Abstract

TH17 cells originating from regulatory T (Treg) cells upon loss of the Treg-specific transcription factor Foxp3 accumulate in sites of inflammation and aggravate autoimmune diseases. Whether an active mechanism drives the generation of these pathogenic ‘ex-Foxp3 TH17’ cells, remains unclear. Here we show that pro-inflammatory cytokines enhance the expression of transcription regulator Id2, which mediates cellular plasticity of Treg into ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells. Expression of Id2 in in vitro differentiated iTreg cells reduces the expression of Foxp3 by sequestration of the transcription activator E2A, leading to the induction of TH17-related cytokines. Treg-specific ectopic expression of Id2 in mice significantly reduces the Treg compartment and causes immune dysregulation. Cellular fate-mapping experiments reveal enhanced Treg plasticity compared to wild-type, resulting in exacerbated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis pathogenesis or enhanced anti-tumor immunity. Our findings suggest that controlling Id2 expression may provide a novel approach for effective Treg cell immunotherapies for both autoimmunity and cancer.

Regulatory T (Treg) cells may lose the expression of their master transcription factor, Foxp3, and be converted to pro-inflammatory cells. Here the authors show that this lineage plasticity may be mediated by the enhanced expression of another transcription regulator, Id2, which suppresses the transcription of Foxp3 to alter Treg lineage stability.

Introduction

Regulatory T (Treg) cells are a unique population of CD4+ T-cells essential for maintaining immune homeostasis1–4. Stable expression of the X-chromosome encoded transcription factor Foxp3 distinguishes Treg cells from other T-cell lineages5,6, and is a prerequisite for maintaining their suppressive properties. Functional deficiencies in Foxp3 results in overt lymphoproliferation and systemic autoimmune features both in mice and human patients characterized by the “scurfy” phenotype and immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked (IPEX) syndrome respectively7,8.

Classically, each CD4+ T helper (TH) subsets are viewed as terminally differentiated and specialized for their discriminative functions. However, it has been suggested that plasticity within effector CD4+ TH cell populations is capable of exerting flexible immune responses under various physiological conditions9,10. Several reports have revealed that under inflammatory and autoimmune disease conditions, loss of Foxp3 results in high degree conversion of Treg cells towards a TH17-like “ex-Foxp3 TH17” phenotype11–15. Consequently, converted ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells become more pathogenic and contribute to the progression and severity of the disease. The molecular basis of this plasticity remains to be fully characterized.

Id proteins (Id1-Id4) are inhibitors of helix-loop-helix (HLH) DNA binding transcription factors and play diverse roles in immune cell development and function. Id proteins are known to mainly inhibit DNA-binding activities of E proteins, a prevalent HLH domain containing family of transcription factors that include E2A, E2-2, and HEB. Id proteins, which lack any detectable DNA-binding domain, act by interfering with the formation of active homo- or hetero-dimers by E-proteins, a prerequisite for their DNA binding and transcription related activities16–18.

Together with Id3, Id2 has been shown to be an important regulator controlling multiple aspects of CD4+ T cell differentiation. Recently published data suggest that Id2 enhances TH1, but attenuates TFH cell differentiation19. Simultaneous deletion of Id2 and Id3 results in defect in maintenance and localization, and enhanced differentiation towards T follicular regulatory (TFR) subtype of Treg cells20. Furthermore, mice with T cell specific deletion of Id2 display resistance towards experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)21, raising the possibility of its potential function in TH17 mediated pathogenesis.

Here we show that Id2 is induced in Treg cells under various inflammatory settings. Ectopic expression of Id2 results in reduced expression of Foxp3 and enhanced TH17 cell-related cytokines in in vitro induced Treg (iTreg) cells. In mice, Treg cell-specific overexpression of Id2 causes Treg instability, and induces susceptibility to EAE pathogenesis and spontaneous age-related autoimmunity. IL-1β and IL-6 signaling mediated STAT3/IRF4/BATF transcriptional activity is found to be responsible for Id2 induction, which in turn inhibits the binding of E2A to the Foxp3 locus, thereby influencing Treg stability. In a melanoma model of cancer, temporal overexpression of Id2 in Treg cells suppresses tumor growth in mice. Our data thus identify a novel cell intrinsic molecular mechanism underlying Treg cell plasticity with potential therapeutic significance in both autoimmunity and cancer.

Results

Enhanced Id2 expression in ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells

As an initial approach to identify critical factor(s) that might affect the plasticity of Treg cells, we re-analyzed previously published microarray data and compared gene-expression profiles of Treg and ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells14. Since TH17 cells and ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells have similar phenotypes, albeit being of different origin, we also used the TH17 cell gene expression profile alongside for this analysis. We focused on a set of 449 genes which, while are expressed at a low level in iTreg cells in comparison to TH0, are de-repressed in TH17 as well as ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Among these, by employing Gene Ontology (GO) analysis, we focused on the genes that are related to immune system and /or are involved in regulation of transcription (Supplementary Fig. 1b). We identified Id2 as a putative target which is most prominently expressed both in ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells and TH17 cells compared to iTreg cells (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Gene expression data from two other independent studies also implicated Id2 as a potential target. First, Id2 expression in ex-Foxp3 TH17 was dramatically increased compared to Treg cells under inflammatory conditions caused by asthma15 (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Second, Id2 expression negatively correlated with enhanced stability of Rorγt+Foxp3+ Treg cell lineage (Supplementary Fig. 1e)22.

By employing in vitro culture conditions, we next wanted to determine whether enhanced Id2 expression indeed correlates with the TH17 or ex-Foxp3 TH17 differentiation process. We sorted CD4+CD25−CD62LhiCD44lo naive T cells and differentiated them into TH17, iTreg, or ex-Foxp3 TH17 subsets (Fig. 1a). Indeed, Id2 mRNA was found to be highly induced in TH17 cells and ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells compared to iTreg cells (Fig. 1b). A time course analysis to determine Id2 protein expression under similar experimental conditions revealed that its expression in TH17 cells commences at 48 h, a time point at which Rorγt expression starts declining, and TH17 specific cytokines IL-17A and IL-17F are expressed most (Fig. 1c). Id2 protein expression in iTreg differentiation condition however was almost negligible, and the low level of the protein expressed at earlier time points was further reduced when detectable expression of Foxp3 and IL-10 was observed (Fig. 1d). More interestingly, under ex-Foxp3 TH17 polarizing condition, Id2 protein expression was found to gradually increase, mirroring a concomitant reduction in Foxp3 protein level with time (Fig. 1e, upper panel). Furthermore, under these conditions the cells displayed decrease in IL-10 expression and an increase in IL-17A expression, suggesting a bonafide conversion to TH17 phenotype (Fig. 1e, lower panel).

Fig. 1.

Id2 expression is enhanced during a conversion to TH17 phenotype from iTreg cells. a In vitro polarization scheme of TH0, TH17, iTreg and ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells. b RT-qPCR analysis of Id2 mRNA in in vitro generated TH0, TH17, iTreg and ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells; results are presented relative to Hprt expression (n = 3) c, d Western blot analysis to determine the kinetics of indicated proteins during TH17 (c, top panel) and iTreg (d, top panel) cell differentiation and maintenance conditions. β-actin is used as loading control. RT-qPCR analysis of Il17a, Il17f (c, lower panel) and Il10 (d, lower panel) mRNA during each TH17 and iTreg cell differentiation conditions; results are presented relative to Hprt expression (n = 3). e Sorted CD4+ naive T cells were activated in vitro under iTreg cell differentiation condition for 3 days. After 3 days, iTreg cells were re-stimulated in vitro in ex-Foxp3 TH17 polarizing conditions for additional 3 days. Western blot analyses for the indicated proteins were performed after harvesting the cells at indicated time points (top panel). RT-qPCR analysis of Il10 and Il17a mRNA under similar experimental conditions is shown in the lower panel; results are presented relative to Hprt expression (n = 3). *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). Data are representative two independent experiments (error bars, s.d.)

In order to rule out the possibility that the absence of a suitable marker for Treg cells in the above set of experiments may have influenced our interpretation of the results, we also repeated these experiments by using CD4+CD62LhiCD44loFoxp3Thy1.1− T cells sorted from Foxp3Thy1.1 reporter mice, in which Thy1.1 allele is knocked into Foxp3 locus23, as the starting naive population (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Intracellular staining for relevant transcription factors and TH17 related cytokines essentially led to identical conclusions (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c). Furthermore, including an additional culture condition in which TGF-β was excluded from ex-Foxp3 TH17 skewing cocktail revealed that while TGF-β is dispensable for Id2 induction and Foxp3 downregulation, it is required for optimum induction of IL-17A and subsequent downregulation of IL-10 (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Rorγt on the other hand appeared to be only minimally induced only in the presence of TGF-β (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

Id2 promotes iTreg to ex-Foxp3 TH17 differentiation in vitro

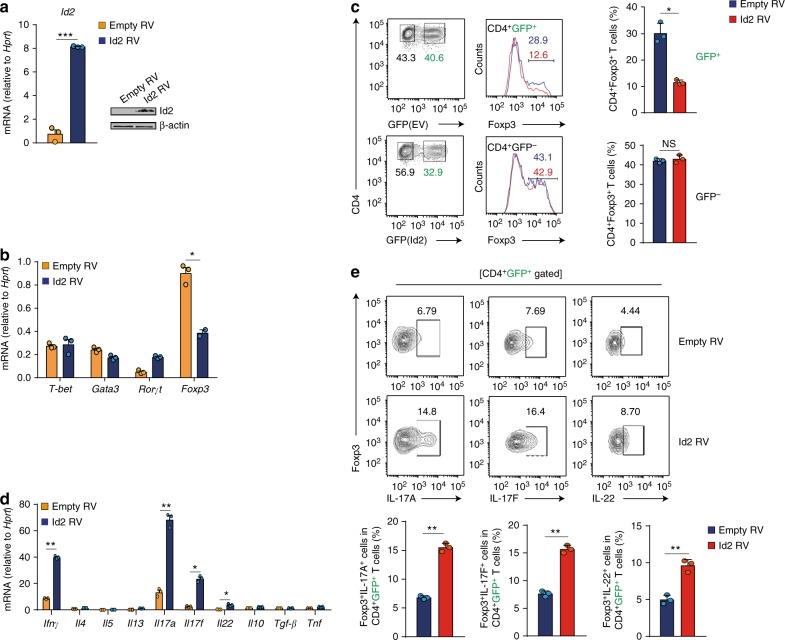

Based on the above results, we hypothesized that Id2 is likely to negatively affect the differentiation process of iTreg cells, and examined the effect of Id2 overexpression during TH17 and iTreg differentiation conditions. Control vector, or a vector encoding Id2 cDNA were retrovirally transduced in T cells, which were skewed towards TH17 or iTreg conditions (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Retroviral expression of Id2 mRNA and protein was confirmed in transduced cells by RT-qPCR and western blot analysis respectively (Fig. 2a). Provision of Id2 in TH17 skewing condition was found to result in enhanced maintenance of Rorγt mRNA and protein (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). IL-17F and IL-22 expressions were also enhanced at mRNA and protein level. Expression of IL-17A, while increased at mRNA level, was found to be comparable in terms of protein expression between vector transduced and Id2 transduced groups at this point, presumably reflecting delayed translation (Supplementary Fig. 3d, e). Conversely, under iTreg differentiation condition, Id2 expression resulted in dramatic reduction in the expression of Foxp3 mRNA and protein, compared to vector control (Fig. 2b, c). Furthermore, iTreg cells, in the presence of excess Id2 displayed enhanced expression of TH1 and TH17 related cytokines IFN-γ, IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 (Fig. 2d, e). Expression of mRNAs encoding TH2 related cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 as well as that of IL-10, TGF-β, and TNF remained unaltered.

Fig. 2.

Overexpression of Id2 in vitro fails to stabilize iTreg lineage commitment, and convert them into TH17-like cells. a Naive CD4+ T cells were sorted from wild-type C57BL/6 (B6) mice, and transduced with control vector (Empty RV) or vector encoding Id2 cDNA (Id2 RV) under iTreg differentiation condition. After 3 days cells were harvested and Id2 expression was measured by RT-qPCR (n = 3, per group) and Western blot analysis. b Comparison of mRNA expression for T-bet, Gata3, Rorγt and Foxp3 between Empty RV and Id2 RV transduced T cells after 3 days post spinfection under iTreg differentiation condition (n = 3, per group). c Flow cytometry analysis of Foxp3 expression between Empty RV or Id2 RV transduced (GFP+) and non-transduced (GFP−) iTreg cells (n = 3, per group). d Comparison of mRNA expression for genes encoding the indicated cytokines between Empty RV and Id2 RV transduced T cells after 3 days post spinfection under iTreg differentiation condition (n = 3, per group). e Flow cytometry analysis of IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-22 from Empty RV or Id2 RV transduced CD4+GFP+ iTreg cells (n = 3, per group). NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 (Student’s t-test). All data are representative two or three independent experiments (error bars, s.d.)

In the above experimental setup T naive cells were differentiated under TH17 or Treg conditions prior to retroviral overexpression of Id2. In order to rule out any discrepancies arising from such non-homogeneous culture conditions, we also performed this experiment under modified conditions whereby cells were activated in the absence of any cytokines one day prior to retroviral transductions. Differentiation was ensued after retroviral transduction. This differentiation condition appeared to be suboptimal, particularly for the cells harboring the retrovirus (GFP+ cells), and resulted in substantially compromised differentiation of the transduced precursors towards respective effector cell types. Nevertheless, overall conclusions from these experiments remained the same remained the same (Supplementary Fig. 4a–g). Taken together, these results indicated that enhanced Id2 expression leads to unstable iTreg lineage commitment, and convert them into TH17-like cells.

Treg-specific ectopic expression of Id2 in vivo

To define the functional role of Id2 in regulation of plasticity of Treg cells, we generated PCMV-lsl-Id2EmGFP mice (Id2EmGFP in short) (Fig. 3a) in which CMV promoter driven cDNA encoding Id2 fused with Emerald Green Florescent Protein (EmGFP) is preceded by loxP flanked mCherry. We crossed Id2EmGFP mice with Foxp3YFP−Cre mice24 and generated Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice (Fig. 3a) in which deletion of the loxP sites would remove the stop codon of mCherry cDNA, resulting in the expression of Id2-EmGFP fusion protein specifically in Treg cells (Fig. 3a, b). Notably, the trans-gene locus in these mice is also equipped with a Tetracycline Operator (TetO) sequence, providing it with the provision of being temporally regulated in a Doxycycline (Dox) dependent manner upon co-expression of the Tetracycline Repressor protein (TetR) (Fig. 3a and see later). As a proof of principle, compared to control Foxp3YFP−Cre, in the Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice we observed a shift in the CD4+CD25+ Treg cells towards a GFPhi population. Expression of Id2 was confirmed in this population by intracellular staining (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Mice with Treg-specific ectopic expression of Id2 displayed enhanced conversion to ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells from Treg cells after induction of EAE. a Schematic representation the mouse model employed. Converging arrows in the lower panel indicate genotyping primers. b Genotyping PCR to detect the presence of Id2-EmGFP transgene in Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice. c Flow cytometry analysis of YFP and EmGFP expression in CD4+CD25+ T cells from spleen (SP) and peripheral lymph nodes (pLN) of Foxp3YFP−Cre and Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice (left panel). Id2 expression was assessed between non-Treg and Treg cells by intracellular staining (right panel). d Schematic of experimental EAE model. e Representative flow cytometry analysis of Id2 expression between tdTomato+YFP+ (Treg) and tdTomato+YFP−(ex-Treg) cells in CD4+ T cells from 6 to 8 week-old R26TFoxp3YFP−Cre mice on day 24 after induction of EAE. f Mean clinical scores in mice after induction of EAE (R26TFoxp3YFP−Cre; n = 12, Id2EmGFPR26TFoxp3YFP−Cre; n = 9). g Representative Spinal Cord (SC) sections and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining from EAE induced mice at day 24 after immunization (scale bar, 100 μm). h Flow cytometry analysis and percentages of Foxp3 sufficient (YFP+) and deficient (YFP−) populations among CD4+tdTomato+ in SP and SC from R26TFoxp3YFP−Cre and Id2EmGFPR26TFoxp3YFP−Cre mice at day 22–24 after induction of EAE. i Representative flow cytometry analysis and percentages of IFN-γ+, IL-17A+ and IFN-γ+IL-17A+ in CD4+tdTomato+ YFP− or CD4+tdTomato+ YFP+ T cells in total SP and SC cells stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin for 6 h. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test). All data are representative of two independent experiments (error bars, s.d.)

Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice were born at the expected mendelian ratios and showed no clinical signs of sickness till 6–8 weeks of age (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Analysis of these mice at this age revealed only moderate increase in frequencies and activation state as determined by CD62LloCD44hi CD4+ and CD8+ T cell compartments (Supplementary Fig. 5b–d). Furthermore, there was only a marginal decrease in CD4+Foxp3+ Treg frequency particularly in the peripheral lymphoid organs (Supplementary Fig. 5e), suggesting that at least under steady state condition, Treg-specific ectopic expression of Id2 does not lead to enhanced loss of Foxp3 at an early age.

To determine whether in contrast to steady state, exposing young Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice to inflammatory conditions would lead to enhanced Treg cell plasticity, we next employed a model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model for multiple sclerosis in which Treg cell instability and conversion to effector T cells is well documented13,25,26. For this we crossed Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice with mice harboring R26lsl−tdTomato (R26T in short) locus (resultant mice called Id2EmGFPR26TFoxp3YFP−Cre or control R26TFoxp3YFP−Cre), in which the cDNA encoding tdTomato is preceded by stop codon flanked by loxP sites, and is expressed upon Cre-mediated recombination. The fate of Foxp3 expression in tdTomato+ cells in these mice could be determined by monitoring YFP-Cre expression. Under this experimental condition upon induction of EAE, as expected even in control R26TFoxp3YFP−Cre mice, increased Id2 expression was observed in the tdTomato+YFP− (ex-Treg) cells, compared to tdTomato+YFP+ (Treg) cells, confirming a correlation between increased Id2 expression and downregulation of Foxp3 (Fig. 3d, e). Importantly, the extent of Id2 expression in these ex-Treg cells was comparable to that observed in Treg cells derived from Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice, suggesting that the ectopic Treg specific expression of Id2 in these mice remains within physiological limit (compare Id2 expression in Fig. 3c, e).

Indeed, compared to controls, the Id2EmGFPR26TFoxp3YFP−Cre mice displayed significantly enhanced disease score throughout the course of the experiment (Fig. 3f, g). This was well correlated with heightened instability of Foxp3 in Id2 expressing cells specifically in spinal cord of diseased mice, as determined by enhanced loss of YFP-Cre expression within tdTomato+ cells in Id2EmGFPR26TFoxp3YFP−Cre mice compared to controls (Fig. 3h). Furthermore, Id2 expressing tdTomato+YFP− cells displayed heightened production of IL-17A, as well as were simultaneous producers of IL-17A and IFN-γ (Fig. 3i).

These results strongly indicated that ectopic expression of Id2 in Treg cells indeed results in heightened instability of Foxp3 expression. However, provided that under certain activated conditions naive T cells are known to express Foxp3, albeit in a transient manner27, there remained a possibility that the increased frequency of tdTomato+YFP− cells upon Id2 overexpression is a result of enhanced accumulation of such promiscuous Foxp3 expressing naive T cells. In order to clarify this issue, we sorted CD4+FITC−tdTomato−CD44loCD62Lhi naive T cells from Id2EmGFPR26TFoxp3YFP−Cre or R26TFoxp3YFP−Cre mice. In order to determine the extent of promiscuous Foxp3 expression from these cells, they were cultured in the presence of TGF-β blocking antibody, a condition that was shown to induce transient Foxp3 induction in vitro27. The extent of promiscuous Foxp3 expression was found to be identical in T cells derived from both mice. A control iTreg induction assay in the presence of TGF-β, as expected, yielded more iTreg cells from T naive cells derived from R26TFoxp3YFP−Cre (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Furthermore, when on the other hand, CD4+FITC+tdTomato+ Treg cells were sorted from these mice and cultured in vitro, the Treg cells derived from Id2EmGFPR26TFoxp3YFP−Cre displayed enhanced instability compared to those derived from R26TFoxp3YFP−Cre mice (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Taken together these results strongly indicated that Treg specific ectopic expression of Id2 results in loss of Foxp3 expression, rather than increased stability of transient Foxp3+ naive T cells.

While the Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice showed little immune dysregulation at a young age, it could be possible that with time due to prolonged presence of Id2, Treg cells in these mice loose Foxp3, resulting in visible autoimmune phenotype. In concert to this hypothesis, indeed at a relatively older age of 12–16 weeks, these mice developed overt autoimmunity, characterized by massive splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy (Fig. 4a). Histological analysis showed dramatic infiltration of lymphocytes into multiple organs such as skin, lung and liver (Fig. 4b). Notably, they had increased percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that were associated with dramatically increased frequencies of CD62LloCD44hi effector memory populations (Fig. 4c–e). Importantly, while CD4+Foxp3+ Treg frequency in the thymus remained largely intact, Treg cell frequency was found to be critically reduced in the pLN and spleen of Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice (Fig. 4f).

Fig. 4.

Treg-cell-specific overexpression of Id2 results in systemic autoimmunity in older mice. a A representative picture of 12–16 week-old Foxp3YFP−Cre and Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice (left) and spleen (SP) and peripheral lymph nodes (pLN) derived from them (right). b Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained skin, lung, liver sections from 12–16 weeks old Foxp3YFP−Cre and Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice (scale bar, 100 μm). c Representative FACS plots and percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from SP and pLN of 12–16 weeks old Foxp3YFP−Cre and Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice. d, e Representative FACS plots and percentages of CD62LhiCD44lo (naive) and CD62LloCD44hi (effector/memory) cells among CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in SP and pLN 12–16 week-old mice. f Representative FACS plots and percentages of Foxp3+ Treg cells in thymus, SP and pLN from 12–16 week-old mice. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 (Student’s t-test). All data are representative three independent experiments (error bars, s.d.)

Together, these data strongly suggest an active role of Id2 in Treg plasticity and pathogenesis accompanied with inflammation caused by autoimmune conditions such as EAE. Furthermore, while mice with Treg-specific overexpression of Id2 remains disease free at an early age, steady loss of Foxp3 expression eventually results in severely diminished Treg compartment and results in systemic autoimmunity later in their life.

IL-1β and IL-6 mediated STAT3/IRF4/BATF induce Id2

Next we sought to determine the cellular and molecular events responsible for driving Id2 expression in Treg cells under inflammatory conditions. In recent years, the roles of two major cytokines, IL-1β and IL-6, in driving Treg plasticity resulting in its phenotypic conversion to TH17-like cells is well documented28–30. We therefore hypothesized that IL-1β and IL-6 signaling may induce Id2 expression in iTreg cells. Indeed, in agreement with this hypothesis we observed that the receptors for both these cytokines, IL-1r1 and IL-6rα were dramatically upregulated under in vitro culture conditions specifically in ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells derived from Foxp3Thy1.1 mice (in which the Thy1.1 allele is knocked into Foxp3 locus23) (Fig. 5a). Conversely, when in vitro differentiated iTreg cells were treated with IL-1β and IL-6, either by themselves in a dose dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 7a), or in combination, resulted in significant upregulation of Id2 transcript and protein expression (Fig. 5b, left panel and 5c). As expected, this was associated with a concomitant reduction in Foxp3 mRNA and protein, and enhanced IL-17A expression (Fig. 5b right panel and Supplementary Fig. 7b). These results strongly suggested that signaling events downstream of IL-1β and IL-6 are major contributors to enhanced Id2 expression in ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells.

Fig. 5.

Id2 is induced by IL-1β and IL-6 mediated signaling and downstream transcription factors STAT3, IRF4 and BATF in Treg cells. a Strategy for sorting TNaive, iTreg, and ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells from Foxp3Thy1.1 reporter mice (left). Flow cytometry analysis of IL-1r1 and IL-6rα among the TNaive, iTreg, and ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells (right). b, c FACS-sorted iTreg cells were re-stimulated with cytokines as indicated and analyzed for Id2 and Foxp3 mRNA expression by RT-qPCR (b) as well as for Id2 protein levels by flow cytometry (c). d Cartoon depicting highly putative STAT3, IRF4, and BATF binding motifs upstream of Id2 transcription start site (TSS). e Cartoon depicting Id2 promoter constructs used for luciferase reporter assay. f Id2 promoter-luciferase construct (−582/+36) were co-transfected with the combination of STAT3, IRF4 and BATF expressing vectors in HEK-293 T cells. Lysates were prepared 30 h after transfection, and luciferase activities were measured with the reporter activities normalized to renilla luciferase activity. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test). All data are representative three independent experiments with similar results (error bars, s.d.)

In order to determine the transcription factors responsible for Id2 upregulation, we next re-analyzed published ChIP-seq data and asked whether any of the five transcription factors previously implicated as “core” determinants of TH17 gene expression program31, is physically associated with Id2 gene locus. Indeed, among these, STAT3, IRF4 and BATF were found to be strongly associated to Id2 locus specifically in TH17 cells, whereas the bindings for the other two factors Rorγt and Maf were relatively less prominent (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Further substantiating this observation, we detected potential binding sites for these transcription factors throughout the upstream gene regulatory regions of Id2 transcription start site (TSS) (Fig. 5d). Finally, by employing luciferase assay based transcription reporter system, we identified a specific region −582 to −147 base pairs upstream of Id2 TSS to be the key region responsive to these transcription factors, most effectively in cooperation with each other (Supplementary Fig. 7d and Fig. 5e, f). Together, these results indicated that IL-1β and IL-6 signaling-mediated STAT3, IRF4, and BATF can induce Id2 expression in Treg cells.

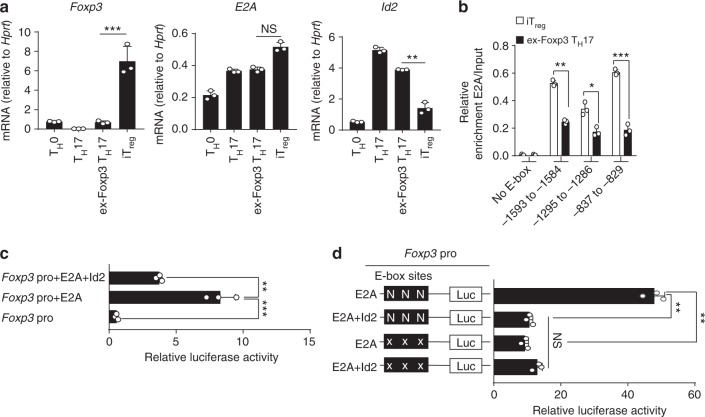

Id2 sequesters E2A from binding to Foxp3 promoter

We next assessed how enhanced level of Id2 in the presence of inflammatory cytokines might repress Foxp3 expression. Id proteins, upon forming non-functional heterodimers, are well known naturally occurring dominant-negative inhibitors of E-protein transcription activators (e.g., E2A, HEB, and E2-2)16–18. Since E2A, one of the best characterized members of the E-protein family, has been previously implicated in promoting transcription of Foxp3 by being physically associating with multiple regions of its promoter32, we hypothesized that Id2 de-repression would potentially sequester E2A, thereby repressing Foxp3 expression. In agreement with this possibility, unlike Foxp3 and Id2, the transcript level of the gene encoding E2A was found to be only minimally affected in iTreg compared to ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells (Fig. 6a), suggesting a post-transcriptional alteration of E2A’s activity might be instrumental.

Fig. 6.

Id2 expression inhibits enrichment and transcriptional activity of E2A on Foxp3 promoter. a RT-qPCR analysis of Foxp3, E2A and Id2 mRNA in in vitro generated TH0, TH17, ex-Foxp3 TH17, and iTreg cells. b ChIP-qPCR analysis for E2A occupancy at three putative E-box sites on Foxp3 promoter regions (−1593 to −1584, −1295 to −1286, and −837 to −829) and negative control (−411 to −244; No E-box site) in iTreg and ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells. Enrichments are calculated relative to the input chromatin for corresponding sites. c Jurkat cells were transfected with either Foxp3 promoter reporter construct alone or along with expression plasmids encoding E2A and Id2 as indicated, followed by luciferase assay. d Effect of mutagenesis on Foxp3 promoter reporter activity. Jurkat cells were transiently co-transfected with the indicated plasmids for luciferase assay as described. N = Normal E box, X = Mutated E box. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test). All data are representative of two or three independent experiments (error bars, s.d.)

Analysis of the DNA sequences encompassing −1702 to +174 of Foxp3 TSS revealed three strong E-protein binding motifs, 1593−1584, 1295–1286, and 837–829 bps upstream to TSS. (Supplementary Fig. 8a). ChIP-qPCR analysis confirmed E2A binding to all of these sites compared to a region with no predicted E-protein binding motif in iTreg cells (Fig. 6b). More importantly, the relative occupancy of E2A to all these sites were significantly reduced in ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells, suggesting functional sequestration of E2A in the presence of Id2 (Supplementary Fig. 8a and Fig. 6b). In agreement to this possibility, in a luciferase based assay system in which the luciferase reporter gene was driven by −1702 to +174 bps encompassing Foxp3 promoter, provision of E2A increased luciferase activity, which was significantly repressed upon co-transfection with Id2 (Fig. 6c). Furthermore, mutating the E-box binding motifs rendered the reporter unresponsive to both E2A and Id2, confirming specificity for E2A (Supplementary Fig. 8b and Fig. 6d). Taken together, these results strongly indicated that increased Id2 can inhibit Foxp3 expression through modulating E2A accessibility to Foxp3 promoter.

Id2 dependent Treg plasticity enhances antitumor immunity

Treg cells are known to promote tumor progression by creating an immunosuppressive tumor environment33–35. Increased Treg cell numbers and function has therefore been associated with suppression of anti-tumor immunity36,37. Also, a low Treg: Teff ratio is associated with better prognosis in cancer38–42.

Since we observed increased inflammation and age dependent plasticity of Treg cell populations in peripheral compartment of Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice, we tested whether Treg cell-specific ectopic expression of Id2 can alter anti-tumor immunity. In order to implement an experimental scheme in which Treg-specific expression of Id2 commences simultaneously with tumor implantation, we employed an inducible model of temporal expression of Id2 in Treg cells by crossing Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice with PCMV-TetR mice (resultant mouse called TetR-Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre). In this model, under steady state condition, TetR binds to the TetO, repressing the expression of Id2-EmGFP protein. Addition of Dox releases this repression (Fig. 7a, b). Mouse melanoma B16.F10 model was induced and doxycycline or control PBS was administered according to the experimental scheme (Fig. 7c). Indeed, Dox-treated mice exhibited protective effect against tumor growth with significant decrease in tumor weight (Fig. 7d–f). Analysis of tumors revealed a correlation between reduced tumor volume and increased CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltrates in Dox-treated animals (Supplementary Fig. 9a). More importantly, reduction in tumor progression in Dox-treated animals was strongly associated with reduced CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cell infiltration within tumor tissue as well as in tumor-draining lymph nodes (dLN) (Fig. 7g). CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) as well as CD8+ T cells isolated from dLN in Dox-treated group had significantly higher IFN-γ expression (Fig. 7h). Consistent with our previous results (Fig. 3i), Id2 overexpressing Treg cells showed higher IL-17A expression in TILs and dLN of Dox-treated tumor bearing mice (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Significant increase in the level of IFN-γ and IL-17A was also observed particularly in CD4+Foxp3− TILs (Supplementary Fig. 9c).

Fig. 7.

Id2 dependent Treg plasticity enhances antitumor immunity. a Schematic for doxycycline (Dox)-inducible Id2 overexpression in Treg cells in TetR-Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice. b Id2 expression was assessed by intracellular staining in SP and pLN from both PBS or Dox treated groups. c Experimental scheme of mouse melanoma model. Females, 8–10 week-old, TetR-Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre mice were injected subcutaneously with B16.F10 cells. Mice were treated intraperitoneally either with PBS or Dox from day 0–9, every 72 h. d Tumor progression, expressed as mean tumor volume (mm3) in both treatment groups (PBS; n = 8, Dox; n = 8). e Representative tumor size in PBS and Dox treated groups on d 23. f Difference in tumor weight, as measured at end point of analysis (PBS; n = 8, Dox; n = 8). g Flow cytometry analysis of CD4+Foxp3+ T cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes (dLN), non-draining lymph nodes (non-dLN) as well as within tumor infiltrated lymphocytes. h Intracellular staining of cytokines in CD8+ T cells isolated from dLN, non-dLN and tumor infiltrated lymphocytes, stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin for 6 h. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test). All data are representative of three independent experiments (error bars, s.d.)

Based on these results, we sought to examine whether ectopic Id2 expression may negatively affect Treg cell suppressive activity. Considering the observation that in tumor microenvironment of Dox-treated mice both CD4+Foxp3− and CD8+ populations displayed enhanced cytokine production, we performed in vitro suppression assays with both CD4+ and CD8+ T naive populations in combination with sorted Treg cells from PBS-treated or Dox-treated animals (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). Indeed Treg cells from Dox-treated mice displayed marginally reduced suppressive activity against proliferation of both CD4+Foxp3−and CD8+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 10b). In agreement to these results, under identical conditions, the CD4+Foxp3− cells were found to produce significantly increased level of IFN-γ and IL-17A. Similar trend in cytokine production was also observed in CD8+ T cells, although the difference did not achieve significance (Supplementary Fig. 10c). Furthermore, as expected the Dox-treated Treg cells under such culture conditions displayed enhanced loss of Foxp3 (Supplementary Fig. 10d), suggesting that at least in part, the defect in suppressive activity observed in Id2 expressing Treg cells is due to instability in Foxp3 expression.

Discussion

Since continuous expression of Foxp3 is required for efficient Treg function, it is evident that cell intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms contributing to stability of Foxp3 are likely to influence multiple aspects of immune activation and tolerance in health and disease. While a number of cis-acting and trans-acting mechanisms have now been identified that positively contribute to transcription and maintenance of Foxp32, whether additional mechanisms exist in order to negatively influence Foxp3’s expression in a context dependent manner, remains less clear. There is increasing evidence suggesting that Treg cells lose their lineage-stability and convert into diverse effector T cell phenotypes under certain inflammatory and lymphopenic conditions both in human and mice11,12,14,15,26,43–45. Under these conditions, Treg cells are readily converted to ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells, impairing immune homeostasis and exacerbating certain immune disorders. In this study, by identifying Id2 to be critical for reprogramming Treg cells towards a TH17 like phenotype in the context of inflammation, we have not only defined a hitherto unidentified mechanistic switch critical for inducing Treg plasticity, we have also identified a novel molecular target that can be potentially modulated in order to reinforce or undermine Treg stability in the context of autoimmunity and cancer.

In recent years, several studies demonstrate that TAZ (a coactivator of TEAD transcription)46 and SGK (serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1)47, as well as Socs1 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 1)48 have critical roles in reciprocally regulating the differentiation of Treg and TH17 cells. However, whether and how the expression of these factors is regulated under conditions promoting Treg plasticity is not fully understood. Here, we showed that Id2 is intrinsically reduced upon Foxp3 expression in Treg cells while highly expressed in TH17 cells, implying opposite role of Id2 between Treg and TH17 lineage compartments. In addition, Id2 is significantly enhanced during the conversion of Treg cells into ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells under inflammatory conditions in vitro and in vivo, indicating that Id2 expression is critically associated with conversion of Treg into ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells.

It is generally recognized that pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12, IL-1β, and IL-6 are the major contributors promoting inflammatory environments suitable for conversion of Treg cells into different types of ex-Treg cells under conditions of varied immune disorders such as ocular infection43, helminth infection49, or autoimmune diseases13–15 (asthma, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis). In particular, IL-1β and IL-6 mediated signaling cascade substantially reduce Treg stability and enhance the conversion of Treg cells to ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells under physiological conditions50. We found that Id2 can be induced in Treg cells upon activation of IL-1β and IL-6 signaling, eventually leading to reduction in Foxp3 expression and promoting TH17 related cytokine expression. Upon re-analysis of previously published high throughput ChIP-seq data, combined with luciferase assay based transcription analysis we implicated the transcription factors STAT3, BATF and IRF4, all of which are core members of the TH17 transcription network, are involved in this process. However, what factor(s) contribute towards limiting the expression of Id2 in Treg cells is still unclear. Since green fluorescent protein (GFP) mediated functional knock-out of Foxp3, results in upregulation of Id2 in Foxp3GFPKO mice (ref51 and our unpublished data), it seems likely that Foxp3 might act as a direct repressor of Id2 gene expression. However further experiments are required to confirm this possibility.

Upon its induction in pro-inflammatory conditions, Id2 was found to repress Foxp3 expression by sequestering the E-box binding transcription factor E2A from binding to Foxp3 promoter. E2A, a well-known member of the E-protein family, has been previously shown to promote transcription of Foxp3 by physically associating with multiple regions of Foxp3 promoter in Treg cells32. We found that Foxp3 promoter contains three E-protein binding sites in which E2A-mediated enhancement of Foxp3 promoter activity could be significantly repressed upon concomitant expression of Id2. Of note, while well characterized conserved non-coding sequences (CNS1-3) within the Foxp3 locus have been implicated in various aspects of Foxp3 expression as well as maintenance3,5, they did not show any predicted E-protein binding sites, and were found to be dispensable for Id2 mediated repression of Foxp3 (data not shown). Since Treg cells make an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment resulting in compromised anti-tumor immunity33–35, substantial efforts are being made to reduce the number or function of Treg cells in tumor settings38–42. We found that ectopic expression of Id2 in Treg cells resulted in arrested tumor growth in a B16.F10 melanoma model, which was accompanied with loss of Treg cells and concomitant increase in IFN-γ producing cytotoxic T cells. Furthermore, consistent with our previous results, IL-17A was found to be significantly increased within the CD4+Foxp3− tumor infiltrated lymphocytes, suggesting that these ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells maintain their ability to produce pro-inflammatory cytokine. Collectively these results suggest that while increased Treg plasticity may result in detrimental cytokine production under inflammatory conditions, proper understanding of molecular events contributing to such instability can be harnessed in the context of cancer in order to boost anti-tumor immunity. We propose therefore that Id2 is one such molecule that can serve as an attractive target likely to be modulated to implement therapeutic modalities for Treg related disorders in the context or autoimmune disorders as well as cancer.

Methods

Mice

Foxp3YFP−Cre 24 mice and Foxp3Thy1.1 23 mice are described elsewhere. PCMV-lsl-Id2EmGFP and PCMV-TetR transgenic mice were generated from Macrogen, Inc (Seoul, Korea). ROSA26lsl−tdTomato (R26T) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and crossed with conditional Id2 transgenic mice to trace Treg cells stability and plasticity depend on Treg-specific Id2 overexpression. All animals were maintained in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions at POSTECH animal facility. All procedures were approved by the POSTECH Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Microarray analysis

Re-analysis was performed on previously published microarray gene-expression data14 (Gene Expression Omnibus accession code GSE48428) to select putative target genes by comparing gene expression profile of ex-Foxp3 TH17 (ex-Treg) cells with Treg cells. We extracted target gene lists that were at least 2-folds up-regulated in ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells originated from Foxp3+ T cells (P = 9.29e−92 and TH17 (P = 1.84e−64) compared to Treg cells and at least 2-folds down-regulated in Treg cells (P = 4.97e−59) compared to TH0 cells. Similar Id2 expression patterns were confirmed from two different independent studies15,22 (Gene Expression Omnibus accession code GSE80804 and GSE60059 respectively). Data were presented as heat map by using R-Studio.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Fixable Viability Dyes (eBioscience) were used at 1:1000 dilution to label dead cells. For surface staining, cells were stained with the following fluorescence-conjugated antibodies (eBioscience, Biolegend, Tonbo): anti-CD4 (RM4-5), anti-CD8 (53–6.7), anti-CD25 (PC61), anti-CD44 (IM7), anti-CD62L (MEL-14), anti-Thy1.1 (OX-7), IL-1R (JAMA-147), IL-6Rα (D7715A7) were used at 1:400 dilution. For intracellular staining, surface stained cells were fixed and permeabilized with a Foxp3 staining kit (eBioscience) according to manufacturer’s instruction and were stained with the following antibodies: anti-Foxp3 (FJK-16s), anti-Rorγt (AFKJS-9), anti-Id2 (ab166708; Abcam), anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2), anti-IL-17A (TC11-18H10.1), anti-IL-17F (eBio18F10), anti-IL-22(1H8PWSR), anti-IL10 (JES5−16E3) were used at 1:200 dilution. For intracellular cytokine staining of cytokines, cells were stimulated by phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin for 6 h in the presence of Golgi-Plug (555029, BD) or Golgi-Stop (554724, BD). Data from the stained cells were collected with LSR Fortessa flow cytometer analyzer equipped with 5 lasers with DIVA software (BD Biosciences) and were analyzed by FlowJo software (Treestar). Gating strategies for FACS sorting are described in Supplementary Fig. 11.

In vitro CD4+ T cell differentiation

For CD4+ T helper (TH) cell differentiation, purified naive CD4+CD25−CD62LhiCD44lo T cells from wild-type C57BL/6 (B6) mice or CD4+CD25−CD62LhiCD44loThy1.1− T cells from Foxp3Thy1.1 mice (1 × 106/ml) were activated with plate-bound αCD3 (1 μg/ml; 1452C11; Bio Xcell) and αCD28 (2 μg/ml; clone 37.51; Bio Xcell) antibodies in the presence of appropriate cytokines. TH0: anti-IL-4 (10 μg/ml), anti-IFN-γ (10 μg/ml; XMG 1.2; Bio Xcell) and 100U/ml of recombinant human IL-2(rhIL-2), TH17: rIL-1β (20 ng/ml), rIL-6 (20 ng/ml), hTGF-β1 (2 ng/ml), anti-IL-4 (10 μg/ml) and anti-IFN-γ (10 μg/ml) or iTreg: rhIL-2(100U/ml) and human TGF-β1 (hTGF-β1; 5 ng/ml) conditions in T cell media. 100 U/ml of rhIL-2 (TH0 and iTreg) and 30 U/ml of rhIL-2 and rIL-23 (10 ng/ml) (TH17) were added on 3 days after detaching from αCD3/αCD28 antibodies, and the cells were expanded in complete T cell media additional for 2 days.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted by TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, USA). For reverse transcription, cDNA was generated using 500 ng of total RNA, oligo(dT) primer (Promega) and Improm-II Reverse Transcriptase (Promega) in a total volume of 20 μl. One microliter of cDNA was amplified by SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Japan) using DNA Engine with Rotor-gene Q (Qiagen, Valencia, USA). Mouse hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) was used for normalization. All primers used in this study are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Induction and assessment of EAE

Mice were immunized subcutaneously with 200 μg/ml of MOG 33−55 peptide (AnyGen, Korea) with CFA containing 4 mg/ml heat-killed M. tuberculosis. At 0 days and 2 days, 2 μg/ml of pertussis toxin suspended in PBS was injected to immunized mice by intraperitoneal injection. Clinical scores were monitored every other day (0: Normal behavior, 1: Tail paralysis, 2: Hind legs paralysis, 3: Front legs paralysis, 4: Full paralysis, 5: Death).

Histology

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 3μm thickness, followed by hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) and eosin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) (H&E) staining. The images were captured by Leica DFC425 C microscopy.

Plasmids and retroviral transduction

Retroviruses were produced by transfecting 6 µg of the retroviral expression vector together with 4 µg of the retroviral packaging vector (pCL-Eco) into Plat-E packaging cells in culture media (DMEM+ 10% FBS). Forty-eight hours after transfection, high-titer viral supernatant was collected. Each differentiating CD4+ T cells was transduced with control (MigR1-GFP) or Id2 expressing retrovirus (MigR1-Id2-GFP) at 24 h after in vitro stimulation. The transduction was performed in a 12-well plate by spinning for 90 min at 2500 rpm, room temperature in the presence of 8 µg/ml of polybrene. The transduced cells were analyzed 3 days after the start of culture.

Western blot analysis

Cells (1–5 × 106) from in vitro generated TH17, iTreg and ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells from TNaive (CD4+CD62LhiCD44lo) cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were detected using the following antibodies: Primary, anti-Mouse Foxp3 (FJK-16s, eBioscience), anti-Mouse Roγrt (Rorg2, Biolegend), anti-Mouse Id2 (166708, Abcam), anti-Mouse beta Actin (8226, Abcam); Secondary, anti-Rabbit IgG HRP (AbC-5003, AbClon), anti-Armenian Hamster IgG HRP (2443, Santa Cruz), anti-Mouse IgG HRP (AbC5001, Abclon). Images were captured by using a ImageQuantTM LAS4000 (GE Healthcare). Complete scanned gels for western blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 12.

Plasmids and luciferase reporter assays

HEK-293 T cells or Jurkat cells were transfected using FuGENE® HD (Promega) or NucleofectorTM (Lonza) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and plated in 12 well plate. 0.5 μg of the Id2 promoter-luciferase constructs or pGL4.17 empty vector was co-transfected with STAT3 (MR227265; Origene), IRF4 (MR226642; Origene) and BATF (MR222114; Origene) expression plasmids (HEK-293 T) and 1 μg of the Foxp3 promoter-luciferase construct was co-transfected with E2A (MG209745; Origene) and Id2 (MR200792; Origene) expression plasmids (Jurkat). Lysates were prepared 30 h after transfection, and luciferase activities were measured with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). The reporter activities were normalized to renilla luciferase activity. Mutations of E2A binding sites were done by using the GeneArt™ Site-Directed Mutagenesis PLUS System kit (Invitrogen).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

CD4+Foxp3+ iTreg cells (5–7 × 106) or CD4+Foxp3− ex-Foxp3 TH17 cells originated from iTreg cells (5–7 × 106) were used. An equal amount of processed chromatin was used as an input control or was incubated with 4 μg antibody to purified mouse anti-human E47(G127-32; BD Biosciences). Immunoprecipitated DNA and total input DNA were analyzed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Japan) using DNA Engine with Rotor-gene Q (Qiagen, Valencia, USA). PCR primers for the detection of each Foxp3 promoters were as follows: Foxp3 amplicon 1 (−411 to −244; No E-box binding sites), 5′-GGATGCCTTTGTGATTTGAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTTGCCCTTTACAAGTCATCTG-3′ (reverse); Foxp3 amplicon 2 (−1593 to −1584; E-box BS1), 5′-GATACCTGGAACTCTTAGCTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTCATAGAAGTTCTAGGACTTGG-3′ (reverse); and Foxp3 amplicon 3 (−1295 to −1286; E-box BS2), 5′-AACAATACAGCCATGATGAGATGGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCAAAGGTTTAGGATTCTAAACAGC-3′ (reverse). Foxp3 amplicon 4 (−837 to −829; E-box BS3), 5′-TTGCCCTTCTTGGTGATGCT-3′ (forward) and 5′- CATGTTTGTGCTGAGTGCCC-3′ (reverse).

Mouse melanoma model

To establish in vivo mouse tumor model, 0.2 × 106 B16.F10 cells, obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA) were subcutaneously injected in the flank region, on day 0. Inducible Id2 transgenic mice (TetR-Id2EmGFPFoxp3YFP−Cre) were treated with intra-peritoneal injections of either PBS or Doxycycline (50 μg/g mice in 200 µl) on day 0, 3, 6, and 9 to induce Id2 expression in Treg cells. Tumor growth was monitored on alternate days, from day 15 through day 27 post tumor cells injection. Vernier calipers were used for measuring length and width of the tumors and tumor volume was calculated using formula Volume (mm3) = (length × width × width)/2. Euthanasia was performed at the end of experiment or if tumor volume exceeded 2000 mm3 or the tumor growth obstructed the feeding of mice.

In vitro suppression assay

CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells sorted from PBS and Dox treated mice were washed three times with PBS and incubated with responder cells (CD45.1+CD62LhiCD44loFoxp3−CD4+ or CD8+) that were pulsed in 1 ml of PBS with 1uL of a 5 μM CTV stock for 10 min at 37 °C. CTV labeled cells were washed in PBS twice and immediately used. 1 × 105 APC depleted of CD4 and CD8 splenocytes by negative selection (Miltenyi Biotech) were mixed with 5 × 104 CTV-pulsed Foxp3−CD4+ or CD8+ responder cells. Treg and responder cells ratio used as indicated within the figure along with 0.4μg/ml of anti-CD3 in a round bottom 96-well plate. Cultures were incubated for 4 days and then analyzed by flow cytometry to determine CTV dilution as well as intracellular staining for cytokines after stimulation with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin for 6 h in the presence of Golgi plug.

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed using Prism 7.03 software (GraphPad). Significant differences were measured by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test with a 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance was considered as P < 0.05 (*<0.05, **<0.005, ***<0.001).

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank to H. J. Jung and M. O. Lee for technical assistance for cell sorting, and Jonathan Sprent and Yun Kyung Lee for helpful discussions and comments on this study. This research was supported by Institute for Basic Science (Project Code: IBS-R005-D1), and by Global Ph.D. Fellowship Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (Project number: 2015H1A2A1030032).

Author contributions

D.R., S.-H.I. and S.-M.H. designed the experiments and S.-M.H. performed most of the experiments and analyzed the data. G.S. assisted with in vivo tumor models and wrote the corresponding section of the manuscript. R.V. performed the in vitro suppression assays. S.B. performed the blinded clinical scoring on EAE disease and assisted in vitro and in vivo experiments. D.R. and S.-H.I. co-supervised the study. D.R., S.-H.I. and S.-M.H. wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

Previously published microarray data supporting the findings of this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus and are publicly available under the GEO accession number GSE48428, GSE80804 and GSE60059. All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial or non-financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Dipayan Rudra, Email: rudrad@ibs.re.kr.

Sin-Hyeog Im, Email: iimsh@postech.ac.kr.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-07254-2.

References

- 1.Bluestone JA, Abbas AK. Natural versus adaptive regulatory T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:253. doi: 10.1038/nri1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:531–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohkura N, Kitagawa Y, Sakaguchi S. Development and maintenance of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2013;38:414–423. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill JA, Benoist C, Mathis D. Treg cells: guardians for life. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:124. doi: 10.1038/ni0207-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:330. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat. Immunol. 2006;8:191. doi: 10.1038/ni1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett CL, et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:20. doi: 10.1038/83713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Shea JJ, Paul WE. Mechanisms underlying lineage commitment and plasticity of helper CD4+ T cells. Science. 2010;327:1098–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.1178334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy KM, Stockinger B. Effector T cell plasticity: flexibility in the face of changing circumstances. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:674–680. doi: 10.1038/ni.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duarte JH, Zelenay S, Bergman ML, Martins AC, Demengeot J. Natural Treg cells spontaneously differentiate into pathogenic helper cells in lymphopenic conditions. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:948–955. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou X, et al. Instability of the transcription factor Foxp3 leads to the generation of pathogenic memory T cells in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:1000–1007. doi: 10.1038/ni.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleinewietfeld M, Hafler DA. The plasticity of human Treg and Th17 cells and its role in autoimmunity. Semin. Immunol. 2013;25:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komatsu N, et al. Pathogenic conversion of Foxp3+T cells into TH17 cells in autoimmune arthritis. Nat. Med. 2014;20:62–68. doi: 10.1038/nm.3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massoud AH, et al. An asthma-associated IL4R variant exacerbates airway inflammation by promoting conversion of regulatory T cells to TH17-like cells. Nat. Med. 2016;22:1013–1022. doi: 10.1038/nm.4147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins and lymphocyte development. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1079–1086. doi: 10.1038/ni1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kee BL. E and ID proteins branch out. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:175–184. doi: 10.1038/nri2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ling F, Kang B, Sun XH. Id proteins: small molecules, mighty regulators. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2014;110:189–216. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405943-6.00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaw LA, et al. Id2 reinforces TH1 differentiation and inhibits E2A to repress TFH differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:834–843. doi: 10.1038/ni.3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyazaki M, et al. Id2 and Id3 maintain the regulatory T cell pool to suppress inflammatory disease. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:767–776. doi: 10.1038/ni.2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin YY, et al. Transcriptional regulator Id2 is required for the CD4 T cell immune response in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 2012;189:1400–1405. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang BH, et al. Foxp3+T cells expressing RORγt represent a stable regulatory T-cell effector lineage with enhanced suppressive capacity during intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;9:444. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liston A, et al. Differentiation of regulatory Foxp3+T cells in the thymic cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2008;105:11903–11908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801506105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubtsov YP, et al. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity. 2008;28:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitz A, et al. AKT isoforms modulate Th1‐like Treg generation and function in human autoimmune disease. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1169–1183. doi: 10.15252/embr.201541905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dominguez-Villar M, Baecher-Allan CM, Hafler DA. Identification of T helper type 1–like, Foxp3+regulatory T cells in human autoimmune disease. Nat. Med. 2011;17:673. doi: 10.1038/nm.2389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyao T, et al. Plasticity of Foxp3(+) T cells reflects promiscuous Foxp3 expression in conventional T cells but not reprogramming of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2012;36:262–275. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ikeda S, et al. Excess IL-1 signaling enhances the development of Th17 cells by downregulating TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 expression. J. Immunol. 2014;192:1449–1458. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimura A, Kishimoto T. IL-6: regulator of Treg/Th17 balance. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010;40:1830–1835. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noack M, Miossec P. Th17 and regulatory T cell balance in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 2014;13:668–677. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciofani M, et al. A validated regulatory network for Th17 cell specification. Cell. 2012;151:289–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maruyama T, et al. Control of the differentiation of regulatory T cells and T(H)17 cells by the DNA-binding inhibitor Id3. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:86–95. doi: 10.1038/ni.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou W. Regulatory T cells, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:295. doi: 10.1038/nri1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishikawa H, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2014;27:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu P, et al. Intratumor depletion of CD4+ cells unmasks tumor immunogenicity leading to the rejection of late-stage tumors. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:779–791. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curiel TJ, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat. Med. 2004;10:942. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fu J, et al. Increased regulatory T cells correlate with CD8 T-cell impairment and poor survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2328–2339. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dannull J, et al. Enhancement of vaccine-mediated antitumor immunity in cancer patients after depletion of regulatory T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:3623–3633. doi: 10.1172/JCI25947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turk MJ, Guevara-Patiño JA, Rizzuto GA, Engelhorn ME, Houghton AN. Concomitant tumor immunity to a poorly immunogenic melanoma is prevented by regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:771–782. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Attia P, Maker AV, Haworth LR, Rogers-Freezer L, Rosenberg SA. Inability of a fusion protein of IL-2 and diphtheria toxin (Denileukin Diftitox, DAB389IL-2, ONTAK) to eliminate regulatory T lymphocytes in patients With melanoma. J. Immunother. 2005;28:582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000175468.19742.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka H, Tanaka J, Kjaergaard J, Shu S. Depletion of CD4+CD25+ rRegulatory cells augments the generation of specific immune T cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes. J. Immunother. 2002;25:207–217. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zou W. Immunosuppressive networks in the tumour environment and their therapeutic relevance. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:263. doi: 10.1038/nrc1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhela Siddheshvar, Varanasi Siva Karthik, Jaggi Ujjaldeep, Sloan Sarah S., Rajasagi Naveen K., Rouse Barry T. The Plasticity and Stability of Regulatory T Cells during Viral-Induced Inflammatory Lesions. The Journal of Immunology. 2017;199(4):1342–1352. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bovenschen HJ, et al. Foxp3+regulatory T cells of psoriasis patients easily differentiate into IL-17A-producing cells and are found in lesional skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011;131:1853–1860. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pelly VS, et al. Interleukin 4 promotes the development of ex-Foxp3 Th2 cells during immunity to intestinal helminths. J. Exp. Med. 2017;214:1809–1826. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geng J, et al. The transcriptional coactivator TAZ regulates reciprocal differentiation of TH17 cells and Treg cells. Nat. Immunol. 2017;18:800. doi: 10.1038/ni.3748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu C, et al. SGK1 governs the reciprocal development of Th17 and regulatory T cells. Cell Rep. 2018;22:653–665. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi R, Nakatsukasa H, Shiozawa S, Yoshimura A. SOCS1 is a key molecule that prevents regulatory T cell plasticity under inflammatory conditions. J. Immunol. 2017;199:149–158. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pelly, V. S. et al. Interleukin 4 promotes the development of ex-Foxp3 Th2 cells during immunity to intestinal helminths. J. Exp. Med. (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Li L, Kim J, Boussiotis VA. IL-1β-mediated signals preferentially drive conversion of regulatory T cells but not conventional T cells into IL-17-producing cells. J. Immunol. 2010;185:4148–4153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gavin MA, et al. Foxp3-dependent programme of regulatory T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2007;445:771. doi: 10.1038/nature05543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Previously published microarray data supporting the findings of this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus and are publicly available under the GEO accession number GSE48428, GSE80804 and GSE60059. All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.