Abstract

In previous studies, CRISPR/Cas9 was shown to induce unexpected exon skipping; however, the mechanism by which this phenomenon is triggered is controversial. By analyzing 22 gene-edited rabbit lines generated using CRISPR/Cas9, we provide evidence of exon skipping at high frequency in premature termination codon-mutated rabbits but not in the rabbits with a premature termination codon mutation in exon 1 rabbits with non-frameshift or missense mutations. Our results suggest that CRISPR-mediated exon skipping depends on premature termination codon mutation-induced nonsense-associated altered splicing.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13059-018-1532-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Exon skipping, PTC, CRISPR/Cas9, Rabbits

Background

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has been widely used to disrupt gene function and to create premature termination codon (PTC), non-frameshift or missense mutations in target genes [1]. Alternatively, cytidine base editors (CBEs), which are composed of a cytidine deaminase fused to Cas9 nickase, can be used to efficiently inactivate genes by precisely converting four codons (CAA, CAG, CGA and TGG) into stop codons [2, 3].

PTCs are commonly caused by frameshift mutations or nonsense mutations, leading to the generation of truncated proteins with deleterious dominant-negative or gain-of-function effects [4, 5]. To reduce these harmful effects, nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), a well-characterized mRNA surveillance system, recognizes and rapidly degrades mRNAs carrying PTC mutations [6–8]. It is also possible for nonsense-associated alternative splicing (NAS) to produce a transcript that no longer contains the PTC [7, 9]. If the spliced transcript has an in-frame mutation, NAS could produce a truncated protein that potentially retains the function of the corresponding full-length protein [10, 11]. Therefore, NMD and NAS can be regarded as yin and yang responses, respectively. Although the NAS response can upregulate alternatively spliced transcripts to skip offending PTC mutations, the exact mechanism by which this effect is triggered remains controversial.

Recently, several studies have reported a high frequency of exon skipping in gene-edited cells and mice generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system [12–14]. Here, based on summarized analyses of gene-edited rabbits that have been successfully generated in our group [15–19], we present the first evidence that CRISPR-induced exon skipping depends on PTC mutations.

Results

To investigate whether CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing induces unexpected exon skipping, 22 mutant rabbit lines generated using CRISPR/Cas9 or CBEs were utilized in this study (Table 1). We grouped these rabbits as follows: (1) the D3, L2, K2 and K3 lines, each of which had a non-frameshift mutation, (2) the T2-T6 lines, each of which had a missense mutation, (3) the D2, L3, A2, G1, G2, G3, G4, B3 and B4 lines, each of which had a PTC mutation and (4) the M2, M3, Y2 and Y3 lines, each of which carried a PTC in the first exon. Then, genotypes and exon skipping were determined by PCR and RT-PCR, respectively.

Table 1.

Summary of the CRISPR-induced exon skipping in rabbits

| Mutation type | Rabbits lines | Nature of mutation | Predicted ESS | PTC in exon | Exon skipping | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-frameshift | D3 (Additional file 2: Figure S1) | − 75 bp in exon 51 | Yes | No | No | CRISPR/Cas9 |

| L2 (Additional file 2: Figure S2) | (− 4, + 1) bp in exon 2 | Yes | No | No | CRISPR/Cas9 | |

| K2 (Additional file 2: Figure S6) | WT/− 6 bp in exon 3 | Yes | No | No | CRISPR/Cas9 | |

| K3 (Additional file 2: Figure S6) | − 6 bp in exon 3 | Yes | No | No | CRISPR/Cas9 | |

| Missense | T2 (Additional file 2: Figure S7) | C>T in exon 14 | No | No | No | BE3 |

| T3 (Additional file 2: Figure S7) | C>T in exon 14 | No | No | No | BE3 | |

| T4 (Additional file 2: Figure S7) | C>T in exon 14 | No | No | No | BE3 | |

| T5 (Additional file 2: Figure S7) | C>T in exon 14 | No | No | No | BE3 | |

| T6 (Additional file 2: Figure S7) | C>T in exon 14 | No | No | No | BE3 | |

| PTCs | D2 (Additional file 2: Figure S1) | − 157 bp/− 70 bp in exon 51 | Yes | Exon 51 | Exon 51 (233 bp) | CRISPR/Cas9 |

| L3 (Additional file 2: Figure S2) | − 106 bp/− 14 bp in exon 2 | Yes | Exon 2 | Exon 2 (157 bp) | CRISPR/Cas9 | |

| A2 (Additional file 2: Figure S3) | − 10 bp/− 13 bp in exon 12 | Yes | Exon 12 | Exon 12 (223 bp) | CRISPR/Cas9 | |

| G1 (Additional file 2: Figure S4) | − 91 bp in exon 5 | Yes | Exon 5 | Exon 5 (130 bp) | CRISPR/Cas9 | |

| G2 (Additional file 2: Figure S4) | − 14 bp in exon 5 | Yes | Exon 5 | Exon 5 (130 bp) | CRISPR/Cas9 | |

| G3 (Additional file 2: Figure S4) | − 5 bp/− 91 bp in exon 5 | Yes | Exon 5 | Exon 5 (130 bp) | CRISPR/Cas9 | |

| G4 (Additional file 2: Figure S4) | − 5 bp in exon 5 | Yes | Exon 5 | Exon 5(130 bp) | CRISPR/Cas9 | |

| B3 (Additional file 2: Figure S5) | C>T in exon 20 | Yes | Exon 20 | Exon 20 (242 bp) | BE3 | |

| B4 (Additional file 2: Figure S5) | C>T in exon 20 | Yes | Exon 20 | Exon 20 (242 bp) | BE3 | |

| PTCs in exon 1 | M2 (Additional file 2: Figure S8) | C>T in exon 1 | No | Exon 1 | No | BE3 |

| M3 (Additional file 2: Figure S8) | C>Tin exon 1 | No | Exon 1 | No | BE3 | |

| Y2 (Additional file 2: Figure S9) | C>T in exon 1 | No | Exon 1 | No | BE3 | |

| Y3 (Additional file 2: Figure S9) | C>T in exon 1 | No | Exon 1 | No | BE3 |

The ESS sites were predicted by online tool (http://astlab.tau.ac.il/index.php)

−, deletion; +, insert; BE3, Cytidine base editors; ESS, essential splice site

D1, D2, D3, the DMD gene-edited rabbits by CRISPR/Cas9; L1, L2, L3, the LMNA gene-edited rabbits by CRISPR/Cas9; K1, K2, K3, the GCK gene-edited rabbits by CRISPR/Cas9; A1, A2, the ANO5 gene-edited rabbits by CRISPR/Cas9; G1, G2, G3, G4, G5, the GHR gene-edited rabbits by CRISPR/Cas9; B1, B2, B3, B4, the DMD gene-edited rabbits by BE3; T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, T6, the TIA1 gene-edited rabbits by BE3; M1, M2, M3, the MSTN gene-edited rabbits by BE3; Y1, Y2, Y3, the TYR gene-edited rabbits by BE3

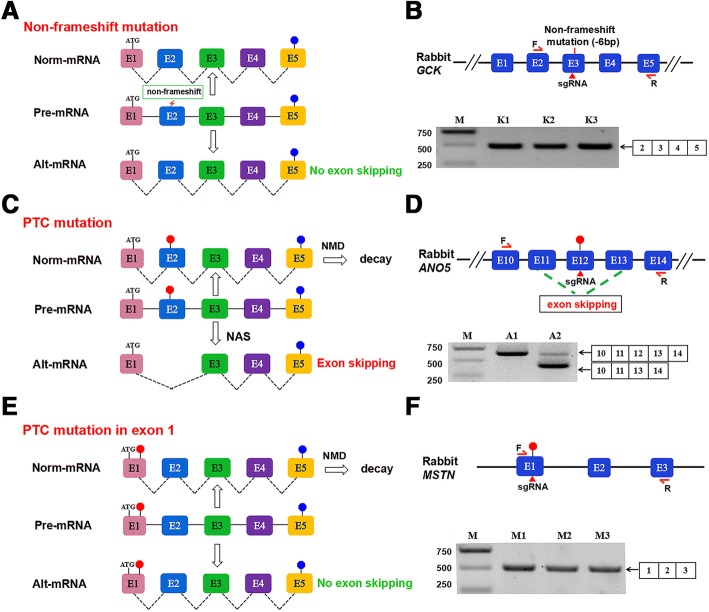

It has been shown that CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing induces unexpected alternative splicing or in-frame exon skipping [12, 20]. Thus, in an attempt to determine whether the gene-edited rabbit lines carrying non-frameshift indels or missense mutations exhibited exon skipping, the D3, L2, K2 and K3 rabbits with non-frameshift mutations and the T2-T6 rabbits carrying missense mutations were analysed (Table 1) (Additional file 1). The RT-PCR results showed clear products that corresponded to normal mRNA transcripts (D3, Additional file 2: Figure S1D; L2, Additional file 2: Figure S2D; K2-K3, Additional file 2: Figure S6D; T2-T6, Additional file 2: Figure S7D), suggesting that no exon skipping occurred in the rabbits with non-frameshift and missense mutations (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Exon skipping induced using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. a No exon skipping in rabbits with a non-frameshift mutation. b Non-frame shift mutation in exon 6 of GCK did not induce exon skipping. Schematic diagram of sgRNA target site in exon 3 of the rabbit GCK gene locus and RT-PCR analysis of GCK gene-editing rabbits for exons 2, 3, 4 and 5. Gel images have been cropped. M, which shows the DL2000 ladder, indicates band size. K1, K2, K3, the GCK gene-edited rabbits used in this study. c CRISPR-mediated exon skipping depends on PTC mutation-induced nonsense-associated altered splicing (NAS). d PTC mutation in exon 12 of ANO5 gene induces exon skipping. Schematic of sgRNA target site in exon 12 of the rabbit ANO5 gene and RT-PCR analysis of ANO5 gene-editing rabbits for exons 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14. Gel images have been cropped. M, which shows the DL2000 ladder, indicates band size. A1-A2, the ANO5 gene-edited rabbits used in this study. e No exon skipping in mutated rabbits with a PTC in exon 1. Rectangle, exon; blue octagon, normal stop codon; red octagon, PTC; NMD, nonsense-mediated decay; NAS, nonsense-associated alternative splicing; ATG, initiation codon; E1-E5, different exons. (F) PTCs mutation in exon 1 of MSTN gene did not induce exon skipping. Schematic diagram of sgRNA target site in exon 1 of the rabbit MSTN gene locus and RT-PCR analysis of MSTN gene editing rabbits for exons 1, 2 and 3. Gel images have been cropped. M, which shows the DL2000 ladder, indicates band size. M1, M2, M3, the MSTN gene-edited rabbits used in this study

Previous studies have shown that NAS-induced exon skipping is a putative corrective response to skip an offending PTC during pre-mRNA splicing [7, 21]. In addition, exon skipping induced by nonsense mutations has been widely reported in clinical cases [11]. To determine whether PTC mutations induced unexpected exon skipping in mutant rabbit lines, the D2, L3, A2, G1, G2, G3, G4, B3 and B4 rabbit lines were analysed (Table 1). The RT-PCR results showed two products in these rabbits: one product corresponding to normal mRNA (norm-mRNA) and the other product corresponding to alt-mRNA produced via exon skipping (D2, Additional file 2: Figure S1D; L3, Additional file 2: Figure S2D; A2, Additional file 2: Figure S3D; G1-G4, Additional file 2: Figure S4D; B3 and B4, Additional file 2: Figure S5D). These results were also confirmed via Sanger sequencing (D2, Additional file 2: Figure S1E; L3, Additional file 2: Figure S2E; A2, Additional file 2: Figure S3E; G1-G4, Additional file 2: Figure S5E), suggesting that exon skipping occurred in the PTC-mutated rabbits (Fig. 1c).

In addition, we also confirmed this hypothesis at the cellular level. As shown in Additional file 2: Figure S10, specific exon skipping occurred when exons contained a PTC but not when exons contained other types of mutations produced when T in PTC was replaced by G or A. Furthermore, published reports on CRISPR/Cas9-induced exon skipping and clinical case reports have confirmed this principle, which could be used to predict exon skipping induced by the CRISPR/Cas9 system (Additional file 3: Table S1).

To further explore the idea of whether a PTC in exon 1 can induce exon skipping in mutant rabbits, M2, M3, Y1 and Y2 rabbits were analysed. As shown in Additional file 2: Figure S8E and Figure S9E, RT-PCR results clearly showed products corresponding to normal transcripts in these rabbits. Furthermore, qPCR results showed no significant differences in transcript level between exon 1 and other exons (M2-M3, Additional file 2: Figure S8F; Y2-Y3, Additional file 2: Figure S9F), suggesting that no exon skipping was observed in mutated rabbits with a PTC in exon 1 (Fig. 1e).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that CRISPR-mediated exon skipping depends on PTC mutations but was not observed in rabbits with non-frameshift and missense mutations; these findings are consistent with clinical cases in which mutations induced exon skipping of the COL11A2 and FBN1 genes in patients [12, 22, 23]. We also show that this principle can be used to predict CRISPR-mediated exon skipping in future studies. Moreover, our data support the hypothesis of a nuclear scanning mechanism that identifies pre-mRNAs harboring a PTC and then induces exon skipping [7, 24], an idea consistent with observations of unregulated alternative splicing to skip disruption of the reading frame in genes with nonsense mutations [25, 26].

Currently, although the roles of NMD and cis-acting regulatory elements have been proposed to be associated with alternative splicing of exons or exon deletion, the exact mechanisms by which these events are triggered remain elusive. Previous studies have demonstrated that mutations in putative essential splice site (ESS) could cause aberrant or alternative splicing [27–29]. In our study, although ESRs were found in both the non-frameshift mutation lines (D3, L2, K2 and K3) and the PTC-mutated rabbit lines (D2, L3, A2, G1, G2, G3, G4, B3 and B4), exon skipping was identified only in PTC-mutated rabbits. Hence, we speculate that PTC mutations that disrupt ESS may be responsible for exon skipping, although more types of gene mutations and examinations of mechanisms for triggering NAS should be assessed in further research.

Conclusions

Overall, this article is the first report describing a high frequency of exon skipping in PTC-mutated rabbits generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Moreover, our results highlight that predictions of potential exon skipping are important for interpreting negative results or conducting genotype-to-phenotype studies in genome-edited animals generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system.

Additional files

Supplemental materials and Methods. (PDF 614 kb)

Figure S1. PTC mutation in exon 51 of DMD gene induces exon skipping. Figure S2. PTC mutation in exon 2 of LMNA gene induces exon skipping. Figure S3. PTC mutation in exon 12 of ANO5 gene induces exon skipping. Figure S4. PTC mutation in exon 5 of GHR gene induces exon skipping. Figure S5. PTC mutation in exon 20 of DMD gene induces exon skipping. Figure S6. Non-frame shift mutation in exon 6 of GCK did not induce exon skipping. Figure S7. Missense mutations in the last exon of the TIA1 gene did not induce exon skipping. Figure S8. PTCs mutation in exon 1 of MSTN gene did not induce exon skipping. Figure S9. PTCs in exon 1 of TYR gene did not induce exon skipping. Figure S10. PTC mutation in exon 2 of OXT gene induces exon skipping. (PDF 1853 kb)

Table S1. Examples according to the published reports on CRISPR/Cas9-induce exon-skipping and the case reports in clinical. Table S2. PCR primers for genotyping of the gene editing rabbits. Table S3. Primers for RT-PCR analysis of exon skipping. Table S4. Primers for qPCR analysis. (PDF 561 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Peiran Hu for excellent technical assistance at the Embryo Engineering Center.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China Stem Cell and Translational Research (2017YFA0105101). The Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (No.IRT_16R32). The Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA16030501, XDA16030503), Guangdong Province science and technology plan project (2014B020225003).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated in the study has been included in the manuscript and additional files.

Abbreviations

- CBEs

Cytidine base editors

- ESS

Essential splice site

- indels

Insertions or deletions

- NAS

Nonsense-associated alternative splicing

- NMD

Nonsense-mediated decay

- PTC

Premature termination codon

- sgRNA

Single-guide RNA

Authors’ contributions

TS, LL and ZL conceived and designed the experiments. TS performed the experiments. TS, YS, ZL and LL analysed the data. MC, ZL, YX and JD contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. TS and ZL wrote the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The gene editing rabbits were generated in our group, all procedures using rabbits were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Jilin University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Liangxue Lai, Email: lai_liangxue@gibh.ac.cn.

Zhanjun Li, Email: lizj_1998@jlu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, Zhang F. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature. 2016;533:420–424. doi: 10.1038/nature17946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billon P, Bryant EE, Joseph SA, Nambiar TS, Hayward SB, Rothstein R, Ciccia A. CRISPR-Mediated Base editing enables efficient disruption of eukaryotic genes through induction of STOP codons. Mol Cell. 2017;67:1068–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hilleren P, Parker R. mRNA surveillance in eukaryotes: kinetic proofreading of proper translation termination as assessed by mRNP domain organization? RNA. 1999;5:711–719. doi: 10.1017/S1355838299990519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frischmeyer PA, Dietz HC. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in health and disease. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1893–1900. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.10.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popp MW, Maquat LE. Leveraging rules of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay for genome engineering and personalized medicine. Cell. 2016;165:1319–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hentze MW, Kulozik AE. A perfect message: RNA surveillance and nonsense-mediated decay. Cell. 1999;96:307–310. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neu-Yilik G, Amthor B, Gehring NH, Bahri S, Paidassi H, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE. Mechanism of escape from nonsense-mediated mRNA decay of human beta-globin transcripts with nonsense mutations in the first exon. RNA. 2011;17:843–854. doi: 10.1261/rna.2401811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu HX, Cartegni L, Zhang MQ, Krainer AR. A mechanism for exon skipping caused by nonsense or missense mutations in BRCA1 and other genes. Nat Genet. 2001;27:55–58. doi: 10.1038/83762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang YF, Chan WK, Imam JS, Wilkinson MF. Alternatively spliced T-cell receptor transcripts are up-regulated in response to disruption of either splicing elements or reading frame. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29738–29747. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valentine CR. The association of nonsense codons with exon skipping. Mutat Res. 1998;411:87–117. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5742(98)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mou H, Smith JL, Peng L, Yin H, Moore J, Zhang XO, Song CQ, Sheel A, Wu Q, Ozata DM, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing induces exon skipping by alternative splicing or exon deletion. Genome Biol. 2017;18:108. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prykhozhij SV, Steele SL, Razaghi B, Berman JN. A rapid and effective method for screening, sequencing and reporter verification of engineered frameshift mutations in zebrafish. Dis Model Mech. 2017;10:811–822. doi: 10.1242/dmm.026765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharpe JJ, Cooper TA. Unexpected consequences: exon skipping caused by CRISPR-generated mutations. Genome Biol. 2017;18:109. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lv Q, Yuan L, Deng J, Chen M, Wang Y, Zeng J, Li Z, Lai L. Efficient generation of myostatin gene mutated rabbit by CRISPR/Cas9. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25029. doi: 10.1038/srep25029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sui T, Yuan L, Liu H, Chen M, Deng J, Wang Y, Li Z, Lai L. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutation of PHEX in rabbit recapitulates human X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:2661–2671. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan L, Yao H, Xu Y, Chen M, Deng J, Song Y, Sui T, Wang Y, Huang Y, Li Z, Lai L. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutation of alphaA-Crystallin gene induces congenital cataracts in rabbits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:BIO34–BIO41. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-21287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song Y, Yuan L, Wang Y, Chen M, Deng J, Lv Q, Sui T, Li Z, Lai L. Efficient dual sgRNA-directed large gene deletion in rabbit with CRISPR/Cas9 system. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:2959–2968. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2143-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z, Chen M, Chen S, Deng J, Song Y, Lai L, Li Z. Highly efficient RNA-guided base editing in rabbit. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2717. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lalonde S, Stone OA, Lessard S, Lavertu A, Desjardins J, Beaudoin M, Rivas M, Stainier DYR, Lettre G. Frameshift indels introduced by genome editing can lead to in-frame exon skipping. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dietz HC. Nonsense mutations and altered splice-site selection. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:729–730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vuoristo MM, Pappas JG, Jansen V, Ala-Kokko L. A stop codon mutation in COL11A2 induces exon skipping and leads to non-ocular stickler syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;130A:160–164. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caputi M, Kendzior RJ, Jr, Beemon KL. A nonsense mutation in the fibrillin-1 gene of a Marfan syndrome patient induces NMD and disrupts an exonic splicing enhancer. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1754–1759. doi: 10.1101/gad.997502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendell JT, Dietz HC. When the message goes awry: disease-producing mutations that influence mRNA content and performance. Cell. 2001;107:411–414. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Chang YF, Hamilton JI, Wilkinson MF. Nonsense-associated altered splicing: a frame-dependent response distinct from nonsense-mediated decay. Mol Cell. 2002;10:951–957. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendell JT, ap Rhys CM, Dietz HC. Separable roles for rent1/hUpf1 in altered splicing and decay of nonsense transcripts. Science. 2002;298:419–422. doi: 10.1126/science.1074428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moseley CT, Mullis PE, Prince MA, Phillips JA., 3rd An exon splice enhancer mutation causes autosomal dominant GH deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:847–852. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otsuka H, Sasai H, Nakama M, Aoyama Y, Abdelkreem E, Ohnishi H, Konstantopoulou V, Sass JO, Fukao T. Exon 10 skipping in ACAT1 caused by a novel c.949G>A mutation located at an exonic splice enhancer site. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:4906–4910. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewandowska MA. The missing puzzle piece: splicing mutations. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:2675–2682. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental materials and Methods. (PDF 614 kb)

Figure S1. PTC mutation in exon 51 of DMD gene induces exon skipping. Figure S2. PTC mutation in exon 2 of LMNA gene induces exon skipping. Figure S3. PTC mutation in exon 12 of ANO5 gene induces exon skipping. Figure S4. PTC mutation in exon 5 of GHR gene induces exon skipping. Figure S5. PTC mutation in exon 20 of DMD gene induces exon skipping. Figure S6. Non-frame shift mutation in exon 6 of GCK did not induce exon skipping. Figure S7. Missense mutations in the last exon of the TIA1 gene did not induce exon skipping. Figure S8. PTCs mutation in exon 1 of MSTN gene did not induce exon skipping. Figure S9. PTCs in exon 1 of TYR gene did not induce exon skipping. Figure S10. PTC mutation in exon 2 of OXT gene induces exon skipping. (PDF 1853 kb)

Table S1. Examples according to the published reports on CRISPR/Cas9-induce exon-skipping and the case reports in clinical. Table S2. PCR primers for genotyping of the gene editing rabbits. Table S3. Primers for RT-PCR analysis of exon skipping. Table S4. Primers for qPCR analysis. (PDF 561 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated in the study has been included in the manuscript and additional files.