Abstract

Silicon quantum dot spin qubits provide a promising platform for large-scale quantum computation because of their compatibility with conventional CMOS manufacturing and the long coherence times accessible using 28Si enriched material. A scalable error-corrected quantum processor, however, will require control of many qubits in parallel, while performing error detection across the constituent qubits. Spin resonance techniques are a convenient path to parallel two-axis control, while Pauli spin blockade can be used to realize local parity measurements for error detection. Despite this, silicon qubit implementations have so far focused on either single-spin resonance control, or control and measurement via voltage-pulse detuning in the two-spin singlet–triplet basis, but not both simultaneously. Here, we demonstrate an integrated device platform incorporating a silicon metal-oxide-semiconductor double quantum dot that is capable of single-spin addressing and control via electron spin resonance, combined with high-fidelity spin readout in the singlet-triplet basis.

Significant progress has been made developing the different methods needed for a spin-based quantum computer but the challenge of integrating them remains. Fogarty et al. present a system with single-spin addressability, spin-spin interactions and high-fidelity readout that provides a scalable foundation for error-corrected devices.

Introduction

The manipulation of single-spin qubits in silicon, using either ac magnetic1,2 or electric3–6 fields at microwave frequencies, has been a powerful driver of progress in the field of solid state qubit development, in part due to the sophistication of microwave technology which allows convenient two-axis control of the qubit via simple phase adjustment, and the generation of complex pulse sequences for dynamical decoupling. This has resulted in high-fidelity single-qubit gates2,4–7 and initial two-qubit gates now realised in a variety of structures8–10. To date, all demonstrations of single-shot readout in silicon systems employing spin resonance1–4,6 have utilized single-spin selective tunnelling to a reservoir11. While convenient, this reservoir-based readout approach is not well suited to gate-based dispersive sensing12, which has significant advantages in terms of minimizing electrode overheads for large-scale qubit architectures. In contrast, readout based on Pauli spin blockade13 in the singlet–triplet basis of a double QD14 is compatible with dispersive sensing and, when combined with an ancilla qubit, can be used for parity readout in quantum error detection and correction codes15–17. Moreover, because singlet–triplet readout can provide high-fidelity spin readout at much lower magnetic fields than single-spin reservoir-based readout11, it allows spin-resonance control to be performed at lower microwave frequencies, which will benefit scalability.

Qubits based on singlet–triplet spin states were first demonstrated in GaAs heterostructures14,18 and have now been operated in a variety of silicon-based structures19–23. High-fidelity single-shot singlet-triplet readout has also recently been demonstrated in various silicon systems22,24,25.

Here, in order to combine the ability to address individual spin qubits using ESR with the voltage-pulse-based detuning control and high-fidelity readout of pairs of spins in the singlet-triplet basis, we employ a 28Si metal-oxide-semiconductor (SiMOS) double quantum dot device26,27 (Fig. 1a, b) with a microwave transmission line that can be used to supply ESR pulses, similar to one previously used for demonstration of a two-qubit logic gate8. The device also includes an integrated single-electron-transistor (SET) sensor to achieve the single-charge sensitivity required for singlet–triplet readout. Electrons are populated into the two quantum dots (QD1 and QD2) with occupancy (N1, N2) using positive voltages on gates G1 and G2. An electron reservoir is induced beneath the Si–SiO2 interface via a positive bias on gate ST, which also serves as the SET top gate. The reservoir is isolated from QD1 and QD2 by a barrier gate B (see Fig. 1a, b).

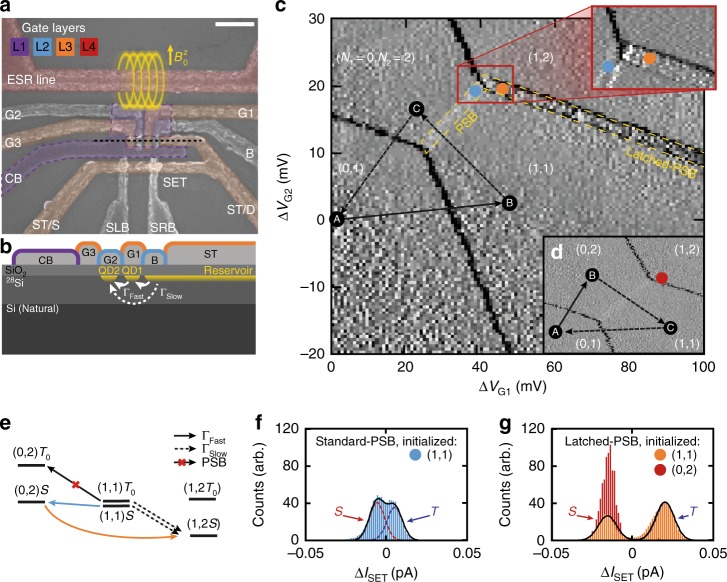

Fig. 1.

Silicon double quantum dot with latched Pauli spin blockade readout. a False-colored scanning electron micrograph of the device architecture. Dots are created under G1 and G2 electrodes and situated in the centre of the confinement gap. Scale bar is 200 nm. b Cross section illustrating dots under G1 and G2, which are tunnel-coupled with fast and slow tunnel rates ΓFast and ΓSlow to an electron reservoir under gate ST. This reservoir is located on the drain (D) side of the sensor. c Cyclic pulsing19,28 (arrows) through sequence A(0, 1)-B(1, 1)-C, where the location of point C is rastered to form the image, reveals latched spin blockade features (orange dot & top zoom-in). Shown is the differential transconductance d(ΔISET)/d(ΔVG1), where ΔISET is the difference in SET current recorded at points B and C. d When point B lies in the (0, 2) charge region, no blockade is observed, as expected for an initial singlet state. e Observation of state-latching of the G2 dot is due to weak coupling to the reservoir. In order to populate the (1, 2) state, the existing (1, 1) state must co-tunnel via (0, 2) where PSB exists. If the state is not blocked (i.e. the state) then an electron is free to tunnel from the reservoir to fill G1. Otherwise, the tunnelling from the reservoir is blocked, resulting in a spin-to-reservoir charge state conversion. f Histogram of ΔISET recorded at Standard-PSB readout location indicated by the blue marker on map d. g Histogram of ΔISET recorded at Latched-PSB readout location for B(1, 1) (orange) and B(0, 2) (red); there is a clear increase in sensitivity provided by the Latched-PSB readout

Results

Single-shot singlet–triplet readout

Figure 1c shows the stability diagram of the double QD system in the charge regions (N1, N2) where we operate the device. When two electrons occupy a double quantum dot, the exchange interaction results in an energy splitting between the singlet (S) and triplet (T−,T0, T+) spin states. The exchange interaction can be controlled by electrical pulsing on nearby gates, providing a means to initialize, control and read out the singlet and triplet states14. At the core of singlet–triplet spin readout is the observation of Pauli spin-blockade (PSB)19,28–31. When pulsing from the (1, 1)→ to (0, 2) charge configurations, the QD1 electron tunnels to QD2 only when the two spatially separated electrons were initially in the singlet spin configuration. The triplet states are blockaded from tunnelling due to the large exchange interaction in the (0, 2) charge configuration. The blockade is made observable on the stability diagram by applying a pulse sequence19,28 to gates G1 and G2 as depicted in Fig. 1c. After first flushing the system of a QD1 electron to create the (0, 1) state at A, a (1, 1) state at B loads a randomly configured mixture of singlet and triplet states (solid arrow in Fig. 1c). The current through the nearby single-electron-transistor (SET) is recorded at this position, tuned to be at the half-maximum point of a Coulomb peak. The system is then ramped to a variable measurement point (dashed arrows in Fig. 1c, d) where the SET current is measured again. A map of the comparison current ΔISET between these two points is created, where the derivative in sweep direction d(ΔISET)/d(ΔVG1) (Fig. 1c) decorrelates the capacitive coupling of the control gates to the SET island. A change in the charge configuration marks a shift in the SET current, clearly observed as bright/dark bands. The bright band in the centre of the (1,1)–(0,2) anti-crossing of Fig. 1c is consistent with PSB, where the blockade triangle is restricted to a narrow trapezoidal area, bounded by state co-tunnelling via the reservoir and the first available excited triplet state19.

The charge sensor design used (Fig. 1a) is relatively insensitive to inter-dot charge transitions, due to the symmetry of the QD1 and QD2 locations with respect to the SET island32. In order to enhance the blockade signal for this layout, we employ state-latching using the nearby electron reservoir33. Recent studies of reservoir charge state latching22,24 and intermediate excited states34 in semiconductor quantum dot devices have led to methods to reduce readout error by almost an order of magnitude22. A variant of this state latching is observed and utilized here.

The latching is produced via asymmetric couplings of the two dots to the common electron reservoir33, where a (1, 1)-(1, 2) dot-reservoir metastable charge state is produced via a combination of the low tunnel rate between QD2 and the reservoir (shown as ΓSlow in Fig. 1b) and co-tunnelling between QD1, QD2 and the reservoir (ΓFast in Fig. 1b). The latching results in the prominent feature observed at the (1, 1)-(1, 2) transition in Fig. 1c. In contrast, when the system is initialized in the (0, 2) charge configuration, the singlet state is prepared robustly due to large energy splitting, and the resulting map in Fig. 1d has no latched PSB region, as expected. The energy splitting between the (0, 2) singlet ground state and first available triplet state is measured to be (1.7 ± 0.2)% of the charging energy EC (see Supplementary Notes 1 and 2, Supplementary Figs. 1, 2). Typically for this device design EC ~ 10–20 meV35, indicating that this splitting exceeds electron thermal energies by two orders of magnitude. The first available triplet here is likely the first excited valley state35–37. To compare the visibility of the standard PSB and latched PSB, histograms of ΔISET are shown in Fig. 1f, g respectively. We find that state latching increases our measurement visibility from around 70 to 98%, reducing the misidentification error by more than 16-fold for this SiMOS device layout (see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3). We note that this measurement fidelity of FM = 99% does not include errors that occur during the evolution from a separated (1, 1) charge state to the blockade region, which we discuss in more detail below.

Singlet–triplet Hamiltonian for Silicon-MOS qubits

The large valley splitting in SiMOS devices8,35 allows us to restrict ourselves to the lowest valley state when considering spin dynamics near the (0, 2)–(1, 1) anti-crossing, which we now address. These dynamics are governed by a Hamiltonian in which single-spin distinguishability and exchange are in competition. Single-spin distinguishability arises from the varying Zeeman energy between each dot, interpreted as a site-specific effective g-factor and resulting in an energy difference δEZ = . For high in-plane magnetic field, the varying effective g-factors result from a combination of interface spin-orbit terms, which depend on local strain, electric fields, and the atomistic details of the oxide interface35,38,39. Further, recent studies have shown that this Hamiltonian parameter can be modulated by the direction of the applied field with respect to the crystallographic axis23. In previous devices we have observed g-factor differences between QDs as large as 0.5%8; at high-field, Overhauser contributions to δEZ are negligible in isotopically purified samples. At lower magnetic fields, magnetic screening from the superconducting aluminum gates may also contribute significantly to δEZ40. For these experiments, the scale of δEZ is predominantly set by choice in the magnitude of the external magnetic field; however, inevitable microscopic dot-to-dot variation in this parameter for future qubit arrays would best be handled by calibration and refocusing methods15.

The Hamiltonian term in competition with the Zeeman gradient is kinetic exchange, which lowers the energy of the spin singlet energy by an amount J(ε) due to interdot tunnelling. In the standard Fermi-Hubbard model, J(ε) is proportional to for large ε, where tc(ε) is the inter-dot tunnel coupling and ε combines the on-site charging energy and electrochemical potential difference between the two dots41 (Supplementary Note 3). In previous experiments8 on a similar SiMOS two-qubit device the tunnel coupling at the anti-crossing was estimated as MHz. For both devices, tc at the anti-crossing is fixed, set by the device geometry. This parameter can be made tunable via the incorporation of exchange gates42 into the SiMOS architecture. In this model, the ground-state singlet is hybridized between (0, 2) and (1, 1) charge states as = + , where . Again neglecting higher energy valley or orbital states, the spin-triplet states with two-spin angular momentum projection m = 0, ±1 are fully separated in the (1, 1) charge state. Besides being split from the m = 0 states by the mean Zeeman energy, , the states may couple to the hybridized singlet states by local magnetic fields which are orthogonal to the average applied field, as well as by spin orbit coupling. We summarize such terms by a spin-flipping term Δ(θ).

Hence in the basis , the approximate effective Hamiltonian is written (Supplementary Note 3)

| 1 |

A typical energy spectrum of this Hamiltonian as a function of detuning ε is shown in Fig. 2a for small magnetic fields, Bz ~ J(ε)/gμB.

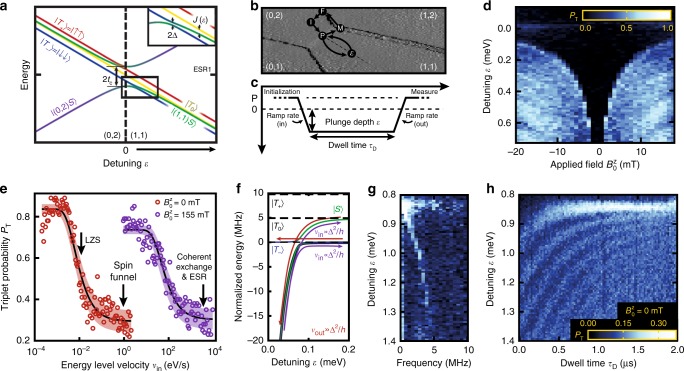

Fig. 2.

Mapping and control of singlet T− triplet anti-crossing. a Energy diagram for the five lowest energy states near the (0, 2)–(1, 1) anti-crossing represented in the singlet-triplet basis. b, c Five-level pulse sequence used in panels d, e and g. b A state is initialised by moving from M, through point F where rapid tunnelling occurs with the reservoir, to point I. From point P, we plunge into the (1,1) region to probe the anti-crossing, and return via P to then move to the latched spin blockade measurement point at M. c Plunge depth into (1, 1) between P and ε as a function of time, illustrating experimental variables including ε detuning, ramp rates and dwell time. d A characteristic spin funnel is observed where the SH/T− state degeneracy results in a relaxation hotspot. e The SH/T− coupling strength Δ(θ) is characterized by performing a single passage Landau–Zener excitation experiment43 at two different applied magnetic field settings. Here, the x-axis indicates the rate of change of the SH/T− energy separation as extracted from measurements of this energy difference vs. voltage and the voltage ramp rate into (1, 1). The increase of this rate (known as the energy level velocity ν) acts to preserve the initial state following the Landau–Zener formula, to which we fit to extract (see text). Solid lines show the fit while shaded regions are a 95% confidence interval. Arrows indicate the energy level velocity used for given experiments. f Energy diagram representation for the effect of varying ramp rate νin with respect to Δ as in e while keeping νout diabatic. g Fourier transform of h Landau–Zener–Stueckelberg interference pattern produced by semi-diabatic double-passage through the S/T− anti-crossing under zero-field Bz offset

Characterizing the singlet-triplet Hamiltonian

The anti-crossing between the and states due to Δ(θ) can be used to map out the energy separation as a function of small detuning ε by performing a spin funnel experiment14. Here, we initialize in a (0, 2) singlet ground state, , and pulse toward the spatially separated , as shown in Fig. 2b, c. By varying the applied magnetic field while dwelling at various values of detuning ε, the location of the anti-crossing can be mapped out via the increased triplet probability PT (Fig. 2d) due to mixing under Δ(θ). Ramping across the anti-crossing causes a coherent population transfer between and due to Landau–Zener tunnelling43 proportional to , characterized by the ratio of Δ(θ) to the energy level velocity ν = . As the ramp rate rises the singlet state is increasingly maintained (see Fig. 2f) and so the triplet return probability PT falls, as we observe in Fig. 2e. By fitting this data (Supplementary Note 4) we estimate at the location of the minimum energy gap is (196 ± 6) kHz at = 0 (an offset field of = −1.04 ± 0.06 mT is estimated from spin funnel asymmetry). Further = 16.72 ± 1.64 MHz at = 155 mT, where the uncertainty here (and elsewhere) corresponds to 95% confidence intervals.

There are a number of possible processes that can contribute to Δ in the silicon-MOS platform. For 800 ppm nuclear-spin-1/2 29Si in the isotopically enriched 28Si epilayer44, we expect random hyperfine fields in all vector directions with root-mean-square of order 50 kHz20 for unpolarized nuclei, so this may contribute to Δ. However, other effects may have a comparable contribution. At low (≲50 mT), Meissner effects from the superconducting aluminum gates can provide transverse local magnetic fields at the location of the QDs; contributions to δBz from this effect of up to a few MHz have been reported40. Further, off-diagonal terms in the difference between the electron g-tensors can contribute to coupling between (1, 1) states. Finally, in the presence of inter-dot tunnelling, the interface spin–orbit interaction provides a separate contribution to Δ, leading to estimated couplings of tens of kHz at low-. Detailed studies on magnetic field magnitude and angle dependence, such as those performed to isolate hyperfine from spin–orbit contributions in nuclear-rich materials such as GaAs45,46, are required to separate and explore each of these individual effects.

We can further characterize the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) at much larger detuning ε than is accessible via the spin funnel by performing a Landau–Zener–Stueckelberg (LZS) interference experiment18,43 (Fig. 2g, h). This is performed at = 0, but the residual magnetic field present, which may include some nuclear polarization47 is sufficient to split the and states. By setting the ramp rate across the / anti-crossing to , an approximately equal superposition of both states is created. Dwelling for varying times τD and detunings ε results in a Stueckelberg phase accumulation ϕ = , with the energy of the state. Depending on the accumulated phase, the returning passage through the anti-crossing either constructively interferes, resulting in the blockaded , or destructively interferes, bringing the system back to . By keeping ν constant throughout the experiment the Fourier transform (Fig. 2g) of the interference pattern (Fig. 2h) directly extracts the energy separation as a function of detuning. In future experiments, this Fourier transform could also be spectroscopically resolved via microwave excitation across the SH/T− transitions, either using our integrated ESR control or via photon-assisted tunnelling48.

We now investigate exchange between the hybridised singlet and unpolarized triplet by applying an external magnetic field = 200 mT to strongly split away the ∣T±⟩ triplet states. At these fields the Zeeman energy difference δEZ dominates exchange J(ε) deep in the (1, 1) region, and the eigenstates there become and , as depicted in Fig. 3a. Maintaining a ramp rate ν fast enough to be diabatic with respect to Δ, but slow enough to be adiabatic with respect to tc(ε), ensures adiabatic preparation of a ground state or , depending upon the sign of δEZ = . At = 200 mT we expect the Meissner effect to be quenched, so that δEZ is dominated by the effective g-factor difference between the dots.

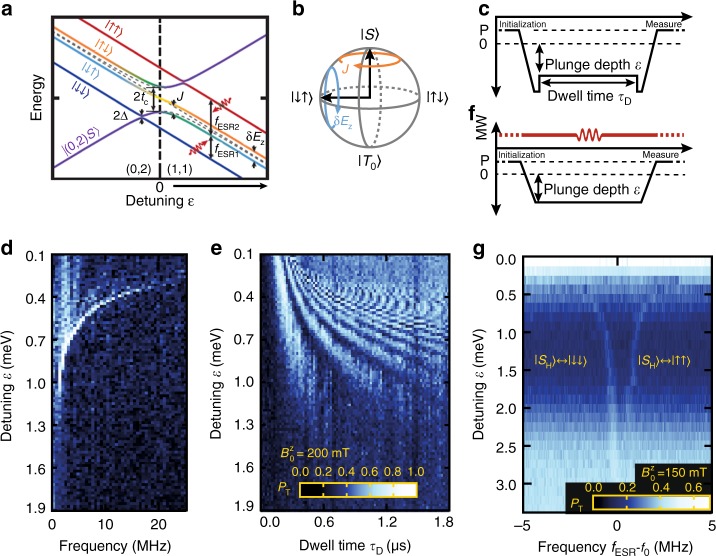

Fig. 3.

Exchange drive oscillations and individual electron ESR at low field. a Energy diagram for the five lowest energy states near the (0, 2)–(1, 1) anti-crossing represented in the spin basis. Compared to Fig. 2a, an increased magnetic field splits off polarized triplets while δg due to the SO coupling breaks the degeneracy producing δEZ. b Bloch sphere representation of the qubit showing effect of the Heisenberg exchange J and δEZ c, d Coherent Rabi oscillations between and states, driven by exchange J. c Pulse sequence for data in d and e; adiabatic ramp (diabatic through the SH/T− crossing) prepares (assuming g2 > g1). Diabatic pulses back to the high exchange region then causes coherent evolution of the state for a period of variable time/depth. The resulting change in population of is mapped back to using the inverse adiabatic ramp. d Fourier transform of time series e which shows exchange driven oscillations between the and states. f Pulse sequence used for data in g. g Triplet probability as a function of detuning ε and applied ESR frequency with f0 = 4.205 GHz. ESR spin rotations of the spin in the left dot (upper branch) and right dot (lower branch), using an on-chip microwave ESR line. is prepared similar to b, a 25 μs ESR pulse of varying frequency is applied rotating when = fESR, and , when = fESR; is again mapped back . We find = (0.43 ± 0.02) × 10−3

For simplicity we henceforth assume δEZ > 0, so that we adiabatically prepare for large ε. Following the pulse sequence illustrated in Fig. 3c, coherent-exchange-driven oscillations can then be observed between and by rapidly plunging the prepared state back towards the (1, 1)-(0, 2) anti-crossing where J(ε) is no longer negligible. Variable dwell time τD results in coherent exchange oscillations, and the reversal of the rapid plunge leaves the state in a superposition of and . The semi-adiabatic ramp back to (0, 2) maps the final state to the singlet, while is mapped to a blockaded state via the ∣T0⟩ triplet14,19. The resulting data is shown in Fig. 3d, e.

Individual qubit addressability via electron spin resonance

We note that previous experiments performed at = 1.4 T on another SiMOS device exploited the g-factor difference between two QDs in the low-J(ε) region to perform a two-qubit controlled-phase operation8. Utilizing the high-J(ε) region as above, the operation can extend the two-qubit toolbox to include a SWAP gate, with a potentially shorter operation time, in this case with τSWAP~0.25 μs, limited by exchange pulse rise times.

Having characterized the system in the singlet–triplet basis, we now investigate the compatibility of spin blockade readout with individual QD (i.e., single spin) addressability via electron spin resonance (ESR)2, a combination desirable for scalable spin qubit architectures incorporating error correction15,16. Using the pulse sequence illustrated in Fig. 3f, we again adiabatically prepare the large-ε ground state , as discussed above. We now apply an ac magnetic field to perform ESR with pulse duration 25 μs, supplied by the on-chip microwave transmission line49 (Fig. 1a), to drive transitions that correspond to and at large detuning, when exchange is small (see Fig. 3a). Any excitation from the ground state will now map to the blockaded triplet state population. Figure 3g shows the measured ESR spectrum as a function of detuning ε. The higher frequency fESR2 branch corresponds to a coherent rotation of the electron spin in QD2, while the lower frequency fESR1 rotates the QD1 spin. At large detuning fESR1~4.2 GHz, consistent with the applied magnetic field = 150 mT for this experiment. As ε decreases (and J(ε) increases), the ground state is better described as , so the transitions become and and exchange now competes with ESR, resulting in a lower visibility. For large detuning, the reduction in visibility can be produced from a number of sources. Here, the tuning of the semi-adiabatic ramp rate is critical in this region to prevent excitation (discussed further in Supplementary Note 7). The reduction in visibility seen here is due to an increase in preparation and readout error. This could be mitigated in future experiments though pulse optimisation of the semi-adiabatic ramps.

Exchange coupling between qubits

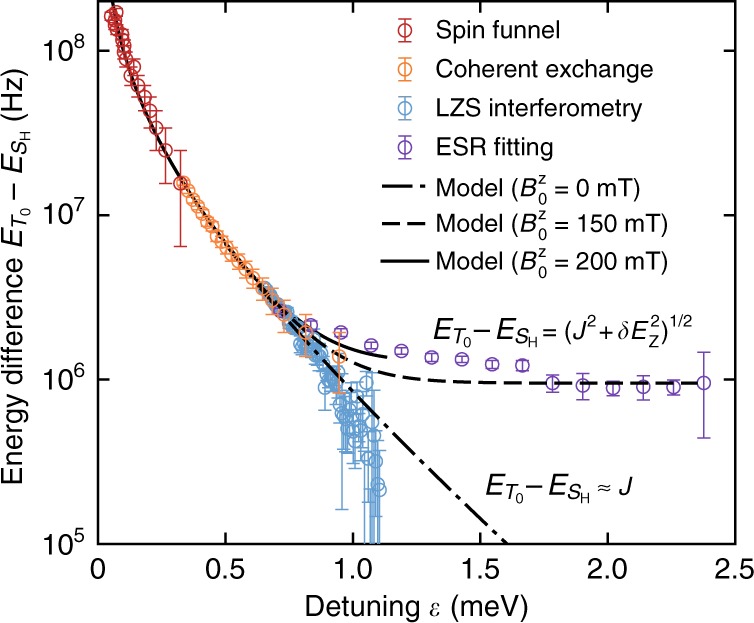

Each of the experiments described above probes the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) for different ranges of detuning. Figure 4 collates the results of all experiments and plots the energy splitting between the hybridised singlet and unpolarised triplet across all detuning values. Close to the (0, 2)-(1, 1) anti-crossing, for low ε, the splitting is dominated by exchange coupling J, while for large ε, δEZ dominates. As expected, the energy differences obtained from the LZS interferometry (for ) diverge from those obtained via ESR (where = 150 mT), since when there remains only a small residual δEZ due to combined Meissner screening and weak Overhauser fields. Figure 4 also shows a fit to the data employing the Hamiltonian of Eq. (1) as documented elsewhere. A constant tc fits poorly; instead a model for a dependence of the tunnel coupling on ε is employed (see Supplementary Note 6). At the anti-crossing (ε = 0), the curve fit to this model indicates tc(ε = 0) = 1.864 ± 0.033 GHz and δg = (0.43 ± 0.02) × 10−3. We note that this tunnel coupling is comparable to that observed for a separate two-qubit device8 for which tc(ε) = MHz.

Fig. 4.

Effective exchange with detuning. Exchange energy splitting as a function of detuning ε, as extracted from the spin-funnel (Similar to Fig. 2d, see Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Fig. 4), Landau–Zener–Stueckelberg interferometry (Fig. 2g), coherent exchange oscillations (Fig. 3d) and ESR funnel data (Fig. 3f). Each include 95% confidence intervals based on data fits uncertainties or measurement resolution. The solid/dashed lines represent fits to the data based on the model Hamiltonian in Eq. (1), for which we find tc(ε = 0) = 1.86 ± 0.03 GHz

Discussion

By analyzing the error processes present in these experiments, we can identify where improvements will be required before these mechanisms can be integrated into a parity readout tool useful for future multi-qubit architectures. We can discriminate between the effect of various error processes by comparing blockade probability observations under different operating regimes in the exchange oscillation data of Fig. 3e. The histograms shown in Fig. 1g each reveal state preparation and measurement (SPAM)-related errors, leading to a visibility maximum of 98% (orange data) and an error of 0.8% associated with preparation and the transfer process to a latched readout position (red data). Additional to these SPAM errors are the transfer and mapping error processes present when converting states semi-adiabatically from the (0, 2)→(1, 1) or (1, 1)→(0, 2) charge transitions respectively. The combined error from SPAM, state transfer and mapping can be observed from the background visibility at a detuning where exchange is minimal. Here, the prepared state is ideally transferred to and from the (1, 1) region without loss, resulting in zero triplet probability. In contrast, the average blockaded return probability from Fig. 3e (and therefore the combined transfer and mapping errors) saturates to around 30%. From the decay in the oscillations of Fig. 3e as a function of operation time τD, we find a maximum control fidelity of Fπ = 0.95 ± 0.04 at ε = 0.6 meV. We find that the decay time is proportional to the Rabi period, suggesting that exchange noise limits our control fidelity. Further, comparisons with the 61% visibility of the first fringe in Fig. 3e suggests that diabaticity errors due to each fast plunge to/from the exchange position are also present. With respect to our system’s utility for providing a parity readout tool, the main error source in the present work appears to occur during adiabatic transfer into and out of the (1, 1) region. Time-dependent simulations (Supplementary Note 7 and Supplementary Table 1) of the model Hamiltonian Eq. (1) show that this error can be well explained by diabaticity with respect to tc(ε) near the anti-crossing. We expect that this error can be significantly reduced by optimizing the shape of the ramp as a function of detuning, to remain diabatic with respect to Δ near the crossing, while staying adiabatic elsewhere. Of relevance to the fidelity of exchange-based two-qubit gates, we note that charge and voltage noise will couple via detuning ε to produce noise in exchange. Our simulations (Supplementary Note 7 and Supplementary Fig. 5) indicate that the level of charge noise expected7,20 in our system results in a oscillation decay consistent with our measurements. The effect of charge noise could be minimized by symmetric biasing50, with the use of an additional exchange gate.

To conclude, we have for the first time in a silicon device experimentally combined single-spin control using electron spin resonance, with high-fidelity single-shot readout in the singlet–triplet basis. By characterising the relevant energy scales Δ, δEZ and tc(ε) of the two-spin Hamiltonian, we found that we could coherently manipulate both the S/T− and S/T0 states, the latter of which provides potential for a fast two-qubit SWAP gate at high exchange. The integration of low-frequency ESR of individual spins with singlet-triplet based initialisation and readout holds promise for qubit architectures operating at significantly lower magnetic fields and higher temperatures. Future experiments will focus on improvements in operational fidelities, as well as further characterisation of low-frequency ESR operation. The presented initialisation and readout of singlet–triplet states attests to the compatibility of the SiMOS quantum dot platform with parity readout based on spin-blockade, key for the realisation of a future large-scale silicon-based quantum processor15,16.

Methods

Device fabrication

The device is fabricated on an epitaxially grown, isotopically purified 28Si epilayer with residual 29Si concentration of 800 ppm44. Following the multi-level gate-stack silicon MOS technology26, four layers of Al-gates are fabricated on top of a SiO2 dielectric with a thickness of 5.9 nm. Gate layers have a thickness of 25, 60, 80, and 80 nm, with three layers used to form the device and the fourth layer attributed to the ESR transmission line. Overlapping layers are separated by thermally grown aluminum oxide.

Experimental set-up

The measurements were conducted in a dilution refrigerator with base temperature Tbath = 30 mK. DC voltages were applied using battery-powered voltage sources and are combined with voltage pulses using an arbitrary waveform generator (LeCroy ArbStudio 1104) through resistive voltage divider network. Filters were included for DC, slow-pulse and fast-pulse lines (10 Hz to 80 MHz). Microwave pulses were delivered by an Agilent E8257D analogue signal generator, passing signal through a 10 dBm attenuator at the 4 K plate and 3 dBm attenuator at the mixing chamber plate.

All the measured qubit statistics are based on counting the blockade signal in the latched region as described in the main text. The operating region within the experiments involves a system of two tunnel coupled quantum dots with a total of two electrons shared between them. The latched readout procedure involves conditional loading of a third electron from tunnel-coupled reservoir onto one of these dots. Each data point represents the average of between 100 and 1200 single shot blockade events, including experiment trace repetition. Stability maps generated from three level pulsing could be produced with less averaging, with figure data being the average of 40 shots per point.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Mark Gyure for helpful discussions. We acknowledge support from the Australian Research Council (CE11E0001017 and CE170100039), the US Army Research Office (W911NF-13-1-0024 and W911NF-17-1-0198) and the NSW Node of the Australian National Fabrication Facility. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Army Research Office or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein. M.V. and B.H. acknowledges support from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) through a Rubicon Grant. K.M.I. acknowledges support from a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research by MEXT, NanoQuine, FIRST, and the JSPS Core-to-Core Program.

Author contributions

M.A.F. and B.H. performed experiments. M.V. designed the device, fabricated by K.W.C. and F.E.H. with A.S.D’s supervision. K.M.I. prepared and supplied the 28Si epilayer. W.H., T.T., C.H.Y., and A.L. contributed to the preparation of experiments. M.A.F., B.H., and A.S.D. designed the experiments, with T.D.L., W.H., D.C., K.W.C., T.T., C.H.Y., A.L., A.M. contributing to results discussion and interpretation. M.A.F., B.H., and A.S.D. wrote the manuscript with input from all co-authors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

M. A. Fogarty, Email: m.fogarty@ucl.ac.uk

B. Hensen, Email: b.hensen@unsw.edu.au

A. S. Dzurak, Email: a.dzurak@unsw.edu.au

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-06039-x.

References

- 1.Pla JJ, et al. A single-atom electron spin qubit in silicon. Nature. 2012;488:541–545. doi: 10.1038/nature11449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veldhorst M, et al. An addressable quantum dot qubit with fault-tolerant control-fidelity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014;9:981–985. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawakami E, et al. Gate fidelity and coherence of an electron spin in an Si/SiGe quantum dot with micromagnet. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:11738–11743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603251113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeda K, et al. A fault-tolerant addressable spin qubit in a natural silicon quantum dot. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1600694. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorgrimsson B, et al. Extending the coherence of a quantum dot hybrid qubit. npj Quantum Inf. 2017;3:32. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoneda J, et al. A quantum-dot spin qubit with coherence limited by charge noise and fidelity higher than 99.9% Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018;13:102–106. doi: 10.1038/s41565-017-0014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muhonen JT, et al. Storing quantum information for 30 seconds in a nanoelectronic device. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014;9:986–991. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veldhorst M, et al. A two-qubit logic gate in silicon. Nature. 2015;526:410–414. doi: 10.1038/nature15263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson TF, et al. A programmable two-qubit quantum processor in silicon. Nature. 2018;555:633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature25766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zajac DM, et al. Quantum CNOT Gate for Spins in Silicon. Science. 2018;359:439–442. doi: 10.1126/science.aao5965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elzerman JM, et al. Single-shot read-out of an individual electron spin in a quantum dot. Nature. 2004;430:431–435. doi: 10.1038/nature02693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colless JI, et al. Dispersive readout of a few-electron double quantum dot with fast rf gate sensors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013;110:046805. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.046805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ono K, Austing DG, Tokura Y, Tarucha S. Current rectification by Pauli exclusion in a weakly coupled double quantum dot system. Science. 2002;297:1313–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.1070958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petta JR, et al. Coherent manipulation of coupled electron spins in semiconductor quantum dots. Science. 2005;309:2180–2184. doi: 10.1126/science.1116955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.C. Jones, et al. A logical qubit in a linear array of semiconductor quantum dots. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021058 (2018).

- 16.Veldhorst M, Eenink HGJ, Yang CH, Dzurak AS. Silicon CMOS architecture for a spin-based quantum computer. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1766. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01905-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandersypen LMK, et al. Interfacing spin qubits in quantum dots and donors - hot, dense and coherent. npj Quantum Inf. 2017;3:34. doi: 10.1038/s41534-017-0038-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petta JR, Lu H, Gossard AC. A coherent beam splitter for electronic spin states. Science. 2010;327:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.1183628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maune BM, et al. Coherent singlet-triplet oscillations in a silicon-based double quantum dot. Nature. 2012;481:344–347. doi: 10.1038/nature10707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eng K, et al. Isotopically enhanced triple-quantum-dot qubit. Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1500214. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu X, et al. Two-axis control of a singlet-triplet qubit with an integrated micromagnet. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:11938–11942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412230111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.P. Harvey-Collard, et al. High-fidelity single-shot readout for a spin qubit via an enhanced latching mechanism. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021046 (2018).

- 23.R. M. Jock, et al. A silicon metal-oxide-semiconductor electron spin-orbit qubit. Nat. Commun. 9, 1768 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Nakajima T, et al. Robust single-shot measurement of spin correlations using a metastable charge state in a quantum dot array. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017;119:017701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.017701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broome MA, et al. High-fidelity single-shot singlet-triplet readout of precision-placed donors in silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017;119:046802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.046802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angus SJ, Ferguson AJ, Dzurak AS, Clark RG. Gate-defined quantum dots in intrinsic silicon. Nano. Lett. 2007;7:2051–2055. doi: 10.1021/nl070949k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zwanenburg FA, et al. Silicon quantum electronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2013;85:961–1019. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.85.961. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson AC, et al. Triplet–singlet spin relaxation via nuclei in a double quantum dot. Nature. 2005;435:925–928. doi: 10.1038/nature03815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu HW, et al. Pauli-spin-blockade transport through a silicon double quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B. 2008;77:073310. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.77.073310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaji N, et al. Spin blockade and lifetime-enhanced transport in a few-electron Si/SiGe double quantum dot. Nat. Phys. 2008;4:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nphys988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai NS, et al. Pauli spin blockade in a highly tunable silicon double quantum dot. Sci. Rep. 2011;1:110. doi: 10.1038/srep00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zajac DM, Hazard TM, Mi X, Nielsen E, Petta JR. Scalable gate architecture for a one-dimensional array of semiconductor spin qubits. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2016;6:054013. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.6.054013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang CH, et al. Charge state hysteresis in semiconductor quantum dots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014;105:183505. doi: 10.1063/1.4901218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Studenikin SA, et al. Enhanced charge detection of spin qubit readout via an intermediate state. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012;101:233101. doi: 10.1063/1.4749281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang CH, et al. Orbital and valley state spectra of a few-electron silicon quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;86:115319. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.86.115319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Culcer D, Cywiński L, Li Q, Hu X, Das Sarma S. Realizing singlet-triplet qubits in multivalley Si quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B. 2009;80:205302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.80.205302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Culcer D, Cywiński L, Li Q, Hu X, Das Sarma S. Quantum dot spin qubits in silicon: Multivalley physics. Phys. Rev. B. 2010;82:155312. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.82.155312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Veldhorst M, et al. Spin-orbit coupling and operation of multivalley spin qubits. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2015;92:7–11. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.92.201401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.R. Ferdous, et al. Interface induced spin-orbit interaction in silicon quantum dots and prospects of scalability. Phys. Rev. B97, 241401 (2018).

- 40.Underwood, D. Coherent oscillations in silicon double quantum dots due to Meissner-screened magnetic field gradients. Bull. Am. Phys. Soc.62, abstract id. F52.008 https://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2017APS..MARF52008U (2017).

- 41.Taylor JM, et al. Relaxation, dephasing, and quantum control of electron spins in double quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B. 2007;76:035315. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.76.035315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loss D, DiVincenzo DP. Quantum computation with quantum dots. Phys. Rev. A. 1998;57:120–126. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.57.120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shevchenko SN, Ashhab S, Nori F. Landau Zener Stückelberg interferometry. Phys. Rep. 2010;492:1–30. doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2010.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Itoh KM, Watanabe H. Isotope engineering of silicon and diamond for quantum computing and sensing applications. Mater. Res. Soc. 2014;4:143–157. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nichol, J. M. et al. Quenching of dynamic nuclear polarization by spin-orbit coupling in GaAs quantum dots. Nat. Commun. 6, 7682 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Braakman FR, Danon J, Schreiber LR, Wegscheider W, Vandersypen LMK. Dynamics of spin-ip photonassisted tunneling. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2014;89:075417. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.89.075417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reilly DJ, et al. Measurement of temporal correlations of the overhauser field in a double quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;101:236803. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.236803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schreiber LR, et al. Coupling artificial molecular spin states by photon-assisted tunnelling. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:556–558. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dehollain JP, et al. Nanoscale broadband transmission lines for spin qubit control. Nanotechnology. 2012;24:015202. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/24/1/015202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reed MD, et al. Reduced sensitivity to charge noise in semiconductor spin qubits via symmetric operation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016;116:110402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.110402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.