Abstract

Efficient drug accumulation in tumor is essential for chemotherapy. We developed redox-responsive diselenide-based high-loading prodrug nanoparticles (NPs) for targeted triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) treatment.

Method: Redox-responsive diselenide bond (Se-Se) containing dimeric prodrug (PTXD-Se) was synthesized and co-precipitated with TNBC-targeting amphiphilic copolymers to form ultra-stable NPs (uPA-PTXD NPs). The drug loading capacity and redox-responsive drug release behavior were studied. TNBC targeting effect and anti-tumor effect were also evaluated in vitro and in vivo.

Results: On-demand designed paclitaxel dimeric prodrug could co-precipitate with amphiphilic copolymers to form ultra-stable uPA-PTXD NPs with high drug loading capacity. Diselenide bond (Se-Se) in uPA-PTXD NPs could be selectively cleaved by abnormally high reduced potential in tumor microenvironment, releasing prototype drug, thus contributing to improved anti-cancer efficacy. Endowed with TNBC-targeting ligand uPA peptide, uPA-PTXD NPs exhibited reduced systemic toxicity and enhanced drug accumulation in TNBC lesions, thus showed significant anti-tumor efficacy both in vitro and in vivo.

Conclusion: The comprehensive advantage of high drug loading, redox-controlled drug release and targeted tumor accumulation suggests uPA-PTXD NPs as a highly promising strategy for effective TNBC treatment.

Keywords: diselenide bond, nanoparticles, prodrugs, redox responsive, triple negative breast cancer

Introduction

Polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) have been explored as a promising platform for chemo-drug delivery, which could overcome various drawbacks of free drugs (e.g., poor solubility, broad and non-specific biodistribution, poor circulation half-life, etc.) 1-3. Polymeric NPs often involve the use of an amphiphilic copolymer, which can spontaneously self-assemble in aqueous solution during which hydrophobic drugs can be encapsulated into the core of the NPs. The stability of such NPs relies on the hydrophobic interactions between hydrophobic chemo-drugs and hydrophobic segments of the amphiphilic copolymers. Weak intermolecular force results in low drug loading (often significantly less than 10%) 4-6, compromised stability of NPs, and undesired burst-release during circulation, and therefore reduced therapeutic efficiency. To improve the therapeutic efficiency, anticancer drugs have been covalently conjugated to the copolymers, forming nanoscaled micelles or nanovehicles 7, 8. Although such strategy could increase the drug loading efficiency, the uncontrollable drug release profile due to the covalent conjugation would retard its pharmacodynamic effects, inducing long-term exposure of tumor to insufficient drug dose, thus activating the tumor to be metastatic and multi-drug resistant 9-11. To solve the uncontrollable drug release problem, many researchers conjugated anticancer drugs to amphiphilic copolymers via stimuli-responsive linkage, achieving temporally and spatially controlled drug release in response to triggers in the tumor microenvironment. However, due to the balance of hydrophobic and hydrophilic ratio in amphiphilic copolymers, the drug loading capacity is still limited 12-14. Therefore, it is still a great challenge to design new polymeric NPs that simultaneously achieve high drug loading capacity and controllable drug release.

In this regard, our approach employed a “structure defects” concept to the prodrug design by forming a dimeric structure with less rigidity. Rigid molecules may easily form crystals/aggregates during drug formulation, while less-rigid molecules with structure defects can prevent the formation of long-distance-order structure and large aggregates during self-assembly 15-18. Therefore, paclitaxel (PTX), a widely used hydrophobic anti-tumor drug was used as the model drug and embedded into the “structure defects” dimeric structure. We deliberately designed a dimeric PTXD-Se prodrug (Scheme 1), where two PTX molecules were conjugated to a phenol backbone with a freely rotatable side chain. Such unique structure was much less rigid than prototype PTX, which could effectively prevent the formation of long-range-order structure and large aggregates during nanoprecipitation, substantially improving the drug loading capacity.

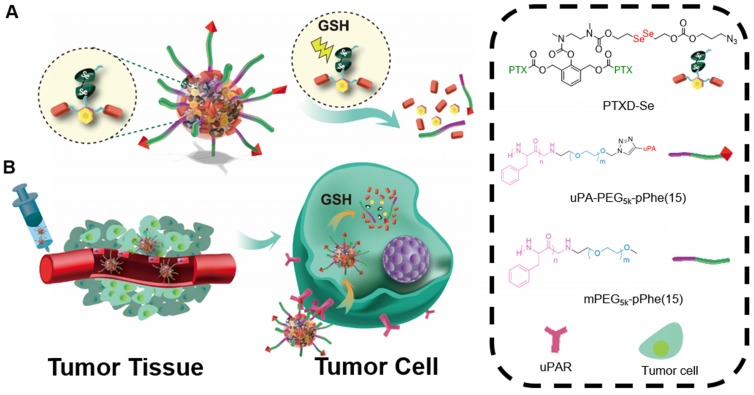

Scheme 1.

(A) Schematic illustration of uPA-PTXD NPs and GSH-triggered drug release profile. (B) In vivo uPAR-mediated transport and intracellular drug release.

Undesired drug release from drug delivery systems is another critical barrier to therapeutic efficacy. Stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems that display precise spatially controlled drug release in response to triggers at the tumor site have great potential in the field of controllable drug delivery 19-23. It is noteworthy that the intracellular glutathione (GSH) level (~10 mM) in tumor microenvironment is approximately three orders of magnitude higher than that of the extracellular environment (~10 µM) 24, serving as an ideal trigger for drug delivery design. To date, many scientists have employed disulfide bond (S-S) triggered by the high GSH concentration in tumor microenvironment 25-28. However, given the reality of the heterogeneously distributed GSH 29, the responsive property of disulfide bond is far from enough and a new trigger with higher sensitivity and specificity should be developed. Selenium's unique electronegativity and atomic radius leads to lower bond energy of Se-Se (172 kJ/mol) than C-C (346 kJ/mol) and commonly used S-S (240 kJ/mol) 30, 31, which makes it easier to be reduced in tumor microenvironment. Therefore, we introduced diselenide bond into PTX dimeric prodrug to achieve the ultra-sensitive redox responsiveness.

Taking advantage of the huge difference of GSH concentration between the extracellular and intracellular environments, we firstly applied diselenide-bond as the responsive unit in the prodrug design to obtain a novel redox-responsive diselenide-based PTX dimer prodrug (PTXD-Se). By encapsulating PTXD-Se into a biodegradable amphiphilic polypeptide copolymer, we successfully developed a well-controlled redox-responsive nanoparticle with extremely high drug loading. Noting that urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) plays a major role in invasive cancer cells and also shows high expression in TNBC 32, 33, a uPAR ligand, uPA peptide (sequence: VSNKYFSNIHW) 34, was covalently anchored onto the PTXD-Se NPs surface to achieve TNBC-targeting capability in vivo through binding with uPAR.

The novel uPA-PTXD NPs rationally designed have the following features: i) dimeric structure of PTX prodrug could enable ultra-high drug loading capacity; ii) the redox-sensitive diselenide bond could achieve high PTX stability and selective drug release inside tumor cells; iii) modification of uPA peptide onto NPs obviously improves the TNBC accumulation of PTX. The design, synthesis and characterization of the NPs were carried out. The drug formulation of the NPs was optimized. The in vitro drug release profile and tumor-targeting property were investigated, inspired by which, the in vivo anti-cancer efficacy was studied in detail. We believe uPA-PTXD NPs can well serve as a promising strategy for TNBC treatment.

Results and Discussion

Design and synthesis of PTXD-Se prodrug and outer-shell copolymers

Paclitaxel (PTX) is one of the most effective anticancer drugs in tumors including breast cancer, ovarian cancer and prostate cancers. PTX, as a cytoskeletal drug targeting tubulin, can stabilize the microtubule polymer from disassembly, therefore inhibiting proliferation of cancer cells 8. However, such hydrophobic drugs tend to form drug aggregates/crystals during formulation, which might highly compromise the drug loading efficiency. Therefore, we deliberately designed a dimeric PTXD-Se prodrug (Scheme 1), where two PTX molecules were conjugated to a phenol backbone with a freely rotatable side chain. Such unique structure was much less rigid than prototype PTX, which could effectively prevent the formation of long-distance-order structure and large aggregates during nanoprecipitation, resulting in high drug loading of NPs.

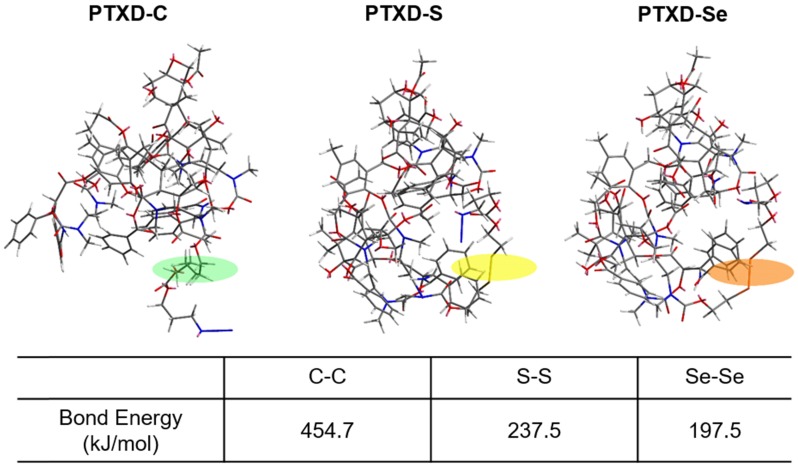

To further achieve a precise drug release profile, we introduced diselenide bond into the dimeric prodrug side chain. As illustrated in Scheme 2, we computationally calculated the detailed bond energy of C-C, S-S and Se-Se in the designed dimeric PTXD prodrugs (PTXD-C, PTXD-S, PTXD-Se). PTXD-C, PTXD-S and PTXD-Se prodrugs showed similar chemical structures; however, selenium's unique electronegativity and atomic radius lead to a lower bond energy (197.5 kJ/mol), which could be more sensitive to redox potential in the tumor intracellular environment. Therefore, diselenide bond is more sensitive to cleavage in the high concentration of GSH in tumor cytosol, which will induce self-cyclization and 1,6-elimination to release prototype PTX spontaneously.

Scheme 2.

Calculate bond energy of C-C, S-S and Se-Se in PTXD-C, PTXD-S, and PTXD-Se prodrugs. Green frame: C-C, yellow frame: S-S, orange frame: Se-Se

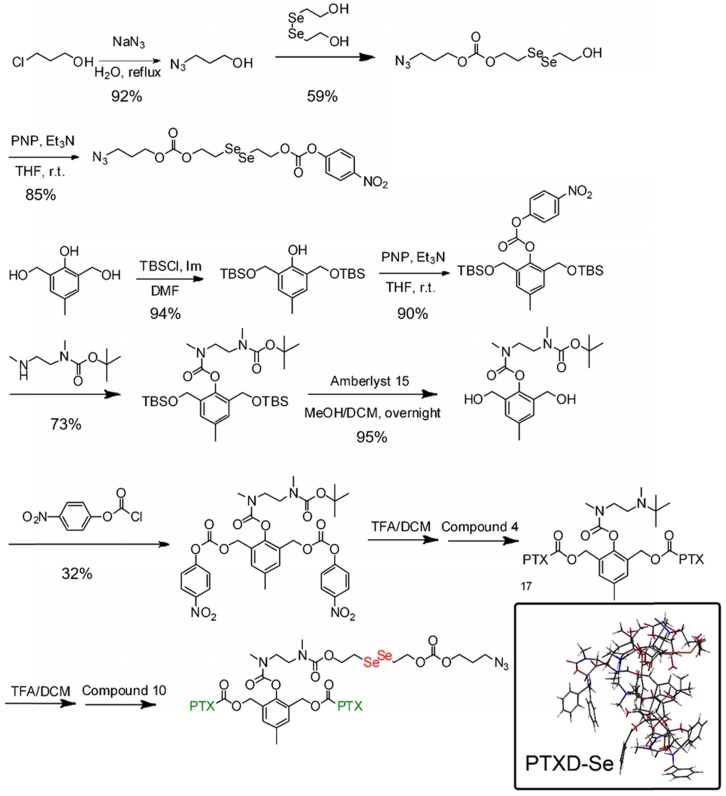

The synthetic routes for diselenide-containing redox-responsive PTXD-Se prodrug and outer-shell amphiphilic polypeptide copolymers were illustrated in Scheme 3 and Scheme S1. The chemical identities of PTXD-Se prodrug were confirmed by 1H NMR (Figure S1-12).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis route of PTXD-Se.

Amphiphilic copolymers mPEG5k-pPhe(n) and N3-PEG5k-pPhe(15) were synthesized via ROP reaction in the presence of mPEG5k-NH2 and N3-PEG5k-NH2 as the initiator and L-phenylalanine N-carboxyanhydride (Phe-NCA) as monomer. To further optimize the PTXD NPs formulations, we adjusted the molar composition ratio of PEG to Phe-NCA moieties from 1:5, 1:10, 1:15 to 1:20, forming a series of amphiphilic copolymers. The characterization peaks of PEG at 3.54 ppm (methylene groups, EG), Phe at 4.5 ppm (methylene of benzyl group) and at 7.21 ppm (phenolic group) in 1H NMR spectra confirmed the successful synthesis of mPEG5k-pPhe(15) (Figure S13).

To endow the NPs with TNBC-targeting capability, uPA peptide was conjugated to the end of N3-PEG5k-pPhe(15) via copper(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne click reaction, forming TNBC-targeting copolymer uPA-PEG5k-pPhe(15). Hexynoic-modified uPA peptide could react with the azide group of N3-PEG5k-pPhe(15) in the presence of CuI catalyst to form physiologically stable triazole (Scheme S1). As shown in IR spectra (Figure S14), the disappearance of the peak at ~2100 cm-1 also indicated the successful synthesis of uPA-PEG5k-pPhe(15).

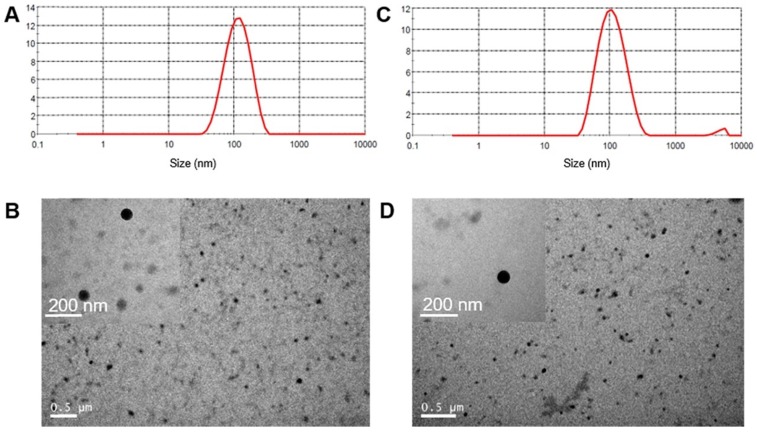

Formulation and characterization of PTXD-Se NPs

To form the polymeric NPs with high drug loading capacity, we encapsulated dimeric PTXD-Se with amphiphilic polymers acting as surface stabilizers while the dimeric prodrug component formed the condensed core (as shown in Scheme 1). During polypeptide copolymerization, we used different molar ratios of hydrophobic monomer NCA-Phe to adjust the hydrophobic and hydrophilic property of the outer shell copolymer, to optimize the most appropriate copolymer for dimeric PTXD-Se prodrug encapsulation. By modulating the weight ratio of PTXD-Se and amphiphilic polypeptide copolymer, we prepared a series of NPs with different particle sizes and stability (Figure 1). PEG5k-pPhe (15), due to its sufficient hydrophobicity and phenol groups in the amphiphilic copolymer, showed strong intermolecular interaction with hydrophobic PTXD-Se prodrug and spontaneously self-assembled into the smallest and most uniform nanoparticles with average particle size of 103.6±2.4 nm and PDI of 0.141±0.004 (Table 1, Entry 3), which is suitable for passive accumulation in cancer tissue via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect 35, 36. As for TNBC targeting NPs, uPA-PTXD NPs showed a slightly increased diameter due to the modification of uPA peptide. The morphologies of PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs were visualized by TEM (Figure 1B, D), which revealed spherical morphology with a condensed drug aggregate core. Such phenomenon is rarely observed in organic material-based nanoparticles, which directly reveals the high encapsulation capacity of PTXD-Se NPs. To further examine the stability of the nanoparticles, uPA-PTXD NPs were incubated with PBS (pH 7.4) and 5% FBS-containing PBS buffer for 12 h. As shown in Figure S17, uPA-PTXD NPs showed ultra-stability against PBS and FBS with little particle size change.

Figure 1.

Size distribution of PTXD-Se NPs (A) and uPA-PTXD NPs (C). TEM images of PTXD-Se NPs (B) and uPA-PTXD NPs (D).

Table 1.

Formulation of PTXD-Se with mPEG5k-pPhe(15) via nanoprecipitation.

| PTXD-Se /PEG5k-pPhe(15) |

Day 0 | Day 7 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (nm) | PDI | Size (nm) | PDI | ||

| 1 | 8:1 | 150.3±1.1 | 0.184±0.046 | 190.8±5.5 | 0.211±0.038 |

| 2 | 4:1 | 135.0±7.2 | 0.170±0.057 | 152.5±5.9 | 0.170±0.057 |

| 3 | 2:1 | 103.6±2.4 | 0.141±0.004 | 107.8±5.6 | 0.158±0.011 |

| 4 | 1:1 | 136.7±5.2 | 0.447±0.011 | - | - |

| 5 | 1:2 | - | 0.317±0.013 | - | - |

| 6 | 1:4 | - | - | - | - |

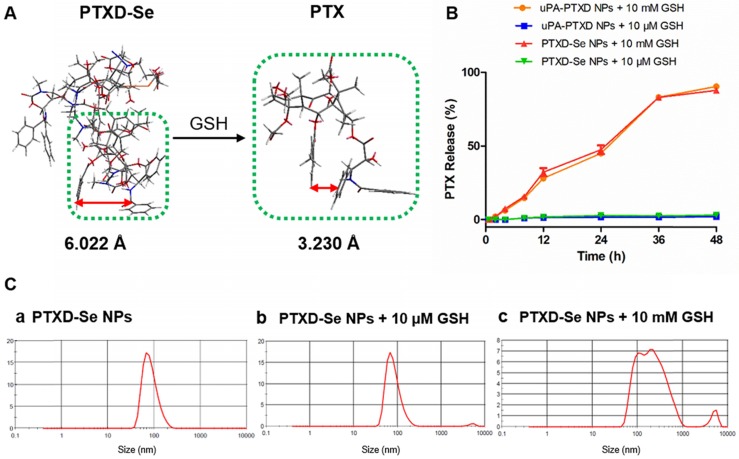

In previous studies formulating NPs of water-insoluble drugs by employing the nano-precipitation strategy, fast aggregation during formulation often occurs, leading to large precipitates and low drug loading capacity. In order to avoid such phenomenon, we introduced the “structure defects” theory to the drug modification with the aim of obtaining weaker rigidity and corresponding less packing efficiency 15. For instance, as illustrated in Figure 2A, upon the dimerization, a flexible configuration that is different from the prototype is obtained. To be more specific, an increased distance between the benzene rings of PTX was significantly noticed, which might increase the possibility of intermolecular instead of intramolecular interactions. Subsequently, it is deduced that a cross-linked type structure will be thus formed in the core of the nanoprecipitate. As calculated by HPLC, the drug encapsulation efficiency (EE) and drug loading (DL) of PTXD-Se NPs were 98% and 36.4%, which exceeded those of most current anti-cancer drug formulations.

Figure 2.

(A) Calculated benzene ring distance variation of PTX between PTXD-Se prodrug and prototype PTX after GSH-triggered release. Green frame represents the PTX molecule; orange frame represents Se-Se bond. (B) In vitro CPT release from PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs triggered by different concentrations of GSH in PBS (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). (C) NPs size change in the presence of 10 μM GSH (b) and 10 mM GSH (c) after 4 h incubation.

In vitro PTX release profile and mechanism

To verify the controllable tumor microenvironment-responsive drug release property, we investigated the in vitro drug release behavior of PTXD NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs in PBS (pH 7.4) with different GSH concentrations (10 mM and 10 μM GSH) mimicking the physiological and tumor intracellular redox microenvironments respectively. As shown in Figure 2B, prototype PTX was released in a controlled manner in the presence of GSH in 48 h. In the presence of 10 mM GSH, which represents the tumor intracellular GSH concentration, as high as 89.9% and 89.1% of prototype PTX was released from PTXD NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs, respectively. As for 10 μM GSH, which represents the extracellular GSH concentration, only about 3% PTX was released. We also monitored the particle size of PTXD-Se NPs in the presence of different GSH concentrations. The particle size of PTXD-Se NPs changed dramatically and formed aggregates in the presence of 10 mM GSH after 4 h incubation (Figure 2C). Whereas, the particle size of PTXD-Se NPs remained unchanged in the presence of 10 μM GSH even after 12 h incubation (Figure 2C).

With the diselenide bond imbedded into the self-immolative prodrug PTXD-Se, the GSH-responsive PTX release property was achieved via the cleavage of diselenide bond, which is regarded as much more sensitive than conventional disulfide bond to reducing agents including GSH. Encountered with the high concentration of GSH in the cancer cell cytosol, the diselenide bond in PTXD-Se prodrug could be cleaved and reduced to selenol, which could further cyclize toward the carbamate group. After cyclization of the spacer, exposed phenol group could induce 1,4-elimination self-immolation procedures and release prototype PTX based on electronic cascade (Scheme S2). The uncaged prototype PTX molecule is a more rigid structure compared to dimeric PTXD-Se. Increased intramolecular hydrophobic interaction in prototype PTX led to a decreased benzene ring distance compared to that of dimeric PTXD-Se (Figure 2A). Such configuration variation could disrupt the original cross-linked type structure in the nanoparticle, and a loosened composition is easier to be attacked by environmental GSH, which further induces prototype PTX liberation.

Cellular uptake and internalization mechanism study

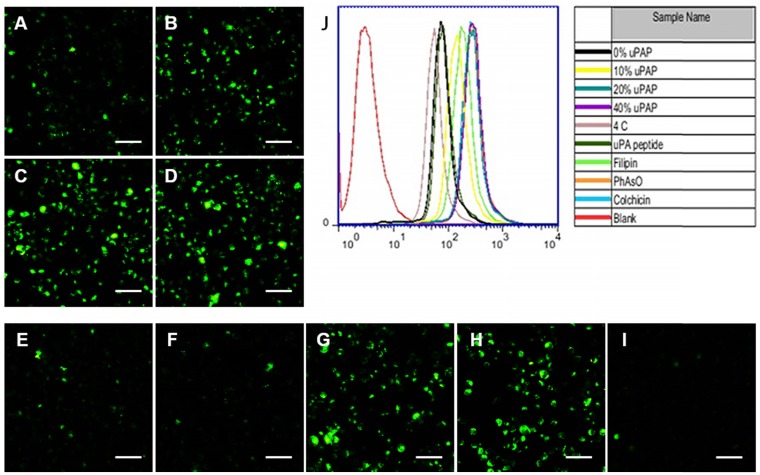

The urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) expression is reported to be substantially upregulated in invasive cancer cells compared to healthy cells or benign tumors 25. We confirmed the overexpression of uPAR in MDA-MB-231 cells, which showed almost 5.6-fold higher expression than non-carcinoma HEK-293 cells (Figure S16), consistent with previous studies 37. Inspired by the relatively high expression of uPAR in MDA-MB-231 cells, we conjugated hexynoic uPA peptide, a specific ligand to uPAR, onto N3-PEG5k-pPhe(15) copolymer via click reaction for TNBC targeting. Compared with PTXD-Se NPs, the cellular uptake of uPA-PTXD NPs was significantly enhanced with increasing uPA-PEG5k-pPhe(15) ratio (from 10 wt% to 40 wt%) (Figure 3A-D, J). Whereas, there was no significant difference of cellular uptake between 20% and 40% uPA-PEG5k-pPhe(15) ratios. Such phenomenon might be due to saturation of the transport capacity of uPAR expressed on the MDA-MB-231 cells. Considering the potential risk of mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) clearance and aiming for systemic long circulation, we finally selected the 20% uPA-modified NPs (uPA-PTXD NPs) in the following studies.

Figure 3.

Cellular uptake of (A) PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs with uPA modifying ratios of (B) 10, (C) 20, and (D) 40 wt% in MDA-MB-231 cells after 30 min incubation. (E-I) Possible endocytosis pathway of uPA-PTXD NPs in this study. Cells were blocked by the inhibitors (E) 20 μM uPA peptide, (F) 1 μg/mL filipin, (G) 0.3 μg/mL PhAsO, (H) 1 μg/mL Colchicine, and (I) cells were incubated at 4 °C. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (J) Quantitative results of cellular uptake and endocytosis pathway from flow cytometry analysis.

We further investigated the internalization mechanism of uPA-PTXD NPs. Multiple inhibitors including uPA peptide (blocking uPAR), filipin (blocking caveolae-mediated pathway), colchicine (blocking macropinocytosis) and phenylarsine oxide (blocking clathrin-dependent pathway) were pretreated to MDA-MB-231 cells to block several endocytosis pathways (Figure 3). Notably, cellular uptake was significantly inhibited by low concentration of uPA peptide (Figure 3E), which indicated the active targeting capability of uPA-PTXD NPs. Among the three endocytic inhibitors, filipin exhibited the most significant inhibition of uPA-PTXD NPs internalization (Figure 3F), indicating that the main endocytosis pathway of uPA-PTXD NPs is caveolae mediated. The internalization was also significantly inhibited by 4 °C (Figure 3I), which indicated an energy-dependent cellular uptake. Considering these result, we believe that uPA peptide might be responsible for actively recognizing and binding to MDA-MB-231 cells through uPAR, and the intrinsic properties of NPs such as size and charge played a critical role in uPA-PTXD NPs internalization.

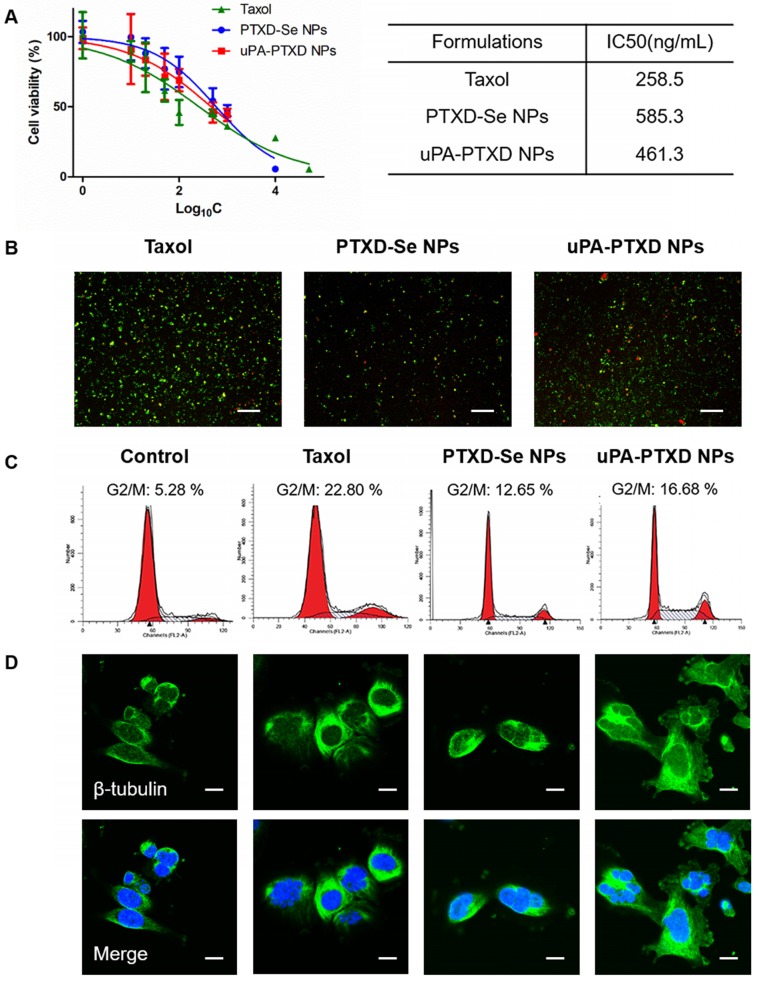

In vitro anticancer efficacy

To evaluate the in vitro anticancer efficacy of the NPs, MTT cytotoxicity assay on TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells and cellular apoptosis assays were implemented (Figure 4). By incubating MDA-MB-231 cells with the commercially available PTX formulation Taxol, PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs for 72 h, significant cell proliferation inhibition was observed in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4A). It was noticed that uPA-PTXD NPs showed lower IC50 value (461.3 ng/mL) than PTXD-Se NPs (585.3 ng/mL) (Figure 4A). Such difference was mainly due to the active targeting effect of uPA peptide. IC50 values of PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs were slightly higher than that of Taxol. Such phenomenon was ascribed to the relatively slower release profile of the PTXD-Se prodrug compared to the burst release of free PTX in Taxol.

Figure 4.

(A) Cytotoxicity and (B) cellular apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 cells induced by Taxol, PTXD-Se NPs, and uPA-PTXD NPs. Green, Annexin V-FITC-labeled apoptotic cells; red, PI-labeled dead cells; scale bars represent 20 μm. (C) Cell cycle distribution and (D) confocal microscopy images of β-tubulin alteration induced by Taxol, PTXD-Se NPs, and uPA-PTXD NPs. Green: immunocytochemcial staining of β-tubulin; blue, nuclei stained with DAPI; scale bars represent 10 μm.

The in vitro anticancer efficacy of NPs was further confirmed by Annexin V-FITC and PI assay on MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 4B). Annexin V-FITC was used to indicate early apoptosis (green), while PI staining could indicate late apoptosis or necrotic cells (red). The results of the apoptosis experiment were consistent with the MTT study (Figure 4A), which showed the potential of uPA-PTXD NPs as a promising anti-cancer drug delivery system.

A previous study proved that PTX could trigger cell cycle arrest at G2/M to induce robust mitotic delay through microtubule stabilization 16. We investigated cell cycle arrest induced by Taxol, PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs via Cell Cycle Detection Kit (KeyGEN BioTECH). G2/M arrest in MDA-MB-231 cells was investigated after 48 h treatment with Taxol, PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs. As shown in Figure 4C, Taxol, PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs all showed significant G2/M phase delay (12.65-22.8%). Compared to PTXD-Se NPs, uPA-PTXD NPs showed slightly higher G2/M phase delay, which might be due to the active targeting effect of uPA modification. It was noticed that the G2/M phase delay effect of both prodrug NPs was lower than that of Taxol. Such phenomenon was understandable since the burst release of prototype PTX in Taxol is quicker than the release profile of PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs. We also studied the tubulin alteration effect of the different formulations. Treated with Taxol, PTXD NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs separately, MDA-MB-231 cells all showed significant tubulin aggregation and reduction of free cytosolic tubulin compared to untreated cells (Figure 4D). Such results indicated intracellular GSH could successfully cleave the diselenide bond and release prototype PTX to induce cytotoxicity, as we designed. The percentage of G2/M phase delay and microtubule stabilization effect were consistent with the previous MTT study and cell apoptosis study, which further confirmed the active targeting effect of uPA peptide and the promising anti-tumor efficacy of uPA-PTXD NPs.

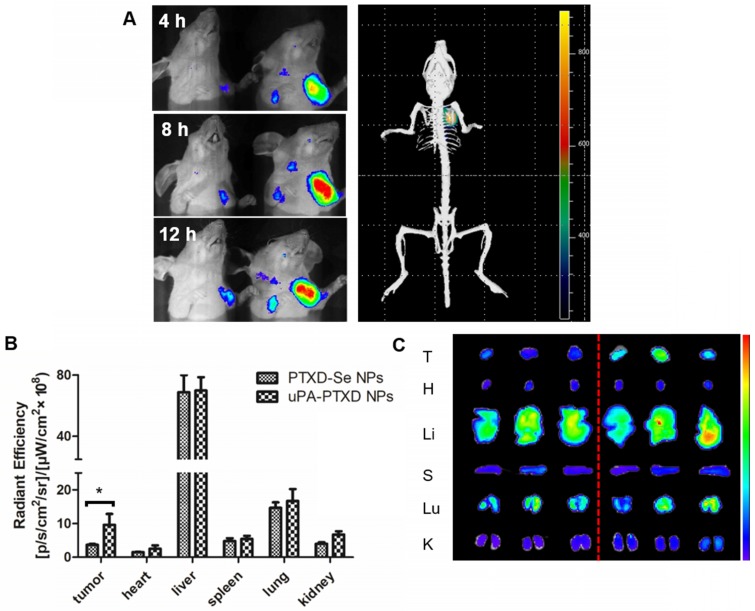

Enhanced TNBC accumulation and reduced systemic toxicity in vivo

To evaluate the TNBC-targeting effect of uPA-PTXD NPs, BODIPY-loaded PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs were intravenously injected into orthotopic MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing nude mice at an equivalent amount of BODIPY. The real-time biodistribution of NPs were tracked by in vivo imaging system. As shown in Figure 5A, both NPs showed progressive accumulation in target tissue due to the EPR effect. Nevertheless, uPA-PTXD NPs exhibited significantly higher targeting efficiency in TNBC tissues compared to non-targeting PTXD-Se NPs from 4 h to 12 h (Figure 5A). Furthermore, 3D imaging of uPA-PTXD NPs-treated mice showed co-localization of uPA-PTXD NPs to the tumor tissue.

Figure 5.

Biodistribution and targeting effects of PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs in MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing mice. (A) In vivo 3D imaging 12 h after i.v. injection of uPA-PTXD NPs and in vivo 2D imaging 4 h (a), 8 h (b), 12 h (c) after i.v. injection of PTXD-Se NPs (left) and uPA-PTXD NPs (right). (B) Quantitative fluorescence intensities of tumors and organs from ex vivo imaging. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=3), *P<0.05. (C) Ex vivo images of tumors and organs of tumor-bearing mice sacrificed at 12 h after i.v. injection of PTXD-Se NPs (left) and uPA-PTXD NPs (right).

After 12 h, tumors and major organs were excised for ex vivo imaging to further quantify the biodistribution of the NPs (Figure 5B-C). uPA-PTXD NPs showed significantly higher accumulation in tumor tissues comparing to PTXD-Se NPs. Moreover, uPA-PTXD exhibited similar accumulation in major organs (Figure 5B-C). The relatively high accumulation in the liver is mainly due to the intrinsic size distribution of the NPs, and indicated that the NPs were eliminated predominately via the MPS system such as Kupffer cells in the liver. To further confirm the potential liver and systemic toxicity, H&E staining of the principal organs was also performed following in vivo anti-cancer efficacy experiments. As shown in Figure 6D, uPA-PTXD NPs did not cause severe toxicity to the liver tissue or other major organs. Therefore, uPA-PTXD NPs could serve as an efficient TNBC-targeting drug delivery system, which could reduce anti-cancer drug systemic toxicity while improving the drug delivery efficiency to TNBC sites.

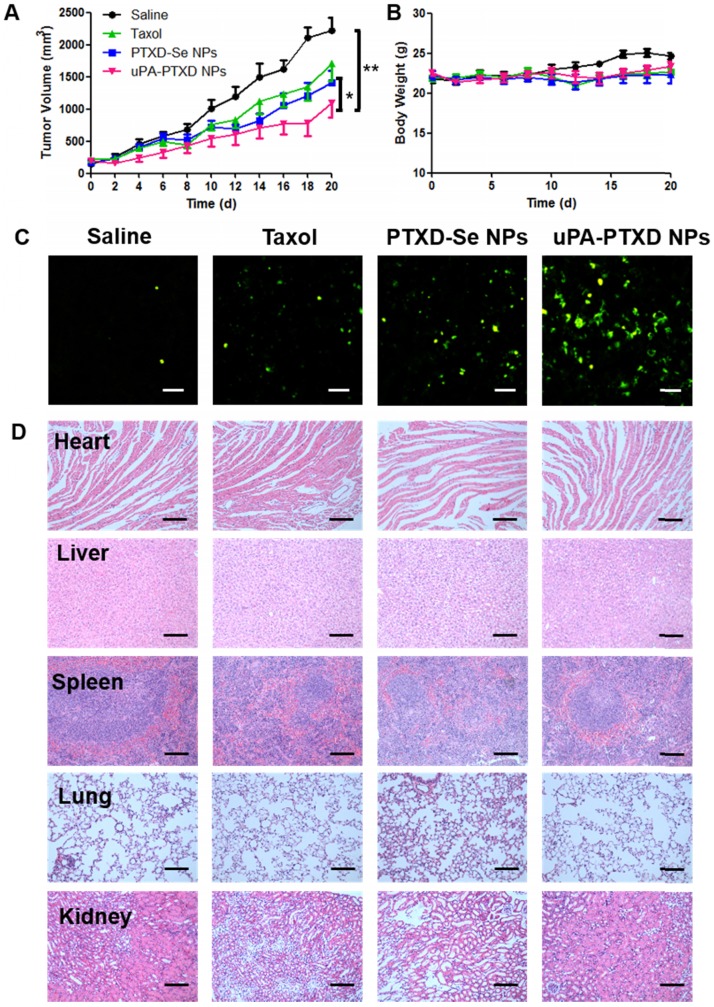

Figure 6.

(A) Tumor volume and (B) body weight changes of MDA-MB-231 orthotopic breast cancer xenograft mice after 4-dose i.v. injection of different PTX formulations at a normalized PTX dose of 5 mg/kg on day 0, 4, 8 and 12. Saline group served as control. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=8). *P<0.05; **P<0.01. (C) Representative histological images of MDA-MB-231 tumor xenografts of treated groups using TUNEL assay. Green, apoptotic cells; scale bars represent 50 μm. (D) H&E staining of main organs from MDA-MB-231 tumor xenografts of treated groups; scale bars represent 100 μm.

In vivo anti-tumor efficacy study

The antitumor effects of the NPs were evaluated in MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing mice. Saline, Taxol, PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs were administered on day 0, 4, 8 and 12. Compared with the control group (saline), tumor growth was apparently inhibited in Taxol, PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs groups, whereas uPA-PTXD NPs showed the most significant antitumor efficacy (Figure 6A). Various degrees of limited tumor inhibition were observed in the Taxol and PTXD-Se NPs groups mainly due to the rapid clearance of Taxol or the absence of a tumor targeting ligand. The mice body weights were also recorded every two days to evaluate the general toxicity of the different treatments (Figure 6B), and all groups showed no significant difference.

After four treatments, mice were sacrificed and tumors were excised and stained with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay to evaluate apoptosis at the tissue level (Figure 6C). The green signal represents apoptosis sites in the tumor tissue, whereas blue signal indicates the nuclei. Compared with the Taxol group, PTXD-Se NPs-treated mice presented better antitumor efficacy, possibly due to NPs accumulation caused by the EPR effect and the long circulation of the drug formulation. uPA-PTXD NPs-treated mice showed the most extensive apoptosis, indicating the most effective antitumor efficacy, which was consistent with the tumor volumes observation. Such results indicated the excellent anti-tumor efficacy of uPA-PTXD NPs.

Conclusion

We designed a novel dimeric structure prodrug with intrinsic capability of forming nano-aggregates instead of long-ranged ordered, large aggregates or precipitates in aqueous solution, and used it as the key structural element for the preparation of nanoparticles with ultra-high drug loadings. uPA-PTXD NPs exhibited an extremely high drug loading rate, which could significantly reduce the polymer burden in drug administration, while the quantitative drug loading efficiency relieves concerns of quality control and reproducibility of the nanomedicine. The diselenide bond in the NPs successfully enabled a tumor redox microenvironment-controlled drug release profile, which prevented unexpected pre-drug leakage in physiological condition. The significant TNBC targeting ability of uPA-PTXD NPs achieved TNBC accumulation, thus exhibiting stronger anti-tumor efficacy both in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, uPA-PTXD NPs have great potential in TNBC therapy and such dimeric structured nanoplatform could be applied as a potential drug platform for drug delivery.

Methods

Materials

Anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF), tetrahydrofuran (THF) and dichloromethane (DCM) were dried with a column packed with 4 Å molecular sieves. Paclitaxel (PTX) was purchased from Meilun Biological Technology Co., Ltd (Dalian, China). Methoxypolyethylene glycol amine (mPEG5K-NH2) and azide polyethylene glycol amine (N3-PEG5K-NH2) were purchased from JemKem technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). Sodium azide, 2-chloroethanol, dithiothreitol(DTT), glutathione (GSH) and MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide), coumrin-6, DAPI were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The fluorescent probe BODIPY (700/730) was synthesized as described previously. Selenium, 3-chloro-1-propanol, N,N'-dimethylethylenediamine, hydrazine hydrate, 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate (PNP), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), 2,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)-4-cresol, imidazole, tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride (TBSCl), di-tert-butyl dicarbonate ((Boc)2O), amberlyst-15, trifluoroacetic acid and copper(I) iodide were all purchased from J&K Chemical Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Triphosgene was purchased from Macklin Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). All other chemicals were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China) unless mentioned otherwise.

MDA-MB-231-luci cells and MDA-MB-231 cells, were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA) and Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) respectively. Both cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin G, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C under 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

Balb-c nude mice (female, 18-20 g) were purchased from the Department of Experimental Animals, Fudan University. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines evaluated and approved by the ethics committee of Fudan University. For construction of an orthotopic breast cancer xenograft model, 1×106 MDA-MB-231-luci cells in suspension solution of 5% Matrigel in 100 μL DMEM were subcutaneously inoculated into the right flank of mice under the fat pad.

Instrumentation

NMR spectra were measured using an NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). All chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm). Particle sizes and polydispersities (PDI) were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Zetasizer Nano-ZS, Malvern, U.K.). TEM samples were prepared by dropping NPs solutions on 200 mesh carbon film-supported copper grids and dried at room temperature overnight. The prepared samples were imaged using a 120 kV Biology Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) (Tecnai G2 SpiritBiotwin, FEI, USA). HPLC was performed using Agilent 1260 series (Palo Alto, CA, USA) coupled with a UV detector and fluorescence detector and a C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm). A gradient method was adopted using 0.1% TFA-H2O and acetonitrile (ACN) as mobile phase (Figure S15).

Synthesis of PTXD-Se and outer shell copolymers

The synthesis routes of PTXD-Se and outer shell copolymers are generally described in Scheme 3 and Scheme S1. Characterization of related compounds is shown in Figure S1-14.

Preparation of PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs

PTXD-Se was dissolved in DMF with mPEG5K-pPhe(15) at a certain ratio and the PTXD-Se concentration was 20 mg/mL if not specified. Then, 40 μL of the above solution was added dropwise into 2 mL of DI water with mild stirring using a magnetic bar. For uPA-modified NPs preparation, PTXD-Se, mPEG5k-pPhe(15) and uPA-PEG5k-pPhe(15) were dissolved at certain ratios and added dropwise into 2 mL of DI water with mild stirring.

To trace the NPs in vitro and in vivo, we encapsulated coumarin-6 and BODIPY(700/730), which contain large phenol rings and share similar hydrophobicity as the dimeric prodrug. coumarin-6 and BODIPY(700/730)-labeled NPs were prepared according to the procedure mentioned above by mixing PTXD-Se and outer shell materials (uPA-PEG-pPhe(15) or mPEG5k-pPhe(15)) at a weight ratio of 2:1 containing 0.5% dye in DMF.

All the formulation solutions were dialyzed against deionized water for 24 h using a membrane (MWCO 3500) to remove DMF solvent. Freshly prepared NPs were used for the following experiments.

Characterization of PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs

The particle size and distribution of PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Zetasizer Nano-ZS, Malvern, U.K.). The morphology of NPs was observed using TEM (Tecnai G2 SpiritBiotwin, FEI, USA).

To determine the stability of the nanoparticles, 100 μL freshly prepared NPs solution was diluted with 900 μL PBS (pH 7.4) and stored at 4 °C. For the serum stability test, 100 μL NPs was diluted with 900 μL 5% FBS-containing PBS buffer and stored at 4 °C for 12 h. The size and distribution of the NPs were monitored by DLS at certain time points.

To determine drug loading (DL) and drug encapsulation efficiency (LE) in PTXD-Se NPs, freshly prepared NPs were diluted in PBS and prototype PTX was cleaved by 100 mM DTT for 4 h. The amount of PTX was quantified via HPLC using a corresponding standard calibration curve. The weight of PTXD-Se NPs was collected via lyophilization. Drug loading was calculated as DL = w(PTX)/w(NPs) and drug encapsulation efficiency was calculated as EE = w(PTXD-Se)/w(initial PTXD-Se added).

In vitro PTX release from PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs

PTX release behavior was studied using a dialysis method (n=3). In brief, 300 μL freshly prepared PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs solutions were sealed in a dialysis bag (MWCO 2000). Then, the bag was immersed in 12 mL 0.1% tween 80-containing PBS buffer (pH 7.4) with 10 mM or 10 μM GSH and shaken at 37 °C. PTX release was monitored by HPLC and measured in triplicate at certain time points. The HPLC detection method and PTX standard curve are illustrated in Figure S15.

Cellular uptake and internalization mechanism

MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 6-well plates (Corning, USA) at a density of 4×104 cells/well and incubated overnight before reaching a confluence of 90%. Cells were incubated with coumarin-6-labeled PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs with different uPA modifying ratios (0, 10, 20, 40 wt%) at normalized coumarin-6 concentration. After 30 min incubation, cells were washed three times with Hank's and observed via a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). For flow cytometry analysis, cells were incubated with the above PTX formulations for 30 min, and then washed with Hank's three times, digested and re-suspended in PBS. The fluorescence intensity of coumarin-6 was analyzed using a flow cytometer (BD bioscience, Bedford, MA, USA) with 1×104 events recorded for each assay.

For the internalization mechanism study, cells were pre-incubated with various inhibitor solutions including 20 mM uPA peptide as uPAR inhibitor, 1 μg/mL filipin, 0.3 μg/mL phenylarine oxide (PhAsO), or 1 μg/mL colchicine. After 20 min pre-incubation, coumarin-6-labeled uPA-PTXD NPs were administered to the cells. After 30 min incubation at 37 °C or 4 °C, cells were washed with Hank's three times and then visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). For flow cytometry analysis, cells were treated as above, then digested and re-suspended in 500 μL PBS and analyzed using a flow cytometer (BD bioscience, Bedford, MA, USA).

In vitro cytotoxicity of PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs: Standard MTT protocol was followed to evaluate the cytotoxicity of PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs. Briefly, MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 1000 cells/well in 100 uL DMEM medium and were allowed to attach overnight. Then, cell media were discarded and cells were administrated freshly prepared Taxol, PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs formulations at certain concentrations of PTX. After 72 h, 10 μL of 5 mg/mL MTT solution was added to the medium and incubated at 37 °C for another 4 h. Then, the medium was carefully removed and the violet crystal was dissolved in 100 μL DMSO and quantified by absorption at 570 nm.

For the cell apoptosis assay, MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 1×104 cells/well and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h before reaching 80% confluence. Cells were treated with Taxol, PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs at a normalized PTX concentration of 1 μM for 24 h. Afterwards, cells were washed three times with Hank's, stained with Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (KeyGEN BioTECH, Nanjing, China) according to protocols and visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Cell cycle determination: MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1×104 cells/well and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h before reaching a confluence of 80%. Cells were administrated Taxol, PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs at a normalized PTX concentration of 1 μM for 12 h. The drug solutions were then removed and cells were incubated for another 12 h. Afterwards, cells were harvested and stained with Cell Cycle Detection Kit (KeyGEN BioTECH, Nanjing, China) according to protocols and detected by a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA). The percentage of cell cycle phases and apoptosis were analyzed with Flowjo 6.0.

Nanoparticle distribution in MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing nude mice

MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing nude mice were intravenously injected with BODIPY (700/730)-loaded NPs at a normalized BODIPY dose of 0.1 mg/kg. At 4 h, 8 h and 12 h, mice were anaesthetized by 1% isoflurane/oxygen mixture and monitored using an IVIS Spectrum with Living Image software v 4.2 (Caliper Life Science). After 12 h in vivo imaging, mice were anesthetized with diethyl ether and sacrificed by decapitation. Tumors and organs were dissected and imaged.

In vivo anti-tumor efficacy study

Orthotopic MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing mice were divided into four groups (n=8). An in vivo anti-tumor efficacy study was performed by intravenously injecting saline, Taxol, PTXD-Se NPs and uPA-PTXD NPs on day 0, 4, 8 and 12 at a normalized PTX dose of 5 mg/kg. Body weights of the nude mice were recorded every other day. Tumor volume was calculated as a×b2/2, where a is the largest and b is the smallest diameter.

At the end of the efficacy study, nude mice were sacrificed on day 20 and major organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney and tumor were excised and fixed in 4% neutral buffered formalin solution. Histological changes in main organ tissues were evaluated using hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining. The apoptotic cells in tumor tissues were evaluated using terminal deoxynucleoidyl transferase-mediated nick en labeling (TUNEL) assay (KeyGEN BioTECH, Nanjing, China).

Bond energy calculation

All the calculations were performed using Gaussian 16 program package and density functional theory (DFT) method. In order to avoid time-consuming computations, the central fragments of the molecules were chosen for the later calculations. All the structures were optimized at B3LYP level 38 with the basis sets of 6-31G (d, p) for C, H, O, N, S atoms and LanL08 (d) for Se atom. Grimme's DFT-D3 was applied for the available corrections of dispersion effects 39. To rationally describe pairwise interaction energies, the basis set superposition error (BSSE) was computed via Boys-Bernardi counterpoise technique. The solvent effect of water was treated with the polarizable continuum models (PCM) 40.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Software and the results are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical comparisons among multiple groups were assessed by P-test analysis.

Supplementary Material

Detail synthesis route of PTXD-Se, mPEG5k-pPhe(15) and uPA-PEG5k-pPhe(15), proposed release mechanism, 1H NMR, IR spectrum, HPLC method and RNA expression of uPAR, and additional results, scheme, table and figures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (81425023) and Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader (18XD1400500). J.C. acknowledges the support from NIH (R01 1R01CA207584-01A1).

Abbreviations

- DL

drug loading

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- EE

drug encapsulation efficiency

- EPR effect

the enhanced permeability and retention effect

- GSH

glutathione

- HE staining

hematoxylin and eosin

- LE

loading efficiency

- MPS

mononuclear phagocyte system

- NPs

nanoparticles

- PTX

paclitaxel

- TEM

transmission electron microscope

- TNBC

triple negative breast cancer

- TUNEL assay

terminal deoxynucleoidyl transferase-mediated nicken labeling assay

- uPAR

the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor.

References

- 1.Zhang Y, Cai K, Li C, Guo Q, Chen Q, He X. et al. Macrophage-membrane-coated nanoparticles for tumor-targeted chemotherapy. Nano Lett. 2018;18(3):1908–1915. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b05263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J, Jiang X, Guo Y, An S, Kuang Y, Ma H. et al. Linear-dendritic copolymer composed of polyethylene glycol and all-trans-retinoic acid as drug delivery platform for paclitaxel against breast cancer. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015;26:418–26. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo Y, Zhang Y, Li J, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Jiang X. et al. Cell microenvironment-controlled antitumor drug releasing-nanomicelles for GLUT1-targeting hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:5444–53. doi: 10.1021/am5091462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao Q, Dai Z, Hoon Choi J, Kim D. Building stable MMP2-responsive multifunctional polymeric micelles by an all-in-one polymer-lipid conjugate for tumor-targeted intracellular drug delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:32520–33. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b09511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mei L, Liu Y, Zhang H, Zhang Z, Gao H, He Q. Antitumor and antimetastasis activities of heparin-based micelle served as both carrier and drug. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:9577–89. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Li Q, Liu X, Zhang C, Wu Z, Guo X. Mesoscale simulations and experimental studies of pH-sensitive micelles for controlled drug delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interface. 2015;7:25592–600. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b08366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Yang H, Zhang Y, Jiang X, Guo Y, An S. et al. Choline derivate-modified doxorubicin loaded micelle for glioma therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:21589–601. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b07045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Lu Y, Zhang Y, He X, Chen Q, Liu L. et al. Tumor-targeting micelles based on linear-dendritic PEG-PTX8 conjugate for triple negative breast cancer therapy. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2017;14:3409–21. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottesman M, Fojo T, Bates S. Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent transporters. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:48–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillet J, Gottesman M. Mechanisms of multidrug resistance in cancer. Methods Mol Biol (N Y) 2010;596:47–76. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-416-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kunjachan S, Rychlik B, Storm G, Kiessling F, Lammers T. Multidrug resistance: Physiological principles and nanomedical solutions. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2013;65:1852–65. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu X, Hu J, Tian J. et al. Polyprodrug amphiphiles: hierarchical assemblies for shape-eegulated cellular internalization, trafficking, and drug delivery[J] J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(46):17617. doi: 10.1021/ja409686x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ke W, Yin W, Zha Z. et al. A robust strategy for preparation of sequential stimuli-responsive block copolymer prodrugs via thiolactone chemistry to overcome multiple anticancer drug delivery barriers[J] Biomaterials. 2017;154:261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Li Y, Wang Y. et al. Polymer prodrug-based nanoreactors activated by tumor acidity for orchestrated oxidation/chemotherapy[J] Nano Lett. 2017;17(11):6983–6990. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b03531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai K, He X, Song Z, Yin Q, Zhang Y, Uckun F. et al. Dimeric drug polymeric nanoparticles with exceptionally high drug loading and quantitative loading efficiency[J] J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:3458–61. doi: 10.1021/ja513034e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lv S, Wu Y, Cai K. et al. High drug loading and sub-quantitative loading efficiency of polymeric micelles driven by donor-receptor coordination interactions.[J] J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(4):1235–1238. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Liu D, Zheng Q. et al. Disulfide bond bridge insertion turns hydrophobic anticancer prodrugs into self-assembled nanomedicines[J] Nano Letters. 2014;14(10):5577–83. doi: 10.1021/nl502044x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, He F, Xiang K. et al. CD44-targeted facile enzymatic activatable chitosan nanoparticles for efficient antitumor therapy and reversal of multidrug resistance[J] Biomacromolecules. 2018;19(3):883–895. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.7b01676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Lu Y, Wang F, An S, Zhang Y, Sun T. et al. ATP/pH dual responsive nanoparticle with d-[des-Arg10]kallidin mediated efficient in vivo targeting drug delivery[J] Small. 2017;13(3):1602494. doi: 10.1002/smll.201602494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He X, Chen X, Liu L, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Zhang Y. et al. Sequentially triggered nanoparticles with tumor penetration and intelligent drug release for pancreatic cancer therapy[J] Adv Sci. 2018;5(5):1701070. doi: 10.1002/advs.201701070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.An S, Lu X, Zhao W, Sun T, Zhang Y, Lu Y. et al. Amino acid metabolism abnormity and microenvironment variation mediated targeting and controlled glioma chemotherapy[J] Small. 2016;12:5633–45. doi: 10.1002/smll.201601249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang C, Pan D, Li J. et al. Enzyme-responsive peptide dendrimer-gemcitabine conjugate as a controlled-release drug delivery vehicle with enhanced antitumor efficacy[J] Acta Biomater. 2017;9(8):6865–6877. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ning L, Hao C, Lei J. et al. Enzyme-sensitive and amphiphilic PEGylated dendrimer-paclitaxel prodrug based nanoparticles for enhanced stability and anticancer efficacy[J] ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(8):6865–6877. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b15505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shao K, Ding N, Huang S, Ren S, Zhang Y. et al. Smart nanodevice combined tumor-specific vector with cellular microenvironment-triggered property for highly effective antiglioma therapy[J] ACS nano. 2014;8:1191–203. doi: 10.1021/nn406285x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Yin Q, Yin L, Ma L, Tang L, Cheng J. Chain-shattering polymeric therapeutics with on-demand drug-release capability[J] Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:6435–9. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai K, Yen J, Yin Q, Liu Y, Song Z, Lezmi S. et al. Redox-responsive self-assembled chain-shattering polymeric therapeutics[J] Biomater Sci. 2015;3:1061–5. doi: 10.1039/C4BM00452C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H, Xu M, Xiong M, Cheng J. Reduction-responsive dithiomaleimide-based nanomedicine with high drug loading and FRET-indicated drug release[J] Chem Commun. 2015;51:4807–10. doi: 10.1039/c5cc00148j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo Q, Xiao X, Dai X. et al. Cross-linked and biodegradable polymeric system as a safe magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent[J] ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(2):1575–1588. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b16345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Sun X, Mao W, Sun W, Tang J, Sui M. et al. Tumor redox heterogeneity-responsive prodrug nanocapsules for cancer chemotherapy[J] Adv Mater. 2013;25:3670–6. doi: 10.1002/adma.201300929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu H, Cao W, Zhang X. Selenium-containing polymers: promising biomaterials for controlled release and enzyme mimics[J] Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:1647–58. doi: 10.1021/ar4000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma N, Li Y, Xu H, Wang Z, Zhang X. Dual redox responsive assemblies formed from diselenide block copolymers[J] J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:442–3. doi: 10.1021/ja908124g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller-Kleinhenz J, Guo X, Qian W. et al. Dual-targeting Wnt and uPA receptors using peptide conjugated ultra-small nanoparticle drug carriers inhibited cancer stem-cell phenotype in chemo-resistant breast cancer[J] Biomaterials. 2018;152:47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huber M, Mall R, Braselmann H. et al. uPAR enhances malignant potential of triple-negative breast cancer by directly interacting with uPA and IGF1R[J] BMC cancer. 2016;16:615. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2663-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun GB, Sugahara KN, Yu OM, Kotamraju VR, Mölder T, Lowy AM. et al. Urokinase-controlled tumor penetrating peptide[J] J Controlled Release. 2016;232:188–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fang J, Nakamura H, Maeda H. The EPR effect: Unique features of tumor blood vessels for drug delivery, factors involved, and limitations and augmentation of the effect[J] Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2011;63:136–51. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertrand N, Wu J, Xu X, Kamaly N, Farokhzad OC. Cancer nanotechnology: the impact of passive and active targeting in the era of modern cancer biology[J] Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2014;66:2–25. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rullo AF, Fitzgerald KJ, Muthusamy V, Liu M, Yuan C, Huang PM. et al. Re-engineering the immune response to metastatic cancer: antibody-recruiting small molecules targeting the urokinase receptor[J] Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;128:3706–10. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Development of the colle-salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density[J] Physical review B, Condensed matter. 1988;37:785–9. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goerigk L, Grimme S. A thorough benchmark of density functional methods for general main group thermochemistry, kinetics, and noncovalent interactions[J] Physical chemistry chemical physics: PCCP. 2011;13:6670–88. doi: 10.1039/c0cp02984j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomasi J, Mennucci B, Cammi R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models[J] Chem Rev. 2005;105:2999–3093. doi: 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detail synthesis route of PTXD-Se, mPEG5k-pPhe(15) and uPA-PEG5k-pPhe(15), proposed release mechanism, 1H NMR, IR spectrum, HPLC method and RNA expression of uPAR, and additional results, scheme, table and figures.