Abstract

Background:

As the population with cardiovascular disease (CVD) ages, geriatric conditions are of increasing relevance. A possible geriatric prognostic indicator may be a fall risk score, which is mandated by the Joint Commission to be measured on all hospitalized patients. The prognostic value of a fall risk score on outcomes after dismissal is not well known. Thus, we aimed to determine whether a fall risk score is associated with death and hospital readmissions in patients with a recent incident CVD event.

Methods and Results:

In this retrospective cohort study, Olmsted County, MN, patients with incident heart failure (HF), myocardial infarction (MI) or atrial fibrillation (AF) between 8/1/2005 and 12/31/2011 who were hospitalized within 180 days after the event were studied. Fall risk was measured by the Hendrich II Fall Risk Model. Patients were followed for death or readmission within 30 days or 1 year. Among 2456 hospitalized patients with recent incident cardiovascular disease (549 HF, 784 MI, 1123 AF; mean (SD) age 71 (15); 55% male), the fall risk score was high in 22% of patients and moderate in 38%. The risk of death was increased if the fall risk score was increased, independently of age and comorbidities (moderate: HR: 1.51; 95% CI: 1.09–2.08; high HR: 3.49; 95% CI: 2.52–4.85). Similarly, the risk of 30-day readmissions was substantially increased with a greater fall risk score (moderate: HR: 1.29; 95% CI: 1.03–1.62; high HR: 1.63; 95% CI: 1.23–2.15). Results were similar for readmissions within 1 year.

Conclusions:

More than half of hospitalized patients with recent incident CVD have an elevated fall risk score, which is associated with an increased risk in readmissions and death. These results delineate an approach for risk stratification and management that may prevent readmissions and improve survival.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, fall risk, death, hospital readmissions

Introduction

Patients are presenting at increasingly older ages with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and geriatric conditions are a growing concern for these patients.1 Multimorbidity, frailty, cognitive decline, polypharmacy are all common among the elderly with CVD.2 However, most clinical trials exclude older adults or enroll patients with fewer comorbidities or physical impairments.2, 3 Therefore it is unclear whether current standards and guidelines are adequate to guide the care of this complex and vulnerable population.1, 2 As was recently highlighted,1 it is essential to integrate principles of geriatrics with those of cardiology as older adults now constitute the majority patient group. Doing so, while conceptually critical, is more challenging to operationalize with providers’ increasing case burden and time constraints. Extending the use of measures already used in current practice to stratify risk and plan interventions is thus an attractive and efficient approach.

One such measure is fall risk, which is of direct relevance to geriatric conditions and which the Joint Commission mandates to be assessed during hospitalizations in order to implement fall prevention measures in the hospital.4 Fall risk assessments are used in the hospital but are not typically integrated into post-dismissal care plans. The failure to leverage these estimates may be a missed opportunity. A fall risk score may be a ‘proxy’ for frailty. Frailty has been studied in CVD and is associated with worse outcomes;5–10 however the association specifically between a fall risk score and the outcomes of death and hospitalizations is less well studied.11 If a fall risk score predicted adverse outcomes post dismissal among patients with CVD, interventions to address underlying fall risk factors might improve the quantity and quality of life for these patients.

To address this question, we sought to determine whether fall risk is associated with outcomes (death and hospital readmissions) in a geographically defined population of patients hospitalized within 180 days after an incident (first-ever) CVD event. The fall risk was measured by the Hendrich II Fall Risk Model12, 13 and CVD events were defined as incident heart failure (HF), myocardial infarction (MI) or atrial fibrillation (AF). Conducting this study in a community population ensures complete capture of outcomes and provides results that are of high clinical relevance.

Methods

Study Setting

This study was conducted in Olmsted County, Minnesota (2010 population: 144,243). Olmsted County has similar age, sex and ethnic characteristics as the state of Minnesota and the Upper Midwest region of the US.14 Furthermore, age- and sex-specific mortality rates are similar for Olmsted County, the state of Minnesota and the entire US.14

Our study utilized the records-linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP), which allows nearly complete capture of health care utilization and outcomes in county residents.15 Nearly all health care related events occurring in Olmsted County can be identified because this area is relatively isolated from other urban centers and only a few providers (mainly Mayo Clinic, Olmsted Medical Center, and their affiliated hospitals) deliver most health care to local residents.

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure.

Identification of the Incident Cardiovascular Disease Patients

Patients from existing incidence cohorts of HF, MI and AF were included in the study.16–18 If a patient had more than one of these conditions, the first condition was considered the incident CVD event.

Heart Failure

Possible HF diagnoses among Olmsted County residents 20 years of age and older between August 1, 2005 and December 31, 2011 were identified using International Classification of Diseases-9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code 428 assigned during either an outpatient visit or a hospitalization.16, 19, 20 Due to budget and time constraints, a random sample of 50% of patients with a HF diagnosis prior to 2007 were manually reviewed, whereas 100% of patients with a HF diagnosis thereafter were manually reviewed. HF diagnoses were validated by experienced nurse abstractors using the Framingham Criteria.21 An event was classified as incident if after review of the entire medical record there was no history of prior HF.

Myocardial Infarction

All patients aged ≥18 admitted to Mayo Clinic Hospital — Rochester, MN between August 1, 2005 and December 31, 2011 who had a troponin T level of 0.03 ng/mL or higher and were assigned a ICD-9 CM code 410 (acute MI) or 411 (other acute and subacute forms of ischemic heart disease) were identified.

As we previously reported,17, 22 validation of MI relied on standard algorithms integrating cardiac pain, electrocardiographic (ECG) and biomarker data. According to current guidelines, each case was classified by troponin T.23 Systematic troponin T testing was initiated in 2000 and was fully implemented over the study period. The presence or absence of a change (rise or fall) between any two troponin T measurements was defined by a difference of at least 0.05 ng/mL, which is greater than the level of imprecision of the assay at all concentrations.23 Circumstances which might invalidate biomarker values were recorded.24 Troponin T was measured with a sandwich electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on the Elecsys 2010 (Roche Diagnostics Corporation; Indianapolis, Indiana) in the laboratories of the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology which is certified by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act of 1988 and the College of American Pathologists, with robust quality control in place.

Up to three electrocardiograms per episode were coded using the Minnesota Code Modular ECG Analysis System.25 According to the algorithm, MIs were classified as definite, probable, suspect or no infarction.22, 26 Those with a definite or probable MI were classified as an incident (first-ever) MI.

Atrial Fibrillation

Incident atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter (collectively referred to as AF hereafter) from August 1, 2005 to December 31, 2011 among adults aged ≥18 was identified using ICD-9 CM codes 427.31 and 427.32 from all providers in the REP and electrocardiograms (ECGs) from Mayo Clinic. As previously described, both inpatient and outpatient encounters were captured and all records were manually reviewed to validate the events.18 AF occurring within 30 days of a coronary artery bypass graft, surgery to repair or replace a heart valve, surgery to repair an atrial septal defect, or other open heart surgery were excluded. However, a future episode of AF unrelated to a surgery (or occurring more than 30 days after a surgery) was considered incident among these individuals with post-operative AF.

Hendrich II Fall Risk Model

The Hendrich II Fall Risk Model has been consistently administered at Mayo Clinic Hospital — Rochester beginning in August 2005. It has been shown to be useful in identifying patients at high risk for falls in acute care facilities,27 with sensitivity of 77–83%, specificity of 66–72%, and excellent inter-rater reliability.28 The assessment, performed by the patient’s nurse, includes screening for 8 fall risk factors: 1) confusion, disorientation or impulsivity; 2) symptomatic depression; 3) altered bowel or bladder elimination; 4) dizziness or vertigo; 5) male sex; 6) any administered antiepileptic; and 7) any administered benzodiazepine; and 8) functional mobility assessment (Get Up and Go Test: “Rising From a Chair”).12

The date of discharge for the first hospitalization within 180 days after the CVD event with a completed risk score was considered the index date. The fall risk score on or closet to the discharge date was selected for analysis.

Data Collection

Comorbidities were ascertained electronically by retrieving diagnostic codes from inpatient and outpatient encounters at all providers indexed in the REP. We selected comorbidities that were identified by the US Department of Health and Human Services (US-DHHS) for studying multimorbidity.29, 30 This list contains 20 comorbidities; however, we excluded autism (n=0), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV; n=2), and hepatitis (n=33) due to very low prevalence and cardiac arrhythmias, HF and coronary artery disease because the patients have AF, HF and MI. Two occurrences of a code (either the same code or two different codes within the code set for a given disease) separated by more than 30 days and occurring within 5 years prior to the incident CVD date were required for diagnosis.

In addition, body mass index (calculated as weight (in kg) divided by height (in meters) squared) and smoking status were manually abstracted from the medical records at the date of the CVD event.

Outcomes Ascertainment

Participants were followed for 1 year for all-cause death and hospital readmissions. Deaths were identified from inpatient and outpatient medical records, as well as death certificates received from Olmsted County and the state of Minnesota. Readmissions were identified from the REP which, as described previously, includes information on all hospital care delivered to Olmsted County residents within the county. In-hospital transfers or transfers between Olmsted Medical Center and Mayo Clinic were counted as one hospitalization. The primary cause of death and hospitalization were further categorized into cardiovascular, using the ICD-10 codes outlined by the American Heart Association,31 and non-cardiovascular.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics are presented as frequencies (percent), mean (SD) or median (25th, 75th percentile). Mantel-Haenszel chi-square tests were used to test for trends in characteristics across fall risk groups. The Hendrich II Fall Risk Model scores range from 0–16 and a score of 5 or greater is considered a high risk for falls.12 To examine a dose-response relationship, we further classified those not in the high risk group into low (score 0–1), and moderate (score 2–4) risk. Body mass index was dichotomized into overweight/obese (BMI≥25 kg/m2) or not overweight/obese (BMI <25 kg/m2) and smoking status was categorized into ever versus never.

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to determine associations between the fall risk score and each individual component of the score with death within 1 year of follow-up. Models were run univariately and while adjusting for baseline characteristics including age, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, stroke, chronic kidney disease, COPD, cancer, arthritis, osteoporosis, asthma, dementia, depression, schizophrenia, substance abuse, overweight/obese, and ever smoker. To test whether risk of death increased with increasing fall risk score, we tested for a trend using the score as one 3-level variable. Andersen-Gill models, a form of the Cox model that models multiple outcomes per person, were used to examine the associations between the fall risk score and each individual component with readmissions within 30 days and within 1 year, univariately and while controlling for confounders. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and was found to be valid. Analyses were repeated stratified by CVD condition and among patients aged 65 and older. Furthermore, the hospitalization analyses were repeated to analyze time to first hospitalization within 30 days and time to first hospitalization within 1 year using Cox proportional hazards regression.

All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center Institutional Review Boards.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

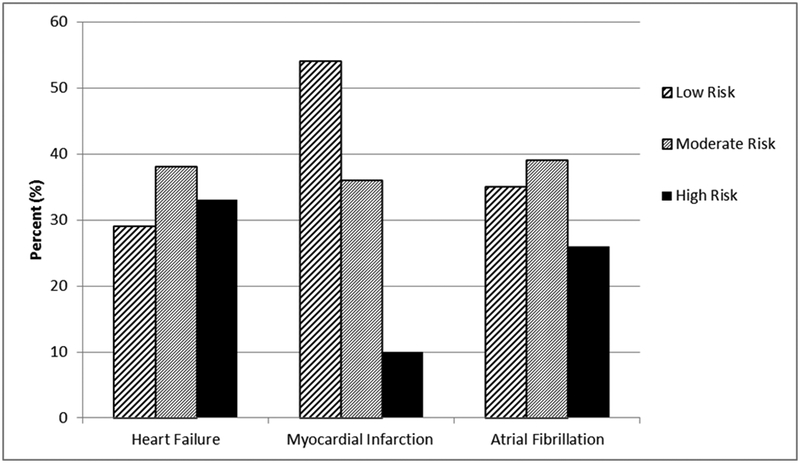

Between August 2005 and December 2011, 3477 patients had an incident CVD event. Of these, 2777 were hospitalized at Mayo Clinic Hospital — Rochester on or within 180 days after their event; however 264 died before hospital discharge, resulting in 2513 patients eligible for the study. Of these, 2456 patients (549 HF, 784 MI, 1123 AF; mean (SD) age 71 (15); 55% male) had a Hendrich II Fall Risk assessment within 180 days of their CV event (1803 at the time of the event and 653 at a subsequent hospitalization within 180 days of their event). Within the cohort, 2277 (93%) of the patients were hospitalized for CV-related reasons. Approximately 22% (n=549) of patients had a high fall risk score and 38% (n=930) had a moderate score. This equates to 60% of patients presenting with an increased fall risk within 180 days after an incident CVD diagnosis. The proportion of patients in each fall risk score group by CVD event type is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The proportion of patients in each fall risk group by type of cardiovascular event.

A higher fall risk score was associated with the majority of comorbid conditions with the exception of asthma, hyperlipidemia and smoking and being overweight or obese which was associated with a lower fall risk (Table 1). A higher fall risk score was associated with greater frequency of discharge to a skilled nursing facility (4%, 15% and 50% for a low, moderate and high score, respectively).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics, Overall and by Hendrich II Fall Risk Model Score

| Overall (N=2456) | Low Risk (n=977) | Moderate Risk (n=930) | High Risk (n=549) | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 71.0 (15.4) | 65.4 (14.9) | 71.2 (14.6) | 80.8 (12.2) | <0.001 |

| Male | 1345 (55) | 471 (48) | 612 (66) | 262 (48) | 0.181 |

| Overweight/Obese* | 1757 (72) | 725 (74) | 696 (75) | 336 (61) | <0.001 |

| Ever smoker | 1420 (58) | 562 (58) | 572 (62) | 286 (52) | 0.129 |

| Stroke | 231 (9) | 52 (5) | 90 (10) | 89 (16) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1635 (67) | 568 (58) | 636 (68) | 431 (79) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1375 (56) | 558 (57) | 531 (57) | 286 (52) | 0.087 |

| Diabetes | 808 (33) | 295 (30) | 312 (34) | 201 (37) | 0.009 |

| Arthritis | 775 (32) | 264 (27) | 298 (32) | 213 (39) | <0.001 |

| Osteoporosis | 306 (12) | 90 (9) | 97 (10) | 119 (22) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 173 (7) | 80 (8) | 59 (6) | 34 (6) | 0.104 |

| COPD | 371 (15) | 110 (11) | 163 (18) | 98 (18) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 424 (17) | 98 (10) | 181 (19) | 145 (26) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 675 (27) | 208 (21) | 271 (29) | 196 (36) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 463 (19) | 162 (17) | 147 (16) | 154 (28) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 184 (7) | 7 (1) | 31 (3) | 146 (27) | <0.001 |

| Schizophrenia | 63 (3) | 3 (0.3) | 19 (2) | 41 (7) | <0.001 |

| Substance Abuse | 110 (4) | 32 (3) | 46 (5) | 32 (6) | 0.015 |

Results are presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

1 patient was missing body mass index.

Fall Risk Score and Outcomes

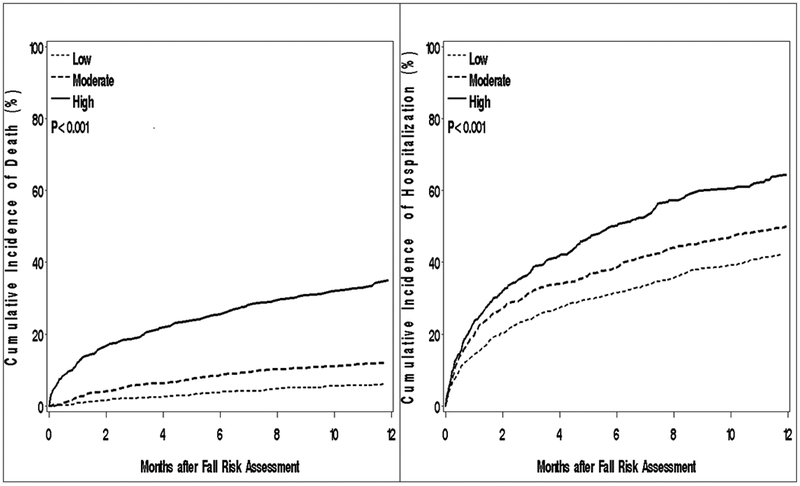

Within 1 year, 362 deaths occurred (113, 53, and 196 deaths among the HF, MI and AF patients, respectively) equating to a one-year mortality rate of 15% (95% CI: 13%−16%). Within the first 30 days, 18% of patients were hospitalized at least once (20%, 15% and 19% among the HF, MI and AF patients, respectively). Within 1 year of follow-up, 1177 patients experienced 2325 readmissions (670, 595 and 1060 readmissions among the HF, MI and AF patients, respectively). The majority of outcome events were non-cardiovascular related (59% of deaths within 1 year, 57% of readmissions within 30 days and 65% of readmissions within 1 year). A strong graded positive association was noted between greater fall risk and both death and readmissions (Figure 2). Associations were similar when stratified by type of CVD event (Supplementary Figure 1) and among patients aged 65 and older (n=1685; Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of death (left) and hospitalization (right) within 1 year by Hendrich II Fall Risk Model score.

After adjustment for age, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, stroke, chronic kidney disease, COPD, cancer, arthritis, osteoporosis, asthma, dementia, depression, schizophrenia, substance abuse, ever smoking and being overweight or obese, a moderate fall risk score was associated with a 51% increased risk of death within 1 year (HR: 1.51; 95% CI: 1.09–2.08) whereas a high score was associated with a 3.5 fold increased risk of death (HR: 3.49; 95% CI: 2.52–4.85) compared to a low score (Table 2). For readmissions, a moderate score was associated with a 29% increased risk of hospitalization within 30 days (HR: 1.29; 95% CI: 1.03–1.62), while those with a high score had a 63% increased risk of hospitalization (HR: 1.63; 95% CI: 1.23–2.15). Within 1 year, patients with a moderate fall risk score had an 18% increased risk of readmissions (HR: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.02–1.36) and those with a high score had a 47% increased risk of readmissions (HR: 1.47; 95% CI: 1.22–1.76) compared to a low score. The association between the fall risk score and death and readmissions was stronger for non-CVD related events than for CVD-related events (Table 2). Similar results were found when analyses were stratified by type of CVD event (Supplementary Table 1) and restricted to patients aged 65 or older (Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, similar results were found when the hospitalization analysis was repeated analyzing only the time to first hospitalization within 30 days and within 1 year (data not shown).

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios and 95% CI for All-cause, Cardiovascular and Non-cardiovascular Death and Readmissions by Hendrich II Fall Risk Model Score

| Fall Risk Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | Moderate Risk | High Risk | P for trend | |

| Death within 1 year | ||||

| All-cause | ||||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.67 (1.21–2.30) | 3.99 (2.92–5.46) | <0.001 |

| Fully-Adjusted* | 1.00 (ref) | 1.51 (1.09–2.08) | 3.49 (2.52–4.85) | <0.001 |

| CV-related | ||||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.34 (0.82–2.19) | 2.52 (1.56–4.05) | <0.001 |

| Fully-adjusted* | 1.00 (ref) | 1.31 (0.79–2.15) | 2.62 (1.60–4.31) | <0.001 |

| Non-CV related | ||||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.98 (1.30–3.01) | 5.49 (3.62–8.33) | <0.001 |

| Fully-adjusted* | 1.00 (ref) | 1.73 (1.13–2.65) | 4.31 (2.78–6.70) | <0.001 |

| 30-day readmissions | ||||

| All-cause | ||||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.35 (1.08–1.69) | 1.64 (1.25–2.16) | <0.001 |

| Fully-Adjusted* | 1.00 (ref) | 1.29 (1.03–1.62) | 1.63 (1.23–2.15) | 0.001 |

| CV-related | ||||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.03 (0.75–1.41) | 0.71 (0.47–1.08) | 0.159 |

| Fully-adjusted* | 1.00 (ref) | 1.03 (0.75–1.42) | 0.78 (0.50–1.20) | 0.362 |

| Non-CV related | ||||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.72 (1.27–2.34) | 2.94 (2.06–4.20) | <0.001 |

| Fully-adjusted* | 1.00 (ref) | 1.59 (1.17–2.16) | 2.68 (1.87–3.85) | <0.001 |

| Readmissions within 1 year | ||||

| All-cause | ||||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.31 (1.13–1.51) | 1.76 (1.48–2.09) | <0.001 |

| Fully-Adjusted* | 1.00 (ref) | 1.18 (1.02–1.36) | 1.47 (1.22–1.76) | <0.001 |

| CV-related | ||||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 0.97(0.79–1.19) | 0.88 (0.68–1.15) | 0.391 |

| Fully-adjusted* | 1.00 (ref) | 0.90 (0.74–1.11) | 0.82 (0.61–1.09) | 0.150 |

| Non-CV related | ||||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.58 (1.32–1.88) | 2.53 (2.06–3.10) | <0.001 |

| Fully-adjusted* | 1.00 (ref) | 1.42 (1.19–1.68) | 2.03 (1.65–2.50) | <0.001 |

adjusted for age, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, stroke, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, arthritis, osteoporosis, asthma, dementia, depression, schizophrenia, substance abuse, overweight/obese and ever smoking.

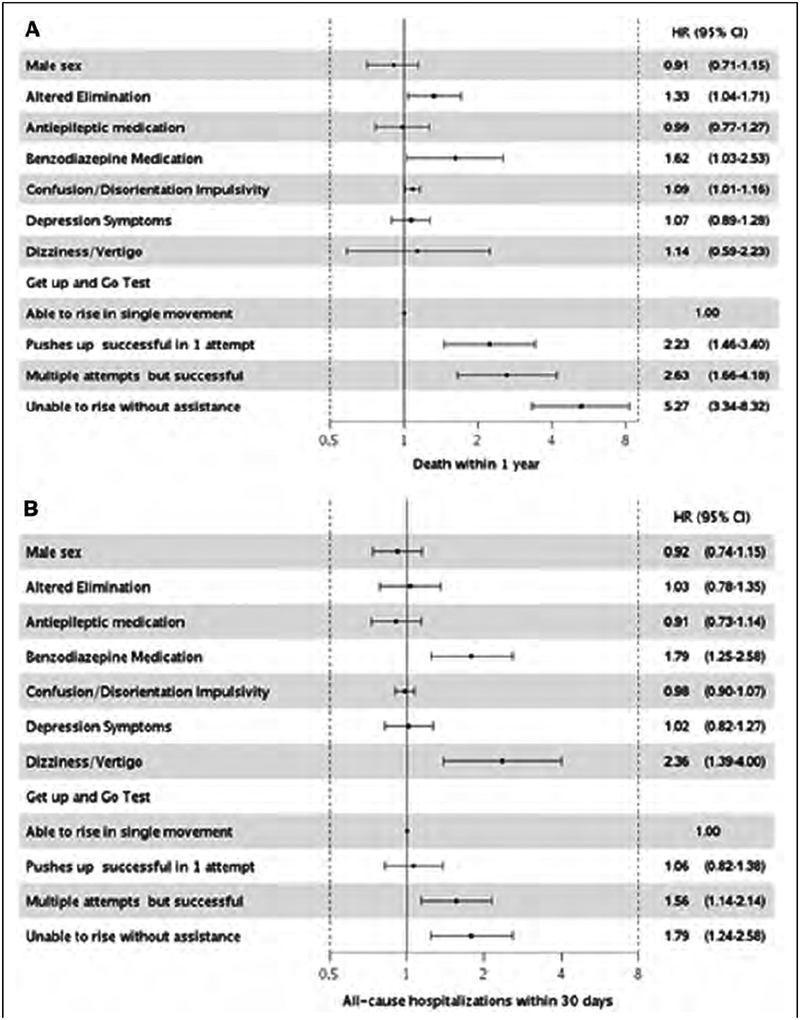

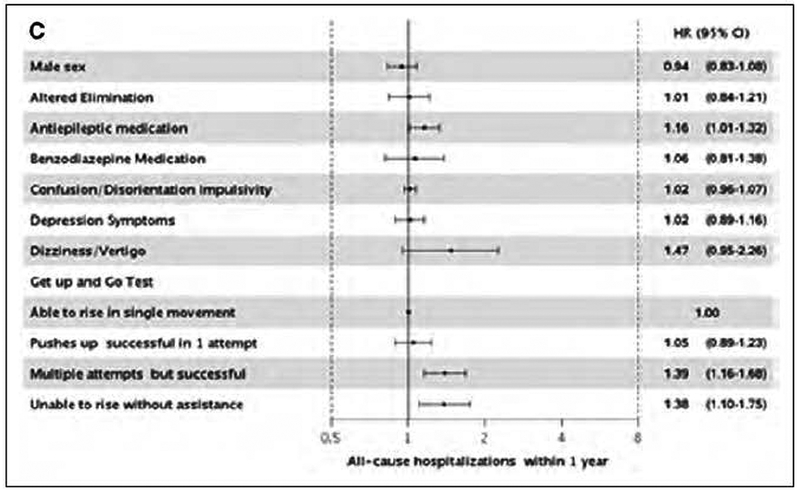

The individual component of the Hendrich II Fall Risk Model most strongly associated with death and readmissions within 1 year was functional mobility as measured by the Get Up and Go Test (Figure 3). Altered elimination, benzodiazepine medications and confusion/disorientation/impulsivity were also associated with an increased risk of death within 1 year, while antiepileptic medications were also associated with readmission within 1 year. Dizziness/vertigo, the Get Up and Go Test and benzodiazepine medications were associated readmissions within 30 days.

Figure 3.

Adjusted* hazard ratios and 95% CI for all-cause death (Panel A) and readmissions within 30 days (Panel B) and 1 year (Panel C) by individual components of the Hendrich II Fall Risk Model.

* adjusted for age, comorbidities, overweight/obesity, ever smoking and all individual components of fall risk assessment.

Discussion

Our study of a geographically-defined community documents that the majority of hospitalized patients recently diagnosed with one of the 3 most frequent cardiovascular events (HF, MI or AF) have a moderate or high fall risk score , as measured by the Hendrich II Fall Risk Model score. The high prevalence of an increased fall risk score, a geriatric prognostic indicator, underscores the burden of geriatric conditions among CVD patients in the community. Fall risk is of particular interest as its assessment is mandated during hospitalizations by the Joint Commission.4 This systematic assessment of all patients admitted to the hospital provides us with the opportunity to document, in a community cohort, that a large majority (61%) of hospitalized CVD patients have an elevated risk for falls. Awareness of this issue among providers is essential to define a path towards prevention.

A greater fall risk score has markedly adverse prognostic implications with a large increase in the risk of death and readmissions, particularly prominent for events attributed to non-CVD causes. Limited functional mobility was one of the main drivers of this association. As functional mobility is a modifiable risk factor, the current findings point to important clinical implications.

Patients with CVD Are Aging: Implications

The average life expectancy in the US has increased 30 years since 1900.1 Adults aged 65 or older will comprise 19% of the population by 2030, including 19 million adults over the age of 85 years. The growth of the 85+ age group is particularly striking; it is projected to double from its current size in 2036 and triple by 2049.1 The prevalence of most cardiovascular diseases increases with age.2 An estimated 85.6 million American adults (>1 in 3) have 1 or more types of CVD. Of these, 43.7 million are estimated to be ≥60 years of age.31 People 65 years of age or older account for more than half of all CV-related hospitalizations and procedures in the US and approximately 80% of CV-related deaths.31 Consequently, aspects of aging including multimorbidity, polypharmacy, frailty and mobility are all important concerns for CVD patients that should be integrated into the clinical evaluation of most patients presenting with CVD. Fall risk may be a proxy for frailty. Frailty has been well studied in CVD and is associated with poor outcomes such as death and hospitalization.6–10 However, importantly, frail or physically impaired patients are excluded from clinical trials.32, 33 Thus, to the extent that current guidelines anchor their recommendations on the strongest level of evidence as afforded by clinical trials, standards may not be optimal to provide recommendations for this large proportion of patients seen in clinical practice.

Fall Risk and Outcomes

The initial purpose of the Hendrich II Fall Risk Model is to measure fall risk during a hospitalization for the purpose of in-hospital prevention. The present study focuses on other prognostic benefits. Perhaps an even greater opportunity for the Hendrich II model is its ability to identify actionable “geriatric comorbidities” that impact patient outcomes. Identification of these risk factors could lead to systematic interventions to address patient-centered risk factors. Literature on the prognostic implication of fall risk in CVD patients is scarce and a study which did not detect an association between fall risk, measured by the Morse Fall Scale, and death in HF was limited by small sample size.11 Our results expand upon this aforementioned study by investigating the association between a fall risk score and death and readmission in a large community cohort of the 3 most common CVD events (HF, MI and AF), all manually validated using standardized criteria. Patients with a moderate or high score had an increased risk of death within 1 year and an increased risk of readmissions within 30 days and 1 year, compared to a low score. The association with the fall risk score was stronger for non-CVD related events than for CVD-related events.

The assessment of functional mobility by the Get Up and Go Test was one of the strongest predictors of death and readmissions. This is important as functional mobility is a risk factor that, contrary to others in the Hendrich II score, is potentially modifiable. Early reports suggested a role for approaches to increase patient mobility in the hospital34–37 which have been connected to favorable outcomes, including physical function, length of stay, costs, skilled facility placement, and two-year mortality.34–39 Further, the Get Up and Go Test is a relatively simple performance-based measure of mobility. Concurrent use of functional assessments encompassing additional domains could yield more precise risk estimates. However, further research is needed to understand the mechanism by which physical function affects death and hospital readmissions.

Clinical Implications

These results indicate that leveraging an existing measure of fall risk that is already part of the care process identifies CVD patients at risk for readmissions and death. Taking this score into account to stratify risk and plan management accordingly would not augment the cost of care or reduce its efficiency. As there is a robust rationale for interventions, mostly exercise-based, to improve physical functioning and frailty which appear to be effective among the elderly40, 41 and patients with CVD, 42, 43 this may provide an avenue to manage these patients.

Several models of care address the unique vulnerabilities of hospitalized older adults, including consultative practices (e.g. comprehensive geriatric evaluation) and/or unit-based models (e.g. Acute Care for Elders units). Interdisciplinary models of acute geriatric unit care have been associated with improvements in multiple outcomes, including falls, delirium, functional decline, length of stay, and frequency of nursing home discharges,44 as well as reduced hospital costs and readmissions.45 Similar interventions targeted to CVD patients identified as high risk for falls could potentially improve survival and decrease readmissions, although this hypothesis should be formally tested in future studies. Indeed, these interventions may need to go beyond common fall risk interventions. Important next steps will be to design and test interdisciplinary treatment pathways that can be cost-effectively scaled to the substantial population at risk.

Our results highlight the importance of non-CVD related conditions in CVD patients. The Hendrich II model was designed to identify fall risk; the results of our study suggest that it may have even more utility as a marker of vulnerability, in that it may identify patients who have relevant underlying pathophysiology (e.g. functional dependence, acute or chronic cognitive disorders, issues with elimination or dizziness) that may not otherwise be considered to be a significant medical “comorbidity”. We have previously shown that non-CVD conditions, frailty and poor physical functioning are frequent in HF patients and are important for prognosis.8, 46–50 In addition, we and others have observed that the majority of hospitalizations and death are due to non-cardiovascular causes in HF, MI and AF patients.16, 19, 51–54 This underscores the importance of integrating principles of geriatrics in the practice of cardiology and the need to develop guidelines, recommendations and performance measures to specifically address issues pertinent to older adults living with CVD. This, in turn, could ultimately lead to improved patient-centered care for these complex patients.

Limitations and Strengths

Some limitations of our study deserve mention. Our results may not be generalizable to all populations; however, as mentioned previously, the Olmsted County population is representative of the state of Minnesota and the Midwest region of the US.14 While we cannot exclude that we may have missed some events that occurred outside of Olmsted County, in our experience this is quite uncommon. We acknowledge that there are other fall risk assessment tools, however the Hendrich II Fall Risk Model is routinely measured on all inpatients at our institution, and we wanted to explore the utility of an existing geriatric measure used in clinical practice.

Our study also has several strengths, including the rigorous validation of HF, MI and AF in the community. The linkage of medical records allowed for complete ascertainment of comorbidities from multiple sources of care. Furthermore, we captured multiple readmissions occurring within 1 year of follow-up and did not restrict to the first readmission or to readmissions only for cardiovascular causes, which is particularly important given that we and others16, 19, 51, 53, 54 have reported on the burden of non-cardiovascular causes of readmissions among patients with CVD.

Conclusion

More than half of hospitalized patients with a recent incident CVD diagnosis have a moderate or high risk for falls. A greater fall risk score, which may be considered a geriatric prognostic indicator, was associated with a large increase in the risk of readmissions and death. Furthermore, the fall risk score was more strongly associated with non-CVD causes of death and readmissions compared to CVD causes, and the associations chiefly reflected the adverse impact of reduced mobility. Our results underscore the prognostic value of assessing the risk of fall among patients with CVD.

Supplementary Material

What is known?

Patients are presenting at increasingly older ages with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and geriatric conditions are a growing concern for these patients.

Multimorbidity, frailty, cognitive decline, polypharmacy are all common among the elderly with CVD.

What the study adds?

Approximately 22% of hospitalized patients with a recent CVD diagnosis had a high Hendrich II Fall Risk Model score and 38% had a moderate score.

A greater fall risk score was associated with an increase in the risk of death and readmissions, particularly prominent for events attributed to non-CVD causes.

Limited functional mobility was one of the main drivers of this association.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dawn D. Schubert, RN, and Deborah S. Strain for her study support.

Sources of Funding:

This work was made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (grant number R01 AG034676). This work was also supported by grant R01 HL120859 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. The funding sources played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Bell SP, Orr NM, Dodson JA, Rich MW, Wenger NK, Blum K, Harold JG, Tinetti ME, Maurer MS, Forman DE. What to expect from the evolving field of geriatric cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1286–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rich MW, Chyun DA, Skolnick AH, Alexander KP, Forman DE, Kitzman DW, Maurer MS, McClurken JB, Resnick BM, Shen WK, Tirschwell DL. Knowledge gaps in cardiovascular care of the older adult population: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Geriatrics Society. Circulation. 2016;133:2103–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnett DK, Goodman RA, Halperin JL, Anderson JL, Parekh AK, Zoghbi WA. AHA/ACC/HHS strategies to enhance application of clinical practice guidelines in patients with cardiovascular disease and comorbid conditions: from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and US Department of Health and Human Services. Circulation. 2014;130:1662–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sentinel Alert Event: A complimentary publication of The Joint Commission. Issue 55, September 28, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afilalo J, Alexander KP, Mack MJ, Maurer MS, Green P, Allen LA, Popma JJ, Ferrucci L, Forman DE. Frailty assessment in the cardiovascular care of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:747–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cacciatore F, Abete P, Mazzella F, Viati L, Della Morte D, D’Ambrosio D, Gargiulo G, Testa G, Santis D, Galizia G, Ferrara N, Rengo F. Frailty predicts long-term mortality in elderly subjects with chronic heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest. 2005;35:723–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lupon J, Gonzalez B, Santaeugenia S, Altimir S, Urrutia A, Mas D, Diez C, Pascual T, Cano L, Valle V. Prognostic implication of frailty and depressive symptoms in an outpatient population with heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2008;61:835–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNallan SM, Singh M, Chamberlain AM, Kane RL, Dunlay SM, Redfield MM, Weston SA, Roger VL. Frailty and Healthcare Utilization Among Patients With Heart Failure in the Community. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1:135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekerstad N, Swahn E, Janzon M, Alfredsson J, Lofmark R, Lindenberger M, Carlsson P. Frailty Is Independently Associated With Short-Term Outcomes for Elderly Patients With Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2011;124:2397–2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh M, Rihal CS, Lennon RJ, Spertus JA, Nair KS, Roger VL. Influence of frailty and health status on outcomes in patients with coronary disease undergoing percutaneous revascularization. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:496–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carazo M, Sadarangani T, Natarajan S, Katz SD, Blaum C, Dickson VV. Prognostic Utility of the Braden Scale and the Morse Fall Scale in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure. West J Nurs Res. 2017;39:507–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendrich A How to try this: predicting patient falls. Using the Hendrich II Fall Risk Model in clinical practice. Am J Nurs. 2007;107:50–58; quiz 58–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matarese M, Ivziku D, Bartolozzi F, Piredda M, De Marinis MG. Systematic review of fall risk screening tools for older patients in acute hospitals. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71:1198–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ 3rd, Rocca WA. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1202–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerber Y, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Chamberlain AM, Manemann SM, Jiang R, Killian JM, Roger VL. A contemporary appraisal of the heart failure epidemic in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2000 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:996–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roger VL, Weston SA, Gerber Y, Killian JM, Dunlay SM, Jaffe AS, Bell MR, Kors J, Yawn BP, Jacobsen SJ. Trends in incidence, severity, and outcome of hospitalized myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2010;121:863–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chamberlain AM, Gersh BJ, Alonso A, Chen LY, Berardi C, Manemann SM, Killian JM, Weston SA, Roger VL. Decade-long trends in atrial fibrillation incidence and survival: a community study. Am J Med. 2015;128:260–267e261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunlay SM, Redfield MM, Weston SA, Therneau TM, Hall Long K, Shah ND, Roger VL. Hospitalizations after heart failure diagnosis a community perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1695–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Hellermann-Homan JP, Killian J, Yawn BP, Jacobsen SJ. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA. 2004;292:344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho KK, Pinsky JL, Kannel WB, Levy D. The epidemiology of heart failure: the Framingham Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:6A–13A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roger VL, Jacobsen SJ, Weston S, Goraya TY, Killian J, Reeder GS, Kottke TE, Yawn BP, Frye RL. Trends in the Incidence and Survival of Patients with Hospitalized Myocardial Infarction, Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1979 to 1994. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP, al. e. Myocardial infarction redefined--a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:959–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaffe AS. Elevations of troponin - False positive, the real truth. Cardiovascular Toxicology. 2001;1:87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kors JA, Crow RS, Hannan PJ, Rautaharju PM, Folsom AR. Comparison of computer-assigned Minnesota Codes with the visual standard method for new coronary heart disease events. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:790–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White AD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Sharret AR, Yang K, Conwill D, Higgins M, Williams OD, Tyroler HA. Community surveillance of coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: methods and initial two years’ experience. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim EA, Mordiffi SZ, Bee WH, Devi K, Evans D. Evaluation of three fall-risk assessment tools in an acute care setting. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hendrich A, Nyhuis A, Kippenbrock T, Soja ME. Hospital falls: development of a predictive model for clinical practice. Appl Nurs Res. 1995;8:129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodman RA, Posner SF, Huang ES, Parekh AK, Koh HK. Defining and measuring chronic conditions: imperatives for research, policy, program, and practice. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Department of Health and Human Services. Multiple chronic conditions - a strategic framework: optimum health and quality of life for individuals with multiple chronic conditions. December, 2010. Accessed June 26, 2018https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ash/initiatives/mcc/mcc_framework.pdf

- 31.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB . Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyd CM, Vollenweider D, Puhan MA. Informing evidence-based decision-making for patients with comorbidity: availability of necessary information in clinical trials for chronic diseases. PloS one. 2012;7:e41601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss J, Freeman M, Low A, Fu R, Kerfoot A, Paynter R, Motu’apuaka M, Kondo K, Kansagara D. Benefits and Harms of Intensive Blood Pressure Treatment in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:419–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoyer EH, Friedman M, Lavezza A, Wagner-Kosmakos K, Lewis-Cherry R, Skolnik JL, Byers SP, Atanelov L, Colantuoni E, Brotman DJ, Needham DM. Promoting mobility and reducing length of stay in hospitalized general medicine patients: A quality-improvement project. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wood W, Tschannen D, Trotsky A, Grunawalt J, Adams D, Chang R, Kendziora S, Diccion-MacDonald S. A mobility program for an inpatient acute care medical unit. Am J Nurs. 2014;114:34–40; quiz 41–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mundy LM, Leet TL, Darst K, Schnitzler MA, Dunagan WC. Early mobilization of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2003;124:883–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hastings SN, Sloane R, Morey MC, Pavon JM, Hoenig H. Assisted early mobility for hospitalized older veterans: preliminary data from the STRIDE program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2180–2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur-Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G. Hospital-associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostir GV, Berges IM, Kuo YF, Goodwin JS, Fisher SR, Guralnik JM. Mobility activity and its value as a prognostic indicator of survival in hospitalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:551–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Theou O, Stathokostas L, Roland KP, Jakobi JM, Patterson C, Vandervoort AA, Jones GR. The effectiveness of exercise interventions for the management of frailty: a systematic review. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:569194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chou CH, Hwang CL, Wu YT. Effect of exercise on physical function, daily living activities, and quality of life in the frail older adults: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, Zwisler AD, Rees K, Martin N, Taylor RS. Exercise-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation for Coronary Heart Disease: Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, Keteyian SJ, Cooper LS, Ellis SJ, Leifer ES, Kraus WE, Kitzman DW, Blumenthal JA, Rendall DS, Miller NH, Fleg JL, Schulman KA, McKelvie RS, Zannad F, Pina IL. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1439–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fox MT, Persaud M, Maimets I, O’Brien K, Brooks D, Tregunno D, Schraa E. Effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care using acute care for elders components: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:2237–2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flood KL, Maclennan PA, McGrew D, Green D, Dodd C, Brown CJ. Effects of an acute care for elders unit on costs and 30-day readmissions. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:981–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McNallan SM, Chamberlain AM, Gerber Y, Singh M, Kane RL, Weston SA, Dunlay SM, Jiang R, Roger VL. Measuring frailty in heart failure: A community perspective. Am Heart J. 2013;166:768–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chamberlain AM, McNallan SM, Dunlay SM, Spertus JA, Redfield MM, Moser DK, Kane RL, Weston SA, Roger VL. Physical health status measures predict all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:669–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dunlay SM, Manemann SM, Chamberlain AM, Cheville AL, Jiang R, Weston SA, Roger VL. Activities of daily living and outcomes in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:261–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manemann SM, Chamberlain AM, Boyd CM, Gerber Y, Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Jiang R, Roger VL. Multimorbidity in Heart Failure: Effect on Outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:1469–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chamberlain AM, St Sauver JL, Gerber Y, Manemann SM, Boyd CM, Dunlay SM, Rocca WA, Finney Rutten LJ, Jiang R, Weston SA, Roger VL. Multimorbidity in heart failure: a community perspective. Am J Med. 2015;128:38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Killian JM, Bell MR, Jaffe AS, Roger VL. Thirty-day rehospitalizations after acute myocardial infarction: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henkel DM, Redfield MM, Weston SA, Gerber Y, Roger VL. Death in heart failure: a community perspective. Circulation Heart failure. 2008;1:91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Naccarelli GV, Johnston SS, Dalal M, Lin J, Patel PP. Rates and implications for hospitalization of patients >/=65 years of age with atrial fibrillation/flutter. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bengtson LG, Lutsey PL, Loehr LR, Kucharska-Newton A, Chen LY, Chamberlain AM, Wruck LM, Duval S, Stearns SC, Alonso A. Impact of atrial fibrillation on healthcare utilization in the community: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.