ABSTRACT

During severe septic shock and/or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients present with a limited cardio-ventilatory reserve (low cardiac output and blood pressure, low mixed venous saturation, increased lactate, low PaO2/FiO2 ratio, etc.), especially when elderly patients or co-morbidities are considered. Rescue therapies (low dose steroids, adding vasopressin to noradrenaline, proning, almitrine, NO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, etc.) are complex. Fever, above 38.5–39.5°C, increases both the ventilatory (high respiratory drive: large tidal volume, high respiratory rate) and the metabolic (increased O2 consumption) demands, further limiting the cardio-ventilatory reserve. Some data (case reports, uncontrolled trial, small randomized prospective trials) suggest that control of elevated body temperature (“fever control”) leading to normothermia (35.5–37°C) will lower both the ventilatory and metabolic demands: fever control should simplify critical care management when limited cardio-ventilatory reserve is at stake. Usually fever control is generated by a combination of general anesthesia (“analgo-sedation”, light total intravenous anesthesia), antipyretics and cooling. However general anesthesia suppresses spontaneous ventilation, making the management more complex. At variance, alpha-2 agonists (clonidine, dexmedetomidine) administered immediately following tracheal intubation and controlled mandatory ventilation, with prior optimization of volemia and atrio-ventricular conduction, will reduce metabolic demand and facilitate normothermia. Furthermore, after a rigorous control of systemic acidosis, alpha-2 agonists will allow for accelerated emergence without delirium, early spontaneous ventilation, improved cardiac output and micro-circulation, lowered vasopressor requirements and inflammation. Rigorous prospective randomized trials are needed in subsets of patients with a high fever and spiraling toward refractory septic shock and/or presenting with severe ARDS.

KEYWORDS: septic shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, spontaneous breathing, high PEEP, fever control, hyperthermia, hypothermia, sympathetic system, clonidine, dexmedetomidine

Abbreviations and glossary

- ALI

acute lung injury (200<P/F<300)

- APRV-SV

airway pressure release ventilation-spontaneous ventilation

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CCU

critical care unit

- CMV

controlled mandatory ventilation

- ECMO

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- EIT

electrical impedance tomography

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume measured over 1s (Tiffeneau-Pinelli index)

- FRC

functional residual capacity

- HR

heart rate

- 5HT

serotonin

- 5HT1A

subtype of serotonin receptor

- IL6, IL10

pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide evoking “sterile inflammation”

- NA

noradrenaline

- NO

nitric oxide

- PaO2/FiO2 = P/F

index of oxygenation

- Paracetamol

acetaminophen

- Pendel-luft

lung dys-coordination

- PEEP

positive end-expiratory pressure

- PCT

procalcitonin

- P-SILI

patient-self inflicted lung injury (ventilation-induced lung injury as opposed to ventilator-induced self injury)

- RASS

Richmond agitation sedation scale

- RR

respiratory rate

- RRT

renal replacement therapy

- TIVA

total intravenous anesthesia

- VA/Q

ventilation/perfusion ratio

- VO2

O2 consumption

- Vt

tidal volume

I. Introduction

Manipulation of temperature in the critical care unit (CCU) has been proposed early (“artificial hibernation” [1]. However, as early as 1954, manipulation of temperature was to be considered in only ≈10% of the patients, those presenting with the most severe combat injuries [2]. This overview focuses on these very sick patients presenting with an elevated body temperature. Indeed, induced-normothermia (control of elevated body temperature, “fever control” [3]) is not straightforward. Given the focus on severe cardioventilatory distress in the setting of septic shock and severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and recent reviews [4–9], pros and cons for respecting elevated body temperature are briefly discussed.

A). Restriction of the topic

The present hypothesis restricts itself to fever control and will not consider spontaneous hypothermia or induced-hypothermia. Nevertheless, the literature on spontaneous and induced-hypothermia has to be overviewed.

The US infectious diseases society defines hyperthermia as temperature ≥38.3°C [7]. Hypothermia is defined <36°C [7], <35.5°C) [10] or <35°C [11]. Mild hypothermia (≈34–32°C), in the post-cardiac arrest setting, avoids any after-drop and ventricular arrhythmias. In the setting of traumatic brain injury, temperature is sometimes lowered to ≈33–35.5°C [12]. Conversely, in the cardiac arrest setting, the upper limit ≤37.6°C is considered [7]. Only fever control or evoked-normothermia will be considered in the following discussion, defined as 35.5–37.5°C. These are the lowest and highest temperatures observed during the day-night cycle in any healthy non-exercising or sleeping human. This range allows one to skip the coagulation and immunological pathologies [11] associated with deeper hypothermia (≤35°C).

In hospitalized patients, ≈75% of the elevated body temperature is linked to systemic inflammation in the setting of sepsis. Malignancy, tissue ischemia, drug reactions account for the remainder. Neurogenic and endocrinology-evoked (thyroid, adrenal medulla) fevers are uncommon [8].

B). Beneficial effects of hyperthermia

A negative relationship exists between body temperature and mortality (n = 10 834 patients) [13]: hyperthermic (>38°C) and hypothermic (<36°C) patients present a 22 and 47% mortality respectively [13]. High temperature>39.0°C was associated with reduced mortality in septic patients, outside septic shock. Moderate fever (37.5–39.4°C) associated with sepsis may be associated with an increased survival (quoted from [8]. Similarly, moderate fever (37.5–38.4°C) is beneficial in septic patients [7]. A temperature>39.5°C is detrimental in non-septic patients: high peak temperature were associated with increased mortality in non-infectious fever [14].

Presumably, elevated body temperature decreases the bacterial/viral load [7]. Increased temperature may enhance the ability of the immune system to eliminate invading micro-organisms [15]. As elevated body temperature comes at a metabolic cost, a teleological conclusion is that its persistence across a broad range of species provides circumstantial evidence that the response has evolutionary advantage: the immune system would have evolved to function optimally when elevated body temperature does not reach too high levels [14]. However arguments based on evolution do not necessarily apply to humans under CCU conditions, and supported beyond the limits of physiological homeostasis [14]: in the presence of antibiotics and other therapeutics, the harms of the febrile response may outweigh its benefits [16]. Therefore, elevated body temperature may either be a protective response (i.e. a mechanism that the physician ought not to interfere with) or a marker of severity or a risk factor implying active therapy i.e. fever control [6].

C). Effects of hypothermia on the outcome of sepsis

In the setting of septic shock, thirty three per cent of the patients presenting for inclusion in a trial of control of elevated body temperature were excluded for absence of fever [3]. Some ten per cent of septic patients present hypothermia and increased mortality (quoted from [5]). Presumably, the spontaneous absence of elevated body temperature characterizes the most severely ill patients with shock and/or without metabolic resource to produce heat [3]. Hypothermia (<35.5°C; 9% of the patients) is associated with a higher incidence of confusion, higher lactate (not significant: ns), higher incidence of shock (94% of hypothermic patients vs. 61% of febrile patients), low filling pressure, higher mortality (mortality in hypothermia group: 62% vs. febrile group: 26%) [10]. Increased mortality is observed in elderly patients presenting with community-acquired pneumonia and absence of elevated body temperature as opposed to patients developing fever (quoted from [8]).

Does spontaneous or evoked-hypothermia worsen the outcome [15]? In rats developing lipopolysaccharide (“sterile inflammation” evoked by LPS) or E Coli-induced shock, the outcome is better in the hypothermic group as opposed to the fever group, if hypothermia develops in a colder environment for both groups [15]: therefore spontaneous hypothermia may be a protective response in a subset of septic shock patients. This hypothesis [17,18] posits that elevated body temperature is the first phase of sepsis followed by reduced body temperature observed when the animal is getting sicker, the only possibility in the wild: mortality may be a consequence of a more severe sepsis. The severity of sepsis and the occurrence of spontaneous hypothermia does not necessarily imply that spontaneous hypothermia occurs immediately before death, septic shock, ARDS or use of antipyretics [19]. In addition, the situation of a very sick animal in the wild is not necessarily identical with the situation of a very sick patient under maximal support in the CCU [14]. Therefore, the patient presenting with septic shock and spontaneous hypothermia does not necessarily need active rewarming, irrespective of his clinical situation. Moreover, multiple organ failure is postulated to be a temporary adaptive, protective, mechanism in the setting of septic shock [20]. As in the setting of myocardial stunning, the hypothesis is that the metabolic requirements are reduced temporarily: reduced mitochondrial activity may enhance cell survival. Therefore, the thermometabolic adaptation hypothesis holds that spontaneous hypothermia should be allowed to run, within limits, if lowered O2 consumption (VO2) is matched by a lowered O2 delivery [21]. Outcome should be assessed prospectively [21] in well defined subsets [22] (Figure 1; figure 2 in reference [7]: a control hypothermic septic shock group where spontaneous hypothermia is let to run within limits as opposed to a treated hypothermic septic shock group where evoked-normothermia is re-established through active rewarming [21].

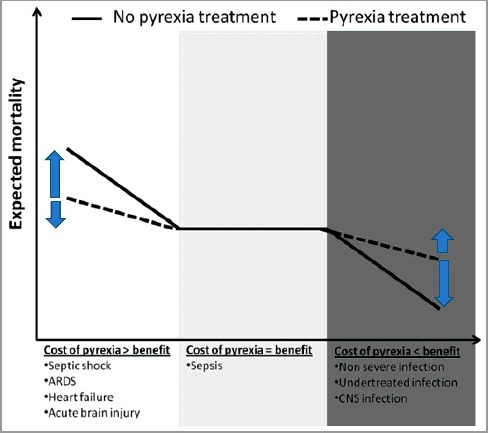

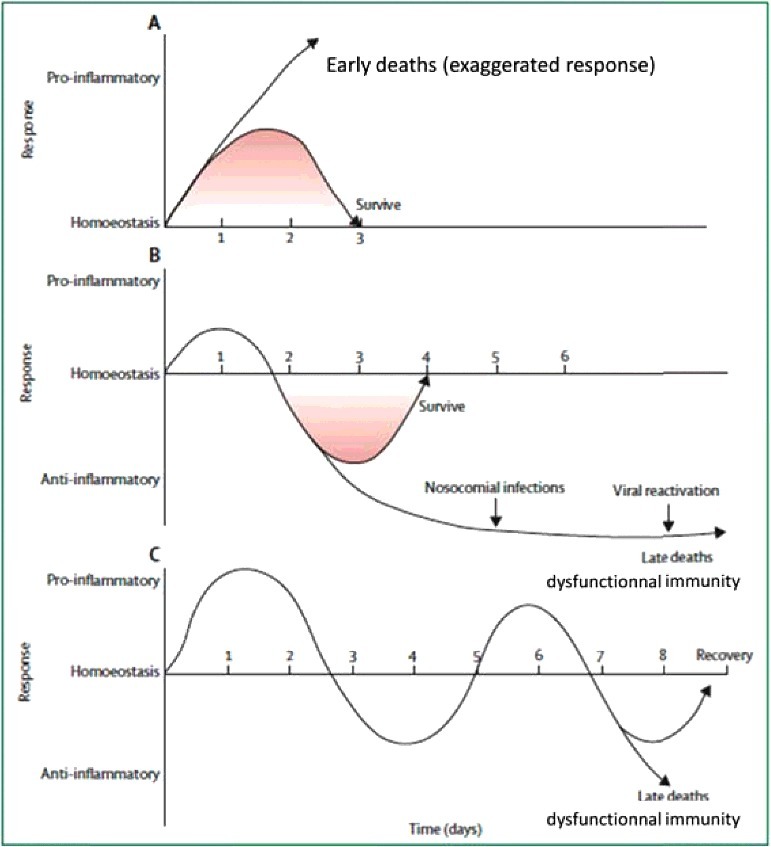

Figure 1.

A niche for normothermia in the critical care setting? Suggested impact of fever control on outcome according to clinical context: obviously fever control is to be restricted to niches (cost of pyrexia>benefit : left part of schema) in which the benefit is superior to the cost for the patient : severe septic shock, severe ARDS, circulatory insufficiency. Abbreviations: ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; CNS: central nervous system. Reused from Doyle, Crit Care, 2016, 20: 303 [7] under Creative Commons attribution license 4.0.

The peripheral shut-down observed in the hypothermic septic shock patients needs discussion: if therapy achieves only adequate cardiac output and systemic pressure, improved ventilation, improved general homeostasis using renal replacement therapy (RRT), in addition to anti-infectious strategy, adequate transfer of heat from core to periphery and vice-versa will occur, at best, very slowly: then, the metabolic issue is the limiting factor. This brings up restoring micro-circulation [23,24] immediately after restoring cardiac output. Within the mechanisms of heat production (shivering and non-shivering thermogenesis) and dissipation, only shivering, vasoconstriction and vasodilation may be considered in the CCU. After normalization of cardio-ventilatory distress, vasodilation will enhance heat dissipation from core to periphery in the setting of elevated body temperature and septic shock: this will lower body temperature. Conversely, reopening of unperfused capillaries (i.e. vasodilation) will presumably allow the transfer of an external, therapeutic, heat source to the core in the setting of spontaneous hypothermia and septic shock, allowing faster rewarming.

D). Evoking fever control?

Shivering occurs when core temperature is ≈1.5°C below the activation threshold1. of cold defense effectors (quoted from [7]). In the septic setting (baseline temperature ≈38.7°C), external cooling evokes shivering: VO2 increased (+57%) [22]. «Counter-warming» with an air circulating blanket suppresses shivering evoked by hypothermia in the setting of brain injury/cardiac arrest hypothermia (VO2 : −16%) [12]. In the setting of subarachnoid hemorrhage, traumatic brain injury and strict normothermia, water-circulating blankets (−1.12°C.h-1) appear superior to air-circulating blanket (−0.15°C.h-1) or conventional cooling (iced saline combined to surface cooling : 0.06°C.h-1) [25].

Antipyretics (non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, paracetamol = acetaminophen) are administered to the most severe patients unable to tolerate elevated body temperature [5]. In septic patients, ibuprofen lowered temperature (38°C to 36.7°C), ventilation (≈−2 L.min-1), heart rate (HR≈115 to 100 bpmin) and lactate (−17%) [26]. Antipyretics increased 28-day mortality in the septic group [8].

This overview focuses on control of elevated body temperature in the setting of limited cardioventilatory reserve (elderly patients, co-morbidities): septic shock and severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) presenting with elevated body temperature. A rationale for using alpha-2 adrenergic agonists (“alpha-2 agonists”) to achieve fever control while controlling for shivering is delineated.

II. Fever control in the setting of septic shock

For didactic purposes, septic shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome will be discussed respectively as pure circulatory vs. pure ventilatory disorders, with evident oversimplification.

A). Present knowledge

In healthy volunteers, injection of endotoxin to healthy volunteers increase both energy expenditure and temperature [27]. Furthermore, administration of noradrenaline increases VO2 by +15% [28]. Thus, therapy adds to injury, reinforcing the need of fever control when limited cardio-ventilatory reserve is present.

By contrast, cooling febrile CCU patients reduces VO2 by ≈8–10% per °C [14]. In paralyzed sedated patients under controlled mechanical ventilation, surface cooling (39.4±0.8 °C to 37.0±0.5) decreases VO2 (359±65 to 295±57 mL.min-1; aggregated data: −18%) [29]. In one mild shivering patient, lowering temperature to 36.2°C reduces VO2 by −39%. VCO2 is lowered (303±43 to 243±37 mL.min-1:−20%). This is relevant when low driving pressure [30] and permissive hypercapnia [31] are considered in the setting of ARDS (“protective” ventilation). Cardiac output, O2 extraction ratio2. and HR decrease (respectively: 8.4±3.2 L.min-1 to 6.5±1.8 L.min-1, 28±7 to 23±5% and 119±21 to 102±14 bpmin). Mixed venous SO2 increases from 68±8 to 71±6% (ns). Therefore, mechanical ventilation, paralysis, and cooling (from 40 to 36° C) could reduce V02 in febrile, critically ill patients by as much as 190 mL/min, lowering metabolic demand by 47%: the manipulation of VO2 is a salvage therapy in severe shock or hypoxemic respiratory failure, e.g. for febrile, mechanically ventilated patients who do not respond to sedation and antipyretics [29]. In the setting of synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (n = 8) or pressure support (n = 10), external cooling lowered minute ventilation (39.1 to 37°C: 14.7±1 to 13.1 ±0.9 L.min-1: −11%) and decreased energy expenditure (−12%; sedation: morphine+midazolam to Ramsay 3–4) [32]. In this trial [32], only subsets of « septic episode » or severe hypoxia were studied [32].

1). Outcome

After sedation, intubation, mechanical ventilation, patients presenting with early septic shock were randomized to external cooling within 2 h after enrollment (n = 101, 36.5–37.5°C for 48 h) vs. no external cooling (n = 99) [3]. Paracetamol was seldom used (n = 2 patients*2) [33]: only external cooling was used, avoiding almost entirely a possible confounding factor (pharmacology: heat production reduction as opposed to external cooling only). The sample is biased as, respectively, 70 and ≈50% of the included patients presented an infection related to pneumonia and moderate ARDS, irrespective of group assignment to fever control vs. no external cooling [3]. Nevertheless, the strength of this trial [3] is its high degree of homogeneity both with respect to recruitment of septic shock patients with elevated body temperature and therapeutics. In this trial [3], ≈33% of the patients were excluded for absence of elevated body temperature in the setting of septic shock [3].

Cooling was short (48 h) to allow one assessing the evolution of the initial infection and early detection of nosocomial infection [3]. Fourteen days mortality was lowered (34 vs. 19%: −16%) [3]. Evoked normothermia is supposed not to increase infection [3,11]. Nevertheless, a) incidence of acquired infection by day 14 was higher in the normothermia group. b) a late mortality, upon hospital discharge, was observed in the fever control group [3]: 24% vs. 14%. The immuno-suppressive response develops after the initial phase of severe sepsis, depending on the severity and duration of the septic phase. Therefore, taken together, fever control may present opposite effects which may or may not cancel each other: decreased risk of CCU-acquired infection by accelerating the rate of recovery of the initial septic shock vs. increased secondary immuno-depression [5]. A post-hoc analysis [34] showed that the reduced mortality was related to lowered temperature <38.4°C but not to lowered HR. Reduced vasopressor requirement was not associated with lowered HR [34].

This favorable outcome observed in a subset of septic shock patients presenting with elevated body temperature [3] contrasts with worsened outcome when all critical care patients with elevated body temperature are randomized to paracetamol and external cooling (aggressive group) vs. no treatment until temperature reached >40°C (permissive group). Interim analysis showed higher mortality in the aggressive group (44 vs. 38 patients and 7 deaths vs. 1 respectively; p = 0.06) [35]. Thus, elevated temperature may be more important for the localized tissue response than for the systemic or whole-body immune responses (Atkins quoted from [18]. Therefore, the conventional wisdom of beneficial effect of hyperthermia may not only be broken down to severe vs. non-severe hyperthermia but also to local vs. systemic phenomenons. A niche [3] approach, favoring external cooling in the setting of elevated temperature, is to be favored if fever control is to improve CCU outcome. However, suppression of heat production is another option to achieve fever control, as delineated earlier [36].

2). Vasopressor requirement

A decrease in vasopressor requirement was significant by 12 h (−50%) but not by the 48 h interval, more pronounced in those patients having the highest baseline vasopressor doses [3]. The authors delineate a limitation: the fever control group presented slightly lower noradrenaline requirement at inclusion (0.50 μg.kg-1.min-1 vs. 0.65). Early shock reversal was more common with external cooling, which prevented early death. This reduction in vasopressor requirement [3] during normothermia has been previously observed [37]:

-

a)

a pressor effect was observed in 80% of the patients [38]. An early report (1961) observed a 50% survival in the setting of refractory septic shock (« irreversible septic shock ») treated with 1961's state-of-the-art combined to hypothermia (32°C; 1–30 days, usually 3 days; no control group). A recovery from confusion/coma evoked by sepsis was observed in 94% of the patients [38].

-

b)

moribund patients with sepsis+ARDS presented a reduction in vasopressor requirements in the setting of hypothermia (32–35°C) [39].

The vasopressor sparing effect of lowered temperature is observed following corticosteroids administration or continuous hemofiltration. This vasopressor sparing effect linked to hypothermia is presumably opposed to the mechanism linked to hyperthermia: capillary dilatation, vascular stasis, and extravasation in the interstitium [8].

To sum up, fever control should be considered in septic shock with increasing dose of vasopressors [5]: the sicker patients are the ones to benefit the most from artificial hibernation [2], external cooling [3,35], and alpha-2 agonists in the setting of septic shock [40]. Nevertheless, although septic patients with high temperature require fever control to reduce VO2 and catabolism, this reduction in temperature is not yet proven as harmful or not [37]. As the evidence [3] is limited to one large trial, independent validation is required.

B). Alpha-2 agonists to modify the management of septic shock?

1). Working hypothesis

In our hands, in the setting of acute cardio-ventilatory distress and septic shock, obtaining fever control in febrile patients combines within an “analytical” bundle, i.e. state-of-the-art treatment combined with alpha-2 agonists: a) paracetamol, external cooling. b) normalization of volemia up to an absence of response to rigorous [41] passive leg raising and minimized changes in the diameter of the vena cava evoked by ventilation. c) administration of a vasopressor to rise the systemic pressure according to systemic perfusion (urine output, micro-circulation, etc.) and co-morbidities (hypertension, coronary disease, etc.). Vasopressor is thought to be administered early when diastolic pressure is low [42]. High systemic perfusion pressure may be needed early in the sicker patients [23]. d) after normalization of volemia, auriculo-ventricular conduction and blood pressure, and immediately following tracheal intubation, an alpha-2 agonist is administered (infusion of clonidine 1 μg.kg-1.h-1 or dexmedetomidine 0.75 μg.kg-1.h-13. to −3<RASS<−1)4..

Several questions remain: first, should the hypothermic patients presenting with septic shock be actively warmed up to 35.5°C [21]? second, is it beneficial to actively rewarm the hypothermic septic shock patients up to 35.5°C, under alpha-2 agonists, to improve micro-circulation? Presumably, following alpha-2 agonists, the adequacy of the cardiac output (superior vena cava S02>70–75%, CO2 gap <5–6 mm Hg, adequate trend in lactate toward <2mM) combines to adequate micro-circulation. This will allow transferring active heating from periphery to the core. c) conversely, may antipyretics be used alone, without alpha-2 agonists, to evoke fever control? Alpha-2 agonists will provide cooperative sedation without depression of the respiratory generator [43] and without emergence delirium [44–46]. In addition, alpha-2 agonists normalize a dysfunctional vasomotor and skin sympathetic nervous hyperactivity: this will presumably improve micro-circulation and favor heat transfer from core to periphery, evoking fever control.

2). Pharmacology

Application of serotonin (5HT) in the hypothalamus activates heat loss mechanisms whereas application of noradrenaline increases heat conservation and production (quoted from [47]): serotonin and noradrenaline are considered as thermogenic vs. thermolytic, respectively [10], depending on the considered agonist or antagonist. The alpha-2 adrenoceptors may be located on a cholinergic-serotoninergic pathway [48]. The activation threshold of cold defense effectors is lowered by alpha-2 agonists [49]. The hypothermic effect of clonidine is increased following lesioning the ventral noradrenergic bundle which projects to the hypothalamus [50]. Clonidine produces hypothermia either by reducing heat production and/or by enhancing heat loss (cutaneous vasodilation) through hypothalamic alpha-2 adrenoceptors.

In animals, alpha-2 agonists reduce muscle tremor [51] (Figure 2; figure 2 in reference [52]), explaining reduced VO2 [53]. In healthy semi-recumbent volunteers, alpha-2 agonists reduce temperature (−0.7°C with dexmedetomidine high dose: 2 μg.kg-1) and VO2 (dexmedetomidine high-dose: −18%; clonidine 5 μg.kg-1 p.o.: −13%) [54,55]. Clonidine [56], dexmedetomidine (0.4 ng.mL-1) and meperidine lower shivering threshold (−0.7 and −1.2°C respectively). The combination is additive (−2.0°C) [57]. Dexmedetomidine produces marked and linear decrease in the vasoconstriction and shivering thresholds (quoted from [9].

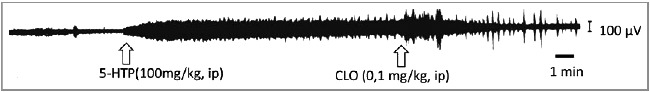

Figure 2.

Raw electromyogram (EMG) from quadriceps femoris muscle. The rat is chronically spinalized to suppress descending control. This will allow one to assess absence or presence of peripherally-evoked tremor. Note the increase in EMG after administration of 5-hydroxy-tryptophan (5HTP) and the reduction after systemic administration of an alpha-2 agonist, clonidine. Phasic bursting persists after clonidine, as observed in another setting [58]. The observation of reduced muscular activity is key to understand reduced VO2 and enlarged cardio-ventilatory reserve, after alpha-2 agonists. Reused from Tremblay, Neuropharmacology, 1986, 25, 41–46 [41] under Elsevier reuse free agreement (Dec, 06, 2017) with thanks.

3). Applied pharmacology

Alpha-2 agonists affect minimally baseline VO2 in resting volunteers (≈−15% [53–55]) but suppress increased metabolic activity (≈−50 to −80% depending of the amplitude of shivering or of the increased VO2 [53,59]). Clonidine low dose (75 μg i.v.) suppresses post-operative shivering [56]: a large reduction in VO2 was observed only during post-operative shivering itself. VO2 reduction was not observed in non-shivering patients [53], in line with the data observed in resting volunteers. By contrast, during withdrawal from remifentanil-propofol sedation and weaning from the respirator in trauma patients, a large reduction of VO2 (−41%) was observed following high dose clonidine bolus [59] (Figure 3). In some patients, when weaning from the ventilator was combined to opioid and/or alcohol withdrawal, only very high doses of alpha-2 agonists achieved VO2 control (up to 2700 μg≈38 μg.kg-1 of clonidine) (figure 2 in [59]).

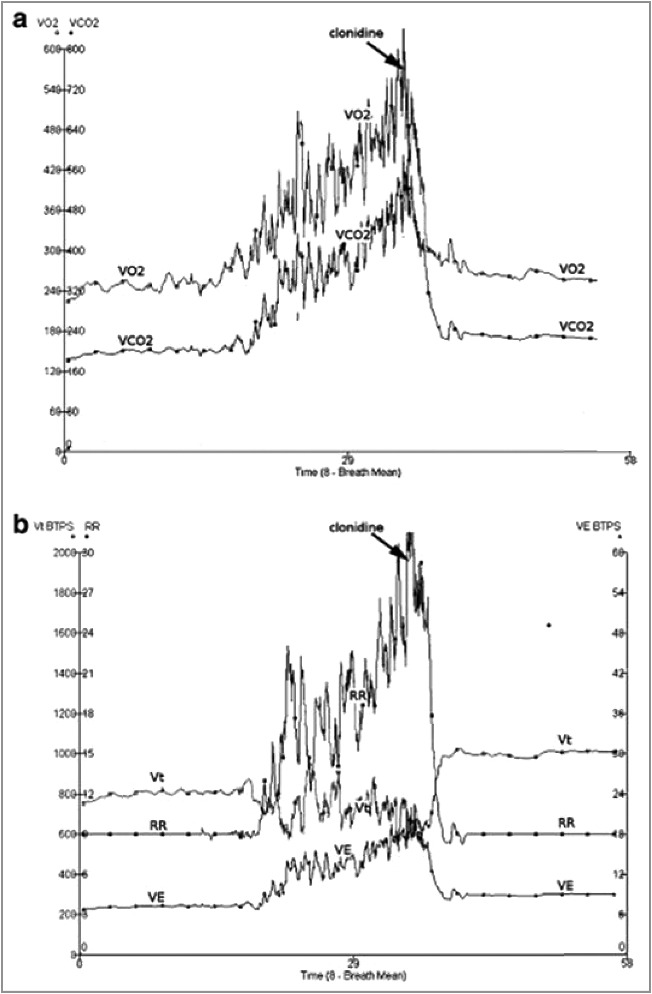

Figure 3.

Reduced oxygen consumption following administration of an alpha-2 agonist (clonidine (900 μg i.v.) during withdrawal from remifentanil-propofol sedation, while depth of sedation decreased (Ramsay score: from ≈3.5 under remifentanil-propofol to ≈2.2 after clonidine). Abbreviations: VO2: O2 consumption; VCO2: CO2 production; RR: respiratory rate; VE: minute ventilation. Note a) the normalized tachypnea and increased Vt after clonidine relative to pre-interruption of remifentanil-propofol administration b) some patients need very high dose of clonidine (2700 μg, i.e. 1.6 μg.kg-1.h-1) to lower VO2. These very high requirements of alpha-2 agonists fit with similar observation in a minority of patients in which sympathetic activity has been increased for an extended period of time, or in patients presenting with addiction and/or delirium tremens or Gayet-Wernicke (Pichot and Quintin, unpublished data). Reused from Liatsi, Intens Care Med, 2009, 35, 271–81 [45] with paid agreement from Springer (Dec, 7, 2017).

Presumably, alpha-2 agonists reset the activation threshold of cold defense effectors, evoke adaptation to a lower external temperature, suppress or minimize shivering and generate vasodilation. To our knowledge, heat transfer from core to periphery or from periphery to core is poorly described in the setting of septic shock with, respectively, elevated body temperature or spontaneous hypothermia. Suppressed shivering with an alpha-2 agonist is the opposite to the vasoconstriction and shivering evoked by surface cooling performed without “cooperative” sedation or without general anesthesia. The current practice is to use light general anesthesia (light “total intravenous anesthesia”: TIVA; “analgo-sedation”) to decrease the activation threshold of cold defense effectors for shivering: this is considered as the most efficient way to prevent shivering and achieve VO2 reduction [7]. Given the ventilatory, cognitive, immuno-suppressive [60] effects and complexity of administration of general anesthesia, our present hypothesis is at variance with the present clinical practice: we suggest not to use “analgo-sedation” with hypnotics and opioid analgesics i.e. not to use light total intravenous anesthesia5.. Minimal sedation and well preserved ventilation are key: for clinical applicability, therapeutic hypothermia will be induced in patients handled on a ward [57] or an intermediate care unit. Although patients presenting with septic shock or ARDS are handled in a CCU, suppressed vasoconstriction and shivering should be achieved simply: the activation threshold may be modified while maintaining spontaneous ventilation and « cooperative » sedation with alpha-2 agonists6..

4). Reduced vasopressor requirements?

In addition to reduced VO2 and reduced shivering, may alpha-2 agonists be of help in the setting of septic shock? In the setting of septic shock, following alpha-2 agonists, a reduction of the dose of noradrenaline was observed clinically [24,61], experimentally [24,62,63], and, post-hoc, in the setting of sepsis [64]. Outside the setting of sepsis and septic shock, administration of alpha-2 agonists in the anesthesia or CCU setting leads to reduced vasopressor [65–69] or isoproterenol [70] requirements. In the setting of neonate [24] or terminal adult [71] septic shock, an alpha-2 agonist lowers noradrenaline requirements by 90% over 13 h [24] and 25% over 6 h and 80% over 48 h [71] respectively, irrespective of unabated elevated body temperature [71]. At first glance, such observations are thoroughly counter-intuitive: how a centrally acting anti-hypertensive agent can reduce pressor requirements in vasodilated septic patients? Adrenergic receptor sensitivity to endogenous catecholamines undergoes major changes during sleep, rest, or exercise [72–74] or under pathological circumstances [75]. In resting healthy volunteers, clonidine (2 μg.kg-1 i.v. over 10 min) lowers plasma noradrenaline concentration, increases lymphocytes beta-adrenergic receptor density, and decreases the affinity of the beta receptor [76]. The kinetics of the changes is compatible with the observed changes in circulatory variables and plasma noradrenaline concentration. Presumably, a rapid externalization of the receptors occurs immediately after a reduction in sympathetic nervous activity. But the phenomenon is not observed in vitro [76]. Thus, the simplest explanation for the increased noradrenaline requirement during septic shock and the lowered noradrenaline requirement following administration of alpha-2 agonists is a switch from “hyper-innervation desensitivity” (septic shock without alpha-2 agonist: high endogenous NA plasma concentration [77]) to “denervation hypersensitivity” (septic shock with alpha-2 agonist: lowered endogenous NA plasma concentration i.e. normalized sympathetic nervous activity back toward baseline levels) [61,62,71]. As septic shock involves many factors, other explanations are possible (NO, etc.) [78,79]: a) lowered temperature leading to vasoconstriction: this does not fit with the vasodilation generated by alpha-2 agonists b) normalization of an impaired micro-circulation (see below), leading to normalized local pH back toward normal, increased sensitivity to noradrenaline and reduced extravasation. Given the reduced requirement of vasopressor observed during hypothermia [38] or normothermia [3] in the absence of administration of alpha-2 agonists and the reduction in vasopressors requirement following administration of alpha-2 agonists [24,71], a combination of fever control and alpha-2 agonist may help in refractory septic shock.

Two issues are relevant:

-

a)

Micro-circulation. In the setting of septic shock, cardiac output should be increased7. back to adequacy, defined as the output needed to match VO2. This combines pre-load and afterload manipulations of the right [80] and left ventricles, right [81] and left coronary perfusion pressures, and adjustments of rhythm, contractility, and compliance. Nevertheless, achieving adequate cardiac output does not necessarily translate into achieving adequate micro-circulation [23], i.e. mixed venous saturation or superior vena cava saturation >70–75%8. [82], CO2 gap <5–6 mmHg [83–85], lactate trending <2mM and excellent capillary refill. Few drugs achieved popularity to improve the micro-circulation [86]. Fast suppression of peripheral mottling is observed when alpha-2 agonists are administered in the setting of septic shock treated with very high dose noradrenaline (Quintin, unpublished data). Evidence-based demonstration is required.

-

b)

Renal replacement. In the setting of major acidosis and early multiple organ failure, renal replacement therapy is used early, to correct the systemic acidosis. Fever control, reduced vasopressor requirement and normalized systemic acidosis [37,87] will be achieved more rapidly, when the RRT circuit is not actively warmed-up.

To sum up, fever control reduces vasopressor requirement [3,37,38]. Therefore, fever control in patients presenting with high noradrenaline dose [5] when limited cardio-ventilatory reserve is observed, especially in the setting of “refractory”9. septic shock. Combined to fever control, the use of alpha-2 agonist may reduce the vasopressor requirements. A prospective randomized clinical trial e.g. in the setting of refractory10. [88–90] septic shock should document the hypothesis [24,61,62,71,78,79].

III). Fever control in the setting of severe ARDS?

A). Present knowledge

Data are conflicting: high fever (≥39.5°) is associated with the lowest mortality in the setting of ARDS [91]: presumably most of these patients did not suffer from a limited cardio-ventilatory reserve. By contrast, elevated body temperature>38°C in the setting of mild ARDS (200<P/F<300) is associated with increased duration of ventilation [16]. As stated with respect to septic shock [10], hypothermia<36.0°C is associated with increased mortality in the setting of mild ARDS [16,91]. However, fever is also associated with delayed weaning [16]. Therefore, aggressive fever control should be considered in mild ARDS [16]: indeed, reducing the metabolic and ventilatory demand should be among the most important of unproven rules that guides management especially in the initial stage of ARDS [92].

In the setting of severe ARDS (P/F<100 on PEEP = 5 cm H20, bilateral opacities not explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload [93]), evoked hypothermia or fever control are associated with improved gas exchange (Table 1; table 1 in reference [94]):

-

1)

Experimentally, evoked hypothermia (33°C) increases PaO2, lowers lung edema formation, and alveolar hemorrhage when exposed to high pressure controlled ventilation [95].

-

2)

Following evoked hypothermia (34°C), increased PaO2 was observed. PaO2 fell when temperature returned to 37°C. In patients presenting with ARDS (P/F ≤50, n = 8) following trauma, blood loss, and resuscitation, hypothermia was used as an alternative to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO; survival in the hypothermia group without ECMO group: 87%) [96].

-

3)

Following bronchospasm, evoked hypothermia (34.5°C, 5 days), sedation and paralysis are associated with increased PaO2 (P/F = 100 to 225–400), improved radiologic findings and recovery [97].

-

4)

Under sedation and paralysis, evoked hypothermia (33–35°C) is associated with decreased intrapulmonary shunt and VO2 and increased arterio-venous difference and O2 extraction ratio [98]: evoked hypothermia may be detrimental by decreasing O2 transport more than O2 consumption: a disequilibrium may occur11..

-

5)

Given refractory hypoxia12. (P/F = 54) and a low cardiac output, high frequency ventilation combined to evoked hypothermia (33°C, 10 days, positive end-expiratory pressure: PEEP = 30 cm H20, pancuronium-fentanyl, steep Trendelenburg position) was associated with recovery [99].

-

6)

Under general anesthesia (propofol-phenoperidine), hypothermia (32–34°C, 11 days) led to permissive hypercapnia (PaCO2≈145 mm Hg), improved P/F from a low 58 and recovery. Evoked hypothermia may be used as a “bridge” during transfer to ECMO [100].

-

7)

Moribund septic ARDS patients (P/F = 47–101 on PEEP≈10–11 cm H20; expected mortality: 100%) were allocated to state-of-the-art vs. state-of-the-art+evoked hypothermia (32–35°C, ≈70 h, discontinued if P/F >90) [39]. Under evoked hypothermia, the intrapulmonary shunt was reduced (42 to 32%) and PaO2/PAO2 increased (0.15 to 0.27). Lowered VO2 was observed during the first 6 h (243 to 217 mL.min-1, ns). O2 extraction was increased (26% to 30%), as observed earlier [98]. Death was 100 and 66% respectively in the state-of-the-art and state-of-the-art +evoked hypothermia groups [39].

-

8)

Mild evoked hypothermia (34.8 °C) in septic shock patients undergoing high-flow continuous hemofiltration reduces VO2 and venous admixture (30% to 18%), increases PaO2 and mixed venous PO2 with unchanged outcome [37]. Under continuous hemofiltration, evoked hypothermia (30.5°C, 7 days) is associated with reduced minute ventilation (30 to 6 L.min-1), increased PaCO2 (38 to 54 mm Hg) and increased P/F (118 to 235). This allows one to reduce PEEP (30 to 10 cmH20) [87]. Presumably, permissive hypercapnia allows lung rest and recovery [87].

-

9)

As P/F = 109 further worsened, very low Vt (≤4 mL.kg-1) and lowered plateau pressure (23 cm H2O to 18) were achieved using evoked hypothermia (35–36°C) and mild permissive hypercapnia (50–68 mm Hg) [101]. This temperature was selected to avoid coagulation and infection problems.

-

10)

In severe ARDS (P/F≈40–50, n = 2) refractory to veno-venous ECMO and proning (n = 1), evoked hypothermia (32–34°C, 24 h) improved oxygenation (P/F≈50 to 119 and 40 to 69 respectively). Survival occurred in one patient [94].

-

11)

PEEP (from zero to 20 cm H20) lowers cardiac output and shunt, increases P/F (calculated with FiO2 = 0.7 from table 1 in reference [102]: ≈90 to ≈115) and underestimates lung injury [103]: shunt changes as a function of cardiac output without change in ventilation/perfusion (VA/Q) ratio (figures 1 and 3 in reference [104]. Under veno-venous ECMO, in the setting of severe septic shock and ARDS requiring very high noradrenaline dose, lowering temperature (37 to 34°C) increases SaO2 from 82 to 94% [105]. Evoked hypothermia reduces cardiac output and increases the ratio ECMO flow/cardiac output: pulmonary flow and intrapulmonary shunt are reduced. Thus, an imbalance between ECMO flow and cardiac output improves oxygenation [105].

-

12)

A retrospective study of evoked hypothermia (32–34°C, ≈30 h) in the cardiac arrest setting observed lower PaCO2 and Vt, increased P/F with similar PEEP, increased compliance. The increased P/F was maintained after rewarming [106].

-

13)

Mild evoked hypothermia (34–36°C, 48 h) was generated prospectively in ARDS patients (P/F<150, n = 8) under paralysis. When historical controls are compared, the mortality is lowered (mild hypothermia: 25%; controls: 75%). More ventilator- and CCU-free days, higher P/F upon day 3 (from 86 to 255) were observed [107].

-

14)

A large (n = 101) trial on fever control in septic shock was conducted primarily on patients with moderate ARDS (50% of the patients; P/F: 153–165) [3]. The 14d mortality decrease is most relevant to the present problem. Nevertheless, no prospective randomized clinical trial addressed fever control in the setting of severe ARDS.

Table 1.

Literature search on hypothermia in the setting of ARDS. Retyped from Hayek, J Intens Care Med, 2017, 1–5 [94] with paid agreement from SAGE (Dec, 8, 2017).

| Authors | Year | n | Age | TH Temp (°C) | TH Length (days) | Etiology | Paralysis | Tidal volume | Other therapies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flachs | 1977 | >8 | 34 | Trauma, blood loss, ressuscitation | Yes | None | |||

| Hurst | 1985 | 1 | 32 | 33 | 10 | Trauma, massive transfusion | Yes | HFV | None |

| Browning | 1992 | 1 | 20 | 30 | 5 | Status asthmaticus | Yes | Halothane | |

| Wetterberg | 1992 | 1 | 20 | 32-4 | 11 | Pneumonia | PCV, peakP=40 cm H20 | Isotonic buffering, prostacyclin | |

| Villar | 1993 | 9 | 40±16 | 32-5 | 2.9±0.6 | Sepsis, trauma, pneumonia | Yes | TPN, Swan Ganz catheter | |

| Moonka | 1996 | 1 | 48 | 30.5 | 7 | Trauma, massive transfusion | Yes | Hemodialysis | |

| Matsuno | 1997 | 10 | 35 | Respiratory failure secondary to infection | None | ||||

| Erikson | 1998 | 2 | 41 | 35 | 2 | Lung transplantation : rejection vs. infection | isotonic buffering, steroids | ||

| 55 | 32 | 4 | Lung transplantation : rejection vs. infection | isotonic buffering, steroids | |||||

| Duan | 2011 | 1 | 29 | 35-36 | 6 | Aspiration | Y | 4 mL.kg-1 | NO, inhaled prostaglandin, oral PDI |

| Varon | 2012 | 4 | 32 | 1 | not available | none |

Abbreviations: HFV: high frequency ventilation; NO: nitric oxide; PCV: pressure controlled ventilation; PDI: phosphodiesterase inhibitor; TH: therapeutic hypothermia; TPN; total parenteral nutrition.

B). Alpha-2 agonists to modify the management of severe ARDS?

Time-wise, severe ARDS undergoes 3 phases. First phase: acute cardio-ventilatory distress upon admission to the CCU [108] (“shock state”), until its correction. Controlled mandatory ventilation, with paralysis, is appropriate in the setting of «Friday night ventilation» [108] to address acute cardio-ventilatory distress immediately when the patient reaches the CCU. However, the intensivist should keep in mind that the goal is to make the patient self-sufficient, ventilation-wise, as early as possible: the short time-window to skip CCU-acquired diseases implies literarily running against time. Second phase: early severe ARDS. Early ARDS is to be managed under spontaneous ventilation-pressure support as soon as the situation has improved [109], our present hypothesis. Third phase: late ARDS after 3–5 days, not considered here.

1). Working hypothesis: a new bundle?

As delineated [110–112], after correction of one factor after the other factor generating the acute cardio-ventilatory distress [108], the present hypothesis is that spontaneous ventilation combined to alpha-2 agonists helps in the setting of severe diffuse ARDS. An “analytical” bundle separates the factors involved in the ARDS conundrum, using an itemized, step by step, process:

-

a)

Position: upright position improves oxygenation [113,114] especially when severe ARDS is considered (Figure 4; panel B in electronic supplement [115]), as delineated [111,116]. Intra-abdominal pressure is to be lowered.

-

b)

Temperature: in the setting of elevated body temperature, fever control reduces VO2 [29]. As alpha-2 agonists lower VO2 [53–55], an additive effect between fever control [3,29], alpha-2 agonists [54] and noradrenaline requirements [28], lowered in the presence of alpha-2 agonists, is a possibility. As proposed in septic shock [3] and ARDS [107], fever control should be carried away for 48–72 h, depending on the cardio-ventilatory status, and the micro-circulation.

-

c)

Acidosis: adequate cardiac output implies correction of a “low PvO2 effect” [109], assessment of a possible patent foramen ovale [117] and improvement of right ventricular function [81,118]. Adequate cardiac output will improve micro-circulation [23], normalize systemic pH and suppress the systemic acidotic drive on the respiratory generator. In the setting of ARDS [119], a pH>7.23–29 is required to use spontaneous ventilation (synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation). Accordingly, pH = 7.29 appears as a cut-off point [120] if spontaneous ventilation is to be used early in the setting of ARDS. By contrast, severe acidosis generates a high RR, making spontaneous ventilation impossible [121].

-

d)

Permissive hypercapnia: lowered temperature lowers PaCO2, driving pressure, Vt [101] and respiratory rate (RR). Following alpha-2 agonist, an observation gathered in healthy volunteers [54] of lowered Vt and lowered sensitivity to CO2 may apply to mild permissive hypercapnia in the CCU. This would improve right ventricular function [122] and minimize patient self-inflicted lung injury [123] (ventilation13.-induced lung injury).

-

e)

High FiO2: a degree of permissive hypoxemia (SaO2≈88–92%) is acceptable in the setting of controlled mandatory ventilation (CMV) [124] and paralysis. By contrast, under spontaneous ventilation, heightened SaO2 at or above 96% lowers the hypoxic respiratory drive and RR [125]. Thus, in the setting of severe diffuse ARDS, firstly, immediately upon admission, the hypoxic patient is administered immediately high FiO2 = 0.8–1.0 and high PEEP, with acceptable plateau pressure. Secondly, all the other factors are to be improved, one by one, according to the equation (Vt, RR = f(temperature, pH, PaCO2, PaO2)), during the stabilization of the cardio-ventilatory distress. Thirdly, hypoxia is handled specifically, using high FiO2 and high PEEP: FiO2 is lowered to 0.4 as quickly as possible. Then PEEP is lowered from high levels (15–24 cm H20) to acceptable levels (≤10 cm H20), as soon as possible. The objective of the analytical bundle is to isolate low PaO2 as the only variable left evoking high respiratory drive. Therefore, the issue is not to fully re-open the whole lung with very high PEEP [126,127], curing P/F at once (“open lung strategy”) [126–128]. Under spontaneous ventilation-high PEEP-low pressure support, the objective is only to recruit a “penumbra area” [116] and increase P/F≈50 to P/F≈150–200. Schematically, the issue is to move from the worst case scenario (FiO2 = 1, PEEP = 24, P/F = 50) to an acceptable scenario (FiO2 = 0.4, PEEP = 10, P/F = 150): after having used the above mentioned bundle (combined if appropriate with veno-venous ECMO), the sole stimulus on the respiratory generator is hypoxemia. Then, given improved overall clinical status, early switch to continuous non-invasive ventilation should be considered immediately following correction of temperature, systemic pH, and acceptable permissive hypercapnia.

-

f)

High PEEP [129] resets the chest wall and diaphragm [130–132], lowers RR [133], minimize inflammation [134] and improves oxygenation over 12–72h [135–138]. While “focal” [139] ARDS requires low PEEP [139], diffuse ARDS requires higher PEEP [129,140,141].

-

g)

Spontaneous ventilation: Airway Pressure Release ventilation (APRV+SV) [142,143]) is under trial (BIRDS:clinicaltrials.gov). Based on our practice, we use inspiratory assistance [144] i.e. Pressure Support [110,138,145]. Pressure support reduces ventilatory demand outside the setting of ARDS [146–148]. If selected in the setting of early severe ARDS, after control of the acute cardio-ventilatory distress, pressure support should be set rigorously: high peak flow rate [148,149] to handle the high respiratory drive [150] and lower the work of breathing, low inspiratory trigger, low expiratory trigger [151] given a restrictive lung, 100% automatic tube compensation [152] to lower work of breathing, low pressure support [138,145,153] to avoid increasing Vt. In this respect, the “Smart Care” software [154] (Drager Evita XL4/infinity V500) works surprisingly well in severe “focal” ARDS [138] and lowers pressure support and Vt, as early as possible (“inverted settings” [155]), despite high PEEP levels.

-

h)

Cooperative sedation evoked by alpha-2 agonists is compatible with spontaneous ventilation [43,54,156]. After optimized volemia and A-V conduction, clonidine or dexmedetomidine infusion are administered immediately following tracheal intubation (respectively: 1–2 μg.kg-1.h-1 [157,158]; 0.75–1.5 μg.kg-1.h-1 [68] to −3<RASS<0)14.. After correction of systemic acidosis (pH>7.30, CO2 gap<5–6 mm Hg, lactate trending <2mM), paralysis is withheld as soon as possible, usually in our hands within ≈3–12h: the patient regulates his Vt (≤4–6 mL.kg-1) and RR (≤20–25 breaths per min : bpmin) by himself, under pressure support, as early as possible Presumably, a patient presenting with early multiple organ failure and major acidosis will need a longer stabilization of the acute cardio-ventilatory distress (extrapulmonary ARDS) than a patient presenting single organ failure (pulmonary ARDS). Following extubation, cooperative sedation will allow one to provide continuous non-invasive ventilation [159–161] with PEEP≤10 cm H20.

-

i)

“Rescue therapy” (controlled mandatory ventilation with low driving pressure [30] or low Vt, paralysis [162], proning [163], veno-venous ECMO, NO, inhaled prostacyclin, almitrine, etc.) should be considered if this bundle is inapplicable in the considered patient.

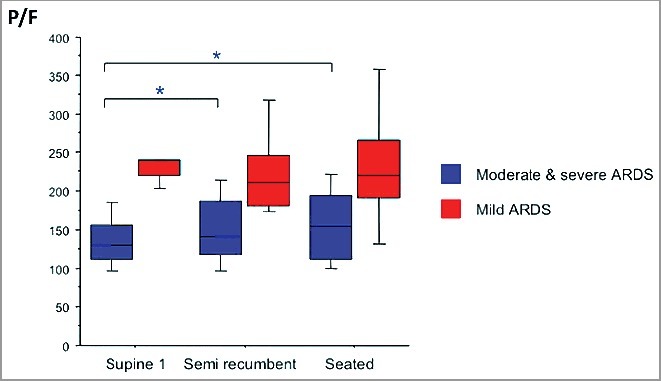

Figure 4.

Effect of seated position on PaO2/FiO2 (P/F) in moderate and severe ARDS. P/F increased from ≈125 to ≈155 in moderate and severe ARDS. Four epochs were studied: supine1, semi-recumbent, seated, supine 2 (not shown). Blue boxes represent moderate & severe ARDS defined as PaO2/FiO2 = P/F<200. Note the statistically significant, and clinically relevant, changes for moderate and severe ARDS when seated is compared to supine. Modified from Dellamonica, Intens Care Med, 2013, 39 : 1121–7 (figure in electronic supplement, panel B) under Springer reuse free agreement (Dec, 7, 2017) with thanks.

2). Spontaneous ventilation vs. controlled mandatory ventilation

Presently, the state-of-the-art combines deep sedation [164], paralysis [162] and proning [163] throughout acute cardioventilatory distress and early ARDS. The result [163] is remarkable, halving mortality (prone: 24 vs. supine: 41%, ≈17 vs. 19 days of invasive ventilation respectively, circa 4–5 days of general anesthesia and paralysis; Guerin, personal communication). The use of general anesthesia and paralysis [162,164] is based on suppressing ventilator-patient asynchrony [165] and lowering VO2 for 48 h after admission to the CCU. Rescue therapies are used without paying attention to lowering VO2 in the setting of limited cardio-ventilatory reserve. As there is no randomized trial showing a benefit of CMV+paralysis+general anesthesia vs. normothermia+spontaneous ventilation+cooperative sedation, these papers [162–164] offer no appropriate control15., with respect to the present hypothesis. The weight of these data [162,163] rests on absence of knowledge and existing clinical practice rather than on full evidence-based medicine with appropriate control group. As the management of severe ARDS requires deep sedation [164], the dogma of deep sedation combined to paralysis is reinforced when hypothermia (34.5°C) is considered [97]. Such successful management [97] is part and parcel of advances within previous clinical management. Nevertheless, the present advancement in physiopathology and pharmacology allows one to propose an alternative bundle without general anesthesia and paralysis.

The ARDS is a pathophysiological conundrum (temperature, pH, PCO2, Vt, RR, inflammation, “wet” lung, etc.). Adding therapeutic complexity to this conundrum is unwise. General anesthesia, paralysis and controlled mandatory ventilation are followed by reduced cardiac output. In turn, lowered cardiac output leads to lowered P/F [103,109]. Then iterative echocardiography, pre-emptive volume loading [166,167], vasopressors, inotropes, etc. are needed. Schematically, the intensivist has two options: general anesthesia, paralysis, controlled mandatory ventilation, etc., then controlling for the deterioration evoked by this combination. Conversely, the intensivist should concentrate on improving low PaO2, the hallmark of ARDS, by shortening the course of general anesthesia, paralysis, controlled mandatory ventilation. From the data delineated in this review, a therapeutic shift (VO2 control, early spontaneous ventilation-high PEEP-low pressure support, cooperative sedation) is now possible, after swift and itemized control of the factors evoking the acute cardio-ventilatory distress, as delineated above.

3). Alpha-2 agonists

a). Pharmacology

Briefly [157,111], alpha-2 agonists evoke: i) ataraxia (slow-wave sleep [168,169], “arousable” [170] or “cooperative sedation” [171] and minimized emergence delirium [44–46]. In addition, a degree of analgesia [172] and analgognosia [173] is observed following alpha-2 agonist administration. Deducing sedative properties from circulatory properties, or vice-versa, is irrelevant: circulatory and cognitive effects of alpha-2 agonists are anatomically un-related [174], being located respectively in the lower brain stem vs. the forebrain. The only common link is the alpha-2 adrenergic receptor distributed widely in the central nervous system and the autonomic nervous system: this wide distribution explains the multiple, protean (“pleiotropic”), effects of the alpha-2 agonists. ii) absence of depression of the respiratory generator [43,156], increased number of ventilator-free days [175,176]. iii) increased peak expiratory flow rate and forced expiratory volume (FEV1) in asthmatic patients [177]. This is relevant in the setting of early ARDS: an intrinsic PEEP as high as 7 cm H20 is observed [178]. iv) reduced intrapulmonary shunt [179,180]. v) reduction in pulmonary hypertension evoked by normalizing the sympathetic hyperactivity [181]. vi) increased left ventricular diastolic compliance [182] and systolic performance [183–186]. vii) improved micro-circulation [187,188] and lactate clearance [189], reduced vasopressor requirement in the setting of septic shock [24,71] and sepsis [64]. viii) reduced microvascular permeability [190]. ix) increased diuresis in the setting of ascites [191–193], cardiac failure [186] and critical care [67]. x) reduced intra-abdominal pressure [194]. xi) lowered PCT [24] and pro-inflammatory IL6 [195], increased anti-inflammatory IL10 [196].

In semi-recumbent healthy volunteers [54], dexmedetomidine high-dose (2 μg.kg-1.h-1) reduces minute ventilation. This affects predominantly Vt (−33%) as opposed to RR. PaCO2 increased ≈+4 mmHg. The combination of lowered minute ventilation and increased systemic CO2 indicates lowered sensitivity to hypercapnia16. [54]. Under alpha-2 agonist, during CO2 rebreathing (PaCO2 = 55 mm Hg), minute ventilation was lowered (−43% from baseline; ≈−46% vs. placebo [calculated from figure 4 in [54]]. pH and PaO2 were unchanged. The point is whether increased set-point to CO2, lowered slope, lowered Vt, absence of acidosis (figure 6 in [54], reduced temperature [54] and VO2 (−17% [54]; −13% [55]) present relevance when early severe ARDS is considered. After controlling all confounding factors, will alpha-2 agonists allow one combining fever control, permissive hypercapnia and high PEEP-low pressure support and achieving low Vt and RR? Following an alpha-2 agonist, in healthy volunteers, lowered Vt and unchanged RR are observed [54]. By contrast, in the setting of weaning from the ventilator and alcohol/opiates withdrawal, Vt is unchanged and RR lowered [59]. Indeed, lowering RR has relevance in the setting of ARDS [125,150,197]. In our hands, despite a PaCO2≈45–55 mm Hg in ARDS patients, no hyperpnoea nor tachypnea were observed under alpha-2 agonists and spontaneous ventilation-low pressure support, following control of temperature and systemic acidosis (Quintin, unpublished observations). Given the present hypothesis, recent data [120,150,198] require an itemized discussion in order to carve out a niche for alpha-2 agonists:

b). High Vt in early ARDS

One key issue addresses the possibility to handle tachypnea and hyperpnoea in the setting of acute cardio-ventilatory distress occurring during early severe acute respiratory distress syndrome.

High Vt:

-

i)

Experimentally, inspiratory resistive breathing increases alveolar-capillary membrane permeability, deteriorates P/F and ventilatory mechanics, evoking inflammation [199].

-

ii)

Exercise: Intense exercise increases red cells and proteins concentrations in the broncho-alveolar lavage [200]: this requires analysis, bearing in mind patient's-self-inflicted lung injury (P-SILI) [123]. However, marathoners pulls Vt>25 mL.kg-1 for hours without major untoward effects [201].

-

iii)

early ARDS: in the early phase of ARDS under non-invasive ventilation (NIV) [150], the sicker patients (P/F = 122 ; range = 98–191) generated a large Vt = 10.6 mL.kg-1 (range = 9.6–12) and required intubation. However neither pH (success: 7.41 vs. failure: 7.45) nor PaCO2 (no intubation required: PaCO2 = 36; intubation required: PaCO2 = 32 mm Hg) allows one partitioning hyperpnoea along the equation (Vt, RR = f(pH, PaCO2, etc.)).

-

iv)

late ARDS: rapid shallow breathing (RR = 27–32 bpmin; decreased Vt: 243–335 mL, increased respiratory drive [P0.1 = 4.9–6.6 cmH2O], intrinsic PEEP = 2–5 cmH2O) was observed in the chronic phase of lung injury (≈14 days) [197]. This represents muscular weakness or impending fatigue, at variance with early ARDS.

Taken together these data suggest to look for P-SILI in the early phase of ARDS in order to suppress it. The altered geometry of the chest wall (including the diaphragm), lowered functional residual capacity (FRC) [130], atelectasis [202], lung water [203], inflammation, etc. imposes generating large end-inspiratory transpulmonary pressure to re-open the alveoli. This generates a large Vt and harms the lung. Strong patient's inspiratory efforts are observed even with pressure support as low as 7 cm H20 [150]: Vt cannot be controlled noninvasively despite very low pressure support [204]. The limiting factor is not the ventilator's set up but the patient himself (hyperpnoea: “soif d'air”) which generates P-SILI.

The first move to handle a large Vt is an appropriate resetting of the geometry of the chest wall. Experimentally, under spontaneous ventilation, a) high PEEP (17 cm H20 vs. ≈6 cm H20) reduces the curvature of the diaphragm, reduces the generation of negative transpulmonary pressure and lung dyscoordination [132] b) expiratory diaphragmatic mechanics is improved [131]. Clinically, a) spontaneous ventilation improves rib cage mechanism [130] b) increasing PEEP (0 to 10 cm H20) increases the expiratory time and lowers respiratory rate at constant Vt: the Hering-Breuer reflex acts within 1 breath17. [133]. The RR is lowered more in patients with impaired compliance, as opposed to patients without impaired compliance [133]. To sum up, high PEEP increases the expiratory time [133], restores the functional residual capacity and cures hypoxemia over 12–72 h [135,136].

Pulmonary edema. Strong inspiratory efforts maximize the possibility of pulmonary edema (figure 1 in reference [205]. This mimics hydrostatic post-obstructive pulmonary edema [206]. In figure 1 of [205], when spontaneous ventilation is added to mechanical breath18., the hydrostatic transvascular pressure19. increases from +2 to +28 mm Hg. However, the reasoning [205] accounts for only one side of the phenomenon: the lymphatic transmural pressure gradient is positive under spontaneous ventilation throughout the ventilatory cycle, at variance to what is observed under controlled mechanical ventilation [207]. Thus, under spontaneous ventilation, lymph resorption may counteract transalveolar water leakage: this is an unsolved issue. Pharmacologically, an alpha-adrenergic blocker, phentolamine, restores alveolar liquid clearance following hemorrhagic shock [208]. Therefore, given the ARDS lung, the question of lung water being lowered by a combination of gentle spontaneous ventilation and normalized sympathetic activity is to be studied.

At first glance, a large Vt in the setting of early ARDS [150] favors [205] controlled mandatory ventilation and paralysis. Only mild spontaneous efforts can be tolerated to recruit the collapsed lung [198,209]. During the early acute cardio-ventilatory distress, acidosis, hypercapnia, hypoxemia, pain, elevated body temperature, pulmonary inflammation evoke large Vt. Thus, each factor should be handled separately during control of the acute cardioventilatory distress. The equation (Vt, RR = f(temperature, pH, PaCO2, PaO2)) should be re-written: (Vt, RR = f(temperature [VO2], pH [lactate, mixed venous SO2, CO2 gap, metabo-reflex20.], PaCO2, PaO2, inflammation, “cooperative” sedation)). To separate these various items, several questions need analysis:

-

i)

Differences between severe vs. mild or moderate ARDS: The mechanisms set in motion between mild and moderate ARDS are identical [145]: the issue is not the severity of lung injury itself but the ability of spontaneous breathing first to generate enough end-inspiratory transpulmonary pressure21. to open collapsed units and second the settings of PEEP and/or expiratory time to maintain the collapsed units open at end-expiration. This will determine whether spontaneous breathing is protective or harmful [145]. We presume this holds true in the setting of severe ARDS.

-

ii)

Lowering PS level [155] is presumably not sufficient [204] in order not to increase an already enlarged Vt evoked by the severity of the disease [150].

-

iii)

Cooperative sedation may be the pharmacological adjunct of a physiology-based management. Our observations [137,138,210] are at odd with [150,204]: combined to fever control, pH and PaCO2 control and alpha-2 agonists, high PEEP-low pressure support [145,153,155] allow one to observe a low Vt, acceptable RR, no signs of ventilatory fatigue (anxiety, nasal flaring, sternal notch retraction, use of accessory muscles and thoraco-abdominal dyscoordination). The analytical management delineated above should minimize the duration of controlled mandatory ventilation with paralysis, away from a prescription which entails an arbitrary length: 24- 48 h [162,211].

c). High transpulmonary pressure generated by pressure support

Spontaneous ventilation-pressure support may be harmful even beyond the period of early acute cardioventilatory distress [150]. Spontaneous ventilatory efforts make pleural pressure more negative and increases transpulmonary pressure at identical airway pressure [198,212]. Thus, “naïve” [213] use of spontaneous ventilation-pressure support generates a high transalveolar pressure: pressure support = 18 cm H2O evokes transpulmonary pressure = 51 cm H20 [213]. Transpulmonary pressure and Vt reach excessive levels despite low airway pressure when attention is not paid to the Vt delivered under pressure support [214]. This could be a consequence of either a high pressure support (ventilator-induced lung injury) or high ventilatory demand (P-SILI), or both.

d). Lung dyscoordination

Under CMV and paralysis in an ARDS patient, simultaneous inflation of lung regions occurring at different inflation rates is observed. By contrast, upon spontaneous ventilation, inflation of dependent lung region in the lowest position (dependent lung region, usually at the base of the lung in the erect patient or the dorsal part of the lung in the supine patient) occured. This inflation was greater than with controlled breaths [215]: this is a positive finding. Furthermore, the early inflation of the dependent lung region was accompanied by simultaneous transient deflation of non-dependent region: during early inspiration, gas moves from non-dependent regions to dependent regions causing lung dys-coordination (“pendel-luft”; figure 1 and table 1 in reference [198]. Thus, asynchronies develop within the lung under spontaneous ventilation [198]. However this observation occurred in one acidotic patient (pH = 7.28; PaCO2 = 46 mm Hg; Base excess≈−8; Vt = 532 mL). Presumably, acidosis increases the inspiratory effort and generates P-SILI. To hold true, the reasoning [198] needs replication in a large group of non-acidotic patients.

When atelectasis occurs, lung dyscoordination [198] is of further concern (figure 1 in reference [209]: an atelectatic lung (“focal” ARDS [139] does not behave as an healthy homogeneous lung (“fluid-like behavior”). The diaphragmatic contraction is concentrated asymmetrically in dependent lung regions (“solid-like behavior”): a pendelluft is possible. Furthermore, the overstretch reinforces inflammation. This view holds for “focal” or patchy [139] ARDS. It is unknown whether this view hold true when diffuse [139] ARDS is considered. Furthermore, this view does not account for the modification of the geometry of the diaphragm: first, in the supine position, the human diaphragm subsides with paralysis [216]. Second, under spontaneous breathing and high PEEP, the geometry of the pig diaphragm is restored [132], generating lower transpulmonary pressure.

The current state-of-the-art [162–164] claims curing all the problems, at once, by combining general anesthesia, paralysis and proning: paralysis suppresses patient-to-the-ventilator asynchronies, intrapulmonary overstretch, pendelluft and inflammation. However, to skip CCU-acquired diseases, the point is that the trachea of the patient should be extubated as early as possible. There are no data addressing the duration of controlled mandatory ventilation with paralysis to obviate the tachypnea and hyperpnea observed during the acute cardio-ventilatory distress: 24 h [211]? 48 h [162] ? 4–5 days [163]? This requires a specify study, opposing the analytical management delineated above vs. state-of-the-art management. Meanwhile, CCU-acquired diseases creep in: we observed repeatedly ARDS patients left several weeks under paralysis (Quintin, unpublished data). Rather than resorting to a black box (general anesthesia, CMV, paralysis, proning) to solve the ARDS conundrum, physiopathological analysis will help sorting out, one by one, the factors involved, as early as possible during the management of the acute cardio-ventilatory distress.

e). Awake ECMO: Spontaneous ventilation in the setting of early severe ARDS?

Spontaneous ventilation on ECMO prevent barotrauma, volutrauma, circulatory impact of sedation, diaphragmatic dysfunction, ventilator-acquired pneumonia and sepsis [120]. Therefore, cooperative awake patients presenting with early severe ARDS under veno-venous ECMO were maintained under spontaneous ventilation with minimal sedation (27% of ARDS patients; 6 out of 8 extubated before ECMO but 50% re-intubated during the whole course of ECMO lasting 11 days, 38% of ECMO days spent on spontaneous ventilation; survival : 75%) [120]. Gas flow was increased to ≈84% of CO2 production, aiming for near-apnea when the whole VCO2 production is cleared out by ECMO. This suppresses the respiratory drive generated by CO2, as proposed above (§ III B 1). Nevertheless, at identical VO2, only 50% of the ARDS patients lowered their RR<25 bpmin and reduced pressure esophageal swings. Thus, dyspnea persists in half of the ARDS-ECMO patients, despite suppressed CO2 drive: another mechanism comes into play, e.g. inflammation22..

The patients which sustain spontaneous ventilation under ECMO are less acidotic and present lower out-of-hospital referral, duration of ventilation before ECMO (1 vs. 3 days), higher P/F (86 vs. 76), higher pH (7.29 vs. 7.23), similar PaCO2≈61–2 mm Hg, less non-aerated tissue (43 vs. 56%) and better cough ability [120]. When compared to the non-ARDS patients (transplant, acute decompensation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), the ARDS patients under spontaneous ventilation with ECMO present a lower CO2 tension measured at entry of the oxygenator [120]. A putative explanation for this surprising result is that the ARDS patients present worse peripheral micro-circulation and/or inadequate systemic circulatory improvement, when compared to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or transplant patients. Nevertheless, this paper reports a major breakthrough [120], at variance with deep sedation [164], 48 h paralysis [162], and proning [163].

These data [120] show that the equation (Vt, RR = f(temperature, pH, PaCO2, PO2)) does not hold in most awake ARDS patients. Dyspnea is unrelated to CO2 drive, as CO2 removal is nearly complete. Another possibility would be dyspnea related to a huge degree of inflammation present during early ARDS [120]. Thus, the equation should be: (Vt, RR = f(temperature, systemic and local pH i.e. metabo-reflex, PaCO2, PaO2, inflammation, cooperative sedation))? As the feasibility of the awake+veno-venous ECMO+spontaneous ventilation technique appears limited when severe ARDS with another organ dysfunction is considered [120], our hypothesis [110,112] needs reformulation:

-

i)

physiology: could fever control be of help to lower Vt and RR? Each factor involved in generating tachypnea or hypercapnea should be improved, one factor after the other: the conundrum is to be dismembered. The data [120] suggest that the patients sustaining spontaneous ventilation under ECMO are either less sick or more adequately managed with respect to microcirculation. Presumably, a higher systemic pH, improved cardiac output and microcirculation would increase the feasibility of awake-ECMO-spontaneous ventilation.

-

ii)

pharmacology: Inflammation is prominent is this setting [120]. Should a short course of steroids considered? Conversely, alpha-2 agonists lower inflammation [24,195,196]. This anti-inflammatory property may add up to other properties (see III, B, 3, a).

To sum up, after itemized correction of the acute cardio-ventilatory distress [108], the combination of fever control, upright position, rigorous control of pH, PaCO2, micro-circulation, spontaneous ventilation with low pressure support (with or without veno-venous ECMO) and administration of alpha-2 agonists should isolate hypoxemia as the only variable addressed with high FiO2 [125] lowered as early as possible), and high PEEP-low pressure support. Low Vt and RR should be achieved to allow for spontaneous ventilation, as early as possible, in the setting of early severe ARDS in order to cause no self-inflicted harm to the lung.

IV). Perspectives

The suggestion for using fever control in the setting of septic shock and ARDS is substantiated by preliminary findings [3,71,137,138,217] and provides a rationale to set up randomized prospective trials [218] combining pharmacological treatment to a physiological management in the setting of limited cardio-ventilatory reserve, septic shock and/or early severe ARDS. Two issues deserve comments: a) may the intensivist improve his therapeutic approach to major CCU illness? b) does major, prolonged, CCU illness fits within a larger overall disease?

A). Extending the analysis?

The 2018 approach combines analytic diagnosis with analytic therapeutics: fever control ((3) and present hypothesis); improved macro [81,103,109] and micro-circulation [23,24] to handle circulatory shock, peripheral shut-down, systemic and local acidosis; controlled mandatory ventilation with paralysis and proning (or present hypothesis: spontaneous ventilation-high PEEP-low pressure support [111,155]) to lower the work of breathing and increase ventilator-to-patient synchrony; anti-infectious strategy, etc. Nevertheless, we surmise that this organ-targeted approach (heart, lung, kidney) should extend the analysis to other systems:

-

1)

cognition: minimized cognitive dysfunction following alpha-2 agonists [44,219].

-

2)

sympathetic activity: the normalization of the sympathetic hyperactivity toward baseline levels may normalize more quickly the micro-circulation (see above) and inflammation. Alpha-2 agonists increase the concentration of the anti-inflammatory IL10 [196] and lower pro-inflammatory cytokines [195]. This raises 2 questions. Firstly, the issue of the anti-inflammatory vs. the pro-inflammatory effects of general anesthesia (propofol, benzodiazepine and opioid analgesics [220] is complex [60]. The anti-inflammatory effects of anesthetics may occur in the setting of a pre-existing low inflammatory state (e.g. brief general anesthesia in the setting of minor surgery performed on an healthy patient). By contrast, anti-inflammatory effects of general anesthetics are at best unproven when they are administered, firstly for days/weeks in the CCU, secondly in the setting of a high inflammatory state generated by septic shock or ARDS. Conversely, the alpha-2 agonists may lower pro-inflammatory cytokines and increase anti-inflammatory cytokines as a consequence of normalized sympathetic activity, back toward baseline activity.

-

3)

inflammation: the influence of inflammation on the circulatory response to sepsis is underappreciated, e.g. when it comes to HR. For example, in the setting of experimental sepsis, tachycardia is independent of the sympathetic nervous system but mediated by inflammatory mediators [221]. In septic patients, the effect of ibuprofen in lowering HR (≈115 to 100 bpmin) [26] may be a consequence of lowered inflammation or of lowered temperature.

In septic shock, intertwined pro- and anti-inflammatory mechanisms lead to immunoparalysis [222]. Extreme pro-inflammatory activity is associated with a cytokine “storm”, hypotension refractory to high doses of noradrenaline and early death [88–90]. Extreme anti-inflammatory response is associated with a dysfunctional innate immune system and death (Figures 5 and 6; figure 1B in [223]; figure 2 in [224]). The sympathetic system is an adaptive system with complex anti- [225,226] and pro- [227] inflammatory effects under physiological conditions. By contrast, under major prolonged pathophysiological condition, this adaptive system becomes a mal-adaptive system23.. The massive release of noradrenaline presumably upsets the fine tuning of adrenergic receptors with functional consequences on immuno-competent cells (macrophages, natural killer and dendritic cells, neutrophil, eosinophil, basophil cells, T cells, natural killer T Cells). Secondly, acute activation of the sympathetic system inhibits the innate immune system [228,229]. Conversely, inhibited sympathetic activity may possibly evoke anti-anti-inflammatory effects: could this generate pro-inflammatory effects? Thirdly, the sympathetic system may present different actions in the acute (septic shock, etc.) vs. chronic (auto-immune diseases, cancer) settings. Thus a manipulation of the sympathetic system in the setting of septic shock is not straightforward.

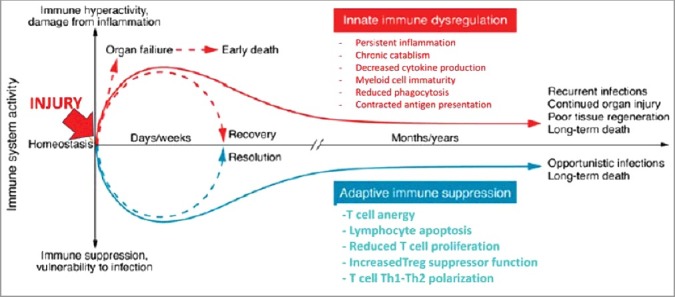

Figure 5.

Inflammatory responses in sepsis. Immune responses in sepsis are determined by many factors including pathogen virulence, size of the bacterial inoculum, comorbidities, etc.

A) Although both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses begin rapidly after sepsis, the initial response in previously healthy patients with severe sepsis is typified with an overwhelming hyperinflammatory phase (fever, hyperdynamic circulation, shock). During the early phase, deaths are generally caused by circulatory collapse, metabolic derangements, and multiple organ failure. Although no specific anti-inflammatory therapies have improved survival in large phase III trials, short-acting anti-inflammatory or anticytokine therapies offer a theoretical benefit. B) Many patients who develop sepsis are elderly with co-morbidities that impair immune response. When these individual develop sepsis, a blunted hyperinflammatory phase is common. Patients develop impaired immunity and an anti-inflammatory state;. Immuno adjuvant therapy offers promise in this setting. C) A third theoretical immunological response to sepsis is characterized by cycling between first hyperinflammatory then hypoinflammatory states. The development of a new secondary infection lead to a repeat hyperinflammatory response and may recover or re-enter the hypoinflammatory phase. Patients may die in either state. There is less evidence for this theory. The longer the sepsis carries on, the more likely a patient is to develop profound immunodepression. Presumably figures 5,6 and 7 look up at phenomenons occurring simultaneously with respect to metabolism and the immune system. This raises the question: should normalized sympathetic activity, normothermia and immuno-stimulation be combined? Reused from Hotchkiss et al, Lancet Infect Dis, 2013, 13, 260–8 223under Elsevier free reuse agreement (Dec, 6, 2017) with thanks.

Figure 6.

Immune dysregulation in sepsis. New insights into immune dysregulation were achieved using samples from deceased septic patients and severely injured trauma patients. An enduring inflammatory state driven by an upregulated innate and a suppressed adaptative immunity culminates in persistent organ injury and death. Accordingly, 80% of patients presented unresolved septic foci observed during a post mortem study (Torgensen 2009 quoted from [223]. The unabated initial inflammatory process contributes to organ failure and early mortality. This maladative syndrome is improved by newer “analytic” management. However, considering that the vast majority of sepsis survivors are elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, the short-term gain in survival have been merely pushed back by months or years. The widespread consensus is that persistent derangement in innate and adaptive immune systems are the main culprits driving long-term mortality. This raises the question: does normalized sympathetic hyperactivity would in turn normalize a dysfunctional innate immune system? Reused from Delano, J Clin Investigation, 2016, 126, 23–31 [224] under American Society of Clinical Investigation paid agreement (Dec, 6, 2017).