Abstract

Objective

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine disorder affecting approximately one in seven women who experience androgen excess, menstrual cycle irregularities, frequent anovulation and a tendency for central obesity and insulin resistance. Chronic subclinical inflammation is now recognised as being common in the context of PCOS, which led to the postulation that PCOS may fundamentally be an inflammatory process. This study aimed to: (1) evaluate serum C reactive protein (CRP)/albumin ratio as a potential predictive biomarker for PCOS; (2) compare the relationship between CRP/albumin and PCOS to variables classically associated with the syndrome.

Design

Case–control study.

Setting

Adult obstetrics/gynaecology, endocrinology and outpatient clinics; university hospital in Bahrain.

Participants

200 premenopausal women with a diagnosis of PCOS, and 119 ethnically matched eumenorrheic premenopausal women.

Main outcome measures

CRP/albumin ratio, anthropometric measures, insulin resistance, androgen excess.

Results

Independent of body mass index (BMI), receiver operating characteristic curve for CRP/albumin ratio as a selective biomarker for PCOS was 0.865 (95% CI 0.824 to 0.905), which was more sensitive than CRP alone. Binary regression analysis showed that CRP/albumin ratio outperformed classical correlates, Free Androgen Index and insulin resistance, in predicting PCOS for every BMI category.

Conclusion

CRP/albumin ratio, a marker for inflammation related to metabolic dysfunction, was found to have a stronger association with PCOS than either androgen excess or insulin resistance. Inflammation is known to be influenced by adiposity, but relative to controls, women with PCOS have higher levels of CRP/albumin irrespective of BMI. These findings support the view that inflammation plays a central role in the pathophysiology of PCOS.

Keywords: polycystic ovary syndrome, inflammation, c-reactive protein, albumin, pathophysiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This analysis addressed previous limitations of studies, namely small sample sizes, heterogeneous populations and confounding factors (such as body mass index), that have attempted to show polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is an inflammatory process.

The relationship between inflammation and PCOS was assessed using C reactive protein/albumin ratio, which may be a better marker for inflammation in the context of metabolic dysfunction.

Study used waist circumference as a substitute for visceral adiposity; gold standard is CT or MRI.

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common reproductive disorder, affecting 5%–15% of premenopausal women worldwide,1 2 and the prevalence of PCOS appears to be increasing.1 This rise may partly be attributed to improved diagnosis as well as to an increase in environmental factors that predispose to the development of this complex metabolic condition. PCOS is characterised by androgen excess, menstrual irregularities, ovulatory disturbances and is often associated with central obesity and insulin resistance (IR).3–5 As such, women with PCOS are at an increased risk for a number of health issues, including infertility, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes.3 6 7

Possibly related to the constellation of endocrine and metabolic dysfunction they experience, women with PCOS are also found to have greater chronic subclinical inflammation,8–11 which is often clinically assessed by measuring serum levels of C reactive protein (CRP). CRP is a liver-derived acute phase protein produced in response to IL-6 secreted from activated cells such as macrophages and adipocytes.12 13 A meta-analysis of 31 studies concluded that systemic CRP levels are 96% higher in women with PCOS compared with control women.14 Collectively, these findings have given rise to the speculation that inflammation may play a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of PCOS.8–10

Elevated serum CRP levels are linked to several health risk factors experienced by women with PCOS, particularly IR and heightened risk of type 2 diabetes.7 15 16 Chronic inflammation also contributes to endothelial dysfunction, exacerbating the development of atherosclerotic plaques, triggering the onset of CVD.17 As such inflammation has been associated with both CVD and coronary artery disease in women with PCOS.10

In contrast to CRP, albumin is a negative acute phase response protein produced by the liver. Serum levels of albumin are reduced in individuals experiencing chronic inflammation.18 In addition to its role as a binding molecule for sex steroids,19 albumin also provides the majority of the total antioxidant capacity of normal plasma.18 The ratio of serum CRP levels over serum albumin (CRP/albumin) was found to be strongly associated with more severe metabolic dysfunction in premenopausal women with induced alterations to their ovarian hormone status.20 CRP/albumin ratio was also found to be significantly higher in premenopausal women with PCOS relative to controls, and adversely predicted their bone quality.21 Given the ability of CRP/albumin to simultaneously capture chronic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in premenopausal women, we hypothesised that CRP/albumin ratio may serve as a strong predictor of PCOS in a cohort of similarly aged women. This case–control study investigated CRP/albumin ratio along with classical markers, androgen excess and IR, in their association with PCOS in 319 premenopausal Bahraini Arab women.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

The development of the research question and the study’s setting was influenced by the wish many women in Bahrain have to bear children. Infertility is a consequence of PCOS,22 and the combination of both can impact women’s health-related quality of life.23 Patients were not involved in the design of the study or the recruitment. Study participants will not be recontacted by the study investigators; however, the results of this study will be disseminated to the Bahraini community through press releases of the open access publication.

Study subjects

Women with PCOS (n=200) were recruited from adult obstetrics/gynaecology, endocrinology and outpatient clinics in Manama, Bahrain. Women without PCOS (n=119) were ethnically matched, eumenorrheic university employees and students, and healthy volunteers representative of the Bahraini population. The sample size was based on the ability to detect differences between cases and controls with 10% precision (two-tailed t-test with a=0.05) and 80% power, taking into account the estimated prevalence of PCOS in Bahrain of 7.5%–8.0% (Bahraini Ministry of Health; www.moh.gov.bh/Content/Files/Publications/statistics/HS2015) and Z-value for 95% CI. Women serving as controls were examined in the follicular phase of their menstrual cycle and had testosterone levels within range. A diagnosis of PCOS was based on the 2003 Rotterdam Criteria, which requires two of the three following criteria to be met: ultrasound evidence of polycystic ovarian morphology, anovulation and hyperandrogenism.24 Exclusion criteria included hyperprolactinaemia, non-classical adrenal hyperplasia, androgen-producing tumours, 21-hydroxylase deficiency, Cushing’s syndrome and active thyroid disease (overt, central and subclinical hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism). Additional exclusion criteria included extremes of body mass index (BMI; <18 kg/m2 or >45 kg/m2), recent/present illness and treatment affecting carbohydrate metabolism or hormonal levels, for 3 months or longer before inclusion the study. Women using antihypertensive, oral contraceptive, anti-inflammatory and lipid-lowering drugs were also excluded. Demographic information, along with detailed personal and family history of diabetes, hypertension, infertility, hypercholesterolaemia and ischaemic heart disease were obtained from all participants. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, second guidelines.

Biochemical analysis

Peripheral venous fasting blood samples were obtained between 7:00 and 9:00 following an overnight (>12 hours) fast during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (days 2±5) for control women, or women with PCOS who did not present with menstrual irregularities, or any day for women with PCOS with menstrual irregularities. Serum samples were analysed for sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) by sandwich ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA); assay sensitivity was 0.01 nmol/mL, and interassay and intra-assay precision (CV%) were 5.3% and 4.3%, respectively. Samples were tested in duplicates for adiponectin levels (Cat. No. DRP300) by sandwich ELISA (R&D Systems); assay sensitivity was 0.891 ng/mL, and interassay and intra-assay precision (CV%) were 6.5% and 3.5%, respectively.

Serum luteinising hormone (LH), follicular-stimulating hormone (FSH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), testosterone, glucose (ADVIA Centaur, Bayer Vital, Fernwald, Germany) and insulin (IMMULITE 2000, DPC Biermann, Bad Nauheim, Germany) were measured by automated chemiluminescence immunoassays. Free testosterone (FT) and bioavailable testosterone (BT) and Free Androgen Index (FAI) were determined using FT and BT Calculator (www.issam.ch/freetesto.htm). Progesterone and oestradiol serum levels were quantitated by radioimmunoassay, with comparable CV% (<5%), while dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) levels were measured by solid-phase competitive immunoassay (Immulite; Siemens); interassay and intra-assay CV were 9.4% and 7.0%, respectively.

Concentrations of serum albumin were analysed by photospectrometry with albumin bromocresol purple assay on a COBAS c701 Chemistry Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Dubai, UAE). IR was estimated by the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-IR), defined as fasting serum insulin (IU/mL)×fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L)/22.5. HOMA-IR values were characterised as normal (insulin sensitive) if <2.40; borderline if between 2.40 and 3.50, and high (insulin resistant) if >3.50.

Measurement of plasma high-sensitivity CRP levels was done by latex-enhanced nephelometry on a BN II Nephelometer (Dade Behring, Milan, Italy). Samples were assayed in duplicate in each analytical run; the lower limit of detection was 0.15 mg/L, and the assay range was 0.175–11.0 mg/L (initial dilution). Serial serum dilutions were made in measuring high CRP (>30 mg/L) levels. Percentile CRP values were estimated for comparison purposes.

Statistical analysis

The core outcome set of variables included assessment of CRP/albumin as a predictor of PCOS while controlling for relevant factors, such as BMI and age, and to subsequently compare the strength of the relationship between CRP/albumin and PCOS with variables known to strongly link to the syndrome, namely androgen excess and IR. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to evaluate the distribution of the variables, and many variables for the PCOS cohort were flagged as being non-normally distributed. However, on testing for skewness, we found the values for asymmetry and kurtosis fell between −2 and +2 for all. Thus, we used parametric tests, as suggested,25 given the sample sizes were >30. We reassessed the validity of our analysis by running the Mann-Whitney U test in addition to Student’s t-test for variables we had detected as being non-normal and confirmed that the results were similar. Baseline characteristics were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test and the independent samples t-test for the continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. Numerical variables are presented as mean±SD. Because distribution of CRP/albumin levels was skewed to the right, correlations between CRP/albumin ratio and other continuous variables were assessed using Spearman’s r. Univariate general linear models were applied to test independent associations between CRP/albumin ratio and other independent variables.

The optimal cut-off level for the CRP/albumin ratio was determined by a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and the areas under the curve (AUC) were measured and compared to assess the power of a model to identify patients who experienced metabolic disturbances. Cut-off values showing the greatest accuracy were determined using a sensitivity/specificity versus criterion value plot. Quartiles (ie, 0%–25%, 26%–50%, 51%–75% and 76%–100%) of CRP and CRP/albumin ratio were calculated separately in PCOS and control groups. Because the 25% quartile of CRP value in the PCOS cohort was similar to the standard normal values of CRP, we used the 25% quartile of CRP and CRP/albumin ratio as the cut-off point for both predictors.

Using the calculated cut-off values, regression analysis was performed to determine how well each variable predicted PCOS. To fully explore the role of the CRP/albumin ratio as a biomarker in the prediction of metabolic disturbances, CRP and CRP/albumin ratio were additionally assessed as binary variables. Subjects were categorised into two groups based on the cut-off values and their means (SD) for metabolic markers. IR (HOMA-IR), FT, total adiponectin, BMI and TSH were compared between subjects with normal values, and those who had higher than normal values. P values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS statistics software program V.22 (IBM).

Results

Study subjects

The sociodemographic, anthropometric, clinical and biochemical characteristics of the 200 women with PCOS and 119 controls women are summarised in table 1. Relative to controls, women with PCOS had fewer pregnancies and live births (p<0.001), were more likely to have IR (p<0.001), and differed in education attainment with those with PCOS, having a higher number of high school and postsecondary graduates (p=0.012).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and hormonal characteristics of study population: women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and controls

| All (n=319) |

PCOS (n=200) |

Controls (n=119) |

Mean difference | 95% CI of mean difference | P values | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Age (years) | 27.9 (6.4) | 28.4 (5.9) | 27.2 (7.2) | 1.24 | −0.22 | 2.71 | 0.09 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28 (5.9) | 29 (6.3) | 26.5 (5) | 2.53 | 1.19 | 3.87 | 0.000 |

| Waist/hip ratio | 0.94 (0.09) | 0.94 (0.09) | 0.93 (0.09) | 0.0067 | −0.017 | 0.031 | 0.58 |

| Menarche (years) | 12.5 (1.4) | 12.5 (1.5) | 12.4 (1.2) | 0.12 | −0.21 | 0.45 | 0.47 |

| HOMA-IR | 3.2 (0.18) | 3.8 (0.26) | 2.1 (0.2) | 1.67 | 0.94 | 2.4 | 0.000 |

| QUICKI | 0.6 (0.006) | 0.57 (0.008) | 0.65 (.01) | −0.078 | −0.10 | −0.05 | 0.000 |

| Total adiponectin (ng/L) | 33.8 (1.4) | 28.4 (1.3) | 44.6 (2.9) | −16.25 | −21 | −10 | 0.000 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 37.3 (0.46) | 32.7 (0.46) | 45 (0.35) | −12.22 | −13.52 | −10.93 | 0.000 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 11.1 (1.1) | 15.5 (1.6) | 3.6 (0.85) | 11.89 | 7.61 | 16.17 | 0.000 |

| CRP/albumin ratio | 0.36 (0.04) | 0.53 (0.06) | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.61 | 0.000 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 60.1 (1.5) | 52.2 (1.4) | 72 (2.8) | −19.72 | −26.5 | −13.93 | 0.000 |

| DHEAS (nmol/L) | 6.2 (0.28) | 6.2 (0.29) | 6.3 (0.95) | −0.18 | −0.174 | 1.36 | 0.81 |

| Total testosterone (nmol/L) | 1.7 (0.06) | 1.8 (0.07) | 1.5 (0.1) | 0.23 | −0.02 | 0.49 | 0.08 |

| Bioavailable testosterone (nmol/L) | 0.49 (0.02) | 0.52 (0.03) | 0.42 (0.03) | 0.098 | 0.015 | 0.18 | 0.02 |

| Free Androgen Index | 3.4 (0.16) | 4.0 (0.22) | 2.4 (0.16) | 1.57 | 0.93 | 2.2 | 0.000 |

| Free Testosterone Index | 0.025 (0.001) | 0.029 (0.001) | 0.017 (0.001) | 0.011 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.000 |

Data are presented as means (SD).

BMI, body mass index; CRP, C reactive protein; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance; QUICKI, Quantitative Insulin Sensitivity Check Index; SHBG, sex hormone binding hormone.

Metabolic characteristics

The proportion of women with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 were higher in the PCOS cohort than controls (p<0.001), but the waist to hip ratio was not significantly different (table 1). Serum levels of adiponectin, an adipocyte-associated protein that tends to be inversely linked to visceral adiposity,26 were markedly lower in women with PCOS compared with controls. Fasting plasma glucose, cholesterol, high-density lipoproteins (HDL), low-density lipoproteins (LDL) and triglyceride levels did not differ significantly between women with and without PCOS. However, indices of IR and insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR and Quantitative Insulin Sensitivity Check Index) indicated that women with PCOS had greater impaired regulation of insulin compared with controls (table 1).

Reproductive hormone characteristics

There were no statistically significant differences in plasma levels of oestradiol, progesterone, total testosterone, prolactin, FSH, LH and DHEAS between women with and without PCOS. FT was higher and SHBG lower in women with PCOS (table 1).

CRP/albumin ratio stratified by BMI

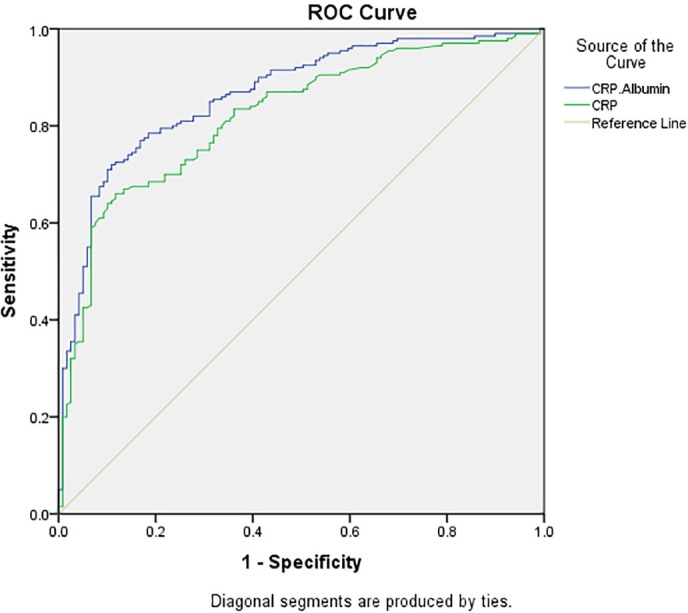

Women with PCOS had markedly higher levels of CRP and lower levels of serum albumin relative to controls (p<0.001; table 1). ROC curve analysis showed that the CRP/albumin ratio had greater discriminatory power to differentiate between women with PCOS and controls (AUC: 0.865, 95% CI 0.824 to 0.905) compared with CRP alone (AUC 0.820, 95% CI 0.773 to 0.867); figure 1. This greater efficacy of CRP/albumin ratio to discriminate between cases and controls was also evident when taking into account the presence of IR at every measure of sensitivity; for a sensitivity level of 75%, CRP/albumin ratio had a specificity of 85% compared with 69% for CRP alone.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve plotting the true positive rate against the false positive rate for CRP/albumin (blue line) and CRP (green line) in differentiating women with and without PCOS. The area under the curve for CRP/albumin: 0.865, 95% CI 0.824 to 0.905; for CRP 0.820, 95% CI 0.773 to 0.867. BMI, body mass index; CRP, C reactive protein; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome.

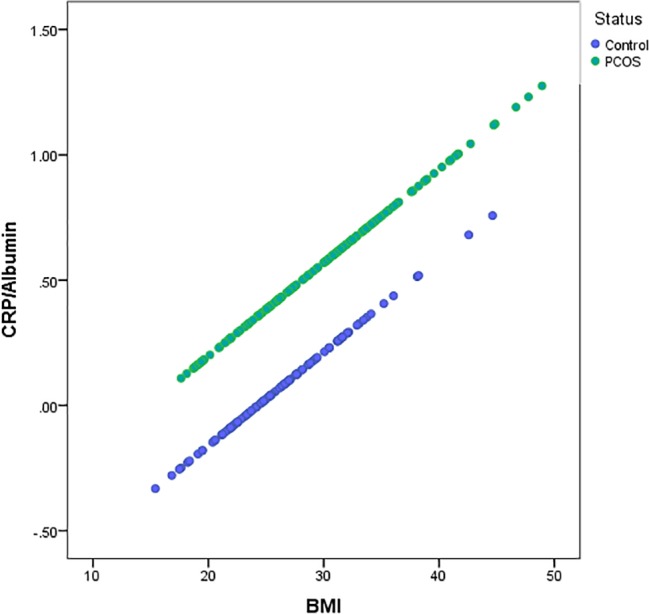

Spearman correlation analysis between CRP/albumin ratios and clinical and biochemical markers was subsequently performed. Variables found to be univariately linked to CRP/albumin values were included in a general linear model testing the relationships among PCOS diagnosis, BMI and CRP/albumin levels. The model revealed that for any given BMI value, women with PCOS have markedly elevated CRP/albumin levels (p<0.001, figure 2).

Figure 2.

Linear regression analysis of adjusted CRP/albumin values by body mass index (BMI) in women with PCOS and controls. A univariate generalised linear model was computed investigating the relationship between CRP/albumin and BMI, adjusting for the variables found to associate with CRP/albumin (insulin, free testosterone, progesterone and adiponectin) plus age stratified by PCOS diagnosis. CRP, C reactive protein; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Variables that are known to strongly associate with PCOS, namely Free Androgen Index and IR, were compared with CRP/albumin ratio as predictors of PCOS in a binary regression analysis stratified by three BMI categories: <25 kg/m2 (normal), 25–30 kg/m2 (overweight), >30 kg/m2 (obese)); table 2. A CRP/albumin ratio of ≥0.097 outperformed both IR and Free Androgen Index in predicting PCOS for every BMI category (table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of binary regression analysis for variables predicting PCOS with the OR of each risk factor adjusted for other variables in the model

| OR (95% CI) | |||

| BMI <25 kg/m2

(normal) |

BMI 25–30 kg/m2(overweight) | BMI ≥30 kg/m2

(obese) |

|

| CRP/albumin ratio* | |||

| <0.097 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥0.097 | 11.21 (3.28 to 39.75) | 19.32 (5.07 to 72.17) | 34.5 (7.75 to 153.52) |

| Insulin resistance† | |||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Borderline | 3.34 (0.645 to 17.33) | 5.58 (0.907 to 34.41) | 3.13 (0.53 to 18.48) |

| Yes | 9.21 (1.63 to 51.93) | 8.81 (1.75 to 44.31) | 17.94 (1.81 to 177.61) |

| Free Androgen Index‡ | |||

| <3.95 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥3.95 | 2.28 (0.536 to 9.75) | 0.86 (0.22 to 3.35) | 3.79 (0.59 to 24.42) |

*Cut-off values were derived from the sensitivity and specificity analysis of the receiver operating characteristic curve.

†Categories of insulin resistance based on normal values used for HOMA-insulin resistance.

‡Cut-off values from normal laboratory reference ranges for Free Androgen Index.

CRP, C reactive protein; HOMA, homeostasis model assessment; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that CRP/albumin ratio is a stronger correlate of PCOS than both free androgens and IR in 319 ethnically matched premenopausal women, and this relationship was independent of BMI. Despite being the most common reproductive disorder to affect women, the aetiology of PCOS has remained elusive to date. In the absence of a definitive cure, treatment has focused on symptom management, and a goal to prevent the progression of serious health conditions, such as type 2 diabetes and CVD, for which women with PCOS are at heightened risk. Chronic low-grade inflammation has emerged as a common underlying state in women with PCOS, and a likely direct contributor to IR and heart disease risk. This has raised the question whether PCOS is fundamentally an inflammatory condition.8 10 27

Small sample sizes, heterogeneous populations and an inability to correct for confounding factors, such as BMI and use of oral contraceptives, both of which influence inflammatory markers such as CRP,21 has in part hampered efforts in assigning inflammation as truly a defining feature of PCOS. This current analysis has overcome some of the main issues in assessing the independent relationship between PCOS and chronic low-grade inflammation. This was accomplished by accounting for many of the confounding variables and by using a more refined marker for inflammation, the CRP/albumin ratio, which may have greater specificity and sensitivity for inflammation associated with metabolic dysfunction. The CRP/albumin ratio was first found to be useful in assessing cardiometabolic and inflammatory status following ovariectomy surgery.20 It was subsequently used to show the influence of chronic subclinical inflammation on bone quality in women with PCOS.21 Although CRP is used to predict cardiovascular risk and is associated with metabolic disorders associated with obesity and IR,28–31 it has been criticised for being too general and non-specific a marker for inflammation.32

When compared with CRP alone, we found that the CRP/albumin ratio has an improved ROC curve for predicting PCOS. Serum albumin, which is commonly measured to assess liver function and malnutrition, is not widely considered as an analyte of interest for PCOS. However, this study showed for the first time that albumin is markedly reduced in women with PCOS relative to controls. This may, at least in part, be due to albumin being a negative acute phase protein.18 It is also possible that there is increased oxidation and glycation of albumin in women with PCOS, which can impact the structure, function and metabolism of the protein.18 Albumin is one of the most abundant serum proteins, and among its many roles is the transport of hormones.19 Thus, reduced albumin levels can potentially contribute to higher free androgens in women with PCOS and exacerbation of disease phenotype.

This analysis was limited by a lack of a more sensitive measure of visceral adiposity; the gold standard is imaging with CT or MRI.33 Furthermore, the case–control design limited the ability to assess how CRP/albumin performs in predicting health outcomes in women with PCOS. Prospective studies are now needed to determine the use of CRP/albumin in predicting the progression of disorders linked to chronic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction that women with PCOS are at increased risk. These include CVD and diabetes, and depression.34–37 Importantly, CRP/albumin ratio may be particularly useful in assessing the effectiveness of new interventions targeting inflammation in women with PCOS as a novel approach to managing the condition and its long-term health consequences.

Conclusion

CRP/albumin ratio, a marker for inflammation related to metabolic dysfunction, was found to have a stronger association with PCOS than either androgen excess or IR. Inflammation is known to be influenced by adiposity, but relative to controls, women with PCOS have higher levels of CRP/albumin ratio irrespective of BMI. This supports the view that inflammation may play a central role in the pathophysiology of PCOS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the women who participated in this research. Without their support and time, this work would not be possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: SK designed the study, interpreted the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AG performed the statistical analysis and helped interpret the analysis. SS and WYA collected all the data, performed the biochemical analysis and managed the clinical operations of the study. AJ assisted with literature review and manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The analysis presented was supported by an operating grant provided by the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute in support of SK.

Competing interests: SK is Director of Scientific Innovation at Qu Biologics, a clinical-stage biotechnology company. All other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Study approval was obtained from the Bahraini Ministry of Health and Arabian Gulf University Research and Ethics Committees (IRB number: 35-PI-01/15) and the Clinical Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia (H16-02101).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Due to subject confidentiality, the complete data cannot be made publicly available. However, researchers who would like controlled access to the data are welcome to contact WYA at: wassim.almawi@outlook.com.

References

- 1. Sirmans SM, Pate KA. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Epidemiol 2013;6:1–13. 10.2147/CLEP.S37559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, et al. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:2745–9. 10.1210/jc.2003-032046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fauser BC, Tarlatzis BC, Rebar RW, et al. Consensus on women’s health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the Amsterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored 3rd PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Fertil Steril 2012;97:28–38. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertil Steril 2009;91:456–88. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Azziz R. PCOS: a diagnostic challenge. Reprod Biomed Online 2004;8:644–8. 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61644-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Legro RS, Kunselman AR, Dodson WC, et al. Prevalence and predictors of risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a prospective, controlled study in 254 affected women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:165–9. 10.1210/jcem.84.1.5393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marciniak A, Nawrocka Rutkowska J, Brodowska A, et al. Cardiovascular system diseases in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome - the role of inflammation process in this pathology and possibility of early diagnosis and prevention. Ann Agric Environ Med 2016;23:537–41. 10.5604/12321966.1226842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shorakae S, Teede H, de Courten B, et al. The Emerging Role of Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation in the Pathophysiology of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Semin Reprod Med 2015;33:257–69. 10.1055/s-0035-1556568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ojeda-Ojeda M, Murri M, Insenser M, et al. Mediators of low-grade chronic inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Curr Pharm Des 2013;19:5775–91. 10.2174/1381612811319320012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Duleba AJ, Dokras A. Is PCOS an inflammatory process? Fertil Steril 2012;97:7–12. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kelly CC, Lyall H, Petrie JR, et al. Low grade chronic inflammation in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:2453–5. 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM. C-reactive protein: a critical update. J Clin Invest 2003;111:1805–12. 10.1172/JCI200318921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lau DC, Dhillon B, Yan H, et al. Adipokines: molecular links between obesity and atheroslcerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005;288:H2031–H2041. 10.1152/ajpheart.01058.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Escobar-Morreale HF, Luque-Ramírez M, González F. Circulating inflammatory markers in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Fertil Steril 2011;95:1048–58. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.11.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Samy N, Hashim M, Sayed M, et al. Clinical significance of inflammatory markers in polycystic ovary syndrome: their relationship to insulin resistance and body mass index. Dis Markers 2009;26:163–70. 10.1155/2009/465203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hughan KS, Tfayli H, Warren-Ulanch JG, et al. Early biomarkers of subclinical atherosclerosis in obese adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Pediatr 2016;168:104,11.e1:104–11. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.09.082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carvalho LML, Ferreira CN, Sóter MO, et al. Microparticles: Inflammatory and haemostatic biomarkers in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2017;443:155–62. 10.1016/j.mce.2017.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Levitt DG, Levitt MD. Human serum albumin homeostasis: a new look at the roles of synthesis, catabolism, renal and gastrointestinal excretion, and the clinical value of serum albumin measurements. Int J Gen Med 2016;9:229–55. 10.2147/IJGM.S102819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zeginiadou T, Kolias S, Kouretas D, et al. Nonlinear binding of sex steroids to albumin and sex hormone binding globulin. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 1997;22:229–35. 10.1007/BF03189812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kalyan S, Hitchcock CL, Sirrs S, et al. Cardiovascular and metabolic effects of medroxyprogesterone acetate versus conjugated equine estrogen after premenopausal hysterectomy with bilateral ovariectomy. Pharmacotherapy 2010;30:442–52. 10.1592/phco.30.5.442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kalyan S, Patel MS, Kingwell E, et al. Competing factors link to bone health in polycystic ovary syndrome: Chronic low-grade inflammation takes a toll. Sci Rep 2017;7:3432 10.1038/s41598-017-03685-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chang RJ. The reproductive phenotype in polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2007;3:688–95. 10.1038/ncpendmet0637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schmid J, Kirchengast S, Vytiska-Binstorfer E, et al. Infertility caused by PCOS-health-related quality of life among Austrian and Moslem immigrant women in Austria. Hum Reprod 2004;19:2251–7. 10.1093/humrep/deh432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2004;81:19–25. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. George D, Mallery P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference: Allyn & Bacon, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lihn AS, Pedersen SB, Richelsen B. Adiponectin: action, regulation and association to insulin sensitivity. Obes Rev 2005;6:13–21. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dimitriadis GK, Kyrou I, Randeva HS. Polycystic ovary syndrome as a proinflammatory state: The role of adipokines. Curr Pharm Des 2016;22:5535–46. 10.2174/1381612822666160726103133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cardoso CR, Leite NC, Salles GF. Prognostic importance of c-reactive protein in high cardiovascular risk patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: The rio de janeiro type 2 diabetes cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e004554 10.1161/JAHA.116.004554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen TH, Gona P, Sutherland PA, et al. Long-term C-reactive protein variability and prediction of metabolic risk. Am J Med 2009;122:53–61. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rutter MK, Meigs JB, Sullivan LM, et al. C-reactive protein, the metabolic syndrome, and prediction of cardiovascular events in the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation 2004;110:380–5. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136581.59584.0E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Choi J, Joseph L, Pilote L. Obesity and C-reactive protein in various populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2013;14:232–44. 10.1111/obr.12003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kraus VB, Jordan JM. Serum C-Reactive Protein (CRP), target for therapy or trouble? Biomark Insights 2007;1:77–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shuster A, Patlas M, Pinthus JH, et al. The clinical importance of visceral adiposity: a critical review of methods for visceral adipose tissue analysis. Br J Radiol 2012;85:1–10. 10.1259/bjr/38447238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Faugere M, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Faget-Agius C, et al. Quality of life is associated with chronic inflammation in depression: A cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord 2018;227:494–7. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chirinos DA, Murdock KW, LeRoy AS, et al. Depressive symptom profiles, cardio-metabolic risk and inflammation: Results from the MIDUS study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017;82:17–25. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barry JA, Kuczmierczyk AR, Hardiman PJ. Anxiety and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 2011;26:2442–51. 10.1093/humrep/der197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dokras A, Clifton S, Futterweit W, et al. Increased risk for abnormal depression scores in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:145–52. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318202b0a4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.