Abstract

Functional smooth muscle engineering requires isolation and expansion of smooth muscle cells (SMCs), and this process is particularly challenging for visceral smooth muscle tissue where progenitor cells have not been clearly identified. Herein we showed for the first time that efficient SMCs can be obtained from human amniotic fluid stem cells (hAFSCs). Clonal lines were generated from c-kit+ hAFSCs. Differentiation toward SM lineage (SMhAFSCs) was obtained using a medium conditioned by PDGF-BB and TGF-β1. Molecular assays revealed higher level of α smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), desmin, calponin, and smoothelin in SMhAFSCs when compared to hAFSCs. Ultrastructural analysis demonstrated that SMhAFSCs also presented in the cytoplasm increased intermediate filaments, dense bodies, and glycogen deposits like SMCs. SMhAFSC metabolism evaluated via mass spectrometry showed higher glucose oxidation and an enhanced response to mitogenic stimuli in comparison to hAFSCs. Patch clamp of transduced hAFSCs with lentiviral vectors encoding ZsGreen under the control of the α-SMA promoter was performed demonstrating that SMhAFSCs retained a smooth muscle cell-like electrophysiological fingerprint. Eventually SMhAFSCs contractility was evident both at single cell level and on a collagen gel. In conclusion, we showed here that hAFSCs under selective culture conditions are able to give rise to functional SMCs.—Ghionzoli, M., Repele, A., Sartiani, L., Costanzi, G., Parenti, A., Spinelli, V., David, A. L., Garriboli, M., Totonelli, G., Tian, J., Andreadis, S. T., Cerbai, E., Mugelli, A., Messineo, A., Pierro, A., Eaton, S., De Coppi, P. Human amniotic fluid stem cell differentiation along smooth muscle lineage.

Keywords: tissue engineering, myogenic, regenerative medicine, fetal cells, multipotent

Smooth muscle cells (SMCs) play a pivotal role in the functionality of numerous tissues and organs, including gastrointestinal, urinary, respiratory, cardiovascular, and reproductive tracts. Therefore, SMCs are important in the engineering of hollow organs, including esophagus (1), intestine (2), urinary bladder (3), and blood vessels (4). However, the generation of tissue-engineered structures for clinical application requires the isolation and expansion of large numbers of cells, preserving cellular phenotype and physiology without inducing events of cellular senescence and dedifferentiation. These characteristics are difficult to obtain with SMCs, where expansion while minimizing dedifferentiation and control of the differentiation processes toward functional myogenesis still remains a challenge (5). Indeed, phenotypical plasticity of SMCs may occur both in vitro and in vivo, where SMCs reversibly shift along a continuum from a quiescent, contractile phenotype to a synthetic phenotype, characterized by proliferation and extracellular matrix synthesis (6–8). Still, these processes of cellular dedifferentiation, phenotypical modifications, and aging related to in vitro cell expansion for the most part are yet to be elucidated. Likewise, the processes to either prevent or induce such modifications by biochemical or biomechanical agents are unknown. In particular, while progress has been made on isolating smooth muscle vasculature precursors (9), limitations are still present in the expansion and differentiation of visceral SMCs (10–12).

Stem cells capable of differentiation toward a smooth muscle phenotype may have a key role in both vascular and hollow organ tissue engineering, holding promise for regenerative medicine applications. There have been various attempts to derive functional SMCs, using embryonic stem cells (ESCs), adult stem cells, and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (13–19). Some studies reported in vitro cellular models of differentiation and focused mainly on intracellular mechanisms that regulate the process and the acquisition of phenotypical characteristics shared with SMCs (19–21). A minority of studies also tested the acquisition of functional properties such as contraction that are essential to define smooth muscle differentiation (14, 15, 22). In the present study, we explore acquisition of both smooth muscle phenotype and function by human amniotic fluid stem cells (hAFSCs). hAFSCs represent ∼1% of the total cells available from human amniocentesis specimens obtained for prenatal genetic diagnosis and can be immunoselected for c-kit (CD117), a marker of differentiation (23). We have demonstrated that these cells share common features with both ESCs and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). They express markers of pluripotency, are capable of differentiation in vitro and in vivo into lineages deriving from 3 germ layers, but fail to form teratomas when injected into immunocompromised animals (23). An advantage of AFSCs is that they can be obtained early in pregnancy and therefore could be expanded and used to engineer tissue for treatment of fetal malformation (24) diagnosed in utero. When injected in models of disease we have previously observed that both human (25) and rat (26) AFSCs can assume a smooth muscle phenotype. However, it remains unclear whether AFSCs can generate functional SMCs in vitro. In this study we explored the generation of SMCs starting from human AFSC cultures using a combined functional analysis approach testing their molecular, electrophysiological, and metabolic properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

hAFSC isolation and expansion

hAFSCs were prepared as described previously (23). Samples of amniotic fluid were collected by amniocentesis (gestational age 14–25 wk) during routine prenatal diagnosis of women attending the Fetal Medicine Unit at University College London Hospital (UCLH), after written consent was obtained. The study (number 08/0304) was approved by the Joint UCL/UCLH Committees on the Ethics of Human Research. Samples were spun at 1500 rpm and pellets resuspended and seeded in Chang medium [α-MEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 15% FBS, 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), supplemented with 18% Chang B and 2% Chang C (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA, USA)] at 37°C with 5% CO2 atmosphere. After 3 d, nonadherent cells and debris were discarded and the adherent cells were cultivated in preconfluency. Adherent cells were then immunomagnetically sorted for the expression of the stem marker c-kit using a mouse monoclonal anti-c-kit (CD117) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and the anti-mouse IgG Cellection Dynabeads M-450 antibody (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA, USA). c-kit+ hAFSCs were reseeded at a density of 2 × 103 cells/cm2, expanded in Chang medium in 5% CO2 at 37°C, and subsequently cloned by limiting dilution and maintained in optimal culture condition of subconfluency (maximum 50%).

Isolation and culture of human bladder SMCs (hBSMCs) from human bladder tissue

hBSMCs were isolated as previously reported (27). Human bladder biopsy was placed in a 100 Ø Petri dish and rinsed several times with washing solution [1× PBS (Gibco), 2.5% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), and 1 mg/ml fungizone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)] in order to remove the blood. The tissue was transferred in a new Petri dish, mucosa and submucosa layers and fibrotic and fat tissue were discarded, and the muscularis layer was preserved and cut into small pieces. Collagenase solution [10 ml; 2 mg/ml collagenase type IV (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ, USA), 1 mg/ml fungizone (Sigma), and DMEM/F12 (Gibco)] was added to the Petri dish, and the pieces were pipetted accurately and enzimatically digested in an incubator for 1 h. After the digestion, the tissue was transferred in a 50-ml tube and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was suspended with culture medium [DMEM/F12 (Gibco), 10% FBS, 1 mg/ml fungizone (Sigma), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco)] and plated in a 100 Ø Petri dish (standard culture conditions). The medium was changed after 3 d to permit the adhesion of isolated muscle cells and replaced every 2 d. Thereafter, it was replaced with the medium used to differentiate and maintain SMCs from human amniotic fluid stem cells. The cells were split at 80% of confluence (1 wk after the isolation).

Differentiation of hAFSCs

Cell differentiation and growth rate assessment

In order to induce smooth muscle differentiation, hAFSCs were maintained for about 4 wk in differentiation medium [high-glucose DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 15% FBS, 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) supplemented with 5 ng/ml platelet-derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB) and 2.5 ng/ml transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1)]. Cell medium was changed every 48 h. To determine growth rate of hAFSCs and smooth muscle hAFSCs (SMhAFSCs), cells were seeded in 12-well dishes (1000 cells/well) and cultured in appropriate conditions for up to 7 d. Cells were trypsinized every day, and cell number was assessed by trypan blue dye and counted in a Burker chamber in a blinded procedure. Cells were also analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Molecular assessment

Total cellular RNA was isolated from cell cultures using TRIzol. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from RNA using SuperScript II Reverse-Transcriptase reagents (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Suitable real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) oligonucleotide primers were manually designed for each of the genes to ensure maximal efficiency and sensitivity. Qualitative PCR was performed with Taq polymerase protocol (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions; real-time PCR was performed using the default thermocycler program for all genes: 3 min of preincubation at 94°C, followed by 50 cycles for 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 45 s at 72°C. Individual real-time PCR reactions were carried out in 30-μl volumes in a 96-well plate (Applied Biosystems, London, UK) containing 8 μl diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) water, 1 μl of sense and antisense primers (10 μM), and 15 μl SYBR Green with ROX plus 5 μl of sample. Each experiment was repeated in triplicate, and quantitative PCR analysis was performed in triplicate and analyzed with the ΔCt method. GAPDH was used for normalization (Table 1). As positive control, a homogenized sample from human fetal intestine was used.

Table 1.

PCR primers

| Gene | Sequence | Accession number | Temperature (°C) | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hDesmin | F: CCGAGCGGACGTGGATGCAG | NM_001927 | 60 | 198 |

| R: ATGTCCCTGAGGGCGGCAGT | 60 | |||

| hMHC 11 | F: GCACGAGATGCCGCCTCACA | BC031040.1 | 60 | 237 |

| R: GGCAAAAGATGGGCCTTGCGTG | 60 | |||

| hCalponin | F: TGGCCAGCATGGCGAAGACG | NM_001299.4 | 60 | 207 |

| R: CTGTGCCCAGCTTGGGGTCG | 60 | |||

| hASMA | F: CCAGTGTGGAGCAGCCCAGC | NM_001613.2 | 60 | 193 |

| R: TCACCCCCTGATGTCTGGGACG | 60 | |||

| hGAPDH | F: AGGCTGGGGCTCATTTGCAGG | NM_002046.3 | 60 | 171 |

| R: TGACCTTGGCCAGGGGTGCT | 60 | |||

| ACTB | F: ATTTTGAATGATGAGCCTTCG | NM_002046.3 | 56 | 121 |

| R: CAGTGTACAGGTAAGCCCTGG | 56 |

Ultrastructural analysis

Cells were resuspended in 10% BSA (Sigma) and PBS and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) for 18–24 h, at room temp. After fixation, the following steps were performed to prepare the sample for transmission electron microscopy analysis: osmium tetroxide, alcohol, propylene oxide, and resin. Thin sections (∼70 nm) were collected on copper grids, poststained with 0.4% lead citrate in 0.4% NaOH for 4–10 min, and rinsed with ultrapure water. Images were taken with a transmission electron microscope using a digital camera and were further processed (contrast enhancement) using standard imaging software (Photoshop CS4; Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

Immunofluorescence

Cover glasses seeded with 1000 cells/cm2 were washed thoroughly with 1 ml of PBS (Gibco) and fixed in a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Sigma) for 15–20 min. Cell were processed in 0.5% Triton and incubated with 500 μl of a solution of 3% BSA (Sigma) in PBS for 30 min to block nonspecific binding sites. Primary antibody (Table 2) was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were then rinsed quickly with the solution of 3% BSA in PBS and left to incubate with secondary antibody (Table 2) for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were then mounted with fluorescent mounting medium with DAPI (1.5 μg/ml, Vectashield; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) on a polylysine slide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and observed under an epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axiophot; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Table 2.

Antibodies

| Antibody | Dilution | Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | ||

| Mouse monoclonal antibody against hSMA | 1:100 | Dako (Carpinteria, CA, USA) |

| Rabbit polyclonal (human, mouse) antibody against smoothelin | 1:100 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) |

| Rabbit polyclonal (human, mouse) antibody against desmin | 1:30 | Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA) |

| Rabbit polyclonal (human, mouse) antibody against CD31 | 1:30 | Abcam |

| Mouse monoclonal (mouse, sheep, human) antibody against pancytokeratine | 1:50 | Abcam |

| Secondary | ||

| Goat anti-mouse IgG 594 nm | 1:150 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgG 488 nm | 1:150 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

Cell metabolism and assessment of proliferation after serum starvation and mitogenic stimulation

Carbon dioxide production

CO2 production was used as a marker of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. Two different types of culture medium were employed: DMEM, which contains 4500 μg/ml (25 mM) d-glucose, sodium pyruvate, and sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3; 44 mM); and DMEM with NaHCO3 (44 mM) and no glucose, supplemented with 25 mM of [U-13C] d-glucose.

Both undifferentiated and differentiated cells were cultured in optimal conditions (see above) in hermetic screw-cap 25-cm2 flasks (Corning-Sigma-Aldrich, Corning, NY, USA) at 1000 cells/cm2. Medium supplemented with [U-13C] d-glucose was substituted for culture medium, and flasks were sealed for 4 h. Samples of gas from the flask were removed for analysis. Following this, 500 μl culture medium was transferred to a 12 ml glass tube (Exetainer, Labco, UK), and glacial acetic acid (100 μl) was injected through the septum to release CO2 from bicarbonate. 13CO2/12CO2was measured in the gas phase (gas samples and released from tissue culture medium) by isotope ratio mass spectrometry. The ratio of 13CO2 to 12CO2 produced is proportional to the quantity of oxidized glucose (28).

Cell proliferation after serum starvation

Cell proliferation was quantified by the total cell number as well as the total DNA/well via a fluorescent dye (Cell Proliferation Kit; Invitrogen). Cells (1.5×103/100 μl) suspended in differentiation medium were seeded on 0.1% gelatin-coated flat-bottom 96-multiwell plates and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were kept in starving conditions (0.1% FBS) for 24 h, and then medium was removed and replaced with 1% FBS medium containing test substances such as 15% FBS, 10 ng/ml PDGF-BB, 20 ng/ml FGF-β, 5 ng/ml TGF-β1, or 10 ng/ml PDGF-BB + 5 ng/ml TGF-β1. After 48 h, cells were fixed with methanol and stained with Diff-Quik (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA). Cell duplication was assessed by counting the total cell number in 10 random fields of each well at ×200 with the aid of a 21-mm2 grid. Moreover, proliferation was assessed by total DNA/well. After 48 h, 100 μl of dye binding solution was added to each microplate well and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. This incubation period is required for equilibration of dye-DNA binding, resulting in a stable fluorescence end point. The fluorescence intensity was read using a fluorescence microplate reader with excitation at 485 nm and emission detection at 530nm.

Viral transduction

hAFSCs were transduced according to methods previously described (29). hAFSCs at 105 cells/well were transfected using a lentiviral vector (Table 3) encoding Zoanthus sp. green fluorescent protein (ZsGreen) under the control of the α smooth muscle actin promoter (P-α-SMA), in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene (1×). Viral vector was then removed 72 h after infection; cells were monitored under fluorescence microscope, washed twice with PBS, and Chang medium was added.

Table 3.

P-α-SMA primer sequences

| Gene | Sequence |

|---|---|

| P-α-SMA | F: ACAACAATCGATAACAGCTGGTCATGGCTGTA |

| R: TGTTGTACCGGTGCATGAACCCAGCCAAATCC |

Underlined sequences represent the restriction sites ClaI (ATCGAT) and AgeI (ACCGGT).

Genomic sequences

P-α-SMA was amplified with PCR from human genomic DNA using the primers in Table 3. The underlined sequences (see Table 3) represent the restriction sites ClaI (ATCGAT) or AgeI (ACCGGT). The promoter sequences for P-α-SMA include 1438 bp upstream and 29 bp downstream of the transcriptional start site. The sequence was ligated into a lentiviral vector (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA) upstream of ZsGreen (P-α-SMA) between ClaI and AgeI restriction sites for P-α-SMA (Supplemental Fig. S1M). pIRES2-ZsGreen1 contains the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) of the encephalomyocarditis virus between a multiple cloning site (MCS) and the ZsGreen coding region. This design permits both the gene of interest (cloned into the MCS) and the ZsGreen1 gene to be translated from a single bicistronic mRNA. pIRES2-ZsGreen1 is designed for the efficient selection (by flow cytometry or other methods) of transiently transfected mammalian cells expressing ZsGreen1 and the protein of interest (Supplemental Fig. S1I). This vector can be used to obtain stably transfected cell lines without time-consuming drug and clonal selection. As a result, mammalian cells transfected with this vector will express the green fluorescent protein when transcription of the α-SMA sequence is activated. Cells expressing ZsGreen (excitation and emission maxima: 496 and 506 nm, respectively) can be detected by fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry (Supplemental Fig. S1K). For the transfection HEK293T packaging cell line was used, a specific cell line originally derived from human embryonic kidney cells grown in tissue culture. These cells retain the gag, pol, and env genes, while the viral genome is replaced by the engineered transgene of choice. These cells were seeded on 10-cm plates and transfected the following day with 15 μg of vector by calcium phosphate DNA precipitation. They were grown as a monolayer in DMEM to confluency, and a high titer viral vector producer clone was identified. The viral vector was harvested 24 h post-transfection, filtered through a 0.45-μm filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA), pelleted by ultracentrifugation (50,000 g at 4°C for 2 h), and resuspended in fresh medium, 6 μg/ml of protamine sulfate (Sigma) and 1.23 M KCl (Sigma). Titers of lentiviral vector preparations were determined using 293T/17 cells and ranged between 107 and 108 IFU/ml.

Patch-clamp analysis

Cells were dissociated by a 5 min enzymatic digestion with 0.2 v/v 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (1×; Gibco)/PBS (Gibco). Digestion was stopped by adding PBS, and the sedimented cells were resuspended in Tyrode solution containing 0.5 mM CaCl2. After digestion, cells were stored and used within 5 h. The experimental setup for patch-clamp recordings and data acquisition was similar to that previously described (30). Briefly, dispersed cells were allowed to settle and adhere to the bottom of a 2-ml perfusion chamber mounted on the stage of a Nikon inverted microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Cells were superfused by means of a temperature-controlled (37°C) microsuperfusor, allowing rapid changes of the solution. Patch-clamp pipettes, prepared from glass capillary tubes (Harvard Apparatus, Kent, UK) by means of a 2-stage horizontal puller (P-87; Sutter Instrument Co, Novato, CA, USA), had a resistance of 2–3 MΩ when filled with the internal solution. Voltage clamp recordings were made with the perforated patch technique using amphotericin (31). A 30 mg/ml stock solution of amphotericin B was made, and 10 μl was mixed with 1 ml of the pipette solution. Tips were dipped in the pipette solution for a few seconds and then backfilled with the amphotericin-containing pipette solution. Adequate access to the cell interior was achieved when the access resistance was ≤20 MΩ, which was usually obtained after ≈5 min after gigaohm seal formation. Series resistance (Rs) and membrane capacitance (Cm) were compensated to minimize the capacitive transient and routinely checked during the experiment. Only cells showing a stable Cm and Rs were included in the analysis. The patch amplifier (Axopatch-1B; Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA) was connected to a DAC/ADC interface (Labmaster Tekmar, Scientific Solutions, North Chelmsford, MA, USA; Digidata 1200B, Axon Instruments) and a computer that allows online data view. Experimental control, data acquisition, and preliminary analysis were performed by means of the integrated software package pClamp (Axon Instruments). From a holding potential of −70 mV, outward currents were elicited by depolarizing steps to −50/+120 mV. Peak and steady-state currents were measured as peak outward current at the beginning of the depolarizing step and steady-state currents at the end of the step. Current amplitudes were normalized with respect to cell membrane capacitance (Cm, pF), which was measured by applying a ±10-mV pulse starting from a holding potential of −70 mV. A monoexponential fitting of the resulting current allowed computing Cm:

where (I0 − I∞) is the maximum level of current (relative to the holding current) following the depolarization, and τ is the time constant of the exponential current decay. The recording electrode solution contained (in mM) 140 KCl, 10 HEPES, 1 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2 (pH 7.3; buffered with KOH). Tyrode solution contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, and 10 d-glucose (pH 7.4; adjusted with NaOH. Tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA), 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), and carbachol (CCH) (all purchased from Sigma) were solubilized in Tyrode solution.

In vitro contractility assessment

Single-cell contraction

For each experiment, cell cultures were transferred from the incubator to a time-lapse microscope equipped with a heated stage, CO2 chamber, and plexiglas environmental chamber (Axiovert 200 and Axioexaminer; Zeiss). Cell cultures were maintained at routine incubation settings (37°C, 5% CO2) and optimum humidity. Temperature and CO2 concentration were independently maintained using digital controlling units (Zeiss). Sets of phase-contrast images from each well were taken in 10- to 20-s intervals using a compact monochrome interline transfer CCD camera. Images were acquired during a 42 min period. An Openlab software automation (Improvision, Lexington, MA, USA) drove the camera and compiled the acquired phase images. Images were subsequently processed as TIFF movies using ImageJ (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Collagen lattice assay

Cell-embedded collagen lattices were employed to measure contractile forces both in hAFSCs and SMhAFSCs as described previously for other cell sources (17, 32–34). Briefly, an aliquot containing 6 × 105 cells/ml was mixed with soluble type I collagen (1 mg/ml; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) containing NaOH, DMEM 10× mixture, and NaHCO3 to create a cell-collagen suspension. An aliquot (250 μl) of the cell-collagen suspension was placed onto a 12-well tissue culture plate (BD Biosciences) and allowed to polymerize. A side-by-side comparison of cells with and without collagen mixture was performed that served as negative control. Initial lattice diameter was noted before mechanical release of the cell-collagen lattices for contractile force measurement. The diameter of the cell-collagen lattices was measured after release (from 1 to 10 min), and the relative change in diameter was calculated. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Lattices were released after administration of agonist (10 mmol potassium chloride; Sigma) in serum-free medium. The percentage of contraction was calculated by (Du − Dr)/Du × 100 expressed as percentage, where Du and Dr are the diameters of unreleased lattice and released lattice after addition of potassium chloride, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means ± se. Statistical analysis was performed by means of Student's t test, ANOVA with Bonferroni correction as needed, or ANOVA followed by Dunnet test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

AFSC differentiation into SMCs

Molecular assessment

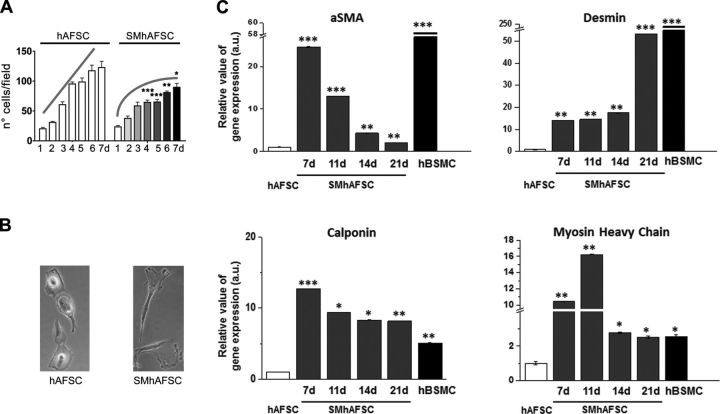

Amniotic fluid stem cells cultured for 7 d in differentiated conditions showed a significant reduced growth rate starting from the fourth day (P<0.001) when compared to AFSCs maintained in control culture conditions (Fig. 1A). The latter did not reach the plateau level during the same time frame despite being more confluent from the fourth day onward. Cells cultured in the same conditions were analyzed by both conventional and quantitative PCR to describe the pattern of expression of some markers typically present in smooth muscle differentiation. Real-time PCR confirmed preliminary results obtained at conventional PCR (data not shown) and allowed their dynamic pattern of expression to be seen; α-SMA, desmin, calponin, and myosin heavy chain 11 transcriptional levels significantly increased during the differentiation process, reaching values that are comparable to those detected in native hBSMCs. However, α-SMA, calponin, and myosin heavy chain 11 expression follows an oscillatory pattern peaking at 7–11 d of differentiation; in particular, α-SMA and desmin at 21 d have expression values lower than those present in native hBSMCs. By contrast, calponin and myosin heavy chain transcripts at 21 d are very similar to those present in native hBSMCs. Notably, all gene expression levels are always significantly higher in differentiated SMhAFSCs than undifferentiated hAFSCs, even after 17–21 d when they were at their lowest level.

Figure 1.

A) Growth rate of hAFSCs and SMhAFSCs cultured for 7 d. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. B) Phase-contrast images of hAFSCs and SMhAFSCs (21 d of differentiation; view ×20) C) mRNA expression of smooth muscle markers (αSMA, desmin, calponin, and myosin heavy chain) analyzed after 7, 11, 14, and 21 d by real-time PCR in hAFSCs, SMhAFSCs, and hBSMCs. Results for each condition are from triplicate experiments, and values are expressed in relative units as the mean. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001.

Ultrastructural assessment

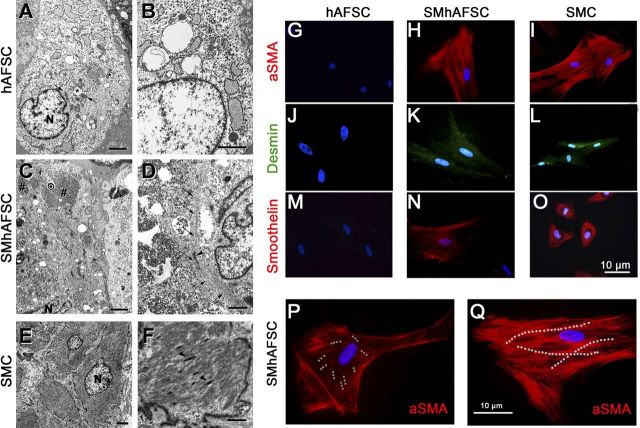

Differentiated and undifferentiated hAFSCs were analyzed in a blinded procedure at d 21 by an independent investigator using electron microscopy (Fig. 2A–F). AFSCs showed an average dimension of 20–25 μm. They contained free polyribosomes and profiles of rough endoplasmic reticulum; a small Golgi apparatus; a few mitochondria, which often appeared swollen; some intermediate filaments; and virtually no glycogen (Fig. 2A, B). SMhAFSCs (Fig. 2C, D) showed more abundant cytoplasm with multiple glycogen depots (Fig. 2E, F) and bundles of thin filaments including dense bodies, as seen in SMCs.

Figure 2.

Left panels: transmission electron microscopy in hAFSCs (A, B), SMhAFSCs (C, D), and SMCs (E, F). N, nucleus. Asterisks (*) indicate swollen mitochondria (A); hashtags (#) indicate glycogen (C); arrows indicate normal mitochondria (A) or thin filaments (D); arrowheads indicate dense bodies (D, F). Scale bars = 2 μm (A, C, E); 1 μm (B, D, F). Right panels: immunofluorescence analysis for α-SMA, desmin, and smoothelin. SMhAFSCs were positive for all 3 smooth muscle markers (H, K, N) compared to SMCs (I, J, O), while hAFSCs were negative (G, J, M). SMhAFSCs contained an increased presence of α-SMA positively stained microfilaments (dotted white lines), respectively, after 7 d (P) and 14 d (Q) of selective culture conditions.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence staining revealed that only SMhAFSCs and not hAFSCs expressed differentiation markers such as α-SMA, desmin, and smoothelin. In particular, smoothelin is a marker uniquely expressed by differentiated SMCs. Indeed, both SMhAFSCs (Fig. 2N) and SMCs (Fig. 2O) appeared positive to the smoothelin. Subsequently, we monitored the expression during differentiation of α-SMA, which localized in the intermediate filaments. At 7 d after inducing differentiation, SMhAFSCs (Fig. 2P) presented α-SMA arranged in the structure of the cell cytoskeleton. However, at this stage most of the cells showed only short bundles of short intermediate filaments, while already at 14 d (Fig. 2Q) most of the cells that underwent smooth muscle differentiation showed an organized α-SMA-positive cytoskeleton, resembling that of the positive control (Fig. 2I). Ectodermal and endodermal lineage commitment was ruled out by the absence of endothelial (CD31) and epithelial (pancytokeratin) markers both in SMhAFSCs (Supplemental Fig. S1B–E), and hAFSCs (Supplemental Fig. S1A–D).

SMhAFSCs have higher oxidative metabolism, and their proliferative ability is determined by specific growth factors

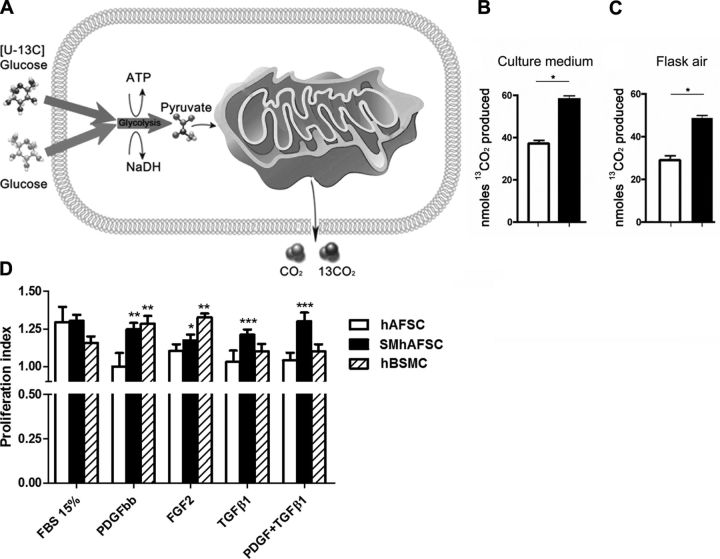

Mitochondrial oxidative metabolism has an important role as the major energy source in SMCs. Therefore, we investigated whether SMhAFSCs display increased oxidative capacity compared with hAFSCs. [U-13C]-d-glucose was used as a substrate; 13C-pyruvate produced by glycolysis is then oxidized in the mitochondria to yield 13CO2 so that 13CO2 is a measure of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. After 4 h incubation with [U-13C]-d-glucose, 13CO2 released in the culture medium and in the sealed culture flasks air was measured. (Fig. 3A). SMhAFSCs showed a higher 13CO2 yield compared to hAFSCs, confirming that the differentiated cells in a steady state possess an enhanced mitochondrial metabolism (Fig. 3B, C) compared with undifferentiated hAFSCs, which predominantly use nonoxidative glycolysis for metabolism. Moreover, when cells were exposed to specific growth factors, SMhAFSC proliferation was increased when compared to hAFSCs. After 24 h starvation from FBS, both cell types were exposed to 1% FBS medium containing growth factors (namely, PDGF-BB, FGF-2, TGF-β1) or to medium containing 15% FBS without factors. While both cell populations responded similarly to FBS stimulation, SMhAFSCs, in comparison to hAFSCs, showed an enhanced proliferative response to FGF-2 (P<0.05), PDGF-BB (P<0.01), comparable to that of hBSMCs, and to TGF- β1 (P<0.001) and PDGF-BB/TGF-β1 (P<0.001) (Fig. 3D). However, when hBSMCs were seeded in low-glucose DMEM and without any growth factor supplemented (standard conditions; ref. 27), the proliferation rate in response to PDGF-BB and to FGF-2 increased (Supplemental Fig. S1M).

Figure 3.

A) Uptake and metabolism of [U-13C]-glucose in hAFSCs and SMhAFSCs. B, C) 13CO2 production present in culture medium (B) and released into the air contained in a sealed culture flask (C). SMhAFSCs demonstrated a higher production of 13CO2 compared to hAFSCs. *P< 0.05. D) Proliferation assay (a.u., arbitrary units) after FBS starvation in hAFSCs, SMhAFSCs, and hBSMCs. All cell populations were seeded on differentiation medium (see Materials and Methods). Proliferation was assessed as total DNA/cells. Similar results were obtained by evaluating cell proliferation by means of total cells/well. Proliferation index is the ratio between the proliferative effect obtained in response to any stimulus and the proliferation of unstimulated control cells (cells grown in medium+1% FBS; proliferation index of 1.0). *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001 vs. control unstimulated cells (ANOVA followed by Dunnet test).

SMhAFSCs have a specific electrophysiological fingerprint similar to SMCs

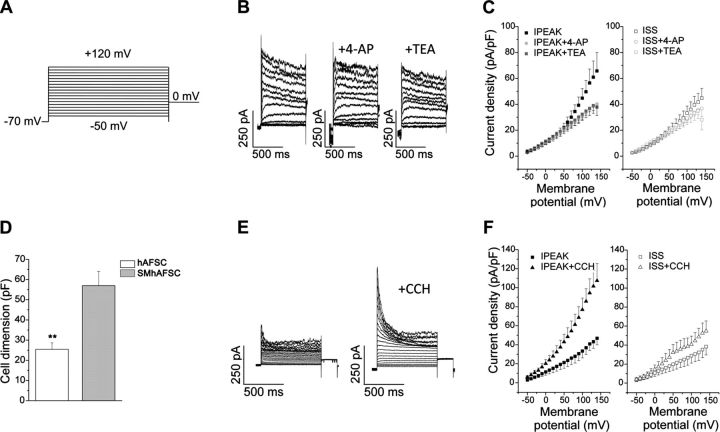

To further prove the possibility of deriving SMCs from AFSCs and to monitor their behavior in vitro, cells were transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding ZsGreen sequence placed under the control of the α-SMA promoter. After transduction, hAFSCs were differentiated for 1 wk and analyzed by FACS. Interestingly, about half of the induced cells expressed ZsGreen fluorescent protein, therefore demonstrating activation of α-SMA promoter and a commitment to smooth muscle lineage in these cells (Supplemental Fig. S1K–M). All the subsequent single-cell analyses were performed using cells expressing the ZsGreen fluorescent protein (ZsGr+) to distinguish the committed cells. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed in ZsGr+ SMhAFSCs differentiated for 19–30 d and in control conditions (hAFSCs). In these two populations, we were able to appreciate a difference in cell membrane capacitance (P<0.01; Fig. 4D,), a measure that is directly proportional to cell surface membrane area, thus indicating that commitment of hAFSCs to smooth muscle lineage is associated with cell hypertrophic growth. Outward currents were evoked by voltage steps ranging from −50 to 120 mV (holding potential −70 mV) in 10-mV increments for a duration of 800 ms, as illustrated in Fig. 4A. A typical recording obtained from a single ZsGrSMhAFSC differentiated for 25 d (Fig. 4B) shows that activated currents displayed two different outward components: a transient, voltage-dependent, and inactivating (peak) component that is followed by a sustained, voltage-dependent, and noninactivating (steady-state) component. Both components coexist in 85% of cells (17 of 20 cells) at this stage of differentiation. The current-voltage relationships plotted as current densities (means± se) vs. step potentials (Fig. 4C) indicate that the two components have different voltage sensitivities. In particular, the transient current was apparent, with step depolarization to potentials more positive than −40 mV, peaking within 150 ms at 0 mV, then declining with persistent depolarization. Both transient and persistent components were sensitive to different blockers, namely, 2 mM TEA and 5 mM 4-AP, leading to the conclusion that the outward currents present in ZsGr+ SMhAFSCs were due to the opening of K+-selective channels (Fig. 4B–C). The sensitivity of transient and persistent currents to both 2 mM TEA and 5 mM 4-AP is consistent with the presence of the delayed rectifier and Ca2+-dependent K+ currents described in native SMCs (35). To verify this similarity, in native hBSMCs we used experimental conditions that were similar to those used in undifferentiated hAFSCs and differentiated SMhAFSCs. In this setting, we detected outward currents (Supplemental Fig. S1I) that share many of the properties present in differentiated SMhAFSCs (Fig. 4). In fact, recordings show the presence of voltage-dependent transient and persistent components (Supplemental Fig. S1I) with density comparable to that found in SMhAFSCs and that are sensitive to TEA and 4-AP.

Figure 4.

Patch-clamp analysis of SMhAFSCs. A, B) Voltage step stimulation protocol (A) employed to elicit outward currents in SMhAFSCs and the response to K+ channel blockers, 5 mM 4-AP and 2 mM TEA (B). C) Current-voltage relationships of peak (IPEAK) and steady-state (ISS) currents before and after application of 4-AP and TEA. *P< 0.05. D) hAFSC and SMhAFSC dimensions, estimated by measurements of cell membrane capacitance. **P< 0.01. E) Outward current traces recorded in SMhAFSCs before and after application of 1 μM carbachol. F) Current-voltage relationships of peak (IPEAK) and steady-state (ISS) currents before and after application of CCH. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01.

Compared with ZsGr+ SMhAFSCs, electrophysiological properties of undifferentiated hAFSCs were much more heterogeneous. In fact, using the same recording conditions, 30% of cells (4 of 12) displayed only a sustained noninactivating outward component that is moderately sensitive to 2mM TEA (Supplemental Fig. S1G). In addition, 60% of cells showed a transient, inactivating component that differed from that present in differentiated cells since it is not sensitive to 4-AP (Supplemental Fig. S1H).

To investigate the response of outward currents to hormonal mediators involved in smooth muscle contraction, we tested the effect of CCH, which is known to activate muscarinic receptors in SMCs and promote contraction. In this process, both chloride and calcium activated K+ currents play an important role via modification of cell membrane potential (36, 37). After exposure to 1 μM CCH, outward currents detectable in differentiated ZsGr+ SMhAFSCs were increased considerably (Fig. 4E); analysis of current-voltage relationship (Fig. 4F) revealed that both transient and sustained components were enhanced by the CCH treatment. A similar effect was observed in 5 different cells differentiated for 20–30 d. Responsiveness to CCH was also tested in native hBSMCs, which increased both currents similarly to the differentiated ZsGr+ SMhAFSCs (Supplemental Fig. S1J). By contrast, the outward current present in undifferentiated cells was not modified by CCH (data not shown).

SMhAFSCs under stimulation display contractile properties

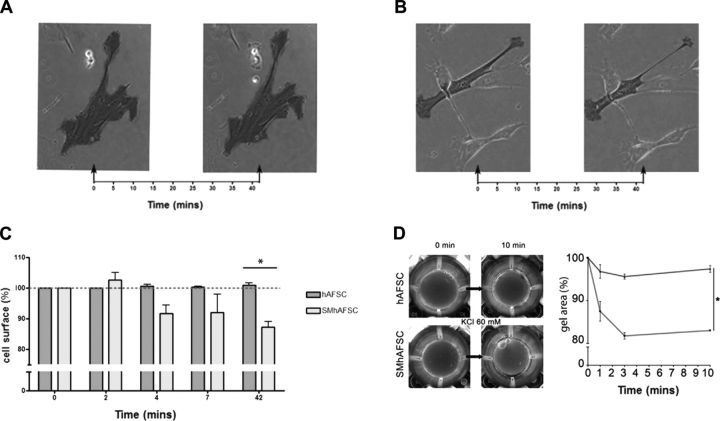

Given the electrophysiological fingerprint retained by SMhAFSCs, we further investigated their functionality. Under time-lapse microscopy, single SMhAFSCs that were tracked for 42 min after stimulation with carbachol 10−4 M showed a remarkable surface area reduction (P=0.0232; Fig. 5A–C and Supplemental Videos S1 and S2). This effect was qualitatively similar to that observed in human native SMCs exposed to CCH (Supplemental Video S3). To confirm macroscopically the data observed in single cells, hAFSCs and SMhAFSCs were seeded on a collagen lattice gel, and contraction of the gel was evaluated. In particular, cells were mixed with a collagen lattice gel and immersed in a KCl solution after solidification (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, while untreated hAFSC gels demonstrated a very modest contraction, gels containing SMhAFSCs showed a strong reduction of gel area (P<0.05). These data strongly support the hypothesis that SMhAFSCs share functional similarities with mature SMCs.

Figure 5.

A, B) Time-lapse analysis under phase-contrast microscopy of a single hAFSC (A) and SMhAFSC (B) before and after 10−4 M carbachol stimulation. C) Cells were compared before and after contractile stimulation in both hAFSCs and SMhAFSCs, as reported in a surface/time chart with surface expressed as percentage of the initial cell surface. D) In a collagen lattice gel assay, macroscopic contractile activity was evaluated in both hAFSCs and SMhAFSCs after KCl (60 mM) stimulation. Gel with SMhAFSCs (gray line) had a significant reduction of gel area compared to hAFSCs (black line). Assay was performed in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

Generation of functional smooth muscle tissue for clinical application requires the isolation and expansion of large numbers of SMCs that maintain functional properties. This is particularly challenging for visceral smooth muscle tissue where progenitor cells have not been identified. SMCs form a very heterogeneous population both at the morphological and physiological levels that retains some common features, such as a spindle shape, low proliferative rate, reduced synthesis of extracellular matrix, and ligand-induced contractility (38, 39). So far, to obtain smooth muscle differentiation, alternatively both embryonic and adult stem cells have been explored. Herein we showed for the first time that functional SMCs could be obtained from hAFSCs. While ESCs or iPSCs have the limitation of being difficult to program and could lead to tumor formation in vivo, and adult stem cells are difficult to expand in vitro, AFSCs can give rise to cell lineages inclusive of the 3 embryonic germ layers but do not generate teratoma (23). For our experiments, we focused on human AFS cells, which make up ∼1% of the total cell population cultured from amniocentesis specimens routinely obtained for prenatal genetic diagnosis and that typically express c-kit (CD117) as a marker of differentiation (23). In our study, SMCs were generated from hAFSCs, and, using a combined functional analysis approach, we tested their molecular, electrophysiological, and metabolic properties. Therefore, while AFS cells appeared to be less plastic than ESCs, the present study demonstrates that a population of adherent cells obtained from amniotic fluid can differentiate into SMCs. SMCs were previously obtained from both embryonic and adult stem cells using various combinations of cytokines and growth factors, such as TGF-β1 alone, TGF-β1 plus PDGF-BB, TGF-β1 plus aminoacids, sphingosylphosphorylcholine plus TGF-β1, and TGF-β1 plus HGF (40–43). In addition, it has been recently reported (44) that the differentiation of stem cells toward the smooth muscle lineage relies mostly on the activation of specific intracellular pathways, such as Notch signaling, initiated by the interaction of TGF-β with its receptor. Similarly, we have observed that using a medium containing both TGF-β1 and PDGF-BB (22), hAFSCs activated intracellular mechanisms, which ultimately enhanced the transcription of specific smooth muscle proteins. Notably, we have observed that induced cells acquired typical SMC morphology and homogenously expressed markers of differentiation, whereas hAFSCs maintained in control conditions never underwent spontaneous differentiation. This is particularly evident when markers indicative of mature myogenesis, such as desmin, calponin, and smoothelin, were considered (38, 45, 46). In parallel with ongoing differentiation, we observed a reduced proliferation rate (47) and an enlargement of cells associated with glycogen deposition and formation of bundles of thin filaments including dense bodies. It is indeed the sequential expression of cytoskeletal and contractile proteins associated with coherent morphological changes that generates the diversity of phenotypes, ranging from immature cells to mature SMCs expressing the complete repertoire of proteins involved in smooth muscle contraction (47). Thus, to characterize leiomyogenic differentiation, we chose to evaluate not only α-SMA expression, but also the expression of all other smooth muscle markers. These other markers are highly restricted to differentiated smooth muscle, and, in particular, MHC and smoothelin are not detected in any other cell type and are expressed only in contractile SMCs (48). hAFSCs cultured in any of these conditions were shown to be homogenously positive for α-SMA, calponin, desmin, and smoothelin but negative for CD31 and pancytokeratin (Supplemental Fig. S1A–F), a hallmark of endodermal and ectodermal differentiation. Changes in cellular structure were accompanied both with enhanced mitochondrial oxidation, as shown here for the first time (Fig. 3), and acquired response to proliferation to mitogenic stimuli, as reported for SMCs (34). It was, however, difficult to distinguish in culture cells that undergo smooth muscle differentiation; therefore, evaluation of commitment implies either sacrifice of the culture or extrapolation of clonal analysis to cell population phenomena. To overcome those limitations, we used a lentiviral vector encoding a reporter gene (ZsGreen sequence) placed under the control of the α-SMA promoter (29). In this system, the SMA promoter is specific to the SMC lineage and therefore provides a reliable way to obtain a pure population of functional SMCs from a heterogeneous population of stem cells, as previously demonstrated (29, 49–51). In these conditions, we were able to monitor single cells within the induced populations. This not only allowed us to follow SMhAFSCs during culture, demonstrating that more than half of SMhAFSCs did actually commit to a myogenic program, but, more notably, we could further analyze those cells at the functional level. SMCs are highly specialized cells whose principal functions are contraction and relaxation, and previously induced bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) were able to acquire a similar electrophysiological profile to SMCs. In vitro differentiation of BMSCs (52, 53) induced an enhancement of the IKCa current, but, despite specific SM protein expression and modification of electrophysiological properties, bona fide differentiated MSCs failed to display contractile properties. These results have underscored the necessity to find the ideal culture conditions to induce a complete developed SMC functionality (52, 53). We demonstrated here that only SMhAFSCs presented functional properties of mature SMCs with characteristics resembling human SMCs. Indeed, sensitivity of transient and persistent outward currents to both 2 mM TEA and 5 mM 4-AP is consistent with the presence of the delayed rectifier and Ca2+-dependent K+ currents described in native SMCs, which have a visceral localization (35). Notably, we provided evidence that outward currents in SMhAFSCs are enhanced by CCH, suggesting that cholinergic signaling, a key regulator of SMC physiology (36), is effective in differentiated cells. Functional analysis can indeed be complicated in SMCs because of their heterogeneity and plasticity and by the fact that SM cells originate from multiple precursors throughout the embryo (54). During development, in fact, smooth muscle progenitors arise mainly from the splanchnic mesoderm and from the neural crest (47). At postnatal life, vascular SMC progenitors have been found in circulating blood (55) and bone marrow (56). Indeed, we observed that electrophysiological stimuli transduced to contraction phenomena, which were evident when time-lapse videos were acquired in a blinded procedure. The ability of SMCs to contract in response to a physiological stimulus has been considered to be the main proof of functional myogenic differentiation (refs. 57, 58; videos in Supplemental Data show hAFSCs vs. SMhAFSCs in carbachol stimulation), and indeed significant cellular contractions were observed when SMhAFSCs were exposed to CCH. Notably, those cellular events led to macroscopic contraction of collagen gels seeded with SMhAFSCs, similarly to what has been reported with induced adipose-derived stem cells (16).

The use of stem cells differentiated toward SM phenotype in this context may provide an alternative treatment for diseases involving hollow organs or sphincters, such as occurs (among others) in cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal diseases, urinary incontinence, and bladder dysfunction, overcoming some of the hurdles posed by the limited expansion of differentiated SMCs (59). Clonal hAFSCs have been proven to retain long telomeres both in early and late passages (>250 population doublings; ref. 23). This feature could favor their use for tissue engineering in view of their proliferative ability and their ability to generate functional SMCs. Employment of AFSCs in the pediatric field, compared to other stem cell types, bears the potential advantage to generate an autologous tissue that might represent an optimal choice for some prenatally diagnosed structural defects (24). Those defects today still require the use of either prosthetic materials or transposition and substitution of different functional tissue in order to be corrected. In particular, smooth muscle tissue defects that are present in commonly prenatally diagnosed malformations, such as long-gap esophageal atresia and bladder exstrophy, could be repaired using induced AFSCs. Further studies in vivo are necessary to verify whether induced cells are capable of retaining functional properties acquired in vitro. Seeding strategies using appropriate polymers will be needed to test hollow organ generation.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Bertrand Vernay for assistance with time lapse microscopy, Ayad Eddaoudi for his valuable help in cell sorting, Dr. Sara Paccosi and Dr. Claudia Musilli for their support with cell cultures, and Dr. Pedro Lei and Dr. Waseem Qasim for their support with transduction.

This work has been supported by Fondazione Cittá della Speranza, Fondazione Meyer Firenze, Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Universitá e delle Ricerca (Rome, Italy; PRIN 2010-11), and the Great Osmond Street Hospital (GOSH) Charity (London, UK). P.D.C. is supported by the GOSH Charity. A.L.D. is supported at University College London/ University College London Hospitals by funding from the UK Department of Health National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre's funding scheme.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- 4-AP

- 4-aminopyridine

- α-SMA

- α smooth muscle actin

- AFSC

- amniotic fluid stem cell

- BMSC

- bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell

- CCH

- carbachol

- ESC

- embryonic stem cell

- FACS

- fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- hAFSC

- human amniotic fluid stem cell

- hBSMC

- human bladder smooth muscle cell

- iPSC

- induced pluripotent stem cell

- IRES

- internal ribosome entry site

- MCS

- multiple cloning site

- MSC

- mesenchymal stem cell

- P-α-SMA

- α smooth muscle actin promoter

- PCR

- polymerase chain reaction

- PDGF-BB

- platelet-derived growth factor BB

- SMA

- smooth muscle actin

- SMC

- smooth muscle cell

- SMhAFSC

- smooth muscle human amniotic fluid stem cell

- TEA

- tetraethylammonium

- TGF-β1

- transforming growth factor β1

- ZsGreen

- Zoanthus sp. green fluorescent protein

REFERENCES

- 1.Nakase Y., Nakamura T., Kin S., Nakashima S., Yoshikawa T., Kuriu Y., Sakakura C., Yamagishi H., Hamuro J., Ikada Y., Otsuji E., Hagiwara A. (2008) Intrathoracic esophageal replacement by in situ tissue-engineered esophagus. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. , 850–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sala F. G., Kunisaki S. M., Ochoa E. R., Vacanti J., Grikscheit T. C. (2009) Tissue-engineered small intestine and stomach form from autologous tissue in a preclinical large animal model. J. Surg. Res. , 205–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atala A., Bauer S. B., Soker S., Yoo J. J., Retik A. B. (2006) Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients needing cystoplasty. Lancet , 1241–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badylak S. F., Weiss D. J., Caplan A., Macchiarini P. (2012) Engineered whole organs and complex tissues. Lancet , 943–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huber A., Badylak S. F. (2011) Phenotypic changes in cultured smooth muscle cells: limitation or opportunity for tissue engineering of hollow organs? J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. , 505–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beamish J. A., He P., Kottke-Marchant K., Marchant R. E. (2010) Molecular regulation of contractile smooth muscle cell phenotype: implications for vascular tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. B Rev. , 467–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aikawa M., Sakomura Y., Ueda M., Kimura K., Manabe I., Ishiwata S., Komiyama N., Yamaguchi H., Yazaki Y., Nagai R. (1997) Redifferentiation of smooth muscle cells after coronary angioplasty determined via myosin heavy chain expression. Circulation , 82–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thyberg J., Blomgren K., Hedin U., Dryjski M. (1995) Phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells during the formation of neointimal thickenings in the rat carotid artery after balloon injury: an electron-microscopic and stereological study. Cell Tissue Res. , 421–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majesky M. W., Dong X. R., Regan J. N., Hoglund V. J. (2011) Vascular smooth muscle progenitor cells: building and repairing blood vessels. Circ. Res. , 365–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright W. E., Shay J. W. (2000) Telomere dynamics in cancer progression and prevention: fundamental differences in human and mouse telomere biology. Nat. Med. , 849–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merkulova-Rainon T., Broqueres-You D., Kubis N., Silvestre J. S., Levy B. I. (2012) Towards the therapeutic use of vascular smooth muscle progenitor cells. Cardiovasc. Res. , 205–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabella G. (2002) Development of visceral smooth muscle. Results Probl. Cell Differ. , 1–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang H., Zhao X., Chen L., Xu C., Yao X., Lu Y., Dai L., Zhang M. (2006) Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into smooth muscle cells in adherent monolayer culture. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. , 321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie C. Q., Zhang J., Villacorta L., Cui T., Huang H., Chen Y. E. (2007) A highly efficient method to differentiate smooth muscle cells from human embryonic stem cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. , e311–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinha S., Wamhoff B. R., Hoofnagle M. H., Thomas J., Neppl R. L., Deering T., Helmke B. P., Bowles D. K., Somlyo A. V., Owens G. K. (2006) Assessment of contractility of purified smooth muscle cells derived from embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells , 1678–1688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez L. V., Alfonso Z., Zhang R., Leung J., Wu B., Ignarro L. J. (2006) Clonogenic multipotent stem cells in human adipose tissue differentiate into functional smooth muscle cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. , 12167–12172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang C., Yin S., Cen L., Liu Q., Liu W., Cao Y., Cui L.. Differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells into contractile smooth muscle cells induced by transforming growth factor-beta1 and bone morphogenetic protein-4. Tissue Eng. A , 1201–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie C. Q., Huang H., Wei S., Song L. S., Zhang J., Ritchie R. P., Chen L., Zhang M., Chen Y. E. (2009) A comparison of murine smooth muscle cells generated from embryonic versus induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. , 741–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang A., Tang Z., Li X., Jiang Y., Tsou D. A., Li S. (2012) Derivation of smooth muscle cells with neural crest origin from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cells Tissues Organs , 5–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirschi K. K., Rohovsky S. A., D'Amore P. A. (1998) PDGF, TGF-beta, and heterotypic cell-cell interactions mediate endothelial cell-induced recruitment of 10T1/2 cells and their differentiation to a smooth muscle fate. J. Cell Biol. , 805–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinha S., Hoofnagle M. H., Kingston P. A., McCanna M. E., Owens G. K. (2004) Transforming growth factor-beta1 signaling contributes to development of smooth muscle cells from embryonic stem cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. , C1560–C1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian H., Bharadwaj S., Liu Y., Ma H., Ma P. X., Atala A., Zhang Y. (2009) Myogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells on a 3D nano fibrous scaffold for bladder tissue engineering. Biomaterials , 870–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Coppi P., Bartsch G., Siddiqui M. M., Xu T., Santos C. C., Perin L., Mostoslavsky G., Serre A. C., Snyder E. Y., Yoo J. J., Furth M. E., Soker S., Atala A. (2007) Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. , 100–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pozzobon M., Ghionzoli M., De Coppi P. (2009) ES, iPS, MSC, and AFS cells. Stem cells exploitation for pediatric surgery: current research and perspective. Pediatr. Surg. Int. , 3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bollini S., Cheung K. K., Riegler J., Dong X., Smart N., Ghionzoli M., Loukogeorgakis S. P., Maghsoudlou P., Dube K. N., Riley P. R., Lythgoe M. F., De Coppi P. (2011) Amniotic fluid stem cells are cardioprotective following acute myocardial infarction. Stem Cells Dev. , 1985–1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Coppi P., Callegari A., Chiavegato A., Gasparotto L., Piccoli M., Taiani J., Pozzobon M., Boldrin L., Okabe M., Cozzi E., Atala A., Gamba P., Sartore S. (2007) Amniotic fluid and bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells can be converted to smooth muscle cells in the cryo-injured rat bladder and prevent compensatory hypertrophy of surviving smooth muscle cells. J. Urol. , 369–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crescioli C., Morelli A., Adorini L., Ferruzzi P., Luconi M., Vannelli G. B., Marini M., Gelmini S., Fibbi B., Donati S., Villari D., Forti G., Colli E., Andersson K. E., Maggi M. (2005) Human bladder as a novel target for vitamin D receptor ligands. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. , 962–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delafosse B., Viale J. P., Tissot S., Normand S., Pachiaudi C., Goudable J., Bouffard Y., Annat G., Bertrand O. (1994) Effects of glucose-to-lipid ratio and type of lipid on substrate oxidation rate in patients. Am. J. Physiol. , E775–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J. Y., Peng H. F., Andreadis S. T. (2008) Contractile smooth muscle cells derived from hair-follicle stem cells. Cardiovasc. Res. , 24–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sartiani L., Bettiol E., Stillitano F., Mugelli A., Cerbai E., Jaconi M. E. (2007) Developmental changes in cardiomyocytes differentiated from human embryonic stem cells: a molecular and electrophysiological approach. Stem Cells , 1136–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mistry D. K., Garland C. J. (1998) Nitric oxide (NO)-induced activation of large conductance Ca2+-dependent K+ channels (BK(Ca)) in smooth muscle cells isolated from the rat mesenteric artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. , 1131–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huet E., Vallee B., Szul D., Verrecchia F., Mourah S., Jester J. V., Hoang-Xuan T., Menashi S., Gabison E. E. (2008) Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer/CD147 promotes myofibroblast differentiation by inducing alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and collagen gel contraction: implications in tissue remodeling. FASEB J. , 1144–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ehrlich H. P., Allison G. M., Page M. J., Kolton W. A., Graham M. (2000) Increased gelsolin expression and retarded collagen lattice contraction with smooth muscle cells from Crohn's diseased intestine. J. Cell. Physiol. , 303–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin H. K., Cowan R., Moore P., Zhang Y., Yang Q., Peterson J. A., Tomasek J. J., Kropp B. P., Cheng E. Y. (2004) Characterization of neuropathic bladder smooth muscle cells in culture. J. Urol. , 1348–1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wade G. R., Laurier L. G., Preiksaitis H. G., Sims S. M. (1999) Delayed rectifier and Ca(2+)-dependent K(+) currents in human esophagus: roles in regulating muscle contraction. Am. J. Physiol. , G885–G895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Q., Akbarali H. I., Hatakeyama N., Goyal R. K. (1996) Caffeine- and carbachol-induced Cl- and cation currents in single opossum esophageal circular muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. , C1725–C1734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teramoto N. (2006) Physiological roles of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in smooth muscle. J. Physiol. , 617–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Small J. V., Gimona M. (1998) The cytoskeleton of the vertebrate smooth muscle cell. Acta Physiol. Scand. , 341–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Y., Relan N. K., Przywara D. A., Schuger L. (1999) Embryonic mesenchymal cells share the potential for smooth muscle differentiation: myogenesis is controlled by the cell's shape. Development , 3027–3033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeon E. S., Moon H. J., Lee M. J., Song H. Y., Kim Y. M., Bae Y. C., Jung J. S., Kim J. H. (2006) Sphingosylphosphorylcholine induces differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells into smooth-muscle-like cells through a TGF-beta-dependent mechanism. J. Cell Sci. , 4994–5005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Narita Y., Yamawaki A., Kagami H., Ueda M., Ueda Y. (2008) Effects of transforming growth factor-beta 1 and ascorbic acid on differentiation of human bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells into smooth muscle cell lineage. Cell Tissue Res. , 449–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao Q., Zeng L., Zhang Z., Hu Y., Xu Q. (2007) Stem cell-derived Sca-1+ progenitors differentiate into smooth muscle cells, which is mediated by collagen IV-integrin alpha1/beta1/alphav and PDGF receptor pathways. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. , C342–C352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kanematsu A., Yamamoto S., Iwai-Kanai E., Kanatani I., Imamura M., Adam R. M., Tabata Y., Ogawa O. (2005) Induction of smooth muscle cell-like phenotype in marrow-derived cells among regenerating urinary bladder smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Pathol. , 565–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kurpinski K., Lam H., Chu J., Wang A., Kim A., Tsay E., Agrawal S., Schaffer D. V., Li S. (2010) Transforming growth factor-beta and notch signaling mediate stem cell differentiation into smooth muscle cells. Stem Cells , 734–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coco D. P., Hirsch M. S., Hornick J. L. (2009) Smoothelin is a specific marker for smooth muscle neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. , 1795–1801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Eys G. J., Niessen P. M., Rensen S. S. (2007) Smoothelin in vascular smooth muscle cells. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. , 26–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miano J. M. (2002) Mammalian smooth muscle differentiation: origins, markers and transcriptional control. Results Probl. Cell Differ. , 39–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van der Loop F. T., Schaart G., Timmer E. D., Ramaekers F. C., van Eys G. J. (1996) Smoothelin, a novel cytoskeletal protein specific for smooth muscle cells. J. Cell Biol. , 401–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peng H. F., Liu J. Y., Andreadis S. T., Swartz D. D. (2011) Hair follicle-derived smooth muscle cells and small intestinal submucosa for engineering mechanically robust and vasoreactive vascular media. Tissue Eng. A , 981–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu J. Y., Peng H. F., Gopinath S., Tian J., Andreadis S. T. (2010) Derivation of functional smooth muscle cells from multipotent human hair follicle mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng. A , 2553–2564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu J. Y., Swartz D. D., Peng H. F., Gugino S. F., Russell J. A., Andreadis S. T. (2007) Functional tissue-engineered blood vessels from bone marrow progenitor cells. Cardiovasc. Res. , 618–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bonnet P., Awede B., Rochefort G. Y., Mirza A., Lermusiaux P., Domenech J., Eder V. (2008) Electrophysiological maturation of rat mesenchymal stem cells after induction of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in vitro. Stem Cells Dev. , 1131–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Snetkov V. A., Pandya H., Hirst S. J., Ward J. P. (1998) Potassium channels in human fetal airway smooth muscle cells. Pediatr. Res. , 548–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Majesky M. W. (2007) Developmental basis of vascular smooth muscle diversity. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. , 1248–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simper D., Stalboerger P. G., Panetta C. J., Wang S., Caplice N. M. (2002) Smooth muscle progenitor cells in human blood. Circulation , 1199–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kashiwakura Y., Katoh Y., Tamayose K., Konishi H., Takaya N., Yuhara S., Yamada M., Sugimoto K., Daida H. (2003) Isolation of bone marrow stromal cell-derived smooth muscle cells by a human SM22alpha promoter: in vitro differentiation of putative smooth muscle progenitor cells of bone marrow. Circulation , 2078–2081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kinner B., Zaleskas J. M., Spector M. (2002) Regulation of smooth muscle actin expression and contraction in adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Cell Res. , 72–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oishi K., Ogawa Y., Gamoh S., Uchida M. K. (2002) Contractile responses of smooth muscle cells differentiated from rat neural stem cells. J. Physiol. , 139–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hayflick L., Moorhead P. S. (1961) The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. , 585–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.