Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a debilitating neurological disorder of the central nervous system (CNS), characterized by activation and infiltration of leukocytes and dendritic cells into the CNS. In the initial phase of MS and its animal model, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), peripheral macrophages infiltrate into the CNS, where, together with residential microglia, they participate in the induction and development of disease. During the early phase, microglia/macrophages are immediately activated to become classically activated macrophages (M1 cells), release pro-inflammatory cytokines and damage CNS tissue. During the later phase, microglia/macrophages in the inflamed CNS are less activated, present as alternatively activated macrophage phenotype (M2 cells), releasing anti-inflammatory cytokines, accompanied by inflammation resolution and tissue repair. The balance between activation and polarization of M1 cells and M2 cells in the CNS is important for disease progression. Pro-inflammatory IFN-[H9253] and IL-12 drive M1 cell polarization, while IL-4 and IL-13 drive M2 cell polarization. Given that polarized macrophages are reversible in a well-defined cytokine environment, macrophage phenotypes in the CNS can be modulated by molecular intervention. This review summarizes the detrimental and beneficial roles of microglia and macrophages in the CNS, with an emphasis on the role of M2 cells in EAE and MS patients.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Experimental autoimmune, Encephalomyelitis, Macrophages, Cytokines

1. Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a debilitating T-cell mediated autoimmune disease of the central nervous system (CNS), manifested clinically as weakness and progressive paralysis [1]. While the etiology of MS is still not well clarified, a combination of several factors are thought to be involved, including genetics, environment, and viral infection, with environment likely playing a more dominant role than genetics [2–4]. Studies from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model of MS, have revealed that autoreactive T cells against myelin proteins play a role in disease development. The infiltrating Th1 and Th17 cells in the CNS release a large amount of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ, IL-17, IL-12, IL-23, and nitric oxide (NO), inducing demyelination and neuron death in the inflamed CNS [5–9]. Anti-inflammatory Th2 and regulatory T cells (Treg), which develop in the later phase, play an important role in controlling inflammation, and damping Th1 cell activity and pro-inflammatory cytokine release; adoptive transfer of Treg has been shown to be efficient in EAE suppression [10].

Recent studies have revealed that microglia/macrophages actively participate in the pathogenesis of EAE progression [11,12]. As the first line of cells, activated microglia/macrophages are more potent phagocytes than resting macrophages in the clearance of cell debris and inhibitory substances in the inflamed CNS. Although beneficial to remyelination, their production of pro-inflammatory cytokines is detrimental to CNS tissue integrity during the induction phase. There are difficulties in differentiating CNS resident microglia from peripheral macrophages in EAE, because they share the same F4/80+/CD11b+ phenotype. However under early stage of inflammatory condition, resident microglia cells express low levels of activation markers CD45, CCR1, CCR5, but high TGF-β; while peripheral infiltrating macrophages express high CD45, CCR1, CCR2, CCR5, but low TGF-β, that might be used as markers for identification of CNS resident microglia cells and peripheral macrophages. Contaminating infiltrating lymphocytes, astroglial/oligodendroglial cells are identified as CD3+CD11b CD45(high) and CD11b CD45−, respectively, can be easily distinguished from microglia cells and macrophages [13–18]. Because they are conditioned in the same way during neuroinflammation in vivo, the function of activated microglia and macrophages overlaps. The review summarizes the detrimental and beneficial roles of microglia/macrophages, and discusses the importance of balance among their subpopulations in EAE development.

2. Microglia in EAE

Microglia are cells of the myeloid lineage that reside in the CNS, play an important role in pathologies of many diseases associated with neuroinflammation such as MS [11,12,19]. During induction phase of EAE, microglia are immediately activated and take on antigen presenting cell (APC)-like capacity to activate naive T cells toward Th1 cells [19]. More important, the activated microglia cells are major source of a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-23p19, IL-1β, reactive oxygen intermediates and proteinases [13,14,19,20]. Not only do the released cytokine mediators damage CNS tissues, but they also activate and recruit other leukocytes into the CNS, thus amplifying pro-inflammation. For example, IL-23 potently drives Th17 cells, but, less likely, drives Th2 T cell differentiation and infiltration into the CNS, ultimately increasing local IL-17 production, an important cytokine in EAE pathogenesis [21–23]. Depletion of microglia attenuates TNF-α and NO, while at the same time reducing activation and recruitment of leukocytes into the CNS [21,24]. Similar effects are also observed in the mouse model, with blockade of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1 or B7-H1) and migration inhibitory factor (MIF) signaling in microglia. Mice with microglia depletion or attenuated activation develop milder EAE, accompanied by lower levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in the CNS [4,25,26]. These findings are also supported by significantly delayed EAE onset and reduced demyelination in the CNS after microglia depletion.

In addition, activated microglia are major source of chemokines, such as MIP, CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL12, CCL22, all of which play a role in development of EAE [27–29]. For example, blocking CCL2 signaling in glial cells significantly reduces disease onset, progression, and demyelination, accompanied by a lower level of maturation and recruitment of leukocytes and monocytes into the CNS [30].

Although activated microglial cells participate in EAE pathogenesis, they are also beneficial to CNS tissue integrity during inflammation [26]. Miron et al. reported that M2 dominant type microglia was beneficial to the oligodendrocyte differentiation in vitro and remyelination in the lesions of EAE and aged mice, and their produced specific protein Activin-A plays an important role in the beneficial effects [14] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and function of macrophage subtypes.

| M1 macrophages | References | M2 macrophages | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype marker | Arginase-2, iNOS, nitrotyrosine | [47,48,58,59,65] | CD206 (MR)+, CD163+, arginase-1, Ym1/2, RELM-α/FIZZ1 | [46–48,58–61,65] |

| Activation marker | High CD25, CD28, CD40, CD80, CD86, MHCII, NF-κB | [5,49,55,64] | Low CD40, CD86, MHCII, NF-κB | [5,49,55,64] |

| Inducing mediator | LPS, IFN-γ, IL-12 | [9,22,38,55,65] | IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, IL-33, IFN-β, CCL17, miR-124, Activin-A, Dectin-1, invariant NKT, glucocorticosteroids | [7,20,40,43,48,56,58,60,62,63,66,70,73,76] |

| Product | IL-6, IL-12/23p40,TNF-αt, IL-1β, iNOS, NO, MCP-1 | [9,48,50,52,53,71] | IL-1ra, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, TGF-β | [10,40,47,48,58,60,62,66,70] |

| Effect | Tissue damage, degeneration, suppress oligodendrocyte differentiation | [14,41,42,51,59] | Tissue repair, regeneration, drive oligodendrocyte differentiation | [14,41,42] |

| Disease | Induce EAE and MS | [23,24,28,38,52] | Suppress EAE and MS | [47,52,55,70] |

It is reported that microglia and astrocytes constitutively express a certain basal level of neurotrophic factors, such as nerve growth factor (NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) [31–34]. These factors can be up-regulated in an inflammatory environment from activated microglia/macrophages, and are beneficial to survival and differentiation of oligodendrocytes and neurons. Adoptive transfer of cells expressing these trophic factors improved neuron survival and nerve regeneration, and protected mice from EAE development[35].

3. Macrophages in EAE

There are few peripheral infiltrating macrophages in the CNS under physiological conditions. However, during induction and peak phases of EAE, massive infiltration of peripheral macrophages is seen in the meninges surrounding the CNS, the choroid plexus, and perivascular space, but the numbers of macrophages in the CNS are reduced during inflammation resolution and recovery phase, correlating with fewer lymphocyte infiltrates [36,37].

The increased migratory ability of activated macrophage into CNS is correlated to inflammation-induced high expression of chemokines and chemokine receptors, such as CCR2 from macrophages in mice [16]. It has been reported that in EAE up-regulation of CCL2, CCL3, CCL4 induces greater macrophage accumulation and effector function in the CNS [28–30,38]. At EAE onset, CCL22 (monocyte-derived thymus-specific chemokine) is greatly up-regulated in the draining LNs and spinal cord; in contrast, neutralization of CCL22 activity decreases macrophage accumulation in the CNS and causes milder EAE [38].

CCR4, a receptor for CCL17 and CCL22, is also up-regulated on macrophages of EAE mice, subsequently enhancing macrophage CNS infiltration. CCR4-deficient mice exhibit lower macrophage recruitment into the CNS and have milder EAE symptoms than wild type mice, associated with attenuated release of TNF-α from infiltrating macrophages [39].

The subtypes of macrophages and their role in the pathogenesis and regulation of MS/EAE are outlined below.

3.1. Phagocytosis of macrophages in EAE

During the peak and resolution phases, some infiltrating inflammatory cells proceed to apoptosis in the inflamed lesions, causing a decrease in the number of infiltrating cells in theinflamed area [40]. The accumulated apoptotic neurons, dead immune cell infiltrates, proteoglycan NG2 and myelin fragments may inhibit oligodendrocyte maturation and remyelination after damage, negatively affecting tissue repair. Immediate clearance of the debris is important for remyelination and functional recovery in the later phase [41,42]. Recent studies have confirmed the important role of macrophages in debris clearance, and this phagocytic ability is negatively correlated to cell activation markers and NF-[H9260]B activity [43–45]. Increased expression of mannose receptor CD206 and haptoglobin–hemoglobin scavenger receptor CD163 on activated macrophages may be responsible for the increased internalization and subsequent digestion of this debris in the later phase of EAE [41,42,46]. MMP-9 is also thought to be an important mediator in the phagocytic process of activated macrophages [31].

3.2. Classically activated macrophages in EAE

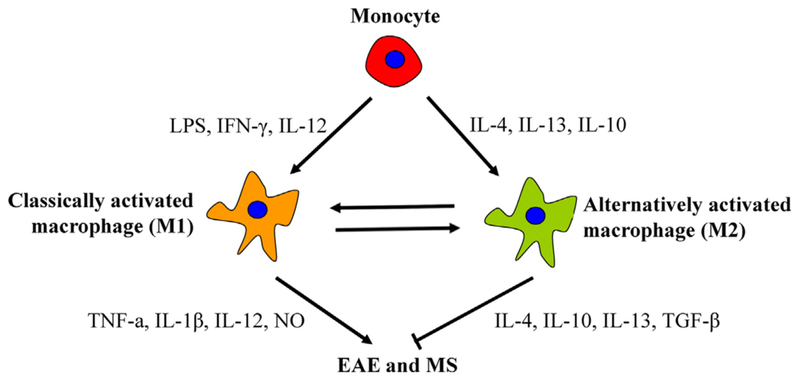

Recent studies have shown that pro-inflammatory cytokine-releasing macrophages are less potent than anti-inflammatory cytokine-releasing macrophages in phagocytosis of cell debris, implying two different macrophage phenotypes during the disease process, namely type 1 (M1) and type 2 (M2) macrophages [47,48] (Table 1). M1 cells are classically activated macrophages, predominantly presented in the early phase of EAE, whereas M2 cells are alternatively activated macrophages, predominantly presented in the later phase of EAE (Fig. 1). M1 cells are activated, express high levels of CD86, CD40, and MHCII on their surface, and have a potent ability in T cell priming and recruitment into the CNS. Blocking CD28 or CD40/CD40L signaling on the activated macrophages causes less activation and recruitment of T cells into the CNS, induce less severe EAE [49]. In addition, activated M1 cells produce large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-12, IL-6, iNOS, NO and proteases, and contribute to EAE development in the early phase [41,48,50,51]. In vivo and in vitro studies have confirmed their detrimental role in the survival and proliferation of oligodendrocytes and neurons in the CNS, ultimately causing demyelination and tissue injury [41,51]. In contrast, inhibition of NO production by iNOS inhibitors has been shown to suppress macrophage activation and T cell recruitment into the CNS, ultimately protect mice from neurodegeneration and EAE [52]. Thus, M1 cells critically participate in the pathogenesis of EAE, whereas suppressing M1 cell activation and recruitment may be beneficial for the suppression of EAE.

Fig. 1.

Scheme for immune pathways leading to activation of macrophage into two subtypes. M1 cells dominantly express TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12, NO, and induce CNS inflammation induction and tissue damage. M2 cells have specific maker CD206 (MR), dominantly express IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, TGF-β, and induce CNS inflammation resolution and tissue repair.

3.3. Alternatively activated macrophages in EAE

It is known that alternatively activated macrophages (M2 cells) co-exist with M1 cells throughout the course of disease development, although M2 cells are not the predominant macrophage subtype at the initial phase. The population of M2 cells underwent a gradual increase during the process of inflammation until the peak of disease, whereas the M1 cell population was relatively decreased in the later phase of disease development [40,47,48,53,54]. In EAE mice, the size of the CD206+ M2 cell population relative to the M1 cell population is greatest at disease peak. An increased M2 cell population in the peak and later stages may contribute to a decrease in inflammatory infiltrates by expressing anti-inflammatory cytokines. The beneficial function of M2 cells in EAE has been confirmed by recent in vitro and in vivo studies. For example, adoptive transfer of CD206+ M2 cells ex vivo significantly inhibits EAE development in mice [7,55], and the therapeutic effect is closely correlated to the specific anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles in the transferred M2 cells. Additional in vitro and in vivo studies have also revealed that M2 cells release a variety of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, IL-33 and TGF-β, which are known to be important mediators in EAE suppression [7,15,20,40]. The anti-inflammatory property of M2 cells is correlated to its lower NF-[H9260]B activation and higher phagocytosis potency than M1 cells [49,54–56]. In addition, the anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles of M2 cells drive differentiation and recruitment of Th2 and Treg cells into the peripheral lymph systems and inflamed CNS; thus, M2 cells synchronize with Th2 cells and Treg cells to exert their anti-inflammatory function [48].

Among Th2 type anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-4 and IL-13 have the potential to attenuate acute EAE in vivo by damping Th1 cytokine production, while decreased IL-4 and IL-13 levels may potentially induce more severe EAE [57]. However, it is reported that blocking IL-4/IL-13 signaling in IL-4Rα knock-out mice decreased onset and severity of relapsing EAE, suggesting that IL-4/IL-13 signaling may participate in the pathogenesis of relapsing EAE. While IL-4/IL-13 is a potent driver for M2 cell development, it would be interesting to further clarify M2 cell subtypes and their distinct roles in the pathogenesis of EAE. Recently M2 cells have been further identified as M2a and M2c cells. M2a cells are induced by IL-4/IL-13 and, in turn, induce T cells to produce high levels of IL-4 and IL-13. Although M2a cells may be beneficial to inflammation resolution in acute Th1 type inflammation, this cell phenotype may increase the risk of developing allergic responses and severe relapsing EAE [18,45,47,58]. M2c cells, which are potently induced by IL-10, TGF-β or glucocorticoids, predominantly produce high level of IL-10, but low levels of Th1/Th2 cytokines, which is beneficial to inflammation resolution in both Th1 and Th2 type inflammation, but the effects may compromise the ability of host immune system to fight against invading pathogens [59–61]. Therefore, the balance among macrophage subtypes is important in disease development, and a lack of balance among macrophage phenotypes may be either detrimental or beneficial to EAE progress.

3.4. Modulation of alternatively activated macrophages in EAE

M1 and M2 cell phenotypes are stably induced by LPS/IFN-γ and IL-4/IL-13 respectively in vitro, however due to cytokine environmental changes in vivo, they usually dynamically co-exist in the inflamed tissues during disease development, and the dynamic balance between the two phenotype population potentially determines the progression of EAE in vivo [52,54]. Recent studies indicate that iNOS is a potent inducer for M1 cell polarization, while arginase-1 is a potent inducer for M2 cell polarization [52,62]. Thus, iNOS and arginase-1 respectively catalyze l-arginine into a proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory mediator. During the induction phase, there is higher iNOS activity than arginase-1, but during the peak and recovery phase, iNOS activity is decreased, while arginase-1 activity is increased, leading to a larger M2 cell population in the later phase [53]. Expression of iNOS and arginase-1 is known up-regulated by IFN-γ and activin A, respectively [54,62].

How M2 cell are induced during disease progression is still not clear, and it is likely that a larger M2 cell population is derived from resting naïve monocytes or from polarized activated M1 cells. A growing body of evidences showed that a M2 cell biased switch from polarized M1 cells may contribute to the increased population of M2 cells in the CNS during the later phase of disease, suggesting that macrophage subpopulations are reversible under certain circumstances [40]. Furlan et al. reported that delivery of IL-4 by a nonreplicative herpes simplex type 1 viral vector into CNS downregulated expression of pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines, leading to deactivation of M1 macrophages to M2 cell type [63]. There is a small population of cells in and out of inflamed CNS and regional lymph nodes during the later stage of EAE; some infiltrating macrophages and other immune cells begin apoptosis, cause lower number of infiltrates in the CNS [64]. Macrophages become less activated compared to those at initial phase, indicating that macrophage phenotype is reversible at the different stages of disease [65].

It is indicated that the majority of Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-10, IL-13 and IL-33, are potent inducers of M2 cell polarization and macrophage deactivation. Cells treated with M-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, TGF-β and dexamethasone express more CD206 and CD163 [40,47,62]; Whereas macrophages and microglia treated with inhibitor of the CSF-1 receptor (CSF-1R) express lower M2 cell markers in vivo [15]. Not only is IL-10 a potent inducer of Treg cells, but it also increases macrophage polarization toward IL-10-expressing M2c cells. In addition, administration of CCL17 attenuates M1 cell differentiation, meanwhile increases Treg cell and M2c cell number. IL-10, in association with CCL17 can prevent macrophage polarization toward IL-13-producing M2a and pro-inflammatory M1 cells by rendering macrophages unresponsive to IL-13 [66]. IL-33 is a new member of the IL-1 cytokine family signaling through IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2. Recent studies have shown that IL-33 treatment protects mice from developing EAE, correlated to an increased population of M2 cells and production of IL-5, IL-13, and GM-CSF in the CNS and peripheral immune system [7].

3.5. Therapeutics of alternatively activated macrophages in EAE

Given that an imbalance between M1 and M2 cells from blood and CNS are an important mechanism in EAE development; imbalanced macrophage phenotypes worsen or ameliorate EAE [47], and molecular intervention by modulating macrophage pheno-types become a novel therapeutic approach in the treatment of EAE. Recent studies have provided evidences that augmentation and restoration of anti-inflammatory phenotype M2 cells in vivo are shown effective in protecting mice from EAE, and adoptive transfer of activated M2 cells suppress ongoing severe EAE [55]. Interestingly, exogenously administered M2 cells are not detected in lesions after adoptive transfer, and their beneficial effects may be derived from elevated release of Th2-type cytokines from transferred M2 cells in a peripheral compartment such as spleen or liver [47,67].

Although bone marrow and blood precursor cells are important sources for M2 cell culture in vitro for cell-based therapy, it would be beneficial to modulate endogenous macrophage phenotypes toward M2 phenotype in the treatment of EAE mice or MS patients. Recently, researchers have developed a variety of reagents, such as resveratrol, neuropeptide Y (NPY), valproic acid, tuftsin and fasudil in the treatment of EAE and MS [48,50,64,68,69]. The treated mice usually have lower levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12/23p40 and free radical NO, but higher levels of IL-10 and arginase-1 from CD206+ M2 cells at the peak of EAE (day 14), displaying a M2 cell biased polarization after the treatment [48].

Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone), a compound used in the treatment of MS patients, is a random polypeptide composed of four amino acids designed to mimic myelin basic protein (MBP). Copaxone-treated patients have experienced a lower relapse rate and reduced progression of disability, in association with increased IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13 and TGF-β, but reduced TNF-α and NO from activated macrophages, showing a M2 cell biased polarization [70]. Other therapeutics including dexamethasone and IFN-β are used in EAE and MS therapeutics [71–73]. EAE mice treated with dexamethasone phosphate loaded long-circulating liposomes (LCLDXP) and patients treated with IFN-β compound have significantly lower disease onset and severity, with increased macrophage polarization toward anti-inflammatory M2 cell phenotype [73–75]. However, the treatment may increase susceptibility of patients to invading microorganisms, leading to more severe inflammation. Local manipulation of macrophage phenotypes may therefore be safer in disease treatment. Recently, microRNA is developed as potential therapeutics by suppressing local microglia/macrophage activation in EAE. MiR-124 is the most abundant brain-specific microRNA, widely expressed in microglia/macrophages, and it plays an important role in microglia/macrophages quiescence in the CNS and periphery. In severe EAE, miR-124 activity is decreased, correlated to high activation of microglia/macrophages; administration of exogenous miR-124 suppresses EAE, accompanied with lower activation and proliferation of macrophages and TNF-α release [20,76]. Infiltrating leukocytes and CD11b+CD45hi peripheral macrophages are decreased in the CNS of treated mice [77]. Study in vitro also show that miR-124 induces a M2 phenotype of macrophages, i.e., attenuated CD86, MHCII and TNF-α, but up-regulated TGF-β1, arginase I and FIZZ1 expression on macrophages after miR-124 treatment. Thus induction of M2 phenotype of macrophages in vivo may be a promising therapeutic approach toward treatment of EAE and MS.

4. Conclusions and prospective

Microglia/macrophages are considered key players in the development of EAE and MS. Their detrimental and beneficial properties critically influence disease progress. During the early phase of disease, microglia/macrophages are classically activated (M1 cells) and exert pathogenic effects on CNS; during the recovery phase, macrophages become less activated or alternatively activated (M2 cells). The less activated M2 cells express higher levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines than M1 cells, and play an important role in CNS inflammation resolution and tissue repair. The macrophage subpopulation co-exists in vivo, and presents plastic properties in the CNS and peripheral lymph system during the disease progress. M2 cell-biased polarization by molecular intervention is thus a potential therapeutic approach in the treatment of EAE and MS.

Acknowledgment

We thank Katherine Regan for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Hickey WF. The pathology of multiple sclerosis: a historical perspective. J Neuroimmunol 1999;98:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Banwell B, Bar-Or A, Arnold DL, Sadovnick D, Narayanan S, McGowan M, et al. Clinical, environmental, and genetic determinants of multiple sclerosis in children with acute demyelination: a prospective national cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:436–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lassmann H, Bruck W, Lucchinetti C. Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis pathogenesis: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Trends Mol Med 2001;7:115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Turrin NP. Central nervous system Toll-like receptor expression in response to Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus-induced demyelination disease in resistant and susceptible mouse strains. Virol J 2008;5:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Almolda B, Gonzalez B, Castellano B. Antigen presentation in EAE: role of microglia, macrophages and dendritic cells. Front Biosci 2011;16: 1157–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bailey SL, Schreiner B, McMahon EJ, Miller SD. CNS myeloid DCs presenting endogenous myelin peptides ‘preferentially’ polarize CD4+ T(H)-17 cells in relapsing EAE. Nat Immunol 2007;8:172–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jiang HR, Milovanovic M, Allan D, Niedbala W, Besnard AG, Fukada SY, et al. IL-33 attenuates EAE by suppressing IL-17 and IFN-gamma production and inducing alternatively activated macrophages. Eur J Immunol 2012;42:1804–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jiang Z, Li H, Fitzgerald DC, Zhang GX, Rostami A. MOG(35–55) i.v. suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis partially through modulation of Th17 and JAK/STAT pathways. Eur J Immunol 2009;39:789–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Xiao BG, Ma CG, Xu LY, Link H, Lu CZ. IL-12/IFN-gamma/NO axis plays critical role in development of Th1-mediated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Mol Immunol 2008;45:1191–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lavasani S, Dzhambazov B, Nouri M, Fak F, Buske S, Molin G, et al. A novel probiotic mixture exerts a therapeutic effect on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mediated by IL-10 producing regulatory T cells. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e9009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rawji KS, Yong VW. The benefits and detriments of macrophages/microglia in models of multiple sclerosis. Clin Dev Immunol 2013;2013:948976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Abourbeh G, Theze B, Maroy R, Dubois A, Brulon V, Fontyn Y, et al. Imaging microglial/macrophage activation in spinal cords of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis rats by positron emission tomography using the mitochondrial 18 kDa translocator protein radioligand [(1)(8)F]DPA-714. J Neurosci 2012;32:5728–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Butovsky O, Jedrychowski MP, Moore CS, Cialic R, Lanser AJ, Gabriely G, et al. Identification of a unique TGF-beta-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat Neurosci 2014;17:131–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Miron VE, Boyd A, Zhao JW, Yuen TJ, Ruckh JM, Shadrach JL, et al. M2 microglia and macrophages drive oligodendrocyte differentiation during CNS remyeli-nation. Nat Neurosci 2013;16:1211–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pyonteck SM, Akkari L, Schuhmacher AJ, Bowman RL, Sevenich L, Quail DF, et al. CSF-1R inhibition alters macrophage polarization and blocks glioma progression. Nat Med 2013;19:1264–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Saederup N, Cardona AE, Croft K, Mizutani M, Cotleur AC, Tsou CL, et al. Selective chemokine receptor usage by central nervous system myeloid cells in CCR2-red fluorescent protein knock-in mice. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e13693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Trebst C, Sorensen TL, Kivisakk P, Cathcart MK, Hesselgesser J, Horuk R, et al. CCR1+/CCR5+ mononuclear phagocytes accumulate in the central nervous system of patients with multiple sclerosis. Am J Pathol 2001;159:1701–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Veremeyko T, Starossom SC, Weiner HL, Ponomarev ED. Detection of microRNAs in microglia by real-time PCR in normal CNS and during neuroinflammation. J Vis Exp 2012;10:3791–4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Aloisi F, Ria F, Penna G, Adorini L. Microglia are more efficient than astrocytes in antigen processing and in Th1 but not Th2 cell activation. J Immunol 1998;160:4671–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ponomarev ED, Veremeyko T, Barteneva N, Krichevsky AM, Weiner HL. MicroRNA-124 promotes microglia quiescence and suppresses EAE by deactivating macrophages via the C/EBP-alpha-PU.1 pathway. Nat Med 2011;17:64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Heppner FL, Greter M, Marino D, Falsig J, Raivich G, Hovelmeyer N, et al. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis repressed by microglial paralysis. Nat Med 2005;11:146–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Li J, Gran B, Zhang GX, Ventura ES, Siglienti I, Rostami A, et al. Differential expression and regulation of IL-23 and IL-12 subunits and receptors in adult mouse microglia. J Neurol Sci 2003;215:95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ponomarev ED, Shriver LP, Maresz K, Pedras-Vasconcelos J, Verthelyi D, Dittel BN. GM-CSF production by autoreactive T cells is required for the activation of microglial cells and the onset of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 2007;178:39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Oleszak EL, Zaczynska E, Bhattacharjee M, Butunoi C, Legido A, Katsetos CD. Inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine are found in monocytes/macrophages and/or astrocytes in acute, but not in chronic, multiple sclerosis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 1998;5:438–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cox GM, Kithcart AP, Pitt D, Guan Z, Alexander J, Williams JL, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor potentiates autoimmune-mediated neuroinflammation. J Immunol 2013;191:1043–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hanisch UK, Kettenmann H. Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat Neurosci 2007;10:1387–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dheen ST, Kaur C, Ling EA. Microglial activation and its implications in the brain diseases. Curr Med Chem 2007;14:1189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Forde EA, Dogan RN, Karpus WJ. CCR4 contributes to the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by regulating inflammatory macrophage function. J Neuroimmunol 2011;236:17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Karpus WJ, Kennedy KJ. MIP-1alpha and MCP-1 differentially regulate acute and relapsing autoimmune encephalomyelitis as well as Th1/Th2 lymphocyte differentiation. J Leukoc Biol 1997;62:681–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Brini E, Ruffini F, Bergami A, Brambilla E, Dati G, Greco B, et al. Administration of a monomeric CCL2 variant to EAE mice inhibits inflammatory cell recruitment and protects from demyelination and axonal loss. J Neuroimmunol 2009;209:33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Larsen PH, Wells JE, Stallcup WB, Opdenakker G, Yong VW. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 facilitates remyelination in part by processing the inhibitory NG2 proteoglycan. J Neurosci 2003;23:11127–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Coull JA, Beggs S, Boudreau D, Boivin D, Tsuda M, Inoue K, et al. BDNF from microglia causes the shift in neuronal anion gradient underlying neuropathic pain. Nature 2005;438:1017–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Elkabes S, DiCicco-Bloom EM, Black IB. Brain microglia/macrophages express neurotrophins that selectively regulate microglial proliferation and function. J Neurosci 1996;16:2508–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Herx LM, Rivest S, Yong VW. Central nervous system-initiated inflammation and neurotrophism in trauma: IL-1 beta is required for the production of ciliary neurotrophic factor. J Immunol 2000;165:2232–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Weber MS, Prod’homme T, Youssef S, Dunn SE, Rundle CD, Lee L, et al. Type II monocytes modulate T cell-mediated central nervous system autoimmune disease. Nat Med 2007;13:935–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Aguzzi A, Barres BA, Bennett ML. Microglia: scapegoat, saboteur, or something else. Science 2013;339:156–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ousman SS, Kubes P. Immune surveillance in the central nervous system. Nat Neurosci 2012;15:1096–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Dogan RN, Long N, Forde E, Dennis K, Kohm AP, Miller SD, et al. CCL22 regulates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by controlling inflammatory macrophage accumulation and effector function. J Leukoc Biol 2011;89:93–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Columba-Cabezas S, Serafini B, Ambrosini E, Sanchez M, Penna G, Adorini L, et al. Induction of macrophage-derived chemokine/CCL22 expression in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and cultured microglia: implications for disease regulation. J Neuroimmunol 2002;130:10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Porcheray F, Viaud S, Rimaniol AC, Leone C, Samah B, Dereuddre-Bosquet N, et al. Macrophage activation switching: an asset for the resolution of inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol 2005;142:481–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hendriks JJ, Teunissen CE, de Vries HE, Dijkstra CD. Macrophages and neurode-generation. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2005;48:185–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Neumann H, Kotter MR, Franklin RJ. Debris clearance by microglia: an essential link between degeneration and regeneration. Brain 2009;132:288–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chang CP, Su YC, Hu CW, Lei HY. TLR2-dependent selective autophagy regulates NF-kappaB lysosomal degradation in hepatoma-derived M2 macrophage differentiation. Cell Death Differ 2013;20:515–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chang CP, Su YC, Lee PH, Lei HY. Targeting NFKB by autophagy to polarize hepatoma-associated macrophage differentiation. Autophagy 2013;9: 619–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Moreira AJ, Fraga C, Alonso M, Collado PS, Zetller C, Marroni C, et al. Quercetin prevents oxidative stress and NF-kappaB activation in gastric mucosa of portal hypertensive rats. Biochem Pharmacol 2004;68:1939–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kristiansen M, Graversen JH, Jacobsen C, Sonne O, Hoffman HJ, Law SK, et al. Identification of the haemoglobin scavenger receptor. Nature 2001;409:198–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Mikita J, Dubourdieu-Cassagno N, Deloire MS, Vekris A, Biran M, Raffard G, et al. Altered M1/M2 activation patterns of monocytes in severe relapsing experimental rat model of multiple sclerosis. Amelioration of clinical status by M2 activated monocyte administration. Mult Scler 2011;17:2–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Liu C, Li Y, Yu J, Feng L, Hou S, Liu Y, et al. Targeting the shift from M1 to M2 macrophages in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice treated with fasudil. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e54841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Girvin AM, Dal Canto MC, Miller SD. CD40/CD40L interaction is essential for the induction of EAE in the absence of CD28-mediated co-stimulation. J Autoimmun 2002;18:83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Imler TJ Jr, Petro TM. Decreased severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis during resveratrol administration is associated with increased IL-17+IL-10+T cells, CD4(−) IFN-gamma+ cells, and decreased macrophage IL-6 expression. Int Immunopharmacol 2009;9:134–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kigerl KA, Gensel JC, Ankeny DP, Alexander JK, Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci 2009;29:13435–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Shin T, Kim S, Moon C, Wie M, Kim H. Aminoguanidine-induced amelioration of autoimmune encephalomyelitis is mediated by reduced expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in the spinal cord. Immunol Invest 2000;29:233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Berard JL, Kerr BJ, Johnson HM, David S. Differential expression of SOCS1 in macrophages in relapsing-remitting and chronic EAE and its role in disease severity. Glia 2010;58:1816–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Shin T, Ahn M, Matsumoto Y. Mechanism of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in Lewis rats: recent insights from macrophages. Anat Cell Biol 2012;45:141–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Tierney JB, Kharkrang M, La Flamme AC. Type II-activated macrophages suppress the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Immunol Cell Biol 2009;87:235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Denney L, Kok WL, Cole SL, Sanderson S, McMichael AJ, Ho LP. Activation of invariant NKT cells in early phase of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis results in differentiation of Ly6Chi inflammatory monocyte to M2 macrophages and improved outcome. J Immunol 2012;189:551–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Keating P, O’Sullivan D, Tierney JB, Kenwright D, Miromoeini S, Mawasse L, et al. Protection from EAE by IL-4Ralpha(−/−) macrophages depends upon T regulatory cell involvement. Immunol Cell Biol 2009;87:534–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Veremeyko T, Siddiqui S, Sotnikov I, Yung A, Ponomarev ED. IL-4/IL-13-dependent and independent expression of miR-124 and its contribution to M2 phenotype of monocytic cells in normal conditions and during allergic inflammation. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e81774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Chhor V, Le Charpentier T, Lebon S, Ore MV, Celador IL, Josserand J, et al. Characterization of phenotype markers and neuronotoxic potential of polarised primary microglia in vitro. Brain Behav Immun 2013;32:70–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Elcombe SE, Naqvi S, Van Den Bosch MW, MacKenzie KF, Cianfanelli F, Brown GD, et al. Dectin-1 regulates IL-10 production via a MSK1/2 and CREB dependent pathway and promotes the induction of regulatory macrophage markers. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e60086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Martinez FO, Sica A, Mantovani A, Locati M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Front Biosci 2008;13:453–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ogawa K, Funaba M, Chen Y, Tsujimoto M. Activin A functions as a Th2 cytokine in the promotion of the alternative activation of macrophages. J Immunol 2006;177:6787–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Furlan R, Poliani PL, Galbiati F, Bergami A, Grimaldi LM, Comi G, et al. Central nervous system delivery of interleukin 4 by a nonreplicative herpes simplex type 1 viral vector ameliorates autoimmune demyelination. Hum Gene Ther 1998;9:2605–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Dimitrijevic M, Mitic K, Kustrimovic N, Vujic V, Stanojevic S. NPY suppressed development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in Dark Agouti rats by disrupting costimulatory molecule interactions. J Neuroimmunol 2012;245:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Stout RD, Suttles J. Functional plasticity of macrophages: reversible adaptation to changing microenvironments. J Leukoc Biol 2004;76:509–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Katakura T, Miyazaki M, Kobayashi M, Herndon DN, Suzuki F. CCL17 and IL-10 as effectors that enable alternatively activated macrophages to inhibit the generation of classically activated macrophages. J Immunol 2004;172: 1407–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].King IL, Dickendesher TL, Segal BM. Circulating Ly-6C+ myeloid precursors migrate to the CNS and play a pathogenic role during autoimmune demyelinating disease. Blood 2009;113:3190–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Zhang Z, Zhang ZY, Wu Y, Schluesener HJ. Valproic acid ameliorates inflammation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis rats. Neuroscience 2012;221:140–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wu M, Nissen JC, Chen EI, Tsirka SE. Tuftsin promotes an anti-inflammatory switch and attenuates symptoms in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e34933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Jung S, Siglienti I, Grauer O, Magnus T, Scarlato G, Toyka K. Induction of IL-10 in rat peritoneal macrophages and dendritic cells by glatiramer acetate. J Neuroimmunol 2004;148:63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Linker RA, Luhder F, Kallen KJ, Lee DH, Engelhardt B, Rose-John S, et al. IL-6 transsignalling modulates the early effector phase of EAE and targets the blood–brain barrier. J Neuroimmunol 2008;205:64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Linker RA, Weller C, Luhder F, Mohr A, Schmidt J, Knauth M, et al. Liposomal glucocorticosteroids in treatment of chronic autoimmune demyelination: long-term protective effects and enhanced efficacy of methylprednisolone formulations. Exp Neurol 2008;211:397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Inoue M, Williams KL, Oliver T, Vandenabeele P, Rajan JV, Miao EA, et al. Interferon-beta therapy against EAE is effective only when development of the disease depends on the NLRP3 inflammasome. Sci Signal 2012;5:ra38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Crielaard BJ, Lammers T, Morgan ME, Chaabane L, Carboni S, Greco B, et al. Macrophages and liposomes in inflammatory disease: friends or foes. Int J Pharm 2011;416:499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Galligan CL, Pennell LM, Murooka TT, Baig E, Majchrzak-Kita B, Rahbar R, et al. Interferon-beta is a key regulator of proinflammatory events in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Mult Scler 2010;16:1458–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Ponomarev ED, Veremeyko T, Weiner HL. MicroRNAs are universal regulators of differentiation, activation, and polarization of microglia and macrophages in normal and diseased CNS. Glia 2013;61:91–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Makeyev EV, Zhang J, Carrasco MA, Maniatis T. The MicroRNA miR-124 promotes neuronal differentiation by triggering brain-specific alternative premRNA splicing. Mol Cell 2007;27:435–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]