Abstract

Background

Both the hydrogen sulfide/cystathionine-γ-lyase (H2S/CSE) and oxytocin/oxytocin receptor (OT/OTR) systems have been reported to be cardioprotective. H2S can stimulate OT release, thereby affecting blood volume and pressure regulation. Systemic hyper-inflammation after blunt chest trauma is enhanced in cigarette smoke (CS)-exposed CSE−/− mice compared to wildtype (WT). CS increases myometrial OTR expression, but to this point, no data are available on the effects CS exposure on the cardiac OT/OTR system. Since a contusion of the thorax (Txt) can cause myocardial injury, the aim of this post hoc study was to investigate the effects of CSE−/− and exogenous administration of GYY4137 (a slow release H2S releasing compound) on OTR expression in the heart, after acute on chronic disease, of CS exposed mice undergoing Txt.

Methods

This study is a post hoc analysis of material obtained in wild type (WT) homozygous CSE−/− mice after 2-3 weeks of CS exposure and subsequent anesthesia, blast wave-induced TxT, and surgical instrumentation for mechanical ventilation (MV) and hemodynamic monitoring. CSE−/− animals received a 50 μg/g GYY4137-bolus after TxT. After 4h of MV, animals were exsanguinated and organs were harvested. The heart was cut transversally, formalin-fixed, and paraffin-embedded. Immunohistochemistry for OTR, arginine-vasopressin-receptor (AVPR), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was performed with naïve animals as native controls.

Results

CSE−/− was associated with hypertension and lower blood glucose levels, partially and significantly restored by GYY4137 treatment, respectively. Myocardial OTR expression was reduced upon injury, and this was aggravated in CSE−/−. Exogenous H2S administration restored myocardial protein expression to WT levels.

Conclusions

This study suggests that cardiac CSE regulates cardiac OTR expression, and this effect might play a role in the regulation of cardiovascular function.

Keywords: Cystathionine-γ-lyase, GYY4137, Arginine-vasopressin receptor, Vascular endothelial growth factor, Blood glucose, Cardiovascular system

Background

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is an important regulator of the cardiovascular system and has been shown to be protective in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (I/R) [1–3] and heart failure [4]. In the central nervous system, H2S has recently been implicated in the release of both oxytocin (OT) and arginine-vasopressin (AVP), thereby affecting blood volume regulation [5].

In mice, the genetic deletion of cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE; CSE−/−) leads to hypertension [6, 7], and OT knock-out mice (OT−/−) are characterized by lower baseline but higher stress-induced blood pressure than wildtype (WT) animals [8]. The heart is known to express CSE [9, 10], and both OT as well as the OT receptor (OTR) [11]. The oxytocin system has protective effects in myocardial I/R injury [12–15], and its downregulation is implicated in dilated cardiomyopathy [16], and hypertension [17], suggesting that reduced levels of OTR may aggravate these pathologies [18].

Pre-traumatic cigarette smoke (CS) exposure has been reported to aggravate organ dysfunction after trauma and hemorrhage [19]. However, equivocal data regarding the regulation of CSE in CS-exposed rodents are available: both its up- and downregulation have been reported [20–23]. Furthermore, detrimental effects of CSE inhibition as well as a benefit from the exogenous administration of H2S have been shown [22–24]. Finally, in a model of acute on chronic disease, we recently showed that post-traumatic systemic hyper-inflammation and acute lung injury (ALI) were aggravated in CSE−/− with pre-traumatic CS exposure when compared to wildtype (WT) littermates [7].

Scarce data are only available on the role of the OT system during acute and/or chronic alterations of gas exchange: OT signaling is protective in fetal hypoxemia [25] and hypercapnia-induced tachycardia and hypertension [26], and CS exposure increases myometrial OTR expression [27, 28]. However, no data are available on any of these effects on the cardiac OT/OTR system. Txt not only causes ALI but is also frequently associated with myocardial injury [29, 30]. Therefore, we chose to investigate OTR expression in heart tissue from the most severely affected groups from the aforementioned previous study [7] that included a modulation of the H2S system.

Methods

This is a post hoc study of material available from previous experiments [7] that were performed in adherence to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines on the Use of Laboratory Animals and the European Union “Directive 2010/63 EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.” and authorized by the federal authorities for animal research of the Regierungspräsidium Tübingen (approved animal experimentation number: 1130), Baden-Württemberg, Germany, and the Animal Care Committee of the University of Ulm, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The experiments were conducted on C57BL/6J mice that were received from Charles River laboratories Germany (Sulzbach, Germany) and homozygous (CSE−/−) mutant mice (C57BL/6J.129SvEv) bred in-house [6]. Animals were kept under standardized conditions and were equally distributed in terms of age, body weight, and sex (10–25 weeks, 26 +/− 3 g, male and female). Native animals were anesthetized with sevoflurane (2.5%; Sevorane, Abbott, Wiesbaden, HE, Germany) and buprenorphine (1.5 mg/g; Temgesic, Reckitt Benckiser, Slough, UK), mid-line laparotomy was performed, and animals were sacrificed via venous exsanguination. Hearts were harvested and fixed in formalin for further analysis.

Cigarette smoke inhalation procedure

All animals underwent CS exposure for 5 days per week over a period of 3 to 4 weeks using a standardized protocol, as described previously [31]. Prior to the blast wave procedure, mice were allowed to recover for 1 week to avoid acute stress effects induced by the CS procedure per se.

General anesthesia, blast wave, and surgery

All animals received a Txt and were grouped according to wild type (WT) and CSE−/− with CS exposure. Prior to chest trauma WT and knock-out mice (n = 8 per group) were anesthetized with sevoflurane (2.5%; Sevorane, Abbott, Wiesbaden, HE, Germany) and buprenorphine (1.5 mg/g; Temgesic, Reckitt Benckiser, Slough, UK), as described previously [31]. Blunt chest trauma was induced by a single blast wave positioned on the middle of the thorax, as described previously [32]. Briefly, a Mylar polyester film (Du Pont de Nemur, Bad Homburg, Germany) was rapidly ruptured by compressed air, thereby releasing a single blast wave to the murine mid-sternal chest to reproducibly induce a lung contusion without serious organ damage. Immediately afterwards, CSE−/− mice received an administration of GYY4137 or an equivalent volume of saline as a single intravenous injection of 50 μg/g [33, 34], and all mice received ketamine (120 mg/g; Ketanest-S, Pfizer, New York City, NY), midazolam (1.25 mg/g; Midazolam-ratiopharm, Ratiopharm, Ulm, BW, Germany), and fentanyl (0.25 mg/g; Fentanyl-hameln, Hameln Pharma Plus GmbH, Hameln, NI, Germany), and were placed on a procedure bench incorporating a closed-loop-system for body temperature control [7, 32, 35]. Lung-protective mechanical ventilation using a small animal ventilator (FlexiVent, Scireq, MO, Canada) was performed via a tracheostomy, as described previously [7, 31, 35]. Surgical instrumentation comprised catheters in the jugular vein, the carotid artery, and the bladder [31]. General anesthesia was titrated to guarantee complete tolerance against noxious stimuli and was sustained by continuous intravenous administration of ketamine, midazolam, and fentanyl to reach deep sedation, fluid resuscitation comprised hydroxyethyl starch 6% (Tetraspan, Braun Medical, Melsungen, HE, Germany) [31]. At the end of the experiment, the animals were exsanguinated and organs were harvested. The heart was cut transversally and was fixed in formalin for immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Hemodynamic and metabolic parameters were recorded hourly, blood gas tensions, acid-base status, glycemia, and lactatemia were assessed at the end of the 4 h period of mechanical ventilation [31]. The clinical data provided for the experimental groups are obtained from the mouse ICU, which requires surgical instrumentation and thus cannot be provided for the native animals.

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was performed as described previously [32, 36, 37]. After formalin fixation, hearts were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and 3 μm sections were cut. Slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated, followed by heat-induced antigen retrieval by microwaving in 10 mM citrate (pH 6). After blocking with 10% goat serum (20 min), OTR, Arginine Vasopressin Receptor 1A (AVPR), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression were analyzed with the following primary antibodies: anti-OTR (rabbit polyclonal, Proteintech, Manchester, UK 1:50), anti-AVPR (rabbit polyclonal, Abcam, Cambridge, UK 1:200), and anti-VEGF (rabbit polyclonal, Abcam, Cambridge, UK 1:200) in diluent (TBS pH = 8, 0.3% Tween 20, 0.1% goat serum). Slide sections containing native and experimental tissue were analyzed concurrently, as well as positive and negative controls. AVPR was analyzed because it shares a 57% homology to OTR and thus, OT can work through AVPR as well [38]. The expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was determined as a mediator of cardiac function [39, 40] and H2S is reported to be cardioprotective via a VEGF-dependent pathway [4]. Primary antibodies were detected by a secondary anti-rabbit IgG antibody conjugated to Alkaline Phosphatase; Jackson, ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pa, USA) and visualized with a red chromogen (Dako REAL Detection System Chromogen Red, Agilent Santa Clara, CA, USA). Counterstaining was performed with Mayers hematoxylin (Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany). Slides were analyzed using the Zeiss Axio Imager A1 microscope (Zeiss, Jena, TH, Germany). Two distinct 800,000 μm2 regions were quantified for intensity of signal by using the Axio Vision 4.8 software. Results are presented as densitometric sum red [31, 32, 36].

Statistical analysis

Unless stated otherwise, all data are presented as median (quartiles). After exclusion of normal distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, intergroup differences were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA on ranks and, if appropriate, subsequently the Dunn post hoc test for two-tailed multiple comparisons. The significance level was set to P < 0.05. Quantitative graphical presentations and statistical analyses were done with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Physiological data

All injured animals used in this study underwent pre-traumatic CS exposure and Txt. Physiological data are shown in Table 1. CSE−/− mice showed higher heart rates than the WT mice, and GYY4137 did not affect this parameter. CSE−/− mice also had significantly higher MAP than the WT animals, and GYY4137 fell in between the two other groups. CSE−/− mice had lower circulating glucose levels than wildtypes; GYY4137 administration restored circulating glucose to normal levels. Further, CSE−/− mice had reduced lactate levels, less negative base excess and higher pH in comparison to WT, GYY4137 did not have any statistically significant effects on these parameters.

Table 1.

Physiological data of injured animals (CS exposure + Txt)

| WT | CSE−/− | CSE−/− GYY4137 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 330 (316; 356) | 402 (390; 410)a | 395 (363; 438)a | 0.0140 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 57 (55; 59) | 84 (74; 89)a | 75 (63; 88) | 0.0044 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 92 (86; 107) | 76 (72; 82)a | 95 (90; 104) b | 0.0186 |

| Lactate (mmol/l) | 1.1 (1.0; 1.5) | 0.7 (0.6; 0.8)a | 0.9 (0.8; 1.1) | 0.0035 |

| Arterial base excess (mmol/l) | − 10.2 (− 11.0; − 8.5) | −5.7 (− 7.0; − 4.9)a | − 6.9 (− 9.4; − 5.0) | 0.0107 |

| Arterial pH | 7.25 (7.25; 7.28) | 7.37 (7.33; 7.41)a | 7.35 (7.29; 7.37) | 0.0059 |

| Urine (g) | 0.6 (0.4; 0.9) | 1.9 (1.7; 2.6)a | 1.3 (1.2; 1.7) | 0.0037 |

Data given as median (interquartile range)

aSignificant to wt

bSignificant to CSE−/−

Protein expression in the heart

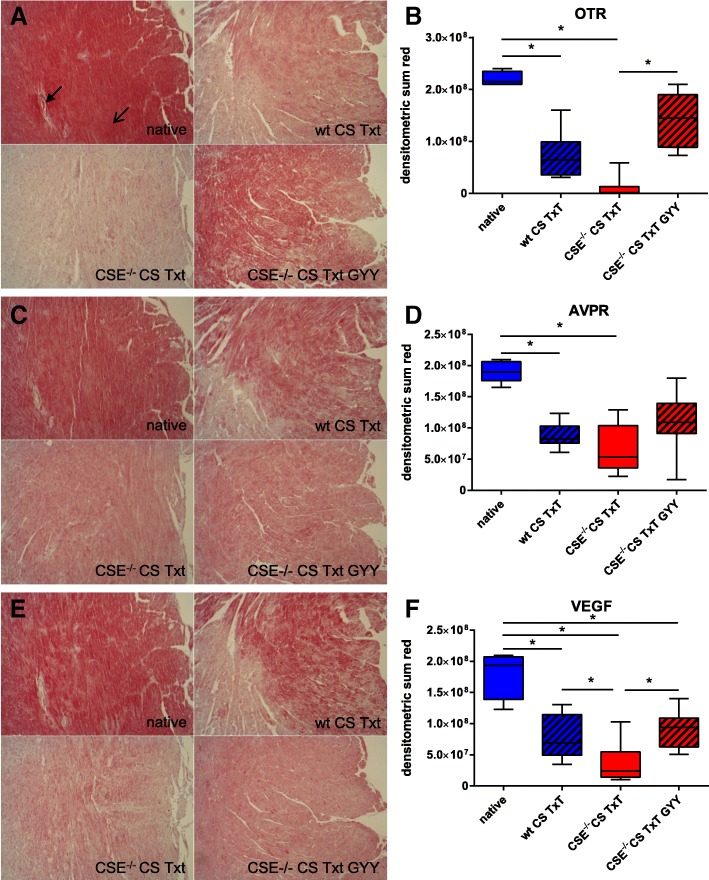

Oxytocin receptor (OTR) expression in the heart (see Fig. 1a, b) was constitutive in native animals and could be detected in cardiomyocytes (open arrow) as well as the cardiac microvasculature (bold arrow, Fig. 1a). CS + Txt significantly reduced cardiac OTR expression, and this effect was further enhanced in the CSE−/− animals. Exogenous administration of GYY4137 restored OTR expression so that receptor protein levels did not significantly differ from native animals. Cardiac AVPR expression was also significantly reduced in injured animals, though the effect of CSE deletion was less pronounced GYY4137 administration did not modify this response (see Fig. 1c, d). VEGF expression was reduced upon injury, most pronounced in CSE−/− animals but then restored to WT levels upon GYY4137 treatment (see Fig. 1e, f).

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemistry. Exemplary pictures (top left native, top right WT CS Txt, bottom left CSE−/− CS Txt, bottom right CSE−/− CS Txt GYY4137, respectively) of left-ventricular myocardium (ventricular lumen to the right) and densitometric analysis for OTR expression (a, b), AVPR expression (c, d), and VEGF expression (e, f). Data given as box plots (median, interquartile range, minimum and maximum). Boxplots represent N = 4 (native) and N = 8 (experimental groups). Open arrow cardiomyocyte, bold arrow cardiac microvasculature

Discussion

This study was to test the hypothesis if there is a relationship between the H2S and the OTR system in the mouse heart in the combined setting of “acute on chronic disease.” The main findings were that Txt after pre-traumatic CS exposure caused (i) a significant downregulation of the cardiac OTR which was (ii) even more pronounced in mice with a genetic CSE deletion of, and that (iii) the administration of the slow H2S-releasing compound GYY4137 reversed the effects of CSE deletion.

CSE−/− mice were characterized by higher MAP (75–90 mmHg), which is in accordance with the literature: a genetic CSE deletion leads to hypertension [6], although this effect appears to be context-dependent (anesthesia, handling of the animals etc.) [41]. In C57/BL6 mice undergoing continuous i.v. anesthesia MAP is approx. 60 mmHg [42], which is comparable to the values WT animals in this study. Administration of GYY4137 slightly reduced MAP, preserved or restored the OTR, VEGF, and AVPR in the heart, suggesting cardioprotection as has been reported in myocardial I/R [43–46] and chronic heart failure [47].

Both H2S and OT have been implicated in the regulation of energy homeostasis: H2S enhances glucose-generating and suppresses glucose-consuming processes leading to increased glucose availability [37]. OT/OTR knock-out mice develop obesity [48], and chronic OT administration led to weight loss in obese monkeys [49]. We and others have shown that hyperglycemia leads to downregulation of CSE expression and reduction of H2S formation [37, 50–52]. These results agree with a similar finding for the OT/OTR system: reduced OT levels were reported during hyperglycemia [18, 53].

Equivocal data, however, have been reported on the relationship between H2S and the OT system: both the H2S liberating salt Na2S and the slow-releasing compound GYY4137 inhibited OT effects; however, all the data were obtained in myometrial samples [54–56]. Moreover, You et al. showed an inverse correlation of CSE and OTR expression [57]. In contrast, intracerebroventricular Na2S injection not only reduced water intake and stimulated OT release, but also increased plasma levels of AVP and OT [5, 58]. Our findings support these latter results: not only did we observe a more pronounced loss of OTR expression in absence of CSE, but the OTR was restored to native levels through GYY4137 administration.

Due to structural analogy of OT and arginine vasopressin (AVP), the peptides might bind to each other’s receptor [38], and, consequently, we also investigated the AVPR expression. Our results suggest that cardiac AVPR is not as impacted by H2S administration as the OTR.

H2S has been reported to work through a VEGF-dependent pathway [4] that mediates cardioprotection [39, 40]. VEGF, in the GYY4137 group, as previously mentioned, was restored to WT levels. This suggests a link for the interaction of the H2S pathway and the OT/OTR system, in that OT also has been reported to signal through the activation of VEGF [59–61].

Conclusions

In this preliminary study, performed on post hoc material, we investigated the relationship between CSE, OTR, and H2S in the mouse heart after CS exposure and Txt. Genetic CSE deletion led to a pronounced loss of OTR protein expression concomitant with reduced VEGF and AVPR expression. Although the exact mechanisms must be further investigated, our study suggests that cardiac CSE and OTR may interact in cardiovascular (dys)function [10, 18, 37, 49].

Acknowledgements

We thank Rosy Engelhardt for skillful technical assistance.

Funding

This study has been funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG, CRC1149 (B02 PR, GEROK MWe) IGradU (DW), and Ulm University (Herta-Narthorff-Programm CH).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- ALI

Acute lung injury

- AVP

Arginine-vasopressin

- AVPR

AVP receptor

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CS

Cigarette smoke

- CSE

Cystathionine-γ-lyase

- H2S

Hydrogen sulfide

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure

- OT

Oxytocin

- OTR

OT receptor

- Txt

Blunt chest trauma

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- WT

Wildtype

Authors’ contributions

TM performed the immunohistochemistry, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. BL and DW performed the immunohistochemistry. AR, MWe, and CH participated in the physiological data analysis. MWe and MG performed animal experiments and collected the data. MWh, CS, RW, CW, and PR conceived the study, helped with the data interpretation, and critically reviewed the manuscript. OM contributed to the experimental design, quantification of immunohistochemistry, data interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

This is a post hoc study of material available from previous experiments that were performed in adherence to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines on the Use of Laboratory Animals and the European Union “Directive 2010/63 EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.” and authorized by the federal authorities for animal research of the Regierungspräsidium Tübingen (approved animal experimentation number: 1130), Baden-Württemberg, Germany, and the Animal Care Committee of the University of Ulm, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tamara Merz, Phone: +49 731 500 60182, Email: tamara.merz@uni-ulm.de.

Britta Lukaschewski, Email: britta.lukaschewski@uni-ulm.de.

Daniela Wigger, Email: daniela.wigger@uni-ulm.de.

Aileen Rupprecht, Email: aileen-rupprecht@web.de.

Martin Wepler, Email: martin.wepler@uni-ulm.de.

Michael Gröger, Email: michael.groeger@uni-ulm.de.

Clair Hartmann, Email: clair.hartmann@uni-ulm.de.

Matthew Whiteman, Email: M.Whiteman@exeter.ac.uk.

Csaba Szabo, Email: szabocsaba@aol.com.

Rui Wang, Email: rui.wang@lakeheadu.ca.

Christiane Waller, Email: christiane.waller@uniklinik-ulm.de.

Peter Radermacher, Email: peter.radermacher@uni-ulm.de.

Oscar McCook, Email: oscar.mccook@uni-ulm.de.

References

- 1.Geng B, Yang J, Qi Y, Zhao J, Pang Y, Du J, Tang C. H2S generated by heart in rat and its effects on cardiac function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313(2):362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, Doeller JE, Kraus DW, Tao L, Jiao X, Scalia R, Kiss L, Szabo C, Kimura H, Chow CW, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(39):15560–15565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calvert JW, Jha S, Gundewar S, Elrod JW, Ramachandran A, Pattillo CB, Kevil CG, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide mediates cardioprotection through Nrf2 signaling. Circ Res. 2009;105(4):365–374. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kondo K, Bhushan S, King AL, Prabhu SD, Hamid T, Koenig S, Murohara T, Predmore BL, Gojon G, Sr, Gojon G, Jr, Wang R, Karusula N, Nicholson CK, Calvert JW, Lefer DJ. H2S protects against pressure overload-induced heart failure via upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2013;127(10):1116–1127. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000855.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coletti R, Almeida-Pereira G, Elias LL, Antunes-Rodrigues J. Effects of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) on water intake and vasopressin and oxytocin secretion induced by fluid deprivation. Horm Behav. 2015;67:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang G, Wu L, Jiang B, Yang W, Qi J, Cao K, Meng Q, Mustafa AK, Mu W, Zhang S, Snyder SH, Wang R. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science. 2008;322(5901):587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1162667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartmann C, Hafner S, Scheuerle A, Möller P, Huber-Lang M, Jung B, Nubaum B, McCook O, Gröger M, Wagner F, Weber S, Stahl B, Calzia E, Georgieff M, Szabó C, Wang R, Radermacher P, Wagner K. The role of cystathionine-γ-lyase in blunt chest trauma in cigarette smoke exposed mice. Shock. 2017;47(4):491–499. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernatova I, Rigatto KV, Key MP, Morris M. Stress-induced pressor and corticosterone responses in oxytocin-deficient mice. Exp Physiol. 2004;89(5):549–557. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2004.027714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nußbaum BL, McCook O, Hartmann C. Left ventricular function during porcine resuscitated septic shock with pre-existing atherosclerosis. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2016;4:14. doi: 10.1186/s40635-016-0089-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merz T, Stenzel T, Nußbaum B, Wepler M, Szabo C, Wang R, Radermacher P, McCook O. Cardiovascular disease and resuscitated septic shock lead to the downregulation of the H2S-producing enzyme cystathionine-γ-lyase in the porcine coronary artery. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2017;5:17. doi: 10.1186/s40635-017-0131-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutkowska J, Jankowski M, Lambert C, Mukaddam-Daher S, Zingg HH, McCann SM. Oxytocin releases atrial natriuretic peptide by combining with oxytocin receptors in the heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(21):11704–11709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moghimian M, Faghihi M, Karimian SM, Imani A, Houshmand F, Azizi Y. Role of central oxytocin in stress-induced cardioprotection in ischemic-reperfused heart model. J Cardiol. 2013;61(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alizadeh AM, Faghihi M, Sadeghipour HR, Mohammadghasemi F, Khori V. Role of endogenous oxytocin in cardiac ischemic preconditioning. Regul Pept. 2011;167(1):86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ondrejcakova M, Barancik M, Bartekova M, Ravingerova T, Jezova D. Prolonged oxytocin treatment in rats affects intracellular signaling and induces myocardial protection against infarction. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2012;31(3):261–270. doi: 10.4149/gpb_2012_030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jankowski M, Bissonauth V, Gao L, Gangal M, Wang D, Danalache B, Wang Y, Stoyanova E, Cloutier G, Blaise G, Gutkowska J. Anti-inflammatory effect of oxytocin in rat myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105(2):205–218. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutkowska J, Broderick TL, Bogdan D, Wang D, Lavoie JM, Jankowski M. Downregulation of oxytocin and natriuretic peptides in diabetes: possible implications in cardiomyopathy. J Physiol. 2009;587(Pt 19):4725–4736. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broderick TL, Wang Y, Gutkowska J, Wang D, Jankowski M. Downregulation of oxytocin receptors in right ventricle of rats with monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2010;200(2):147–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jankowski M, Broderick TL, Gutkowska J. Oxytocin and cardioprotection in diabetes and obesity. BMC Endocr Disord. 2016;16(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s12902-016-0110-1.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartmann C, Gröger M, Noirhomme JP, Scheuerle A, Möller P, Wachter U, Huber-Lang M, Nussbaum B, Jung B, Merz T, McCook O, Kress S, Stahl B, Calzia E, Georgieff M, Radermacher P, Wepler M (2018) In-depth characterization of the effects of cigarette smoke exposure on the acute trauma response and hemorrhage in mice. Shock. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001115 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Chen YH, Yao WZ, Geng B, Ding YL, Lu M, Zhao MW, Tang CS. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide in patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;128(5):3205–3211. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Ya-Hong, Wang Pei-Pei, Wang Xin-Mao, He Yan-Jing, Yao Wan-Zhen, Qi Yong-Fen, Tang Chao-Shu. Involvement of endogenous hydrogen sulfide in cigarette smoke-induced changes in airway responsiveness and inflammation of rat lung. Cytokine. 2011;53(3):334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Wang R. The message in the air: hydrogen sulfide metabolism in chronic respiratory diseases. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2012;184(2):130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han W, Dong Z, Dimitropoulou C, Su Y. Hydrogen sulfide ameliorates tobacco smoke-induced oxidative stress and emphysema in mice. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15(8):2121–2134. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun Y, Wang K, Li MX, He W, Chang JR, Liao CC, Lin F, Qi YF, Wang R, Chen YH. Metabolic changes of H2S in smokers and patients of COPD which might involve in inflammation, oxidative stress and steroid sensitivity. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14971. doi: 10.1038/srep14971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinozuka N, Yen A, Nathanielsz PW. Alteration of fetal oxygenation and responses to acute hypoxemia by increased myometrial contracture frequency produced by pulse administration of oxytocin to the pregnant ewe from 96 to 131 days' gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(5):1202–1208. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70617-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jameson H, Bateman R, Byrne B, Dyavanapalli J, Wang X, Jain V, Mendelowitz D. Oxytocin neuron activation prevents hypertension that occurs with chronic intermittent hypoxia/hypercapnia in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;310(11):H1549–H1557. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00808.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanamori C, Yasuda K, Sumi G, Kimura Y, Tsuzuki T, Cho H, Okada H, Kanzaki H. Effect of cigarette smoking on mRNA and protein levels of oxytocin receptor and on contractile sensitivity of uterine myometrium to oxytocin in pregnant women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;178:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamoto T, Yasuda K, Yasuhara M, Nakajima T, Mizokami T, Okada H, Kanzaki H. Cigarette smoke extract enhances oxytocin-induced rhythmic contractions of rat and human preterm myometrium. Reproduction. 2006;132(2):343–353. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaye P, O'Sullivan I. Myocardial contusion: emergency investigation and diagnosis. Emerg Med J. 2002;19(1):8–10. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalbitz Miriam, Pressmar Jochen, Stecher Johanna, Weber Birte, Weiss Manfred, Schwarz Stephan, Miltner Erich, Gebhard Florian, Huber-Lang Markus. The Role of Troponin in Blunt Cardiac Injury After Multiple Trauma in Humans. World Journal of Surgery. 2016;41(1):162–169. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3650-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner K, Gröger M, McCook O, Scheuerle A, Asfar P, Stahl B, Huber-Lang M, Ignatius A, Jung B, Duechs M, Möller P, Georgieff M, Calzia E, Radermacher P, Wagner F. Blunt chest trauma in mice after cigarette smoke-exposure: effects of mechanical ventilation with 100% O2. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner F, Scheuerle A, Weber S, Stahl B, McCook O, Knöferl MW, Huber-Lang M, Seitz DH, Thomas J, Asfar P, Szabó C, Möller P, Gebhard F, Georgieff M, Calzia E, Radermacher P, Wagner K. Cardiopulmonary, histologic, and inflammatory effects of intravenous Na2S after blunt chest trauma-induced lung contusion in mice. J Trauma. 2011;71(6):1659–1667. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318228842e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L, Whiteman M, Guan YY, Neo KL, Cheng Y, Lee SW, Zhao Y, Baskar R, Tan CH, Moore PK. Characterization of a novel, water-soluble hydrogen sulfide-releasing molecule (GYY4137): new insights into the biology of hydrogen sulfide. Circulation. 2008;117(18):2351–2360. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.753467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li L, Salto-Tellez M, Tan CH, Whiteman M, Moore PK. GYY4137, a novel hydrogen sulfide-releasing molecule, protects against endotoxic shock in the rat. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47(1):103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner F, Wagner K, Weber S, Stahl B, Knöferl MW, Huber-Lang M, Seitz DH, Asfar P, Calzia E, Senftleben U, Gebhard F, Georgieff M, Radermacher P, Hysa V. Inflammatory effects of hypothermia and inhaled H2S during resuscitated, hyperdynamic murine septic shock. Shock. 2011;35(4):396–402. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181ffff0e.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stenzel T, Weidgang C, Wagner K, Wagner F, Gröger M, Weber S, Stahl B, Wachter U, Vogt J, Calzia E, Denk S, Georgieff M, Huber-Lang M, Radermacher P, McCook O. Association of kidney tissue barrier disrupture and renal dysfunction in resuscitated murine septic shock. Shock. 2016;46(4):398–404. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000599.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merz T, Vogt JA, Wachter U, Calzia E, Szabo C, Wang R, Radermacher P, McCook O. Impact of hyperglycemia on cystathionine-γ-lyase expression during resuscitated murine septic shock. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2017;5(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s40635-017-0140-7.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zingg HH. Vasopressin and oxytocin receptors. Bailliere Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;10(1):75–96. doi: 10.1016/S0950-351X(96)80314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giordano FJ, Gerber HP, Williams SP, VanBruggen N, Bunting S, Ruiz-Lozano P, Gu Y, Nath AK, Huang Y, Hickey R, Dalton N, Peterson KL, Ross J, Jr, Chien KR, Ferrara N. A cardiac myocyte vascular endothelial growth factor paracrine pathway is required to maintain cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(10):5780–5785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091415198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu XH, Xu J, Xue L, Cao HL, Liu X, Chen YJ. VEGF attenuates development from cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure after aortic stenosis through mitochondrial mediated apoptosis and cardiomyocyte proliferation. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:54. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-6-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szijártó IA, Markó L, Filipovic MR, Miljkovic JL, Tabeling C, Tsvetkov D, Wang N, Rabelo LA, Witzenrath M, Diedrich A, Tank J, Akahoshi N, Kamata S, Ishii I, Gollasch M. Cystathionine γ-lyase-produced hydrogen sulfide controls endothelial NO bioavailability and blood pressure. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1210–1217. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zuurbier CJ, Emons VM, Ince C. Hemodynamics of anesthetized ventilated mouse models: aspects of anesthetics, fluid support, and strain. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282(6):H2099–H2105. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01002.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meng G, Wang J, Xiao Y, Bai W, Xie L, Shan L, Moore PK, Ji Y. GYY4137 protects against myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury by attenuating oxidative stress and apoptosis in rats. J Biomed Res. 2015;29(3):203–213. doi: 10.7555/JBR.28.20140037.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lilyanna S, Peh MT, Liew OW, Wang P, Moore PK, Richards AM, Martinez EC. GYY4137 attenuates remodeling, preserves cardiac function and modulates the natriuretic peptide response to ischemia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;87:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karwi QG, Whiteman M, Wood ME, Torregrossa R, Baxter GF. Pharmacological postconditioning against myocardial infarction with a slow-releasing hydrogen sulfide donor, GYY4137. Pharmacol Res. 2016;111:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chatzianastasiou A, Bibli SI, Andreadou I, Efentakis P, Kaludercic N, Wood ME, Whiteman M, Di Lisa F, Daiber A, Manolopoulos VG, Szabó C, Papapetropoulos A. Cardioprotection by H2S donors: nitric oxide-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;358(3):431–440. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.235119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gan XB, Liu TY, Xiong XQ, Chen WW, Zhou YB, Zhu GQ. Hydrogen sulfide in paraventricular nucleus enhances sympathetic activity and cardiac sympathetic afferent reflex in chronic heart failure rats. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e50102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Camerino C. Low sympathetic tone and obese phenotype in oxytocin-deficient mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17(5):980–984. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blevins JE, Graham JL, Morton GJ, Bales KL, Schwartz MW, Baskin DG, Havel PJ. Chronic oxytocin administration inhibits food intake, increases energy expenditure, and produces weight loss in fructose-fed obese rhesus monkeys. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;308(5):R431–R438. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00441.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang G. H2S and glucose metabolism, how does the stink regulate the sweet? Immunoendocrinology. 2015;3:e1066. doi: 10.14800/ie.1066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pan Z, Wang H, Liu Y, et al. Involvement of CSE/ H2S in high glucose induced aberrant secretion of adipokines in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Lipids Health Dis. 2014;13:155. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-13-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guan Q, Liu W, Liu Y, et al. High glucose induces the release of endothelin-1 through the inhibition of hydrogen sulfide production in HUVECs. Int J Mol Med. 2015;35:810–814. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Widmaier EP, Shah PR, Lee G. Interactions between oxytocin, glucagon and glucose in normal and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Regul Pept. 1991;34(3):235–249. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(91)90182-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayden LJ, Franklin KJ, Roth SH, Moore GJ. Inhibition of oxytocin-induced but not angiotensin-induced rat uterine contractions following exposure to sodium sulfide. Life Sci. 1989;45(26):2557–2560. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robinson H, Wray S. A new slow releasing, H2S generating compound, GYY4137 relaxes spontaneous and oxytocin-stimulated contractions of human and rat pregnant myometrium. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e46278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu R, Lu J, You X, Zhu X, Hui N, Ni X. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits the spontaneous and oxytocin-induced contractility of human pregnant myometrium. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27(11):900–904. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2010.551563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.You X, Chen Z, Zhao H, Xu C, Liu W, Sun Q, He P, Gu H, Ni X. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide contributes to uterine quiescence during pregnancy. Reproduction. 2017;153(5):535–543. doi: 10.1530/REP-16-0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruginsk SG, Mecawi AS, da Silva MP, Reis WL, Coletti R, de Lima JB, Elias LL, Antunes-Rodrigues J. Gaseous modulators in the control of the hypothalamic neurohypophyseal system. Physiology (Bethesda) 2015;30(2):127–138. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00040.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Katsouda A, Bibli SI, Pyriochou A, Szabo C, Papapetropoulos A. Regulation and role of endogenously produced hydrogen sulfide in angiogenesis. Pharmacol Res. 2016;113(Pt A):175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gutkowska J, Jankowski M, Antunes-Rodrigues J. The role of oxytocin in cardiovascular regulation. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2014;47(3):206–214. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20133309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dayi A, Cetin F, Sisman AR, Aksu I, Tas A, Gönenc S, Uysal N. The effects of oxytocin on cognitive defect caused by chronic restraint stress applied to adolescent rats and on hippocampal VEGF and BDNF levels. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:69–75. doi: 10.12659/MSM.893159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.