Abstract

Background

The French Society of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine and the French Society of Intensive Care edited guidelines focused on hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) in intensive care unit. The goal of 16 French-speaking experts was to produce a framework enabling an easier decision-making process for intensivists.

Results

The guidelines were related to 3 specific areas related to HAP (prevention, diagnosis and treatment) in 4 identified patient populations (COPD, neutropenia, post-operative and paediatric). The literature analysis and the formulation of the guidelines were conducted according to the Grade of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation methodology. An extensive literature research over the last 10 years was conducted based on publications indexed in PubMed™ and Cochrane™ databases.

Conclusions

HAP should be prevented by a standardised multimodal approach and the use of selective digestive decontamination in units where multidrug-resistant bacteria prevalence was below 20%. Diagnosis relies on clinical assessment and microbiological findings. Monotherapy, in the absence of risk factors for multidrug-resistant bacteria, non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli and/or increased mortality (septic shock, organ failure), is strongly recommended. After microbiological documentation, it is recommended to reduce the spectrum and to prefer monotherapy for the antibiotic therapy of HAP, including for non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli.

Introduction

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is the most common infection in the intensive care unit (ICU) [1]. In the ICU, HAP is associated with a mortality rate of 20% and with increased duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU and hospital length-of-stay [2, 3]. The criteria to diagnose pneumonia are shown in Table 1 (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Criteria for defining pneumonia

| Radiological signs |

| Two successive chest radiographs showing new or progressive lung infiltrates In the absence of medical history of underlying heart or lung disease, a single chest radiograph is enough |

| And at least one of the following signs |

| Body temperature > 38,3 °C without any other cause Leucocytes < 4000/mm3 or ≥ 12,000/mm3 |

| And at least two of the following signs |

| Purulent sputum Cough or dyspnoea Declining oxygenation or increased oxygen requirement or need for respiratory assistance |

Fig. 1.

Multimodal healthcare associated pneumonia prevention protocol (expert opinion)

Method

Sixteen French-speaking experts produce guidelines in three specific areas related to HAP: prevention, diagnosis and treatment as well as the specificities pertaining to different identified patient populations (COPD, neutropenia, post-operative and paediatric). The schedule of the group was defined upstream (Table 2) (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Guideline timeline

| 5 December 2016 | Start-up meeting |

| 6 March 2017 | Vote: first round |

| 13 March 2017 | Post-vote deliberation meeting |

| 1 April 2017 | Vote: second round |

| 16 April 2017 | Amendment of two guidelines |

| 28 April 2017 | Vote of the two amended guidelines |

| 10 May 2017 | Guideline finalisation meeting |

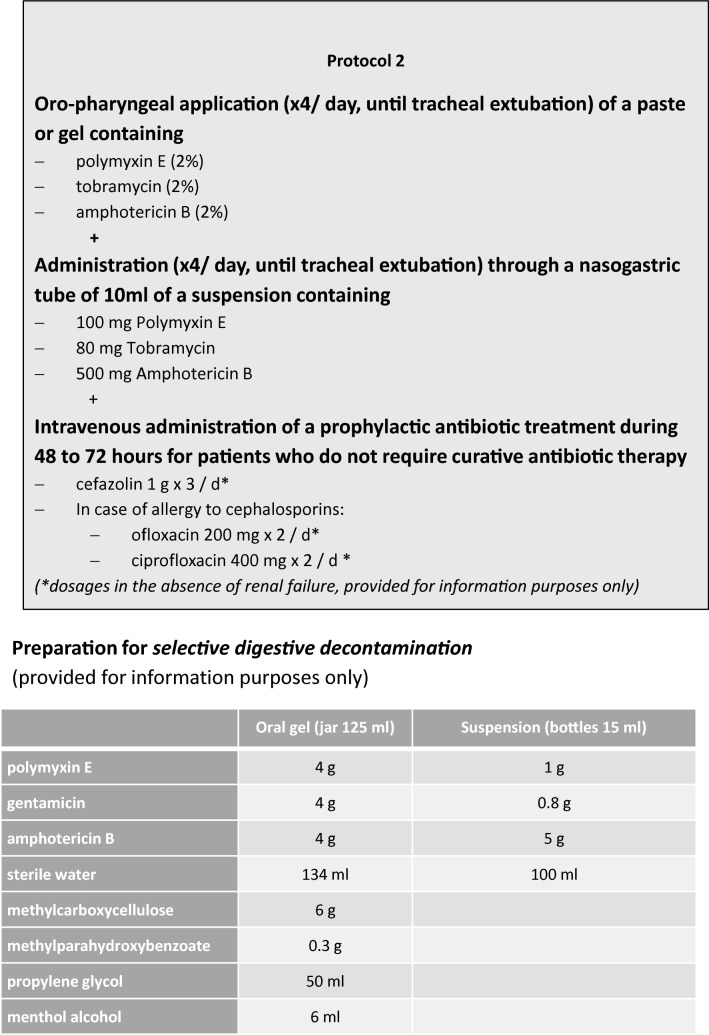

Fig. 2.

Selective digestive decontamination protocol (expert opinion)

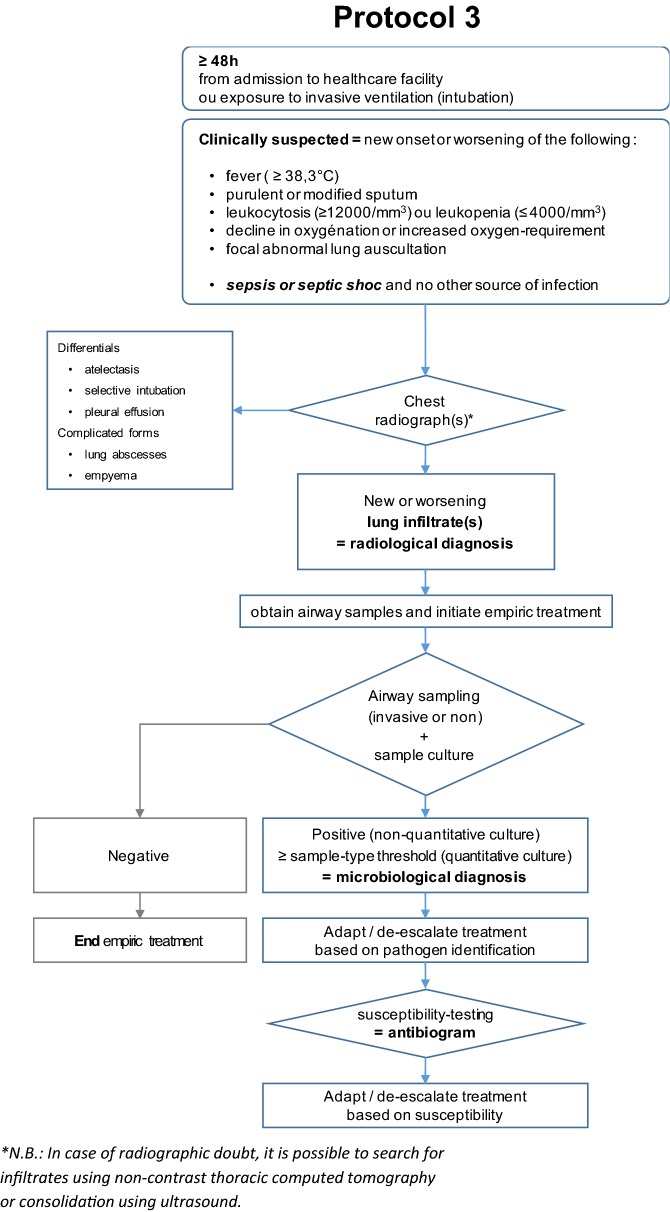

The questions were formulated according to the PICO (Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) format. The formulation of the guidelines was conducted according to the GRADE methodology (Grade of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation) [4, 5]. In the absence of supporting literature, a question could be addressed by a recommendation under the form of an expert opinion (“the experts suggest that…”) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Diagnostic procedure (expert opinion)

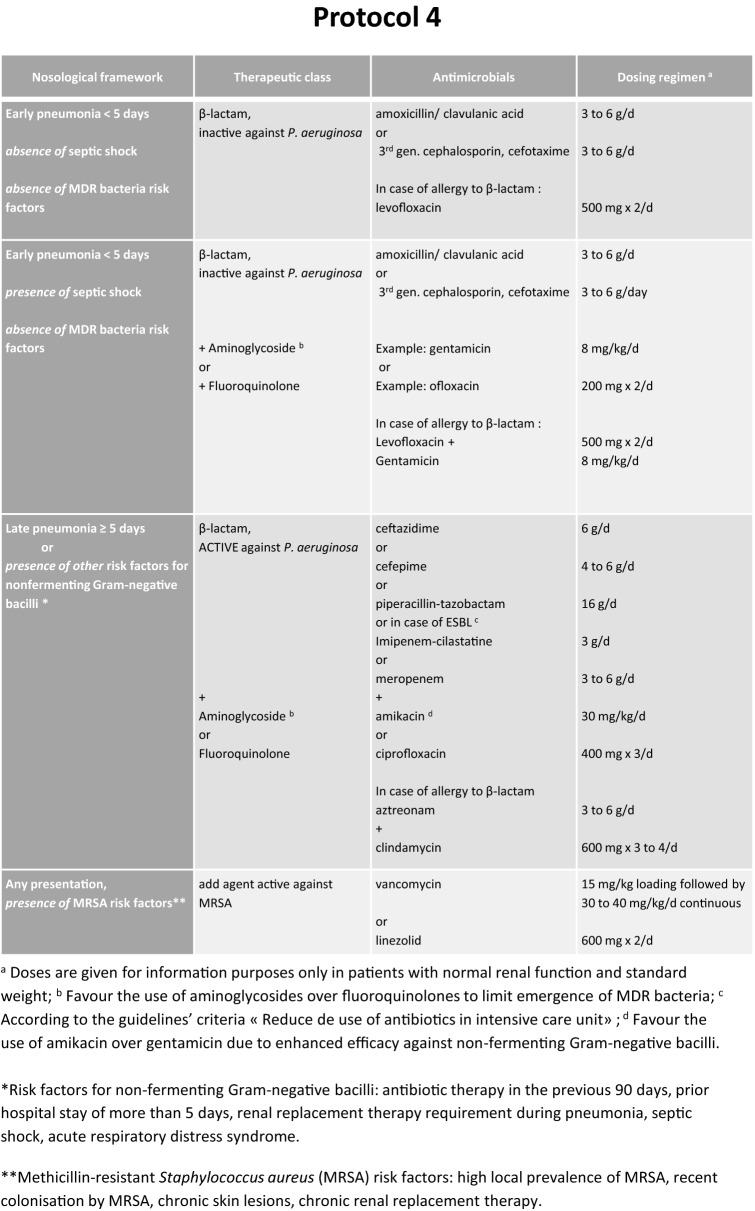

These guidelines with their arguments were published in the journal Anaesthesia Critical Care and Pain Medicine [6] (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Treatment options (expert opinion)

First area, PREVENTION Which HAP prevention approaches decrease morbidity and mortality in ICU patients?

-

R1.1

We recommend using a standardised multimodal HAP prevention approach in order to decrease ICU patient morbidity (Grade 1+).

-

R1.1 Paediatrics

We suggest using a standardised multimodal approach aiming at preventing HAP in order to decrease paediatric ICU patient morbidity (Grade 2+).

-

R1.2

In units where multidrug-resistant bacteria prevalence is low (< 20%), we suggest applying routine selective digestive decontamination using a topical antiseptic administered enterally and a maximal 5-day course of systemic prophylactic antibiotic to decrease mortality (Grade 2+).

-

R1.3Within a standardised multimodal HAP prevention approach, we suggest combining some of the following methods to decrease ICU patient morbidity:

- Promote the use of non-invasive ventilation to avoid tracheal intubation (mainly in post-operative digestive surgery patients and in patients with COPD),

- Favour orotracheal over nasotracheal intubation when required

- Limit dose and duration of sedatives and analgesics (promote their use guided by sedation/pain/agitation scales, and/or daily interruptions),

- Initiate early enteral feeding (within the first 48 h of ICU admission),

- Regularly verify endotracheal tube cuff pressure,

- Perform sub-glottic suction (every 6 to 8 h) using an appropriate endotracheal tube (Grade 2+).

-

R1.4Within a standardised multimodal HAP prevention approach, we suggest not using the following methods to decrease ICU patient morbidity:

- Systematic early (< day 7) tracheotomy (except for specific indications),

- Anti-ulcer prophylaxis (except for specific indications),

- Post-pyloric enteral feeding (except for specific indications),

- Administration of probiotics and/or synbiotics,

- Early systematic change of the humidifier filter (except for specific manufacturer recommendations)

- Use of closed suctioning systems for endotracheal secretions,

- Use of antiseptic-coated intubation tubes or with tubes an “optimised” cuff shape,

- Selective oropharyngeal decontamination (SOD) with povidone-iodine,

- Use of prophylactic nebulised antibiotics,

- Daily skin decontamination using antiseptics (Grade 2−).

-

R1.5

In weaning of COPD patients from ventilation, we suggest using non-invasive ventilation to reduce length of invasive mechanical ventilation, incidence of HAP, morbidity and mortality (Grade 2+).

Second area, DIAGNOSIS What methods to diagnose HAP should be used to decrease ICU patient morbidity and mortality?

-

R2.1

We suggest not using the clinical scores (CPIS, modified CPIS) for diagnosing HAP (Grade 2−).

-

R2.2

We suggest collecting microbiological airway samples, regardless of type, before initiation of any change in antibiotic therapy (Grade 2+).

-

R2.2 Paediatrics

We suggest collecting microbiological airway samples, regardless of type, before initiation of any change in antibiotic therapy (Grade 2+).

-

R2.3

We suggest not measuring plasma or alveolar levels of procalcitonin or soluble TREM-1 to diagnose HAP (Grade 2−).

Third area, TREATMENT What therapeutic options for HAP should be used to decrease ICU patient morbidity and mortality?

-

R3.1

We suggest immediately collecting samples and initiating antibiotic treatment taking into consideration risk factors for multidrug-resistant bacteria in patients with suspected HAP and haemodynamic or respiratory compromise (shock or acute respiratory distress syndrome) or frailty such as immunosuppression [95–100] (Grade 2+).

-

R3.2

We recommend treating HAP in mechanically ventilated immunocompetent patients empirically by a monotherapy, in the absence of risk factors for multidrug-resistant bacteria, non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli and/or increased mortality (septic shock, organ failure) [101–113] (Grade 1+).

-

R3.3

The experts suggest not systematically directing empiric antibiotic therapy against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the treatment of HAP [114–119] (Experts Opinion).

-

R3.4

We suggest reducing the spectrum and preferring monotherapy for the antibiotic therapy of HAP after microbiological documentation, including for non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli [114,115, 120–128] (Grade 2+).

-

R3.5

We recommend not prolonging for more than 7 days the antibiotic treatment for HAP, including for non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli, apart from specific situations (immunosuppression, empyema, necrotising or abscessed pneumonia) [129–135] (Grade 1−).

-

R3.6

We suggest administering nebulised colimycine (sodium colistiméthate) and/or aminoglycosides in documented HAP due multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli documented pneumonia established as sensitive to colimycin and/or aminoglycoside, when no other antibiotics can be used (based on the results of susceptibility testing) [136–152] (Grade 2+).

-

R3.7

We recommend not administering statins as adjuvant treatment for HAP [153–161] (Grade 1−).

Authors’ contributions

Marc Leone and Lila Bouadma proposed the elaboration of this recommendation and manuscript in agreement with the “Société Française d’Anesthésie et de Réanimation” and the “Société de Réanimation de Langue Française”; Gérald Chanques, Rémi Bruyère and Lionel Velly wrote the methodology section and gave the final version with the final presentation. Antoine Roquilly, Charles-Edouard Luyt and Jean-Ralph Zahar contributed to elaborate recommendations and write the rationale of question 1 (prevention). Sébastien Gibot, Bélaïd Bouhemad, Jérome Pugin and Eric Kipnis contributed to elaborate recommendations and to write the rationale of question 2 (diagnosis). Antoine Monsel, Sami Hraiech and Boris Jung contributed to elaborate recommendations and to write the rationale of question 3 (treatment). Djamel Mokart contributed to elaborate recommendations and to write the rationale about neutropenic patients. Saad Nseir contributed to elaborate recommendations and to write the rationale about COPD patients. Olivier Brissaud, Stéphane Dauger and Fabrice Michel contributed to elaborate paediatrics recommendations and to write the rationale of paediatrics issues. Antoine Launey and Dimitri Margetis provide references. Marc Leone and Lila Bouadma drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Guidelines reviewed and endorsed by the SFAR (29/06/2017) and SRLF boards (08/06/2017).

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: Sébastien Gibot: Inotrem S.A, Eric Kipnis: Astellas; LFB; Pfizer, Marc Leone: MSD; Basilea, Charles-Edouard Luyt: Bayer Healthcare; Thermo Fisher BRAHMS; MSD; Biomerieux, Djamel Mokart: Gilead; Basilea; MSD, Philippe Montravers: Pfizer; MSD; Basilea; AstraZeneca; Bayer; Menari; Parexel; Cubist, Saad Nseir: Medtronic; Cielmedical; Bayer, Jérôme Pugin: Bayer; part of the scientific committee for the Amikacin Inhale study, Jean-Ralph Zahar: MSD; Bard. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Société Française d’Anesthésie et de Réanimation (SFAR) and the Société de Réanimation de Langue Française (SRLF).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marc Leone, Email: Marc.LEONE@ap-hm.fr.

Lila Bouadma, Email: lila.bouadma@aphp.fr.

Bélaïd Bouhemad, Email: belaid_bouhemad@hotmail.com.

Olivier Brissaud, Email: olivier.brissaud@chu-bordeaux.fr.

Stéphane Dauger, Email: stephane.dauger@aphp.fr.

Sébastien Gibot, Email: sgibot@yahoo.fr.

Sami Hraiech, Email: Sami.HRAIECH@ap-hm.fr.

Boris Jung, Email: b-jung@chu-montpellier.fr.

Eric Kipnis, Email: ekipnis@gmail.com.

Yoann Launey, Email: yoann.launey@gmail.com.

Charles-Edouard Luyt, Email: charles-edouard.luyt@aphp.fr.

Dimitri Margetis, Email: dimargetis@free.fr.

Fabrice Michel, Email: fabmi13@gmail.com.

Djamel Mokart, Email: mokartd@ipc.unicancer.fr.

Philippe Montravers, Email: philippe.montravers@aphp.fr.

Antoine Monsel, Email: antoine.monsel@aphp.fr.

Saad Nseir, Email: Saadalla.NSEIR@CHRU-LILLE.FR.

Jérôme Pugin, Email: jerome.pugin@unige.ch.

Antoine Roquilly, Email: antoine.roquilly@chu-nantes.fr.

Lionel Velly, Email: LionelJean.VELLY@ap-hm.fr.

Jean-Ralph Zahar, Email: jrzahar@gmail.com.

Rémi Bruyère, Email: rbruyere@ch-bourg01.fr.

Gérald Chanques, Email: g-chanques@chu-montpellier.fr.

ADARPEF:

GFRUP:

References

- 1.Koulenti D, Tsigou E, Rello J. Nosocomial pneumonia in 27 ICUs in Europe: perspectives from the EU-VAP/CAP study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;36:1999. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2703-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuliano KK, Baker D, Quinn B. The epidemiology of nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2017;46:322. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melsen WG, Rovers MM, Groenwold RH, Bergmans DC, Camus C, Bauer TT, Hanisch EW, Klarin B, Koeman M, Krueger WA, Lacherade JC, Lorente L, Memish ZA, Morrow LE, Nardi G, van Nieuwenhoven CA, O’Keefe GE, Nakos G, Scannapieco FA, Seguin P, Staudinger T, Topeli A, Ferrer M, Bonten MJ. Attributable mortality of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised prevention studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(8):665–671. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leone M, Bouadma L, Bouhemad B, Brissaud O, Dauger S, Gibot S, Hraiech S, Jung B, Kipnis E, Launey Y, Luyt CE, Margetis D, Michel F, Mokart D, Montravers P, Monsel A, Nseir S, Pugin J, Roquilly A, Velly L, Zahar JR, Bruyère R, Chanques G. Hospital-acquired pneumonia in ICU. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2018;37(1):83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.