Abstract

Proteins that are site-specifically modified with peptides and chemicals can be used as novel therapeutics, imaging tools, diagnostic reagents and materials. However, there are few enzyme-catalyzed methods currently available to selectively conjugate peptides to internal sites within proteins. Here we show that a pilus-specific sortase enzyme from Corynebacterium diphtheriae (CdSrtA) can be used to attach a peptide to a protein via a specific lysine-isopeptide bond. Using rational mutagenesis we created CdSrtA3M, a highly activated cysteine transpeptidase that catalyzes in vitro isopeptide bond formation. CdSrtA3M mediates bioconjugation to a specific lysine residue within a fused domain derived from the corynebacterial SpaA protein. Peptide modification yields greater than >95% can be achieved. We demonstrate that CdSrtA3M can be used in concert with the S. aureus SrtA enzyme, enabling dual, orthogonal protein labeling via lysine-isopeptide and back-bone-peptide bonds.

Enzymatic methods that site-specifically functionalize proteins are of significant interest, as they can enable the creation of novel protein-conjugates for medical and research applications1–5. The Staphylococcus aureus sortase (SaSrtA) has been developed into a powerful protein engineering tool6–10. It catalyzes a transpeptidation reaction that covalently modifies the target protein via a backbone peptide bond, by joining peptide segments that contain a LPXTG ‘sort-tag’ and an N-terminal oligoglycine amine group11,12. Several groups have now optimized this reaction to modify proteins with a range of molecules, including drugs, lipids, sugars, fluorophores, and peptides13–21. While SaSrtA is potent tool, it is almost exclusively used to modify target proteins at their N- or C-termini, while it labels internal lysine side chains as a side reaction with low sequence specificity15,22,23. Here we show that a mutationally activated sortase enzyme from Corynebacterium diphtheriae (CdSrtA) can site-specifically install a peptide on a protein via a lysine-isopeptide bond. CdSrtA and SaSrtA have orthogonal activities, enabling dual peptide-fluorophore labeling of a protein via lysine isopeptide- and backbone peptide-bonds, respectively.

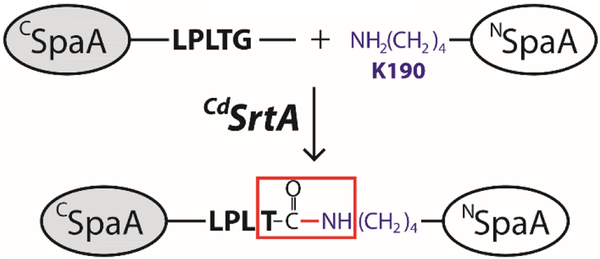

Gram-positive bacteria use specialized sortase enzymes to construct pili: long, thin fibers (0.2–3.0 µm × 2-10 nm) that project from the cell surface to mediate bacterial adherence to host tissues, biofilm formation and host immunity modulation24–26. These structures are distinct from pili produced by Gram-negative bacteria because their protein subunits (called pilins) are crosslinked by lysine-isopeptide bonds that confer enormous tensile strength27,28. Recently, we reconstituted in vitro the assembly reaction that builds the archetypal SpaA-pilus in C. diphtheriae, the causative agent of pharyngeal diphtheria29. CdSrtA functions as a pilin polymerase, performing a repetitive transpeptidation reaction that covalently links adjacent SpaA pilin subunits together via lysine-isopeptide bonds. As shown in scheme 1, CdSrtA crosslinks adjacent SpaA proteins by connecting their N- (NSpaA, residues 30-194) and C-terminal (CSpaA, residues 350-500) domains, which contain a reactive WxxxVxVYPK pilin motif and LPLTG sorting signal sequences, respectively. In the reaction, CdSrtA first cleaves the LPLTG sequence in CSpaA between the threonine and glycine, forming an acyl-enzyme intermediate in which the catalytic C222 residue in CdSrtA is joined to CSpaA’s threonine carbonyl atom.

Scheme 1.

CdSrtA-catalyzed isopeptide bond formation

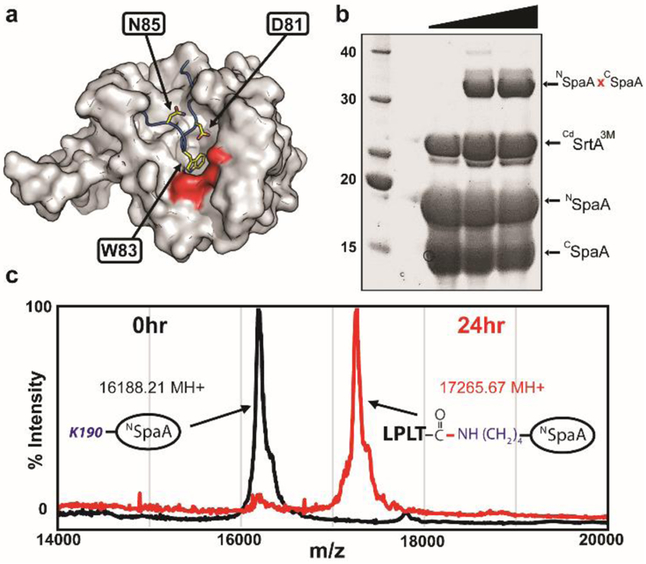

This transient intermediate is then nucleophilically attacked by the reactive K190 within NSpaA’s pilin motif resulting in a T494-K190 isopeptide bond between CSpaA and NSpaA domains within adjacent pilin subunits. Previously, we demonstrated that wild-type CdSrtA is catalytically inactive in vitro due to the presence of an N-terminal polypeptide segment, called a lid, that masks the enzyme’s active site (Fig. 1A)30–34. Moreover, we showed that it was possible to activate the enzyme by introducing D81G and W83G lid mutations and we demonstrated that a soluble catalytic domain harboring these mutations (CdSrtA2M , residues 37-257 of CdSrtA with D81G/W83G mutations) site-specifically ligates the isolated NSpaA and CSpaA domains in vitro29.

Figure 1.

Mutationally activated CdSrtA catalyzes lysine-isopeptide bond formation. (A) The structure of CdSrtAWT harbors an inhibitory “lid” structure (blue). Side chains that were mutated to activate the enzyme are shown as yellow sticks. The surface of the catalytic site is colored red. (B) Protein-protein ligation using the activated CdSrtA3M enzyme. SDS-PAGE analysis of the reaction demonstrating formation of the lysine-isopeptide linked NSpaAxCSpaA product. The reaction (100μM enzyme, 300μM CSpaA and NSpaA) was sampled at 0, 24 and 48 hours. (C) High yield protein-peptide labeling with CdSrtA3M. MALDI-MS data showing that >95% NSpaA is labeled with peptide containing the sort-tag, LPLTGpeptide. MALDI-MS spectra recorded at 0 (black) and 24h (red) are overlaid.

Toward the goal of creating a lysine modifying bioconjugation reagent we improved the ligation activity of CdSrtA2M we defined substrate determinants that are required for catalysis. In addition to the aforementioned D81 and W83 mutations in CdSrtA2M, inspection of the crystal structure reveals three lid residues that may stabilize its positioning over the active site (I79, N85, K89). The ligation activities of triple mutants of CdSrtA containing the D81G and W83G alterations, as well I79R, N85A or K89A substitutions were determined. A D81G/W83G/N85A triple mutant, hereafter called CdSrtA3M, has the highest level of ligation activity (Figs. 1B and S1). After a 24 hour incubation with the isolated NSpaA and CSpaA domains, CdSrtA3M produces 10.6-fold more cross-linked NSpaAxCSpaA product than CdSrtA WT and 35% more product than CdSrtA2M (Fig. S1). The mutations in CdSrtA3M presumably further displace its lid, thereby facilitating enhanced binding of CSpaA’s LPLTG sorting signal and subsequent acylation by C222. This is substantiated by our finding that the CdSrtA3M triple mutant exhibits the highest level of activity in a HPLC-based sorting signal cleavage assay that reports on formation of the acyl-enzyme intermediate (Fig. S1) and previous studies that have shown that alterations in the lid increase C222 reactivity with 4,4’-dithiodipyridine29

NSpaA and CSpaA are joined by CdSrtA3M via their respective pilin motif and LPXTG sorting signal elements. To elucidate determinants required for recognition of the K190 nucleophile, CdSrtA3M was incubated with a peptide containing the pilin motif (DGWLQDVHVYPKHQALS) and either CSpaA or a peptide containing its C-terminal sorting signal (KNAGFELPLTGGSGRI) (Fig. S2). In both instances, no detectable product was observed, indicating that CdSrtA3M requires additional tertiary elements within NSpaA to recognize K190. In contrast, when CdSrtA3M is incubated with NSpaA and the peptide containing the C-terminal sorting signal, >95% of NSpaA is labeled with the peptide (Fig. 1C). Moreover, LC-MS/MS analysis of the crosslinked species reveals that the components are joined via a site-specific isopeptide bond between the threonine within the sorting signal peptide and the Nε amine of K190 in NSpaA (Fig. S3A).

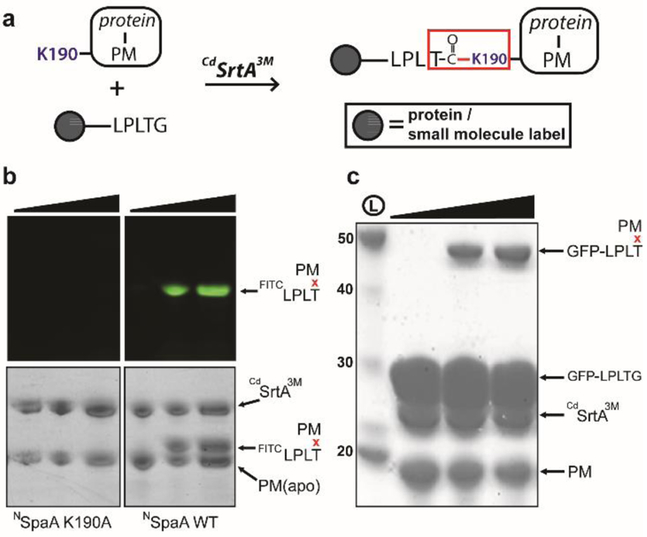

We next demonstrated that CdSrtA3M can be used to label a target protein via an isopeptide bond with either a peptide fluorophore or another protein. In the labeling reaction a target protein is first expressed as a fusion with the NSpaA domain containing the pilin motif (hereafter called PM), and then reacted with a LPLTG-containing biomolecule and CdSrtA3M (Fig. 2A). To demonstrate peptide fluorophore attachment using CdSrtA3M, we incubated the enzyme with NSpaA and a fluorescent FITCKNAGFELPLTGGSGRI peptide (FITCLPLTG). After incubating for either 24 or 48 hours the reaction components were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by either coomassie staining or FITC fluorescence at 530nm. CdSrtA3M labels NSpaA with the fluorescent peptide, yielding a FITCLPLTxNSpaA cross-linked product (Fig. 2B, right). Fluorophore labeling is specific, as NSpaA harboring a K190A mutation is unreactive in control experiments (Fig. 2B, left).

Figure 2.

Labeling proteins via a lysine-isopeptide bond with CdSrtA3M. (A) Schematic showing CdSrtA3M catalyzed labeling of pilin motif (PM) fusion protein with a protein containing the LPLTG sorting signal or a LPLTG peptide with a functional label. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of a fluoropeptide modification reaction containing CdSrtA3M (100μM) and FITCLPLTG (1mM) and either NSpaA (K190A) (lanes 1-3) or NSpaA WT (lanes 4-6) (both 100μM). Top and bottom panels are the same gels visualized by fluorescence or by Coomassie staining, respectively. Reaction progress was measured at 0 (lanes 1,4), 24 (lanes 2,5) and 48hrs (lanes 3,6). (C) Protein-protein ligation with CdSrtA3M. As in panel (B), except reactions contained GFP-LPLTG (300μM) instead of the fluoropeptide. Reactants were visualized with Coomassie staining at 0,24 and 48 hrs (lanes 1-3, respectively).

To demonstrate that CdSrtA3M can also be used to join proteins together via an isopeptide bond, the isolated PM was reacted with green fluorescent protein engineered to contain a C-terminal LPLTGGSGRI sorting signal sequence (GFP-LPLTG). Incubation of these proteins with CdSrtA3M resulted in the appearance a higher molecular weight GFP-LPLTxNSpaA cross-linked product (Fig. 2C, S3B). Notably, the CdSrtA3M protein-protein ligation reaction is versatile, as labeling can be achieved with the PM fused to either the N- or C-terminus of the target protein.

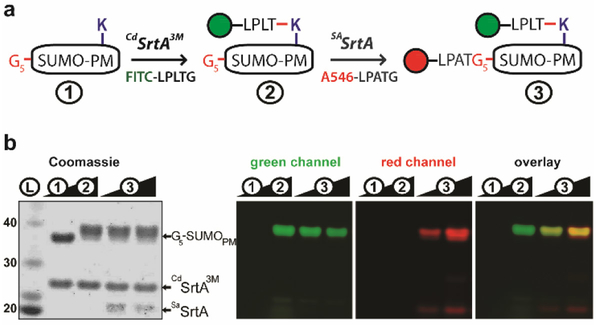

The CdSrtA and SaSrtA enzymes recognize distinct nucleophiles, suggesting that they can be used orthogonally to selectively label a single target protein at different sites. To demonstrate orthogonal labeling we created a fusion protein that contained the Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO) protein harboring a pentaglycine peptide and PM at its N- and C-termini, respectively (G5-SUMOPM). Our dual modification approach involves sequential reaction of the G5-SUMOPM substrate with each sortase and peptide fluorophores containing the cognate sorting signal, as outlined in Fig. 3A. To selectively modify Gly5-SUMOPM (species 1), it was first incubated with CdSrtA3M and FITC-LPLTGpep to create at high yield G5-SUMOPM-FITC (species 2) (Fig. 3B). After removal of excess FITC-LPLTG peptide using a desalting column, the target protein was then labeled at its N-terminus with AlexaFluor546-LPATG using SaSrtA. This was achieved by incubating species 2 with SaSrtA and AlexaFluor546-LPATG to produce the doubly labeled protein (species 3). Separation of the reaction products by SDS-PAGE confirms dual labeling, as the expected fluorescence for each probe is detected at ~33 kD during the procedure (Fig. 3B). In particular, FITC-labeled Gly5-SUMOPM is produced after treatment with CdSrtA3M (488/530nm excitation/emission), and persists after treatment with SaSrtA that catalyzes the second conjugation step with AlexaFluor546 (532/605nm excitation/emission). We note that a similar labeling strategy can presumably be used for fusion proteins that contain the SpaB basal pilin instead of NSpaA, as we have recently shown that CdSrtA3M can also use SpaB as a nucleophile in vitro29. A strength of our approach is the distinct nucleophile and sorting signal substrate specificities of each sortase, which limits cross reactivity. In addition to recognizing distinct nucleophiles, our findings indicate that the sortases have unique sorting signal substrate specificities; CdSrtA3M is unable to hydrolyze or use as a transpeptidation substrate sorting signals containing the sequence LPATG that is readily used by SaSrtA, but instead it is selective for peptides containing LPLTG (Figs. S4, S5). Moreover, the isopeptide bond created by CdSrtA3M is not significantly hydrolyzed by SaSrtA or CdSrtA after 24 hours (Fig. S6). Thus, CdSrtA acts preferentially on its LPLTG sorting signal substrate, preventing potential reversal of LPATG peptides installed by SaSrtA. Similarly, the isopeptide linkages installed by CdSrtA are not a substrate for reversal by SaSrtA or CdSrtA.

Figure 3.

Orthogonal protein labeling using CdSrtA3M and SaSrtA. (A) Sequential reaction scheme used to install fluorogenic peptides on a target protein via peptide- and isopeptide bonds. G5-SUMOPM is a SUMO target protein that is fused to N- and C-terminal nucleophiles, pentaglycine (G5) and the pilin motif (PM), respectively. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of reaction mixture taken at different steps in the procedure. 1) prior to labeling, 2) after labeling with FITCLPLTG using CdSrtA3M and 3) after labeling with A546-LPATG using SaSrtA (0.25/2hr incubations). Panels show as indicated fluorescence gel imaging to detect FITC and A546 fluorophores using 488/530 (green channel) and 532/605mn (red channel) wavelengths for excitation/emission, respectively, and the merged image of the gels demonstrating dual labeling. In the first panel, the same gel was visualized by coomassie staining.

The bioconjugation chemistry catalyzed by CdSrtA3M enables site-specific lysine labeling of a protein, creating an isopeptide linkage that may be less susceptible to proteolysis than conventional peptide bonds. An attractive feature of CdSrtA3M is its high degree of specificity for the ε-amine nucleophile within the pilin motif, which enables selective labeling. Transglutaminases can also modify protein lysine residues, but unlike CdSrtA3M, these enzymes exhibit minimal substrate specifity35,36. Similarly, SaSrtA can modify lysines as a side reaction that occurs with minimal specificity and at low efficiency because the lysine ε-amine is not SaSrtA’s natural substrate15,22,23. Chemical methods that modify amino acid side chains have also been developed, but they often require cysteine or non-natural amino acid incorporation into the protein and in some instances harsh reaction conditions37. The bioconjugation chemistry catalyzed by CdSrtA3M is functionally similar to the non-enzymatic SpyTag/SpyCatcher system38,39, but its enzymatic activity affords greater control making CdSrtA3M an attractive new tool to engineer proteins.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research program under Award Number DE-FC02-02ER63421 and National Institutes of Health Grants AI52217 (R.T.C. and H. T-T.), DE025015 (H. T-T), GM103479 (J.A.L.) and U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research contract DE-AC02-06CH11357 (J.O.). S.A.M. was supported by a Cellular and Molecular Biology Training Grant (Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award GM007185). NMR equipment used in this research was purchased using funds from shared equipment grant NIH S100D016336.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website. This includes PDF file that shows additional data and procedures used in this paper.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Proft T Biotechnol. Lett 2009. 52, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Matsumoto T; Tanaka T; Kondo A Biotechnol. J 2012. 7 1137–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Walper SA; Turner KB; Medintz IL Chit. Opin. Biotechnol 2015. 54, 232–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Krall N; Da Cruz FP; Boutureira O; Bemardes GJL Nat. Chem 2016. 8, 103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Rashidian M; Dozier JK; Distefano MD Bioconjug. Chem 2013. 24, 1277–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Mazmanian SK; Liu G; Ton-That H; Schneewind O Science (80-.). 1999. 285, 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Antos JM; Chew GL; Guimaraes CP; Yoder NC; Grotenbreg GM; Popp MWL; Ploegh HL J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 10800–10801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Williamson DJ; Fascione MA; Webb ME; Turnbull WB Angew. Chemie -Int. Ed 2012, 51, 9377–9380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Levary DA; Parthasarathy R; Boder ET; Ackerman ME PLoS One 2011, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Tsukiji S; Nagamune T ChemBioChem 2009, 10, 787–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Popp MW: Antos JM; Grotenbreg GM; Spooner E; Ploegh HL Nat. Chem. Biol 2007. 3 707–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Mao H; Hart SA; Schink A; Pollok BA J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004. 126, 2670–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Samantaray S; Marathe U; Dasgupta S; Nandicoori VK; Roy RP J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008. 130 2132–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Antos JM.; Miller GM; Grotenbreg GM; Ploegh HL J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008. 150, 16338–16343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Möhlmann S; Mahlert C; Greven S; Scholz P; Harrenga A ChemBioChem 2011. 12, 1774–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wagner K; Kwakkenbos MJ; Claassen YB; Maijoor K; Böhne M; van der Sluijs KF; Witte MD; van Zoelen DJ; Cornelissen LA; Beaumont T; Bakker AQ; Ploegh HL; Spits H Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2014, 111, 16820–16825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Beerli RR; Hell T; Merkel AS; Grawunder U PLoS One 2015, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Amer BR; MacDonald R; Jacobitz AW; Liauw B; Clubb RT J. Biomol. NMR 2016, 64, 197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Dorr BM; Ham HO; An C; Chaikof EL; Liu DR Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2014, 111, 13343–13348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Chen I; Dorr BM; Liu DR Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2011, 108, 11399–11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Antos JM; Truttmann MC; Ploegh HL Recent Advances in Sortase-Catalyzed Ligation Methodology. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2016, pp 111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Dasgupta S; Samantaray S; Sahal D; Roy RP J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 23996–24006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Bellucci JJ; Bhattacharyya J; Chilkoti A Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2015, 54, 441–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Danne C; Dramsi S Res. Microbiol 2012, 163, 645–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Spirig T; Weiner EM; Clubb RT Mol. Microbiol 2011, 82, 1044–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ton-That H; Schneewind O Trends Microbiol. 2004, 12, 228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Echelman DJ; Alegre-Cebollada J; Badilla CL; Chang C; Ton-That H; Fernández JM Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2016, 113, 2490–2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Yeates TO; Clubb RT Biochemistry: How Some Pili Pull. Science. 2007, pp 1558–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Chang C; Amer BR; Osipiuk J; McConnell SA; Huang I-H; Hsieh V; Fu J; Nguyen HH; Muroski J; Flores E; Ogorzalek Loo RR; Loo JA; Putkey JA; Joachimiak A; Das A; Clubb RT; Ton-That H Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2018, 115, E5477–E5486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Jacobitz AW; Naziga EB; Yi SW; McConnell SA; Peterson R; Jung ME; Clubb RT; Wereszczynski JJ Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 8302–8312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Manzano C; Izoré T; Job V; Di Guilmi AM; Dessen A Biochemistry 2009, 48, 10549–10557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Cozzi R; Zerbini F; Assfalg M; D’Onofrio M; Biagini M; Martinelli M; Nuccitelli A; Norais N; Telford JL; Maione D; Rinaudo CD FASEB J 2013, 27, 3144–3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Persson K Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr 2011, 67, 212–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Manzano C; Contreras-Martel C; El Mortaji L; Izoré T; Fenel D; Vernet T; Schoehn G; Di Guilmi AM; Dessen A Structure 2008, 16, 1838–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Yokoyama K; Nio N; Kikuchi Y Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2004, 64, 447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Fontana A; Spolaore B; Mero A; Veronese FM Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2008, 60, 13–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Spicer CD; Davis BG Nat. Commun 2014, 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Reddington SC; Howarth M Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2015, 29, 94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Zakeri B; Fierer JO; Celik E; Chittock EC; Schwarz-Linek U; Moy VT; Howarth M Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2012, 109, E690–E697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.