Abstract

A synthetic peptide containing two Nε-methyl lysines (Ac-K(Nε-Me)GYTGYTGK(Nε-Me)D-OH) was alkylated with bipyridine (bipy) ligands substituted at the fifth (MP-5) and sixth (MP-6) positions, thereby creating Ac-K(Nε-Me, Nε-Bipy)GYTGYTGK(Nε-Me, Nε-Bipy)D-OH. Peptides with 6-position bipyridine did not bind to Fe2+ and Zn2+. Peptides with 5-position bipyridine bound these metals, and in the presence of one equivalent of a free bipy derivative folded into a macrocycle. Further, the free bipy derivative could also contain a cyclized peptide derived from hydrazone formation, resulting in complex but controlled quaternary peptide structure.

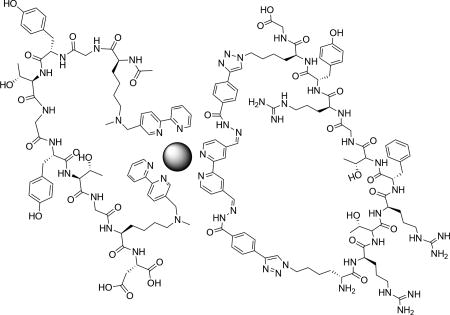

Graphical abstract

Complex quaternary structure formation of bipy peptide ligands.

Introduction

Metal chelation is commonly found in nature for the control of protein quaternary structure.1–2 Nearly one-third of proteins have metal coordination sites to execute regulatory or enzymatic processes.3 Synthetic polypeptides that mimic this metal-mediated folding garner interest, because they can be used as therapeutics or novel materials capable of functioning in biotic and abiotic conditions.4, 5 An advantage of synthetic structures is the ability to incorporate unnatural functionalities that act as recognition units, promote folding, or sequester small organic structures. Therefore, chemists introduce metal ligand coordination into peptides using both naturally occurring residues and non-canonical metal binders amino acids.6

The use of one pyridine ring, in conjunction with natural metal ligands, has led to interesting folding properties of synthetic peptides.7 Similarly, bipyridine (bipy) combines two binding sites, and is among the most widely used metal ligands. Synthesis of small molecules, polymers, and peptides containing this functional group to exploit their folding properties have been reported.8–12 These moieties facilitate helical formation of organic compounds, act as materials in photovoltaic/electronic devices, serve as molecular sensors, and are applied in luminescent devices. Bipyridines are also used extensively for binding Cu2+, Zn2+, and Fe2+, cations of biological interest.8 Ligand to metal stoichiometries of 2:1 and 3:1 are achieved with different metals, and thus offer the ability to control peptide structure and aggregation states. Due to their utility, we sought a facile synthetic way for incorporating bipy ligands for controlled folding of synthetic polypeptides.

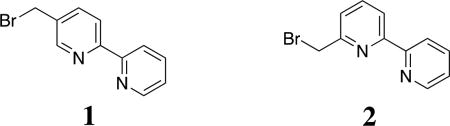

Alkylation of secondary amine residues was previously reported by our group as a method to efficiently incorporate boronic acids, and the use of a similar methodology to modify peptides with 2,2’-bipyridines is presented here.13 Brominated compounds 1 and 2 were synthesized for this purpose.

While natural amino acids building blocks are commercially available, most unnatural ones are not. If available, they are priced high, making them expensive to use for solid phase synthesis.14,15 Thus, when it comes to designing, synthesizing, and scaling up production of commercially unavailable, synthetically challenging building blocks, solid-phase synthesis is a less attractive method. Despite these challenges, bipyridines have been studied and analysed for their peptide folding properties.3 The method introduced herein should further facilitate such studies because of its synthetic accessibility, reasonable yields, and inexpensive starting materials.

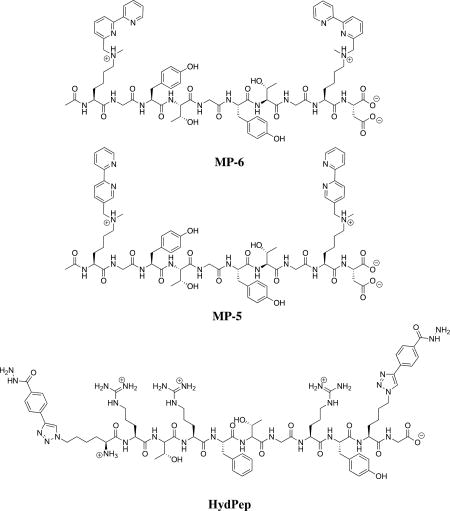

The alkylation approach previously described by our group was seen as a versatile means for synthesizing non-canonical amino acids.3 The commercial availability of alkyl bromide precursors, and the synthetic ease to acquire brominated compounds, makes post-solid phase and alkylation-based strategies an attractive approach. From one sequence containing mono-methylated lysine residues, different side-chains can be incorporated, isolated, and studied for binding/folding properties. Two brominated bipyridines, compounds 1 and 2, substituted at different positions, were used as a case study. We sought a straightforward approach to incorporate these unnatural ligands to the same synthetic peptide, followed by binding and folding studies. The hypothesis was that the methylated lysine would bind to a metal as a third site of a tridentate ligand when alkylated with 2 (SI-Figure 1). This served as further motivation for the alkylation strategy. Thus, MP-5 and MP-6 were synthesized. Additionally, inspired by recent studies demonstrating that aldehyde and hydrazide containing peptides rapidly assemble into complex quaternary structures,16 we pursued even higher-ordered structuring by using a dihydrazide peptide, HydPep.

Results and discussion

Bipyridine ligands commonly participate in coordination stoichiometries of 3:1 for hexacoordinate metals because they are bidentate. Thus, peptides decorated with two bipy ligands modified at position 5 were postulated to form oligomeric species that would be difficult to characterize. On the other hand, peptides with two ligands modified at position 6 could satisfy the six-coordination requirements by acting as tridentate ligands (SI-Figure 1).

The sequence selected for MP-5 and MP-6 came from previously studied peptides from our group used for cyclization of synthetic peptides.8 The combination of serine and threonine increased hydrophilicity, while glycine minimized steric repulsion. Acetylation of the N-terminus facilitated the alkylation of the ε-secondary amine residues. Further, residues such as histidine, arginine, and cysteine, known to bind metal ions, were avoided.17, 18 To characterize metal binding to the peptides we used previously reported UV-Vis and 1H-NMR spectroscopy titrations. The concentration of the titrant at the point where the spectroscopic signals stop changing reports the stoichiometry of the binding/folding.19

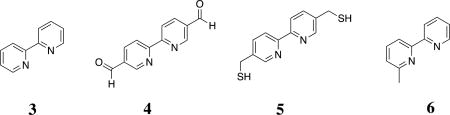

Initially, to validate if our characterization methods would be effective for the peptide assemblies, we performed titrations with small molecules as control species: 5-(bromomethyl)-2,2'-bipyridine (1), 2-2’-bipyridine (3), [2,2'-bipyridine]-5,5'-dicarbaldehyde (4), [2,2'-bipyridine]-5,5'-diyldimethanethiol (5), and 6-methyl-2,2'-bipyridine (6). Compounds 1, 3, and 4 coordinated with Fe2+ in a 3:1 stoichiometry. Compound 5 showed the same stoichiometry with zinc, however compound 6 did not readily bind (SI). This suggested that a methyl group at the 6-position introduced a steric hindrance to the metal complexation. The binding of compound 1 demonstrated that bulkier substituents, like bromide, could be tolerated for ligands substituted at the 5-position (SI). As a result, MP-5 was expected to readily bind metals.

1H-NMR spectra titrations were used to determine the binding stoichiometries, and thereby the folding of MP-5 and MP-6, upon addition of metals. After each addition of metal, successive NMR acquisitions tracked the alterations in the aromatic spectral region. Titrating Fe2+ into MP-6 led to a color change to a rusty red, but notable changes were not observed in the NMR spectra. Weakening of the signal intensity, however, was observed as the sample became more dilute (SI). This result suggested that no significant binding was occurring.

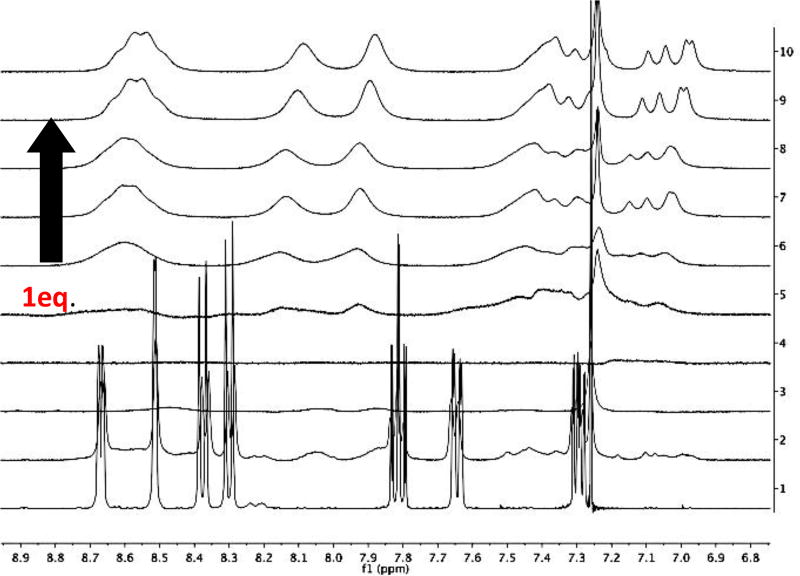

In contrast, the NMR spectra of MP-5 was quite sensitive to the addition of Fe2+ (Figure 1). The spectra, however, were difficult to interpret. The signals remained at constant ppm, but were at their broadest at 1 equivalent of metal. As the concentration of metal increased, additional peaks formed, suggesting the peptides were oligomeric. With more metal added, it is logical that the peptides break apart into singly bound residues.

Figure 1.

MP-5 (2.3 µmole) was dissolved in 600 µL of D2O:MeOD (1:1) (v/v). Iron triflate (4.6 µmole) was dissolved in 180 µL of deuterated solvent. Arrow indicates increase in the equivalents of metal added: 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, 1.8, 2.0, corresponding to the spectra labeled 1 to 10, respectively.

A solution of Fe2+ was also titrated into MP-6 and monitored by UV-Vis spectrophotometry. No absorption change occurred, confirming that position 6 restricts metal binding, likely due to steric hindrance. Therefore, despite a potential third coordination site introduced via an Nε-methyl lysine, a 1:1 metal to peptide stoichiometry proved elusive (SI).

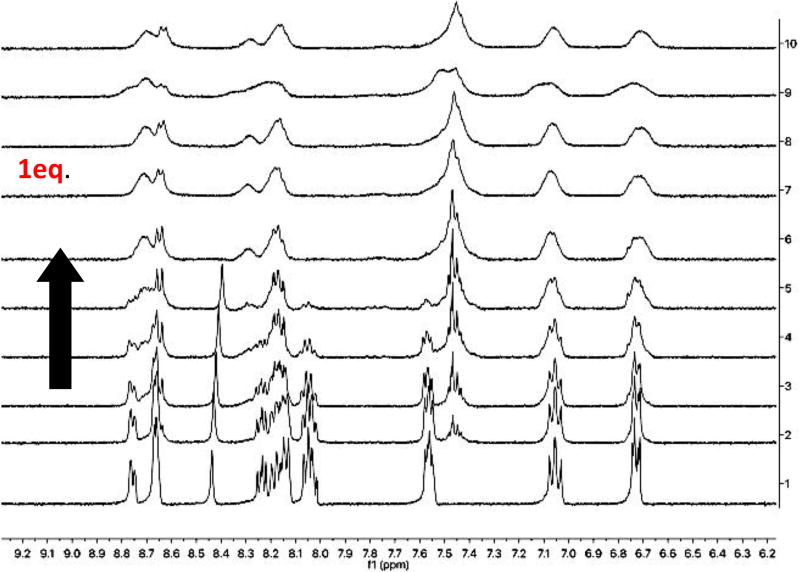

Literature accounts describing binding of metals with functionalized bipyridines and free 2,2’-bipyridine (bipy) have been described, particularly in the context of DNA binding with ruthenium centers.20 Many metals, commonly of group VIII, bind three equivalents of bipy. Thus, to facilitate such a stoichiometry, mixtures of metal, peptide, and compound 3 were analyzed by UV/vis spectroscopy. The aim was to study if free bipy would facilitate binding to MP-6. Despite the addition of a free bipy, MP-6 did not demonstrate any binding (SI). Yet, an interpretable isotherm was acquired with this three-component ensemble for MP-5 (Figure 2). These titrations studies, repeated six times, confirmed a 1:1:1 stoichiometry, just as with the small-molecule titration studies (SI). Further, a mass-spec studies revealed the mass of the cyclized peptide with Fe(II), albeit missing the third bipy. Thus, a total of three stoichiometry was again observed, suggesting aldehydes and thiols do not interfere with complexation. Loss of resolution of peaks is due to diluting of sample after each successive addition of iron.

Figure 2.

MP-5 and free bipy (2.3 µmole) were dissolved in 600 µL of D2O:MeOD (1:1) (v/v). Iron triflate (4.6 µmole) was dissolved in 180 µL of deuterated solvent. Stoichiometry: (1:1:1). Arrow indicates increase in the equivalents of metal added: 0, 0.14, 0.28, 0.42, 0.56, 0.7, 0.84, 0.98, 1.12, 1.26, 1.4, corresponding to the spectra labeled 1 to 10, respectively.

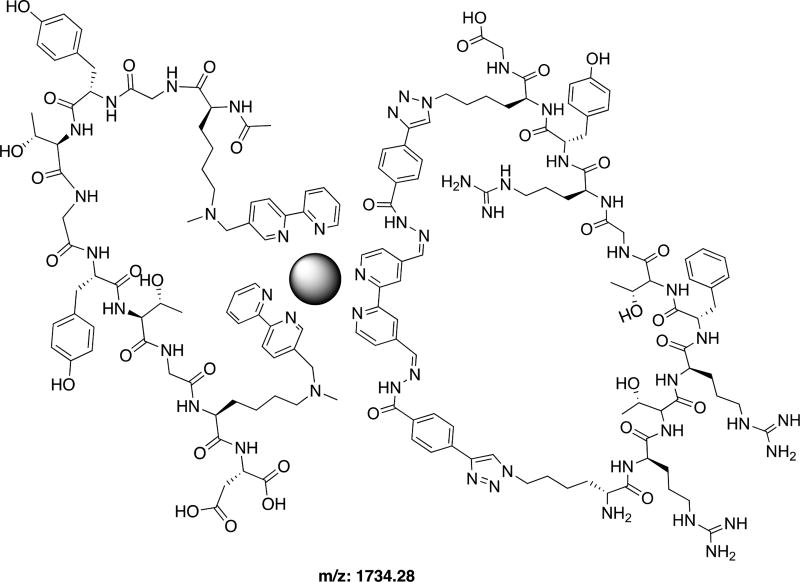

Recently, our group reported a series of 1H-NMR spectral studies confirming orthogonality between four reversible covalent bonds and ligand binding: boronic acid esterification, thiol-conjugate addition, hydrazone formation, and terpyridine complexation with a metal cation.21 Combining peptides with unnatural functionalities that can participate in dynamic reversible covalent bonds is a means to induce folding of synthetic peptides with non-canonical functionalities. It is the dynamic reversibility of these covalent bonds that make these reactions attractive in the studies presented here. These reactions can be considered as intermediate between strong covalent bonds, which locks precursors into a specific arrangement, and of non-covalent interactions, which are often too dynamic to make discrete assemblies—unless they act cooperatively.22 We focused on hydrazone formation with compound 4 for cyclic peptide ligand formation (Figure 3). Compound 4 served as a convenient branching point for grafting further structural complexity using dynamic covalent bonds.18,23 Our confidence to induce quaternary structure formation of peptides was based on our small molecule studies of free bipyridine (SI). With every small-molecule bipy ligand, MP-5 consistently formed interpretable titrations indicating 1:1:1 stoichiometries (SI). Thus, these results suggested the need of a third bidentate coordinating site to ensure one MP-5 bound to only one metal center and a small-molecule ligand. Hence, if the third free-bipy ligand does not impose any steric encumbrance, such as having substitutions at the sixth position, a cyclized peptide containing a single bipy would readily coordinate about a metal center as the third ligand. Therefore, we chose HydPep.

Figure 3.

Representative structure of quaternary control of MP5 and HydPep about Fe2+ with predicted m/z value for [M]2+.

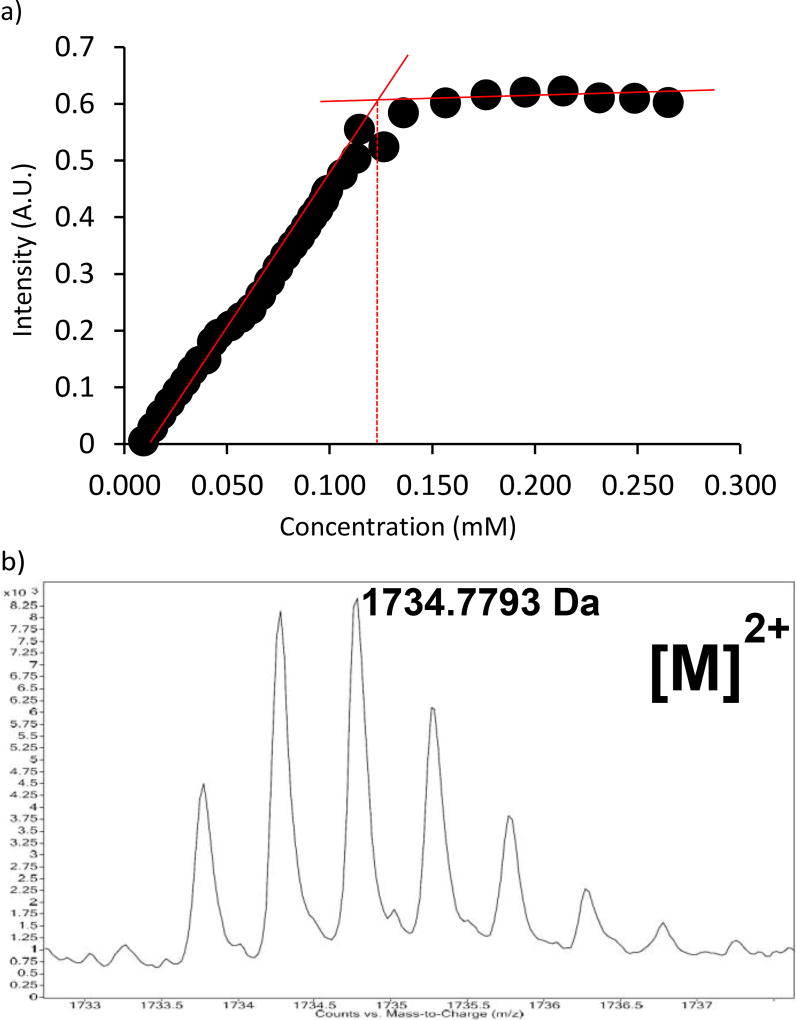

Our first step was to induce cyclization of HydPep in the presence of MP-5 to control for non-specific interactions between the peptides. Compound 5 readily formed a cyclic peptide with HydPep (SI), and in aqueous mixtures at neutral pH, making it an ideal peptide partner for coordination with MP-5. Once cyclized, Fe(II) was titrated into this solution. The clean break occurring at 0.13 mM demonstrated complete complexation of MP-5, Fe2+, and cyclized HydPep in a 1:1:1 ratio (Figure 4a). To further confirm this stoichiometry, high-resolution mass spectrometry was performed. The mass of a cyclic HydPep complexing with the bipyridine-peptide along with an Fe(II) derivative were observed (Figure 4b). Thus, a controlled stoichiometry of one equivalent of a bis(bipy) peptide, one in-situ cyclized dihydrazide peptide with a small molecule dialdehyde, and one Fe(II) metal center led cleanly to a single large, complex, and folded peptide. Therefore, a strategy of combining metal coordination to induce peptide cyclization, combined with reversible covalent bonding, is a promising strategy to build complex artificial peptide quaternary structures.

Figure 4.

a) A titrant solution of Fe2+ (0.6 mM) in (MeOH:H2O) (1:1) (v/v) was titrated to a solution of 0.1 mM cyclic HydPep and MP-5. Stoichiometry: (1:1:1). b) Mass spec result for MP-5 complexed with HydPep. [M]2+.

Several stereochemical isomers of the assemblies presented herein will exist in solution. As with any octahedral complexes, meridial and facial, as well as delta and lambda twists, will be present. Quantifying and controlling the extent of these different species formed was not pursued in the work, but would be an added level of control to be considered in future studies.

Conclusions

Cyclization studies for MP-6 and MP-5 using 1H-NMR and UV-Vis titrations demonstrated that a free bipyridine was required for cyclic folding to occur. MP-5 readily folded, but MP-6 showed no affinity to iron or zinc. This suggested that steric hindrance at the 6-position impeded complexation. Compound 4 served as the necessary third bipyridine ligand that incorporated further complexity, demonstrating a straightforward means for forming higher order structures with synthetic peptides. The alkylation modification approach presented here, allowed for the facile creation of peptides modified with two bipyridine isomers. Future studies will include increasing the diversity of compounds formed by including other orthogonal reactions.

Experimental

General Materials

For automated Fmoc amino solid-phase peptide synthesis, Gly, Thr(tBu), and Tyr(tBu) were purchased from P3 Biosystems. Fmoc-Lys(Nε,Me)-OH was purchased from Chem. Pep. Inc. Fmoc-Lys(N3)-OH was purchased from Chem-Impex, Inc. Fmoc-Gly-Wang resin (0.62 mmol g−1) was purchased from P3 Biosystems. N,N′-Diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) and Oxyma and (ethyl cyano(hydroxyimino)acetate) was purchased from Chem-Impex. DMF and piperidine used for automated solid-phase peptide synthesis were purchased from Fisher Scientific and Sigma-Aldrich. Ammonium acetate and acetic anhydride was purchased from Fisher. Methacrolein and 1-[2-oxo-2-(2-pyridinyl) ethyl] iodide, 6-Methyl-2,2′-dipyridyl, and [2,2'-bipyridine]-4,4'-dicarbaldehyde, and [2,2'-bipyridine]-5,5'-diyldimethanethiol[2,2'-bipyridine]-5,5'-diyldimethanethiol[2,2'-bipyridine]-5,5'-diyldimethanethiol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. N-bromo succinimide (NBS) and azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) were purchased from Acros Organics.

General Instrumentation

A Liberty Blue microwave peptide synthesizer was used for solid-phase peptide synthesis. Preparative HPLC purification of peptides was performed using an Agilent Zorbax SB-C18 Prep HT column 21.2 250 mm; 10 mL min−1, 5–95% MeOH (0.1% FA) in 90 min. Analytical HPLC characterization of peptides was performed using an Agilent Zorbax column 4.6 250 mm; 1 mL min−1, 5–95% MeCN (0.1% TFA) in 35 min (RT). A Gemini C18 3.5 micron 2.1 50 mm was used for online separation; 0.7 mL min−1, 5–95% MeCN (0.1% formic acid) in 12 min (RT). An Agilent Technologies 6530 Accurate Mass QTofLC/MS and a AB Voyager-DE PRO MALDI-TOF were used for high-resolution mass spectra of purified peptides. Solvents used were HPLC grade. A BioTek Cytation3 well plate reader and an Agilent Carey series spectrophotometer were used for UV-Vis titrations. A PowerEase Life technologies electrophoretic setup was used for gel separations of peptides and metallo-peptide complexes.

General Procedure for Peptide Synthesis of MP-5 and MP-6

Synthesis of peptides was performed using standard settings using Liberty Blue software, and using 1 M of DIC and 1 M oxyma used as coupling and bases, respectively. Amino acid solutions were prepared at 200 mM, except for Fmoc-Lys(Nε,Me)-OH which was prepared at 100 mM. Each peptide made was capped using acetic anhydride incorporated into the automated synthesis. After the synthesis, resin was washed with glacial AcOH (5 mL, 3x), DCM (5 mL, 3x), and MeOH (5 mL, 3x). Resins were placed under vacuum overnight. Peptides were cleaved from the resin using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), triisopropylsilane, and nanopure water (95 : 2.5 : 2.5) (4 h). TFA was evaporated and the remaining oil was precipitated with diethyl ether at 0 °C. No further purification of the crude peptide was performed.

HydPep

HydPep was prepared as reported in the literature.

General procedure for alkylation of peptides

Peptides (1 eq.) were alkylated with 5-(bromomethyl)-2,2'-bipyridine (4.4 eqs.) or 6-(bromomethyl)-2,2'-bipyridine (4.4 eqs) in a MeCN, H2O, and MeOH (80:15:5) (v/v/v) solvent mixture, followed by addition of 100 µL of Hunig’s base (DIPEA). The reaction was allowed to stir for 24 hrs at RT. The solution was purified by preparative HPLC. Purified samples were placed on the rotary evaporator to remove organic solvent. The aqueous remnants were frozen at −70 °C and lyophilized overnight.

MP-6

Starting amount: (0.016 mmole). Yield: 38%. HRMS: (M+2H)2+; calcd. 748.35390, obs. 748.35630.

MP-5

Starting amount: (0.015 mmole). Yield: 25%. HRMS: (M+2Na)2+; calcd. 770.33580, obs. 770.33800.

Synthesis Brominated Ligand Precursors

Synthesis of 5-(bromomethyl)-2,2'-bipyridine was prepared using a protocol reported in the literature.24

Synthesis of 6-(bromomethyl)-2,2’-bipyridine was prepared using a protocol reported in the literature.9

Synthesis of Fmoc-L-Lysine(Me, Boc)-OH22

Mono-methylation at the N-position of Lysine followed the indirect pathway22 of mono-benzylation, then methylation via reductive amination with benzaldehyde and formaldehyde, respectively. The benzyl “protecting group” is then removed via palladium-catalyzed hydrogenolysis and replaced with a Boc protecting group for peptide synthesis. Whereas direct mono-methylation produces a mixture of di, mono, and non-methylated variants that are difficult to separate from each other, the indirect pathway produces primarily mono-benzylated product, although di-benzylated and therefore non-benzylated still account for ~30% loss of yield. Methylation then produces ~70% mono-benzylated/mono-methylated product, with about equal percentages of di-methylated and di-benzylated products. These three products in the mixture are easy to separate, due to the hydrophobicity of the benzyl group. The mono-benzylated/mono-methylated intermediate is then subjected to debenzylation with Pd/C/H2 and in situ carbamoylation with Boc anhydride. Further detail can be found in the SI.

Well-plate Titration Experiments19

Stock solutions of ligand peptides (0.6 mM), free biby (0.2 mM), and Fe2+ (0.2 mM).

15 data points (15 wells) were taken for each experiment. To each well 25 µL metal and 25 µL of free bipy was introduced. Increasing amounts of peptide solution were introduced in 10 µL increments. The minimum was 0 µL solution introduced and the maximum was 150 µL introduced with all wells were diluted to a total of 150 µL. Each well was scanned between 300–700 nm. Blanks were composed of the MeOH:H2O (1:1) (v/v).

Changes at 530 nm were monitored for titrations. A plot of concentration vs. change in absorption was made. Stoichiometry was determined by plotting a line along the increasing changes in absorption and a different line where the data points plateaued. The intersection was used to determine the amount of peptide required for optimal binding.

Cuvette UV-VIs Titration Experiments

Titrant solution of Fe2+ (0.6 mM) containing 0.1 mM MP-5 and cyclic HydPep was titrated to a solution containing 0.1 mM of MP-5 and cyclic HydPep.

Changes at 530 nm were monitored. A plot of concentration vs. change in absorption was made. Stoichiometry was determined by plotting a line along the increasing changes in absorption and a different line where the data points plateaued. The intersection was used to determine the amount of metal required for optimal binding.

NMR titration experiments

NMR titrations were performed for both Zn2+ and Fe2+ to confirm UV-Vis titration experiments. MP was dissolved to concentration in (2.3 µmole) 600 µL of D2O:MeOD (1:1) (v/v). Zinc or iron triflate was dissolved 180 µL (4.6 µmole) of deuterated solvent. 600 µL of the peptide solution was introduced to the NMR tube. An NMR was taken initially before the incorporation of any metal. Increment additions were added of metal solution (15 µL, 6x; 30 µL, 3x). After each addition, an NMR experiment was performed, immediately after. Titration of unreacted bipys was performed in a similar fashion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge our funding sources: The National Institute of Health (5DP1GM106408), the Welch Foundation (F1515 to E. M. M.), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA, N66001-14-2-4051), and the Welch Regents Chair to EVA (F-0046). We also gratefully acknowledge Dr. Ian Riddington and Dr. Kristin Suhr from the UT Austin Mass Spec Facility.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: NMR, HRMS, analytical HPLC. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

References

- 1.Young MC, Liew E, Ashby J, McCoy KE, Hooley RJ. Chem. Comm. 2013;49:6331–6333. doi: 10.1039/c3cc42851f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemire JA, Harrison JJ, Turner RJ. Nat. Rev. Micro. 2013;11:371–384. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou R, Wang Q, Wu J, Wu J, Schmuck C, Tian H. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:5200–5219. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00234f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wojtecki RJ, Meador MA, Rowan SJ. Nat. Mater. 2011;10:14–27. doi: 10.1038/nmat2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganguly T, Kasten BB, Bucar D-K, MacGillivray LR, Berkman CE, Benny PD. Chem. Comm. 2011;47:12846–12848. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15451f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albrecht M. Metallofoldamers. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013. pp. 275–302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venkatraman J, Shankaramma SC, Balaram P. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:3131–3152. doi: 10.1021/cr000053z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaes C, Katz A, Hosseini MW. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:3553–3590. doi: 10.1021/cr990376z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murashima T, Tsukiyama S, Fujii S, Hayata K, Sakai H, Miyazawa T, Yamada T. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:4060–4064. doi: 10.1039/b511233h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imperiali B, Fisher SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:8527–8528. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng RP, Fisher SL, Imperiali B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:11349–11356. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishida H, Maruyama Y, Kyakuno M, Kodera Y, Maeda T, Oishi S. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:1567–1570. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernandez ET, Kolesnichenko IV, Reuther JF, Anslyn EV. New J. Chem. 2017;41:126–133. doi: 10.1039/C6NJ02862D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishida H, Inoue Y. Pep. Sci. 2000;55:469–478. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2000)55:6<469::AID-BIP1022>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craik DJ, Fairlie DP, Liras S, Price D. Chem. Bio. Drug Des. 2013;81:136–147. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reuther JF, Dees JL, Kolesnichenko IV, Hernandez ET, Ukraintsev DV, Guduru R, Whiteley M, Anslyn EV. Nat. Chem. 2017;10:45. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu C-H, Lin Y-F, Lin J-J, Yu C-S. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e39252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamashita MM, Wesson L, Eisenman G, Eisenberg D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:5648–5652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dragna JM, Pescitelli G, Tran L, Lynch VM, Anslyn EV, Di Bari L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:4398–4407. doi: 10.1021/ja211768v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonnell U, Hicks MR, Hannon MJ, Rodger A. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008;102:2052–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seifert HM, Ramirez Trejo K, Anslyn EV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:10916–10924. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diehl KL, Bachman JL, Chapin BM, Edupuganti R, Rogelio Escamilla P, Gade AM, Hernandez ET, Jo HH, Johnson AM, Kolesnichenko IV, Lim J, Lin C-Y, Meadows MK, Seifert HM, Zamora-Olivares D, Anslyn EV. Synthetic Receptors for Biomolecules: Design Principles and Applications. The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2015. pp. 39–85. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sales AE, Breydo L, Porto TS, Porto ALF, Uversky VN. RSC Adv. 2016;6:42971–42983. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Esch JH, Hoffmann MAM, Nolte RJM. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:1599–1610. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.