ABSTRACT

In this article, we draw on the theoretical and empirical literature to name what appear to be core dimensions of successful young adult development. We also describe some possible indicators and measures of those dimensions and sketch the kinds of developmental relationships and opportunities young people need in adolescence to effectively transition to a successful young adulthood, as well as the developmental relationships and opportunities young adults need for continued well-being. We name eight social, psychological, behavioral, educational, occupational, health, ethical, and civic dimensions of successful young adult development, and suggest that only a minority of adolescents are well-prepared to make a transition to successful young adulthood. The goal of the article is twofold: to contribute to the articulation of and consensus on the dimensions of successful young adult development, and to lay the groundwork for subsequent research to empirically validate both those core dimensions, as well as developmental indicators of progress toward attainment of these proposed dimensions of well-being.

Promoting the healthy development of children and adolescents requires a clear vision of successful young adult development, that is, articulation of the dimensions and indicators of what constitutes well-being in the next stage of development for which children and adolescents are preparing. There is a growing concern about what is happening in the lives of young adults. Certainly, there is no lack of problems in young adulthood to address, from the continuing problem of underage drinking on college campuses (Grant, Moore, Shepard, & Kaplan, 2003; Littlefield & Sher, 2010) to the stubborn challenge of only half of college entrants actually completing college (Arnett, 2004; Settersten & Ray, 2010), a trend that threatens the nation’s ability to compete globally, or the historically high unemployment rate among young adults (Taylor et al., 2012).

But, as for the first two decades of life, preventing problems is only part of the picture of successful young adulthood, the other part being their positive functioning. Recognizing that definitions of developmental “success” will vary by cultural context, we posit that there is a core set of questions about young people’s preparedness for young adulthood that, if not universally salient, are likely still to have considerable validity across significant diversity of national and cultural context throughout the world. That is, these questions, we believe, are valid guideposts for thinking about young adult human development. These include: How prepared are young adults to assume meaningful societal roles? Are they prepared for work, learning, and life? Are they prepared to become parents, good neighbors, productive workers, and engaged citizens in a time when the challenges of globalization, the digital information and communications revolution, and upheavals in the world economy are demanding even more of them? By what criteria and with what indicators might we answer such questions?

Purpose of the article

In this article, we draw on the theoretical and empirical literature to name core dimensions of successful young adult development, dimensions that largely are based on a strength-based approach to human development. We also describe some possible indicators and measures of those dimensions, and sketch the kinds of developmental relationships and opportunities young people need in adolescence to effectively transition to a successful young adulthood, as well as the developmental relationships and opportunities young adults need for continued well-being. The current article grew out of a joint project of Search Institute and the Social Development Research Group at the University of Washington, which was conducted in 2004 for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Our goal was to create a consensus statement on the dimensions and indicators of successful young adult development that would help to benchmark and monitor change over time in samples of young adults, inform the design of child and adolescent prevention and promotion programs, and provide a conceptual frame for establishing earlier developmental indicators of progress toward these proposed outcomes in young adulthood. Subsequent additions were made to the original document, based on Search Institute’s work in pilot testing a new survey measuring developmental assets in college students (Pashak & Handal, 2011, 2013; Pashak, Handal, & Scales, under review), and a re-examination and revision of the article by the original authors, including integration of more recent pertinent literature. The criteria for identifying the dimensions of successful young-adulthood development were articulated as follows. The dimensions should:

Be solidly reflected in the theoretical and research literature;

Reflect a public consensus about what is important;

Be useful for multiple purposes, including public communications and mobilization, program development and evaluation, individual planning, and community, state, and national tracking;

Be measurable; and

Be amenable to change over time.

The lens we used to examine dimensions of successful young adult development has its limitations, because it reflected both the dominant literature and its reliance on samples from developed countries, as well as our own situatedness and relative success in the mainstream of majority culture in the United States. Inevitably, any framework that defines developmental success rests on cultural values, norms, and assumptions, both implicit and explicit, about what attitudes, skills, behaviors, life paths, and achievements are desirable, valued, and worthy of societal investment to nurture. The dimensions we put forward in this article thus are most rooted in the normative and aspirational gestalt of majority culture in the West, and especially, the United States. No set of dimensions of developmental success, for any life stage, possibly can be entirely valid for all imaginable variations of class, gender, sexual orientation, racial-ethnic, and religious, diversities, among others. What successful development looks like, and how it is evaluated as such by oneself and socially-valued others, surely is different at some level for a poor first-generation immigrant, religiously Catholic, straight Latina young adult working as a migrant farm worker in central California, than it is for an affluent, native-born, university-educated, gay, Indian young adult man working at a large bank and living in the suburbs of London. Consequently, we presume that the valence ascribed to the dimensions of successful development we propose, and how they are manifested, will differ according to the complex cultural situatedness of each individual young adult. Nevertheless, we believe, and present evidence to suggest, that the dimensions described, if not necessarily all the possible indicators and measures we mention, have broad applicability cross-culturally, both within the United States and globally. This is largely because, as we expand upon later, our proposed dimensions of successful young adult development fundamentally reflect the basic tenets of self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), namely, the individual’s need for autonomy, belonging, and competence, that capture basic developmental processes which transcend culture alone.

Before presenting the dimensions that resulted from this process and the illustrative indicators for measuring them, we consider some salient issues around the character of young adulthood and the transition to this stage, including evidence that suggests adolescents, not just in the United States, but around the world, are not as developmentally prepared for successfully transitioning into this critical period as would be desirable.

The character of young adulthood

The period of growth from adolescence to adulthood is an important time of life in its own right and is also significant because it sets the stage for later adult life (Arnett, 2000; George, 1993; Hogan & Astone, 1986; Shanahan, 2000). We consider young or emerging adulthood roughly to be defined as the timespan from approximately age 18 to age 25. Others have argued that the emerging adulthood period persists as late as age 29 (Arnett, Kloep, Hendry, & Tanner, 2011), and the international youth development field routinely considers “youth” to cover the period from early adolescence to age 30 or even slightly beyond (USAID, 2012). But age ranges are not wholly satisfying markers, of course, since different people in the same age range have been found to consider themselves truly “adult.” For example, the label “emerging” has been applied to those who do not think of themselves as so fully adult, and the label “young” adult to those in the same age range who do think of themselves as adult (Blinn-Pike, Worthy, Jonkman, & Smith, 2008). Emerging adulthood also has a specific reference to the work of Arnett (2000, 2004) and colleagues (Arnett et al., 2011), which suggests psychological perceptions of independence and autonomy may mark the period more than do sociological markers such as assumption of new roles and responsibilities. We should note, too, that the very use of “independence” as a marker of young adult “success” is itself highly correlated with cultural contexts that prize such status, and may be problematic in other national, racial/ethnic, or religious cultures that accord greater value to familism and interdependence, issues we will discuss further in the following sections. In this article, we use the term “young adulthood” to refer simply to a specific time in the life course, and to allow for what the literature seems also to suggest, that both psychological self-perceptions and sociological markers are definitionally salient in this period.

Regardless of the label used, the transitional issues are substantial because the fragile process of personal development gets tested anew during young adulthood. The vast majority of young people in developed countries, and increasingly, in developing ones, even those who experience good levels of structural support and internal resources in their middle and high school years, will change their relationships with most if not all of their socializing systems. They often move out of the house or out of town, hundreds and even thousands of miles away, for education and work (such as the migration of rural youth to rapidly growing urban areas in many developing countries—Lall, Selod, & Shalizi, 2006), and for advantaged young people, for romantic relationships or exploration. They change or leave schools. They often change peer groups, and all their other socializing networks, including religious congregations and other community organizations, usually are also affected. Those who do not continue on in their schooling after high school may now be working full-time, if they are lucky enough to find a job, or in the military, or spending much of their time looking for a job. Others may continue living with their parents, a trend that has greatly increased in the United States since the Great Recession (Taylor et al., 2012), and that appears also to be quite common in post-Communist European countries (Lyman, 2015), but feel they deserve more independence, with a consequent desire to renegotiate rules and norms. Or they may be living away from home for the first time, away from family, peer groups, and familiar institutions of neighborhoods, schools, youth organizations, and congregations. The research is clear in showing that young adults, more frequently than any other age group, experience significant changes to core aspects of identity such as location of residence, relationship status, and worldview (Arnett, 2000, 2004).

Periods of extraordinary societal events can affect these developmental realities in profound ways. For example, the Pew Research Center’s nationally representative surveys of adults found that because of the Great Recession that began in late 2007, fewer young adults were employed (46–48% post-recession) than at any time since the late 1940s, and that 10–33% of young adults had made economic-related adjustments such as moving back in with their parents, postponing getting married or having a baby, or moving in with a roommate (Taylor et al., 2012; Wang & Morin, 2009). Both the expected changes in young adults’ roles and settings, and unusual changes triggered by wider trends affect developmental relationships—relationships that provide care, support, challenge, expanded possibilities, and sharing of power (Li & Julian, 2012; Pekel, 2013; Pekel, Roehlkepartain, Syvertsen, & Scales, 2015; Scales, 1999) that are principal sources of young people’s positive strengths and the promotion of core developmental processes of agency, identity, and commitment to community. This suggests that far greater intentionality in helping young people and their socializing systems deal with that shift in relationships, contexts, demands, and opportunities is vital for a successful transition to young adulthood. Disparities marked by socioeconomic status, immigration status, gender, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity within a society can also affect these developmental realities and strongly affect successful transition to adulthood (cf, J. L. Benson & Elder, 2011; Castro et al., 2011, Hardaway & McLoyd, 2009). For example, about 3% of African-American males ages 18–24 are imprisoned in the United States (twice the rate of Hispanics and six times the rate for Whites), a status that strongly affects education, earnings, family formation, physical and mental health, and positive civic engagement (America’s Young Adults, 2014). Youth and young adults who identify as LGBT have been found to be at higher risk of physical and mental health problems, including depression and suicide, but also to benefit from similar protective factors as straight youth and young adults, including family connectedness, caring adults, and safety in their schools and colleges (Institute of Medicine, Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, 2011). Youth from the lowest quintiles of family income are more likely to have sexual experience in their teens than higher-income youth (especially males), and to cohabit and marry earlier in their young adult years, raising their likelihood of divorce and its destructive economic sequelae (Meier & Allen, 2008). In addition, first-generation immigrant youth who attend college are more likely to be older, work at least part-time, and be from lower socioeconomic strata, all of which are linked to less likely completion of college (Staklis & Horn, 2012). More positively, first- and second-generation immigrant youth, compared to their third-generation peers, start out with lower BMIs and are significantly less likely to experience physical problems due to overweight and obesity in young adulthood (Jackson, 2011).

Young adulthood is most often described in terms of the new roles and statuses adopted in this stage of life. Leaving the parental home to establish one’s own residence, establishing financial independence, completing school, moving into full-time employment, getting married, and becoming a parent are often considered key markers of adulthood (Booth, Crouter, & Shanahan, 1999; Cohen, Kasen, Chen, Hartmark, & Gordon, 2003; George, 1993; Macmillan & Eliason, 2003; Shanahan, 2000). Studies have identified three major groups of young adults who follow different pathways marked by indicators of education, employment, marriage, cohabitation, parenthood, and residence (Macmillan & Eliason, 2003; Oesterle, 2013; Oesterle, Hawkins, Hill, & Bailey, 2010; Oesterle, Hawkins, & Hill, 2011; Osgood, Ruth, Eccles, Jacobs, & Barber, 2005; Sandefur, Eggerling-Boeck, & Park, 2005; Schulenberg, O’Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 2005).

The first major group includes young adults who move early into forming their own families (as teenagers) and invest very little in post-secondary education. The timing of first parenthood distinguishes a second group, those who have children somewhat later as young adults, beginning in the early and mid-20 s. They also invest relatively little in postsecondary education in favor of involvement in full-time work. A third major group includes those who invest in education, employment, and career development first and postpone family formation until their late 20 s or early 30 s, if not even later. Some of these pathways differ markedly by gender as more women than men are on the track of very early family formation and often outside the context of marriage (Cohen et al., 2003; Macmillan & Eliason, 2003; Oesterle et al., 2010; Osgood et al., 2005; Schulenberg et al., 2005). In the United States, women are three times more likely than men to have their first child before the age of 20 (33 vs. 11%, respectively), while more men than women become a parent for the first time between age 25 and 29 (32 vs. 19%, respectively, Child Trends, 2002). In 2011, the mean age in the United States at the birth of the first child was 25.6 years for mothers (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf) and 27.4 years for fathers (http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file99036.pdf). These mean ages, of course, mask the quite different paths combining education and family formation that differing groups of young adults take, as noted above. In their longitudinal study of more than 800 urban young adults followed from 5th grade into their 30 s, for example, Oesterle et al. (2010) found that more than 40% of both men and women invested in postsecondary education and postponed family formation, making that the most common path. However, sizable percentages also were unmarried through age 30 but had limited investment in postsecondary education (27% of women and 26% of men), or were married and had children early, but did not invest much in higher education (29% of women and 32% of men). These latter two groups, neither of which invested as much in postsecondary education, were, when added, the majority of the sample, even though within that majority they had quite different trajectories of family formation. The existence of different family-formation and educational-investment groups also directs attention to the possibility that some elements of success during this period may look different for the three groups. Some criteria of success are life course- or role-dependent, applying only to those who take on a particular role, such as parent. For example, while becoming a parent is an important marker of adulthood, it is not a criterion for successful adaptation in itself. It is a common choice to not have children or to have them later in life (Heaton, Jacobson, & Holland, 1999). For those who do have children, however, being a competent parent and enjoying a positive relationship with one’s child are important criteria of successful adult development. For those in post-secondary education, positive connections in educational institutions are important. These role-dependent dimensions of successful adulthood affect the choice of indicators for measuring successful early-adult development. For example, as just described, positive, supportive relationships are important for all young adults, but, if one is a parent, having a meaningful relationship with one’s child is specifically critical for well-being.

Transitions to and from young adulthood

Leaving familiar roles of childhood and adolescence and taking on new responsibilities of worker, spouse, or parent can be challenging. Negotiating this transition successfully has positive consequences. Most often, transitions encourage continuity, reinforcing developmental patterns already established in childhood and adolescence (Elder & Caspi, 1988; Oesterle, 2013). For example, avoiding substance use and delinquency in adolescence decreases the risk for antisocial involvement in young adulthood and poor physical and mental health (Guo, Collins, Hill, & Hawkins, 2000; Guo et al., 2002; Hill, White, Chung, Hawkins, & Catalano, 2000; Mason et al., 2004; Newcomb & Bentler, 1988; Oesterle et al., 2004). The conditions and characteristics that put people on a positive trajectory early in life can help them negotiate later transitions such as entering adolescence and young adulthood.

The transition to young adulthood also may vary by culture (within and across societies), gender, and historical era, among other considerations (Hogan & Astone, 1986; Furstenberg & Kmec, 2000). For example, Cote and Bynner (2008) note that delay of family formation was a common life path in the 19th century, albeit among a different social group than is common in the 21st century: “ … in the nineteenth century it was common for the servant class to postpone marriage and parenthood into their thirties: such postponement is now true of the ‘student class,’ the opposite in terms of socio-economic status and resources … ” (p. 252). Similarly, Johnson and Reynolds (2013) showed that an important reason why lower SES youth have much lower college completion rates than their higher SES peers is that their greater probability of early marriage, parenthood, and full-time employment lowers over time their expectations for getting into and completing college. In contrast, higher SES youths’ expectations for college completion stay strong through young adulthood, thereby helping to propel them to completion in greater percentages.

Transition periods can also function as turning points, providing opportunities for change from negative to more positive developmental pathways in subsequent developmental periods (Elder 1985, 1998; Feinstein & Bynner, 2004; Maughan & Rutter, 1998; Nagin, Pagani, Tremblay, & Vitaro, 2003; Rutter, 1996; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002; Schulenberg, Maggs, & O’Malley, 2003; Wheaton, 1990). In early adulthood, for example, marriage, pregnancy (or having a pregnant spouse), and being a parent appear to reduce involvement with drugs (Bachman, Wadsworth, O’Malley, Johnston, & Schulenberg, 1997; Oesterle et al., 2011). Marriage has also been associated with young men’s subsequent reduction in crime (Sampson & Laub, 1993; Warr, 1998). Helping children, adolescents, and young adults negotiate transitions successfully is a fundamental societal task. Nevertheless, effective intervention and prevention programs targeted to young adults appear to be few in number, and narrow in scope. For example, Oesterle (2013) reviewed eight major inventories of programs, including SAHMSA’s National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Policies, and Social Programs That Work from the Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy, and found only two-dozen well-tested programs, more than half focusing primarily or solely on substance use. She concluded that few programs promote young adult life skills, such as relationship skills or understanding of finances, and most overlook the non-college population.

Those program gaps for helping young people transition effectively to young adulthood are especially critical, since a minority of teenagers currently seem well prepared to make that transition. Several data sources indicate that sizeable proportions of young people have moderate levels of developmental relationships and opportunities, but only a minority enjoys a high level. Search Institute studies show that 37% of 6th-12th graders in a 2010 sample of nearly 90,000 students from 26 states experienced 21-30 of 40 Developmental Assets, such as a caring school climate, positive family communication, opportunities to serve others, high expectations, and positive role models (P. L. Benson, Scales, Roehlkepartain, & Leffert, 2011). Although the factor structure of the 40 assets only partially aligns with the a priori eight-asset category framework (e.g., Theokas et al., 2005), the total number of the assets a youth reports, which we use here, has repeatedly been found to be linked to numerous indicators of well-being, in both cross-sectional (e.g., Scales et al., 2005) and longitudinal studies (e.g., Scales et al., 2006). The National Promises Study done by Search Institute, Child Trends, and Gallup for the America’s Promise Alliance (America’s Promise Alliance, 2007; Scales et al., 2008) found that 48% of the nation’s 12–17 year olds experienced 2-3 of the five Promises shown to be related to well-being (caring adults, safe places, healthy start, effective education, and opportunities to make a difference). And the Teen Voice 2010 study Search Institute conducted with Harris Interactive for the Best Buy Children’s Foundation showed that 55% of the nation’s 15 year olds experienced one or two of three developmental “strengths” studied, which included “sparks” or deep passions and interests; relationships and opportunities to develop those sparks and interests, and voice or empowerment (Scales, Benson, & Roehlkepartain, 2011).

However, all three of these studies show, with remarkable consistency, given their different questions, methods, and samples, that it is uncommon for adolescents to have high levels of these developmental nutrients. Only 11% of 6th-12th graders experience 31–40 of the 40 Developmental Assets, only 9% of 12–17 year olds experience all five Promises, and only 7% of 15 year olds experience high levels of all three Teen Voice strengths. At the same time as assets levels are low, environmental risks are high in adolescence, especially for substance use, unsafe sexual behavior, and violence. Given that studies repeatedly show high levels of these assets being associated with better well-being, in terms of both prevention of these risk behaviors and in terms of thriving behaviors, both in cross-sectional (P. L. Benson et al., 2011; P. L. Benson, Scales, & Syvertsen, 2011) and longitudinal studies (Scales, Benson, Roehlkepartain, Sesma, & van Dulmen, 2006), adolescents’ modest levels of individual and social assets, whether operationalized as the 40 developmental assets, the 5 Promises, or the 5C’s of caring, competence, character, connection, and confidence (seen as leading to a 6th C, contribution: Lerner et al., 2005; Pittman, Irby, & Ferber, 2001) do not bode well for a successful transition to young adulthood, either for the prevention of risk behaviors or the promotion of thriving. In terms of the cultural generalizability of this conclusion, data from studies of more than 25,000 adolescents and young adults from more than two-dozen mostly developing countries, including large proportions of disadvantaged youth, report similar results: These individual and social assets are correlated significantly and at substantively meaningful effect sizes, both cross-sectionally and over time, with numerous outcomes measuring academic, occupational, psychological, social, civic, and behavioral well-being among young people globally, and the average level of the assets among youth and young adults in these international samples can best be described as barely above the vulnerable level (Scales, 2011; Scales, Roehlkepartain, & Fraher, 2012; Scales, Shramko, & Ashburn, in press; Scales, Roehlkepartain, & Shramko, under review). In noting these results, we emphasize that socioeconomic disadvantage was simply one dimension of cultural diversity represented in this vast database. The 44 samples across 29 countries reflected great variations in racial-ethnic composition, gender, gender norms of the country, educational and literacy levels, geography, religions, languages, national economic development, stability of government, and armed conflict, post-conflict, or non-conflict status, among other diversities. The similarity of barely adequate experience of developmental relationships and opportunities, and of the relation between higher levels of those nutrients and better well-being across such significant diversity of cultures, lends credence to our conclusion that the majority of adolescents worldwide likely are not as well-positioned as desirable for a successful transition to young adulthood.

Moreover, studies have shown that young people’s experience of developmental assets goes down in adolescence, on average. Although most of that decline occurs over 6th–9th grades, with some recovery noticeable by 12th grade (Roehlkepartain, Benson, & Sesma, 2003; Scales et al., 2006), a majority of young people in their last year of high school are largely still lacking adequate levels of these foundational building blocks of life success. Data from two sources, an aggregate sample of nearly 90,000 6th–12th graders from 26 U.S. states (P. L. Benson et al., 2011), and a longitudinal study that included a small cohort of 118 St. Louis Park, Minnesota 8th grade students followed to 12th grade (Roehlkepartain et al., 2003), help illuminate the decreasing assets available to youth as they reach the point of transition to young adulthood. In both the cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, similar trends are observed: 12th graders report experiencing criterion levels of just 19 of the 40 assets, or 48%, in the large cross-sectional sample, and just 18 of the assets, or 45%, in the St. Louis Park sample. In other words, most of the assets are experienced by only a minority of high school seniors.

We would hope that seniors in high school, who are on the cusp of young adulthood, would be doing better than younger students on the developmental relationships and opportunities they experience. But when comparing 12th graders to all students in Search Institute’s 2010 aggregate sample, 12th graders were no better than adolescents as a whole (better by at least five percentage points), or were worse off (by five percentage points or more), on 35 (88%) of the assets. In the longitudinal sample, the results were more positive, but still, 12th graders were no better, or were worse off, on 25 of the assets (63%).

Despite the differences in research design, method, and sample size, the 2010 large cross-sectional study and the St. Louis Park longitudinal study converge on this conclusion: Although much of the loss of assets has stopped by the time they graduate from high school, their next big developmental transition period to young adulthood is now just beginning with the typical high school senior experiencing only one third to one-half of the assets at developmentally adequate levels, and, on most of the assets, high school seniors are no better or even worse off than they were when they were younger.

In addition, the longitudinal St. Louis Park study showed that most of the assets showing decreases or lack of improvement are among the “external” assets, the developmental relationships and opportunities provided by others. This suggests that families, schools, youth organizations, religious congregations, and neighborhoods are falling short at preparing young people for leaving high school, transitioning to college, work, or the military, and for many, leaving home. Thus, the majority of young people head into the significant developmental transition to young adulthood—which by itself creates greater potential for vulnerability and a need for sound developmental supports and internal strengths—just at the time when those developmental supports are shaky at best. This developmental vulnerability is apparent across diversity of social class, gender, race/ethnicity, and urbanicity, but has been found to be greatest among youth from lower-SES backgrounds (P. L. Benson et al., 2011).

Very-early family formation clearly makes successful development in young adulthood difficult. Early parenthood is associated with a lower likelihood of marriage, a greater risk of divorce or separation, and less full-time work (Macmillan & Eliason, 2003). It hinders completion of high school and also continuation in post-secondary education. Even allowing that there is cultural variation in what defines successful young adulthood, it can hardly be advantageous in general for a young person to have less education, less stable marriages, and less employment earnings than her or his peers. Recent research supports the conclusion from earlier studies that very early family formation lowers the well-being of those mothers in young adulthood, for example by increasing the risk for substance misuse in young adulthood (Oesterle et al., 2011), and worsens outcomes for their children (Furstenberg, 2003; Haggstrom, Kanouse, & Morrison, 1986; Hardy, Astone, Brooks-Gunn, Shapiro, & Miller, 1998; Jones, Astone, Keyl, Kim, & Alexander, 1999; Upchurch, 1993). Children from poverty disproportionately join the early-family-formation group, while children from homes with adequate incomes are more likely to invest in completing post-secondary education (Furstenberg, 2003; Kerckhoff, 1993; Oesterle et al., 2010). Young people with lower levels of developmental relationships and opportunities in high school already are at greater risk of poorer concurrent and subsequent outcomes, and these differences are further exacerbated by the kinds of disparities in the opportunity structures of society that poverty and very early family formation reflect. There is of course no question that many youth from disadvantaged circumstances have other strengths, notably relationships with family and/or mentors, which help them to be resilient and succeed in their transition to young adulthood by common (majority culture) standards of success. However, structural issues such as racism, discrimination, and poverty clearly make it far more challenging. As Stanton-Salazar (2011) noted, majority-status and more affluent young people typically have more access to both socialization in mainstream expectations and the social capital of relationships with mentors who can not only teach effective strategies for social mobility and career development, but sometimes even pull levers to open doors for those young people. Therefore, developmental relationships with teachers and other adults have the potential to provide authentic empowerment of youth of color, working-class, and lower-income youth, by increasing their access to those kinds of relational influences that go beyond caring, to helping those young people stretch, expand, and become more savvy and powerful in the workings of the world. That is, such developmental relationships, useful for all youth, may be especially relevant for increasing the social capital that helps low-income students, students of color, and other historically marginalized young people have more options for dealing with these systemic limitations on their opportunities and making a successful transition to young adulthood (Scales, Pekel, Syvertsen, & Roehlkepartain, 2015).

A large longitudinal study of Australian young adult women showed the importance of these transitions. The researchers (Lee & Garmotnev, 2007) found that those young adults who moved out of work or schooling, or remained out of work or school, experienced increased depression. In general, those who became mothers or were out of the workforce had higher stress and depression initially and greater increases over the study period, whereas those who remained childless, moved to their own independent residence, continued in study or work, or moved into a couple relationship, experienced increases in life satisfaction. A Belgian study, however, showed that a given transition—or lack of it—per se, is not always the determining factor of well-being. Rather, the developmental processes at play may be more important for vitality, satisfaction, and other subjective measures of well-being. In that study (Kins, Beyers, Soenens, & Vansteenkiste, 2009), young adults living in their parents’ home did report less subjective well-being, but the contribution to life satisfaction evaporated if they had an autonomous motivation for living there. If they felt they had freely chosen to do so, their life satisfaction was greater than if they felt they had little choice in where they lived.

The developmental reality that individuals do not merely have their environment imposed on them, but interact with and shape the environments that influence them, also contributes to a variety of pathways to adulthood (P. L. Benson, Scales, Hamilton, & Sesma, 2006; Lerner et al., 2005; Osgood et al., 2005; Schulenberg et al., 2005; Shanahan, 2000; Werner & Smith, 2001). Given all these influential factors, it is not surprising that there are multiple paths to successful young adulthood. Person-centered longitudinal analyses, for example, have identified several classes of trajectories in important developmental activities and processes over the transition to young adulthood, from general and ethnic identity development (Luyckx, Schwartz, Goossens, Soenens, & Byers, 2008; Syed & Azmitia, 2009) to antisocial behavior (Monahan, Steinberg, Cauffman, & Mulvey, 2009), and sexual behavior (Lansford et al., 2010). To be sure, the acquisition of new roles in young adulthood and the re-centering of identity can take a diverse array of forms. Therefore, transitional success must be defined in such a way that acknowledges and assesses a diversity of relevant factors. For example, having the educational and economic achievements that allow one to escape the “toxic” neighborhood of one’s adolescence may be seen as a marker of success by majority culture standards, but among many people of color, may be seen as a selfish divorcing of oneself from one’s community unless successful members of those cultures use their success to give back to those communities to help in improving them (W. K. Kellogg Foundation, 2012). Similarly, graduation from high school or community college may be seen by working-class young women as freeing and exhilarating because it has prepared them for specific jobs, whereas graduation from college, an obviously “higher” level of achievement, may be seen by middle- and upper-class young women as filled with anxiety and uncertainty because they have used college more to explore their identities than to prepare for particular kinds of work (Aronson, 2008). The dimensions of young adult success we identify in the next section are intended to be specific enough to generate useful indicators, but general enough to allow for this kind of variety in ways of attaining them, and the meaning attached to them as filtered through individual young adults’ specific cultural locations and connections.

Dimensions and indicators of successful young adulthood

Initially working independently, Search Institute identified seven constructs and the Social Development Research Group identified 10 constructs, rooted in extensive reviews of the literature on young adulthood, with associated indicators, that were deemed to be developmentally valid for young adults reflecting a variety of life paths. SDRG and SI developed a consensus around eight constructs taking into account the sources, our individual working documents, and our discussions about the important kinds of positive outcomes for young adults, regardless of the life course they take to move toward those outcomes. The following list summarizes the consensus of SDRG and SI on key dimensions of success in young adulthood, which we then elaborate in the pages that follow including comments on illustrative indicators and measures of those dimensions:

Consensus Dimensions of Successful Young Adulthood:

Physical health,

Psychological and emotional well-being,

Life skills,

Ethical behavior,

Healthy family and social relationships,

Educational attainment,

Constructive educational and occupational engagement,

Civic engagement.

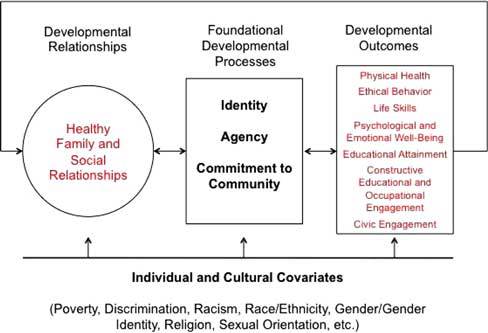

Figure 1 illustrates one possible way in which the dimensions may be linked, in a dynamic, bidirectional system in which they are both causes and effects of each other. We conceive of the relationships dimension—developmental relationships experienced in family and other social interactions—as the crucial formative experiences that contribute to the evolution and maturation of foundation developmental processes derived from self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), namely a sense of identity (paralleling SDT’s autonomy), a sense of agency (competence), and a commitment to community (relatedness/belonging). Ultimately, these foundational developmental processes may be seen as promoting the other dimensions of successful young adulthood (developmental outcomes), some of which are readily thought of more as statuses (e.g., educational attainment, occupational engagement), and some of which also reflect qualities of developmental processes that are always evolving and changing in the person ↔ context system (e.g., psychological and emotional well-being, ethical behavior, life skills).

Figure 1.

Links among the dimensions of successful young adulthood.

Our list of dimensions of successful young adulthood, originally developed in 2004, is quite similar to a later list developed by the Pathways Mapping Initiative at Harvard University, that named as desired outcomes young adults who were: effectively educated, embarked on or prepared for a productive career, physically, mentally, and emotionally healthy, active participants in civic life, and prepared for parenting (Schorr & Marchand, 2007). This effectively echoes our dimensions of physical health, psychological and emotional well-being, life skills, ethical behavior, healthy family and social relationships, educational attainment, constructive educational and occupational engagement, and civic engagement. That two independent efforts arrived at such similar places suggests a high degree of validity for this set of outcome dimensions defining successful young adulthood.

In the following pages, we elaborate on the salient sub-constructs included in this conceptualization, and note suggestions for measurement indicators. However, we first repeat that this list of dimensions of developmental success, or any other such naming of markers of success, reflects implicit and explicit values and a degree of cultural situatedness that mean the validity of these dimensions of success might not be generalizable to all young people in all cultural contexts. Moreover, our dimensions certainly reflect, on the surface, majority culture values in the United States of the early 21st century. Nevertheless, these dimensions are likely to be valid and valued across a large majority of diversities and contexts. For example, Benet-Martinez and Hong (2014) note that bicultural integration of both one’s unique and majority cultures tends to be related to better psychological adjustment than does assimilation to majority culture. However, they also note that the particularities of context, such as policies that promote or dampen specific types of acculturation, can lead to assimilation being a preferred strategy. Thus, Castro et al. (2011) found that life satisfaction among Latino men was greatest among those who strived for greater assimilation into “White American culture” and upward socioeconomic mobility. Likewise, Smokowski and Bacallao (2011) reported that the strongest positive effects of biculturalism on internalizing problems and self-esteem were seen among Latino youth with the highest levels of involvement with majority (i.e., non-Latino) U.S. culture. Similarly, recent studies of socioeconomically and racially/ethnically diverse samples of U.S. adults have found strong consensus across diversities on the importance of character or life skills such as responsibility (Pekel, Roehlkepartain, Syversten, & Scales, 2015), which young adults themselves also describe as a marker of being a young adult (Arnett, 2000).

One can also critique our young adulthood success dimensions on the grounds that they represent examples merely of adjustment to dominant culture standards of individualism and materialism rather than of successful development as an agentic organism. Here too, we believe the dimensions themselves, albeit not always specific measures of them, are sufficiently general to encompass both adjustment to dominant culture norms, and carving out of developmentally agentic personal and sub-cultural paths that can also include involvement in efforts to change those dominant culture norms through civic and political engagement. Moreover, we explicitly name several dimensions that reflect connection and concern with others (e.g., healthy relationships, ethical behavior, civic engagement), and ground other dimensions (e.g., life skills, psychological and emotional well-being) within a context of relatedness and mutual obligation that would contradict a simple evaluation of these dimensions as individualistic.

Finally, it is important to note that these dimensions do not denote or connote “pure,” unattainable ideals of behavior or psychological self-perceptions. We mean these to be quite reflective of real young adults living real lives that have the ups and downs of fortune and mood, and positive and negative experiences, that are inevitable parts of life for everyone. Our first sentence under Physical Health states successful young adults maintain a healthy lifestyle; however, this does not mean they are, or even should be, risk-free. Rather, they have attained greater skills at managing developmentally-appropriate risks (otherwise known, less pejoratively, as explorations, adventures, or experimentations) such that they minimize harm to themselves and others. Nor are psychologically healthy young adults free of sadness, self-doubt, or worries. Rather, they are essentially satisfied with their lives, and able to take steps to deal as effectively as they can with problems, disappointments, and challenges.

Physical health

Successful young adults are not risk-free but do maintain a healthy lifestyle. Indeed, a high degree of risk-taking in the use of alcohol, tobacco, and drugs (and driving under the influence) and in sexual behavior persists and even peaks in this age period (Neinstein, 2013). But, successful young adulthood involves increasing skill at minimizing and managing such risks by adopting healthy behaviors. Many of these behaviors have long-term impact by reducing risks of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and mortality. The leading causes of deaths for this age group are unintentional injuries (many from motor vehicle accidents), violence (homicide), and suicide (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2007). Some of the most important health behaviors during young adulthood are the avoidance of binge drinking and use of tobacco and illegal drugs, engaging in safe driving habits (including always using a seat belt and not driving under the influence of alcohol, marijuana, or other drugs), and avoiding violent behavior (including partner violence, child maltreatment, and non-intimate partner violence, e.g., getting into fights). If sexually active, successful young adults protect themselves from unplanned pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases (e.g., by always using condoms), and minimize their participation in casual sexual encounters, which have been found to be linked to higher incidences of sexually transmitted infections and sexual victimization, as well as lower psychological well-being, among college students ages 18–25 (Bersamina et al., 2013; Fielder, Walsh, Carey, & Carey, 2013).

Partner violence may be assessed through the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996), a self-report measure of 20 items to assess psychological and physical attacks on a partner in a marital, cohabiting, or dating relationship. Child maltreatment may be assessed through the parallel Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998), a self-report measure of 27 items assessing psychological aggression, physical assault, nonviolent discipline, and neglect. Non-intimate interpersonal violence may be assessed through 10 items of self-reported frequency of involvement in violence (e.g., picking fights, assault, robbery, rape, threatening serious violence) in the past year (cf., Herrenkohl et al., 2004; Mason et al., 2004). Research has shown that self-reports of delinquency and crime are reliable and valid (Hindelang, Hirschi, & Weis, 1981).

As previously noted, to be successful in this dimension, young adults need not abstain from substance use, particularly legal substances. But they do need to manage their use in ways that allow them to live adequate lives with regard to their important relationships, and educational and occupational commitments. To determine whether they are successful in so managing substance use, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) describes diagnostic criteria for substance disorder that define a meaningful, clinically significant outcome measure. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS: Robins et al., 1999) can be used to determine those meeting criteria for substance disorder in young adulthood (Guo et al., 2000; Guo, Hawkins, Hill, & Abbott, 2001).

Successful young adults eat a nutritious and healthy diet, attend to regular exercise and fitness, manage body weight to avoid overweight and obesity, and get adequate sleep. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) provides relevant recommendations and criteria for healthy diet, weight, exercise, and sleep (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2000). For example, healthy weight is indicated by a Body Mass Index (BMI) of less than 25 and a waist circumference of 35 inches or less for women and 40 inches or less for men. A healthy level of physical activity includes at least 2.5 hours of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week. A healthy sleep pattern is defined by about 8 hours of sleep per night (National Center on Sleep Disorder Research and Office of Prevention, Education, and Control, 1997). Successful young adults also seek regular preventive health care (e.g., regular physical check-ups, vaccinations, and preventive dental care) and necessary treatment (including smoking cessation and treatment for mental health and alcohol and drug abuse problems). Unfortunately, a major barrier to achieving physical health and safety during young adulthood is a lack of access to preventive care and treatment and few health-related guidelines targeting young adults in the United States. Young adults are the most uninsured age group in the United States and rely heavily on emergency services (Neinstein, 2013). The Affordable Care Act has addressed this gap by expanding health care coverage for young adults; however, gaps in coverage are likely to remain (Institute of Medicine & National Research Council, 2013).

Psychological and emotional well-being

Successful young adults are satisfied with the path their lives are on or they are able to do something about improving that path. They are essentially happy people who accept themselves and have adequate levels of self-efficacy to deal with their problems as well as to set and persist in pursuing positive educational, occupational, and relationship goals, including the ability to be “mentally tough” and resilient in the face of disappointment. They are confident and have a positive outlook. More often than not they show positive emotions instead of negative ones. They are developing a sense of purpose, which Damon et al. (2003) have defined as a stable intention to accomplish something meaningful to them and that is consequential to others. They are prosocial, that is, they have a disposition toward being involved with others and doing things to help others (also see section on social relationships).

There are several valid and reliable ways of assessing these aspects of psychological and emotional well-being using self-ratings (Zaff & Hair, 2003). Life satisfaction, positive outlook, and sense of purpose can be assessed through self-report scales (Damon et al., 2003; Keyes & Waterman, 2003), including the Personal Growth Initiative scale (PGI; Robitschek et al., 2012), the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Pavot & Diener, 2009), and the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ, Steger et al., 2006). The Life Orientation Test – Revised (LOT-R; Scheier et al., 1994) measures optimism. Although they are for adults in general, not young adults specifically, the Values in Action Institute has developed reliable 5-item measures on a variety of character strengths, including forgiveness, hope, and humility (Diener et al., 2010). A 3-item reliable measure of hopeful purpose, adapted from Damon, Menon, and Bronk (2003) has been developed by P. L. Benson and Scales (2009) as part of their overall measure of thriving orientation, including items such as “I have a sense of purpose or meaning in my life,” and “I feel hopeful when I think about my future.” Prosocial orientation has been assessed through a brief measure combining attitudes toward helping others and behavioral intentions to act on them in the coming year (Scales & Benson, 2004a). Schulenberg et al. (2005) assessed positive self-identity in young adults by combining self-esteem, self-efficacy, and social support, with self-rated items such as “I feel I am a person of worth.” In addition, Search Institute’s brief (3-4 items) measures for the developmental assets of self-esteem, sense of purpose, and positive view of the future have been found to have acceptable reliability in a sample of 450 college undergraduates (Pashak et al., under review).

Life skills

Ultimately, healthy adults have an array of skills for negotiating their environment successfully. These include emotional, cognitive, and social competences, such as those defined by a recent report on successful young adult development from the University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research: self-regulation, awareness, reflection on or making meaning out of experiences, critical thinking skills, responsible decision making, and collaboration with others (Nagaoka et al., 2015). Arnett (2000) noted that rather than gauging by status markers such as marriage or parenthood, people generally say being an adult is more about taking responsibility for oneself and making independent decisions. Successful young adults increasingly can take care of themselves, make decisions independent of, but for some cultural groups in discussion with their parents (including decisions about residence, finances, romance, and parenting), coordinate multiple life roles, and adapt flexibly and with reasonable emotional self-control to life’s opportunities and challenges. They exhibit several interpersonal skills including competence with respect to initiating relationships, asserting displeasure with others, disclosing personal information, providing emotional support and advice, and managing interpersonal conflict. They show evidence of increasing financial responsibility, which includes not squandering or wasting money needed to make ends meet, paying bills, and saving (Arnett, 2000; Cohen et al., 2003). They know how to plan and carry out plans, how to solve problems that get in the way, and how to deal with disappointments while still pursuing their immediate and longer-term goals through the decisions they make.

Measures of self-efficacy, mastery, and internal control are available, including the Pearlin Mastery Scale (Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman, & Mullan, 1981; Pearlin & Schooler, 1978) and Bandura’s (1977, 1982, 1997) self- efficacy measures and measures of internal vs. external locus of control (Levenson, 1974; Rotter, 1966). The concept of self-efficacy and mastery is measured using statements such as “I can do just about anything I really set my mind to,” “When I really want to do something, I usually find a way to succeed at it,” and “What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me.”

Problem-solving and decision-making skills can be measured following Fogler and LeBlanc (1995), who describe the problem-solving process as proceeding in several steps, including defining the problem, generating solutions through brainstorming and other methods, deciding on a course of action, and implementing a solution. Intentional self-regulation is a key aspect of such decision-making skills, and might be measured through an adaptation for young adults of the goal Selection, Optimization, and Compensation measure used by Gestsdottir and Lerner (2007).

Emotional self-control can be measured using Rothbart’s effortful-control dimension of the Adult Temperament Questionnaire (ATQ; Derryberry & Rothbart, 1988; Rothbart, Ahadi, & Evans, 2000). It measures the capacity to focus and shift attention when desired, to suppress inappropriate behavior, and to perform an action even when there is a strong tendency to avoid it. Another way of assessing impulse control is the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-Brief; Steinberg et al., 2013), which uses statements such as “I plan tasks carefully,” “I do things without thinking,” and “I act on the spur of the moment.”

Interpersonal skills can be assessed using Buhrmester et al.’s (Buhrmester, Furman, Wittenberg, & Reis, 1988) Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire (ICQ). It assesses several dimensions of interpersonal skills including competence with respect to initiating relationships, asserting displeasure with others, disclosing personal information, providing emotional support and advice, and managing interpersonal conflict. Positive emotionality is also an important contributor to satisfying interpersonal relationships, and a brief reliable measure has been developed by P. L. Benson and Scales (2009), including such statements as “I have a positive attitude,” and “I am an optimistic person.” Finally, financial responsibility can be assessed by asking young adults questions about the occurrence of “spending sprees” that caused financial trouble or a period of “foolish decisions about money” and about squandering or wasting money that was “needed to make ends meet” (Kosterman et al., 2005).

Ethical behavior

Successful young adults demonstrate through their behavior such values as integrity, caring for others, and being honest. They are ethical, trustworthy, helpful, responsible people who obey the law and comply with common social norms and adult rules of conduct (Arnett, 1998; Bachman et al., 1997; Jessor, Donovan, & Costa, 1991; Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, 2004). Does this mean they never break the speed limit or knowingly tell a lie? Of course not. Ethical young adults are not saints, but they are essentially people whose behavior helps maintain or increase sense of community, civic respect, and the ability of themselves and others to peacefully pursue their goals in life. Ethical young adults are not morally blind and unconcerned; they may engage in civil disobedience against laws they consider unfair or unjust, or work lawfully for changes in laws and customs that discriminate or marginalize themselves or others. They would be described by most others as having “good character” (Kosterman et al., 2005; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). They take responsibility for themselves. By this we mean not that they selfishly put themselves first or ignore social obligations, but that they do not blame others or make excuses for their own decisions or behavior—rather they own their decisions and the consequences their choices bring (P. L. Benson et al., 2012; Keyes, 2003; Peterson, 2006). Other indicators reflecting honesty and integrity include telling the truth, keeping promises, giving correct information on applications and tax forms, and calling in sick to school or work only when really sick (Gibbs, Basinger, & Grime, 2003; Kosterman et al., 2005).

Development does not occur in historical vacuums, and much has been written about possible changes in ethics among youth and young adults in American society. For example, a Josephson Institute of Ethics survey found that young adults (ages 18–24) were three times more likely than those over age 40 to believe that lying and cheating is necessary for success (Josephson Institute, 2009), and more likely than older adults to admit to a variety of lying or cheating behaviors, from lying to spouse or significant others, to making unauthorized copies of music or videos. Large majorities of all age groups were found to think that today’s youth lie and cheat more than their counterparts of previous generation, but teens and young adults—the closest to the actual behavior of young people—were significantly more likely to think this.

Certainly, an argument can be made that, as economic inequality has increased in American society, and the competition gets more fierce for “good” jobs for the nation’s college graduates, much less those young adults who do not go to college, young people’s belief that lying and cheating are necessary for success may not be an inaccurate diagnosis of a broader social condition. It is not hard to see that their perceptions of what is needed to “get ahead” or even to make ends meet may bring young adults face-to-face with unsavory choices that lead to placing personal gain above doing what is right. And the explosion of the “wired” life creates other ethical dilemmas forcing young adults into making numerous decisions in young adulthood not faced by earlier generations, from whether to download “pirated” versions of music or videos, to what and how truthfully or fictionally to share about oneself and others in social networking sites. For young adults, these may be areas of evolving ethics, where there is not yet a clear social norm, or there are competing norms, that this generation of adolescents and young adults is figuring out. In other areas of contemporary life, young adults may be developing a broad emerging norm of describing large social issues as ethical. For example, a study of college students found that 45% “unequivocally” identified climate change as a moral or ethical issue demanding both individual and collective action, and another 30% were unsure, thinking it might be (Markowitz, 2012).

Still, accounts of young adult morality, as in Smith et al. (2011), leave the impression that the majority of young adults (18–23 year olds in that study) are moral individualists without a larger vision of ethical obligations to others or to causes. That study was based largely on interviews with just 230 young adults, mostly in college, so it is questionable how much that conclusion can safely be generalized beyond those narrow boundaries. But a study examining two large and familiar databases over the last 40 years (Monitoring the Future, and The American Freshman) also found evidence that young adults today also are less civically oriented (e.g., taking environmental action, making charitable donations) and consider individualistic and extrinsic values such as money and fame more important than connecting with others and contributing to community, the reverse pattern seen in the Baby Boomer generation born 1946–1961 (Twenge, Campbell, & Freeman, 2012). However, a Pew Research Center study at the same time found that relational and contribution goals such as being a good parent, having a successful marriage, and having a job that contributes to society were young adults’ (18–24 year olds) most important goals, far more important than self-gain goals such as fame or making a lot of money (Taylor et al., 2012). The one certain conclusion to draw is that successful young adulthood in this era presents a mix of traditional and new moral issues, dilemmas, and decisions with which young adults must grapple as part of solidifying their authentic personal and social identities.

Healthy family and social relationships

This dimension comprises a young person’s social bonds or connectedness with others in friendships and neighborhood relationships, their ability to share intimacy, and be a loving and effective family member. Success in establishing and maintaining social relations is important for successful development because social relations are among a person’s most fundamental sources of positive functioning and well-being (Berscheid, 2003; Durkheim, 1951; Reis & Gable, 2003; Reitzes, 2003). Feeling lonely, that is feeling socially isolated, is documented to have a multitude of negative consequences (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010). Successful young adults have people they can turn to in times of need; are satisfied with their networks of friends; have close relationships including an adequate number of friends and a high quality of intimate love, romantic, or sexual relationships (Cox & Harter, 2003; Furstenberg & Weiss, 2000; Holmbeck et al., 1995); and frequently interact with parents, partners, and peers (Catalano & Hawkins 1996; Resnick et al., 1997). They are connected with others in classes, organizations, and formal groups where they pursue common interests. The social capital literature suggests that involvement in organized prosocial groups is itself a positive contribution to the social fabric (Hemingway, 1999; Paxton, 1999; Putnam, 2000). Moreover, it is the developmental relationships that people experience in programs—more so than a particular program curriculum—that are considered the “active ingredient” in successful prevention and intervention programs (Li & Julian, 2011). Note that we emphasize the importance of healthy relationships, but do not list marriage itself as a necessary dimension of successful young adult development. For example, especially for contemporary young women, who are becoming young adults in a post-women’s movement era, marriage has been found for some to be important only as it is connected with other young adulthood markers such as financial independence and parenthood. At the same time as they may ascribe subjective importance to marriage, these women simultaneously hold strong commitments to self-development and independence from men (Aronson, 2008).

The Social Development Model (SDM; Catalano & Hawkins, 1996) integrates these perspectives into a comprehensive theory. The model hypothesizes that strong bonds develop between young people and developmentally salient social units (such as the family, partners, peers, work, school, and the community) when these social units provide prosocial opportunities for involvement that help build developmentally relevant competency and skills and consistently reinforce the use of these skills in regular interactions. Strong bonds of attachment and commitment to prosocial units put young adults on a positive developmental trajectory. In contrast, opportunities for antisocial involvement, for example with substance-using or delinquent peers, can also create bonds with these peers, if these interactions are consistently rewarded, but bonds to antisocial others will not put young people on healthy and successful trajectories.

The SDM has been tested in multiple datasets at different stages of development and was found to predict health-related outcomes, including substance use and misuse, depression, violence, school misbehavior, and other problem behaviors (e.g., Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Choi, Harachi, Gillmore, & Catalano, 2005; Hawkins, Kosterman, Catalano, Hill, & Abbott, 2005; Huang, Kosterman, Catalano, Hawkins, & Abbott, 2001; Lonczak et al., 2001; Roosa et al., 2011; Sullivan & Hirschfield, 2011). Empirical studies of the SDM in young adulthood have developed valid and reliable measures of prosocial opportunities (e.g., “I have lots of chances to do things with him/her”), interactions (e.g., “How often do you have a friendly chat with him/her?”), rewards (e.g., “How much warmth and affection do you receive from him/her?”), and bonds (e.g., “How close do you feel to him/her?” and “Do you share your thoughts and feelings with him/her?”) that young adults have with parents, intimate partner, children, friends, co-workers, fellow students, and neighbors (Kosterman et al., 2005; 2014). Loneliness or social isolation can be measured using the 20-question Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1980), but a short 3-item version is also available (“How often do you feel that you lack companionship?,” “How often do you feel left out?,” “How often do you feel isolated from others?;” Hughes et al., 2004) and has been validated among college students (Matthews-Ewald & Zullig, 2013).

A more recent elaboration of tenets in the SDM is the Developmental Relationships framework (Pekel et al., 2015). Developmental relationships are close connections that help young people develop their identities, a sense of agency, and a commitment to community. This is hypothesized to occur through bidirectional interactions that involve expressing care, providing support, challenging growth, expanding possibilities, and sharing power. The framework has been studied so far among parents of young children and adolescents, and adolescents themselves, with one study conducted of young adults in college. Initial results show that stronger developmental relationships are consistently linked with concurrent reports of academic, social-emotional, psychological, and behavioral well-being, with sharing power being a particularly important strategy between parents and children. Among the sample of college students, logistic regression showed that those with adequate or good levels of developmental relationships among friends and professors were twice as likely to have high levels of perseverance (Scales, 2014b). The measures of developmental relationships (20 specific relational actions such as encourage youth, respect them, help them stretch, negotiate with them) have shown good reliability and validity in studies to date (Pekel et al., 2015) and may be useful additions to the aforementioned SDM measures.

Educational attainment

One of the biggest variations in the clusters of different pathways young people take to adulthood is in how involved they are with education or how far they have gone in educational attainment in the young-adult period. The completion of high school and occupational degree and certification requirements are indicators of educational success. They are powerful determinants of later adult occupational and socioeconomic status, as well as health and other personal outcomes in adult life (Balfanz et al., 2012; Heckman & Kautz, 2012; Pallas, 2000). Successful young adults are on a path on which their post-secondary educational involvement is appropriate to the personal and career/work goals they have.

An important consideration when assessing educational attainment is whether young adults have completed a high-school degree or a General Educational Development (GED) certificate. However, a GED does not appear to reflect “on-time” completion of secondary education and does not lead to the same post-educational and economic benefits as the regular high-school diploma. GED recipients were more similar to non-credentialed drop-outs than high-school graduates on other young adult outcomes (Boesel, Alsalam, & Smith, 1998; Cameron & Heckman, 1993).

The effects of college and graduate degree completion on employment and earnings have been well-documented (Balfanz et al., 2012), with those failing to obtain post-secondary degrees far less likely to earn a living that legitimately could be described as “middle class.” A “skills premium” now means that a college graduate earns double what a high school graduate does, rewarding those who excel at abstract tasks that draw on “problem-solving ability, intuition, creativity, and persuasion” (Autor, 2014, p. 845). In a recent policy paper for the Brookings Institution, Levine (2014) states flatly that the “most direct way to improve labor market success for a [youth] is to improve her educational outcomes” (p. 2). Although some research suggests average income-based achievement gaps present at school entry are not widening appreciably during schooling (Reardon, 2013), the barriers to closing the gap remain formidable. Even those low-income students who are high achieving are less likely to take advanced high school courses or go to college than their affluent, high-achieving peers (Bromberg & Theokas, 2014). And poverty, of course, is not equally likely across racial/ethnic groups: Roughly one in four African Americans and Hispanics live in poverty, compared with just one in ten Whites (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2015).

The structural barriers that make it harder, on average, for low-income youth and youth of color to become high school graduates who complete college as young adults, mean that measuring educational attainment solely on the basis of youths’ achievements fails to account for the inability of individual initiative alone to overcome powerful systemic forces that maintain the status quo. Should those lower-income young adults who are dealing with such structural obstacles as best they can, who are trying to attain further education but who might not be able to enroll because they cannot afford it, be described as developmentally unsuccessful young adults because a measure of “success” focuses solely on college degree attainment? We think not. Attainment of post-secondary education needed to pursue personal and work goals is thus an example of a dimension of “success” that comes with a caveat: It leads to success in terms of subsequent earnings, health, and other variables, so it is clearly desirable to achieve. But because of discrimination, racism, socioeconomic factors, macroeconomic trends at the national or international levels, or other structural circumstances, it is often out of the hands of even reasonably agentic young adults to make happen, absent intentional social policies and enhanced social capital resources for those young adults.

Constructive educational and occupational engagement

Successful young adults occupy themselves mostly in productive pursuits, study, work, or raising a family, or some combination of these. Just as industry is important earlier in life, during young adulthood constructive engagement is an important outcome. Whether engaged in school, work, or homemaking, they are investing time in pursuits that provide the platform for future adult achievements (Rowe & Kahn, 1997). Young adults who are relatively uninvolved with productive activities and have made few transitions into young adult roles, sometimes called “slow starters” (Osgood et al., 2005) seem to flounder, which puts them at risk for achieving later success. Although the great majority of young adults are constructively engaged, at least 19% of young adults ages 18–24 are reported to be neither in school nor the military, nor working, a higher percentage than in 2005, with the percentages higher among those with only a high-school education, African Americans, and Hispanics (America’s Young Adults, 2014; Jekielek & Brown, 2005).

Following the SDM, Kosterman et al.’s (2005) study measured productive activity across the salient social units of young adulthood by creating a constructive-engagement index that considers full-time work (35 hours per week or more), part-time work (less than 35 hours per week), full-time homemaking, or school attendance (full-time or part-time) during the past 12 months. Macroeconomic forces or other structural issues such as discrimination can significantly affect young adults’ odds and levels of school attendance and work. For example, among the fallouts from the Great Recession, more than half of 18–24 year olds were unemployed in 2012, the highest rate since data began being gathered in 1948 (Taylor et al., 2012). Given such realities, a measure such as Kosterman et al.’s might be supplemented by also measuring the extent of young adults’ self-directed learning, which would include volunteering as a means of learning a skill that would be subsequently marketable, reading that increases socially-valued knowledge and skills, and training or informal mentoring for skill development and creating social connections that could lead to more formal education or work experience. The core of the developmentally-relevant measurement for this dimension is, as for educational attainment, both the status of being productively engaged, and for those who might not meet the formal criteria elaborated by Kosterman et al. or similar formulations, the effort and initiative being spent on attempting to attain those levels of productive status. The same as for our discussion of educational attainment, it seems both inaccurate and unproductive to describe young adults as developmentally unsuccessful, who might not be working or in school 35 hours a week or more, particularly due to larger social forces making it difficult or impossible, but who are trying with great effort to reach these levels of engagement. Measurement of this dimension thus fruitfully might include, not just data on constructive engagement status, but on the intensity and duration of young adults’ efforts to become more educationally and occupationally engaged.

Civic engagement

Civic engagement is a final suggested dimension of success in adulthood. Successful young adults have begun to “give back” to the community. They work on improving the social, political, or physical welfare of society. This dimension is important because helping others and contributing to society not only adds to the common civic good, but also increases the well-being and positive functioning of the helper (Eisenberg, 2003; Piliavin, 2003; Thoits & Hewitt, 2001; Uggen & Janikula, 1999). Behavioral indicators of civic involvement include volunteering, charitable giving, registering to vote and consistently exercising that right, and other forms of political participation, and environmental action. Successful young adults have learned enough about community and government to have an interest in political affairs and how to influence them. They are connected to formal groups, not simply for the social relationships such connections permit, but for the contribution they can make to the common good. Measures of volunteering and voting have been used in the National Promises Study with parents of young children, and are equally applicable to young adults who do not have children (Scales et al., 2008).

Although the aforementioned represents a reasonable description of an aspirational goal for young adult civic engagement, the reality is more complex. Flanagan and Levine’s (2010) review, for example, suggests that although some forms of civic engagement have gone down among young adults over the last three decades (e.g., union membership, regular attendance at religious services), other forms, such as volunteering, have gone up. They conclude that civic engagement in general seems to have become more episodic than long-term, when comparing today’s young adults with previous young adult cohorts. Overall, voting patterns and other forms of engagement suggest that, on average, levels of civic engagement are not declining, but more likely being delayed, as the transitions to stable work, marriage, and parenthood take longer than in previous generations.