Abstract

In systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), type I interferons (IFN) promote induction of type I IFN stimulated genes (ISG) and can drive B cells to produce autoantibodies. Little is known about the expression of distinct type I IFNs in lupus, particularly high-affinity IFNβ. Single cell analyses of transitional B cells isolated from SLE patients revealed distinct B cell sub-populations, including type I IFN-producers, IFN-responders and mixed IFN-producer/responder clusters. Anti-Ig plus TLR3 stimulation of SLE B cells induced release of bioactive type I IFNs that could stimulate HEK-blue cells. Increased levels of IFNβ were detected in circulating B cells from SLE patients compared to controls and were significantly higher in African American (AA) patients with renal disease and in patients with autoAbs. Together, the results identify type I IFN producing and responding sub-populations within the SLE B cell compartment and suggest that some patients may benefit from specific targeting of IFNβ.

INTRODUCTION

Activation of the type I IFNs, consisting of 13 IFNα and one high-affinity IFNβ sub-types, is highly associated with the development of SLE as well as clinical disease manifestations (1). Type I IFNs can be produced by most cell types though their activity in SLE is most often measured indirectly using the presence of specific type I IFN inducible transcripts, termed the type I IFN signature (1, 2). Previous studies have identified unique type I IFN signatures among different immune cell populations (3–7) but cell-specific expression patterns and roles of distinct type I IFNs in SLE, especially high affinity IFNβ, remain elusive (8), largely due to their low levels of transcription and circulation (9).

In autoimmune mice, IFNAR deficiency ameliorates germinal center (GC) and autoantibody development (10, 11). Although a previous study in NZB mice reported no difference in anti-chromatin Abs or renal disease in Ifnb–⁄– mice (12), these findings have been challenged by reports that IFNβ is elevated and dysregulated in SLE (13, 14) as well as the identification of distinct IFN signatures not restricted to IFNα (15). Serum detection of IFNβ was recently associated with disease flares, particularly in in African American (AA) patients, a population with increased disease prevalence, severity and robust type I IFN dysregulation (14, 16). Autocrine IFNβ signaling has been identified as a mechanism of type I IFN dysregulation in SLE mesenchymal stem cells (13), and B cells have also been shown to produce type I IFNs in SLE and other diseases (9, 17, 18). In this study, we examined expression patterns of type I IFNs and their target ISGs in circulating B cells and identified a potential role for B cell-associated IFNβ in SLE.

METHODS

Clinical Samples.

All SLE subjects met the American College of Rheumatology 1997 revised criteria for SLE (19) and were recruited from the UAB Lupus Clinic. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep/SepMate, StemCell Technologies). Clinical data were determined by the UAB clinical laboratory and attending physician. All data were collected in a double blinded manner.

Study approval.

These studies were conducted in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the institutional review board at UAB. All participants provided informed consent.

Flow Cytometry analysis.

Human antibodies included BioLegend BV510-anti-CD24 (ML5), PE-anti-CD303 (clone 201A), BV510-anti-IgM (clone MHM-88), Pacific-Blue-anti-CD4 (clone RPA-T4), PE-Cy7-anti-CD10 (clone HI10a), BV650-anti-CD27 (O323), Pacific Blue-anti-CD19 (HIB19), PE-Cy7-anti-CD38 (HB-7); Southern Biotech PE-IgD (IADB6), and PBL Assay Science FITC-anti-IFNβ (MMHB-3). Dead cells were excluded from analysis with APC-eFluor® 780 Organic Viability Dye (eBioscience). For intracellular staining, cells were stained with ef780 viability dye, followed by fixation in 2% PFA and 70% ice-cold methanol permeabilization prior to staining. Purity was validated by post-sort analysis of FACS sorted cells to verify that >99% of cells fell into the sort gate after resorting. FACS data were acquired with an LSRII FACS analyzer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star Ashland, OR).

Super-resolution structured illumination microscopy (SIM).

Negative selection purified B cells (StemCell Technologies) were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with Triton X-100, followed by blocking with 2% BSA. Cells were stained with AF647 goat-anti-human IgM (Southern Biotech), FITC mouse-anti-human IFNβ (PBL Assay Science clone MMHB-3) or polyclonal rabbit-anti-human IFNβ (Abcam), followed by anti-rabbit IgG AF488 secondary Ab. DAPI nuclear stain was included for nucleus determination (200 ng/mL).

Super-resolution imaging was carried out using the Nikon N-SIM-E super-resolution microscope (resolution capable of 120 nm x-y and 300 nm z). Images were acquired with a 100× 1.49 NA objective, Orca-Flash 4.0 sCMOS camera (Hamamatsu), 488, 561, and 640 nm laser excitation, a multi-pass dichroic cube and specific emission filters. DAPI images were acquired with a widefield excitation and are at conventional resolution. Images were acquired and reconstructed with Nikon Elements software. Staining intensity and localization of IFNβ were carried out using Fiji/ImageJ.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and real-time PCR reactions were carried out as described previously (20, 21). Primers for GAPDH are: forward, GCACTCACTGGAATGACCTC, backward, TTCTTCGCACTGACACACTG. All primers used for single cell analysis are described in Supplemental Table 1.

Single cell gene expression analyses:

Gene expression analysis of single transitional B cells (CD24+CD38+IgD+CD27–) obtained from SLE PBMCs was performed using the Fluidigm single cell capture and BioMark RT-PCR analysis system (Fluidigm Co., South San Francisco, CA) as described in detail previously (22). Single cell gene expression clustering analysis was carried out using the ClustVis online web tool (23). Single cell gene expression data can be retrieved at https://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/?s=zlbtSCZKfAcPrUg

In vitro B-cell secretion of type I IFN assay.

B cell production of functional type I IFNs was analyzed using coculture of purified primary B cells (5.0 × 105 cells per well) with HEK-Blue IFNα/β cells which expressed an inducible secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) (InvivoGen, San Diego, USA). B cells purified using the Human Pan B Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotech) were were then unstimulated or stimulated for 10 min with an F(ab’)2 anti-hIg (IgM+IgG) antibody (ThermoFisher) (10 µg/mL) plus 5 µg/mL poly(I:C) or 5 µg/mL CL264 (InvivoGen) before HEK-Blue IFNα/β cells (2.5 × 104 cells per well) were added into the medium. Supernatants were collected at the 24 hr time point and were incubated 1 hr with the Quanti-Blue™ colorimetric enzyme assay reagent for determination of absorbance at OD650.

Statistics.

Results are mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) or mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) as described in figure legends. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. Unless otherwise indicated, all analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS and DISCUSSION

Type I IFN producing and response genes in SLE transitional B cells.

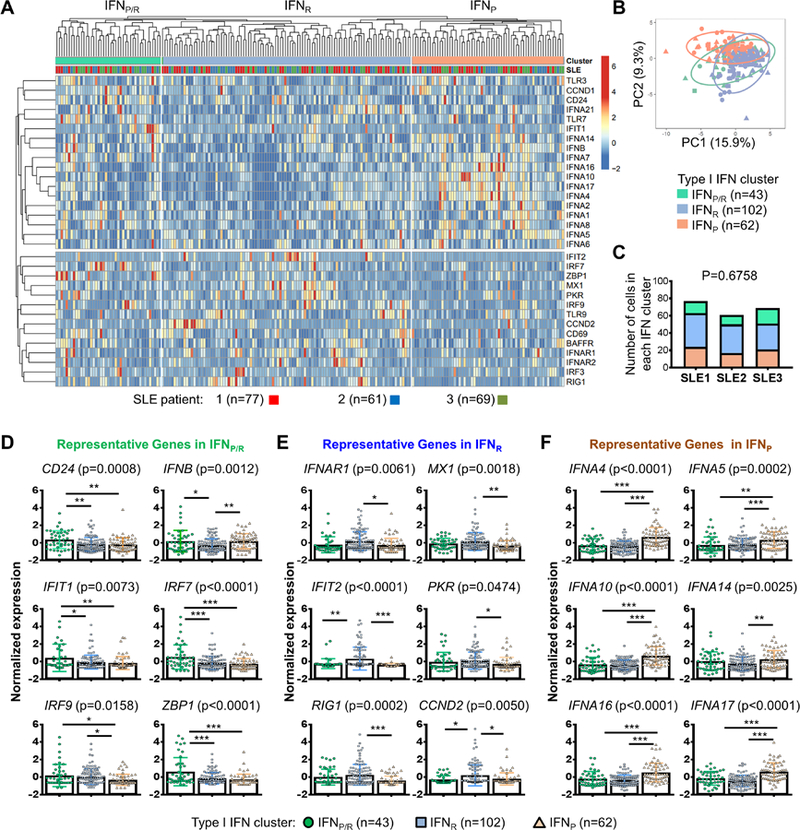

We previously showed that type I IFN expression is a prominent feature of T1 B cell development in BXD2 autoimmune mice and that T1 B cell IFNβ acts in an autocrine priming mechanism to promote Ifna and ISG expression (22). Analysis of type I IFN gene expression from SLE patients revealed a significant increase in the expression of IFNB, IFNA1, IFNA14, IFNA17 and MX1 in transitional (Tr) B cells from African American (AA) patients with SLE (Supplemental Figure 1A). To determine whether distinct type I IFN and ISG gene expression patterns were present in SLE B cells, Tr B cells from three female AA SLE subjects as described in Supplemental Fig. 1B were FACS sorted and analyzed for expression of IFNB, IFNA, and ISGs (Fig. 1A). Hierarchical clustering analysis revealed three prominent clusters with distinct gene signatures, including a mixed IFN and ISG producer/responder signature (IFNP/R), an IFN-responder signature (IFNR) and an IFN-producing signature (IFNP) (Fig. 1A, B, Supplemental Table 1). Cells from all 3 patients were equally represented in each cluster, revealing the presence of these major clusters in different SLE patients (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Type I IFN and ISG gene expression in single transitional B cells from SLE patients.

Transitional B cells (CD24+CD38+IgD+CD27–) isolated from PBMCs of 3 SLE patients (see Supplemental Fig. 1B) were prepared for single cell gene expression analysis. (A) Heat map of hierarchically clustered type I IFN gene expression clustering in individual B cells (n = 207). The top row above the heat map is color-coded to denote cell clustering and SLE patient origin. (B) Principal component analysis of SLE transitional B cell clusters. The X and Y axis show principal component (PC)1 and PC2 that explain 15.9% and 9.3% of the total variance, respectively. PCA was carried out based on PC1 and PC2 segregation of 32 genes in the IFNP/R, IFNP, or IFNR B cell clusters. Prediction ellipses are such that with probability 0.95, a new observation from the same group will fall inside the ellipse. (C) Bar graph showing the number of single cells designated to each type I IFN cluster based on the gene expression profile from each individual SLE patient (Chi-square analysis). (D-F) Dot plots showing the normalized expression of representative genes in the mixed type I IFN producing and responding cluster (IFNP/R) (D), the type I IFN responding cluster (IFNR) (E), and the type I IFN-producing (IFNP) (F) cluster of B cells as defined by hierarchical clustering. All results are mean ± standard deviation. Significant differences among means were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA test with p value shown on the top of each graph. Differences between groups were analyzed using Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Results are shown as mean ± SD (* P < 0.05, ** P <0.01, and *** P < 0.005 between the indicated groups).

Cells within the IFNP/R cluster expressed the highest levels of Tr B cell marker CD24 (Fig. 1D, upper left). Cells within the IFNP/R cluster also expressed higher levels of IFNB, IFIT1, IRF7, IRF9, ZBP1, IFNA1, IFNA7, and CCND1, compared to the IFNR or IFNP cluster or both (Fig. 1D, Supplemental Table 1). This is consistent with our previous observations in BXD2 mice where IFNB expression was upregulated in early T1 B cells (22). Cells within the IFNR cluster expressed higher levels of IFNAR1, MX1, IFIT2, PKR, RIG1 and CCND2 (Fig. 1E). The IFNP cluster was characterized by higher levels of IFNA4, IFNA5, IFNA10, IFNA14, IFNA16 and IFNA17 (Fig. 1F). Expression of TLR3 and TLR7, but not TLR9 were different among the groups (Supplemental Fig. 1C). Single cell gene expression and cell identities were validated by analysis of CD20, CD3, and CD303 expression (Supplemental Fig. 1D). Together, the results reveal heterogeneous type I IFN producing and responding signatures in circulating transitional B cells, suggesting that B cells are not only type I IFN targets, but also producers of type I IFNs in SLE.

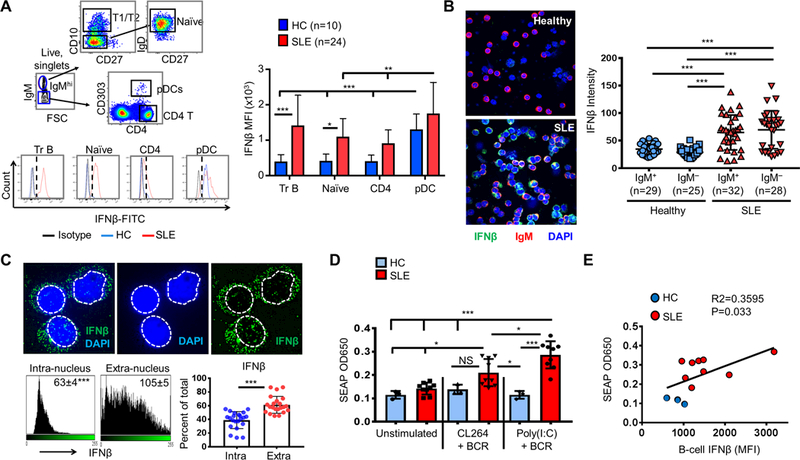

Increased intracellular IFNβ in SLE B cells.

FACS staining (Fig. 2A) and confocal imaging (Fig. 2B) of IFNβ revealed increased levels of IFNβ in B cells from SLE patients compared to HCs. Quantification of IFNβ MFI revealed that while transitional and naïve B cells from SLE patients exhibited significantly increased IFNβ compared to HCs, in CD4 T cells and CD303+CD4low pDCs (24), IFNβ levels were not significantly increased in SLE compared to HCs (Fig. 2A). Staining of IFNβ was specifically inhibited by pre-incubation with human IFNβ, but not mouse IFNα (Supplemental Fig. 2A). We next determined the sub-cellular localization of IFNβ in SLE B cells. Two anti-IFNβ antibodies detected a mainly cytoplasmic distribution of IFNβ in IgM+ B cells (Fig. 2C, Supplemental Fig. 2B). Although significantly less prominent compared to the cytoplasmic localization, IFNβ was also detected in the nucleus (Fig. 2C) as previously reported for other cell types (25, 26). Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic extracts from isolated SLE B cells ex vivo further confirmed the presence of a 25 and 50 kDa band (Supplemental Fig. 2C) consistent with the predicted molecular weight of human IFNβ monomer and dimer (27, 28). Together, these results confirm the presence of cytoplasmic IFNβ in SLE B cells.

Figure 2. Increased expression of intracellular IFNβ in B cells from a subset of SLE patients.

(A) Gating strategy (upper left), representative histograms (lower left), and summary of IFNβ MFI (right) in circulating transitional (Tr) B cells, naïve B cells, CD4 T cells, and pDCs in SLE compared to HC. (B) Confocal microscopy imaging (left) and bar graph quantitation of IFNβ intensity (right) in purified B cells from a representative HC or an SLE patient (objective lens = 20×). (C) SIM super-resolution imaging and analysis of IFNβ intracellular localization in representative B cells from SLE patients. Top: representative images showing intra- versus extra-nuclear staining of IFNβ. The nucleus-cytoplasmic border was defined by DAPI staining (dotted white line). Bottom: ImageJ quantitation of intra and extra-nuclear intensity (left) and distribution (right) of IFNβ (n = 22 cells from 3 SLE patients). (D) HEK-blue reporter cell analysis of type I IFN secretion by B cells from SLE (n=9) or HC (n-3) under the indicated conditions of stimulation. (E) Correlation of FACS detection of baseline (ex vivo) B-cell IFNβ (MFI) with HEK-blue analysis of IFNβ secretion from anti-Ig plus poly(I:C) stimulated B cells.

To determine if B cells produced biologically active type I IFNs, an HEK IFNα/β reporter cell line assay was carried out. Stimulation of the human B cell lymphoma cell line Ramos with TLR3 ligand poly(I:C) induced the highest IFNβ response compared to a TLR7 ligand (CL264) and a TLR9 ligand (ODN-2006) as measured by both intracellular FACS for IFNβ (Supplemental Fig. 2D, left) and by the HEK reporter assay (Supplemental Fig. 2D, right). Stimulation of purified SLE B cells with anti-Ig + TLR3 induced an increased HEK reporter response compared to B cells derived from healthy controls (Fig. 2D). As an additional control, levels of IFNβ measured in the FACS assay were correlated with IFNβ protein secretion as measured by the HEK IFNα/β reporter assay (Fig. 2E). These results are consistent with previous findings by Gram et al (29) which reported type I IFN secretion by human B cells upon poly(I:C) stimulation and further suggest the importance of further evaluation of in vivo TLR3 ligands including U1 RNA that may be associated with B cell type I IFN secretion in SLE patients (30).

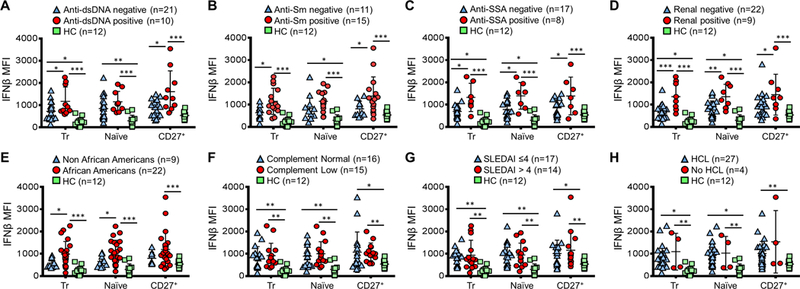

Intracellular IFNβ is associated with autoantibody production, renal disease and AA race.

The higher expression and production of IFNβ from SLE B cells suggest that B cell intracellular IFNβ may be an important factor associated with SLE pathogenesis. We identified that patients who were seropositive for anti-dsDNA at the time of specimen collection exhibited significantly increased levels of IFNβ (MFI) in transitional and CD27+ memory B cells, compared to SLE patients who were seronegative for anti-dsDNA at the time of collection (Fig. 3A). Subjects who were positive for anti-Sm at any time during their disease course exhibited a significant increase in IFNβ levels in transitional and CD27+ memory B cells, whereas subjects who were seropositive for anti-SSA exhibited increased IFNβ expression in transitional, naïve and CD27+ B cells (Fig. 3B–C). These data suggest an association between IFNβ expression and enhanced survival of B cells exhibiting reactivity with nucleic acid/protein complexes able to co-activate BCR and TLR signaling (31).

Figure 3. Elevated B cell IFNβ in autoantibody positive AA SLE patients.

The MFI of IFNβ in the indicated populations of B cells in healthy controls (HC) or in SLE patients segregated by (A) positivity of anti-dsDNA, (B) historic positivity of anti-Sm or (C) anti-SSA (D), the presence of renal disease, (E) race: non-African Americans versus African Americans, and (F) complement (C3/C4) normal versus low, (G) SLEDAI ≤4 versus >4 (and (H) with or without hydroxychloroquine (HCL) treatment. All clinical characteristics, except anti-Sm and anti-SSA, were collected at the time of PBMC sample collection (Results are mean ± SD. Statistical differences were determined by Mann–Whitney U test; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.005 between the indicated comparisons).

SLE subjects with a history of renal disease also exhibited a significant increase in IFNβ in transitional and naïve B cells compared to SLE patients without a history of renal disease (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, intracellular IFNβ in transitional and naïve B cells was significantly higher in AA compared to non-AA patients (Fig. 3E). Levels of IFNβ in SLE B cells were generally significantly higher compared to healthy controls (HC), even in comparisons between autoAb-negative or otherwise low severity patients and HCs (Fig. 3A–E). B cell endogenous IFNβ levels were not significantly different in SLE subjects with low complement or other clinical parameters including SLEDAI or hydroxychloroquine (HCL) treatment, but were significantly higher compared to healthy controls (Fig. 3F–H).

These results suggest that B-cell IFNβ is most strongly associated with increased autoantibodies and renal disease and that polymorphisms in the IFNβ enhanceosome genes or other upstream genes may predispose some patients to the development of type I IFN dysregulation and autoimmune disease (32). This notion supported by recent population level studies which identified the IFNB locus as a trans-regulatory hotspot that controlled antiviral networks enriched in genes differentially expressed in AA vs. European American healthy volunteers (33). Together, the present findings support the importance of cell-specific analyses of both IFNs and IFN response genes in patients of defined ancestral backgrounds, as type I IFN expression may not be highlighted in analyses of patient groups with diverse genetic ancestry. It is important to note that the present PCR-based targeted single-cell gene expression analysis approach was selected in order to detect IFN pathway genes which exhibit a broad expression range spanning from lower expressed type I IFN genes to higher expressed ISGs. The detection of type I IFN genes may be more challenging in conventional RNA-seq analyses as detection of these genes can be limited by read-depth. The present single-cell analyses reveal a new level of understanding in type I IFN dysregulation, as the proper regulation of these type I IFN-producing and -responding populations in early B cells may influence functional cell trajectories.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from R01-AI-071110, R01 AI134023, I01BX004049, 1I01BX000600 and Lupus Research Alliance Distinguished Innovator Award to J.D.M, R01-AI-083705 and the LRA Novel Research Award to H-C.H., 2T32AI007051–39 Immunology T32 Training Grant and the LFA Finzi Summer Fellowship to support J.A.H., NIH 5R37AI049660; U19 AI110483 (Autoimmunity Center of Excellence)(to I.S.), and the P30-AR-048311 and the P30-AI-027767 to support flow cytometry and confocal imaging analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crow MK 2014. Type I interferon in the pathogenesis of lupus. J Immunol 192: 5459–5468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, Karypis G, Gaffney PM, Ortmann WA, Espe KJ, Shark KB, Grande WJ, Hughes KM, Kapur V, Gregersen PK, and Behrens TW. 2003. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 2610–2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker AM, Dao KH, Han BK, Kornu R, Lakhanpal S, Mobley AB, Li QZ, Lian Y, Wu T, Reimold AM, Olsen NJ, Karp DR, Chowdhury FZ, Farrar JD, Satterthwaite AB, Mohan C, Lipsky PE, Wakeland EK, and Davis LS. 2013. SLE peripheral blood B cell, T cell and myeloid cell transcriptomes display unique profiles and each subset contributes to the interferon signature. PLoS One 8: e67003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyons PA, McKinney EF, Rayner TF, Hatton A, Woffendin HB, Koukoulaki M, Freeman TC, Jayne DR, Chaudhry AN, and Smith KG. 2010. Novel expression signatures identified by transcriptional analysis of separated leucocyte subsets in systemic lupus erythematosus and vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis 69: 1208–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma S, Jin Z, Rosenzweig E, Rao S, Ko K, and Niewold TB. 2015. Widely divergent transcriptional patterns between SLE patients of different ancestral backgrounds in sorted immune cell populations. J Autoimmun 60: 51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rai R, Chauhan SK, Singh VV, Rai M, and Rai G. 2016. RNA-seq Analysis Reveals Unique Transcriptome Signatures in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients with Distinct Autoantibody Specificities. PLoS One 11: e0166312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Sherbiny YM, Psarras A, Yusof MYM, Hensor EMA, Tooze R, Doody G, Mohamed AAA, McGonagle D, Wittmann M, Emery P, and Vital EM. 2018. A novel two-score system for interferon status segregates autoimmune diseases and correlates with clinical features. Sci Rep 8: 5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crow MK 2016. Autoimmunity: Interferon alpha or beta: which is the culprit in autoimmune disease? Nat Rev Rheumatol 12: 439–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodero MP, Decalf J, Bondet V, Hunt D, Rice GI, Werneke S, McGlasson SL, Alyanakian MA, Bader-Meunier B, Barnerias C, Bellon N, Belot A, Bodemer C, Briggs TA, Desguerre I, Fremond ML, Hully M, van den Maagdenberg A, Melki I, Meyts I, Musset L, Pelzer N, Quartier P, Terwindt GM, Wardlaw J, Wiseman S, Rieux-Laucat F, Rose Y, Neven B, Hertel C, Hayday A, Albert ML, Rozenberg F, Crow YJ, and Duffy D. 2017. Detection of interferon alpha protein reveals differential levels and cellular sources in disease. J Exp Med 214: 1547–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domeier PP, Chodisetti SB, Schell SL, Kawasawa YI, Fasnacht MJ, Soni C, and Rahman ZSM. 2018. B-Cell-Intrinsic Type 1 Interferon Signaling Is Crucial for Loss of Tolerance and the Development of Autoreactive B Cells. Cell Rep 24: 406–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang JH, Wu Q, Yang P, Li H, Li J, Mountz JD, and Hsu HC. 2011. Type I interferon-dependent CD86(high) marginal zone precursor B cells are potent T cell costimulators in mice. Arthritis Rheum 63: 1054–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baccala R, Gonzalez-Quintial R, Schreiber RD, Lawson BR, Kono DH, and Theofilopoulos AN. 2012. Anti-IFN-alpha/beta receptor antibody treatment ameliorates disease in lupus-predisposed mice. J Immunol 189: 5976–5984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao L, Bird AK, Meednu N, Dauenhauer K, Liesveld J, Anolik J, and Looney RJ. 2017. Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells From Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Have a Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype Mediated by a Mitochondrial Antiviral Signaling Protein-Interferon-beta Feedback Loop. Arthritis Rheumatol 69: 1623–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munroe ME, Vista ES, Merrill JT, Guthridge JM, Roberts VC, and James JA. 2017. Pathways of impending disease flare in African-American systemic lupus erythematosus patients. J Autoimmun 78: 70–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiche L, Jourde-Chiche N, Whalen E, Presnell S, Gersuk V, Dang K, Anguiano E, Quinn C, Burtey S, Berland Y, Kaplanski G, Harle JR, Pascual V, and Chaussabel D. 2014. Modular transcriptional repertoire analyses of adults with systemic lupus erythematosus reveal distinct type I and type II interferon signatures. Arthritis Rheumatol 66: 1583–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko K, Koldobskaya Y, Rosenzweig E, and Niewold TB. 2013. Activation of the Interferon Pathway is Dependent Upon Autoantibodies in African-American SLE Patients, but Not in European-American SLE Patients. Front Immunol 4: 309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benard A, Sakwa I, Schierloh P, Colom A, Mercier I, Tailleux L, Jouneau L, Boudinot P, Al-Saati T, Lang R, Rehwinkel J, Loxton AG, Kaufmann SHE, Anton-Leberre V, O’Garra A, Sasiain MDC, Gicquel B, Fillatreau S, Neyrolles O, and Hudrisier D. 2018. B Cells Producing Type I IFN Modulate Macrophage Polarization in Tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 197: 801–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward JM, Ratliff ML, Dozmorov MG, Wiley G, Guthridge JM, Gaffney PM, James JA, and Webb CF. 2016. Human effector B lymphocytes express ARID3a and secrete interferon alpha. J Autoimmun 75: 130–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hochberg MC 1997. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 40: 1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu HC, Yang P, Wang J, Wu Q, Myers R, Chen J, Yi J, Guentert T, Tousson A, Stanus AL, Le TV, Lorenz RG, Xu H, Kolls JK, Carter RH, Chaplin DD, Williams RW, and Mountz JD. 2008. Interleukin 17-producing T helper cells and interleukin 17 orchestrate autoreactive germinal center development in autoimmune BXD2 mice. Nat Immunol 9: 166–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Fu YX, Wu Q, Zhou Y, Crossman DK, Yang P, Li J, Luo B, Morel LM, Kabarowski JH, Yagita H, Ware CF, Hsu HC, and Mountz JD. 2015. Interferon-induced mechanosensing defects impede apoptotic cell clearance in lupus. J Clin Invest 125: 2877–2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton JA, Wu Q, Yang P, Luo B, Liu S, Hong H, Li J, Walter MR, Fish EN, Hsu HC, and Mountz JD. 2017. Cutting Edge: Endogenous IFN-beta Regulates Survival and Development of Transitional B Cells. J Immunol 199: 2618–2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metsalu T, and Vilo J. 2015. ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res 43: W566–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boiocchi L, Lonardi S, Vermi W, Fisogni S, and Facchetti F. 2013. BDCA-2 (CD303): a highly specific marker for normal and neoplastic plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Blood 122: 296–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El Fiky A, Pioli P, Azam A, Yoo K, Nastiuk KL, and Krolewski JJ. 2008. Nuclear transit of the intracellular domain of the interferon receptor subunit IFNaR2 requires Stat2 and Irf9. Cell Signal 20: 1400–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subramaniam PS, and Johnson HM. 2004. The IFNAR1 subunit of the type I IFN receptor complex contains a functional nuclear localization sequence. FEBS Lett 578: 207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reimer T, Schweizer M, and Jungi TW. 2007. Type I IFN induction in response to Listeria monocytogenes in human macrophages: evidence for a differential activation of IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3). J Immunol 179: 1166–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karpusas M, Nolte M, Benton CB, Meier W, Lipscomb WN, and Goelz S. 1997. The crystal structure of human interferon beta at 2.2-A resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94: 11813–11818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gram AM, Sun C, Landman SL, Oosenbrug T, Koppejan HJ, Kwakkenbos MJ, Hoeben RC, Paludan SR, and Ressing ME. 2017. Human B cells fail to secrete type I interferons upon cytoplasmic DNA exposure. Mol Immunol 91: 225–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green NM, Moody KS, Debatis M, and Marshak-Rothstein A. 2012. Activation of autoreactive B cells by endogenous TLR7 and TLR3 RNA ligands. J Biol Chem 287: 39789–39799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suurmond J, Calise J, Malkiel S, and Diamond B. 2016. DNA-reactive B cells in lupus. Curr Opin Immunol 43: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu Q, Zhao J, Qian X, Wong JL, Kaufman KM, Yu CY, Hwee Siew H, Tan G. Tock Seng Hospital Lupus Study, Mok MY, Harley JB, Guthridge JM, Song YW, Cho SK, Bae SC, Grossman JM, Hahn BH, Arnett FC, Shen N, Tsao BP. 2011. Association of a functional IRF7 variant with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 63: 749–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quach H, Rotival M, Pothlichet J, Loh YE, Dannemann M, Zidane N, Laval G, Patin E, Harmant C, Lopez M, Deschamps M, Naffakh N, Duffy D, Coen A, Leroux-Roels G, Clement F, Boland A, Deleuze JF, Kelso J, Albert ML, and Quintana-Murci L. 2016. Genetic Adaptation and Neandertal Admixture Shaped the Immune System of Human Populations. Cell 167: 643–656 e617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.