Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) has been postulated to be the third gasotransmitter in both animals and plants after nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO). In this review, the physiological roles of H2S in plant growth, development and responses to biotic, and abiotic stresses are summarized. The enzymes which generate H2S are subjected to tight regulation to produce H2S when needed, contributing to delicate responses of H2S to environmental stimuli. H2S occupies a central position in plant sulfur metabolism as it is the link of inorganic sulfur to the first organic sulfur-containing compound cysteine which is the starting point for the synthesis of methionine, coenzyme A, vitamins, etc. In sulfur assimilation, adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate reductase (APR) is the rate-limiting enzyme with the greatest control over the pathway and probably the generation of H2S which is an essential component in this process. APR is an evolutionarily conserved protein among plants, and two conserved domains PAPS_reductase and Thioredoxin are found in APR. Sulfate reduction including the APR-catalyzing step is carried out in chloroplasts. APR, the key enzyme in sulfur assimilation, is mainly regulated at transcription level by transcription factors in response to sulfur availability and environmental stimuli. The cis-acting elements in the promoter region of all the three APR genes in Solanum lycopersicum suggest that multiple factors such as sulfur starvation, cytokinins, CO2, and pathogens may regulate the expression of SlAPRs. In conclusion, as a critical enzyme in regulating sulfur assimilation, APR is probably critical for H2S generation during plants’ response to diverse environmental factors.

Keywords: hydrogen sulfide (H2S), adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate reductase (APR), sulfur assimilation, transcription factors, gene expression

Introduction

Over centuries, hydrogen sulfide (H2S) has only been well-known for its unpleasant smell and fierce toxicity. After the gaseous signals nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO), H2S is recently emerging as a multifunctional signaling molecule in animals, and plants. Endogenous H2S production has been observed in mammalian cells and shown to control a variety of physiological processes and play important roles in the regulation of the pathogenesis of various diseases (Wang, 2012). In plants, sulfur is an essential macronutrient for growth and development, participating in the synthesis of cysteine, methionine and in many other essential cellular constituents, such as reduced glutathione (GSH) and coenzyme A (Romero et al., 2014). Endogenous H2S in plant is generated through the pathway of sulfur assimilation or the decomposition of L-/D-cysteine. L-cysteine desulfhydrase (LCD) catalyzes the production of H2S, ammonia and pyruvate with L-cysteine as the substrate, while DCD degrades D-cysteine to generate H2S in mitochondria (Rausch and Wachter, 2005). Besides, an O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase homolog DES1 also shows L-Cysteine desulfhydrase activity in Arabidopsis (Álvarez et al., 2010). In sulfur assimilation, sulfite is reduced by sulfite reductase (SiR) to produce H2S in chloroplast (Rausch and Wachter, 2005). Adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate reductase (APR) is a rate-limiting enzyme in sulfur assimilation, which controls the flow of inorganic sulfur into cysteine and probably the endogenous production of H2S. In recent decades, we have witnessed significant progresses in the functional study of H2S and here we reviewed the physiological role of H2S in plant, the central role of APR in sulfur assimilation and proposed the future perspectives of APR research.

Physiological Role of H2S in Plant

Accumulating articles show that endogenous H2S is involved in various physiological activities in animals including human, such as vasodilation, anti-hypertensive, anti-inflammatory, heart protection, smooth muscle relaxation, promotion of vascular endothelial cell proliferation, and brain development (Wang, 2012). Meanwhile, the past decade has witnessed a growing body of evidence confirming the signaling role of H2S in plants as well. Although phytotoxic at high concentrations, low dose of H2S has been shown to play important roles in diverse processes of plant life, including plant growth, and development, responses to biotic and abiotic stresses (Zhang et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011; Shen et al., 2012, 2013; Jin et al., 2013; Xie et al., 2014). H2S improves seed germination and the yield of multiple crops including bean, corn, wheat, and pea (Dooley et al., 2013). H2S also interacts with NO, CO and auxin to modulate root formation, both lateral and adventitious roots (Zhang et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2012; Fang H. et al., 2014; Fang T. et al., 2014; Jia et al., 2015). Also, accumulating researches find that H2S alleviates diverse abiotic stresses including heavy metal stress, drought and osmotic stresses by improving the antioxidative capacity in plant (Zhang et al., 2008, 2010; Sun et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2014). Salicylic acid (SA) induces endogenous H2S production by increasing LCD activity to tolerate Cd stress, while the positive effect of SA is diminished in LCD-knockout A. thaliana, suggesting that H2S acts downstream of SA in regulating Cd tolerance (Qiao et al., 2015). Stomatal movement is crucial for plant responses to environmental stimuli, and H2S is found to interact with ABA in the stomatal regulation responsible for drought stress in A. thaliana (Jin et al., 2013). Consistently, Scuffi et al. (2014) observed that ABA failed to close stomata in des1 mutant which encoding a L-cysteine desulfhydrase, suggesting that endogenous H2S is essential for ABA signaling in guard cells. H2S also plays a vital role in plant response to biotic stress. In A. thaliana, endogenous H2S increases when plant is infected with Pseudomonas syringae (Shi et al., 2015). Besides, the activity of DES1 is elevated in pathogen-infected plants (Bloem et al., 2004). H2S can also delay flower opening and senescence in cut flowers (Zhang et al., 2011). Later the senescence-alleviating effect of H2S is found in diverse postharvest fruits and vegetables including strawberry, kiwifruit, grape, apple, banana and broccoli, possibly through improving antioxidative capacity and antagonizing the production of ethylene, a hormone playing a major role in plant senescence, and fruit ripening (Hu et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; Ni et al., 2016; Ge et al., 2017). Besides, H2S generated in cytosol negatively regulates autophagy and modulates the transcriptional profile of A. thaliana by the study of des1 mutant, whereas the negative regulation of autophagy by sulfide is independent of reactive oxygen species (Álvarez et al., 2012; Laureano-Marín et al., 2016). The multifunctional role of H2S in plant growth and development highlights the importance of the regulation of endogenous generation of H2S in adaption to growth stages and in response to biotic and abiotic stresses.

Endogenous Production of H2S in Plant and the Central Role of 5′-Adenylylsulfate Reductase in Sulfur Assimilation

Sulfur is essential for all living organisms as a key constituent of the amino acids cysteine and methionine, as well as GSH, several group-transfer coenzymes and vitamins (Romero et al., 2014). Animals require dietary sources of methionine as their cells are not able to assimilate inorganic sulfur. The endogenous generating enzymes of H2S in mammals are known as cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE), cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS), and 3-mercaptopyruvate transsulfatase (3-MST) (Wang, 2012). In contrary to animals, plants reduce and incorporate inorganic sulfur, which is almost entirely available as oxidized sulfate, into cysteine via the reductive sulfate assimilation pathway.

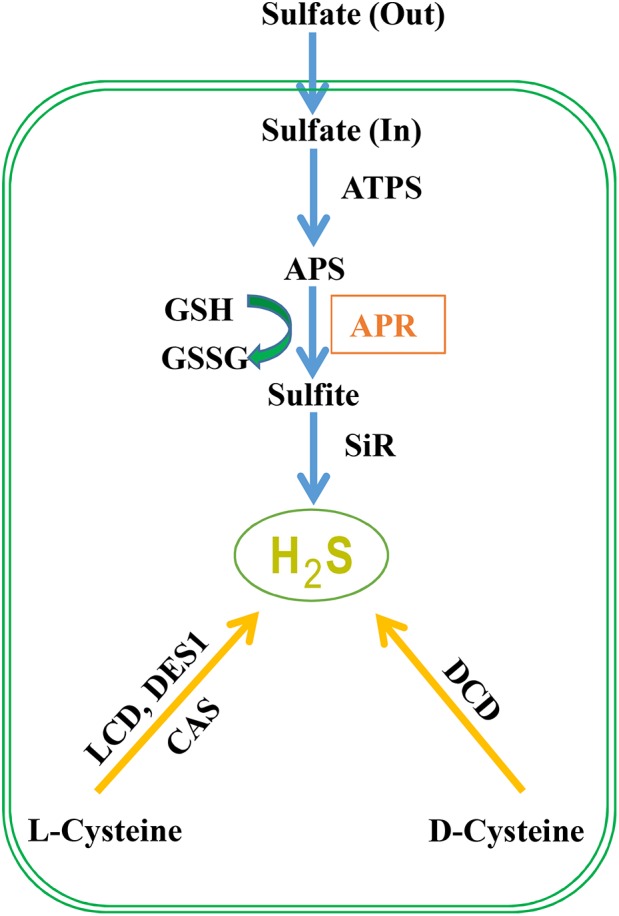

Sulfate from the soil is transported by a proton/sulfate co-transport mediated by sulfate transporters in root epidermal cells, which subsequently is loaded into the xylem vessels and distribute it to the entire plant (Leustek et al., 2000). Then sulfate is stored into vacuoles or transported to chloroplasts to start the assimilatory pathway (Gotor et al., 2015). Before sulfate reduction, sulfate is activated to adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (APS) catalyzed by ATP sulfurylase, and in A. thaliana, three chloroplast, and one cytosolic isoforms are discovered (Hatzfeld et al., 2000). Through two enzymatic steps located exclusively in chloroplast or plastid, APS is then reduced to produce H2S (Figure 1). The first step is the reduction of APS to sulfite by APS reductase (APR) using GSH as the reducing molecule. In the second step, sulfite is reduced to sulfide catalyzed by sulfite reductase in a six-electron reaction using reduced ferredoxin as reductant. APS can also be phosphorylated to 3′-phospho-APS (PAPS) by adenosine-5′-phosphosulfae kinase (APSK) to provide a sulfate donor for the modification of multiple natural products (Ravilious et al., 2012). Besides the sulfide production in sulfur assimilation, cysteine (Cys) could be degraded to generate H2S which is catalyzed by LCD, DCD, an O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase OASTL family protein DES1 or β-cyanoalanine synthase (an enzyme catalyzing the conversion of cysteine and cyanide to H2S and β-cyanoalanine) (Hatzfeld et al., 2000; Álvarez et al., 2010). Although the contribution of cysteine degradation to H2S has been highly valued, we propose that the influx of inorganic sulfur to cysteine is also crucial for H2S generation. The transport of sulfate into cells and the reduction of APS to sulfite by APR are the key regulatory steps of sulfate assimilation and APR is considered as the rate-limiting enzyme. Thus, the activity of the sulfur assimilation pathway controlled by APR may be required for animated response to changes in sulfur supply and to environmental stimuli that alter the need for reduced sulfur.

FIGURE 1.

H2S metabolism in plants. Sulfate absorbed by plant roots through sulfate transporters is activated to APS (5′-adenylylsulfate) via ATP sulfurylase. APS can be reduced to sulfite by APR (APS reductase) which is further reduced to H2S by sulfite reductase. Subsequently, H2S is incorporated to cysteine (Cys), which is the first organic product of sulfur assimilation, and the starting point for methionine synthesis. Besides, cysteine is involved in the biosynthesis of coenzymes and vitamins including coenzyme A, biotin, thiamine, lipoic acid, and SAM (S-adenosyl-L-methionine) which is the donor of methylation. Besides the route of S-assimilation, H2S can also be produced from cysteine via the action of L-cysteine desulfhydrase (LCD), D-cysteine desulfhydrase (DCD), and DES1 which is member of O-acetylserine thiol lyase (OASTL) family proteins. Cyanoalanine synthase (CAS) generates cyanoalanine co-formed with H2S with cyanide and cysteine as the substrates.

Functional Domains in APR Proteins

Two domains of PAPS_reductase (adenosine 3′-phosphate 5′-phosphosulfate reductase) and Thioredoxin are found in APR proteins (Kopriva and Koprivova, 2004). The plant APR gene is believed to originate from a fusion between prokaryotic genes for APS or PAPS reductase and thioredoxin. The N-terminal domain (PAPS_reductase) constitutes the active center of APR, and C-terminal domain Thioredoxin is required for transferring electrons from GSH to the N-terminal domain (Bick et al., 1998; Kopriva et al., 2001). Despite that the sequence of the C-terminal domain of APR is more homologous to thioredoxin than to glutaredoxin, it functions as an efficient glutaredoxin (Leustek et al., 2000). Three independent steps are proposed for the reaction: the transfer of sulfate from APS to the active cysteine residue, the release of the sulfite by C-terminal domain, and the recovery of the active enzyme dimer by reaction with thiol. It has been found that plant APR contains an iron-sulfur cluster that is bound by the N-terminal domain (Kopriva et al., 2001), which is a decisive structure in the sulfate reduction pathway.

Subcellular Localization of APR

Plastid or chloroplast is the only compartment that contains the enzymes for sulfur assimilation from sulfate to cysteine. Correspondingly, APR activity is localized in chloroplasts in spinach and in pea (Schmidt, 1976; Fankhauser and Brunold, 1978; Prior et al., 1999). Subsequently, the plastid localization of APR is confirmed in three Flaveria species by immunolocalization (Koprivova et al., 2001).

Functional Characterization and Regulation of APR

As a rate-limiting enzyme, APR possesses a very high control over the flux through sulfate assimilation. It is reported that natural variation for sulfate content in A. thaliana is highly associated with APR2 and a T-DNA insertion in APR2 (apr2-1) induces more sulfate compared with wild type (Loudet et al., 2007). Besides, deletion of APR in Physcomitrella patens caused 50% reduction in the flux through sulfur reduction (Koprivova et al., 2002). Conversely, Arabidopsis overexpressing a Pseudomonas APR gene accumulates more sulfite, thiosulfate, cysteine, γ-glutamylcysteine and GSH, further confirming the important role of APR in sulfur assimilation (Tsakraklides et al., 2002). The metabolites in sulfur metabolism such as sulfite, H2S, cysteine and GSH are highly interconnected, thus interruption of the reaction from APS to sulfite carried out by APR will decrease the generation of H2S in plant. Therefore, we propose that the regulation of APR in sulfur assimilation might be critical for the dynamic H2S generation in response to environmental factors.

The uptake of sulfate and the reduction of APS by APR are controlled by the sulfur nutritional status of the plant. For instance, the three isoforms of APR in Arabidopsis are affected at expression and activity levels by the sulfur status, cysteine, GSH, O-acetylserine, nitrogen supply, sugars or phytohormones (Kopriva et al., 1999; Koprivova et al., 2000; Ohkama et al., 2002; Hesse et al., 2003; Kopriva and Koprivova, 2003). Exogenous addition of GSH to poplars not only increases GSH content, but also reduces APR activity and mRNA accumulation. GSH transport across the plasma membrane is a possible mechanism of the feedback regulation of sulfate assimilation by GSH. The postulation of a signaling GSH transporter, similar to the signaling hexose and sucrose transporters in sugar sensing (reviewed in Smeekens and Rook, 1997), would explain why APR is down-regulated only by exogenously added GSH. Also, GSH has been shown to be a negative signal for the regulation of APR expression in A. thaliana root cultures (Vauclare et al., 2002). H2S, an intermediate and also a signal in sulfur assimilation, induces a rapid increase in thiol compounds in the shoot of Allium cepa L. and Brassica oleracea L. and results in a down-regulation of APR activity and its mRNA levels (Durenkamp et al., 2007). In poplar trees, sulfur limitation induces an increase in mRNA levels of ATP sulfurylase, APR, and sulfite reductase, probably as an adaptation mechanism to increase the efficiency of the sulfate assimilation pathway (Kopriva et al., 2004). When the seedlings of curly kale (B. oleracea L.) are transferred to sulfate-deprived conditions, the expression of sulfate transporters and the activity and expression of APR are induced in roots and shoots respectively, suggesting that external sulfate status is the sensing factor for the modulation of sulfate uptake and its reduction (Koralewska et al., 2009).

Sulfur-containing compounds especially GSH play vital roles in plant response to stress conditions. Thus APR, a rate-limiting enzyme in cysteine synthesis, is closely related to GSH synthesis which is primarily dependent on the availability of the constituent amino acids. NaCl stress increases APR activity and its mRNA levels by 3-fold of all three isoforms in A. thaliana, but the response of APR to salt stress is independent of abscisic acid (ABA) and the induction of APR activity is not essential for the increase of GSH synthesis after salt stress (Koprivova et al., 2008). APR also plays a key role in plant response to selenate toxicity. A mutant Arabidopsis line (apr2-1) shows decreased selenate tolerance and photosynthetic efficiency, accompanied with an increase in total sulfur and sulfate and a 2-fold decrease in GSH concentration (Grant et al., 2011).

Phytohormones also affect sulfate uptake and assimilation. The key enzyme APR is regulated by ethylene, ABA, NO and other hormones (Koprivova and Kopriva, 2016). Ethylene synthesis and sulfur metabolism are closely connected through S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) and methionine salvage cycle. Feeding of ethylene precursor 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) can up-regulate APR activity by increasing mRNA levels of APR1 and APR3 in Arabidopsis (Koprivova et al., 2008). Zeatin is found to increase transcript accumulation of APR1 and SULTR2;2, as a general effect on sulfate assimilation (Ohkama et al., 2002). Salicylate also induces the expression of all three APR isoforms and enzyme activity in Arabidopsis (Koprivova et al., 2008). Moreover, APR2 expression is regulated by light/dark cycles and sucrose feeding (Kopriva et al., 1999).

Previous researches show a strict correlation between APR mRNA levels, protein accumulation and enzyme activity, suggesting that APR is primarily regulated at the transcriptional level (Kopriva et al., 1999; Kopriva and Koprivova, 2004). APR expression is activated by the MYB transcription factors MYB28 and MYB51 in Arabidopsis (Yatusevich et al., 2010). The bZIP transcription factor LONG HYPOCOTYL 5 (HY5) is also found to regulate the expression of APR1 and APR2 instead of APR3 in response to dark adaption and sulfur status in Arabidopsis (Lee et al., 2011). Thus, the coordinated expression of APR by HY5 and MYB transcription factors links the regulation of sulfate assimilation to plant responses to environmental stimuli such as light, sulfur availability, and stress conditions.

Besides, modulation of APR activity via posttranslational redox regulation has been demonstrated in Arabidopsis subjected to oxidative stress, which provides a rapidly responding, self-regulating mechanism to control GSH synthesis (Bick et al., 2001). Salt stress is found to induce APR mRNA levels, whereas its protein accumulation is not observed, suggesting a likely translational regulation to control APR activity (Koprivova et al., 2008). The activity of APR is also regulated by the reduced form of sulfur through the transition from active dimer to inactive monomers (Kopriva and Koprivova, 2004). MicroRNA miR395 is found to target sulfate assimilation pathway by recognizing a low affinity sulfate transporter SULTR2;1 and three ATPS genes ATPS1, 3 and 4, whereas APR is not targeted by miR395 (Jones-Rhoades and Bartel, 2004; Allen et al., 2005). Whether there are other microRNAs regulating APR apart of miR395 or whether APR is subjected to protein modification such as phosphorylation is still unclear and needs further research.

Future Perspectives

The regulation of APR in sulfur assimilation and H2S generation is complex which involving many signals and effectors. The sulfur-responsive cis-element SURECOREATSULTR11 is sufficient and necessary for sulfur deficiency responsive expression of the high-affinity sulfate transporter gene SULTR1;1 in Arabidopsis roots, which could be reversed when supplied with cysteine and GSH (Maruyama-Nakashita et al., 2005). APR3 (At4g21990) in Arabidopsis containing SURECOREATSULTR11 cis-acting element also shows response to sulfur deficiency conditions (Maruyama-Nakashita et al., 2005; Henríquez-Valencia et al., 2018). However, although APR is highly regulated in plants, transcription factors responsible for this regulation are still not fully understood. Bioinformatic approaches predict that gene expression response to sulfur deficiency is regulated by a limited number of transcription factors including MYBs, bZIPs, and NF-YAs, indicating that these transcription factors may play important roles in the sulfur status response (Henríquez-Valencia et al., 2018). Besides, other cis-regulatory elements are found in the promoter region of SlAPR genes, which may response to distinct plant hormones, such as cytokinins, and several environmental factors, as well as CO2, light, and abiotic and biotic stresses. Thus, considering the central role of APR in sulfur assimilation and possibly in H2S generation, how it is regulated by environmental signals and phytohormones still needs further research.

Author Contributions

YF, JT, G-FY, Z-QH, Y-HL, X-YC, K-DH, and HZ conceived the paper. YF, G-FY, L-YH, K-DH, and HZ wrote the paper. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System (Grant No. CARS-10-B1), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31670278, 31470013, and 31300133), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. JZ2018HGTB0241), and Anhui Provincial Science and Technology Major Project (Grant No. 16030701073).

References

- Allen E., Xie Z., Gustafson A. M., Carrington J. C. (2005). MicroRNA-directed phasing during trans-acting siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell 121 207–221. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez C., Calo L., Romero L. C., García I., Gotor C. (2010). An O-acetylserine (thiol)lyase homolog with L-cysteine desulfhydrase activity regulates cysteine homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 152 656–669. 10.1104/pp.109.147975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez C., García I., Moreno I., Pérez-Pérez M. E., Crespo J. L., Romero L. C., et al. (2012). Cysteine-generated sulfide in the cytosol negatively regulates autophagy and modulates the transcriptional profile in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24 4621–4634. 10.1105/tpc.112.105403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bick J. A., Aslund F., Chen Y., Leustek T. (1998). Glutaredoxin function for the carboxyl-terminal domain of the plant-type 5′-adenylylsulfate reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 8404–8409. 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bick J. A., Setterdahl A. T., Knaff D. B., Chen Y., Pitcher L. H., Zilinskas B. A., et al. (2001). Regulation of the plant-type 5′-adenylyl sulfate reductase by oxidative stress. Biochemistry 40 9040–9048. 10.1021/bi010518v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloem E., Riemenschneider A., Volker J., Papenbrock J., Schmidt A., Salac I., et al. (2004). Sulphur supply and infection with Pyrenopeziza brassicae influence L-cysteine desulphydrase activity in Brassica napus L. J. Exp. Bot. 55 2305–2312. 10.1093/jxb/erh236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Wu F. H., Wang W. H., Zheng C. J., Lin G. H., Dong X. J., et al. (2011). Hydrogen sulphide enhances photosynthesis through promoting chloroplast biogenesis, photosynthetic enzyme expression, and thiol redox modification in Spinacia oleracea seedlings. J. Exp. Bot. 62 4481–4493. 10.1093/jxb/err145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley F. D., Nair S. P., Ward P. D. (2013). Increased growth and germination success in plants following hydrogen sulfide administration. PLoS One 8:e62048. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durenkamp M., De Kok L. J., Kopriva S. (2007). Adenosine 5′-phosphosulphate reductase is regulated differently in Allium cepa L. and Brassica oleracea L. upon exposure to H2S. J. Exp. Bot. 58 1571–1579. 10.1093/jxb/erm031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H., Tao J., Liu Z., Zhang L., Jin Z., Pei Y. (2014). Hydrogen sulfide interacts with calcium signaling to enhance the chromium tolerance in Setaria italica. Cell Calcium 56 472–481. 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang T., Cao Z., Li J., Shen W., Huang L. (2014). Auxin-induced hydrogen sulfide generation is involved in lateral root formation in tomato. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 76 44–51. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser H., Brunold C. (1978). Localization of adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate sulfotransferase in spinach leaves. Planta 143 285–289. 10.1007/BF00392000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S. P., Hu K. D., Hu L. Y., Li Y. H., Han Y., Wang H. L., et al. (2013). Hydrogen sulfide delays postharvest senescence and plays an antioxidative role in fresh-cut kiwifruit. HortScience 48 1385–1392. [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y., Hu K. D., Wang S. S., Hu L. Y., Chen X. Y., Li Y. H., et al. (2017). Hydrogen sulfide alleviates postharvest ripening and senescence of banana by antagonizing the effect of ethylene. PLoS One 12:e0180113. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotor C., Laureano-Marín A. M., Moreno I., Aroca Á, García I., Romero L. C. (2015). Signaling in the plant cytosol: cysteine or sulfide? Amino Acids 47 2155–2164. 10.1007/s00726-014-1786-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant K., Carey N. M., Mendoza M., Schulze J., Pilon M., Pilon-Smits E. A., et al. (2011). Adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate reductase (APR2) mutation in Arabidopsis implicates glutathione deficiency in selenate toxicity. Biochem. J. 438 325–335. 10.1042/BJ20110025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzfeld Y., Lee S., Lee M., Leustek T., Saito K. (2000). Functional characterization of a gene encoding a fourth ATP sulfurylase isoform from Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene 248 51–58. 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00132-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henríquez-Valencia C., Arenas-M A., Medina J., Canales J. (2018). Integrative transcriptomic analysis uncovers novel gene modules that underlie the sulfate response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 9:470. 10.3389/fpls.2018.00470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse H., Trachsel N., Suter M., Kopriva S., von Ballmoos P., Rennenberg H., et al. (2003). Effect of glucose on assimilatory sulphate reduction in Arabidopsis thaliana roots. J. Exp. Bot. 54 1701–1709. 10.1093/jxb/erg177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. Y., Hu S. L., Wu J., Li Y. H., Zheng J. L., Wei Z. J., et al. (2012). Hydrogen sulfide prolongs postharvest shelf life of strawberry and plays an antioxidative role in fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60 8684–8693. 10.1021/jf300728h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H., Hu Y., Fan T., Li J. (2015). Hydrogen sulfide modulates actin-dependent auxin transport via regulating ABPs results in changing of root development in Arabidopsis. Sci. Rep. 5:8251. 10.1038/srep08251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z., Xue S., Luo Y., Tian B., Fang H., Li H., et al. (2013). Hydrogen sulfide interacting with abscisic acid in stomatal regulation responses to drought stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 62 41–46. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Rhoades M. W., Bartel D. P. (2004). Computational identification of plant microRNAs and their targets, including a stress-induced miRNA. Mol. Cell 14 787–799. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopriva S., Büchert T., Fritz G., Suter M., Weber M., Benda R., et al. (2001). Plant adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate reductase is a novel iron–sulfur protein. J. Biol. Chem. 276 42881–42886. 10.1074/jbc.M107424200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopriva S., Koprivova A. (2003). “Sulphate assimilation: a pathway which likes to surprise,” in Sulphur in Higher Plants eds Abrol Y. P., Ahmad A. (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; ) 87–112. 10.1007/978-94-017-0289-8_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kopriva S., Koprivova A. (2004). Plant adenosine 5′-phosphosulphate reductase: the past, the present, and the future. J. Exp. Bot. 55 1775–1783. 10.1093/jxb/erh185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopriva S., Muheim R., Koprivova A., Trachsel N., Catalano C., Suter M., et al. (1999). Light regulation of assimilatory sulphate reduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 20 37–44. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00573.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koprivova A., Kopriva S. (2016). Hormonal control of sulfate uptake and assimilation. Plant Mol. Biol. 91 617–627. 10.1007/s11103-016-0438-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopriva S., Hartmann T., Massaro G., Hönicke P., Rennenberg H. (2004). Regulation of sulfate assimilation by nitrogen and sulfur nutrition in poplar trees. Trees 18 320–326. 10.1007/s00468-003-0309-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koprivova A., Melzer M., von Ballmoos P., Mandel T., Brunold C., Kopriva S. (2001). Assimilatory sulfate reduction in C(3), C(3)-C(4), and C(4) species of Flaveria. Plant Physiol. 127 543–550. 10.1104/pp.010144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koprivova A., Meyer A. J., Schween G., Herschbach C., Reski R., Kopriva S. (2002). Functional knockout of the adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate reductase gene in Physcomitrella patens revives an old route of sulfate assimilation. J. Biol. Chem. 277 32195–32201. 10.1074/jbc.M204971200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koprivova A., North K. A., Kopriva S. (2008). Complex signaling network in regulation of adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate reductase by salt stress in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Physiol. 146 1408–1420. 10.1104/pp.107.113175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koprivova A., Suter M., den Camp R. O., Brunold C., Kopriva S. (2000). Regulation of sulfate assimilation by nitrogen in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 122 737–746. 10.1104/pp.122.3.737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koralewska A., Buchner P., Stuiver C. E., Posthumus F. S., Kopriva S., Hawkesford M. J., et al. (2009). Expression and activity of sulfate transporters and APS reductase in curly kale in response to sulfate deprivation and re-supply. J. Plant Physiol. 166 168–179. 10.1016/j.jplph.2008.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laureano-Marín A. M., Moreno I., Romero L. C., Gotor C. (2016). Negative regulation of autophagy by sulfide is independent of reactive oxygen species. Plant Physiol. 171 1378–1391. 10.1104/pp.16.00110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B. R., Koprivova A., Kopriva S. (2011). The key enzyme of sulfate assimilation, adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate reductase, is regulated by HY5 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 67 1042–1054. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04656.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leustek T., Martin M. N., Bick J. A., Davies J. P. (2000). Pathways and regulation of sulfur metabolism revealed through molecular and genetic studies. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 51 141–165. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. P., Hu K. D., Hu L. Y., Li Y. H., Jiang A. M., Xiao F., et al. (2014). Hydrogen sulfide alleviates postharvest senescence of broccoli by modulating antioxidant defense and senescence-related gene expression. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62 1119–1129. 10.1021/jf4047122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. T., Li M. Y., Cui W. T., Lu W., Shen W. B. (2012). Haem oxygenase-1 is involved in hydrogen sulfide-induced cucumber adventitious root formation. J. Plant Growth Regul. 31 519–528. 10.1007/s00344-012-9262-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loudet O., Saliba-Colombani V., Camilleri C., Calenge F., Gaudon V., Koprivova A., et al. (2007). Natural variation for sulfate content in Arabidopsis thaliana is highly controlled by APR2. Nat. Genet. 39 896–900. 10.1038/ng2050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama-Nakashita A., Nakamura Y., Watanabe-Takahashi A., Inoue E., Yamaya T., Takahashi H. (2005). Identification of a novel cis-acting element conferring sulfur deficiency response in Arabidopsis roots. Plant J. 42 305–314. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02363.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Z. J., Hu K. D., Song C. B., Ma R. H., Li Z. R., Zheng J. L., et al. (2016). Hydrogen sulfide alleviates postharvest senescence of grape by modulating the antioxidant defenses. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016:4715651. 10.1155/2016/4715651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkama N., Takei K., Sakakibara H., Hayashi H., Yoneyama T., Fujiwara T. (2002). Regulation of sulfur-responsive gene expression by exogenously applied cytokinins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 43 1493–1501. 10.1093/pcp/pcf183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior A., Uhrig J. F., Heins L., Wiesmann A., Lillig C. H., Stoltze C., et al. (1999). Structural and kinetic properties of adenylyl sulphate reductase from Catharanthus roseus cell cultures. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1430 25–38. 10.1016/S0167-4838(98)00266-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Z., Jing T., Liu Z., Zhang L., Jin Z., Liu D., et al. (2015). H2S acting as a downstream signaling molecule of SA regulates Cd tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Soil 393 137–146. 10.1007/s11104-015-2475-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch T., Wachter A. (2005). Sulfur metabolism: a versatile platform for launching defence operations. Trends Plant Sci. 10 503–509. 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravilious G. E., Nguyen A., Francois J. A., Jez J. M. (2012). Structural basis and evolution of redox regulation in plant adenosine-5′-phosphosulfate kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 309–314. 10.1073/pnas.1115772108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero L. C., Aroca M. Á, Laureano-Marín A. M., Moreno I., García I., Gotor C. (2014). Cysteine and cysteine-related signaling pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 7 264–276. 10.1093/mp/sst168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A. (1976). The adenosine-5′-phosphosulfate sulfotransferase from spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). Stabilization, partial purification and properties. Planta 130 257–263. 10.1007/BF00387830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scuffi D., Álvarez C., Laspina N., Gotor C., Lamattina L., García-Mata C. (2014). Hydrogen sulfide generated by L-cysteine desulfhydrase acts upstream of nitric oxide to modulate abscisic acid-dependent stomatal closure. Plant Physiol. 166 2065–2076. 10.1104/pp.114.245373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Xing T., Yuan H., Liu Z., Jin Z., Zhang L., et al. (2013). Hydrogen sulfide improves drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana by microRNA expressions. PLoS One 8:e77047. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J. J., Qiao Z. J., Xing T. J., Zhang L. P., Liang Y. L., Jin Z. P., et al. (2012). Cadmium toxicity is alleviated by AtLCD and AtDCD in Escherichia coli. J. Appl. Microbiol. 113 1130–1138. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05408.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Ye T., Chan Z. (2014). Nitric oxide-activated hydrogen sulfide is essential for cadmium stress response in bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon (L). Pers.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 74 99–107. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Ye T., Han N., Bian H., Liu X., Chan Z. (2015). Hydrogen sulfide regulates abiotic stress tolerance and biotic stress resistance in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 57 628–640. 10.1111/jipb.12302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeekens S., Rook F. (1997). Sugar sensing and sugar-mediated signal transduction in plants. Plant Physiol. 115 7–13. 10.1104/pp.115.1.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Wang R., Zhang X., Yu Y., Zhao R., Li Z., et al. (2013). Hydrogen sulfide alleviates cadmium toxicity through regulations of cadmium transport across the plasma and vacuolar membranes in Populus euphratica cells. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 65 67–74. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsakraklides G., Martin M., Chalam R., Tarczynski M. C., Schmidt A., Leustek T. (2002). Sulfate reduction is increased in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana expressing 5′-adenylylsulfate reductase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Plant J. 32 879–889. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01477.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauclare P., Kopriva S., Fell D., Suter M., Sticher L., von Ballmoos P., et al. (2002). Flux control of sulphate assimilation in Arabidopsis thaliana: adenosine 5′-phosphosulphate reductase is more susceptible to negative control by thiols than ATP sulphurylase. Plant J. 31 729–740. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01391.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. (2012). Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: a whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiol. Rev. 92 791–896. 10.1152/physrev.00017.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Zhang C., Lai D., Sun Y., Samma M. K., Zhang J., et al. (2014). Hydrogen sulfide delays GA-triggered programmed cell death in wheat aleurone layers by the modulation of glutathione homeostasis and heme oxygenase-1 expression. J. Plant Physiol. 171 53–62. 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatusevich R., Mugford S. G., Matthewman C., Gigolashvili T., Frerigmann H., Delaney S., et al. (2010). Genes of primary sulfate assimilation are part of the glucosinolate biosynthetic network in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 62 1–11. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04118.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Hu L. Y., Hu K. D., He Y. D., Wang S. H., Luo J. P. (2008). Hydrogen sulfide promotes wheat seed germination and alleviates oxidative damage against copper stress. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 50 1518–1529. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00769.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Hu S. L., Zhang Z. J., Hu L. Y., Jiang C. X., Wei Z. J., et al. (2011). Hydrogen sulfide acts as a regulator of flower senescence in plants. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 60 251–257. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2011.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Tan Z. Q., Hu L. Y., Wang S. H., Luo J. P., Jones R. L. (2010). Hydrogen sulfide alleviates aluminum toxicity in germinating wheat seedlings. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52 556–567. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00946.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Tang J., Liu X. P., Wang Y., Yu W., Peng W. Y., et al. (2009). Hydrogen sulfide promotes root organogenesis in Ipomoea batatas, Salix matsudana and Glycine max. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 51 1086–1094. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2009.00885.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]