Abstract

Objectives

The clinical severity of IgA nephropathy (IgAN) at the time of biopsy diagnosis differs significantly among cases. One possible determinant of any such difference is the time taken for referral from the primary care physician to a nephrologist, but the definitive cause remains unclear. This study examined the contribution of the number of nephrologists per regional population as a potential social factor influencing the clinical severity at diagnosis among patients with IgAN in Japan, which has an ethnically homogeneous population.

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Setting and participants

Patients were registered in the Japan Renal Biopsy Registry (J-RBR), a nationwide multicentre registry, and 6426 patients diagnosed with IgAN were analysed. The facilities registered to the J-RBR were divided into 10 regions and the clinical features of IgAN at biopsy diagnosis, including renal function and level of proteinuria, were examined.

Main outcome measures

Renal prognosis risk at the time of biopsy diagnosis defined by Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guideline 2012.

Results

Among the regions, there were significant differences in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (67.5–91.4 mL/min/1.73 m2), urinary protein excretion rate (0.93–1.93 g/day) and renal prognosis risk group distribution at diagnosis. The severity of all clinical parameters was inversely correlated with the number of nephrologists per regional population, which showed an up to 2.7-fold difference among regions. A generalised linear mixed model revealed that a low number of nephrologists per regional population were significantly associated with fulfilment of clinical criteria indicating a very-high-risk renal prognosis (β=−0.484, 95% CI −0.959 to −0.010).

Conclusions

Among Japanese patients with IgAN, significant regional differences were detected in clinical severity at the time of diagnosis. Social factors, such as an uneven distribution of nephrologists across regions, may influence the timing of biopsy and determine such differences.

Keywords: IgA nephropathy, renal biopsy, proteinuria, haematuria, chronic kidney disease, glomerulonephritis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is based on the largest nationwide multicentre registry system of renal biopsies in Japan.

The ethnically homogenous Japanese study population provides an opportunity to study the influence of social factors on disease progression.

Because the registry system does not include detailed findings of renal biopsies, this study cannot elucidate the association between the clinical severity and the histopathological grade.

Japan is one of only a few countries in the world that screen for kidney diseases by urinalysis, thus the applicability of the findings to other countries is unclear.

Introduction

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common form of primary glomerulonephritis and a major cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) worldwide.1 2 Impaired renal function and severe proteinuria at presentation are among the strongest predictors of a poor renal prognosis in patients with IgAN.3–5 Advanced age, hypertension, male gender, obesity and haematuria are considered poor prognostic indicators, although controversy exists in the degree of involvement of these factors, which varies by study depending on the subject characteristics.6–9 Previous studies have shown racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of IgAN, and the relative number of patients diagnosed with IgAN is higher in Asian countries than in other countries.10–12 Recent genome-wide analyses have demonstrated that genetic factors may underlie the diversity in the incidence and severity of IgAN.13–16

Except for cases showing gross haematuria, the onset of IgAN is often asymptomatic.17 In addition, IgAN cannot be diagnosed unless a renal biopsy is performed, as deposition of IgA in glomeruli can be demonstrated histopathologically. Social factors, such as the penetration rate of urinalysis screening for kidney disease or the time taken for referral from the primary care physician to a nephrologist, may considerably influence the latency to IgAN diagnosis. In fact, in most patients in Japan, potential cases of IgAN are first identified at a health check-up, followed by referral to a nephrologist to assess the patient.18 19 Such differences in survival related to the duration of disease at time of presentation rather than true variability in disease severity are called lead-time bias, and may also be associated with disease prognosis in patients with IgAN.20

Few studies have focused on regional variation in the clinical characteristics of IgAN.14 16 In addition, other than race/ethnicity, no factors that may affect such regional variation in disease severity have been determined. In this study, we analysed clinical data of patients with IgAN in Japan, which has an ethnically homogeneous population.21 Social factors that may affect the biopsy diagnosis of IgAN were examined in the context of potential differences in the clinical severity of IgAN among various regions of Japan.

Materials and methods

Registry system and patient selection

The Japan Renal Biopsy Registry (J-RBR) is a nationwide, multicentre registry system, which was established in 2007 by the Committee for Standardization of Renal Pathological Diagnosis and the Working Group for the Renal Biopsy Database of the Japanese Society of Nephrology (JSN).22 The J-RBR includes the clinical records for all patients who underwent a renal biopsy including the final renal histopathological diagnosis. However, the registry does not include detailed histopathological findings. This cross-sectional study included Japanese patients with primary IgAN registered on the J-RBR from 1 January 2007 through 30 June 2013. During the registration period, 7970 patients diagnosed with IgAN were included in the J-RBR. Of these 7970 patients, 1544 were excluded because of missing data critical for the analysis, such as renal function measurements, the presence or absence of hypertension and/or the urinary protein excretion (UPE) rate. A total of 6426 patients were finally subjected to the analysis. The diagnosis of IgAN was histopathologically determined based on the basic glomerular changes described in the classification of glomerular diseases of the WHO, and by immunohistological identification of IgA in glomeruli.23 Patients who were diagnosed with other renal or systemic diseases, including those with Henoch-Schönlein purpura, systemic lupus erythematosus and liver cirrhosis, were excluded. Clinical data, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), systolic and diastolic blood pressure, the presence or absence of hypertension, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), UPE rate, urinary sediment, serum albumin and serum total cholesterol, were evaluated. All clinical data were obtained at the time of the diagnostic renal biopsy. The J-RBR is registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (registered number: UMIN000000618).

Measurements and definitions

The J-RBR registration facilities were divided into 10 regions of Japan: Hokkaido, Tohoku, Kanto, Koshinetsu, Hokuriku, Tokai, Kinki, Chugoku, Shikoku and Kyusyu. The Japanese populations in these regions are considered ethnically homogeneous.21

The eGFR was calculated using a three-variable equation modified for Japanese populations as follows: eGFR=194×age−0.287×sCr−1.094 (×0.739 if female), where sCr is the serum creatinine concentration.24 Haematuria was defined as the number of red cells ≥5 per high power field (HPF) in urinary sediment and graded based on the number of red cells per HPF: 0, 1, 2 and 3 for 0–4, 5–10, 11–30 and ≥30, respectively. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg, according to the Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension 2014,25 or usage of antihypertensive medications. Patients ≥65 years of age were defined as elderly.26

In the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease (CKD), patients with CKD are classified into 18 categories and four risk groups (low, moderately increased, high and very high risk) based on eGFR and albuminuria categories on a CKD heat map.27 In Japan, this CKD risk classification system has been modified according to the cause of kidney disease. Except for diabetes cases, the UPE rate, instead of the urinary albumin excretion rate, is applied for patients with CKD including IgAN, based on the requirements of the Japanese national insurance system.28 Based on the KDIGO 2012 guidelines, which were modified for the Japanese population, the UPE rate at the time of biopsy is classified as normal (<0.15 g/day or g/gCr; A1), mild (0.15–0.49 g/day or g/gCr; A2) or severe (≥0.5 g/day or g/gCr; A3).27 28 Similarly, eGFR at the time of biopsy is classified into five groups: G1, G2, G3a, G3b, G4 and G5 for ≥90, 60–89, 45–59, 30–44, 15–29 and <15 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. According to the CKD heat map of the 2012 KDIGO guidelines, which is based on the eGFR level and UPE rate, the renal prognosis is categorised as low, moderately increased, high or very high.

Social factors

Certain social factors may be associated with regional variation in the clinical features of IgAN. The first such factor is the number of board-certified JSN nephrologists per regional population. A qualified JSN board-certified nephrologist must have ≥3 years training at a JSN-accredited facility; have passed a specific exam; and renew their license every 5 years. The second social factor is the proportion of participants who received a health check-up per regional population. To ascertain this, we used data from the Specific Health Checkup, a metabolic syndrome health check-up devised by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan that targets people aged 40–74 years who were enrolled in the national health insurance programme in 2012.29 The Specific Health Checkup comprises a physical examination, blood pressure measurement, blood test and urinalysis. The third social factor is the proportion of elderly persons relative to the general population. Information on the proportion of elderly persons (age ≥65 years) in each regional population was obtained from a national survey performed in 2012 (online supplementary table 1).30 Based on the ranking of the social factors included in this study, 10 regions of Japan were divided into three groups as follows: low (three regions), intermediate (four regions) and high (three regions) groups. Analysis was performed within each group according to the clinical characteristics of the patients with IgAN at the time of biopsy diagnosis.

bmjopen-2018-024317supp001.pdf (57.8KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as means±SD. Differences among regions were analysed by the Kruskal-Wallis test. Differences in the characteristics of the patients with IgAN within each social factor group were analysed by the Mantel-Haenszel test for trend and the Jonckheere-Terpstra trend test, as appropriate. A generalised linear mixed model was constructed to identify the social factors that may influence regional variation in the severity of IgAN at the time of biopsy. In each analysis, social factors, age, sex and the presence or absence of hypertension were treated as fixed covariates, and the regions and the J-RBR registration facilities as random effects. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (V.24.0; IBM).

Patient and public involvement

No patient was involved in the design or conduct of the study, since this was a database research study.

Results

Patient clinical characteristics at the time of biopsy diagnosis

The clinical characteristics of the patients at the time of biopsy diagnosis are summarised in table 1. A total of 1813 (28.2%) patients were categorised into the very-high-risk renal prognosis group. The male and female ratio was similar among the 10 regions. On the other hand, significant regional variation was observed in age, BMI, prevalence of hypertension, eGFR, UPE rate, degree of haematuria and renal prognosis risk group distribution. Notably, there were large differences between the lowest and highest regions with respect to the rates of both very high and low renal prognosis risk, as defined by the KDIGO guidelines.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients at biopsy diagnosis

| Variables | Total (n=6426) |

Hokkaido (n=148) |

Tohoku (n=911) |

Kanto (n=1229) |

Koshinetsu (n=201) |

Hokuriku (n=258) |

Tokai (n=1432) |

Kinki (n=706) |

Chugoku (n=485) |

Shikoku (n=183) |

Kyushu (n=873) |

P values | Maximal fold among regions |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 39.5 (17.7) | 41.5 (16.6) | 42.5 (18.1) | 34.7 (17.5) | 39.2 (14.9) | 42.2 (16.8) | 41.4 (16.6) | 38.9 (17.1) | 39.4 (17.8) | 32.2 (20.2) | 40.8 (18.3) | <0.001 | 1.32 |

| Male, n (%) | 3297 (51.3) | 78 (52.7) | 488 (53.6) | 652 (53.1) | 96 (47.8) | 143 (55.4) | 707 (49.4) | 367 (52.0) | 255 (52.6) | 86 (47.0) | 425 (48.7) | 0.182 | 1.18 |

| BMI mean (SD), kg/m2 | 22.6 (4.0) | 23.4 (4.2) | 23.5 (4.2) | 22.0 (4.2) | 22.2 (3.7) | 22.8 (3.6) | 22.6 (3.7) | 22.4 (4.1) | 22.7 (4.2) | 21.7 (4.0) | 22.7 (4.0) | <0.001 | 1.08 |

| SBP, mean (SD), mm Hg | 124 (18) | 126 (19) | 126 (17) | 120 (18) | 120 (16) | 122 (17) | 127 (18) | 122 (18) | 124 (18) | 117 (16) | 126 (19) | <0.001 | 1.09 |

| DBP, mean (SD), mm Hg | 74 (13) | 76 (13) | 76 (13) | 72 (13) | 75 (13) | 74 (13) | 76 (13) | 73 (12) | 74 (13) | 69 (12) | 75 (13) | <0.001 | 1.10 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2790 (43.4) | 82 (55.4) | 403 (44.2) | 457 (37.2) | 93 (46.3) | 127 (49.2) | 709 (49.5) | 279 (39.5) | 203 (41.9) | 49 (26.8) | 388 (44.4) | <0.001 | 2.07 |

| eGFR, mean (SD), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 74.4 (30.3) | 67.5 (31.3) | 73.3 (29.6) | 79.6 (31.5) | 71.3 (27.7) | 73.2 (27.0) | 69.0 (27.8) | 74.8 (29.3) | 78.0 (30.9) | 91.4 (35.2) | 73.5 (31.2) | <0.001 | 1.35 |

| Serum albumin, mean (SD), g/dL | 3.9 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.7) | 3.8 (1.0) | 3.9 (0.6) | 3.9 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.6) | 3.9 (0.6) | <0.001 | 1.08 |

| Total cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 194 (59) | 198 (45) | 182 (68) | 186 (71) | 188 (71) | 198 (60) | 204 (47) | 199 (49) | 197 (47) | 189 (55) | 198 (59) | <0.001 | 1.12 |

| UPE, mean (SD), g/day | 1.16 (1.62) | 1.93 (2.63) | 1.00 (1.55) | 0.97 (1.25) | 0.93 (1.22) | 1.00 (1.23) | 1.42 (1.72) | 1.04 (1.46) | 0.97 (1.43) | 1.08 (2.31) | 1.35 (1.83) | <0.001 | 2.08 |

| Haematuria grade 2/3, n (%) | 4313 (67.1) | 101 (68.2) | 598 (65.6) | 801 (65.2) | 142 (70.6) | 170 (65.9) | 1024 (71.5) | 454 (64.3) | 327 (67.4) | 94 (51.4) | 602 (69.0) | <0.001 | 1.39 |

| KDIGO prognosis risk of CKD, n (%) | |||||||||||||

| Very high risk | 1813 (28.2) | 59 (39.9) | 265 (29.1) | 289 (23.5) | 61 (30.3) | 64 (24.8) | 495 (34.6) | 175 (24.8) | 117 (24.1) | 20 (10.9) | 268 (30.7) | <0.001 | 3.66 |

| High risk | 2353 (36.6) | 48 (32.4) | 272 (29.9) | 446 (36.3) | 66 (32.8) | 100 (38.8) | 623 (43.5) | 248 (35.1) | 157 (32.4) | 66 (36.1) | 327 (37.5) | <0.001 | 1.45 |

| Moderately increased risk | 1412 (22.0) | 24 (16.2) | 199 (21.8) | 322 (26.2) | 53 (26.4) | 54 (20.9) | 228 (15.9) | 183 (25.9) | 122 (25.2) | 43 (23.5) | 184 (21.1) | <0.001 | 1.66 |

| Low risk | 849 (13.2) | 17 (11.5) | 175 (19.2) | 172 (14.0) | 21 (10.4) | 40 (15.5) | 86 (6.0) | 100 (14.2) | 89 (18.4) | 54 (29.5) | 94 (10.8) | <0.001 | 4.92 |

BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes; SBP, systolic blood pressure; UPE, urinary protein excretion.

Regional variation in social factors

Variations among the 10 regions in terms of the social factors that may influence the severity of IgAN at biopsy diagnosis were assessed (table 2). The social factors included in this study were the number of board-certified nephrologists, proportion of patients who received a health check-up and proportion of elderly persons per regional population. The distributions of these three social factors differed significantly among the 10 regions. In particular, up to 2.7-fold difference among regions was observed in the number of board-certified nephrologists.

Table 2.

Regional variation in social factors

| Regions | Number of nephrologists per 100 000 populations | Proportion of participants who received a health check-up, % | Proportion of elderly persons relative to the general population, % |

| Hokkaido | 1.58 | 36.7 | 26.0 |

| Tohoku | 2.73 | 46.5 | 26.5 |

| Kanto | 4.03 | 46.4 | 22.1 |

| Koshinetsu | 3.26 | 50.5 | 27.0 |

| Hokuriku | 4.24 | 48.7 | 26.2 |

| Tokai | 2.87 | 47.2 | 23.3 |

| Kinki | 3.46 | 40.7 | 24.2 |

| Chugoku | 3.07 | 41.1 | 26.8 |

| Shikoku | 3.05 | 43.1 | 28.1 |

| Kyushu | 3.20 | 43.2 | 25.4 |

| Total mean | 3.40 | 45.0 | 24.2 |

| Maximal fold among regions | 2.68 | 1.38 | 1.27 |

| P values | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Relationships between social factors and regional variation in the clinical characteristics of the patients with IgAN at biopsy diagnosis

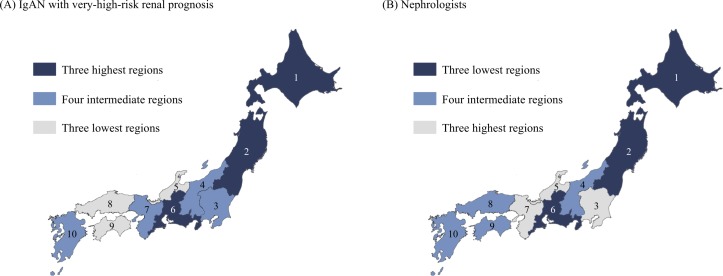

Trends in the social factors were analysed according to regional variation in the clinical features of the patients with IgAN at biopsy diagnosis. The number of nephrologists per regional population showed a clear trend: the fewer the nephrologists, the more severe were the clinical features at the biopsy diagnosis, including renal function, the UPE rate, haematuria and the renal prognosis risk distribution (table 3). The regions with higher proportions of patients with IgAN with a very-high-risk renal prognosis and those with fewer nephrologists per regional population showed a similar distribution trend (figure 1). No such similarities were found between the distribution of patients with IgAN with a very-high-risk renal prognosis and those of health check-up participants or elderly persons per regional population (online supplementary figure 1).

Table 3.

Comparison of patient clinical characteristics among regions categorised according to the number of nephrologists

| Variables | Category of the number of nephrologists | P values for trend | ||

| Lowest three regions (n=2491) | Intermediate four regions (n=1742) | Highest three regions (n=2193) | ||

| Nephrologists per 100 000 populations | 2.59 | 3.16 | 3.86 | |

| Age, mean (SD), year | 41.8 (17.2) | 39.3 (18.2) | 36.9 (17.5) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1194 (47.9) | 733 (42.1) | 863 (39.4) | <0.001 |

| eGFR, mean (SD), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 70.5 (28.7) | 77.3 (30.4) | 77.3 (30.4) | <0.001 |

| UPE, mean (SD), g/day | 1.30 (1.75) | 1.17 (1.74) | 0.99 (1.32) | <0.001 |

| Haematuria grade 2/3, n (%) | 1723 (69.2) | 1165 (66.9) | 1425 (65.0) | 0.002 |

| KDIGO renal prognosis risk, n (%) | ||||

| Very high risk | 819 (32.9) | 465 (26.7) | 528 (24.1) | <0.001 |

| High risk | 943 (37.9) | 616 (35.4) | 794 (36.2) | 0.226 |

| Moderately increased risk | 451 (18.1) | 402 (23.1) | 559 (25.5) | <0.001 |

| Low risk | 278 (11.2) | 259 (14.9) | 312 (14.2) | 0.001 |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes; UPE, urinary protein excretion.

Figure 1.

Distributions of patients with IgA nephropathy (IgAN) with a very-high-risk renal prognosis and nephrologists. Regional differences of the rate of patients with IgAN with a very-high-risk renal prognosis at biopsy diagnosis, which was adjusted for age, sex and hypertension (A), and the number of board-certified nephrologists per regional population (B). Based on the ranking of each factor, 10 regions of Japan were divided into three groups as follows: the three lowest, four intermediate and three highest groups. The numbers indicate the following regions: 1, Hokkaido; 2, Tohoku; 3, Kanto; 4, Koshinetsu; 5, Hokuriku; 6, Tokai; 7, Kinki; 8, Chugoku; 9, Shikoku; 10, Kyushu.

bmjopen-2018-024317supp002.pdf (491.8KB, pdf)

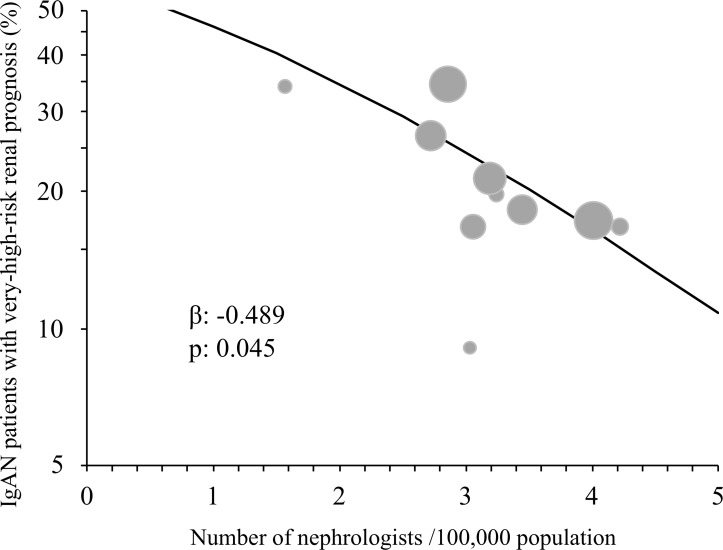

A generalised linear mixed model was constructed to examine the relationship between the three social factors investigated in this study and regional differences in the proportion of patients with IgAN with a very-high-risk renal prognosis at biopsy diagnosis, as defined by the 2012 KDIGO guidelines. In the model, the number of board-certified nephrologists per regional population was significantly associated with the rate of fulfilment of the clinical criteria for a very-high-risk renal prognosis at the biopsy diagnosis, even after considering the differences in clinical factors among regions (table 4, figure 2). We did not find a significant relationship between the rate of very-high-risk renal prognosis at biopsy diagnosis and either the proportion of patients who received a health check-up or the proportion of elderly persons per regional population (table 4).

Table 4.

Social factors and regional variation in patients with IgA nephropathy (IgAN) with very-high-risk renal prognosis

| Fixed effects | f values | Regression coefficient | 95% CI | P values |

| Number of nephrologists (/100 000 populations) | 4.022 | −0.489 | −0.967 to −0.011 | 0.045 |

| Proportion of patients who received a health check-up (%) | 0.521 | 0.033 | −0.056 to 0.122 | 0.471 |

| Proportion of elderly persons relative to the general population (%) | 3.512 | −0.140 | −0.287 to 0.006 | 0.061 |

Covariates: age, sex, hypertension. Random effects: region, Japan Renal Biopsy Registry (J-RBR) registration facility.

Structure for the random effects: first-order autoregressive.

Figure 2.

Relationship between the rate of patients with IgA nephropathy (IgAN) with a very-high-risk renal prognosis and the number of nephrologists per regional population. Circles indicate each region and the areas of the circles are proportional to the regional populations. The rate of patients with IgAN with a very-high-risk renal prognosis in each region was adjusted by age, sex and hypertension. The regression line was obtained from the generalised linear mixed model in table 4.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we demonstrated substantial regional variations in Japanese IgAN patient clinical characteristics at the diagnostic renal biopsy, including eGFR and the UPE rate. In addition, a lower number of board-certified nephrologists per regional population were closely associated with the clinical severity of IgAN, including the rate of fulfilment of clinical criteria for a very-high-risk renal prognosis.

Previous studies have shown apparent regional and national differences in CKD and ESRD incidence in the USA and Europe.31–33 However, race and ethnicity within a study population must be homogenous to identify the effects of social factors on regional differences in clinical factors. The Japanese population is useful for the evaluation of such factors, which may influence disease prevalence and severity, because of its ethnic homogeneity. Usami et al demonstrated significant regional differences in the incidence of ESRD within Japan.34 Studies of the ethnically homogenous Japanese population suggest that social factors, that is, factors other than those with a genetic basis, contribute to such regional differences in the presentation of renal diseases. Similarly, our results pertaining to apparent regional differences in the clinical features of Japanese patients with IgAN at biopsy diagnosis also suggest that such regional variation is due to social rather than genetic factors. However, the results reported here may not be applicable to individuals living outside of Japan, since epigenetic and environmental factors also contribute to disease progression.

This is the first reported study to reveal regional differences in the clinical severity of patients with IgAN at biopsy diagnosis in Japan. Interestingly, the proportion of patients with IgAN fulfilling the clinical criteria for a very-high-risk renal prognosis at biopsy diagnosis showed up to 3.7-fold difference among the 10 regions. Studies on the natural history of IgAN have consistently identified renal impairment and severe proteinuria as clinically detectable poor prognostic indicators at the time of biopsy diagnosis.3–5 In addition, such predictors of the progression to ESRD in patients with IgAN are closely associated with pre-existing histopathological findings of advanced chronic renal disease.35 Thus, our current results showing a significant association between the number of nephrologists per regional population and the clinical severity of patients with IgAN at biopsy diagnosis suggest a possible contribution of nephrologist availability to the likelihood of early diagnosis. The uneven regional distribution of nephrologists may influence the time taken for referral from a primary care physician to a nephrologist, who then decides regarding performance of a renal biopsy and the therapeutic intervention. The number of nephrologists practising in Japan is comparable to that of other developed countries. For example, in Japan there are 34 nephrologists per 1 million population, comparable to the USA and Europe (28 and 31 per 1 million population, respectively).36 However, the number of nephrologists per population in African and southeastern Asian countries is much lower at 1–4 per 1 million population.36 Further studies aimed at understanding the demand and supply for nephrology workforce may help explain the uneven distribution of nephrologists.

Other than the number of nephrologists, several other socioeconomic factors may influence the clinical severity of IgAN. Due to the universal health insurance coverage established in 1961 in Japan, the gap between individuals with a poor medical economic status and the rest of the population is reportedly lower than that in other countries.37 The rate of health check-ups may be another important social factor influencing IgAN severity. Although urinalysis screening is compulsory for school-age children, adult participation in such schemes can show significant variation among regions in Japan. However, we did not find any significant effect of health check-up rate on the severity of IgAN at biopsy diagnosis. One possible interpretation of this result is that referral to a nephrologist may play a more important role than health check-ups in IgAN severity. The proportion of elderly persons in urban and rural populations differs significantly among regions in Japan, a country in which there has been remarkable ageing of rural populations, particularly in recent years. Previous studies have suggested that elderly patients with IgAN have relatively more severe clinical features at the time of diagnosis than younger patients.38 39 Thus, we examined the effect of regional variation in the proportion of elderly persons on the clinical severity of IgAN. However, contrary to our expectations, we did not find any significant effect of the proportion of elderly persons on the severity of IgAN at biopsy diagnosis. Referral to a nephrologist and renal biopsy may be performed less often in elderly patients.

Our study had several important limitations. First, there were differences in both the number of J-RBR registration facilities and the sample size among regions. Second, there may have been differences in the criteria for performing renal biopsies among facilities. Because no formal criteria for performing a renal biopsy are defined in the registry, all renal biopsies were performed at the discretion of the attending physician. This may have influenced the regional differences in severity of clinical features at the time of biopsy. Third, we could not exclude the potential influence of other social factors, such as dietary habits or climatic factors, on the regional variation in clinical features of patients with IgAN. Fourth, the J-RBR does not include histopathological findings of renal biopsies. Thus, we could not demonstrate that the clinical severity of the patients with IgAN correlated with the histopathological findings. Fifth, the applicability of the findings to countries other than Japan is unclear: since Japan is one of only a few countries in the world that screen for kidney diseases by urinalysis. Sixth, we did not fully evaluate haematuria in relation to clinical severity of IgAN. Persistent haematuria in the presence of proteinuria is reportedly associated with the risk for progression to ESRD in IgAN.9 The CKD risk classification system of KDIGO 2012 does not include haematuria27 28 and the association between the degree of haematuria and clinical severity of IgAN is unclear. Finally, it is a cross-sectional study. Therefore, further studies are required to elucidate the relationship between the number of nephrologists per regional population and the renal prognosis of patients with IgAN.

Conclusions

This study identified considerable regional differences in the clinical severity of IgAN at the biopsy diagnosis in Japanese patients. Our results suggest that an uneven distribution of nephrologists across regions may influence the timing of nephrologist referral and biopsy diagnosis, as well as the likelihood of earlier intervention to prevent progression to ESRD in patients with IgAN.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help collecting data for the J-RBR and the assistance of many colleagues in centres and affiliate hospitals. We also sincerely thank Ms M Irie of UMIN-INDICE and Ms Y Saito of JSN for supporting the registration system.

Footnotes

Contributors: Research idea and study design: YO, NT, YM, TK, MO, TY. Data acquisition: YO, NT, IN, TN, HY. Data analysis/interpretation: YO, NT. Statistical analysis: YO, NT, HA, TN. Supervision or mentorship: NT, TY. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The study was supported in part by the committee grant from the Japanese Society of Nephrology (J-RBR201501).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee at which the studies were conducted (the Japanese Society of Nephrology, IRB approval number 27; 19 January 2016) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments, or comparable ethical standards.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. D’Amico G. The commonest glomerulonephritis in the world: IgA nephropathy. Q J Med 1987;64:709–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wyatt RJ, Julian BA. IgA Nephropathy. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2013;368:2402–14. 10.1056/NEJMra1206793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Radford MG, Donadio JV, Bergstralh EJ, et al. Predicting renal outcome in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 1997;8:199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berthoux F, Mohey H, Laurent B, et al. Predicting the risk for dialysis or death in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;22:752–61. 10.1681/ASN.2010040355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barbour SJ, Reich HN. Risk stratification of patients with IgA nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 2012;59:865–73. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.02.326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Manno C, Strippoli GF, D’Altri C, et al. A novel simpler histological classification for renal survival in IgA nephropathy: a retrospective study. Am J Kidney Dis 2007;49:763–75. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duan ZY, Cai GY, Chen YZ, et al. Aging promotes progression of IgA nephropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Nephrol 2013;38:241–52. 10.1159/000354646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Le W, Liang S, Hu Y, et al. Long-term renal survival and related risk factors in patients with IgA nephropathy: results from a cohort of 1155 cases in a Chinese adult population. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:1479–85. 10.1093/ndt/gfr527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sevillano AM, Gutiérrez E, Yuste C, et al. Remission of hematuria improves renal survival in iga nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;28:3089–99. 10.1681/ASN.2017010108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Korbet SM, Genchi RM, Borok RZ, et al. The racial prevalence of glomerular lesions in nephrotic adults. Am J Kidney Dis 1996;27:647–51. 10.1016/S0272-6386(96)90098-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pontier PJ, Patel TG. Racial differences in the prevalence and presentation of glomerular disease in adults. Clin Nephrol 1994;42:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schena FP. A retrospective analysis of the natural history of primary IgA nephropathy worldwide. Am J Med 1990;89:209–15. 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90300-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fischer EG, Harris AA, Carmichael B, et al. IgA nephropathy in the triethnic population of New Mexico. Clin Nephrol 2009;72:163–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kiryluk K, Novak J, Gharavi AG. Pathogenesis of immunoglobulin A nephropathy: recent insight from genetic studies. Annu Rev Med 2013;64:339–56. 10.1146/annurev-med-041811-142014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feehally J, Farrall M, Boland A, et al. HLA has strongest association with IgA nephropathy in genome-wide analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;21:1791–7. 10.1681/ASN.2010010076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kiryluk K, Li Y, Sanna-Cherchi S, et al. Geographic differences in genetic susceptibility to IgA nephropathy: GWAS replication study and geospatial risk analysis. PLoS Genet 2012;8:e1002765 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Szeto CC, Lai FM, To KF, et al. The natural history of immunoglobulin a nephropathy among patients with hematuria and minimal proteinuria. Am J Med 2001;110:434–7. 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00659-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yamagata K, Iseki K, Nitta K, et al. Chronic kidney disease perspectives in Japan and the importance of urinalysis screening. Clin Exp Nephrol 2008;12:1–8. 10.1007/s10157-007-0010-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yamagata K, Takahashi H, Tomida C, et al. Prognosis of asymptomatic hematuria and/or proteinuria in men. High prevalence of IgA nephropathy among proteinuric patients found in mass screening. Nephron 2002;91:34–42. 10.1159/000057602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geddes CC, Rauta V, Gronhagen-Riska C, et al. A tricontinental view of IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003;18:1541–8. 10.1093/ndt/gfg207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yamaguchi-Kabata Y, Nakazono K, Takahashi A, et al. Japanese population structure, based on SNP genotypes from 7003 individuals compared to other ethnic groups: effects on population-based association studies. Am J Hum Genet 2008;83:445–56. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sugiyama H, Yokoyama H, Sato H, et al. Japan Renal Biopsy Registry: the first nationwide, web-based, and prospective registry system of renal biopsies in Japan. Clin Exp Nephrol 2011;15:493–503. 10.1007/s10157-011-0430-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Churg J, Bernstein J, Glassock RJ, Renal disease, classification and atlas of glomerular disease. 2 edn Tokyo: Igaku-Shoin, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;53:982–92. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shimamoto K, Ando K, Fujita T, et al. The japanese society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2014). Hypertens Res 2014;37:253–390. 10.1038/hr.2014.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wolrd Health Organaization website. Good health adds life to years: Global brief for World Health Day 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70853/1/WHO_DCO_WHD_2012.2_eng.pdf (accesed 19 May 2018).

- 27. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2013;3:1–150. 10.1038/kisup.2012.73 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tomino Y. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with IgA nephropathy in Japan. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2016;35:197–203. 10.1016/j.krcp.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare website. Specific health checkups and specific guidance. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/wp/wp-hw3/dl/2-007.pdf (accessed 19 May 2018).

- 30. Population of Japan. Current population estimates as of october 1, 2012. statistic bureau, ministry of internal affairs and communications website. http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/jinsui/2012np/index.htm#a15k24-a (accessed 19 May 2018).

- 31. Tanner RM, Gutiérrez OM, Judd S, et al. Geographic variation in CKD prevalence and ESRD incidence in the United States: results from the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study. Am J Kidney Dis 2013;61:395–403. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Dijk PC, Jager KJ, de Charro F, et al. ERA-EDTA registry. Renal replacement therapy in Europe: the results of a collaborative effort by the ERA-EDTA registry and six national or regional registries. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001;16:1120–9. 10.1093/ndt/16.6.1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brück K, Stel VS, Gambaro G, et al. CKD prevalence varies across the european general population. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;27:2135–47. 10.1681/ASN.2015050542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Usami T, Koyama K, Takeuchi O, et al. Regional variations in the incidence of end-stage renal failure in Japan. JAMA 2000;284:2622–4. 10.1001/jama.284.20.2622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Haas M. Histologic subclassification of IgA nephropathy: a clinicopathologic study of 244 cases. Am J Kidney Dis 1997;29:829–42. 10.1016/S0272-6386(97)90456-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sharif MU, Elsayed ME, Stack AG. The global nephrology workforce: emerging threats and potential solutions!. Clin Kidney J 2016;9:11–22. 10.1093/ckj/sfv111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Abe S. Japan’s vision for a peaceful and healthier world. Lancet 2015;386:2367–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01172-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Frimat L, Hestin D, Aymard B, et al. IgA nephropathy in patients over 50 years of age: a multicentre, prospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996;11:1043–7. 10.1093/ndt/11.6.1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Okabayashi Y, Tsuboi N, Haruhara K, et al. Reduction of proteinuria by therapeutic intervention improves the renal outcome of elderly patients with IgA nephropathy. Clin Exp Nephrol 2016;20:910–7. 10.1007/s10157-016-1239-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024317supp001.pdf (57.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024317supp002.pdf (491.8KB, pdf)