Flagellates belonging to the genus Leishmania are important human parasites. Some strains of different Leishmania species harbor viruses (leishmaniaviruses), which facilitate metastatic spread of the parasites, thus aggravating the disease. Up until now, these viruses were known to be hosted only by Leishmania. Here, we analyzed viral distribution in Blechomonas, a related group of flagellates parasitizing fleas, and revealed that they also bear leishmaniaviruses. Our findings shed light on the entangled evolution of these viruses. In addition, we documented that Blechomonas can be also infected by leishbunyaviruses and narnaviruses, viral groups known from other insects’ flagellates.

KEYWORDS: Blechomonas, Leishbunyaviridae, Leishmaniavirus, Narnaviridae

ABSTRACT

In this work, we analyzed viral prevalence in trypanosomatid parasites (Blechomonas spp.) infecting Siphonaptera and discovered nine species of viruses from three different groups (leishbunyaviruses, narnaviruses, and leishmaniaviruses). Most of the flagellate isolates bore two or three viral types (mixed infections). Although no new viral groups were documented in Blechomonas spp., our findings are important for the comprehension of viral evolution. The discovery of bunyaviruses in blechomonads was anticipated, since these viruses have envelopes facilitating their interspecific transmission and have already been found in various trypanosomatids and metatranscriptomes with trypanosomatid signatures. In this work, we also provided evidence that even representatives of the family Narnaviridae are capable of host switching and evidently have accomplished switches multiple times in the course of their evolution. The most unexpected finding was the presence of leishmaniaviruses, a group previously solely confined to the human pathogens Leishmania spp. From phylogenetic inferences and analyses of the life cycles of Leishmania and Blechomonas, we concluded that a common ancestor of leishmaniaviruses most likely infected Leishmania first and was acquired by Blechomonas by horizontal transfer. Our findings demonstrate that evolution of leishmaniaviruses is more complex than previously thought and includes occasional host switching.

INTRODUCTION

Trypanosomatidae are a diverse family of flagellates primarily parasitizing insects (1). The vast majority of known trypanosomatids are monoxenous, i.e., restricted to a single (mainly insect) host. However, at least three lineages independently acquired the ability to infect other hosts, such as plants (Phytomonas spp.) and vertebrates (Trypanosoma spp. and a group that unites Leishmania, Paraleishmania, and Endotrypanum), using insects as vectors (2–5). Because of their medical or economic importance, dixenous species were studied in minute detail, while their monoxenous relatives remained mostly neglected (1, 6). One of such usually disregarded groups—genus Blechomonas (subfamily Blechomonadinae)—comprises flagellate parasites of fleas (7). In many phylogenetic reconstructions, this clade is a sister to all other trypanosomatids excluding Trypanosomatinae (Trypanosoma spp.) and Paratrypanosomatinae (Paratrypanosoma spp.) (8–11). Such a position implies an early origin of this group. Nevertheless, since the genus description in 2013, very little attention has been paid to its members, although the genome of the type species, Blechomonas ayalai, has been sequenced and included in some recent phylogenomic analyses (12, 13).

The importance of dixenous parasites determined their priority in the studies of viruses of trypanosomatids (14, 15). The first-ever characterized virus in these flagellates was Leishmania RNA virus 1 (LRV1) (16). This is a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) virus of the family Totiviridae found in the New World Leishmania guyanensis (17). LRV1 impedes the immune response against Leishmania and facilitates metastatic spread of the parasites (18, 19). A related Leishmania RNA virus 2 (LRV2) was shown to infect Leishmania major, Leishmania aethiopica, and Leishmania infantum in the Old World (20, 21). It was proposed that Leishmania spp. and LRV1/2 have coevolved for a long time (20, 22).

A recent large-scale survey of RNA viruses in trypanosomatids revealed the presence of four other viral groups, confirming some previous unsystematic reports (23–25). These groups are the tombus-like viruses {positive single-stranded RNA [(+)ssRNA] genome, proposed taxon}, leishbunyaviruses (LBVs) [(−)ssRNA genome, proposed taxon], narnaviruses (NVs) [(+)ssRNA or dsRNA genomes, formally recognized family], and an unusual ostravirus (26). Interestingly, no relatives of leishmaniaviruses have been found in the analyzed flagellates, leading to a speculation that LRV1/2 were acquired by an ancestor of modern Leishmania and subsequently lost in most extant species. This conclusion was mainly based on the analysis of viral presence in the monoxenous species of the genera Crithidia and Leptomonas, close phylogenetic relatives of the dixenous Leishmania, Paraleishmania, and Endotrypanum (27). However, many groups of Trypanosomatidae were not included in the screening, rendering this interpretation preliminary.

In this work, we investigated the diversity of viruses in flea-infecting trypanosomatids of the genus Blechomonas and report the presence of three different types of viruses in these flagellates, including those related to the prototypical leishmaniaviruses of the family Totiviridae.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Screening and sequencing.

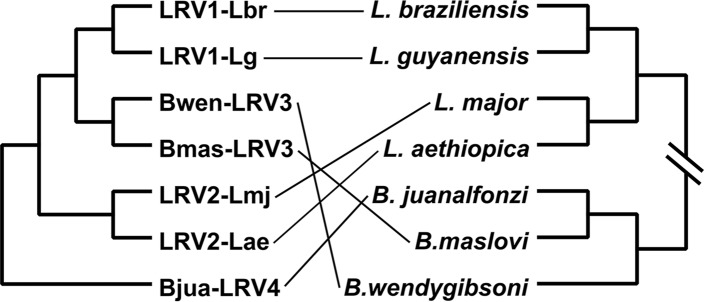

Twelve isolates of Blechomonas spp. used in this analysis were described in considerable detail previously (7). The additional strain of Blechomonas luni (B09-1006) available in our collection was isolated from the flea Chaetopsylla globiceps, collected on the red fox Vulpes vulpes in the Czech Republic in 2009 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). In five isolates (Blechomonas luni B09-1006, B. ayalai B08-376, Blechomonas juanalfonzi B07-161, Blechomonas maslovi B05-J13, and Blechomonas wendygibsoni B09-1267), we documented the presence of the dsRNA bands (Fig. 1). These samples were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq platform, each yielding 2.4 Gbp of sequence data on average. Sequence analyses revealed that these five isolates contain, in total, nine new viruses from three distinct viral groups (Table 1). Importantly, these groups comprise viruses with (+)ssRNA, (−)ssRNA, and dsRNA genomes, allowing sensitive detection of either their genomes or respective replicative intermediates (in the case of ssRNA). Viral genomic RNA sequences were mostly complete, except for the M segments of B. luni LBV1 (BlunLBV1) and B. maslovi LBV1 (BmasLBV1), and the narnavirus BmasNV1, which were incomplete at their 3′ ends. Here, viruses are named according to the established convention indicating an abbreviated host name and viral affiliation (LBV, LRV, or NV for leishbunyaviruses, leishmaniaviruses, and narnaviruses, respectively). Coinfections with more than one virus were documented for three out of five analyzed isolates (Table 1).

FIG 1.

RNA viruses of Blechomonas spp.: Blechomonas keelingi B100, B. luni B08-658, B. pulexsimulantis ATCC 50186, B. lauriereadi B08-604, B. luni B09-1006, B. ayalai B08-376, B. juanalfonzi B07-161, B. danrayi B08-780, B. campbelli B06-BK, B. wendygibsoni B09-1267, and B. maslovi B05-J13. M, GeneRuler 1-kb DNA ladder. Indicated sizes are in kilobases. The shortest dsRNA fragment from B. maslovi B05-J13 (∼470 bp) returned no identifiable BLAST hits.

TABLE 1.

Virus-positive Blechomonas spp.a

| Host strain | Host and viral RNA | Length (nt) | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| B. luni B09-1006 | BlunLBV1 L segment | 5,974 | MG967334 |

| BlunLBV1 M segment | 1,059 | MG967335 | |

| BlunLBV1 S segment | 618 | MG967336 | |

| BlunNV1 | 2,747 | MG967337 | |

| B. ayalai B08-376 | BayaLBV1 L segment | 6,009 | MG967338 |

| BayaLBV1 M segment | 822 | MG967339 | |

| BayaLBV1 S segment | 646 | MG967340 | |

| B. juanalfonzi B07-161 | BjuaLRV4 | 5,429 | MG967341 |

| B. maslovi B05-J13 | BmasLBV1 L segment | 6,251 | MG967342 |

| BmasLBV1 M segment | 1,411 | MG967343 | |

| BmasLBV1 S segment | 706 | MG967344 | |

| BmasLRV3 | 5,412 | MG967345 | |

| BmasNV1 | 2,945 | MG967346 | |

| B. wendygibsoni B09-1267 | BwenLRV3 | 5,403 | MG967347 |

| BwenNV1 | 2,748 | MG967348 |

Species, isolate names, and GenBank accession numbers of the identified viral sequences are indicated. LBV, Leishbunyavirus; LRV, Leishmaniavirus; NV, Narnavirus.

Blechomonas species isolates used in this work. Species, isolate names, GenBank accession numbers for the gGAPDH and 18S rRNA genes, and host specificity are indicated. Download Table S1, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (14KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2018 Grybchuk et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

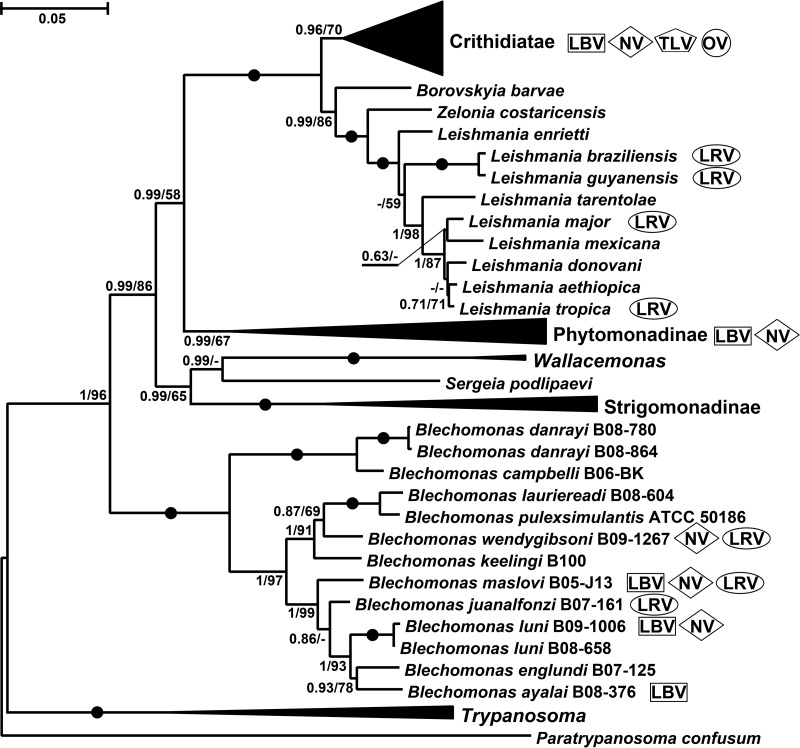

No association between occurrence of the viruses and the species of flagellates or their primary/secondary hosts was apparent from the data (Table 1; Fig. 2). Moreover, the very closely related isolates B. luni B09-1006 and B08-658 turned out to be virus positive and virus negative, respectively. As noted previously, caution should be exercised when interpreting results of viral presence or absence (26). If the viral load is (very) low, a sample that is in fact a virus-positive sample may appear virus negative.

FIG 2.

Viruses of Trypanosomatidae. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of trypanosomatids reconstructed using 18S rRNA and gGAPDH genes (78 operational taxonomic units [OTUs]). Viral groups infecting these flagellates are indicated on the right (see key at top). Numbers at nodes indicate bootstrap percentage/posterior probability. Filled circles mark branches with maximal statistical supports. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site.

LBVs.

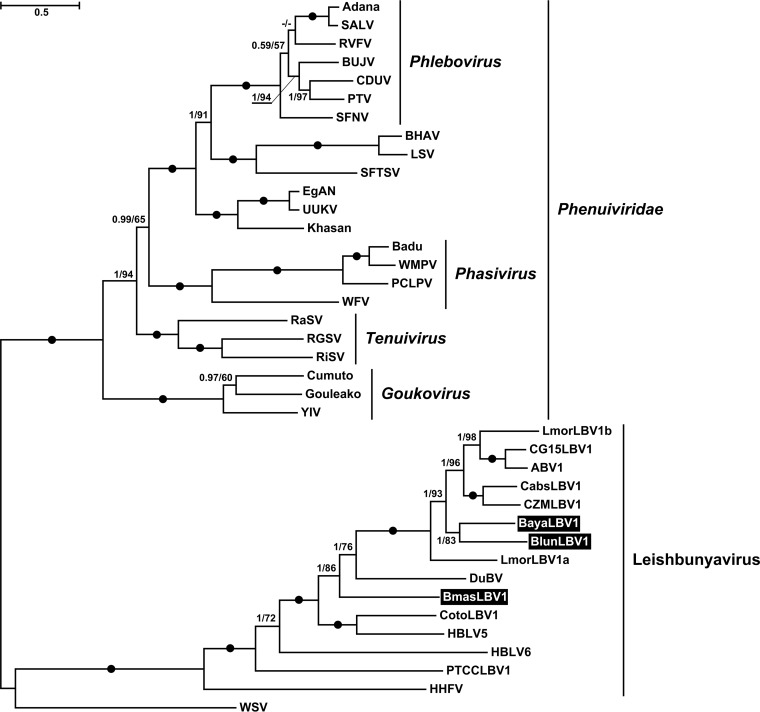

Trypanosomatids are frequently infected with leishbunyaviruses (LBVs) belonging to the recently proposed family Leishbunyaviridae of the order Bunyavirales (26). In this work, we identified three LBVs infecting different Blechomonas spp.—B. luni B09-1006, B. ayalai B08-376, and B. maslovi B05-J13 (Table 1; Fig. 1). All these viruses shared a characteristic tripartite genome arrangement. Their RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDRP), nucleocapsid protein, and terminal panhandle sequences were homologous to those of LBVs of Leishmaniinae. The lengths of the M segments, as well as the amino acid sequences of the putative glycoproteins which they encode, were variable. Analysis with transmembrane domain prediction software (TMHMM, TMPred, and Phobius) revealed the presence of at least two transmembrane helices in all putative glycoproteins. Moreover, we have also predicted the N-terminal signal peptide for membrane insertion and N-glycosylation sites using several approaches (SignalP, Signal-BLAST, and Phobius) (Table S2). A similar arrangement of the Leishmaniinae LBV putative glycoproteins had been reported earlier (26). The LBVs of Blechomonas (B. ayalai LBV1 [BayaLBV1], BlunLBV1, and BmasLBV1) were firmly nested within the proposed Leishbunyaviridae, although they did not form a single lineage, suggesting at least two independent horizontal transfers, most likely from unrelated trypanosomatids (Fig. 3). At the same time, BayaLBV1 and BlunLBV1 constitute sister taxa in the obtained tree, and given that their hosts are more closely related to each other than to that of BmasLBV1 (Fig. 2), we believe that it may be an example of virus-flagellate coevolution. The modest number of analyzed isolates does not allow us to generalize this conclusion.

FIG 3.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of proposed Leishbunyaviridae based on RDRP amino acid sequences. Numbers at the branches indicate Bayesian posterior probability and maximum likelihood bootstrap supports, respectively; those having a Bayesian posterior probability value of 1.0 and maximum likelihood bootstrap support of 100% are marked with black circles. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The tree was rooted with the sequences of Phenuiviridae. Abbreviations and GenBank accession numbers are provided in Table S3.

Transmembrane domains and signal peptides for Blechomonas LBV putative glycoproteins. Download Table S2, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (14KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2018 Grybchuk et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Abbreviations and GenBank accession numbers used for phylogenetic inferences. Download Table S3, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (17.1KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2018 Grybchuk et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Narnaviruses.

Narnaviruses are capsidless viruses containing a single RDRP-encoding transcript (28–30). Originally, they were found in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae but later were also detected in oomycetes (31) and trypanosomatids (23, 24, 26, 32).

We documented narnaviruses in three trypanosomatid isolates—B. luni B09-1006, B. maslovi B05-J13, and B. wendygibsoni B09-1267 (Fig. 1; Table 1). Interestingly, in the first two cases the corresponding dsRNA bands could not be detected using the DNase I-LiCl method (data not shown), whereas an S1 nuclease-based approach allowed their visualization on the gel (Fig. 1). All three viral RNAs were ∼3.0 kb long and contained a single open reading frame (ORF) encoding RDRP as well as two to three stem-loop structures on both the 5′ and 3′ ends (Fig. S1). In narnaviruses from yeasts, these structures are essential for viral replication and defense against exonucleases of the host (30). It is worth noting that the short terminal complementary sequences in narnaviruses of Blechomonas spp. (5′-CCCG…CGGG-3′) differ from the homologous regions in narnaviruses of S. cerevisiae (5′-GGGGGC…GCCCC-3′ [33]).

Secondary structures and complementary sequences on 5′ and 3′ ends of Blechomonas NVs predicted by IPknot. The short terminal complementary sequences are highlighted. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 0.4 MB (397.5KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2018 Grybchuk et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

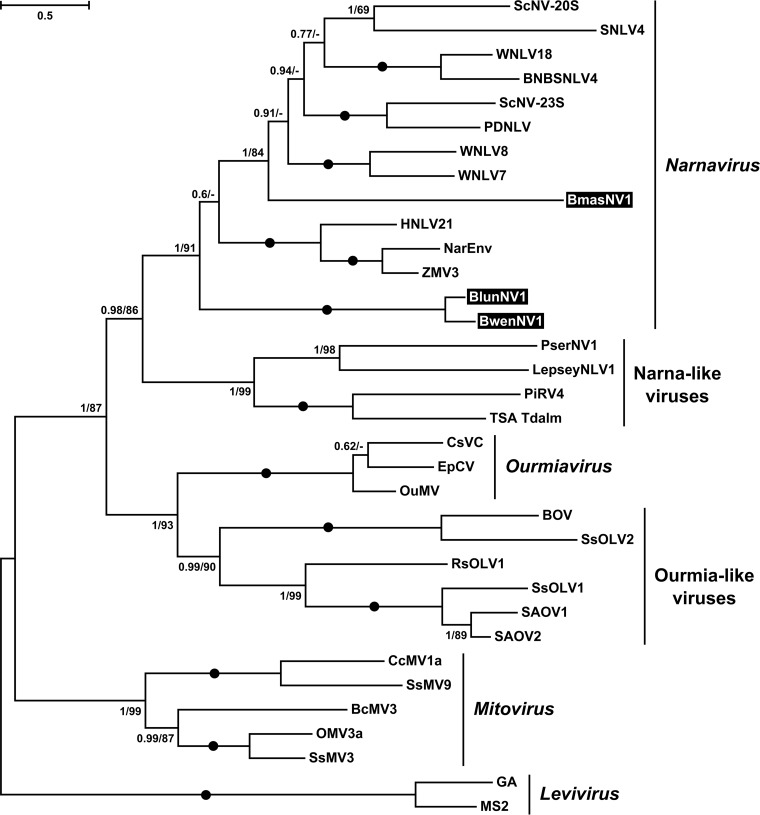

On the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4), Blechomonas NVs (BmasNV1, B. wendygibsoni NV1 [BwenNV1], and BlunNV1) grouped with members of the genus Narnavirus, enclosing prototypical 20S and 23S RNA viruses of S. cerevisiae (34) and viruses found in environmental arthropod metatranscriptomes (35). The previously described representatives of Narnaviridae infecting trypanosomatids Leptomonas seymouri and Phytomonas serpens were situated in a separate clade of the so-called Narna-like viruses (Fig. 4). This fact along with the nonmonophyletic distribution of narnaviruses from Blechomonas spp. suggests that trypanosomatids have acquired these viruses at least three times independently. In addition, a comparison of the phylogenies of trypanosomatids (Fig. 2) and their viruses (Fig. 4) revealed a discrepancy: BlunNV1 forms a sister clade to BwenNV1 and BmasNV1 is not closely related to them, whereas B. luni is more closely related to B. maslovi than to B. wendygibsoni. The most parsimonious explanation of this implies a horizontal transfer of viruses between two unrelated flagellate species. Insect hosts are quite often infected by two or more trypanosomatid species (36–38), potentially facilitating such horizontal transfer.

FIG 4.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Narnaviridae based on RDRP amino acid sequences. Numbers at the branches indicate Bayesian posterior probability and maximum likelihood bootstrap supports, respectively; those having a Bayesian posterior probability value of 1.0 and maximum likelihood bootstrap support of 100% are marked with black circles. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The tree was rooted with the sequences of Leviviridae. Abbreviations and GenBank accession numbers are provided in Table S3.

Leishmaniaviruses: first representatives outside Leishmania.

Three out of 13 analyzed isolates (Blechomonas juanalfonzi, B. maslovi, and B. wendygibsoni) were documented to bear viruses of the genus Leishmaniavirus (LRV) of the family Totiviridae. Their single-RNA genomes contain two overlapping ORFs (+1 ribosomal frameshift) coding for the capsid protein and RDRP (Fig. S2A). The same genomic organization is inherent to leishmanial LRV1s but not LRV2s. The RDRP sequence of the latter virus is either in-frame or in −1 frame relative to the capsid protein (20, 21, 39). A stem-loop structure and a slippery sequence are two structural elements governing the ribosomal frameshift, which were also identified in Blechomonas LRVs (Fig. S2A). As in other members of the Totiviridae, 3′ termini of Blechomonas LRVs were predicted to form stem-loop structures (Fig. S2B). Although not conserved on the sequence level, these cis elements had been implicated in replication and RNA packing of the yeast L-A virus (40) and Leishmania guyanensis LRV1 (41).

Blechomonas LRV1 structural features. (A) Frameshifts in capsid and RDRP ORFs. Slippery sequences are in bold, stop codons are in red, and nucleotides which form Watson-Crick and wobble base pairs are underlined. (B) Putative secondary structures at the 3′ termini of BjuaLRV1, BmasLRV1, and BwenLRV1. Stem-loop structure-forming bases are underlined; stop codons are in red. A structure of LRV1 to -4 from Leishmania guyanensis is shown for comparison. Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.6 MB (649.3KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2018 Grybchuk et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

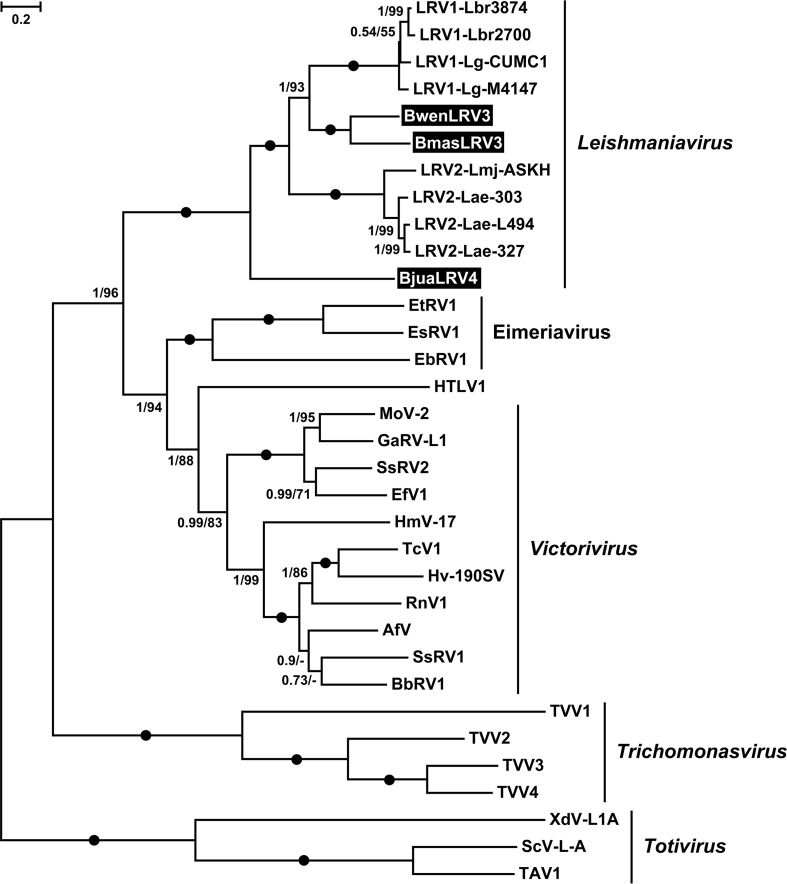

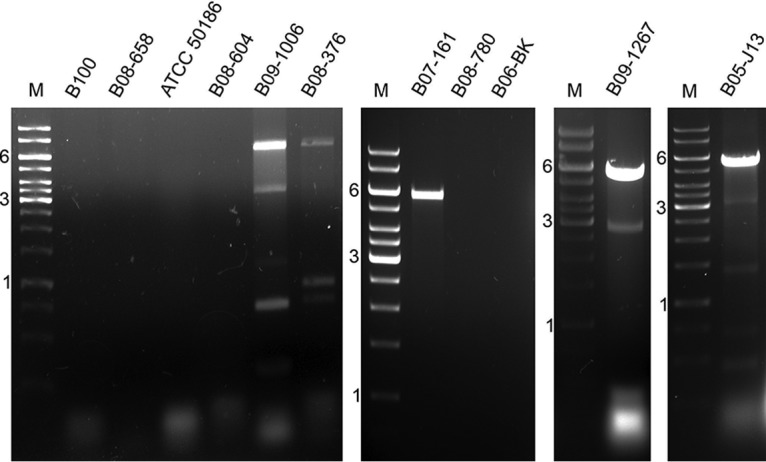

Phylogenetic analyses using a concatenated capsid-RDRP data set demonstrated a strongly supported monophyly of leishmaniaviruses from Leishmania and Blechomonas (Fig. 4) and some intermingling of the two groups (Fig. 5), suggesting a horizontal transfer of viruses between the two distantly related trypanosomatid genera. Given that the new viruses are quite distinct from the previously characterized LRV1 and LRV2, we named the leishmaniaviruses from B. wendygibsoni and B. maslovi LRV3s and the virus from B. juanalfonzi LRV4. B. juanalfonzi LRV4 (BjuaLRV4) represents the deepest branch in the LRV clade, whereas BmasLRV3 and BwenLRV3 are sisters to the LRV1s from the New World Leishmania spp. (Fig. 5 and 6). Similarly to the situation with narnaviruses, there was a significant discrepancy between the phylogenies of the LRVs from Blechomonas and their flagellate hosts. BwenLRV3 and BmasLRV3 formed a clade, whereas BjuaLRV4 was distant from them. The host of BwenLRV3 was not closely related to those of the two other viruses (Fig. 6). This finding marks the first occurrence of viruses from the genus Leishmaniavirus and the family Totiviridae in trypanosomatids other than representatives of the genus Leishmania.

FIG 5.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Leishmaniavirus based on concatenated capsid-RDRP amino acid sequences. Numbers at the branches indicate Bayesian posterior probability and maximum likelihood bootstrap supports, respectively; those having a Bayesian posterior probability value of 1.0 and maximum likelihood bootstrap support of 100% are marked with black circles. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The tree was rooted with the sequences of Trichomonasvirus. Abbreviations and GenBank accession numbers are provided in Table S3.

FIG 6.

Comparison of the phylogenies of leishmaniaviruses and their respective hosts. The scheme is based on the phylogenetic trees presented in Fig. 2 and 5 with simplifications: (i) no branch lengths are shown on either tree and (ii) only LRVs and LRV-containing trypanosomatids were included.

Viral coinfections.

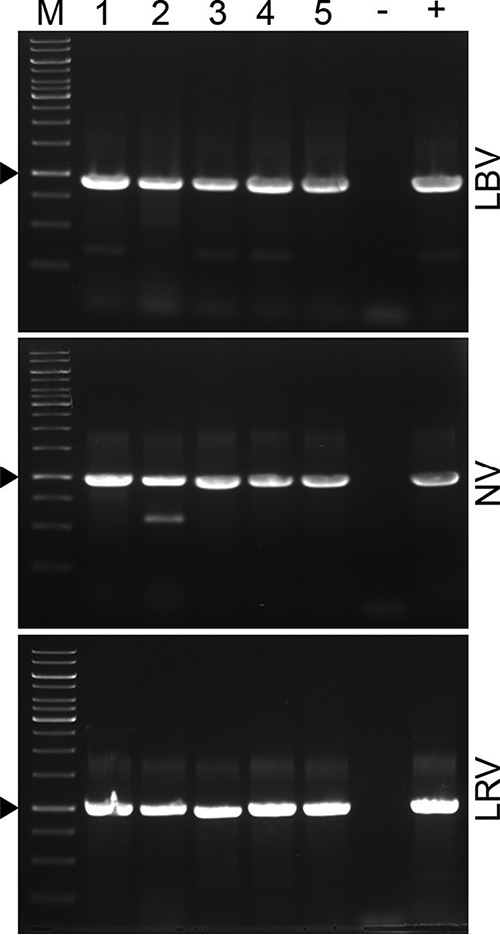

To understand whether coinfecting viruses infect all or just subsets of cells in a given population, we analyzed viral infection in isolated clonal cell lines. As a model, B. maslovi B05-J13 was used to generate clones, because its primary culture was simultaneously infected with three different viruses, namely, LBV, LRV, and NV (Table 1). Our results demonstrate that all obtained clones invariably harbored all three viruses (Fig. 7), confirming this triple infection on the level of single cells.

FIG 7.

LBV, NV, and LRV presence in clonal lines of Blechomonas maslovi B05-J13. RT-PCR analysis with virus-specific primers. M, GeneRuler 1-kb DNA ladder. Clonal lines are numbered from 1 to 5. Triangles denote specific PCR products. −, negative PCR control; +, primary culture of B. maslovi B05-J13 used as a positive control.

Conclusions.

The recent survey of viral diversity in trypanosomatids, which are composed of 52 isolates belonging to ∼20 species from three genera, documented 13 species of RNA viruses and demonstrated that besides the well-studied LRVs, at least four other groups of viruses occur in these flagellates (26). Here, with a relatively modest sampling (13 isolates of 11 species, belonging to a single genus) we were able to discover a comparable number of viruses: nine species from three different groups (leishbunyaviruses, narnaviruses, and leishmaniaviruses). The high number of the new discovered viruses is explained by mixed viral infections in some isolates of Blechomonas spp., representing novel “hotbeds” of viral discovery, as was Leptomonas pyrrhocoris in our previous study. Whether the presence of viruses in Blechomonas is harmful or beneficial to their hosts, e.g., in the interplay with their insect vectors, remains to be investigated further.

Although no new viral groups were documented in Blechomonas spp., our findings are important for the comprehension of viral evolution. The discovery of LBVs in blechomonads was anticipated, since these viruses have envelopes facilitating their interspecific transmission and have already been found in various trypanosomatids and metatranscriptomes with trypanosomatid signatures (26). As in the previous study, in the case of BayaLBV1 and BlunLBV1, we documented potential lateral transfer of viruses and short-term virus-trypanosomatid coevolution.

The new findings concerning narnaviruses demonstrated that their ability for host switching was significantly underestimated (42). Previously, it was considered that owing to the simple organization of these viruses (single RNA coding only for RDRP), they could be transmitted only vertically or during mating (29). Therefore, we have proposed that Leptomonas seymouri and Phytomonas serpens inherited narnaviruses from a common ancestor, while many other trypanosomatids lost them (26). However, all narnaviruses found in Blechomonas spp. were unrelated to those documented in other trypanosomatids and did not form a monophyletic clade by themselves. In addition, a horizontal transfer of viruses is a parsimonious explanation for the sister relationships of the distantly related BlunNV1 and BwenNV1. Thus, we provided evidence that even “naked” viruses are capable of host switching and evidently have accomplished switches multiple times in the course of their evolution. The endocytosis via flagellar pocket of trypanosomatids (43–45) is a plausible route of the acquisition of narnaviruses.

Although none of the three viral groups documented in the Blechomonas hosts is new, the presence of LRVs was unexpected, since until now, they were confined solely to the human pathogens Leishmania spp. (26). The discovery of LRVs in monoxenous trypanosomatids unrelated to Leishmania sheds new light on the origin and evolution of these viruses. As suggested by the phylogenetic analyses, members of the genus Leishmaniavirus apparently originated from the fungal viruses, which represent a regular component of the intestinal microbiome of insects (46, 47). It is tempting to propose an early divergence of BjuaLRV4 as evidence of blechomonads being the first hosts of LRVs, yet deducing a common ancestor of this genus from the phylogenetic tree remains problematic. Indeed, a simple parsimony analysis shows that regardless of whether a given Leishmania or Blechomonas species is selected as an ancestral host, the number of intergeneric transitions remains the same, namely, two. In order to reconstruct the evolution of leishmaniaviruses and, in particular, pinpoint their possible transitions between the Leishmania and Blechomonas hosts, it is important to consider the life cycles of these flagellates and their insect hosts and propose plausible scenarios, in which parasites could meet and exchange their viruses. For Leishmania spp., this is well studied: during blood-feeding of a sandfly on an infected vertebrate host, the parasites enter the gut, where they propagate and then migrate to the anterior part and are transmitted to another vertebrate during the next blood meal (48, 49). However, the life cycles of monoxenous trypanosomatids are largely unknown, but in general, the described routes of transmission include feeding on a contaminated substrate, direct coprophagy, necrophagy, and vertical transmission through eggs’ surfaces (1, 45, 50, 51).

While the life cycles of Blechomonas spp. were never studied, it has been proposed that the infection of fleas occurs at the larval stage and persists into the imago stage (7). Indeed, adult fleas are strictly hematophagous and therefore cannot acquire any pathogen by regular means (52). The flea larvae are scavengers consuming dead insect bodies, conspecific eggs, detritus from host nests, feces of adult fleas, etc., and thus may acquire flagellates by coprophagy and necrophagy. In addition, there should be a transphasic transmission of the protists into adults, i.e., their preservation during metamorphosis (7). Taking into account all these factors, one can only speculate about where Leishmania and Blechomonas meet. This cannot be the sandfly’s gut, since there is no way for a Blechomonas to enter it. It is also unlikely to occur in the blood of a vertebrate, since blechomonads along with their viruses would be quickly eliminated by the immune system before sharing their viruses with Leishmania residing in the highly specific compartment of phagolysosomes of macrophages. In our opinion, the flea gut is the most likely place for such an exchange. Indeed, trypanosomatids can survive in a nonspecific insect host for a considerable period (32, 53), and even Leishmania parasites were detected in adult fleas (54). Both Leishmania and Blechomonas may have enough time for contacts, and they are separated by no barriers in both imagos and larvae. Under these circumstances, leishmanias are doomed and can serve only as donors of viruses. The adult fleas may obtain Leishmania from the blood of an infected vertebrate, while their larvae may become infected after consuming feces of the adults, which are full of partially digested blood (55, 56), or from dead bodies of infected adult sandfly females dying at their breeding grounds, e.g., rodent nests, which are common for both sandfly and flea larvae. According to the presented scenarios, only transmissions of viruses from Leishmania to Blechomonas, but not vice versa, may occur. It was previously proposed that Leishmania spp. coevolved with LRVs for a long time (22). Our findings demonstrate that the evolution of LRVs is much more complex and includes host switching. A recent discovery of an LRV2 in Leishmania infantum (57) suggests that horizontal transfers might occur also between different Leishmania species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasite culture, DNA and RNA isolation, and molecular marker analysis.

The cultures of Blechomonas ayalai, B. campbelli, B. danrayi, B. englundi, B. juanalfonzi, B. keelingi, B. lauriereadi, B. luni, B. maslovi, B. pulexsimulantis, and B. wendygibsoni (a total of 13 isolates [see Table S1 in the supplemental material]) were initially grown on biphasic blood agar overlaid with RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) for 1 to 3 weeks. For DNA and RNA isolation, Blechomonas spp. were subpassaged in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10 µg/ml of hemin (Jena Bioscience GmbH, Jena, Germany), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 500 units/ml of penicillin, and 0.5 mg/ml of streptomycin (all from Thermo Fisher Scientific) as reported previously (9). DNA was isolated from 5 × 107 cells using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and amplified with primers M200 and M201 (for glycosomal glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [gGAPDH]) or S762 and S763 (for 18S rRNA), as described previously (58, 59). PCR products were gel purified and sequenced at Macrogen Europe (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Total RNA was isolated from 0.4 × 109 to 1 × 109 cells as described previously (26).

dsRNA isolation and next-generation sequencing.

The dsRNA fraction was isolated from 200 µg of total RNA using the DNase-S1 nuclease or DNase I-LiCl method (26) and visualized on an 0.8% agarose gel. RiboMinus libraries were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) at Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, South Korea).

Viral genome assembly.

Reads were quality checked with FastQC v0.11.5 (60), trimmed with Trimmomatic v0.36 (61), and assembled de novo with Trinity v2.4.0 (62). Reads were mapped back to the contigs using Bowtie 2 v2.2.9 (63), sorted with SAMtools v1.3 (64), and viewed in Artemis genome browser v1.8 (65). The “per-base” coverage was calculated using BEDTools program v2.25 (66). Contigs containing viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDRP) and leishbunyavirus nucleocapsid protein genes were recovered by TBLASTN searches (67). The M segments of leishbunyaviruses were found by visual inspection of read coverage of obtained contigs. The borders of viral sequences within the contigs were delineated by the presence of conserved sequence elements (complementary terminal sequences and/or secondary structures), and in the case of their absence, a cutoff of 10 reads per base was applied.

Computational analyses. (i) Trypanosomatids.

The trypanosomatid phylogeny was reconstructed using a concatenated 18S rRNA plus gGAPDH gene data set. The core alignments of both genes were taken from a previous study (68), and the groups of interest (Leishmania and Blechomonas) were expanded. The 18S rRNA gene alignment was purged of poorly aligned positions with Gblocks 0.91b as described previously (69). Maximum likelihood analysis of the concatenated alignment was performed in IQ-TREE v. 1.5.5 (70) with a partitioning scheme considering genes and codon positions in the gGAPDH gene. The built-in ModelFinder (71) selected the following partitioned model: TPM2u + I + G4, GTR + I + G4, and K3Pu + I + G4 for the first, second, and third codon positions of the gGAPDH gene, respectively, and TNe + I + G4 for the 18S rRNA gene. The branch support was assessed with the use of standard bootstrap method (1,000 replicates). Bayesian inference was accomplished in MrBayes 3.2.6 (72) as described elsewhere (73) with a slight modification of the partition model: GTR + I + G, GTR + G, and GTR + I + G for the three respective codon positions of the gGAPDH gene and GTR + I + G for the 18S rRNA gene.

(ii) Viruses.

Phylogenetic reconstructions were carried out using the RDRP protein alignments for Bunyavirales and Narnaviridae and concatenated capsid-plus-RDRP protein alignments for Totiviridae. Amino acid sequences were aligned with MAFFT (v. 7.243) using the “E-ins-I” iterative refinement method (74) and trimmed with TrimAl (v. 1.3) with “automated1” settings (75). The scheme of phylogeny reconstruction and the software used were the same as in the case of trypanosomatids (see above). The best-fit models selected by ModelFinder were rtREV + F + I + G4 for Narnaviridae, LG + F + I + G4 for Bunyavirales, and LG + F + G4 and LG + F + I + G4 for capsid and RDRP of Totiviridae, respectively. Bayesian inferences for Narnaviridae and Bunyavirales were performed using mixed amino acid model prior, which resulted in the 1.0 posterior probability for the Blosum model. Heterogeneity over sites in both cases was estimated under the I + G model. For the Totiviridae data set, a partitioned model (LG + I + G, LG + I + G) with unlinked parameters and branch lengths was used. Abbreviations and GenBank accession numbers for viruses used in phylogenetic inferences are listed in Table S3.

Predictions of the transmembrane domains, membrane-targeting signal peptides, and N-glycosylation sites were made in TMHMM (v. 2.0) (76), TMPred (77), Phobius (78), SignalP (v. 4.1) (79), and Signal-BLAST (80).

Cloning of B. maslovi, cDNA synthesis, and screening for viruses by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

A primary culture of B. maslovi B05-J13 (simultaneously coinfected by three different viruses) was cloned by limiting dilution as described previously (10). Total RNA (from 4 × 108 cells) was purified using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) method (81). RNA was treated with DNase I prior to cDNA synthesis using the Super Script IV first-strand synthesis system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with random hexamers according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Viral presence was detected by RT-PCR with the following specific primers: for BmasLBV1, BmasLBV-F 5′-CTAGACTGAGCCCTGATTTC-3′ and BmasLBV-R 5′-ATAACTCGGAATGGTTCTCG-3′ (expected product size 897 bp); for BmasNV1, BmasNV-F 5′-AGTGATCCATTCCGATGATC-3′ and BmasNV-R 5′-AGTCCAAAGTACGAAAGGTC-3′ (expected product size 961 bp); for BmasLRV3, BmasLRV3-F 5′-GCAATTAAGTTCCGACATGG-3′ and BmasLRV3-R 5′-CCAGTTTTTGACTTGGTGTC-3′ (expected product size 980 bp).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the members of our laboratories for stimulating discussions.

Support from the ERD Funds (project OPVVV 16_019/0000759 to J.L. and V.Y.) and the Czech Grant Agency (18-15962S to V.Y. and J.L.) and a grant from the University of Ostrava (to D.H.M.) are kindly acknowledged. This work utilized resources of the IT4Innovations National Supercomputing Center supported by the Czech Ministry of Education (project LM2015070).

Footnotes

Citation Grybchuk D, Kostygov AY, Macedo DH, Votýpka J, Lukeš J, Yurchenko V. 2018. RNA viruses in Blechomonas (Trypanosomatidae) and evolution of Leishmaniavirus. mBio 9:e01932-18. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01932-18.

Contributor Information

Joseph Heitman, Duke University.

Forest Rohwer, San Diego State University.

Matthias Fischer, Max Planck Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maslov DA, Votýpka J, Yurchenko V, Lukeš J. 2013. Diversity and phylogeny of insect trypanosomatids: all that is hidden shall be revealed. Trends Parasitol 29:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lukeš J, Skalický T, Týč J, Votýpka J, Yurchenko V. 2014. Evolution of parasitism in kinetoplastid flagellates. Mol Biochem Parasitol 195:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandes AP, Nelson K, Beverley SM. 1993. Evolution of nuclear ribosomal RNAs in kinetoplastid protozoa: perspectives on the age and origins of parasitism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:11608–11612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamilton PB, Stevens JR, Gaunt MW, Gidley J, Gibson WC. 2004. Trypanosomes are monophyletic: evidence from genes for glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase and small subunit ribosomal RNA. Int J Parasitol 34:1393–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaskowska E, Butler C, Preston G, Kelly S. 2015. Phytomonas: trypanosomatids adapted to plant environments. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004484. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Podlipaev SA. 2000. Insect trypanosomatids: the need to know more. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 95:517–522. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762000000400013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Votýpka J, Suková E, Kraeva N, Ishemgulova A, Duží I, Lukeš J, Yurchenko V. 2013. Diversity of trypanosomatids (Kinetoplastea: Trypanosomatidae) parasitizing fleas (Insecta: Siphonaptera) and description of a new genus Blechomonas gen. n. Protist 164:763–781. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yurchenko V, Kostygov A, Havlová J, Grybchuk-Ieremenko A, Ševčíková T, Lukeš J, Ševčík J, Votýpka J. 2016. Diversity of trypanosomatids in cockroaches and the description of Herpetomonas tarakana sp. n. J Eukaryot Microbiol 63:198–209. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Votýpka J, Kostygov AY, Kraeva N, Grybchuk-Ieremenko A, Tesařová M, Grybchuk D, Lukeš J, Yurchenko V. 2014. Kentomonas gen. n., a new genus of endosymbiont-containing trypanosomatids of Strigomonadinae subfam. n. Protist 165:825–838. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton PT, Votýpka J, Dostalova A, Yurchenko V, Bird NH, Lukeš J, Lemaitre B, Perlman SJ. 2015. Infection dynamics and immune response in a newly described Drosophila-trypanosomatid association. mBio 6:e01356-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01356-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skalický T, Dobáková E, Wheeler RJ, Tesařová M, Flegontov P, Jirsová D, Votýpka J, Yurchenko V, Ayala FJ, Lukeš J. 2017. Extensive flagellar remodeling during the complex life cycle of Paratrypanosoma, an early-branching trypanosomatid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:11757–11762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1712311114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Opperdoes FR, Butenko A, Flegontov P, Yurchenko V, Lukeš J. 2016. Comparative metabolism of free-living Bodo saltans and parasitic trypanosomatids. J Eukaryot Microbiol 63:657–678. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Záhonová K, Kostygov A, Ševčíková T, Yurchenko V, Eliáš M. 2016. An unprecedented non-canonical nuclear genetic code with all three termination codons reassigned as sense codons. Curr Biol 26:2364–2369. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grybchuk D, Kostygov AY, Macedo DH, d’Avila-Levy CM, Yurchenko V. 2018. RNA viruses in trypanosomatid parasites: a historical overview. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 113:e170487. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760170487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartley MA, Ronet C, Zangger H, Beverley SM, Fasel N. 2012. Leishmania RNA virus: when the host pays the toll. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2:99. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Widmer G, Comeau AM, Furlong DB, Wirth DF, Patterson JL. 1989. Characterization of a RNA virus from the parasite Leishmania. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:5979–5982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weeks R, Aline RF Jr, Myler PJ, Stuart K. 1992. LRV1 viral particles in Leishmania guyanensis contain double-stranded or single-stranded RNA. J Virol 66:1389–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartley MA, Drexler S, Ronet C, Beverley SM, Fasel N. 2014. The immunological, environmental, and phylogenetic perpetrators of metastatic leishmaniasis. Trends Parasitol 30:412–422. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ives A, Ronet C, Prevel F, Ruzzante G, Fuertes-Marraco S, Schutz F, Zangger H, Revaz-Breton M, Lye LF, Hickerson SM, Beverley SM, Acha-Orbea H, Launois P, Fasel N, Masina S. 2011. Leishmania RNA virus controls the severity of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Science 331:775–778. doi: 10.1126/science.1199326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zangger H, Hailu A, Desponds C, Lye LF, Akopyants NS, Dobson DE, Ronet C, Ghalib H, Beverley SM, Fasel N. 2014. Leishmania aethiopica field isolates bearing an endosymbiontic dsRNA virus induce pro-inflammatory cytokine response. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8:e2836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheffter SM, Ro YT, Chung IK, Patterson JL. 1995. The complete sequence of Leishmania RNA virus LRV2-1, a virus of an Old World parasite strain. Virology 212:84–90. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Widmer G, Dooley S. 1995. Phylogenetic analysis of Leishmania RNA virus and Leishmania suggests ancient virus-parasite association. Nucleic Acids Res 23:2300–2304. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.12.2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lye LF, Akopyants NS, Dobson DE, Beverley SM. 2016. A narnavirus-like element from the trypanosomatid protozoan parasite Leptomonas seymouri. Genome Announc 4:e00713-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00713-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akopyants NS, Lye LF, Dobson DE, Lukeš J, Beverley SM. 2016. A narnavirus in the trypanosomatid protist plant pathogen Phytomonas serpens. Genome Announc 4:e00711-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00711-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akopyants NS, Lye LF, Dobson DE, Lukeš J, Beverley SM. 2016. A novel bunyavirus-like virus of trypanosomatid protist parasites. Genome Announc 4:e00715-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00715-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grybchuk D, Akopyants NS, Kostygov AY, Konovalovas A, Lye L-F, Dobson DE, Zangger H, Fasel N, Butenko A, Frolov AO, Votýpka J, d’Avila-Levy CM, Kulich P, Moravcová J, Plevka P, Rogozin IB, Serva S, Lukeš J, Beverley SM, Yurchenko V. 2018. Viral discovery and diversity in trypanosomatid protozoa with a focus on relatives of the human parasite Leishmania. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E506–E515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717806115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kostygov AY, Yurchenko V. 2017. Revised classification of the subfamily Leishmaniinae (Trypanosomatidae). Folia Parasitol 64:020. doi: 10.14411/fp.2017.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hillman BI, Cai G. 2013. The family Narnaviridae: simplest of RNA viruses. Adv Virus Res 86:149–176. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394315-6.00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghabrial SA, Castón JR, Jiang D, Nibert ML, Suzuki N. 2015. 50-plus years of fungal viruses. Virology 479-480:356–368. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wickner RB, Fujimura T, Esteban R. 2013. Viruses and prions of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Adv Virus Res 86:1–36. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394315-6.00001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cai G, Myers K, Fry WE, Hillman BI. 2012. A member of the virus family Narnaviridae from the plant pathogenic oomycete Phytophthora infestans. Arch Virol 157:165–169. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kraeva N, Butenko A, Hlaváčová J, Kostygov A, Myškova J, Grybchuk D, Leštinová T, Votýpka J, Volf P, Opperdoes F, Flegontov P, Lukeš J, Yurchenko V. 2015. Leptomonas seymouri: adaptations to the dixenous life cycle analyzed by genome sequencing, transcriptome profiling and co-infection with Leishmania donovani. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005127. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodríguez-Cousiño N, Solorzano A, Fujimura T, Esteban R. 1998. Yeast positive-stranded virus-like RNA replicons. 20 S and 23 S RNA terminal nucleotide sequences and 3' end secondary structures resemble those of RNA coliphages. J Biol Chem 273:20363–20371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lefkowitz EJ, Dempsey DM, Hendrickson RC, Orton RJ, Siddell SG, Smith DB. 2018. Virus taxonomy: the database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Nucleic Acids Res 46:D708–D717. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi M, Lin XD, Tian JH, Chen LJ, Chen X, Li CX, Qin XC, Li J, Cao JP, Eden JS, Buchmann J, Wang W, Xu J, Holmes EC, Zhang YZ. 2016. Redefining the invertebrate RNA virosphere. Nature 540:539–543. doi: 10.1038/nature20167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kozminsky E, Kraeva N, Ishemgulova A, Dobáková E, Lukeš J, Kment P, Yurchenko V, Votýpka J, Maslov DA. 2015. Host-specificity of monoxenous trypanosomatids: statistical analysis of the distribution and transmission patterns of the parasites from Neotropical Heteroptera. Protist 166:551–568. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Votýpka J, Klepetková H, Yurchenko VY, Horák A, Lukeš J, Maslov DA. 2012. Cosmopolitan distribution of a trypanosomatid Leptomonas pyrrhocoris. Protist 163:616–631. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Votýpka J, Maslov DA, Yurchenko V, Jirků M, Kment P, Lun ZR, Lukeš J. 2010. Probing into the diversity of trypanosomatid flagellates parasitizing insect hosts in South-West China reveals both endemism and global dispersal. Mol Phylogenet Evol 54:243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SE, Suh JM, Scheffter S, Patterson JL, Chung IK. 1996. Identification of a ribosomal frameshift in Leishmania RNA virus 1-4. J Biochem 120:22–25. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujimura T, Esteban R, Esteban LM, Wickner RB. 1990. Portable encapsidation signal of the L-A double-stranded RNA virus of S. cerevisiae. Cell 62:819–828. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90125-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheffter S, Widmer G, Patterson JL. 1994. Complete sequence of Leishmania RNA virus 1-4 and identification of conserved sequences. Virology 199:479–483. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dolja VV, Koonin EV. 2018. Metagenomics reshapes the concepts of RNA virus evolution by revealing extensive horizontal virus transfer. Virus Res 244:36–52. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landfear SM, Ignatushchenko M. 2001. The flagellum and flagellar pocket of trypanosomatids. Mol Biochem Parasitol 115:1–17. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(01)00262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gull K. 2003. Host-parasite interactions and trypanosome morphogenesis: a flagellar pocketful of goodies. Curr Opin Microbiol 6:365–370. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(03)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lukeš J, Butenko A, Hashimi H, Maslov DA, Votýpka J, Yurchenko V. 2018. Trypanosomatids are much more than just trypanosomes: clues from the expanded family tree. Trends Parasitol 34:466–480. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Araujo JP, Hughes DP. 2016. Diversity of entomopathogenic fungi: which groups conquered the insect body? Adv Genet 94:1–39. doi: 10.1016/bs.adgen.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitchell PL. 2004. Heteroptera as vectors of plant pathogens. Neotrop Entomol 33:519–545. doi: 10.1590/S1519-566X2004000500001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dostálová A, Volf P. 2012. Leishmania development in sand flies: parasite-vector interactions overview. Parasit Vectors 5:276. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bates PA. 1994. The developmental biology of Leishmania promastigotes. Exp Parasitol 79:215–218. doi: 10.1006/expr.1994.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frolov AO, Malysheva MN, Ganyukova AI, Yurchenko V, Kostygov AY. 2017. Life cycle of Blastocrithidia papi sp. n. (Kinetoplastea, Trypanosomatidae) in Pyrrhocoris apterus (Hemiptera, Pyrrhocoridae). Eur J Protistol 57:85–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frolov AO, Skarlato SO. 1995. Fine structure and mechanisms of adaptation of lower trypanosomatids in Hemiptera. Tsitologiia 37:539–560. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wall R, Shearer D. 2008. Veterinary ectoparasites: biology, pathology and control, 2nd ed. Blackwell Science, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhattarai NR, Das ML, Rijal S, van der Auwera G, Picado A, Khanal B, Roy L, Speybroeck N, Berkvens D, Davies CR, Coosemans M, Boelaert M, Dujardin JC. 2009. Natural infection of Phlebotomus argentipes with Leishmania and other trypanosomatids in a visceral leishmaniasis endemic region of Nepal. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 103:1087–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Morais RCS, Gonçalves-de-Albuquerque SDC, Pessoa e Silva R, Costa PL, da Silva KG, da Silva FJ, Brandão-Filho SP, Dantas-Torres F, de Paiva-Cavalcanti M. 2013. Detection and quantification of Leishmania braziliensis in ectoparasites from dogs. Vet Parasitol 196:506–508. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moser BA, Koehler PG, Patterson RS. 1991. Effect of larval diet on cat flea (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) developmental times and adult emergence. J Econ Entomol 84:1257–1261. doi: 10.1093/jee/84.4.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shryock JA, Houseman RM. 2006. Time spent by Ctenocephalides felis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) larvae in food patches of varying quality. Environ Entomol 35:401–404. doi: 10.1603/0046-225X-35.2.401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hajjaran H, Mahdi M, Mohebali M, Samimi-Rad K, Ataei-Pirkooh A, Kazemi-Rad E, Naddaf SR, Raoofian R. 2016. Detection and molecular identification of Leishmania RNA virus (LRV) in Iranian Leishmania species. Arch Virol 161:3385–3390. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-3044-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maslov DA, Yurchenko VY, Jirků M, Lukeš J. 2010. Two new species of trypanosomatid parasites isolated from Heteroptera in Costa Rica. J Eukaryot Microbiol 57:177–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2009.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maslov DA, Lukes J, Jirku M, Simpson L. 1996. Phylogeny of trypanosomes as inferred from the small and large subunit rRNAs: implications for the evolution of parasitism in the trypanosomatid protozoa. Mol Biochem Parasitol 75:197–205. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02526-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andrews S. 2010. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc.

- 61.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Blood PD, Bowden J, Couger MB, Eccles D, Li B, Lieber M, Macmanes MD, Ott M, Orvis J, Pochet N, Strozzi F, Weeks N, Westerman R, William T, Dewey CN, Henschel R, Leduc RD, Friedman N, Regev A. 2013. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat Protoc 8:1494–1512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramirez-Gonzalez RH, Bonnal R, Caccamo M, Maclean D. 2012. Bio-SAMtools: ruby bindings for SAMtools, a library for accessing BAM files containing high-throughput sequence alignments. Source Code Biol Med 7:6. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Berriman M, Rutherford K. 2003. Viewing and annotating sequence data with Artemis. Brief Bioinform 4:124–132. doi: 10.1093/bib/4.2.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. 2010. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26:841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ishemgulova A, Butenko A, Kortišová L, Boucinha C, Grybchuk-Ieremenko A, Morelli KA, Tesařová M, Kraeva N, Grybchuk D, Pánek T, Flegontov P, Lukeš J, Votýpka J, Pavan MG, Opperdoes FR, Spodareva V, d’Avila-Levy CM, Kostygov AY, Yurchenko V. 2017. Molecular mechanisms of thermal resistance of the insect trypanosomatid Crithidia thermophila. PLoS One 12:e0174165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chistyakova LV, Kostygov AY, Kornilova OA, Yurchenko V. 2014. Reisolation and redescription of Balantidium duodeni Stein, 1867 (Litostomatea, Trichostomatia). Parasitol Res 113:4207–4215. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-4096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. 2017. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods 14:587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Hohna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP. 2012. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol 61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kostygov AY, Grybchuk-Ieremenko A, Malysheva MN, Frolov AO, Yurchenko V. 2014. Molecular revision of the genus Wallaceina. Protist 165:594–604. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Capella-Gutierrez S, Silla-Martinez JM, Gabaldon T. 2009. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. 2001. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hofmann K, Stoffel W. 1993. TMBase—a database of membrane spanning protein segments. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler 374:166. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Käll L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer EL. 2007. Advantages of combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction—the Phobius web server. Nucleic Acids Res 35:W429–W432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. 2011. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods 8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Frank K, Sippl MJ. 2008. High-performance signal peptide prediction based on sequence alignment techniques. Bioinformatics 24:2172–2176. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem 162:156–159. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Blechomonas species isolates used in this work. Species, isolate names, GenBank accession numbers for the gGAPDH and 18S rRNA genes, and host specificity are indicated. Download Table S1, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (14KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2018 Grybchuk et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Transmembrane domains and signal peptides for Blechomonas LBV putative glycoproteins. Download Table S2, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (14KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2018 Grybchuk et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Abbreviations and GenBank accession numbers used for phylogenetic inferences. Download Table S3, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (17.1KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2018 Grybchuk et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Secondary structures and complementary sequences on 5′ and 3′ ends of Blechomonas NVs predicted by IPknot. The short terminal complementary sequences are highlighted. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 0.4 MB (397.5KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2018 Grybchuk et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Blechomonas LRV1 structural features. (A) Frameshifts in capsid and RDRP ORFs. Slippery sequences are in bold, stop codons are in red, and nucleotides which form Watson-Crick and wobble base pairs are underlined. (B) Putative secondary structures at the 3′ termini of BjuaLRV1, BmasLRV1, and BwenLRV1. Stem-loop structure-forming bases are underlined; stop codons are in red. A structure of LRV1 to -4 from Leishmania guyanensis is shown for comparison. Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.6 MB (649.3KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2018 Grybchuk et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.