Abstract

An intergeneric hybrid was successfully developed between Oryza sativa L. (IRRI 154) and Leersia perrieri (A. Camus) Launert using embryo rescue technique in this study. A low crossability value (0.07%) implied that there was high incompatibility between the two species of the hybrid. The F1 hybrid showed intermediate phenotypic characteristics between the parents but the plant height was very short. The erect plant type resembled the female parent IRRI 154 but the leaves were similar to L. perrieri. Cytological analysis revealed highly non-homology between chromosomes of the two species as the F1 plants showed 24 univalents without any chromosome pairing. The F1 hybrid plant was further confirmed by PCR analysis using the newly designed 11 indel markers showing polymorphism between O. sativa and L. perrieri. This intergeneric hybrid will open up opportunities to transfer novel valuable traits from L. perrieri into cultivated rice.

Keywords: intergeneric hybridization, Leersia perrieri, molecular markers, out-group species, rice

Introduction

Increased demand on crop productivity to cope up with the increasing world population needs to exploit novel genetic diversity to enrich the crop genome. Modern rice cultivars are becoming more susceptible to biotic and abiotic stresses and show reduced yield (Shakiba and Eizenga 2014). Exploration of existing germplasm is essential to rice improvement and to develop new breeding strategies. It is not only limited to species closely related to the crops being improved but distantly related genera can also be tapped for breeding purposes. Distantly related species with valuable traits and good potential to increase yield are continuously being discovered and studied to be employed in crop varietal improvement programs (Zeigler 2014).

Distant hybridization has been an important strategy in rice breeding to enhance genetic variability of cultivated crops. It can either be a cross between two individuals/ species in the same genus, referred to as interspecific hybridization, or between two different genera of the same family (intergeneric hybridization). However, cross incompatibility as an isolation barrier has hindered the development of hybrids derived from wide crosses. Although the characteristic feature of both types of hybridizations is abortion of resulting embryos, interspecific hybridization is more favored and became more successful than intergeneric hybridization.

Early attempts on interspecific hybrid production have been confined using only wild species of Oryza with AA genome (Angeles-Shim et al. 2014). However, advances in biotechnology had made it possible to produce hybrids involving the secondary and tertiary gene pool of Oryza (Jena and Khush 1989, Jena et al. 1991, 2016, Jena and Nissila 2017).

The genus Oryza belongs to the tribe Oryzeae, subfamily Oryzideae of the grass family Poaceae (Brar and Singh 2011). It has 24 species in the genus two of which are cultivated and the rest are wild species (Jena 2010, Vaughan et al. 2003). Aside from Oryza, the tribe Oryzeae has other ten genera, two of which are Rhynchoryza and Leersia (Brar and Singh 2011,Vaughan 1989, 1994).

The common ancestor of Oryza and Leersia might have occurred in tropical Africa but the two genus diverged roughly 14.2 million years ago (Guo and Ge 2005). The genus Leersia is considered to be a sister genus to Oryza based on analysis of nuclear and chloroplast genes (Kellogg 2009). It is composed of 17 species that originated from Africa. One of the species is L. perrieri, which is considered to be the nearest outgroup species in the phylogenetic tree of rice (Ge et al. 2002, Jacquemin et al. 2013, Stein et al. 2018). It is usually found in the wetlands, ditches and marshlands of Africa and Madagascar (Raimondo et al. 2009). However, due to destruction of natural habitat of this plant population, this species is becoming endangered (Hutang and Gao 2017).

Several reports revealed that the species L. perrieri harbor valuable traits that can be exploited in rice breeding programs. Studies have been limited only to its evolutionary relationships to the genus Oryza (Stein et al. 2018). However, there were no extensive studies conducted to explore its morphology and traits potential to rice improvement program since it is very difficult to utilize it as a donor parent due to high incompatibility barrier with Oryza species. Screening for long term stagnant flooding conducted at IRRI revealed that L. perrieri is highly tolerant to stagnant flooding (Jena et al. unpublished).

This study is the first report on the production of an intergeneric F1 hybrid between Oryza sativa and its outgroup species L. perrieri. The F1 hybrid was confirmed using cytological analysis and genotyping. A set of L. perrieri genome specific markers confirmed the hybridity of F1.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

A high-yielding rice variety developed by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines, O. sativa L. spp. indica cv. IRRI 154 was used as the female parent and L. perrieri (IRGC 105164) as male parent to produce an intergeneric F1 hybrid. The varieties IR42 and FR13A (IRGC 122454) were used as sensitive and tolerant checks respectively for submergence tolerance screening. IRGC stands for the International Rice Genebank Collection (http://www.irgcis.irri.org:81/grc/irgcishome.html).

Intergeneric hybrid production

Intergeneric F1 hybrid production was carried out by emasculating and pollinating spikelets of the female parent IRRI 154 with pollen of L. perrieri. Pollinated spikelets were immediately bagged and sprayed two times a day for three days with 0.75 ppm of 2-4D (2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine). Fertilized spikelets after 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 days after pollination were collected for embryo rescue. Data on number of spikelets emasculated, seed set, embryos isolated, embryos cultured and hybrid plants obtained were recorded to determine the crossability between O. sativa and L. perrieri.

Tissue culture

Spikelets were collected and stored in water prior to pre-treatment to prevent dehydration. Immature spikelets were dissected and filled spikelets were treated with 20% sodium hypochlorite for 20 minutes and then washed with distilled water three times. Spikelets with intergeneric hybrid embryo were isolated in an aseptic condition under stereo microscope and cultured on a quarter strength Murashige-Skoog (MS) media with 6.0 g/L agar, then incubated in dark until shoot initiation following the method of Jena et al. (1989). Germinated embryos were transferred to light incubation room until seedlings are ready for transfer to soil.

Morphological characterization

Phenotypes including plant height, tiller number, leaf length, leaf width, panicle length, panicle branching, and spikelet morphology were measured at the flowering stage of the parents and the F1 hybrid and mean values were obtained from five plants per material. The numbers of F1 plant were increased by tiller splitting propagation from the single F1 plant. For spikelet-related traits, spikelets were dissected manually and photographs were taken under a stereomicroscope (Optika, model: SZ-CTV, Italy). Pollen fertility was measured by starch staining in a pollen grain using iodine solution (1% I2KI). After staining, the pollen grains were observed under light microscope (Olympus, model: BX53, Japan) and percentage of fully stained (dark color) pollen was calculated.

Cytological analysis

Meiotic cells of parents and hybrid were observed at the right growth stage and panicles were collected at 8:00 AM and were fixed in 3:1 (v/v) ethanol-acetic acid solution with a pinch of ferric chloride as mordant. Newly fixed samples were first incubated at room temperature for 24 hours and then stored at 4°C until use. Analyses were carried out by simple anther squash technique using 1% aceto-carmine as stain. Chromosome spreads of pollen mother cells (PMC) were observed under a light microscope (Olympus BX53) with 100× magnification in oil immersion objective and pictures were taken using Image Pro 7.0 software (Media Cybernetics, USA).

Development of DNA markers

The bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) end sequences of of L. perrieri were generated through the Oryza Map Alignment Project and Oryza Genome Evolution Project (Jacquemin et al. 2013). DNA sequence alignments between O. sativa cv Nipponbare and L. perrieri were conducted using the comparative genomics tool provided by Gramene database (www.gramene.org). Based on the sequence comparison data, one indel-sequence based marker for each of the 12 chromosomes was designed (Supplemental Table 1).

Genotype confirmation of hybrid by using PCR

Genomic DNA was isolated from leaves of both parents and F1 hybrid using a simple DNA extraction method without chloroform extraction and DNA pellet precipitation steps (Kim et al. 2016). PCR amplifications were carried out using the newly designed 12 markers and the PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 3% agarose gel. Based on the predicted PCR product sizes (Supplemental Table 1) and comparison of PCR band patterns among two parents and F1 plants, the intergeneric hybridity was confirmed.

Screening for submergence flooding of L. perrieri

Seeds of O. sativa (IRRI 154) and L. perrieri were pre-germinated for three days and then seeded in trays together with tolerant and sensitive checks and were allowed to grow for 21 days at normal condition. Number of seedlings germinated was recorded. Then, the trays containing normal seedling plants were placed in three independent 1.5 m-depth tanks for experimental replications. The tanks were slowly filled with water for providing submergence stress to the plants. Twenty-one days after submergence, water in the tank was slowly drained out. Another 21 days after desubmergence, number of seedlings survived were recorded.

Results

Production of intergeneric hybrid between O. sativa and L. perrieri

Spikelets of the intergeneric cross between IRRI 154 (O. sativa) and L. perrieri were collected after 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 days after pollination (DAP) to determine the optimum number of days required for embryo rescue with viable embryos. After pollination, swollen ovary which might have embryo ranged from 51.64 to 80.92% and the highest percentage was observed 12 DAP (Table 1). However, no embryo was observed from the 140 swollen ovaries at 12 DAP. Of the 489 spikelets containing swollen ovary at 10 DAP, only five embryos were found and the rest of spikelets had only watery ovary without development of embryo and endosperm. Finally, to obtain F1 plants, in total, 933 swollen ovaries among 1,414 pollinated spikelets were dissected under stereomicroscope and seven embryos were found (Table 2). Of the seven embryos rescued on the quarter strength MS medium, two embryos germinated. However, due to mortality of germinated embryo as the slightly developed callus turned blackish, only one embryo successfully germinated and developed to viable plant. The crossability between O. sativa and L. perrieri was 0.07% (Table 2).

Table 1.

Number of spikelets, swollen ovaries, germination of embryos produced by crossing O. sativa (IRRI 154) to L. perrieri in different days after pollination

| Days after pollination | Spikelets pollinated (no.) | Swollen ovaries | Embryos cultured (no.) | Germination of embryos | Plants obtained (no.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| (no.) | (%) | (no.) | (%) | ||||

| 8 | 111 | 74 | 66.67 | 0 | – | – | 0 |

| 9 | 213 | 110 | 51.64 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 750 | 489 | 65.2 | 5 | 2 | 40 | 1 |

| 11 | 341 | 177 | 51.91 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 173 | 140 | 80.92 | 0 | – | – | 0 |

Table 2.

Crossability between O. sativa and L. perrieri

| Generation | Spikelets pollinated (no.) | Swollen ovaries | Embryos cultured | Germination of embryos | Plants obtained (no.) | Plants obtained/total no. of spikelets | Crossability (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| (no.) | (%) | (no.) | (%) | ||||||

| F1 | 1,414 | 933 | 65.98 | 7 | 2 | 28.57 | 1 | 0.0007 | 0.07 |

Morphological characterization

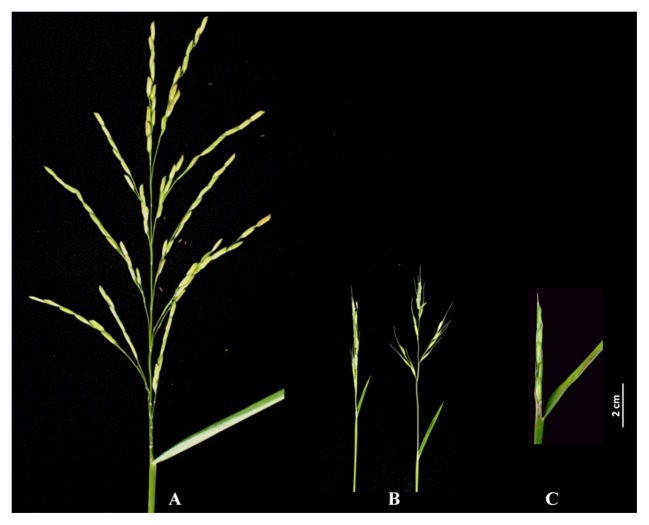

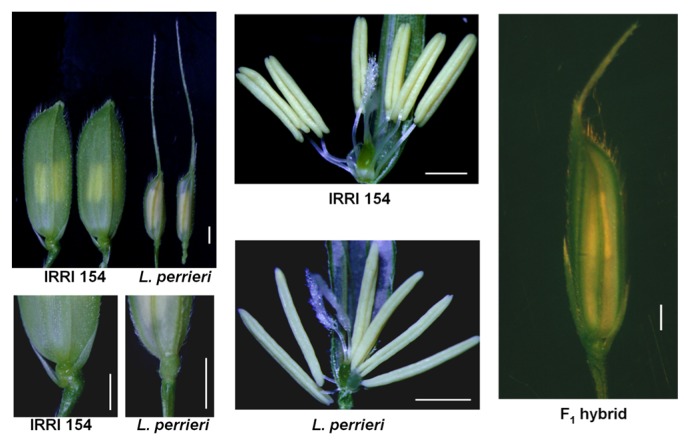

As a common modern rice cultivar, a plant of IRRI 154 variety exhibits erect stem and semi-tall plant type. In contrast, L. perrieri has a creeper type of shoot structure (Fig. 1). Overall plant phenotype of the F1 hybrid was more close to cultivated rice, O. sativa although the plant height was much smaller compared to IRRI 154 (Fig. 1). Leaf width and length of the hybrid plant was similar to those of L. perrieri. Panicle length of the hybrid was a little bit longer than L. perrieri. Panicle branching of the F1 hybrid plant was poor like L. perrieri (Fig. 2, Table 3). Spikelets of IRRI 154 had sterile lemmas but there was no awn, while L. perrieri had a long awn at the tip but absence of sterile lemmas (Fig. 3). The spikelets of the hybrid plant possessed both sterile lemmas and awn. This observation suggested that the sterile lemmas and awn on the spikelets of the hybrid plant might be inherited from IRRI 154 and L. perrieri, respectively. Pollen fertility of the F1 hybrid was observed although it was low (27.35%) compared to parents O. sativa (91.50%) and L. perrieri (86.24%) (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Plant phenotypes of the parents and F1 hybrid at the adult stage.

Fig. 2.

Panicle phenotype of IRRI 154 (A), L. perrieri (B) and F1 hybrid (C). Panicle of L. perrieri (B) is normally closed (left) and it was artificially opened for the phenotype observation (right).

Table 3.

Comparison of morphological characteristics between two parents and F1 hybrid

| Traits | O. sativa (IRRI 154) | L. perrieri (IRGC 105164) | F1 hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant height (cm) | 103.0 ± 7.5 | 41.0 ± 14.1 | 17.5 ± 2.4 |

| Tiller number | 15.2 ± 2.3 | – | 5.0 ± 1.4 |

| Leaf length (cm) | 31.6 ± 7.1 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 11.0 ± 2.5 |

| Leaf width (cm) | 1.23 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| Panicle length (cm) | 26.3 ± 6.8 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 5.5 ± 2.4 |

| Panicle branching (no.) | 12.0 ± 3.4 | 0~3 | 3.1 ± 1.1 |

| Stigma color | white | light purple | light purple |

| Plant type | erect | creeper | erect |

| Pollen fertility (%) | 91.5 ± 4.2 | 86.2 ± 7.5 | 27.4 ± 11.5 |

| Awn | − | + | + |

Fig. 3.

Spikelet morphology of IRRI 154, L. perrieri and F1 hybrid. Phenotypes were observed under stereomicroscope (Scale bar = 0.5 mm).

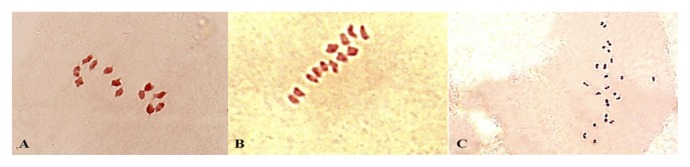

Chromosome analysis of parents and F1 hybrid

Chromosome analysis of both O. sativa and L. perrieri revealed 12 pairs of bivalents in all the pollen mother cells (PMCs) observed during meiosis stage. The F1 hybrid exhibited 24 univalents without any evidence of chromosome pairing (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Chromosome configuration at metaphase I of IRRI 154 (A), L. perrieri (B) and F1 hybrid (C) showing their chromosome numbers.

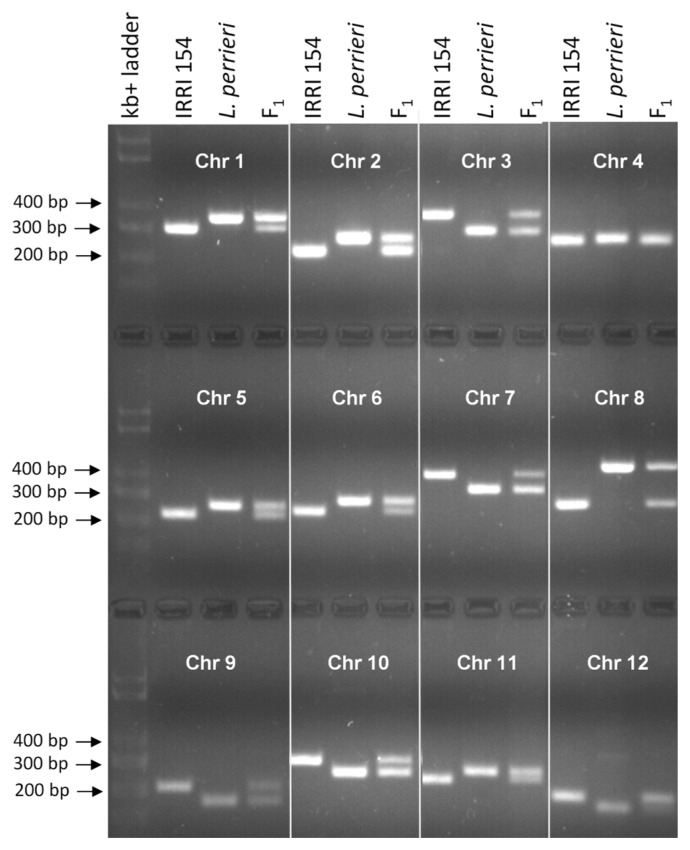

Genotype confirmation of F1 hybrid

Of the 12 putative polymorphic DNA markers between O. sativa and L. perrieri, 11 markers showed the predicted PCR band sizes and polymorphism between O. sativa and L. perrieri. In the F1 hybrid plant, all the markers of each chromosome except for chromosome 4 showed two PCR bands which were originated from the each parent allele respectively (Fig. 5). This result confirmed hybridity for the F1 plants. Monomorphic band pattern of the chromosome 4 marker (Lp04-00646) between IRRI 154 and L. perrieri might be caused by insignificant sequence difference between the parents although a sufficient indel (33 bp gap) was predicted between Nipponbare and L. perrieri (Supplemental Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Genotype confirmation of F1 hybrid using the newly designed markers for discriminating O. sativa and L. perrieri alleles.

Screening for submergence tolerance

Screening for long period (21 days) stagnant flooding was conducted to determine the response of L. perrieri and IRRI 154. During the period of submergence, L. perrieri had rapidly elongated internodes, resulting that the uppermost shoot emerged above the 1.5 m of water level and survived. In contrast, IRRI 154 plants collapsed during submergence and the plants completely died during recovery period after draining out water (Supplemental Fig. 1). All the three replications showed same results.

Discussion

Wild Oryza species as well as the nearest relatives of the genus Oryza has untapped valuable traits that can be used in rice improvement programs. Although extensive studies have been made to discover the value-added traits of wild Oryza species and were successfully utilized in rice breeding programs, the traits from distantly related genera have not been explored yet (Jena and Nissila 2017, Sanchez et al. 2014). One limitation on production of intergeneric hybrid for crop improvement includes high incompatibility between the genomes of two different genera being crossed. Reproductive barriers that restrict intergeneric hybridization to become successful may happen before or after fertilization. Pre-fertilization barriers may involve failure of pollen germination as well as pollen tube growth (Morgan et al. 2010). On the other hand, post-fertilization barriers include failure of zygote development after fertilization, degeneration of hybrid embryo, non-development of endosperm and female sterility in the hybrid plants, or even lethality of the hybrid (Kaneko and Bang 2014). This eventually results to abortion of embryos. In this study, we successfully obtained intergeneric hybrid by embryo rescue. Excision of embryo in an aseptic condition has been executed and embryo was placed on a special MS media with 1/4 strength of nutrients. It was established that the genotype, developmental stage of the embryo at excision as well as embryo culture media composition are the three main factors for the success and efficiency of embryo rescue (Jena and Khush 1989, Shen et al. 2011). In attempting embryo rescue of highly incompatible crosses, it is critical that the tissue culture process is initiated prior to the period where embryo abortion starts (Reed 2005). In this study, the optimum number of days before embryo abortion in the intergeneric cross between O. sativa and L. perrieri was 10 days after pollination took place.

Incorporating economically important genes into cultivated rice is a way of increasing genetic diversity as well as improvement of modern rice varieties to overcome the adverse effect of climate change. Currently, only interspecific hybridization has been successfully carried out between cultivated rice and wild Oryza species. Unlike other crops, rice has never been used for intergeneric hybridization. This is the first report on a successful development of a hybrid between O. sativa and L. perrieri.

The genus Oryza and Leersia diverged 14.2–15 million years ago (Guo and Ge 2005, Stein et al. 2018). In the phylogenetic tree of Oryzeae, the morphological evidence that separates Leersia to Oryza is the loss of sterile lemmas in the genus Leersia (Kellogg 2009). Very low crossability between O. sativa and L. perrieri clearly indicates that there is high incompatibility between the two species. This is expected since two parents are very distantly related and from different genera. The low percentage of seed set and resulting embryo abortion might be due to introduction of excessive exotic genetic material from L. perrieri as well as the presence of genetic imbalance leading to somatic incompatibility (Liu et al. 2005).

Although it has been established that L. perrieri has 24 chromosomes, its genome has not yet been classified clearly in relation to the other wild Oryza species. A study by Katayama (1995) observed that there were no genomic relationship between L. perrieri and O. punctata (BB genome) and O. latifolia (CCDD genome). It can be deduced that L. perrieri has no chromosome homology with the BB and CCDD genomes of Oryza. Our findings also show that L. perrieri is not even related with the AA genome since there was no chromosome association observed to the recurrent parent IRRI 154. Non-homologous chromosome pairing was observed in the F1 hybrid obtained in this study clearly (Fig. 4) suggested that the two parents are highly incompatible genetically with no chromosome associations between the species. Meiotic data observed in our study might suggest that there are no genomic relationships between L. perrieri and O. sativa, and several wild relatives in the secondary/tertiary gene pool of Oryza. Nonetheless, the likelihood of similar sets of chromosome number between O. sativa and L. perrieri indicates the potential for backcrossing to take place and fertility could be improved than that of hybrids with parents with different chromosome numbers. However, the lack of chromosome pairing usually results in little or no homologous recombination, which might be caused by large DNA blocks inherited in the progenies. These DNA blocks introgressed in the progenies sometimes contain unfavorable alleles that might be a hindrance to produce genotypes that can be employed in future breeding programs.

In the submergence experiment, L. perrieri showed dramatic internode elongation to avoid submergence stress while other O. sativa materials collapsed during submergence. In the O. sativa species, deep water rice varieties are able to escape submergence stress by using elongation mechanism because of the presence of SNORKEL1 and SNORKEL2 genes encoding single ethylene response factor (ERF) domain proteins (Hattori et al. 2009). However, the genetic factors of L. perrieri for elongation mechanism need to be studied in future which might have either superior alleles to the known genes such as SNORKEL1 and SNORKEL2 or new genes which are absent in O. sativa species. In addition to elongation mechanism, three ERF genes related to SUB1 locus conferring ‘quiescence strategy’ to submergence stress were also detected in chromosome 9 of L. perrieri (Dos Santos et al. 2017). However, our phenotype observations under submergence stress suggest that L. perrieri uses an elongation mechanism as primary submergence tolerance mechanism rather than quiescence mechanism. This particular trait can be transferred to cultivated rice once the F1 can be further backcrossed to O. sativa parent for the production of monosomic alien addition lines and disomic introgression lines. The development of these valuable materials will be able to provide an avenue of improving rice varieties in rice ecosystems that are prone to flooding.

Intergeneric hybridization is an effective method to broaden the genetic base of a cultivated crop species. It has been reported that intergeneric hybrids have been developed between yellow mustard and rapeseed (Brown et al. 1997), turnip and radish (Lou et al. 2017) and many other crops (Bang et al. 2007, D’Hont et al. 1995, Hu et al. 2002). Tissue culture is necessary to successfully obtain intergeneric hybrids. Production of intergeneric hybrids and their progenies can also be a tool to conserve valuable traits of species that are threatened to be extinct by incorporating genes into the existing gene pool of cultivated species. Rice has been used together with barley to produce an intergeneric hybrid using protoplast fusion (Kisaka et al. 1998). Intergeneric hybridization was conducted between O. sativa and Luziola peruviana but the focus of this study was to observe chromosomal aberrations and cytological alterations that exist in the intergenic hybrid (Moreno et al. 2014).

In this study, as a first step, intergeneric hybridization between O. sativa and L. perrieri was successfully carried out. To transfer DNA segments harboring valuable traits from this grass species to the cultivated rice, chromosome introgression of L. perrieri into O. sativa is an essential procedure. In the wide hybridization between different genomes, obtaining BC1 or F2 plants from the initial F1 hybrid is one of the most difficult steps. To overcome this, we will amplify the number of F1 plants using tiller splitting propagation and make the F1 plants very healthy through growth condition optimization. Furthermore, constant pollination and embryo rescue will be required to increase the possibility like obtaining F1 hybrid plants. Fortunately, our F1 hybrid showed some pollen fertility (Table 3) and this might be helpful for the production of the next generation plants. Moreover, production of these lines can be a good material to unravel the genetic mechanism of L. perrieri for its survival in stress conditions like flooding.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr. Patricio Carandang for the excellent technical assistance provided during the conduct of this study. We are grateful to CGIAR global rice science partnership program (GRiSP: Grant No. DRPC 2011-134) of IRRI for supporting this study. We thank the IRRI editorial team for editing this manuscript.

Literature Cited

- Angeles-Shim, R., Vinarao, R.B., Marathi, B. and Jena, K.K. (2014) Molecular analysis of Oryza latifolia Desv. (CCDD genome)-derived introgression lines and identification of value-added traits for rice (O. sativa L.) improvement. J. Hered. 105: 676–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang, S.W., Sugihara, K., Jeung, B.H., Kaneko, R., Satake, E., Kaneko, Y. and Matsuzawa, Y. (2007) Production and characterization of intergeneric hybrids between Brassica oleracea and a a wild relative Moricandia arvensis. Plant Breed. 126: 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Brar, D.S. and Singh, K. (2011) Oryza. In: Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources Cereals, Springer Nature, Berlin, pp. 321–365. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J., Brown, A.P., Davis, J.B. and Erickson, D. (1997) Intergeneric hybridization between Sinapis alba and Brassica napus. Euphytica 93: 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- D’Hont, A., Rao, P.S., Feldmann, P., Grivet, L., Islam-Faridi, N., Taylor, P. and Glaszmann, J.C. (1995) Identification and characterization of sugarcane intergeneric hybrids, Saccharum officinarum × Erianthus arundinaceus, with molecular markers and DNA in situ hybridization. Theor. Appl. Genet. 91: 320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, R.S., Farias, D.D.R., Pegoraro, C., Rombaldi, C.V., Fukao, T., Wing, R.A. and de Oliveira, A.C. (2017) Evolutionary analysis of the SUB1 locus across the Oryza genomes. Rice (N Y) 10: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge, S., Li, A., Lu, B.R., Zhang, S.Z. and Hong, D.Y. (2002) A phylogeny of the rice tribe Oryzeae (Poaceae) based on matK sequence data. Am. J. Bot. 89: 1967–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.L. and Ge, S. (2005) Molecular phylogeny of Oryzeae (Poaceae) based on DNA sequences from chloroplast, mitochondrial, and nuclear genome. Am. J. Bot. 92: 1548–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori, Y., Nagai, K., Furukawa, S., Song, X.J., Kawano, R., Sakakibara, H., Wu, J., Matsumoto, T., Yoshimura, A., Kitano, H.et al. (2009) The ethylene response factors SNORKEL1 and SNORKEL2 allow rice to adapt to deep water. Nature 460: 1026–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Q., Hansen, L., Laursen, J., Dixelius, C. and Andersen, S. (2002) Intergeneric hybrids between Brassica napus and Orychophragmus violaceus containing traits of agronomic importance for oilseed rape breeding. Theor. Appl. Genet. 105: 834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutang, G.R. and Gao, L.Z. (2017) The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Leersia perrieri of the rice tribe Oryzeae, Poaceae. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 9: 663–665. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemin, J., Bhatia, D., Singh, K. and Wing, R.A. (2013) The International Oryza Map Alignment Project: development of a genus-wide comparative genomics platform to help solve the 9 billion-people question. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16: 147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jena, K.K. and Khush, G.S. (1989) Monosomic alien addition lines of rice: production, morphology, cytology, and breeding behavior. Genome 32: 449–455. [Google Scholar]

- Jena, K.K., Multani, D.S. and Khush, G.S. (1991) Monosomic alien addition lines of Oryza australiensis and alien gene transfer. In: Rice Genetics II. International Rice Research Institute, Philippines, p. 728. [Google Scholar]

- Jena, K.K. (2010) The genus Oryza and transfer of useful genes from wild species into cultivated rice, O. sativa. Breed. Sci. 60: 518–523. [Google Scholar]

- Jena, K.K., Ballesfin, M.L. and Vinarao, R.B. (2016) Development of Oryza sativa L. by Oryza punctata Kotschy ex Steud. Monosomic addition lines with high value traits by interspecific hybridization. Theor. Appl. Genet. 129: 1873–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jena, K.K. and Nissila, E.A.J. (2017) Genetic improvement of rice (Oryza sativa L.). In: Genetic Improvement of Tropical Crops. Springer Nature, Berlin, pp. 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, Y. and Bang, S.W. (2014) Interspecific and intergeneric hybridization and chromosomal engineering of Brassicaceae crops. Breed. Sci. 64: 14–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg, E.A. (2009) The evolutionary history of Ehrhartoideae, Oryzeae, and Oryza. Rice 2: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.R., Yang, J., An, G. and Jena, K.K. (2016) A simple DNA preparation method for high quality polymerase chain reaction in rice. Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 4: 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kisaka, H., Kisaka, M., Kanno, A. and Kameya, T. (1998) Intergeneric somatic hybridization of rice (Oryza sativa L.) and barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) by protoplast fusion. Plant Cell Rep. 17: 362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., Xu, X. and Deng, X. (2005) Intergeneric somatic hybridization and its application to crop genetic improvement. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 82: 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, E.R., Timmerman-Vaughan, G.M., Conner, A.J., Griffin, W.B. and Pickering, R. (2010) Plant interspecific hybridization: outcomes and issues at the intersection species. In: Plant Breeding Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, pp. 161–220. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, P.E., Caetano, C.M., Olaya, C.A., Agrono, T.C. and Torres, E.A. (2014) Chromosome elimination in intergeneric hybrid of Oryza sativa × Luziola peruviana. Agric. Sci. 5: 1344–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Raimondo, D., von Staden, L., Foden, W., Victor, J.E., Helme, N.A., Turner, R.C., Kamundi, D.A. and Manyama, P.A. (2009) Red list of South African plants. Strelitzia 25 South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, p. 668. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, S.M. (2005) Embryo rescue. In: Trigiano, R.N. and Gray D.J. (eds.) Plant Development and Biotechnology. CRC Press LLC, USA, pp. 235–239. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, P.L., Wing, R.A. and Brar, D.S. (2014) The wild relatives of rice: genomes and genomics. In: Zhang, Q. and Wing R.A. (eds.) Genetics and Genomics of Rice. Plant Genetics and Genomics, New York, pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Shakiba, E. and Eizenga, G.C. (2014) Unraveling the secrets of rice wild species. In: Yan, W. and Bao J. (eds.) Rice-Germplasm, Genetics and Improvement. InTech, UK, pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X., Gmitter Jr., F.G. and Grosser, J.W. (2011) Immature embryo rescue and culture. In: Thorpe, T.A. and Yeung E.C. (eds.) Plant Embryo Culture: Methods and Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology. Humana Press, USA, pp. 75–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, J.C., Yu, Y., Copetti, D., Zwickl, D.J., Zhang, L., Zhang, C., Chougule, K., Gao, D., Iwata, A., Goicoechea, J.L.et al. (2018) Genomes of 13 domesticated and wild rice relatives highlight genetic conservation, turnover and innovation across the genus Oryza. Nat. Genet. 50: 285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, D.A. (1989) The genus Oryza L. current status of taxonomy, International Rice Research Institute, Philippines, p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, D.A. (1994) The wild relatives of rice: A Genetics Resource Handbook. International Rice Research Institute, Philippines, p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, D.A., Morishima, H. and Kadowaki, K. (2003) Diversity in the Oryza genus. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6: 139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler, R.S. (2014) Food security, climate change and genetic resources. In: Jackson, M., Ford-Lloyd B. and Parry M. (eds.) Plant genetic resources and climate change. CAB International, UK, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.