Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, are becoming more prevalent and an increasing burden on society. Neurodegenerative diseases often arise in the milieu of neuro-inflammation of the brain. Reactive astrocytes are key regulators in the development of neuro-inflammation. This study describes the effects of Palm Fruit Bioactives (PFB) on the behavior of human astrocytes which have been activated by IL-1β. When activated, the astrocytes proliferate, release numerous cytokines/chemokines including TNFα, RANTES (CCL5), IP-10 (CXCL10), generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), and express specific cell surface biomarkers such as the Intercellular Adhesion Molecule (ICAM), Vascular Cellular Adhesion Molecule (VCAM) and the Neuronal Cellular Adhesion Molecule (NCAM). Interleukin 1-beta (IL-1β) causes activation of human astrocytes with marked upregulation of pro-inflammatory genes. We show significant inhibition of these pro-inflammatory processes when IL-1β-activated astrocytes are exposed to PFB. PFB causes a dose-dependent and time-dependent reduction in specific cytokines: TNFα, RANTES, and IP-10. We also show that PFB significantly reduces ROS production by IL-1β-activated astrocytes. Furthermore, PFB also reduces the expression of ICAM and VCAM, both in activated and naïve human astrocytes in vitro. Since reactive astrocytes play an essential role in the neuroinflammatory state preceding neurodegenerative diseases, this study suggests that PFB may have a potential role in their prevention and/or treatment.

Introduction

The normal aging process is associated with some inflammation in the brain and this neuro-inflammation often precedes neurodegenerative conditions1–3. Neuroinflammation is a prominent characteristic of multiple neurodegenerative disorders including multiple sclerosis (MS), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD) and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)4–8. Epidemiologic studies reveal that the global burden of these neurodegenerative diseases is increasing9–11.

Astrocytes are innate, immune, star-shaped glial cells found in the CNS, which upon activation, proliferate and produce cytokines and other inflammatory mediators12. Astrocytes are the most abundant glial cell type in the brain. They provide important functions including nutritional support of metabolites and growth factors to neurons, supporting the formation and plasticity of synapses, controlling immune cell activation and trafficking, and regulating the extracellular fluid environment of ions and neurotransmitters13,14. Following traumatic injury, the astrocytes are involved in wound healing processes15,16.

Current theories of neurodegenerative diseases have shifted the traditional focus from neurons to the role of the astrocytes17–19. The signaling pathways involving the cytokines and chemokines become dysregulated in neurodegenerative diseases20. These dysregulated signaling pathways have a major pathologic effect on the intricate network of astrocyte-neuron interactions and system dynamics12,14,17–21. CNS tissue damage often results from the dysregulated microglia and astrocytes21. Astrocytes comprise part of the innate immune system, able to detect danger signals with toll-like cell surface receptors and respond with the secretion of cytokines and chemokines which then may recruit lymphocytes and result in the subsequent activation of the adaptive immune system22,23.

Multiple types of injury to the brain will cause a neuro-inflammatory response including infection, trauma and toxins24. The endogenous cells mediating neuroinflammation in the brain are the microglia and astrocytes. Depending on the type of insult, microglia and astrocytes have both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory actions25–31. Resident microglia and infiltrating immune cells together drive astrocyte activation and reactivity31. Astrocytes play a key role in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases31–36. The astrocyte response repertoire includes activation of the adaptive immune system, neutralizing microbial pathogens, phagocytosis of dead cells and debris, secretion of neurotrophins, repair of the Blood Brain Barrier, phagocytosis of synapses, and encircling scar formation to restrict the expansion of infection or hematoma26,30,31,37–42. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) restricts the usual circulating leukocyte response to inflammation in the brain creating a unique “immune-privileged” territory in the brain13,22,23,29. This limitation restricts the access of many immune cells along with their associated cytokines and reactive oxygen species.

Reactive astrocytes were morphologically first described in the 1970s with the discovery of the intermediate filament protein GFAP (Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein)43. Anti-GFAP antibodies then allowed immunostaining of human glial tumors and GFAP quantitation using rocket electrophoresis44,45. Then with the molecular cloning of mouse Gfap, GFAP became the standard biomarker of reactive astrocytes46. However further experimental studies revealed marked heterogeneity of GFAP in astrocytes under varying conditions and even within the same brain25,31,33,44,47–50.

Analogous to the pro-inflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypic states for macrophages, transcriptome analysis reveals that there are two classes of reactive astrocytes called A1 and A225. The A1 astrocytes express pro-inflammatory genes and the A2 astrocytes express anti-inflammatory genes. The pro-inflammatory A1 reactive astrocytes show upregulation of Tnf (Tumor Necrosis Factor), Il-1b (Interleukin 1-beta) and produce increased amounts of reactive oxygen species51. The anti-inflammatory A2 reactive astrocytes show upregulation of Chil3 (Chitinase-like 3), Fzd1 (Frizzled class receptor 1), and Arg1(Arginase 1)52.

Astrocytes become activated becoming reactive astrocytes in response to multiple types of stimuli including infections, ischemia, trauma, cerebrovascular insult, the autoimmune response as well as in response to pH or ion imbalances53,54. Activated astrocytes initiate the neuroinflammatory cascade in vivo, in part due to its response to the cytokine IL-1β55.

Experimental data in the literature reveal that astrocytes, activated by IL-1β in vitro, display the same biologic activity as the reactive astrocytes found in the brain lesions of patients with neurodegenerative changes such as Alzheimer’s disease, Multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, thus supporting their use as a model of CNS neuroinflammation in the in vitro assays56–58. Activated astrocytes proliferate and express cell surface adhesion molecules (CAMs) including the intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM), the vascular cellular adhesion molecule (VCAM) and neuronal cellular adhesion molecule (NCAM)59–61. In the inflammatory state, soluble adhesion molecules (sCAMs) are often found circulating in the blood presumably after being shed from the activated vascular and immune cells59,61.

Activated glial cells generate significant amounts of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS)62,63. Although these free radicals have been shown to be vital in the immunologic destruction of invading microbial pathogens, these ROS/RNS also cause significant oxidative stress and injury to neurons resulting in intracellular oxidative damage to proteins, DNA and lipids63. There are multiple natural antioxidants, found in vegetables, fruit and wine, which show free radical scavenging activity in chemical assays in vitro, such as the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl-hydrate (DPPH) assay, but it is also vital to demonstrate that these compounds which demonstrate free radical scavenging activity in vitro also demonstrate biologic antioxidant activity in vivo confirming their capacity to protect cells against oxidative stress and injury in living organisms64–67.

Organic polyphenols will often downregulate pro-inflammatory mediators such as inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) via the reduction in the expression of Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase (MAPK)65–67. Some research papers have suggested that ingestion of food polyphenols may provide protection from neurodegenerative disorders68–70.

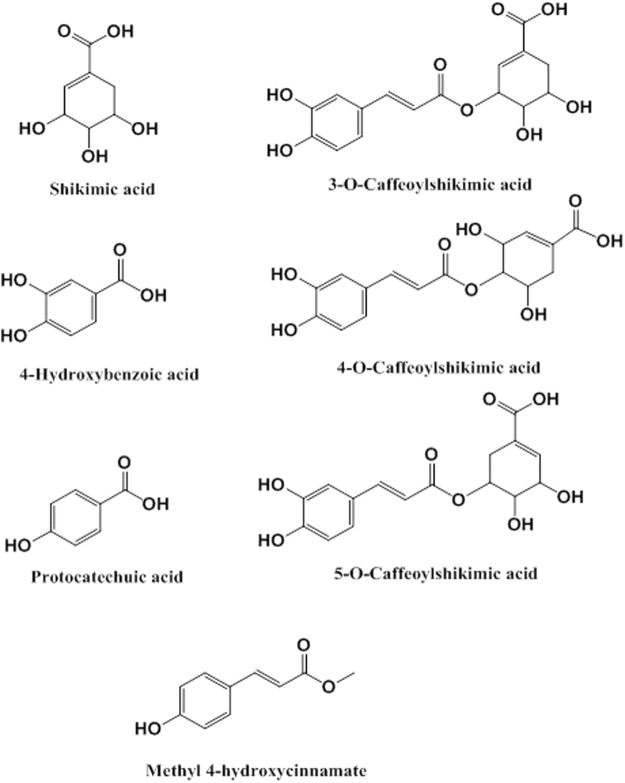

Palm Fruit Bioactives (“PFB”, also known in research literature as Oil Palm Phenolics (“OPP”)) represent a heterogeneous and complex aqueous mixture of water-soluble compounds derived from the fruit of the oil palm (Elaeis guineensis), extracted by the mechanical crushing, steaming and filtering processes as previously described71,72. PFB is rich in antioxidant polyphenols with multiple beneficial cellular and physiologic effects seen both in vivo and in vitro models70–87. The composition of PFB includes multiple organic compounds including protocatechuic acid, shikimic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, methyl-4-hydroxycinnamate and three structural isomers of caffeoylshikimic acid as seen in Fig. 171.

Figure 1.

Some bioactive organic compounds in Palm Fruit Bioactives (PFB). PFB is a complex heterogeneous phytochemical mixture prepared from the aqueous extract of the oil palm fruit.

Multiple research studies show that PFB has diverse physiologic, cellular and biochemical effects which include: anti-inflammatory76,77, antidiabetic78,79, anticancer80,81, anti-angiogenic82, anti-hypertensive83, anti-atherosclerotic84,85, antiviral effects86, anti-chronic degenerative diseases of aging82, and anti-dementia by virtue of their inhibition of the aggregation of beta-amyloid peptide in vitro87. Toxicology studies show PFB to be very safe for oral consumption without any demonstrable toxic, carcinogenic or teratogenic effects88.

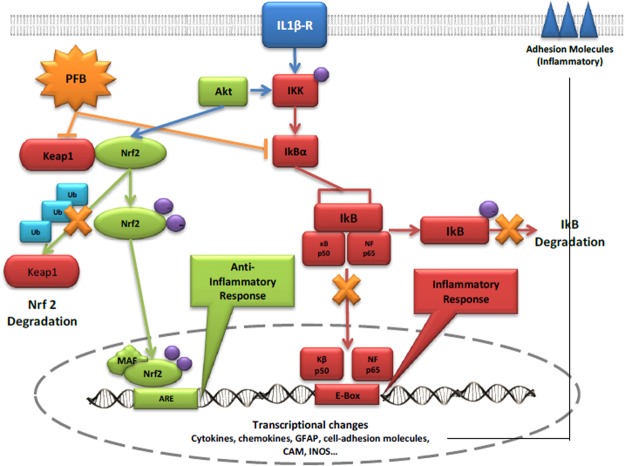

Much research suggests that antioxidants may modulate neuroinflammatory processes in vitro, so we decided to investigate the effects of PFB on reactive astrocytes in vitro. Prior studies by others show that PFB is a potent free radical scavenger and that PFB also upregulates cellular antioxidant gene pathways including Heme oxygenase (HO-1), cysteine reductase, glutathione synthetase73,75,82. In the neurodegenerative diseases, there are dysregulated genetic networks which involve an imbalance between the pro-inflammatory NF-κB pathways and the anti-inflammatory Nrf2 pathways. We have data which show that PFB reduces the NF-κB pathways in the network while it increases the Nrf2 pathways as revealed by RNA-seq (Koledova, Weinberg – unpublished data).

Other studies have shown that PFB and other polyphenols/flavonoids have anti-inflammatory properties by increasing the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase, with focused effects on such cellular targets including macrophages, lymphocytes, endothelial and epithelial cells89. Multiple studies show the presence of chronic oxidative stress preceding several neurodegenerative diseases12,62,63,69. The current research suggests that chronic oxidative stress contributes to DNA damage, lipid peroxidation along with oxidative protein misfolding and aggregation, leading to progression of the disease. Current hypotheses suggest that the reduction of oxidative stress may ameliorate or slow the progression of neurodegenerative disease90.

Other studies show that PFB has neuroprotective effects in animal models70,82. The literature also shows that phenolic compounds and flavonoids, chemically similar to those found in PFB, have marked bioactive anti-inflammatory effects including such well-known antioxidants as curcumin and resveratrol64,89,91.

The typical neuroinflammatory processes result from interactions among various cytokines and chemokines secreted by immune cells, interacting with glial cells and neurons, causing a dysregulation of the CNS-immune-inflammatory network with upregulation of specific cell surface biomarkers such as cell adhesion molecules, and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by glial cells, including astrocytes52. The details of the neuroinflammatory mechanism and interactions within the network of astrocytes-neurons and signaling pathways are still not fully understood.

In this study, we show that PFB has marked effects on astrocytes which have been activated by IL-1β. We measured specific biomarkers in the in vitro assays as surrogates for neuroinflammation. Our data show significant effects of PFB on: the secretion of cytokines and chemokines by the astrocytes, the production of ROS by the astrocytes and by changes in cell surface adhesion molecules expressed by the reactive astrocytes. The present study was undertaken to investigate how PFB may modulate the neuroinflammatory events associated with IL-1β-activated human astrocytes in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Palm Fruit Bioactives

PFB was prepared according to the methods described previously72. PFB is an aqueous extract derived from processed fruit of the African oil palm, Elaeis guineensis, which contains numerous bioactive phytochemical flavonoids and phenols. Among other compounds, PFB contains three isomers of caffeoylshikimic acid, protocatechuic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, methyl-4-hydroxycinnamate and shikimic acid. The detailed composition of PFB has been previously published72. PFB can be prepared as a dried powder via a spray-drying process, in which form it is stored. In this experiment, a 9% aqueous PFB solution (weight/volume) was made from reconstituted spray-dried PFB extract. We then filtered the PFB solution through a 0.2-micron filter (Nalgene filter) prior to use in cell culture. The 9% aqueous PFB solution is equivalent to 2970 ppm Gallic Acid Equivalents (GAE) (as a measure of its reducing capacity in REDOX reactions).

Phenolic fractions of PFB were prepared via liquid-liquid extraction with ethyl acetate. Ethyl acetate and aqueous 9% PFB solution were well-mixed in a 50:50 mixture, then separated. The ethyl acetate fraction was dried and later reconstituted. The extraction was performed twice in succession. The resultant fractions are referred to as the phenolics fraction, partitioned in ethyl acetate, and non-phenolics fraction, partitioned in the aqueous phase. The phenolics fraction contains caffeoylshikimic acids, hydroxybenzoic acid, protacatechuic acid, and other relatively nonpolar compounds, while the nonphenolics fraction contains shikimic acid, soluble fibers, and other compounds. High-performance liquid chromatography was performed on each fraction to confirm separation of phenolic acids. The chromatograms at 280 nm may be found in Additional Fig. 2.

Cell culture of normal human astrocytes

Normal human astrocytes (NHA) were obtained from Lonza Group (Basel, Switzerland, Cat. No. CC-2565) and regularly maintained in cell culture in our laboratory. The NHA were phenotypically characterized using anti-GFAP (anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein) and ~80% of the cells were GFAP-positive (Additional Fig. 1). The NHA were cultured in Astrocyte Growth Media (AGM, Lonza, Cat. No. CC-3186), supplemented with 3% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% L-glutamine, 0.25% insulin, and 0.1% ascorbic acid, gentamicin, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Before treatment, we synchronized cell cycle stages by supernatant exchange with serum-free medium for the following 24 hours. Afterward, medium exchange was performed with fresh AGM. At this time, to induce an inflammatory condition, cells were treated with recombinant human IL-1β (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA) at a concentration of 20 ng/mL as commonly used for the activation of astrocytes19,90,91.

For the treated condition, PFB was added at concentrations of 0, 10, 20, or 40 µL/mL of the stock 9% PFB solution (which is equivalent to 0, 0.9, 1.8, 3.6 mg/mL) simultaneously to medium exchange and IL-1β treatment. In terms of antioxidant capacity, the PFB treatment concentrations may be expressed in terms of Gallic Acid Equivalents (GAE). The equivalent PFB treatment concentrations were 0, 30, 60 and 120 μg GAE/mL. The appropriate negative controls were also conducted, with no induction by IL-1β but with PFB treatment. Following a 24-hour or 96-hour incubation, an aliquot of the supernatant media was collected and stored at −20 °C for future assays (Luminex immunoassay). The cells were harvested, and proteins extracted, and stored at −20 °C for future assay.

Western blotting analysis of Cell Surface Biomarkers

Following 24 hours treatment with IL-1β to activate the astrocytes, with or without PFB, astrocytes were washed twice with ice-cold PBS. Cellular protein was isolated from astrocytes which were lysed using ice-cold Radio-Immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, California, USA). Protein concentrations were determined using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Fifteen micrograms of protein lysate were loaded onto each lane and separated on a 7% polyacrylamide gel. Western blot analysis was performed with the following antibodies: mouse anti-ICAM (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA). The secondary antibodies were obtained from Rockland Immunochemicals Inc. (Limerick, PA). The blots were stripped and re-probed with mouse anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) to determine equivalent loading. The bands were detected on the Li-Cor Odyssey IR Infrared imaging system and analyzed by densitometry using the Li-Cor Image software. The Western blots were done in triplicate for each condition and specimen.

Luminex cytokine and chemokine Multiplexing Immunoassay

Aliquots of cell supernatant at 24 or 96 hours were used for the Luminex bead-array multiplex immunoassay. We used the Milliplex Map Kit (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts USA). The Human Cytokine/Chemokines Magnetic Beat Panel (41-plex), catalogue number HCYTMAG-60K-PX41, was used to quantitatively measure cytokine and chemokine expression and secretion levels in the media collected from astrocytes treated with or without PFB in a range of concentrations in the presence or absence of IL-1β. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This method quantifies soluble particles; in this case, molecules associated with inflammation using a fluorescence-based detection mechanism. The xPONENT 4.1 software was used for acquisition, while analysis was performed using MILLIPLEX Analyst 5.1 (Millipore, USA).

DCFDA Assay for Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

To measure the level of oxidative stress within cells, the reactive oxygen species-sensitive probe 5- and 6-chloromethyl-2′7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA) was used (Abcam, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, Cat. No. ab113851). DCFDA is a cell-permeable, fluorogenic dye that measures hydroxyl, peroxyl and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) activity within the cell. The fluorescence intensity of intracellular DCFDA is a linear indicator of amount of ROS activity in the cells. To detect the accumulation of ROS, astrocyte cultures were incubated with DCFDA at 5 µM for 30 min at 37 °C, washed twice with PBS. After that, astrocytes were treated either with IL-1β at 20 ng/mL alone or with a range of PFB concentrations in the presence or absence of IL-1β for a 24-hour period. The ROS level was measured as a function of the relative fluorescence via excitation and emission spectroscopy at wavelengths of 485 and 535 nm respectively.

Statistical Analysis of the Results

The experiments using cultured astrocytes were performed a minimum of three times. The values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using the Student’s t-test. Results were considered statistically significant if the p-value obtained from the Student’s t-test reached a significance level of p < 0.05.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Mr. Michael J. Keohane of the M.I.T. Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects (COUHES) [http://couhes.mit.edu/] has stated that COUHES review is not required for commercially available, de-identified samples which applies to the Normal Human Astrocytes which we purchased from Lonza, Basel, Switzerland. Thus there was no need to obtain any review or approval of these cell lines which were purchased from Lonza.

Results

Basal cytokine/chemokine profile of human astrocytes

We initially established the basal cytokine/chemokine profile of unstimulated human astrocytes. The basal expression of 37 cytokines/chemokines secreted by the cultured astrocytes incubated without cytokine IL-1β (unstimulated) were measured at two time points: 24 hours (Table 1) and 96 hours (Table 2). At 24 hours, we were able to detect 20 out of 37 cytokines and chemokines: eotaxin, fractalkine, G-CSF, GM-CSF, GRO, IFNα2, IFNγ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12 (p40), IP-10, MCP-3, MDC, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, PDGF-AA, RANTES, ScD40L, TGFα, TNFα. At 96 hours, 5 cytokines/chemokines were detected (FGF-2, IL-1α, IL-7, IL-12(p70), PDGF-AB/BB) in addition to the same 20 cytokines/chemokines detected at 24 hours.

Table 1.

Cytokines/chemokines secreted by human astrocytes at 24 hours with/without IL-1β activation.

| Protein | Gene location that encodes protein | 24 h protein concentration Avg ± 1 STD (pg/mL) |

24 h IL-1β stimulation fold change (ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|

| G-CSF | 17q21.1 | 10.4 ± 7.7 | 570.1* |

| GM-CSF | 5q31.1 | 4.5 ± 1.8 | 574.6* |

| RANTES | 17q12 | 4.0 ± 0 | 395.4*** |

| GRO | 4q13.3 | 78.8 ± 40.9 | 197.5* |

| IL-8 | 4q13.3 | 147.6 ± 72.6 | 97.9*** |

| TNFα | 6p21.33 | 3.2 ± 0 | 46.5* |

| IL-6 | 7p15.3 | 579.2 ± 312.4 | 23.2* |

| MIP-1β | 17q12 | 3.9 ± 0 | 22.5* |

| IP-10 | 4q21.1 | 28.0 ± 17.0 | 20.1* |

| Eotaxin | 17q12 | 4.5 ± 0.0 | 7.4* |

| MIP-1α | 17q12 | 27.1 ± 0.5 | 5 |

| MCP-3 | 17q12 | 20.1 ± 2.2 | 3.1 |

| IFNα2 | 9p21.3 | 9.1 ± 2.7 | 4.6 |

| Fractalkine | 16q21 | 54.1 ± 17.2 | 2.5* |

| IFNγ | 12q15 | 4.4 ± 2.2 | 2.4 |

| IL-12(p40) | 5q33.3 | 6.2 ± 3.6 | 1.7 |

| TGFα | 2p13.3 | 40.4 ± 30.3 | 1.3 |

| MDC | 16q21 | 4.8 ± 2.5 | 1.3 |

| sCD40L | Xq26.3 | 8.2 ± 3.3 | 1.1 |

| PDGF-AA | 7p22.3 | 155.5 ± 7.5 | 0.8 |

| IL-12(p70) | 3Q25.33 AND 5q33.3 | <3.2 | Abs 10.4 ± 5.2 |

| IL-1α | 2q14.1 | <2.7 | Abs 7.3 ± 1.6 |

| IL-7 | 8q21.13 | <3.2 | Abs 24.8 ± 17.9 |

| PDGF-AB/BB | 7p22.3 & 22q13.1 or 22q13.1 & 22q13.1 | <22.0 | Abs 24.4 ± 18.8 |

| FGF-2 | 4q28.1 | <40.5 | Abs 57.5 ± 20.3 |

| Flt3L | 19q13.33 | ND | ND |

| IL-2 | 4q27 | ND | ND |

| IL-3 | 5q31.1 | ND | ND |

| IL-5 | 5q31.1 | ND | ND |

| IL-9 | 5q31.1 | ND | ND |

| IL-10 | 1q32.1 | ND | ND |

For each cytokine, values are the mean concentration +/− standard deviation for the unstimulated condition and as fold-change ratios for the IL-1β-stimulated condition. The inflammatory profile (bolded text) consists of the secreted cytokines/chemokines altered in production with IL-1β stimulation as compared to their basal expression levels. Student’s t-test using absolute values, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Table 2.

Cytokines/chemokines secreted by human astrocytes at 96 hours with/without IL-1β activation.

| Protein | Gene location that encodes protein | 96 h protein concentration Avg ± 1 STD (pg/mL) | 96 h IL-1β stimulation fold change (ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RANTES | 17q12 | 22.2 ± 12.6 | 227.7** |

| IP-10 | 4q21.1 | 34.0 ± 20.7 | 80.8* |

| GM-CSF | 5q31.1 | 253.1 ± 376.1 | 27.3* |

| GRO | 4q13.3 | 699.6 ± 486.3 | 21.1* |

| G-CSF | 17q21.1 | 463.1 ± 561.2 | 23.7 |

| MIP-1α | 17q12 | 24.4 ± 5.0 | 20.5 |

| TNFα | 6p21.33 | 18.0 ± 17.5 | 10.2* |

| IL-8 | 4q13.3 | 1581.5 ± 1289.7 | 7.2 |

| MCP-3 | 17q12 | 82.6 ± 79.7 | 6.4** |

| MIP-1β | 17q12 | 18.2 ± 8.8 | 5.2* |

| IL-6 | 7p15.3 | 3980.1 ± 3442.9 | 4.0* |

| IL-1α | 2q14.1 | 8.2 ± 1.3 | 3.6 |

| IFNα2 | 9p21.3 | 23.3 ± 9.4 | 2.4* |

| sCD40L | Xq26.3 | 5.9 ± 2.6 | 2.1 |

| Fractalkine | 16q21 | 101.1 ± 49.1 | 2** |

| TGFα | 2p13.3 | 63.6 ± 43.1 | 1.9 |

| Eotaxin | 17q12 | 31.1 ± 28.8 | 1.5 |

| IL-12(p40) | 5q33.3 | 8.8 ± 3.1 | 1.4 |

| IL-12(p70) | 3Q25.33 AND 5q33.3 | 6.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 |

| PDGF-AB/BB | 7p22.3 & 22q13.1 or 22q13.1 & 22q13.1 | 157.7 ± 110.0 | 1.4 |

| IFNγ | 12q15 | 5.7 ± 2.0 | 1.3 |

| MDC | 16q21 | 5.4 ± 1.6 | 1.2 |

| PDGF-AA | 7p22.3 | 2183.2 ± 2002.0 | 1.2 |

| IL-7 | 8q21.13 | 29.5 ± 3.5 | 1.1 |

| FGF-2 | 4q28.1 | 68.6 ± 26.5 | 1.1 |

| Flt3L | 19q13.33 | ND | ND |

| IL-2 | 4q27 | ND | ND |

| IL-3 | 5q31.1 | ND | ND |

| IL-5 | 5q31.1 | ND | ND |

| IL-9 | 5q31.1 | ND | ND |

| IL-10 | 1q32.1 | ND | ND |

Values are given as average concentrations +/− standard deviation for the unstimulated condition and as fold-change ratios for the IL-1β-stimulated condition. The inflammatory profile (bolded text) consists of the secreted cytokines/chemokines with significant changes upon IL-1β stimulation as compared with their basal expression levels as based on significant difference. Student’s t-test using absolute values, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

At 24 hours, of the 20 detected cytokines/chemokines, 10 analytes were found in concentrations less than 10 pg/mL (eotaxin, GM-CSF, IFNα2, IFNγ, IL-12 (p40), MDC, MIP-1β, RANTES, sCD40L, TNFα). There were 7 analytes between concentrations 10 and 100 pg/mL (fractalkine, G-CSF, GRO, IP-10, MCP-3, MIP-1α, TGFα), and 2 analytes were found in concentrations between 100 and 500 pg/mL (IL-8, PDGF-AA), and 1 analyte was above concentration 500 pg/mL (IL-6) (Table 1).

At 96 hours, of the 25 detectable cytokines and chemokines, 6 analytes were found in concentrations less than 10 pg/mL (IL-1α, sCD40L, IFNγ, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), MDC), 11 analytes were in concentration range 10 to 100 pg/mL (Eotaxin, FGF-2, IFNα2, IL-7, IP-10, MCP-3, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, TGFα,TNFα), 4 analytes were detected in concentrations between 100 and 500 pg/mL (Fractalkine, G-CSF, GM-CSF, PDGF-AB/BB), and 4 analytes were found in concentrations above 500 pg/mL (GRO, IL-6, IL-8, PDGF-AA) (Table 2). More individual cytokines/chemokines were detected at 96 h than 24 h, indicating increased levels of expression.

Cytokine profile of human astrocytes with IL-1β stimulation

Following 24-hour exposure to IL-1β, 11 cytokines/chemokines were significantly increased compared to controls (eotaxin, fractalkine, G-CSF, GM-CSF, GRO, IL-6, IL-8, IP-10, MIP-1β, RANTES, TNFα). In Table 1, the analytes that were significantly changed by IL-1β stimulation at 24 h, along with analytes present but not significantly changed by IL-1β stimulation, are shown based on fold change. The absolute cytokine/chemokine concentrations are located in Additional Table 1.

Following 96-hour exposure to IL-1β, 10 cytokines showed significantly increased expression: fractalkine, GM-CSF, GRO, IFNα2, IL-6, IP-10, MCP-3, MIP-1β, RANTES, and TNFα (Table 2). There was no correlation between the basal levels of cytokine expression in unstimulated astrocytes compared with the IL-1β-stimulated levels of cytokine expression.

There were 6 cytokines/chemokines that were not detectable in the basal unstimulated condition but were only detectable after IL-1β stimulation. These include IL-13, IL-15, IL-17a, IL-1RA, IL-4, TNFβ (Table 3). Many of these cytokines/chemokines had concentrations less than 10 pg/mL (including IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-15 IL-17a, TNFβ). IL-4 had a concentration in the range 10 to 100 pg/mL (Table 3). Several cytokines/chemokines were not detected in any condition (FLT3L, IL-2, IL-3, IL-5, IL-9, IL-10) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 3.

Cytokines/chemokines which are secreted by human astrocytes only upon IL-1β activation.

| Protein | Gene location that encodes protein | 24 h protein concentration with IL-1β stimulation Avg ± 1 STD (pg/mL) |

96 h protein concentration with IL-1β stimulation Avg ± 1 STD (pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-4 | 5q31.1 | Abs 15.6 ± 2.0 | Abs 21.9 ± 8.1 |

| IL-13 | 5q31.1 | Abs 5.4 ± 0.8 | Abs 7.1 ± 0.3 |

| IL-15 | 4q31.21 | Abs 3.9 ± 0.7 | Abs 11.5 ± 5.2 |

| IL-17A | 6p12.2 | Abs 4.5 ± 2.1 | Abs 5.1 ± 1.9 |

| IL-1RA | 2q14.1 | Abs 17.9 ± 0.9 | Abs 14.5 ± 14.5 |

| TNFβ | 6p21.33 | Abs 4.5 ± 1.8 | Abs 4.7 ± 2.2 |

Cytokine concentrations are the average concentration +/− standard deviation. These cytokines were only detectable upon IL-1β-stimulation, and we consider them to be part of the inflammatory profile.

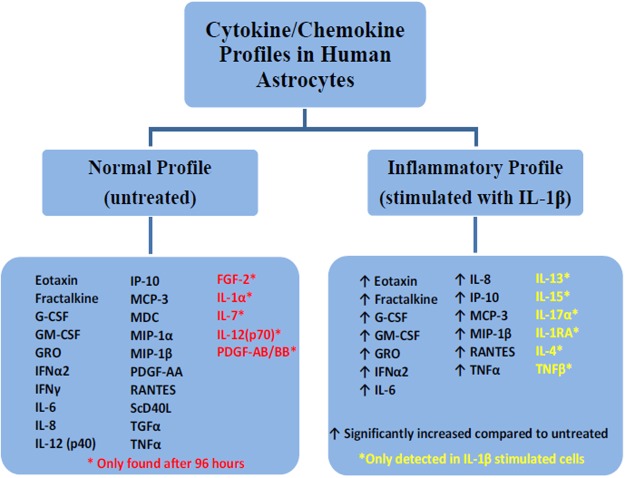

When comparing the unstimulated NHA with the IL-1β-stimulated NHA, distinct subsets of the cytokines and chemokines became apparent. There appear to be two distinct profiles of cytokine/chemokine production. We define the normal profile of cytokines/chemokines as those detected in the untreated condition which are not significantly changed upon stimulation with IL-1β. We define the inflammatory profile of cytokines/chemokines to include those which are significantly increased upon IL-1β stimulation as well as those which are not detected in unstimulated NHA but are detected upon IL-1β stimulation (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Profiles of cytokines/chemokines produced by human astrocytes with/without IL-1β stimulation reveal 2 profiles: normal (basal) and inflammatory (post-IL-1β) The inflammatory profile consists of those secreted cytokines/chemokines which were significantly altered with IL-1β stimulation compared to their basal expression levels at 24 h or 96 h, while the normal profile consists of those cytokines/chemokines detectable in the basal state.

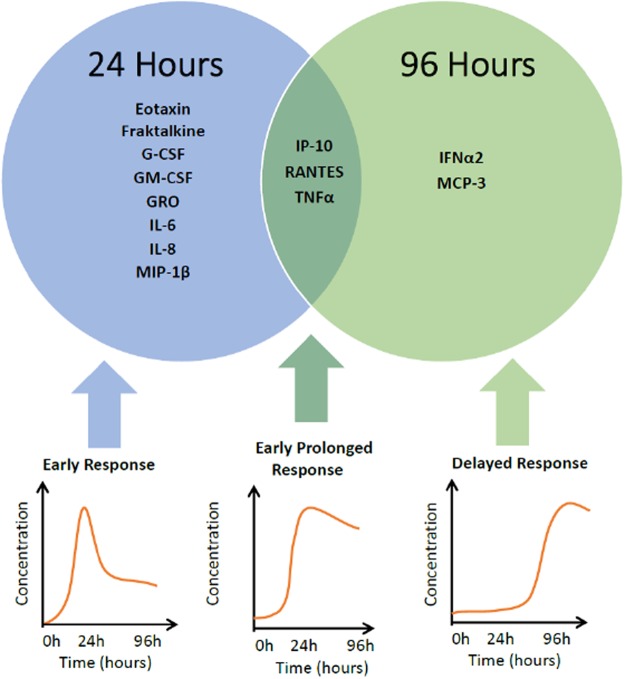

When comparing the temporal dynamics of the 24-hour levels and the 96-hour levels of the IL-1β-stimulated groups, the cytokines and chemokines fall into three distinct groups (Fig. 3). The first group represents those cytokines/chemokines which are markedly increased during the first 24-hour period following IL-1β stimulation and then quickly decrease by the 96-hour measurement. These include eotaxin, fractalkine, G-CSF, GM-CSF, GRO, IL-6, IL-8, MIP-1β. We call this first group the early-short response group.

Figure 3.

Time-dependent differential expression of cytokines/chemokines induced by IL-1β stimulation in human astrocytes. Cytokines induced within 24 hours are designated “early short response.” Cytokines produced after 96 hours of induction are designated “delayed response.” Cytokines induced within 24 h which remain elevated at 96 hours are designated “early-prolonged response”.

The second group of cytokines/chemokines remain near basal levels for the first 24-hours post-IL-1β stimulation but then show a marked increase from the 24-hour time measurement to the 96-hour measurement. These include IFNα2 and MCP-3. We call this group the strong-delayed response group.

Finally there is the third type of cytokines/chemokines which show marked increase during the first 24 hours post–IL-1β stimulation and remain high through the 96-hour time measurement. These cytokines/chemokines include IP-10, RANTES and TNFα. We call this group the early-prolonged group.

Effect of PFB on the basal cytokine profile of human astrocytes

PFB has no significant effect on the cytokine/chemokine profile of astrocytes which are not activated by IL-1β. Data is shown in Additional Table 2 (24 hours) and Additional Table 3 (96 hours).

Effect of PFB on the profile of IL-1β-stimulated human astrocytes

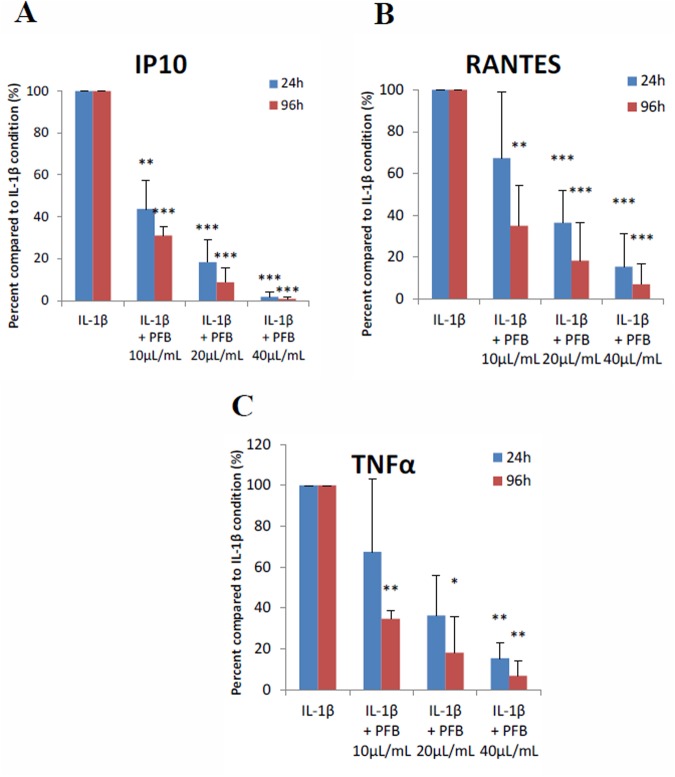

PFB has a marked effect on the production of cytokines/chemokines which belong to the inflammatory profile, i.e. the group of 13 cytokines/chemokines which were significantly elevated in astrocytes stimulated with IL-1β. A significant decrease is seen in the levels of 3 cytokines/chemokines in the inflammatory profile after 24 hours of treatment with PFB: RANTES, IP-10 and TNFα. An even greater decrease was observed in the levels at 96 hours. These results were confirmed three times on subsequent passages of NHA, in duplicate for each passage. The individual values for each passage are listed in Additional Table 4. The different passages of NHA expressed varying levels of cytokine/chemokine concentration. All passages of NHA possessed the exact same tendency to decrease production of RANTES, IP-10, and TNFα in response to PFB treatment. We note that these cytokines/chemokines belong to the early and prolonged response group mentioned previously (Fig. 3).

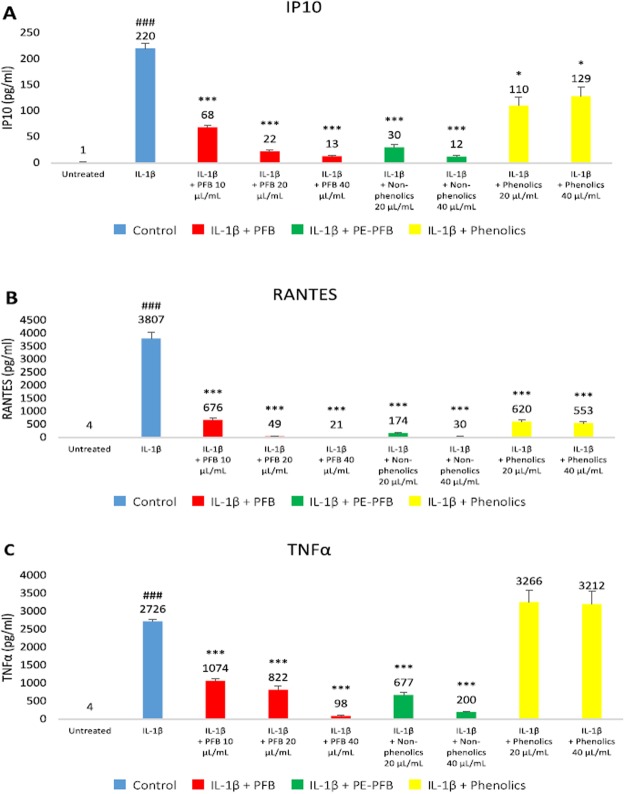

To summarize the results of our analysis, we calculated the mean percent change. Figure 4 shows that in NHA stimulated by IL-1β, a significant decrease in production of RANTES, IP-10, and TNFα after 24 hours and an even greater decrease in production at 96 hours occurred in the presence of PFB in a dose-dependent manner (absolute cytokine/chemokine levels may be seen in Additional Table 4). With PFB exposure, IP-10 expression was reduced to levels equivalent to normal, non-stimulated NHA; a similar effect was observed in expression levels of RANTES and TNFα: exposure to PFB markedly decreased their expression in IL-1β-stimulated NHA, reducing them toward normal basal levels. In addition, a reduction in the expression of MCP-3, GM-CSF, G-CSF and MIP-1β was observed, but this was not a statistically significant.

Figure 4.

(A) IP-10, (B) RANTES, and (C) TNFα secretion levels induced in NHA by IL-1β stimulation (20 ng/ml) are significantly reduced with exposure to Palm Fruit Bioactives at 24 and 96 hours in a dose-dependent manner. The normalized percent change (%) for each PFB treatment condition compared with the positive control, IL-1β stimulation alone, for each time point. Data represent the mean percentage change ± SD of three Luminex replicates (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Reduction of IP-10 by PFB exposure in IL-1β-stimulated NHA

These results show that in IL-1β-stimulated NHA, IP-10 expression was decreased by 56% and 69% at 24 and 96 hours exposure, respectively, in the presence of PFB at a concentration of 10 μL/mL; an even greater decrease was observed at higher concentrations. At a PFB concentration of 20 μL/mL, IP-10 was decreased by 81% and 91% at 24 and 96 hours, respectively, and at a PFB concentration of 40 μL/mL, IP-10 was decreased by 98% and 99% respectively, restoring IP-10 toward the normal basal levels for NHA (Fig. 4a).

Reduction of RANTES by PFB exposure in IL-1β-stimulated NHA

These results show that in IL-1β-stimulated NHA, RANTES expression was decreased by 65% at 96 hours post-exposure to PFB at a concentration of 10 μL/mL; the reduction in RANTES was not significant at 24 hours (Fig. 4b). A greater reduction in RANTES expression was observed at higher concentrations of PFB exposure. At a PFB concentration of 20 μL/mL, RANTES was decreased by 64% and 82% at 24 and 96 hours, respectively, and for a PFB concentration of 40 μL/mL, RANTES was decreased by 85% and 93% respectively. Exposure to PFB greatly reduced RANTES levels in IL-1β-stimulated NHA.

Reduction of TNFα by PFB exposure in IL-1β-stimulated NHA

These results also show that TNFα expression was decreased in IL-1β-stimulated NHA with PFB exposure. At 24 hours of exposure, we observed a tendency toward lower expression at PFB concentrations of 10 μL/mL and 20 μL/mL, but these differences were not statistically significant. There was a significant reduction in TNFα expression when in the presence of 40 μL/mL of PFB. Exposure to PFB 40 μL/mL decreased TNFα production by 81% at 24 hours (Fig. 4c). At 96 hours of exposure, TNFα expression was decreased by 57% with PFB at a concentration of 10 μL/mL. A greater decrease in TNFα expression was observed at higher concentrations of PFB. At a PFB concentration of 20 μL/mL, TNFα was decreased by 66% and at a PFB concentration of 40 μL/mL, TNFα was decreased by 94%. Exposure to PFB greatly reduced TNFα levels in IL-1β-stimulated NHA, by the 96 hour time measurement.

Comparison of phenolic with non-phenolic fractions of PFB on IP10, RANTES and TNFα

Several of the organic compounds in PFB can be classified as either phenolic or non-phenolic. We wanted to compare the relative contributions of phenolic compounds versus non-phenolics, so we fractionated the PFB. Additional Fig. 2 shows the chromatograms for the phenolic fraction and the non-phenolic fraction. After determining that PFB shows a dose-dependent reduction of IP10, RANTES and TNFα, we tested the relative potency of the PFB fractions including the phenolic and non-phenolic fractions. In Fig. 5, we see that the non-phenolic fraction shows similar potency as the unfractionated PFB. The phenolic fraction shows no significant effect on TNFα, moderate effect on IP10 reduction, and the greatest effect on RANTES reduction, but still less than the unfractionated PFB. This suggests that other non-phenolic compounds play a greater role in this cytokine/chemokine reduction than the phenolic fraction of PFB.

Figure 5.

Effects of phenolic vs. non-phenolic fractions of PFB on (A) IP10, (B) RANTES, and (C) TNFα levels in IL-1β-stimulated NHA. Concentrations of IP10, RANTES, TNFα for untreated and IL-1β stimulated controls, and IL-1β for different treatment conditions: PFB, non-phenolic PFB fraction, and phenolic PFB fraction at 20 and 40 μL/mL concentrations for each condition. Mean and standard deviation given for three replicates. Student’s t-test, ###p < 0.001, untreated vs. IL-1β stimulation; ***p < 0.001, IL-1β vs. IL-1β + PFB or PFB fraction.

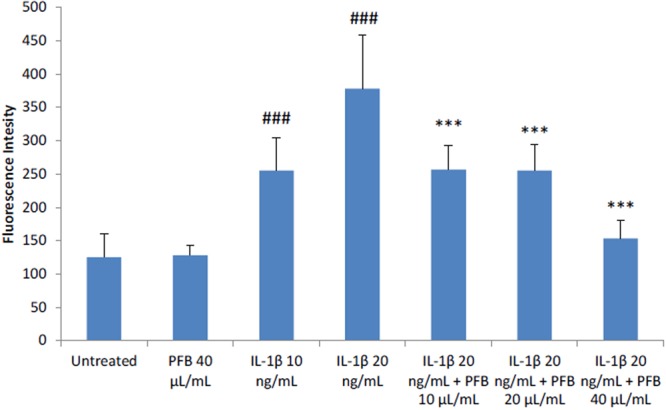

Effect of PFB on production of ROS by IL-1β-stimulated human astrocytes

The production of ROS by NHA was measured by a DCDFA assay in seven experimental groups: unstimulated, unstimulated treated with PFB (40 μL/mL), stimulated with IL-1β (10, 20 ng/mL), and stimulated with IL-1β (20 ng/mL) with PFB treatment (10, 20, 40 μL/mL). 24-hour exposure of PFB alone has no effect on ROS production by astrocytes. IL-1β causes a dose-dependent increase in ROS production (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Elevated Reactive Oxygen Species production in NHA stimulated by IL-1β is reduced by treatment with Palm Fruit Bioactives, as measured by DCFDA Assay after 24 h. No change is observed between ROS production between untreated NHA and the highest concentration of PFB treatment used, while increased ROS production from stimulation is decreased by PFB. Fluorescence intensity correlates with level of oxidative stress per condition in the DCDFA Assay. Values given as mean fluorescence intensity +/− standard deviation of three replicates. Student’s t-test, ###p < 0.001, untreated control vs. IL-1β; ***p < 0.001, IL-1β vs. PFB-X + IL-1β, where X is treatment concentration of PFB.

Interestingly, when PFB was present in combination with IL-1β, a marked decrease in ROS production was observed as compared with the NHA treated only with IL-1β (Fig. 6). PFB treatment in concentrations of 10 and 20 μL/mL had approximately the same effect on ROS production in IL-1β (20 ng/mL) stimulated NHA. In both cases, the production of ROS was reduced toward the level of ROS measured in NHA treated with IL-1β at a concentration of 10 ng/mL, and these levels were lower than the the levels of ROS measured in NHA treated with IL-1β at a concentration of 20 ng/mL. The greatest decrease in ROS production in IL-1β-treated NHA (20 ng/mL) was observed at the highest treatment concentration of PFB (40 μL/mL); ROS levels were observed to be close to the level seen in untreated cells. Overall, PFB reduced ROS production in IL-1β stimulated NHA.

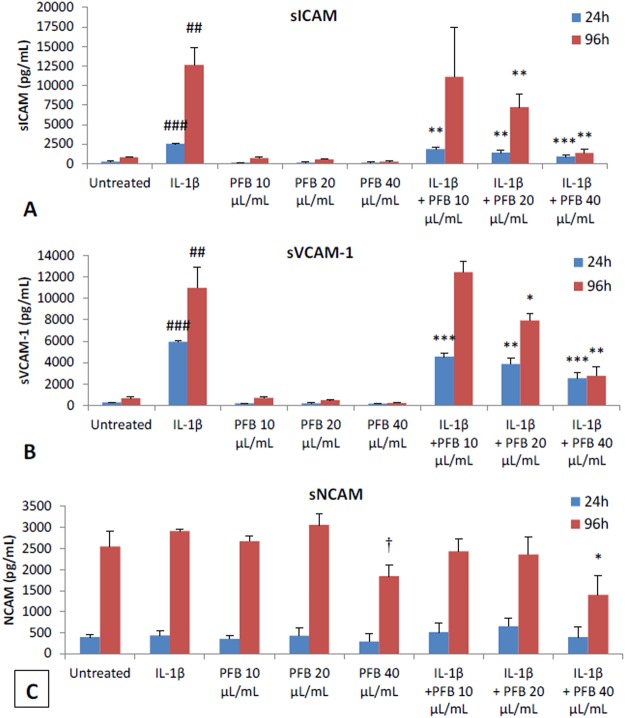

Effect of PFB on Astrocyte Cell Adhesion Molecules

After NHA were activated by incubation with IL-1β for either 24 or 96 hours and subsequently were treated with a range of PFB concentrations (0, 10, 20, 40 μL/mL), the expression of cell adhesion molecules ICAM, sICAM, sVCAM, and sNCAM was measured. sICAM, sVCAM, and sNCAM expression was measured by Luminex immunoassay (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Effect of PFB on soluble adhesion molecules expressed by NHA with 24 h or 96 h stimulation with IL-1β. (A,B) PFB exposure decreased siCAM and sVCAM expression in both unstimulated and IL-1β-stimulated NHA. (C) NCAM expression did not differ upon exposure to IL-1β. Values given as cytokine concentration, mean +/− SD. Experiment was performed in triplicate. ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, untreated control vs. IL-1β; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, IL-1β vs. PFB-X + IL-1β.

Effect of PFB on soluble adhesion molecules (sICAM, sVCAM, sNCAM)

The astrocytes also shed a soluble form of ICAM (sICAM) as well as soluble adhesion molecules sVCAM and sNCAM into the culture supernatant. These soluble adhesion molecules were measured using the multiplex Luminex immunoassay magnetic bead array assay. The results show that PFB causes a statistically significant reduction in the levels of of sICAM and sVCAM at 24 hours with an even greater reduction at 96 hours (Fig. 7). There was no significant effect with IL-1β stimulation in expression of sNCAM.

There is a dose-dependent modulation of the expression of sICAM and sVCAM seen at 24 hours with PFB treatment. This modulation by PFB treatment is even greater at 96 hours. There were no marked effects of PFB treatment on expression of sNCAM. The greatest decrease in expression of sICAM and sVCAM occurred with the highest PFB treatment concentration (40 μL/mL).

IL-1β-activated human astrocytes show marked upregulation of multiple biomarkers and with the release of multiple inflammatory mediators. We show significant inhibition of these functions by simultaneously co-incubating the astrocytes with PFB and IL-1β. PFB causes a dose-dependent and time-dependent reduction in specific cytokines TNFα, RANTES, and IP-10.

Our results also show that PFB significantly reduces ROS production by IL-1β-activated astrocytes. Activated astrocytes normally express increased levels of cell adhesion molecules. PFB reduces the expression of ICAM and VCAM, both in activated and naïve human astrocytes in vitro.

Discussion

Recent studies have focused on the important role of dysfunctional astrogliosis in neurologic disease12,15,17,19,92,93. These studies have pointed to the importance of activated astrocytes as a therapeutic target. Astrocytes play a key role in signaling in both the innate and adaptive immune responses12,20,22,23. A key component of this signaling process involves the production and release of cytokines, chemokines and other inflammatory mediators including reactive oxygen species19,52,53,57,92,93. Physiologically these signaling pathways play a protective role in fighting CNS infections and tumors19,92. However, when excessive, chronic or dysregulated, these signaling mediators may initiate a dysregulated, pathologic or autoimmune response19,93–105. These dysregulated responses cause significant neuronal injury and death and may lead to neurodegenerative disorders.

Based on prior data showing that PFB reduces the expression of NF-κB80, we decided to investigate the effects of PFB on cytokine/chemokine secretion by IL-1β-activated astrocytes to explore the immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects under these conditions. Our data show that there are several distinct subsets of cytokine/chemokine profiles based on temporal expression and responsiveness to IL-1β. We identified the basal profile as those cytokines/chemokines expressed by unstimulated NHA in the basal state and the inflammatory profile as those cytokines/chemokines which are expressed de novo after stimulation with IL-1β as well as those which are significantly upregulated following IL-1β stimulation (Fig. 2).

The inflammatory profile of cytokines/chemokines demonstrates distinct patterns of temporal expression with IL-1β incubation at the 24-hour and 96-hour time points. The kinetics for the expression of the cytokines/chemokines reveal 3 distinct groups: (1) the early-short response, (2) the delayed response and (3) the early-prolonged response. The early-short response cytokines reach maximum expression at 24 hours and then decrease; these include eotaxin, fractalkine, G-CSF, GM-CSF, GRO, IL-6, IL-8, and MIP-1β. The delayed response cytokines reach maximum expression at 96 hours, and include MCP-3 and IFNα2. The early-prolonged response cytokines reach maximum response at 24 hours and remain elevated at 96 hours. These include IP-10, RANTES, and TNFα.

These results show that PFB has no significant effect on the early-short response or the delayed-response cytokines. However, we do observe slight reductions in the expression of G-CSF, GM-CSF, MCP-3, and MIP-1β, but these are not statistically significant. The most prominent cytokine effect of PFB is its significant reduction of the expression of the early-prolonged cytokines IP-10, RANTES, and TNFα in a dose-dependent manner. These cytokines have been demonstrated to play a crucial role in such neurodegenerative diseases. It is well-established that IP-10, RANTES, and TNFα are significantly increased in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Multiple Sclerosis (MS), HIV-associated dementia and Neuropathic Pain Syndrome96–115.

TNFα plays a key role in AD pathogenesis114. TNFα induces significant production of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), neuronal stress and dysfunction leading to neuronal death115. It is well established that activated astrocytes synthesize and release TNFα, which stimulates increased expression of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by glial cells116–118, and also upregulates the conversion of APP into the pathologic variants of beta-amyloid119–121. The current belief is that reducing the level of TNFα may be beneficial in neuro-inflammatory conditions. As our results show that PFB reduces the secretion of TNFα by activated astrocytes, we expect that it may have a beneficial action in pathologies such as Alzheimer’s, where TNFα plays a key role in early dysfunction.

Elevated levels of TNFα are found in the brain and CSF of patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and mouse models of PD107,122. The importance of TNFα-induced signaling in the pathogenesis of PD is corroborated in multiple animal models of PD including Parkinsonian syndrome induced by the neurotoxins MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) and rotenone, which simulate the TNFα-signaling seen clinically in patients with PD123–125. In a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the progression of neurodegeneration is accompanied by elevation of TNFα mRNA transcripts and protein in the reactive microglia found in the spinal cord105,111,126. Relapses of multiple sclerosis (MS) are accompanied by increased production of both TNFα and IFNγ127,128. TNFα induces apoptotic death in oligodendrocytes129 and also decreases the uptake of glutamate by astrocytes, which may further damage the oligodendrocytes130.

Multiple studies show that reactive oxygen species (ROS) appear to play an important role in the pathogenesis of neuro-inflammatory conditions62,63,90. Our results show that PFB, also a potent antioxidant, reduces TNFα, ROS and RANTES release from IL-1β-stimulated astrocytes. RANTES and its related receptors play a key role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease96. Patients with AD have elevated levels of RANTES and its receptors (CCR5) in their brains93,96. AD lesions in the brain are associated with RANTES and its receptors. Multiple studies have suggested that RANTES indirectly mediates neuronal injury128. Some studies suggest that upregulation of RANTES may have a neuroprotective role131–135.

The clinical severity of Parkinson’s disease (PD) correlates with the serum level of RANTES132. The antibody neutralization of RANTES in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease, MPTP-intoxicated mice, prevents the loss of dopaminergic neurons136. Patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) have elevated levels of RANTES in their serum and cerebrospinal fluid100. The RANTES chemokine has been detected in brain lesions of patients with MS134. The CSF level of RANTES correlates well with the degree of neuroinflammation and the cortical synaptic excitability in patients with multiple sclerosis134,137.

In Alzheimer’s disease, the astrocytes express elevated levels of IP-10138. Injecting Aβ peptide into the mouse brain causes causes a marked increase in the secretion of IP-10 by the astrocytes139. Activated human astrocytes show enhanced production of IP-10, and both IP-10 and CXCR3 are upregulated in the brains of patients with AD138. The IP-10 levels correlate well with the clinical severity of disease in Parkinson’s patients102. Alpha-synuclein further increases the expression of IP-10 in the context of IL-1β-stimulated astroglial culture140. IP-10 has been demonstrated to be toxic to neurons, such as in the cell line LAN-2 and mixed human fetal neurons141.

IP-10 is also elevated in the CSF of MS patients137. Astrocytes in MS lesions express higher levels of IP-10137,142. Both serum and CSF levels of IP-10 are higher in MS patients with acute disease compared with those with stable disease103,137,143.

In summary, our data show that PFB significantly reduces the secretion of TNFα, RANTES and IP-10 by normal human astrocytes which have been activated by IL-1β. These 3 cytokines/chemokines belong to the early-prolonged response temporal group, which increase rapidly in the first 24 hours of exposure to PFB and remain elevated for at least 96 hours. There is extensive research literature which shows the importance of these 3 cytokines/chemokines in the pathogenesis and progression of neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Multiple sclerosis, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, HIV-induced dementia and several viral encephalitides.

Thus, TNFα, RANTES and IP-10 along with their receptors provide potential targets for drug intervention in combatting chronic neurodegenerative conditions due to the pivotal role these cytokines/chemokines play in the signaling networks, NF-κB versus Nrf2 transcriptional pathways and the known astrocyte-neuron system dynamics. Therefore, the effects of PFB on reducing these early-prolonged response cytokines/chemokines suggest that PFB may be effective in preventing or delaying the progression of the neuro-inflammation mediated by activated astrocytes. Based on this data, PFB may play a potentially beneficial role in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, MS and ALS via its reduction of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IP-10 and RANTES. The secretion of these three cytokines is transcriptionally regulated by NF-κB in astrocytes53. Our prior studies show that PFB downregulates the expression of the transcription factor NF-κB80, which may explain the reduction in expression of TNFα, IP-10 and RANTES by PFB in the IL-1β-stimulated astrocytes.

When comparing the phenolic versus the non-phenolic fractions of PFB, our data show that the non-phenolics fraction shows similar potency as the unfractionated PFB. The phenolics fraction shows no significant effect on TNFα, moderate effect on IP10 reduction, and the greatest effect on RANTES reduction, but still less than the unfractionated PFB. This suggests that other compounds play a greater role in this cytokine/chemokine reduction than do the phenolics fraction of PFB or that there may be some combinatorial/synergistic effect between the phenolics and non-phenolics in the PFB mixture.

Activated astrocytes and microglia, which produce ROS and NO, are seen in the substantia nigra of PD brains144. Usually mammalian cells will degrade physiologic levels of ROS/RNS through enzymatic reactions involving native cellular antioxidants/reducing agents such as glutathione. However, increased oxidative stress generates excessive levels of peroxyl radicals, hydroxyl radicals, superoxide anions, and peroxynitrites which cannot be easily degraded and require the consumption of direct antioxidants to scavenge them.

Prior studies of PFB measured the free radical scavenging activity using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) reagent71,73,75–77. When activated by misfolded proteins, such as amyloid-β and α-synuclein, astrocytes generate ROS/RNS, which cause significant oxidative stress resulting in the significant neuronal injury and death underlying the pathology of the neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases145–148. The activated astrocytes produce excessive levels of ROS and NO in the CNS.

Our results show that PFB reduces the intracellular levels of ROS in activated astrocytes as measured by the DCDFA assay. This study shows that PFB has no effect on the basal level of ROS in resting astrocytes. IL-1β induces dose-dependent increases in the levels of ROS during astrocyte activation. PFB causes a dose-dependent reduction in the intracellular levels of ROS in activated astrocytes. There are 2 possible explanations for this reduction of ROS. PFB may directly act as a scavenger for ROS, as shown in prior studies. PFB may modulate the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD), which facilitates the breakdown of free radical superoxide and hydrogen peroxide147, which plays an important role in maintaining the normal cellular redox status148.

The neuroinflammatory process seen in neurodegenerative diseases is characterized by the activation of astrocytes, which show increased expression of ICAM along with the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines60,61. The cellular adhesion molecules, upregulated in IL-1β-activated astrocytes, including ICAM, VCAM and NCAM, are potential biomarkers for the detection of the neuroinflammation seen in the neurodegenerative diseases59.

Studies show that reduction of the level of expressed ICAM on activated astrocytes correlates with reduced levels of aggregated beta-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease3. The pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β causes increased levels of expression of ICAM in the CNS149,150. We show that PFB down-regulates the expression of ICAM on IL-1β-activated human astrocytes in vitro in a dose-dependent and time-dependent manner and this is accompanied by the reduced secretion of cytokines and chemokines. These cytokines and chemokines normally play an important role in the neuronal injury seen during neuroinflammation.

Our data also show that PFB reduces the secretion of sICAM and sVCAM. This is further evidence that PFB causes modulation and down-regulation in the activation of human astrocytes in vitro. The activation of astrocytes is a key process underlying the neuroinflammatory processes seen in the neurodegenerative diseases. Prior studies by our group showed that PFB also blocks the TNF-induced activation of NF-κB (Kang, unpublished data), and thus it is possible that PFB suppresses the expression of these adhesion molecules by inhibiting the activation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB in response to TNFα, and LPS. Similar concentrations of PFB block the expression of adhesion molecules and inhibit the expression of NF-κB thus suggesting a common pathway as the mechanism

Prior studies by our group showed that PFB inhibits the expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin on human umbilical vein endothelial cells which were stimulated with either TNFα or IL-1β, as well as inhibits the expression of NF-κB (Weinberg and Koledova, unpublished data). Furthermore RNA-seq experiments by our group show that PFB augments the expression of Nrf2 in astrocytes extracted from a human astrocytoma (Park, unpublished data). The reciprocal effects of PFB on NF-κB and Nrf2 make sense considering the homeostatic balance between the NF-κB pathway which usually activates pro-inflammatory genes and the Nrf2 pathway which usually activates anti-inflammatory genes20,56,62.

Some literature suggests that the pathways resulting in increased expression of ICAM-1 and E-selectin may be less responsive to antioxidants146–148. Other studies suggest that reactive oxygen intermediates activate NF-κB by a tyrosine kinase-dependent mechanism149,151. One possible mechanistic explanation for our results is that PFB may act to inhibit a specific protein tyrosine kinase that is upstream of IkBα kinase. This hypothesis will be the subject of future studies.

Studies also show that adhesion molecules such as ICAM are associated with the increased expression of RANTES comprising a direct correlation between the levels of RANTES levels and the levels of these adhesion molecules150. Consistent with these studies, our data show that PFB reduces both the secretion of RANTES and the expression of cell adhesion molecules in activated human astrocytes.

The cellular network of counterbalancing pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory pathways is depicted in Fig. 8. One mechanistic explanation of the actions of PFB on the dynamics of these pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory pathways is shown by the antagonistic responses of the NF-κB-mediated pro-inflammatory cascade to PFB, which are balanced against the Nrf2-mediated anti-inflammatory cascade mediated by PFB.

Figure 8.

Pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory pathways potentially affected by PFB. The pathways indicated by the red color represent the pro-inflammatory pathways mediated by NF-κB. The pathways indicated by the green color represent the anti-inflammatory pathways mediated by Nrf2.

Our future research plans are focused on determining mechanistically where PFB and its components affect specific interactions in this network of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory pathways seen in Fig. 8.

Conclusions

The data show that the cytokine/chemokine profiles of basal unstimulated astrocytes are different and distinct from the cytokine/chemokine profile of the IL-1β activated astrocytes. We called these 2 profiles the normal and the inflammatory cytokine/chemokine profiles. Furthermore, the cytokine/chemokine profiles fall into 3 temporal groups according to the timing from IL-1β exposure to maximal response: the early response, early prolonged response and the delayed response.

This study shows the multiple mechanisms by which PFB acts: (1) decreasing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines TNFα, RANTES and IP-10, which belong to the early prolonged response group and play a key role in chronic inflammation and the progression of neurodegenerative diseases; (2) reducing the oxidative stress in the inflammatory response by reducing the intracellular levels of ROS; (3) reducing the expression of inflammation-associated cell-surface adhesion molecules ICAM and VCAM which are important in recruiting the adaptive immune response; and (4) reducing the cytokine/chemokine profile differentially by the phenolic and non-phenolic fractions of PFB.

The observed anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects of PFB on astrocyte reactivity suggest therapeutic potential of PFB for neuroinflammatory conditions. PFB attenuates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines as well as reduces the expression of ROS and cellular adhesion molecules (CAM). Our study suggests that PFB causes a significant reduction in astrocyte activation with concomitant reduction of cytokine/chemokine production, ROS production and CAM expression. In summary, these PFB-induced changes suggest the potential that PFB may have in protecting against the neuro-inflammatory processes observed in the neurodegenerative conditions. PFB potentially may prevent astrocyte-mediated neuroinflammatory injury to the brain. These results show that PFB has important immunomodulatory effects on IL-1β-activated human astrocytes in vitro, which suggests that PFB may have a beneficial effect in the prevention and/or treatment of the neuroinflammatory state associated with such neurodegenerative diseases as Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and Huntington’s Disease, among others152–158.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) for their generous support and funding of this project. We also would like to thank Ms. Kelly Barret from Millipore Inc. who provided invaluable guidance and advice on the Multiplex Luminex Multi-analyte immunoassays. We would also like to thank Angela Botes and Christian Rückert for their valuable suggestions. Funding for this study was provided by the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB), 6, Persiaran Institusi, Bandar Baru Bangi, 43000 Kajang, Selangor, Malaysia.

Author Contributions

V.V.K. and R.P.W. conceived and designed the study, executed experiments, interpreted results, and wrote the manuscript. K.S. prepared reagents, analyzed the data, created tables and graphs, and drafted the manuscript. A.G. contributed to experiments and data analysis. A.G. also drew Figure 8. G.Z. contributed to experiments. A.A. contributed to manuscript figures. T.S. prepared reagents and identified compounds in PFB. R.S., A.S. and C.R. provided scientific direction and guidance. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. SF provided suggestions on experimental design.

Availability Of Data and Material

The datasets and supporting information of this article are included within the article and its additional supporting files.

Competing Interests

Several of the authors have an equity interest in Phenolaeis, a nutraceutical company incorporated in Malaysia, which has not yet gone into production nor do any of the authors receive any royalties or profits from this entity.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Robert P. Weinberg and Vera V. Koledova contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Robert P. Weinberg, Email: rweinber@mit.edu

ChoKyun Rha, Email: ckrha@mit.edu.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-34763-3.

References

- 1.Gordon MN, Schreier WA, Ou X, Holcomb LA, Morgan DG. Exaggerated astrocyte reactivity after nigrostriatal deafferentation in the aged rat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:106–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19971110)388:1<106::AID-CNE7>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rozovsky I, Finch CE, Morgan TE. Age-related activation of microglia and astrocytes: In vitro studies show persistent phenotypes of aging, increased proliferation, and resistance to down-regulation. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19:97–103. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(97)00169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apelt J, Leßig J, Schliebs R. β-Amyloid-associated expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in brain cortical tissue of transgenic Tg2576 mice. Neurosci Lett. 2002;329:111–5. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00589-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffin WS, Barger SW. Neuroinflammatory Cytokines-The Common Thread in Alzheimer’s Pathogenesis. US Neurol. 2010;6:19–27. doi: 10.17925/USN.2010.06.02.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JK, Tran T, Tansey MG. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009;4:419–29. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9176-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labadorf, A., Hoss, A. G. & Myers, R. H. Huntington’s Disease. In: Tsuneya, I., Gendelman, H. E., editors. Neuroimmune pharmacology. 2nd edition. Springer International, pp. 503–16 (2017).

- 7.Vargas DL, Nascimbene C, Krishnan C, Zimmerman AW, Pardo CA. Neuroglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with autism. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:67–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu J-Q, et al. Neuroinflammation and demyelination in multiple sclerosis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:716–22. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Y-T, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time — current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:327–39. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wimo A, et al. The worldwide costs of dementia 2015 and comparisons with 2010. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017;13:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.07.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer Disease in the US Population. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1119. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossi D. Astrocyte physiopathology: At the crossroads of intercellular networking, inflammation and cell death. Progress in Neurobiology. 2015;130:86–120. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbott NJ. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions and blood-brain barrier permeability. J Anat. 2002;200:629–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parpura, V. & Verkhratsky, A. Homeostatic function of astrocytes: Ca2+ and Na+ signalling. Transl Neurosci. 3 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Sofroniew MV. Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:638–437. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reichert William., editor. Indwelling Neural Implants. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verkhratsky A, Zorec R, Rodriguez JJ, Parpura V. Pathobiology of Neurodegeneration: The Role for Astroglia. Opera Medica Physiol. 2016;1(January):13–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ricci G, Volpi L, Pasquali L, Petrozzi L, Siciliano G. Astrocyte-neuron interactions in neurological disorders. J Biol Phys. 2009;35:317–36. doi: 10.1007/s10867-009-9157-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pekny M, et al. Astrocytes: a central element in neurological diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:323–45. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1513-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramesh G, MacLean AG, Philip MT. Cytokines and Chemokines at the Crossroads of Neuroinflammation, Neurdegeneration and Neuropathic Pain. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;13:1–20. doi: 10.1155/2013/480739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansson E, Rönnbäck L. Glial neuronal signaling in the central nervous system. FASEB J. 2003;17:341–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0429rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cordiglieri C, Farina C. Astrocytes exert and control immune responses in the brain. Curr Immunol Rev. 2010;6:150–159. doi: 10.2174/157339510791823655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farina C, et al. Astrocytes are active players in cerebral innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sofroniew MV. Astrocyte barriers to neurotoxic inflammation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:249–263. doi: 10.1038/nrn3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zamanian JL, et al. Genomic analysis of reactive astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2012;32:6391–6410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6221-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson MA, et al. Astrocyte scar formation aids central nervous system axon regeneration. Nature. 2016;532:195–200. doi: 10.1038/nature17623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crotti A, Ransohoff RM. Microglial physiology and pathophysiology: insights from genome-wide transcriptional profiling. Immunity. 2016;44:505–515. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liddelow SA, Barres BA. Reactive Astrocytes: production, function, and therapeutic potential. Immunity. 2017;46:957–967. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herz J, Filiano AJ, Smith A, Yogev N, Kipnis J. Myeloid cells in the central nervous system. Immunity. 2017;46:943–956. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein RS, Hunter CA. Protective and pathological immunity during CNS infections. Immunity. 2017;46:891–909. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liddelow SA, et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature. 2017;541:481–487. doi: 10.1038/nature21029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liedtke W, Edelmann W, Chiu FC, Kucherlapati R, Raine CS. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice lacking glial fibrillary acidic protein is characterized by a more severe clinical course and an infiltrative central nervous system lesion. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:251–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lepore AC, et al. Selective ablation of proliferating astrocytes does not affect disease outcome in either acute or chronic models of motor neuron degeneration. Exp Neurol. 2008;211:423–432. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraft AW, et al. Attenuating astrocyte activation accelerates plaque pathogenesis in APP/PS1 mice. FASEB J. 2013;27:187–198. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-208660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ben Haim L, Carrillo-de Sauvage MA, Ceyzeriat K, Escartin C. Elusive roles for reactive astrocytes in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:278. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heppner FL, Ransohoff RM, Becher B. Immune attack: the role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:358–372. doi: 10.1038/nrn3880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bush TG, et al. Leukocyte infiltration, neuronal degeneration, and neurite outgrowth after ablation of scar-forming, reactive astrocytes in adult transgenic mice. Neuron. 1999;23:297–308. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80781-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacDonald JM, et al. The Drosophila cell corpse engulfment receptor Draper mediates glial clearance of severed axons. Neuron. 2006;50:869–881. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lucin KM, Wyss-Coray T. Immune activation in brain aging and neurodegeneration: too much or too little? Neuron. 2009;64:110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chung W-SS, et al. Astrocytes mediate synapse elimination through MEGF10 and MERTK pathways. Nature. 2013;504:394–400. doi: 10.1038/nature12776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren Z, et al. ‘Hit and Run’ model of closed-skull traumatic brain injury (TBI) reveals complex patterns of post-traumatic AQP4 dysregulation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:834–845. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tasdemir-Yilmaz OE, Freeman MR. Astrocytes engage unique molecular programs to engulf pruned neuronal debris from distinct subsets of neurons. Genes Dev. 2014;28:20–33. doi: 10.1101/gad.229518.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eng LF, Vanderhaeghen JJ, Bignami A, Gerstl B. An acidic protein isolated from fibrous astrocytes. Brain Res. 1971;28:351–354. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90668-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bignami A, Eng LF, Dahl D, Uyeda CT. Localization of the glial fibrillary acidic protein in astrocytes by immunofluorescence. Brain Res. 1972;43:429–435. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90398-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacque CM, et al. Determination of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in human brain tumors. J Neurol Sci. 1978;35:147–155. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(78)90107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis SA, Balcarek JM, Krek V, Shelanski M, Cowan NJ. Sequence of a cDNA clone encoding mouse glial fibrillary acidic protein; structural conservation of intermediate filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:2743–2746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.9.2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boulay AC, et al. Translation in astrocyte distal processes sets molecular heterogeneity at the glio-vascular interface. Cell Discov. 2017;3:17005. doi: 10.1038/celldisc.2017.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.John Lin CC, et al. Identification of diverse astrocyte populations and their malignant malignant analogs. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:396–405. doi: 10.1038/nn.4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kamphuis W, Orre M, Kooijman L, Dahmen M, Hol EM. Differential cell proliferation in the cortex of the APPwePS1dE9 Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Glia. 2012;60:615–629. doi: 10.1002/glia.22295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sirko S, et al. Reactive glia in the injured brain acquire stem cell properties in response to sonic hedgehog. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:426–439. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechansisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boche D, Perry VH, Nicoli JA. Review: activation patterns of microglia and their identification in the human brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:3–18. doi: 10.1111/nan.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Colombo E, Farina C. Astrocytes: key regulators of neuroinflammation. Trends Immunol. 2016;37(9):608–620. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pekny M, Nilsson M. Astrocyte activation and reactive gliosis. Glia. 2005;50:427–434. doi: 10.1002/glia.20207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moynagh PN. The interleukin-1 signalling pathway in astrocytes: A key contributor to inflammation in the brain. J Anat. 2005;207:265–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee SC, Liu W, Dickson DW, Brosnan CF, Berman JW. Cytokine production by human fetal microglia and astrocytes. Differential induction by lipopolysaccharide and IL-1 beta. J Immunol. 1993;150:2659–2667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi SS, Lee HJ, Lim I, Satoh JI, Kim SU. Human astrocytes: Secretome profiles of cytokines and chemokines. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burkert K, Moodley K, Angel CE, Brooks A, Graham ES. Detailed analysis of inflammatory and neuromodulatory cytokine secretion from human NT2 astrocytes using multiplex bead array. Neurochem Int. 2012;60:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ridet JL, Malhotra SK, Privat A, Gage FH. Reactive astrocytes: Cellular and molecular cues to biological function. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:570–577. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(97)01139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee SJ, et al. ICAM-1-Induced Expression of Proinflammatory Cytokines in Astrocytes: Involvement of Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase and p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathways. J Immunol. 2000;165:4658–4666. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.8.4658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shrikant P, Chung IY, Ballestas ME, Benveniste EN. Regulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 gene expression by tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, and interferon-γ in astrocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 1994;51:209–220. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hsieh, H. L. & Yang, C. M. Role of redox signaling in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. BioMed Research International (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Uttara B, Singh AV, Zamboni P, Mahajan RT. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: a review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2009;7:65–74. doi: 10.2174/157015909787602823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Moukette, B. M. et al. In vitro antioxidant properties, free radicals scavenging activities of extracts and polyphenol composition of a non-timber forest product used as spice: Monodora myristica. Biol Res. 48 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Hou RCW, Chen HL, Tzen JTC, Jeng KCG. Effect of sesame antioxidants on LPS-induced NO production by BV2 microglial cells. Neuroreport. 2003;14:1815–1819. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200310060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lau FC, Joseph JA, McDonald JE, Kalt W. Attenuation of iNOS and COX2 by blueberry polyphenols is mediated through the suppression of NF-κB activation. J Funct Foods. 2009;1:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2009.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rasheed Z, et al. Polyphenol-rich pomegranate fruit extract (POMx) suppresses PMACI-induced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines by inhibiting the activation of MAP kinases and NF-κB in human KU812 cells. J Inflamm. 2009;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rossi L, Mazzitelli S, Arciello M, Capo CR, Rotilio G. Benefits from dietary polyphenols for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:2390–400. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scapagnini G, et al. Modulation of Nrf2/ARE pathway by food polyphenols: A nutritional neuroprotective strategy for cognitive and neurodegenerative disorders. Mol Neurobiol. 2011;44:192–201. doi: 10.1007/s12035-011-8181-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Leow S-S, Sekaran SD, Tan Y, Sundram K, Sambanthamurthi R. Oil palm phenolics confer neuroprotective effects involving cognitive and motor functions in mice. Nutr Neurosci. 2013;16:207–217. doi: 10.1179/1476830512Y.0000000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sambanthamurthi R, et al. Oil palm vegetation liquor: A new source of phenolic bioactives. Br J Nutr. 2011;106:1655–1663. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511002121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sambanthamurthi, R., Tan, Y. A. & Sundram, K. Treatment of vegetation liquors derived from oil-bearing fruit. United States Patent US 7,387,802 B2: Malaysian Palm Oil Board (2008).

- 73.Neo YP, Ariffin A, Tan CP, Tan YA. Phenolic acid analysis and antioxidant activity assessment of oil palm (E. guineensis) fruit extracts. Food Chem. 2010;122:353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.02.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sundram, K., Sambanthamurthi, R. & Tan, Y. A. Palm fruit chemistry and nutrition. In: Asia Pacific J Clin Nutr pp. 355–362 (2003). [PubMed]

- 75.Balasundram N, Ai TY, Sambanthamurthi R, Sundram K, Samman S. Antioxidant properties of palm fruit extracts. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2005;14:319–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sundaresan, A.M. Oil palm phenolics suppresses oxidative stress and inflammation. M.S. Thesis in Mechanical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2013).