Abstract

A preclinical model of glioblastoma (GB) bystander cell therapy using human adipose mesenchymal stromal cells (hAMSCs) is used to address the issues of cell availability, quality, and feasibility of tumor cure. We show that a fast proliferating variety of hAMSCs expressing thymidine kinase (TK) has therapeutic capacity equivalent to that of TK-expressing hAMSCs and can be used in a multiple-inoculation procedure to reduce GB tumors to a chronically inhibited state. We also show that up to 25% of unmodified hAMSCs can be tolerated in the therapeutic procedure without reducing efficacy. Moreover, mimicking a clinical situation, tumor debulking previous to cell therapy inhibits GB tumor growth. To understand these striking results at a cellular level, we used a bioluminescence imaging strategy and showed that tumor-implanted therapeutic cells do not proliferate, are unaffected by GCV, and spontaneously decrease to a stable level. Moreover, using the CLARITY procedure for tridimensional visualization of fluorescent cells in transparent brains, we find therapeutic cells forming vascular-like structures that often associate with tumor cells. In vitro experiments show that therapeutic cells exposed to GCV produce cytotoxic extracellular vesicles and suggest that a similar mechanism may be responsible for the in vivo therapeutic effectiveness of TK-expressing hAMSCs.

Keywords: glioblastoma bystander therapy, clarity, transparent brain, bioluminescence, cell therapy, mesenchymal stem cell, HVS-thymidine kinase, in vivo glioblastoma model, extracellular vesicle

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GB) is a non-curable, highly aggressive, malignant brain tumor with median patient survival of 12–15 months.1 Standard therapy for newly diagnosed malignant GB begins with surgical removal of the tumor. However, in spite of major advances in surgery, the invasive and diffuse nature of GB precludes complete resection.2 Moreover, radiation and chemotherapy used to treat the remaining tumor cells are also hampered by resistance to therapy and the limited diffusion of drugs in brain tissue.3, 4 Thus, current therapies fail to cure GB, and 90% of the tumors recur close to the original site.1

The use of herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (TK) expressing human adipose mesenchymal stromal cells (hAMSCs) to deliver ganciclovir (GCV)-based bystander therapy to tumors has been widely investigated.5, 6, 7 TK catalyzes the phosphorylation of pro-drug nucleoside GCV. Incorporation of tri-phosphorylated GCV (pGCV), a thymidine analog, into nascent DNA of proliferating cells results in chain termination and DNA polymerase inhibition leading to cell death by apoptosis.8 It is currently believed that the bystander effect is mediated by the release of pGCV after the suicide of TK-expressing stem cells9 and by direct cell-to-cell transfer of the pGCV cytotoxic agent through gap junctions, because gap junction inhibitors significantly reduced bystander effect in vitro and in vivo.10, 11, 12 However, recent works have shown that inhibitors of gap junction function such as carbenoxolone also inhibit exosomal transfer to acceptor cells,13 and that gap junctional protein connexin 43-containing channels mediate the release of exosomal content into cells.14

hAMSCs are promising cellular vehicles for the delivery of bystander therapy to GB.15, 16, 17 The capacity of hAMSCs to migrate through the brain parenchyma, homing to GB, makes them effective and tumor-selective vehicles that can deliver a cytotoxic effect in the proximity of the tumor, avoiding systemic damage.18 Tumor-homing hAMSCs were found to associate with the tumor vascular system and differentiate to the endothelial lineage in the vicinity of GB stem cells, occupying a strategic position to attack the tumor.19 Moreover, TK-expressing hAMSCs plus GCV treatment of experimental tumors hinted to a dose-dependent effect that could be enhanced by serial inoculations of the therapeutic cells.20

Although current evidence from our work and that of others shows that cytotoxic hAMSCs are effective tumor-killing agents, scant evidence of cures has been provided. Moreover, although some studies show that stromal cells do not promote GB progression,18, 21 their role in other tumors as tumors and metastatic promoters22, 23, 24, 25 questioned their use as antitumor therapy in the clinic.26, 27 Thus, we initiated a systematic exploration of conditions to improve delivery of bystander therapy to orthotopic GB tumors. We found that the factors most relevant to the therapeutic outcome were: (1) the capacity to administer multiple therapeutic cell inoculations, which depends on the capacity to produce good-quality therapeutic cells in large quantities; and (2) the removal of the tumor previous to cell therapy. Both conditions improve the ratio of therapeutic cells to tumor cells during therapy.

The resulting improvement in therapeutic outcome, a chronic inhibition of tumor growth, motivated further exploration of the therapy mechanism. Using bioluminescence imaging (BLI), we demonstrated that following implantation, therapeutic cells are not affected by GCV, although their number is progressively reduced, reaching a basal level. Moreover, following GCV therapy, confocal microscope images of CLARITY-processed brain tissue revealed therapeutic cells forming part of vascular-like structures in association with tumor cells that survived pGCV cytotoxicity. These results suggested that therapeutic cells integrate into the tumor microenvironment and do not proliferate after in vivo inoculation, and are therefore not affected by pGCV. Thus, we hypothesized that bystander effect in vivo could be mediated by the release of a diffusible carrier of the cytotoxic agent, a hypothesis supported by in vitro experiments showing that the ultracentrifuge extracellular vesicle fracion (VF) from conditioned medium of TK-expressing hAMSCs treated with GCV kills tumor cells.

Results

Fast Proliferating TK-Expressing hAMSCs Effectively Kill U87 GB Cells In Vitro

The requirement of a large number of genetically modified therapeutic cells for GB therapy could be met by growth of hAMSCs in endothelial cell growth medium 2 (EGM2), a medium that induces a fast proliferating phenotype (FP-hAMSCs).28 To test the therapeutic capacity of FP-hAMSCs, hAMSCs were made luminescent, fluorescent, and cytotoxic by transduction with a tri-functional CMV:hRluc:mRFP:tTK lentiviral vector (Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs), and positively transduced RFP cells were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS). Fast proliferating cells (Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs) were obtained by cultivating Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs in EGM2 medium. Cells cultured in DMEM or EGM2 were morphologically similar and expressed similar stromal cell markers, although the FP-hAMSCs counterparts have a faster doubling time (Figures S1A and S1B). Light production, expressed in photon counts (PHCs; see the BLI and Analyses section in the Materials and Methods for more information), by both cell types was equivalent and directly proportional to the number of cells (Figure S1C). However, the BLI signal from FP-hAMSCs grew faster than that of cells cultivated in DMEM (Figures S1D and S1E).

To evaluate the toxicity of GCV on cells, tumor and therapeutic cells, alone or in co-culture, were grown in the presence of a range of GCV concentrations. U87 cells were previously transduced with a CMV:Pluc:EGFP lentiviral vector (Pluc-GFP-U87). As shown in Figure S2A, Pluc-GFP-U87 cells by themselves were not affected by concentrations of GCV below 0.02 μg/μL. However, tumor cells were effectively killed by GCV concentrations 10 times lower (0.002 μg/μL) when co-cultured with Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs (Figure S2B); a similar range of GCV concentrations was also toxic for Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs (Figure S2C).

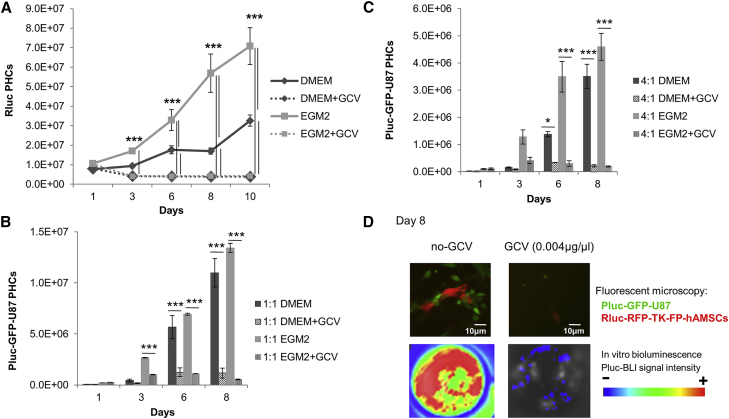

Quantification of luciferase activity by BLI showed that at 0.004 μg/μL GCV, a concentration toxic for TK-expressing therapeutic cells (Figure 1A), both Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs and Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs exerted an equivalent and pronounced bystander killing effect over co-cultured Pluc-GFP-U87 cells at all proportions tested (Figures 1B and 1C). Fluorescence microscope and BLI images of representative tissue culture wells at day 8 showed a high confluence of Pluc-GFP-U87 cells interacting with Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs, and emit high-intensity Pluc-BLI light in comparison with the cells receiving GCV (0.004 μg/μL) (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Tumor Cell Killing Capacity of Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs and Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs

(A) Graph showing the effect of GCV (0.004 μg/μL) on growth rate of Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs, cultured in DMEM, and Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs, cultured in EGM2 (n = 3 for each condition). Data are expressed as means ± SD. Significant differences were considered when ***p < 0.001 by two-way ANOVA test comparison and Bonferroni post-test. (B and C) Histograms comparing the in vitro bystander Pluc-GFP-U87 killing capacity of Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs and Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs. Cells were co-cultured at a 1:1 (B) and 4:1 (C) proportion of cytotoxic hAMSCs:Pluc-GFP-U87 cells (n = 3 for each condition). Values represent means ± SD from three independent assays. Significant differences were considered when *p < 0.5 or ***p < 0.001, respectively, by two-way ANOVA test comparison and Bonferroni post-test. (D) Representative fluorescence microscope images of Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs (red) co-cultivated during 8 days with Pluc-GFP-U87 cells (green) with and without GCV (0.004 μg/μL), and Pluc-BLI images of the corresponding tissue culture wells. Arbitrary rainbow color scale depicts light intensity (red: highest; blue: lowest) in BLI images. Microscope images were taken with a Nikon eclipse ts100 microscope equipped with the 10× objective.

Non-therapeutic FP-hAMSCs Have No Effect on Tumor Growth, and the Inclusion of up to 25% FP-hAMSCs with Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs Has No Significant Effect on Therapy

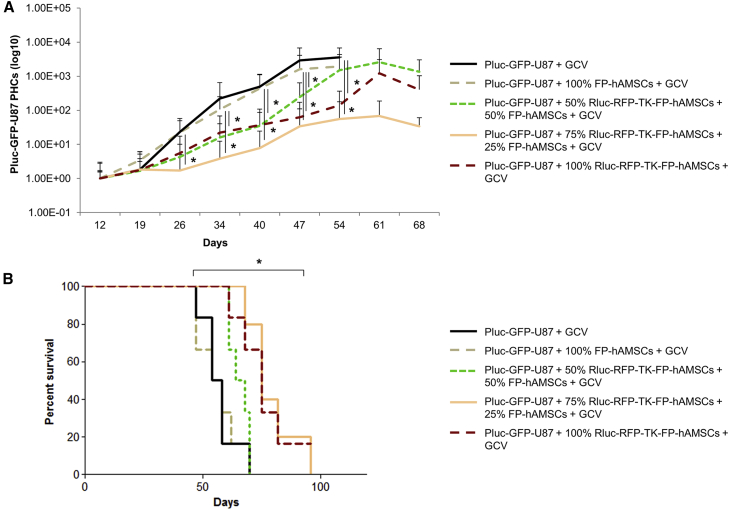

Unmodified stromal cells accompanying genetically modified therapeutic cells in large-scale productions for clinical purposes could have a positive or negative effect when implanted in tumors. To evaluate the effect of FP-hAMSCs in tumor growth and their tolerance in the therapeutic procedure, five groups of mice (n = 7 mice/group) bearing Pluc-GFP-U87 tumors were inoculated with a total of 8 × 105 cells/mouse as follows: a control group, treated with no cells; and four groups inoculated with 100% non-therapeutic FP-hAMSCs, 50%-50% or 75%-25% proportions of therapeutic cells and non-therapeutic cells, respectively, and a group treated with 100% therapeutic cells.

Ten days after tumor cell inoculation, daily i.p. GCV treatment was initiated in all groups. Non-invasive in vivo Pluc-BLI showed that tumors from control animals grew constantly, rapidly killing their hosts (median survival [MS]: 56 days) (Figures 2A and 2B). Tumors in mice inoculated with 100% non-therapeutic FP-hAMSCs showed similar tumor progression rate and survival (MS: 56 days) as control mice. However, compared with the control group, tumor progression was slower in all the animals receiving therapeutic cells in any of the tested proportions (Figure 2A). A single inoculation of 100% Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs or the inclusion of 25% non-therapeutic FP-hAMSCs resulted in a significant increase in MS to 75 days, relative to the control group. However, when the proportion of non-therapeutic FP-hAMSCs reached 50%, efficacy decreased (MS: 66 days) (Figure 2B). Statistical analysis showed significant differences between MS of control and 100% FP-hAMSCs animals, as compared with animals receiving 100% Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs or those receiving 25% non-therapeutic FP-hAMSCs.

Figure 2.

Effect of Genetically Unmodified FP-hAMSCs on Tumor Killing Capacity of Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs Preparations

(A) Graph showing Pluc-GFP-U87 tumor progression in mice treated with GCV after the inoculation of no cells, 100% unmodified FP-hAMSCs, or mixtures comprising Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs and 50%, 25%, or 0% of unmodified FP-hAMSCs. Data points represent mean ± SD of PHCs extracted from acquired images at each time point (n = 7 mice/group) normalized with respect to day 12 values. Significant differences were considered when *p < 0.05 by ANOVA test comparison adjusted by Bonferroni method. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot of animal survival throughout the treatment. Statistically significant difference was detected between control and 100% non-therapeutic FP-hAMSCs groups compared with 100% Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs group or the inclusion of 25% of non-therapeutic cells by log rank test adjusted by Bonferroni method.

Multiple Inoculations of Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs or Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs Inhibit GB Tumor Growth

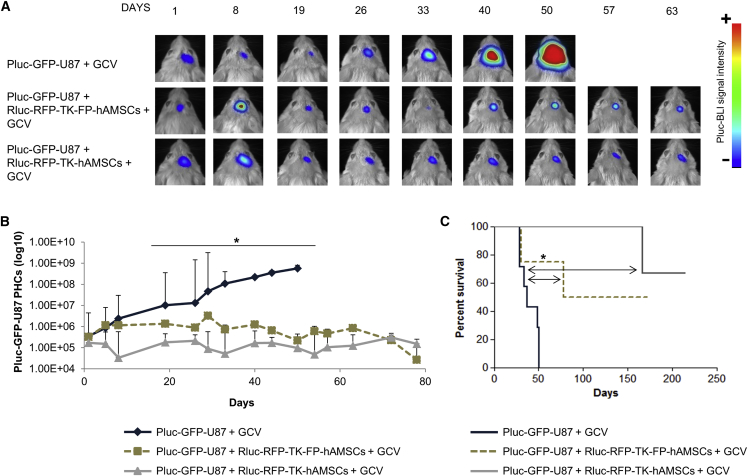

Due to their rapid proliferation capacity, TK-expressing FP-hAMSCs could be ideal candidates for tumor therapy applications based on multiple cell inoculations. To compare the therapeutic effectiveness of Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs and Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs in a multiple-inoculation procedure, a group of 24 severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice was stereotactically inoculated with 6 × 104 Pluc-GFP-U87 cells, and 6 days later with 8 × 105 Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs (n = 8) or the same number of Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs (n = 8). Control animals received tumor cells only (n = 8). Following a 10-day period of tumor development, all mice were daily intraperitoneally (i.p.) treated with 50 mg/kg GCV. Every 3 weeks, GCV treatment was interrupted during 4 days, and on the second day, mice that had initially received cells were re-implanted at the tumor site with a new dose of therapeutic cells (8 × 105) and the GCV treatment continued. Mice were weekly imaged to monitor Pluc activity. Plots of light produced by Pluc-GFP-U87 cells showed that in control animals, tumor growth increased progressively up to day 50, by which time all mice had died. However, in mice treated with either of the therapeutic cell types, light production by tumor cells remained at a significantly lower level relative to control animals, indicating that tumor growth was inhibited (Figures 3A and 3B). No significant differences were found between the two groups receiving therapeutic cells. Kaplan-Meier plots showed that cell therapy increased significantly the survival of GB-bearing mice, 50% of which survived more than 150 days (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Therapeutic Effectiveness of Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs and Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs Multiple Inoculations

(A) Representative BLI images of Pluc-GFP-U87 tumor-bearing mice: (top) control treated with GCV; (middle) treated with Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs plus GCV; (bottom) treated with Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs plus GCV (n = 8 mice/group). Therapeutic cells were intra-tumorally inoculated every 3 weeks. BLI images were superimposed on black and white images. Arbitrary rainbow color scale depicts light intensity (red: highest; blue: lowest). (B) Graph showing Pluc-GFP-U87 bioluminescence activity values recorded in BLI images. Time points represent the median ± interquartile range. Significant differences for each day data were considered when *p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA and Dunn’s multiple comparison post-test adjusted by Bonferroni method of the normalized data (log10 PHCs). (C) Kaplan-Meier plot showing animal survival throughout the experiment. Significant differences were considered when *p < 0.05 by log rank test adjusted by Bonferroni method.

Cell Therapy to Target Residual Tumor Cells after GB Tumor Debulking Improves Outcome

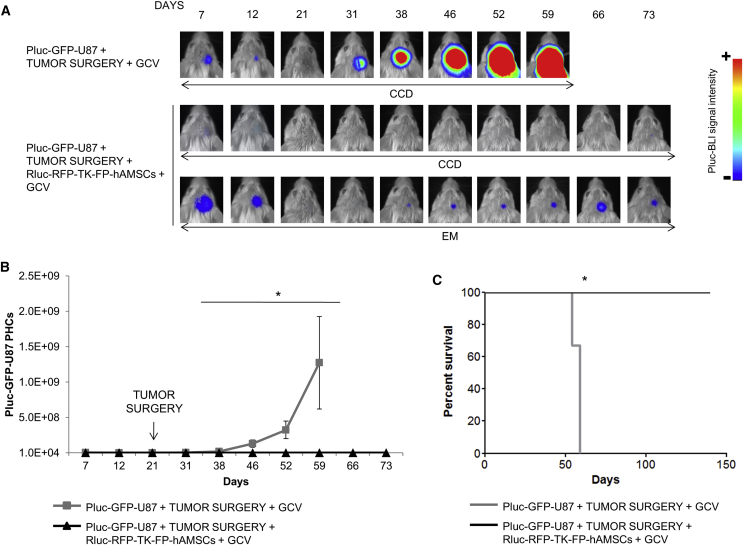

Surgical reduction of tumor size is usually one of the first stages in GB treatment. However, cells remaining in the surgical borders usually reproduce the tumors, aided by inflammation. To mimic such a clinical scenario, we developed a therapy model of U87 GB combining tumor resection plus bystander cell therapy.

A cranial window was performed in SCID mice through which, 4 days later, 6 × 104 Pluc-GFP-U87 cells were inoculated (n = 8). Twenty-one days after tumor inoculation, tumor masses were surgically removed. Tumor resection extension was monitored by in vivo Pluc-BLI, and animals were distributed in two equivalent groups (Figure S3). Half of the animals (n = 4) received in the tumor resection cavity 8 × 105 Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs suspended in human blood plasma and after 4 days received daily GCV treatment. Control animals did not receive therapeutic cells inoculation after tumor resection and were treated with GCV. As shown by in vivo BLI, in the animals only subject to tumor resection, tumor cells escaping surgery regenerated the tumors and killed their hosts by day 59 after tumor inoculation (Figures 4A–4C). However, in mice that received therapeutic cells and GCV, tumor growth was controlled and tumors were detectable by activating the electron multiplier (EM) of the charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Figures 4A and 4B). 100% of the treated animals were alive by day 139 (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Effect of Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs Cell Therapy after Tumor Debulking

Pluc-GFP-U87 brain tumors were implanted through a cranial window in SCID mice and surgically removed following a 21-day growth period. The brain cavity left by removing the tumor was filled (n = 4) or not (n = 4) with Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs in a human blood plasma matrix and subject to daily GCV treatment and weekly BLI to monitor tumor development. (A) Representative BLI images showing development of Pluc-GFP-U87 tumors. BLI images at high sensitivity (EM) from the GCV-treated mice show the presence of Pluc-GFP-U87 cells. BLI images were superimposed on black and white images of the corresponding heads. Arbitrary rainbow color scale depicts light intensity (red: highest; blue: lowest). (B) Graph summarizing PHCs recorded in regular BLI images (CCD). Data points represent the median ± interquartile range. Significant differences were considered when *p < 0.05 by two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (C) Kaplan-Meier plot showing animal survival throughout the treatment. Significant differences were considered when *p < 0.05 by log rank test.

Therapeutic Cells Migrate from Plasma Clot Implants and Interact with Tumor Cells that Escaped Resection

The encouraging outcome of combining surgical tumor removal and cell therapy suggested analyzing the behavior of therapeutic cells in plasma clots implanted in the cavity left by tumor resection.

The CLARITY procedure was used to render brain structures that have been covalently fixed to an acrylamide matrix, transparent by removal of light-dispersing lipids. This procedure allows in-depth confocal microscopy analysis of fluorescent tumor and therapeutic cells embedded in the now-invisible matrix of brain tissue.

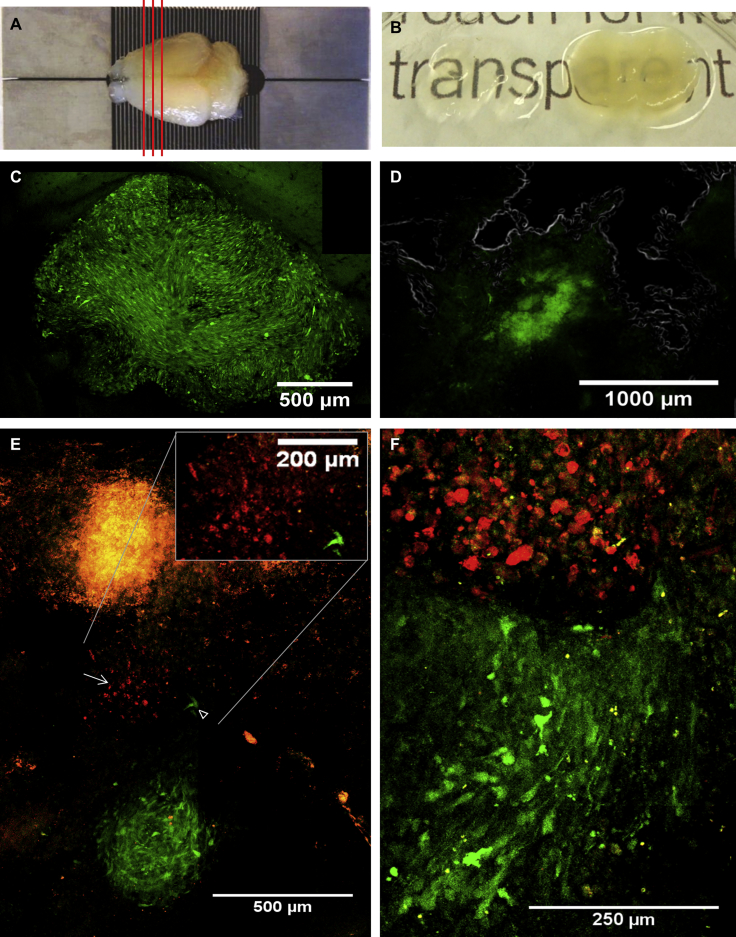

Three mice were inoculated through a cranial window with 6 × 104 Pluc-GFP-U87 tumor cells and either left untreated or treated (day 21 after tumor implantation) by either tumor debulking or tumor debulking followed by implantation in the tumor resection cavity of 8 × 105 Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs suspended in human blood plasma. On day 32 after tumor implantation, the three mice were sacrificed by perfusion with acrylamide and paraformaldehyde and the fixed brains harvested. Figure 5A shows the appearance of fixed brains and the slicing pattern in 500-μm-thick slices. Hydrogel-brain slices were subjected to CLARITY procedure to remove light-dispersing lipids obtaining transparent hydrogel-tissue samples (Figure 5B). Confocal microscopy images of the non-resected Pluc-GFP-U87 tumor revealed a spherical mass of approximately 1,500 × 1,200 μm formed by green fluorescent cells (Figure 5C), whereas in the case of the resected tumor, images showed some Pluc-GFP-U87 tumor cells that escaped tumor debulking within the irregularly shaped resection cavity (Figure 5D). Images of transparent brain slices from the mouse subject to surgery plus therapeutic cell inoculation showed a group of red fluorescent therapeutic cells that have migrated from the plasma clot and are embedded in the brain tissue (Figures 5E, top and inset) near an incipient tumor of approximately 400 μm in diameter (Figure 5E, bottom). At a different depth, an interaction front between the tumor margin and therapeutic cells can be observed and, interestingly, also tumor cells within the therapeutic cell mass (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy Analysis of CLARITY-Processed Mouse Brains

Three mice bearing fluorescent tumors, one intact and two resected tumors (day 21) that had been treated or not with Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs, were subjected to the CLARITY procedure (day 32) to render brain tissue transparent. Cleared brain slices (500 μm) were analyzed by fluorescence confocal microscopy to visualize fluorescent cells. Images were taken with a Leica SPE equipped with 10× and 20× dry objectives. The microscope images shown are maximum projections of multiple Z-scans. (A) Fixed mouse brain prepared for the CLARITY procedure and slicing pattern. (B) Image showing a brain slice before (right) and after (left) CLARITY. (C) Maximum projection of a 3D-stitching composite from a non-resected Pluc-GFP-U87 tumor (2,453 × 1,884 μm, depth: 154.9 μm). (D) Maximum projection of a 3D-stitching composite (2,556 × 2,045 μm, depth: 94.8 μm) from a resected Pluc-GFP-U87 tumor. Resection cavity borders are indicated by a gray line. Residual tumor cells are detected in the cavity (green fluorescence signal). (E and F) Images from two transparent brain slices from a mouse subjected to surgery and bystander therapy. (E) Image of the first slice generated as a 3D-stitching composition from a tissue volume of 1,319 × 2,006 μm, depth: 149.7 μm, showing an incipient and apparently organized Pluc-GFP-U87 tumor of approximately 400-μm diameter and red fluorescent therapeutics cells (→) in apparent migration between the plasma clot (top of the image) and the tumor (inset; magnification of the interaction between therapeutic and tumor cells). Some tumor cells (arrowhead) appear also in apparent migration toward therapeutic cells. (F) Image of the second slice generated by 3D-stitching composition of a tissue volume of 467 × 761 μm, depth: 40 μm, showing an interaction zone of therapeutic and tumor cells.

In Vivo Administration of GCV Does Not Kill Therapeutic Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs

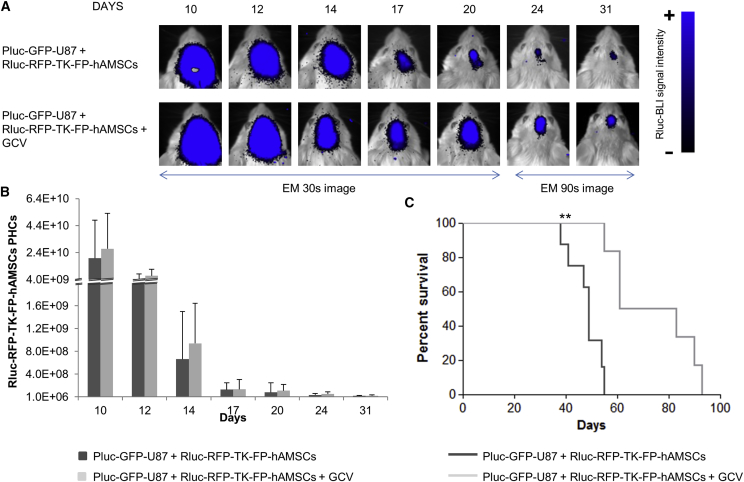

The persistence of a therapeutic effect following a single inoculation of Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs plus continuous administration of GCV suggested that in vivo therapeutic cells are not affected by the cytotoxic effects of phosphorylated GCV. With the aim of understanding the fate of therapeutic cells within the GB microenvironment, mice bearing 6-day-old tumors (6 × 104 Pluc-GFP-U87 cells) were inoculated with 8 × 105 Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs. On day 10 after tumor implantation, half of mice (n = 8) were daily i.p. treated with GCV (50 mg/kg), whereas the remaining half (n = 8) was left untreated. Mice were weekly imaged to monitor Rluc activity from therapeutic cells. BLI analysis showed that the therapeutic cell population decayed rapidly after intra-tumor implantation independently of whether they received GCV (Figures 6A and 6B). However, therapy was successful and prolonged animal survival from a median of 49 days in the control group to 72 days in GCV-treated group (Figure 6C). In a parallel test, eight tumor-free mice were implanted with Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs and half of them received GCV, whereas the other four were left untreated. Again, the Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs population decreased rapidly in the first 4 days, and cells were detectable during a 120-day period, regardless of the GCV treatment (Figures S4A and S4B).

Figure 6.

BLI Monitoring of Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs Implanted in Brain Tumors and Treated with GCV

(A) Representative BLI high-sensitivity images (EM) of light emission from Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs implanted in Pluc-GFP-U87 tumors and treated or not with GCV. The BLI images were superimposed on black and white images of the corresponding mouse heads. Arbitrary color scale depicts light intensity (blue: highest; black: lowest). (B) Graph describing the quantitative evolution of photon emission from implanted cells. Data points describe PHCs (mean ± SD) recorded in BLI images. No statistically significant difference was detected by t test. (C) Kaplan-Meier plot showing animal survival throughout the treatment. Significant differences were considered when **p < 0.01 by log-rank test.

Fate of Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs in the GB Tumor Microenvironment following GCV Treatment

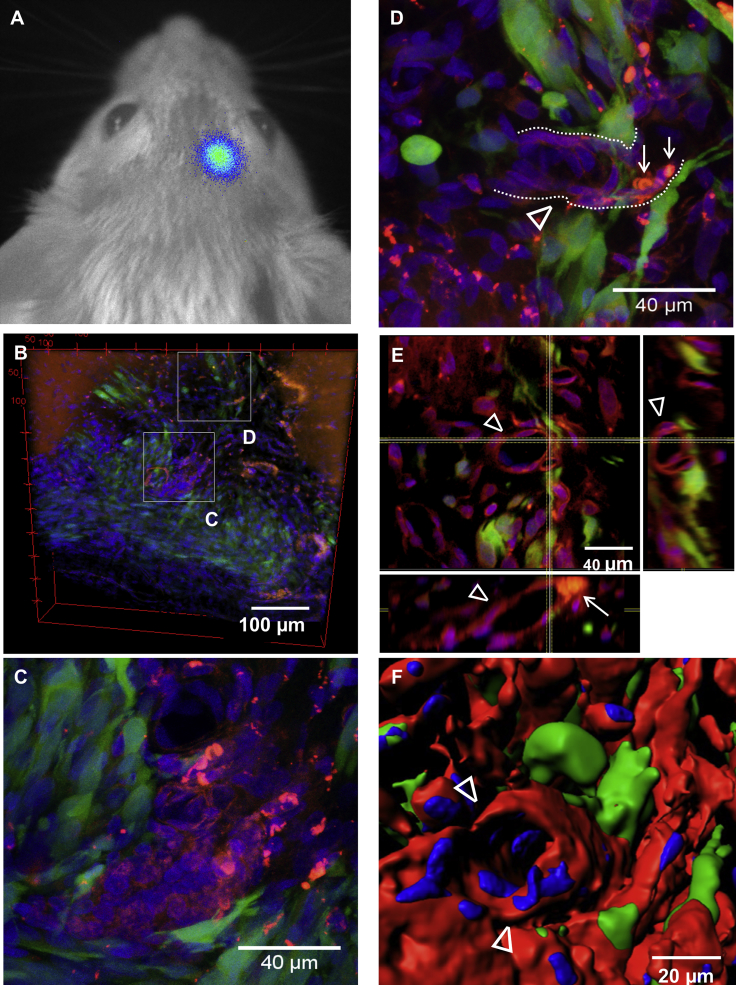

With the aim of understanding the fate of GCV-surviving therapeutic cells within the GB microenvironment, Pluc-GFP-U87 tumor-bearing animals that had received therapeutic cells (8 × 105 Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs, day 6) plus i.p. GCV (50 mg/kg, day 10) were subjected to the CLARITY procedure after 37 days of treatment. BLI analysis of Pluc activity showed the presence of therapy-resistant tumor cells that produced a low-intensity light signal similar to that of the initial tumor (Figure 7A). Thus, although bystander therapy did not completely eradicate GB tumor, it inhibited its growth. Confocal microscope images of CLARITY-processed brains with the small tumor remnants showed GFP-positive tumor cells (Figure 7B) and RFP-positive therapeutic cells either forming clusters or as part of vessel-like structures closely associated with Pluc-GFP-U87 tumor cells (Figures 7C and 7D). Orthogonal views of an amplified section of the tumor emphasize Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs vessel-like structures and their intimate association with tumor cells (Figure 7E). The tubular shape of an Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSC vessel can also be appreciated in a 3D reconstruction of the same area (Figure 7F). Furthermore, red blood cells detected in the lumen of the Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs vessel tube (Figures 7D and 7E) (also depicted as gray spherical bodies in Video S1) suggest the functionality of the vessel.

Figure 7.

Fate of Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs Implanted in Tumors Subject to GCV Treatment

Therapeutic Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs were implanted in Pluc-GFP-U87 tumors (8 × 105 Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs, day 6) and treated with i.p. GCV (50 mg/kg, day 10) during a 37-days period and subject to the CLARITY procedure. (A) Pluc-GFP-U87 cells were detectable by non-invasive in vivo BLI after 37 days of treatment. (B–F) Transparent brain slices (500 μm thick) were analyzed by Leica SPE fluorescence confocal microscopy equipped with 20× and 40× dry objectives to visualize fluorescent cells. (B) Tridimensional reconstruction of the therapy surviving green fluorescent Pluc-GFP-U87 tumor after 37 days of bystander therapy (550 × 550 μm, depth: 90 μm). Red fluorescent therapeutic Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs are found in close association with tumor cells. (C) Inset: maximum projection of a therapeutic cell node (red) surrounded by tumor cells (green) (137.5 × 137.5 μm, depth: 24 μm). (D) Inset: maximum projection of an Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs vessel-like structure (delineated by dotted lines and indicated by the arrowhead) containing red blood cells in its lumen (→), surrounded by tumor cells (137.5 × 137.5 μm, depth: 48.9 μm). (E) Orthogonal view of inset (D) showing red fluorescent cells (arrowheads) forming the blood vessel with red blood cells in its lumen (→) and tumor cells surrounding the vessel. (F) Surface intensity tridimensional reconstruction of the Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs vessel-like structure (arrowheads) in inset (D). Animated tridimensional reconstruction of the Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs vessel-like structure is also shown in Video S1.

The animation shows a tridimensional reconstruction of the vessel or tubular structure made by Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs (Figures 7D–7F) in the Pluc-GFP-U87-tumor microenvironment after 37 days of GCV treatment. The video highlights the blood-vessel appearance acquired by therapeutic cells during the bystander therapy. Raw images and 3D surface Imaris reconstruction are shown. Red blood cells found in the lumen of the tube suggest functionality of the Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs-vessel. Red blood cells were identified using 4 μm diameter and red blood cell specific fluorescent intensity thresholds.

Having found that implanted therapeutic cells form part of the tumor vascular system and kill tumor cells without committing suicide, we hypothesized that a plausible explanation to their therapeutic effectiveness could be that they exported activated GCV species toxic to neighboring cells in some form of extracellular vesicles. We found that conditioned medium and extracellular VF from TK-hAMSCs exposed to GCV inhibited Pluc-GFP-U87 cell proliferation (Figure S5A). However, conditioned medium from non-GCV pretreated Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs with or without adding GCV over Pluc-GFP-U87 cells did not modify tumor cell progression (Figure S5B). The VF presented a range of vesicle sizes of 40–170 nm and was characterized by the expression of Alix and Tsg101 exosomal markers (Figures S5C and S5D).

Discussion

We have previously shown that hAMSCs genetically modified to express TK are efficient vehicles to deliver cytotoxic therapy against the U87 human GB model in SCID mice.15, 19, 20, 29 However, although therapeutic efforts were effective at reducing tumor growth, they were rarely curative and tumors often reappeared.

In the current work, we describe how successful attempts to remediate identified weaknesses in the therapeutic model led to insights into the mechanism underlying the therapeutic process. We used BLI to monitor tumor and therapeutic cell behavior during therapy and, for the first time, applied the CLARITY procedure in combination with confocal microscopy for tridimensional analysis in transparent brain tissue of GB tumors and therapeutic cells.

Although the efficacy of our treatment system endorses the promising results of bystander therapy on other GB models,7, 30 the use of hAMSCs for tumor therapy has been questioned because of the potential for promoting tumor cell migration, stimulating invasion, and metastasis.31, 32, 33 Our current studies show that purposeful inoculation of TK-expressing therapeutic cells together with up to 25% of normal, genetically unmodified FP-hAMSCs did not negatively affect the outcome of bystander therapy. Thus, although in our standard therapy model, TK-expressing therapeutic cells were purified by cell sorting followed by expansion in culture, a slow and expensive process, the current result opens the possibility to use in clinical settings alternative, less stringent genetic modification and selection methods for the production of therapeutic cells.

Clinical applications to treat GB in patients or large animals require, besides the genetic modification of hAMSCs, prolonged expansion times and purification to eliminate potentially undesirable non-therapeutic cells, all difficult to achieve.

To avoid these limitations, we used a previously described hAMSCs type (FP-hAMSCs) that proliferates faster than hAMSCs to produce large numbers of TK-expressing therapeutic cells in a short time. This capacity improves therapy by allowing not only the application of larger cell doses, but also repeated therapeutic cell inoculations.

TK-expressing FP-hAMSCs were as effective as TK-hAMSCs at inhibiting GB growth, and multiple applications of therapeutic cells prolonged MS of animals, inducing a chronic disease state. Considering our previous observation of FP-hAMSCs phenotype reversibility,28 it is tempting to speculate that following brain implantation, FP-hAMSCs revert to the hAMSCs phenotype and exert similar anti-tumor effects.

One of the principal causes of GB therapy failure is the difficulty of killing migratory tumor cells that escape surgery in tumor borders. In a further advance to mimic such a clinical scenario, therapeutic cells suspended in a plasma clot support were inoculated in the cavity left by tumor debulking. This procedure resulted in the control of the GB disease with a single inoculation of therapeutic cells. Confocal microscope images of CLARITY-processed brains showed that the plasma clot was a good cell delivery vehicle that allowed homing of therapeutic cells toward tumor cells that had escaped resection. Autologous plasma is an entirely bio-compatible, immune-tolerated material that may also provide the necessary nutrients to support therapeutic cells until blood supply is restored.

Current and previous in vivo therapy experiments indicated that in spite of the cytotoxic effect of GCV, TK-expressing hAMSCs exerted a therapeutic effect during time periods far exceeding their expected survival. These observations suggested a complex mechanism where therapeutic cell suicide might not necessarily be the mediator of tumor cell killing.

Analysis of the fate of therapeutic cells in tumors with and without GCV treatment revealed important clues to the mechanisms underlying bystander effect. We observed that the number of implanted therapeutic cells decreases following implantation, irrespective of GCV treatment, a fact that would explain why repeated therapeutic cell implantations improve the therapeutic outcome. More surprisingly, our experiments showed that TK-expressing therapeutic hAMSCs do not commit suicide upon exposure to GCV, also a strong indication that therapeutic cells do not replicate in tumors, and become insensitive to the toxic effect of pGCV. Moreover, following prolonged treatment of tumors with therapeutic cells plus GCV, confocal microscope analysis of transparent brains showed therapeutic cells forming part of vascular-like structures that contained red blood cells and associate with tumor cells resistant to therapy, in support of a preliminary observation where therapeutic hAMSCs were shown to differentiate to the endothelial lineage.19

That few surviving therapeutic cells were effective at controlling tumor growth during prolonged time periods is a relevant finding, suggesting that they occupy strategic locations to control tumor-initiating cells.

Our results also lead to the hypothesis that TK-expressing hAMSCs exert their cytotoxic effect at a distance by secreting activated GCV species in the form of extracellular vesicles. Further support for this hypothesis was provided by in vitro experiments documenting the capacity of conditioned medium and extracellular VF from TK-hAMSCs exposed to GCV to inhibit tumor cell proliferation.

The current work provides improvements to cell-based tumor therapy and suggests ways to reduce incurable tumors to a chronic disease. Moreover, we also provide further insights on the interaction of therapeutic hAMSCs with tumors and the mechanisms underlying the stromal cell-mediated bystander cytotoxic effect, knowledge that should catalyze further improvements in cell therapy against tumors.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

hAMSCs were isolated as previously described14 from adipose tissue derived from sub-dermal liposuctions. Liposuction samples were obtained after written informed consent by anonymous donors (Dr. Roca i Noguera aesthetic surgery team). hAMSCs were grown in DMEM-hg with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma), 50 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin (Sigma), and 1 ng/mL FGF-b (PeproTech). FP-hAMSCs were cultured in EGM2 Bullet kit (Lonza) as previously described by Aguilar and colleagues.20 Human GB cells U87 (HTB-14; ATCC) were grown in DMEM/Nutrient Mixture F-12 Ham (Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS, L-glutamine, and antibiotics. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Genetically Modified Cells

Cells were labeled using lentiviral constructs CMV:hRluc:mRFP:tTK (Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs) and CMV:Pluc:EGFP (Pluc-GFP-U87). Production of viral particles was performed following standard Addgene protocol for second generation lentiviral systems and using human embryonic kidney cells 293T/17 (CRL-11268; ATCC), viral envelope plasmid (pCMV-VSVG; Addgene), and packaging construct (pCMV-dR8.2 dvrp; Addgene). Supernatant containing the virus is removed and stored at −80°C. hAMSCs and U87 cells were transduced by incubating with viral stocks using 8 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma). After 48 hr, cells were sorted using a FACSAria III (BD).

BLI and Analyses

BLI acquisition was done using high-efficiency ImagE-MX2 Hamamatsu Photonics system provided with an EM-CCD digital camera cooled at −80°C. Low-intensity images were acquired by adding the light events recorded by arrays of 4 × 4 adjacent pixels (binning 4 × 4) and activating the EM function of the CCD camera. Coelenterazine (PJK) was solubilized in NanoFuel solvent following the commercial protocol (3.33 mg/mL) and stored at −80°C. D-luciferin (Regis Technologies) stock solution was prepared at a concentration of 16.5 mg/mL in PBS and stored at −20°C.

For in vitro BLI, medium was removed from the wells, washed with PBS, and imaged immediately following addition of coelenterazine (0.1 mg/mL) or D-luciferin (1.65 mg/mL) substrate reagents. For in vivo imaging, anesthetized mice were inoculated intravenously (i.v.) with 150 μL of coelenterazine (0.1 mg/mL) in saline serum and immediately imaged, or i.p. with 150 μL of luciferin (16.5 mg/mL) and imaged 15 min after substrate injection.

Light events were calculated using the Hokawo 2.6 image analysis software from Hamamatsu Photonics Deutschland and expressed as PHCs after discounting the background of wells or animal parts without transduced cells. Colors representing standard light intensity levels were used to generate color images.

Co-culture Assays

Pluc-GFP-U87 cells were seeded in co-culture with Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs (DMEM) or Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs (EGM2 medium) in 96-well plates at 0:1, 1:1, or 4:1 therapeutic cell:tumor cell ratios. Half of the samples received GCV (0.004 μg/μL) (Cymevene; Roche). Triplicate samples of each co-culture condition were analyzed by BLI on days 1 (before starting GCV treatment), 3, 6, and 8. At day 8, cells were also visualized by fluorescent microscopy. The experiment was repeated three times.

In Vivo GB Bystander Therapy

Adult 6- to 8-week-old SCID mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratories and kept under pathogen-free conditions in laminar flow boxes. Animal maintenance and experiments were performed in accordance with established guidelines of the “Direcció General del Medi Natural” from the Catalan government. Animals were anesthetized by i.p. injections of 0.465 mg/kg xylazine (Rompum; Bayer DVM) and 1.395 mg/kg ketamine (Imalgene; Merial Laboratorios). For stereotactic cell implantation, mice were mounted in a stereotactic frame (Stoelting) and secured. A burr hole was drilled at 0.6 mm posterior (x axis) and 2 mm lateral (y axis) relative to bregma, and the cell suspension was injected at 1.5 μL/min rate using a Hamilton syringe (series 700) at a depth of 2.75 mm (z axis). The needle was slowly withdrawn after an additional 4-min wait. The scalp was closed by suture, and the animals were supplied with buprenorphine (Buprecare; Divasa-Farmavic) (0.9 μg/mL) in the drinking water. Mice were injected with 6 × 104 Pluc-GFP-U87 cells. Six days later, mice were inoculated with 8 × 105 Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs or Rluc-RFP-TK-hAMSCs, and 4 days later received daily i.p. GCV (50 mg/kg). Tumor progression was weekly analyzed by Pluc-BLI. Rluc activity was monitored by BLI to study Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs in vivo behavior. Animals were anesthetized and euthanized by cervical dislocation when signs of illness became noticeable. For multiple inoculations, GCV treatment was halted for 4 days every 3 weeks, and therapeutic cells were re-injected at the same site. Exceptionally, in some experiments, mice were injected with a percentage of non-transduced FP-hAMSCs.

Tumor Debulking

A 3-mm-diameter cranial window was made on the right side of mice. Four days later, 6 × 104 Pluc-GFP-U87 cells were stereotactically inoculated at a 1.2-mm depth in the center of the cranial window using a Hamilton syringe. Twenty-one days after tumor inoculation, tumor masses were excised from mice with the help of a binocular loupe (Leica), using a bipolar electrocautery unit (Quirumed) and an aspirator. For cell therapy, animals received 8 × 105 Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs suspended in human blood plasma in the tumor resection cavity. Four days later, treated mice received daily i.p. GCV.

3D Imaging of Tumors in Transparent Brains

Brain samples were cleared for 3D imaging following the CLARITY procedure34 with some modifications. Animals were transcardially perfused with a hydrogel solution comprising paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) (4%), acrylamide (Sigma-Aldrich) (4%), bisacrylamide (Sigma-Aldrich) (0.05%), and VA-004 Initiator (0.25%) (Wako Chemicals), following which brains were immediately isolated and kept in hydrogel solution at 4°C for 2–3 days in the dark. The tissue-containing solution was polymerized by increasing the temperature to 37°C, and the fixed brain was then thick-sectioned in 500-μm slices using a rodent brain slicer matrix and razor blades (Zivic Instruments). To obtain transparent tissue, we cleared hydrogel-brain slices by passive lipid diffusion in the dark in a solution of SDS (Sigma-Aldrich) (4%) and 200 mM boric acid (Merk) (pH 8.5) during a 4-day period, at 45°C. Transparent tissue-hydrogel slices were mounted between a 70 × 26 mm slide (StarFrost) and a 24 × 50 mm coverslip (Menzel-Gläser) in 80% glycerol-0.1 M Tris-Cl− 0.05% n-propyl-gallate (Sigma). Cell nuclei were stained using the far-red fluorescent DNA dye DRAQ7 (1:1,000) (ab109202; Abcam). The procedure allowed tridimensional microscopy analysis of intact-cleared tumor tissues at a maximum depth of approximately 200 μm using a Leica TCS-SPE confocal fluorescence microscope. Microscope images were reconstructed and analyzed using ImageJ/Fiji and Imaris softwares.

Statistical Analysis

StataSE12 software was used for the statistical analysis of BLI data. When data could be adjusted to a normal distribution or when it was susceptible to being normalized, ANOVA was used for comparison of groups larger than 2, and the p value was adjusted using the Bonferroni method for multiple comparisons. The t test was applied for two-group comparisons. Non-parametric tests were applied when data did not adjust to a normal curve distribution or were not susceptible to normalization. Tests used were the Kruskal-Wallis for more than two groups and the two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney U) for comparisons between two groups. Kaplan-Meier survival and statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 Software. Animal survival fractions were calculated using the product limit (Kaplan-Meier) method. Resulting plots were compared by the log rank (Mantel-Cox) test, adjusting significance level by the Bonferroni method for more than two groups. Statistically significant differences were considered when p < 0.05.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G., M.G.-R., N.R., and J. Blanco; Methodology, C.G.; Formal Analysis, C.G.; Investigation, C.G., M.G.-R., C.N.d.M., C.S.-B., and C.A.; Resources, L.S.-C., O.F.V., S.R.-R., and O.M.-C.; Writing – Original Draft, C.G.; Writing – Review & Editing, C.G., N.R., and J. Blanco; Visualization, C.G., N.R., and J. Blanco; Project Administration, C.G., N.R., and J. Blanco; Funding Acquisition, J. Blanco and J. Becerra.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICINN) (grant SAF2015-64927-C2-1-R), CIBER-BBN, CIBER Cardiovascular (grant CB16/11/00403), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Red Temática de Investigación Cooperativa TerCel, and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) (grant BIO2015-66266-R). The authors specially thank Dr. Josep Roca from Delfos hospital (Dr. Roca i Noguera aesthetic surgery team) for the kind donation of liposuction for hAMSCs preparation, and to the services of cell culture (Catalonian Institute for Advanced Chemistry-Spanish National Research Council [IQAC-CISC]), animal care (IQAC-CSIC), cell sorting (Scientific and Technological Centers [CCiT]-University of Barcelona), confocal microscopy (CCiT-University of Barcelona), and Central Services for Research Support (SCAI) at the University of Málaga for their technician and specialized support.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes five figures, Supplemental Materials and Methods, and one video and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2018.09.002.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Wen P.Y., Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:492–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young R.M., Jamshidi A., Davis G., Sherman J.H. Current trends in the surgical management and treatment of adult glioblastoma. Ann. Transl. Med. 2015;3:121. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.05.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sørensen M.D., Fosmark S., Hellwege S., Beier D., Kristensen B.W., Beier C.P. Chemoresistance and chemotherapy targeting stem-like cells in malignant glioma. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015;853:111–138. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-16537-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seymour T., Nowak A., Kakulas F. Targeting aggressive cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Front. Oncol. 2015;5:159. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moolten F.L. Tumor chemosensitivity conferred by inserted herpes thymidine kinase genes: paradigm for a prospective cancer control strategy. Cancer Res. 1986;46:5276–5281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Dillen I.J., Mulder N.H., Vaalburg W., de Vries E.F., Hospers G.A. Influence of the bystander effect on HSV-tk/GCV gene therapy. A review. Curr. Gene Ther. 2002;2:307–322. doi: 10.2174/1566523023347733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matuskova M., Hlubinova K., Pastorakova A., Hunakova L., Altanerova V., Altaner C., Kucerova L. HSV-tk expressing mesenchymal stem cells exert bystander effect on human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2010;290:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okura H., Smith C.A., Rutka J.T. Gene therapy for malignant glioma. Mol. Cell. Ther. 2014;2:21. doi: 10.1186/2052-8426-2-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-Quintanilla J., Bhere D., Heidari P., He D., Mahmood U., Shah K. Therapeutic efficacy and fate of bimodal engineered stem cells in malignant brain tumors. Stem Cells. 2013;31:1706–1714. doi: 10.1002/stem.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicholas T.W., Read S.B., Burrows F.J., Kruse C.A. Suicide gene therapy with Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase and ganciclovir is enhanced with connexins to improve gap junctions and bystander effects. Histol. Histopathol. 2003;18:495–507. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Touraine R.L., Vahanian N., Ramsey W.J., Blaese R.M. Enhancement of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/ganciclovir bystander effect and its antitumor efficacy in vivo by pharmacologic manipulation of gap junctions. Hum. Gene Ther. 1998;9:2385–2391. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.16-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fick J., Barker F.G., 2nd, Dazin P., Westphale E.M., Beyer E.C., Israel M.A. The extent of heterocellular communication mediated by gap junctions is predictive of bystander tumor cytotoxicity in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:11071–11075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xin H., Li Y., Buller B., Katakowski M., Zhang Y., Wang X., Shang X., Zhang Z.G., Chopp M. Exosome-mediated transfer of miR-133b from multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells to neural cells contributes to neurite outgrowth. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1556–1564. doi: 10.1002/stem.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soares A.R., Martins-Marques T., Ribeiro-Rodrigues T., Ferreira J.V., Catarino S., Pinho M.J., Zuzarte M., Isabel Anjo S., Manadas B., P G Sluijter J. Gap junctional protein Cx43 is involved in the communication between extracellular vesicles and mammalian cells. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13243. doi: 10.1038/srep13243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vilalta M., Dégano I.R., Bagó J., Aguilar E., Gambhir S.S., Rubio N., Blanco J. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells as vehicles for tumor bystander effect: a model based on bioluminescence imaging. Gene Ther. 2009;16:547–557. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porada C.D., Almeida-Porada G. Mesenchymal stem cells as therapeutics and vehicles for gene and drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010;62:1156–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altaner C., Altanerova V., Cihova M., Ondicova K., Rychly B., Baciak L., Mravec B. Complete regression of glioblastoma by mesenchymal stem cells mediated prodrug gene therapy simulating clinical therapeutic scenario. Int. J. Cancer. 2014;134:1458–1465. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasportas L.S., Kasmieh R., Wakimoto H., Hingtgen S., van de Water J.A., Mohapatra G., Figueiredo J.L., Martuza R.L., Weissleder R., Shah K. Assessment of therapeutic efficacy and fate of engineered human mesenchymal stem cells for cancer therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:4822–4827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806647106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bagó J.R., Alieva M., Soler C., Rubio N., Blanco J. Endothelial differentiation of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in glioma tumors: implications for cell-based therapy. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:1758–1766. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alieva M., Bagó J.R., Aguilar E., Soler-Botija C., Vila O.F., Molet J., Gambhir S.S., Rubio N., Blanco J. Glioblastoma therapy with cytotoxic mesenchymal stromal cells optimized by bioluminescence imaging of tumor and therapeutic cell response. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bexell D., Gunnarsson S., Tormin A., Darabi A., Gisselsson D., Roybon L., Scheding S., Bengzon J. Bone marrow multipotent mesenchymal stroma cells act as pericyte-like migratory vehicles in experimental gliomas. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:183–190. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kucerova L., Matuskova M., Hlubinova K., Altanerova V., Altaner C. Tumor cell behaviour modulation by mesenchymal stromal cells. Mol. Cancer. 2010;9:129. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki K., Sun R., Origuchi M., Kanehira M., Takahata T., Itoh J., Umezawa A., Kijima H., Fukuda S., Saijo Y. Mesenchymal stromal cells promote tumor growth through the enhancement of neovascularization. Mol. Med. 2011;17:579–587. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karnoub A.E., Dash A.B., Vo A.P., Sullivan A., Brooks M.W., Bell G.W., Richardson A.L., Polyak K., Tubo R., Weinberg R.A. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449:557–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nabha S.M., dos Santos E.B., Yamamoto H.A., Belizi A., Dong Z., Meng H., Saliganan A., Sabbota A., Bonfil R.D., Cher M.L. Bone marrow stromal cells enhance prostate cancer cell invasion through type I collagen in an MMP-12 dependent manner. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;122:2482–2490. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ridge S.M., Sullivan F.J., Glynn S.A. Mesenchymal stem cells: key players in cancer progression. Mol. Cancer. 2017;16:31. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0597-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bexell D., Svensson A., Bengzon J. Stem cell-based therapy for malignant glioma. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013;39:358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aguilar E., Bagó J.R., Soler-Botija C., Alieva M., Rigola M.A., Fuster C., Vila O.F., Rubio N., Blanco J. Fast-proliferating adipose tissue mesenchymal-stromal-like cells for therapy. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:2908–2920. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meca-Cortés O., Guerra-Rebollo M., Garrido C., Borrós S., Rubio N., Blanco J. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockin application in cell therapy: a non-viral procedure for bystander treatment of glioma in mice. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2017;8:395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amano S., Gu C., Koizumi S., Tokuyama T., Namba H. Timing of ganciclovir administration in glioma gene therapy using HSVtk gene-transduced mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2011;8:245–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strong A.L., Burow M.E., Gimble J.M., Bunnell B.A. Concise review: the obesity cancer paradigm: exploration of the interactions and crosstalk with adipose stem cells. Stem Cells. 2015;33:318–326. doi: 10.1002/stem.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belmar-Lopez C., Mendoza G., Oberg D., Burnet J., Simon C., Cervello I., Iglesias M., Ramirez J.C., Lopez-Larrubia P., Quintanilla M., Martin-Duque P. Tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells used as vehicles for anti-tumor therapy exert different in vivo effects on migration capacity and tumor growth. BMC Med. 2013;11:139. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimmerlin L., Donnenberg A.D., Rubin J.P., Basse P., Landreneau R.J., Donnenberg V.S. Regenerative therapy and cancer: in vitro and in vivo studies of the interaction between adipose-derived stem cells and breast cancer cells from clinical isolates. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2011;17:93–106. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung K., Wallace J., Kim S.Y., Kalyanasundaram S., Andalman A.S., Davidson T.J., Mirzabekov J.J., Zalocusky K.A., Mattis J., Denisin A.K. Structural and molecular interrogation of intact biological systems. Nature. 2013;497:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The animation shows a tridimensional reconstruction of the vessel or tubular structure made by Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs (Figures 7D–7F) in the Pluc-GFP-U87-tumor microenvironment after 37 days of GCV treatment. The video highlights the blood-vessel appearance acquired by therapeutic cells during the bystander therapy. Raw images and 3D surface Imaris reconstruction are shown. Red blood cells found in the lumen of the tube suggest functionality of the Rluc-RFP-TK-FP-hAMSCs-vessel. Red blood cells were identified using 4 μm diameter and red blood cell specific fluorescent intensity thresholds.