Abstract

Purpose

This study compared treatment patterns of Turkish patients with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who were treated with innovator Remicade® (infliximab [IFX]) and either continued IFX or switched to CT-P13.

Materials and methods

Adult RA patients with ≥1 IFX claim were identified from the Turkish Ministry of Health database. Eligible patients initiated and continued IFX treatment (continuers cohort [CC]) or initiated IFX and switched to CT-P13 (switchers cohort [SC]) during the study period. The initial IFX claim date was defined as the index date. The switch/reference date was defined as the CT-P13 switch date for the SC or a random IFX date during the period of CT-P13 availability for the CC. Cohorts were matched by age, sex, and number of IFX prescriptions during baseline. Patient demographics, discontinuation, and switching were summarized. The baseline period was defined as the period from the index date to the switch/reference date. The follow-up period ranged from the switch/reference date to the end of data availability.

Results

After matching, 697 patients were selected: 605 patients for the CC and 92 patients for the SC. Mean IFX duration for the baseline period was 422 days in the CC and 438 days in the SC. Median time on any infused tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonist therapy was 1,080 days in the CC and 540 days in the SC during the study period. During the follow-up period, discontinuation was lower in the CC (CC=33.9% vs SC=87.5%; P<0.001). The mean time to discontinuation was longer in the CC (CC=276 days vs SC=132 days; P<0.001). A switch to another biologic medication during the follow-up period was observed in 19.0% of patients in the CC (n=115) and 81.5% of patients in the SC (n=75; P<0.001).

Conclusion

Treatment patterns differed between patients prescribed IFX and CT-P13. In Turkey, RA patients maintained on IFX had greater treatment persistence (ie, fewer and later discontinuations) than those who initiated IFX and switched to CT-P13.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, biosimilar, CT-P13, continuer, treatment patterns, discontinuation

Plain language summary

Remicade® (infliximab [IFX; Janssen Biotech, Inc., Horsham, PA, USA]) is a biologic medication used in the management of autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

Biosimilars including CT-P13 are engineered to be similar to the reference biologic medication (IFX); however, differences in cell culture systems and manufacturing processes, as well as the structural complexities of proteins, make it impossible to copy the drug exactly.

The aim of this study is to understand if differences in treatment patterns exist among IFX-treated patients who continued IFX treatment or switched to CT-P13 using the Turkish Ministry of Health database.

RA patients who initiated and continued IFX treatment (continuers cohort) and those who initiated IFX treatment and switched to CT-P13 (switchers cohort) were matched based on age, sex, and mean number of IFX prescription claims during the baseline period.

Study results showed differences in discontinuation and switching rates after switching to CT-P13.

Introduction

Remicade (infliximab [IFX]) is an anti-TNF-α chimeric monoclonal IgG1 antibody used in the management of autoimmune inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis (PsO), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).1 CT-P13 is a biosimilar of IFX, which was first approved in Europe in 2013 and recently approved in the US.2–4 Biosimilars are engineered to be highly similar to the reference biologic medication; however, differences in cell culture systems, manufacturing processes, and the structural complexities of proteins make it impossible to copy an antibody exactly.5 CT-P13 was manufactured with a different cell line that produces a protein with an amino acid sequence identical to the original IFX.6

While physicochemical, pharmacokinetic studies and limited safety studies have been conducted for biosimilar IFX in order to achieve regulatory approvals, few long-term post-marketing studies have been published for these agents in Europe, and post-marketing studies in the US were not mandated. Global post-marketing studies are especially important since little is known about how switching back and forth between biosimilar and innovator molecules may affect the efficacy and safety of these agents. Additionally, very little real-world data exist to describe how frequently switching among these agents occurs and to determine the differences in treatment patterns of innovator and biosimilar IFX, if any. CT-P13 received marketing approval in Turkey in July 2014; reimbursement approval followed ~60–90 days later. This study utilized the Turkish Ministry of Health database to evaluate whether differences in treatment patterns exist among IFX-treated patients who continued IFX treatment or switched to CT-P13.

Materials and methods

Experimental design and data source

This study is a retrospective analysis spanning December 1, 2010–June 1, 2016, using the Turkish Ministry of Health database, a nationwide medical information collection system established under the 2007 Health Budget Law. The de-identified research dataset comprised pharmacy, inpatient, outpatient, and laboratory claims. The data included 17,800 pharmacies, 5,600 general practitioners, 4,500 medical centers, 1,200 government hospitals, and 338 private hospitals, covering ~80% of the population in Turkey. The data have been used in several outcomes research studies.7,8

Patient identification

Adult patients were selected if they had ≥1 diagnosis claim for RA (International Statistical Classification of Diseases, tenth revision, clinical modification [ICD-10-CM] codes M05.X, M06.X) and continuous medical/pharmacy health plan enrollment during the study period from December 1, 2010, to June 1, 2016. Patients were required to have an initial IFX claim verified by a period of ≥12 months without a previous claim for IFX. The initial IFX claim date was designated as the index date. At least one subsequent prescription claim for IFX or CT-P13 during the period of CT-P13 availability was also required; the initial switch from IFX to CT-P13 was required to have occurred within 16 weeks of a prior IFX claim. Patients with a diagnosis claim for pregnancy or cancer during the study period were excluded.

The calendar date of switch was defined as the switch date. A random IFX reference date during the period of CT-P13 availability was selected as a surrogate for the switch date for patients who initiated and continued IFX treatment.9,10 For this study, the date of initial CT-P13 availability was designated as October 1, 2014 (the first observed CT-P13 claim date).

Two cohorts were created. The continuers cohort (CC) consisted of RA patients who initiated and continued IFX treatment; the switchers cohort (SC) consisted of RA patients who initiated IFX and switched to CT-P13. Cohorts were matched using a 7:1 ratio (CC:SC) based on age, sex, and mean number of IFX prescription claims during the baseline period. The baseline period ranged from the index date to the random IFX reference date (CC) or CT-P13 switch date (SC). The follow-up period ranged from the random IFX reference date (CC) or CT-P13 switch date (SC) to the end of data availability.

Study variables

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics were measured, including age, sex, geographical region, baseline concomitant disease, RA-related therapy use, and disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) use. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score and individual comorbidities were also assessed. Outcomes measured for the follow-up period included concomitant DMARDs, RA-related treatments, and dosing, treatment intervals, discontinuation, and switching patterns for IFX and CT-P13. The time to discontinuation of the cohort medication was assessed for the overall study population and for patients with a confirmed discontinuation. Confirmed discontinuation was defined as evidence of a switch to another biologic medication or the absence of a cohort biologic claim for ≥120 days. The proportion of patients continuing infusion of anti-TNF-α for the matched cohorts during the follow-up period was assessed by Kaplan– Meier analysis.

Statistical analyses

Numbers and percentages were provided for dichotomous and polychotomous variables. Mean, median, and SD values were provided for continuous variables. P-values for dichotomous variables were calculated using chi-square tests, and P-values for continuous variables were calculated using the independent-samples t-tests. Statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) Version 9.3.

Ethics approval and informed consent

Since the data used for this study were de-identified and only aggregate results were reported, the study was exempt from the review of an Institutional Review Board.

Results

Baseline descriptive and clinical characteristics

A total of 1,695 patients met the study criteria. After matching for age, sex, and number of IFX prescriptions during the baseline period, a total of 697 patients were selected for analysis. The CC included 605 patients, and the SC included 92 patients. Mean age was 41 years in the CC and 43 years in the SC. During the baseline period, mean (CC=422 days vs SC=438 days) and median (CC=340 days vs SC=377 days) durations of IFX use were similar between the cohorts, as was the number of IFX prescription claims (CC=7.8 vs SC=7.8). Differences in geographical distribution were apparent. A higher proportion of the CC resided in the Marmara region (CC=42.5% vs SC=13.0%). A lower proportion of CC patients resided in the Central Anatolia (CC=18.8% vs SC=43.5%) and the Mediterranean region (CC=12.9% vs SC=20.7%) of Turkey (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of matched patients in the CC and SC

| CC (n=605)

|

SC (n=92)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | |

| Age, years (mean) | 41.1 | 10.3 | 42.5 | 11.8 |

|

| ||||

| Age group, years | ||||

|

| ||||

| 18–30 | 98 | 16.2% | 16 | 17.4% |

| 31–64 | 499 | 82.5% | 72 | 78.3% |

| ≥65 | 8 | 1.3% | 4 | 4.3% |

|

| ||||

| Sex | ||||

|

| ||||

| Male | 296 | 48.9% | 44 | 47.8% |

| Female | 309 | 51.1% | 48 | 52.2% |

|

| ||||

| Geographic region | ||||

|

| ||||

| East Anatolia | 19 | 3.1% | 1 | 1.1% |

| Southeastern Anatolia | 47 | 7.8% | 10 | 10.9% |

| Marmara | 257 | 42.5% | 12 | 13.0% |

| Aegean | 35 | 5.8% | 9 | 9.8% |

| Mediterranean | 78 | 12.9% | 19 | 20.7% |

| Black Sea | 55 | 9.1% | 1 | 1.1% |

| Central Anatolia | 114 | 18.8% | 40 | 43.5% |

|

| ||||

| Baseline Comorbidity Index ≥5% | ||||

|

| ||||

| CCI score | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

|

| ||||

| Individual comorbidities | ||||

|

| ||||

| COPD | 98 | 16.2% | 15 | 16.3% |

| Connective tissue disease (without RA) | 79 | 13.1% | 3 | 3.3% |

| Ulcer | 137 | 22.6% | 14 | 15.2% |

| Diabetes mellitus (type 1 and 2) | 39 | 6.4% | 6 | 6.5% |

| Mild liver disease | 32 | 5.3% | 7 | 7.6% |

| Hypertension | 109 | 18.0% | 14 | 15.2% |

| Depression | 55 | 9.1% | 9 | 9.8% |

|

| ||||

| Concomitant disease | ||||

|

| ||||

| PsA or PsO | 90 | 14.9% | 11 | 12.0% |

| Crohn’s disease | 52 | 8.6% | 5 | 5.4% |

| AS | 374 | 61.8% | 61 | 66.3% |

| Ulcerative colitis | 47 | 7.8% | 7 | 7.6% |

|

| ||||

| Baseline RA-related therapies and DMARDs | ||||

|

| ||||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 63 | 10.4% | 7 | 7.6% |

| Sulfasalazine | 127 | 21.0% | 27 | 29.3% |

| Azathioprine | 82 | 13.6% | 5 | 5.4% |

| Cyclophosphamide | 6 | 1.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Leflunomide | 63 | 10.4% | 10 | 10.9% |

| Methotrexate/methotrexate sodium | 167 | 27.6% | 29 | 31.5% |

| NSAIDs | 521 | 86.1% | 84 | 91.3% |

| Corticosteroids | 464 | 76.7% | 76 | 82.6% |

|

| ||||

| Duration of baseline IFX use | ||||

|

| ||||

| Days (mean) | 422.3 | 329.6 | 437.6 | 336.1 |

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; CC, continuers cohort; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; DMARDs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; IFX, infliximab; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SC, switchers cohort.

There was no significant difference in the CCI scores between the cohorts. No significant differences were observed for the most prevalent comorbid conditions: ulcers (CC=22.6% vs SC=15.2%), hypertension (CC=18.0% vs SC=15.2%), and COPD (CC=16.2% vs SC=16.3%). Likewise, the proportion of patients with concomitant autoimmune diseases such as AS, PsO/psoriatic arthritis (PsA), ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease were similar between the cohorts (Table 1). Despite inclusion based upon a diagnosis code for RA, ~66% of patients in both cohorts had ≥1 diagnosis of AS at some point during the baseline period (CC=61.8% vs SC=66.3%; Table 1). Similar proportions of patients in both cohorts received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; CC=86.1% vs SC=91.3%), corticosteroids (CC=76.7% vs SC=82.6%), methotrexate (CC=27.6% vs SC=31.5%), and sulfasalazine (CC=21.0% vs SC=29.4%; Table 1).

Follow-up period

The mean follow-up period was slightly longer for the CC (CC=16.3 months vs SC=15.1 months; P<0.001) compared to that of the SC. Patterns of concomitant medication use in the follow-up period were generally similar to those in the baseline period in both cohorts.

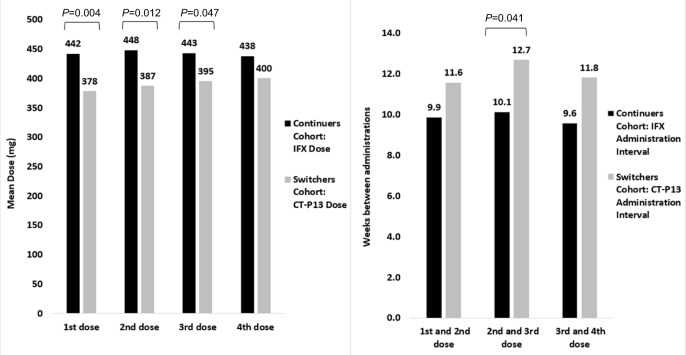

Dosing patterns

The average number of cohort infusions during the follow-up period was significantly greater in the CC (CC=4.8 infusions vs SC=2.9 infusions; P<0.001; Table 2). The mean dose per infusion (DPI) was significantly greater for the CC (CC=450 mg vs SC=380 mg; P<0.001). A similar trend was observed for the first (CC=442 mg vs SC=378 mg; P=0.004), second (CC=448 mg vs SC=387 mg; P=0.012), and third (CC=443 mg vs SC=395 mg; P=0.047) infusions (Figure 1). The overall mean interval between infusions was not statistically different (CC=9.7 weeks vs SC=10.7 weeks). This trend was generally similar when evaluating the intervals between the first and second infusions (CC=9.9 weeks vs SC=11.6 weeks), second and third infusions (CC=10.1 weeks vs SC=12.7 weeks; P=0.041), and third and fourth infusions (CC=9.6 weeks vs SC=11.8 weeks; Figure 1).

Table 2.

Follow-up treatment patterns and utilization for matched continuers and switchers

| CC (n=605) | SC (n=92) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | P-value | |

| Average duration of follow-up period (months) | 16.3 | 2.3 | 15.1 | 2.1 | <0.001 |

| Dosing characteristics | |||||

| No. of infusions in follow-up period | 4.8 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Weeks between administration | 9.7 | 3.7 | 10.7 | 5.7 | NS |

| Switching | |||||

| No. of switchers | 115 | 19.0% | 75 | 81.5% | <0.001 |

| Characteristics of switch (n=605 vs n=92) | |||||

| Golimumab | 24 | 4.0% | 2 | 2.2% | NS |

| Adalimumab | 35 | 5.8% | 5 | 5.4% | NS |

| Etanercept | 30 | 5.0% | 2 | 2.2% | NS |

| Abatacept | 4 | 0.7% | 0 | 0.0% | NS |

| Rituximab | 7 | 1.2% | 0 | 0.0% | NS |

| Anakinra | 1 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | NS |

| Tocilizumab | 14 | 2.3% | 0 | 0.0% | NS |

| CT-P13 | 0 | ||||

| IFX | 66 | 71.7% | |||

| Discontinuation | |||||

| Time to discontinuation (days) | 275.7 | 123.6 | 132.2 | 104 | <0.001 |

| No. of DPI (mg) before discontinuation | 450 | 190 | 380 | 160 | <0.001 |

| No. of patients with discontinuation | 205 | 33.9% | 80 | 87.0% | <0.001 |

| Time to discontinuation for patients who truly discontinued (days) | 117.1 | 78.4 | 98.4 | 59.7 | 0.032 |

| Concomitant DMARD and RA-related treatment | |||||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 53 | 8.8% | 8 | 8.7% | NS |

| Sulfasalazine | 76 | 12.6% | 22 | 23.9% | 0.004 |

| Azathioprine | 78 | 12.9% | 5 | 5.4% | 0.040 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 2 | 0.3% | 1 | 1.1% | NS |

| Leflunomide | 54 | 8.9% | 13 | 14.1% | NS |

| Methotrexate/methotrexate sodium | 143 | 23.6% | 24 | 26.1% | NS |

| Tofacitinib | 7 | 1.2% | 0 | 0.0% | NS |

| NSAIDs | 512 | 84.6% | 81 | 88.0% | NS |

| Corticosteroids | 465 | 76.9% | 71 | 77.2% | NS |

| Duration of any IFX use (IFX or CT-P13) in baseline and follow-up periods | |||||

| Days (mean) | 704 | 375 | 637 | 373 | NS |

Abbreviations: CC, continuers cohort; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; DPI, dose per infusion; IFX, infliximab; NS, not significant; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SC, switchers cohort.

Figure 1.

Medication dose and dosing intervals for matched continuers and switchers during the follow-up period.

Abbreviations: IFX, infliximab.

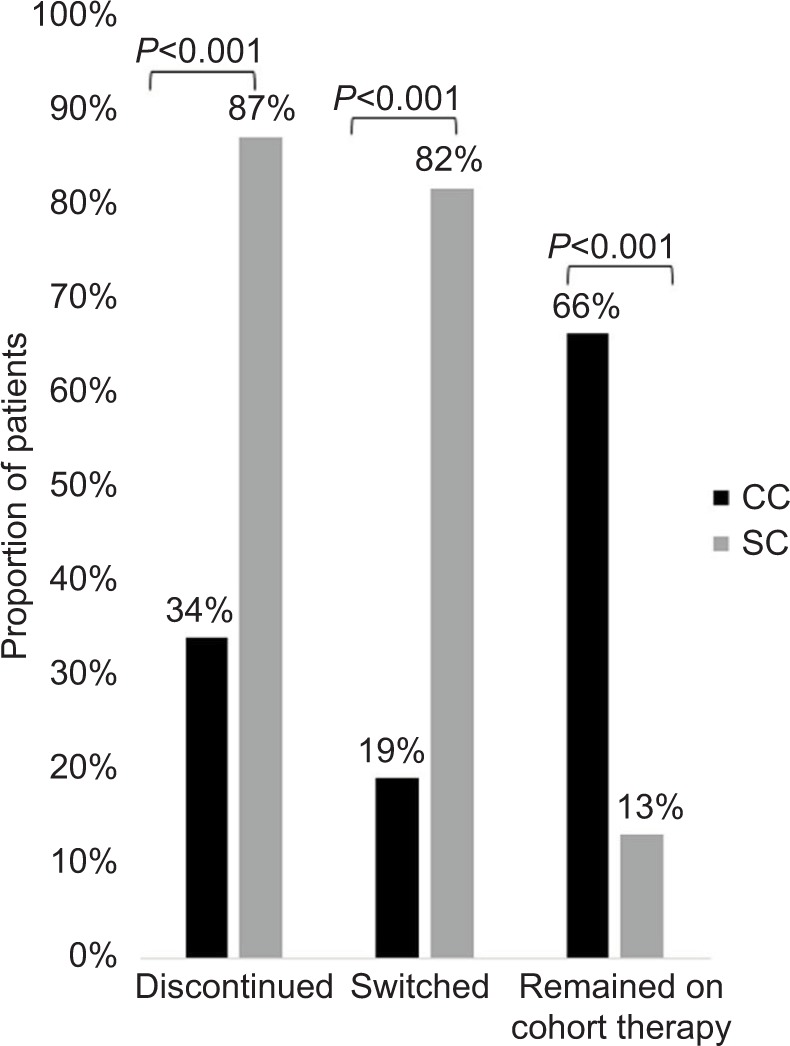

Discontinuation patterns

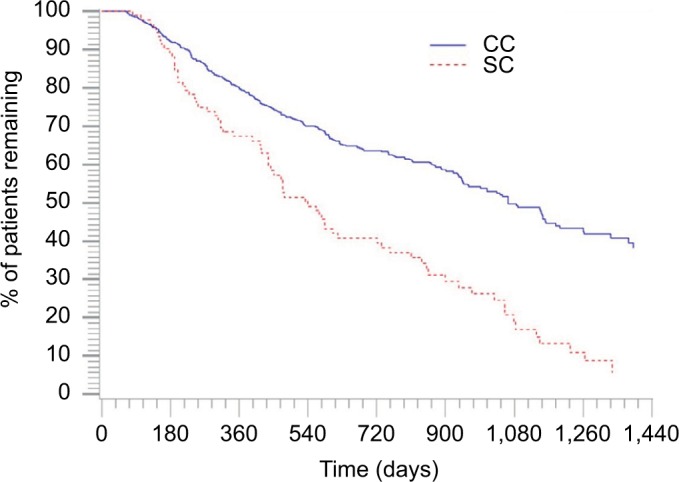

Fewer patients in the CC discontinued therapy during the follow-up period (CC=33.9% vs SC=87.0%; P<0.001; Figure 2), and patients in the CC remained on therapy longer than the patients in the SC. The average time to discontinuation was 275.7 days in the CC and 132.2 days in the SC (P<0.001). Among patients with confirmed discontinuation, the average time to discontinuation was 117.1 days in the CC and 98.4 days in the SC (P=0.032; Table 2). The median continuous use of any IFX during the study (baseline and follow-up) period was 1,080 days and 540 days for the CC and SC, respectively (P<0.001). The results indicate that 50% of the CC continued IFX medication after 1,080 days and 50% of the SC continued any IFX medication (CT-P13 or IFX) after 540 days (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Proportion of matched patients who discontinued, switched, or remained on cohort therapy during the follow-up period.

Abbreviations: CC, continuers cohort; SC, switchers cohort.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curve for any infused anti-TNF-α use for the matched cohorts during the study period.

Note: P-value is <0.001.

Switching patterns

Switches to another biologic medication during the followup period were observed in 19.0% of the CC (n=115) and 81.5% of the SC (n=75; P<0.001; Figure 2). Of the 115 CC patients who switched during the follow-up, 77.4% (n=89) initiated a non-IFX anti-TNF-α medication (ie, golimumab, adalimumab, etanercept) and 23.6% (n=26) initiated a biologic medication with another mechanism of action (Table 2). All 75 SC patients who switched from CT-P13 switched again. Approximately 88% (n=66) of the 75 SC patients who switched reinitiated IFX during the follow-up period; 12% (n=9) of the 75 patients initiated a non-IFX anti-TNF-α (Table 2).

Discussion

The availability of biosimilars in the marketplace has resulted in patients switching from an innovator therapy to a biosimilar in some settings. This retrospective, observational study evaluated treatment patterns for IFX-treated RA patients who either continued IFX or switched to CT-P13. Two notable findings were made in this study. First, among a large national population database, 697 matched IFX-treated RA patients were identified, and only a small proportion of them (13%; n=92) were initially switched to CT-P13. The low switching rates from IFX to CT-P13 may be a result of several factors. Such factors, unmeasured in our study, could include physician or patient choice, comfort level with a product recently marketed, lack of formulary or tender-mandated switching, availability of drug supply, or a combination of these or other factors, including clinical factors.

Also noteworthy, treatment persistence during the followup period was significantly higher for patients who continued IFX compared to patients who switched from IFX to CT-P13. Differences in dosing patterns between IFX and CT-P13 were observed in this study, with the CC receiving a statistically significantly greater number of vials per infusion; however, the extent to which this might lead to longer persistence in the CC is unknown.

A few other small observational studies concerning rheumatologic and IBD conditions (generally lacking control arms) have been published, many of which also showed higher-than-expected discontinuation rates after a patient switched to CT-P13.18,19 Persistency associated with a systematic switch from IFX to CT-P13 for nonmedical reasons was reported for 260 patients with IBD, RA, or axial spondyloarthropathy in France. In this cohort of patients, the mean time on innovator IFX therapy was 5.8 years prior to the biosimilar switch; after the biosimilar switch, 23% discontinued before the fourth biosimilar infusion over a follow-up period of ~34 weeks. Reasons for biosimilar discontinuation related primarily to lack of efficacy, and 80% of patients who discontinued biosimilar IFX were re-established on innovator IFX.11 This is similar to our study finding where 88% of patients who discontinued biosimilar IFX reinitiated innovator IFX. Similar findings were also noted in a study of 211 rheumatology patients who switched for nonmedical reasons (ie, reasons other than medication intolerability or treatment failure) from innovator to biosimilar IFX in the Netherlands.12 In this study, within 6 months of switching to biosimilar IFX, 23% of these patients discontinued. Primary reasons for discontinuation were reported as adverse events (n=25 of 75 patients); in some cases, patients reported a lack of efficacy. Notably, 77% (34 of 44 patients) of those who discontinued were reinitiated on innovator IFX.12 Additionally, an observational study of nonmedical switching in 802 rheumatology patients in the DANBIO registry reported discontinuation in 132 patients (16%) within 1 year of switching. The primary reasons for discontinuation were cited as a lack of efficacy in 54% of patients and as adverse events in 28% of patients.13

Consistent with observational studies conducted in the post-biosimilar approval environment, randomized controlled trials also point to possible disease-specific differences in outcomes between innovator and biosimilar IFX. For example, in an extension study of PLANETAS, higher proportions of treatment-emergent adverse events, including infections,were observed in AS patients treated with CT-P13, findings which were not observed in RA.14,15 Likewise, the NOR-SWITCH study evaluated outcomes associated with switching to biosimilar IFX in ~500 patients using a randomized, controlled, blinded design with various chronic inflammatory diseases over 52 weeks. The primary end point of the trial was disease worsening as determined by composite measure or physician/patient consensus. Although overall results for the pooled population showed that switching to biosimilar was non-inferior to maintenance of innovator IFX, apparent differences in rates of disease worsening in disease subgroups were noted.16

The use of observational data to assess patient characteristics and medication treatment patterns is a widely accepted practice. Nonetheless, studies using health care claims databases have inherent limitations. In this study, reasons for treatment continuation, discontinuation, or switch were not available in the database. Studies designed to understand the reasons why patients persist on IFX rather than switch to CT-P13, as well as studies using different data sources or methodologies, will be particularly important for interpreting these results. However, it is possible that a switch to the biosimilar may have occurred due to the tendering of pharmaceuticals, which is known to occur in some European hospitals. Pharmaceutical products are purchased based on the best bid and then prescribed based on their availability.17 Additionally, variation and inconsistencies in data coding may be present. In this study, a significant proportion of RA patients also had a diagnosis code for AS, complicating our ability to confirm the disease state for which the patients received biologic medication. In addition, several strengths of this analysis are also noted. Specifically, patients in the CC and SC were matched based on age, sex, and duration of IFX therapy during the baseline period to reduce the likelihood that differences in these variables would impact study observations. Clinical characteristics of the two groups were generally comparable to other variables such as comorbidities and concomitant medications. Further, this study evaluated discontinuation based upon total time on each individual product as well as total time on any IFX and confirmed that the switch to CT-P13 reduced overall persistence in the population studied. Additionally, this study used a dataset consisting of ~80% of the Turkish population, which allowed a large overall study sample reflective of all regions within Turkey and represents the largest such study to our knowledge. Finally, this study used a methodology that allowed us to control for time on therapy and a sufficient post-switch observation period (>1 year) to reliably estimate treatment patterns in the population.

These findings provide relevant and novel information about real-world utilization of an infliximab biosimilar in Turkey. Although reasons for discontinuation and clinical status were not available in the dataset, the apparent differences in discontinuation and switching rates in patients after switching to CT-P13 in this study, which were consistent with other studies, are significant and warrant further post-marketing analysis to assess the extent to which clinical or nonclinical factors contribute to lower persistency with CT-P13.

Data availability

Data supporting the results are not publicly available as they are proprietary to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance was provided by Michael Moriarty of STATinMED Research.

The abstract for this study was previously presented at the 2017 American College of Rheumatology/Association of Rheumatology Professionals Annual Meeting, November 3–8, 2017, in San Diego, CA, as a poster presentation with interim findings and was published online in the ACR/ARHP archive Arthritis Rheumatol at https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/analysis-of-real-world-treatment-patterns-in-a-matched-sample-of-rheumatology-patients-with-continuous-infliximab-therapy-or-switched-to-biosimilar-infliximab/. This study was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Footnotes

Disclosure

AO and LX are paid employees of STATinMED Research, which is a paid consultant to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. YY is an employee of New York University and was a paid consultant to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, in connection with this study and the development of this manuscript. During the conduct of this study and the drafting of this manuscript, IS was an employee of Guven Hospital and was a paid consultant to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. LAE, KG, and AT are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and are stockholders in Johnson & Johnson. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Benhar I, et al. Cross-immunogenicity: antibodies to infliximab in Remicade-treated patients with IBD similarly recognise the biosimilar Remsima. Gut. 2016;65(7):1132–1138. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blair HA, Deeks ED. Infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13; Infliximab-dyyb): a review in autoimmune inflammatory diseases. BioDrugs. 2016;30(5):469–480. doi: 10.1007/s40259-016-0193-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jha A, Upton A, Dunlop WC, Akehurst R. The budget impact of bio-similar infliximab (Remsima®) for the treatment of autoimmune diseases in five European countries. Adv Ther. 2015;32(8):742–756. doi: 10.1007/s12325-015-0233-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GaBI Online [webpage on the Internet] Biosimilar Infliximab Receives Approval in Japan and Turkey. 2014. [Accessed September 17, 2015]. Available from: http://www.gabi-online.net/Biosimilars/News/Biosimilar-infliximab-receives-approval-in-Japan-and-Turkey.

- 5.Food and Drug Administration Guidance for Industry: Scientific Considerations in Demonstrating Biosimilarity to a Reference Product (Draft Guidance) 2012. [Accessed February 6, 2018]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM291128.pdf.

- 6.Kang YS, Moon HH, Lee SE, Lim YJ, Kang HW. Clinical experience of the use of CT-P13, a biosimilar to infliximab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a case series. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(4):951–956. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3392-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baser O, Baser E, Altinbas A, Burkan A. Severity index for rheumatoid arthritis and its association with health care costs and biologic therapy use in Turkey. Health Econ Rev. 2013;3(1):5. doi: 10.1186/2191-1991-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baser O, Burkan A, Baser E, Koselerli R, Ertugay E, Altinbas A. Direct medical costs associated with rheumatoid arthritis in Turkey: analysis from National Claims Database. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(10):2577–2584. doi: 10.1007/s00296-013-2782-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Psaty BM, Heckbert SR, Koepsell TD, et al. The risk of myocardial infarction associated with antihypertensive drug therapies. JAMA. 1995;274(8):620–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García Rodríguez LA, Jick H. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation associated with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Lancet. 1994;343(8900):769–772. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91843-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avouac J, Moltó A, Abitbol V, et al. Systematic switch from innovator infliximab to biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory chronic diseases in daily clinical practice: The experience of Cochin University Hospital, Paris, France. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;47(5):S004930436–5. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.10.002. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tweehuysen L, van den Bemt BJF, van Ingen IL, et al. Subjective Complaints as the Main Reason for Biosimilar Discontinuation After Open-Label Transition From Reference Infliximab to Biosimilar Infliximab. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(1):60–68. doi: 10.1002/art.40324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glintborg B, Sørensen IJ, Loft AG, et al. A nationwide non-medical switch from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in 802 patients with inflammatory arthritis: 1-year clinical outcomes from the DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(8):1426–1431. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park W, Yoo DH, Miranda P, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 compared with maintenance of CT-P13 in ankylosing spondylitis: 102-week data from the PLANETAS extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(2):346–354. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoo DH, Prodanovic N, Jaworski J, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13 (biosimilar infliximab) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparison between switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 and continuing CT-P13 in the PLANETRA extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(2):355–363. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jørgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2304–2316. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leopold C, Habl C, Vogler S. Results from the Country Survey. Vienna: ÖBIG Forschungsund Planungs GesmbH; 2008. [Accessed July 1, 2018]. Tendering of Pharmaceuticals in EU Member States and EEA Countries. Available from: https://ppri.goeg.at/Downloads/Publications/Final_Report_Tendering_June_08.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tweehuysen L, van den Bemt BJF, van Ingen IL, et al. Subjective Complaints as the Main Reason for Biosimilar Discontinuation After Open-Label Transition from Reference Infliximab to Biosimilar Infliximab. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(1):60–68. doi: 10.1002/art.40324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glintborg B, Sorensen IJ, Loft AG, et al. A nationwide non-medical switch from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in 802 patients with inflammatory arthritis: 1-year clinical outcomes from the DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(8):1426–1431. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the results are not publicly available as they are proprietary to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.