Abstract

Objective

To synthesise qualitative studies on women’s psychological experiences of physiological childbirth.

Design

Meta-synthesis.

Methods

Studies exploring women’s psychological experiences of physiological birth using qualitative methods were eligible. The research group searched the following databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, SocINDEX and Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection. We contacted the key authors searched reference lists of the collected articles. Quality assessment was done independently using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist. Studies were synthesised using techniques of meta-ethnography.

Results

Eight studies involving 94 women were included. Three third order interpretations were identified: ‘maintaining self-confidence in early labour’, ‘withdrawing within as labour intensifies’ and ‘the uniqueness of the birth experience’. Using the first, second and third order interpretations, a line of argument developed that demonstrated ‘the empowering journey of giving birth’ encompassing the various emotions, thoughts and behaviours that women experience during birth.

Conclusion

Giving birth physiologically is an intense and transformative psychological experience that generates a sense of empowerment. The benefits of this process can be maximised through physical, emotional and social support for women, enhancing their belief in their ability to birth and not disturbing physiology unless it is necessary. Healthcare professionals need to take cognisance of the empowering effects of the psychological experience of physiological childbirth. Further research to validate the results from this study is necessary.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42016037072.

Keywords: childbirth, physiological childbirth, lived experiences, pyschological, empowerment, obstetrics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Strict inclusion criteria were applied so that only studies where all women had unmedicated births were included.

Some births had occurred more than 10 years before. Parity was not differentiated as a criteria.

All selected studies came from high-income countries.

All births were attended by midwives and a relatively large number of women included in this study had a home birth.

Introduction

Childbirth is a profound psychological experience that has a physical, psychological, social and existential impact both in the short and long term.1 It leaves lifelong vivid memories for women.2 The effects of a birth experience can be positive and empowering, or negative and traumatising.3–5 Regardless of their cultural background, women need to share their birth stories to fully integrate an experience that is both physically and emotionally intense.6

Neurobiologically, childbirth is directed by hormones produced both by the maternal and the fetal brain.7 During childbirth and immediately after delivery, both brains are immersed in a very specific neurohormonal scenario, impossible to reproduce artificially. The psychology of childbirth is likely to be mediated by these neuro-hormones, as well as by particular cultural and personal issues. The peaks of endogenous oxytocin during labour, together with the progressive release of endorphins in the maternal brain, are likely to cause the altered state of consciousness most typical of unmedicated labour that midwives and mothers easily recognise or describe as ‘labour land’, but this phenomenon has received little attention from neuropsychology.

Midwives and obstetricians require a deep understanding of the emotional aspects of childbirth in order to meet the emotional and psychosocial needs of labouring women. Factors that facilitate a positive birth experience include having a sense of control during birth, an opportunity for active involvement in care and support and responsive care from others in relation to women’s experience of labour pain.8–10 There is limited research on women’s lived experience of physiological childbirth, including their emotional response.11–13 This lack of knowledge concerning the psychological dimension of childbirth can lead to mismanagement of the birthing process. At the extreme, a lack of understanding of the psychology of childbirth can contribute to a traumatising birth, which can be devastating to women even when the immediate outcome is a physically healthy mother and newborn.14 When women in labour encounter caregivers who do not incorporate emotional needs into their care, they can experience this as disrespect, mistreatment or in some instances, as a form of abuse15 or obstetric violence.16 The problem of disrespect towards women in labour is a growing concern globally, as is also the over-application of medicalised care practices for healthy women.17–19 Rates for these interventions vary greatly between and within countries. For example, using 2010 Euro-Peristat data, Macfarlane et al 17(2016) reported on a range in spontaneous vaginal birth from 45.3% to 78.5%.20

The medical model has traditionally divided labour into stages according to mechanical or physical changes such as dilation of the cervix and descent of the head as depicted on the traditional Friedman’s curve or WHO partograph.21 However, the subjective, emotional experience of labour does not conform to these mechanical descriptions of the body’s changes. It is questionable that women experience specific stages or phases as traditionally described by professionals.22 Understanding the psychological experience in physiological childbirth can contribute to enhancing a salutogenic approach to health and can contribute to the promotion of healthy, happy family relationships in the longer term.

The aim of this meta-synthesis is to locate and synthesise published qualitative studies that describe the psychological process of women during physiological childbirth, paying attention to the immanent psychological responses that emerge during the process of labour and birth. We hypothesised that there is a common psychological experience of physiological labour. We focus on labouring women’s thoughts and feelings, and the meanings they ascribe to their perceptions of childbirth process and the surrounding environment, as reaction to both childbirth and to the surrounding environment are part of a single psychological process. We refer to the psychological process in terms of the ‘lived experience’ and thus we adopted a Husserlian a phenomenological approach for the analysis of the data in the included studies.

Methods

Design

We undertook a meta-synthesis. This is a process of reviewing and consolidating qualitative research, to create a summary of qualitative findings and allow for the development of new interpretations (Thomas and Harden, 2008). Qualitative synthesis of a number of qualitative studies provides robust evidence to inform healthcare practices. Meta-ethnography was deemed the most appropriate qualitative synthesis approach for this analysis in order to transcend the findings of individual study accounts in developing a conceptual model.23 This synthesis method has the potential to provide a higher level of analysis and generate new conceptual understandings.24 The research approach used for this meta-synthesis was the seven-step process described by Noblit and Hare,25 26 which uses meta-ethnographic techniques like reciprocal and refutational techniques as well as line of argument synthesis. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statements to inform the meta-synthesis.27 The research protocol was registered and published in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews.28

Patients and public were not involved in the design, conception or conduct of this study.

Data sources

A systematic search was conducted in March 2016 and updated in October 2017. The following databases were included: EBSCOhost, including the database MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, SocINDEX and Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection. The search terms are given in online supplementary appendix 1. (We used EBSCOhost for the complete search and therefore did not use MeSH terms.) Eligible papers were written in English, Spanish and Portuguese. Five groups of two authors independently read the abstracts and selected the articles, and the decision to include an article was achieved by consensus. When there was disagreement, a third author provided assistance and input. We searched reference lists of the included articles to identify additional articles that were relevant to the study question. We sought suggestions from experts in the field and articles from other sources.

bmjopen-2017-020347supp001.pdf (166.3KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

For the purpose of our study, physiological childbirth was defined as an uninterrupted process without major interventions, such as induction, augmentation, instrumental assistance, caesarean section as well as use of epidural anaesthesia or other pain relief medications. The inclusion criteria were (1) original research of (2) women who had physiological childbirth and (3) described their experiences and behaviours during (4) the whole process of childbirth. Studies were excluded, if the experience of childbirth was (1) described by any source other than the woman who experienced the birth (eg, from healthcare professionals), (2) described only a single stage in the birth process or (3) described births with major medical and surgical interventions (or pain management (eg, caesarean section).

Data extraction and synthesis

Data analysis included the following steps. The first order interpretation involved reading and re-reading all studies to become familiar with their content, feeling and tone. The first author (IO) conducted a line-by-line coding of the findings of all included studies. Quotes, interpretations and explanations in the original studies were treated as data. The coding categories included: feelings, behaviours (actions), signs (eg, pain, contractions), relations (midwife, partner, baby and relatives), time perception, cognitions (thoughts and knowledge) and location (home, water, places, transferring). Based on the emerging data, these coding categories were sorted into (1) early labour, (2) intense labour, (3) pushing, (4) baby out (immediately), (5) placenta and (6) evaluation of the whole birth experience.

To achieve the second and third order interpretation, the research team reflected on the first order interpretations to identify the themes and subthemes that describe the emerging constructs grounded in the primary studies. This process included reciprocal (similarity) and refutational (contradictory) analysis which identified differences, divergences and dissonance between the studies and then to synthesise these translations. Following this reflection process, the research team used a line of argument to create a model that best explains the psychological process of physiological childbirth, as described in the included studies.

Quality assessment

To ensure the quality of the findings in the study, all selected papers were screened on the methodological quality using CASP29 and subsequently, all the included papers were assessed using consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ)30 to ensure they had reported all the relevant details of their methodological and analytic approach.

Reflexivity

Throughout the research process, the authors identified and explored their own views and opinions as possible influences on the decisions taken. This was done because of the subjective nature of qualitative research to protect the methodological rigour of the study. All the authors of this paper are part of an EU-funded COST Action specifically examining aspects of physiological birth. The research group have chosen to participate in the COST Action IS1405 Building Intrapartum Research Thorugh Health (BIRTH) because of strong interests in the importance of understanding physiological and psychological processes of childbirth, to enhance the capacity of women to labour and give birth normally where this was possible for them, and where it is their choice to do so. All the authors believe that birth is a profound physiological, psychological and socio-cultural experience for most women and babies.

The research team included authors of multidisciplinary backgrounds. The contribution of each author, coming from different paradigms and perspectives on women’s needs in labour, ensured the interpretation of findings was grounded in the data and came from the data. The use of refutational analyses, as recommended by Noblit and Hare20 21 minimises the risk of overlooking information because it did not fit with the authors’ pre-conceptions. This strengthens the trustworthiness of this research.

Results

Included studies

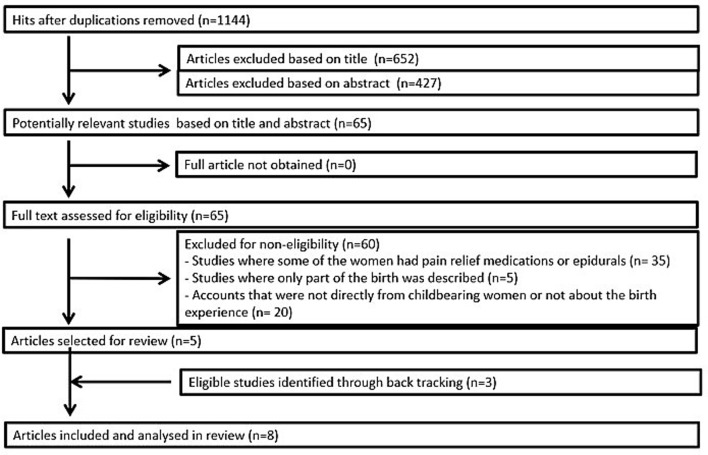

The search identified 1520 articles in EBSCOhost. There were 376 duplicates, which were removed, leaving 1144 unique articles in the sample. figure 1 demonstrates the selection process, which resulted in eight included studies. All of the selected studies met the quality screening and assessment criteria. Some papers had to be excluded because just one or a few participants did not have a physiological birth as defined for this study. CASP and COREQ assessments are detailed in the online supplementary files.

Figure 1.

Flow chart.

bmjopen-2017-020347supp002.pdf (75.6KB, pdf)

The eight included studies involved 94 women, 28 primiparous and 22 multiparous women, although four studies did not identify parity in their sample. Of these, two studies had a mix of primiparous and multiparous women (half each)17 27 and two studies did not address parity for the sample at all.28 29 Most of the interviews took place within a year after birth, but some studies had longer intervals, and in two studies, women were interviewed up to 10 or 20 years after birth.11 31 One study did not identify a time interval between the index birth and the interview.32 Thirty-nine of the women gave birth at home, four in a primary care unit and 51 in hospital. It seems that midwives were the primary carers of these women. Further characteristics of the studies can be found in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of selected studies

| Author(s)/year | Title | Country | Methodology | N parity | Time after birth | Birth setting | objective |

| 1. Aune et al 3 | Promoting a normal birth and a positive birth experience—Norwegian women’ s perspectives | Norway | Qualitative, focused on salutogenic principles | 12 prim | 5–6 weeks | Hospital birth unit | To understand factors important for a normal birth and positive birth experience |

| 2. Dixon et al 13 | The emotional journey of labour-women’s perspectives of the experience of labour moving towards birth | New Zealand | Critical feminist standpoint methodology |

6 prim, 12 multi |

6 months | Midwifery continuity care: 7 homebirths, 4 primary care, 7 tertiary care |

To explore women’s experiences of birth |

| 3. Hall & Holloway34 | Staying in control: Women’s experiences of labour in water | UK | Grounded theory, using the constant comparative method |

9 (no parity given) | 48 hours | Hospital (water birth) | To examine women’s attempt at control during labour in the water |

| 4. Halldorsdottir and Karlsdottir 11 | Journeying through labour and delivery: Perceptions of women who have given birth | Iceland | Phenomenological perspective | 14 (mix of parity) | 2 months to 20 years | Hospital | To explore experience of giving birth |

| 5. Leap et al 33 | Journey to confidence: Women’s experiences of pain in labour and relational continuity of care | UK | Qualitative, descriptive, thematic analysis |

5 prim, 5 multi |

4 weeks | Albany midwifery practice, home and hospital | To explore women’s view of continuity of care and pain in labour |

| 6. Ng & Sinclair32 | Women’s experience of planned home birth: A phenomenological study | UK | Phenomenological perspective |

9 (no parity given) | Not mentioned | Homebirths | To explore women’s lived experiences of planned homebirth |

| 7. Reed, Barnes and Rowe12 |

Women’s experience of birth: Childbirth as a rite of passage | Australia | Narrative approach, rites of passage theory | 5 prim 5 multi |

6 months | 6 hospital births, 4 homebirths | To explore women’s experiences of physiological childbirth |

| 8. Sjöblom et al 31 | A qualitative study of women’s experiences of home birth in Sweden | Sweden | Phenomenological– hermeneutic method. |

12 (mix of parity) | Less than 10 years | Homebirths | To illuminate the experience of giving birth at home |

prim, primipara.

Meta-synthesis analysis

Three main themes emerged: maintaining self-confidence in early labour, withdrawing within as labour intensifies and the uniqueness of the birth experience. A number of subthemes were identified within each of the three main themes, which are listed on table 2.

Table 2.

Themes, subthemes and studies contributing.

| Main themes | Subthemes | Studies |

| Maintaining self-confidence during early labour | 3 20–22 31 34 | |

| Experiencing the start of labour | 3 20–22 31 34 | |

| Sharing the beginning of labour | 3 20–22 31 34 | |

| Keeping life normal | 3 21 22 31 32 34 | |

| Withdrawing within as labour intensifies | 3 20–22 31 32 34 | |

| Accepting the intensity of labour | 3 20–22 31 32 34 | |

| Going to an inner world | 3 20–22 31 33 | |

| Coming back to push | 3 20–22 32 34 | |

| Uniqueness of the birth experience | 3 20–22 31 32 34 | |

| Reaching the glorious zenith | 3 20–22 31 32 34 | |

| Meeting the baby | 20–22 31 32 34 | |

| Empowered self | 3 20–22 31 32 34 | |

| The empowering journey of giving birth | 3 20–22 31 32 34 | |

Maintaining self-confidence in early labour

This theme presents women’s experiences when they realised that they were in labour. The accounts indicated that women knew when they were in labour and most preferred to wait calmly for progress, maintaining confidence by keeping a familiar routine and environment.

Experiencing the start of labour

Women described their feelings when they realised that they were in early labour. Some felt excited and others described a lovely feeling, comparing it to Christmas13 (p. 372). A mixture of feelings emanated from the data at this time, including excitement, happiness, calm, sometimes mixed with apprehension and anxiety.3 11 33

Women found it important to conserve their emotional strength and to maintain a positive attitude.3 11 Some described being happy with staying in their own home, and felt it was important to keep calm:

I felt confident by staying in my own living room (3, p724).

They acknowledged the close and trustful relationships in their network at that time in their life.3 13 31

Thought it was reassuring to be together with family in familiar surroundings (3, p724).

Sharing the beginning of labour

When women recognised the beginning of labour, they shared it with other women. Usually they called their mother or sister, before calling the midwife or the hospital.12 13 Few asked their midwife to be with them at this point.

At 10 o’clock in the morning I called the hospital. Of course, I had talked to my mom first (3, p274).

They indicated that it was important for them to know their midwife, because it gave them confidence and trust3 12 13 32 33

Keeping life normal

The most common behaviour at the onset of labour appeared to be continuing with the usual routine. There were many descriptions of wanting to remain at home, taking a shower, being aware of others’ needs (like older children or even pets) and waiting happily. Their own home with their relatives and partners around them3 11 33 was a tranquil place to be while their contractions were becoming more intense and the pain was increasing.3 11

I was lying all night and with my labour pains and my dog came and lay by my feet…it was an incredible feeling, it was in September, all the apples in the trees…it was all so silent… (31, p352).

Withdrawing within as labour intensifies

As the labour intensified, women withdrew into an inner world where time seemed to be suspended. Women described how this inner space allowed them to concentrate on the labouring process, and this facilitated the feeling that they could manage. The experience of control was complex and nuanced—for some, the sense of being in control was directed at making all of the decisions and for others, it was achieved by feeling safe enough to hand over control (or guardianship) to the midwife, so that they could retreat into their inner world of labouring.

Accepting the intensity of labour

When contractions became stronger and pain intensified, women felt the need to be fully focused on the physical task.13 At this point women really needed to be with safe companions in a protected place. This was the moment to contact the midwife and/or move to the hospital.

I’ve got to be somewhere where I can actually allow myself to feel what I am going through (13, p373).

The pain experience was framed by accepting pain as a natural part of childbirth, and this was important for women.3 32 Two key elements in the response to pain were trusting in the body and working with pain.3 11 Mobility was important in this phase, and women needed to move around32 or submerge themselves in water.34 The following quote is an example of how women framed the pain experience to reduce fear.

I don’t think it is explained very well what the pain is for. People just get frightened of the pain. If they could see it as something useful…the pain is there so as you can help them out, it’s not frightening at all (p58).

Women described their desire to be in control, but this was different for the individual women. For some, control meant staying on top of things and deciding what they needed, whereas for others, control was the decision to hand over management to the midwives.34

Not having any experience of labour, I needed the midwife to tell me what to do. Because she was in control I felt I was too’ (34, p33).

Women expressed their need for a caring approach.3 11 13 34 The support from midwives helped women to face the vulnerability they experienced during labour.

Knowing the midwives so well makes you feel quite at ease, if you are scared and you haven t got anyone reassuring you, you are just panicking, and it hurts a lot more (33, p239).

You are so incredibly vulnerable and I feel that you have such a need that someone is kind to you and shows you some interest. All your energy goes into giving birth to this child and you simply don’t have energy left to argue with someone or make a fuss about something. You almost have to take whatever your surroundings offer you (11, p52).

All throughout she said to me: you are coping fine, Linda; I felt assured. That was how she was making me feel calm all throughout she said to me: you are coping fine, Linda; I felt assured. That was how she was making me feel calm (33, p239).

A woman giving birth is perhaps much most sensitive or vulnerable that when she is not in labour. If for example the midwife or member of the staff hurt her in some way or says something inappropriate, then it drastically offsets your labour (11, p52)

They also described how important their partner was.

I felt he was my lifeline, he had the best analgesic effect on me and he did not leave me once (31, p. 352).

Sometimes they needed to be alone with their partners yet still able to reach their midwife whenever they needed.33 34

I felt like we were doing it ourselves, which was nice. We didn’t feel we needed the midwife all the time but she was there if we did (34, p34).

Going to an inner world

Women described how they withdrew within themselves to an inner world, where they focused on the importance of living just in that moment. Words used included ‘narrowed’, ‘zone’, ‘faraway place’, ‘another planet’ and ‘private’.11–13 31

Nothing else matters and the universe kind of shrinks to this particular, you know this particular job that you have to do which is you know about birthing your baby(13, p373).

Like with both my labours, I took myself away. I need not to have people looking at me (12, p49).

Women described perceptions of an altered or suspended sense of time.

My sense of time was completely lost, as if I had forgotten it in a drawer at home. It was a very strange feeling. There are a lot of people around you and yet you are in your own world. Even if we were in the same room we were not in the same world…’(11, p52).

Over time as the intensity of the contractions and the pain increased, women described feelings of fear and desperation.13 Some felt exhausted and deprived of energy.11 32 The thought that they could not continue any more, expressing fears of death.11

I was so optimistic in the beginning of the latter birth…I had given birth before and I survived…so that you believe you will survive. However, in both births I had this feeling for some time that I would never survive this (11, p56).

I was requesting for a caesarean, I was requesting for everything! Because I just wanted to get over with it. I just said I was going to die. At one point I felt like I was going to faint and stuff like that. I said: ‘Please Sandra, I want pain relief.’ I was actually begging her, ‘Please, please, please.’ I said, ‘I’m going to die! I won’t be able to do this! (33, p239).

Coming back to push

When starting to push, time was no longer suspended and women became more active.11 13

When I started to push, it was as if a curtain was drawn. A totally different perception, suddenly I was awake, alert and quite aware of timing’ (11, p55).

… I was at the top of the mountain when I started to push. And then I had to get down again. And that was it! (3, p725).

Uniqueness of the birth experience

With the birth of their baby women described relief, joy at meeting their baby and sense of transformation.

Reaching the glorious zenith

Directly after birth, women described feelings of pride and joy in achieving and experiencing natural childbirth.11 13 32 33

So I was brave, I was strong!… So I was like, ‘Yes, I have done it! Yes, I can do it!’ I was so happy. I honestly never had this kind of joy since I was born. I don’t know where this joy came from. I don’t know how to describe the endless joy that came in me (33, p239).

What is most prominent in the birth experience as a whole is the sense of victory, the feeling of ecstasy when the baby is born. That feeling is unique, and in the last birth I was without all medication and therefore I could enjoy this feeling much better. Well, I enjoyed it completely (11, p57).

Women described the intensity of their feelings of childbirth as being their greatest, unparalleled achievement.

It is an intense experience, a powerful life experience. It is naturally magnificent that you, just to find that you are capable of giving birth, to a child, that you can do it. To be such a perfect being that you can do it…the feeling you get when you get your new born child into your arms naturally is indescribable. It is a feeling you cannot compare with anything else. It is awe inspiring11 (p56).

Women also expressed feelings of spiritual closeness and gratitude.

I had this holiness, being close to the universe. I feel such gratitude for the possibility to give birth at home (31, p350).

Some women were also surprised and satisfied how effectively their body had taken them through the labour13 and they were proud of how they managed their pain. This ability to manage labour pain positively influenced their confidence in becoming a mother.33

I can’t really explain. I’m very pleased, very pleased, that I did it naturally. I feel so proud, full of myself. I am very proud to have him naturally. I am very proud even now.(33, p239).

However, as well as being a unique and powerful experience, some women also expressed a need for a sense of peace, and of routine to ground themselves in the new reality of motherhood.32

Meeting the baby

Women described the speed with which they assured themselves that their baby looked normal.

I remember particularly that as soon as the baby is born you think incredibly fast and you look incredibly fast whether there are, without all doubts, ten toes and ten fingers and everything that is supposed to be in place is there and many other things.11 (p56).

Women with other children were impatient for them to meet their new sibling. It was important for them to involve other family members soon after birth to share this important moment with them.32

As soon as I had the baby I’d had my bath and everything and my mum and everybody arrived…we were all in the garden with the baby (32, p58).

Women described a sense of being ‘cocooned’ within the family soon after the baby was born33 and this was expressed in the manner in which the new baby was welcomed by hugs, kisses and expressions of love.31

By three o’clock everybody had left except for just ourselves, the four of us, the whole family. We were just tucked up across my bed and I think in some ways that was the moment that felt that this is absolutely right. There’s nothing more right in the world. I was just all so peaceful. So why would do anything differently kind of feeling to it (29, p58).

The birth of the placenta was only mentioned in one study.19 For some women, it was anti-climactic after the birth of the baby, while others considered it a part of the recovery process.

Empowered self

After processing their emotions, women described feeling different. They absorbed new knowledge and understanding about themselves and incorporated this into their sense of self. They talked about their birth as an empowering experience.12

…I felt I could sense right then, when minutes passed by. I felt that I (tearful) was a little bit different (11 p56).

Women linked their pride about coping with pain to feeling strong and confident and to a positive start to new motherhood.33

When you do that as a woman, you know you can do anything … I realised how everything else in life is easy, if you can do that (enduring 70 hours of no sleep, wild contractions, etc.) you can do anything. I am sad that so many women don’t get to understand this (12, p52).

The empowering journey of giving birth

Constructing a line of argument is the next step in a meta-synthesis based on the first, second and third order interpretations. For this study, the line of argument demonstrated ‘the empowering journey of giving birth’, encompassing the various emotions, thoughts and behaviours that women experience during labour.

Women’s psychological journey originated with telling other women from their social network that labour had started, while staying cocooned in a familiar environment. Most women focused on maintaining self-confidence at the start of labour and tended to withdraw into an inner world as labour became more intense. As birth progressed, women experienced an altered state of consciousness including a change in time perception and intense feelings such as fear of dying. Women described various ways of coping with the pain and keeping control, which paradoxically, included releasing control to the midwife where appropriate. With the urge to push, women felt that once again they became alert and more active. Immediately after the baby was born, feelings of joy and pride were predominant. The journey through childbirth meant a growth in personal strength. Some women described themselves as a changed person in the sense that they felt stronger, empowered and ready to meet the demands of the newborn.

Discussion

Our study offers new insights into women’s psychological experience of physiologic childbirth as a meta-synthesis on this topic has not been previously reported. We created a model of the emerging psychological pattern of this journey that is designated in terms of emotions and behaviours. Women described birth as a challenging but predominantly positive experience that they were able to overcome with their own coping resources and the help of others. For them, this resulted in feelings of strength to face a new episode in their life with their family. Our findings confirm our main hypothesis: there is a common psychological experience of physiological labour. As far as we are aware, this has not previously been reported using women’s accounts as primary data. Our findings suggest that birth is just as much a psychological journey as a physical one.

Although the whole event does not seem to have been described before on the basis of qualitative evidence, elements of our findings are coherent with those from other studies. The preference for familiarity of environment and people at the start of birth,35 the altered state of consciousness,36 37 the different time perception,38–40 the empowerment6 41 42 and change37 43 that come with childbirth have previously been described.

In our meta-synthesis, overall women expressed confidence in their capacity to give birth and to trust in themselves and in the process, despite some apprehension as labour began, and some concerns, including fear of death, during the most intensive stages of labour. Positive perceptions of their own coping strategies and confidence in their ability to go through birth were linked to women’s positive experience of birth.44

Women’s psychological experience of physiological childbirth is strongly influenced by the people present at their birth. Women indicated that close relatives, mostly their partner and mother, as well as care providers were highly relevant for the way women experienced their birthing process. Women described the presence of their partner as the person with whom they most closely shared their experience and relied on for support, confirming that human birth is a social event.45 This is consistent with other studies that emphasised the decisive contribution partners can make to feelings of trust46 47 and the woman’s wish for a physiological birth.48

Women indicated the midwife’s presence as being critically important. At the beginning of the labour, women tended to want to be alone and at a distance from the midwife, but, as labour intensified, they wanted the midwife to be more visible and present while supporting the woman’s control, or taking control if women wanted to hand it over. Control was a key feature in our study. Over the years various researchers identified different internal and external dimensions of control.49 50 Women’s internal control includes a sense of self-control, such as thoughts, emotions, behaviours and coping with labour pain. External control is described as the woman’s involvement in what is happening during birth, understanding what care providers are doing and having an influence on the decisions. What seems important to women is not so much ‘having control’, but rather the affective component of control, which is the ‘feeling’ of having influence,10 being able to have a say in what happens and having caregivers who are responsive to expressed wishes. Women’s external control also seemed to arise from feeling that they were informed and could challenge decisions if the need arose.49

Mixed feelings, both positive and negative, were expressed regarding labour pain, and this is similar to several studies.51 Women experienced pain as meaningful in relation to their baby. They recognised its intensity but reframed it positively. This was also the case for other feelings that are usually interpreted negatively (being exhausted, feeling overwhelmed and fear of dying) that were referred to in relation to specific moments of the labour and birth, but not in the global psychological evaluation of the experience once it was over. Pain and coping with pain also contributed to gaining strength to cope with the demands of parenthood. Berentson-Shaw et al 44 indicated that stronger self-efficacy during birth explains a lower level of pain.44 Rijnders et al 52 showed that women who felt unsatisfied about their coping with pain had more negative emotions about their birth.52

What this meta-synthesis demonstrates is the enormous importance of having maternity care providers, including midwives, at the birth that are compassionate and support women to keep a sense of control that is adjusted to their personal needs and wishes. Care providers can strengthen women’s sense of coherence in offering them emotional support, stimulating trust and confidence and supporting meaningful others to be there during the birthing process. Labouring women need to be able to create a trustful bond with the midwives and obstetricians attending them that offers reassurance and enables them to feel in control. It may be that women are more likely to experience a psychologically positive physiological birth when they feel that a supportive and compassionate companion or healthcare provider (in the case of the included studies, a midwife) is by their side, and is very sensitive and attentive to their cues. This includes effective responses when the woman needs them, and simple encouragement, information or support to reassure them that what is happening to them is normal. Such support may enable women to trust that they are safe to focus inwards, which facilitates the release of hormones and enables the maternal behaviours that are essential to progress a physiological labour and birth. Midwives and other caregivers, including obstetricians, can facilitate this process by demonstrating empathy, compassion and supporting a woman’s belief in her own ability to birth. These are key skills and competencies identified in midwifery-led care, recommended to be implemented worldwide.53 These affective skills should be included in midwifery, nursing and medical education so that all caregivers have the same expertise in the emotional care of women during birth.

Most women in this synthesis indicated that, for them, birth was an enriching experience that gave them confidence in their own strength to face the challenges of motherhood. These emotions may be quite different when women are confronted with unexpected complications during childbirth, such as an emergency referral to obstetric care, an assisted vaginal birth or an unplanned caesarean section, which tend to be associated with more negative emotions.54 55 Some women experience grief following a traumatic birth (which could include a birth without interventions, especially where women feel discounted, or actively abused). This grieving may well be the mourning over the loss of the experience which contributes to feelings of empowerment.56

This study has several limitations. Close to half of the women in the sample had a home birth (39 of the 94 women). Women wishing a home birth seem to have less worries about health issues or fear of childbirth, and a greater desire for personal autonomy.57 Women planning a midwife-led birth also have lower rates of interventions which is also linked to positive experiences in birth.58

The studies included in this meta-synthesis were from high-income countries. The experiences of women in places with low-resourced maternity care systems may be different. Our sample was small and we lacked information on women’s parity, preparation for birth, specific details of supporting professionals, partners and significant others, which can be of major influence on women’s experience of childbirth.

Further research is needed in women from different cultural backgrounds. Additionally, it is of great importance to gain insight into the psychological experience of birth in women with complications during pregnancy or childbirth. As childbirth is a neurobiological event directed by neurohormones produced both by the maternal and fetal brain,7 further research needs to address the interrelationship between neurohormones, psychological experience and physiological labour and birth.59 60

Positive, physiological labour and birth can be a salutogenic event, from a mental health perspective, as well as in terms of physical well-being. The findings challenge the biomedical ‘stages of labour’ discourse and will help increase awareness of the importance of optimising physiological birth as far as possible to enhance maternal mental health. The benefits of this process can be maximised through physical, emotional and social support for women, enhancing their belief in their ability to birth and not disturbing physiology unless it is necessary.

Conclusions

Giving birth physiologically in the context of supportive, empathic caregivers, is a psychological journey that seems to generate a sense of empowerment in the transition to motherhood. The benefits of this process can be maximised through physical, emotional and social support for women, enhancing their belief in their ability to birth without disturbing physiology unless there is a compelling need. Healthcare professionals need to understand the empowering effects of the psychological experience of physiological childbirth. Further research to validate the results from this study is necessary.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors conceived and designed the study. MN and PL-W organised and conducted the search. IO, PL-W, YB, MNJ, EC-M, AS, MK, LT, MM and SSJ participated in the selection of the relevant articles. IO and EC-M performed the quality assessment of the studies. IO did the data extraction from the studies and drafted the manuscript. IO, PL-W, YB, MNJ, AS, MK, SSJ, SIK, PJH and SD interpreted the results, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and contributed to and approved the final version. MNJ, SD and PL-W supervised the project. YB, PJH, SD, MK, PL-W, MNJ and IO made the changes and corrections suggested by the reviewers.

Funding: Eu cost action is 1405 birth: Building intrapartum research through health (http://www.cost.eu/COST_Actions/isch/IS1405).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was not required for this meta-synthesis.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional unpublished data only available with authors.

References

- 1. Held V. Birth and Death. Ethics 1989;99:362:388 10.1086/293070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Simkin P. Just another day in a woman’s life? Part II: Nature and consistency of women’s long-term memories of their first birth experiences. Birth 1992;19:64–81. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.1992.tb00382.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aune I, Marit Torvik H, Selboe ST, et al. . Promoting a normal birth and a positive birth experience - Norwegian women’s perspectives. Midwifery 2015;31:721–7. 10.1016/j.midw.2015.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Elmir R, Schmied V, Wilkes L, et al. . Women’s perceptions and experiences of a traumatic birth: a meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs 2010;66:2142–53. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05391.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McKenzie-McHarg K, Ayers S, Ford E, et al. . Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: an update of current issues and recommendations for future research. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2015;33:219–37. 10.1080/02646838.2015.1031646 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Callister LC. Making meaning: women’s birth narratives. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2004;33:508–18. 10.1177/0884217504266898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buckley SJ. Executive summary of hormonal physiology of childbearing: evidence and implications for women, babies, and maternity care. J Perinat Educ 2015;24:145–53. 10.1891/1058-1243.24.3.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karlsdottir SI, Sveinsdottir H, Kristjansdottir H, et al. . Predictors of women’s positive childbirth pain experience: findings from an Icelandic national study. Women Birth 2018;31:e178–e184. 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nieuwenhuijze M, Low LK. Facilitating women’s choice in maternity care. J Clin Ethics 2013;24:276–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Meyer S. Control in childbirth: a concept analysis and synthesis. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:218–28. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beck CT. Birth trauma: in the eye of the beholder. Nurs Res 2004;53:28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thomson G, Downe S. Widening the trauma discourse: the link between childbirth and experiences of abuse. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2008;29:268–73. 10.1080/01674820802545453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sadler M, Santos MJ, Ruiz-Berdún D, et al. . Moving beyond disrespect and abuse: addressing the structural dimensions of obstetric violence. Reprod Health Matters 2016;24:47–55. 10.1016/j.rhm.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lukasse M, Schroll AM, Karro H, et al. . Prevalence of experienced abuse in healthcare and associated obstetric characteristics in six European countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015;94:508–17. 10.1111/aogs.12593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. WHO 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Declercq E, Young R, Cabral H, et al. . Is a rising cesarean delivery rate inevitable? Trends in industrialized countries, 1987 to 2007. Birth 2011;38:99–104. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00459.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Macfarlane AJ, Blondel B, Mohangoo AD, et al. . Wide differences in mode of delivery within Europe: risk-stratified analyses of aggregated routine data from the Euro-Peristat study. BJOG 2016;123:559–68. 10.1111/1471-0528.13284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Friedman E. The graphic analysis of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1954;68:1568–75. 10.1016/0002-9378(54)90311-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dixon L, Skinner J, Foureur M. Women’s perspectives of the stages and phases of labour. Midwifery 2013;29:10–17. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Halldorsdottir S, Karlsdottir SI. Journeying through labour and delivery: perceptions of women who have given birth. Midwifery 1996;12:48–61. 10.1016/S0266-6138(96)90002-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reed R, Barnes M, Rowe J. Women’s experience of birth: Childbirth as a rite of passage. Int J Childbirth 2016;6:46–56. 10.1891/2156-5287.6.1.46 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dixon L, Skinner J, Foureur M. The emotional journey of labour-women’s perspectives of the experience of labour moving towards birth. Midwifery 2014;30:371–7. 10.1016/j.midw.2013.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:59 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carroll C. Qualitative evidence synthesis to improve implementation of clinical guidelines. BMJ 2017;356:j80 10.1136/bmj.j80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Noblit G, Hare R. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park: SAGE, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010;8:336–41. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leahy-Warren P, Nieuwenhuijze M, Kazmierczak M, et al. . The psychological experience of physiological childbirth: a protocol for a systematic review of qualitative studies. Int J Childbirth 2017;7:101–9. 10.1891/2156-5287.7.2.101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. CASP. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). (Qualitative checklist). http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists (accessed Oct 2017).

- 29. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. France EF, Wells M, Lang H, et al. . Why, when and how to update a meta-ethnography qualitative synthesis. Syst Rev 2016;5:44 10.1186/s13643-016-0218-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sjöblom I, Nordström B, Edberg AK. A qualitative study of women’s experiences of home birth in Sweden. Midwifery 2006;22:348–55. 10.1016/j.midw.2005.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ng M, Sinclair M. Women’s experience of planned home birth: a phenomenological study. RCM Midwives 2002;5:56–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leap N, Sandall J, Buckland S, et al. . Journey to confidence: women’s experiences of pain in labour and relational continuity of care. J Midwifery Womens Health 2010;55:234–42. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2010.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hall SM, Holloway IM. Staying in control: women’s experiences of labour in water. Midwifery 1998;14:30–6. 10.1016/S0266-6138(98)90112-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carlsson IM. Being in a safe and thus secure place, the core of early labour: A secondary analysis in a Swedish context. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2016;11:30230–8. 10.3402/qhw.v11.30230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Machin D, Scamell M. The experience of labour: using ethnography to explore the irresistible nature of the bio-medical metaphor during labour. Midwifery 1997;13:78–84. 10.1016/S0266-6138(97)90060-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Parratt J. The impact of childbirth experiences on women’s sense of self: a review of the literature. Aust J Midwifery 2002;15:10–16. 10.1016/S1031-170X(02)80007-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Beck CT. Women’s temporal experiences during the delivery process: a phenomenological study. Int J Nurs Stud 1994;31:245–52. 10.1016/0020-7489(94)90050-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Simonds W. Watching the clock: keeping time during pregnancy, birth, and postpartum experiences. Soc Sci Med 2002;55:559–70. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00196-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maher J. Progressing through labour and delivery: birth time and women’s experiences. Womens Stud Int Forum 2008;31:129–37. 10.1016/j.wsif.2008.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Johnson TR, Callister LC, Freeborn DS, et al. . Dutch women’s perceptions of childbirth in the Netherlands. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2007;32:170–7. 10.1097/01.NMC.0000269567.09809.b5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lindgren H, Erlandsson K. Women’s experiences of empowerment in a planned home birth: a Swedish population-based study. Birth 2010;37:309–17. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00426.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lundgren I. Swedish women’s experience of childbirth 2 years after birth. Midwifery 2005;21:346–54. 10.1016/j.midw.2005.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Berentson‐Shaw J, Scott KM, Jose PE. Do self‐efficacy beliefs predict the primiparous labour and birth experience? A longitudinal study. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2009;27:357–73. 10.1080/02646830903190888 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rosenberg K, Trevathan W, Birth TW. Birth, obstetrics and human evolution. BJOG 2002;109:1199–206. 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.00010.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lundgren I, Karlsdottir SI, Bondas T. Long-term memories and experiences of childbirth in a Nordic context—a secondary analysis. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2009;4:115–28. 10.1080/17482620802423414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Howarth AM, Swain N, Treharne GJ. Taking personal responsibility for well-being increases birth satisfaction of first time mothers. J Health Psychol 2011;16:1221–30. 10.1177/1359105311403521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kringeland T, Daltveit AK, Møller A. How does preference for natural childbirth relate to the actual mode of delivery? a population-based cohort study from Norway. Birth 2010;37:21–7. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00374.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Green JM, Baston HA. Feeling in control during labor: concepts, correlates, and consequences. Birth 2003;30:235–47. 10.1046/j.1523-536X.2003.00253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ford E, Ayers S. Stressful events and support during birth: the effect on anxiety, mood and perceived control. J Anxiety Disord 2009;23:260–8. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Whitburn LY, Jones LE, Davey MA, et al. . The nature of labour pain: An updated review of the literature. Women Birth 2018. 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rijnders M, Baston H, Schönbeck Y, et al. . Perinatal factors related to negative or positive recall of birth experience in women 3 years postpartum in the Netherlands. Birth 2008;35:107–16. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00223.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, et al. . Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;4:CD004667 10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Handelzalts JE, Waldman Peyser A, Krissi H, et al. . Indications for emergency intervention, mode of delivery, and the childbirth experience. PLoS One 2017;12:e0169132 10.1371/journal.pone.0169132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Henriksen L, Grimsrud E, Schei B, et al. . Factors related to a negative birth experience - A mixed methods study. Midwifery 2017;51:33–9. 10.1016/j.midw.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bell AF, Andersson E. The birth experience and women’s postnatal depression: A systematic review. Midwifery 2016;39:112–23. 10.1016/j.midw.2016.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. van Haaren-Ten Haken T, Hendrix M, Nieuwenhuijze M, et al. . Preferred place of birth: characteristics and motives of low-risk nulliparous women in the Netherlands. Midwifery 2012;28:609–18. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Maassen MS, Hendrix MJ, Van Vugt HC, et al. . Operative deliveries in low-risk pregnancies in The Netherlands: primary versus secondary care. Birth 2008;35:277–82. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00254.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dixon L, Skinner J, Foureur M. The emotional and hormonal pathways of labour and birth: integrating mind, body and behaviour. New Zealand College of Midwives Journal 2013;48:15–23. doi:10.12784/nzcomjnl48.2013.3.15-23 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Olza-Fernández I, Marín Gabriel MA, Gil-Sanchez A, et al. . Neuroendocrinology of childbirth and mother-child attachment: the basis of an etiopathogenic model of perinatal neurobiological disorders. Front Neuroendocrinol 2014;35:459–72. 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020347supp001.pdf (166.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-020347supp002.pdf (75.6KB, pdf)