While the majority of myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia (MDS/AML) cases are sporadic, rare familial predisposition syndromes have been delineated and now represent a separate disease entity in the revised World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms [1]. Germline mutations in ~14 disease genes have been uncovered thus far, with GATA2 representing one of the key transcriptional regulators commonly mutated in inherited MDS/AML [2]. Increasing evidence suggests that aberrations in GATA2 impair its transcription and promoter activation, leading to a loss-of-function, supporting a mechanism of GATA2 haploinsufficiency [3–5]. Reduced penetrance, the observation that family members carry an identical germline mutation yet display variable clinical manifestations, is common and poses a clinical challenge in the diagnosis and management of familial leukemia's, particularly when identifying “silent” mutation carriers for genetic screening and exclusion as potential stem cell transplant donors [6, 7]. Indeed, we have noted that reduced penetrance is a feature among certain GATA2-mutated MDS/AML families [8], especially those harboring missense germline mutations such as c.1061C>T (p.Thr354Met) (Table S1) although the precise molecular explanation of such occurrence has not been investigated.

Analysis of five MDS/AML families harboring p.Thr354Met GATA2 mutations displayed significant intra- and interfamilial variations in disease latency, phenotype, and penetrance (Figure S1). These observations suggest that individuals require additional co-operating events for the development of overt malignancy within the context of a shared germline mutation. To investigate this hypothesis further, we examined an extensive five-generation pedigree [9] (Fig. 1a) where two first-degree cousins (IV.1 and IV.6) developed high-risk MDS/AML with monosomy 7, while a third cousin (IV.10) presented with recurrent minor infections and significant monocytopenia [0.1 × 109/L] and neutropenia [0.8 × 109/L] in year (yr.) 1–3 which subsequently stabilized (monocyte count, neutrophils [>1 × 109/L]) 3 years after presentation (Fig. 1b). This contrasted with the parental generation (III.1, III.5, and III.7) where mutation carriers remain symptom-free with no evidence of hematopoietic abnormality over 60 years of age.

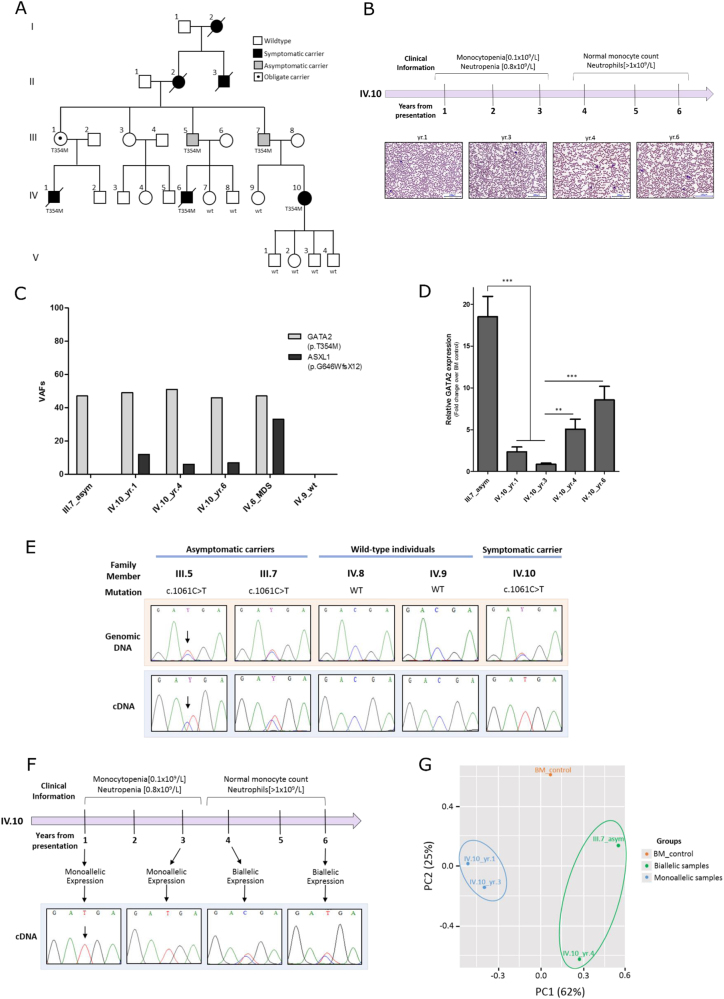

Fig. 1.

Investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying the reduced penetrance of germline p.Thr354Met mutations observed in a GATA2-mutated MDS/AML family. a Genogram of the GATA2-mutated pedigree. Squares denote males and circles denote females. This five-generation MDS/AML family presented to Barts Health hospital in London with identical germline GATA2 mutations (p.Thr354Met; c.1061C>T) and variable clinical manifestations. Two first-degree cousins (IV.1 and IV.6) presented at 23 and 18 years of age, respectively, with high-grade MDS transforming to AML and monosomy 7. Both cousins died post allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) due to transplant-related complications (IV.1 from graft vs. host disease (GvHD) and IV.6 from relapsed MDS/AML). Ten years later, their first cousin (IV.10) developed symptoms at 31 years, including recurrent minor infections and significant leukopenia (monocytopenia [0.1 × 109/L] and neutropenia [0.8 × 109/L]) with mild macrocytosis and normal hemoglobin and platelet counts. She remains under close surveillance where her blood counts are routinely monitored. All four of her children have inherited her WT GATA2 allele. Similarly, members (IV.7, IV.8, and IV.9) were screened for the mutation and all have a WT GATA2 configuration. The paternal grandmother (II.2) of IV.10 as well as her paternal great-uncle (II.3) and great-grandmother (I.2) all were reported to have died of AML (ages of disease onset were 53, 24, and 53-years old, respectively). Not only did GATA2 mutations correlate with early age of disease onset in the fourth generation (IV.1/23 yr., IV.6/18 yr., and IV.10/31 yr.), but the parental third-generation carriers (III.1, III.5, and III.7) remain hematologically normal and symptom-free into their mid–late 60s. No material was available from other family members. b A clinical timeline of IV.10 showing the change in clinical parameters over the course of disease presentation. Photographs of peripheral blood smears from IV.10 (yr. 1, 3, 4, and 6) stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa staining. Magnification: ×20. c Secondary ASXL1 mutations: variant allele frequencies of GATA2 germline mutation and ASXL1 acquired mutation. Samples from three individuals were sequenced: one asymptomatic parent (III.7), one deceased MDS/AML cousin (IV.6), and across three time-points (yr. 1, 4, and 6) from the symptomatic patient (IV.10) reflecting disease evolution. d GATA2 global expression measured by qRT-PCR of bone marrow samples and normalized to healthy bone marrow control: downregulation in IV.10_yr.1 compared with III.7 and downregulation in IV.10_yr.1–3 GATA2 expression compared with IV.10_yr.4–6. The average of five independent experiments is shown. Statistical significance was determined at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 using a t-test with Bonferroni correction. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). e GATA2 monoallelic expression of the mutant allele in symptomatic (IV.10) vs. asymptomatic carriers (III.5 and III.7), as measured by cDNA sequencing of bone marrow samples. f Correlation of monoallelic GATA2 expression with disease symptoms across the time-points studied in IV.10 with reactivation of the WT allele “C” expression noted 3 years after presentation, concurrent with improvements in hematological parameters. g RNA-seq analysis: principal component analysis (PCA) plot showing a good separation between GATA2 biallelic (green) and monoallelic (blue) groups based on all transcriptomes

We therefore started with targeted deep sequencing of 33 genes frequently mutated in MDS/AML to define the landscape of secondary genetic mutations across mutation carriers. Notably, while no acquired mutations were detected in asymptomatic family members, all affected cousins analyzed shared an identical somatic ASXL1 mutation (p.Gly646TrpfsTer12) (Fig. 1c). The variant allele frequency (VAF), however, was lower (12%) in IV.10 and remained stable (range 12–6%) over a 6-year monitoring period. While the co-occurrence of ASXL1 and GATA2 mutations has been proposed as one mechanism for driving the onset and severity of disease symptoms [9–11], the low VAF of ASXL1 mutation and stable improvement in hematopoiesis at IV.10 later follow-up suggested that a combination of GATA2–ASXL1 mutation alone is insufficient to promote clonal expansion and leukemic transformation, as this secondary somatic hit may not represent disease progression or identify when treatment is indicated. Intriguingly, apart from the ASXL1 mutation, no other acquired mutations were detected in the 33-myeloid genes assessed in the affected individuals. Moreover, on the basis of our observations and in agreement with previous studies [12, 13], it seems that monosomy 7 in IV.1 and IV.6 is acquired following acquisition of ASXL1 mutations, hence contributing to the malignancy but not initiating symptoms.

We next considered whether disease symptoms are modulated by endogenous levels of GATA2. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) of bone marrow material demonstrated total GATA2 expression to be significantly lower in the symptomatic (IV.10-yr.1) compared with an asymptomatic carrier (III.7) (Fig. 1d). Significantly, Sanger sequencing of the cDNA template revealed striking allele-specific expression (ASE), favoring the mutant (T) allele with the absence of the wild-type (WT) (C) allele expression in the symptomatic patient (IV.10), contrasting with biallelic expression in asymptomatic members (III.5 and III.7) (Fig. 1e). This observation was validated by cDNA cloning of III.7 and IV.10 bone marrow samples and subsequent Sanger sequencing of individual clones (Figure S2). As this suggested that an allelic imbalance in WT:mutant GATA2 expression ratio may account for the variable disease penetrance in this pedigree, we assessed GATA2 expression in IV.10 over a 6-year disease period at four time-points (yr. 1, 3, 4, and 6), demonstrating increased GATA2 expression at later time-points (yr. 4 and 6) (Fig. 1d) coinciding with reactivation of the WT (C) allele expression (Fig. 1f) and an improvement in hematological parameters, in the absence of any clinical intervention (Fig. 1b).

To test whether monoallelic GATA2 expression has an impact on the transcriptome driving the onset of disease symptoms, we performed RNA-seq with a view of examining downstream biological features distinctive of GATA2 monoallelic (IV.10-yr.1 and 3) vs. biallelic (IV.10-yr.4 and III.7) groups. Unsupervised analysis revealed a clear separation between GATA2 monoallelic and biallelic samples (Fig. 1g, S3 and Table S2). It was noteworthy that certain canonical pathways and gene sets related to tumorigenesis (e.g., DNA replication and cell cycle) were enriched in GATA2 monoallelic vs. biallelic groups (Figure S4), potentially reflecting the clinical and phenotypic switch between these two groups. We also noted a significant overexpression of genes with GATA2 cofactor PU.1 motifs in their regulatory regions (p value NES = 2.06) in GATA2 biallelic vs. monoallelic samples, in support of a recent finding [14] that p.Thr354Met mutants bind and interact with PU.1 more tightly than WT, thus leading to sequestration of PU.1 from its normal cellular functions. Consequently, the transcriptional activation triggered by PU.1 will be diminished in our GATA2 monoallelic samples.

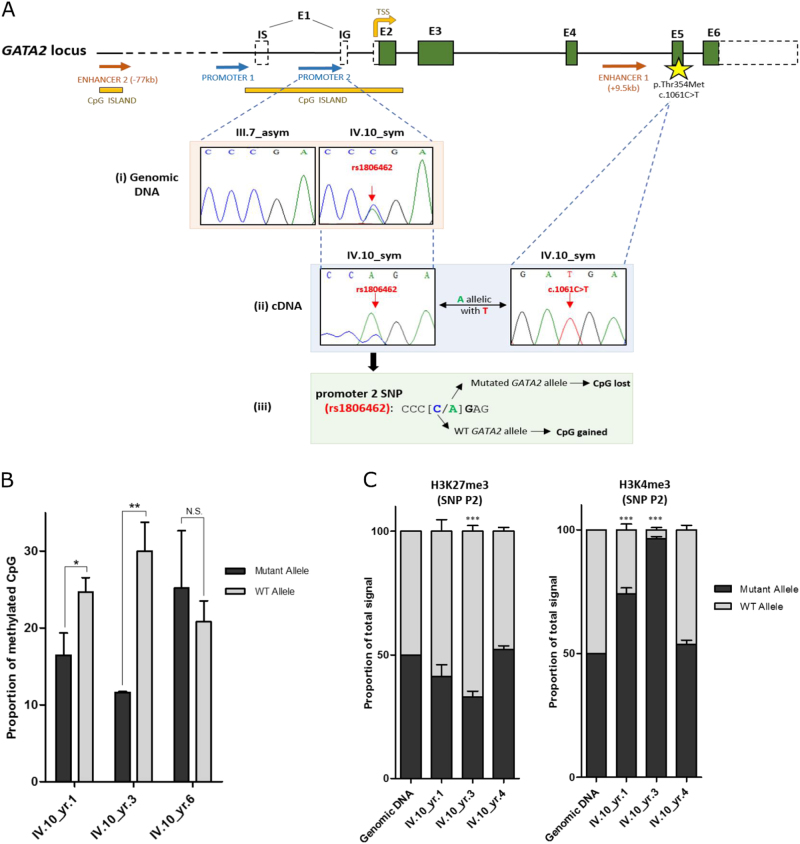

The differences observed in these gene-expression profiles prompted us to explore the molecular mechanisms underlying monoallelic GATA2 expression. We hypothesized that these allele-specific changes in GATA2 expression are driven by transient epigenetic mechanisms that include changes in DNA methylation and chromatin mark deposition. A CpG single-nucleotide polymorphism (CpG-SNP) (rs1806462) [C/A] located within the promoter and 5′UTR of GATA2 overlapping a CpG island offered a marker to distinguish between mutant and WT alleles where this SNP creates/abolishes a CpG dinucleotide within the GATA2 promoter region (Fig. 2a). More specifically, cDNA sequencing of 5′UTR allowed us to define haplotypes, where the promoter SNP allele (A) resides on the germline mutant GATA2 allele (T) (Fig. 2a(ii)). Apart from IV.10, no other family members and only 2/12 individuals from pedigrees presented in Figure S1 were heterozygous for this SNP (one of whom is an asymptomatic carrier). Therefore, we do not infer that this haplotype would contribute to the progression of symptoms. Instead, we used this SNP to determine whether allele-specific differences in DNA methylation could explain the silencing of WT GATA2 allele expression observed in earlier time-points of IV.10. As illustrated in Fig. 2b and S5, bisulfite sequencing of a 200-bp region encompassing rs1806462 demonstrated a significant increase in promoter methylation in the WT allele of IV.10 in yr. 1 and yr. 3 following diagnosis, in contrast with the absence of allele-specific differences in methylation at a later time-point.

Fig. 2.

Elucidating the molecular mechanisms driving allele-specific changes in GATA2 expression. a(i) A noncoding SNP (rs1806462 [C/A]) located within the second GATA2 promoter region overlapping a CpG island was detected in the symptomatic (IV.10) but not in asymptomatic members (III.7). a(ii) Given the location of promoter 2 SNP within the 5’UTR, a haplotype between the SNP allele “A” and the germline mutant allele “T” was established, providing a means of distinguishing between mutant and WT alleles in subsequent experiments. a(iii) This promoter SNP [C/A] removes a CpG methylation site in the mutant allele “A” and generates a CpG methylation site in the WT allele “C”. b The proportion of methylated CpGs between mutant and WT alleles across the three time-points of IV.10. WT allele is significantly more methylated than the mutant allele in monoallelic samples (yr. 1 and yr. 3), whereas no significant allele-specific differences in methylation were observed in a biallelic-expressing sample (yr. 6). The average of three independent experiments is shown. c Quantification of mutant and WT allele ChIP sequence peak heights across the time-points of IV.10 based on Sanger sequencing. H3K4me3 activation mark favoring the mutant allele was enriched in monoallelic samples (yr. 1 and yr. 3) compared with the biallelic sample (yr. 4). The average of three independent experiments is shown. Statistical significance was determined at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 using a t-test with Bonferroni correction. NS corresponds to nonsignificant comparisons. Error bars represent SEM

We next sought to establish whether these allele-specific changes in GATA2 methylation and expression are accompanied by changes in chromatin structure at the promoter. H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 define poised or closed chromatin, respectively, rendering them more or less accessible for transcription factors, thereby regulating gene expression [15]. The deposition of these bivalent marks was assessed in IV.10 by allele-specific chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) followed by Sanger sequencing within GATA2 promoter region encompassing the SNP rs1806462 [C/A]. While there were no apparent allele-specific differences in H3K27me3 deposition across the different time-points of IV.10, an enrichment in the deposition of H3K4me3 on the promoter of the mutant allele (A) relative to the WT allele (C) was noted in IV.10 monoallelic samples (yr. 1 and 3) (Fig. 2c, S6 and S7). In contrast, and consistent with the pattern observed with DNA methylation, there was no demonstrable difference in H3K4me3 deposition in the IV.10 biallelic sample (yr. 4), coinciding with reactivation of the WT allele expression and an overall improvement in clinical parameters. We believe that these observations are in keeping with the notion that H3K4me3 occupancy inhibits de novo DNA methylation [16] which was borne out by subsequent bisulfite sequencing of H3K4me3-enriched DNA from our ChIP experiments, demonstrating that DNA methylation and H3K4me3 deposition are mutually exclusive in our IV.10 samples (Figure S8).

Collectively, our findings provide a step forward in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying reduced penetrance in GATA2-mutated MDS/AML pedigrees, which may be governed by the acquisition of additional co-operating mutations (e.g., ASXL1) combined with dynamic epigenetic reprogramming and subsequent allele-specific expression of GATA2 mutant allele, adding another level of complexity to the (epi)genetic basis of familial MDS/AML.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the family investigated in this study whose members have kindly donated samples for research. We also thank all the clinicians who have looked after this family over the years. This study was supported by the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Higher Education through a doctoral scholarship awarded to A.F.A.S. and a Bloodwise Programme grant (14032) awarded to J.F., T.V., and I.D.

Author contributions

J.F., A.F.A.S., and A.R.-M. designed the study; A.F.A.S. and A.R.-M. performed the experiments; A.F.A.S., A.R.-M., K.T., and J.F. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; K.T., H.S., C.H., T.V., I.D., M.S., and J.C. collated familial clinical information; S.I. provided patient material from tissue bank; S.B., N.L., and D.M. performed targeted deep sequencing; J.W. and A.N. carried out RNA-seq analysis; J.A.H. provided technical ChIP expertise; E.J.K., M.W.W., and C.M.N. provided familial samples; T.B. provided patient blood films; and C.B., A.E., S.R.C., H.T., T.V., and I.D. assisted with data analysis and contributed to the study with fruitful discussions. All authors read, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Ahad F. Al Seraihi, Phone: +44 (0)20 7882 8780, Email: a.f.h.alseraihi@qmul.ac.uk

Jude Fitzgibbon, Phone: +44 (0)20 7882 3814, Email: j.fitzgibbon@qmul.ac.uk.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41375-018-0134-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nickels EM, Soodalter J, Churpek JE, Godley LA. Recognizing familial myeloid leukemia in adults. Ther Adv Hematol. 2013;4:254–69. doi: 10.1177/2040620713487399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celton M, Forest A, Gosse G, Lemieux S, Hebert J, Sauvageau G, et al. Epigenetic regulation of GATA2 and its impact on normal karyotype acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2014;28:1617–26. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortes-Lavaud X, Landecho MF, Maicas M, Urquiza L, Merino J, Moreno-Miralles I, et al. GATA2 germline mutations impair GATA2 transcription, causing haploinsufficiency: functional analysis of the p.Arg396Gln mutation. J Immunol. 2015;194:2190–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu AP, Johnson KD, Falcone EL, Sanalkumar R, Sanchez L, Hickstein DD, et al. GATA2 haploinsufficiency caused by mutations in a conserved intronic element leads to MonoMAC syndrome. Blood. 2013;121:3830–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-452763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.University of Chicago Hematopoietic Malignancies Cancer Risk T. How I diagnose and manage individuals at risk for inherited myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2016;128:1800–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-670240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper DN, Krawczak M, Polychronakos C, Tyler-Smith C, Kehrer-Sawatzki H. Where genotype is not predictive of phenotype: towards an understanding of the molecular basis of reduced penetrance in human inherited disease. Hum Genet. 2013;132:1077–130. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1331-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hahn CN, Chong CE, Carmichael CL, Wilkins EJ, Brautigan PJ, Li XC, et al. Heritable GATA2 mutations associated with familial myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1012–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodor C, Renneville A, Smith M, Charazac A, Iqbal S, Etancelin P, et al. Germ-line GATA2 p.THR354MET mutation in familial myelodysplastic syndrome with acquired monosomy 7 and ASXL1 mutation demonstrating rapid onset and poor survival. Haematologica. 2012;97:890–4. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.054361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boultwood J, Perry J, Pellagatti A, Fernandez-Mercado M, Fernandez-Santamaria C, Calasanz MJ, et al. Frequent mutation of the polycomb-associated gene ASXL1 in the myelodysplastic syndromes and in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:1062–5. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West RR, Hsu AP, Holland SM, Cuellar-Rodriguez J, Hickstein DD. Acquired ASXL1 mutations are common in patients with inherited GATA2 mutations and correlate with myeloid transformation. Haematologica. 2014;99:276–81. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.090217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Muramatsu H, Okuno Y, Sakaguchi H, Yoshida K, Kawashima N, et al. GATA2 and secondary mutations in familial myelodysplastic syndromes and pediatric myeloid malignancies. Haematologica. 2015;100:e398–401. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.127092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pastor V, Hirabayashi S, Karow A, Wehrle J, Kozyra EJ, Nienhold R, et al. Mutational landscape in children with myelodysplastic syndromes is distinct from adults: specific somatic drivers and novel germline variants. Leukemia. 2017;31:759–62. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong CE, Venugopal P, Stokes PH, Lee YK, Brautigan PJ, Yeung DTO, et al. Differential effects on gene transcription and hematopoietic differentiation correlate with GATA2 mutant disease phenotypes. Leukemia. 2017;32:194–202. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawson MA, Kouzarides T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell. 2012;150:12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rose NR, Klose RJ. Understanding the relationship between DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:1362–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.