Abstract

Objective To investigate the impact of industry funding on reporting of subgroup analyses in randomised controlled trials.

Design Systematic review.

Data sources Medline.

Study selection Randomised controlled trials published in 118 core clinical journals (defined by the National Library of Medicine) in 2007. 1140 study reports in a 1:1 ratio by high (five general medicine journals with largest number of total citations in 2007) versus lower impact journals, were randomly sampled. Two reviewers, independently and in duplicate, used standardised, piloted forms to screen study reports for eligibility and to extract data. They also used explicit criteria to determine whether a randomised controlled trial reported subgroup analyses. Logistic regression was used to examine the association of prespecified study characteristics with reporting versus not reporting of subgroup analyses.

Results 469 randomised controlled trials were included, of which 207 (44%) reported subgroup analyses. High impact journals (adjusted odds ratio 2.64, 95% confidence interval 1.62 to 4.33), non-surgical (versus surgical) trials (2.10, 1.26 to 3.50), and larger sample size (3.38, 1.64 to 6.99) were associated with more frequent reporting of subgroup analyses. The strength of association between trial funding and reporting of subgroups differed in trials with and without statistically significant primary outcomes (interaction P=0.02). In trials without statistically significant results for the primary outcome, industry funded trials were more likely to report subgroup analyses (2.29, 1.30 to 4.72) than non-industry funded trials. This was not true for trials with a statistically significant primary outcome (0.79, 0.46 to 1.36). Industry funded trials were associated with less frequent prespecification of subgroup hypotheses (31.3% v 38.0%, adjusted odds ratio 0.49, 0.26 to 0.94), and less use of the interaction test for analyses of subgroup effects (41.4% v 49.1%, 0.52, 0.28 to 0.97) than non-industry funded trials.

Conclusion Industry funded randomised controlled trials, in the absence of statistically significant primary outcomes, are more likely to report subgroup analyses than non-industry funded trials. Industry funded trials less frequently prespecify subgroup hypotheses and less frequently test for interaction than non-industry funded trials. Subgroup analyses from industry funded trials with negative results for the primary outcome should be viewed with caution.

Introduction

Subgroup analyses are common in randomised controlled trials.1 2 3 4 5 6 Previous studies have found that 60% of trials published in high impact general medical journals,1 6 61% of cardiovascular trials,3 and 37% of surgical trials2 report subgroup analyses. Investigators carry out subgroup analyses to examine if observed treatment effects differ across baseline characteristics. Once reported, these analyses can have substantial influence on clinical and public health decision making. This influence may be misleading as subsequent studies have proved that many subgroup findings are spurious.7 For instance, a randomised trial showed that aspirin was ineffective in the secondary prevention of stroke in women8; a subsequent large collaborative meta-analysis, however, showed that aspirin was beneficial in both men and women.9 In another example, a subgroup analysis in a randomised trial found ticlopidine to be superior to aspirin for preventing recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, or vascular death in black patients but not in white patients,10 whereas a subsequently larger trial showed no statistically significant difference between the drugs in preventing stroke, myocardial infarction, and vascular death in black patients.11

An understanding of factors underlying reporting of subgroup analyses may aid the interpretation and appropriate use of subgroup findings in trials. However, the investigation of factors associated with reporting of subgroup analyses has thus far been limited. Two studies have shown an association between larger sample size with reporting of subgroup analysis,3 6 one of which found that the rate of subgroup reporting varied among high impact medical journals.6 These two studies were, however, restricted to trials published in high impact general medical journals or selected cardiovascular journals, and one was restricted to trials reporting interaction tests for subgroup analyses.6 These restrictions limit the generalisability of their results.

Existing studies have left several potentially important factors unexplored. A number of studies have reported evidence on the influence of sponsors on aspects of trial design, conduct, and reporting other than the use of subgroup analysis.12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Funding by industry may also influence the reporting of subgroup analyses. One hypothesis would suggest that, in the absence of a statistically significant primary outcome, industry funded trials may, looking for a positive effect, seek statistically significant findings in patient subgroups. Were this the case, the influence of industry would have an effect on subgroup reporting in trials with negative findings but not positive findings. Other factors that may influence subgroup reporting include clinical area (for example, surgical v medical) and journal types (high impact journals v others).1 2 3 5

We systematically reviewed randomised controlled trials to investigate the association of prespecified study characteristics with reporting of subgroup analyses. In particular we examined the impact of industry funding on the reporting of subgroups.

Methods

The protocol for our study, detailing the design and analysis, is published elsewhere.21 We included any randomised controlled trial carried out on humans unless it focused on a subset of the original population enrolled, was explicitly labelled as a phase I trial, was exclusively a pharmacokinetic study, or was reported as a research letter. We applied no restrictions to study design (parallel, factorial, crossover), number of trial arms, unit of randomisation, type of study (superiority, non-inferiority, equivalence), or study sample size.

Literature search

We applied a predefined search strategy (see web extra appendix 1),21 developed with the help of an experienced librarian, to the core clinical journals in 2007 in Medline through Ovid. The search strategy applied both MeSH terms and free texts and was highly sensitive to identify randomised controlled trials. The core clinical journals defined by the National Library of Medicine, known as the Abridged Index Medicus, included 118 journals in 2007, covering all specialties of clinical medicine and public health sciences (see web extra appendix 2).22 We stratified these journals into high and lower impact groups according to the total citations in 2007 defined by the Web of Science.23 The five high impact journals, with the highest number of total citations, were the Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, JAMA, Lancet, and New England Journal of Medicine. After removing duplicate articles, our search resulted in 3662 journal reports.

Sample size and random sampling

Prior to our definitive study, we carried out a pilot study of 139 randomised trials and found that 62 (45%) reported subgroup analyses and 27 (19%) claimed subgroup effects.

Our sample size estimation for the definitive study was based on the examination of study characteristics associated with the claim of subgroup effects for any outcome. In our regression analysis of study characteristics with the claim of subgroup effects, we planned to include six study characteristics, a total of nine categories of variables. Setting a criterion of 10 events (that is, the claim of subgroup effect) for each category resulted in a total of 90 events (and at least 90 total non-events). Given the results of our pilot study, we determined we would require a total of 464 trials. 21

We used the random sampling procedure available in the Stata statistical program to randomly select, in a 1:1 ratio, study reports from each journal group—that is, high versus lower impact journals. We repeated the random sampling until the planned sample size was reached. At each sampling process we excluded previously sampled reports from the database. We ultimately chose 570 reports in each of the high and lower impact journals, resulting in 1140 reports.

Study screening and data extraction

Eight pairs of reviewers trained in methodology used standardised, previously piloted forms with detailed written instructions on screening the title, abstract, and full text and extracting data, independently and in duplicate.21 To ensure consistency across reviewers we carried out calibration exercises before starting the review.

While screening the title and abstract, reviewers determined if the studies were randomised controlled trials enrolling humans. The reviewers independently screened the full text of potentially eligible trials to determine eligibility. At the stage of full text screening, the reviewers selected a primary outcome for eligible studies using prespecified criteria (see web extra appendix 3) and identified a pairwise comparison if the studies included three or more study arms (see web extra appendix 4).

We defined a subgroup as a subset of a trial population that was identified on the basis of a characteristic of a patient or intervention that was measured either at baseline or after randomisation. We defined a subgroup analysis as a statistical analysis that explored whether effects of the intervention (experimental v control) differed according to status of a subgroup variable.

We judged a subgroup analysis to be present if the study reported one of the following: a point estimate and an associated confidence interval or a P value for one or more subgroups, the magnitude of difference in the effect between patient subgroups, the results from an interaction test, or an explicit statement that a subgroup analysis had been done.

The reviewers extracted data on study characteristics, including funding sources; clinical area; and type of intervention, and determined whether results for the primary outcome were statistically significant using a threshold of P<0.05. Reviewers recorded whether trials reported subgroup analyses for any outcomes (primary or secondary), number of outcomes for which subgroup analyses were reported, type of outcomes reported, number of subgroup analyses reported, whether any subgroup analysis was specified a priori, and whether any subgroup effect was stated to have been analysed by a test of interaction. We used detailed written instructions for extracting this information.

We defined a priori subgroup analyses as those that prespecified subgroup hypotheses—that is, prespecified subgroup variables for examination of a subgroup effect. We defined the source of funding based on statements reported in the methods, disclosure of conflicts of interest, acknowledgements, and funding sections of the study report. We categorised the source of funding as governmental agencies, private not for profit organisations, industry funding, explicit statement of no funding, or funding source not reported. When the reviewers were unclear as to the category of declared funding source, we searched the websites of funding agencies for clarification.

Teams of reviewers resolved discrepancies by consensus or, if a discrepancy remained, through discussion with one of two arbitrators (XS or GHG). The inter-rater agreement was high for initial opinions on study eligibility (observed agreement=95%, κ=0.80) and reporting of a subgroup analysis (observed agreement=91%, κ=0.82).

Data analysis

We calculated the proportion of trials reporting subgroup analyses. To examine the association of reporting versus not reporting of subgroup analyses with study characteristics, we carried out univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses, with reporting of a subgroup analysis as the dependent variable.

We prespecified six study characteristics: journal type (high v lower impact), study area (non-surgical v surgical), mean sample size per arm, number of prespecified primary outcomes, source of funding (industry v other), and statistical significance of the primary outcome. We also prespecified the interaction between the statistical significance of the primary outcome and funding source. These seven factors were included in the regression model as independent variables. We also prespecified direction of these hypotheses: trials are more likely to report subgroup analyses if they have a larger sample size, are published in high impact journals, investigate non-surgical interventions, and report more prespecified primary outcomes. Trials funded by industry are more likely to report subgroup results when the primary outcome is not statistically significant than if the primary outcome is statistically significant.

To test the interaction between statistical significance of the primary outcome (significant v not significant) and type of funding (industry v non-industry), we included the six independent variables and the interaction term in our regression model. Conditional on the finding of the statistically significant interaction (P<0.05), we further calculated the association of funding source with subgroup reporting in two subgroups (presence v absence of statistically significant main effect).

We compared the reporting of subgroup analyses in industry funded versus non-industry funded trials, including the number of subgroup analyses reported and the number of variables for patients or interventions, as well as number of outcomes used for subgroup analyses. We also examined whether authors specified a subgroup hypothesis a priori, and reported a test of interaction for subgroup analysis in their trial reports. Given that the trial investigators probably report smaller number of subgroup analyses than are actually carried out, we also estimated the number of subgroup analyses that were likely to have been done by trial investigators according to the information provided in the study reports. Typically, if authors stated that they specified a number of variables and used a number of outcomes for the subgroup analyses, we would multiple these together to estimate the number of subgroup analyses. We used the Wilcoxon rank sum test for the analysis of continuous data and the χ2 test for binary data.

To further examine whether industry funded trials versus non-industry funded trials differed in the rate of a priori specification of subgroup hypotheses and use of an interaction test, we also carried out multivariable logistic regression, including the six variables and the interaction term (funding×statistical significance of the primary outcomes) in our model.

In our analysis we defined that a study was funded by industry if it received partial or full funding from industry. We considered a study as non-industry funded if it received other sources of funding, had no funding, or did not report a funding source. To examine the influence of trials that did not report a funding source, we did sensitivity analyses excluding those studies. We used Stata 11.0 for all analyses. All comparisons were two tailed, and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

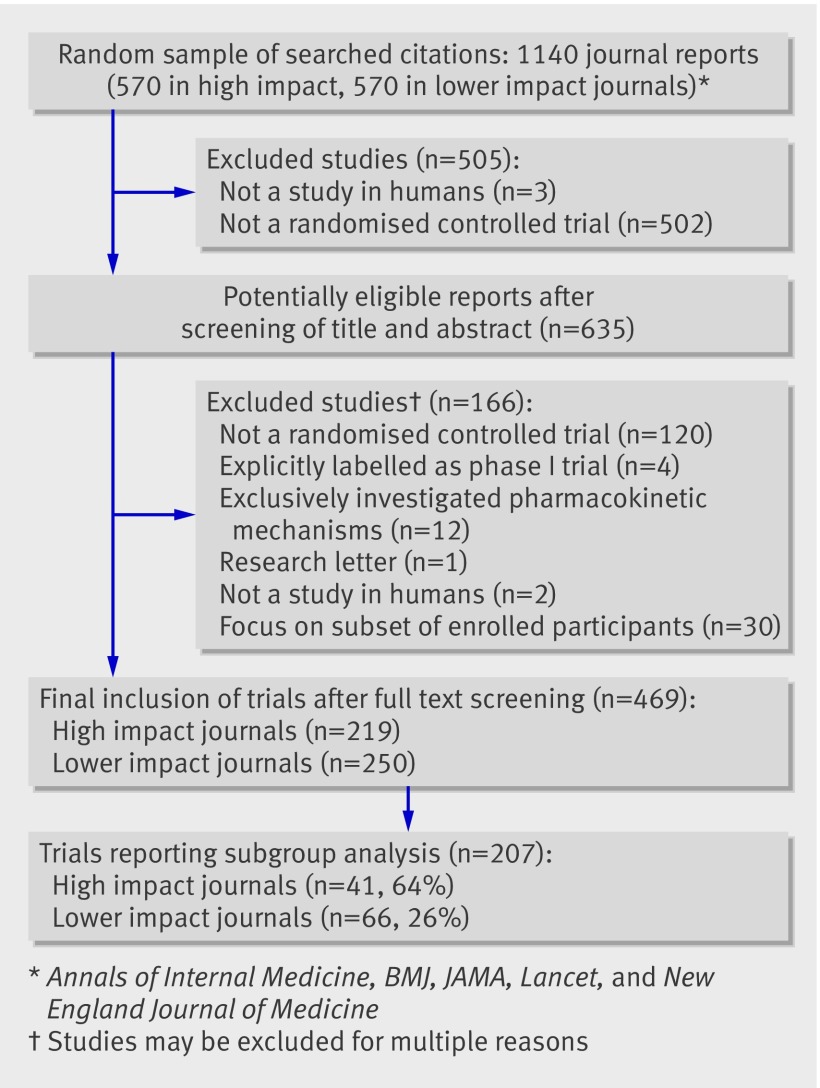

This study included 469 eligible trials reported in 459 articles (figure, also see web extra appendix 5), of which 207 (44%) reported subgroup analyses. Table 1 presents study characteristics of trials that did and did not report subgroup analyses. Of these 469 trials, 186 were funded by industry, 66 did not report a funding source, and the other 217 had other sources of funding or received no funding (see web appendix 6). In the 66 trials that did not report a funding source, 15 (23%) reported subgroup analyses (see web extra appendix 7); these trials generally had small sample sizes (interquartile range 16-51 in mean size per arm).

Flow of study screening

Table 1.

Study characteristics in trials reporting and not reporting subgroup analyses. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Study characteristics | Trials reporting subgroup analyses (n=207) | Trial not reporting subgroup analyses (n=262) |

|---|---|---|

| Median (interquartile range) sample size per study arm* | 214 (81-511) | 54 (24-150) |

| Journal type: | ||

| High impact journals† | 141 (68) | 78 (30) |

| Lower impact journals | 66 (32) | 184 (70) |

| Source of funding: | ||

| Industry | 99 (49) | 87 (33) |

| Other‡ | 108 (52) | 175 (68) |

| Study area: | ||

| Non-surgical | 175 (85) | 169 (65) |

| Surgical | 32 (16) | 93 (36) |

| Main effect for primary outcome: | ||

| Statistically significant | 121 (59) | 173 (66) |

| Statistically non-significant | 86 (42) | 89 (34) |

| Study design: | ||

| Parallel | 190 (91) | 238 (91) |

| Factorial | 9 (3) | 4 (2) |

| Crossover | 8 (6) | 20 (8) |

| Unit of randomisation: | ||

| Individual participant | 198 (96) | 246 (94) |

| Cluster of participants | 9 (4) | 16 (6) |

| Type of selected primary outcome: | ||

| Time to event | 55 (27) | 18 (7) |

| Binary | 78 (38) | 77 (29) |

| Continuous | 66 (33) | 163 (62) |

| Others | 8 (3) | 4 (2) |

*Sample size considered for selected comparison.

†Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, JAMA, Lancet, and New England Journal of Medicine.

‡Governmental agencies, private not for profit organisations, explicit statement of no funding, or funding source not reported.

Univariable analyses showed that high impact journals, non-surgical trials, larger sample size, and industry funding were statistically associated with more frequent reporting of subgroup analyses (table 2). Multivariable analyses showed more frequent reporting of subgroup analyses with high impact journals, non-surgical trials, and larger sample size (table 2). A differential strength of association of industry funding with subgroup reporting was present in trials with and without significant primary outcomes (interaction P=0.021): when the primary outcome was not significant, the likelihood of reporting subgroup analyses in industry funded trials was higher than in non-industry funded trials (67% v 40%, adjusted odds ratio 2.29, 95% confidence interval 1.30 to 4.72, P=0.005). By contrast, industry funding was not statistically associated with reporting subgroup analysis when the primary outcome was significant (37% v 48% in other trials, 0.79, 0.46 to 1.36).

Table 2.

Regression analyses of factors associated with reporting versus not reporting of subgroup analyses

| Study characteristics | Univariable analyses | Multivariable analyses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | ||

| High impact v lower impact journals* | 5.04 (3.39 to 7.48) | <0.001 | 2.64 (1.62 to 4.33) | <0.001 | |

| Non-surgical v surgical trial | 3.01 (1.91 to 4.74) | <0.001 | 2.10 (1.26 to 3.50) | 0.005 | |

| Sample size per arm (fourths): | |||||

| 3-32 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||

| 33-101 | 2.38 (1.30 to 4.36) | 0.005 | 1.83 (0.97 to 3.46) | 0.062 | |

| 102-301 | 5.85 (3.21 to 10.65) | <0.001 | 3.41 (1.74 to 6.67) | <0.001 | |

| ≥302 | 8.64 (4.70 to 15.86) | <0.001 | 3.38 (1.64 to 6.99) | 0.001 | |

| No of prespecified primary outcomes | 1.18 (0.97 to 1.43) | 0.098 | 1.08 (0.87 to 1.35) | 0.48 | |

| Statistical significance of result for primary outcome: non-significant v significant | 1.38 (0.94 to 2.01)† | 0.092 | 0.97 (0.56 to 1.67)‡ | 0.91 | |

| Industry funding v other | 1.91 (1.31 to 2.77)† | 0.001 | 0.79 (0.46 to 1.36)‡ | 0.40 | |

| Statistical significance×trial funding | 1.89 (0.85 to 4.25)§ | 0.12 | 2.88 (1.17 to 7.08)¶ | 0.021 | |

| Association of trial funding ( industry v other) with reporting subgroup analyses**: | |||||

| With non-significant primary outcome | 3.00 (1.56 to 5.76) | 0.001 | 2.29 (1.30 to 4.72) | 0.005 | |

| With significant primary outcome | 1.58 (0.99 to 2.53) | 0.057 | 0.79 (0.46 to 1.36) | 0.91 | |

*Higher impact journals were Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, JAMA, Lancet, and New England Journal of Medicine.

†Estimates of main effect in univariable analyses. Interaction term was not included.

‡Estimates of main effect including all main effect and interaction terms.

§Estimates were generated from an interaction of funding×significance of primary outcome, and expressed in regression equation as Y=β0+βfunding×Xfunding+βsignifiance×Xsignifiance+βinteraction×Xinteraction. βinteraction represents coefficient of interaction, and its exponential function (eβ) is the odds ratio. The interaction odds ratio is the ratio of odds ratios of the two subgroups (for example, 2.29/0.79=2.88). Estimates of main effect were not shown.

¶Estimate of interaction significance×trial funding in multivariable analyses that included all terms.

**This section presents subgroup estimates conditional on interaction of significance×trial funding—that is, association of reporting with trial funding in trials that had a non-significant primary outcome, and association in trials that had a significant primary outcome.

In the 207 trials reporting subgroup analyses, 99 (49%) were funded by industry. No statistically significant differences were present in characteristics of subgroup reporting between trials funded or not funded by industry in the unadjusted analyses (table 3). The proportion of trials prespecifying subgroup hypotheses (<40%) and reporting an interaction test for analysis of subgroup effect (50%) was low in both industry and non-industry funded trials. The total number of subgroup analyses that were probably carried out seemed to be higher in industry funded trials than in non-industry funded trials (P=0.063). Multivariable analyses found that industry funded trials were associated with less prespecification of subgroup hypotheses (adjusted odds ratio 0.49, 95% confidence interval 0.26 to 0.94, P=0.032, table 4) and less use of the interaction test for analyses of subgroup effects (0.52, 0.28 to 0.97, P=0.039, table 5) than non-industry funded trials.

Table 3.

Reporting and conduct of subgroup analyses in trials* funded or not funded by industry. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Subgroup reporting and conduct | Industry funded trials (n=99) | Non-industry funded trials (n=108) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median No (range) of outcome measures used for subgroup analyses per trial | 2 (1-48) | 2 (1-26) | 0.83† |

| Median No (range) of variables used for subgroup analyses per trial | 4 (1-23) | 2 (1-19) | 0.003† |

| Median total No (range) of subgroup analyses per trial | 7 (1-144) | 6 (1-38) | 0.16† |

| Median total No (range) of subgroup analyses that are most probably done‡ | 9 (1-144) | 6.5 (1-52) | 0.063† |

| Trials specifying at least one subgroup analysis a priori | 31 (31) | 41 (38) | 0.31§ |

| Trials using test of interaction for at least one analysis | 41 (41) | 53 (49) | 0.27§ |

| Trials reporting subgroup analyses for clearly prespecified primary outcome | 72 (73) | 87 (81) | 0.18§ |

*Number of trials reporting subgroup analyses.

†Wilcoxon rank sum test.

‡Given that trial investigators probably report smaller number of subgroup analyses than are done, the number of subgroup analyses that were probably carried out by trial investigators were estimated according to information in study reports. If authors stated that they specified n variables, and used m outcomes for subgroup analyses, it was estimated that they had carried out n×m subgroup analyses.

§χ2 test.

Table 4.

Factors associated with prespecification of subgroup hypotheses in subgroup analyses: multivariable logistic regression

| Study characteristics | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| High impact v lower impact journals | 1.82 (0.78 to 4.21) | 0.16 |

| Non-surgical v surgical trials | 3.50 (1.20 to 10.20) | 0.022 |

| Sample size per arm (fourths): | ||

| 3-32 | 1 (reference) | |

| 33-101 | 3.10 (0.58 to 16.60) | 0.19 |

| 102-301 | 4.73 (0.89 to 25.32) | 0.069 |

| ≥302 | 6.53 (1.19 to 35.58) | 0.03 |

| No of prespecified primary outcomes | 1.04 (0.74 to 1.46) | 0.83 |

| Statistically non-significant v significant primary outcome | 1.48 (0.80 to 2.76) | 0.21 |

| Industry funding v no industry funding | 0.49 (0.26 to 0.94) | 0.032 |

Interaction of significance of primary outcome with funding was not significant (P=0.62), suggesting no differential associations in industry funded versus non-industry funded trials. This higher order term was therefore removed from the regression model.

Table 5.

Factors associated with use compared with no use of interaction test in subgroup analyses: multivariable logistic regression

| Study characteristics | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| High impact v lower impact journals | 2.73 (1.23 to 6.04) | 0.014 |

| Non-surgical v surgical trials | 1.44 (0.61 to 3.42) | 0.41 |

| Sample size per arm (fourths): | ||

| 3-32 | 1 (reference) | |

| 33-101 | 1.51 (0.43 to 5.24) | 0.52 |

| 102-301 | 1.45 (0.41 to 5.15) | 0.56 |

| ≥302 | 2.35 (0.65 to 8.54) | 0.20 |

| No of prespecified primary outcomes | 0.94 (0.68 to 1.28) | 0.67 |

| Statistically non-significant v significant primary outcome | 1.82 (1.001 to 3.30) | 0.049 |

| Industry funding v no industry funding | 0.52 (0.28 to 0.97) | 0.039 |

Interaction of significance of primary outcome with funding was not significant (P=0.41), suggesting no differential associations in industry funded versus non-industry funded trials. This high order term was therefore removed from the regression model.

Sensitivity analyses

Excluding those studies that failed to clearly report funding sources did not change the association of study characteristics with reporting of subgroup analyses (see web extra appendix 8). The magnitude of association of industry funding with subgroup reporting, in the absence of a statistically significant primary outcome, was larger (3.23, 1.57 to 6.66) than in our primary analysis. Industry funding remained statistically associated with less prespecification of subgroup hypotheses (0.52, 0.27 to 0.99, see web extra appendix 9) and non-significantly associated with a lower likelihood of reporting a test of interaction for subgroup analyses (0.58, 0.32 to 1.08, see web extra appendix 10).

Discussion

Randomised controlled trials with larger sample sizes, studying non-surgical topics, and in high impact journals were associated with more frequent reporting of subgroup analyses. The higher rate of reporting in high impact journals may be a result of the independent efforts of the trials’ investigators. Alternatively, editors and reviewers in high impact journals may be more inclined to request such analyses than those in journals with a lower impact. Without direct correspondence with authors, the true explanation remains speculative.

We also found a differential strength of association of trial funding with subgroup reporting in trials with and without statistically significant primary outcomes. If results for the primary outcome were not statistically significant, the odds of reporting subgroup analyses in industry funded trials were 2.3 times that of other trials.

The implication of our results is that particular caution is needed in interpreting subgroup analyses of otherwise negative, and thus possibly unexciting, studies when they are funded by industry. It is perhaps ironic that this finding comes from a subgroup analysis of a study that could be viewed as having otherwise unexciting results. Applying our previously published criteria for the credibility of a subgroup analysis,24 we note that our hypothesis was prespecified and that we correctly prespecified the direction of effect. This subgroup finding was the only subgroup hypothesis tested. The interaction P value (0.023) was statistically significant, and the magnitude of subgroup effect (the difference of the associations in the presence versus absence of a statistically significant primary outcome) was large. Our results are consistent with a large body of literature suggesting that positive “spin” is commonly applied in industry funded studies12 13 15 16 17 19 25 and are supported with a clear rationale (corresponding to biological rationale in randomised trials). The rationale of our a priori hypothesis is as follows. If a study has positive findings, clinicians are likely to consider the intervention for all eligible patients. Under these circumstances, there is no motivation for industry sponsors to carry out subgroup analyses. If, however, the trial has negative findings, clinicians are unlikely to consider the intervention for any patients unless an analysis suggests benefit in a subgroup of patients. Thus, this subgroup analysis meets our previously suggested criteria for credibility.

Conduct of subgroup analyses in randomised controlled trials

We found that in both industry and non-industry funded trials, the proportion prespecifying subgroup hypotheses and reporting a test of interaction was low (table 3), suggesting that many fail to meet key methodological criteria in carrying out subgroup analyses. One study26 found that some so called “prespecified” subgroup analyses were not actually defined in the study protocols, suggesting that the proportion of real prespecified subgroup analyses may be even lower than reported. It is possible that trial investigators may, blinded to the trial data, prespecify subgroup hypotheses in the detailed statistical analysis plan, but not in the study protocol, before the trial is closed out, which represents an appropriate approach to a priori specification of subgroup hypotheses. However, in our sample, whatever was done elsewhere, most trial investigators failed to include this information in the study reports.

We also found that industry funded trials were less likely to prespecify subgroup hypotheses and were less likely to carry out the test of interaction, irrespective of whether the primary outcome was or was not statistically significant. These findings further support our hypothesis that trials funded by industry are more likely to look for positive subgroup findings, and suggest that, compared with non-industry funded trials, the quality of carrying out subgroup analyses is more questionable. On the other hand, with industry funded trials, subgroup analyses reported in journals may differ from those submitted to regulatory authorities. Typically, regulators require a prespecified statistical plan including subgroup analyses and caution about the claim of subgroup effects. Industry funded trials may choose to only report prespecified subgroup analyses and provide more details on the conduct and interpretation of subgroup analyses when submitting to regulatory authorities. However, the failure to disclose some of these trials’ results publicly has still hampered the unbiased assessment of the effect of treatments.27 28

Instead of using the test of interaction, many trials tested whether the results of each subgroup met the threshold for statistical significance.1 6 This approach to analysing subgroup effects fails to deal with the critical null hypothesis of subgroup analysis—that is, there is no difference in treatment effect between subgroups. The interaction test, which addresses the likelihood that chance explains the apparent differences in effect across subgroups, helps avoid spuriously positive subgroup findings.

Interpretation of subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses represent an effort to tackle heterogeneity of treatment effects. With appropriate design, conduct, and interpretation of studies, findings from subgroup analyses can provide crucial information that ultimately improves the management of patients. Subgroup analyses, however, pose many challenges. On the one hand, trials are rarely planned to detect subgroup effects, resulting in false negative findings for subgroups. On the other hand, trial investigators may carry out a large number of subgroup analyses without prespecifying subgroup hypotheses and without testing for interaction; as a result, subgroup analyses are often associated with false positive findings.4 29 30 31

The purposes of doing subgroup analyses vary. They may serve to generate important hypotheses (exploratory subgroup analyses). Indeed, there are examples of subgroup analyses that have generated important hypotheses that proved real when tested in subsequent randomised trials.32 33 Because, more often, such preliminary apparent subgroup findings ultimately prove spurious, a much higher standard is necessary to make definitive claims for subgroups—that is, confirmatory subgroup analyses.

To distinguish between true and spurious subgroup effects we have suggested a set of criteria that can systematically be applied.24 These criteria cover aspects of the design, conduct, and context of subgroup analyses. The more criteria subgroup analyses fulfil, the more likely the apparent subgroup effect is real. For instance, in an industry funded randomised trial discussing the effect of ivabradine versus placebo for patients with coronary artery disease and left ventricular systolic dysfunction on the composite primary outcome of cardiovascular mortality, admission to hospital for acute myocardial infarction or heart failure,34 the authors claimed a likely effect of treatment on reduction of admission to hospital for acute myocardial infarction, admission to hospital for acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina, and coronary revascularisation—all of which were secondary outcomes—in a subgroup of patients with a baseline heart rate of 70 or more beats/min. Applying our criteria, we found that, although authors prespecified subgroup hypotheses, provided external evidence consistent with their findings, and justified the biological rationale of their findings, they carried out a large number of subgroup analyses (probably 99), and failed to report the P value associated with the test for interaction. They also did not prespecify the direction of the interaction and check the independence of multiple significant subgroup effects. Failure to meet most criteria, particularly the large number of subgroup hypotheses done, and absence of statistically significant interaction, suggests the subgroup claim warrants a high degree of scepticism.

Limitations of the study

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, we did not search all medical journals and therefore our findings may not be applicable to journals outside our sample. We did, however, include all core clinical journals, which is a much wider spectrum of journals than previously studied. Secondly, all trials in our study were published in 2007, and our results may not be generalisable to other years. A previous study has, however, suggested a similar relative frequency of subgroup reporting from 1994 to 2004.6 Thirdly, we categorised trials as positive or negative according to the P value threshold of 0.05, and the approach to categorising trials may be questioned. However, most editors and authors still use such categorisation. Fourthly, we dichotomised the journals as high versus lower impact according to the total number of citations, and trials as industry funded versus non-industry funded. These categorisations ignore gradients both in impact and in industry influence. For instance, it may be expected that industry initiated projects would have substantial influence from industry on the interpretation and reporting of studies, whereas investigator initiated grants that obtained some industry support would have much less influence from industry. Our dichotomisation approach precluded exploring the impact of such gradients. Strengths of our study include the identification of a large cohort of randomised controlled trials acquired through a systematic search, use of standardised screening and data extraction forms as well as calibration exercises to enhance the consistency between reviewers, and prespecified hypotheses to guide our analyses.21

Conclusion

Randomised controlled trials published in high impact journals, with larger sample size, studying non-surgical topics, and with industry funding—if the primary outcome is not statistically significant—are associated with more frequent reporting of subgroup analyses. The proportion of trials prespecifying subgroup hypotheses and carrying out interaction tests for subgroup analyses is low in both industry funded and non-industry funded trials. Industry funded trials, regardless of the statistical significance of primary outcomes, less often prespecify subgroup hypotheses and less often use the interaction test for analyses of subgroup effects compared with trials that are not funded by industry. Our findings suggest that clinicians, reviewers, and journal editors should view all subgroup analyses with caution. Particular attention is warranted in industry funded trials with negative results for the primary outcome.

What is already known on this topic

Trial authors often report subgroup analyses

Larger trials are more likely to report subgroup analyses

A small proportion of trials prespecify subgroup hypotheses and use the formal test of interaction for subgroup analyses

What this study adds

Trials published in high compared with lower impact journals and non-surgical trials are more likely to report subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses are more likely to be reported by trials funded by industry than by non-industry funded trials, but only if the primary outcome is not statistically significant

Industry funded trials prespecify subgroup hypotheses and use the interaction test for analyses of subgroup effects less often than non-industry funded trials

We thank Monica Owen for administrative assistance and Aravin Duraikannan for developing the electronic data abstraction forms.

Contributors: XS and GHG conceived the study, had full access to all of the data in the study, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. GHG is the guarantor. XS, GHG, MB, JWB, EAA, SDW, DGA, and DH-A designed the study. MB, EAA, JWB, ND-G, JJY, FM, MMB, DB, DM, POV, GM, SKS, PD, BCJ, PA-C, BH, XS, JT, NDD, and NB acquired the data. XS, GHG, SDW, and DH-A analysed and interpreted the data. XS drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript. XS provided administrative and technical support. The funder had no role in the study design, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (project No 70703025). XS is supported by the Ontario graduate scholarship and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. MB is supported by santésuisse and the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation. JWB is funded by a new investigator award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation. DB is supported by the European Union (grant award health-F5-2009-223060). DM is supported by a research scholarship from the Swiss National Science Foundation (PBBSP3-124436). PD is supported by a Dennis W Jahnigan career development award by the American Geriatrics Society. BCJ holds a SickKids Foundation post-doctoral fellowship. PA-C is funded by a Miguel Servet contract by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CP09/00137). JJY is supported by a career scientist award from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (project No 70703025); no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;342:d1569

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendices 1-10

References

- 1.Assmann SF, Pocock SJ, Enos LE, Kasten LE. Subgroup analysis and other (mis)uses of baseline data in clinical trials. Lancet 2000;355:1064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Li P, Mah D, Lim K, Schunemann HJ, et al. Misuse of baseline comparison tests and subgroup analyses in surgical trials. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;447:247-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez AV, Boersma E, Murray GD, Habbema JD, Steyerberg EW. Subgroup analyses in therapeutic cardiovascular clinical trials: are most of them misleading? Am Heart J 2006;151:257-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pocock SJ, Hughes MD, Lee RJ. Statistical problems in the reporting of clinical trials. A survey of three medical journals. N Engl J Med 1987;317:426-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, Hunter DJ, Drazen JM. Statistics in medicine reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2189-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabler N, Duan N, Liao D, Elmore J, Ganiats T, Kravitz R. Dealing with heterogeneity of treatment effects: is the literature up to the challenge? Trials 2009;10:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guyatt G, Wyer PC, Ioannidis J. When to believe a subgroup analysis. In: Guyatt G, Rennie D, Meade MO, Cook DJ, eds. User’s guide to the medical literature: a manual for evidence-based clinical practice. 2nd ed. AMA, 2008:571-83.

- 8.Canadian Cooperative Study Group. A randomized trial of aspirin and sulfinpyrazone in threatened stroke. N Engl J Med 1978;299:53-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ 1994;308:81-106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisberg LA, Group TASS. The efficacy and safety of ticlopidine and aspirin in non‐whites. Neurology 1993;43:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorelick PB, Richardson D, Kelly M, Ruland S, Hung E, Harris Y, et al. Aspirin and ticlopidine for prevention of recurrent stroke in black patients: a randomized trial. JAMA 2003;289:2947-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perlis RH, Perlis CS, Wu Y, Hwang C, Joseph M, Nierenberg AA. Industry sponsorship and financial conflict of interest in the reporting of clinical trials in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1957-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorgensen AW, Hilden J, Gotzsche PC. Cochrane reviews compared with industry supported meta-analyses and other meta-analyses of the same drugs: systematic review. BMJ 2006;333:782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bodenheimer T. Uneasy alliance—clinical investigators and the pharmaceutical industry. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1539-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lesser LI, Ebbeling CB, Goozner M, Wypij D, Ludwig DS. Relationship between funding source and conclusion among nutrition-related scientific articles. PLoS Med 2007;4:e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nkansah N, Nguyen T, Iraninezhad H, Bero L. Randomized trials assessing calcium supplementation in healthy children: relationship between industry sponsorship and study outcomes. Public Health Nutr 2009;12:1931-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djulbegovic B, Lacevic M, Cantor A, Fields KK, Bennett CL, Adams JR, et al. The uncertainty principle and industry-sponsored research. Lancet 2000;356:635-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Als-Nielsen B, Chen W, Gluud C, Kjaergard LL. Association of funding and conclusions in randomized drug trials: a reflection of treatment effect or adverse events? JAMA 2003;290:921-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kjaergard LL, Als-Nielsen B. Association between competing interests and authors’ conclusions: epidemiological study of randomised clinical trials published in the BMJ. BMJ 2002;325:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ 2003;326:1167-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun X, Briel M, Busse J, Akl E, You J, Mejza F, et al. Subgroup analysis of trials is rarely easy (SATIRE): a study protocol for a systematic review to characterize the analysis, reporting, and claim of subgroup effects in randomized trials. Trials 2009;10:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Library of Medicine. Abridged index medicus (aim or “core clinical”) journal titles. 2008. www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/aim.html.

- 23.Thomson Reuters. Web of knowledge. 2011. www.isiwebofknowledge.com.

- 24.Sun X, Briel M, Walter SD, Guyatt GH. Is a subgroup effect believable? Updating criteria to evaluate the credibility of subgroup analyses. BMJ 2010;340:c117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boutron I, Dutton S, Ravaud P, Altman DG. Reporting and interpretation of randomized controlled trials with statistically nonsignificant results for primary outcomes. JAMA 2010;303:2058-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan A-W, Hrobjartsson A, Jorgensen KJ, Gotzsche PC, Altman DG. Discrepancies in sample size calculations and data analyses reported in randomised trials: comparison of publications with protocols. BMJ 2008;337:a2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med 2008;358:252-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouchie A. Clinical trial data: to disclose or not to disclose? Nat Biotech 2006;24:1058-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brookes ST, Whitely E, Egger M, Smith GD, Mulheran PA, Peters TJ. Subgroup analyses in randomized trials: risks of subgroup-specific analyses; power and sample size for the interaction test. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:229-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yusuf S, Wittes J, Probstfield J, Tyroler HA. Analysis and interpretation of treatment effects in subgroups of patients in randomized clinical trials. JAMA 1991;266:93-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Multiplicity in randomised trials ii: subgroup and interim analyses. Lancet 2005;365:1657-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aurora S, Dodick D, Turkel C, DeGryse R, Silberstein S, Lipton R, et al. Onabotulinumtoxina for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the preempt 1 trial. Cephalalgia 2010;30:793-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dodick DW, Mauskop A, Elkind AH, DeGryse R, Brin MF, Silberstein SD, et al. Botulinum toxin type a for the prophylaxis of chronic daily headache: subgroup analysis of patients not receiving other prophylactic medications: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache 2005;45:315-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, Tendera M, Ferrari R. Ivabradine for patients with stable coronary artery disease and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:807-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendices 1-10