Abstract

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (cll) is the most common adult leukemia in North America. In Canada, no unified national guideline exists for the front-line treatment of cll; provincial guidelines vary and are largely based on funding. A group of clinical experts from across Canada developed a national evidence-based treatment guideline to provide health care professionals with clear guidance on the first-line management of cll. Consensus recommendations based on available evidence are presented for the first-line treatment of cll.

Keywords: Key Words Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, cll, treatment, prognosis, fitness

INTRODUCTION

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (cll) is a clinically and biologically heterogeneous disease, and the most common adult leukemia1–4. According to 2016 statistics, the annual incidence of cll in Canada is about 24005.

Guidelines developed by the International Working Group on CLL provide concise standardized criteria for the diagnosis of cll that include a clonal B lymphocytosis in the peripheral blood ( 5.0×109/L) with a characteristic morphology and immunophenotype6. In most cases, examination of the bone marrow is not required for diagnosis. Heterogeneity in the clinical course of cll is attributable mainly to variations in the biology of the disease and, particularly, genetic lesions that correlate with response to therapy, the most relevant prognostic factor for overall survival (os)7–9. Two widely accepted clinical staging methods—the Binet and Rai systems—are the simplest and best-validated means for identifying patients who require treatment and for predicting survival10–12. Clinical staging relies solely on physical examination and standard laboratory tests, and does not require computed tomography imaging. Furthermore, with limited value in predicting patient outcome at diagnosis, computed tomography is not recommended outside of clinical trials13.

Recent advances in treatment since about 2008 have significantly improved outcomes in cll; however, the disease is still considered incurable except in rare cases of allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (allo-hsct)4,14. Consequently, the goal of treatment is to achieve effective and durable disease control [measured as progression-free survival (pfs) and os], with minimal toxicity and acceptable quality of life14–16. With the availability of several new therapeutic options, treatment decisions based on individual and disease characteristics are paramount in achieving the best outcomes for patients.

Several international guidelines for cll have been published6,14,17–20; however, no unified national cll guidelines have been developed in Canada. Although individual provinces have created guidelines, those guidelines differ in their recommendations and are based primarily on the availability of therapeutic options in the provincial formulary16,21–23. Accordingly, an evidence-based national treatment guideline that is supported by Canadian hematologists is needed to ensure that all patients with cll in Canada have access to the best available care. In association with Lymphoma Canada, a group of Canadian cll experts therefore developed a national evidence-based consensus guideline for the first-line management of patients with cll.

METHODS

An initial literature search, plus two updates, queried 3 databases (medline, PubMed, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews) to identify meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (rcts), and single-arm prospective studies published between January 2000 and July 2017 that investigated first-line treatment of cll. Key search terms for each question were combined with the Medical Subject Heading term “leukemia, lymphocytic, chronic, B-cell.” In addition to those searches, abstracts from the proceedings of selected conferences (American Society of Hematology, European Hematology Association, American Society of Clinical Oncology) held between January 2015 and July 2017 were hand-searched. The ClinicalTrials.gov and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials Web sites were also searched for trials in progress. Language of publication was restricted to English. Detailed screening of the full-text versions of all studies was performed to identify the final list of studies. Study selection was limited to those that met these criteria: confirmed diagnosis of cll; adult study population ( 18 years); prospective design; rct, comparative, or single-arm trial with 20 or more study participants; evaluation of first-line treatment for cll; and inclusion of survival outcomes (pfs, os). When rct data relating to a particular question were available, only the rcts were included. When few rcts relating to a particular question were identified, prospective single-arm studies were considered. National Comprehensive Cancer Network categories of evidence and consensus were used to grade the level of evidence supporting recommendations24. Details of those categories are presented in Table i.

TABLE I.

U.S. National Comprehensive Cancer Network categories of evidence and consensus

| Category | Criteria |

| 1 | Based on high-level evidence, there is uniform consensus that the intervention is appropriate. |

| 2A | Based on lower-level evidence, there is uniform consensus that the intervention is appropriate. |

| 2B | Based on lower-level evidence, there is consensus that the intervention is appropriate. |

| 3 | Based on any level of evidence, there is major disagreement that the intervention is appropriate. |

GUIDELINE

Question 1

What prognostic investigations should be performed in patients with previously untreated cll?

Background

The clinical staging systems described by Rai and Binet more than 40 years ago have proved useful as prognostic tools; however, they are not able to determine an individual patient’s ongoing clinical course, particularly in the early stages. Prognostic biomarkers provide information about a patient’s overall cancer outcome regardless of therapy. Since about 2004, significant progress has been made in identifying host- and tumour-related prognostic biomarkers, including serum markers, cytogenetic abnormalities, and gene mutations—although relatively few have been prospectively validated within clinical trials25. The ability to predict the outcomes of newly diagnosed patients with cll has remarkably improved, but ideally, the hematology community would like to have predictive biomarkers that can help to determine which therapy will work best for a given patient. To date, however, no predictive biomarkers for cll have been validated in prospective clinical trials.

Summary of Evidence

Multivariable analyses of known prognostic biomarkers influencing pfs or os were reported in eight rcts and two meta-analyses of rcts evaluating first-line treatment of cll (Table ii). In the rcts, del(17p) or TP53 mutation (or both), del(11q), unmutated IGHV (ighv-u), β2-microglobulin (β2M) concentrations of 3.5 mg/L or greater, and serum thymidine kinase concentrations of 10 U/L or greater were most commonly reported as negative prognostic biomarkers for pfs. Only del(17p) or TP53 mutation (or both), ighv-u, β2M greater than 3.5 mg/L, and thymidine kinase greater than 10 U/L were independently predictive of reduced os. Either or both of TP53 mutation and del(17p) were similarly predictive of very poor pfs and os after chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy with purine analogs or alkylating agents30,32,35–37. In the cll8 trial from the German CLL Study Group (gcllsg), pfs was shorter for patients with del(11q). However, in that subgroup, the 5-year os with fcr (fludarabine–cyclophosphamide–rituximab) therapy was significantly superior to that with fc (fludarabine–cyclophosphamide), suggesting that, despite the shorter duration of remission conferred by del(11q), these patients respond well to first-line fcr therapy31.

TABLE II.

Independent prognostic factors in chronic lymphocytic leukemia

| Reference | Treatment | Patients (n) | Analysis | Independent prognostic factors for survival | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Progression-free | Overall | ||||

| Randomized studies | |||||

|

| |||||

| Byrd et al., 2003, and Woyach et al., 201126,27 (Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9712) | Fludarabine–rituximab (sequential vs. concurrent rituximab) | 104 | Unmutated IGHV, del(17p) or del(11q) | Unmutated IGHV | Unmutated IGHV, del(17p) or del(11q) (combined in multivariable analysis) |

|

| |||||

| Eichhorst et al., 200928 (German CLL Study Group, CLL5) | Fludarabine vs. chlorambucil | 193 | Thymidine kinase, β2-microglobulin | 3.5 mg/L β2-Microglobulin | 3.5 mg/L β2-Microglobulin |

|

| |||||

| Robak et al., 201029 (Polish Adult Leukemia Group, CLL3) | Fludarabine–cyclophosphamide vs. cladribine–cyclophosphamide | 423 | β2-Microglobulin, CD38, del(17p) or del(11q) | del(17p) or del(11q) (combined in multivariable analysis) | del(17p) or del(11q) (combined in multivariable analysis) |

|

| |||||

| Hallek et al., 2010, Stilgenbauer et al., 2014, and Fischer et al., 201630–32 (German CLL Study Group, CLL8) | Fludarabine–cyclophosphamide vs. fludarabine–cyclophosphamide–rituximab | 817 | del(17p), TP53 mutation, del(11q), del(13q), unmutated IGHV, β2-microglobulin, thymidine kinase | del(17p), del(11q), thymidine kinase 10 U/L, unmutated IGHV, TP53 mutation | 3.5 mg/L, β2-microglobulin del(17p), thymidine kinase 10 U/L, unmutated IGHV, TP53 mutation |

|

| |||||

| Oscier et al., 201033 | Fludarabine vs. fludarabine–cyclophosphamide vs. chlorambucil | 777 | β2-Microglobulin, CD38, TP53 del or mutation, del(11q), unmutated IGHV | TP53 del or mutation, β2-microglobulin>4 mg/L, del(11q), unmutated IGHV | TP53 del or mutation, unmutated IGHV, β2-microglobulin>4 mg/L |

|

| |||||

| Geisler et al., 201434 (U.K. LRF CLL4) | Fludarabine–cyclophosphamide–alemtuzumab vs. fludarabine–cyclophosphamide | 281 | del(17p), del(11q), +12, β2-microglobulin | del(17p) | del(17p) |

|

| |||||

| Eichhorst et al., 201635 (German CLL Study Group, CLL10) | Bendamustine–rituximab vs. fludarabine–cyclophosphamide–rituximab | 561 | del(11q), del(13q), unmutated IGHV, β2-microglobulin,thymidine kinase | del(11q), thymidine kinase 10 U/L, unmutated IGHV | Not reported |

|

| |||||

| Estenfelder et al., 2016, and Herling et al., 201636,37 (German CLL Study Group, CLL11) | Chlorambucil–obinutuzumab vs. chlorambucil–rituximab vs. chlorambucil | 781 (161 included in multivariate analysis) | del(17p), TP53 mutation, del(11q), del(13q), unmutated IGHV, β2-microglobulin,thymidine kinase,ATM mutation | Unmutated IGHV, del(17p) or TP53 mutation (or both), ATM mutation,thymidine kinase 10 U/L | Unmutated IGHV, 3.5 mg/L, β2-microglobulin del(17p) or TP53 mutation (or both), del(11q),thymidine kinase 10 U/L |

| Meta-analyses | |||||

|

| |||||

| Pflug et al., 201438 (German prognostic score) | 3 RCTs from the German CLL Study Group (CLL1, CLL4, CLL5) | 1948 | Cytogenetics, gene mutations,serum markers, IGHV | Not reported | del(17p), del(11q), unmutated IGHV, β2-microglobulin>3.5 mg/L, thymidine kinase 10 U/L |

|

| |||||

| International CLL-IPI working group39 (international prognostic index) | 8 RCTs | 3472 | Cytogenetics, gene mutations,serum markers, IGHV | Not reported | del(17p) or TP53 mutation, unmutated IGHV, β2-microglobulin>3.5 mg/L |

The correlation of IGHV mutation status with response to first-line chemoimmunotherapy was evaluated in three rcts30,35,37. All studies reported poorer outcomes, in terms of pfs, for patients with ighv-u. In the gcllsg cll8 study, os values were not reported for the two subgroups, but Kaplan–Meier estimates suggest that os is significantly shorter in patients with ighv-u30. Longer follow-up in those studies and additional investigation of IGHV mutation status in randomized trials are required to determine how this prognostic biomarker should inform decisions about first-line treatment. The influence of β2M and thymidine kinase on response to treatment has not been prospectively evaluated in randomized studies to date and remains to be defined in the setting of current first-line treatments.

To develop an integrated prognostic index, the gcllsg analyzed data from three large phase iii trials that collectively included 1948 patients38; however, of the three trial cohorts analyzed, none included patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy, limiting the adoption of the gcllsg score in the current era of first-line cll treatment. More recently, the cll-ipi (International Prognostic Index) Working Group used pooled data from 3472 patients participating in eight phase iii trials (including the cll8 trial cohort treated with fcr) to develop an integrated prognostic score for patients with cll, identifying 3 biomarkers independently associated with shorter os: β2M concentration greater than 3.5 mg/L, ighv-u, and P53 gene aberrations [del(17p), TP53 mutation, or both]39. Four risk categories with different os rates were identified, providing additional prognostic information about os beyond conventional clinical staging. The cll-ipi has been validated in unselected patient cohorts and in patients enrolled in the gcllsg cll11 randomized trial that evaluated first-line treatment of older patients with comorbidities40–42. One limitation of that study is that, at the time of the analysis, rcts of novel targeted therapies did not have sufficiently long follow-up to be included.

Recommendations

■ Testing for prognostic markers should be performed when therapy is required, but evidence is insufficient to recommend routine prognostic marker testing at diagnosis in asymptomatic patients with early-stage cll. The decision to initiate therapy should be made independently of prognostic marker results, even in the setting of high-risk disease (level of evidence: category 2A).

■ Patients with TP53 abnormalities have a particularly poor prognosis, including significantly reduced pfs and os after standard chemoimmunotherapy, and might benefit from treatment with a novel targeted therapy. The expert panel strongly recommends testing for del(17p) and TP53 mutation before initiation of first-line treatment (level of evidence: category 2A).

■ Because the cll-ipi provides valuable prognostic information, the expert panel recommends testing for IGVH mutation status and β2M concentration (in addition to del(17p) and TP53 mutation) before initiation of first-line therapy (level of evidence: category 2B).

Question 2

What criteria should be used to assess fitness in patients with cll?

Background

The advent of newer therapies has led to a greater focus on evaluating the fitness status of patients with cll. As treatment intensity increases, reliable methods are needed to identify patients who can safely tolerate and benefit from such therapy. Traditionally, fitness was classified based on age alone; it is now well recognized that chronologic age is not a reliable surrogate for physiologic age or fitness43,44. Clinical trials performed in the cll population are difficult to compare, because the indices used to assess fitness are not standardized, leading to heterogeneity in trial populations. In routine clinical practice, clinical judgment remains the standard of care.

The gcllsg has used a combination of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (cirs) and creatinine clearance to define fitness status with respect to tolerability of fcr chemoimmunotherapy45. Although the cirs score establishes a clinically useful division, it has not been externally validated or universally adopted outside of clinical trials.

Summary of Evidence

Few randomized prospective studies of first-line treatment for cll have evaluated the effect of patient fitness on outcomes. Prospective analyses of defined fitness factors in treatment-naïve patients with cll receiving current chemoimmunotherapy regimens is limited to subgroup analyses in two randomized studies and four single-arm prospective studies (supplemental Table 1)31,35,46–51. Two meta-analyses investigating the effect of comorbidity or age on response to first-line treatments were also included (supplemental Table 1). Those studies provide insight into some of the fitness parameters that might influence patient response and tolerability to therapy; however, the evidence is currently insufficient to define an optimal method to assess fitness for patients with cll or to indicate that a fitness score is superior to clinical judgment.

Recommendations

Patient fitness should be considered when choosing therapy for cll patients (level of evidence: category 2B).

No specific fitness assessment tool has been proved optimal for decision-making about cll treatment, but the assessment should focus on organ impairment, particularly renal function (level of evidence: category 3).

Question 3

How should asymptomatic early-stage cll be managed?

Background

Today, almost 80% of cll patients are diagnosed at an early clinical stage52. Considerable interest is therefore invested in determining optimal timing of treatment initiation to achieve the best outcomes for this patient cohort. All current international guidelines recommend initiation of treatment in patients with advanced (Binet C, Rai iii–iv) or active symptomatic disease; however, they recommend that newly diagnosed patients with asymptomatic early-stage disease (Binet A–B, Rai 0–ii) be monitored without therapy unless they have evidence of disease progression4,14,17–20.

Summary of Evidence

No published rcts evaluating early first-line treatment of Binet A–B or Rai 0–ii asymptomatic patients were identified after the year 2000. Studies from the French Cooperative Group on CLL and the Cancer and Leukemia Group B evaluated outcomes of early treatment with chlorambucil in patients with early-stage disease (Table iii). Although disease progression and appearance of symptoms could be delayed with early treatment, the use of alkylating agents did not prolong survival. That result was confirmed by a meta-analysis (Table iii)55. Furthermore, an increased frequency of fatal epithelial cancers in treated compared with untreated patients was reported54.

TABLE III.

Early therapy compared with observation

| Reference | Patient classification | Treatment | Pts (n) | Overall survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-chemoimmunotherapy era | ||||

|

| ||||

| Shustik et al., 198853 | Rai I, II | Observation vs. chlorambucil | 48 | At 5 years: 75 vs. 75, nonsignificant |

|

| ||||

| Dighiero et al., 199854 | Binet A | Observation vs. chlorambucil | 609 | At 10 years: 47 vs. 54, nonsignificant |

| Binet A | Observation vs. chlorambucil–prednisone | 926 | At 7 years: 69 vs. 69, nonsignificant | |

|

| ||||

| CLL Trialists’ Collaborative Group, 199955 | Binet A; Rai I, II | Observation vs. treatment | 2001 | At 10 years: 44 vs. 47, nonsignificant |

|

| ||||

| Chemoimmunotherapy era | ||||

|

| ||||

| Schweighofer et al., 201356 (abstract) | Binet A | Observation vs. fludarabine–cyclophosphamide–rituximab | 183 | At 3.8 years: not reported, nonsignificant |

Table iii also presents results from one abstract examining early treatment with chemoimmunotherapy56. The randomized German–French cooperative phase iii trial analyzed the efficacy of early compared with deferred fcr therapy in treatment-naïve patients with Binet A cll having a high risk of disease progression. Patients with high-risk cll were randomized to receive fcr or to be followed in a “watch and wait” strategy. Patients with low-risk cll were observed only. After a median follow-up of 46 months, event-free survival was significantly improved in patients receiving fcr compared with patients being managed as “watch and wait” (median: not reached vs. 24.5 months; p< 0.0001). However, os was not significantly different in the fcr and “watch and wait” strategy groups, with 181 high-risk patients (90%) being alive at last follow-up.

Currently, a multicentre double-blind placebo- controlled phase iii study, gcllsg cll12 (see NCT02863718 at http://ClinicalTrials.gov/), is underway to compare the efficacy and safety of ibrutinib with a “watch and wait” approach in Binet A cll with risk of disease progression defined by the comprehensive cll score57. Long-term follow-up of those high-risk patients could provide additional insight about outcomes of early treatment in this patient cohort, but the potential benefit of early intervention with cll drug therapy remains to be proven.

Recommendation

■ For asymptomatic patients with early-stage cll who do not meet the indications for therapy established by the International Working Group on CLL guidelines (Table iv), clinical observation only is recommended6 (level of evidence: category 2A).

TABLE IV.

Criteria for initiating therapy: summary of guidelines developed by the International Working Group on CLL6

| 1. Evidence of progressive marrow failure as manifested by the development or worsening of anemia or thrombocytopenia, or both |

| 2. Massive (that is, at least 6 cm below the left costal margin) or progressive or symptomatic splenomegaly |

| 3. Massive nodes (that is, at least 10 cm in longest diameter) or progressive or symptomatic lymphadenopathy |

| 4. Progressive lymphocytosis, with an increase of more than 50% over a 2-month period or a lymphocyte doubling time (LDT) of less than 6 months The LDT can be obtained by linear regression extrapolation of absolute lymphocyte counts obtained at intervals of 2 weeks over an observation period of 2–3 months. In patients with initial blood lymphocyte counts of less than 30×109/L (30,000/μL), the LDT should not be used as a single parameter to define a treatment indication. In addition, factors contributing to lymphocytosis or lymphadenopathy other than chronic lymphocytic leukemia (for example, infections) should be excluded. |

| 5. Autoimmune anemia or thrombocytopenia (or both) that is poorly responsive to corticosteroids or other standard therapy (see section 10.2 of the guideline) |

6. Constitutional symptoms, defined as any one or more of the following disease-related symptoms or signs:

|

Question 4

How should advanced symptomatic cll be managed?

Background

Monotherapy with the alkylating agent chlorambucil (Clb) was the standard-of-care therapy for cll for several decades55. All published international guidelines currently recommend the addition of an anti-CD20 antibody to chemotherapy for the first-line treatment of cll in most patients requiring therapy6,14,17–20. The chemotherapy agents recommended depend on factors such as patient age, functional status, presence of comorbidities, and organ function. For patients with del(17p) or TP53 mutation, recently updated guidelines recommend treatment with the kinase inhibitor ibrutinib14,17–19.

Summary of Evidence

Fit Patients (Without del(17p) or TP53 Mutation)

Purine analogs have replaced Clb as the backbone of first-line chemotherapy for physically fit patients, based on the results of numerous rcts (supplemental Table 2). Fludarabine remains the best-studied purine analog and the one most commonly prescribed for cll. Based on improved os and a 2-year improvement in median pfs, the randomized gcllsg cll8 trial of untreated physically fit patients (cirs score ≤6) established rituximab–fc (compared with fc chemotherapy alone) as the standard of care. Subgroup analysis of prognostic factors showed that the positive effect of fcr was consistent in most prognostic groups and that the benefit of fcr was most pronounced in patients with mutated IGHV 30. However, fcr did not improve the survival of patients with del(17p) or TP53 mutation30–32.

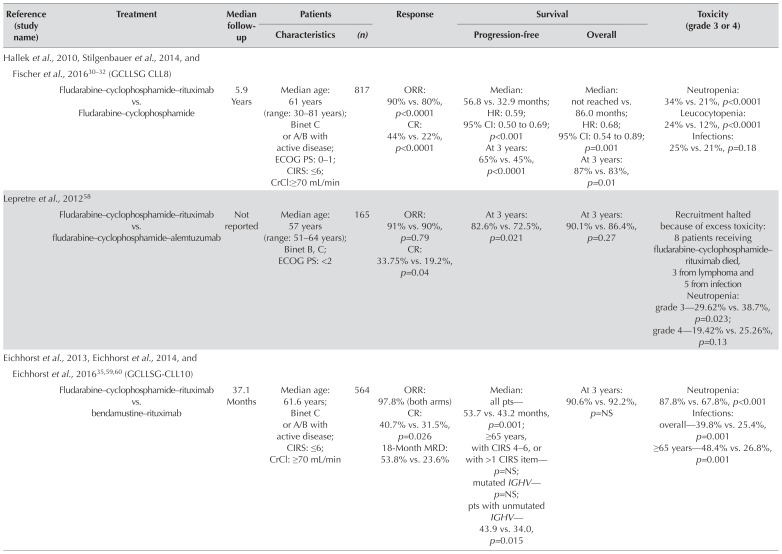

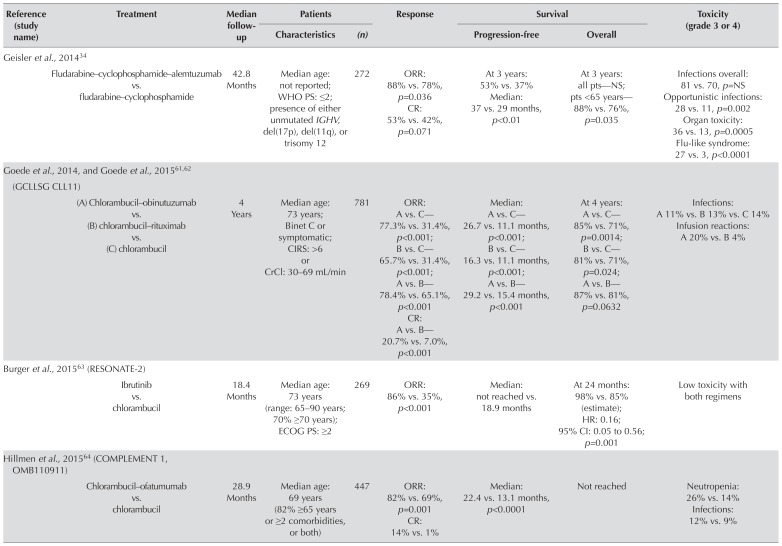

Several phase ii studies have been initiated with the intent of improving the fcr regimen (supplemental Table 3); to date, however, few rcts determining the efficacy of those treatments in comparison with fcr have been reported. Two studies investigated the addition of alemtuzumab to fc, observing greater toxicity related to infections (Table v)34,58. Preliminary results from a randomized phase ii study (Cancer and Leukemia Group B 10404) evaluating fr (fludarabine–rituximab), fr followed by 6 months of lenalidomide consolidation, and fcr in previously untreated patients with cll have recently been reported (Table v) and demonstrated shorter pfs with fr than with fcr66.

TABLE V.

Randomized controlled trials of chemoimmunotherapy and targeted therapies

| Reference (study name) | Treatment | Median follow-up | Patients | Response | Survival | Toxicity (grade 3 or 4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Characteristics | (n) | Progression-free | Overall | |||||

| Hallek et al., 2010, Stilgenbauer et al., 2014, and Fischer et al., 201630–32 (GCLLSG CLL8) | ||||||||

| Fludarabine–cyclophosphamide–rituximab vs. Fludarabine–cyclophosphamide | 5.9 Years | Median age: 61 years (range: 30–81 years); Binet C or A/B with active disease; ECOG PS: 0–1; CIRS: ≤6; CrCl:≥70 mL/min | 817 | ORR: 90% vs. 80%, p<0.0001 CR: 44% vs. 22%, p<0.0001 |

Median: 56.8 vs. 32.9 months; HR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.50 to 0.69; p<0.001 At 3 years: 65% vs. 45%, p<0.0001 |

Median: not reached vs. 86.0 months; HR: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.54 to 0.89; p=0.001 At 3 years: 87% vs. 83%, p=0.01 |

Neutropenia: 34% vs. 21%, p<0.0001 Leucocytopenia: 24% vs. 12%, p<0.0001 Infections: 25% vs. 21%, p=0.18 |

|

|

| ||||||||

| Lepretre et al., 201258 | ||||||||

| Fludarabine–cyclophosphamide–rituximab vs. fludarabine–cyclophosphamide–alemtuzumab | Not reported | Median age: 57 years (range: 51–64 years); Binet B, C; ECOG PS: <2 | 165 | ORR: 91% vs. 90%, p=0.79 CR: 33.75% vs. 19.2%, p=0.04 |

At 3 years: 82.6% vs. 72.5%, p=0.021 | At 3 years: 90.1% vs. 86.4%, p=0.27 | Recruitment halted because of excess toxicity: 8 patients receiving fludarabine–cyclophosphamide–rituximab died, 3 from lymphoma and 5 from infection Neutropenia: grade 3—29.62% vs. 38.7%, p=0.023; grade 4—19.42% vs. 25.26%, p=0.13 |

|

|

| ||||||||

| Eichhorst et al., 2013, Eichhorst et al., 2014, and Eichhorst et al., 201635,59,60 (GCLLSG-CLL10) | ||||||||

| Fludarabine–cyclophosphamide–rituximab vs. bendamustine–rituximab | 37.1 Months | Median age: 61.6 years; Binet C or A/B with active disease; CIRS: ≤6; CrCl: ≥70 mL/min | 564 | ORR: 97.8% (both arms) CR: 40.7% vs. 31.5%, p=0.026 18-Month MRD: 53.8% vs. 23.6% |

Median: all pts—53.7 vs. 43.2 months, p=0.001; ≥65 years, with CIRS 4–6, or with >1 CIRS item—p=NS; mutated IGHV— p=NS; pts with unmutated IGHV—43.9 vs. 34.0, p=0.015 |

At 3 years: 90.6% vs. 92.2%, p=NS | Neutropenia: 87.8% vs. 67.8%, p<0.001 Infections: overall—39.8% vs. 25.4%, p=0.001 ≥65 years—48.4% vs. 26.8%, p=0.001 |

|

|

| ||||||||

| Geisler et al., 201434 | ||||||||

| Fludarabine–cyclophosphamide–alemtuzumab vs. fludarabine–cyclophosphamide | 42.8 Months | Median age: not reported; WHO PS: ≤2; presence of either unmutated IGHV, del(17p), del(11q), or trisomy 12 | 272 | ORR: 88% vs. 78%, p=0.036 CR: 53% vs. 42%, p=0.071 |

At 3 years: 53% vs. 37% Median: 37 vs. 29 months, p<0.01 |

At 3 years: all pts—NS; pts <65 years—88% vs. 76%, p=0.035 | Infections overall: 81 vs. 70, p=NS Opportunistic infections: 28 vs. 11, p=0.002 Organ toxicity: 36 vs. 13, p=0.0005 Flu-like syndrome: 27 vs. 3, p<0.0001 |

|

|

| ||||||||

| Goede et al., 2014, and Goede et al., 201561,62 (GCLLSG CLL11) | ||||||||

| (A) Chlorambucil–obinutuzumab vs. (B) chlorambucil–rituximab vs. (C) chlorambucil | 4 Years | Median age: 73 years; Binet C or symptomatic; CIRS: >6 or CrCl: 30–69 mL/min | 781 | ORR: A vs. C—77.3% vs. 31.4%, p<0.001; B vs. C—65.7% vs. 31.4%, p<0.001; A vs. B—78.4% vs. 65.1%, p<0.001 CR: A vs. B—20.7% vs. 7.0%, p<0.001 |

Median: A vs. C—26.7 vs. 11.1 months, p<0.001; B vs. C—16.3 vs. 11.1 months, p<0.001; A vs. B—29.2 vs. 15.4 months, p<0.001 | At 4 years: A vs. C—85% vs. 71%, p=0.0014; B vs. C—81% vs. 71%, p=0.024; A vs. B—87% vs. 81%, p=0.0632 | Infections: A 11% vs. B 13% vs. C 14% Infusion reactions: A 20% vs. B 4% |

|

|

| ||||||||

| Burger et al., 201563 (RESONATE-2) | ||||||||

| Ibrutinib vs. chlorambucil | 18.4 Months | Median age: 73 years (range: 65–90 years; 70% ≥70 years); ECOG PS: ≥2 | 269 | ORR: 86% vs. 35%, p<0.001 | Median: not reached vs. 18.9 months 95% CI: 0.05 to 0.56; | At 24 months: 98% vs. 85% (estimate); HR: 0.16; p=0.001 | Low toxicity with both regimens | |

|

| ||||||||

| Hillmen et al., 201564 (COMPLEMENT 1, OMB110911) | ||||||||

| Chlorambucil–ofatumumab vs. chlorambucil | 28.9 Months | Median age: 69 years (82% ≥65 years or ≥2 comorbidities, or both) | 447 | ORR: 82% vs. 69%, p=0.001 CR: 14% vs. 1% |

Median: 22.4 vs. 13.1 months, p<0.0001 | Not reached | Neutropenia: 26% vs. 14% Infections: 12% vs. 9% |

|

|

| ||||||||

| Michallet et al., 201565 (MABLE study, abstract) | ||||||||

| Bendamustine–rituximab vs. chlorambucil–rituximab | 24 Months | Ineligible for fludarabine | ORR: 91% vs. 86%, p=0.304 CR: 24% vs. 9%, p=0.002 |

Median: 40 vs. 30 months; HR: 0.523; 95% CI: 0.339 to 0.806; p=0.003 | p=NS | Grade 3: 75% vs. 64% Infections: 19% vs. 10% |

||

| Ruppert et al., 201766 (Alliance Trial, CALGB 10404) | ||||||||

| (A) Fludarabine–cyclophosphamide–rituximab vs. (B) fludarabine–rituximab–lenalidomide vs. (C) fludarabine–rituximab | 24 Months | Not reported | 342 | Not reported | Median: A vs. C—78 vs. 43 months, p<0.01; B vs. C—66 vs. 43 months, | Not reached for any group | Not reported | |

GCLLSG = German CLL Study Group; ECOG PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; CIRS = Cumulative Illness Rating Scale; CrCl = creatinine clearance; ORR = overall response rate; CR = complete response rate; HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; MRD = minimal residual disease; pts = patients; NS = nonsignificant; WHO PS = World Health Organization performance status.

Bendamustine regimens have also been investigated as first-line therapy in prospective trials (Table v and supplemental Table 3)35,51,59,60. In the international randomized phase iii noninferiority study cll10, the gcllsg evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of br (bendamustine–rituximab) compared with fcr for the first-line treatment of fit patients with cll without del(17p) (Table v)35,59,60. Median pfs was significantly longer in the fcr arm. Physically fit subgroups derived the most benefit from fcr therapy, but the difference in pfs between treatment groups was nonsignificant for patients more than 65 years of age and for those with a cirs score of 4–6 or the presence of more than 1 cirs item. After 5 years, no difference in os was observed between the treatment arms; however, during treatment, infections were more frequent with fcr, especially in patients 65 years of age and older.

Less-Fit Patients (Without del(17p) or TP53 Mutation)

The gcllsg cll11 trial investigated Clb in combination with anti-CD20 antibodies in previously untreated patients with cll and comorbidities, demonstrating prolonged pfs and os with the addition of anti-CD20 therapy (Table v)61,62. Compared with ClbR (Clb–rituximab) treatment, treatment with Clb–obinutuzumab resulted in longer pfs and higher rates of complete response.

The international complement 1 study demonstrated similarly improved pfs with a combination of the anti-CD20 antibody ofatumumab and Clb compared with Clb alone; however, at the time of publication, no difference in os had been reported64.

The randomized phase iii mable study evaluated the efficacy and safety of br compared with ClbR in an older less-fit cll population (Table v )65. In previously untreated patients, pfs was longer with br than with ClbR. The magnitude of the benefit (10 months) was relatively modest; however, the Clb dose was considerably higher than in the cll11 trial. Grade 3 adverse events were more common with br than with ClbR, driven by a slightly higher rate of infection.

Inthephaseiiirandomizedresonate-2trial(pcyc-1115), ibrutinib was compared with Clb monotherapy in previously untreated patients with cll for whom fludarabine- based therapy was considered inappropriate63. Compared with Clb, ibrutinib was associated with longer pfs (median: not reached vs. 18.9 months), significantly prolonged os, and an 84% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death. The study has been criticized for its use of Clb monotherapy as a comparator because Clb was not a standard-of-care treatment option at the time of the study.

Patients with del(17p) or TP53 Mutation, or Both

Patients who have del(17p) or TP53 mutation often respond poorly to standard chemotherapy regimens, including fcr30–32. Alemtuzumab, in combination with other agents, has been studied in prospective trials in this high-risk population (Table vi)67,68. The results from those studies suggest that treatment regimens containing alemtuzumab (compared with standard chemoimmunotherapy) might confer a modest improvement in responses for cll with del(17p) or TP53 mutation; however, confirmatory phase iii studies are required to assess the potential benefit of those therapies.

TABLE VI.

Phase II studies in patients with Del(17p) or TP53 mutations

| Reference (study name) | Treatment | Median follow-up | Patients | Response | Survival | Toxicity (grade 3 or 4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Characteristics | (n) | Progression-free | Overall | |||||

| Pettitt et al., 201267 | ||||||||

| Alemtuzumab–prednisone | Not reported | Median age: 61.5 years; TP53 mutation | 17 | ORR: 85% CR: 65% |

Median: 18.3 months | Median: 38.9 months | Neutropenia: 64.1% Thrombocytopenia: 30.8% Anemia: 30.8% Infection (overall): 51.3% Febrile neutropenia: 17.9% |

|

|

| ||||||||

| Mauro et al., 201468 | ||||||||

| Fludarabine–alemtuzumab | Not reported | Age: 60 years; Binet A–C with progressive disease; presence of high-risk genetic features | 45 | ORR: 95% CR: 30% |

At 3 years: 42.5% | At 3 years: 79.9% | Neutropenia: 33% Infection: 11% |

|

|

| ||||||||

| Burger et al., 2015, and Jain et al., 201663,69 | ||||||||

| Ibrutinib–rituximab | 47 Months | Median age: 65 years; del(p17) or TP53 mutation, or both; untreated and previously treated | 40 (previously untreated: 4) | ORR: 95% CR: 23% |

Median: 45 months | Median: not reached (not specified) | Few grade 3 or 4 adverse events | |

|

| ||||||||

| Farooqui et al., 201570 | ||||||||

| Ibrutinib | 24 Months | Median age (previously untreated): 62 years (range: 33–82 years); del(p17) or TP53 mutation, or both; untreated and previously treated | 51 (previously untreated: 35) | ORR: 97%, previously untreated PR: 55%, previously untreated |

At 24 months: all pts—82% (95% CI: 71% to 94%) | At 24 months: previously untreated pts—84% (95% CI: 72% to 100%) | Neutropenia: 24% (no neutropenic fevers) Anemia: 14% Thrombocytopenia: 10% |

|

ORR = overall response rate; CR = complete response; PR = partial response; CI = confidence interval.

Two prospective phase ii trials have reported results for single-agent ibrutinib in previously untreated patients with high-risk cll (Table vi )63,70,71. In one study, 51 patients (35 untreated) with del(17p) or TP53 mutation were treated with ibrutinib, achieving impressive pfs and os results70. Although the experience with ibrutinib as first-line treatment for patients with cll and a del(17p) or TP53 mutation is still limited, current data suggest that this agent might provide durable disease control in treatment-naïve patients with cll having del(17p) or TP53 mutation.

Recommendations

■ For fit younger patients without del(17p) or TP53 mutation, we recommend fcr as the preferred first-line treatment (level of evidence: category 1).

■ For fit elderly patients (more than 65 years of age) without del(17p) or TP53 mutation, br is a reasonable treatment option and could be used in preference to fcr because of lesser toxicity (level of evidence: category2A).

■ For less-fit patients, for whom fludarabine therapy is considered inappropriate, and who do not have del(17p) or TP53 mutation, treatment with Clb–obinutuzumab or with ibrutinib monotherapy is recommended. In the absence of a prospective rct comparing ibrutinib therapy with Clb–obinutuzumab (a current standard chemoimmunotherapeutic option in this population in Canada), it is not possible to determine which regimen is optimal in terms of long-term survival and toxicity (level of evidence: category 1).

■ Patients with del(17p) or TP53 mutation should be offered ibrutinib as first-line treatment because of demonstrated high response rates and potentially long-lasting remissions in this high-risk population (level of evidence: category 2A).

Question 5

In which patients should additional treatment be considered after a response to first-line induction therapy?

Background

Although modern treatment options for cll produce high response rates, almost all patients relapse, likely because of the persistence of minimal residual disease. Treatment strategies aimed at eradicating minimal residual disease after initial therapy could therefore have a favourable effect on outcomes for patients with cll. Consolidation and maintenance therapy is a promising concept that can further improve the quality and duration of response in patients with cll.

Since about 2008, maintenance treatments mainly based on monoclonal antibodies have been explored in chronic B cell malignancies. Rituximab maintenance is now commonly recommended in other B lymphoid diseases such as follicular lymphoma and mantle-cell lymphoma, in which phase iii studies have shown prolonged pfs72–74. High-dose therapy (with or without total-body radiotherapy) with autologous hsct (auto-hsct) is a consolidation strategy that has been investigated in the first-line treatment setting for cll.

Currently, the only potentially curative treatment for cll is allo-hsct. Previously, the rationale for allo-hsct in first remission for del(17p) or TP53-mutated cll was based on the experience that, once the disease recurred after an effective first-line treatment, the likelihood of a second remission was unlikely with available therapies. Although allo-hsct remains a curative treatment option for some patients, it is not routinely recommended for the frontline treatment of cll patients in the current era of effective targeted therapies.

Summary of Evidence

Consolidation or Maintenance Drug Therapy

Two randomized phase iii trials (one published75, one conference abstract76) have compared maintenance therapy with observation after first-line induction with chemoimmunotherapy in cll (supplemental Table 4). Additionally, seven prospective studies evaluating drug consolidation or maintenance strategies after first-line chemoimmunotherapy were identified in the literature search (supplemental Table 5)77–85. Although current evidence indicates that maintenance therapy might prolong pfs in first remission, no study has yet demonstrated an improvement in os, and further randomized trials and long-term follow-up are required to characterize the benefits of rituximab and other agents in maintenance therapy.

Auto-HSCT

One randomized trial with rituximab-based induction chemoimmunotherapy, which compared the combination of high-dose consolidation therapy (hdt) and auto-hsct with rituximab maintenance, was identified (supplemental Table 6)86. The authors reported the outcomes of hdt with auto-hsct and of rituximab maintenance after fcr induction therapy. After a median follow-up of 5 years, no difference in median event-free survival was observed between the two arms (65.1 months for hdt with auto-hsct and 60.4 months for rituximab maintenance), and hdt with auto-hsct did not result in an improved rate of os (88.1% for hdt with auto-hsct and 88% for rituximab maintenance).

Allo-HSCT

No prospective studies comparing allo-hsct with non-transplantation strategies during remission after first-line cll treatment were identified in the literature search. Although allo-hsct has curative potential, this treatment option has additional limitations related to age, comorbidity, and donor availability.

Recommendations

■ No current high-quality evidence supports the use of maintenance therapy in patients with cll after first-line therapy (level of evidence: category 2A).

■ Given the lack of a survival benefit, we do not recommend hdt with auto-hsct in its current form as a consolidative approach after first-line therapy (level of evidence: category 2A).

■ Allo-hsct is not currently recommended as part of first-line therapy for cll (level of evidence: category 2B).

Supplemental Materials

Footnotes

Supplemental material available at http://www.current-oncology.com

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare the following interests: CO reports personal fees from Roche, Janssen, Gilead, AbbVie, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Lundbeck/Teva outside the submitted work; VB sits on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Janssen, Lundbeck, Gilead, Roche, and has received grants from Research Manitoba, the CancerCare Manitoba Foundation, and Lundbeck outside the submitted work; ASG reports personal fees from Janssen, Lundbeck, and AbbVie outside the submitted work; SA reports personal fees from Roche and Pfizer outside the submitted work; CC reports other considerations from Celgene, Janssen, and Gilead outside the submitted work; KSR reports personal fees from Celgene, Janssen, Gilead, Roche, AstraZeneca, and AbbVie outside the submitted work; EL reports grants from Roche, Gilead, and Lundbeck during the conduct of the study; GF reports grants and personal fees from Celgene and AbbVie, and personal fees from Janssen outside the submitted work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rozman C, Montserrat E. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1052–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510193331606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States, Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (nci), Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Leukemia – Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) [Web page] Bethesda, MD: NCI; n.d. [Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/clyl.html; cited 20 September 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallek M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:446–60. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Statistics Canada. Number and rates of new cases of primary cancer (based on the November 2017 CCR tabulation file), by cancer type, age group and sex [Web resource] Ottawa ON: Government of Canada; 2017. Table 13-10-0111-01. [Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310011101; cited 25 March 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. on behalf of the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute–Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111:5446–56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutton LA, Rosenquist R. Deciphering the molecular landscape in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: time frame of disease evolution. Haematologica. 2015;100:7–16. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.115923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang S, Kipps TJ. The pathogenesis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:103–18. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-163955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burger JA, Gribben JG. The microenvironment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (cll) and other B cell malignancies: insight into disease biology and new targeted therapies. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;24:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Binet JL, Auquier A, Dighiero G, et al. A new prognostic classification of chronic lymphocytic leukemia derived from a multivariate survival analysis. Cancer. 1981;48:198–206. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810701)48:1<198::AID-CNCR2820480131>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gale RP, Rai KR. A critical analysis of staging in cll. In: Gale RP, Rai KR, editors. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Recent Progress and Future Directions. New York, NY: Alan R. Liss; 1987. pp. 253–64. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rai KR, Sawitsky A, Cronkite EP, Chanana AD, Levy RN, Pasternack BS. Clinical staging of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1975;46:219–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-737650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eichhorst BF, Fischer K, Fink AM, et al. on behalf of the German cll Study Group. Limited clinical relevance of imaging techniques in the follow-up of patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results of a meta-analysis. Blood. 2011;117:1817–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-282228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Society for Medical Oncology (esmo), Guidelines Committee. eUpdate– Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Treatment Recommendations [Web page] Lugano, Switzerland: ESMO; 2017. [Available at: https://www.esmo.org/Guidelines/Haematological-Malignancies/Chronic-Lymphocytic-Leukaemia/eUpdate-Treatment-Recommendations; cited 12 November 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wall S, Woyach JA. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other lymphoproliferative disorders. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32:175–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alberta Health Services (ahs) Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Edmonton, AB: AHS; 2017. (Clinical practice guideline LYHE-007. Ver. 4). [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (nccn) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma. Ver. 2.2018. Fort Washington PA: NCCN; 2017. [Current version available online at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cll.pdf (free registration required); cited 3March 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oscier D, Dearden C, Eren E, et al. on behalf of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the diagnosis, investigation and management of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2012;159:541–64. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12067. [Errata in: Br J Haematol 2013;160:868 (dosage error in article text); Br J Haematol 2013;161:154] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wendtner CM, Dreger P, Gregor M, et al. Chronische Lymphatische Leukämie (CLL) [Web page, German] Berlin, Germany: German Society for Hematology and Medical Oncology; 2017. [Available at: https://www.onkopedia-guidelines.info/en/onkopedia/guidelines/chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia-cll/@@view/html/index.html cited 12 January 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mauro FR, Bandini G, Barosi G, et al. on behalf of the Italian Society of Hematology, the Società Italiana di Ematologia Sperimentale, and the Gruppo Italiano Trapianto di Midollo Osseo. sie, sies, gitmo updated clinical recommendations for the management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2012;36:459–66. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prica A, Baldassarre F, Hicks LK, Imrie K, Kouroukis T, Cheung M on behalf of members of the Hematology Disease Site Group of the Cancer Care Ontario Program in Evidence-Based Care. Rituximab in lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a practice guideline. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2017;29:e13–28. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.BC Cancer. Health Professionals Info > Cancer Management Guidelines > Lymphoma, Chronic Leukemia, Myeloma >Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) [Web page] Vancouver, BC: BC Cancer; 2012. [Available at: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/health-professionals/clinical-resources/cancer-management-guidelines/lymphoma-chronic-leukemia-myeloma/chronic-leukemia#Chronic-Lymphocytic-Leukemia-CLL; cited 6 January 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CancerCare Manitoba, Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Clinic. Practice Guideline: Disease Management Consensus Recommendations for the Management of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Winnipeg, MB: CancerCare Manitoba; 2015. [Available online at: https://www.cancercare.mb.ca/export/sites/default/For-Health-Professionals/.galleries/files/treatment-guidelines-rro-files/practice-guidelines/lymphoproliferative-disorders/DM_LYMP-Consensus_Recommendations_for_Mgmt_Chronic_Lymphocytic_Leukemia_2016-06-03.pdf; cited 5 January 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (nccn) NCCN Categories of Evidence and Consensus [Web page] Fort Washington, PA: NCCN; n.d. [Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/categories_of_consensus.asp; cited 20 November 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cramer P, Hallek M. Prognostic factors in chronic lymphocytic leukemia—what do we need to know? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:38–47. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byrd JC, Peterson BL, Morrison VA, et al. Randomized phase 2 study of fludarabine with concurrent versus sequential treatment with rituximab in symptomatic, untreated patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9712 (calgb 9712) Blood. 2003;101:6–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine and rituximab produces extended overall survival and progression-free survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: long-term follow-up of calgb study 9712. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1349–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eichhorst BF, Busch R, Stilgenbauer S, et al. on behalf of the German cll Study Group. First-line therapy with fludarabine compared with chlorambucil does not result in a major benefit for elderly patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:3382–91. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robak T, Jamroziak K, Gora-Tybor J, et al. Comparison of cladribine plus cyclophosphamide with fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide as first-line therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a phase iii randomized study by the Polish Adult Leukemia Group (palg-cll3 study) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1863–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer K, Bahlo J, Fink AM, et al. Long-term remissions after fcr chemoimmunotherapy in previously untreated patients with cll: updated results of the cll8 trial. Blood. 2016;127:208–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-651125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. on behalf of the International Group of Investigators and the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Study Group. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1164–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stilgenbauer S, Schnaiter A, Paschka P, et al. Gene mutations and treatment outcome in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from the cll8 trial. Blood. 2014;123:3247–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-546150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oscier D, Wade R, Davis Z, et al. on behalf of the Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Working Group and the UK National Cancer Research Institute. Prognostic factors identified three risk groups in the lrf cll4 trial, independent of treatment allocation. Haematologica. 2010;95:1705–12. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.025338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geisler CH, van T‘ Veer MB, Jurlander J, et al. Frontline low-dose alemtuzumab with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide prolongs progression-free survival in high-risk cll. Blood. 2014;123:3255–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-547737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eichhorst B, Fink AM, Bahlo J, et al. on behalf of the International Group of Investigators and the German cll Study Group. First-line chemoimmunotherapy with bendamustine and rituximab versus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (cll10): an international, open-label, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:928–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Estenfelder S, Tausch E, Robrecht S, et al. Gene mutations and treatment outcome in the context of chlorambucil (Clb) without or with the addition of rituximab (r) or obinutuzumab (GA-101, G)—results of an extensive analysis of the phase iii study cll11 of the German CLL Study Group [abstract] Blood. 2016;128:3227. [Available online at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/128/22/3227; cited 12 September 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herling CD, Klaumunzer M, Rocha CK, et al. Complex karyotypes and KRAS and POT1 mutations impact outcome in cll after chlorambucil-based chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy. Blood. 2016;128:395–404. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-691550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pflug N, Bahlo J, Shanafelt TD, et al. Development of a comprehensive prognostic index for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014;124:49–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-556399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.International cll-ipi working group. An international prognostic index for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (cll-ipi): a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:779–90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gentile M, Shanafelt TD, Rossi D, et al. Validation of the cll-ipi and comparison with the mdacc prognostic index in newly diagnosed patients. Blood. 2016;128:2093–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-07-728261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.da Cunha-Bang C, Christiansen I, Niemann CU. The cll-ipi applied in a population-based cohort. Blood. 2016;128:2181–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-07-724740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goede V, Bahlo J, Kutsch N, et al. Evaluation of the International Prognostic Index for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (cll-ipi) in elderly patients with comorbidities: analysis of the cll11 study population. Blood. 2016;128:4401. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shanafelt T. Treatment of older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: key questions and current answers. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:158–67. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balducci L. esh-siog international conference on haematological malignancies in the elderly. Expert Rev Hematol. 2010;3:675–7. doi: 10.1586/ehm.10.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goede V, Hallek M. Optimal pharmacotherapeutic management of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: considerations in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:163–76. doi: 10.2165/11587650-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keating MJ, O’Brien S, Albitar M, et al. Early results of a chemoimmunotherapy regimen of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as initial therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4079–88. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tam CS, O’Brien S, Wierda W, et al. Long-term results of the fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab regimen as initial therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;112:975–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martell RE, Peterson BL, Cohen HJ, et al. Analysis of age, estimated creatinine clearance and pretreatment hematologic parameters as predictors of fludarabine toxicity in patients treated for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a calgb (9011) coordinated Intergroup study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2002;50:37–45. doi: 10.1007/s00280-002-0443-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kay NE, Geyer SM, Call TG, et al. Combination chemoimmunotherapy with pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab shows significant clinical activity with low accompanying toxicity in previously untreated B chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:405–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-033274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shanafelt TD, Lin T, Geyer SM, et al. Pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab regimen in older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2007;109:2291–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fischer K, Cramer P, Busch R, et al. Bendamustine in combination with rituximab for previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multicenter phase ii trial of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3209–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baliakas P, Hadzidimitriou A, Sutton LA, et al. on behalf of the European Research Initiative on CLL (eric) Recurrent mutations refine prognosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2015;29:329–36. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shustik C, Mick R, Silver R, Sawitsky A, Rai K, Shapiro L. Treatment of early chronic lymphocytic leukemia: intermittent chlorambucil versus observation. Hematol Oncol. 1988;6:7–12. doi: 10.1002/hon.2900060103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dighiero G, Maloum K, Desablens B, et al. Chlorambucil in indolent chronic lymphocytic leukemia. French Cooperative Group on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1506–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805213382104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chemotherapeutic options in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a meta-analysis of the randomized trials. cll Trialists’ Collaborative Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:861–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.10.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schweighofer CD, Cymbalista F, Müller C, et al. Early versus deferred treatment with combined fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (fcr) improves event-free survival in patients with high-risk Binet stage A chronic lymphocytic leukemia—first results of a randomized German–French Cooperative phaseiii trial. Blood. 2013;122:524. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Langerbeins P, Bahlo J, Rhein C, et al. The cll12 trial protocol: a placebo-controlled double-blind phase iii study of ibrutinib in the treatment of early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with risk of early disease progression. Future Oncol. 2015;11:1895–903. doi: 10.2217/fon.15.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lepretre S, Aurran T, Mahe B, et al. Excess mortality after treatment with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in combination with alemtuzumab in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in a randomized phase 3 trial. Blood. 2012;119:5104–10. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-365437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eichhorst B, Fink AM, Busch R, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine (f), cyclophosphamide (c), and rituximab (r) (fcr) versus bendamustine and rituximab (br) in previously untreated and physically fit patients (pts) with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia (cll): results of a planned interim analysis of the cll10 trial, an international, randomized study of the German CLL Study Group (gcllsg) Blood. 2013;122:526. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eichhorst B, Fink AM, Busch R, et al. Frontline chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine (f), cyclophosphamide (c), and rituximab (r) (fcr) shows superior efficacy in comparison to bendamustine (b) and rituximab (br) in previously untreated and physically fit patients (pts) with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia (cll): final analysis of an international, randomized study of the German cll Study Group (gcllsg) (cll10 study) Blood. 2014;124:19. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with cll and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1101–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goede V, Fischer K, Engelke A, et al. Obinutuzumab as front-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: updated results of the cll11 study. Leukemia. 2015;29:1602–4. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2425–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hillmen P, Robak T, Janssens A, et al. Chlorambucil plus ofatumumab versus chlorambucil alone in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (complement 1): a randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1873–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Michallet AS, Aktan M, Hiddemann W, et al. Rituximab plus bendamustine or chlorambucil for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: primary analysis of the randomized, open-label mable study. Haematologica. 2018;103:698–706. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.170480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruppert AS, Byrd JC, Heerema NA, et al. A genetic risk- stratified, randomized phase 2 Intergroup study of fludarabine/antibody combinations in symptomatic, untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (cll): results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (calgb) 10404 (Alliance) [abstract 7503] J Clin Oncol. 2017;35 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.7503. [Available online at: http://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.7503; cited 9 September 2018] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pettitt AR, Jackson R, Carruthers S, et al. Alemtuzumab in combination with methylprednisolone is a highly effective induction regimen for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and deletion of TP53: final results of the National Cancer Research Institute cll206 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1647–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.9695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mauro FR, Molica S, Laurenti L, et al. on behalf of the Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto Working Party for Chronic Lymphoproliferative Disorders. Fludarabine plus alemtuzumab (fa) front-line treatment in young patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (cll) and an adverse biologic profile. Leuk Res. 2014;38:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jain P, Keating MJ, Wierda WG, et al. Long-term follow-up of treatment with ibrutinib and rituximab in patients with high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:2154–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Farooqui MZ, Valdez J, Martyr S, et al. Ibrutinib for previously untreated and relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with TP53 aberrations: a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:169–76. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71182-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O’Brien S, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma: an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:48–58. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70513-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Forstpointner R, Unterhalt M, Dreyling M, et al. on behalf of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Maintenance therapy with rituximab leads to a significant prolongation of response duration after salvage therapy with a combination of rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (r-fcm) in patients with recurring and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (glsg) Blood. 2006;108:4003–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Salles G, Seymour JF, Offner F, et al. Rituximab maintenance for 2 years in patients with high tumour burden follicular lymphoma responding to rituximab plus chemotherapy (prima): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:42–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hochster H, Weller E, Gascoyne RD, et al. Maintenance rituximab after cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone prolongs progression-free survival in advanced indolent lymphoma: results of the randomized phase iii ecog 1496 study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1607–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Greil R, Obrtlikova P, Smolej L, et al. Rituximab maintenance versus observation alone in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia who respond to first-line or second-line rituximab-containing chemoimmunotherapy: final results of the agmt cll-8a Maintenance randomised trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3:e317–29. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30045-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dartigeas C, Van Den Neste E, Maisonneuve H, et al. Rituximab maintenance after induction with abbreviated fcr in previously untreated elderly ( 65 years) cll patients: results of the randomized cll 2007 sa trial from the French filo Group ( NCT00645606). [abstract 7505] J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 15) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.7505. [Available online at: http://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.7505; cited 12 September 2018] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bosch F, Abrisqueta P, Villamor N, et al. Rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone: a new, highly active chemoimmunotherapy regimen for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4578–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abrisqueta P, Villamor N, Terol MJ, et al. Rituximab maintenance after first-line therapy with rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (r-fcm) for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2013;122:3951–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-502773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Del Poeta G, Del Principe MI, Buccisano F, et al. Consolidation and maintenance immunotherapy with rituximab improve clinical outcome in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2008;112:119–28. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Foa R, Del Giudice I, Cuneo A, et al. Chlorambucil plus rituximab with or without maintenance rituximab as first-line treatment for elderly chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:480–6. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hainsworth JD, Vazquez ER, Spigel DR, et al. Combination therapy with fludarabine and rituximab followed by alemtuzumab in the first-line treatment of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma: a phase 2 trial of the Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network. Cancer. 2008;112:1288–95. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jones JA, Ruppert AS, Zhao W, et al. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia with high-risk genomic features have inferior outcome on successive Cancer and Leukemia Group B trials with alemtuzumab consolidation: subgroup analysis from calgb 19901 and calgb 10101. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:2654–9. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.788179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lin TS, Donohue KA, Byrd JC, et al. Consolidation therapy with subcutaneous alemtuzumab after fludarabine and rituximab induction therapy for previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: final analysis of calgb 10101. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4500–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Strati P, Lanasa M, Call TG, et al. Ofatumumab monotherapy as a consolidation strategy in patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3:e407–14. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shanafelt TD, Ramsay AG, Zent CS, et al. Long-term repair of T-cell synapse activity in a phase ii trial of chemoimmunotherapy followed by lenalidomide consolidation in previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (cll) Blood. 2013;121:4137–41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-470005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Magni M, Nicola MD, Patti C, et al. Results of a randomized trial comparing high-dose chemotherapy plus auto-sct and r-fc in cll at diagnosis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:485–91. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.