Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the potential effects of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 monoclonal antibody (PCSK9-mAb) on high-sensitivity C reactive protein (hs-CRP) concentrations.

Design

A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.

Data sources

PubMed, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library databases, ClinicalTrials.gov and recent conferences were searched from inception to May 2018.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

All randomised controlled trials that reported changes of hs-CRP were included.

Results

Ten studies involving 4198 participants were identified. PCSK9-mAbs showed a slight efficacy in reducing hs-CRP (−0.04 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.17 to 0.01) which was not statistically different. The results did not altered when subgroup analyses were performed including PCSK9-mAb types (alirocumab: 0.12 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.18 to 0.43; evolocumab: 0.00 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.07 to 0.07; LY3015014: −0.48 mg/L, 95% CI: −1.28 to 0.32; RG7652: 0.35 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.26 to 0.96), treatment duration (≤12w: 0.00 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.07 to 0.07; >12w: −0.11 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.45 to −0.23), participant characteristics (familial hypercholesterolaemia: 0.00 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.07 to 0.07; non-familial hypercholesterolaemia: 0.07 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.12 to 0.26; mix: −0.48 mg/L, 95% CI: −1.28 to 0.32) and treatment methods (monotherapy: 0.00 mg/L, −0.08 to 0.07; combination therapy: −0.08 mg/L, −0.37 to 0.21). Meta-regression analyses suggested no significant linear correlation between baseline age (p=0.673), sex (p=0.645) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reduction (p=0.339).

Conclusions

Our updated meta-analysis suggested that PCSK9-mAbs had no significant impact on circulating hs-CRP levels irrespective of PCSK9-mAb types, participant characteristics and treatment duration or methods.

Keywords: PCSk9, monoclonal antibody, hs-CRP, meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis that gives an overview of the effect of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 monoclonal antibody (PCSK9-mAb) on inflammation.

An extensive systematic literature search identified all available randomised controlled trials that reported the changes of high-sensitivity C reactive protein using PCSK9-mAb.

Studies with moderate heterogeneity and lack of individual level data may limit the quality of evidence for this meta-analysis.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the greatest burden of global health, which is mainly characterised by atherosclerosis.1 Atherosclerosis is a chronic and progressive inflammatory disease, including endothelial dysfunction, lipid accumulation in the arterial wall and leucocyte infiltration, which leads to luminal stenosis, plaque rupture and acute coronary syndrome (ACS).2 Apart from well-established lipid theory, inflammation also plays an important role in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis.3 Recently, the Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study (CANTOS) reported that anti-inflammatory therapy by canakinumab, a therapeutic monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-1β, significantly reduced the primary cardiovascular end points.4 This study attracted attention to the inflammation intervention in cardiovascular medicine again.

C reactive protein (CRP), especially high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP), is the most intensively investigated inflammatory biomarker in cardiovascular field.5 Increasing studies have confirmed that hs-CRP is a predictor for the progression of atherosclerotic disease and future major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).6 7 Moreover, previous studies also indicated that hs-CRP played a direct role in the progression of atherosclerosis.8 9 Therefore, reduction of inflammatory markers such as hs-CRP may be a strategy for decreasing MACE.10 11

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) is known to target low-density lipoprotein receptor for degradation resulting in elevated plasma low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels.12–14 Recently, it has been reported that PCSK9 monoclonal antibody (PCSK9-mAb), as a novel lipid-lowering drug, can reduce LDL-C by a mean of 70% accompanied with reduction of MACE.15 Although the relation of PCSK9 to LDL-C has been established, its role in inflammation has not been fully understood. Several experimental studies found that PCSK9 could promote the progression of atherosclerosis by enhancing inflammatory reaction.16 On the other hand, PCSK9 deficiency could alleviate the inflammation reaction.17 Hence, whether PCSK9-mAb can reduce inflammatory marker is clinically of great interest since it was used to treat cardiovascular diseases. A meta-analysis covering seven randomised controlled trials (RCTs) studies published 2 years ago suggested that PCSK9-mAbs had no effect on serum hs-CRP.18 However, this meta-analysis may be limited by insufficient subgroup analyses, sample size and lack of newly published data.19 20 Hence, we performed this meta-analysis including all RCTs published till May 2018 to further explore the efficacy of PCSK9-mAbs on circulating hs-CRP levels.

Methods

Literature search

The present study is reported according to the guidelines of the 2009 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.21 To identify all RCTs assessing the effect of PCSK9-mAbs on circulating hs-CRP levels, we comprehensively searched PubMed, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library database and ClinicalTrials.gov up until May 2018. The search terms we used included the followings: (AMG145 or Evolocumab or REGN727 or SAR236553 or Alirocumab or RN316 or bococizumab or RG7652 or LY3015014 or PCSK9 antibody or anti-PCSK9) AND (randomized controlled trial OR randomized OR randomly). Meanwhile, manual search was performed for relevant studies including references lists, relevant review articles and commentaries (see online supplementary appendix 1). No language restriction was used.

bmjopen-2018-022348supp001.pdf (889.5KB, pdf)

Study selection

Original studies met the following criteria would be included: the design was phase 2 or phase 3 double-blind RCTs with longer than 8 weeks treatment duration; human participants were randomly assigned to PCSK9-mAbs group versus control group with or without other lipid-lowering therapy and outcomes included percentage changes of hs-CRP from baseline. Studies were excluded if they were duplicate publications, review articles, non-human studies, observational studies and lack of adequate information on outcomes or lacking control group. Two investigators (YC and SL) independently screened and selected the eligible studies. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third investigator.

Data extraction

A standardised extraction form was used to extract the following items by two investigators (YC and HL) independently: trial name/first author, year of publication, type of intervention, follow-up period, treatment duration, number of patients, participant characteristics, background lipid-lowering therapy, types and doses of PCSK9-mAbs, LDL-C and hs-CRP levels at baseline and changes. We included the final reported follow-up point if a trial contains several time points. If necessary, further information was required from correspondence author.

Quality assessment

We used Cochrane Collaboration’s tool and Jadad score to assess the data and the methodological quality of included RCTs. For Cochrane Collaboration’s tool, the following items were performed: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias) and other sources of bias. The judgments were classified as ‘low risk’, ‘high risk’ and ‘unclear risk’ of bias. The 5-point Jadad score included the following items: basis of randomisation (0 to 2 points), double blinding (0 to 2 points) and withdrawals/dropouts (0 to 1 points). Studies with a score ≥3 points are considered to be high quality. Two investigators (YC and HL) independently assessed the quality of each study. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third investigator.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted according to the intention-to-treat principles. For all efficacy outcomes, changes in hs-CRP concentrations were expressed as weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% CI. All the data were standardised and expressed by mg/mL. SD could be calculated from CI, IQR or SE according to formulas in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions if not reported.

Heterogeneity was assessed by the Cochran Q test and the I2 statistic. We considered I2 <25% as representing low heterogeneity and I2 >75% as representing at high heterogeneity. Outcomes were calculated by fixed-effects models under no or low to moderate inconsistency (I2 <50%); otherwise, the data were pooled based on random-effects models. Subgroups were applied to reduce the heterogeneity if I2 ≥50%, such as PCSK9-mAb types, treatment duration and participant characteristics. In order to explore the resource of heterogeneity, sensitivity analysis was conducted by omitting studies in turn to evaluate the consistency of the results. Meta-regression analyses were performed to evaluate the contribution of participant characteristics and reductions in LDL-C concentrations. Publication bias was assessed with a funnel plot and Egger’s test.

All analyses were conducted with Review Manager V.5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration) and Stata V.14.0 (Stata Statistical Software, Stata Corp). P value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement statement

Participants and the public sector were not directly involved in the design and conduct of this study.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

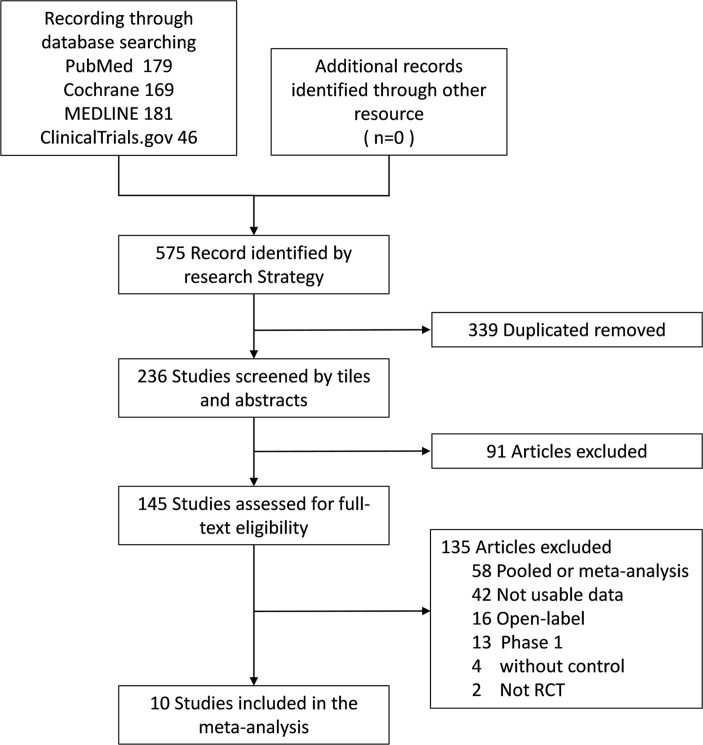

The initial search identified 575 articles. After excluding duplicate publications and screening the titles and abstracts, 430 were excluded, and 145 studies were retrieved for full-text identification. We further excluded 135 studies, of which 58 were pooled or meta-analysis, 2 studies were not RCTs and 13 was phase 1 trials, 16 were open-label trails and 42 without adequate information. Finally, 10 studies were included in this meta-analysis.20 22–30 Figure 1 shows flow diagram of selection process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of selection of studies.

These 10 studies were published between 2012 and 2017 from different countries with low risk of bias, of which 5 were phase 2 studies and 5 were phase 3 studies (table 1). A total of 4198 participants were included, comprising 2728 individuals in the PCSK9-mAb group and 1470 in the control group. Alirocumab (SAR236553/REGN727) was used in 4 arms and 11 arms applied evolocumab (AMG 145). Five arms managed LY3015014 and two arms used RG7652. Four trials included patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH), of which three were heterozygous FH and one was homozygous FH. Most of the treatment duration ranged from 12 to 24 weeks, and the longest treatment duration was 78 weeks. Apart from DESCARTES trial which coadministered with atorvastatin, another nine studies used PCSK9-mAb as monotherapy. Baseline characteristics including circulating hs-CRP levels were similar between PCSK9-mAbs and control groups within each study. The characteristics of these trials and participants are summarised in table 1. All these studies had a relatively high quality evaluated by the Jadad score and low risk of bias (online supplementary table 1 and online supplementary figures 1, 3 scores=5, six scores=4).

Table 1.

Study characteristics of included randomised controlled trials.

| Study | Year | Phase | Inclusion criteria | Patients (n) |

Arm | Mean age (years) | Male % |

Mean hs-CRP at baseline mg/L | hs-CRP reduction (mg/L) |

% LDL-C reduction | Drugs/control | Treatment duration | Jadad Score |

| RUTHERFORD22 | 2012 | II | HeFH | 167 | (1) | 47.6 | 54.5 | 1.09±1.37 | −0.06±0.94 | 42.7 | E:350 mg/PBO, Q4W | 12W | 5 |

| (2) | 51.8 | 62.5 | 1.07±1.24 | 0.00±0.30 | 55.2 | E:420 mg/PBO, Q4W | |||||||

| Stein EA 201224 | 2012 | II | HeFH | 77 | (1) | 56.3 | 81.3 | 1·40±1.78 | −0.40±2.04 | 67.9 | A:150 mg/PBO, Q2W | 12W | 5 |

| (2) | 51.3 | 60.0 | 0·60±0.82 | −0.20±0.81 | 28.9 | A:150 mg/PBO, Q4W | |||||||

| (3) | 52.9 | 56.3 | 0·70±1.48 | 0.00±1.29 | 31.5 | A:200 mg/PBO, Q4W | |||||||

| (4) | 54.3 | 46.7 | 0.70±0.59 | −0.10±0.84 | 42.5 | A:300 mg/PBO, Q4W | |||||||

| DESCARTES25 | 2014 | II | HC | 894 | (1) | 50.7 | 47.3 | 2.00±3.70 | 0.00±2.57 | 51.5 | E:420 mg/PBO, Q4W | 52W | 5 |

| (2) | 57.2 | 42.9 | 1.00±1.48 | 0.00±1.48 | 54.7 | E:420 mg+ATV 10 mg/PBO, Q4W | |||||||

| (3) | 57.8 | 52.4 | 1.00±1.48 | 0.00±1.48 | 46.7 | E:420 mg+ATV 80 mg/PBO, Q4W | |||||||

| (4) | 54.2 | 55.6 | 1.00±1.48 | 0.00±1.48 | 46.8 | E:420 mg+ATV 80 mg+Eze 10 mg /PBO, Q4W | |||||||

| GAUSS-226 | 2014 | III | HC | 307 | (1) | 61.0 | 55.3 | 1.40±2.00 | 0.30±2.67 | 56.1 | E:140 mg/Eze, Q2W | 12W | 4 |

| (2) | 63.0 | 54.9 | 1.80±1.78 | −0.30±1.78 | 52.6 | E:420 mg/Eze, Q4W | |||||||

| RUTHERFORD-223 | 2014 | III | HeFH | 329 | (1) | 52.6 | 40.0 | 0.92±1.03 | −0.05±0.39 | 61.3 | E:140 mg/PBO, Q2W | 12W | 4 |

| (2) | 51.9 | 41.8 | 1.04±1.24 | 0.03±0.73 | 55.7 | E:420 mg/PBO, Q4W | |||||||

| TESLA Part B27 | 2014 | III | HoFH | 49 | 31.0 | 51.5 | 0.70±1.04 | −0.02±0.52 | 23.1 | E:140 mg/PBO, Q4W | 12W | 4 | |

| ODYSSEY COMBO II28 | 2015 | III | HC | 720 | (1) | 61.7 | 75.2 | 3.58±7.78 | −0.39±6.95 | 50.6 | A: 75 mg/Eze, Q2W | 24W | 4 |

| (2) | 61.7 | 75.2 | 3.58±7.78 | −0.07±8.57 | 51.8 | A: 75 mg/Eze, Q2W | 52W | ||||||

| GLAGOV29 | 2016 | III | HC | 968 | 59.8 | 72.1 | 1.60±1.93 | −0.40±10.67 | 60.8 | E:420 mg/PBO, Q4W | 78W | 4 | |

| Kastelein 201620 | 2016 | II | HC | 519 | (1) | 57.2 | 51.7 | 1.03±1.41 | −0.20±2.07 | 14.9 | LY:20 mg/PBO, Q4W | 16W | 4 |

| (2) | 57.1 | 52.3 | 1.34±1.11 | 1.60±2.00 | 40.5 | LY:120 mg/PBO, Q4W | |||||||

| (3) | 59.7 | 54.7 | 1.63±1.78 | −0.30±2.00 | 50.5 | LY:300 mg/PBO, Q4W | |||||||

| (4) | 59.6 | 58.1 | 1.39±1.70 | −0.30±2.07 | 14.9 | LY:100 mg/PBO, Q8W | |||||||

| (5) | 58.7 | 50.6 | 1.10±1.63 | −0.70±2.07 | 37.1 | LY:300 mg/PBO, Q8W | |||||||

| EQUATOR30 | 2017 | II | HC | 168 | (1) | 65.0 | 57.9 | 1.60±2.70 | 0.34±1.93 | 23.3 | RG:400 mg/PBO, Q4W | 24W | 4 |

| (2) | 64.0 | 51.0 | 2.00±5.90 | −0.16±2.92 | 44.3 | RG:800 mg/PBO, Q8W |

Data presented as mean ±SD.

A, alirocumab; ATV, atorvastatin; DESCARTES, Durable Effect of PCSK9 Antibody Compared with Placebo Study; E, evolocumab; EQUATOR: Safety and Efficacy of MPSK3169A in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease or High Risk of Coronary Heart Disease; Eze, ezetimibe; GAUSS-2, Goal Achievement after Utilizing an Anti[1]PCSK9 Antibody in Statin Intolerant Subjects-2; GLAGOV, Global Assessment of Plaque Regression With a PCSK9 Antibody as Measured by Intravascular Ultrasound; HC, hypercholesterolaemia; HeFH, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia; HoFH, homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL-C, low -density lipoprotein cholesterol; LY: LY3015014; ODYSSEY COMBO II: Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in high cardiovascular risk patients with inadequately controlled hypercholesterolaemia on maximally tolerated doses of statins; RG, RG7652; RUTHERFORD, Reduction of LDL-C With PCSK9 Inhibition in Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia Disorder; RUTHERFORD-2, Reduction of LDL-C With PCSK9 Inhibition in Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia Disorder-2; PBO, placebo; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks; W, weeks.

Efficacy outcomes of PCSK9-mAbs on hs-CRP

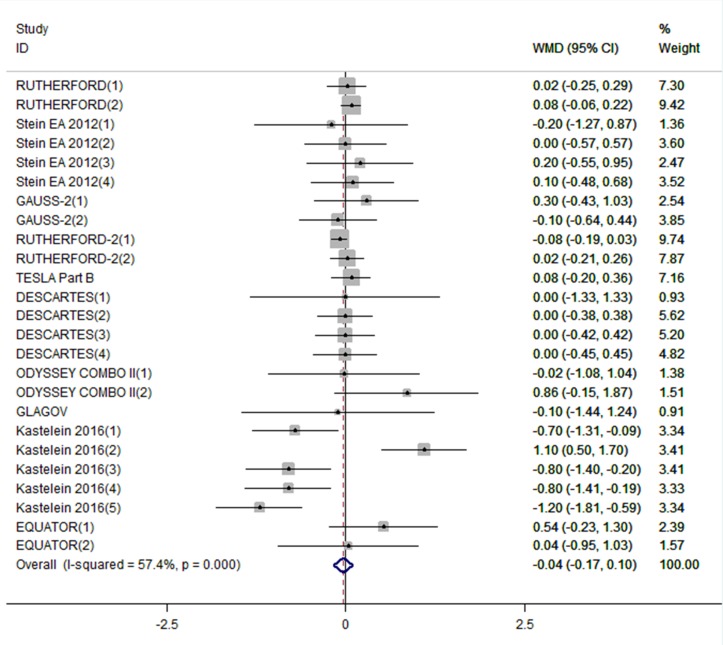

A total of 4198 participants were included in the analysis of efficacy of PCSK9-mAbs on plasma hs-CRP concentrations before and after treatment. When data were pooled, PCSK9-mAbs showed a slight efficacy in reducing hs-CRP (WMD: −0.04 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.17 to 0.01), while no statistical difference was found compared with control treatment (figure 2). There was a moderate heterogeneity between each study (I2=57.4%, p=0.0001), so the random-effect model was selected.

Figure 2.

Forest plots depicting the effect of PCSK9-mAbs on hs-CRP. PCSK9-mAb, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) monoclonal antibody; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

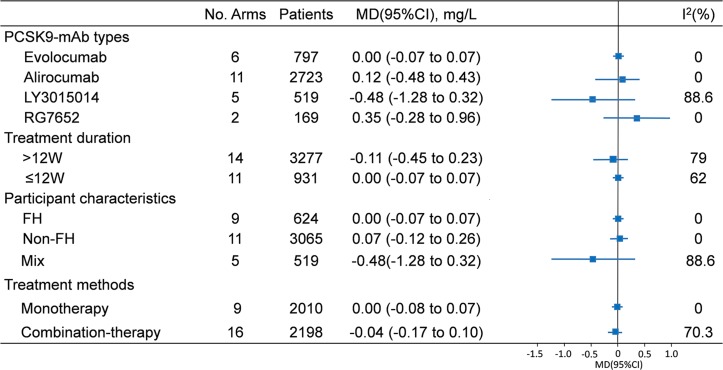

To assess the potential discrepancy, we applied the subgroup analyses based on the characteristics of trials and participants (figure 3 and online supplementary figures 2–5). Although the efficacy of LY3015014 was a mild higher (−0.48 mg/L, 95% CI: −1.28 to 0.32), there was no difference between these four antibodies (alirocumab: 0.12 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.18 to 0.43; evolocumab: 0.00 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.07 to 0.07; RG7652: 0.35 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.26 to 0.96). When studies were classified by treatment duration, the hs-CRP reduction showed no difference in less than 12-week duration group (0.00 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.07 to 0.07) and above 12=week duration group (−0.11 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.45 to −0.23). There was no significant reduction in circulating hs-CRP with use of PCSK9 antibodies compared with control treatment when categorised to participant characteristics (FH: 0.00 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.07 to 0.07; non-FH: 0.07 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.12 to 0.26; mix: −0.48 mg/L, 95% CI: −1.28 to 0.32). The analysis stratified by treatment method also supported the results that no differential effect of PCSK9-mAb therapy on plasma hs-CRP concentrations was observed (monotherapy: 0.00 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.08 to 0.07 vs combination therapy: −0.08 mg/L, 95% CI: −0.37 to 0.21).

Figure 3.

Subgroup analyses of the effect of PCSK9-mAbs on hs-CRP. PCSK9-mAb, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) monoclonal antibody; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; FH, familial hypercholesterolaemia; non-FH, non-familial hypercholesterolaemia.

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

The sensitivity analysis for all outcomes was conducted by gradually removing each study. However, the results did not change meaningfully (online supplementary figure 6). Neither funnel plots (online supplementary figure 7) nor Egger’s regression test (p=0.913) showed publication bias.

Meta-regression analyses

We used meta-regression analyses to assess the relationship between changes in hs-CRP and baseline age, sex and average LDL-C changes (online supplementary figure 8). No statistically significant relationship between baseline age (p=0.673), male sex (p=0.645) and hs-CRP changes was observed. Likewise, LDL-C-lowering effects by PCSK9-mAb therapy had no impact on hs-CRP lowering (p=0.339, online supplementary figure 8).

Discussion

The results of this updated, comprehensive meta-analysis, based on 10 RCTs encompassing 4198 participants, suggested that short-term PCSK9-mAb therapy had no impact on circulating hs-CRP concentrations. In the subgroup analyses, no difference was found between PCSK9-mAb types, participant characteristics and treatment duration or methods.

Atherosclerosis, a chronic progressive disorder, is characterised by lipid accumulation and chronic inflammation in the arterial wall.2 Although previous data indicated a positive effects of anti-inflammatory drugs on atherosclerosis in animal studies, but no positive data were available in human studies.31 Fortunately, recent evidence from CANTOS found that canakinumab significantly reduced hs-CRP levels and MACE after follow-up of 3.7 years which may support the inflammatory hypothesis of atherosclerosis.4 Moreover, ongoing Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial was also designed to directly test the inflammatory hypothesis of atherosclerosis by evaluating the effect of methotrexate on adverse cardiovascular outcomes without substantive impact on lipids.32 Hence, focusing on inflammation in the development of atherosclerosis may be an unsolved issue and great of interest clinically.

In fact, increasing studies indicated that hs-CRP could independently predict MACE.6 Framingham study found that men and women in the highest quartile of CRP respectively had twice and three times the risk of stroke compared with those in the lowest ones after more than 10 years follow-up.33 The Northern Manhattan Study reported that >3 mg/L CRP was associated with a 1.7-fold increase in cardiovascular outcomes and a 1.55-fold increase in mortality.34 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that hs-CRP also plays a direct and vital role in the development of atherosclerosis. Zwaka et al 8 found that CRP enhanced the transformation from macrophages to foam cells by increasing the uptake of LDL-C. CRP was also reported to impair vasodilatation, inhibit the synthesis of nitric oxide synthase and facilitate the adhesion of monocyte.35 36 Based on these evidence, reduction of hs-CRP may be associated with a decrease in MACE. Interestingly, the JUPITER (Justification for the Use of statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin) study applied rosuvastatin on individuals with LDL-C levels below 130 mg/dL and hs-CRP levels ≥2 mg/L and suggested a significant reduction in all vascular events.37 Although a fact that statins lower LDL-C and proportionately reduce MACE is widely accepted, the hs-CRP reduction by statin administration is also an attractive phenomenon, called as pleiotropic effect of statin. That is the reason why we chose hs-CRP as an inflammatory biomarker to identify whether PCSK9-mAb has an effect on inflammatory status.

Although the relationship between PCSK9 and LDL-C was well established, more and more evidence demonstrated its function beyond lipids. In 2010, microarray gene expression analysis suggested that PCSK9 affected cholesterol metabolism and inflammation.38 Experimental studies indicated that PCSK9 could participate in vascular and systemic inflammation.16 In transgenic mice expressing human PCSK9 gene, Tavori et al 39 observed that atherosclerosis lesion size and local Ly6Chi monocytes, the precursors of proinflammatory M1 macrophages, significantly increased. Clinical studies further supported this hypothesis. Our previous study found that serum PCSK9 concentrations were independently associated with white blood cell count in patients with stable coronary artery disease, indicating PCSK9 might be involved in the inflammation process.40 ATHEROREMO-IVUS (The European Collaborative Project on Inflammation and Vascular Wall Remodeling in Atherosclerosis - Intravascular Ultrasound) study reported a positive linearly association between PCSK9 levels and coronary plaque inflammation including amount of necrotic core tissue and plaque volume.41 On the other hand, data also showed that PCSK9 inhibition could exert an anti-inflammatory effect. Tang et al 42 reported that PCSK9 small interfering RNA reduced the expression of proinflammatory genes through nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway. In apoE−/− mice, PCSK9 silencing limited the development of atherosclerosis and decreased the number of macrophages via toll-like receptor 4-nuclear factor-kappa B (TLR4/NF-κB) signalling pathway.43 Besides, AT04A anti-PCSK9 vaccine also got the same results that anti-PCSK9 therapy could reduce vascular inflammation.44 Recently, Bernelot Moens et al 45 found that after 24 weeks of treatment with PCSK9-mAbs, the migratory capacity of monocytes and inflammatory responsiveness reduced significantly while anti-inflammatory cytokine levels increased in patients with FH. Therefore, we hypothesised that PCSK9-mAbs treatment could reduce hs-CRP in randomised clinical studies. Unfortunately, in our meta-analysis, the results showed that PCSK9-mAbs therapy had no effect on decreasing hs-CRP in both FH participants and non-FH individuals.

To explore the potential reasons why PCSK9-mAbs therapy was not benefit from inflammatory marker, named as the reduction of circulating hs-CRP levels, we further performed subgroup analyses. First, we did not observe an impact of PCSK9-mAbs types on hs-CRP, which may exclude the influence of PCSK9-mAbs itself on the inflammatory marker in our meta-analysis. Besides, the same results were also observed in combination of statins and PCSK9-mAbs group, suggesting that the effects of PCSK9-mAbs therapy on hs-CRP is not linked with treatment methods. It is notable that the participants in JUPITER trial had high levels of hs-CRP at baseline, while in PCSK9-mAb therapy, initial hs-CRP levels were at normal range in recruited individuals. Finally, we did not find a positive effects of PCSK9-mAbs therapeutic duration on hs-CRP in this updated analysis. Taken together, we may conclude that although PCSK9-mAbs had a powerful ability in lowering LDL-C, they had no impact on circulating hs-CRP concentration despite of PCSK9-mAb types, participant characteristics and treatment duration or methods.

Limitations

There were several limitations in our meta-analysis. First, our results were based on study data but not individual data as in most meta-analyses. Second, although our meta-analysis is an updated one, it is still limited by study numbers, sample size and therapy duration. Moreover, moderate degree of heterogeneity was observed in several comparisons. However, there was no publication bias, and the results were rather consistent among different subgroups. Sensitivity analysis suggested that the pooled WMD were robust. Finally, some studies included in this meta-analysis did not provide adequate information about blinding of participants and personnel.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the current updated evidence suggested that PCSK9-mAb, a novel powerful lipid-lowering drug, had no significant impact on circulating hs-CRP concentrations, whose effect did not influenced by PCSK9-mAb types, participant characteristics and treatment duration or methods. Long-term observation may be needed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: J-JL: contributed to conception and design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. Y-XC: contributed to design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation and drafted the manuscript. SL: contributed to acquisition, analysis and critically revised the manuscript. H-HL: contributed to analysis, interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was partially supported by the Capital Health Development Fund (201614035) and CAMS Major Collaborative Innovation Project (2016-I2M-1-011) awarded to J-JL. The sponsors had no role in the decision to conduct the meta-analyses, data analysis or reporting of the results.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3:e442 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ross R. Atherosclerosis — an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 1999;340:115–26. 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Packard RR, Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from vascular biology to biomarker discovery and risk prediction. Clin Chem 2008;54:24–38. 10.1373/clinchem.2007.097360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, et al. . Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1119–31. 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li JJ, Fang CH. C-reactive protein is not only an inflammatory marker but also a direct cause of cardiovascular diseases. Med Hypotheses 2004;62:499–506. 10.1016/j.mehy.2003.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li JJ, Li S, Zhang Y, et al. . Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin type 9, C-Reactive protein, coronary severity, and outcomes in patients with stable coronary artery disease: a prospective observational cohort study. Medicine 2015;94:e2426 10.1097/MD.0000000000002426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang A, Liu J, Li C, et al. . Cumulative exposure to high-sensitivity c-reactive protein predicts the risk of cardiovascular disease. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e005610 10.1161/JAHA.117.005610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zwaka TP, Hombach V, Torzewski J. C-reactive protein-mediated low density lipoprotein uptake by macrophages: implications for atherosclerosis. Circulation 2001;103:1194–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.103.9.1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang YX, Cliff WJ, Schoefl GI, et al. . Coronary C-reactive protein distribution: its relation to development of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 1999;145:375–9. 10.1016/S0021-9150(99)00105-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li JJ, Fang CH. Effects of 4 weeks of atorvastatin administration on the antiinflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 in patients with unstable angina. Clin Chem 2005;51:1735–8. 10.1373/clinchem.2005.049700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li JJ, Li YS, Fang CH, et al. . Effects of simvastatin within two weeks on anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 10 in patients with unstable angina. Heart 2006;92:529–30. 10.1136/hrt.2004.057489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cui CJ, Li S, Li JJ. PCSK9 and its modulation. Clin Chim Acta 2015;440:79–86. 10.1016/j.cca.2014.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li S, Li JJ, Jj L. PCSK9: A key factor modulating atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb 2015;22:221–30. 10.5551/jat.27615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li S, Zhang Y, Xu RX, et al. . Proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 as a biomarker for the severity of coronary artery disease. Ann Med 2015;47:386–93. 10.3109/07853890.2015.1042908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roth EM, McKenney JM, Hanotin C, et al. . Atorvastatin with or without an antibody to PCSK9 in primary hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1891–900. 10.1056/NEJMoa1201832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Giunzioni I, Tavori H, Covarrubias R, et al. . Local effects of human PCSK9 on the atherosclerotic lesion. J Pathol 2016;238:52–62. 10.1002/path.4630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kühnast S, van der Hoorn JW, Pieterman EJ, et al. . Alirocumab inhibits atherosclerosis, improves the plaque morphology, and enhances the effects of a statin. J Lipid Res 2014;55:2103–12. 10.1194/jlr.M051326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sahebkar A, Di Giosia P, Stamerra CA, et al. . Effect of monoclonal antibodies to PCSK9 on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels: a meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled treatment arms. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016;81:1175–90. 10.1111/bcp.12905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gencer B, Montecucco F, Nanchen D, et al. . Prognostic value of PCSK9 levels in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2016;37:546–53. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kastelein JJ, Nissen SE, Rader DJ, et al. . Safety and efficacy of LY3015014, a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9): a randomized, placebo-controlled Phase 2 study. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1360–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Raal F, Scott R, Somaratne R, et al. . Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol-lowering effects of AMG 145, a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 serine protease in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: the Reduction of LDL-C with PCSK9 Inhibition in Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia Disorder (RUTHERFORD) randomized trial. Circulation 2012;126:2408–17. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.144055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Raal FJ, Stein EA, Dufour R, et al. . PCSK9 inhibition with evolocumab (AMG 145) in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (RUTHERFORD-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:331–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61399-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stein EA, Gipe D, Bergeron J, et al. . Effect of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9, REGN727/SAR236553, to reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia on stable statin dose with or without ezetimibe therapy: a phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380:29–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60771-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blom DJ, Hala T, Bolognese M, et al. . A 52-week placebo-controlled trial of evolocumab in hyperlipidemia. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1809–19. 10.1056/NEJMoa1316222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stroes E, Colquhoun D, Sullivan D, et al. . Anti-PCSK9 antibody effectively lowers cholesterol in patients with statin intolerance: the GAUSS-2 randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial of evolocumab. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2541–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Raal FJ, Honarpour N, Blom DJ, et al. . Inhibition of PCSK9 with evolocumab in homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (TESLA Part B): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:341–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61374-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cannon CP, Cariou B, Blom D, et al. . Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in high cardiovascular risk patients with inadequately controlled hypercholesterolaemia on maximally tolerated doses of statins: the ODYSSEY COMBO II randomized controlled trial. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1186–94. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nicholls SJ, Puri R, Anderson T, et al. . Effect of evolocumab on progression of coronary disease in statin-treated patients: the glagov randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;316:2373–84. 10.1001/jama.2016.16951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baruch A, Mosesova S, Davis JD, et al. . Effects of RG7652, a monoclonal antibody against PCSK9, on LDL-C, LDL-C subfractions, and inflammatory biomarkers in patients at high risk of or with established coronary heart disease (from the Phase 2 EQUATOR Study). Am J Cardiol 2017;119:1576–83. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, et al. . Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med 1997;336:973–9. 10.1056/NEJM199704033361401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Everett BM, Pradhan AD, Solomon DH, et al. . Rationale and design of the cardiovascular inflammation reduction trial: a test of the inflammatory hypothesis of atherothrombosis. Am Heart J 2013;166:199–207. 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rost NS, Wolf PA, Kase CS, et al. . Plasma concentration of C-reactive protein and risk of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack: the Framingham study. Stroke 2001;32:2575–9. 10.1161/hs1101.098151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Elkind MS, Luna JM, Moon YP, et al. . High-sensitivity C-reactive protein predicts mortality but not stroke: the Northern Manhattan Study. Neurology 2009;73:1300–7. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bd10bc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li L, Roumeliotis N, Sawamura T, et al. . C-reactive protein enhances LOX-1 expression in human aortic endothelial cells: relevance of LOX-1 to C-reactive protein-induced endothelial dysfunction. Circ Res 2004;95:877–83. 10.1161/01.RES.0000147309.54227.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Paffen E, DeMaat MP. C-reactive protein in atherosclerosis: A causal factor? Cardiovasc Res 2006;71:30–9. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. . Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2195–207. 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lan H, Pang L, Smith MM, et al. . Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) affects gene expression pathways beyond cholesterol metabolism in liver cells. J Cell Physiol 2010;224:273–81. 10.1002/jcp.22130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tavori H, Giunzioni I, Predazzi IM, et al. . Human PCSK9 promotes hepatic lipogenesis and atherosclerosis development via apoE- and LDLR-mediated mechanisms. Cardiovasc Res 2016;110:268–78. 10.1093/cvr/cvw053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li S, Guo YL, Xu RX, et al. . Association of plasma PCSK9 levels with white blood cell count and its subsets in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2014;234:441–5. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cheng JM, Oemrawsingh RM, Garcia-Garcia HM, et al. . PCSK9 in relation to coronary plaque inflammation: Results of the ATHEROREMO-IVUS study. Atherosclerosis 2016;248:117–22. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tang Z, Jiang L, Peng J, et al. . PCSK9 siRNA suppresses the inflammatory response induced by oxLDL through inhibition of NF-κB activation in THP-1-derived macrophages. Int J Mol Med 2012;30:931–8. 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tang ZH, Peng J, Ren Z, et al. . New role of PCSK9 in atherosclerotic inflammation promotion involving the TLR4/NF-κB pathway. Atherosclerosis 2017;262:113–22. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Landlinger C, Pouwer MG, Juno C, et al. . The AT04A vaccine against proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 reduces total cholesterol, vascular inflammation, and atherosclerosis in APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2499–507. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bernelot Moens SJ, Neele AE, Kroon J, et al. . PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies reverse the pro-inflammatory profile of monocytes in familial hypercholesterolaemia. Eur Heart J 2017;38:1584–93. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022348supp001.pdf (889.5KB, pdf)