Abstract

QT prolongation constitutes one of the most frequently encountered electrical disorders of the myocardium. This is due not only to the presence of several associated congenital syndrome but also, and mainly, due to the QT-prolonging effects of several acquired conditions, such as ischaemia and heart failure, as well as multiple medications from widely different categories. Propensity of repolarization disturbances to arrhythmia appears to be inherent in the function of and electrophysiology of the myocardium. In the present review the issue of QT prolongation will be addressed in terms of pathophysiology, arrhythmogenesis, treatment and risk stratification approaches. Although already discussed in literature, it is hoped that the mechanistic approach of the present review will assist in improved understanding of the underlying changes in electrophysiology, as well as the rationale for current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: QT prolongation, action potential duration, restitution curve, long QT syndromes, sudden cardiac death

Ventricular repolarization, as opposed to depolarization, is not a triggered phenomenon following an orderly sequence, hence the dissimilarity between their inscribed electrocardiographic waves; rather, ventricular myocytes repolarize at a time and rate determined by their intrinsic electrophysiological properties (relative concentration of ion channel types and isoforms), as well as by the preceding electrical and mechanical events that affect the former. Given that different segments and layers of the myocardium have divergent baseline properties and consequently respond differently to stimuli, it is not surprising that several arrhythmic disorders of the myocardium, both congenital and acquired, are related to derangements in precisely this repolarization process.

More specifically, disorders may involve abnormal initial repolarization rate (phase 1 of the action potential — Brugada syndrome) or abnormally shortened/prolonged late repolarization (phase 3 — short and long QT syndromes, respectively). In the following short review, focused on QT prolongation, it will be attempted to summarise the underlying (patho)physiology of this entity and the extent to which it constitutes a problem with regard to both prevention and management of malignant, potentially lethal arrhythmic events in various substrates.

(Patho)Physiology of QT Prolongation and Related Arrhythmias

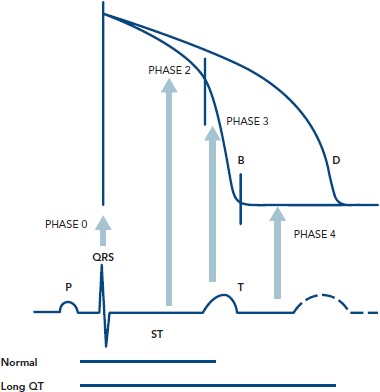

The surface ECG represents a time and space integral to the individual cells’ action potentials, with the ‘time’ parameter also incorporating the delay in activation between myocardial areas, as opposed to solely the time course of the phenomenon in each cell. Thus, the QRS complex reflects the summed depolarization (phase 0), the ST segment the transient current equilibrium leading to a brief electrical quiescence (phase 2) and the T wave the summed repolarization (phase 3) of the action potential (Figure 1). The TQ interval corresponds to phase 4 of the action potential.

Figure 1: Correlation Between Ventricular Cellular Action Potential and Surface ECG.

Adapted from Dilaveris, 2005[5]

The QT interval is a more or less easily identifiable segment in the ECG and thought to visualise the full cycle of ventricular depolarization and repolarization. It follows that even changes in the velocity of depolarization propagation (i.e. bundle/fascicle block) are prone to cause increases in the overall QT interval, not only by delaying cycle initiation for certain areas but also through a direct effect on ion movement (by affecting stretch-activated channels).

The normal sequence of repolarization[1,2] begins at the epicardial layer, moving (not propagating, except for the small contribution of gap junctions) towards the endocardium, based on the intrinsic action potential duration (APD) of the respective cells.[3] However, a defined population of cells, mainly located in the intermediate layers of myocardium (M cells), but also found in islets nearer the epi-and endocardium,[4,5] exhibits a more protracted action potential because of their unique ion channel properties, as explained later on. Thus, they form a layer, or area, more susceptible to causing unidirectional block (larger possibility for an extrasystole to fall into the absolute refractory period), all the more so if baseline APD prolongation exists. They may also potentially affect APD of neighbouring endo/epicardial cells though gap junction coupling.[4] Of crucial importance, APD in these cells is more susceptible to changes leading to its prolongation as compared to cells in the other myocardial layers.[4]

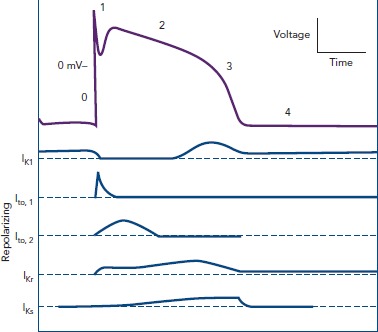

Regarding the ionic substrate, the plateau of action potential (phase 2) is due to antagonism between positive inward and outward (Figure 2) currents. More specifically, those generated by the sustained opening of long (L)-type calcium channels (then triggering sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release through ryanodine-sensitive calcium channels leading to excitation — contraction coupling), as well as a late sodium current (through the Nav1.5 channel also responsible for phase 0) on one hand and potassium currents on the other. The latter can be categorised as rapid (IKr) and slow (IKs) delayed currents, mediated by the HERG (new nomenclature Kv11.1) and KCNQ1 (new nomenclature Kv7.1) channels, respectively.[2] M cells mainly depend on IKr and not on IKs and therein lies their propensity for pronounced APD prolongation when conditions favour it, especially in cases where depolarizing currents (INa′, ICa — late sodium current has also been found inherently more potent in these cells, thus constituting a second mechanism accounting for the more prolonged baseline APD)[6,7] increase.[2] Crucially, IKs inhibition per se does not lead to significantly larger effects on M cells.[8] Thus, although prolonging the QT interval, it does not cause increased dispersion of repolarization in the absence of increased adrenergic stimulation. Indeed, when adrenergic stimulation is combined with Kv7.1 mutations there is a blunted response and consequently disproportionately long QT for the given heart rate.[9] The term ‘delayed’ refers to their timing in comparison to the transient outwards potassium currents ( Ito1 and Ito2 ) that are active during phase 1 (initial repolarization) of the action potential. Given that the latter are of interest in the pathophysiology of Brugada, rather than long QT, syndrome, we will not further discuss them.

Figure 2: Outward (Repolarizing) Potassium Currents Throughout the Cardiac Cycle.

Adapted from Koeppen and Stanton, 2010[104]

Repolarization (phase 3 of the action potential) occurs as the result of a net outward-directed positive current, i.e. net loss of positive ions. Eventually, the continued inactivation of sodium channels at high positive intracellular voltages and activation of potassium ones leads to a decrease in membrane voltage and movement towards the Nernst potential for K+ (given that permeability is at this phase practically limited to that ion alone). Inward rectifier (IKir) current through Kir voltage- and ligand-gated channels stabilises membrane potential (phase 4). Finally, cellular interdependence by means of connexin presence (allowing for current flow, and thus voltage equalisation — functional syncytium) and stretch-activated channels (nonspecific cationic channels leading to inward depolarizing currents) may lead to action potential changes secondary to extrinsic events.

Prolongation of the action potential can be appreciated in all cases where an increase in an inward positive or a decrease in an outward positive current occur. These are either the result of genetic mutations (gain/loss of function, abnormal intracellular trafficking), or the effects of acquired conditions. Tables 1 and 2 present the congenital genetic syndromes and acquired clinical conditions associated with QT prolongation, along with remarks concerning their underlying mechanisms. As evident from them, in addition to the well-established three major congenital long QT syndromes, there is a host of other ion currents and channels/transporters (such as adenosine triphosphate-gated K+ channels and Na+/Ca2+ antiporter) that become relevant in APD and QT prolongation in different nosological entities.

Table 1: Genetic Causes of QT Prolongation and Associated Syndromes.

| Syndrome | Gene/Protein | Function/Comments |

|---|---|---|

| LQTS1 | KCNQ1/Kv7.1 (alpha* subunit of IKs channel) | Reduced repolarization potential causes QT prolongation. T waves are broad and start close to QRS end ( IKr still functional).[8] Mainly associated with arrhythmias during prolonged sympathetic activation. Frequency 30–35 % of LQTS, penetrance 62 % |

| LQTS2 | KCNH2/Kv11.1 (alpha subunit of IKr channel) | Similar to LQTS1; however, T wave is farther off the QRS complex (only the slow rectifying current is active) and usually biphid.[8] Associated with arrhythmias following abrupt stimuli. Frequency 25–30 %, penetrance 75 % |

| LQTS3 | SCN5A/Nav1.5 (alpha subunit of sodium channels) | Gain of function mutations lead to APD. Associated with arrhythmias during bradycardia. A long ST interval (long plateau of action potential) along with a delayed, mostly normal, yet peaked, T wave (potassium currents normal) appreciated.[8] Frequency 5–10 % and penetrance 90 % |

| Patients with type 3 long QT syndrome tend to experience fewer, albeit more serious, arrhythmic events. This could be explained by the sensitivity of M cells to sodium currents during repolarization leading to pronounced prolongation of APD. Thus, it is more likely that upon return, the re-entrant wave will encounter refractory tissue, and thus stop propagating. However, if it does propagate, the steeper APD restitution curve[18,77,78] — as noted its initial part mainly depends on sodium currents[11] — renders wave break more probable, and thus favours degeneration into fibrillation. Given that the following syndromes are each estimated to occur in <1 % of congenital LQTS cases, a 25–40 % of these syndromes remains without established molecular cause | ||

| LQTS4 | ANKB/Ankyrin beta | Ankyrin mediates the attachment of integral membrane proteins (including channels) to the spectrin-actin based membrane cytoskeleton.[79] Mutations increases calcium (and sodium) currents (affects sodium/calcium exchanger and the sodium/potassium pump |

| LQTS5 | KCNE1/minK (beta — regulatory — subunit of IKs ) | A variation essentially of LQTS1 |

| When LQTS1 and LQTS5 are associated with deafness (inner ear hair cells’ action potential is, unusually, mediated by potassium influx), they constitute the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndromes, their more severe (in terms of prognosis) counterparts. Their mode of inheritance is autosomal recessive (since it requires either homozygosity for the mutation or compound heterozygosity), as opposed to autosomal dominant of all the other mentioned LQTS (collectively termed Romano– Ward syndrome) | ||

| LQTS6 | KCNE2/MiRP1 (beta — regulatory — subunit of IKr ) | A variation essentially of LQTS1 |

| LQTS7 | KCNJ2/Kir2.1 (alpha subunit of inward rectifier potassium ion channel) | Known as Andersen–Tawil syndrome, it is characterised by the triad of hypokalaemic periodic paralysis, potentially fatal cardiac ventricular ectopy and characteristic physical features (clinodactyly, micrognathia, low-set ears). Mutations either disrupt protein function, its trafficking to cell membrane or its association with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (the channel is both voltage-and ligand-gated), thus prolonging the terminal phase of repolarization |

| LQTS8 | CACNA1/Cav1.2 (alpha subunit of the long-type calcium channels) | Timothy syndrome.[80] In addition to arrhythmias (gain of function), there is also immunological deficiency and cognitive disorders, such as autism. Highly malignant, associated with early occurrence of arrhythmias[47] |

| Both LQTS7 and LQTS8 syndrome-associated genes have also been found inversely (in terms of function) mutated in Brugada syndrome forms.[81] | ||

| LQTS9 | CAV3/Caveolin 3 | Caveolins are scaffolding proteins for membrane invaginations (caveolae) involved in endocytosis and assembly of membrane proteins in specific membrane areas.[82–84 Mutations lead to altered Nav1.5 function (increase), and thus a variant of the LQTS3 |

| LQTS10 | SCN4B/(beta subunit of sodium channels) | Increased inwards sodium current, another variant of LQTS3 |

| LQTS11 | AKAP9/A-kinase anchor protein 9 | This protein binds to the regulatory subunit of protein kinase A, involved itself in adrenergic receptor signal transduction. A direct interaction with Kv7.1 (LQTS1) has also been described[85] |

| LQTS12 | SNTA1/Alpha-1-syntrophin | Cytoskeletal protein found at the inner surface of muscle fibres. Has been shown to interact and affect Nav1.5[86] (thus a variant of both LQTS3 and LQTS4) |

| Various other mutations leading to LQTS >12 have been reported. Several genes implicated in congenital long QT syndrome exhibit incomplete penetrance, and thus may both mask the syndrome and lead to sudden prolongation and arrhythmic events in the presence of even minor, normally harmless, precipitators.[87] Thus, it could be argued that myocardial repolarization is subject to Murphy’s Law, where everything that could go wrong does, at least in different scenarios. | ||

*alpha subunits are pore-forming subunits. APD = action potential prolongation; LQTS = congenital long QT syndrome.

Table 2: Acquired Long QT Causes.

| Cause | Comments |

|---|---|

| Drugs | Drugs that prolong the QT interval mainly do so by inhibiting IKr, thus mimicking a long QT syndrome type 2 phenotype.[33,88,89] This is attributable to the structure of this ionic channel, inasmuch as its wider pore allows for easier access of drug molecules to that critical part, and its content in aromatic amino acids favours interactions with aromatic moieties in exogenous molecules.[2] Although a host of medications may lead to QT prolongation,[90] and QT prolongation induction is the first cause of drug withdrawal by the Federal Drug Administration,[91] their actual torsadogenic potential differs widely inasmuch as: not all increase dispersion of repolarization, and several also inhibit ionic channels responsible for afterdepolarizations, thus preventing the triggering stimulus of the arrhythmia (amiodarone and ranolazine being prime examples of this). Thiopental prolongs QT, yet does so while reducing dispersion of repolarization via more pronounced effects on endo/epicardial cells (normally having shorter APD than M cells).[92] Several targeted anticancer drugs do prolong the QT interval[93] (histone deacetylase inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, antiangiogenic factors, farnesylation inhibitors), again through effects on the Kv11.1 channel (but not related to direct pore blockade). Event risk is highest during the first days of initiation of the QT prolonging agent (cohort effect? myocardial adaptation?)[94] |

| Inflammatory conditions | Thought to exert a negative effect on repolarization dispersion, mainly through production of radical oxygen species and activation of the sphingosine-1 pathway that downregulates Kv11.1, thus similar to drug effects (drugs may also act through the sphingosine pathway)[95] |

| Obesity | Obesity is linked to QT prolongation,[96] possibly through the effects of hyperinsulinemia either direct[97] or mediated by hypokalaemia.[98] Clinical significance of this association remains unknown |

| Heart failure | Reduced IKr and increased late INa.[2][4] These changes may represent adaptation attempts inasmuch as prolonged APD leads to prolonged increased intracellular calcium concentration, and thus potentiate actin-myosin interaction. Late sodium current may itself be a result of increased intracellular calcium given that it will cause the Na+/Ca2+ to operate in reverse, excreting 1 calcium ion for every three sodium ones entering the cell |

| Female sex | Effects of estradiol on potassium currents.[18] See female sex related paragraph in pathophysiology section |

| Hypokalaemia | Mimics effects of potassium channel mutations |

| Hypocalcaemia | Reduced negative feedback of intracellular calcium on long-type calcium channels that prolongs their open state. QT morphology will resemble that of LQTS3 |

| Hypomagnesemia | Magnesium is also known as ‘nature’s calcium inhibitor’, since release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum is inhibited by magnesium. Furthermore, it acts as a cofactor of sodium/potassium ATPase and at the same time increases potassium efflux by IK1 channels.[25] Moreover, it prevents potassium loss in nephrons, ameliorating hypokalaemia. These actions justify its use in the emergency treatment of LQTS, with the obvious exception of hypocalcaemia being the underlying cause |

| Bradycardia | Based on the normal APD restitution curve. Relevant especially if concomitant use of torsadogenic medication or congenital bradycardia-associated LQTS (such as LQTS3) |

| Ischaemia | Relative ischaemia (borders of scar) induces QT prolongation by activating sodium/hydrogen exchangers (to prevent intracellular acidosis. Moreover, it may induce increased dispersion of repolarization inasmuch as other mechanisms (opening of ATP-gated potassium channels) may induce shortening of APD.[99] On the contrary, complete ischaemia induces shortening of action potential until its eventual abolition. Thus acute/relative, but not chronic/complete, ischaemia has a high torsadogenic potential, a feature well-known in clinical cardiology practice |

| Hypothermia | Calcium ion channel aberrations |

| Hypothyroidism | Thyroid hormone positively controls the expression of calcium ATPase and phospholamban.[100,101] These proteins are involved in intracellular calcium level homeostasis by regulating its sequestration into the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Hypothyroidism leads, thus to decreased activity of these proteins, increasing calcium concentration during the repolarization phase of the cardiac cycle |

| A recent meta-analysis including almost 90,000 patients[102] found that hypokalaemia, use of diuretics, antiarrhythmic medications and QT prolonging medications of list 1 by CredibleMeds[90] were the factors most strongly associated with QT prolongation. On the contrary, weak evidence was found for history of a prolonged QT interval of even torsades, point either to the extrinsic, and thus modifiable, factors associated with QT prolongation or to the significant variability of the QT interval in the same individual | |

APD = action potential prolongation; ATP = antitachycardia pacing; LQTS = congenital long QT syndrome.

The duration of repolarization is substantially affected by the preceding diastolic interval (DI), as already mentioned, exhibiting restitution properties.[10] Their interdependence can be visualised by the APD = f(DI) curve (restitution curve). This curve, according to most, but not all,[11] authors has a rather simple, reverse exponential, and thus monotonic, form:[12]

The significance of studying its properties[13] lies in the fact that extrasystoles occurring early (i.e. with a short DI) lead to self-promoting instability regarding both APD and DI of subsequent cycles, eventually reaching a DI falling within the absolute refractory period, and thus causing conduction block. This can either initiate re-entry, should the refractory tissue be excited later on by the stimulus following a different pathway, or lead to degeneration of existing ventricular tachycardia into VF if it occurs along the tail of the spiral wave emanating from the central rotor. In terms of the restitution curve this translates into occurring at the steeper initial part of the curve, where the gradient of its tangent is >1.[10] Prolongation of the action potential, as in long QT syndromes, leads to steepening of the curve, thus increasing its first derivative (i.e. slope), rendering the condition f′(DI) > 1 valid for a broader area of DIs, and thus increasing the risk of an extrasystole inducing electrical instability. Individuals with known structural heart disease (ischaemic and dilated nonischaemic cardiomyopathy) have been found to exhibit an altered restitution curve, with a wider area where (more pronounced) alternans occurs.[14] Restitution function slightly differs in form between isolated cells and tissue samples, given the dampening/dispersing effect of gap junctions on cellular membrane voltage. Interestingly, it has been postulated that current methods for plotting the APD restitution curve are inherently flawed inasmuch as the rapid ventricular pacing involved leads to alteration in calcium cycling, in turn distorting measurements (thus the process itself affects the outcome, reminiscent of the Heisenberg principle).[15]

Given the absence of overall control and the deleterious effects of increased intracellular calcium, there is a tight regulation of repolarization on the cellular level. The cellular mechanisms involved in the restitution properties of the APD are thought to include all three main ions:[11] sodium for very short preceding DIs (the cycle in question will alter and be affected by Na+ kinetics since it will occur before complete inactivation of relevant channels — moreover it will decrease conduction velocity, further promoting potential for re-entry),[10,16] calcium for the intermediate part of the curve (with an effect depending on the onset timing of negative feedback mechanism linking intracellular calcium and calcium channel permeability) and potassium for longer DIs of the extrasystole. Thus, a simplified three-current model for the restitution curve as a function of the preceding DI can be constructed. (See figure 9 in Franz.[11] Note that curves do not represent temporally successive currents, rather they present the extent of each ion’s contribution to the alteration of the action potential form with regard to the prematurity of the extrasystole.)

Female sex appears to be associated with prolonged baseline QT interval[17] as well as increased risk for further QT prolongation and subsequent arrhythmogenesis, especially after adolescence.[18] Indeed, in a population with congenital QT prolongation (long QT syndromes 1–3) event rates were equal among sexes in the early and later years with a female predilection in the 20–50 age range.[19] This has been attributed to the effects of estradiol and testosterone on ionic currents given that the former inhibited all potassium currents while the latter enhanced IKs and inhibited ICaL.[20,21] However, androgen effects appear to be more significant inasmuch as virilised women and castrated men that regressed (regarding repolarization) to the phenotype of their reassigned gonadal sex.[22] To complicate matters, aromatase (converting testosterone to estradiol) is expressed in human ventricular myocytes, thus it is potentially the balance between sex hormones, rather than their separate effects that ultimately determine APD behaviour.[23]

What is the mechanistic sequence of events leading from QT prolongation to (polymorphic) ventricular tachycardia (‘torsade des pointes’) and potentially to degeneration into lethal fibrillation? Prolongation of APD leads to increased probability of L-type calcium channels reopening (as opposed to Nav1.5 these channels do not assume an inactive configuration, and thus may reopen if transmembrane voltage is still favourable). This could lead to an early afterdepolarization, either by itself or by the added contribution of the electrogenic sodium/calcium exchanger. This is facilitated by the triangulation of the action potential curve (increased duration of repolarization from between 30 % and 90 % of total process) observed during its prolongation, allowing for the relative refractory period to commence.[24] If timing is suitable, locating it to the steeper portion of the restitution curve, conduction block may occur, especially in the more affected M cells in either the initial or in subsequent cycles.[16] This is facilitated if the preceding action potential (n-1 where n is the action potential inducing the tachycardia) has been already prolonged following a previous (n-2) extrasystole (short-long-short phenomenon).[25] This block, in conjunction with the reduced conduction velocity though the tissue (due to less steep phase 0 upstroke since not all Nav1.5 channels have recovered) favours re-entry. Of note, it is APD dispersion, not prolongation per se, that renders the tissue prone to sustaining re-entry. (If the extend of APD prolongation was similar in the endo/epicardial layers, the re-entry circuit would likely be interrupted upon reaching them, arriving during refractoriness.)[8,24] Moreover, the short wavelength at the rotor leading edge, combined with the more prolonged APD of the M cells (area of unidirectional block) leads to rotor instability (local restitution curve derivative >1) and thus meandering and changes in its spatial orientation, yielding the well-described ECG feature of polymorphic tachycardia.[10] Should the curve shift to unstable areas in the arms of the rotor, this will lead to wave break, potential secondary rotor formation and, eventually, VF. Interestingly, abolishing both calcium and sodium mechanisms of restitution (but keeping conduction velocity stable) theoretically may prevent degeneration into VF (achievable with concomitant use of class IV and III antiarrhythmics — pharmacological defibrillation).[10] Alternatively, a triggered activity-related mechanism for polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) has been postulated (i.e. afterdepolarization in one area triggering afterdepolarization in a different myocardial segment, accounting for the ever-changing QRS morphology and reminiscent of bidirectional VT substrate), although substantial controversy exists regarding its contribution to arrhythmogenesis.[26–28]

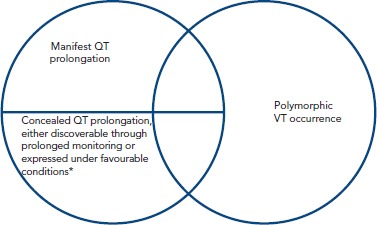

Figure 3: Relationship Between QT Prolongation and Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia.

*refers to concomitant presence of a second QT prolongator. VT = ventricular tachycardia

Diagnosis of QT Prolongation and Risk Stratification

The estimated prevalence of congenital long QT syndrome is approximately 1 × 10–4 to 2 × 10–4 individuals[1,25] with a predilection for Caucasian subjects and reproductive-age females. On the other hand, incidence of mutation carriers is approximately 2 × 10–4 to 3.3 × 10–4, supporting the notion of incomplete penetrance.[29] The syndrome may be responsible for 3,000–4,000 sudden deaths annually in the US alone.[30]

One might think that QT prolongation diagnosis would be straightforward; however, neither diagnostic criteria, nor even correct measurement of the QT interval, or alternative indices are generally agreed upon and consistently performed, at least in daily clinical practice.

To begin with, QT interval should be measured in certain leads where it was thought to be most prolonged[31] and averaged over several cycles. These leads generally are DII or V5, and should their tracing be difficult to interpret, leads V3 and V4 can be substituted for them. AF represents an even more ambiguous condition, whereupon the longest and shortest measured QT intervals should be averaged.[2] Older approaches stipulated that prominent U waves (thought to represent repolarization of Purkinje fibres or M cells)[32] should be included in the measurement only if merging with the final part of the T wave;[33] however, newer recommendations define QT as the interval from the earliest onset of QRS complex to the intersect of the tangent to the steepest descending part of T wave and the baseline in DII or V5 leads.[34]

Despite historical preference of manual QT interval measurement, manufacturers of electrocardiographic equipment have developed powerful automated algorithms, such as the Marquette™ 12SL™ ECG analytical software (GE Healthcare), partly due to the necessity of cost reduction in studies assessing torsadogenic potential of medications under development, allowing for accurate QT interval assessment (as compared to the gold standard of manual measurement) in the overwhelming majority of cases (divergence in approximately 7 out of 10,000 cases).[35]

Linear regression of the QT on the RR interval, reminiscent of the APD restitution curve, allowing a more thorough and individualised[36] visualisation of ventricular repolarization under differing conditions, has been introduced (although linearity may be an issue).[37,38] More specifically, the ‘individualised corrected QT interval’[39] is defined as the QT interval corresponding to an RR of 1,000 msec, with the regression line acting as the connecting function. This approach may even allow for identification of long QT syndrome-associated mutation carriers with concealed prolongation. Alternatively, the QT/TQ ratio could be plotted against the RR interval to yield a variation of the ECG restitution curve.[40] It assumes values <1 at lower heart rates and >1 at higher rates (despite the adaptation of APD it does not suffice to fully negate the relative QT prolongation). Stress renders the curve both steeper and displaces it to the right, so that there is increased relative QT prolongation at lower rates. Whether this approach could be used to assess long QT patients and estimate their arrhythmogenetic potential remains to be seen.

Measured QT interval should always be corrected (QTc) by the underlying heart rate. The most widely used formulae are that of Bazzet (

, QT in msec, RR in seconds) and Fridericia (

, QT in msec, RR in seconds), although several other approaches have been proposed (i.e. Framingham and Hodges).[41] Evidently, accuracy of those depends on the degree of approximation of the actual APD = f(DI) function, which explains, for instance, the limitation of Bazzet’s formula to rates in the 60–100 range (where the square root approximates the actual relationship). Normal corrected QT values are depicted in Table 3.

Table 3: Normal QTc Values by Age and Gender (Bazzet formula).

| QTc value (msec) | 1–15 years | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | <440 | <430 | <450 |

| Borderline | 441–460 | 431–450 | 451–470 |

| Prolonged | >460 | >450 | >470 |

QTc = corrected QT. Note absence of gender difference until early adolescence. Bazzet formula adapted from Goldenberg, et al., 2006[103]

The 1993 modified Schwarz criteria[42] have been used for long QT syndrome diagnosis; however, recently the European Heart Rhythm Association[43] included the following as criteria for long QT syndrome diagnosis: a Schwarz score ≥3.5; or presence of unequivocal pathogenic mutation; or Bazzet-corrected QT interval >500 msec or QTc 480–499 with presence of unexplained syncope.

Sugrue et al. attempted to address the issue of diagnosing concealed QT prolongation by pursuing a different approach[44] based on alterations of the T wave per se[45] (corresponding to phase 3 of ventricular cell action potential) due to pathogenic mutations. They reported that, in a population of 290 patients without manifest prolongation but carrying an established pathogenic mutation (based on long QT syndrome presence in close relatives), certain features of the T wave could correctly classify those without overt prolongation with an accuracy of 83 %. Interestingly, lead V6 appeared to be the most technically amenable to assessment. These were: reduced upslope of the wave, prolonged peak-to-end time and temporally displaced wave (further apart from peak R).

Provocative manoeuvres, such as transition from supine to erect position, adrenaline infusion and QT measurement during exercise recovery may be used to unmask inappropriate QT interval behaviour (i.e. failure to proportionally shorten),[46] and thus ‘conditional’ long QT syndrome in case of diagnostic dilemmas.[47]

Following a different conceptual framework, vectorcardiography (VCG) may allow for non-invasive assessment of repolarization dispersion. More specifically, proof of concept studies[48] have reported that in healthy individuals VCG indices of repolarization homogeneity, such as normality of T wave loop area and total QRS-T angle are strongly affected by body position and provocative manoeuvres, similar to those used in the unmasking of long QT syndrome.

Finally, a novel approach in congenital long QT syndrome diagnosis and also arrhythmic risk stratification (but theoretically applicable to acquired forms as well) is based on the application of ECG imaging.[49] This technique fuses anatomical data from ECG-gated chest CT with a 256-lead surface ECG (whereupon an electrode-loaded chest plate is used) to produce >500 unipolar epicardial ECGs,[50] reminiscent of invasive electroanatomical mapping, yet having the added feature of assessing repolarization as well. Consequently, regional differences in recovery time (defined as the time to maximum first temporal derivative of voltage at the ascending part of the T wave) and activation-recovery time (a surrogate for action potential duration)[51] can be appreciated. As expected, long QT patients do not exhibit alterations in activation time, yet they do present varying degrees of recovery and activation-recovery time prolongation.[50] Given its unipolar nature, each one of these ‘leads’ does assess the behaviour of all regional myocardial wall layers, including M cells. Thus, when abrupt changes are noted in temporal values of adjacent areas in the reconstructed 3D map, it could suggest an increased propensity to arrhythmogenesis (in the form of a figure of 8 re-entry), and indeed exploratory findings appear to support this notion.[50]

Treatment of Long QT Syndrome

The uncovering of molecular mechanisms responsible for QT prolongation (Tables 1 and 2) has led to a more rationalised approach to its treatment, i.e. pharmacological, device-based and interventional. Recently, consensus has been reached regarding management of congenital long QT syndrome.[47] More specifically, in the case of congenital long QT syndrome type 1 and 2, beta-blockers constitute the recommended initial approach to all patients in the absence of contraindications, such as asthma.[6,52,53] They have been shown to reduce event rates by as much as 81 % and 59 %, respectively,[54] and most of residual events are often due to non-adherence to the regimens.[55] Beta-blockers do not themselves shorten the QT interval, rather, they abrogate the prolonging effects of increased heart rate on it. However, they should be judiciously, if not carefully used in type 3 long QT syndrome, given that this form is most often associated with bradycardia-induced arrhythmias.[56] On the contrary, INa blockers, such as mexiletine or flecainide, have been shown in experimental models to potently reverse QT interval prolongation in type 3 long QT syndrome, consistent with their more pronounced effects on the electrophysiological properties of M cells.[6] Care should be taken so as not to overtreat and elicit a Brugada phenotype (Ito currents remain unaffected while sodium current decreases, mimicking the SCN5A loss of function mutation).[57] Moreover, they have also been found effective in types 1 and 2 of the syndrome (reducing depolarizing currents, thus restoring equilibrium with the affected potassium ones). Finally, the most potent late INa inhibitor, ranolazine, is thought to be of value in all long QT syndrome forms.[6] Evidence regarding potassium current enhancers, such as nicorandil is at present based only on experimental data, and thus these drugs do not constitute an established choice in clinical practice.[5]

On the contrary, and given the role of calcium not only in shaping the action potential but also in determining the form of the restitution curve for a given DI,[10,15] it is not surprising that verapamil has been found beneficial in all three major forms of congenital long QT syndrome, as well as in type 8 of the syndrome (etiological therapy since it is caused by increased L-type calcium channel activation) both at the bench-and bedside.[58,59] Ryanodine receptor inhibitors may prevent calcium-induced calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and thus abrogate afterdepolarizations, removing the triggering stimulus for potential re-entry initiation.[16] More advanced pharmacological therapies involve restoration of protein localisation to the cellular membrane, especially useful in the case of (intracellular) trafficking affecting mutations,[6,16] and both up-and downregulation of gap junction opening, aiming to increase conduction velocity and reduce the transmural gradient of repolarization (the former) and increase refractoriness (the latter). Ultimately, these changes will increase the functional wavelength of the tachycardia, potentially ‘short-circuiting’ the re-entry by creating a discordance between it and the actual anatomical pathway available.

Device therapy in long QT syndrome includes both pacemakers and ICDs. A pacemaker may be used in those with acquired, pause-dependent forms of the syndrome, or in those with type 3 congenital long QT that exhibit similar susceptibility to arrhythmia during bradycardia.[52] Obviously, both pacemakers and isoproterenol infusion (in cases of acute management) are contraindicated in syndromes with tachycardia-induced polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, such as types 1 and 2 of congenital long QT. Defibrillators on the other hand, are clearly indicated in those long QT patients that have survived a cardiac arrest (class I) and should be considered for those remaining symptomatic while on optimal pharmacotherapy (IIa).[43]

Factors generally associated with increased arrhythmogenic potential in long QT syndromes include:[60] presence of deafness (homozygosity/double heterozygosity [see Table 1 for Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome]), recurrent syncope/family history of sudden death, conduction disturbances, QTc >500 msec and T wave alternans (i.e. repolarization is unstable enough to differ on a beat-by-beat basis). Indeed,[53] presence of either QTc >500 msec or prior syncope is associated with a cumulative 5-year rate of aborted or suffered sudden cardiac death of 3 % (thus rendering them appropriate candidates for primary prevention), while in their absence the risk falls down to 0.5 %. According to a 2012 study[61] of 233 long QT patients, defibrillator appropriate therapy may be predicted by age at presentation <20 years, QTc >500 msec, prior cardiac arrest and symptoms while on medications. Although no events occurred in those without any of these factors, 70 % of those with at least one of them experienced an appropriate shocks during a 7-year follow up.[61] Despite any potential future advances in stratification (e.g. though use of ECG imaging as described earlier), currently the decision to implant a device should reasonably lead to defibrillator implantation given its built-in pacing capability.

Cardiac sympathetic denervation is generally reserved for those remaining symptomatic despite use of all indicated, as per syndrome category, therapies,[6] including syncope or multiple appropriate therapies by an implantable defibrillator. It has been shown[62] to be very efficacious (event reduction ~91 %) especially in type 1 and, unexpectedly, type 3 congenital long QT syndrome.

Arrhythmogenic Potential of QT Prolongation

QT prolongation, an umbrella term for both congenital and acquired forms of the syndrome, constitutes the most well-known form of repolarization-related arrhythmogenic disorders. It forms one of the syndromes accounting for the majority of sudden deaths amongst those without structural heart disease (10–20 % of sudden deaths).[63] Although its course used to be thought of as relatively benign, with a 30-year event rate of 4 %,[64] several subpopulations exist with significantly higher risk for arrhythmic events and a consistent correlation exists between QT duration and mortality (hazard ratio 1.35 for total mortality, 1.51 for cardiovascular mortality and 1.44 for sudden cardiac death, with every 50 msec increment conferring a 20 % additional risk for total mortality and a 24 % additional risk for sudden death).[65] A mathematical formula correlating risk of torsade with QT duration has been proposed:[66] Risk = 1.052x, where X =

, QTc being the corrected QT duration in msec. Moreover, in 30–40 % of patients the first manifestation of the syndrome is sudden cardiac death, while morality rates of untreated patients are as high as 50 % at the first decade.[67]

However, QT prolongation is not always evident on the ECG, it may vary in a diurnal fashion (90 ± 20 msec),[68] a large overlap is noted between healthy outliers and the three major congenital QT prolongation syndromes[60] and, ultimately, neither is it necessary nor sufficient for the occurrence of arrhythmia (i.e. events may occur if dispersion is sufficient [≈12 msec/mm in canine heart tissue[4]] regardless of QT duration, 5 % of long QT patients had suffered cardiac arrest with an interval <440 msec[69]). Indeed, there is no identifiable QT prolongation value cutoff[70] associated with polymorphic VT occurrence. Furthermore, the congenital long QT syndromes may be characterised by ‘formes frustes’ (generally when mutations are not in the pore-forming region or involve intracellular trafficking rather than functional defects and lead to a <50 % reduction in function[1]) requiring a second precipitator to manifest the phenotype. This could account for the finding that the dose of a precipitating medication has not been found to correlate with torsade risk.[71]

Approach considerations are even more complicated in the case of young athletes; however, newer US guidelines[72] are considerably more liberal, allowing phenotype-negative individuals to partake in competitive sports provided all secondary QT prolongating factors are meticulously addressed and an external defibrillator is available.[47] Obviously, this excludes activities that are directly associated with arrhythmogenesis, such as swimming in diagnosed type 1 long QT syndrome.

Evidently this raises the issue of whether QT prolongation should be a valid definite diagnosis, especially in conditions without established arrhythmia propensity, or further assays (and which ones) assessing the underlying electrophysiological implications of each condition should be pursued. This stems from the relationship between QT prolongation and torsadogenic potential exposed earlier and illustrated by the Venn diagrams in Figure 1. However, techniques combining imaging and function have started to yield interesting results.[73] More specifically, strain echocardiography has revealed that type 1 and 2 congenital long QT syndrome patients exhibit reduced global longitudinal strain, as well as increased mechanical dispersion.[74] Furthermore, there is increased temporal discrepancy between the duration of mechanical diastole and that of electrical recovery, as evidenced by increased electromechanical time (delta t between Q-Aortic valve closure and QT duration). Increased mechanical dispersion has previously been correlated with increased arrhythmogenicity in the long QT,[75,76] potentially though its link with APD dispersion, inasmuch as prolonged depolarization will delay relaxation (maintaining high intracellular calcium concentrations) of those cells most affected by the disorder. Other techniques, such as MRI tagging, potentially the gold standard in 3D strain assessment may, in this conceptual framework, also prove invaluable in arrhythmic risk stratification of long QT patients.

Conclusion

It appears that repolarization propensity to instability, and thus arrhythmogenesis, sometimes evidenced by prolongation of the QT interval on surface ECG, stems from its inherent non-coordinated and active nature (as opposed to the triggered, coordinated and passive [i.e. depending on electrochemical gradients established during repolarization — nature of depolarization]). The reason behind this apparent design flaw may be explainable by the following fundamental aspect of cardiovascular physiology: contraction is coupled with depolarization, thus coordination, speed and effectiveness of the former is entirely dependent on coordination, speed and effectiveness of the latter, achievable through its triggered and passive nature (ion channels are orders of magnitude faster ion transporters than pumps that, on the other hand can actively modify ionic concentrations). To achieve this, repolarization has to restore electrochemical gradients via active, energy-consuming ion movement and cannot itself be effectively coordinated, inasmuch as there are no gradients that can be harvested for a trigger to activate. Thus, in clinical practice, when evaluating long QT patients, every effort should be made to determine the nature of the syndrome (congenital/acquired) and assess its arrhythmogenic potential, in order to better tailor the treatment approach.

References

- 1.Goldenberg I, Zareba W, Moss AJ. Long QT syndrome. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2008;33:629–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ponte ML, Keller GA, Di Girolamo G. Mechanisms of drug induced QT interval prolongation. Curr Drug Saf. 2010;5:44–53. doi: 10.2174/157488610789869247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop MJ, Vigmond EJ, Plank G. The functional role of electrophysiological heterogeneity in the rabbit ventricle during rapid pacing and arrhythmias. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H1240–52. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00894.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akar FG, Yan GX, Antzelevitch C, Rosenbaum DS. Unique topographical distribution of M cells underlies reentrant mechanism of torsade de pointes in the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2002;105:1247–53. doi: 10.1161/hc1002.105231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dilaveris PE. Molecular predictors of drug-induced prolongation of the QT interval. Curr Med Chem Cardiovasc Hematol Agents. 2005;3:105–18. doi: 10.2174/1568016053544318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel C, Antzelevitch C. Pharmacological approach to the treatment of long and short QT syndromes. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;118:138–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zygmunt AC, Eddlestone GT, Thomas GP et al. Larger late sodium conductance in M cells contributes to electrical heterogeneity in canine ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H689–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.2.H689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antzelevitch C. Arrhythmogenic mechanisms of QT prolonging drugs: is QT prolongation really the problem? J Electrocardiol. 2004;37(Suppl:15–24) doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J, Naiki N, Ding WG et al. A molecular mechanism for adrenergic-induced long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:819–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qu Z, Weiss JN, Garfinkel A. Cardiac electrical restitution properties and stability of reentrant spiral waves: a simulation study. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H269–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.1.H269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franz MR. The electrical restitution curve revisited: steep or flat slope—which is better? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14(Suppl 10):S140–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1540.8167.90303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koller ML, Riccio ML, Gilmour RF., Jr Dynamic restitution of action potential duration during electrical alternans and ventricular fibrillation. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H1635–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.5.H1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss JN, Garfinkel A, Karagueuzian HS et al. Chaos and the transition to ventricular fibrillation: a new approach to antiarrhythmic drug evaluation. Circulation. 1999;99:2819–26. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.21.2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koller ML, Maier SK, Gelzer AR et al. Altered dynamics of action potential restitution and alternans in humans with structural heart disease. Circulation. 2005;112:1542–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.502831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldhaber JI, Xie LH, Duong T et al. Action potential duration restitution and alternans in rabbit ventricular myocytes: the key role of intracellular calcium cycling. Circ Res. 2005;96:459–66. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000156891.66893.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tse G, Chan YW, Keung W, Yan BP. Electrophysiological mechanisms of long and short QT syndromes. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2017;14:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makkar RR, Fromm BS, Steinman RT et al. Female gender as a risk factor for torsades de pointes associated with cardiovascular drugs. JAMA. 1993;270:2590–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510210076031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coker SJ. Drugs for men and women - how important is gender as a risk factor for TdP? Pharmacol Ther. 2008;119:186–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drici MD, Knollmann BC, Wang WX, Woosley RL. Cardiac actions of erythromycin: influence of female sex. JAMA. 1998;280:1774–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.20.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bai CX, Kurokawa J, Tamagawa M et al. Nontranscriptional regulation of cardiac repolarization currents by testosterone. Circulation. 2005;112:1701–10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.523217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanabe S, Hata T, Hiraoka M. Effects of estrogen on action potential and membrane currents in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H826–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.2.H826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bidoggia H, Maciel JP, Capalozza N et al. Sex differences on the electrocardiographic pattern of cardiac repolarization: possible role of testosterone. Am Heart J. 2000;140:678–83. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.109918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdelgadir SE, Resko JA, Ojeda SR et al. Androgens regulate aromatase cytochrome p450 messenger ribonucleic acid in rat brain. Endocrinology. 1994;135:395–401. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.1.8013375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shryock JC, Song Y, Wu L et al. A mechanistic approach to assess the proarrhythmic risk of QT-prolonging drugs in preclinical pharmacologic studies. J Electrocardiol. 2004;37(Suppl:34–9) doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kao LW, Furbee RB. Drug-induced q-T prolongation. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89:1125–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asano Y, Davidenko JM, Baxter WT et al. Optical mapping of drug-induced polymorphic arrhythmias and torsade de pointes in the isolated rabbit heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:831–42. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(96)00588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Surawicz B. Electrophysiologic substrate of torsade de pointes: dispersion of repolarization or early afterdepolarizations? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14:172–84. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Surawicz B. Torsades de pointes: unanswered questions. J Nippon Med Sch. 2002;69:218–23. doi: 10.1272/jnms.69.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ackerman MJ. The long QT syndrome: ion channel diseases of the heart. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:250–69. doi: 10.4065/73.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Sherif N, Turitto G. Zipes DP, Jalife J. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2004. Torsade de pointes. In: Cardiac Electrophysiology: From Cell to Bedside. 4th ed. pp. 687–99. (eds) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sadanaga T, Sadanaga F, Yao H, Fujishima M. An evaluation of ECG leads used to assess QT prolongation. Cardiology. 2006;105:149–54. doi: 10.1159/000091227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pérez Riera AR, Ferreira C, Filho CF et al. The enigmatic sixth wave of the electrocardiogram: the U wave. Cardiol J. 2008;15:408–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta A, Lawrence AT, Krishnan K et al. Current concepts in the mechanisms and management of drug-induced QT prolongation and torsade de pointes. Am Heart J. 2007;153:891–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rezus C, Moga VD, Ouatu A, Floria M. QT interval variations and mortality risk: is there any relationship? Anatol J Cardiol. 2015;15:255–8. doi: 10.5152/akd.2015.5875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hnatkova K, Gang Y, Batchvarov VN, Malik M. Precision of QT interval measurement by advanced electrocardiographic equipment. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:1277–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Batchvarov VN, Ghuran A, Smetana P et al. QT-RR relationship in healthy subjects exhibits substantial intersubject variability and high intrasubject stability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H2356–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00860.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fossa AA, Zhou M. Assessing QT prolongation and electrocardiography restitution using a beat-to-beat method. Cardiology J. 2010;17:230–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rautaharju PM, Surawicz B, Gettes LS et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part iv: the ST segment, T and U waves, and the QT interval: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Alectrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:982–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robyns T, Willems R, Vandenberk B et al. Individualized corrected QT interval is superior to QT interval corrected using the Bazett formula in predicting mutation carriage in families with long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:376–82. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fossa AA. Beat-to-beat ECG restitution: a review and proposal for a new biomarker to assess cardiac stress and ventricular tachyarrhythmia vulnerability. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2017;22:e12460. doi: 10.1111/anec.12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo S, Michler K, Johnston P, Macfarlane PW. A comparison of commonly used QT correction formulae: the effect of heart rate on the QTc of normal ECGs. J Electrocardiol. 2004;37(Suppl:81–90) doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwartz PJ, Moss AJ, Vincent GM, Crampton RS. Diagnostic criteria for the long QT syndrome. An update. Circulation. 1993;88:782–4. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.88.2.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M et al. Executive summary: HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes. Europace. 2013;15:1389–406. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugrue A, Noseworthy PA, Kremen V et al. Identification of concealed and manifest long QT syndrome using a novel T wave analysis program. Circ. Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9:e003830. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Benhorin J et al. ECG T-wave patterns in genetically distinct forms of the hereditary long QT syndrome. Circulation. 1995;92:2929–34. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.92.10.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waddell-Smith KE, Skinner JR. Update on the diagnosis and management of familial long QT syndrome. Heart Lung Circ. 2016;25:769–76. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2016.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M et al. HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:1932–63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Batchvarov V, Dilaveris P, Färbom P et al. New descriptors of homogeneity of the propagation of ventricular repolarization. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23:1968–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2000.tb07064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rudy Y. Noninvasive ECG imaging (ECGI): mapping the arrhythmic substrate of the human heart. Int J Cardiol. 2017;237:13–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.02.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vijayakumar R, Silva JN, Desouza KA et al. Electrophysiologic substrate in congenital long QT syndrome: noninvasive mapping with electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI). Circulation. 2014;130:1936–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coronel R, de Bakker JM, Wilms-Schopman FJ et al. Monophasic action potentials and activation recovery intervals as measures of ventricular action potential duration: experimental evidence to resolve some controversies. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1043–50. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gomez AT, Prutkin JM, Rao AL. Evaluation and management of athletes with long QT syndrome. Sports Health. 2016;8:527–35. doi: 10.1177/1941738116660294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ et al. Effectiveness and limitations of beta-blocker therapy in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2000;101:616–23. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.6.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Spazzolini C et al. Genotypephenotype correlation in the long-QT syndrome: genespecific triggers for life-threatening arrhythmias. Circulation. 2001;103:89–95. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schwartz PJ, Crotti L. Zipes DP, Jalife J. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014. Long and short QT syndromes. In: Cardiac Electrophysiology: From Cell to Bedside. 6th ed. pp. 935–46. (eds) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C. Differential effects of betaadrenergic agonists and antagonists in LQT1, LQT2 and LQT3 models of the long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:778–86. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00582-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Priori SG, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ et al. The elusive link between LQT3 and Brugada syndrome: the role of flecainide challenge. Circulation. 2000;102:945–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.9.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aiba T, Shimizu W, Inagaki M et al. Cellular and ionic mechanism for drug-induced long QT syndrome and effectiveness of verapamil. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:300–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shimizu W, Ohe T, Kurita T et al. Effects of verapamil and propranolol on early afterdepolarizations and ventricular arrhythmias induced by epinephrine in congenital long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1299–309. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Medeiros-Domingo A, Iturralde-Torres P, Ackerman MJ. [Clinical and genetic characteristics of long QT syndrome]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2007;60:739–52. doi: 10.1157/13108280. [in Spanish] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwartz PJ, Spazzolini C, Priori SG et al. Who are the long-QT syndrome patients who receive an implantable cardioverterdefibrillator and what happens to them?: data from the European long-QT syndrome implantable cardioverterdefibrillator (LQTS ICD) registry. Circulation. 2010;122:1272–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.950147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Cerrone M et al. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation in the management of high-risk patients affected by the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2004;109:1826–33. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000125523.14403.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brugada P, Brugada R, Brugada J, Geelen P. Use of the prophylactic implantable cardioverter defibrillator for patients with normal hearts. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:98D–100D. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)01009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zareba W, Moss AJ, Schwartz PJ et al. Influence of the genotype on the clinical course of the long-QT syndrome. International long-QT syndrome registry research group. New Engl J Med. 1998;339:960–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810013391404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Y, Post WS, Blasco-Colmenares E et al. Electrocardiographic QT interval and mortality: a metaanalysis. Epidemiology. 2011;22:660–70. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318225768b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Webster R, Leishman D, Walker D. Towards a drug concentration effect relationship for QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2002;5:116–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schwartz PJ. Idiopathic long QT syndrome: progress and questions. Am Heart J. 1985;109:399–411. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90626-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Molnar J, Zhang F, Weiss J et al. Diurnal pattern of QTc interval: how long is prolonged? Possible relation to circadian triggers of cardiovascular events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:76–83. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00426-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moskovitz JB, Hayes BD, Martinez JP et al. Electrocardiographic implications of the prolonged QT interval. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:866–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Malik M, Camm AJ. Evaluation of drug-induced QT interval prolongation: implications for drug approval and labelling. Drug Saf. 2001;24:323–51. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Houltz B, Darpö B, Edvardsson N et al. Electrocardiographic and clinical predictors of torsades de pointes induced by almokalant infusion in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation or flutter: a prospective study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21:1044–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1998.tb00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maron BJ, Zipes DP, Kovacs RJ. Eligibility and disqualification recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities: preamble, principles, and general considerations: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2343–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jahangir A, Jain R. Strain echocardiography and LQTS subtypes: mechanical alterations in an electrical disorder. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:511–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leren IS, Hasselberg NE, Saberniak J et al. Cardiac mechanical alterations and genotype specific differences in subjects with long QT syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:501–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haugaa KH, Amlie JP, Berge KE et al. Transmural differences in myocardial contraction in long-QT syndrome: mechanical consequences of ion channel dysfunction. Circulation. 2010;122:1355–63. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.960377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haugaa KH, Edvardsen T, Leren TP et al. Left ventricular mechanical dispersion by tissue Doppler imaging: a novel approach for identifying high-risk individuals with long QT syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:330–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Antzelevitch C, Shimizu W, Yan GX et al. The M cell: its contribution to the ECG and to normal and abnormal electrical function of the heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10:1124–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C. Sodium channel block with mexiletine is effective in reducing dispersion of repolarization and preventing torsade des pointes in LQT2 and LQT3 models of the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 1997;96:2038–47. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.96.6.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bennett V, Baines AJ. Spectrin and ankyrin-based pathways: metazoan inventions for integrating cells into tissues. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1353–92. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Sharpe LM et al. Ca(v)1.2 calcium channel dysfunction causes a multisystem disorder including arrhythmia and autism. Cell. 2004;119:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hedley PL, Jorgensen P, Schlamowitz S et al. The genetic basis of Brugada syndrome: a mutation update. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1256–66. doi: 10.1002/humu.21106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scherer PE, Okamoto T, Chun M et al. Identification, sequence, and expression of caveolin-2 defines a caveolin gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:131–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tang Z, Scherer PE, Okamoto T et al. Molecular cloning of caveolin-3, a novel member of the caveolin gene family expressed predominantly in muscle. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2255–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.4.2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Williams TM, Lisanti MP. The caveolin proteins. Genome Biol. 2004;5:214. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marx SO, Kurokawa J, Reiken S et al. Requirement of a macromolecular signaling complex for beta adrenergic receptor modulation of the KCNQ1-KCNE1 potassium channel. Science. 2002;295:496–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1066843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gee SH, Madhavan R, Levinson SR et al. Interaction of muscle and brain sodium channels with multiple members of the syntrophin family of dystrophin-associated proteins. J Neurosci. 1998;18:128–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00128.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P. Pharmacological and device approach to therapy of inherited cardiac diseases associated with cardiac arrhythmias and sudden death. J Electrocardiol. 2000;33(Suppl:41–7) doi: 10.1054/jelc.2000.20322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C, Vos MA. Assessing predictors of drug-induced torsade de pointes. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:619–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fenichel RR, Malik M, Antzelevitch C et al. Drug-induced torsades de pointes and implications for drug development. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15:475–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Woosley RL, Black K, Heise CW, Romero K. CredibleMeds.org: What does it offer? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2017 Aug 1. pii: S1050-1738(17)30114-7. [Epub ahead of print]. Website accessed in 15/8/2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 91.Lasser KE, Allen PD, Woolhandler SJ et al. Timing of new black box warnings and withdrawals for prescription medications. JAMA. 2002;287:2215–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fazio G, Vernuccio F, Grutta G, Re GL. Drugs to be avoided in patients with long QT syndrome: focus on the anaesthesiological management. World J Cardiol. 2013;5:87–93. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v5.i4.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cuni R, Parrini I, Asteggiano R, Conte MR. Targeted cancer therapies and QT interval prolongation: unveiling the mechanisms underlying arrhythmic complications and the need for risk stratification strategies. Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37:121–34. doi: 10.1007/s40261-016-0460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Al-Khatib SM, LaPointe NM, Kramer JM, Califf RM. What clinicians should know about the QT interval. JAMA. 2003;289:2120–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sordillo PP, Sordillo DC, Helson L. Review: the prolonged QT interval: role of pro-inflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species and the ceramide and sphingosine-1 phosphate pathways. In Vivo. 2015;29:619–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Omran J, Firwana B, Koerber S et al. Effect of obesity and weight loss on ventricular repolarization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17:520–30. doi: 10.1111/obr.12390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ferrannini E, Galvan AQ, Gastaldelli A et al. Insulin: new roles for an ancient hormone. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999;29:842–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li W, Bai Y, Sun K et al. Patients with metabolic syndrome have prolonged corrected QT interval (QTc). Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:E93–9. doi: 10.1002/clc.20416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Grandi E, Bers DM. Zipes DP, Jalife J. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014. Models of the ventricular action potential in health and disease. In: Cardiac Electrophysiology: From Cell to Bedside. 6th ed. pp. 319–30. (eds) [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dillmann WH. Cellular action of thyroid hormone on the heart. Thyroid. 2002;12:447–52. doi: 10.1089/105072502760143809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Klein I, Ojamaa K. Thyroid hormone and the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:501–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vandael E, Vandenberk B, Vandenberghe J et al. Risk factors for QTc-prolongation: systematic review of the evidence. Int J clin Pharm. 2017;39:16–25. doi: 10.1007/s11096-016-0414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, Zareba W. QT interval: how to measure it and what is “normal”. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:333–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Koeppen BM, Stanton BA. Philadelphia: PA Mosby Elsevier; 2010. Berne & Levy Physiology. 6th ed. (eds) [Google Scholar]