Abstract

The Hippo signaling pathway is known to play an important role in multiple physiological processes, including adipogenesis. However, whether the downstream components of the Hippo pathway are involved in adipogenesis remains unknown. Here we demonstrate that the TEA domain family (TEAD) transcription factors are essential for adipogenesis in murine 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Knockdown of TEAD1–4 stimulated adipogenesis and increased the expression of adipocyte markers in these cells. Interestingly, we found that the TEAD4 knockdown–mediated adipogenesis proceeded in a Yes-associated protein (YAP)/TAZ (Wwtr1)–independent manner and that adipogenesis suppression in WT cells involved formation of a ternary complex comprising TEAD4 and the transcriptional cofactors C-terminal binding protein 2 (CtBP2) and vestigial-like family member 4 (VGLL4). VGLL4 acted as an adaptor protein that enhanced the interaction between TEAD4 and CtBP2, and this TEAD4–VGLL4–CtBP2 ternary complex dynamically existed at the early stage of adipogenesis. Finally, we verified that TEAD4 directly targets the promoters of major adipogenesis transcription factors such as peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and adiponectin, C1Q, and collagen domain–containing (Adipoq) during adipogenesis. These findings reveal critical insights into the role of the TEAD4–VGLL4–CtBP2 transcriptional repressor complex in suppression of adipogenesis in murine preadipocytes.

Keywords: adipogenesis, Hippo pathway, Yes-associated protein (YAP), triglyceride, lipid, adipogenesis, CtBP2, Hippo signaling, TEAD4, VGLL4

Introduction

Adipocytes are an important cell type possessing multiple functions in the systemic regulation of metabolism. Not only is adipose tissue critical for energy balance and nutrition homeostasis, dysfunction of adipogenesis also leads to multiple metabolic diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, and fatty liver (1, 2). Adipocyte differentiation consists of two phases. Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells first undergo lineage determination to become preadipocytes. Next, the preadipocytes differentiate into mature adipocytes, a process known as terminal differentiation (3). Numerous transcriptional factors that mediate cascades of signaling are involved in adipogenesis. Among them, peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ (PPARγ)3 and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α (C/EBPα) receive major attention (4). It has been shown that PPARγ modulates transcription of adipogenic genes by recruiting different co-regulators (5). For instance, C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, and C/EBPδ, as well as STAT5, EBF1, and several KLF family factors (6–9), promote PPARγ expression and function. Other transcriptional repressors of adipogenesis have been demonstrated to attenuate PPARγ expression and function, such as GATA2, CHOP, Zfp521, KLF3, Smad3 (10–14), and the C-terminal binding protein (CtBP) family (15–17). CtBP family members have a predominant function as transcriptional corepressors in association with sequence-specific DNA-binding transcriptional repressors in many physiological processes (18). The mammalian CtBP family proteins CtBP1 and CtBP2 are both ubiquitously expressed throughout development. CtBPs recruit various histone-modifying enzymes to silence target gene expression. These enzymes include histone methyl transferases (G9a/GLP) and histone deacetylates (HDAC1/2), and both contribute to altering histone posttranslational modification and form a repressive chromatin pattern in the promoter regions of target genes (18). CtBPs are recruited to several transcription factors in the regulation of adipogenesis. For example, RIP140 interacts with CtBPs and colocalizes with an enhancer of UCP1 to mediate gene repression (19). Moreover, PRDM16 regulates the development of brown adipocytes by cooperating with CtBPs (20). On the other hand, the transcription factor Krüppel-like factor 3 (KLF3) functions as an adipogenic repressor by recruiting CtBP2 to inhibit PPARγ activity (14, 21).

Adipogenesis signaling has been reported to cross-talk with multiple signaling pathways, such as the Wnt, transforming growth factor β, Notch, and Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathways (22–25). Despite this, the relationship between the Hippo signaling pathway, a pivotal signaling pathway that controls cell growth and cell fate decision, and adipogenesis remains elusive. To date, only a few studies have reported the function of Hippo signaling components in adipogenesis. Among these components, TAZ modulates mesenchymal stem cell differentiation by repressing PPARγ activity and activating Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) activity (26). YAP, as an effector of the transcription factor SOX2, regulates PPARγ to determine cell fate in the osteo-adipo lineage (27). Also, YAP activity is crucial for cAMP or protein kinase A (PKA)–induced adipogenesis (28). MST2 and SAV1 promote adipogenesis by activating PPARγ activity (29). Moreover, knockdown of TEAD4 leads to the failure of adipogenesis from bone marrow–derived stem cells (30).

The Hippo signaling pathway, consisting of an upstream kinase cascade (MST1/2–SAV1–LATS1/2–MOB1) and a downstream nuclear transcriptional regulator complex (TEAD–YAP–VGLL4), is considered as a key regulator of organ growth and tissue development in Drosophila and mammals (31, 32). The TEA domain family (TEAD) proteins are considered primary transcription factors of the Hippo pathway, whereas YAP and TAZ (also called WWTR1, YAP's paralog) are mostly regarded as general transcription coactivators of TEADs. When the Hippo pathway is inactivated, YAP and TAZ shuttle from the cytoplasm to the nucleus to interact with TEADs and induce the expression of Hippo target genes, including CTGF, CYR61, and Myc (33–36). TEADs are crucial for tissue development as well as cancer progression. In mammals, there are four highly conserved TEAD transcription factors, TEAD1–4. Among these four TEADs factors, TEAD4 is particularly critical for the first mammalian cell linage commitment in blastomeres (37). TEAD4 also modulates skeletal muscle development and regulates Myogenin expression as well as unfolded protein genes in C2C12 cell differentiation (38, 39). Besides YAP and TAZ, vestigial-like (VGLL) proteins are a group of identified TEAD-interacting partners (40–43). There are four VGLL proteins in vertebrates, and they contain a highly conserved TDU domain, which mediates the interaction with TEAD proteins (44). VGLL4 has been reported as a tumor suppressor by competing with YAP for TEAD4 binding in gastric cancer (40, 45). A significant correlation between VGLL4 depletion and poor patient survival of pancreatic cancer also demonstrates a tumor repressor role for VGLL4 (46). By competing with YAP for TEAD binding, VGLL4 abolishes TEAD transcriptional activity and executes growth inhibition through its two TDU domains (43). Thus, the two TEAD cofactors YAP and VGLL4 antagonize each other for TEAD binding in the regulation of development. However, whether the TEAD–YAP–VGLL4 transcriptional regulator complex plays a role during adipogenesis remains unclear.

Here we provide compelling evidence for an inhibitory function of TEAD4 during adipogenesis. Knockdown of TEAD4 expression significantly promotes adipogenesis, dependent on the presence of both CtBP2 and VGLL4 but independent of YAP function. CtBP2 is identified as a novel TEAD4 binding partner, and VGLL4 enhances their interaction as an adaptor protein. Notably, ChIP-qPCR verified that TEAD4 directly binds to the PPARγ promoter at the early stage of adipogenesis. Collectively, our study uncovers the function of TEAD4 in adipocyte differentiation and provides insights into how the TEAD4–VGLL4–CtBP2 transcriptional complex dynamically controls adipogenesis.

Results

TEADs repress 3T3-L1 cell differentiation, and TEAD knockdown promotes adipogenesis in vitro

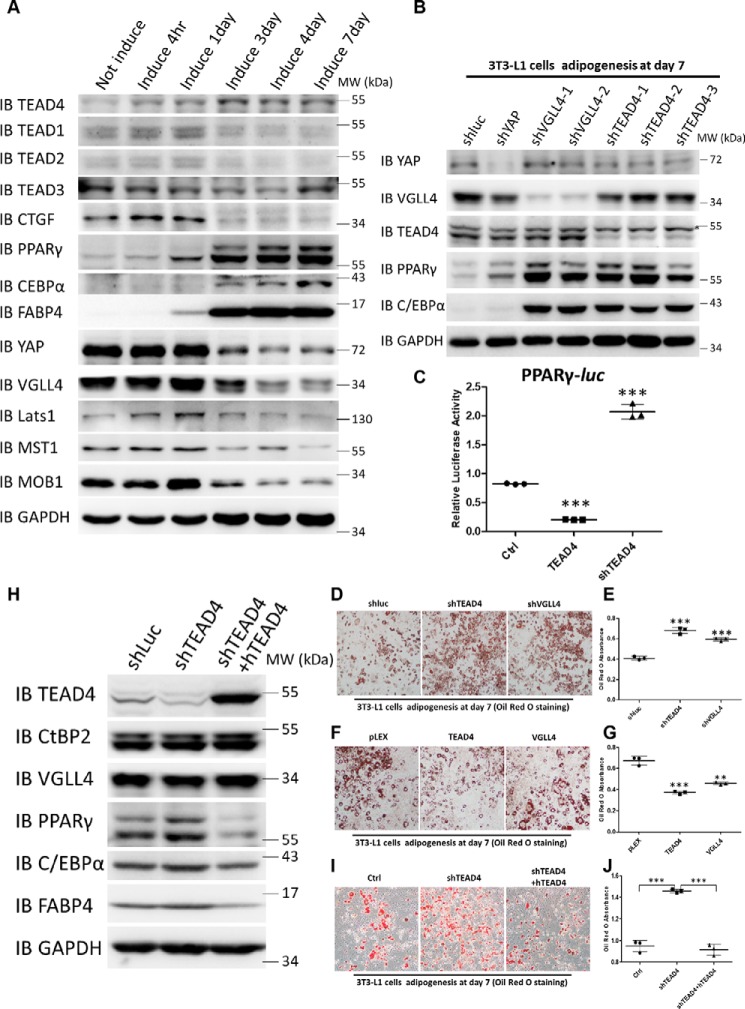

To investigate whether the Hippo signaling transcription factor TEADs (1–4) and their cofactors YAP/VGLL4 play a role during adipogenesis, we first examined the protein expression pattern of these factors during 3T3-L1 cell adipogenesis. When 3T3-L1 cells were induced to differentiate with the hormonal mixture IDMT (insulin, dexamethasone, IBMX, and troglitazone) (see “Materials and methods”), the expression levels of the adipogenic markers PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FABP4 dramatically increased as adipogenesis progressed (Fig. 1A). Hippo core components, including MST1, MOB1, Lats1, YAP, VGLL4, and TEAD1–4, were all expressed during adipogenesis. However, only the TEAD4 protein level was increased in this process, and the increase in TEAD4 protein level preceded the elevation of PPARγ expression (Fig. 1A). To further determine whether all TEAD family members are essential for preadipocytes differentiation, TEAD1–4 expression was down-regulated in 3T3-L1 cells using shRNA lentiviral particles targeting each of them. Oil Red O staining and qRT-PCR analyses showed that adipogenesis was markedly enhanced, accompanied by increased adipogenic marker expression (Fig. S1, A–C). These results suggest that all TEADs are involved in adipogenesis. As TEAD4 exhibited altered protein levels during adipogenesis, we focused on TEAD4 for subsequent study.

Figure 1.

TEADs repress 3T3-L1 cell differentiation, and TEAD knockdown promotes adipogenesis in vitro. A, immunoblot (IB) analysis of TEAD1–4, CTGF, PPARγ, C/EBPα, FABP4, YAP, VGLL4, CtBP2, Lats1, MST1, and MOB1 expression during the process of adipogenesis. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The positions of protein molecular mass markers are indicated on the right. MW, molecular weight. B, immunoblot analysis of YAP, VGLL4, TEAD4, PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FABP4 expression in lentivirus-mediated expression of shLuc, shYAP, shVGLL4 1–2, and shTEAD4 1–3 3T3-L1 stable cell lines after adipogenic mixture induction for 7 days. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The positions of protein molecular mass markers are indicated on the right. The asterisk denotes a nonspecific band. C, effect of overexpression or knockdown of TEAD4 on PPARγ-Luc activity in 293T cells. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001 by Student's t test. D and E, Oil Red O staining of lentivirus-mediated expression of shLuc, shTEAD4, and shVGLL4 3T3-L1 stable cell lines after adipogenic mixture induction for 7 days (D) and quantification by measurement of the absorbance at 510 nm (E). Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001 by Student's t test. F and G, Oil Red O staining of lentivirus-mediated overexpression of pLEX, TEAD4, and VGLL4 3T3-L1 stable cell lines after adipogenic mixture induction for 7 days (F) and quantification by measurement of the absorbance at 510 nm (G). Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001 by Student's t test; **, p < 0.01 by Student's t test. H, immunoblot analysis of TEAD4, PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FABP4 expression in lentivirus-mediated expression of shLuc, shTEAD4, and shTEAD4+hTEAD4 3T3-L1 stable cell lines after adipogenic mixture induction for 7 days. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The positions of protein molecular mass markers are indicated on the right. I and J, Oil Red O staining of lentivirus-mediated expression of shLuc, shTEAD4, and shTEAD4+hTEAD4 3T3-L1 stable cell lines after adipogenic mixture induction for 7 days (I) and quantification by measurement of the absorbance at 510 nm (J). Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001 by Student's t test.

Because YAP and VGLL4 are known cofactors of TEADs, their functions during adipogenic differentiation were examined. The results shown in Fig. 1B indicated that TEAD4, YAP, or VGLL4 knockdown markedly increased PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FABP4 expression. Consistent with previous studies, YAP is crucial for cell fate in the osteo-adipo lineage (27). Next, whether TEAD4 directly regulates PPARγ transcriptional activity was investigated. In 293T cells, TEAD4 overexpression inhibited the luciferase (Luc) reporter gene PPARγ-Luc (47), whereas knockdown of TEAD4 by its shRNA up-regulated this reporter activity (Fig. 1C). In addition, another two adipogenic reporters, C/EBPα-Luc and CIDEA-Luc, showed a similar regulatory mode by TEAD4 (Fig. S1, D and E). Analysis of the PPARγ-Luc reporter sequence revealed 11 potential TEAD DNA binding sites located within its transcription regulatory region, indicating that PPARγ may be a direct target of TEAD4.

Next we investigated whether TEAD4 and VGLL4 are dispensable for adipogenesis in cell culture. Compared with control 3T3-L1 cells expressing shLuc, 3T3-L1 cells with lentivirus-mediated knockdown of TEAD4 or VGLL4 exhibited a dramatically enhanced adipogenesis phenotype (Fig. 1D), as measured by an increase in adipocyte staining with Oil Red O (Fig. 1E). Conversely, stable ectopic expression of TEAD4 or VGLL4 in 3T3-L1 cells inhibited adipogenesis and exhibited less fat droplet formation (Fig. 1, F and G). To fully confirm the function of TEAD4 in adipogenesis, we transfected human TEAD4 in TEAD4 knockdown 3T3-L1 cells (Fig. 1H). Re-expression of hTEAD4 rescued TEAD4 deficiency and blocked adipogenesis (Fig. 1, I and J) and expression of the adipocytes markers PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FABP4 (Fig. 1H). Thus, TEAD4 and VGLL4 play repressive roles in adipogenesis.

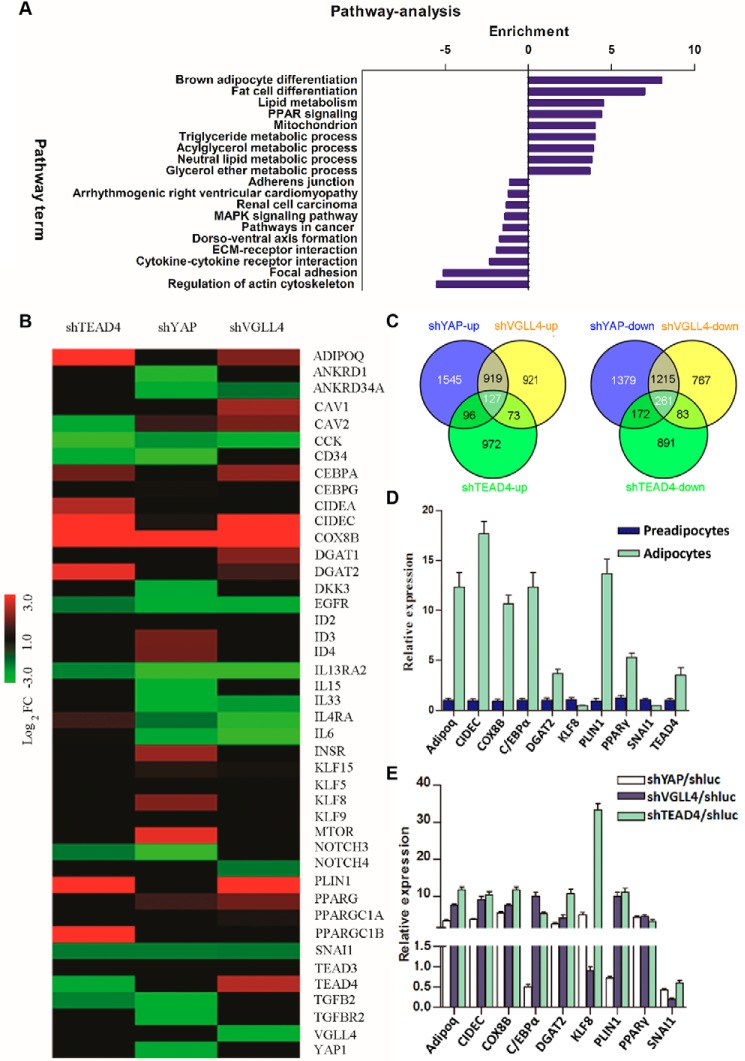

TEAD4 modulates adipogenesis-related pathways

To better characterize the transcription signature defining the adipogenic potential of TEAD4, YAP, and VGLL4, we performed a microarray analysis using stable cell lines with knockdown expression of these genes in the late adipogenesis state (day 7). The knockdown efficiencies of microarray samples were verified by Western blot analysis (Fig. S2A). The microarray data showed an alternation of expression profiles for a number of biologically relevant genes involved in regulating adipogenesis upon down-regulating TEAD4 expression (Fig. 2B). Expression of a fraction of genes was commonly altered upon knockdown of TEAD4, YAP, and VGLL4 (Fig. 2C). Several genes known to be activated in adipogenesis were highly enriched, including PPARγ, C/EBPα, ADIPOQ, CIDEC, COX8B, DGAT2, and PLIN1 (Fig. 2B). In contrast, adipogenesis repressor genes were down-regulated, including CAV2, cholecystokinin (CCK), CD34, EGFR, IL13RA2, NOTCH3 (48), and SNAI1 (49) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

TEAD4, YAP, and VGLL4 modulate adipogenesis-related pathways. A, KEGG pathway analysis. Common genes that were regulated more than 2-fold by knockdown of TEAD4/YAP/VGLL4 3T3-L1 cells after adipogenic mixture induction for 7 days were submitted to DAVID KEGG pathway analysis. The x axis indicates pathway enrichment by value of −log10 (p value). Both up-regulated and down-regulated signaling pathways are shown. B, microarray heatmaps of the above samples showing the differential expression profiles of adipogenesis-related genes. Red indicates up-regulated genes, and green indicates down-regulated genes. Colors are set by the value of log2 (-fold change). C, Venn analysis of the microarray-identified genes that were altered more than 2-fold. The numbers of common altered genes are shown. D and E, qRT-PCR validation of the altered genes identified by microarray. Shown are gene expression profiles between preadipocytes and adipocytes and normalized to β-actin expression (D) and gene alternation in shYAP, shVGLL4, or shTEAD4 3T3-L1 cells after adipogenic mixture induction for 7 days. E, these genes' -fold change was normalized to shluc 3T3-L1 control samples. Each value represents the average of three independent repeats.

KEGG pathway analysis (50) revealed that adipogenesis-related pathways were highly enriched upon TEAD4 knockdown, including the brown fat differentiation pathway, lipid metabolism pathway, PPAR signaling pathway, triglyceride metabolism process, acylglycerol metabolism process, neutral lipid metabolism process, and glycerol ether metabolism process (Fig. 2A). Other pathways repressing adipogenesis were inhibited, such as regulation of the actin cytoskeleton pathway, focal adhesion, and the cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction pathway (Fig. 2A). qRT-PCR analysis further validated that TEAD4 knockdown dramatically increased adipogenic gene expression, including PPARγ, C/EBPα, KLF8, CIDEC, etc. (Fig. 2E). Although VGLL4 and YAP knockdown microarray heatmaps both showed some adipogenic gene enrichment, VGLL4's depletion heatmaps, compared with YAP's, were more similar to TEAD4's (Fig. 2B). Both VGLL4 and YAP are TEAD4 cofactors, and YAP function is regulated by SOX2 during adipogenesis (27). Based on the microarray heatmap patterns of knockdown of TEAD4, VGLL4, or YAP, it is possible that TEAD4/VGLL4 regulates adipogenesis in a different way than YAP.

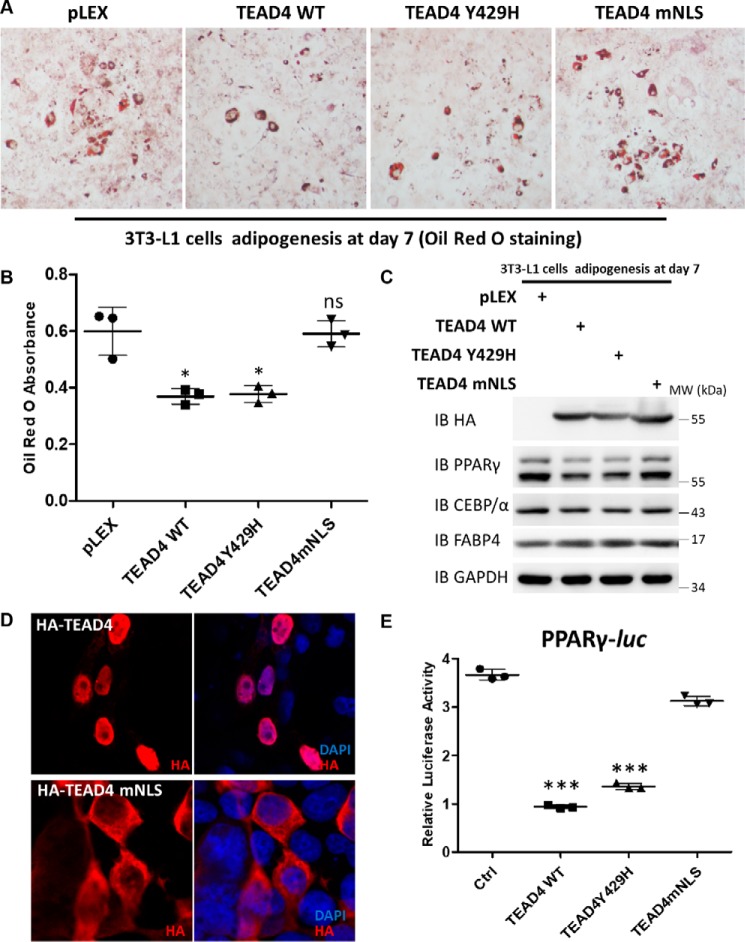

TEAD4-mediated regulation of adipogenesis is independent of YAP and TAZ

Previous studies have identified the YAP-binding surface of TEADs, and a hTEAD2 single-site mutant at Tyr-442 abolishes YAP binding (51). To clarify whether YAP is necessary for TEAD4 function during adipogenesis, we performed sequence alignment of the TEAD YAP-binding-domain and predicted that the hTEAD4 Tyr-429 site is essential for its binding to YAP (Fig. S4B). Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay confirmed that TEAD4Y429H did not bind to YAP but interacted with VGLL4 (Fig. S4C). TAZ is YAP's mammalian homolog, with consensus positions between YAP and TAZ of more than 50% in protein structure. In the same way, TEAD4Y429H notably abolished binding with TAZ (Fig. S4D). Next, the function of TEAD4Y429H in adipogenesis was analyzed. In parallel, a TEAD4-NLS mutant (TEAD4mNLS) was created, and we analyzed whether TEAD4 function in adipogenesis depends on its nucleus localization. Immunofluorescence staining assays showed that the majority of the exogenously expressed TEAD4mNLS localized in the cytosol, whereas WT TEAD4 exhibited nuclear localization in 293T cells (Fig. 3D). Induction with adipogenic mixtures and Oil Red O staining assays showed that TEAD4Y429H, like TEAD4, inhibited 3T3-L1 differentiation, whereas TEAD4mNLS mostly lost its function on adipogenesis, suggesting that TEAD4 has to be localized in the nucleus to regulate adipogenesis (Fig. 3A). These findings were supported by direct measurement of intracellular triglyceride content and immunoblot analysis of the adipogenic markers PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FABP4 (Fig. 3, B and C). Moreover, the PPARγ-Luc reporter assay demonstrated that TEAD4Y429H markedly inhibited PPARγ activity as well as WT TEAD4, whereas TEAD4mNLS did not have a similar effect (Fig. 3E). Collectively, these data suggest that TEAD4 regulates adipogenesis independently of YAP and TAZ.

Figure 3.

TEAD4-mediated regulation of adipogenesis is independent of YAP. A and B, Oil Red O staining of lentivirus-mediated overexpression of pLEX/TEAD4 WT/TEAD4 Y429H/TEAD4 mNLS 3T3-L1 stable cell lines after adipogenic mixture induction for 7 days (A) and quantification by measurement of the absorbance at 510 nm (B). ns, not significant. *, p < 0.05 by Student's t test. C, immunoblot (IB) analysis of HA, PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FABP4 expression in the above cell samples. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The positions of protein molecular mass marker are indicated on the right. MW, molecular weight. D, immunofluorescence staining of transfected HA-TEAD4 and HA-TEAD4 mNLS with the indicated antibodies in 293T cells. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). E, effect of ectopic expression of TEAD4 WT, TEAD4 Y429H, and TEAD4 mNLS on PPARγ-Luc activity in 293T cells. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001 by Student's t test. Ctrl, control.

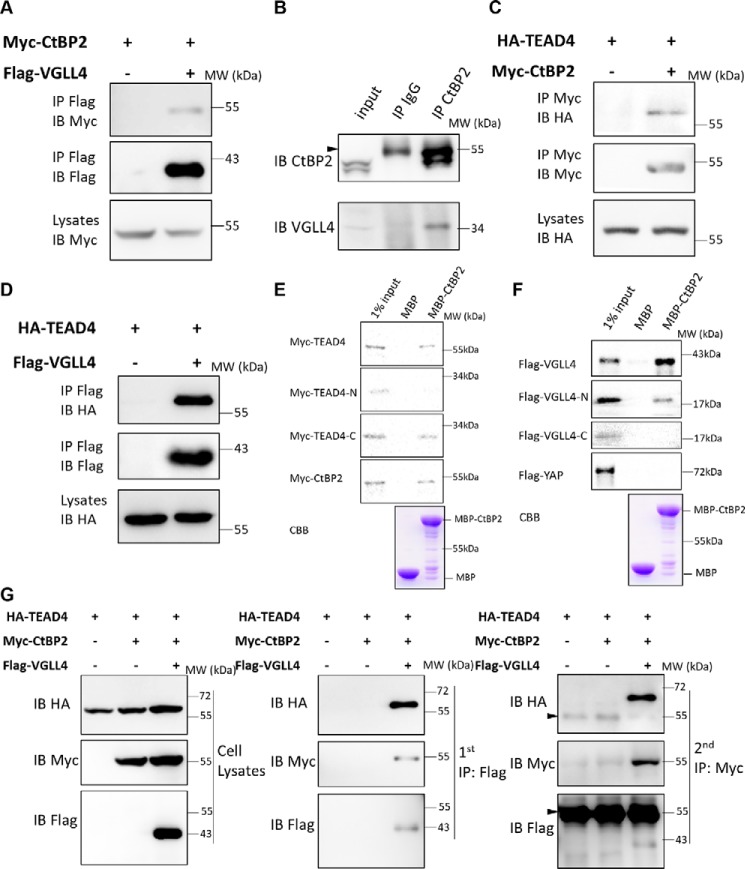

CtBP2 is identified as a novel TEAD4 cofactor

The data above showed that TEAD4 plays an inhibitory role during adipogenesis, independent of YAP, but the detailed repressive mechanism remains unclear. We hypothesized that there might be a potential TEAD4 corepressor with inhibitory function during adipogenesis.

We reported previously that VGLL4 is a cofactor of TEADs and directly competes with YAP for TEAD binding (40, 41). To investigate this further, affinity purification of N-terminal FLAG-tagged VGLL4 in 293T cells was conducted, and eluates were analyzed with MS to identify potential partners of VGLL4. CtBP2, a well-known adipogenic co-repressor, was identified to interact with VGLL4 (Table S1). To verify the MS results, a co-IP assay was first performed to confirm the interaction between exogenously expressed VGLL4 and CtBP2 in 293T cells. As expected, strong binding between CtBP2 and VGLL4 was detected (Fig. 4A). We also confirmed that CtBP2 interacted with VGLL4 endogenously using a CtBP2 antibody for the co-IP assay (Fig. 4B). Based on these findings, we speculated that TEAD4, CtBP2, and VGLL4 form a complex to regulate adipogenesis. Interestingly, we have previously performed a yeast two-hybrid screen to search for novel Scalloped (Sd, the Drosophila homolog of TEAD) binding proteins (41). Using an Sd C-terminal protein fragment as a bait, the Drosophila cDNA library was screened, and two independent clones representing C-terminal fragments of Drosophila dCtBP were identified. The co-IP assay again confirmed the interaction between CtBP2 and TEAD4 (Fig. 4C). Subsequent GST pulldown assay confirmed a direct interaction between TEAD4 and CtBP2, using YAP as a positive control (Fig. S3B). To further map these protein interactions, purified MBP-tagged CtBP2 protein was incubated with 35S-labeled TEAD4 or VGLL4 obtained by in vitro transcription and translation (IVTT). As shown in Fig. 4E, CtBP2 directly bound to full-length TEAD4 or C-terminal TEAD4 (from 218 to 435 aa) but did not interact with N-terminal TEAD4. CtBP2 also directly bound to full-length VGLL4 or N-terminal VGLL4 (from 1 to 148 aa) but did not interact with C-terminal VGLL4 (Fig. 4F). On the other hand, no interaction was detected between CtBP2 and YAP (Fig. 4F and Fig. S3A).

Figure 4.

CtBP2 formed a complex with TEAD4-VGLL4. A, co-IP assay of the interaction between CtBP2 and VGLL4. The indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T cells and analyzed by co-IP. IB, immunoblot; MW, molecular weight. B, the endogenous interaction between CtBP2 and VGLL4. 293T cells lysates were incubated with CtBP2 or IgG antibodies, followed by immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. The arrowhead indicates the IgG heavy chain. C and D, co-IP assay of the interaction between TEAD4 and CtBP2 (C) and TEAD4 and VGLL4 (D). The indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T cells and analyzed by co-IP. E, an MBP pulldown assay showed that the TEAD4 and TEAD4 C termini were pulled down by MBP-CtBP2. MBP or MBP-CtBP2 bound to MBP beads were incubated with IVTT 35S-labeled TEAD4/TEAD4-N/TEAD4-C for 3 h. Immobilized complexes were then washed and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The input was 10% of the total amount of IVTT 35S-TEAD4/TEAD4-N/TEAD4-C. CBB, Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. F, an MBP pulldown assay showed that VGLL4 and VGLL4 N termini were pulled down by MBP-CtBP2. MBP or MBP-CtBP2 bound to MBP beads were incubated with IVTT 35S-labeled VGLL4/VGLL4-N/VGLL4-C for 3 h. Immobilized complexes were then washed and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The input was 10% of the total amount of IVTT 35S-VGLL4/VGLL4-N/VGLL4-C. G, 293T cells expressing the indicated proteins were collected for two-step immunoprecipitation and analyzed by Western blotting. Cell lysates were first co-immunoprecipitated with M2-FLAG beads and then eluted for a second immunoprecipitation with Myc antibody. The arrowheads indicate the IgG heavy chains.

To further map the interaction between CtBP2, TEAD4, and VGLL4, CtBP2 proteins with the N terminus (from 1 to 666 aa) or C terminus (from 667 to 1338 aa) only were created according to their secondary structure. Co-IP assays demonstrated that N-terminal CtBP2 interacted with both TEAD4 and VGLL4 (Fig. S3, C and D). The TEAD4–VGLL4 interaction was also verified, and the results were consistent with previous studies (Fig. 4D) (40, 41). Given that all three proteins, TEAD4, VGLL4, and CtBP2, interact with each other directly, we speculated that these three proteins form a ternary complex. To verify this hypothesis, a two-step immunoprecipitation assay was conducted. Our results showed that TEAD4, VGLL4, and CtBP2 associate with each other and form a ternary complex (Fig. 4G). Taken together, these results demonstrate that CtBP2 is a novel TEAD4–VGLL4 partner.

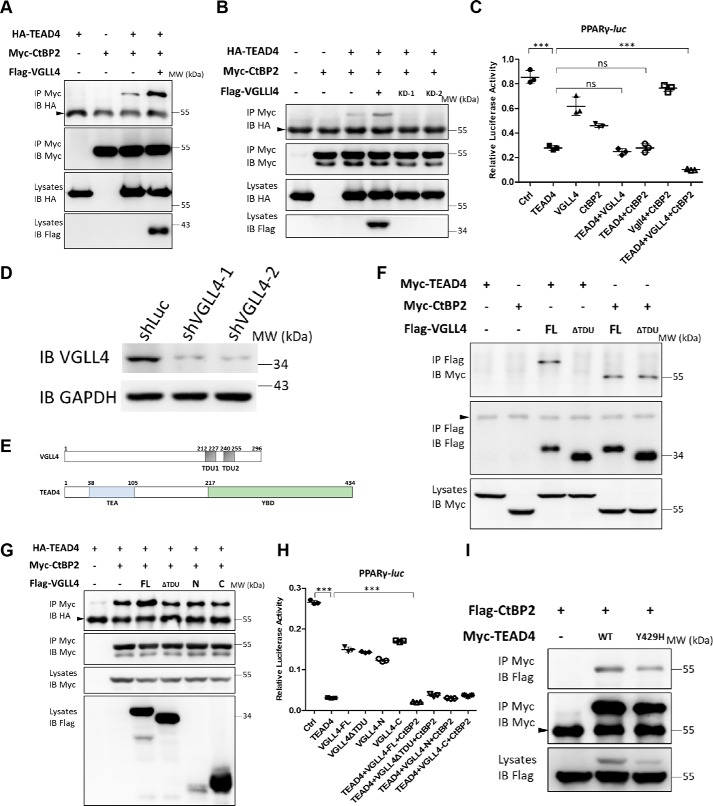

VGLL4 acts as an adaptor protein to enhance the TEAD4–CtBP2 interaction

As a co-repressor of several essential cellular processes, CtBPs sometimes require a beacon or linker for their recruitment to target genes or transcription factors (52). Based on these findings, we next investigated the idea of VGLL4 having such a role. The interaction between TEAD4 and CtBP2 in the presence or absence of exogenous VGLL4 was examined by co-IP assay. As shown in Fig. 5A, co-expression of exogenous VGLL4 strongly enhanced binding between TEAD4 and CtBP2. On the other hand, the interaction between TEAD4 and CtBP2 was significantly reduced when VGLL4 expression was silenced by shRNA (Fig. 5, B and D). Furthermore, VGLL4 also enhanced TEAD4-C and CtBP2 binding (Fig. S4A), raising the question whether this enhancement by VGLL4 is functionally essential. A luciferase assay showed that co-expression of TEAD4, VGLL4, and CtBP2 dramatically inhibited PPARγ reporter activity compared with TEAD4 expression alone (Fig. 5C). In contrast, neither expression of TEAD4–VGLL4 nor TEAD4–CtBP2 enhanced the reduction in PPARγ-Luc reporter activity compared with TEAD4 expression alone (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that both VGLL4 and CtBP2 are essential for repressing PPARγ promoter activity together with TEAD4. In other words, TEAD4–VGLL4–CtBP2 functions as a complex in regulating PPARγ transcription.

Figure 5.

VGLL4 acts as an adaptor protein to enhance TEAD4–CtBP2 interaction. A, co-IP assay of the interaction between TEAD4 and CtBP2 in the presence or absence of exogenous VGLL4. The indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T cells and analyzed by co-IP. The arrowhead indicates the IgG heavy chain. IB, immunoblot; MW, molecular weight. B, co-IP assay of the interaction between TEAD4 and CtBP2 in the presence or absence of endogenous VGLL4. The indicated plasmids and VGLL4 shRNAs were transfected into 293T cells and analyzed by co-IP. The arrowhead indicates the IgG heavy chain. C, effect of co-expression of TEAD4, VGLL4, and CtBP2 on PPARγ-Luc activity in 293T cells. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001 by Student's t test; ns, no significance. D, immunoblot analysis of shVGLL4–1 and shVGLL4–2 knockdown efficiencies in 293T cells. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The positions of protein molecular mass marker are indicated on the right. E, schematic of the domain organization of human VGLL4 and TEAD4. F, co-IP assay to detect VGLL4 TDU domain function in its interaction with TEAD4 or CtBP2, respectively. The indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T cells and analyzed by co-IP. The arrowhead indicates the IgG heavy chain. FL, full-length. G, co-IP assay to detect the effect of different exogenous VGLL4 truncation forms on the interaction between TEAD4 and CtBP2. The indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T cells and analyzed by co-IP. The arrowhead indicates the IgG heavy chain. H, only VGLL4 full-length could cooperate with TEAD4 and CtBP2 to further inhibit PPARγ-Luc reporter activity. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001 by Student's t test. I, co-IP assay to detect TEAD4Y429 site function in its interaction with CtBP2. The indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T cells and analyzed by co-IP. The arrowhead indicates the IgG heavy chain, and the asterisk denotes the nonspecific band.

To further clarify how VGLL4 interacts with TEAD4 and CtBP2, several VGLL4 truncation proteins were made based on its secondary structure and known protein interaction domains (Fig. 5E) (40, 44). Consistent with previous studies, the TDU domains of VGLL4 mediate its interaction with TEAD4, and VGLL4 lacking TDUs (VGLL4▵TDU) did not bind to TEAD4 but remained interaction with CtBP2 (Fig. 5F). Next, we checked whether VGLL4▵TDU, VGLL4-N, or VGLL4-C enhances binding between TEAD4 and CtBP2, as all of these three VGLL4 variants bind to either TEAD4 or CtBP2 but not to both of them (Figs. 4F and 5F). Our co-IP results showed that only full-length VGLL4 enhanced TEAD4 and CtBP2 binding, whereas other VGLL4 variants (VGLL4▵TDU, VGLL4-N, or VGLL4-C) are not functional in interacting with both TEAD4 and CtBP2 (Fig. 5G). A PPARγ-Luc reporter assay also demonstrated that only full-length VGLL4 cooperated with TEAD4 and CtBP2 to inhibit PPARγ promoter transcription activity (Fig. 5H). These results suggest a specific model for VGLL4-mediated enhancement of TEAD4 and CtBP2 binding via both its TDU domains and N terminus. Thus, VGLL4 may act as a linker, recruiting CtBP2 to TEAD4, and regulate the expression of target genes. In addition, TEAD4Y429H abolished binding to YAP (Fig. S4C) but still bound to CtBP2 (Fig. 5I), indicating a role for TEAD4Y429H in adipogenesis (Fig. 3, A–C). Collectively, our findings suggest that CtBP2 acts as a TEAD4 corepressor in regulating PPARγ promoter activity and that VGLL4 plays a key role in forming the ternary complex.

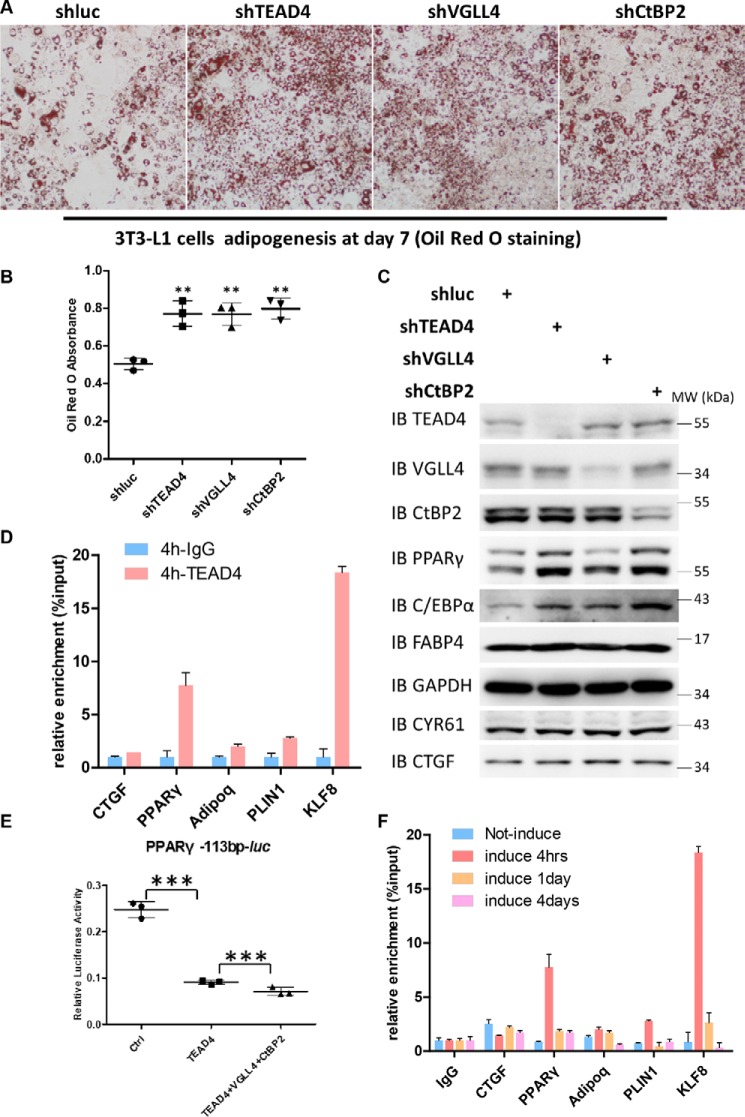

TEAD4 targets PPARγ and Adipoq promoters to regulate adipogenesis at an early stage

We identified CtBP2 as a new TEAD4 binding partner. Next we examined whether CtBP2 plays a functional role in TEAD4-mediated adipogenesis. Down-regulation of CtBP2 expression by lentiviral shRNA enhanced adipogenesis (Fig. 6, A and C), as shown by a quantitative increase in adipocyte staining with Oil Red O (Fig. 6B). At the same time, expression of the adipocyte markers PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FABP4 was elevated (Fig. 6C). On the other hand, stable overexpression of CtBP2, TEAD4, or VGLL4 in 3T3-L1 cells impaired adipogenesis (Fig. S5, A–C). These results further suggest that TEAD4, VGLL4, and CtBP2 form a ternary complex and synergistically cooperate with each other in the regulation of adipogenesis.

Figure 6.

TEAD4 targets PPARγ and Adipoq promoters to regulate adipogenesis at an early stage. A and B, Oil Red O staining of lentivirus-mediated expression of shLuc, shTEAD4, shVGLL4, and shCtBP2 3T3-L1 stable cell lines after adipogenic mixture induction for 7 days (A) and quantification by measurement of the absorbance at 510 nm (B). **, p < 0.01 by Student's t test. C, immunoblot analysis of TEAD4, VGLL4, CtBP2, PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FABP4 expression in the above cell samples. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The positions of protein molecular mass markers are indicated on the right. IB, immunoblot; MW, molecular weight. D, anti-IgG or anti-TEAD4 ChIP-qPCR in stably expressing HA-TEAD4 3T3-L1 cells after adipogenic mixture induction for 4 h. The co-eluted DNA fragments were amplified using primer sets at the promoters of PPARγ, Adipoq, PLIN1, and KLF8 and were normalized to the inputs. E, effect of ectopic expression of TEAD4, VGLL4, and CtBP2 on PPARγ-113bp-Luc reporter activity in 293T cells. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001 by Student's t test. F, anti-TEAD4 ChIP-qPCR in stably expressing HA-TEAD4 3T3-L1 cells at different adipogenic stages.

We then asked how the TEAD4–VGLL4–CtBP2 complex regulates adipogenesis. ChIP assays were conducted using 3T3-L1 cells stably expressing HA-TEAD4 to determine whether PPARγ is a direct target of TEAD4. Based on the quantitative PCR results, the expression of KLF8, C/EBPα, CIDEC, Adipoq, and PLIN1 was dramatically up-regulated in TEAD4 knockdown adipogenic 3T3-L1 cells (Fig. 2E). Next, multiple primers were designed for ChIP-qPCR to test whether TEAD4 binds to the promoter regions of these genes. The antibody used efficiently immunoprecipitated TEAD4 in 3T3-L1 stable cell lines, as shown in Fig. S5D. When adipogenesis was induced by adipogenic mixtures for 4 h, a strong enrichment of the PPARγ promoter was observed in ChIP-TEAD4 samples relative to the input control, as well as for Adipoq, PLIN1, and KLF8 promoters (Fig. 6D). Sequencing analysis of the PPARγ, Adipoq, PLIN1, and KLF8 promoter regions revealed several putative TEAD4 binding sites. Consistent with our findings, ChIP sequencing data (GSE52437) from database shared by a previous TEAD4 study demonstrated positive binding peaks in the PPARγ, Adipoq, PLIN1, and KLF8 promoters (53) (Fig. S5E). To fully demonstrate that PPARγ is a TEAD4 direct target, we cloned this region of the PPARγ promoter (113 bp) and made a PPARγ-113bp-Luc reporter construct. By luciferase assay, we found that TEAD4 overexpression evidently trans-inactivated this reporter, and TEAD4-VGLL4-CtBP2 co-expression showed enhanced inhibition (Fig. 6E). Moreover, the results from a time course analysis suggested that the binding between the TEAD4 and PPARγ, Adipoq, PLIN1, or KLF8 promoters was dynamic, and the strongest binding phase was at the very early stage of adipogenesis (4 h) (Fig. 6F). As adipogenesis progressed, the binding of TEAD4 to its target genes became weaker, suggesting a weaker modulation on adipogenesis. Together, these findings suggest that TEAD4 directly binds to the PPARγ promoter at the beginning of the adipogenesis process, followed by the recruitment of CtBP2-VGLL4, which enhances TEAD4-mediated modulation on its target genes.

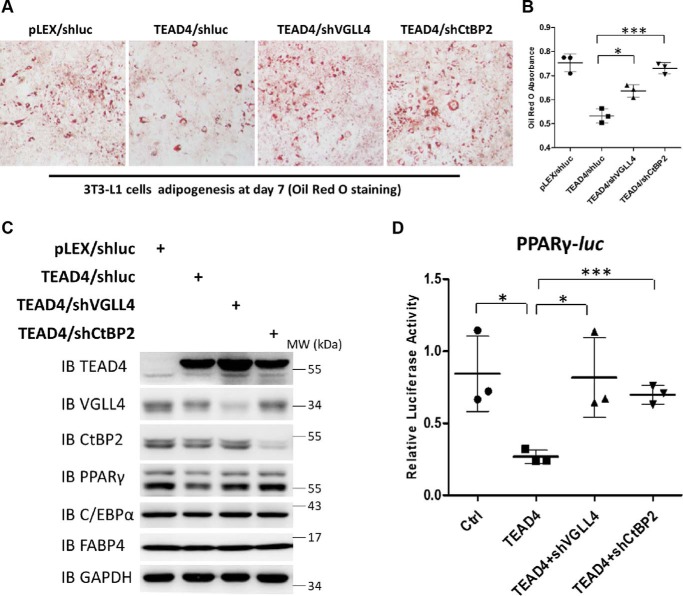

VGLL4 and CtBP2 are indispensable for adipogenesis inhibition mediated by TEAD4 overexpression

To further determine whether VGLL4 and CtBP2 mediate TEAD4 function in 3T3-L1 cell differentiation, adipogenesis in TEAD4-overexpressing cells was examined upon VGLL4 or CtBP2 depletion. To this end, we used lentivirus-mediated shRNA to knock down the expression of VGLL4 or CtBP2 in TEAD4-overexpressing cells (Fig. 7C). Inhibition of 3T3-L1 cell differentiation caused by TEAD4 ectopic expression was strikingly blocked in cells expressing shVGLL4 or shCtBP2, as demonstrated by Oil Red O staining (Fig. 7, A and B). Also, reduced PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FABP4 protein levels caused by TEAD4 overexpression were rescued by VGLL4 or CtBP2 depletion (Fig. 7C). Consistent with these results, knockdown of VGLL4 or CtBP2 expression almost completely impaired the trans-inactive effect on the PPARγ promoter upon TEAD4 overexpression by PPARγ-Luc assay (Fig. 7D), providing the molecular basis for the phenotypical observations in Fig. 7, A–C. Taken together, these findings indicate that VGLL4 and CtBP2 are essential TEAD4 cofactors and that the TEAD4 inhibitory function on adipogenesis depends on both VGLL4 and CtBP2.

Figure 7.

VGLL4 and CtBP2 are indispensable for TEAD4-mediated inhibition of adipogenesis. A and B, Oil Red O staining of lentivirus-mediated knockdown of VGLL4 or CtBP2 in stably overexpressing TEAD4 3T3-L1 cell lines after adipogenic mixture induction for 7 days (A) and quantification by measurement of the absorbance at 510 nm (B). ***, p < 0.001 by Student's t test; *, p < 0.05 by Student's t test. C, immunoblot analysis of TEAD4, VGLL4, CtBP2, PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FABP4 expression in the above cell samples. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The positions of protein molecular mass markers are indicated on the right. IB, immunoblot; MW, molecular weight. D, PPARγ-Luc assay of endogenous VGLL4 or CtBP2 knockdown function on the trans-inactive effect caused by TEAD4 overexpression in 293T cells. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001 by Student's t test; *, p < 0.05 by Student's t test.

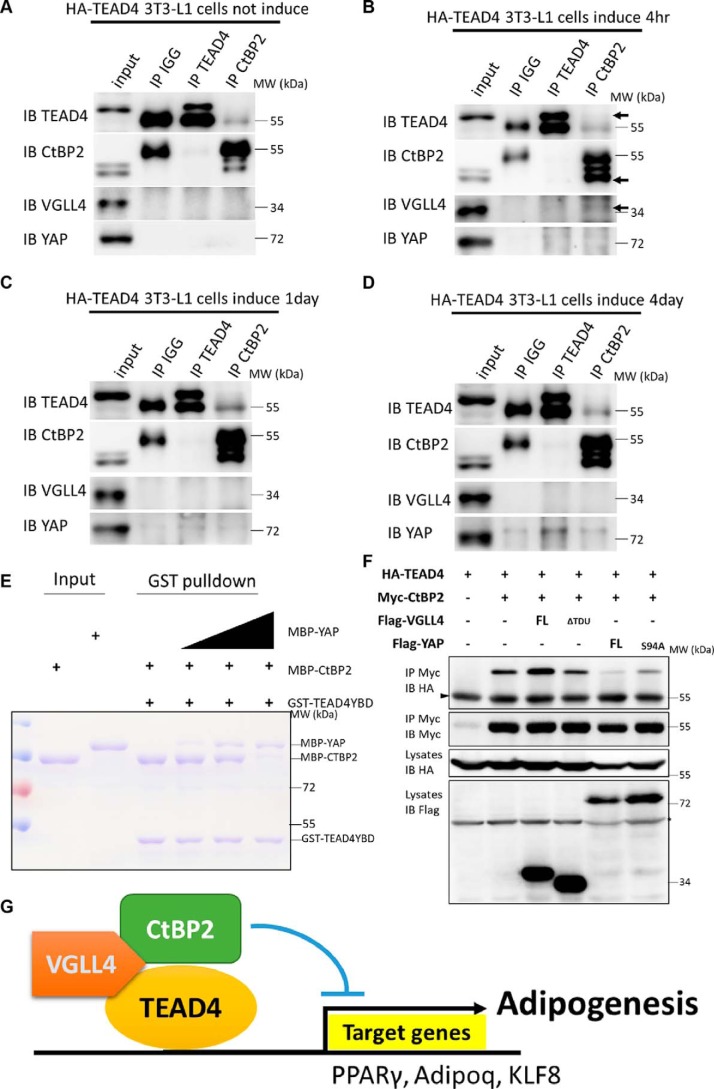

TEAD4 dynamically binds to CtBP2 and YAP during adipogenesis

Our results identified a TEAD4 cofactor, CtBP2, that is indispensable for TEAD4 function in adipogenesis. In addition, there are two known TEAD4 cofactors, YAP and VGLL4. Given that YAP is also a modulator in this process (27), how these three TEAD4 co-regulators cooperate with each other awaits further study. Our results suggest that TEAD4 binding to target genes is a dynamic process as adipogenesis progresses. We performed endogenous co-IP using TEAD4 and CtBP2 antibodies in stably TEAD4-expressing 3T3-L1 cells. Interestingly, TEAD4 did not interact with its cofactors, including CtBP2, VGLL4, and YAP, in normal preadipocytes (Fig. 8A). After adipogenic induction for 4 h, when preadipocytes were at the early stage of adipogenesis, interaction between TEAD4 and CtBP2 and VGLL4 was obviously detected (Fig. 8B), consistent with the ChIP-qPCR results acquired from TEAD4-mediated PPARγ promotor activity at early adipogenesis (Fig. 6F). At this stage, no (or very little) interaction between TEAD4 and YAP was detected (Fig. 8B), suggesting that CtBP2 is the key cofactor for TEAD4. As adipogenesis proceeds, the interaction between TEAD4 and CtBP2 or VGLL4 becomes weaker, whereas TEAD4 co-immunoprecipitated stronger with YAP (Fig. 8, C and D). The binding strength between TEAD4 and VGLL4-CtBP2 correlates with TEAD4's occupancy of its target gene promoters (Fig. 6F), demonstrating that CtBP2 and VGLL4 act as cofactors to inhibit TEAD4-mediated adipogenesis.

Figure 8.

TEAD4 dynamically binds to CtBP2 and YAP during adipogenesis. A–D, endogenous co-IP using TEAD4 and CtBP2 antibodies in stably overexpressing TEAD4 3T3-L1 cells without adipogenic mixture induction (A), after mixture induction for 4 h (B), after mixture induction for 1 day (C), and after mixture induction for 4 days (D). TEAD4, CtBP2, or IgG antibodies were incubated with cell lysates stably expressing TEAD4 and analyzed by co-IP. The arrowheads indicate the binding positions. IB, immunoblot; MW, molecular weight. E, dosage GST pulldown assay to detect the effect of YAP on the interaction between TEAD4 and CtBP2. MBP-CtBP2 and dosage-increased MBP-YAP were pulled down by GST-TEAD4YBD, followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. F, co-IP assay to detect YAP Ser-94 site function and its antagonism effect with CtBP2 for TEAD4 binding. The indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T cells and analyzed by co-IP. The arrowhead indicates the IgG heavy chain, and the asterisk denotes the nonspecific band. G, model showing that the transcription factor TEAD4 cooperates with its cofactors VGLL4 and CtBP2 to repress adipogenesis during 3T3-L1 differentiation. As 3T3-L1 cells undergo adipogenesis, TEAD4 is highly expressed, and then VGLL4 mediates TEAD4's recruitment of CtBP2 to form a ternary complex and bind to PPARγ/Adipoq/KLF8 promotor regions to inhibit their activities, resulting in inhibition of adipogenesis.

Previous studies have demonstrated that VGLL4 and YAP compete for TEAD4 binding (40–42). Next, we sought to determine how CtBP2 and YAP coordinate the interaction with TEAD4. To address this question, we dissected the interplay between CtBP2, YAP, and TEAD4 using purified recombinant proteins. As shown by a dose-dependent GST pulldown assay, YAP readily competed with CtBP2 for TEAD4 binding in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8E), suggesting that YAP has tighter binding with TEAD4. Previous studies have suggested that the YAP Ser-94 site mediates its binding to TEAD4 (44). The YAPS94A mutant protein was then created and tested. Despite the fact that YAPS94A still competes with CtBP2 for TEAD4 binding, the mutation S94A dramatically abolished the antagonistic effect of YAP on CtBP2 binding to TEAD4 (Fig. 8F), indicating that YAP partially competes with CtBP2 for TEAD4 binding through its interaction with TEAD4. Collectively, these results shed light on the dynamic interaction between TEAD4 and its cofactors.

Discussion

TEAD4 is a novel adipogenic regulator and modulates the early stage of adipogenesis

Transcription factor TEADs (1–4) play essential roles in a variety of physiological processes, including myogenesis, cardiogenesis, and development of the neural crest, notochord, and trophectoderm. Here we demonstrate a novel function of TEADs in regulating adipogenesis. Adipogenesis consists of lineage determination and terminal differentiation. We find that depletion of TEADs enhances adipogenesis and induces the expression of adipogenic markers, including PPARγ (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1, A–C). PPARγ is a master regulator of adipogenesis, and its expression modulates preadipocyte differentiation (3, 5). We show that TEAD4 directly targets PPARγ activity and acts as a regulator at the early stage of adipogenesis (Fig. 6D). Before adipogenic induction, TEAD4 is required for blocking adipogenesis, as lack of TEAD4 promotes adipogenesis. When adipogenesis is induced by adipogenic mixtures at the early stage, the TEAD4 protein level is dramatically increased and binds to the promoters of adipogenic genes (Figs. 1A and 6D). We reason that these phenomena are due to negative feedback regulation. As adipogenesis proceeds, the interaction between TEAD4 and its cofactor CtBP2 is weakened, and its binding to the PPARγ promoter is gradually relieved (Fig. 6F). Based on these findings, we demonstrate that TEAD4 is a novel negative regulator of PPARγ and that its expression provides feedback regulation and is crucial for adipogenesis.

Default repression of adipogenesis mediated by the TEAD4 transcriptional complex

Multiple transcription-based pathways orchestrate repression as the default state during development, such as the Hedgehog, Wnt and Notch signaling pathways (54, 55). Recent studies have indicated that Sd (the TEAD homolog in Drosophila) or TEAD mediates default repression in the regulation of cell proliferation (41, 42). Here, our findings further support the idea in the context of cell differentiation. The results from our microarray assay suggest that a set of adipogenic genes or regulators is strongly activated upon TEAD4 knockdown and that adipogenesis-related pathways are highly enriched at the same time (Fig. 2, A and B), implying a repressor role of TEAD4 in adipogenesis. We demonstrate that TEAD4 negatively regulates adipogenesis and that its cofactors VGLL4 and CtBP2 are indispensable for the function of TEAD4 in adipogenesis, as depletion of either one impairs TEAD4-mediated adipogenesis repression (Fig. 7, A–D). Furthermore, CtBP2 is identified as a novel TEAD4 binding partner, and their interaction is mediated by the adaptor protein VGLL4. This ternary complex synergistically inhibits adipogenesis and PPARγ promoter activity. In this process, CtBP2 functions as a TEAD4 corepressor and aids to regulate TEAD4-mediated default repression. VGLL4, a known antagonist of YAP for TEAD4 binding, facilitates TEAD4 function by enhancing TEAD4 and CtBP2 binding. All of these findings suggest that TEADs mediate default repression of adipogenesis.

TEAD4 function is regulated through dynamic recruitment of diverse cofactors in different physiological processes

As a transcription factor, TEAD4's function depends on its coregulators. YAP, as a general coactivator of TEADs, interacts with TEADs and induces the expression of proliferation-promoting or anti-apoptotic genes (56). CTGF is commonly considered a direct TEAD target gene essential for cell proliferation (35). However, during adipogenesis, we find that TEAD4 targets the PPARγ promoter at the early stage of adipogenesis (4 h) and relieves its recruitment to the CTGF promoter (Fig. 6F). In addition, the TEAD4 protein level preceded the elevation in PPARγ expression, whereas the CTGF protein level decreased during adipogenesis, showing the reverse trend with PPARγ (Fig. 1A). These findings suggest that TEAD4 shifts its target gene selection from CTGF to PPARγ at early adipogenesis. At the early stage of adipogenesis, VGLL4 and CtBP2 act as TEAD4 binding co-factors rather than YAP, although YAP has a higher binding affinity for TEAD4 than CtBP2 (Fig. 8, B and E). CtBP2 is a known transcriptional corepressor inhibiting PPARγ activity by recruiting several histone-modifying enzymes to silence the expression of target genes (17, 21). We find that CtBP2 replaces YAP as a TEAD4 cofactor and exerts its inhibition role during the initial phase of 3T3-L1 differentiation. In the later phase, YAP may compete with CtBP2 for TEAD4 binding and bind to TEAD4 again (Fig. 8, D and E). These findings suggest a potential model for TEAD recruitment of different cofactors in diverse physiological processes. Therefore, it would be interesting to investigate further how TEADs work with YAP and CtBP2 differently in the regulation of cell proliferation.

The role of the Hippo pathway in adipogenesis remains poorly explored. It has been shown that Hippo pathway activation is required for adipogenesis, and YAP has been found to modulate adipogenesis (27). It has been reported that SOX2 regulates YAP1 expression to determine cell fate in the osteo-adipo Lineage. However, the results of overexpression of SOX2 facilitating adipogenesis and inducing YAP1 expression and overexpression of YAP1 inhibiting adipogenesis seem contradictory, and whether YAP's function in this process depends on TEADs has not yet been clarified (27). Our report characterized a novel TEAD binding cofactor, CtBP2, and suggests that TEAD4-mediated regulation of adipogenesis is independent of YAP and works via the formation of a ternary complex comprising TEAD4, VGLL4, and CtBP2. Our finding is consistent with previous findings that the Hippo components MST2 and SAV1 interact with PPARγ and promote its activity (29). MST2 and SAV1 are Hippo-signaling upstream kinases and keep target genes inactivated through phosphorylation, which is in line with TEAD depletion. In our murine adipogenesis system, we propose a novel role for a downstream Hippo-signaling TEAD4–VGLL4–CtBP2 transcriptional repressor complex that has a critical function in physiological process.

To summarize, adipogenesis regulation is a complex network, and adipogenic homeostasis is controlled by multiple signaling pathways and different groups of transcription factors. We report a novel function of TEADs that work as default repressors during adipogenesis by recruiting VGLL4 and CtBP2 to form a transcriptional repressor complex, which is independent of YAP activity. Also, TEADs inhibit adipogenesis by directly targeting adipogenic factors. These results reveal new insights into the relationship between adipogenesis and Hippo signaling.

Materials and methods

Plasmids and cloning

The TEAD4 HA-tagged-pLVX plasmid was a gift from Dr. Ji's laboratory and was introduced into the pCDNA3.1-Myc or pcDNA3.1-FLAG vector by using PCR and the restriction enzymes BamHI and XhoI. Myc/FLAG-tagged pcDNA3.1 CtBP2 and VGLL4 were cloned from 293T cDNA by PCR and recombinase. All TEAD4/VGLL4/CtBP2/YAP truncation forms (TEAD4Y429H/TEAD4mNLS/TEAD4-N/TEAD4-C, CtBP2 N-terminal/CtBP2 C-terminal, YAPS94A, and VGLL4ΔTDU/VGLL4-N/VGLL4-C) were constructed according to standard protocols. Lentiviral and prokaryotic protein expression plasmids of these genes were subcloned from pcDNA3.1 to pLEX or GST/MBP-pGEX4.1 vectors, respectively. All shRNA sequences are shown in the Table S2.

Cell culture, transfection, and lentiviral infection

Human embryonic kidney 293T and 3T3-L1 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Plasmid transfections were performed using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions in 293T cells. Supernatants containing recombinant pLKO.1 (for knockdown) or pLEX (for overexpression) plasmid viruses were packed in 293T cells, and then lentivirus-mediated knockdown or overexpression 3T3-L1 cell lines were established by lentivirus infection and puromycin (5 μg/ml) selection.

Adipogenesis and Oil Red O staining

Murine 3T3-L1 cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% calf serum to confluency for 24–48 h and then switched into induction medium containing 10% FBS and adipogenesis induction mixture, which was half the concentration of the standard induction mixture. The standard induction mixture containing 10 μg/ml insulin (I5500, Sigma), 0.5 mm IBMX (I7018, Sigma), and 1 μm dexamethasone (D4902, Sigma). After 3 days, the medium was changed to complete DMEM containing 10% FBS. Further adipocyte differentiation and maturation was performed in fresh culture medium.

The adipocyte differentiation degree was confirmed by staining for triglycerides with Oil Red O. 3T3-L1 cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and mature adipocytes were stained by Oil Red O. Lipid droplet accumulation was then quantified by measurement of the optical density at 510 nm.

RNA extraction, microarray analysis, and quantitative RT-PCR

RNAs isolated from adipogenic mixture–induced 3T3-L1 cells (each sample was a pool of three different samples) were subjected to microarray analysis and hybridization according to the manufacturer's protocol (Arraystar). Differentially expressing mRNAs with a -fold change of more than 2-fold were picked up for further bioinformatics analysis. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA for qRT-PCR analysis. Reverse transcription reactions using 0.5 μg of RNA were performed with ReverTra Ace® qRT-PCR Master Mix with gDNA Remover (Toyobo, FSQ-301) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed in the BioRAD9600 Detection System using SYBR Green Real-Time PCR Master Mix (Toyobo, QPK-201).

Bioinformatics analysis and target prediction

Online DAVID online Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis was performed to show possible signaling pathways regulated by knockdown of TEAD4, YAP, and VGLL4 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) (57, 58). Venn analysis was performed to show target gene overlap (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html)4 (59).

Luciferase assay

For Dual-Luciferase reporter assays, plasmids were transfected in 293T cells together with the PPARγ-Luc reporter and Renilla luciferase, which was used to normalize the transfection efficiency. After 48 h, cell lysates were harvested, and Dual-Luciferase activities were measured according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega).

Co-IP, Western blotting, and immunostaining

For co-immunoprecipitation, 293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids by Lipofectamine and cultured for 48 h. Next, cells were lysed in NP-40 buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 1 mm sodium vanadate, 0.1 m NaCl, 1% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 1.5 mm EDTA, 10 mm sodium fluoride, and 1% protease inhibitor mixture) for 30 min at 4 °C. Lysates were then incubated with anti-HA (Sigma), anti-FLAG (Sigma), anti-Myc (Sigma), or endogenous TEAD4 (Abcam, ab58310)/CtBP2 antibodies for 2 h or overnight at 4 °C. Protein A/G–agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added and incubated for another 1 h at 4 °C. Afterward, beads were washed three times with NP-40 buffer and analyzed by Western blot assay. Western blots were performed according to standard protocols.

ChIP

ChIP experiments were carried out in 3T3-L1 cells according to a standard protocol. The cell lysate was sonicated for 35 min (30 s on/30 s off), and chromatin was divided into fragments ranging mainly from 100 to 300 bp in length. Immunoprecipitation was then performed by using antibodies against TEAD4 (Abcam, ab58310), and normal IgG was used as a control. Real-time PCRs were performed on a Bio-Rad 9600 Detection System using Roche SYBR Green mixture. The primers used for the ChIP-PCR analysis are listed in Table S3.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± S.D. on the basis of three independent experiments. Statistical significance between experimental groups was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

Author contributions

W. Z., Z. F., and L. Z. conceptualization; W. Z., X. M., and L. H. resources; W. Z. and L. Z. data curation; W. Z. software; W. Z. and L. Z. formal analysis; W. Z. validation; W. Z., J. X., J. L., T. G., D. J., X. F., W. W., M. Y., L. G., Z. W., M. S. H., Y. Z., Z. F., and L. Z. investigation; W. Z. visualization; W. Z., M. S. H., Y. Z., Z. F., and L. Z. methodology; W. Z. writing-original draft; W. Z. writing-review and editing; Z. F. and L. Z. supervision; L. Z. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Zhaoyuan Hou for providing some adipogenic reporters and plasmids. We also thank Dr. Jianping Ding for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB19000000), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0103601), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31625017 and 31530043), the Cross- and Co-operation in Science and Technology Innovation Team Project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences/SAFEA International Partnership Program for Creative Research Teams. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S6 and Tables S1–S3.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party–hosted site.

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor

- C/EBP

- CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein

- KLF

- Krüppel-like factor

- CtBP

- C-terminal binding protein

- YAP

- Yes-associated protein

- VGLL

- vestigial-like

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- KEGG

- Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- NLS

- nuclear localization sequence

- IVTT

- in vitro transcription and translation

- aa

- amino acids

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- cDNA

- complementary DNA

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- IBMX

- 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- RT-qPCR

- quantitative real-time PCR

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein.

References

- 1. Danforth E., Jr. (2000) Failure of adipocyte differentiation causes type II diabetes mellitus? Nat. Genet. 26, 13 10.1038/79111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sarjeant K., and Stephens J. M. (2012) Adipogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a008417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosen E. D., and MacDougald O. A. (2006) Adipocyte differentiation from the inside out. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 885–896 10.1038/nrm2066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Farmer S. R. (2006) Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab. 4, 263–273 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mota de Sá P., Richard A. J., Hang H., and Stephens J. M. (2017) Transcriptional regulation of adipogenesis. Compr. Physiol. 7, 635–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Floyd Z. E., and Stephens J. M. (2003) STAT5A promotes adipogenesis in nonprecursor cells and associates with the glucocorticoid receptor during adipocyte differentiation. Diabetes 52, 308–314 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Darlington G. J., Ross S. E., and MacDougald O. A. (1998) The role of C/EBP genes in adipocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 30057–30060 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gao H., Mejhert N., Fretz J. A., Arner E., Lorente-Cebrián S., Ehrlund A., Dahlman-Wright K., Gong X., Strömblad S., Douagi I., Laurencikiene J., Dahlman I., Daub C. O., Rydén M., Horowitz M. C., and Arner P. (2014) Early B cell factor 1 regulates adipocyte morphology and lipolysis in white adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 19, 981–992 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu Z., and Wang S. (2013) Role of Kruppel-like transcription factors in adipogenesis. Dev. Biol. 373, 235–243 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schupp M., Cristancho A. G., Lefterova M. I., Hanniman E. A., Briggs E. R., Steger D. J., Qatanani M., Curtin J. C., Schug J., Ochsner S. A., McKenna N. J., and Lazar M. A. (2009) Re-expression of GATA2 cooperates with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ depletion to revert the adipocyte phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 9458–9464 10.1074/jbc.M809498200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kang S., Akerblad P., Kiviranta R., Gupta R. K., Kajimura S., Griffin M. J., Min J., Baron R., and Rosen E. D. (2012) Regulation of early adipose commitment by Zfp521. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001433 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Choy L., and Derynck R. (2003) Transforming growth factor-β inhibits adipocyte differentiation by Smad3 interacting with CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) and repressing C/EBP transactivation function. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 9609–9619 10.1074/jbc.M212259200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li X., Huang H. Y., Chen J. G., Jiang L., Liu H. L., Liu D. G., Song T. J., He Q., Ma C. G., Ma D., Song H. Y., and Tang Q. Q. (2006) Lactacystin inhibits 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation through induction of CHOP-10 expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 350, 1–6 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sue N., Jack B. H., Eaton S. A., Pearson R. C., Funnell A. P., Turner J., Czolij R., Denyer G., Bao S., Molero-Navajas J. C., Perkins A., Fujiwara Y., Orkin S. H., Bell-Anderson K., and Crossley M. (2008) Targeted disruption of the basic Kruppel-like factor gene (Klf3) reveals a role in adipogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 3967–3978 10.1128/MCB.01942-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yu C., Markan K., Temple K. A., Deplewski D., Brady M. J., and Cohen R. N. (2005) The nuclear receptor corepressors NCoR and SMRT decrease peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma transcriptional activity and repress 3T3-L1 adipogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 13600–13605 10.1074/jbc.M409468200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fajas L., Egler V., Reiter R., Hansen J., Kristiansen K., Debril M. B., Miard S., and Auwerx J. (2002) The retinoblastoma-histone deacetylase 3 complex inhibits PPARγ and adipocyte differentiation. Dev. Cell 3, 903–910 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00360-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jack B. H., Pearson R. C., and Crossley M. (2011) C-terminal binding protein: a metabolic sensor implicated in regulating adipogenesis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 43, 693–696 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chinnadurai G. (2007) Transcriptional regulation by C-terminal binding proteins. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 1593–1607 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kiskinis E., Hallberg M., Christian M., Olofsson M., Dilworth S. M., White R., and Parker M. G. (2007) RIP140 directs histone and DNA methylation to silence Ucp1 expression in white adipocytes. EMBO J. 26, 4831–4840 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kajimura S., Seale P., Tomaru T., Erdjument-Bromage H., Cooper M. P., Ruas J. L., Chin S., Tempst P., Lazar M. A., and Spiegelman B. M. (2008) Regulation of the brown and white fat gene programs through a PRDM16/CtBP transcriptional complex. Genes Dev. 22, 1397–1409 10.1101/gad.1666108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Turner J., and Crossley M. (1998) Cloning and characterization of mCtBP2, a co-repressor that associates with basic Kruppel-like factor and other mammalian transcriptional regulators. EMBO J. 17, 5129–5140 10.1093/emboj/17.17.5129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bennett C. N., Ross S. E., Longo K. A., Bajnok L., Hemati N., Johnson K. W., Harrison S. D., and MacDougald O. A. (2002) Regulation of Wnt signaling during adipogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30998–31004 10.1074/jbc.M204527200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Margoni A., Fotis L., and Papavassiliou A. G. (2012) The transforming growth factor-β/bone morphogenetic protein signalling pathway in adipogenesis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell B 44, 475–479 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bi P., Yue F., Karki A., Castro B., Wirbisky S. E., Wang C., Durkes A., Elzey B. D., Andrisani O. M., Bidwell C. A., Freeman J. L., Konieczny S. F., and Kuang S. (2016) Notch activation drives adipocyte dedifferentiation and tumorigenic transformation in mice. J. Exp. Med. 213, 2019–2037 10.1084/jem.20160157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liang S., Chen R. T., Zhang D. P., Xin H. H., Lu Y., Wang M. X., and Miao Y. G. (2015) Hedgehog signaling pathway regulated the target genes for adipogenesis in silkworm Bombyx mori. Insect Sci. 22, 587–596 10.1111/1744-7917.12164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hong J. H., Hwang E. S., McManus M. T., Amsterdam A., Tian Y., Kalmukova R., Mueller E., Benjamin T., Spiegelman B. M., Sharp P. A., Hopkins N., and Yaffe M. B. (2005) TAZ, a transcriptional modulator of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Science 309, 1074–1078 10.1126/science.1110955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seo E., Basu-Roy U., Gunaratne P. H., Coarfa C., Lim D. S., Basilico C., and Mansukhani A. (2013) SOX2 regulates YAP1 to maintain stemness and determine cell fate in the osteo-adipo lineage. Cell Rep. 3, 2075–2087 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yu F. X., Zhang Y., Park H. W., Jewell J. L., Chen Q., Deng Y., Pan D., Taylor S. S., Lai Z. C., and Guan K. L. (2013) Protein kinase A activates the Hippo pathway to modulate cell proliferation and differentiation. Genes Dev. 27, 1223–1232 10.1101/gad.219402.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Park B. H., Kim D. S., Won G. W., Jeon H. J., Oh B. C., Lee Y., Kim E. G., and Lee Y. H. (2012) Mammalian ste20-like kinase and SAV1 promote 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation by activation of PPARγ. PLoS ONE 7, e30983 10.1371/journal.pone.0030983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang J., Zhang F., Yang H., Wu H., Cui R., Zhao Y., Jiao C., Wang X., Liu X., Wu L., Li G., and Wu X. (2018) Effect of TEAD4 on multilineage differentiation of muscle-derived stem cells. Am. J. Transl. Res. 10, 998–1011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yu F. X., Zhao B., and Guan K. L. (2015) Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue homeostasis, and cancer. Cell 163, 811–828 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yin M., and Zhang L. (2011) Hippo signaling: a hub of growth control, tumor suppression and pluripotency maintenance. J. Genet. Genomics 38, 471–481 10.1016/j.jgg.2011.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang L., Ren F., Zhang Q., Chen Y., Wang B., and Jiang J. (2008) The TEAD/TEF family of transcription factor Scalloped mediates Hippo signaling in organ size control. Dev. Cell 14, 377–387 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou Y., Huang T., Cheng A. S., Yu J., Kang W., and To K. F. (2016) The TEAD family and its oncogenic role in promoting tumorigenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhao B., Ye X., Yu J., Li L., Li W., Li S., Yu J., Lin J. D., Wang C. Y., Chinnaiyan A. M., Lai Z. C., and Guan K. L. (2008) TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev. 22, 1962–1971 10.1101/gad.1664408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dong J., Feldmann G., Huang J., Wu S., Zhang N., Comerford S. A., Gayyed M. F., Anders R. A., Maitra A., and Pan D. (2007) Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell 130, 1120–1133 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Home P., Saha B., Ray S., Dutta D., Gunewardena S., Yoo B., Pal A., Vivian J. L., Larson M., Petroff M., Gallagher P. G., Schulz V. P., White K. L., Golos T. G., Behr B., and Paul S. (2012) Altered subcellular localization of transcription factor TEAD4 regulates first mammalian cell lineage commitment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7362–7367 10.1073/pnas.1201595109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jacquemin P., Hwang J. J., Martial J. A., Dollé P., and Davidson I. (1996) A novel family of developmentally regulated mammalian transcription factors containing the TEA/ATTS DNA binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21775–21785 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Benhaddou A., Keime C., Ye T., Morlon A., Michel I., Jost B., Mengus G., and Davidson I. (2012) Transcription factor TEAD4 regulates expression of myogenin and the unfolded protein response genes during C2C12 cell differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 19, 220–231 10.1038/cdd.2011.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jiao S., Wang H., Shi Z., Dong A., Zhang W., Song X., He F., Wang Y., Zhang Z., Wang W., Wang X., Guo T., Li P., Zhao Y., Ji H., et al. (2014) A peptide mimicking VGLL4 function acts as a YAP antagonist therapy against gastric cancer. Cancer Cell 25, 166–180 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guo T., Lu Y., Li P., Yin M. X., Lv D., Zhang W., Wang H., Zhou Z., Ji H., Zhao Y., and Zhang L. (2013) A novel partner of Scalloped regulates Hippo signaling via antagonizing Scalloped-Yorkie activity. Cell Res. 23, 1201–1214 10.1038/cr.2013.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Koontz L. M., Liu-Chittenden Y., Yin F., Zheng Y., Yu J., Huang B., Chen Q., Wu S., and Pan D. (2013) The Hippo effector Yorkie controls normal tissue growth by antagonizing scalloped-mediated default repression. Dev. Cell 25, 388–401 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang W., Gao Y., Li P., Shi Z., Guo T., Li F., Han X., Feng Y., Zheng C., Wang Z., Li F. M., Chen H., Zhou Z., Zhang L., and Ji H. (2014) VGLL4 functions as a new tumor suppressor in lung cancer by negatively regulating the YAP-TEAD transcriptional complex. Cell Res. 24, 331–343 10.1038/cr.2014.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pobbati A. V., Chan S. W., Lee I., Song H., and Hong W. (2012) Structural and functional similarity between the Vgll1-TEAD and the YAP-TEAD complexes. Structure 20, 1135–1140 10.1016/j.str.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li N., Yu N., Wang J., Xi H., Lu W. Q., Xu H., Deng M., Zheng G., and Liu H. (2015) miR-222/VGLL4/YAP-TEAD1 regulatory loop promotes proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer cells. Am. J. Cancer Res. 5, 1158–1168 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mann K. M., Ward J. M., Yew C. C., Kovochich A., Dawson D. W., Black M. A., Brett B. T., Sheetz T. E., Dupuy A. J., Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative, Chang D. K., Biankin A. V., Waddell N., Kassahn K. S., Grimmond S. M., et al. (2012) Sleeping Beauty mutagenesis reveals cooperating mutations and pathways in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 5934–5941 10.1073/pnas.1202490109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tang T., Zhang J., Yin J., Staszkiewicz J., Gawronska-Kozak B., Jung D. Y., Ko H. J., Ong H., Kim J. K., Mynatt R., Martin R. J., Keenan M., Gao Z., and Ye J. (2010) Uncoupling of inflammation and insulin resistance by NF-κB in transgenic mice through elevated energy expenditure. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4637–4644 10.1074/jbc.M109.068007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Song B. Q., Chi Y., Li X., Du W. J., Han Z. B., Tian J. J., Li J. J., Chen F., Wu H. H., Han L. X., Lu S. H., Zheng Y. Z., and Han Z. C. (2015) Inhibition of Notch signaling promotes the adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells through autophagy activation and PTEN-PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 36, 1991–2002 10.1159/000430167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lee Y. H., Kim S. H., Lee Y. J., Kang E. S., Lee B. W., Cha B. S., Kim J. W., Song D. H., and Lee H. C. (2013) Transcription factor Snail is a novel regulator of adipocyte differentiation via inhibiting the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 70, 3959–3971 10.1007/s00018-013-1363-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dai Z., Tang H., Pan Y., Chen J., Li Y., and Zhu J. (2018) Gene expression profiles and pathway enrichment analysis of human osteosarcoma cells exposed to sorafenib. FEBS Open Bio 8, 860–867 10.1002/2211-5463.12428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tian W., Yu J., Tomchick D. R., Pan D., and Luo X. (2010) Structural and functional analysis of the YAP-binding domain of human TEAD2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 7293–7298 10.1073/pnas.1000293107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Saijo K., Collier J. G., Li A. C., Katzenellenbogen J. A., and Glass C. K. (2011) An ADIOL-ERβ-CtBP transrepression pathway negatively regulates microglia-mediated inflammation. Cell 145, 584–595 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Beyer T. A., Weiss A., Khomchuk Y., Huang K., Ogunjimi A. A., Varelas X., and Wrana J. L. (2013) Switch enhancers interpret TGF-β and Hippo signaling to control cell fate in human embryonic stem cells. Cell Rep. 5, 1611–1624 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Affolter M., Pyrowolakis G., Weiss A., and Basler K. (2008) Signal-induced repression: the exception or the rule in developmental signaling? Dev. Cell 15, 11–22 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Barolo S., and Posakony J. W. (2002) Three habits of highly effective signaling pathways: principles of transcriptional control by developmental cell signaling. Genes Dev. 16, 1167–1181 10.1101/gad.976502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mo J. S., Park H. W., and Guan K. L. (2014) The Hippo signaling pathway in stem cell biology and cancer. EMBO Rep. 15, 642–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Huang D. W., Sherman B. T., and Lempicki R. A. (2009) Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57 10.1038/nprot.2008.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Huang D. W., Sherman B. T., and Lempicki R. A. (2009) Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 1–13 10.1093/nar/gkn923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Oliveros J.C. (2007–2015) Venny. An interactive tool for comparing lists with Venn's diagrams. http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.