Abstract

Population-based data investigating generational differences in the risk of incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) and its risk determinants are rare. We examined the 6-year incidence of CVD and its risk factors in first- and second-generation ethnic Indians living in Singapore. 1749 participants (mean age [SD]: 55.5 [8.8] years; 47.5% male) from a population-based, longitudinal study of Indian adults were included for incident CVD outcome. Incident CVD was defined as self-reported myocardial infarction, angina pectoris or stroke which developed between baseline and follow-up. CVD-related risk factors included incident diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity and chronic kidney disease (CKD). For incident CVD outcome, of the 1749 participants, 406 (23.2%) and 1343 (76.8%) were first and second-generation Indians, respectively. Of these, 73 (4.1%) reported incident CVD. In multivariable models, second-generation individuals had increased risk of developing CVD (RR = 2.04; 95% CI 1.04, 3.99; p = 0.038), hyperlipidemia (RR = 1.27; 95% CI 1.06, 1.53; p = 0.011), and CKD (RR = 1.92; 95% CI 1.22, 3.04; p = 0.005), compared to first-generation Indians. Second-generation Indians have increased risk of developing CVD and its associated risk factors such as hyperlipidemia and CKD compared to first-generation immigrants, independent of traditional CVD risk factors. More stratified and tailored CVD prevention strategies on second and subsequent generations of Indian immigrants in Singapore are warranted.

Introduction

Previous research has shown that cardiovascular disease (CVD), which accounts for approximately 31% of global mortality rates1, is affected by environmental, lifestyle and risk factors such as obesity and physical inactivity2–4. It has been hypothesized that acculturation (the process of adaptation and exchange of behavior patterns to the principal culture in the new country) accelerates these factors5–8, corroborated by research showing that individuals migrating to a new country have suboptimal lifestyle profiles such as sedentariness9, and a high consumption of energy dense food10–12, compared to those in the home country, leading to dysfunctional metabolic states including obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, culminating in an increased risk of CVD13–15.

While cross-sectional studies have reported higher CVD risk and poor cardiovascular profiles in more acculturated second-generation (born in host country) individuals compared to less acculturated foreign-born immigrants16–23, the observed generational variations do not provide an estimate of the “true” generational effect on health, as they may be confounded by secular trends in the health of immigrants. Currently, longitudinal data on the impact of generational changes on the incidence of CVD and its risk factors in immigrant populations, particularly from Asian cultures, are rare. It is possible that the impact of acculturation on the incidence of CVD and its risk factors differs in Asian compared to Western populations due to differences in healthcare systems and lifestyle, cultural, religious and environmental habits, as well as differences in the way that people perceive and cope with illness and disease24,25. Addressing this knowledge gap can inform the temporal relationship between generational status and the development of CVD and its risk determinants, and health care agencies likely to target second-generation individuals in their prevention towards development of CVD and its risk determinants.

Such information is particularly important for Asian Indians who is one of the fastest growing immigrant groups across Asia and the world26. Singapore is a major migration destination, with Indian immigrants accounting for ~10% of Singapore’s total population27,28. As such, the Singapore population is ideal to study generational differences in chronic diseases including CVD.

In this study, we evaluated the 6-year incidence of CVD and its risk factors between first- and second-generation Indians in Singapore. We hypothesize that second-generation Indians will have a higher incidence of CVD and its risk predictors than first-generation immigrants. Findings from this study may potentially inform how nativity is related to change in cardiovascular health over time, and advise generation specific interventions to reduced future CVD risk.

Methods

Study Population and Design

The Singapore Indian Eye Study (SINDI-1 and -2) is a population-based cohort study of Indian adults (aged 40–80 years) living in Singapore, with baseline and follow-up assessments conducted between 2007 and 201529,30. Briefly, from a list of 12,000 individuals living in south-western Singapore, an age-stratified random sampling method selected 6350 names, of which 4168 were eligible. A total of 3400 (75.6% response rate) participated in SINDI-1. After 6-years, 486 (14.2%) of the initial subjects were ineligible to participate in SINDI-2 due to cognitive and/or severe mobility impairments, migration to other countries, or death during the intervening 6-years. Of the remaining 2914 eligible participants, 2200 (75.5% response rate) participated in SINDI-2.

The study was conducted at the research clinic of the Singapore Eye Research Institute (SERI). The protocol included a comprehensive, standardized examination as well as a questionnaire administered by interviewers trained to collect clinical and socio-demographic data, as described previously29,30. All protocols followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethics approval by the SingHealth Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent from participants was obtained prior to participation in the study. Data can be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

Definition of Immigrant Status

Each participant’s ethnicity was confirmed by using data from the Singapore national identity card. Each was categorized as “first-generation Indian” if he/she was born in India or Indian subcontinent, irrespective of the country of birth of their parents; or “second-generation Indian” if born in Singapore or Malaysia, irrespective of the country of birth of their parents.

Assessment of CVD

CVD information was collected using an interview-based, standardized questionnaire at the baseline and follow-up examinations. CVD was defined as a participant’s self-reported history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, or stroke, similar to previous epidemiologic studies conducted by our group31. Incidence of CVD was defined as no CVD at baseline examination but present at follow-up. We performed a reliability assessment of our self-reported CVD outcome and found that 75.5% of those who reported a history of CVD at baseline confirmed this information in the follow-up examination as reported elsewhere31.

Assessment of CVD Risk Factors

Socio-demographic characteristics (educational level, income level, occupation), lifestyle factors (e.g. smoking, alcohol consumption), self-reported family and medical history (e.g. diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and CVD), and current medications were obtained by trained interviewers through interviews.

Clinical covariates were obtained through a standardized clinical examination. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP) measurements were taken 2 times (a third if needed) using a digital BP monitor (Dinamap Pro Series DP110X-RW; GE Medical Systems Information Technologies, Inc). The average value of the two closest values for each parameter was utilized in analyses. Height and weight were measured using a wall-mounted adjustable measuring scale and a calibrated scientific weight scale, respectively. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2), and obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2.

Non-fasting venous blood samples were collected to assess levels of glucose, haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), serum creatinine, serum total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides. All samples were analyzed at the Singapore General Hospital Hematology Laboratory.

Diabetes was defined as a random glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (≥48 mmol/moL), self-reported use of diabetic medication, or history of physician-diagnosed diabetes32; hypertension as SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg, DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg, physician’s diagnosis, or use of anti-hypertensive medication33; hyperlipidemia as total cholesterol ≥6.2 mmol/L or use of lipid lowering drugs and chronic kidney disease (CKD) as having an estimated glomerular filtration rate of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 34,35. For the incident CVD risk factor analysis, incidence of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity and CKD was defined as absent at baseline examination, but present at follow-up.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using Stata version 14.2 (Statacorp, Lake Station, TX, USA). Baseline characteristics of participants by immigration status (first versus second-generation), and participants who returned and did not return for follow-up were compared using the χ2 statistic for proportions for categorical variables, and a t test for continuous variables. The Mann-Whitney U test was performed if the distribution of a continuous variable was highly skewed. (Tables 1 and 2, respectively). Modified Poisson regression was used to determine whether immigrant status was independently associated with development of CVD and its risk factors (Tables 3 and 4, respectively). Models were adjusted for participant characteristics that were either significantly different between generations at baseline or have been previously found to be associated with CVD and its risk factors. For each CVD condition in question, we also mutually adjusted for the other CVD conditions to check for an independent effect of that condition. Key covariates included age, gender, obesity, socioeconomic status (SES; including education [≤6 years/>6 years], income [<SG$2000/≥ SG$2000] and housing [≤3–4 room/> 3–4 room]), smoking status, alcohol and medication use (including anti diabetic, hypertensive or lipid lowering), and presence of comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and CKD. Relative risks (RR) were reported with 95 percent confidence intervals (CI), and a two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was judged statistically significant.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of participants by generation status in SINDI (N = 1749#).

| Variable | Mean (SD) or Number (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Generation (n = 406) | 2nd Generation (n = 1343) | P value* | |

| Age, years | 58.1 (10.2) | 54.8 (8.2) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay in Singapore, years | 35.3 (17.0) | 52.1 (9.8) | <0.001 |

| Gender, Male | 212 (52.2) | 621 (46.2) | 0.035 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 52 (12.8) | 241 (17.9) | 0.015 |

| Low socioeconomic status | 161 (39.7) | 646 (48.1) | 0.003 |

| Current smoker | 30 (7.4) | 189 (14.1) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol drinker | 43 (10.6) | 173 (12.9) | 0.219 |

| Diabetes | 141 (34.7) | 454 (33.8) | 0.731 |

| Hypertension | 223 (54.9) | 687 (51.2) | 0.182 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 157 (38.7) | 583 (43.4) | 0.090 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 22 (5.4) | 61 (4.5) | 0.467 |

| Anti-diabetic medication use | 104 (25.6) | 292 (21.7) | 0.102 |

| Anti-hypertensive medication use | 137 (33.7) | 389 (29.0) | 0.066 |

| Anti-cholesterol medication use | 111 (27.3) | 322 (24.0) | 0.169 |

*Mann-Whitney U test or chi-squared test.

#1749 individuals had no CVD at baseline, had complete data for all baseline characteristics including generation status and returned for follow-up.

Low socioeconomic status was defined as primary or lower education, and individual monthly income < SGD2000.

Bolded values indicate statistically significant results.

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of participants by follow-up status.

| Variable | Mean (SD) or Number (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lost to follow-up (n = 854) | Returned for follow-up (n = 1749) | P value* | |

| Age, years | 58.3 (10.8) | 55.6 (8.8) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay in Singapore, years | 49.1 (15.1) | 48.2 (13.8) | 0.099 |

| Gender, Male | 412 (48.2) | 833 (47.6) | 0.768 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 165 (19.3) | 293 (16.8) | 0.106 |

| Low socioeconomic status | 469 (54.9) | 807 (46.1) | <0.001 |

| Current smoker | 155 (18.1) | 219 (12.5) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol drinker | 112 (13.1) | 216 (12.3) | 0.581 |

| Diabetes | 342 (40.0) | 595 (34.0) | 0.003 |

| Hypertension | 529 (61.9) | 910 (52.0) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 370 (43.3) | 740 (42.3) | 0.623 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 85 (10.0) | 83 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Anti-diabetic medication use | 212 (24.8) | 396 (22.6) | 0.217 |

| Anti-hypertensive medication use | 291 (34.1) | 526 (30.1) | 0.039 |

| Anti-cholesterol medication use | 212 (24.8) | 433 (24.8) | 0.970 |

*Mann-Whitney U test or chi-squared test.

Low socioeconomic status was defined as primary or lower education, and individual monthly income < SGD2000.

Bolded values indicate statistically significant results.

Table 3.

Association between generation and incidence of CVD and its sub-types.

| Number† | Incident cases‡ (%) | Age-gender adjusted | Multivariable-adjusted* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk (95% CI) | P value | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value | |||

| CVD | ||||||

| 1st Generation | 406 | 10 (2.5) | Reference = 1 | Reference = 1 | ||

| 2nd Generation | 1343 | 63 (4.7) | 2.34 (1.20 to 4.53) | 0.012 | 2.04 (1.04 to 3.99) | 0.038 |

| Myocardial infarction | ||||||

| 1st Generation | 455 | 5 (1.1) | Reference = 1 | Reference = 1 | ||

| 2nd Generation | 1486 | 18 (1.2) | 2.89 (1.11 to 7.52) | 0.029 | 2.26 (0.87 to 5.89) | 0.095 |

| Stroke | ||||||

| 1st Generation | 420 | 5 (1.2) | Reference = 1 | Reference = 1 | ||

| 2nd Generation | 1407 | 40 (2.8) | 2.02 (0.76 to 5.40) | 0.161 | 2.01 (0.76 to 5.36) | 0.161 |

| Angina | ||||||

| 1st Generation | 443 | 4 (0.9) | Reference = 1 | Reference = 1 | ||

| 2nd Generation | 1442 | 21 (1.5) | 1.73 (0.58 to 4.53) | 0.325 | 1.73 (0.56 to 5.38) | 0.345 |

*Adjusted for age, gender, obesity, low SES (primary or lower education, and individual monthly income < SGD2000), smoking, alcohol, presence of comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and CKD, use of anti-diabetic, anti-hypertensive and anti-cholesterol medications.

Bolded values indicate statistically significant results.

†The number of individuals at risk of CVD is not the sum of the number of individuals without each of the constituent conditions (myocardial infarction, stroke and angina) at baseline. For example an individual without myocardial infarction at baseline (at risk of developing incident myocardial infarction) might already have angina and/or stroke and wouldn’t be included in the denominator for CVD.

‡Number of incident CVD cases is also not the sum of the incidence cases of each constituent condition as individuals could develop more than one condition.

CVD = cardio vascular disease; CKD = chronic kidney disease; SES = socioeconomic status.

Table 4.

Association between generation and incidence of CVD related conditions.

| Number# | Incident Cases (%) | Age-gender adjusted | Multivariable-adjusted* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk (95% CI) | P value | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Diabetes | ||||||

| 1st Generation | 290 | 35 (12.1) | Reference = 1 | Reference = 1 | ||

| 2nd Generation | 966 | 137 (14.2) | 1.18 (0.83 to 1.68) | 0.345 | 1.16 (0.81 to 1.66) | 0.407 |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| 1st Generation | 186 | 62 (33.3) | Reference = 1 | Reference = 1 | ||

| 2nd Generation | 681 | 256 (37.6) | 1.13 (0.90 to 1.41) | 0.293 | 1.07 (0.85 to 1.34) | 0.573 |

| Hyperlipidemia | ||||||

| 1st Generation | 242 | 87 (36.0) | Reference = 1 | Reference = 1 | ||

| 2nd Generation | 765 | 351 (45.9) | 1.33 (1.11 to 1.60) | 0.002 | 1.27 (1.06 to 1.53) | 0.011 |

| CKD | ||||||

| 1st Generation | 403 | 22 (5.5) | Reference = 1 | Reference = 1 | ||

| 2nd Generation | 1378 | 83 (6.0) | 1.93 (1.22 to 3.03) | 0.005 | 1.92 (1.22 to 3.04) | 0.005 |

| Obesity | ||||||

| 1st Generation | 403 | 18 (4.5) | Reference = 1 | Reference = 1 | ||

| 2nd Generation | 1240 | 76 (6.1) | 1.19 (0.72 to 1.97) | 0.487 | 1.26 (0.76 to 2.11) | 0.374 |

*Adjusted for age, gender, obesity, low SES (primary or lower education, and individual monthly income < SGD2000), smoking, alcohol, use of anti-diabetic, anti-hypertensive and anti-cholesterol medications, CVD and mutually for the other CVD related conditions at baseline.

#Number at risk varied depending on outcome (e.g. only 867 participants did not have hypertension at baseline and were at risk of incident hypertension).

Bolded values indicate statistically significant results.

CVD = cardio vascular disease; CKD = chronic kidney disease; SES = socioeconomic status.

Results

Of the 3400 individuals who participated in SINDI-1, 3022 (88.8%) had complete data for baseline characteristics including information on immigrant status as per our definitions. Of these, 1981 (65.5%) returned for follow-up examination. Of these, 232 (11.7%) had CVD at baseline, leaving 1749 (88.3%) individuals (with no CVD at baseline, information on immigrant status and other relevant covariates at baseline and CVD data at follow-up) for the final analysis of incident CVD outcome. Of these, 406 (23.2%) and 1343 (76.8%) were first- and second-generation Indians, respectively. For the analysis of the association between immigrant status and incident CVD risk factors, study populations for incident diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity and CKD were 1256, 867, 1007, 1643 and 1781, respectively.

Table 1 shows the differences in baseline characteristics of participants by immigration status (first versus second-generation). Compared to first (n = 406, 23.2%), second-generation individuals (n = 1343, 76.8%) were younger, more likely to be female and to be obese, have low SES (primary or lower education, and individual monthly income <SGD2000), were smokers and have a longer duration of stay in Singapore.

Table 2 shows the differences in baseline characteristics of participants who returned for follow-up versus those who did not. Compared to those who returned for follow-up (n = 1749, 67.2%), those lost to follow-up (n = 854, 32.8%) were older, more likely to be smokers, have low SES, have other comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, CKD and were more likely to be on antihypertensive medications.

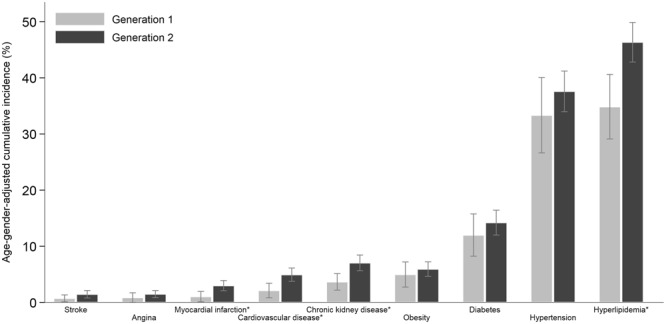

Of the 1749 participants included in our final analyses for incident CVD (mean age (SD) 55.5 (8.8) years); 833 (47.5%) male), 73 (4.1%) developed CVD during the 6-year follow-up period. Figure 1 shows the 6-year cumulative incidence (age and gender adjusted) of CVD and its risk factors in first- and second-generation Indians in Singapore. Compared with first-generation, second-generation Indians had significantly higher incidence of myocardial infarction, CVD, CKD and hyperlipidemia.

Figure 1.

6-year cumulative incidence (age and gender adjusted) of CVD and related conditions in first- and second-generation Indians in Singapore. Asterisk indicates statistical significance between generations (p < 0.05). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

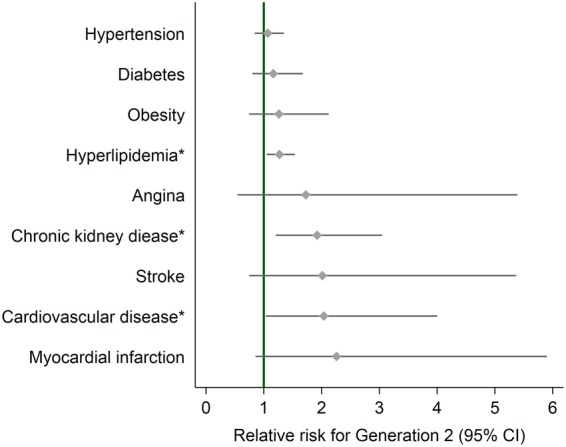

Table 3 shows the multivariable adjusted models for the impact of generation on the incidence of CVD and its sub-types. In model 1 (adjusted for age and gender), compared to first-generation immigrants, second-generation individuals had more than a two-fold increased risk of developing CVD (RR = 2.34; 95% CI 1.20, 4.53; p = 0.012). These findings persisted in a fully adjusted model accounting for age, gender, obesity, low SES, smoking status, alcohol use, presence of comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia, and use of anti-diabetic, anti-hypertensive and anti-cholesterol medications (RR = 2.04; 95% CI 1.04, 3.99; p = 0.038; model 2 in Table 3 and Fig. 2). Upon further sub-analysis of CVD subtypes (myocardial infarction, stroke or angina), no significant association between generation and CVD subtypes was seen (all p > 0.05; model 2 in Table 3, Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Relative risk of incident CVD and related conditions in second versus first-generation Indian individuals in Singapore. Asterisk indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Relative risk estimates have adjusted for age, gender, obesity, socioeconomic status, smoking, alcohol use, anti-diabetic, anti-hypertensive, and anti-cholesterol medications use, and mutually for the other CVD related conditions at baseline.

Table 4 shows the multivariable models for the impact of generation on the incidence of CVD risk factors including, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and CKD. In model 1 (adjusted for age and gender), compared to first-generation immigrants, second-generation individuals had 1.33 and 1.93 times increased risk of developing hyperlipidemia (RR = 1.33; 95% CI 1.11, 1.60; p = 0.002) and CKD (RR = 1.93; 95% CI 1.22, 3.03; p = 0.005), respectively. These findings persisted in a fully adjusted model accounting for age, gender, SES, smoking, alcohol, medication use, CVD, and mutually for other CVD related conditions at baseline including diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity and CKD, for both hyperlipidemia (RR = 1.27; 95% CI 1.06, 1.53; p = 0.011) and CKD (RR = 1.92; 95% CI 1.22, 3.04; p = 0.005; model 2 in Table 4 and Fig. 2).

Supplementary Table S1 shows the multivariable models for the association of length of stay in Singapore with the incidence of CVD and its risk factors including, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and CKD. In a fully adjusted model accounting for age, gender, obesity, low SES, smoking, alcohol, use of anti-diabetic, anti-hypertensive, and anti-cholesterol medications, and mutually for the other CVD related conditions at baseline, a longer length of stay in Singapore was independently associated with higher incidence of hyperlipidemia (RR = 1.12; 95% CI 1.05, 1.20; p = 0.001) and CKD (RR = 1.26; 95% CI 1.07, 1.48; p = 0.005).

Discussion

In this prospective, population-based study of ethnic Indian adults living in Singapore, a significant generational difference in incidence of CVD and its risk factors was found. We demonstrated that second-generation Indian individuals had increased risk of incident CVD, hyperlipidemia and CKD compared to first-generation immigrants, independent of conventional cardiovascular risk factors. Our findings highlight the need of targeted CVD and its risk factors preventative strategies in high-risk second-generation Indian individuals, potentially translatable not only to Singaporean Indians but also to other migrant Indians living outside India.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to examine the impact of generation on incidence of CVD and its major risk factors in Asians, making it challenging to compare our findings. Nevertheless, our results are consistent with longitudinal studies reporting lower incidence of CVD among foreign-born than US-born individuals36,37. Our findings confirm the growing body of evidence from previous cross-sectional studies that demonstrated higher prevalence of CVD, its conventional risk factors, and potentially modifiable CVD risk factors such as diet, physical inactivity and psychological stress in more acculturated second-generation (born in host country) individuals than less acculturated first-generation (born in home country) immigrants20,28,38–40.

Consistent with previous work, our findings also suggest that longer length of stay in host country may be associated with higher rates of CVD (but not CVD subtypes likely due to inadequate statistical power) and its risk factors. Studies have demonstrated that individuals residing for a long time in host country have higher physiological and psychological stress compared to those with fewer years of residence41. This finding implies that more acculturated individuals have higher susceptibility to health risks compared with their less acculturated counterparts39,40. For example, recent Chinese immigrants report a healthier diet and more physical activity than those who have resided in the United States >10 years42. Likewise, recent Japanese immigrants to the United States often adhere to a traditional Japanese lifestyle, including, but not limited to, healthful dietary practices and physical activity, and often have lower CVD rates and risk factors compared to those of Japanese ethnicity who were born outside of Japan43.

Our finding that second-generation Indians have an increased risk of incident CVD and its risk traits, particularly hyperlipidemia, independent of conventional CVD risk factors, suggest that being born in a developed country like Singapore with a “high-risk” lifestyle such as sedentary employment, consumption of more energy-dense processed foods, lack of physical activity, and psychological stress, may be the contributing factors44,45. These exposures may make them more susceptible to an increased risk of developing CVD and its risk attributes. However, as we did not collect these and other variables such as psychological stress, depression, dietary practices and physical activity in SINDI, further longitudinal studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis. Nonetheless, our results indicate that public health actions to address these detrimental modifications in lifestyle in second-generation individuals and prevent an inordinate increase in CVD outcomes.

One important factor that may be contributing to our finding that second-generation Indian individuals had higher risk of incident CVD and its risk traits (hyperlipidemia and CKD) is that our second-generation individuals had lower SES. Numerous studies have shown poor SES predisposes individuals to a higher risk of depression46, high psychiatric morbidity47, more disability48 and poorer healthcare access49. Many risk factors for CVD are also associated with low SES50. Therefore, it is possible that socio-economic disadvantage played a role in the development of CVD and its risk factors in second-generation individuals in our cohort. However, as our fully adjusted model showed that generational impact on incidence of CVD and its risk factors was independent of SES, further work is needed to confirm this finding.

Strengths of our study include a population-based and prospective study design, the use of standardized interview-based assessment and clinical testing protocols, and inclusion of a wide range of CVD risk factors. However, our results must be interpreted within the context of certain limitations. The assessment of CVD was self-reported and, as a result, our outcome may be subjected to recall and other biases. However, we believe that that the impact of such biases would likely be similar in first and second-generation Indians. In addition, previous studies have shown self-reported outcomes for CVD to be valid in the estimation of actual outcome51–53. Combined with our reliability results of ~75%, we consider that the self-reported CVD outcomes captured in our study remains an appropriate indicator of actual CVD events. Another limitation is that our hypothesis assumes that first-generation Indian immigrants had different lifestyles or environments in their home country before moving to Singapore. This assumption may not hold true and, as such, caution should be taken when interpreting our results. Last, information on risk factors, such as psychological stress, dietary practices, physical inactivity, are not available in this study, and therefore the possibility of residual confounding in our regression analysis could not be excluded. Further studies to elucidate the role of these factors are warranted.

In summary, we showed that second-generation Indians have increased risk of incident CVD, hyperlipidemia and CKD, compared to first-generation immigrants, after controlling for a range of conventional CVD risk factors. This information can inform key policy- and decision-makers in design and implementation of targeted CVD and its risk factors preventative strategies in susceptible second-generation Indian individuals.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council (NMRC) under its Talent Development Scheme NMRC/STaR/0003/2008 and Biomedical Research Council (BMRC), Singapore 08/1/35/19/550. The grant body had no roles in design, conduct or data analysis of the study, nor in manuscript preparation and approval.

Author Contributions

P.G. Conception and design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of article A.G. Analysis and interpretation of data; revision of article R.M. Conception and design; revision of article E.F. Conception and design; revision of article Y.C.T. Revision of article C.S. Analysis and interpretation of data; revision of article T.Y.W. Interpretation of data; revision of article C.Y.C. Interpretation of data; revision of article E.L. Conception and design; interpretation of data; revision of article; final approval of version to be published.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-32833-0.

References

- 1.Roth GA, et al. Global and regional patterns in cardiovascular mortality from 1990 to 2013. Circulation. 2015;132:1667–1678. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akil L, Ahmad HA. Relationships between obesity and cardiovascular diseases in four southern states and Colorado. J health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;22:61–72. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kachur S, Lavie CJ, de Schutter A, Milani RV, Ventura HO. Obesity and cardiovascular diseases. Minerva Med. 2017;108:212–228. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4806.17.05022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad DS, Das BC. Physical inactivity: a cardiovascular risk factor. Indian J Med Sci. 2009;63:33–42. doi: 10.4103/0019-5359.49082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riha J, et al. Urbanicity and lifestyle risk factors for cardiometabolic diseases in rural Uganda: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez AV, Pasupuleti V, Deshpande A, Bernabe-Ortiz A, Miranda JJ. Effect of rural-to-urban within-country migration on cardiovascular risk factors in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2012;98:185–194. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steyn, K. & Damasceno, A. Lifestyle and Related Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases. In: Jamison, D. T. et al., editors. Disease and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington (DC): World Bank The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank.; 2006. [PubMed]

- 8.Marmot MG, Syme SL. Acculturation and coronary heart disease in Japanese-Americans. Am J Epidemiol. 1976;104:225–247. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindstrom M, Sundquist J. Immigration and leisure-time physical inactivity: a population-based study. Ethn Health. 2001;6:77–85. doi: 10.1080/13557850120068405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delavari M, Sonderlund AL, Swinburn B, Mellor D, Renzaho A. Acculturation and obesity among migrant populations in high income countries–a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:458. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmboe-Ottesen Gerd, Wandel Margareta. Changes in dietary habits after migration and consequences for health: a focus on South Asians in Europe. Food & Nutrition Research. 2012;56(1):18891. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v56i0.18891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lesser IA, Gasevic D, Lear SA. The association between acculturation and dietary patterns of South Asian immigrants. PloS One. 2014;9:e88495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gadd M, Sundquist J, Johansson SE, Wandell P. Do immigrants have an increased prevalence of unhealthy behaviours and risk factors for coronary heart disease? Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005;12:535–541. doi: 10.1097/00149831-200512000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng Y, et al. Impact of migration and acculturation on prevalence of type 2 diabetes and related eye complications in Indians living in a newly urbanised society. PloS One. 2012;7:e34829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetic retinopathy in migrant Indians in an urbanized society in Asia: the Singapore Indian eye study. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2119–2124. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ueshima H, et al. Differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors between Japanese in Japan and Japanese-Americans in Hawaii: the INTERLIPID study. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:631–639. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundquist J, Winkleby M. Country of birth, acculturation status and abdominal obesity in a national sample of Mexican-American women and men. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:470–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sundquist J, Winkleby MA. Cardiovascular risk factors in Mexican American adults: a transcultural analysis of NHANES III, 1988-1994. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:723–730. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.5.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lutsey PL, et al. Associations of acculturation and socioeconomic status with subclinical cardiovascular disease in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1963–1970. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morales LS, Leng M, Escarce JJ. Risk of cardiovascular disease in first and second generation Mexican-Americans. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13:61–68. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9262-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh GK, Siahpush M. All-cause and cause-specific mortality of immigrants and native born in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:392–399. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.3.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez L, et al. Impact of acculturation on cardiovascular risk factors among elderly Mexican Americans. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24:714–719. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin K, Gullick J, Neubeck L, Koo F, Ding D. Acculturation is associated with higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk-factors among Chinese immigrants in Australia: Evidence from a large population-based cohort. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24:2000–2008. doi: 10.1177/2047487317736828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiu M, Maclagan LC, Tu JV, Shah BR. Temporal trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors among white, South Asian, Chinese and black groups in Ontario, Canada, 2001 to 2012: a population-based study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007232. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurian AK, Cardarelli KM. Racial and ethnic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review. Ethn Dis. 2007;17:143–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inkpen, C. 7 facts about world migration. Pew Research Center. Available at: http://www.pewresearch.or/fact-tank/2014/09/02/7-facts-about-world-migration/ (2014).

- 27.The Singapore Department of Statistics. Singapore Population and Population Structure. Available at: http://www.singstat.gov.sg/statistics/browse-by-theme/population-and-population-structure.

- 28.Singapore Department of Statistics. Singapore in figures 2010. Ethnic distribution, 2009. Available at: http://www.simgstat.gov.sg/pubn/popn/c2010acr/key_demographic_trends.pdf.

- 29.Lavanya R, et al. Methodology of the Singapore Indian Chinese Cohort (SICC) eye study: quantifying ethnic variations in the epidemiology of eye diseases in Asians. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2009;16:325–336. doi: 10.3109/09286580903144738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabanayagam C, et al. Singapore Indian Eye Study-2: methodology and impact of migration on systemic and eye outcomes. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;45:779–789. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong MYZ, et al. Is Corneal Arcus Independently Associated With Incident Cardiovascular Disease in Asians? Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;183:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Standards of medical care in diabetes–2015: summary of revisions. Diabetes care38 Suppl, S4 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.National High Blood Pressure Education P. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Bethesda (MD): National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (US); 2004. [PubMed]

- 34.Levey AS, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lim CC, et al. Chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease and mortality: A prospective cohort study in a multi-ethnic Asian population. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:1018–1026. doi: 10.1177/2047487314536873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le-Scherban F, et al. Immigrant status and cardiovascular risk over time: results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:429–35.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moon JR, et al. Stroke incidence in older US Hispanics: is foreign birth protective? Stroke. 2012;43:1224–1229. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.643700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1543–1548. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.10.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dixon LB, Sundquist J, Winkleby M. Differences in energy, nutrient, and food intakes in a US sample of Mexican-American women and men: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:548–557. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.6.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diez Roux AV, et al. Acculturation and socioeconomic position as predictors of coronary calcification in a multiethnic sample. Circulation. 2005;112:1557–1565. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.530147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fang CY, Ross EA, Pathak HB, Godwin AK, Tseng M. Acculturative stress and inflammation among Chinese immigrant women. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:320–326. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor VM, et al. Heart disease prevention among Chinese immigrants. J Community Health. 2007;32:299–310. doi: 10.1007/s10900-007-9057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robertson TL, et al. Epidemiologic studies of coronary heart disease and stroke in Japanese men living in Japan, Hawaii and California. Coronary heart disease risk factors in Japan and Hawaii. Am J Cardiol. 1977;39:244–249. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(77)80198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arandia G, Nalty C, Sharkey JR, Dean WR. Diet and acculturation among Hispanic/Latino older adults in the United States: a review of literature and recommendations. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;31:16–37. doi: 10.1080/21551197.2012.647553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murillo R, Albrecht SS, Daviglus ML, Kershaw KN. The Role of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviors in Explaining the Association Between Acculturation and Obesity Among Mexican-American Adults. Am J Health Promot. 2015;30:50–57. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.140128-QUAN-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Freeman A, et al. The role of socio-economic status in depression: results from the COURAGE (aging survey in Europe) BMC public health. 2016;16:1098. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3638-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lazzarino AI, Hamer M, Stamatakis E, Steptoe A. Low socioeconomic status and psychological distress as synergistic predictors of mortality from stroke and coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:311–316. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182898e6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wamala SP. Large social inequalities behind women’s risk of coronary disease. Unskilled work and family strains are crucial factors. Lakartidningen. 2001;98:177–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kristiansson C, et al. Access to health care in relation to socioeconomic status in the Amazonian area of Peru. Int J Equity Health. 2009;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winkleby MA, Jatulis DE, Frank E, Fortmann SP. Socioeconomic status and health: how education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:816–820. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.82.6.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eliassen BM, et al. Validity of self-reported myocardial infarction and stroke in regions with Sami and Norwegian populations: the SAMINOR 1 Survey and the CVDNOR project. BMJ open. 2016;6:e012717. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wada K, et al. Self-reported medical history was generally accurate among Japanese workplace population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamagishi K, Ikeda A, Iso H, Inoue M, Tsugane S. Self-reported stroke and myocardial infarction had adequate sensitivity in a population-based prospective study JPHC (Japan Public Health Center)-based Prospective Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.