experiments; A.L.F. designed the study, interpreted immunohistochemistry, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.L.F. and R.P.K. are inventors of technology discussed in this manuscript for which Mayo Clinic holds unlicensed patents. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for A.D. is Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY.

The current affiliation for N.S.K. is Genetics and Genomic Center, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

Correspondence: Andrew L. Feldman, Stabile Building, Room 2-44, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St Southwest, Rochester, MN 55905; e-mail: feldman.andrew@mayo.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Xing X, Feldman AL. Anaplastic large cell lymphomas: ALK positive, ALK negative, and primary cutaneous. Adv Anat Pathol. 2015;22(1):29-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeng Y, Feldman AL. Genetics of anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(1):21-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boddicker RL, Feldman AL. Progress in the identification of subgroups in ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Biomarkers Med. 2015;9(8):719-722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benharroch D, Meguerian-Bedoyan Z, Lamant L, et al. . ALK-positive lymphoma: a single disease with a broad spectrum of morphology. Blood. 1998;91(6):2076-2084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman AL, Harris NL, Stein H, et al. . Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALK-negative. In: Swerdlow SH, et al., eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017:418-421. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falini B, Lamant-Rochaix L, Campo E, et al. . Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALK-positive. In: Swerdlow SH, et al., eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017:413-418. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gascoyne RD, Aoun P, Wu D, et al. . Prognostic significance of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) protein expression in adults with anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Blood. 1999;93(11):3913-3921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savage KJ, Harris NL, Vose JM, et al. ; International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. ALK- anaplastic large-cell lymphoma is clinically and immunophenotypically different from both ALK+ ALCL and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified: report from the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. Blood. 2008;111(12):5496-5504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parrilla Castellar ER, Jaffe ES, Said JW, et al. . ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma is a genetically heterogeneous disease with widely disparate clinical outcomes. Blood. 2014;124(9):1473-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willemze R, Paulli M, Kadin ME. Primary cutaneous CD30-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. In: Swerdlow SH, et al., eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017:392-396. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bekkenk MW, Geelen FA, van Voorst Vader PC, et al. . Primary and secondary cutaneous CD30(+) lymphoproliferative disorders: a report from the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Group on the long-term follow-up data of 219 patients and guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 2000;95(12):3653-3661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oschlies I, Lisfeld J, Lamant L, et al. . ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma limited to the skin: clinical, histopathological and molecular analysis of 6 pediatric cases. A report from the ALCL99 study. Haematologica. 2013;98(1):50-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldman AL, Harris NL, Stein H, et al. . Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, et al., eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017:421-422. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miranda RN, Aladily TN, Prince HM, et al. . Breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: long-term follow-up of 60 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(2):114-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiarle R, Gong JZ, Guasparri I, et al. . NPM-ALK transgenic mice spontaneously develop T-cell lymphomas and plasma cell tumors. Blood. 2003;101(5):1919-1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miething C, Grundler R, Fend F, et al. . The oncogenic fusion protein nucleophosmin-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (NPM-ALK) induces two distinct malignant phenotypes in a murine retroviral transplantation model. Oncogene. 2003;22(30):4642-4647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amin HM, Lai R. Pathobiology of ALK+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2007;110(7):2259-2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hallberg B, Palmer RH. The role of the ALK receptor in cancer biology. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(Suppl 3):iii4-iii15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman AL, Law M, Remstein ED, et al. . Recurrent translocations involving the IRF4 oncogene locus in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Leukemia. 2009;23(3):574-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldman AL, Dogan A, Smith DI, et al. . Discovery of recurrent t(6;7)(p25.3;q32.3) translocations in ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphomas by massively parallel genomic sequencing. Blood. 2011;117(3):915-919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wada DA, Law ME, Hsi ED, et al. . Specificity of IRF4 translocations for primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 204 skin biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(4):596-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King RL, Dao LN, McPhail ED, et al. . Morphologic features of ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphomas with DUSP22 rearrangements. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(1):36-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pham-Ledard A, Prochazkova-Carlotti M, Laharanne E, et al. . IRF4 gene rearrangements define a subgroup of CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a study of 54 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(3):816-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mélard P, Idrissi Y, Andrique L, et al. . Molecular alterations and tumor suppressive function of the DUSP22 (Dual Specificity Phosphatase 22) gene in peripheral T-cell lymphoma subtypes. Oncotarget. 2016;7(42):68734-68748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alonso A, Merlo JJ, Na S, et al. . Inhibition of T cell antigen receptor signaling by VHR-related MKPX (VHX), a new dual specificity phosphatase related to VH1 related (VHR). J Biol Chem. 2002;277(7):5524-5528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li JP, Yang CY, Chuang HC, et al. . The phosphatase JKAP/DUSP22 inhibits T-cell receptor signalling and autoimmunity by inactivating Lck. Nat Commun. 2014;5(1):3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasmatzis G, Johnson SH, Knudson RA, et al. . Genome-wide analysis reveals recurrent structural abnormalities of TP63 and other p53-related genes in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2012;120(11):2280-2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pedersen MB, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Bendix K, et al. . DUSP22 and TP63 rearrangements predict outcome of ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a Danish cohort study. Blood. 2017;130(4):554-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pedersen MB, Relander T, Lauritzsen GF, et al. . The impact of upfront autologous transplant on the survival of adult patients with ALCL and PTCL-NOS according to their ALK, DUSP22 and TP63 gene rearrangement status – a joined Nordic Lymphoma Group and Mayo Clinic analysis [abstract]. Blood. 2017;130(suppl 1). Abstract 822. [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. T-cell lymphomas (version 5.2018). Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/t-cell.pdf Accessed 17 August 2018.

- 31.Zamo A, Chiarle R, Piva R, et al. . Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) activates Stat3 and protects hematopoietic cells from cell death. Oncogene. 2002;21(7):1038-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiarle R, Simmons WJ, Cai H, et al. . Stat3 is required for ALK-mediated lymphomagenesis and provides a possible therapeutic target. Nat Med. 2005;11(6):623-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crescenzo R, Abate F, Lasorsa E, et al. ; European T-Cell Lymphoma Study Group, T-Cell Project: Prospective Collection of Data in Patients with Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma and the AIRC 5xMille Consortium “Genetics-Driven Targeted Management of Lymphoid Malignancies”. Convergent mutations and kinase fusions lead to oncogenic STAT3 activation in anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(4):516-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu G, Dasari S, Asmann YW, et al. . Targetable fusions of the FRK tyrosine kinase in ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2018;32(2):565-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klapper W. What is a true ALCL? Blood. 2014;124(9):1385-1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sekine Y, Tsuji S, Ikeda O, et al. . Regulation of STAT3-mediated signaling by LMW-DSP2. Oncogene. 2006;25(42):5801-5806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sekine Y, Ikeda O, Hayakawa Y, et al. . DUSP22/LMW-DSP2 regulates estrogen receptor-alpha-mediated signaling through dephosphorylation of Ser-118. Oncogene. 2007;26(41):6038-6049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khoury JD, Medeiros LJ, Rassidakis GZ, et al. . Differential expression and clinical significance of tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT3 in ALK+ and ALK- anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(10 Pt 1):3692-3699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Velusamy T, Kiel MJ, Sahasrabuddhe AA, et al. . A novel recurrent NPM1-TYK2 gene fusion in cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 2014;124(25):3768-3771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boddicker RL, Razidlo GL, Dasari S, et al. . Integrated mate-pair and RNA sequencing identifies novel, targetable gene fusions in peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2016;128(9):1234-1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scarfò I, Pellegrino E, Mereu E, et al. ; European T-Cell Lymphoma Study Group. Identification of a new subclass of ALK-negative ALCL expressing aberrant levels of ERBB4 transcripts. Blood. 2016;127(2):221-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iqbal J, Wright G, Wang C, et al. ; Lymphoma Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project and the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project. Gene expression signatures delineate biological and prognostic subgroups in peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2014;123(19):2915-2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piva R, Agnelli L, Pellegrino E, et al. . Gene expression profiling uncovers molecular classifiers for the recognition of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma within peripheral T-cell neoplasms. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(9):1583-1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xing X, Flotte TJ, Law ME, et al. . Expression of the chemokine receptor gene, CCR8, is associated With DUSP22 rearrangements in anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2015;23(8):580-589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jo BS, Koh IU, Bae JB, et al. . Methylome analysis reveals alterations in DNA methylation in the regulatory regions of left ventricle development genes in human dilated cardiomyopathy. Genomics. 2016;108(2):84-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whitehurst AW. Cause and consequence of cancer/testis antigen activation in cancer. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;54(1):251-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Navada SC, Steinmann J, Lübbert M, Silverman LR. Clinical development of demethylating agents in hematology. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(1):40-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pizzi M, Boi M, Bertoni F, Inghirami G. Emerging therapies provide new opportunities to reshape the multifaceted interactions between the immune system and lymphoma cells. Leukemia. 2016;30(9):1805-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilcox RA, Feldman AL, Wada DA, et al. . B7-H1 (PD-L1, CD274) suppresses host immunity in T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 2009;114(10):2149-2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marzec M, Zhang Q, Goradia A, et al. . Oncogenic kinase NPM/ALK induces through STAT3 expression of immunosuppressive protein CD274 (PD-L1, B7-H1). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(52):20852-20857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Atsaves V, Tsesmetzis N, Chioureas D, et al. . PD-L1 is commonly expressed and transcriptionally regulated by STAT3 and MYC in ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2017;31(7):1633-1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Panjwani PK, Charu V, DeLisser M, Molina-Kirsch H, Natkunam Y, Zhao S. Programmed death-1 ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 show distinctive and restricted patterns of expression in lymphoma subtypes. Hum Pathol. 2018;71:91-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt J, Bonzheim I, Steinhilber J, et al. . EMMPRIN (CD147) is induced by C/EBPβ and is differentially expressed in ALK+ and ALK- anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Lab Invest. 2017;97(9):1095-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rimsza LM, Roberts RA, Miller TP, et al. . Loss of MHC class II gene and protein expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is related to decreased tumor immunosurveillance and poor patient survival regardless of other prognostic factors: a follow-up study from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Molecular Profiling Project. Blood. 2004;103(11):4251-4258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steidl C, Shah SP, Woolcock BW, et al. . MHC class II transactivator CIITA is a recurrent gene fusion partner in lymphoid cancers. Nature. 2011;471(7338):377-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song JY, Song L, Herrera AF, et al. . Cyclin D1 expression in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Mod Pathol. 2016;29(11):1306-1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ambrogio C, Martinengo C, Voena C, et al. . NPM-ALK oncogenic tyrosine kinase controls T-cell identity by transcriptional regulation and epigenetic silencing in lymphoma cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69(22):8611-8619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gupta M, Maurer MJ, Stenson M, et al. . In-vivo activation of STAT3 in angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma, PTCL not otherwise specified, and ALK negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma: implications for therapy [abstract]. Blood. 2013;122(21). Abstract 844. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hassler MR, Pulverer W, Lakshminarasimhan R, et al. . Insights into the pathogenesis of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma through genome-wide DNA methylation profiling. Cell Reports. 2016;17(2):596-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deplus R, Blanchon L, Rajavelu A, et al. . Regulation of DNA methylation patterns by CK2-mediated phosphorylation of Dnmt3a. Cell Reports. 2014;8(3):743-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Challa-Malladi M, Lieu YK, Califano O, et al. . Combined genetic inactivation of β2-Microglobulin and CD58 reveals frequent escape from immune recognition in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(6):728-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palomero T, Couronné L, Khiabanian H, et al. . Recurrent mutations in epigenetic regulators, RHOA and FYN kinase in peripheral T cell lymphomas. Nat Genet. 2014;46(2):166-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoshida N, Karube K, Utsunomiya A, et al. . Molecular characterization of chronic-type adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74(21):6129-6138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu WR, Shipp MA. Signaling pathways and immune evasion mechanisms in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2017;130(21):2265-2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kiyasu J, Miyoshi H, Hirata A, et al. . Expression of programmed cell death ligand 1 is associated with poor overall survival in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2015;126(19):2193-2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, et al. . PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):311-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feldman AL, Grogg KL, Knudson RA, Inwards DJ. Secondary cutaneous involvement by systemic anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphoma with 6p25.3 rearrangement. Histopathology. 2015;67(6):932-935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karai LJ, Kadin ME, Hsi ED, et al. . Chromosomal rearrangements of 6p25.3 define a new subtype of lymphomatoid papulosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(8):1173-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Onaindia A, Montes-Moreno S, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, et al. . Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphomas with 6p25.3 rearrangement exhibit particular histological features. Histopathology. 2015;66(6):846-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wehkamp U, Oschlies I, Nagel I, et al. . ALK-positive primary cutaneous T-cell-lymphoma (CTCL) with unusual clinical presentation and aggressive course. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42(11):870-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abdulla FR, Sarpa H, Cassarino D. The expression of ALK in mycosis fungoides, stage IA. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40(3):348-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim MJ, Cho SY, Kim MH, et al. . FISH-negative cryptic PML-RARA rearrangement detected by long-distance polymerase chain reaction and sequencing analyses: a case study and review of the literature. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;203(2):278-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gjerstorff MF, Andersen MH, Ditzel HJ. Oncogenic cancer/testis antigens: prime candidates for immunotherapy. Oncotarget. 2015;6(18):15772-15787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.