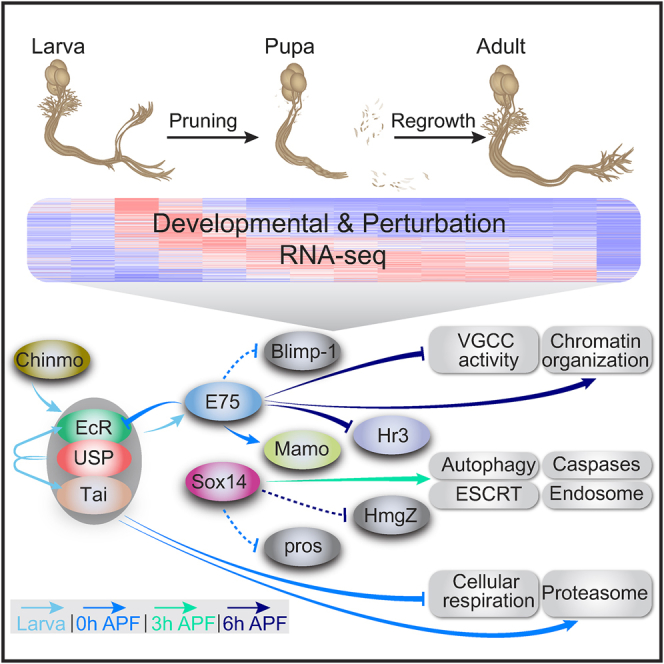

Summary

Developmental neuronal remodeling is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism required for precise wiring of nervous systems. Despite its fundamental role in neurodevelopment and proposed contribution to various neuropsychiatric disorders, the underlying mechanisms are largely unknown. Here, we uncover the fine temporal transcriptional landscape of Drosophila mushroom body γ neurons undergoing stereotypical remodeling. Our data reveal rapid and dramatic changes in the transcriptional landscape during development. Focusing on DNA binding proteins, we identify eleven that are required for remodeling. Furthermore, we sequence developing γ neurons perturbed for three key transcription factors required for pruning. We describe a hierarchical network featuring positive and negative feedback loops. Superimposing the perturbation-seq on the developmental expression atlas highlights a framework of transcriptional modules that together drive remodeling. Overall, this study provides a broad and detailed molecular insight into the complex regulatory dynamics of developmental remodeling and thus offers a pipeline to dissect developmental processes via RNA profiling.

Keywords: neuronal remodeling, RNA-seq, mushroom body, γ-neurons, axon pruning, developmental-seq

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

A developmental expression atlas of MB γ neurons highlights remarkable dynamics

-

•

We uncovered 7 DNA binding proteins (DBPs) that regulate neuronal remodeling

-

•

Sequencing perturbed neurons identified a hierarchical transcription factor network

-

•

Superimposing developmental and perturbation-seq identifies key downstream modules

Developmental processes are often transcriptionally regulated. Alyagor et al. dissected the transcriptional landscape of a distinct neuronal type undergoing stereotypical remodeling in fine-grained temporal resolution. Superimposing this developmental expression atlas on profiles of neurons mutant for key transcription factors revealed a hierarchical regulatory network.

Introduction

Neuronal remodeling is a fundamental process required for the proper wiring of adult nervous system connectivity, both in vertebrates and invertebrates (Yaniv and Schuldiner, 2016, Schuldiner and Yaron, 2015, Luo and O'Leary, 2005). Remodeling often includes a degenerative phase, such as neurite or synapse elimination, as well as a regenerative phase, such as the regrowth of axons and dendrites to form new connections (Schuldiner and Yaron, 2015, Luo and O'Leary, 2005). Defects in remodeling have been hypothesized to underlie various neuropsychiatric diseases, including schizophrenia and autism (Cocchi et al., 2016, Thomas et al., 2016) and, indeed, some molecular similarities have recently been identified (Sekar et al., 2016). Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms that regulate developmental neuronal remodeling might shed light on the etiology of some neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders.

Many Drosophila melanogaster neurons undergo stereotypic remodeling during metamorphosis (Truman, 1990), thus providing a unique and genetically amenable model to dissect the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying this process. The mushroom body (MB) comprises three sequentially born neuronal sub-populations (γ, αʹ/βʹ, and α/β), out of which only the first-born γ neurons undergo remodeling in a spatially and temporally stereotypic manner (Lee and Luo, 1999). After their initial larval growth, MB dendrites and axons undergo pruning during early metamorphosis and subsequently regrow new projections, which form the medial, adult-specific γ lobe (Figure 1A). While significant progress in our understanding of the molecular pathways underlying remodeling has been achieved (Yaniv and Schuldiner, 2016, Yu and Schuldiner, 2014), more pathways await discovery, and many aspects of the known pathways, including their regulators and downstream executers, are still unknown.

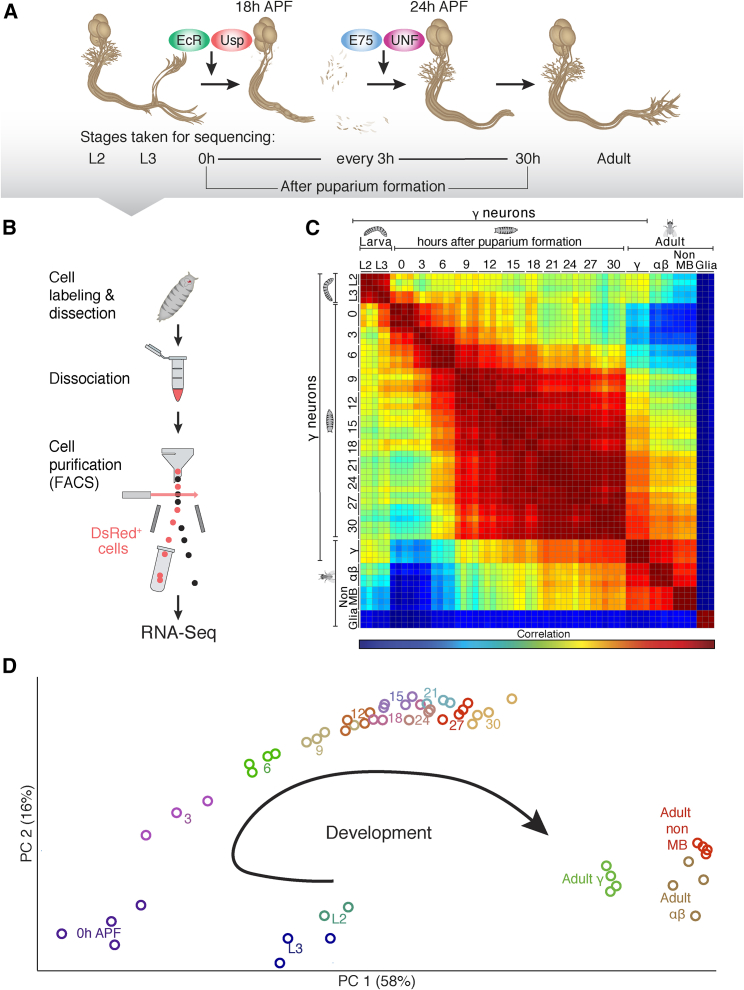

Figure 1.

Expression Profiles of Developing Neurons Reveal a Dynamic Transcriptional Landscape

(A) Schematic representation of MB γ neuron remodeling and its regulation by the nuclear receptor (NR) complexes. The time-points taken for RNA-seq are indicated below. L2 and L3 refer to 2nd and 3rd instar larva, respectively.

(B) Schematic representation of the strategy we employed to isolate γ neurons from fly brains at different developmental stages.

(C) Global correlation matrix of the expression profiles indicated. We sequenced MB γ neurons at 14 developmental stages, as well as adult α/β MB neurons (labeled using NP3061-Gal4), non-MB neurons (labeled by c155-Gal4 combined with MB247-Gal80), and astrocyte-like cells (labeled by alrm-Gal4; marked as Glia).

(D) Principal-component analysis (PCA) of the neural expression profiles shown in (C). Numbers indicate hours after puparium formation (APF).

The nuclear receptor (NR) ecdysone receptor B1 (EcR-B1) has been demonstrated to be cell-autonomously required for the initiation of MB γ neuron pruning, together with its co-receptor Ultraspiricle (usp; Figure 1A; Lee et al., 2000). EcR-B1 has also been shown to be required for dendrite pruning of the sensory dendritic arborization (da) neurons (Kuo et al., 2005, Williams and Truman, 2005), as well as for the remodeling of the olfactory projection neurons (PNs) (Marin et al., 2005) and thoracic ventral (TV) neurons (Schubiger et al., 1998), suggesting that in the fly, it is a master regulator of developmental remodeling across neural systems. We have previously shown that another NR complex, comprising Unfulfilled (UNF; also known as Hr51 or Nr2e3) and Eip75B (also known as E75), regulates developmental axon regrowth of MB γ neurons following pruning (Figure 1A; Rabinovich et al., 2016, Yaniv et al., 2012). Because NRs function as ligand-dependent transcription factors (TFs), these observations together suggest that remodeling of MB neurons is mediated, at least in part, by a developmentally regulated transcriptional program.

Here, we map the developmental expression atlas of MB γ neurons, specifically focusing on the developmental stages that are relevant for neuronal remodeling. We sequenced highly purified populations of isolated MB γ neurons and performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to uncover the expression profiles of neurons undergoing remodeling at unprecedented temporal resolution. Using this developmental expression atlas, combined with genetic analyses, we identified specific DNA binding proteins (DBPs) as regulators of diverse aspects of neuronal remodeling. Furthermore, we have conducted a developmental perturbation-seq by sequencing γ neurons perturbed in three key TFs. Superimposing these sequencing results with the fine developmental expression atlas, we have uncovered a complex hierarchy of DBPs that contains both positive and negative feedback loops that are likely important to time and fine-tune remodeling. Moreover, it allowed us to uncover the key developmental processes and cellular pathways that together culminate in γ neuron remodeling. More generally, our easily accessible temporal-developmental expression atlas can now serve the community in delving deeper into the unknown aspects of MB development, as well as form a platform for comparison with other remodeling paradigms.

Results

Expression Profiles of Developing MB γ Neurons Reveal a Dynamic Transcriptional Landscape

Remodeling of MB γ neurons requires distinct NR complexes at different steps that function as ligand-dependent TFs (Figure 1A), suggesting that a transcriptional network underlies this complex developmental process. In order to uncover the transcriptional dynamics of developing MB γ neurons, we established a multi-step process to isolate distinct populations of cells from intact brains during development, which were then used to generate high-quality sequencing libraries (Figure 1B). We expressed nuclear DsRed (RedStinger) driven by the GMR71G10-Gal4 driver (hereafter referred to as 71G10), which we found to be specifically expressed in MB γ neurons throughout development (Figure S1) but not in non-MB cells within the central nervous system. To this end, we dissected brains, dissociated them into single cells, and isolated DsRed-positive cells using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) (Figures 1B and S2A–S2D). As controls, we isolated adult α/β MB neurons (labeled by the NP3061-Gal4), as well as adult non-MB neurons (labeled by pan neuronal C155-Gal4 additionally expressing the MB-specific repressor, MB247-Gal80, to exclude MB expression) and adult astrocyte-like cells (labeled by Alrm-Gal4). We combined our method with a sensitive and high throughput RNA-seq technology originally developed for single-cell RNA-seq applications (Jaitin et al., 2014; see STAR Methods). MB γ neurons are considered relatively homogenous and because we aimed to extract a deep developmental expression profile at each time point, we decided to sequence pools of cells rather than single isolated neurons. In order to evaluate how many cells are needed and whether using pools of cells indeed results in robust and reproducible data, we conducted RT-PCR experiments (data not shown) with 500–1,000 neurons. Indeed, we obtained robust and reliable data from these experiments, and since 1,000 neurons are easily obtainable from 3–4 dissected brains, we decided to use pools of 1,000 cells as a starting point for all of our RNA-seq experiments. The high correlation between experimental repeats confirmed that this strategy resulted in robust data (Pearson’s correlation, r = 0.94–0.99; Figure 1C). Using these methods, we sequenced RNA from MB γ neurons isolated at 14 developmental time points spanning the key transitions during developmental remodeling (Figure 1A), essentially forming a temporal-developmental expression atlas.

Correlation analysis of the transcriptional state of MB γ neurons across development and compared to other cells (Figure 1C) demonstrates that MB γ neurons undergo a developmentally regulated transcriptional program and highlights several important observations:

(1) As expected, the expression pattern of astrocytes (glia) was dramatically different from neuronal expression patterns. (2) We noticed dramatic changes in the global expression patterns, even when comparing samples only 3 hr apart, mainly during larval to pupal transition. The global correlation between adjacent time points is r = 0.80–0.94 between L3 and 9 hr after puparium formation (APF), while it is r = 0.98–0.99 between 9 hr and 30 hr APF. (3) To our surprise, the transcriptome of adult γ neurons was globally more similar to the transcriptome of other adult (even non-MB) neurons than to that of younger γ neurons. In order to better visualize these transitions, we performed a principal-component analysis (PCA) that clearly demonstrates the higher similarity of adult MB neurons to other adult neurons (Figure 1D). This result emphasizes that the developmental age of a cell plays a more dominant role than its identity in the global RNA expression pattern and also implies that the expression of so-called “cell identity markers” may dramatically change along development. Additionally, the PCA nicely demonstrates the dramatic changes in global expression between larval and early pupal stages (L2 to 9 hr APF) followed by more gradual, though unidirectional, changes in global expression trends between 9 to 30 hr APF.

In conclusion, we devised a protocol to isolate distinct populations of neurons from an intact brain during development and extract their expression profiles using RNA-seq. Our detailed temporal analyses of MB neurons revealed a dramatic transcriptional transition during metamorphosis.

Developmental Expression Atlas Highlights Axon Remodeling Gene Network

Our dataset includes reads from 11,443 distinct genes across cell types and 11,046 in γ neurons, out of which, 5,211 genes exhibited 50 reads or more in at least two γ neuron samples and were therefore considered as “significantly expressed” in γ neurons (Figure 2A). In order to classify developmentally regulated patterns of gene expression, we focused on genes whose expression was statistically dynamic during development (p < 0.01) and in addition demonstrated at least 2-fold differences in expression (STAR Methods and Table S1). Using these criteria, 2,671 of the genes, which account for more than half of the significantly expressed genes, exhibited dynamic expression during development (Figure 2A). Given that the developmental window we used in our experiments starts after embryonic development and major events that control differentiation and wiring of the larval γ neurons, this large proportion of genes undergoing dynamic expression was surprising.

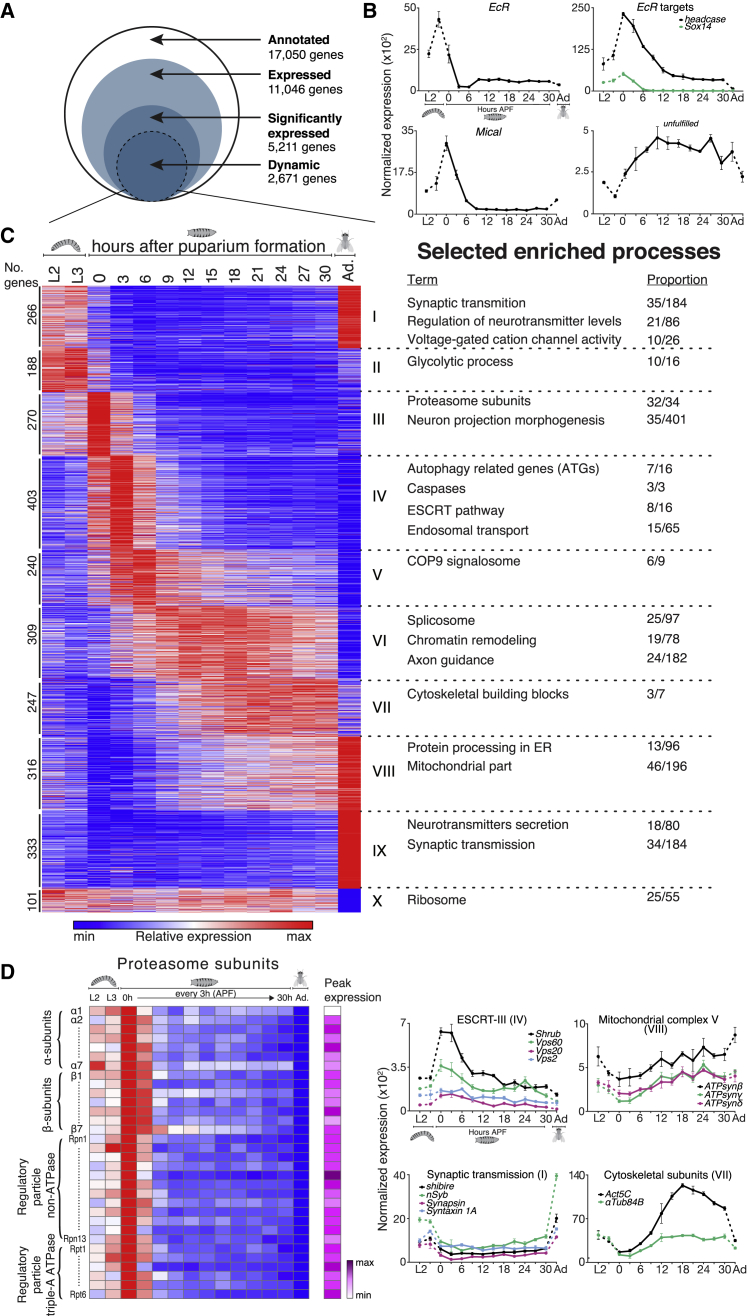

Figure 2.

Developmental Expression Atlas Highlights Axon Remodeling Gene Network

(A) Schematic description of the developmental RNA-seq gating analysis. See details in STAR Methods.

(B) Normalized expression of key remodeling related genes across γ neuron development (x axis, only every second time point is labeled due to space limitations; Ad, Adult). Error bars indicate SEM; units on the y axis are arbitrary.

(C) Heatmap showing k-means clustering (k = 10) of 2,671 dynamically expressed genes across MB γ neuron development. Each horizontal line describes the relative expression of a single gene. Cluster numbers are indicated using Roman numerals. Selected enriched processes within each cluster are described on the right (for a full analysis, see Tables S2 and S3). Enrichment is described here as the proportion of genes within the cluster/total number of genes belonging to the functional group and that are significantly expressed.

(D) Examples of functional groups of genes that are expressed in a similar, and interesting, pattern. Heatmap depicting the relative expression patterns of the proteasome subunits (left). The magenta scale depicts the peak expression of each gene relative to that of other genes in the group. Graphs showing the normalized expression levels of selected genes and gene groups throughout development (x axis, every second time point is labeled due to space limitations; Ad, Adult). Error bars indicate SEM; units on the y axis are arbitrary. Cluster numbers are indicated in parenthesis using Roman numerals.

Among the dynamically expressed genes, we identified many with known neurodevelopmental function. For example, the expression of the key regulator of remodeling in many Drosophila neurons, EcR (Kuo et al., 2005, Marin et al., 2005, Williams and Truman, 2005, Lee et al., 2000), peaks at the late larval stage (Figure 2B), consistent with its peak protein expression at the onset of pupation (Truman et al., 1994). Likewise, headcase (hdc) and Sox box protein 14 (Sox14; Figure 2B), two EcR targets that were found to be required for the dendrite pruning of the da sensory neurons (Loncle and Williams, 2012, Kirilly et al., 2009), both exhibit expression peaks at the onset of the pupal stage, consistently lagging behind the peak expression of EcR. Similarly, the expression of Mical (Figure 2B), a Sox14-regulated gene required for dendrite pruning (Kirilly et al., 2009), also peaks at 0 hr APF. Interestingly, both hdc and Mical were shown not to be required for MB γ axon pruning (Loncle and Williams, 2012, Kirilly et al., 2009). The expression patterns that we reveal here suggest that in MB neurons hdc and Mical are likely targets of EcR and Sox14, respectively, but functional redundancy with unknown genes might obscure their function during MB remodeling. On the other hand, the expression of the regrowth-related gene UNF increases gradually, peaking at 9 hr APF while maintaining high levels during late pupa (Figure 2B). Taken together, these expression profiles validate known expression patterns of key remodeling genes and demonstrate the capability of our dataset to highlight remodeling-related genes due to their dynamic expression pattern.

In order to classify groups of genes with similar expression patterns, we performed k-means clustering (k = 10; STAR Methods), which resulted in groups of genes with distinct developmental expression profile dynamics (Figure 2C). For example, genes in clusters I and II are highly expressed in larva but their expression decreases at the onset of pupation. In each of these clusters, we identified distinct biological processes, as reflected by enrichment analyses of GO, KEGG, and Reactome terms (Figure 2C; Tables S2 and S3). For example, most of the proteasome subunits (94%) exhibit a highly similar expression pattern and clustered together in cluster III, exhibiting a peak expression at the onset of puparium (Figures 2C and 2D; Table S2). This expression is consistent with previous reports (Hoopfer et al., 2008), where the expression of proteasome subunits occurs a few hours before the onset of pruning and fits the known role of the proteasome subunits Mov34 (Rpn8) and Rpn6 in MB axon pruning (Watts et al., 2003). In cluster IV, which exhibits peak expression at 3 hr APF, we found a significant enrichment in endosomal genes, and more specifically a module of genes from the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) (Figures 2C, 2D, and S3A; Table S2), which were shown to be required for axon pruning of MB neurons (Issman-Zecharya and Schuldiner, 2014) as well as da dendrites (Loncle et al., 2015, Zhang et al., 2014). In the same cluster, we found enrichment of genes from two other degenerative pathways—caspases and autophagy (Figure 2C; Table S2). In contrast to the ESCRT complexes, specific perturbations of the autophagy machinery have so far failed to result in remodeling defects (Issman-Zecharya and Schuldiner, 2014 and data not shown). Interestingly, while caspases have been implicated in dendrite remodeling of sensory da neurons (Schoenmann et al., 2010, Kuo et al., 2006, Williams et al., 2006) as well as in nutrient deprivation remodeling of mammalian neurons (Cosker et al., 2013, Schoenmann et al., 2010), evidence for the involvement of the apoptotic machinery in MB γ remodeling is so far lacking (O.S., unpublished data and Awasaki et al., 2006, Watts et al., 2003). The fact that all of these biological processes are upregulated around the same time, in a seemingly coordinated fashion, suggests that they could act redundantly, eliminating the possibility to visualize a phenotype from simple perturbations to these systems. How these pathways together contribute to various aspects of remodeling remains to be discovered.

Another noteworthy example is the expression profile of synaptic transmission genes that are significantly enriched in clusters I and IX (Figures 2C and 2D; Table S2), exhibiting high expression at larval and adult stages. Whether this dynamic expression is a result of an expected general decrease in neuronal activity during metamorphosis or rather embeds important neuron-neuron signaling is an interesting avenue for future studies.

One fundamental aspect of MB remodeling is that the γ neurons shift from a degenerative to a regenerative state within a very short time frame as pruning occurs between 6–18 hr APF and by 24 hr APF the same neurons have begun to undergo regrowth. Recently, we found that nitric oxide (NO) signaling provides a switching mechanism between these states, with high NO required for pruning but low NO levels required for the initiation of regrowth. The drastic change in NO levels is achieved, at least in part, by alternative splicing of short isoforms of the NO synthase gene that function as dominant negatives and inhibit the activity of the full-length isoforms (Rabinovich et al., 2016). Interestingly, we found that the spliceosomal complex genes were significantly enriched in cluster VI (Figures 2C and S3B; Table S2). The expression of genes in this cluster gradual increases in the first few hours APF and includes the regrowth-related gene UNF, as well as genes related to axon guidance, axon development, and microtubule-associated complexes (Tables S2 and S3). Thus, the enrichment in the spliceosome genes in this cluster hints that a shift in splicing might correlate with the developmental switch from pruning to regrowth. Furthermore, major cytoskeletal components such as the main cytoplasmic actin gene, Act5C, as well as the most abundant α and β-tubulin subunits encoding genes, α-Tub84B and β-tub56D, assigned in cluster VII, exhibited a dynamic expression pattern (Figures 2C and 2D; Table S2) that might reflect the switch between the pruning and regrowth.

Finally, we identified a significant enrichment in mitochondrial genes in cluster VIII (Figures 2C and 2D and S3C; Table S2), which contains genes with a specific decreased expression before pruning, followed by increased expression before and during regrowth. This dynamic expression pattern might indicate that mitochondria transcription is a part of the aforementioned cellular switch. Whether this expression transformation is a result of different energy needs or a more instructive mechanism should be further investigated.

Taken together, our high-resolution temporal expression profiling has allowed us to detect the dynamics of gene modules relevant to the different phases of neuronal remodeling. This resource, which can be freely accessed and explored in its entirety (http://www.weizmann.ac.il/mcb/Schuldiner/resources), offers a unique platform to study the development of MB γ neurons and more general timed and stereotypical developmental processes. As such, it highlights specific candidate pathways and genes important during development and suggests possible redundancies and pleiotropies that are otherwise overlooked using conventional genetic tools.

Expression Dynamics of DNA Binding Protein Uncovers New Genes Required for Remodeling

The existence of many dynamic gene modules during γ neuron development suggests that a multi-layered transcriptional network underlies this process. Therefore, we decided to investigate the regulatory factors that govern this network and focused on 177 genes that contain DNA binding domains and are dynamically expressed in our dataset (Table S4; Figure 3A). We chose to focus on the highest expressing DBPs (Figure S4A) within the pruning (II–IV) and regrowth (VI) related clusters (20 genes from each group; we focused on cluster VI for regrowth as it contains the earlier expressed genes which are more likely to function as regulators). In addition, we chose six genes from clusters VII and VIII, which are specifically and significantly (p < 0.01) repressed at the onset of pruning (Figures 3A and S4A; for details, see STAR Methods).

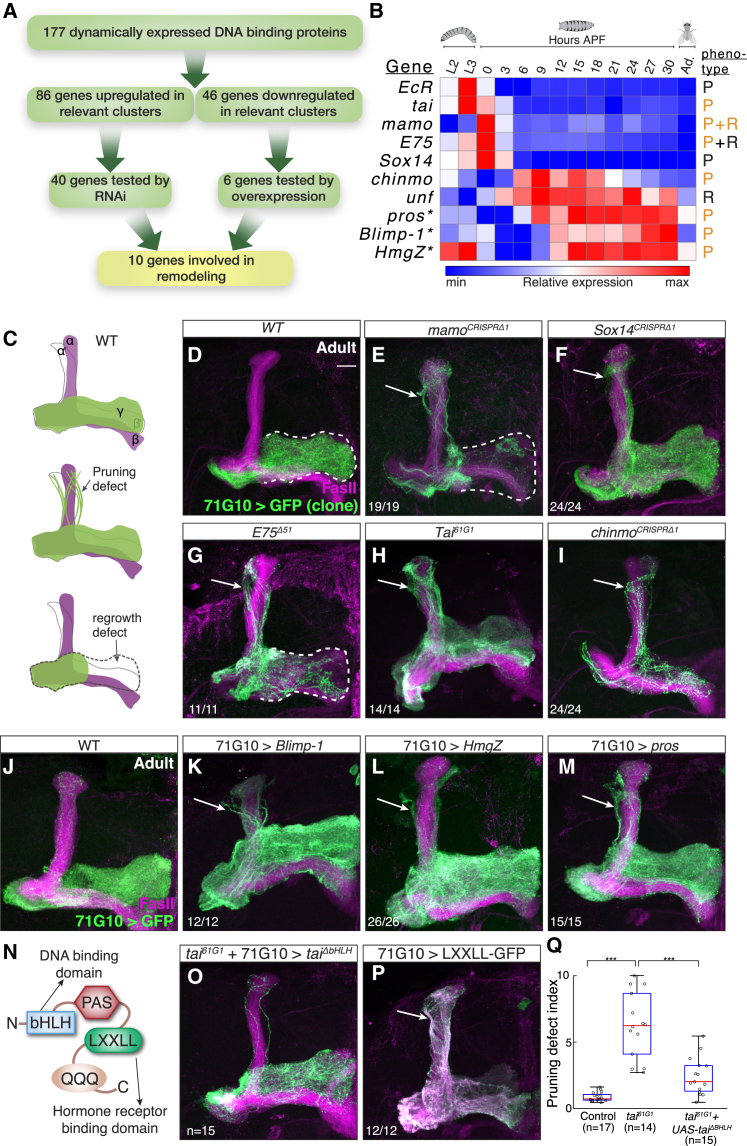

Figure 3.

Dynamic Expression of DNA Binding Proteins Highlight New Genes Required for Remodeling

(A) Scheme of the rationale for the DNA binding protein screen, including the number of genes in each step.

(B) Heatmap showing the relative expression pattern of the 10 positive hits in the DNA binding protein screen. The expression patterns of all 46 genes experimentally tested are shown in Figure S3. Genes were perturbed by RNAi or overexpression (asterisk) experiments. P and R stand for pruning or regrowth phenotypes, respectively. While genes known to be required for remodeling are labeled in black, new findings from this study are labeled in orange.

(C) Schematic representation of WT and defective MBs depicting pruning and regrowth defects. Green represents the γ lobe(s) and magenta represents FasII staining, which in the adult strongly labels α/β neurons, weakly labels γ neurons (not shown for clarity), and does not label αʹ/βʹ neurons.

(D–I) Confocal Z-projections of adult MBs containing WT (D), mamoCRISPRΔ1 (E), Sox14CRISPRΔ1 (F), E75Δ51 (G), Tai61G1 (H), and chinmoCRISPRΔ1 (I) MARCM clones labeled with membrane bound mCD8-GFP (GFP) driven by 71G10-GAL4 (71G10).

(J–M) Confocal Z-projections of adult MBs labeled by 71G10-Gal4 driven mCD8-GFP (GFP) additionally expressing Blimp-1 (K), HmgZ (L), and pros (M).

(N) Schematic diagram of Tai depicting the basic-helix-loop-helix (bHLH) domain required for DNA binding, the LXXLL domain required for binding hormone receptors, the PAS domain, and the poly Q activation domain.

(O) Confocal Z-projections of adult tai61G1 MB MARCM neuroblast clones labeled by 71G10-Gal4 driven mCD8-GFP additionally expressing a tai rescue transgene lacking its bHLH domain (ΔbHLH).

(P) Confocal Z-projection of an adult MB with 71G10-Gal4 driving the expression of mCD8-GFP and as well as the hormone receptor binding domain of Tai fused to GFP.

(Q) Quantification of the pruning severity in (D), (H), and (O). We automatically designated a pruning index to each brain based on image analysis (see STAR Methods). Box centers indicate the median, and the bottom and top edges indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers extend to the most extreme data points not considered outliers (99.3% coverage if the data is normally distributed). ∗∗∗p < 0.001; see Figure S6B for a parallel, blind ranking quantification.

Pruning defects, evident by dorsally projecting γ neurons, are marked by arrows, while a regrowth defect, evident by incomplete innervation of the adult γ lobe, is demarcated by a white dashed line. Green is mCD8-GFP driven by 71G10-Gal4; magenta is FasII staining; scale bar represents 15 μm. The numbers (x/n) on the lower left corners depict the number of times the phenotype was observed out of the total hemispheres examined.

To investigate the potential roles of these 46 DBPs in neuronal remodeling, we expressed RNAi or overexpression transgenes targeting each of the up- or downregulated genes accordingly, driven by the MB γ neuron specific driver 71G10. We found that 10 out of these 46 DBPs were involved in neuronal remodeling (Figure 3B), out of which 6 were not previously described in this process. While adult WT MB γ neurons project only to the adult specific medial γ lobe (Figures 3C and 3J), knocking down the expression of EcR, taiman (tai), maternal gene required for meiosis (mamo), E75, Sox14, and chronologically inappropriate morphogenesis (chinmo) resulted in dorsally projecting γ neurons, indicative of a pruning defect (Figures S4B1–S4H1). In order to validate the RNAi findings, we tested available mutants or generated CRISPR-mediated mutants (Figure S6A) and examined adult brains using the mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) technique (Lee and Luo, 1999; Figures 3D–3I). Furthermore, overexpression of Blimp-1, HMG protein Z (HmgZ), or prospero (pros) similarly resulted in unpruned γ neurons (Figures 3K–3M). Since all of these perturbations exhibit normal axon development at the 3rd instar larval stage (Figures S4B2–S4H2 and S4J1–S4L1), while exhibiting unpruned axons at 18 hr APF (Figures S4B3–S4H3 and S4J2–S4L2), the peak of axon pruning, our findings suggest that they are specifically required for remodeling. We verified the protein expression dynamics of selected DBPs and verified their specific elevation during the onset of remodeling (Figures S5A–S5D). This does not rule out, however, other roles for these genes during the development or function of γ or other neurons—in the case of mamo, for example, it is clearly additionally expressed in non-γ cells (Figure S5C). Remarkably, four out of the six most highly expressed genes in the pruning-oriented clusters were found to regulate pruning (Mamo, E75, Sox14, and EcR; Figure S3A), out of which three are part of the ecdysone signaling pathway.

Additionally, knocking down mamo, E75, and UNF resulted in incomplete growth of the adult γ medial lobe, indicative of a regrowth defect (Figures S4F1 and S4H1–S4I1). mamo MARCM clones indeed exhibit a regrowth defect similar to the RNAi experiments (Figure 3E). Knocking down these genes did not affect initial axon development (Figures S4F2 and S4H2–S4I2).

The TF Sox14 is a known EcR target and has been shown to regulate dendrite pruning of the sensory da neurons (Kirilly et al., 2009). Previous work on Sox14 has shown that, while RNAi expression within MB neurons resulted in aberrant axon pruning at 24 hr APF (Kirilly et al., 2009), pruning occurred normally in Sox14Δ15 mutant clones (O.S., unpublished data). However, our newly generated Sox14CRISPRΔ1 MARCM MB neuroblast clones displayed a clear axon pruning defect (Figure 3F; n = 24/24). Since both of the previously used mutants (Kirilly et al., 2009) contain a small deletion within the first exon, while our mutation is a full deletion of the gene, one potential explanation of this discrepancy is the existence of an alternative start site that might be differentially expressed between the da and MB neurons.

E75 is another well-described target of EcR that we have previously shown to be involved mainly in axon regrowth following pruning (Rabinovich et al., 2016; Figure 3G). While the previously published allele, E75Δ51, also displays a moderate pruning defect (Rabinovich et al., 2016; Figure 3G), the notable high expression of E75 at the onset of pupation compared to later stages suggested a more significant role in the pruning process. Indeed, knocking down E75 using RNAi resulted in a significant pruning defect (Figure S4H1). Since E75Δ51 contains a deletion of only part of the gene and is proposed to perturb some but not all isoforms, one possible explanation is that different isoforms might be differentially required for pruning and regrowth.

tai is an ortholog of the mammalian NR coactivator 3, which is part of the family of steroid receptor coactivators (SRCs). It contains a basic-helix-loop-helix (bHLH) domain that allows it to bind DNA directly, as well as an LXXLL domain that mediates binding to the hormone-bound NR (Figure 3N; Bai et al., 2000). Previous studies have implicated tai in border cell migration in the Drosophila ovary, functioning together with EcR and its co-receptor usp (Jang et al., 2009, Bai et al., 2000). However, the function of tai in other tissues has not been thoroughly examined. Knockdown of tai expression using RNAi resulted in a mild pruning defect (Figure S4D1). However, MB neuroblast MARCM clones homozygous for tai61G1, an established EMS loss-of-function mutant, exhibit a severe defect (Figure 3H; n = 14/14), suggesting that the weak RNAi phenotype might be due to the variable efficiency of the RNAi strategy in neurons. We further confirmed the Tai protein expression pattern, which revealed high expression levels in MB γ neurons at 0 hr APF (data not shown) congruent with EcR-B1 (Lee et al., 2000). Tai can potentially function as an independent TF (thus requiring its bHLH DNA binding domain), or as a coactivator of NRs. To investigate the requirement of the bHLH domain in axon pruning, we performed a rescue experiment by expressing a tai transgene lacking this domain (taiΔbHLH) within a tai61G1 MARCM clone. We found that expression of taiΔbHLH was sufficient to rescue the tai61G1 pruning defect (Figure 3O; quantification in Figures 3Q and S6B; n = 15), suggesting that the DNA binding domain of Tai is dispensable for its function in this context. However, overexpression of Tai’s hormone receptor binding domain (LXXLL) fused to GFP in WT clones was sufficient to cause a severe pruning defect (Figure 3P; n = 12/12), supporting its reported dominant negative function, most likely by sequestering EcR (Jang et al., 2009). In order to further examine the role of tai as a member of the EcR NR complex, we tested whether mutating tai affects the expression levels of known EcR targets such as Sox14 and E75. Indeed, we found that tai61G1 MB neuroblast MARCM clones exhibit significant lower Sox14 protein levels (Figure S6C). Since a good E75 antibody has yet to be generated, we instead examined the antibody staining of Mamo, which we found to be regulated by E75 (Figures S7C and S7L). As expected, Mamo staining was drastically decreased in tai mutant clones (Figure S6D), suggesting that Tai positively regulates the EcR targets and is consistent with it functioning as a coactivator for the EcR/Usp NR complex.

Our data-driven mini-RNAi screen yielded many factors required for pruning but, in contrast, identified fewer DBPs required for regrowth. One possible explanation is that the regulation of developmental regrowth is less complex than that of pruning or that it involves mostly post-transcriptional regulation, such as alternative splicing. Alternatively, the difference might be inherent to the phenotypes since identifying a pruning defect involves visualization of ectopic axons that do not normally exist, and thus even a minor defect is relatively easy to detect. In contrast, assaying for a regrowth defect requires many axons to be defective at the same time, as they project together to the medial lobe and a minor defect in some but not many of the axons might be masked.

Our results demonstrate the power of developmental expression profiling as a tool for finding new regulators of a complex developmental program such as neuronal remodeling. Additionally, our data suggest that the transcriptional regulation of remodeling is much more complex than previously appreciated.

EcR Mediates Larval to Pupal Transition in a Cell-Autonomous Manner

In order to link between the transcriptional regulators and the developmental modules, we compared the expression profiles of WT γ neurons and those perturbed for key TFs required for axon pruning: EcR, Sox14, or E75. To this end, we expressed a dominant negative form of EcR (EcRDN), Sox14 RNAi, or E75 RNAi within γ neurons (see adult phenotypes in Figure 4A) and extracted RNA-seq data at four stages—L3, 0, 6, and 12 hr APF.

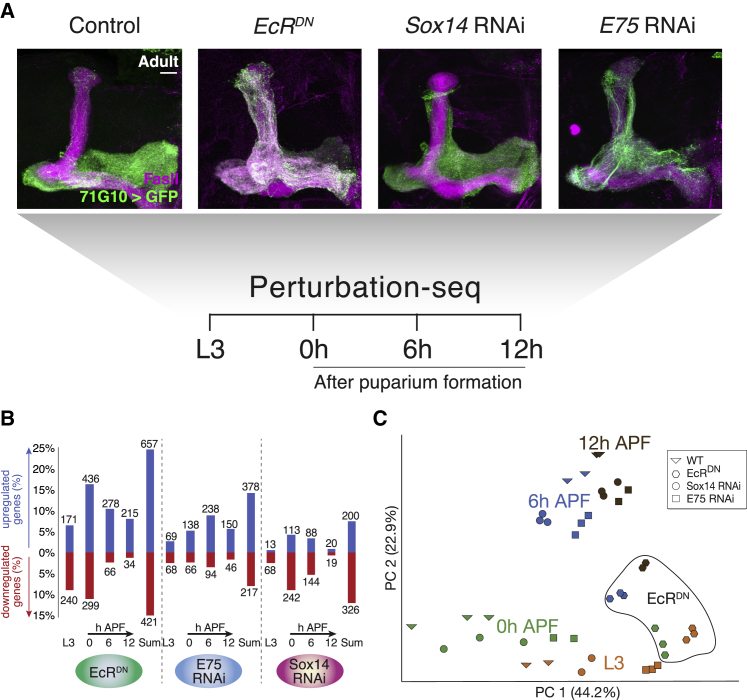

Figure 4.

EcR Mediates Larval to Pupal Transition as Identified by Perturbation Sequencing

(A) Schematic overview of the genotypes and time points taken for perturbation sequencing. The images are confocal Z-projections of adult MB γ neurons labeled with mCD8-GFP (GFP) driven by 71G10-GAL4 (71G10) additionally expressing the indicated transgenes and counterstained with FasII antibody (magenta). Scale bar represents 15 μm.

(B) Quantification showing the number of genes affected by each TF perturbation at each developmental time point as compared to WT.

(C) Principal-component analysis (PCA) of the expression profiles of WT and perturbed MB γ neurons throughout development. Colors demarcate the developmental time, while the shape of each icon represents its genotype.

On a global view, expression of EcRDN resulted in the most dramatic global transcriptome changes—39% of the genes that were dynamically expressed during development (and hence contained in one of our developmental clusters) exhibited at least 2-fold change of expression, in at least one time point compared to their normal expression (Figure 4B; Table S5). E75 and Sox14 perturbations resulted in significant expression changes of 22% and 19% of the genes, respectively (Figure 4B). PCA (Figure 4C) resulted in a primary axis (PC1) representing the transition from larva to pupa and PC2 correlating with the gradual developmental transition. Strikingly, neurons expressing EcRDN showed a high degree of similarity with WT larval neurons regardless of the developmental stage in which they were dissected. In contrast, neurons that expressed Sox14 or E75 RNAi formed distinct clusters with their biological replicates based on the similarity of their global expression but still exhibited a relatively high degree of similarity with their age-matched WT control. Taken together, these results suggest that EcR is not only the master regulator of neuronal remodeling in multiple neuron types but rather dominates the entire transcriptional transition from larva to pupa in MB neurons in a cell-autonomous manner.

Hierarchical TF Networks Regulate Axon Pruning

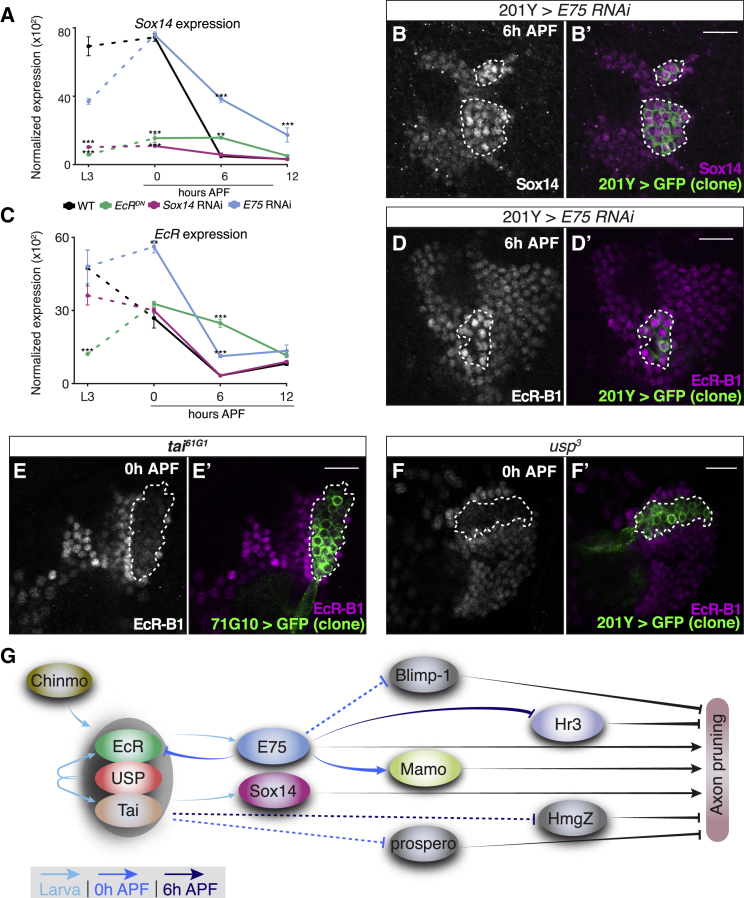

Next, we analyzed the expression profiles of WT and perturbed MB γ neurons to uncover the epistatic interactions between EcR, Sox14, and E75. As expected, RNA levels of E75 as well as RNA and protein levels of Sox14, both of which were shown to be downstream effectors of EcR, were significantly reduced in neurons expressing EcRDN (Figures S7A and S5A and data not shown). However, when we compared the expression levels of Sox14 in WT neurons to those expressing E75 RNAi, we noticed a dramatic increase in Sox14 RNA levels at 6 hr APF (Figure 5A), suggesting that E75 inhibits Sox14 expression at this developmental time point. This is an unexpected finding since we did not observe significant changes in Sox14 RNA or protein levels at L3 or 0 hr APF in E75 RNAi-expressing cells (Figure 5A and data not shown). Based on the known features of this transcriptional network (Kirilly et al., 2009), we therefore speculated that E75 might affect Sox14 expression via feedback inhibition of EcR. Indeed, while EcR expression was not altered by Sox14 RNAi, perturbing E75 resulted in increased EcR expression at 0 hr APF (Figure 5C), suggesting a negative feedback loop. To extend this result from RNA to the protein level, we generated MARCM clones expressing E75 RNAi and observed an increase in both EcR-B1 and Sox14 antibody staining within the clones compared to the neighboring cells (Figures 5B and 5D).

Figure 5.

Hierarchical TF Networks Regulate Axon Pruning

(A and C) Normalized expression of Sox14 (A) or EcR (C) in WT MB γ neurons and in those expressing the indicated transgene (∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Error bars indicate SEM; units on the y axis are arbitrary.

(B and D–F) Confocal single slices of the cell body region of MBs containing neuroblast clones labeled with 201Y-GAL4 (B, D, and F) or 71G10-GAL4 (E) driven mCD8-GFP (green), additionally driving the expression of E75 RNAi (B, n = 5; D, n = 4), or mutant for tai61G1 (E, n = 6) or usp3 (F, n = 5). Brains are stained with anti-Sox14 (B) or anti-EcR-B1 (D–F) (magenta) at the indicated time points. Clones are demarcated by dashed lines. The Sox14 antibody staining was increased by 2.2-fold (p < 0.001) within clones expressing E75 RNAi. Expression levels of EcR exhibited a 2.5-fold increase (p < 0.01) within the clone expressing E75 RNAi and a 2.9-fold (p < 0.001) and 3-fold (p < 0.001) decrease within the usp3 and tai61G1 clones, respectively.

Scale bars represent 15 μm.

(G) Schematic model based on data presented here and in Figure S6, describing the hierarchical regulation of axon pruning by regulatory factors as uncovered in this study. The gray ellipse encompassing EcR, Usp, and Tai represents the NR complex. The temporal dimension is represented by the blue color tones of the arrows. While full lines were validated by antibody expressed experiments, dashed lines indicated regulation interpreted only from the RNA-seq data.

Our transcriptome analysis also revealed that EcRDN expression caused a reduction of EcR RNA levels at L3 (Figure 5C). EcRDN encodes for a truncated NR, lacking its activation domain (ΔC655.W650A; Cherbas et al., 2003) and is therefore not expected to affect the endogenous transcript level. Rather, this result suggests a positive auto-regulatory loop during early development that we decided to further examine. Indeed, usp3 or tai61g1 MARCM clones exhibited a drastic decrease in EcR-B1 protein levels at 0 hr APF (Figures 5E and 5F). Together, these results are indeed consistent with a positive auto-regulatory loop between the function of the EcR/Usp/Tai NR complex and the RNA expression levels of EcR-B1. At 6 hr APF, however, we found increased EcR RNA levels within cells expressing EcRDN (Figure 5C), suggesting the existence of a negative feedback at this pupal stage. The parsimonious interpretation that takes into consideration the entire dataset is that expressing EcRDN results in decreased E75 levels (Figure S7A), which in turn release the suppression of EcR later on. In conclusion, our results describe the dynamic and developmentally regulated expression of an EcR regulatory network. We have uncovered two feedback loops—a positive auto-regulatory loop of the usp-EcR complex and a negative feedback of EcR transcription by E75 (included in the broader model illustrated in Figure 5G).

Finally, we decided to similarly analyze the effect of the three TFs on the DBPs that we identified earlier. Using similar analyses of the RNA-seq expression data, in most cases followed by antibody studies in genetically perturbed conditions (Figures S7A–S7P), we broadened the regulatory-factor hierarchy that orchestrates various aspects of pruning (Figure 5G).

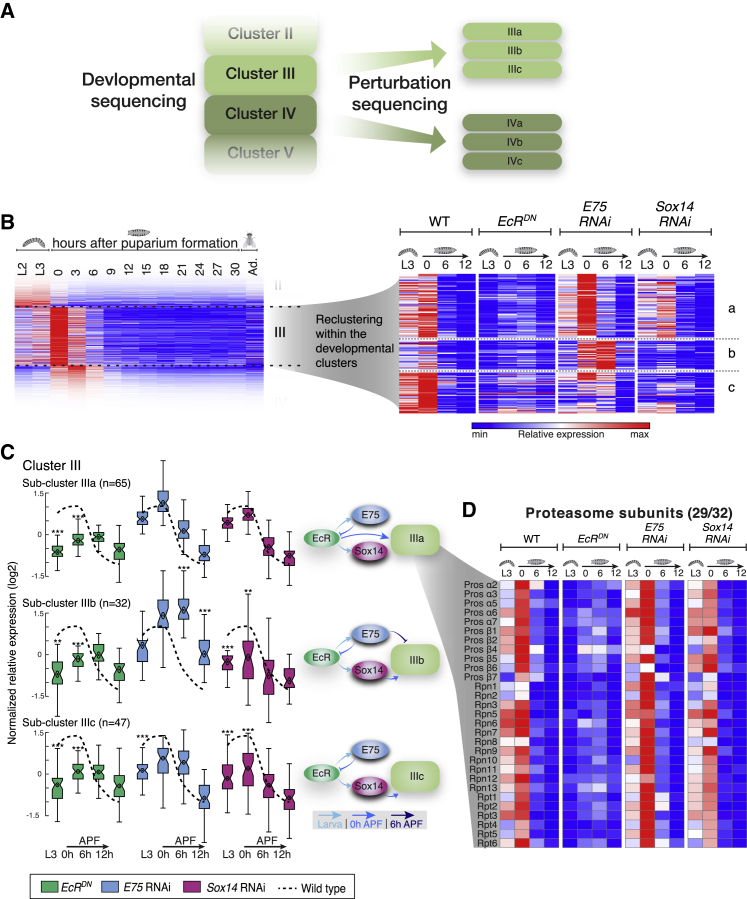

Complex Regulation of TF Circuits Controls Distinct Developmental Programs

Although the TFs are the master coordinators of remodeling, the executioners would be their downstream targets. Thus, we next aimed to better characterize which biological processes are regulated by EcR, Sox14, and E75 that culminate in the execution of neuronal remodeling. This dataset is dimensionally complex as it includes expression profiles of thousands of genes obtained from cells of four different genotypes at four different time points. Therefore, it seems that normal cluster analysis would be difficult to interpret. Instead, we decided to explore the effects of the different TF perturbations on the expression of specific developmental clusters. Our hypothesis was that re-clustering the genes within each developmental cluster, according to their response to a TF perturbation, would highlight specific co-regulated modules (Figure 6A). In other words, we looked for groups of genes within each cluster that are similarly affected by perturbation of EcR, E75, or Sox14. Indeed, the new sub-clusters revealed a unique pattern of temporal regulation by the three key TFs (k = 2–4 sub-clusters for each developmental cluster; Figure 6B; Table S5). The heatmap analysis in Figure 6B is not optimal for two main reasons: first, because it depicts relative expression in contrary to the absolute expression, it may generate a false impression of changes in gene expression. For example, cluster IIIb exhibits a notable increase in expression at 6 hr APF in cells expressing E75 RNAi, resulting in the false impression that its expression does not peak at 0 hr APF in WT cells, as the rest of cluster III. Second, the results from this kind of analysis are not readily quantifiable. Therefore, we looked for a better visualization method that could also allow quantification of the combinatorial effect on each sub-cluster. To this end, we generated boxplots for each sub-cluster representing the effect of each perturbation on the expression of the genes in the sub-cluster (Figures 6C and 7A; Table S5; see details in STAR Methods). In each boxplot, the dashed line represents the average normalized expression trend of the genes within the sub-cluster. In the case of clusters IIIa–c, for example, the dashed line represents the peak expression at 0 hr APF. Note that the dashed line in cluster IIIb still represents a peak at 0 hr APF, unlike the false impression in the heatmap analysis in Figure 6B. The boxplots represent the normalized expression of the genes within the sub-cluster in the appropriate perturbation. For each sub-cluster, we can therefore assign a regulator network, as depicted beside each of the sub-cluster boxplots (Figure 6C). For example, genes within sub-cluster IIIa are mostly inhibited by EcRDN at L3 and 0 hr APF but are unaffected by perturbation of Sox14 and E75, suggesting that sub-cluster IIIa is positively regulated by EcR, either directly or indirectly via an unknown target. In contrast, clusters IIIb and IIc are positively regulated by EcR and Sox14, while cluster IIIb is also negatively regulated at later time points by E75. Delving further into cluster IIIa, we decided to explore whether genes within this cluster were directly regulated by EcR. While the conclusive approach here would be to perform ChIP-seq analyses, these are time consuming and extremely challenging, given the small number of cells in our samples. Therefore, in order to discriminate between direct and indirect regulation of sub-cluster IIIa by EcR, we performed Spearman correlation analysis of the sub-cluster weighted expression and EcR expression. Since we expect a delay between EcR mRNA expression and the mRNA expression of its targets, we performed the analysis between EcR expression and the sub-cluster weighted expression in the next time point available, which was (t) = 6 hr post each time point (for example, EcR expression at 0 hr APF compared to the sub-cluster weighted expression at 6 hr APF; details in STAR Methods). While the Spearman correlation score without delay was rs = 0.05, the correlation score with the delay was rs = 0.88, suggesting a potentially direct induction of sub-cluster IIIa by EcR. This sub-cluster contains 64 genes that include most of the common proteasome subunits (29 genes out of the 32 that exist in cluster III; Figure 6D; and Tables S5 and S6). Taken together, these results suggest that the proteasome subunits as well as the entire IIIa sub-cluster are directly regulated by EcR but not by Sox14 or E75.

Figure 6.

Combining Developmental Clustering with Perturbation Sequencing Is a Powerful Strategy to Reveal Functional Groups of Genes Co-regulated by TF Modules

(A) Schematic representation of the sub-cluster analysis. Each developmental cluster was further divided into sub-clusters with a unique pattern of response to the TF perturbations (by k-means clustering; k = 2–4 for each cluster). The sub-clusters contain only genes whose expression significantly changed in at least one perturbation (see STAR Methods for more information).

(B) Heatmaps of developmental cluster III (left) and the three sub-clusters IIIa–c in the perturbation-seq (right) as an example. Similar analyses were conducted for all developmental clusters (see Table S5).

(C) Boxplot analyses of sub-clusters IIIa–c. The average normalized relative gene expression of the WT samples within each sub-cluster is depicted by the dashed line. Boxplots of the normalized relative gene expression for each one of the perturbations in each time point are shown. Box centers indicate the median, and the bottom and top edges indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers extend to the most extreme data points not considered outliers (99.3% coverage if the data are normally distributed). Statistical significance was determined (∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; see STAR Methods) but shown only in cases where the average fold change >2 and thus more likely to also be biologically significant. The hierarchal regulation of each sub-cluster, as inferred from the data, is presented schematically where the temporal dimension is represented by the shades of blue of the arrows.

(D) Heatmap depicting the relative expression patterns of the proteasome subunits, belonging to cluster IIIa, in the different perturbations. Number (x/y) represent the number of genes from the functional group within the sub-cluster (x) / the number of genes from the functional group within the parent cluster (y).

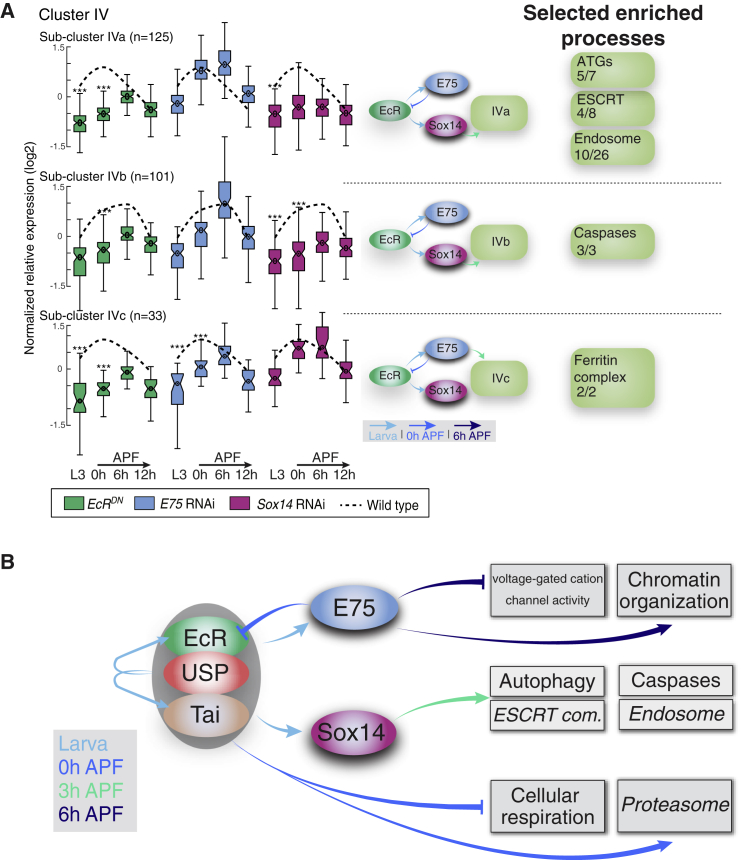

Figure 7.

Toward a Temporal Understanding of the Expression Landscape that Underlies Neuronal Remodeling of MB γ Neurons

(A) Boxplot analyses of sub-clusters IVa–c. The average normalized relative gene expression of the WT samples is depicted by the dashed line. Boxplots of the normalized relative gene expression for each one of the perturbations in each time point are shown. Box centers indicate the median, and the bottom and top edges indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respetively. The whiskers extend to the most extreme data points not considered as outleirs (99.3% coverage if the data is noramlly distributed). Statistical significance was determined (∗∗∗p < 0.001; see STAR Methods) but only shown in cases where the average fold change >2 and thus more likely to also be biologically significant. The hierarchal regulation of each sub-cluster, as inferred from the data, is presented schematically where the temporal dimension is represented by the shades of blue of the arrows. On the right, we label selected groups of genes that are functionally related and enriched within the sub-cluster. Numbers (x/y) represent the number of genes from the functional group within the sub-cluster / the number of genes from the functional group within the parent cluster.

(B) A schematic model based on data presented and analyzed in Figures 6 and 7 and Table S5, describing the temporal regulation or specific transcription modules by the indicated TFs. GO terms with genes that have a known function in remodeling are highlighted in italics. The temporal dimension is represented by the color of the arrows.

Our genome-wide perturbation analyses suggest that sub-clusters IVa and IVb (which contain 125 and 100 genes, respectively; Figure 7A) are both positively regulated by EcR as well as Sox14. Sub-cluster IVa contains most of the autophagy-related genes (ATGs) included in developmental cluster IV and 4 out the 8 ESCRT genes included in this cluster. It is also enriched with genes belonging to the endosome compartment (GO:0005768; Figure 7A; Table S6). Sub-cluster IVb is enriched with genes related to the positive regulation of the apoptotic signaling pathway (GO:2001235) and contains all 3 caspases that are significantly expressed in γ neurons. Our analysis further showed high correlation between the two sub-clusters’ expression pattern and the delayed expression of Sox14 but not of EcR or E75, (rs = 0.84, 0.72, and 0.62 for sub-cluster IVa; and rs = 0.81, 0.45, and 0.46 for sub-cluster IVb, respectively), suggesting that genes in both sub-clusters may be directly regulated by Sox14. Thus, together, clusters IVa and IVb represent two gene modules that are likely directly regulated by Sox14 and are enriched with proteins belonging to several degradative pathways—endosome-related genes, the ESCRT complex, autophagy, and apoptosis. Finally, cluster VIIIa, containing 122 genes, is substantially enriched with genes belonging to three KEGG or GO terms: the citric acid cycle (TCA, map00020), aerobic respiration (GO: 0009060), and mitochondria (GO: 0044429). This sub-cluster seems to be specifically inhibited by EcR, perhaps by direct regulation (Table S5; Spearman correlation rs = −0.76). Whether the downregulation of genes within this cluster is a causal driver of axon pruning requires further investigation.

To conclude, clustering of differentially expressed genes based on their normal developmental expression, followed by sub-clustering of these developmental modules based on their response to specific perturbations to key TFs, enabled us to identify sub-clusters and groups of functionally related genes that are specifically regulated by a set of TF combinations as a function of developmental time. We have focused here on some example clusters, but the full dataset is available and analyzed in Tables S5 and S6 and is directly approachable in its entirety via http://www.weizmann.ac.il/mcb/Schuldiner/resources.

Overall, our perturbation-seq analysis on the basis of the developmental sequencing results in a temporal map of biological processes that are induced or repressed by unique transcriptional circuits during γ neuron development. Some of these functional groups are already known to be required for distinct steps in neuronal remodeling, and in addition, our analysis highlighted new genes and pathways whose coordinated regulation might be required for remodeling and that might not have been easily identifiable using current genetic approaches (Figure 7B). More generally, it provides a broad map of the immense transcriptional effort that must be carried out to enable such a dramatic developmental program as elimination of cellular parts and their subsequent re-creation.

Discussion

Gene Expression Is Highly Dynamic during Development

During the last decade, several studies have conducted wide transcriptional analyses of cell populations or tissues in vivo during development (Ren et al., 2017, Shigeoka et al., 2016, Liu et al., 2015, Molyneaux et al., 2015), but the temporal resolution was normally limited to 3 or 4 time points and included few samples per tissue. A recent study sequenced 9 developmental stages to discover discrete transcriptional phases during microglia development, thus demonstrating the power of higher temporal resolution (Matcovitch-Natan et al., 2016). However, due to the nature of the developmental process studied, the temporal gap between the stages was rather large (days). In the present study, we performed developmental sequencing in an unprecedented temporal resolution that enabled us to fully capture the neuronal remodeling program, which takes place during a very short time frame. As seen by the global correlation analysis, expression patterns are extremely dynamic even in a 3-hr window, especially during early metamorphosis. While studies have previously shown expression dynamics in these timescales of key TFs during development (Truman et al., 1994, Klingler and Gergen, 1993, Biggin and Tjian, 1989), the finding that these rapid changes occur on a global level is remarkable. While this paper was in revision, three papers dissected the early steps of zebrafish embryogenesis, further demonstrating the power of our strategy (Briggs et al., 2018, Farrell et al., 2018, Wagner et al., 2018).

Complex Feedback Loops Regulate the EcR Signaling Pathway

The TF hierarchy that we identified uncovered a multilayered regulatory network that governs pruning. Specifically, we identified positive and negative feedback loops on EcR transcription. Our study also indicates the domination of EcR signaling on the entire transcriptional transition from larva to pupa in MB neurons in a cell-autonomous manner. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that other layers of regulation will support EcR signaling tuning. Boulanger et al. (2011) showed that ftz-f1 and Hr39 function upstream of EcR in MB γ neurons, with Hr39 suggested to act as an inhibitor of EcR. King-Jones and Thummel (2005), however, suggested that Hr39 is a downstream target of EcR. Our expression analyses indicate that the expression of Hr39 in γ neurons peaks at 0 hr APF (cluster III; Figure S4A), which lags after the EcR peak itself. Furthermore, Hr39 expression is dramatically reduced in samples expressing EcR-DN (not shown), consistent with Hr39 being a bona fide downstream target of EcR as previously suggested (King-Jones and Thummel, 2005). A hypothesis that combines these seemingly contradictory findings is that EcR and Hr39 form a negative feedback loop, just like the one we discovered here between EcR and E75. The complex feedback regulation on EcR expression suggests its precise expression levels and temporal regulation are crucial for normal development. The combined existence of positive as well as negative feedback loops to regulate key developmental or homeostatic processes, such as muscle differentiation (Potthoff and Olson, 2007) and the circadian clock (Barkai and Leibler, 2000), suggests that this is a common evolutionary strategy to confer expression robustness in noisy conditions.

Combining Developmental-Seq and Perturbation-Seq Is a Powerful Strategy to Uncover Developmental Programs

Several studies have sequenced normal as well as mutant cells (Dixit et al., 2016, Jaitin et al., 2016, Hoopfer et al., 2008), which led to significant findings regarding the transcriptional changes resulting from these perturbations. In the present study, however, we combine the fine developmental expression atlas with the expression profiles of neurons perturbed in three key TFs at four developmental stages. This resolution not only facilitates identifying the putative direct and indirect targets of these TFs but also highlights the temporal and hierarchical dynamics of their regulation. Each one of these TFs has hundreds to thousands of potential targets. Thus, a normal candidate approach would have been time demanding and inefficient. By integrating the perturbation-seq data into developmental-seq clusters, we identified groups of genes that were developmentally co-regulated by a unique TF combination, which in turn assisted us to construct the chronological regulation of varied transcriptional programs during γ neuron development. In conclusion, this strategy is powerful in identifying the dynamics of important developmental programs using rich expression profile data.

The approach that we have demonstrated here should be useful to dissect other complex developmental programs. The two prerequisites are that the studied cells can be labeled and purified and, in addition, that one or more TFs are either known to regulate the development of the cell type studied or identified within the process. Most obviously, with the temporal-developmental expression atlas that we have built for MB γ neurons, one could focus on developmental axon regrowth and the TF network so far comprising UNF and E75. Additionally, we and others have previously shown that astrocyte-like glia are required for different aspects of MB neuronal remodeling and depend on cell-autonomous expression of EcR (Hakim et al., 2014, Tasdemir-Yilmaz and Freeman, 2014). Finally, this strategy could be useful to study mammalian developmental programs, such as bone or cartilage development where identifiable groups of cells were shown and various TFs demonstrated to be required for the developmental process. For example, chondrocyte development is tightly regulated by a complex transcriptional network including various SOX-family as well as Runx family TFs that execute the transition from immature to hypertrophic chondrocytes (Kozhemyakina et al., 2015). One aspect that should be specifically tailored for each system is the temporal resolution, which is likely to be longer gaps in mammals.

The Detailed Transcriptional Landscape of MB γ Neurons Holds the Promise to Uncover Parallel and Presumably Redundant Pathways

In the context of the neuronal remodeling field, the dramatic and overarching transcriptional dynamics that we have uncovered here is, in our opinion, surprising. Studies in the recent two decades highlighted signaling between glia and neurons via the TGF-β pathway as a key trigger of neuronal EcR signaling, which is required to initiate axon pruning (Yu and Schuldiner, 2014). The role of adhesion and cytoskeletal stability was also known and thus transcriptional dynamics of related genes expected. Nonetheless, in our study, we found that 51% of the genes significantly expressed in MB γ neurons exhibited dynamic expression within the time frame of neuronal remodeling. These global changes suggest that the developmental remodeling might involve a more complex program than we initially anticipated.

The detailed expression profiles that we have extracted from MB γ neurons throughout development provide a unique opportunity to uncover parallel and redundant pathways. The example of hdc and Mical, targets of EcR and Sox14, respectively, is discussed above. Similarly, Spastin was recently shown to be required for branch-specific pruning at the mammalian neuromuscular junction (NMJ) (Brill et al., 2016). Despite its highly relevant expression (peak at 0 hr APF; 3.3-fold increase from L3), we did not observe a pruning defect in spastin mutants (data not shown), suggesting that parallel mechanisms might mask its function. More experiments are needed to uncover the detailed MT dynamics as well as the combined function of different MT regulators during pruning.

Finally, caspases were shown to be required for proper pruning in Drosophila da neurons (Schoenmann et al., 2010, Kuo et al., 2006, Williams et al., 2006) as well as axon elimination of mammalian dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons following trophic deprivation in vitro (Simon et al., 2012, Schoenmann et al., 2010) and pruning of mouse retinocollicular connections in vivo (Simon et al., 2012). Our RNA-seq data highlight a regulatory module, positively regulated by Sox14 at the early pupal stage, which includes three degradative pathways—the apoptotic machinery (mostly caspases), the autophagic pathway, as well as the endocytic machinery (clusters IVa and IVb). We and others have previously demonstrated that the endocytic machinery is required for pruning of MB axons and da dendrites (Loncle et al., 2015, Issman-Zecharya and Schuldiner, 2014, Zhang et al., 2014), but a role of caspases and the autophagic machinery in MB neuron pruning is still lacking (Watts et al., 2003 and data not shown). Our data highlight a potential cross-talk between these degradative pathways, which should be further explored in multiple model systems. Interestingly, the defects in retinocollicular refinement when caspases are inhibited are only partial, suggesting that redundant mechanisms might also be important in mammalian systems.

To conclude, we demonstrate here the power of detailed developmental sequencing combined with a genetically tractable system. We have identified here a complex network of regulatory proteins that control different aspects of neuronal remodeling. The eleven DBPs that are described here, most of which (9/11) have predicted conserved mammalian orthologs, should form a good pool of candidate genes that could also be tested in vertebrates, where the understanding of the transcriptional regulation of remodeling is scarce. The entire dataset could serve as a valuable resource for groups studying MB neurons as well as neurodevelopment in general. In the future, it should be compared to other temporal-developmental expression datasets extracted from other neurons in vertebrates and invertebrates. Most importantly, the strategy to combine detailed developmental sequencing with sequencing of perturbed neurons, which we used here to describe the temporal regulation of specific genetic modules, could be used to dissect other developmental programs across the animal kingdom.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Chicken anti GFP 1:500 | AVES | Cat# GFP-1020; RRID: AB_10000240 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti FasII 1:25 | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) | Cat# 1D4; RRID: AB_528235 |

| Rabbit anti Mamo 1:5000 | This study | Cat# Mamo; RRID: AB_2665566 |

| Mouse anti Sox14 1:200 | Kirilly et al. (2009) | Cat# Sox14; RRID: AB_2568322 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti EcR-B1 1:25 | DSHB | Cat# AD4.4; RRID: AB_2154902 |

| Rabbit anti Tai 1:500 | Bai et al. (2000) | |

| Goat anti chicken FITC 1:300 | Invitrogen | Cat# A16055; RRID: AB_2534728 |

| Goat anti mouse Alexa fluor 647 1:300 | Invitrogen | Cat# A32728; RRID: AB_2633277 |

| Goat anti rabbit Alexa fluor 647 1:300 | Invitrogen | Cat# A32733; RRID: AB_2633282 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| DH5ɑ | N/A | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Cell Dissociation Solution | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# C1544 |

| Collagenase/dispase mix | Roche | Cat# 10269638001 |

| Peptides used for anti-Mamo antibody generation: REPEREPDRLRP HQRQVMDDRLEQDVDE |

This study | N/A |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Pico pure RNA isolation kit | Life Technologies | Cat# KIT0204 |

| Gibson assembly | NEB | Cat# E5510S |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Raw data files for Developmental seq and Perturbation seq | NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus | GEO: GSE101946 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| w1118; UAS-RedStinger/CyO | BDSC | BDSC: 8546 |

| w1118; GMR71G10-GAL4 (in attP2) | BDSC | BDSC: 39604 |

| y,w; GMR71G10-GAL4 (in attP40) | This study | N/A |

| w∗; NP3061-GAL4 | DGRC | DGRC: 104360 |

| C155-GAL4 | BDSC | BDSC: 458 |

| w1118;201Y-GAL4 | BDSC | BDSC: 4440 |

| w∗; alrm-GAL4/ CyO; Dr1/TM3, Sb1 | BDSC | BDSC: 67031 |

| y1, w67c23; mb247-GAL80 | BDSC | BDSC: 64306 |

| y,w,TubP-Gal80, hsflp,19A; UAS-CD8:GFP,201Y-Gal4/CyO; | This study based on BDSC lines | N/A |

| hsflp122, 10xUAS-IVS-CD8:GFP; TubP-Gal80,40A/Cyo;GMR71G10-Gal4/Tm6,Tb | This study based on BDSC lines | N/A |

| hsflp122, 10xUAS-IVS-CD8:GFP;Tub-Gal80,G13/Cyo;GMR71G10-Gal4/Tm6,Tb | This study based on BDSC lines | N/A |

| y,w, hsflp122, 10xUAS-IVS-CD8:GFP;GMR71G10-Gal4/Cyo; TubP-Gal80,2A/TM6,Tb | This study based on BDSC lines | N/A |

| hsflp122,10xUAS-IVS-CD8:GFP;201Y-Gal4,UAS-CD8:GFP/CyO; TubP-Gal80,2A,82B, TubP-Gal80/TM6,Tb | This study based on BDSC lines | N/A |

| w∗; 10XUAS-IVS-mCD8::GFP (in attP2) | BDSC | BDSC: 32185 |

| w∗; 10XUAS-IVS-mCD8::GFP (in attP40) | BDSC | BDSC: 32186 |

| usp3, w∗, 19A/FM7c | BDSC | BDSC: 64295 |

| y,w; 40A,G13, Sox14CRISPRΔ1/Cyo | This study | N/A |

| y,w; 40A,G13, chinmoCRISPRΔ1/Cyo | This study | N/A |

| y,w,mamoindel1,19A/FM7 | This study | N/A |

| E75Δ51,2A/Cyo | Based on BDSC line | BDSC: 23652 |

| dpyov1,tai[61G1],40A/CyO | BDSC | BDSC: 6379 |

| y,w; 40A,G13, Sox14Δ15/Cyo | Gift from Kirilly et al. (2009) | N/A |

| y1,sc∗,v1; UAS-mamo RNAiTRiP.HMS02823 (in attP40) | BDSC | BDSC: 44103 |

| y1,v1;UAS- RNAiTRiP.HMJ22371 (in attp40) | BDSC | BDSC: 58286 |

| y1,sc∗,v1; UAS-tai RNAiTRiP.HMS00673 (in attP2) | BDSC | BDSC: 32885 |

| y,w;UAS-E75miRNA (in attp16)/CyO | Gift from Lin et al. (2009) | N/A |

| y1,sc∗,v1; UAS-Sox14 RNAiTRiP.HMS00103 (in attP2) | BDSC | BDSC: 34794 |

| y1,sc∗,v1; UAS-chinmo RNAiTRiP.HMS00036 (in attP2)/TM3 | BDSC | BDSC: 33638 |

| y1,sc∗,v1; UAS-unf RNAiTRiP.HMS01951 (in attP2) | BDSC | BDSC: 39032 |

| UAS-Blimp-1 | Gift from Öztürk-Çolak et al. (2016) | N/A |

| UAS-HmgZ-3xHA (in attp86Fb) | FlyORF | FlyORF: F001885 |

| UAS-pros.L,w∗ | BSDC | BDSC: 32244 |

| UAS-Hr3-3xHA (in attp86Fb) | FlyORF | FlyORF: F000034 |

| W1118; UAS-EcR.B1DN(ΔC655.W650A) | BDSC | BDSC: 6872 |

| w∗; snaSco/CyO; UAS-taiΔBHLH | BDSC | BDSC: 28273 |

| w∗; snaSco/CyO; UAS- tainls.LXXLL-GFP | BDSC | BDSC: 28272 |

| Lines for the screen were obtained from the TRiP collection (BDSC) and FlyORF. For genes without available TRiP collection line in BDSC, alternative RNAi lines were obtained from the GD and KK RNAi collection (VDRC). This Key Resource Table includes only those lines for which images were included in the manuscript. | N/A | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| gRNAs specific sequence for Sox14 deletion: GATGGCGTCCGCCTCCACGA ACACAGTGGACACCAGAACT |

This study | N/A |

| gRNAs specific sequence for chinmo deletion: GTAGCATCACTGCTGGCACCA GCTTGGTCGTAGGTGGTCTC |

This study | N/A |

| gRNAs specific sequence for mamo deletion: GCAGTGAGCACTACTGCTTG CTCGGCTTGTTCCTCGTACT |

This study | N/A |

| Primers for Sox14 deletion check: F’ AAGCCACAGAGAATCGGAGC R’ TTATCGTGTGCGGCGTAGTT |

This study | N/A |

| Primers for chinmo deletion check: F’ TTCTCGTTGCAGCATTTGGC R’ GCCTGCAAAAAGTTGGTGGT |

This study | N/A |

| Primers for mamo deletion check: F’ TTCCATACGCTCGCTCTTCG R’ AGACTTACCGACTCGTGGGA |

This study | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pCFD4 | Port et al. (2014) | N/A |

| pCFD5 | Port and Bullock (2016) | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| MATLAB R2016a software | MathWorks | N/A |

| HISAT v.0.1.5 | Kim et al. (2015) | https://github.com/infphilo/hisat |

| DEseq2 | Love et al. (2014) | N.A |

| Gene-e v.3.0.215 | Broad Institute, Inc. | https://software.broadinstitute.org/GENE-E/ |

| HOMER software | Heinz et al. (2010) | N/A |

| FIJI | Image J | https://imagej.net/Fiji/Downloads |

| FlowJo v10 | FlowJo, LLC | N/A |

| Other | ||

| Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencer | Illumina | N/A |

| BD FACSAria Fusion flow cytometer | BD Bioscience | N/A |

| Zeiss LSM 710 and 800 confocal microscope | Zeiss | N/A |

| 40x 1.3 NA oil immersion lens | Zeiss | N/A |

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Oren Schuldiner (oren.schuldiner@weizmann.ac.il).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Flies

All fly strains were reared under standard laboratory conditions at 25°C on molasses containing food. Males and females were chosen at random. Developmental stage is referred to in the relevant places while adult refers to 3-5 days post eclosion.

For a detailed list of the stocks and their source, see Key Resource Table.

Sox14Δ15 was generated and kindly provided by Dr. Fengwei Yu (Kirilly et al., 2009). UAS-Blimp-1 was generated and kindly provided by Dr. Jordi Casanova (Öztürk-Çolak et al., 2016). UAS-E75miRNA was generated and kindly provided by Dr. Tzumin Lee (Lin et al., 2009). UAS-HmgZ.ORF.3xHA, UAS-Hr3.ORF.3xHA, UAS-Mef2.ORF.3xHA, UAS-ab.ORF.3xHA and UAS-Pep.ORF.3xHA was were obtained from FlyORF (University of Zurich in Switzerland; Bischof et al., 2013). RNAi lines were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC) or from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC), USA. NP3061-GAL4 obtained from Kyoto Drosophila Genetic Resource Center (DGRC). All other lines were also obtained from the BDSC.

R71G10 on chromosome 2 was generated by amplifying the sequences, as determined in the FlyLight database, cloned into pBPGUw using the Gateway system and injected into attP40 landing site using ΦC31 intergation (BestGene).

Genotypes

hsFLP is y,w,hsFLP122; GFP is GFP; 19A, G13, 40A, 2A and 82B are FRTs on X, 2R, 2L, 3L and 3R respectively; 71G10 is R71G10-GAL4; 201Y is 201y-GAL4; G80 is TubsP-Gal80. Males and females were used interchangeably but only the female genotype is mentioned.

Figure 1 and 2

y,w/+; UAS-RedStinger/+;71G10/+

y,w/w; UAS-RedStinger/+;NP3061-GAL4/+

y,w/C155-GAL4; UAS-RedStinger/MB247-GAL80

UAS-RedStinger/ CyO; alrm-Gal4, GFP, UAS-Dcr2/TM6,tb

Figure 3

(D) hsFLP, GFP / y,w; G80,40A/40A; 71G10/+

(E) y,w,G80,hsFLP,19A/ y,w,mamo CRISPRΔ1,19A; GFP,201Y/+

(F) hsFLP,GFP/ y,w; G80,G13/ 40A, G13, Sox14CRISPRΔ1; 71G10/+

(G) hsFLP,GFP/ y,w; 71G10/+; G80,2A/ E75Δ51, 2A

(H) hsFLP,GFP /+; G80, 40A/tai61G1, 40A; 71G10/+

(I) hsFLP,GFP / y,w; G80,40A/ chinmoCRISPRΔ1, 40A, G13; 71G10/+

(J) y,w;GFP /+;71G10/+

(K) y,w/+;GFP /UAS-Blimp-1; 71G10/+;

(L) y,w/+;GFP /+; 71G10/ UAS-HmgZ.ORF.3xHA;

(M) y,w/UAS-pros.L, w; GFP /+;71G10/+;

(O) hsFLP, GFP /+; G80, 40A/tai61G1, 40A; 71G10/UAS-taiΔBHLH

(P) y,w; GFP /+; 71G10/UAS-tainls.LXXLL-GFP

Figure 4

(A) Control: y,w; GFP /+;71G10/+.

y,w; UAS-RedStinger/+;71G10/+.

EcRDN: y,w; GFP / UAS-EcRDN(ΔC655.W650A); 71G10/+

y,w; UAS-RedStinger/ UAS-EcRDN(ΔC655.W650A); 71G10/+

Sox14-RNAi: y,w/y,sc,v; GFP /+;71G10/UAS-Sox14 RNAiTRiP.HMS00103

y,w/y,sc,v; UAS-RedStinger /+; 71G10/UAS-Sox14-RNAiTRiP.HMS00103

E75-RNAi: y,w/y,w; GFP / UAS-E75-RNAimiRNA; 71G10/+

y,w/y,w; UAS-RedStinger / UAS-E75-RNAimiRNA; 71G10/+

Figure 5

(B,D) hsFLP / y,w; 201Y,GFP/ UAS-E75-RNAimiRNA; G80,2A/ 2A, 82B

(E) hsFLP, GFP /+; G80,40A/tai61G1, 40A; 71G10/+

(F) hsFLP, G80, 19A/ usp3, w∗, 19A; GFP, 201Y /+;

Figure S1

y,w; GFP /+; 71G10 /+

Figure S2

(A,B) y,w/+; UAS-RedStinger/ GFP; 71G10 /+

(C,D) y,w/+; UAS-RedStinger/+;71G10/+

Figure S4

(A) Lines for the screen were obtained from the TRiP collection (BDSC) and FlyORF and other sources as indicated in Table S7. For genes without available TRiP collection line in BDSC, alternative RNAi lines were obtained from the GD and KK RNAi collection (VDRC). The Key Resource Table includes those lines for which images were included in the manuscript.

(B1-B3) y,w; GFP /+; 71G10 /+

(C1-C3) y,w/+; GFP /UAS-EcR-RNAiTRiP.HMJ22371; 71G10 /+

(D1) y,w/y,sc,v; GFP /+; 71G10 /UAS-tai-RNAiTRiP.HMS00673

(D2-D3) hsFLP, GFP /+; G80,40A/tai61G1, 40A; 71G10/+

(E1) y,w/y,sc,v; GFP /+; 71G10 /UAS-Sox14-RNAiTRiP.HMS00103

(E2-E3) hsFLP,GFP/ y,w; G80,G13/ 40A, G13, Sox14CRISPRΔ1; 71G10/+

(F1) y,w/y,sc,v; GFP / UAS-mamo-RNAiTRiP.HMS02823; 71G10 /+

(F2-F3) y,w,G80,hsFLP,19A/ y,w,mamoCRISPRΔ1,19A; GFP,201Y/+

(G1) y,w/y,sc,v; GFP /+; 71G10 /UAS-chinmo-RNAiTRiP.HMS00036 (reared on 29°C)

(G2-G3) hsFLP,GFP / y,w; G80,40A/ chinmoCRISPRΔ1, 40A, G13; 71G10/+

(H1-H3) y,w; 201Y, GFP /UAS-E75-RNAimiRNA

(I1-I2) y,w/y,sc,v; GFP /+; 71G10 /UAS-unf-RNAiTRiP.HMS01951

(J1-J2) y,w/UAS-pros.L, w; GFP /+;71G10/+;

(K1-K2) y,w/+; GFP /UAS-Blimp-1; 71G10/+;

(L1-L2) y,w/+; GFP /+;71G10/ UAS-HmgZ.ORF.3xHA;

Figure S5

(A-D) y,w; GFP;71G10;

Figure S6

(C-D) hsFLP, GFP /+; G80,40A/tai61G1, 40A; 71G10/+

Figure S7

(I,M) hsFLP,GFP; 71G10/ UAS-EcRDN(ΔC655.W650A); G80,2A/ 2A

(J,L) y,w, hsFLP / y,w; 201Y, GFP /UAS-E75-RNAimiRNA; G80,2A/ 2A, 82B

(K,N) hsFLP,GFP/ y,w; G80,G13/ 40A, G13, Sox14CRISPRΔ1; 71G10/+

(O) y,w/+; GFP /+;71G10/ UAS-Hr3.ORF.3xHA;

(P) hsFLP,GFP / y,w; G80,40A/ chinmoCRISPRΔ1, 40A, G13; 71G10/+

Method Details

Cell Dissociation and Sorting

Brains were dissected in a cold Ringer’s solution, incubated with collagenase/dispase mix at 29°C (Roche, 15 minutes for larval and pupal brains and 30 minutes for adult brains), washed in dissociation solution (Sigma-Aldrich), mechanically dissociated into single cells and transferred via 35um mesh (Falcon) to eliminate clusters and debris. 1000 DsRed+ positive cells were sorted using a 100μm nozzle and low pressure in BD FACSAria Fusion (BD Bioscience) cell sorted directly into 100μl Pico-Pure RNA isolation kit extraction buffer (Life Technologies) followed by RNA extraction using the kit or stored in -80 for later use. To minimize the effect of an injury response, the samples were kept on ice for the entire procedure from dissection up to the RNA extraction except from the dissociation enzyme incubation.

RNA Amplification and Library Preparation

mRNA was captured using 12 ml of Dynabeads oligo(dT) (Life Technologies), which were washed from unbound total RNA according to the protocol. mRNA was eluted from beads at 85°C with 10 ml of 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5). We used a derivation of MARS-seq as described (Jaitin et al., 2014), to produce expression libraries with a minimum of three replicates per population. In brief, mRNA was barcoded, converted into cDNA and linearly amplified by T7 in vitro transcription. The resulting RNA was fragmented and converted into an Illumina sequencing-ready library through ligation, RT, and PCR. Prior to sequencing, libraries were evaluated by Qubit fluorometer and TapeStation (Agilent).

Analysis of RNA-Seq Data

The samples were sequenced using Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencer, at a sequencing depth of an average of 3.5 and 5 million reads per sample for the developmental-seq and perturbations-seq, respectively. We aligned the RNA-seq reads to Drosophila melanogaster reference genome (DM6, UCSC) using Hisat v0.1.5 with “--sensitive -local” parameters (Kim et al., 2015). Gene annotation were taken from FlyBase.org (Dmel R6.01/Fb_2014_04). Duplicate reads were filtered if they aligned to the same base and had identical unique molecular identifiers (UMI). Expression levels were counted using HOMER software (http://homer.salk.edu) (Heinz et al., 2010). 11,443 genes had at least one read (11,046 in γ neuron samples). For general analyses, we considered genes with reads over the noise threshold (20 reads) in at least two sample resulting in 7,816 genes expressed above this threshold. Significant expression in the γ neurons considered for genes with reads over a second noise threshold (50 reads) in at least two γ neuron samples resulting in 5,211 genes above this threshold. For normalization and statistics, we performed DEseq2 algorithm (Love et al., 2014) on our samples on R platform, which took into account batch effects. All p values presented for RNA-seq data are adjusted p values.

Clusters and Sub-Clusters Generation and Analysis

Our developmental clusters contain 2,671 genes with 50 reads or more in at least two γ neuron samples, a >2-fold and significant (p<0.01) change between any two coupled developmental stages or between - L3/6h APF, L3/18h APF, L3/Adults, 6h APF/18h APF, 6h APF/Adults. We performed k-means analysis on the mean expression of the replicates in each time point using correlation distance measure (k=10, MATLAB R2016a).

For the perturbation sequencing we compared the expression of control and perturbed samples, for each developmental stage. Only changes that were statistically significant (p<0.01) were considered. To describe the effect of the perturbation compared to the mean expression, we first calculated the normalized expression of each sample in the following manner: the expression value (mean of replicates) plus 20 (a minimal value, determined by our thresholding - to reduce low level expression fluctuation) was log2 calculated. The average log2 expression (of the specific gene in the entire perturbation dataset) was then subtracted from these values to give rise to a normalized value that describes its fold change (log2) expression compared to the average across all conditions.

We then performed k-means analysis for each developmental cluster independently using correlation distance measure (k=2-4, MATLAB R2016a). Sub-clusters that contain less than 30 genes were excluded.

Sub-clusters significance was calculated for the normalized expression using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test (MATLAB R2016a ranksum function) with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Significance only shown in Figures 6 and 7 and Table S5 in cases where the average fold change >2.

DNA Binding Protein Screen

Using a database of putative DNA binding proteins (DBP) available in FlyTF.org, we found that our dataset of developmental dynamically expressed genes includes 177 DBPs. For neuronal pruning (clusters II-IV) and regrowth (cluster VI), we chose the 20 genes with the highest expression in the γ neurons for each. From Clusters VII-VIII we focused on the 10 genes with the highest expression and chose only those with significant decrease (p<0.01) in expression between third instar larva (L3) and 0h or 6h APF (6 genes).

Gene Enrichment Analysis

Gene enrichment analysis was done using FlyMine (http://www.flymine.org/) and Gene Ontology Consortium (http://www.geneontology.org/).

Clone Generation

Mushroom body MARCM clones were generated as described previously (Lee et al., 2000). Briefly, vials with newly hatched larva were heat shocked 24h after egg laying for 1 hour in 37 degrees Celsius and dissected at the relevant developmental time point.

Immunohistochemistry