Abstract

Background

In the UK, changes to legislation in 2003 regarding the free movement of people in the European Union resulted in an increase in immigration from countries that joined the EU since 2004, the Accession countries.

Objective

To describe and compare the maternity experiences of recent migrant mothers to those who had been resident in the UK for longer, and to UK-born women, while taking into account their region of origin.

Design

Cross-sectional national survey.

Setting

England, 2009.

Participants

Random sample of postpartum women.

Measurements

Questionnaires asked about demographic characteristics, care during pregnancy, labour, birth and postnatally, about country of origin and, if not born in the UK, when they came to the UK. Country of origin was grouped into UK, Accession countries, and rest of the world. Recency of migration was grouped into recent arrivals (0–3 years), and earlier arrivals (4 or more years since arrival). Descriptive statistics and binary logistic regression were used to explore women's experiences of care. Stratified analyses were used to account for the strong correlation between recency of migration and region of origin.

Findings

Overall, 5332 women responded to the survey (a usable response rate of 54%). Seventy-nine percent of women were UK-born. Of the 21% born outside the UK, a third were born in Accession countries. All migrants reported a poorer experience of care than UK-born women. In particular, recent migrants from the Accession countries were significantly less likely to feel that they were spoken to so they could understand and treated with kindness and respect.

Conclusions

Given the rising population of non-UK-born women of childbearing age resident in the UK and the relatively high proportion from Accession countries, it is important that staff are able to communicate effectively, through interpreters if necessary.

Implications for practice

The differences in clinical practice between women's home countries and the UK should be discussed so that women's expectations of care are informed about the options available to them.

Keywords: Maternity care, Country of birth, Recency of migration, Perceptions of care

Abbreviations: UK, United Kingdom; EU, European Union; EEA, European Economic Area; MW, midwife; AN, antenatal; PN, postnatal; BME, Black and ethnic minority

Introduction

In the UK, changes to legislation in 2003 regarding the free movement of people in the European Union resulted in an increase in immigration from the A8 countries (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia), and the A2 countries (Romania and Bulgaria), which joined the European Union in 2004 and 2007 respectively (Tromans, Natamba, & Jefferie, 2009). We refer to these countries collectively as the Accession countries. In 2015, 27.5% of live births in England and Wales were to women born outside the UK (Office for National Statistics, 2016) and about a quarter (6.1% overall) of these women were born in the Accession countries. The greatest number came from Poland (Office for National Statistics, 2014), and in large cities such as London and Birmingham these proportions are far higher (Cross-Sudworth, Williams, & Herron-Marx, 2011). Two thirds of the increase in fertility in the UK between 2001 and 2007 can be attributed to births to women born outside the UK (Tromans et al., 2009) although this was principally driven by women from South Asia (Waller, Berrington, & Raymer, 2012).

While the maternity care experiences of Black and Minority Ethic (BME) women and migrants from non-European countries have been well-documented (Cross-Sudworth et al., 2011, Hayes, 1995, Henderson et al., 2013, Jomeen and Redshaw, 2013, Raleigh et al., 2010), the experience of European women born outside the UK has been relatively unexplored in this context. Local evidence suggests that women from Central and Eastern Europe may experience prejudice and poorer care than women born in the UK or North and Western Europe. Studies in Kent, Norfolk and Warrington indicate that midwives and health visitors are under-utilised by these women, that they have difficulty understanding the process and organisation of maternity care, that they don't feel listened to and they feel that their care is not sufficiently comprehensive (Eida, Not stated; Madden et al., 2014, Revill, 2016).

There is relatively little research on the effects of recency of migration on women's experience of maternity care. A systematic review of migration to western industrialised countries and perinatal health conducted in 2008 (Gagnon et al., 2009) found that migrants’ outcomes in terms of preterm birth, birthweight and health-promoting behaviour were as good as those for non-migrant women, but the authors noted that duration of residence was rarely studied. A Canadian study examined the maternity experiences of recent (five years or fewer) and less recent migrants, compared to Canadian-born women (Kingston et al., 2011). They found no statistically significant differences in perceived compassion, competence, respect or privacy shown by healthcare professionals, but more migrant women (both recent and non-recent) reported finding it difficult to see a provider for their own and their infant's care and expressed slightly less satisfaction with postpartum care. More recently, a review of factors leading to high rates of potentially preventable emergency caesarean section among migrant women in high income countries included length of time in the receiving country as one of several predictive factors (Merry et al., 2016). The review indicated that for some migrants the risk of emergency caesarean section increased with duration of residence as women adopted a less healthy lifestyle, but for others there was no effect. However, factors important for one health outcome may not apply to another (Jayaweera & Quigley, 2010).

In contrast to women born in Africa and the Indian subcontinent who tend to have higher rates of maternal and infant morbidity and mortality (Hollowell et al., 2011, Knight et al., 2009), women coming to the UK from European countries, including Accession countries, tend to have lower rates of poor outcome than UK-born women, and are more likely to have a normal birth (Gorman et al., 2014, Walsh et al., 2011). This has been partly ascribed to the ‘healthy migrant effect’ in which healthy women are more able and willing to migrate (Pendleton, 2015, Walsh et al., 2011). This may apply more to women from Europe and other high income countries for a variety of reasons including health care in the country of origin and socioeconomic differences. However, all migrant women may face difficulties in terms of unfamiliarity with the language and/or the British health service (Osipovič, 2013). In Poland, women with a normal pregnancy tend to have more screening and ultrasound scans (Morrison, 2009), and care is more commonly provided by an obstetrician rather than a midwife (Pendleton, 2015). Thus Polish women experiencing a normal pregnancy in the UK have been reported to feel that they had received sub-standard care, to have had difficulty with medical terminology, and some returned to Poland for additional scans and checks. Women with a complicated pregnancy may be even more inclined to return to their home country for further tests and reassurance (Goodwin et al., 2012, Morrison, 2009, Osipovič, 2013, Pendleton, 2015, Sime, 2014).

Two national surveys of experience of maternity care in England of women of different ethnicities found that BME women had significantly more worries about the prospect of labour and poorer experience of care throughout pregnancy, childbirth, and in the postnatal period (Henderson et al., 2013, Jomeen and Redshaw, 2013, Redshaw and Heikkila, 2011). However, in both surveys White women were considered as a single homogenous group irrespective of their country of origin. Furthermore, to our knowledge, the effect of recency of migration on perception of maternity care has not been investigated in the UK. The aim of this study was therefore to examine women's experience of maternity care by both recency of migration and region of origin.

Methods

This study used data collected in a national maternity survey in England in 2010. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) randomly selected 10,000 women aged 16 years or over from birth registrations who had delivered a live birth in October or November 2009. They were sent a letter, information leaflet, and questionnaire 12 weeks after the birth. In addition a single sentence in 18 different languages encouraged them to call a Freephone number to enable them to complete the questionnaire by interview or through an interpreter if preferred. Women were excluded if their baby had died prior to the survey. Up to three reminders were sent to non-respondents using a tailored reminder system (Redshaw & Heikkila, 2010).

The questionnaire asked about clinical events and care during pregnancy, labour and birth, and in the postnatal period, about their country of origin and, if not born in the UK, what year they came to the UK. Information about maternal age, marital status, residence in an area of deprivation, ethnicity, and country of origin were provided by ONS for the whole sample to enable comparison between women who responded to the survey and those that did not.

As there have been changes to immigration rules since 2003, particularly regarding the Accession countries, it was decided to group ONS data on country of origin into UK, Accession countries, Old (pre-enlargement) European Economic Area (EEA), and ‘rest of the world’. Women from the ‘rest of the world’ are a highly heterogeneous group included for the sake of completeness. Recency of migration was grouped into three years or fewer, four to six years, and seven years or more since coming to the UK. These cut-offs were a pragmatic choice informed by the distribution of time since arrival while allowing sufficient sample size in each group for analysis. For the purposes of this study women with multiple births were excluded as they would have a different care pathway. Analyses were weighted by age to take account of differences in response rate (Redshaw & Heikkila, 2010). Descriptive analyses were carried out comparing sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and reported experiences of care across the ‘recency of migration groups’. Chi-square tests were used to assess associations between recency of migration and each of the variables. Although the relatively small sample size means that statistical significance should be interpreted with caution, a p value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of a significant association, and identified variables to be included in the multivariable models. To explore the effects of recency of migration and region of origin which are highly correlated, duration of residence was further aggregated to achieve greater numerical stability (three years or fewer, and four or more years since arriving in the UK, compared to UK-born women), and within that, due to small numbers, region of origin groups were further aggregated (into UK, Accession countries and Rest of the world (now also including Old EEA)). Using these categories, binary logistic regression was used to examine their effects on women's perceptions of their care. These analyses were adjusted for maternal age, parity and Index of Multiple Deprivation, an area based measure providing an overall relative indicator of deprivation. Missing data was generally less than 5% so a complete case analysis was carried out. All analyses were conducted using STATA 13 SE.

The original survey evaluating maternity services in England was passed by the Trent Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (06/MREC/16).

Results

Overall, 5332 women responded to the survey representing a response rate of 54% after exclusion of undeliverable questionnaires. Comparison with non-respondents indicated that respondents were significantly more likely to be older, to be married, to be living in the least deprived areas and to be born in the UK (Redshaw & Heikkila, 2010). A total of 11.5% were living as single parents at the time of the survey, 85.7% of responders were White and 78.7% were born in the UK. Supplementary file, Table A shows the countries in which respondents were born, excluding multiple births. Poland represented the biggest single country of origin outside the UK. However, two thirds of migrants who stated a country of origin outside the UK came from outside the EEA, principally India and African countries.

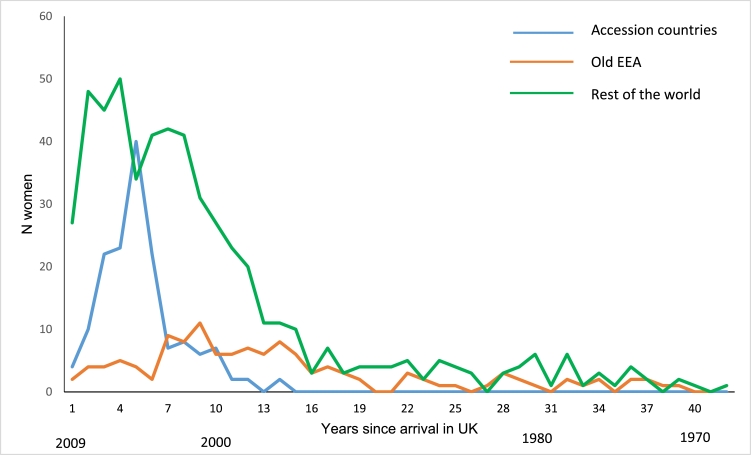

Table 1 and Fig. 1 show the strong association (p < 0.001) between recency of migration and region of origin. Whilst in each recency of migration category the majority of migrants came from outside the EEA, migrants from Accession countries came to the UK more recently than others, only 22% had arrived seven or more years before having the baby in this survey compared to 83% of Old EEA and 55% of non-EEA migrants. A small proportion of non-Accession country migrants arrived in the UK as children.

Table 1.

Association between recency of migration and region of origin.

| Recency of migration |

Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 years or fewer |

4 to 6 years |

7 or more years |

Not stated | |||||

| N | row % | N | row % | N | row % | N | ||

| Accession countries | 36 | 23.2 | 85 | 54.8 | 34 | 21.9 | 155 | 39 |

| Old EEA | 10 | 7.9 | 11 | 8.7 | 105 | 83.3 | 126 | 43 |

| Rest of the world | 120 | 22.2 | 125 | 23.2 | 295 | 54.6 | 540 | 224 |

| Total | 166 | 20.2 | 221 | 26.9 | 434 | 52.9 | 821 | 306 |

Fig. 1.

Numbers of women coming from various regions over time.

The demographic characteristics of migrants compared to UK-born women are shown in Table 2 split by both recency of migration (0–3 years compared to 4 or more years) and region of origin (Accession countries compared to the rest of the world), compared to UK-born women. Women who arrived in the UK four or more years before having the baby in this survey were significantly older than those who had arrived more recently or UK-born women, were less likely to be teenagers (<3% compared to 6% in UK-born women and 5.6% in England and Wales overall in 2009 (Office for National Statistics, 2016)), and significantly less likely to be primiparous than UK-born women or recent migrants. The proportion of non-UK-born women who left full-time education aged over 18 years was almost twice that of UK-born women. However, migrants, especially those who were recently arrived, were significantly more likely to live in an area of deprivation. There were also differences by region of origin. Women born in Accession countries tended to be younger, a higher proportion were primiparous, they were more educated, and they were less likely to live in an area of deprivation than women born in the rest of the world.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of women and their babies by recency of migration and region of origin compared to UK-born women.

| UK-born |

Recency of migration 3 years or fewer |

Recency of migration 4 years or more |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All |

Born in Accession countries |

Born in rest of world |

All |

Born in Accession countries |

Born in rest of world |

|||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||||||||||

| Maternal age (years)⁎⁎⁎ | ||||||||||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 29.2 (29.0, 29.4) | 28.1 (27.4, 28.9) | 26.5 (25.4, 27.4) | 28.6 (27.7, 29.5) | 31.2 (30.7, 31.6) | 28.6 (27.7, 29.5) | 31.8 (31.3, 32.3) | |||||||

| Missing = 62 | ||||||||||||||

| Primiparous⁎⁎⁎ | 2146 | 52.7 | 117 | 71.8 | 29 | 80.2 | 88 | 69.4 | 290 | 48.1 | 82 | 70.7 | 207 | 42.7 |

| Missing = 114 | ||||||||||||||

| Mother left full-time education aged > 18 years⁎⁎⁎ | ||||||||||||||

| Missing = 91 | 1692 | 41.2 | 138 | 81.5 | 33 | 81.5 | 105 | 81.5 | 449 | 74.3 | 99 | 83.7 | 350 | 72.0 |

| Index of multiple deprivation (quintiles)⁎⁎⁎ | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 836 | 20.2 | 15 | 8.5 | 2 | 4.8 | 13 | 9.6 | 85 | 13.8 | 14 | 12.2 | 70 | 14.2 |

| 2 | 835 | 20.2 | 17 | 9.8 | 4 | 8.9 | 13 | 10.1 | 80 | 13.0 | 13 | 10.6 | 67 | 13.5 |

| 3 | 895 | 21.6 | 37 | 21.2 | 12 | 29.6 | 25 | 18.7 | 116 | 18.9 | 28 | 23.5 | 88 | 17.8 |

| 4 | 779 | 18.8 | 34 | 19.5 | 8 | 20.6 | 26 | 19.2 | 152 | 24.7 | 36 | 30.5 | 116 | 23.3 |

| 5 (most deprived) | 796 | 19.2 | 71 | 41.0 | 14 | 36.1 | 57 | 42.5 | 183 | 29.7 | 28 | 23.2 | 155 | 31.3 |

| Total | 4140 | 100 | 173 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 133 | 100 | 616 | 100 | 118 | 100 | 497 | 100 |

| Missing = 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||||||||||

| Booking appointment before 10 weeks⁎⁎⁎ | ||||||||||||||

| (Missing = 232) | 2587 | 65.0 | 82 | 50.1 | 20 | 50.2 | 62 | 50.1 | 298 | 51.5 | 60 | 57.2 | 238 | 50.3 |

| Total antenatal checks⁎⁎⁎ | ||||||||||||||

| 1–7 | 1335 | 33.5 | 55 | 34.5 | 7 | 18.8 | 48 | 39.1 | 223 | 39.5 | 39 | 35.8 | 184 | 40.4 |

| 8–10 | 1293 | 32.4 | 41 | 25.7 | 10 | 27.0 | 31 | 25.3 | 204 | 36.1 | 46 | 42.2 | 158 | 34.6 |

| 11 or more | 1362 | 34.1 | 63 | 39.8 | 20 | 54.2 | 44 | 35.6 | 138 | 24.4 | 24 | 22.0 | 114 | 25.0 |

| Total (Missing = 243) | 3989 | 100 | 159 | 100 | 36 | 100 | 123 | 100 | 565 | 100 | 108 | 100 | 456 | 100 |

| Long term health problem | ||||||||||||||

| (Missing = 67) | 365 | 8.9 | 8 | 4.7 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 6.2 | 61 | 10.1 | 9 | 7.5 | 53 | 10.8 |

| Specific pregnancy-related problems affecting baby⁎⁎⁎ | ||||||||||||||

| (Missing = 168) | 1020 | 25.4 | 21 | 12.8 | 4 | 10.7 | 17 | 13.4 | 112 | 18.7 | 20 | 16.7 | 93 | 19.2 |

| Induction of labour (Missing = 332) | 877 | 22.3 | 43 | 24.7 | 9 | 21.3 | 34 | 25.8 | 124 | 20.1 | 26 | 22.0 | 98 | 19.7 |

| Continuous monitoring of labour*(Missing = 66) | 1823 | 44.4 | 79 | 46.0 | 10 | 26.1 | 69 | 52.0 | 257 | 41.8 | 43 | 36.1 | 214 | 43.1 |

| Type of delivery⁎⁎⁎ | ||||||||||||||

| Normal vaginal delivery | 2651 | 64.8 | 102 | 61.6 | 32 | 81.0 | 70 | 55.4 | 374 | 62.4 | 66 | 57.4 | 308 | 63.5 |

| Caesarean | 903 | 22.1 | 41 | 24.9 | 2 | 4.8 | 39 | 31.3 | 165 | 27.6 | 28 | 24.2 | 137 | 28.3 |

| Instrumental delivery | 535 | 13.1 | 22 | 13.5 | 6 | 14.1 | 17 | 13.3 | 61 | 10.1 | 21 | 18.3 | 39 | 8.1 |

| Total (Missing = 94) | 4088 | 100 | 166 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 126 | 100 | 600 | 100 | 116 | 100 | 484 | 100 |

| Low birthweight (Missing = 216) | 200 | 5.0 | 5 | 3.1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4.1 | 30 | 5.1 | 2 | 1.7 | 28 | 6.0 |

| Preterm*(Missing = 60) | 240 | 5.9 | 14 | 8.4 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 10.9 | 33 | 5.5 | 3 | 2.6 | 30 | 6.1 |

| PN length of stay > 1 day⁎⁎(Missing = 414) | 2000 | 52.2 | 97 | 60.3 | 21 | 56.9 | 76 | 61.3 | 333 | 59.3 | 59 | 53.3 | 274 | 60.8 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding first few days⁎⁎⁎(Missing = 76) | 2435 | 59.5 | 126 | 73.6 | 32 | 81.0 | 94 | 71.3 | 405 | 66.5 | 90 | 75.7 | 315 | 64.3 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding at 3 mths⁎⁎⁎(Missing = 53) | 1079 | 26.2 | 80 | 46.6 | 21 | 52.3 | 59 | 44.9 | 257 | 42.1 | 60 | 51.8 | 197 | 39.8 |

| PN saw MW at home > 3 times⁎⁎(Missing = 105) | 1929 | 47.3 | 77 | 46.2 | 22 | 54.6 | 55 | 43.5 | 238 | 39.1 | 39 | 32.8 | 199 | 40.6 |

| Baby aged > 10 days when last saw MW⁎⁎⁎(Missing = 448) | 2290 | 59.9 | 125 | 80.0 | 31 | 82.9 | 93 | 79.0 | 364 | 65.0 | 70 | 68.2 | 293 | 64.2 |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001 in chi-square test

MW midwife; PN postnatal

Some of the key clinical characteristics of women are also shown in Table 2. Recency of migration and region of origin made no significant difference to the number of women reporting long-term medical problems, induction of labour, or low birthweight. However, compared to UK-born women, all migrants were significantly less likely to have their booking appointment by 10 weeks’ gestation, rates of pregnancy-related problems, such as hypertension, were lower in all migrant groups than UK-born women, but recent migrants from Accession countries had more antenatal checks than other women (54% compared to 34% of UK-born women had 11 or more checks). Recent migrants from Accession countries were more likely to have a normal delivery (81% compared to 65% of the UK-born women) but recent migrants from the rest of the world were more likely to deliver by caesarean section (31% compared to 22% in UK-born women), and more likely to have a preterm birth (10.9% compared to 5.9% in UK-born women). The proportion of women who stayed in hospital longer than one day after the birth, and the proportion exclusively breastfeeding were higher in all migrant groups compared to UK-born women. These proportions declined with increasing duration of residence in the UK. Interestingly, the proportion of women who saw their midwife beyond 10 days postpartum was higher for all migrants, especially recent arrivals, compared to UK-born women.

Binary logistic regression was undertaken to assess the effects of recency of migration on perceptions of care. Analyses are presented by recency of migration group, and then stratified by region of origin. Table 3 shows proportions, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals unadjusted and adjusted for age, parity and Index of Multiple Deprivation for selected key variables. Overall, the majority of women had a positive view of their care. Over 80% of migrant women felt that they were spoken to so that they could understand, and over 70% felt that they were treated with respect and kindness at all stages of care. However, compared to UK-born women, all migrants were more critical of their care at each stage. Recent migrants, especially from Accession countries, were less likely to feel that they were spoken to so they could understand and be treated with kindness and respect at all stages of care, significantly so for intrapartum care. However, earlier migrant women were significantly more likely to report that staff communication during labour and birth was less than ‘very good’, to not always have confidence and trust in staff during labour, and to be left alone during labour or shortly after the birth when it worried them. Overall satisfaction with care was lower in all migrant groups at each stage, especially during labour and birth, compared to UK-born women (OR for recent migrants from Accession countries feeling very satisfied with care during labour and birth 0.46 (95% CI 0.22, 0.93)).

Table 3.

Logistic regression showing women's experiences of care, by recency of migration, stratified by region of origin.

| UK | Resident 3 years or fewer |

Resident 4 years or more |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Accession countries | Rest of world | All | Accession countries | Rest of world | |||

| Total N (% of total sample) | 4108 (83.3) | 166 (3.3) | 36 (0.7) | 130 (2.6) | 655 (13.3) | 119 (2.4) | 536 (10.9) | |

| Antenatal care | ||||||||

| MWs spoke so they could be understood | ||||||||

| N (% of group)⁎⁎ | 4105 (97.2) | 157 (94.7) | 37 (91.8) | 120 (95.7) | 576 (94.3) | 108 (92.8) | 468 (94.6) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.51 (0.24, 1.08) | 0.32 (0.09, 1.08) | 0.63 (0.25, 1.60) | 0.47 (0.31, 0.70 | 0.37 (0.16, 0.82) | 0.50 (0.32, 0.78) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | 1 | 0.52 (0.25, 1.11) | 0.36 (0.10, 1.25) | 0.62 (0.25, 1.56) | 0.39 (0.26, 0.58) | 0.39 (0.18, 0.87) | 0.39 (0.25, 0.61) | |

| MWs kind & respectful | ||||||||

| N (%)⁎⁎⁎ | 3875 (94.4) | 148 (89.7) | 30 (76.1) | 117 (94.0) | 538 (88.4) | 93 (81.1) | 445 (90.1) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.52 (0.30, 0.89) | 0.19 (0.08, 0.42) | 0.94 (0.45, 1.96) | 0.45 (0.34, 0.61) | 0.26 (0.15, 0.43) | 0.54 (0.39, 0.75) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | 1 | 0.51 (0.29, 0.89) | 0.19 (0.08, 0.43) | 0.92 (0.43, 1.94) | 0.42 (0.31, 0.57) | 0.28 (0.17, 0.48) | 0.49 (0.35, 0.68) | |

| Overall, very satisfied with AN care | ||||||||

| N (%)⁎⁎⁎ | 2048 (49.9) | 71 (41.5) | 13 (32.8) | 58 (44.1) | 245 (40.1) | 39 (33.1) | 206 (41.7) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.71 (0.52, 0.98) | 0.49 (0.24, 0.99) | 0.79 (0.55, 1.14) | 0.67 (0.57, 0.80) | 0.50 (0.33, 0.74) | 0.72 (0.60, 0.87) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | 1 | 0.78 (0.56, 1.09) | 0.60 (0.29, 1.25) | 0.84 (0.58, 1.21) | 0.64 (0.54, 0.76) | 0.48 (0.32, 0.73) | 0.69 (0.57.0.83) | |

| Intrapartum care | ||||||||

| Staff communication very good | ||||||||

| N (%)⁎⁎ | 2796 (68.2) | 115 (66.2) | 27 (68.4) | 87 (65.5) | 366 (59.9) | 70 (60.4) | 296 (59.8) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.91 (0.65, 1.27) | 1.01 (0.49, 2.08) | 0.89 (0.61, 1.29) | 0.70 (0.58, 0.83) | 0.71 (0.48, 1.05) | 0.69 (0.57, 0.84) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | 1 | 0.97 (0.68, 1.38) | 1.12 (0.52, 2.41) | 0.94 (0.63, 1.39) | 0.68 (0.57, 0.82) | 0.79 (0.54, 1.17) | 0.66 (0.54, 0.80) | |

| Confidence and trust always | ||||||||

| N (%)⁎⁎⁎ | 3103 (76.1) | 128 (74.2) | 32 (80.8) | 96 (72.2) | 393 (64.6) | 68 (58.4) | 326 (66.1) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.90 (0.63, 1.30) | 1.33 (0.57, 3.09) | 0.82 (0.55, 1.22) | 0.57 (0.46, 0.68) | 0.44 (0.30, 0.65) | 0.61 (0.50, 0.75) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | 1 | 0.98 (0.67, 1.44) | 1.64 (0.65, 4.15) | 0.86 (0.57, 1.30) | 0.56 (0.46, 0.68) | 0.48 (0.32, 0.70) | 0.58 (0.48, 0.72) | |

| Not left alone and worried at all | ||||||||

| N (%)* | 3103 (76.3) | 125 (73.5) | 28 (70.9) | 97 (74.3) | 422 (70.2) | 76 (66.9) | 346 (71.0) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.86 (0.60, 1.24) | 0.76 (0.37, 1.56) | 0.90 (0.59, 1.36) | 0.73 (0.61, 0.89) | 0.63 (0.42, 0.95) | 0.76 (0.62, 0.94) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | 1 | 0.94 (0.64, 1.38) | 0.95 (0.43, 2.09) | 0.93 (0.60, 1.44) | 0.70 (0.58, 0.85) | 0.64 (0.42, 0.97) | 0.72 (0.58, 0.89) | |

| MWs spoke so they could be understood | ||||||||

| N (%)⁎⁎⁎ | 3948 (96.5) | 156 (92.2) | 34 (85.8) | 121 (94.2) | 574 (93.7) | 104 (88.3) | 470 (95.0) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.43 (0.23, 0.94) | 0.22 (0.08, 0.57) | 0.58 (0.26, 1.30) | 0.53 (0.37, 0.77) | 0.27 (0.15, 0.50) | 0.68 (0.44, 1.04) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | 1 | 0.49 (0.25, 0.94) | 0.30 (0.10, 0.90) | 0.60 (0.27, 1.34) | 0.47 (0.32, 0.68) | 0.28 (0.15, 0.52) | 0.58 (0.37, 0.90) | |

| MWs kind and respectful | ||||||||

| N (%)⁎⁎⁎ | 3824 (93.8) | 147 (87.2) | 29 (73.4) | 118 (91.4) | 539 (88.5) | 100 (86.8) | 438 (88.9) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.45 (0.27, 0.73) | 0.18 (0.08, 0.39) | 0.70 (0.37, 1.34) | 0.51 (0.38, 0.68) | 0.43 (0.24, 0.78) | 0.53 (0.36, 0.72) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | 1 | 0.49 (0.29, 0.83) | 0.24 (0.10, 0.55) | 0.69 (0.36, 1.32) | 0.49 (0.37, 0.66) | 0.43 (0.24, 0.76) | 0.51 (0.37, 0.71) | |

| Overall, very satisfied with care during labour and birth | ||||||||

| N (%)⁎⁎⁎ | 2525 (61.6) | 82 (47.7) | 15 (38.8) | 66 (50.4) | 276 (45.3) | 49 (42.0) | 227 (46.0) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.57 (0.41, 0.78) | 0.39 (0.20, 0.78) | 0.63 (0.44, 0.91) | 0.52 (0.43, 0.61) | 0.45 (0.31, 0.66) | 0.53 (0.44, 0.64) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | 1 | 0.62 (0.44, 0.86) | 0.46 (0.22, 0.93) | 0.67 (0.46, 0.97) | 0.52 (0.44, 0.62) | 0.48 (0.33, 0.70) | 0.54 (0.44, 0.65) | |

| PN care in hospital | ||||||||

| MWs spoke so they could be understood | ||||||||

| N (%) | 3611 (94.2) | 151 (92.2) | 33 (86.5) | 118 (93.9) | 523 (93.0) | 103 (91.4) | 420 (93.4) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.73 (0.40, 1.32) | 0.40 (0.15, 1.04) | 0.95 (0.46, 1.99) | 0.81 (0.57, 1.16) | 0.65 (0.31, 1.37) | 0.86 (0.59, 1.27) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | 1 | 0.74 (0.40, 1.36) | 0.43 (0.15, 1.21) | 0.94 (0.45, 2.00) | 0.70 (0.49, 1.01) | 0.69 (0.33, 1.42) | 0.71 (0.48, 1.05) | |

| MWs kind and respectful | ||||||||

| N (%)⁎⁎⁎ | 3389 (88.9) | 136 (84.1) | 28 (73.6) | 108 (87.4) | 471 (84.2) | 93 (83.2) | 379 (84.4) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.66 (0.43, 1.03) | 0.35 (0.16, 0.76) | 0.86 (0.51, 1.47) | 0.66 (0.52, 0.86) | 0.62 (0.36, 1.06) | 0.68 (0.51, 0.89) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | 1 | 0.65 (0.41, 1.04) | 0.38 (0.17, 0.89) | 0.80 (0.46, 1.40) | 0.59 (0.45, 0.76) | 0.63 (0.37, 1.06) | 0.58 (0.43, 0.77) | |

| Overall, very satisfied with postnatal care | ||||||||

| N (%) | 1616 (39.3) | 66 (38.7) | 15 (36.6) | 52 (39.3) | 209 (34.3) | 41 (34.9) | 167 (34.1) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.97 (0.70, 1.34) | 0.89 (0.45, 1.78) | 1.00 (0.69, 1.44) | 0.80 (0.67, 0.96) | 0.83 (0.56, 1.22) | 0.80 (0.66, 0.97) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | 1 | 1.10 (0.78, 1.55) | 1.05 (0.50, 2.20) | 1.11 (0.76, 1.63) | 0.80 (0.66, 0.96) | 0.86 (0.58, 1.28) | 0.78 (0.64, 0.96) | |

| PN care after hospital discharge | ||||||||

| Would have preferred to have seen a MW at home more often | ||||||||

| N (%)⁎⁎⁎ | 868 (21.3) | 74 (43.7) | 18 (47.6) | 55 (42.6) | 188 (31.4) | 32 (27.2) | 156 (32.4) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1 | 2.87 (2.07, 3.97) | 3.35 (1.70, 6.60) | 2.74 (1.90, 3.95) | 1.69 (1.40, 2.03) | 1.38 (0.91, 2.09) | 1.77 (1.44, 2.17) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | 1 | 2.59 (1.84, 3.64) | 3.13 (1.50, 6.52) | 2.45 (1.68, 3.58) | 1.72 (1.42, 2.10) | 1.26 (0.83, 1.92) | 1.87 (1.51, 2.31) | |

Adjusted for maternal age, parity and Index of Multiple Deprivation

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001 in chi-square test

MW midwife; PN postnatal.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that women born outside the UK report a poorer experience of maternity care than UK-born women. Overall, women who came to the UK more recently, including more women from Accession countries, had a more negative perception of their care than women who had been in the UK for longer, more of whom came from outside Europe. Recent migrants were more commonly primiparous, younger, and all migrant groups were more highly educated than UK-born women. Clinically they were similar except that migrant women tended to have fewer pregnancy-related problems and recent migrants from Accession countries were more likely to have a normal birth. There was evidence of decreasing rates of breastfeeding with duration of residence in the UK which is consistent with previous research (Choudry and Wallace, 2012, Hawkins et al., 2008). However, recent migrants were more likely to have prolonged contact with midwives following hospital discharge which may reflect targeted support and a perception of greater need in this group, possibly associated with a lack of family support and more complex needs. Similar findings were reported in a US study which reported that midwives spent more time supporting women with complex psychosocial needs (Minde, Tidmarsh, & Hughes, 2001).

The focus of this study was on recency of migration and the experience of women from the Accession countries and this adds to the sparse literature in this area. The number of women included who were born in the Old (pre-enlargement) EEA was relatively small and they were therefore grouped with ‘rest of the world’ which was already large and heterogeneous. The logistic regressions showed that both region of origin and recency of migration are important in women's experience of care. Overall, earlier migrants had a slightly poorer experience of care than women who had arrived more recently but this masks the more profound differences by region of origin. Recent migrants from Accession countries particularly experienced problems understanding midwives and felt that they were not always treated well. This is consistent with the literature on migrant and ethnic minority women's experience of maternity generally (Balaam et al., 2013, Cross-Sudworth et al., 2011, Henderson et al., 2013, Jomeen and Redshaw, 2013). Similarly, a series of studies in Australia examined the maternity care experiences of women born outside the country (Small et al., 2014, Small et al., 2002, Yelland et al., 2015). They also found that migrant women had a poorer experience of care related to communication problems, a lack of familiarity with the system, and care that was unkind or lacking in respect. However, it contrasts with the findings of a large Canadian study which reported no significant differences in perceived compassion or respect among migrant women (Kingston et al., 2011), an inconsistency which may be due to differences in health care systems. None of these studies included data on recency of migration and the analyses presented here therefore provide a more nuanced picture.

Women's perceptions of care are coloured by their expectations (Hodnett, 2002). In most Central and Eastern European countries maternity care is physician-led with more antenatal screening and ultrasound scans than is common in the UK (Chalmers, 1997, Morrison, 2009). It is therefore probable that women may feel that they have received substandard care if, in an uncomplicated pregnancy, they see only midwives and have only one or two scans. In a study of Eastern European migrants to Ireland, the authors noted that in migrants’ country of origin, pregnancy is generally considered more of an ‘illness’ on the ‘health-illness’ continuum, and their expectations were therefore incongruent with the care received (Dempsey & Peeren, 2016). It is important that these potential discrepancies between expectation and experience are discussed by healthcare professionals with women in early pregnancy to maintain trust in care givers.

Other possible reasons for women's poor perceptions of their care are probably similar to those explored in other studies (D'Souza and Garcia, 2004, Jomeen and Redshaw, 2013, Lyons et al., 2008) and include difficulties with the language and medical terminology, and perceived discrimination and stereotyping by health professionals. It is important to hold in mind that recent migrants from Accession countries actually had fewer complications of pregnancy and childbirth and yet they perceived their care more negatively. Feelings of relative neglect and a lack of care compared to what they may have experienced in their home countries need to be understood by the health professionals providing their maternity care in the UK.

Limitations of this study include the 54% response rate with women born outside the UK being significantly less likely to respond. Although some foreign language information was enclosed with the questionnaire to encourage use of a Freephone number to complete the questionnaire with the aid of an interpreter, in practice this was seldom used. It is probable that women who needed help with English were less likely to complete the questionnaire and their experience of maternity care may have been even less satisfactory than that reported by the non-UK-born women who were able to respond. Year of migration was not stated for 306 women (27%) who were born outside the UK although only 39 were from Accession countries. It is unclear what effect this may have had on the results, although it would mainly affect ‘rest of the world’, already a heterogeneous group. A further limitation is that, despite aggregation, the numbers of women in some of groups was small and the study was therefore underpowered to detect small but important differences. Differences within the groups that were aggregated may also have masked real differences in their experience, particularly the ‘rest of the world’ group which was highly heterogeneous. The aggregation of Old EEA countries with ‘rest of the world’ may have diluted a poorer experience of care in this group, but as this was already a highly heterogeneous group, the effect is likely to be marginal.

Conclusions

Non-UK-born immigrants comprise a substantial proportion of women of child-bearing age in the UK, and are currently among those most likely to face deprivation and need increasingly complex care. Even as Brexit continues to impact who can and will move to the UK, non-UK-born women will still require maternity care. It is important that staff providing care during the antenatal, labour and postnatal periods are able to communicate effectively, through interpreters if necessary. The differences in clinical practice between women's home countries and the UK should be discussed so that women are able to make informed choices about their care.

The flexibility suggested by the prolonged postnatal contact with midwives among women who had arrived in the UK relatively recently is reassuring and in keeping with NICE recommendations for individualised postnatal care (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2006). It suggests an acknowledgement that these women may have additional needs in terms of information and support which may be met through longer engagement with staff.

The implications of Brexit are unclear but leaving the EU will have an impact on women moving to the UK depending on reasons for migration and country of origin. Under such changing circumstances it is important to continue to assess whether women's access to and experience of maternity care is adequate, equal and fair.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The original survey evaluating maternity services in England was passed by the Trent Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (06/MREC/16). Consent was considered implicit in completion and return of the questionnaire.

Funding

This paper reports on an independent study which was funded by the Policy Research Programme in the Department of Health. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Department. The Department of Health was not involved in any aspect of the study.

Acknowledgements

Our particular thanks go to the women who completed the survey and to staff at the Office for National Statistics who were responsible for drawing the sample and managing the mailings. The Office for National Statistics provided data for the sampling frame but bear no responsibility for its analysis and interpretation.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.midw.2018.09.008.

Contributor Information

Jane Henderson, Email: jane.henderson@npeu.ox.ac.uk.

Claire Carson, Email: claire.carson@npeu.ox.ac.uk.

Hiranthi Jayaweera, Email: hiranthi.jayaweera@compas.ox.ac.uk.

Fiona Alderdice, Email: fiona.alderdice@npeu.ox.ac.uk.

Maggie Redshaw, Email: maggie.redshaw@npeu.ox.ac.uk.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Balaam M.C., Akerjordet K., Lyberg A., Kaiser B., Schoening E., Fredriksen A.M., Ensel A., Gouni O., Severinsson E. A qualitative review of migrant women's perceptions of their needs and experiences related to pregnancy and childbirth. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013;69:1919–1930. doi: 10.1111/jan.12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers B. Childbirth in eastern Europe. Midwifery. 1997;13:2–8. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(97)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudry K., Wallace L. 'Breast is not always best': South Asian women's experiences of infant feeding in the UK within an acculturation framework. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8:72–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2010.00253.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross-Sudworth F., Williams A., Herron-Marx S. Maternity services in multi-cultural Britain: using Q methodology to explore the views of first- and second-generation women of Pakistani origin. Midwifery. 2011;27:458–468. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza L., Garcia J. Improving services for disadvantaged childbearing women. Child Care Health Dev. 2004;30:599–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey M., Peeren S. Keeping things under control: exploring migrant Eastern European womens’ experiences of pregnancy in Ireland. J. Reprod. Infant. Psychol. 2016;34:370–382. [Google Scholar]

- Eida, T. Not stated. Access to health and social care services by Eastern European migrants in Thanet District Healthwatch Kent, Kent.

- Gagnon A.J., Zimbeck M., Zeitlin J., Collaboration R., Alexander S., Blondel B., Buitendijk S., Desmeules M., Di Lallo D., Gagnon A., Gissler M., Glazier R., Heaman M., Korfker D., Macfarlane A., Ng E., Roth C., Small R., Stewart D., Stray-Pederson B., Urquia M., Vangen S., Zeitlin J., Zimbeck M. Migration to western industrialised countries and perinatal health: a systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009;69:934–946. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin R., Polek E., Goodwin K. Perceived changes in health and interactions with ‘‘the paracetamol force’’: a multimethod study. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2012;7:152–172. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman D.R., Katikireddi S.V., Morris C., Chalmers J.W., Sim J., Szamotulska K., Mierzejewska E., Hughes R.G. Ethnic variation in maternity care: a comparison of Polish and Scottish women delivering in Scotland 2004-2009. Public Health. 2014;128:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins S.S., Lamb K., Cole T.J., Law C., Millennium Cohort Study Child Health, G. Influence of moving to the UK on maternal health behaviours: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:1052–1055. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39532.688877.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes L. Unequal access to midwifery care: a continuing problem? J. Adv. Nurs. 1995;21:702–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.21040702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J., Gao H., Redshaw M. Experiencing maternity care: the care received and perceptions of women from different ethnic groups. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:196. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodnett E.D. Pain and women's satisfaction with the experience of childbirth: a systematic review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;186:S160–S172. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollowell J., Kurinczuk J., Brocklehurst p., Gray R. Social and ethnic inequalities in infant mortality: a perspective from the United Kingdom. Semin. Perinatol. 2011;35:240–244. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaweera H., Quigley M.A. Health status, health behaviour and healthcare use among migrants in the UK: evidence from mothers in the Millennium Cohort Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010;71:1002–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jomeen J., Redshaw M. Ethnic minority women's experience of maternity services in England. Ethn. Health. 2013;18:280–296. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.730608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston D., Heaman M., Chalmers B., Kaczorowski J., O'Brien B., Lee L., Dzakpasu S., O'Campo, P. Maternity Experiences Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System, P.H.A.o.C. Comparison of maternity experiences of Canadian-born and recent and non-recent immigrant women: findings from the Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2011;33:1105–1115. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M., Kurinczuk K., Spark P., Brocklehurst P. Ukoss: Inequalities in maternal health: national cohort study of ethnic variation in severe maternal morbidities. BMJ. 2009;338:b542. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons S.M., O'Keeffe F.M., Clarke A.T., Staines A. Cultural diversity in the Dublin maternity services: the experiences of maternity service providers when caring for ethnic minority women. Ethn. Health. 2008;13:261–276. doi: 10.1080/13557850801903020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden, H., Harris, J., Harrison, B., & Timpson, H. (2014). A targeted health needs assessment of the Eastern European population in Warrington, Liverpool.

- Merry L., Semenic S., Gyorkos T.W., Fraser W., Small R., Gagnon A.J. International migration as a determinant of emergency caesarean. Women Birth. 2016;29:e89–e98. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minde K., Tidmarsh L., Hughes S. Nurses' and physicians' assessment of mother-infant mental health at the first postnatal visits. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2001;40:803–810. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A. Bridging the gap: helping Polish mothers. Pract. Midwife. 2009;12:14–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . NICE; London: 2006. Postnatal Care up to 8 Weeks after Birth. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics, (2014). Births in England and Wales by Parents' Country of birth: 2013.

- Office for National Statistics, (2016). Birth summary tables - England and Wales.

- Osipovič D. ‘If I Get Ill, It's onto the Plane, and off to Poland.’ Use of Health Care Services by Polish Migrants in London. Central East. Eu. Migrat. Rev. 2013;2:98–114. [Google Scholar]

- Pendleton J. Why won't Polish women birth at home? Pract. Midwife. 2015;18:34–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raleigh V.S., Hussey D., Seccombe I., Hallt K. Ethnic and social inequalities in women's experience of maternity care in England: results of a national survey. J. R. Soc. Med. 2010;103:188–198. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2010.090460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redshaw M., Heikkila K. NPEU; Oxford: 2010. Delivered with Care: A National Survey of Women's Experiences of Maternity Care 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Redshaw M., Heikkila K. Ethnic differences in women's worries about labour and birth. Ethn. Health. 2011;16:213–223. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2011.561302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revill S. Healthwatch Norfolk; Norfolk: 2016. Maternity Services in Norfolk. A Snapshot Of User Experience Oct 2014 – April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sime D. 'I think that Polish doctors are better': Newly arrived migrant children and their parents experiences and views of health services in Scotland. Health Place. 2014;30:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small R., Roth C., Raval M., Shafiei T., Korfker D., Heaman M., McCourt C., Gagnon A. Immigrant and non-immigrant women's experiences of maternity care: a systematic and comparative review of studies in five countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small R., Yelland J., Lumley J., Brown S., Liamputtong P. Immigrant women's views about care during labor and birth: an Australian study of Vietnamese, Turkish, and Filipino women. Birth. 2002;29:266–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2002.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tromans N., Natamba E., Jefferie J. Have women born outside the U.K. driven the rise in U.K. births since 2001? Popul. Trends. 2009;136:28–42. doi: 10.1057/pt.2009.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller, L., Berrington, A., & Raymer, J. (2012). Understanding recent migrant fertility in the United Kingdom.

- Walsh J., Mahony R., Armstrong F., Ryan G., O'Herlihy C., Foley M. Ethnic variation between white European women in labour outcomes in a setting in which the management of labour is standardised-a healthy migrant effect? BJOG. 2011;118:713–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelland J., Riggs E., Small R., Brown S. Maternity services are not meeting the needs of immigrant women of non-English speaking background: results of two consecutive Australian population based studies. Midwifery. 2015;31:664–670. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.