Abstract

Non-opioid pain management strategies are critically needed for people with HIV. We therefore conducted a secondary analysis of pain-related outcomes in a randomized controlled trial of a positive affect skills intervention for adults newly diagnosed with HIV (N = 159). Results suggest that, even if pain prevalence rises, positive affect skills may reduce pain interference and prevent increased use of opioid analgesics by people living with HIV. Future research should replicate and extend these findings by conducting trials that are specifically designed to target pain outcomes.

Keywords: affect, coping, HIV, intervention, pain

Introduction

Pain is prevalent in people with HIV, occurring at rates higher than in the general population (Merlin et al., 2014b; Parker et al., 2014). In particular, headaches, musculoskeletal disorders, and neuropathic pain are among the most common comorbidities and pain-related complaints in people with HIV, yet pain remains understudied in this population (Jiao et al., 2016; Kirkland et al., 2012; Parker et al., 2014). Pain in people with HIV is associated with depression, decreased functioning, increased healthcare utilization, and poorer physical and psychosocial quality of life (Jiao et al., 2016; Merlin et al., 2014a; Miaskowski et al., 2011; Uebelacker et al., 2015). Outcomes such as these are increasingly important, as HIV has become a chronic, rather than terminal, disease (Merlin et al., 2014b).

Treatment for pain in people with HIV is often ineffective, failing to diminish pain or improve functioning (Parker et al., 2014; Turk, 2002). In both the general population and specifically among people with HIV, opioid prescribing and misuse have increased dramatically in the past 25 years (Becker et al., 2016; Jordan et al., 2017). This is particularly problematic given that pain conditions are especially common in HIV patients with comorbid mental health and substance use concerns (Jiao et al., 2016; Merlin et al., 2014a). Paradoxically, opioids can exacerbate pain in people with HIV (Liu et al., 2016). High rates of comorbid renal and hepatic diseases in this population, as well as preclinical models of opioid-mediated HIV infection, generate additional medical contraindications for opioid-based pain management in HIV (Trafton et al., 2012). Despite the need for non-opioid strategies, evidence for alternative approaches is limited. In a recent review of non-opioid and non-pharmacologic interventions for pain in HIV, nearly all of the included trials were graded as very low or low quality, often because they were non-randomized or they failed to include intention-to-treat analyses or sufficient follow-up assessments (Merlin et al., 2016).

Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the US Department of Health and Human Services, and other leading organizations recognize psychosocial approaches as an essential component of pain management in any population (Dowell et al., 2016; Janke et al., 2017; National Pain Strategy, 2016). Given the complex setting of pain in HIV, psychosocial strategies may be especially critical for improving pain-related outcomes in people living with HIV. Calls for non-pharmacologic, biopsychosocial approaches to pain management in HIV have recently increased (Merlin et al., 2014b; Parker et al., 2014; Sheikh and Cho, 2014). However, trials of behavioral interventions in this population are scant (Merlin et al., 2016). The need for safe and effective pain management strategies for people with HIV therefore remains critical.

Behavioral interventions that increase positive affect, which encompasses a range of feelings such as happy, satisfied, calm, and excited, may be a valuable addition to HIV pain management. Independent of the effects of negative affect, positive affect is uniquely associated with better psychological and physical health outcomes (e.g. better relationships and reduced mortality, respectively) in healthy and chronically ill samples (Chida and Steptoe, 2008; Folkman, 1997; Folkman and Moskowitz, 2000; Fredrickson, 1998; Fredrickson et al., 2008; Moskowitz et al., 2008; Pressman and Cohen, 2005; Tice et al., 2007; Wichers et al., 2007; Zautra et al., 2005). Researchers, therefore, have begun to develop interventions to increase positive affect in people with a variety of chronic conditions, such as diabetes (Cohn et al., 2014; Huffman et al., 2015), cardiovascular disease (Huffman et al., 2011; Peterson et al., 2012), depression (Seligman et al., 2005), and substance abuse (Carrico et al., 2015; Krentzman et al., 2015).

A growing body of research demonstrates that positive affect specifically benefits pain-related outcomes. Evidence from studies of healthy participants and pain patients suggests that positive affect, independent of negative affect, can decrease pain severity, improve functional outcomes, buffer the relationship between pain and distress, and decrease maladaptive cognitive and behavioral patterns that exacerbate pain and contribute to its chronicity (Berges et al., 2011; Davis et al., 2014; Finan et al., 2013; Geschwind et al., 2015; Hamilton et al., 2005; Hanssen et al., 2013; Hirsch et al., 2016; Kenntner-Mabiala and Pauli, 2005; Meulders et al., 2014; Mun et al., 2015; Park and Sonty, 2010; Seebach et al., 2012; Strand et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2008; White et al., 2012; Zautra et al., 2005). Researchers have therefore called for the development of interventions that aim to improve pain-related outcomes by increasing positive psychological constructs such as positive affect (Finan and Garland, 2015; Kaiser et al., 2015; Keefe and Wren, 2013; Ong et al., 2015).

A few such interventions have been tested, providing preliminary support for feasibility and efficacy for improved psychological well-being among adults with chronic pain (Hausmann et al., 2014, 2017; Müller et al., 2016; Peters et al., 2017). However, results for pain-related outcomes have been mixed: Two positive psychology trials demonstrated significant improvements in pain intensity (Hausmann et al., 2014; Müller et al., 2016), but others failed to find evidence of decreased pain (Hausmann et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2017). In addition, research has not examined the effects of positive affect skills on pain-related outcomes in people living with HIV.

We previously developed a multicomponent, theory- and evidence-based, behavioral intervention to increase positive affect in people newly diagnosed with HIV (Moskowitz et al., 2017). Our Intervention for those Recently Informed of their Seropositive Status (IRISS) is grounded in revised Stress and Coping Theory (Folkman, 1997) and the Broaden-and-Build Theory of positive emotion (Fredrickson, 1998). These theories describe how positive affect stimulates and maintains effective coping, generates cognitive and behavioral flexibility, and builds psychological, intellectual, social, and physical resources, thereby facilitating psychological and physical health. Accordingly, IRISS was designed based on the evidence for widespread benefits of positive affect described above, as well as the specific benefits of positive affect for people with HIV, including decreased depression (Li et al., 2017), improved treatment adherence (Carrico and Moskowitz, 2014; Gonzalez et al., 2004), slower disease progression (Ironson and Hayward, 2008), increased likelihood of suppressed viral load (Wilson et al., 2017), and lower risk of mortality (Moskowitz, 2003). In primary analyses of the randomized controlled trial of IRISS (N = 159), we found significant effects of the intervention on both psychological and physical health outcomes (e.g. decreased intrusive/avoidant thoughts, use of antidepressants, and HIV symptom severity; (Moskowitz et al., 2017).

This study

In this brief report, we describe a series of secondary analyses to examine pain-related outcomes in the IRISS study. Our aim was to evaluate whether the positive affect skills intervention decreased pain prevalence, pain interference, and use of opioid analgesics. Given that previous studies of the relationship between positive affect and pain were inconclusive and none were conducted in people living with HIV, we approached these analyses as an exploratory study, without specific hypotheses for each of the outcome measures.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Full details of the methods of the randomized controlled trial of IRISS have been reported elsewhere (Moskowitz et al., 2017). Briefly, English- and Spanish-speaking adults (age > 18) diagnosed with HIV within the past 12 weeks were recruited from HIV clinics and other community-based sites in the San Francisco Bay area. Participants were randomized to receive IRISS or a time- and attention-matched control. Both groups received five weekly in-person individual sessions with a facilitator and a sixth session conducted by telephone. IRISS participants received instruction and practice in eight positive affect skills (i.e. noticing and capitalizing on positive events, gratitude, mindfulness, positive reappraisal, personal strengths, goal attainment, and acts of kindness), while the control group participated in supportive personal interviews on topics such as life history, health history, and personality. Blinded interviewers conducted assessments at baseline, immediately post-intervention (5 months post-diagnosis), and 5- and 10-month follow-up (10 and 15 months post-diagnosis, respectively).

This secondary data analysis focuses on pain-related outcomes contained within the HIV symptom index developed by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (Justice et al., 2001) and the self-reported alcohol/drug use scale developed for this study. Relevant items within these measures assess pain prevalence (experience of headaches, musculoskeletal pain (“muscle aches or joint pain”), or peripheral neuropathy (“pain, numbness or tingling in the hands or feet”) in the past 30 days (yes/no)), interference (rated separately for each of the three pain symptoms: 1 = It doesn’t bother me at all to 4 = It bothers me a great deal); and use of opioid analgesics (yes/no). The Institutional Review Board at institutions where data were collected approved all procedures and participants provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki and registered with clinicaltrials.gov (#NCT00720733).

Data analysis

We compared the intervention and control groups at baseline using t-test and chi-square analyses. Primary analyses focused on between-group differences in change from baseline. In intention-to-treat analyses, we used longitudinal growth models (mixed effect models (MIXED)) for continuous outcomes (Singer and Willett, 2003); generalized estimating equations (GEE) for categorical outcomes (Zeger et al., 1988)) to test for differential patterns of change over time in the intervention versus control group. These models provide several advantages over traditional methods of repeated measures analysis (e.g. allowing for missing data, variations in timing of data collection, and non-independence of observations) and yield estimates that represent the differences between the intervention and control condition in the magnitude of change over time, as modeled by the differences in slopes between the two groups. When mode-ling each of the interference outcomes, we only included data from participants who reported having the corresponding pain symptom at that assessment (e.g. when modeling the effects of the intervention on headache interference, we included only those participants who reported having headaches).

We then calculated effect sizes (Cohen’s d) that represent the mean differences in change between the interventions relative to the control group from baseline to each assessment point. For dichotomous (yes/no) outcome variables, we converted odds ratios to effect sizes (d) for ease of interpretation across outcome variables (Borenstein et al., 2009). Positive effect sizes indicate that the intervention group, compared to the control group, showed greater increases (or smaller decreases) from baseline to that assessment point, while negative effect sizes indicate that the intervention group, compared to the control group, showed greater decreases (or smaller increases).

Results

As shown in Table 1 and previously described in more detail (Moskowitz et al., 2017), most participants (N = 159) were male and gay/bisexual. All were enrolled within 12 weeks of HIV diagnosis. Intervention (n = 80) and control (n = 79) groups did not significantly differ at baseline on any demographic variables, time since diagnosis, or pain-related outcomes.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 159).

| n (%) | M (SD), range | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 144 (92) | |

| Female | 11 (7) | |

| Transgender, male to female | 2 (1) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Asian/Pacific | 12 (8) | |

| Islander | ||

| Black | 31 (21) | |

| Latino | 31 (21) | |

| White | 65 (45) | |

| Other | 7 (5) | |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Gay/bisexual | 132 (84) | |

| Heterosexual | 19 (12) | |

| Other | 6 (4) | |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 90 (58) | |

| Some college or college graduate | 35 (22) | |

| Graduate school/degree | 32 (20) | |

| Annual household income | ||

| <10 K | 46 (31) | |

| 10–30 K | 36 (24) | |

| 30–60 K | 34 (23) | |

| 60–90 K | 13 (9) | |

| >90 K | 20 (13) | |

| Age (years) | 36.0 (9.9), 18–60 | |

| Time since HIV diagnosis (days) | 61.6 (27.7), 9–121 |

SD: standard deviation.

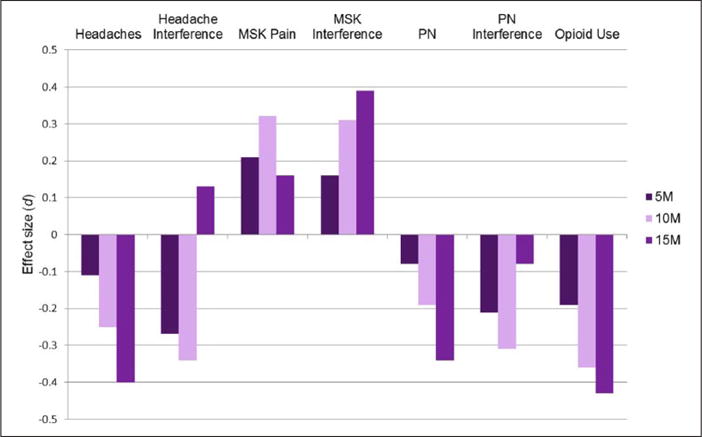

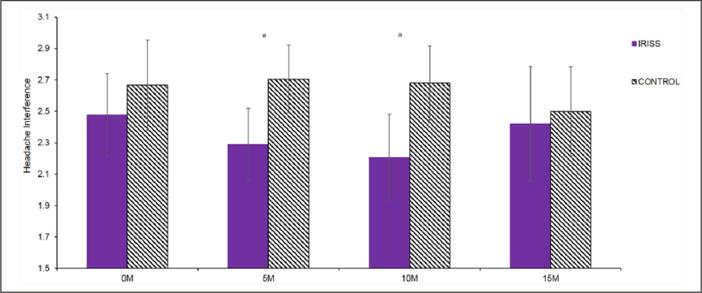

For all pain-related outcomes, Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and results for overall effect of condition by time, while Figure 1 presents effect sizes for between-group differences in change from baseline to each assessment. Prevalence of headaches was equivalent across groups at all assessments and there were no significant group differences in change over time. Nonetheless, among those experiencing headaches, longitudinal mixed effect models revealed a significant quadratic effect (p = .05) of the intervention on headache interference over time (Figure 2). Between-group differences in change from baseline were statistically significant, with the intervention group reporting significantly less headache-related interference than the control group at post-intervention and 10-month follow-up; effect sizes at each time point were small (d = −.27 and d = −.34, respectively). By 15 months, headache interference began to converge, such that the groups did not significantly differ at the final assessment.

Table 2.

Intervention effects on pain-related outcomes

| Baseline (n = 159) M (SE) |

5 months (n = 120) M (SE) |

10 months (n = 97) M (SE) |

15 months (n = 114) M (SE) |

Overall effect Condition × Time (β11) Condition × Time × Time (β21) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Headaches (%yes) | |||||

| IRISS | 41.0% (5%) | 44.9% (5%) | 46.8% (6%) | 42.5% (7%) | β11 = −.06, χ2 = 0.96, p = .33 |

| Control | 31.9% (5%) | 40.3% (5%) | 48.3% (6%) | 50.9% (7%) | β21 = .001, χ2 = 0.06, p = .80 |

| Headache interference | |||||

| IRISS | 2.48 (.14) | 2.29 (.12)a | 2.21 (.14)a | 2.42 (.19) | β11 = −.08, t(178) = −1.64, p = .10 |

| Control | 2.67 (.15) | 2.71 (.11) | 2.68 (.12) | 2.50 (.15) | β21 = .01, t(187) = 1.97, p = .05 |

| MSK pain (% yes) | |||||

| IRISS | 37.6% (5%) | 49.3% (5%) | 57.4% (5%)a | 52.9% (7%) | β11 = .12, χ2 = 4.12, p = .04 |

| Control | 37.6% (5%) | 40.2% (4%) | 43.3% (5%) | 45.9% (6%) | β21 = −.006, χ2 = 4.39, p = .04 |

| MSK pain interference | |||||

| IRISS | 2.40 (.14) | 2.39 (.11) | 2.36 (.13) | 2.31 (.18) | β11 = .04, t(178) = −0.88, p = .38 |

| Control | 2.54 (.11) | 2.71 (.11) | 2.38 (.12) | 2.26 (.15) | β21 = −.001, t(177) = 0.49, p = .62 |

| PN (% yes) | |||||

| IRISS | 37.3% (5%) | 42.7% (5%) | 46.4% (6%) | 43.7% (7%) | β11 = −.035, χ2 = 0.43, p = .51 |

| Control | 25.1% (5%) | 32.6% (5%) | 40.6% (5%) | 44.8% (7%) | β21 = .001, χ2 = 0.01, p = .94 |

| PN interference | |||||

| IRISS | 2.50 (.15) | 2.33 (.12) | 2.21 (.14) | 2.27 (.19) | β11 = .067, t(159) = 1.24, p = .22 |

| Control | 2.53 (.17) | 2.56 (.12) | 2.54 (.13) | 2.38 (.16) | β21 = −.004, t(161) = −1.29, p = .20 |

| Opioid use (%yes) | |||||

| IRISS | 17.4% (4%) | 15.7% (3%) | 14.6% (3%)a | 15.5% (5%)a | β11 = −.10, χ2 = 3.14, p = .08 |

| Control | 18.2% (4%) | 21.6% (4%) | 25.8% (4%) | 29.7% (6%) | β21 = .003, χ2 = 2.90, p = .09 |

SE: standard error; IRISS: Intervention for those Recently Informed of their Seropositive Status; MSK: musculoskeletal; PN: peripheral neuropathy.

Statistically significant (p ≤ .05) between-group differences within each time point.

Figure 1.

Effect sizes (d) for between-group differences in change pain-related outcomes from baseline to each assessment.

M: months; MSK: musculoskeletal; PN: peripheral neuropathy.

Positive effect sizes indicate that the intervention group showed greater increases (or small decreases) from baseline to that assessment point, while negative effect sizes indicate that the intervention group compared to the control group showed greater decreases (or smaller increases).

Figure 2.

Change in headache-related interference over time.

IRISS: Intervention for those Recently Informed of their Seropositive Status; M: months.

aStatistically significant (p ≤ .05) between-group differences within each time point.

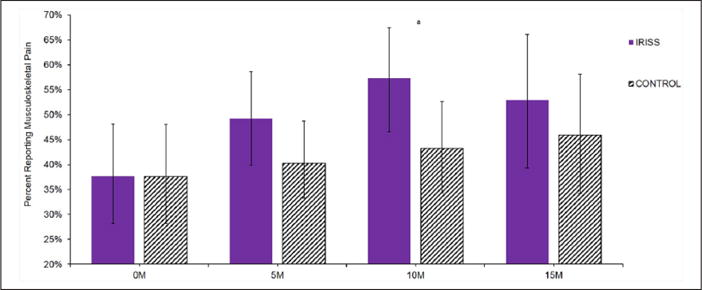

For musculoskeletal pain, there were significant group differences in change over time (linear: p = .04; quadratic: p = .04; Table 2). By the 10-month follow-up assessment, prevalence of musculoskeletal pain was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group (Figure 3) and the effect size was small (d = .32; Figure 2). At the final assessment, the groups converged such that the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain no longer differed significantly between IRISS and control participants. Despite the differences in prevalence over time, levels of musculoskeletal pain interference did not significantly change over time, nor were there significant between-group differences at any time point (Table 2). There were no significant effects for any of the analyses related to peripheral neuropathy (prevalence or interference; all p values > .05, Table 2).

Figure 3.

Change in prevalence of musculoskeletal pain over time.

IRISS: Intervention for those Recently Informed of their Seropositive Status; M: months.

aStatistically significant (p ≤ .05) between-group differences within each time point.

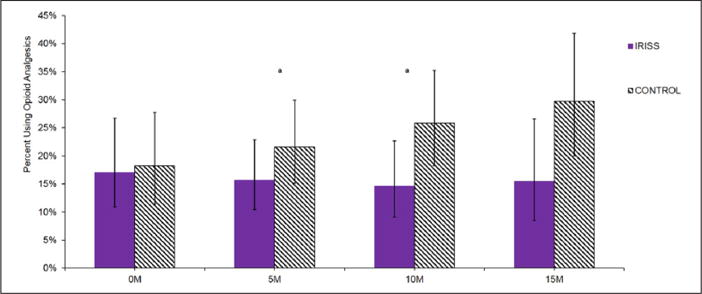

Figure 4 shows group trends in opioid analgesic use over time. Although group differences in change from baseline did not reach statistical significance (linear: p = .08; quadratic: p = .09), rates of opioid analgesic use were higher in the control group compared to the intervention group at both the 10- and 15-month assessments (Table 2). Effect sizes for the between-group difference in change from baseline to the 10-and 15-month assessments were moderate: d = −.36 and d = −.43, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 4.

Change in prevalence of opioid analgesic use over time.

IRISS: Intervention for those Recently Informed of their Seropositive Status; M: months.

aStatistically significant (p ≤ .05) between-group differences within each time point.

Discussion

Among people with HIV, rates of pain are elevated (Merlin et al., 2014b; Parker et al., 2014), while opioid misuse is widespread and has particularly deleterious consequences (Becker et al., 2016; Jordan et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2016; Trafton et al., 2012). Results of this secondary data analysis from the IRISS study suggest that, even if pain prevalence rises, people living with HIV who learn skills for increasing positive affect may be better equipped to cope with comorbid pain and to refrain from using opioid analgesics. Effect sizes were small to moderate and tended to increase over time. Because we encouraged participants to incorporate the skills into their daily lives, the effects of the intervention may strengthen over time as participants’ use of the skills becomes more frequent and proficient (Moskowitz et al., 2017).

Despite these important benefits, findings were inconclusive, as is consistent with prior research in non-HIV samples (Hausmann et al.,2014, 2017; Müller et al., 2016; Peters et al., 2017). Results of the longitudinal models for several outcomes, including both measures related to peripheral neuropathy, were nonsignificant. Even when outcomes did not reach statistical significance, results typically favored the intervention—with the exception of musculoskeletal pain. Why IRISS would conversely affect only musculoskeletal pain prevalence is unclear. One possibility is that the mindfulness portion of the intervention increased awareness of this broad category of pain, while other intervention components ameliorated coping, resulting in increased reports of musculoskeletal pain prevalence without increased interference. Pain can be characterized according to various physiologic mechanisms (i.e. nociceptive, peripheral neuropathic, and centralized; Clauw, 2015), which may be differentially affected by cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes (Garland, 2012). Additional research is needed to understand the specific psychophysiology underlying the relationships between positive affect skills and a variety of pain-related outcomes, including in people with HIV.

In addition, methodological limitations likely contributed to the inconsistent pattern of results in this secondary analysis. IRISS was not designed to improve or evaluate pain. Accordingly, we did not administer robust measures of pain-related outcomes. For example, we did not collect detailed information on pain frequency or severity. We also did not assess how or for what condition opioids were obtained, nor can we distinguish appropriate use of opioid analgesics from misuse/abuse in this sample. Future studies will need to adapt the positive affect skills to directly target coping with pain and use well-validated measures of pain-related outcomes and drug use/abuse.

Future trials should also measure potential mediators of the effect of positive affect on pain, such as decreased pain catastrophizing (Hood et al., 2012; Sturgeon and Zautra, 2013). Pain catastrophizing involves intense, negative attention to and expectations about pain (Sullivan et al., 1995). Conversely, positive affect skills broaden attention and decrease threat-based appraisals (Folkman, 1997; Fredrickson, 1998). Cognitive factors such as this may help to explain why the IRISS-positive affect skills demonstrated a protective effect on participants’ evaluations of their pain symptoms (i.e. decreased headache interference in IRISS vs control; and equivalent interference despite increased prevalence of musculoskeletal pain in IRISS vs control).

Studies designed to investigate the effect of positive affect skills on pain management in HIV should additionally consider the sample and the timing of the intervention. The IRISS study restricted eligibility to people newly diagnosed with HIV, and consistent with the population of people newly diagnosed with HIV in the San Francisco Bay area, enrolled primarily men. However, pain prevalence increases with time since HIV diagnosis (Lawson et al., 2014) and pain tends to be more severe in females rather than males with HIV (Miaskowski et al., 2011). Pain-related outcomes therefore should be evaluated in trials that enroll more women and people who are more than 12 weeks post-HIV diagnosis.

Despite the limitations of this study, one of its strengths is the high level of participant adherence, which has been problematic in prior studies of behavioral pain management interventions in HIV. For example, adherence to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for pain management in people with HIV was below 50 percent and was significantly poorer among CBT versus control group participants (Cucciare et al., 2009; Evans et al., 2003; Trafton et al., 2012). Conversely, among the 80 participants randomized to the intervention condition in our study, 77 percent completed all six IRISS sessions (Moskowitz et al., 2017). Thus, our positive affect skills intervention has demonstrated an exceptionally high level of acceptability among people living with HIV, significant benefits for primary psychological and physical health outcomes (Moskowitz et al., 2017), and the potential to improve pain management.

Conclusion

Comorbid pain conditions are pervasive in people living with HIV and are a primary threat to their quality of life, yet research and safe effective treatments remain scant (Jiao et al., 2016; Kirkland et al., 2012; Merlin et al., 2014a, 2014b; Miaskowski et al., 2011; Parker et al., 2014; Turk, 2002; Uebelacker et al., 2015). As a result, behavioral interventions based in positive psychology are a novel and important direction for non-pharmacologic pain management (Kaiser et al., 2015). This secondary data analysis provides initial support for the efficacy of positive affect skills intervention to improve pain management in people living with HIV. Results should be replicated and expanded in future trials designed to target pain outcomes. If these more rigorous trials further demonstrate that positive affect skills alleviate pain, decrease pain interference, and reduce opioid use, then this theory- and evidence-based intervention may contribute to improving public health outcomes that are especially important in the context of rampant opioid misuse nationally and the complex landscape of managing pain in people with HIV (Becker et al., 2016; Jordan et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2016; Trafton et al., 2012).

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health [R01 MH084723, K24 MH093225], the National Cancer Institute [T32 CA193193], the Third Coast Center for AIDS Research [CFAR P30 AI117943], and the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding sponsors.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Elizabeth L Addington https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5839-5485

References

- Becker WC, Gordon K, Jennifer Edelman E, et al. Trends in any and high-dose opioid analgesic receipt among aging patients with and without HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2016;20(3):679–686. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1197-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berges I-M, Seale G, Ostir GV. Positive affect and pain ratings in persons with stroke. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2011;56(1):52–57. doi: 10.1037/a0022683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, et al. Converting among effect sizes. In: Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR, editors. Introduction to Meta-analysis. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Moskowitz JT. Positive affect promotes engagement in care after HIV diagnosis. Health Psychology. 2014;33(7):686–689. doi: 10.1037/hea0000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Gómez W, Siever MD, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of an integrative intervention with methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015;44(7):1861–1867. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0505-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: A quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(7):741–756. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauw DJ. Diagnosing and treating chronic musculoskeletal pain based on the underlying mechanism(s) Best Practice & Research in Clinical Rheumatology. 2015;29(1):6–19. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2015.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn MA, Pietrucha ME, Saslow LR, et al. An online positive affect skills intervention reduces depression in adults with type 2 diabetes. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2014;9(6):523–534. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.920410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucciare MA, Sorrell JT, Trafton JA. Predicting response to cognitive-behavioral therapy in a sample of HIV-positive patients with chronic pain. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(4):340–348. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MC, Thummala K, Zautra AJ. Stress-related clinical pain and mood in women with chronic pain: Moderating effects of depression and positive mood induction. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;48(1):61–70. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9583-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recommendations and Reports: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Recommendations and Reports. 2016;65(1):1–49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S, Fishman B, Spielman L, et al. Randomized trial of cognitive behavior therapy versus supportive psychotherapy for HIV-related peripheral neuropathic pain. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(1):44–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan PH, Garland EL. The role of positive affect in pain and its treatment. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2015;31(2):177–187. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan PH, Quartana PJ, Smith MT. Positive and negative affect dimensions in chronic knee osteoarthritis: Effects on clinical and laboratory pain. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2013;75(5):463–470. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31828ef1d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;45(8):1207–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist. 2000;55(6):647–654. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology: Journal of Division 1, of the American Psychological Association. 1998;12(3):300–319. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Cohn MA, Coffey KA, et al. Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95(5):1045–1062. doi: 10.1037/a0013262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL. Pain processing in the human nervous system: A selective review of nociceptive and biobehavioral pathways. Primary Care. 2012;39(3):561–571. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geschwind N, Meulders M, Peters ML, et al. Can experimentally induced positive affect attenuate generalization of fear of movement-related pain? The Journal of Pain. 2015;16(3):258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Penedo FJ, Antoni MH, et al. Social support, positive states of mind, and HIV treatment adherence in men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Health Psychology. 2004;23(4):413–418. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton NA, Zautra AJ, Reich JW. Affect and pain in rheumatoid arthritis: Do individual differences in affective regulation and affective intensity predict emotional recovery from pain? Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;29(3):216–224. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2903_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen MM, Peters ML, Vlaeyen JWS, et al. Optimism lowers pain: Evidence of the causal status and underlying mechanisms. Pain. 2013;154(1):53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann LRM, Parks A, Youk AO, et al. Reduction of bodily pain in response to an online positive activities intervention. The Journal of Pain: Official Journal of the American Pain Society. 2014;15(5):560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann LRM, Youk A, Kwoh CK, et al. Testing a positive psychological intervention for osteoarthritis. Pain Medicine. 2017;18(10):1908–1920. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnx141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JK, Sirois FM, Molnar D, et al. Pain and depressive symptoms in primary care: Moderating role of positive and negative affect. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2016;32(7):562–567. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood A, Pulvers K, Carrillo J, et al. Positive traits linked to less pain through lower pain catastrophizing. Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;52(3):401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JC, DuBois CM, Millstein RA, et al. Positive psychological interventions for patients with type 2 diabetes: Rationale, theoretical model, and intervention development. Journal of Diabetes Research. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/428349. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4442018/ (accessed 14 December, 2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Huffman JC, Mastromauro CA, Boehm JK, et al. Development of a positive psychology intervention for patients with acute cardiovascular disease. Heart International. 2011;6(2) doi: 10.4081/hi.2011.e14. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3699107/ (accessed 14 December, 2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Hayward H. Do positive psychosocial factors predict disease progression in HIV-1? A review of the evidence. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(5):546–554. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318177216c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke EA, Cheatle MD, Keefe FJ, et al. Improving access to psychosocial care for individuals with persistent pain: Supporting the national pain strategy call for interdisciplinary pain care. Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2017 doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibx043. Available at: http://www.sbm.org/UserFiles/file/pain-statement_v7_lores.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jiao JM, So E, Jebakumar J, et al. Chronic pain disorders in HIV primary care: Clinical characteristics and association with healthcare utilization. Pain. 2016;157(4):931–937. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan AE, Blackburn NA, Des Jarlais DC, et al. Past-year prevalence of prescription opioid misuse among those 11 to 30 years of age in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2017;77:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AC, Holmes W, Gifford AL, et al. Development and validation of a self-completed HIV symptom index (HIV Infection as a Chronic Disease: Understanding the Roles of Aging, Drug Toxicity, and Comorbidity) Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2001;54(Suppl. 1):S77–S90. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser RS, Mooreville M, Kannan K. Psychological interventions for the management of chronic pain: A review of current evidence. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2015;19(9):43. doi: 10.1007/s11916-015-0517-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe FJ, Wren AA. Optimism and pain: A positive move forward. Pain. 2013;154(1):7–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenntner-Mabiala R, Pauli P. Affective modulation of brain potentials to painful and nonpainful stimuli. Psychophysiology. 2005;42(5):559–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland KE, Kirkland K, Many WJ, et al. Headache among patients with HIV disease: Prevalence, characteristics, and associations. Headache. 2012;52(3):455–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krentzman AR, Mannella KA, Hassett AL, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and impact of a web-based gratitude exercise among individuals in outpatient treatment for alcohol use disorder. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2015;10(6):477–488. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1015158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson E, Sabin C, Perry N, et al. Is HIV painful? An epidemiologic study of the prevalence and risk factors for pain in HIV-infected patients. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2014 doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000162. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5053359/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li J, Mo PKH, Wu AMS, et al. Roles of self-stigma, social support, and positive and negative affects as determinants of depressive symptoms among HIV infected men who have sex with men in china. AIDS and Behavior. 2017;21(1):261–273. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1321-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Liu X, Tang S-J. Interactions of opioids and HIV infection in the pathogenesis of chronic pain. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2016;7:103. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin JS, Bulls HW, Vucovich LA, et al. Pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments for chronic pain in individuals with HIV: A systematic review. AIDS Care. 2016;28(12):1506–1515. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1191612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin JS, Walcott M, Ritchie C, et al. “Two pains together”: Patient perspectives on psychological aspects of chronic pain while living with HIV. PloS ONE. 2014a;9(11):e111765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin JS, Zinski A, Norton WE, et al. A conceptual framework for understanding chronic pain in patients with HIV. Pain Practice. 2014b;14(3):207–216. doi: 10.1111/papr.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulders A, Meulders M, Vlaeyen JWS. Positive affect protects against deficient safety learning during extinction of fear of movement-related pain in healthy individuals scoring relatively high on trait anxiety. The Journal of Pain. 2014;15(6):632–644. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C, Penko JM, Guzman D, et al. Occurrence and characteristics of chronic pain in a community-based cohort of indigent adults living with HIV infection. The Journal of Pain. 2011;12(9):1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz JT. Positive affect predicts lower risk of AIDS mortality. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65(4):620–626. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000073873.74829.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz JT, Epel ES, Acree M. Positive affect uniquely predicts lower risk of mortality in people with diabetes. Health Psychology. 2008;27(Suppl. 1):S73–S82. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz JT, Carrico AW, Duncan LG, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a positive affect intervention for people newly diagnosed with HIV. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2017 doi: 10.1037/ccp0000188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller R, Gertz KJ, Molton IR, et al. Effects of a tailored positive psychology intervention on well-being and pain in individuals with chronic pain and a physical disability: A feasibility trial. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2016;32(1):32–44. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun CJ, Karoly P, Okun MA. Effects of daily pain intensity, positive affect, and individual differences in pain acceptance on work goal interference and progress. Pain. 2015;156(11):2276–2285. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Pain Strategy. The office of the assistant secretary for health. U.S Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. Available at: https://iprcc.nih.gov/National_Pain_Strategy/NPS_Main.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Zautra AJ, Reid MC. Chronic pain and the adaptive significance of positive emotions. The American Psychologist. 2015;70(3):283–284. doi: 10.1037/a0038816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Sonty N. Positive affect mediates the relationship between pain-related coping efficacy and interference in social functioning. The Journal of Pain. 2010;11(12):1267–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Stein DJ, Jelsma J. Pain in people living with HIV/AIDS: A systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17:18719. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters ML, Smeets E, Feijge M, et al. Happy despite pain: A randomized controlled trial of an 8-week internet-delivered positive psychology intervention for enhancing well-being in patients with chronic pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2017;33(11):962–975. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JC, Charlson ME, Hoffman Z, et al. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect induction to promote physical activity after per-cutaneous coronary intervention. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012;172(4):329–336. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(6):925–971. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seebach CL, Kirkhart M, Lating JM, et al. Examining the role of positive and negative affect in recovery from spine surgery. Pain. 2012;153(3):518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Steen TA, Park N, et al. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. The American Psychologist. 2005;60(5):410–421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh HU, Cho TA. Clinical aspects of headache in HIV. Headache. 2014;54(5):939–945. doi: 10.1111/head.12357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Strand EB, Zautra AJ, Thoresen M, et al. Positive affect as a factor of resilience in the pain-negative affect relationship in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;60(5):477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgeon JA, Zautra AJ. Psychological resilience, pain catastrophizing, and positive emotions: Perspectives on comprehensive modeling of individual pain adaptation. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2013;17(3):317. doi: 10.1007/s11916-012-0317-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: Development and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(4):524–532. [Google Scholar]

- Tang NKY, Salkovskis PM, Hodges A, et al. Effects of mood on pain responses and pain tolerance: An experimental study in chronic back pain patients. Pain. 2008;138(2):392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice DM, Baumeister RF, Shmueli D, et al. Restoring the self: Positive affect helps improve self-regulation following ego depletion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2007;43(3):379–384. [Google Scholar]

- Trafton JA, Sorrell JT, Holodniy M, et al. Outcomes associated with a cognitive-behavioral chronic pain management program implemented in three public HIV primary care clinics. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2012;39(2):158–173. doi: 10.1007/s11414-011-9254-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk DC. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatments for patients with chronic pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2002;18(6):355–365. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uebelacker LA, Weisberg RB, Herman DS, et al. Chronic pain in HIV-infected patients: Relationship to depression, substance use, and mental health and pain treatment. Pain Medicine. 2015;16(10):1870–1881. doi: 10.1111/pme.12799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DK, Keysor JJ, Neogi T, et al. When it hurts, a positive attitude may help: Association of positive affect with daily walking in knee osteoarthritis. Results from a multicenter longitudinal cohort study. Arthritis Care & Research. 2012;64(9):1312–1319. doi: 10.1002/acr.21694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichers MC, Myin-Germeys I, Jacobs N, et al. Evidence that moment-to-moment variation in positive emotions buffer genetic risk for depression: A momentary assessment twin study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2007;115(6):451–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TE, Weedon J, Cohen MH, et al. Positive affect and its association with viral control among women with HIV infection. Health Psychology. 2017;36(1):91–100. doi: 10.1037/hea0000382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Johnson LM, Davis MC. Positive affect as a source of resilience for women in chronic pain. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(2):212–220. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang K-Y, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: A generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(4):1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]