Abstract

The basolateral membrane anion conductance of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is a key component of the transepithelial Cl− transport pathway. Although multiple Cl− channels have been found to be expressed in the RPE, the components of the resting Cl− conductance have not been identified. In this study, we used the patch-clamp method to characterize the ion selectivity of the anion conductance in isolated mouse RPE cells and in excised patches of RPE basolateral and apical membranes. Relative permeabilities (PA/PCl) calculated from reversal potentials measured in intact cells under bi-ionic conditions were as follows: SCN− >> ClO4− > > I− > Br− > Cl− >> gluconate. Relative conductances (GA/GCl) followed a similar trend of SCN− >> ClO4− > > I− > Br− ≈Cl− >> gluconate. Whole cell currents were highly time-dependent in 10 mM external SCN−, reflecting collapse of the electrochemical potential gradient due to SCN− accumulation or depletion intracellularly. When the membrane potential was held at −120 mV to minimize SCN− accumulation in cells exposed to 10 mM SCN−, the instantaneous current reversed at −90 mV, revealing that PSCN/PCl is approximately 500. Macroscopic current recordings from outside-out patches demonstrated that both the basolateral and apical membranes exhibit SCN− conductances, with the basolateral membrane having a larger SCN− current density and higher relative permeability for SCN−. Our results suggest that the RPE basolateral and apical membranes contain previously unappreciated anion channels or electrogenic transporters that may mediate the transmembrane fluxes of SCN− and Cl−.

Keywords: anion conductance, anion permeability, RPE

INTRODUCTION

The health and integrity of mammalian rod and cone photoreceptors require strict regulation of the ionic composition and volume of the subretinal fluid enveloping the photoreceptor outer segments. This homeostasis is achieved in large part by the transport of solutes and water by the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), a polarized monolayer of cells whose apical membrane faces the photoreceptor outer segments and basolateral membrane faces the choroidal blood supply. Cl− channels in the RPE basolateral membrane operate in conjunction with the Na,K,2Cl cotransporter in the apical membrane to generate transepithelial Cl− transport, a major driving force for fluid absorption (22). Studies on intact RPE-choroid preparations have demonstrated that the passive properties of the basolateral membrane are dominated by a large Cl− conductance (22), whose magnitude is augmented by increases in intracellular Ca2+ (40) and/or cyclic AMP (41).

Over the past two decades, multiple Cl− channels have been shown to be expressed in the RPE. Substantial evidence has accrued suggesting that the Ca2+-dependent Cl conductance has contributions from BEST1 (31), TMEM16A (10), and/or TMEM16B (23) and that CFTR (5) likely underlies the cyclic AMP-dependent Cl− conductance. On the other hand, the basis for the steady-state or resting Cl− conductance of the RPE is uncertain. It has been suggested that ClC-2 contributes to the RPE basolateral membrane Cl− conductance in mice (7), but the data supporting this idea came from transepithelial measurements and are largely indirect. A patch-clamp study on RPE cells isolated from Xenopus laevis documented Cl− currents with properties consistent with ClC-2, namely slow activation, strong inward rectification, Zn2+-induced block, and pH sensitivity (17). However, currents resembling ClC-2 were not detected in numerous studies on RPE cells from other amphibian species (18) and from mammals, including rat (50), human (19), cow (49), and mouse (32). Instead, these studies consistently documented a Cl− current that was time-independent and mildly inwardly rectifying. Thus, in mammalian RPE, there seems to be little or no contribution of ClC-2 to the resting basolateral membrane Cl− conductance and the underlying Cl− channel(s) remain to be determined.

Anion channels vary in their ability to discriminate among different ions and measurements of anion selectivity sequences for relative permeability (related to how readily an ion enters the channel pore) and relative conductance (inversely related to how tightly an ion binds within the channel pore) can aid in the identification of anion channel(s) that compose the Cl− conductance of a cell. However, at present there is scant information about the ion selectivity of the anion conductance of the RPE basolateral membrane.

In the quest to better understand the basis for the resting Cl− conductance of the RPE basolateral membrane, we carried out a comprehensive characterization of its anion selectivity. To this end, we used the patch-clamp technique to record currents from intact mouse RPE cells as well as from excised basolateral and apical membrane patches in the presence of Cl− and various other anions. Unexpectedly, we found that the anion conductance of the RPE basolateral membrane has a remarkably high permeability and conductance for thiocyanate (SCN−), indicative of an anion channel or electrogenic transporter that has not been appreciated previously. In addition, we found that the apical membrane contains an SCN− conductance as well. These membrane mechanisms may function in active Cl− transport across the RPE and may also participate in the transport of SCN−.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RPE cell isolation.

All procedures involving mice received Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval and were conducted in compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. C57BL/6 (B6) mice of both sexes and aged 4 to 36 wk were euthanized by CO2 inhalation before enucleation. Enucleated eyes were hemisected posteriorly to the ora serrata, and the anterior segment and lens were removed. After incubating eyecups with 800 units/ml hyaluronidase type 1-S for 15 min at room temperature, the neural retina was slowly peeled from the RPE and cut at the optic nerve head. Eyecups were then incubated in a 0 Na+, Ca2+-, Mg2+-free solution [135 mM N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG)-Cl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, 2 mM EGTA-KOH, titrated to pH 7.4 with NMDG-free base] containing activated papain (3.5 units/ml, Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ) and DNase I (30 units/ml) for 60 min at 37°C, washed in L-15 medium containing 1% bovine serum albumin, and then gently triturated. Isolated RPE cells were stored in L-15 medium containing 0.5 mM taurine and 1 mM reduced glutathione at 4°C and used within 8 h. All solutions used for the isolation and storage of RPE cells were bubbled with 90% N2-10% O2. This measure improved cell quality significantly. All chemicals except for papain were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Electrophysiology.

Enzymatically dissociated mouse RPE cells were allowed to attach to the glass coverslip bottom of a recording chamber and were constantly superfused with bath solutions delivered by gravity feed. The amplifier’s circuit ground was connected to an Ag/AgCl electrode separated from the bath by a 3 M KCl/Agar bridge. All experiments were performed at room temperature. Macroscopic membrane currents were recorded using the whole cell or outside-out patch configuration of the patch-clamp technique. Data from outside-out patches were rejected if one or more of the following criteria were met in the presence of 140 mM external Cl−: the normalized resistance of the patch was <2 GΩ·pF, the patch contained large single-channel events, currents were unstable, or the patch had a large offset of current or voltage. Patch pipettes were pulled from 1.65 mm OD glass capillary tubing (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) using a multistage programmable microelectrode puller (model P-97, Sutter Instruments, San Rafael, CA) and had an impedance of 2–5 MΩ after fire polishing. Series resistance (Rs) was normally less than 10 MΩ and was uncompensated except in whole cell experiments involving the replacement of external Cl− with SCN− or ClO4−, where Rs compensation was 50%–80%. Signals were amplified with an Axopatch 200 or Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Reversal potential (Erev), slope conductance, and chord conductance (Gchord) were determined by linear regression analysis of current-voltage (I-V) plots. In most experiments, currents were evoked from a holding potential (HP) of −60 mV by either 1-s voltage ramps from −120 to +60 mV or by a series of 1-s voltage steps in the same voltage range in 10-mV increments, with an intersweep interval of at least 8 s. Outward slope conductance was measured as the slope of the I-V curve in the voltage range, +40 to +60 mV, and chord conductance was calculated by the relation Gchord = I/(Vm − Erev), where Vm is membrane voltage. Relative anion conductances were calculated from chord conductance values determined at voltages 10 to 20 mV positive of Erev.

Junction potentials arising at the pipette tip and the Agar-bridge of the reference electrode were calculated using the Junction Potential Calculator function in pClamp 9 (Molecular Devices). In whole cell voltage-clamp experiments, current flow across Rs caused an additional voltage error. The errors in Vm were corrected by the formula

| (1) |

where Vm, uncorr is the apparent Vm, Rs,correct is the series resistance compensation, and jp is the correction for junction potentials. These voltage error corrections are shown in I-V plots, except where noted. For simplicity, command potentials are given for voltage-clamp protocols.

Solutions.

The pipette solution used in most experiments was an NMDG-Cl based solution containing (in mM) 135 NMDG-Cl, 10 HEPES, 5.5 EGTA-KOH, 0.5 CaCl2, and 4 MgCl2 (pH 7.2); in some experiments, the solution contained EGTA-NMDG and 1 mM MgCl2. For experiments testing the effect of low intracellular Cl−, 135 NMDG-gluconate replaced NMDG-Cl. The free Ca2+ concentration in all pipette solutions was calculated to be ~30 nM (maxchelator.stanford.edu). Bath solutions contained (in mM) 140 CA, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, 1.8 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2 (pH 7.4), where C represents Na+ or NMDG+ and A represents Cl−, SCN−, ClO4−, , Br−, I−, gluconate, isethionate, or methanesulfonate (pH 7.4).

Data analysis.

Data acquisition, analysis, and curve fitting were carried out using pClamp 9 (Molecular Devices) or SigmaPlot 10 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). For clarity of presentation, capacitative transients in some figures are masked.

Reversal potentials (Erev) from I–V plots were used to calculate relative permeability ratios (PA/PCl) according to the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation

| (2) |

where [A]o and [Cl]o are the extracellular concentrations of the test anion and Cl−, respectively, [Cl]I is the concentration of Cl− in the pipette, z = −1, and F, R, and T have their normal thermodynamic meanings.

The dose-dependent block of the SCN− current by Zn2+ in excised basolateral membrane patches was fitted to the first order equation of the form

| (3) |

where IC50 is the half-maximal concentration for block, Imin is the fraction of current that is insensitive to block by Zn2+, and IZn2+ and Icontrol are the currents in the presence and absence of Zn2+, respectively.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed using Excel (Microsoft) and SPSS (IBM). The statistical significance of differences between groups of three or more was calculated by ANOVA and the two-tailed t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test was used for comparisons between two groups. Probability values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Whole Cell Experiments

Enzymatic dissociation of mouse RPE yielded a population of polarized cells exhibiting a “figure-eight” morphology, similar to what has been reported elsewhere (32). These cells were characterized by a basolateral pole with a smooth-appearing membrane and a narrowing of the cell body separating an apical pole containing microvilli 2 to 5 µm in length. We used the whole cell recording configuration of the patch-clamp technique to characterize the anion selectivity of the Cl− conductance in intact cells. For the 255 cells used in this study, the membrane capacitance averaged 122.8 ± 3.1 pF. To eliminate K+ currents, which are the predominant ionic currents in RPE cells under physiological conditions (20), we used a pipette solution containing 140 mM NMDG-Cl and 11 mM or 0 K+ (see materials and methods) together with a K+-free bath solution. The elimination of K+ currents by use of these solutions was confirmed in experiments showing that the application of a cocktail of K+ channel blockers (20 mM TEACl, 5 mM BaCl2, and 10 µM linopirdine) had no effect on whole cell currents (n = 3; data not shown). Currents were somewhat larger at negative voltages than at positive voltages (Fig. 1A). Inward Na+ current contributed a small fraction to this inward rectification, as replacement of external Na+ with NMDG+ reduced the amplitude of inward current at −100 mV by 13.6 ± 4.3% (mean ± SE, n = 16; data not shown). Ca2+ and Mg2+ can be eliminated as possible charge carriers because replacement of 140 mM external NMDG+ with 70 mM Ca2+ or 70 mM Mg2+ had no significant effect on inward currents. Thus, Cl− currents appear to be the predominant ionic current under these recording conditions.

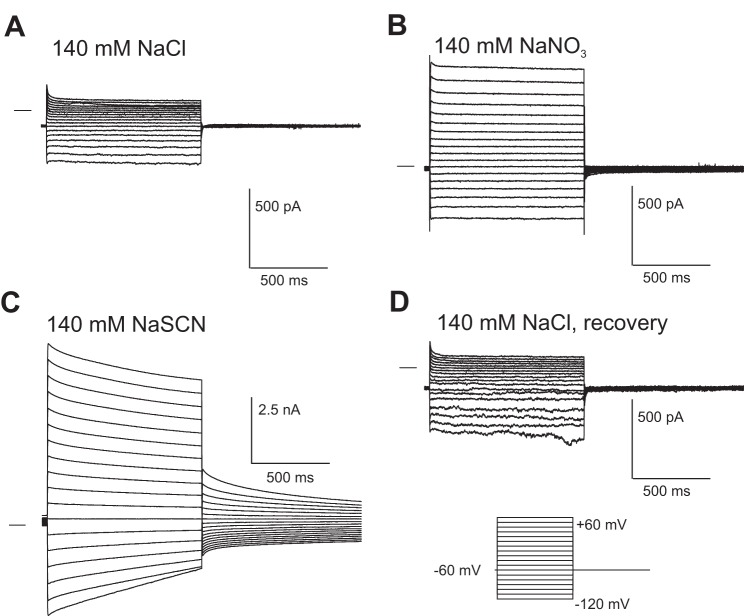

Fig. 1.

SCN− currents in isolated mouse retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells. Representative whole cell currents were recorded from the same RPE cell. The cell was dialyzed with a N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG)-Cl based K+-free internal solution and superfused with a solution containing 140 mM NaCl (A), 140mM NaNO3 (B), or 140 mM NaSCN (C). The effect of SCN− was completely reversible (D). The family of currents in D was obtained after 10 min of perfusion with 140 mM NaCl solution to ensure the complete removal of SCN−. Currents were elicited using a voltage step protocol consisting of 1-s steps, from −120 to +60 mV in intervals of 10 mV, from a holding potential of −60 mV. Horizontal lines to the left of the current traces indicate the zero-current level.

Anion selectivity under bi-ionic conditions.

To characterize the anion selectivity of the RPE cell membrane, we recorded whole cell currents before and after equimolar replacement of 140 mM NaCl in the bath solution with Na+ salts of various other anions. Currents were evoked from a holding potential of −60 mV by voltage steps from −120 mV to +60 mV in 10-mV increments. Replacement of external Cl− with produced an ~7-fold increase in outward current at +60 mV (Fig. 1B) and a negative shift in reversal potential (Erev) from +0.5 to −51.0 mV, indicating a higher permeability for than for Cl−. In contrast, when Cl− was replaced with SCN−, whole cell current amplitude increased dramatically, with outward current increasing ~80-fold and inward current increasing ~10-fold (Fig. 1C). Coincidentally, Erev shifted negatively to −62.2 mV. Currents in cells exposed to SCN− exhibited time-dependent decay during both depolarizing and hyperpolarizing voltage steps and were followed by tail currents of opposite polarity at the offset of the voltage step. The effects of SCN− were reversible (Fig. 1D), with an average half-time for recovery of 70.7 ± 21.6 s (± SE, n = 7, data not shown).

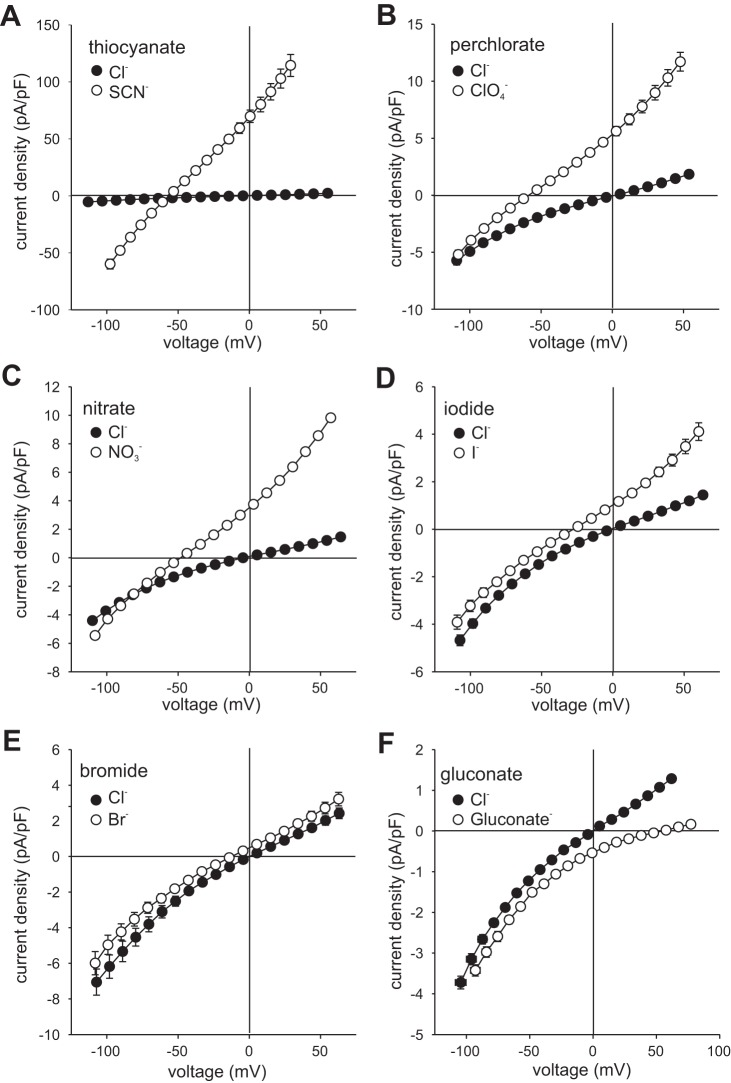

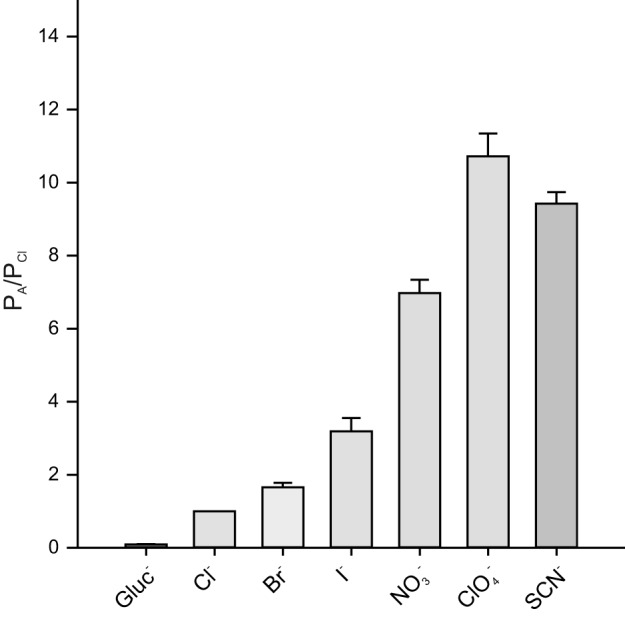

We further explored the anion selectivity of RPE cells by measuring current-voltage (I-V) relationships in the presence of various test anions. Figure 2 summarizes the results of paired experiments from multiple cells and shows I-V relationships of currents generated from a holding potential of −60 mV by voltage ramps in the presence of 140 mM external Cl− and (Fig. 2C), Br− (Fig. 2D), I− (Fig. 2E), or gluconate (Fig. 2F) or instantaneous currents produced by voltage steps in 140 mM external Cl− and SCN− (Fig. 2A) or ClO4− (Fig. 2B). Replacement of external Cl− with or ClO4− significantly increased the amplitude of outward current and shifted Erev to more negative potentials, with the effects of ClO4− being somewhat greater. External SCN− caused a comparable negative shift in Erev and had striking effects on current amplitude, producing robust outward currents as well as substantial inward currents. In contrast, Br− and I− produced relatively small increases in outward current and small hyperpolarizing shifts in Erev, whereas gluconate virtually eliminated outward current and produced a large positive shift in Erev. Figure 3 shows plots of chord conductance as a function of voltage for these same experiments and indicates a relative anion conductance (GA/GCl) sequence of SCN− (40.3 ± 6.6) >> (3.0 ± 0.7) ≈ClO4− (2.5 ± 0.2) > I− (2.0 ± 0.8) > Br− (1.4 ± 0.5) ≈Cl− (1) >> gluconate (0.3 ± 0.1), with the relative conductance in SCN− being an order of magnitude greater than those of the other anions tested. Apparent relative permeabilities (PA/PCl), calculated by the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation (Eq. 2) from Erev values determined in the experiments in Fig. 2, are shown in Fig. 4 and suggest a PA/PCl sequence of SCN− (9.5 ± 0.3) ≈ ClO4− (10.7 ± 0.7) > (7.0 ± 0.4) > I− (3.2 ± 0.4) > Br− (1.7 ± 0.1) > Cl− (1) >> gluconate (0.09 ± 0.01). Thus, whereas the relative conductance of RPE cells for SCN− is markedly higher than it is for other anions, the apparent relative permeability for SCN− measured under these experimental conditions is of similar magnitude to those for ClO4− and .

Fig. 2.

Effect of anion substitutions on the whole cell current-voltage (I-V) relationship. Cells were dialyzed with NMDG-Cl-based internal solution and currents were recorded before and after replacement of 140 mM external NaCl with NaSCN (A, n = 8) 140 mM NaClO4 (B, n = 9), NaNO3 (C, n = 20), NaI (D, n = 8), NaBr (E, n = 8), or Na-gluconate (F, n = 9). Currents in SCN− and ClO4− are instantaneous currents evoked by voltage steps; currents in all other anions were generated by 1-s voltage ramps from −120 to +60 mV. Holding potential was −60 mV. Mean reversal potential (Erev) values in the presence of Cl− and substitute anions are as follows: SCN−, −56.3 ± 0.8 mV (± SE, n = 8); ClO4−, −59.3 ± 1.6 mV (n = 10); , −48.0 ± 1.5 mV (n = 21); I−, −27.9 ± 3.3 mV (n = 8); Br−, −12.1 ± 1.9 mV (n = 9); Cl−, −0.9 ± 0.7 mV (n = 64); gluconate, +54.0 ± 2.3 mV (n = 9). Symbols represent mean current density, and bidirectional error bars represent SE; where not visible, the error bars are smaller than the symbols. Voltages are corrected for liquid junction potentials and the voltage drop across the series resistance.

Fig. 3.

Effect of anion substitutions on the chord conductance-voltage (G–V) relationship. Chord conductances in the presence of 140 mM Cl− and 140 mM anion substitutes were calculated as a function voltage on a cell-to-cell basis from the data in Fig. 2. A: SCN− (n = 8). B: ClO4− (n = 9). C: (n = 20). D: I− (n = 8). E: Br− (n = 8). F: gluconate (n = 9).

Fig. 4.

Apparent relative permeabilities under bi-ionic conditions. Permeability ratios (PA/PCl) were calculated from reversal potentials (Erev) obtained from the experiments in Fig. 2 using the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation (Eq. 2). Vertical bars represent means and error bars represent SE. Relative permeabilities for SCN− and ClO4− were not significantly different; for all other comparisons, P < 0.001 (two-tailed t-test). Gluconate (Gluc−), n = 9; Br−, n = 8; I−, n = 8; , n = 20; ClO4−, n = 9; SCN−, n = 8.

An underlying assumption in our calculation of PSCN/PCl from Erev is that the intracellular anion composition is identical to that of the pipette solution (i.e., 144 mM Cl− and 0 SCN−). However, if SCN− were to accumulate intracellularly as a result of its influx from the bath, then the true value of PSCN/PCl could be considerably larger than that calculated. Indeed, the production of large inward currents by hyperpolarizing voltage steps is consistent with the efflux of SCN− that had accumulated within the cell at a holding potential (HP) of −60 mV. If this explanation were correct, then changing the HP to a more negative voltage should reduce the extent of intracellular SCN− accumulation and result in a more negative Erev value.

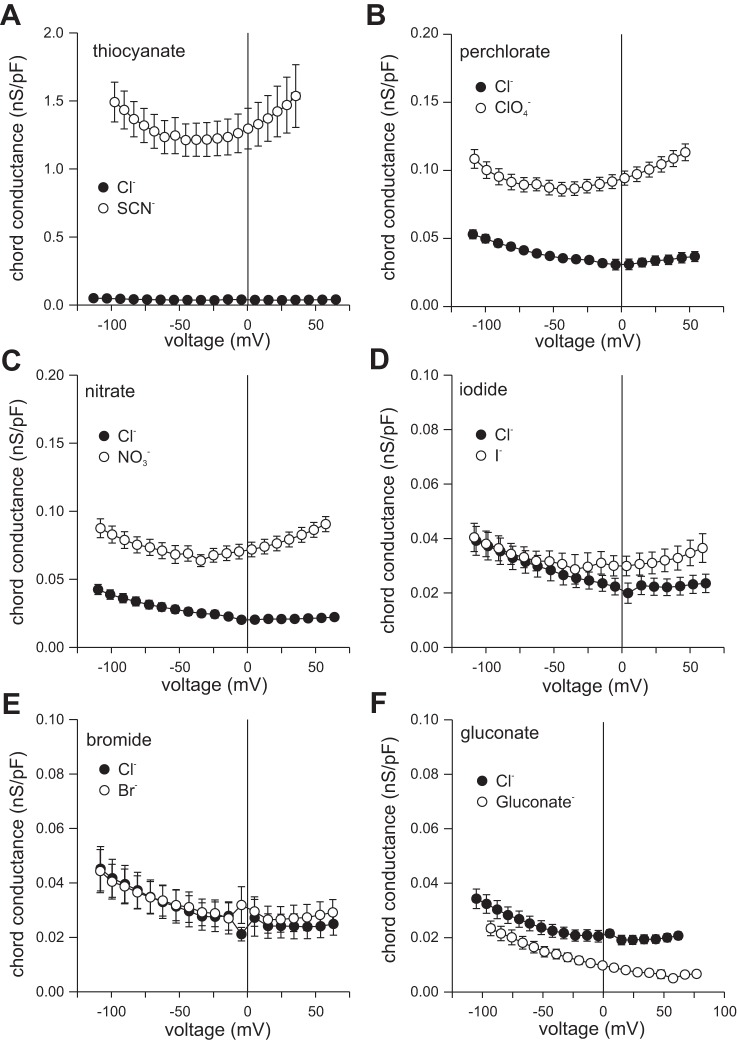

This prediction was confirmed in the experiment depicted in Fig. 5, in which whole cell currents were evoked in an RPE cell from a HP of −120 mV by voltage steps in the range −180 mV to +40 mV. Similar to what was observed at an HP of −60 mV (Fig. 1A), currents in 140 mM external Cl− were time-independent at all voltages tested and showed mild inward rectification (Fig. 5, A, C, and D). Replacement of Cl− with SCN− produced large inward and outward currents that exhibited prominent time-dependent decay (Fig. 5B). To provide ample time for the intracellular SCN− concentration return to steady state, the voltage was held at −120 mV for 34 s between voltage steps. The I-V relationship of the instantaneous current revealed an Erev of −107 mV (Fig. 5C), which is ~50 mV more negative than that obtained at HP = −60 mV (−56.3 ± 0.8, n = 8). The combination of long exposure to 140 mM SCN− (13.5 min) and voltage clamping to large negative potentials usually led to membrane deterioration and experimental failure, but nonetheless, we were successful in obtaining results in 4 other cells. For the 5 cells, Erev averaged −101.7 ± 1.9 mV (mean ± SE) and the corresponding PSCN/PCl value averaged 56.7 ± 4.3. Thus, setting the HP at −120 mV resulted in an apparent PSCN/PCl that was almost 6-fold higher than that obtained at an HP of −60 mV. The upper bound of the intracellular concentration of SCN− at a given HP can be estimated from Erev using the Nernst equation, which gives the concentration reached at electrochemical equilibrium:

Fig. 5.

Reversal potential (Erev) becomes more negative when the membrane potential (Vm) is held at a more negative voltage. Families of whole cell currents evoked in a retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cell from a holding potential of −120 mV in the presence of 140 mM external Cl− (A) or 140 mM external SCN− (B). The voltage-clamp protocol and scale for both sets of current are shown at the bottom of A and the zero-current level is shown by the horizontal lines to the left of currents. The effective series resistance (Rs) after series resistance compensation was 4 MΩ. Current-voltage (I-V) plots of the instantaneous current (C) or steady-state current (D) obtained from the same data as that shown in A and B in the presence of Cl− (open circles) or SCN− (closed circles). Voltages in C and D were corrected for liquid junction potentials and the voltage drop across the series resistance.

| (4) |

By this approach, we calculate that at HP = −60 mV, where Erev averaged −56.3 ± 0.8 mV, [SCN−]in ≤ 15.3 mM and that at HP = −120 mV, [SCN−]in ≤ 2.7 mM. Given the probable intracellular presence of SCN− at HP = −120 mV, the PSCN/PCl value of 57 calculated from Erev measured under this condition should be considered a lower limit.

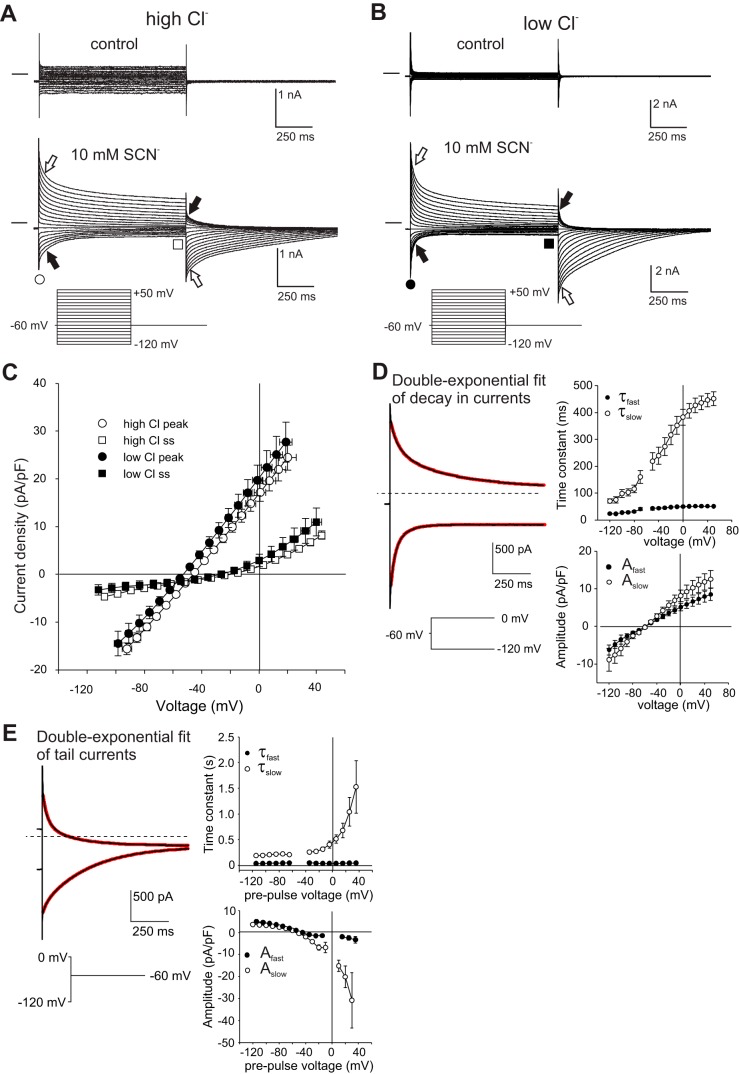

Large transient currents are elicited in the presence of 10 mM external SCN−.

To reduce intracellular SCN− accumulation and improve voltage clamping, we performed subsequent whole cell experiments in which a smaller fraction of external Cl− was replaced with SCN−. Figure 6A shows that the replacement of 10 mM of the external Cl− with SCN− caused whole cell currents to increase in amplitude and become time-dependent. As in the previous experiments, the patch-pipette solution contained 144 mM Cl−, and the membrane was held at −60 mV between voltage steps. In the presence of 10 mM SCN− and 135.6 mM Cl− in the bath, membrane depolarization to +50 mV evoked a large transient outward current, which was followed by a prominent inward tail current when Vm was repolarized to −60 mV (open block arrows). Likewise, membrane hyperpolarization to −120 mV produced a transient inward current, which was followed by an outward tail current when Vm was returned to −60 mV (closed block arrows). Figure 6C summarizes the results of similar experiments on 11 cells and compares the I-V relationships for the instantaneous current (open circles) and the steady-state current (open squares) measured at the end of the 1-s voltage step. The I-V curve of the instantaneous current was essentially linear and had an Erev of −45.8 ± 1.1 mV (n = 11; mean ± SE), whereas that of the steady-state current had a smaller slope conductance, was outwardly rectifying, and had an Erev of −19.4 ± 1.9 mV.

Fig. 6.

Whole cell currents in 10 mM external SCN− are time-dependent and independent of external and internal Cl− concentrations. A: representative whole cell recording from a retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cell superfused with a solution containing 140 mM NaCl (top) or 130 mM NaCl and 10 mM NaSCN (bottom). The cell was dialyzed with NMDG-Cl-based internal solution. Voltage-clamp protocol was as indicated. Currents evoked by voltage steps to +50 and −120 mV and their associated tail currents are marked by open arrows and closed arrows, respectively. Note the association of transient currents with tail currents of opposite polarity. Instantaneous currents were measured 10 ms after the onset of voltage steps (open circle) and steady-state currents were measured 5 ms before their termination (open square). B: representative whole cell recording from an RPE cell superfused with a solution containing 140 mM Na-methanesulfonate and 5.6 mM NaCl (top) or 10 mM NaSCN, 130 mM Na-methanesulfonate, and 5.6 mM NaCl (bottom). The cell was dialyzed with NMDG-gluconate-based pipette solution containing 5.0 mM Cl−. Currents evoked by voltage steps to +50 and −120 mV are marked by open arrows and closed arrows, respectively. C: voltage dependence of instantaneous (circles) and steady-state (squares) currents elicited from a holding potential of −60 mV in 10 mM external NaSCN under conditions of high (open symbols) and low (closed symbols) external and internal Cl− concentrations. Solutions used are the same as those indicated for A and B except that in some low Cl− experiments isethionate was used instead of methanesulfonate. Data shown represent means ± SE, n = 10–13. There was no significant difference between peak or steady-state currents obtained in high and low Cl− at any of the voltages. D: kinetics of time-dependent decay in currents obtained in 10 mM external SCN−. Left: time course of current decay during voltage steps from a holding potential of −60 to 0 mV (top) or −120 mV (bottom), fitted by a double-exponential function (red traces). The interrupted line marks the zero-current level. Right: voltage dependence of the time constant (top) and amplitude (bottom) of the fast (τfast, Afast) and slow (τslow, Aslow) components obtained from the double-exponential fit. Bath and pipette solutions contained high Cl− concentrations. Data shown represent means ± SE, n = 5 – 7. E: kinetics of time-dependent decay in tail currents. Left: time course of tail current decay upon return to the holding potential of −60 mV from voltage steps to 0 mV (top) or −120 mV (bottom), fitted by a double-exponential function (red traces). The interrupted line marks the zero-current level. Right: voltage dependence of the time constant (top) and amplitude (bottom) of the fast and slow components. Data shown represent means ± SE, n = 5–7.

To help establish the identity of the transient currents observed in 10 mM external SCN−, we performed similar experiments in which most of the Cl− in the pipette and bath solutions was replaced by large impermeant anions. Figure 6B shows the results of a representative experiment in which the pipette solution contained 135 mM gluconate and 5 mM Cl−, and the bath solution contained 140 mM methanesulfonate and 5.6 mM Cl−. As was observed under conditions of high symmetrical Cl−, the replacement of 10 mM of the methanesulfonate with SCN− produced large transient inward and outward currents. Figure 6C summarizes the instantaneous and steady-state I-V relationships for this and seven other cells recorded with gluconate in the pipette and methanesulfonate or isethionate in the bath. The I-V curve of the instantaneous current (closed circles) was essentially linear and had an Erev of −52.5 ± 1.7 mV (n = 8; mean ± SE), which is somewhat more hyperpolarized than that observed in high symmetrical Cl− (P < 0.002, two-tailed t-test), whereas the I-V curve of the steady-state current (closed squares) had a smaller slope conductance, was outwardly rectifying, and had an Erev of −20.9 ± 10.1 mV (not significantly different from symmetrical high Cl−). The fact that transient inward and outward currents persisted after external and internal Cl− concentrations were decreased roughly 25-fold indicates that they reflect the efflux and influx of SCN−, respectively, rather than fluxes of Cl−.

We found that the decay in inward and outward currents could be adequately fitted by a double exponential function (Fig. 6D, left), yielding fast and slow time constants as well as the amplitudes of the two components. As summarized in Fig. 6D, both time constants increased as the voltage was made more positive (right, top) and, across the voltages tested, both components contributed about equally to the amplitude of the decay in current (right, bottom). Similarly, the time course of tail currents could be well fitted by a double-exponential function. As summarized in Fig. 6E, the fast time constant was essentially constant across the voltages tested, but the slow time constant increased with depolarization, as did the relative contribution of the slow component to the tail current amplitude.

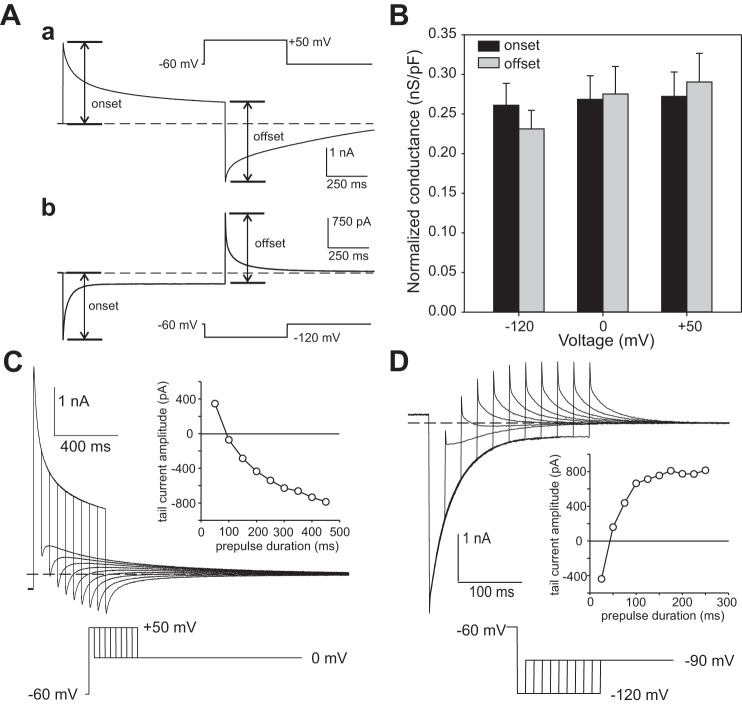

Time-dependent decay in current is due to intracellular SCN− accumulation or depletion and not ion channel gating.

In principle, a time-dependent decay of current can result from a decrease in membrane conductance because of the voltage-dependent inactivation or deactivation of the underlying channel(s). However, a decrease in conductance cannot explain the decay in outward and inward currents in RPE cells exposed to 10 mM external SCN−. As shown in Fig. 7A, the instantaneous current changes at the onset and offset of voltage steps from a holding potential of −60 to +50 mV (Fig. 7Aa) or −120 mV (Fig. 7Ab) were roughly equal in amplitude but of opposite polarity. We calculated membrane conductance in these experiments by dividing the instantaneous change in current by the change in voltage and found that it was 24.1 nS and 24.5 nS at the onset and offset of the voltage step to +50 mV, respectively and 24.5 nS and 24.3 nS at the onset and offset of the voltage step to −120 mV. Similar results were obtained in a total of 8 cells and are summarized in Fig. 7B, which compares conductances measured at the onset and offset of voltage steps from a holding potential of −60 or −50 mV to test potentials of −120 mV, 0 mV, or +50 mV. As there was no significant difference between conductances measured at the onset and offset of any of the three voltage steps, we conclude that voltage-dependent gating is not the mechanism underlying the time-dependent decay in current in RPE cells recorded with 10 mM SCN− in the bath.

Fig. 7.

Time-dependent currents in 10 mM external SCN− reflect intracellular SCN− accumulation or depletion and not voltage-dependent gating. A: representative traces illustrating the amplitudes of instantaneous currents at the onset and offset of voltage steps from −60 to +50 mV (a) or −120 mV (b). The near-equal amplitudes of the currents at the voltage step onset and offset indicates that membrane conductance remained unchanged during the time-dependent decay in current. Note that the transient currents and tail currents are of opposite polarity, consistent with a change in reversal potential (Erev). The interrupted horizontal line marks the steady-state current at −60 mV. The bath and pipette solutions contained high Cl−. B: membrane conductance measured at the onset and offset of voltage steps from a holding potential of −60 to −120, 0, or +50 mV (n = 8). Conductance was calculated by dividing the change in current by the change in voltage, corrected for the voltage drop across series resistance (Rs). The bath and pipette solutions contained high Cl−. n = 8. C: representative tail currents in 10 mM external SCN− elicited by stepping the voltage to 0 mV after depolarizing the membrane voltage to +50 mV for different durations from a holding potential of −60 mV. The bath and pipette solutions contained high Cl−. The interrupted line marks the steady-state current at 0 mV. Inset: tail current amplitude (instantaneous current – steady-state current) plotted as a function of the duration of the voltage step to +50 mV. Tail currents were outward for depolarizing voltage steps of short duration and inward for voltage steps of longer duration. The reversal in tail current polarity indicates that the time-dependent decay in outward current is associated with a change in ESCN. D: representative tail currents in 10 mM external SCN− elicited by stepping the voltage to −90 mV after hyperpolarizing the membrane voltage to −120 mV for different durations from a holding potential of −60 mV. The bath and pipette solutions contained high Cl−. The interrupted line marks the steady-state current at −90 mV. Inset: tail current amplitude (instantaneous current – steady-state current) plotted as a function of the duration of the voltage step to −120 mV. Tail currents were inward for hyperpolarizing voltage steps of short duration and outward for voltage steps of longer duration. The reversal in tail current polarity indicates that the time-dependent decay in inward current is associated with a change in ESCN.

The association of transient currents with tail currents of opposite polarity suggests that SCN− flux across the cell membrane during the voltage step causes sufficient intracellular SCN− accumulation or depletion to produce a change in ESCN. To test this possibility, we varied the duration of depolarizing voltage steps to +50 mV and monitored tail currents evoked upon stepping Vm to 0 mV. Figure 7C shows that the tail current was outward at the end of a 50-ms depolarizing step but that it reversed polarity and increased in amplitude with depolarizations of longer duration (see inset). In a similar fashion, when the duration of voltage steps to −120 mV was increased incrementally the tail current at −90 mV reversed polarity (Fig. 7D). Similar results were obtained in three other cells. Tail currents following depolarizing voltage steps had fast and slow components and were of opposite polarity when the preceding voltage step was brief but of the same polarity for longer voltage steps. The significance of these two components is not known, but they could reflect the presence of two diffusion-limited, membrane-bound compartments that differ in terms of their relative permeability for SCN− or extent of SCN− accumulation/depletion.

As a further test of the idea that the intracellular concentration of SCN− in RPE cells exposed to 10 mM SCN− approaches electrochemical equilibrium following step changes in membrane voltage, we held the membrane potential at different levels between voltage steps and measured Erev from the resulting instantaneous currents. Figure 8 depicts families of currents evoked in the same RPE cell by a series of voltage steps from holding potentials of −120 mV (A), −60 mV (B), and 0 mV (C). I-V plots of instantaneous currents (insets) show that Erev shifted from −82.1 mV at HP = −120 mV (−110 mV after correcting for junction potentials and the voltage drop across Rs) to −48.8 mV at HP = −60 mV (−53 mV with corrections) and to −0.8 mV at HP = 0 mV (+4.2 mV with corrections). The results of this and similar experiments in multiple other cells are summarized in Fig. 8D. Overall, Erev averaged −90.9 ± 2.3 mV (n = 10), −50.6 ± 2.3 mV (n = 6), and −2.5 ± 1.5 mV (n = 4) at holding potentials of −120 mV (−112.9 ± 0.3 mV with corrections), −60 mV (−54.7 ± 1.2 mV with corrections), and 0 mV (+4.1 ± 0.3 mV with corrections). The corresponding intracellular SCN− concentrations expected for electrochemical equilibrium (Eq. 4) are 289 ± 27 µM, 1.4 ± 0.1 mM, and 9.1 ± 0.5 mM, respectively. The fact that Erev is closely correlated with the holding potential suggests that the fluxes of SCN− across the RPE cell membranes are sufficiently large that the intracellular SCN− concentration rapidly approaches electrochemical equilibrium when the membrane potential is altered.

Fig. 8.

The effect of holding potential on reversal potential (Erev) measured in 10 mM external SCN−. Families of whole cell currents evoked in a retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cell from a holding potential (HP) of −120 mV (A), −60 mV (B), or 0 mV (C). Voltage-clamp protocols and current-voltage (I-V) plots of the instantaneous currents are shown in the insets on the bottom right and top right of each panel, respectively; the zero-current level is shown by the horizontal line to the left of currents. The interval between voltage steps was 20 s for HP = −120 mV or 15 s for HP = −60 mV and HP = 0 mV. The bath and pipette solutions contained high Cl− concentrations. The effective series resistance after series resistance compensation was 2.5 MΩ. D: summary of similar experiments showing I-V plots of instantaneous current obtained from holding potentials of −120 mV (closed circles, n = 10), −60 mV (open circles, n = 6), and 0 mV (closed squares, n = 4). Symbols represent means and bidirectional error bars represent SE. Erev shifted to more negative potentials as the holding potential was made more negative. Voltages are corrected for liquid junction potentials and the voltage drop across the series resistance. The data for HP = −60 mV are from a different set of experiments than that shown in Fig. 6C.

RPE cells have a very large relative permeability for SCN−.

Given that the accumulation of intracellular SCN− leads to the underestimation of PSCN/PCl, the lower limit of PSCN/PCl can be best determined from Erev obtained at a large negative holding potential, where [SCN−]in is minimized. Using the Erev values obtained in the 10 cells recorded with HP = −120 mV, PSCN/PCl averaged 516 ± 49 (mean ± SE; range 328–733). These results indicate that the RPE cell membrane is endowed with an extraordinarily large relative permeability for SCN−.

Excised Patch Experiments

A major conclusion from our whole cell recording experiments is that the RPE basolateral and/or apical membrane contain a conductive mechanism that is highly selective for SCN−. To determine the membrane origin of the SCN−-selective conductance, we performed voltage-clamp recordings of macroscopic currents from excised patches of basolateral or apical membrane in the outside-out orientation.

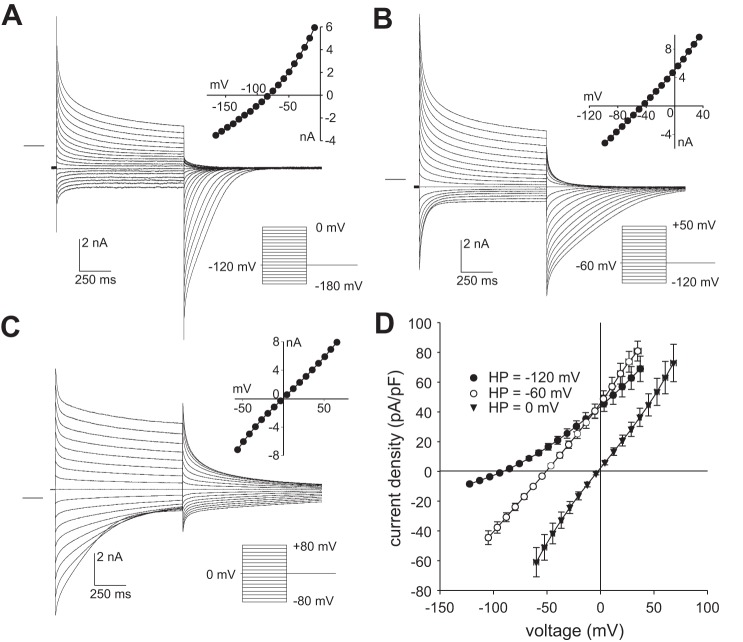

Basolateral membrane has a high conductance and permeability for SCN−.

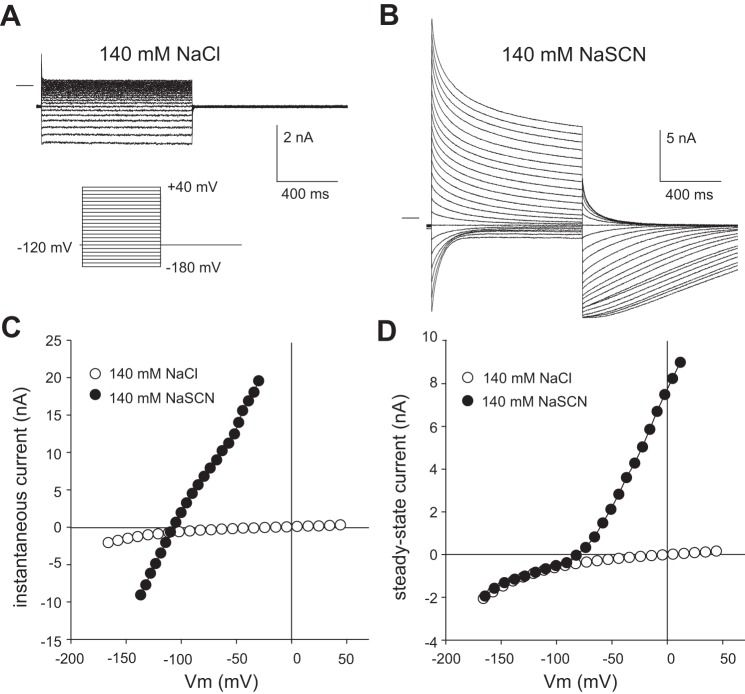

Figure 9A shows families of macroscopic currents evoked by voltage steps from a holding potential of −60 mV in an excised basolateral membrane patch exposed to 140 mM external Cl− (top) or 140 mM external SCN− (bottom). Apical membrane patches are discussed separately below. Macroscopic currents were small in the presence of external Cl− but increased dramatically when Cl− was replaced with SCN−. In external SCN−, depolarizing voltage steps elicited a large outward current that underwent a small, rapid decay and gave way to a steady-state current. In contrast, hyperpolarizing voltage steps produced a transient inward current that relaxed to a small steady-state current. Figure 9C plots the steady-state current as a function of voltage and shows that in the presence of SCN−, the current was outwardly rectifying and had an Erev of about −145 mV. Despite the large increases in current amplitude in the presence of SCN−, current variance did not increase substantially (Fig. 9B). For eight basolateral membrane patches, current amplitude at +40 mV averaged 5.3 ± 1.2 pA and 152.2 ± 42.6 pA in external Cl− and SCN−, respectively (P < 0.01, two-tailed t-test), and the corresponding variance of current averaged 1.01 ± 0.26 pA2 and 1.91 ± 0.44 pA2 (mean ± SE; P < 0.01). Assuming that an anion channel underlies these currents, the absence of a large increase in peak-to-peak noise when external Cl− was replaced with SCN− suggests that the channel either has a small unitary conductance and/or a high open probability. Future experiments involving stationary noise analysis may help distinguish between these possibilities.

Fig. 9.

Macroscopic anion currents recorded from excised outside-out patches of basolateral membrane. A: representative current recordings from an outside-out basolateral membrane patch evoked by voltage steps in the range −160 to +40 mV from a holding potential of −60 mV in the presence of 140 mM external NaCl (top) or 140 mM external NaSCN (bottom). The horizontal line to the left of the traces indicates the zero-current level. The pipette solution contained 140 mM NMDG-Cl. Aside from brief transients that likely reflect the accumulation or depletion of SCN− on the cytoplasmic side of the patch, currents were time independent. B: subset of traces shown in A presented at higher gain. Shown to the right of each trace are the current mean and variance. Current noise in SCN− (as measured by variance) was similar to that in Cl− except at +40 mV, where it doubled. C: current-voltage (I-V) plots of steady-state currents recorded in the presence of 140 mM NaCl or NaSCN in the bath. The data are from the same patch as that depicted in A. D: tail currents obtained in a different basolateral membrane patch exposed to 140 mM external SCN−. Red traces are single exponential fits to the current records. Currents were elicited by stepping the voltage to −90 mV after hyperpolarizing the membrane to −120 mV for different durations from a holding potential of −60 mV. The tail current was inward for the initial 25 ms hyperpolarizing voltage step but was outward for voltage steps of longer duration, indicating that a time-dependent change in reversal potential (Erev) took place. This suggests that transient currents observed in outside-out basolateral membrane patches reflect local changes in SCN− concentration on the cytoplasmic side.

Several aspects of the initial transients suggest that they resulted from the depletion or accumulation of SCN− on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane patch and not from voltage-dependent gating. First, as was observed in whole cell experiments involving 10 mM external SCN−, the transient currents were associated with tail currents of opposite polarity. Second, the kinetics of the decay in current varied widely between basolateral membrane patches, ranging from 14 to 89 ms for outward currents (mean 40.7 ± 6.9 ms, mean ± SE, n = 11) and 25 to 92 ms for inward currents (53 ± 7.6 ms, n = 11). Finally, inward currents evoked by large hyperpolarizing voltage steps decayed toward zero, consistent with the accumulation of SCN− on the cytoplasmic side at the holding potential of −60 mV and its depletion at more negative potentials. In support of this idea, we found that when we varied the duration of hyperpolarizing voltage steps to −120 mV across a basolateral membrane patch that exhibited unusually slow inward current relaxations, tail currents at −90 mV reversed polarity as the duration of the hyperpolarizing step was increased (Fig. 9D). We conclude that the decay in inward and outward currents observed in excised basolateral membrane patches is due to the local depletion or accumulation of SCN− on the cytoplasmic side and that the underlying channel undergoes little, if any, voltage-dependent gating.

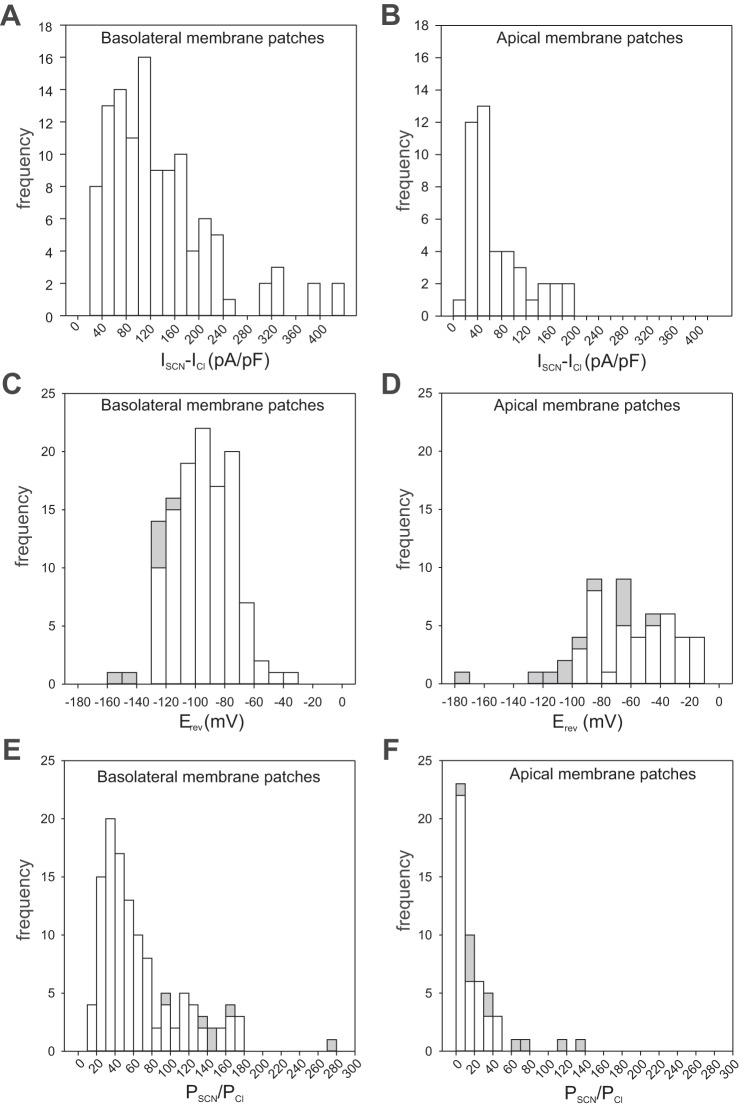

Figure 10A summarizes the results of paired experiments on 115 basolateral membrane patches and depicts the distribution of the change in current at +60 mV produced by the equimolar replacement of 140 mM external Cl− with SCN−. Overall, the current density increased 15-fold from an average of 7.5 ± 0.7 pA/pF (mean ± SE) in Cl− to 123.0 ± 8.5 pA/pF in SCN− (P < E-25, paired t-test); in these same patches, the outward slope conductance increased from 0.14 ± 0.02 nS/pF to 1.24 ± 0.09 nS/pF, nearly a 9-fold increase (data not shown).

Fig. 10.

Basolateral and apical membrane patches differ in their selectivity for SCN−. Top: histograms showing the distribution of the change in current density at +60 mV produced by the replacement of 140 mM external Cl− with SCN− (ISCN – ICl) in outside-out patches of basolateral membrane (A) or apical membrane (B). Mean values of ISCN – ICl for basolateral membrane patches (115.5 ± 0.8 pA/pF; ± SE, n = 115) and apical membrane patches (50.2 ± 1.2 pA/pF; n = 43) were significantly different (P < E-6, Mann-Whitney U-test). The pipette solution contained 144 mM Cl−. Currents were normalized for membrane capacitance. Middle: distribution of reversal potentials (Erev) measured in outside-out patches of basolateral membrane (C) or apical membrane (D). Erev was determined from current-voltage (I-V) plots of currents generated by voltage ramps or steady-state currents evoked by voltage steps. Open bars represent data obtained from a holding potential of −60 mV and closed bars data from a holding potential of −120 mV. Mean values of Erev for basolateral membrane patches (−95.1 ± 1.9 mV; n = 121) and apical membrane patches (−63.5 ± 5.1 mV; n = 52) were significantly different (P < E-9, Mann-Whitney U-test). Data from two basolateral membrane patches and one apical membrane patch that were unresponsive to SCN are excluded from this analysis. Bottom: distribution of relative SCN− permeability (PSCN/PCl) values for outside-out patches of basolateral membrane (E) or apical membrane (F). Erev values were calculated from the data shown in C and D using the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation. Not shown in the histograms are a PSCN/PCl value of 396 from one basolateral patch and a PSCN/PCl value of 869 from one apical patch. Mean values of PSCN/PCl for basolateral membrane patches (61.2 ± 5.1; n = 121) and apical membrane patches (37.4 ± 19.4; n = 52) were significantly different (P < E-10, Mann-Whitney U-test.

Replacement of external Cl− with SCN− also resulted in a large negative Erev. Figure 10C summarizes the distribution of Erev values obtained from I-V plots of steady-state currents in 121 basolateral membrane patches and shows that nearly 90% of the patches had an Erev value that was more negative than −70 mV; overall, Erev averaged −95.1 ± 1.9 mV (mean ± SE). This value compares well to measurements of Vm made under the zero-current clamp condition in a more limited number of basolateral membrane patches (−102.0 ± 4.8 mV, n = 24). Figure 10E shows the distribution of PSCN/PCl values calculated from Erev using the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation (Eq. 2); for all experiments, PSCN/PCl averaged 61.2 ± 5.1 (n = 114; range, 3.5 to 396). Thus, we conclude that the RPE basolateral membrane has a very large relative permeability to SCN−.

Apical membrane patches exhibit an SCN− conductance that differs from that of the basolateral membrane.

We used the same approach to investigate anion currents in outside-out apical membrane patches, but the number of successful experiments was more limited because of difficulty in forming tight seals with the pipette tip. Figure 10B summarizes the results of 43 paired experiments on apical membrane patches. The majority of apical membrane patches tested showed an increase in outward current amplitude when Cl− was replaced with SCN−, with the average current density increasing 6-fold from 11.1 ± 2.2 pA/pF to 61.4 ± 8.4 pA/pF (P < E-6, paired t-test) and the average outward slope conductance increasing 3-fold from 0.22 ± 0.04 nS/pF to 0.68 ± 0.09 nS/pF (data not shown). Overall, both the current density and outward conductance in the presence of high external SCN− were significantly smaller in apical membrane patches than they were in basolateral membrane patches (P < E-6, Mann-Whitney U-test).

Another way that SCN− currents in apical membrane patches differed from those basolateral membrane patches is that they reversed at more depolarized voltages. Figure 10D summarizes the distribution of Erev values obtained in 52 apical membrane patches exposed to 140 mM external SCN− and shows that only 37% of the patches had an Erev value that was more negative than −70 mV. Overall, Erev averaged −63.5 ± 5.1 mV (range, −13.5 to −171.0 mV), a value that is significantly smaller than that obtained in basolateral membrane patches (P < E-9, Mann-Whitney U-test). Figure 10E shows the distribution of PSCN/PCl values calculated from Erev for each of the apical membrane patches; overall, PSCN/PCl in apical membrane patches averaged 37.5 ± 19.4 (n = 52; range, 2 to 869). Thus, PSCN/PCl in apical membrane patches is significantly smaller than that in basolateral membrane patches (P < E-10, Mann-Whitney U-test).

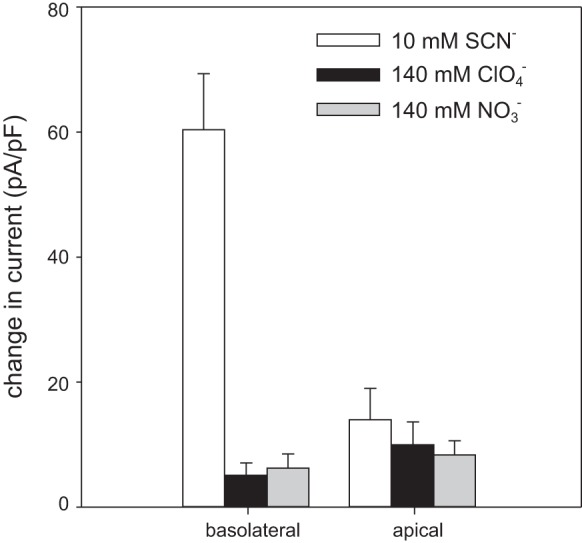

To further characterize the properties of basolateral and apical membrane patches, we also recorded currents in the presence of 10 mM SCN−. For basolateral membrane patches, current density at +60 mV increased 5-fold from an average of 14.6 ± 5.3 pA/pF in the presence of 145.6 mM Cl− to an average of 75.0 ± 12.2 pA/pF (n = 8) when 10 mM Cl− was replaced equimolar with SCN− (Fig. 11). In contrast, the replacement of 10 mM Cl− with SCN− outside apical membrane patches increased the average current density 3-fold from 7.1 ± 2.1 pA/pF to 21.1 ± 4.6 pA/pF (n = 8; P < 0.005, Mann-Whitney U-test). In addition, we tested the effects of 140 mM external ClO4− and 140 mM external (Fig. 11). We found that the change in current density at +60 mV in basolateral membrane patches produced by replacing external Cl− with ClO4− (5.1 ± 2.0 pA/pF, n = 16) or (6.2 ± 2.3 pA/pF, n = 34) was not significantly different from that in apical membrane patches (ClO4−: 10.0 ± 4.0 pA/pF, n = 14; : 8.6 ± 2.1 pA/pF, n = 15; P > 0.05). Thus, we conclude that the anion conductance of the basolateral membrane has a larger relative conductance and relative permeability for SCN− compared with that of the apical membrane.

Fig. 11.

Basolateral and apical membrane patches differ in their response to 10 mM external SCN−. Vertical bars represent the mean change in current density at +60 mV produced by the replacement of 10 mM Cl− with SCN− (open bars) or the replacement of 140 mM Cl− with ClO4− (black bars) or (gray bars) in outside-out patches of basolateral (left) or apical membrane (right). The current density in 10 mM SCN− was significantly higher in basolateral membrane patches (75.0 ± 12.2 pA/pF, n = 8) than it was in apical membrane patches (21.1 ± 4.6 pA/pF, n = 8; P < 0.005). The was no significant difference in current density between basolateral membrane patches and apical membrane patches exposed to 140 mM external ClO4− or .

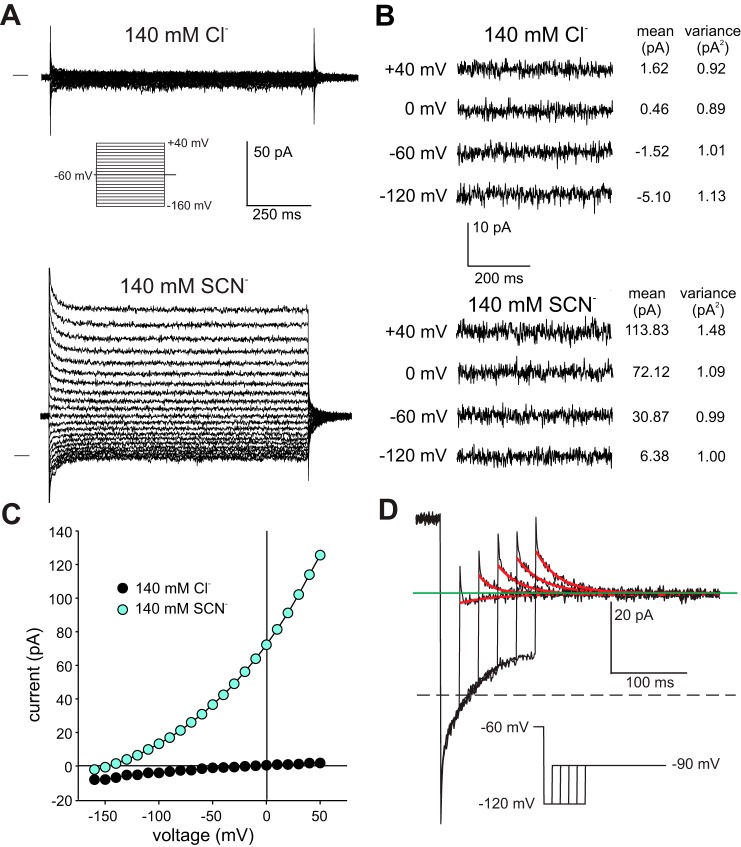

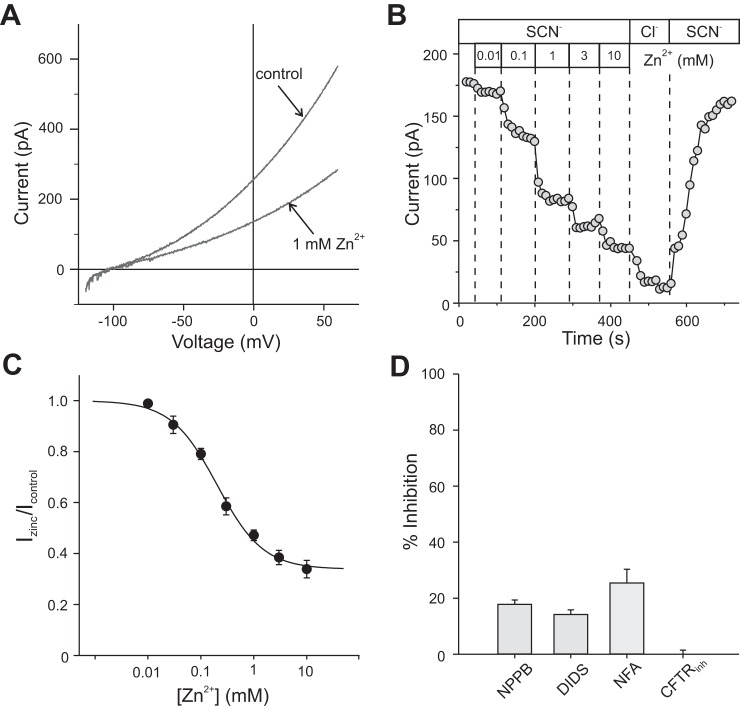

Blocker sensitivity of the basolateral membrane SCN− current.

To gain additional information about the properties of the basolateral membrane SCN− conductance, we investigated the effects of various anion channel inhibitors on the current in outside-out basolateral membrane patches exposed to 140 mM external SCN−. We found that Zn2+, a blocker of ClC-2 channels (47), was the most effective inhibitor of SCN− current tested. Figure 12A shows I-V plots of voltage-ramp evoked currents recorded in a basolateral membrane patch in the absence and presence of 1 mM Zn2+. At this concentration, Zn2+ blocked ~50% of the current at +60 mV. The effects of various concentrations of Zn2+ on the SCN− current at +60 mV in a different basolateral membrane patch are depicted in Fig. 12B, which shows that the Zn2+-induced block was concentration dependent and reversible. Figure 12C plots the fraction of SCN− current remaining as a function of Zn2+ concentration. The closed circles represent the mean values of measurements in 4 to 10 basolateral membrane patches and the vertical bars represent the SE; the continuous trace is the nonlinear least-squares fit of the data to Eq. 3, with an IC50 of 284 µM. Cadmium (500 µM), a more potent blocker of ClC-2 channels than zinc (44), had no effect on SCN− current in three basolateral membrane patches (results not shown).

Fig. 12.

Blocker sensitivity of SCN− currents in outside-out patches of basolateral membrane. A: current-voltage (I-V) plots of currents recorded in the absence and presence of 1 mM external Zn2+. The bath contained 140 mM NaSCN and the pipette solution contained 135 mM NMDG-Cl. Currents were evoked by a 1-s voltage ramp from −120 to +60 mV with the voltage held at −60 mV between ramps. B: dose-dependent inhibition of the current at +60 mM recorded in a different basolateral membrane patch. The top row of boxes indicates when the patch was exposed to 140 mM SCN− or 140 mM Cl−, and the row of boxes immediately below designate the concentration of Zn2+. C: dose-response relationship for the Zn2+-induced block. Values are means ± SE (n = 4–10). Least-squares fit (solid line) of data to Eq. 3 yields IC50 = 284 µM. D: percent inhibition of SCN− current in basolateral membrane patches by 200 μM NPPB (n = 6), 500 μM DIDS (n = 8), 100 μM niflumic acid (NFA, n = 5), and 3 μM CFTRinh172 (n = 7). Bars represent means and error bars represent SE. IC50, half-maximal concentration for block. NPPB, 5-nitro-(3-phenylpropyl-amino)-benzoic acid.

Other anion channel blockers tested were less effective in inhibiting the basolateral membrane SCN− current (Fig. 12D). At a concentration of 200 μM, 5-nitro-(3-phenylpropyl-amino)-benzoic acid (NPPB), an inhibitor of both TMEM16A and BEST1 channels (28), blocked the SCN− current at +60 mV by ~14%; likewise, 500 μM 4,4′-diisothiocyano-2,2′-stilbenedisulfonic acid (DIDS), a blocker of multiple different anion channels, including BEST1 and TMEM16A (29), produced about a 14% block. Niflumic acid, a blocker of Best1, TMEM16A (28), and other Ca2+-activated Cl− channels, blocked ~25% of the SCN− current when applied at a concentration of 100 μM. Finally, we tested the effect of CFTRinh 172, an inhibitor of CFTR, TMEM16A (28), and ClC-2 (9) channels. At a concentration of 3 μM, CFTRinh 172 had no significant effect on the SCN− current in RPE basolateral membrane patches.

DISCUSSION

Cl− channels in the RPE are of considerable importance because of their critical role in the active transport of Cl− in the retina-to-choroid direction, a major driving force for fluid absorption and control of the extracellular volume of subretinal fluid surrounding the photoreceptor outer segments. Although multiple Cl− channels are known to be expressed in the RPE, identification of the ion channels that constitute the resting basolateral membrane Cl− conductance has not been well established, in part because the biophysical properties of this conductance have not been fully characterized. In the present study, we used the patch-clamp technique to determine the ion selectivity of the anion conductance of RPE cells isolated from C57/B6 mice. We show for the first time that acutely dissociated mouse RPE cells exhibit an anion conductance that is highly selective for SCN−, with a relative conductance for SCN− (GSCN/GCl) of ~40 and a relative SCN− permeability (PSCN/PCl) of ~500. These properties can be attributed at least in part to a previously unappreciated anion channel or electrogenic transporter residing in the basolateral membrane.

SCN− accumulation and depletion.

Whole cell currents evoked by voltage steps in the presence of external SCN− were not only large in amplitude but also exhibited a time-dependent decay during voltage steps followed by prominent tail currents of opposite polarity. What accounts for the time dependency of the SCN− current? Indicative that the mechanism was not the result of voltage-dependent gating, we found that the decay in outward and inward currents was not associated with a decrease in membrane conductance. Instead, our data lend strong support for the scenario in which the time-dependent changes in current are a consequence of large transmembrane SCN− fluxes causing the accumulation or depletion of intracellular SCN− and a decrease in driving force (Vm – ESCN). Evidence for this mechanism comes from the observations that 1) Erev of instantaneous currents recorded in 10 mM external SCN− were correlated with the holding potential, indicating that [SCN−]in approaches electrochemical equilibrium in the steady state; and 2) the decline in current during depolarizing and hyperpolarizing voltage steps was associated with changes in ESCN, as indicated by reversals in tail current polarity as the duration of the voltage step was increased.

Our results are qualitatively similar to those previously reported for neocortical neurons during GABAA receptor activation (12), where it was shown that transient currents resulted from the accumulation and depletion of intracellular Cl−. A similar phenomenon involving K+ has been described in isolated mouse ventricular myocytes, in which tail currents generated at the offset of depolarizing voltage steps are due to the accumulation of K+ within the diffusion-limited space of t-tubules (8). Given that the RPE basal membrane is highly elaborated with an extensive network of infoldings that occupy up to 20% of the cytoplasmic volume in situ (35), it seems possible that the accumulation/depletion of SCN− in diffusion-limited extracellular spaces of the RPE as well as in the cytoplasm contributes to the transient currents observed in the current study. This two-compartment hypothesis may account for the two phases observed in the time-dependent decay in current during and following voltage steps: a fast component corresponding to SCN− accumulation/depletion in the relatively small extracellular volume of basal membrane infoldings and a slow component corresponding to SCN− accumulation/depletion in the cytoplasm.

Estimation of PSCN/PCl.

We found that when RPE cells were exposed to 10 or 140 mM SCN−, Erev measured from instantaneous currents varied with the holding potential (Figs. 2, 5, and 8), indicating that intracellular concentration of SCN− approaches electrochemical equilibrium in the steady state. However, because [SCN−]in is unknown, this term was omitted from the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation (Eq. 2), resulting in an underestimation of PSCN/PCl. This error was smaller under conditions expected for low [SCN−]in, i.e., low [SCN−]out and a large negative holding potential. In this study, the lowest intracellular SCN− concentration of <300 μM was achieved when RPE cells were exposed to 10 mM external SCN− and the holding potential was −120 mV, which yielded a PSCN/PCl value of ~500. This high value indicates that the anion conductance of the RPE discriminates between anions to an extraordinary degree.

Membrane location of the SCN−-selective conductance.

To localize the membrane origin of the SCN−-selective conductance, we recorded macroscopic currents from excised outside-out patches of basolateral and apical membranes. We showed previously using the cell-attached patch mode that isolated bovine RPE cells exhibited Kir7.1 channels predominantly in the apical membrane (46), establishing that RPE cells can remain functionally polarized following enzymatic dissociation. Here, we found that both basolateral and apical membrane patches exhibited increases in current when 140 mM external Cl− was replaced with SCN−. The size of the response varied from patch to patch, but on average, there was a 15-fold increase in current density in basolateral membrane patches compared with a 6-fold increase in apical membrane patches. In addition to exhibiting a higher SCN− current density, basolateral membrane patches also had a larger relative permeability for SCN−, with 22% of the basolateral membrane patches having a PSCN/PCl value >100 compared with only 6% of the apical membrane patches and PSCN/PCl averaging 61 and 37 for basolateral and apical membrane patches, respectively. The PSCN/PCl values observed in most excised patches were lower than that estimated from whole cell measurements, which was ~500. The reason for this discrepancy is unknown but could be explained if a conductance with high relative permeability for SCN− were localized to subdomains of the basolateral and apical membranes, such as infoldings and microvilli, that were not present in outside-out membrane patches. Another factor that could contribute to lower PSCN/PCl values in excised membrane patches is the presence of SCN− on the cytoplasmic side of the patch.

Ando and Noell (2) showed in the early 1990s that a bolus injection of SCN− into the systemic circulation of rats produced a negative-going change in transocular potential on the order of several millivolts. They ascribed this response to a hyperpolarization of the RPE basolateral membrane, and suggested that it arose because of the membrane’s high SCN− permeability. Our demonstration that the RPE basolateral membrane contains a SCN−-selective conductance lends strong support to Ando and Noell’s hypothesis made decades ago.

Membrane mechanism of conductive SCN− flux.

What is the mechanism(s) underlying the SCN−-selective conductances of the RPE? It has been demonstrated that 20 mM SCN− produces a moderate increase in the conductance of artificial lipid membranes (~4 × 10−7 S/cm2; 16), but this value is nearly three orders of magnitude smaller than the conductance produced by 10 mM SCN− in RPE cells (~2.5 × 10−4 S/cm2, assuming a conductance of 0.25 nS/pF and 106 pF/cm2). Thus, we can exclude lipid permeation of SCN− as the mechanism for the SCN−conductance.

As noted earlier, several different Cl− channels have been proposed as components of the RPE basolateral membrane Cl− conductance, including CFTR (5), BEST1 (31), ClC-2 (7), TMEM16A (10), and TMEM16B (23). All of these Cl− channels can be rejected as the predominant contributor to the SCN− conductance characterized in this study because none has a PSCN/PCl or GSCN/GCl greater than 5 (3, 11, 30, 37, 39), which is considerably lower than what we found (GSCN/GCl ≈40, PSCN/PCl ~500). A recent gene expression profiling study identified SLC26A7 (6) as being highly expressed in human RPE. Originally thought to function as a Cl−/HCO3− exchanger, SLC26A7 was later found to be a bona fide Cl− channel (24) and to have a very high conductance for SCN− (42). Cl− currents mediated by SLC26A7 heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes were blocked 60% by 100 µM 5-nitro-(3-phenylpropyl-amino)-benzoic acid (26) and 50% by 500 µM DIDS (24). We found that neither of these blockers inhibited SCN− currents in RPE basolateral membrane patches by more than 20% but that Zn2+ was an effective blocker, with an IC50 of 284 µM. It is important to note, however, that interactions between permeant ions and ion channels can affect blocker affinity (27), so comparisons between our results and published blocker sensitivity profiles obtained with Cl− as the major anion must be taken with caution. Ultimately, experiments involving the use of gene knockdown will be needed to determine whether SLC26A7 contributes to the SCN− conductances of the RPE basolateral and apical membranes.

In addition to Cl− channels, two classes of transporters should be considered as potential mediators of the SCN−-selective anion conductance of the RPE cell membranes: 1) excitatory amino acid transporters (EAAT; 33, 43) and neutral amino acid transporters (ASCT) (15, 56) of the SLC1 gene family, which contain parallel anion conductances that are selective for SCN−; and 2) anion exchangers in the ClC and SLC26 gene families that become an uncoupled anion conductances when external Cl− is replaced with SCN− (1, 45). Studies on native RPE and RPE cell lines have documented the expression of several members of these gene families, including EAAT3, EAAT4 (29), SLC26A6 (21), as well ClC-3, ClC-5 (52), ClC-4 (48), and ClC-7 (25). It seems unlikely that any of these ClC family members contribute to SCN− currents in the RPE as these anion exchangers are normally located in intracellular organelles. Experiments testing the requirement for external Na+ and sensitivity to specific EAAT and ASCT blockers could shed light on the contribution of SLC1 transporters to the anion conductances of the basolateral and apical membranes of the RPE, but these experiments are beyond the scope of the present study.

Physiological significance.

Anion channels in the basolateral membrane of the RPE play a key role in the active transport of Cl− between the subretinal space, which surrounds the outer segments of rod and cone photoreceptors and the distal retina blood supply in the choroid (4, 22, 34). Although Cl− is transported into the cell via the Na,K,2Cl cotransporter in the apical membrane (34), where it accumulates intracellularly above its electrochemical equilibrium (4), it is the passive efflux of Cl− through anion channels in the basolateral membrane that completes the retina-to-choroid absorption of Cl−.

Although a number of candidate Cl− channels have been identified in the RPE (53), the molecular composition of the steady-state basolateral membrane Cl− conductance remains unclear. Our study identifies a previously unappreciated anion conductance in the basolateral membrane that could potentially be involved in Cl− efflux. Although the conductance is highly selective for SCN−, it likely has a finite Cl− permeability and may serve as a pathway for Cl− efflux under physiological conditions, where Cl− is the major anion inside and outside the RPE cell and the basolateral membrane potential is about −50 mV (22). Confirmation that this anion conductance plays a role in active Cl− transport across the RPE will require the identification and knockdown of the gene that encodes it or the discovery of a highly specific blocker.

SCN− is ubiquitously present in extracellular fluids as a product of cyanide metabolism. In human plasma, its concentration varies from 20 to 100 µM, depending on dietary sources of cyanogenic compounds (38) and can exceed 125 µM in smokers (36). In the respiratory and digestive systems, SCN− is oxidized to OSCN− via the lactoperoxidase system, a reaction that protects against oxidative damage by consuming H2O2; SCN− also plays a protective role in inflammation by inhibiting the production of hypochlorite (OCl−) by myeloperoxidase released from white blood cells and by scavenging OCl− (55). SCN− is actively secreted by epithelia lining the digestive (51) and respiratory tracts (13), but in the central nervous system, it is cleared from the cerebral spinal fluid by active transport across the choroid plexus (54). Although the physiological significance for SCN− absorption by the choroid plexus is unclear, it could serve to protect against the adverse central excitatory effects of SCN− (14).

Given that the retina is a component of the central nervous system, it is intriguing to consider the possibility that the SCN−-selective anion conductance in the RPE basolateral membrane is part of a transcellular SCN− transport pathway that protects the function of retinal neurons by removing SCN− that crosses the blood-retinal barrier from the plasma. Alternatively, the SCN− conductances of the basolateral and apical membranes could provide mechanisms for the influx of SCN− from the plasma into the RPE cell and into the distal retina, where it could provide protection against oxidative stress and damage from OCl− in inflammatory diseases of the retina, such as uveitis. Additional studies are needed to determine the role of the SCN−-selective conductances of the RPE apical and basolateral membranes in the physiology and pathophysiology of the RPE and outer retina.

GRANTS

This work was supported by NIH National Eye Institute Grant EY-08850, Core Grant EY-07703, and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

X.C., B.R.P., and B.A.H. conceived and designed research; X.C., B.R.P., and B.A.H. performed experiments; X.C. and B.A.H. analyzed data; X.C., B.R.P., and B.A.H. interpreted results of experiments; B.A.H. prepared figures; B.A.H. drafted manuscript; X.C, B.R.P., and B.A.H. edited and revised manuscript; X.C., B.R.P., and B.A.H. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Donald Puro for helpful discussion.

Present address of B. R. Pattnaik: Dept. of Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alekov AK, Fahlke C. Channel-like slippage modes in the human anion/proton exchanger ClC-4. J Gen Physiol 133: 485–496, 2009. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ando H, Noell WK. Electrical responses of the rat’s retinal pigment epithelium to azide and thiocyanate. Jpn J Physiol 43: 299–309, 1993. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.43.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betto G, Cherian OL, Pifferi S, Cenedese V, Boccaccio A, Menini A. Interactions between permeation and gating in the TMEM16B/anoctamin2 calcium-activated chloride channel. J Gen Physiol 143: 703–718, 2014. [Erratum in J Gen Physiol 144: 125, 2014.] doi: 10.1085/jgp.201411182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bialek S, Miller SS. K+ and Cl− transport mechanisms in bovine pigment epithelium that could modulate subretinal space volume and composition. J Physiol 475: 401–417, 1994. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaug S, Quinn R, Quong J, Jalickee S, Miller SS. Retinal pigment epithelial function: a role for CFTR? Doc Ophthalmol 106: 43–50, 2003. doi: 10.1023/A:1022514031645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Booij JC, ten Brink JB, Swagemakers SM, Verkerk AJ, Essing AH, van der Spek PJ, Bergen AA. A new strategy to identify and annotate human RPE-specific gene expression. PLoS One 5: e9341, 2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bösl MR, Stein V, Hübner C, Zdebik AA, Jordt SE, Mukhopadhyay AK, Davidoff MS, Holstein AF, Jentsch TJ. Male germ cells and photoreceptors, both dependent on close cell-cell interactions, degenerate upon ClC-2 Cl(−) channel disruption. EMBO J 20: 1289–1299, 2001. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark RB, Tremblay A, Melnyk P, Allen BG, Giles WR, Fiset C. T-tubule localization of the inward-rectifier K(+) channel in mouse ventricular myocytes: a role in K(+) accumulation. J Physiol 537: 979–992, 2001. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuppoletti J, Chakrabarti J, Tewari KP, Malinowska DH. Differentiation between human ClC-2 and CFTR Cl− channels with pharmacological agents. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 307: C479–C492, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00077.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dauner K, Möbus C, Frings S, Möhrlen F. Targeted expression of anoctamin calcium-activated chloride channels in rod photoreceptor terminals of the rodent retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54: 3126–3136, 2013. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Jesús-Pérez JJ, Castro-Chong A, Shieh RC, Hernández-Carballo CY, De Santiago-Castillo JA, Arreola J. Gating the glutamate gate of CLC-2 chloride channel by pore occupancy. J Gen Physiol 147: 25–37, 2016. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201511424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeFazio RA, Hablitz JJ. Chloride accumulation and depletion during GABA(A) receptor activation in neocortex. Neuroreport 12: 2537–2541, 2001. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200108080-00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fragoso MA, Fernandez V, Forteza R, Randell SH, Salathe M, Conner GE. Transcellular thiocyanate transport by human airway epithelia. J Physiol 561: 183–194, 2004. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.071548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goto K, Esplin DW. Excitatory effects of thiocyanate on spinal cord. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 133: 129–136, 1961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grewer C, Grabsch E. New inhibitors for the neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2 reveal its Na+-dependent anion leak. J Physiol 557: 747–759, 2004. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.062521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutknecht J, Walter A. SCN−and HSCN transport through lipid bilayer membranes. A model for SCN− inhibition of gastric acid secretion. Biochim Biophys Acta 685: 233–240, 1982. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(82)90062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartzell HC, Qu Z. Chloride currents in acutely isolated Xenopus retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Physiol 549: 453–469, 2003. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes BA, Segawa Y. cAMP-activated chloride currents in amphibian retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Physiol 466: 749–766, 1993. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes BA, Takahira M. Inwardly rectifying K+ currents in isolated human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 37: 1125–1139, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes BA, Takahira M, Segawa Y. An outwardly rectifying K+ current active near resting potential in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 269: C179–C187, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.1.C179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iserovich P, Qin Q, Petrukhin K. DPOFA, a Cl−/HCO3− exchanger antagonist, stimulates fluid absorption across basolateral surface of the retinal pigment epithelium. BMC Ophthalmol 11: 33, 2011. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-11-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joseph DP, Miller SS. Apical and basal membrane ion transport mechanisms in bovine retinal pigment epithelium. J Physiol 435: 439–463, 1991. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keckeis S, Reichhart N, Roubeix C, Strauß O. Anoctamin2 (TMEM16B) forms the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel in the retinal pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res 154: 139–150, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim KH, Shcheynikov N, Wang Y, Muallem S. SLC26A7 is a Cl− channel regulated by intracellular pH. J Biol Chem 280: 6463–6470, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kornak U, Kasper D, Bösl MR, Kaiser E, Schweizer M, Schulz A, Friedrich W, Delling G, Jentsch TJ. Loss of the ClC-7 chloride channel leads to osteopetrosis in mice and man. Cell 104: 205–215, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosiek O, Busque SM, Föller M, Shcheynikov N, Kirchhoff P, Bleich M, Muallem S, Geibel JP. SLC26A7 can function as a chloride-loading mechanism in parietal cells. Pflugers Arch 454: 989–998, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0254-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linsdell P. Interactions between permeant and blocking anions inside the CFTR chloride channel pore. Biochim Biophys Acta 1848: 1573–1590, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Zhang H, Huang D, Qi J, Xu J, Gao H, Du X, Gamper N, Zhang H. Characterization of the effects of Cl− channel modulators on TMEM16A and bestrophin-1 Ca2+ activated Cl− channels. Pflugers Arch 467: 1417–1430, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mäenpää H, Gegelashvili G, Tähti H. Expression of glutamate transporter subtypes in cultured retinal pigment epithelial and retinoblastoma cells. Curr Eye Res 28: 159–165, 2004. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.28.3.159.26244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mansoura MK, Smith SS, Choi AD, Richards NW, Strong TV, Drumm ML, Collins FS, Dawson DC. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) anion binding as a probe of the pore. Biophys J 74: 1320–1332, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77845-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marmorstein AD, Marmorstein LY, Rayborn M, Wang X, Hollyfield JG, Petrukhin K. Bestrophin, the product of the Best vitelliform macular dystrophy gene (VMD2), localizes to the basolateral plasma membrane of the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 12758–12763, 2000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220402097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marmorstein LY, Wu J, McLaughlin P, Yocom J, Karl MO, Neussert R, Wimmers S, Stanton JB, Gregg RG, Strauss O, Peachey NS, Marmorstein AD. The light peak of the electroretinogram is dependent on voltage-gated calcium channels and antagonized by bestrophin (best-1). J Gen Physiol 127: 577–589, 2006. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melzer N, Biela A, Fahlke C. Glutamate modifies ion conduction and voltage-dependent gating of excitatory amino acid transporter-associated anion channels. J Biol Chem 278: 50112–50119, 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307990200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller SS, Edelman JL. Active ion transport pathways in the bovine retinal pigment epithelium. J Physiol 424: 283–300, 1990. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mishima H, Kondo K. Ultrastructure of age changes in the basal infoldings of aged mouse retinal pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res 33: 75–84, 1981. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4835(81)80083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan PE, Pattison DI, Talib J, Summers FA, Harmer JA, Celermajer DS, Hawkins CL, Davies MJ. High plasma thiocyanate levels in smokers are a key determinant of thiol oxidation induced by myeloperoxidase. Free Radic Biol Med 51: 1815–1822, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Driscoll KE, Leblanc N, Hatton WJ, Britton FC. Functional properties of murine bestrophin 1 channel. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 384: 476–481, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olea F, Parras P. Determination of serum levels of dietary thiocyanate. J Anal Toxicol 16: 258–260, 1992. doi: 10.1093/jat/16.4.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peters CJ, Yu H, Tien J, Jan YN, Li M, Jan LY. Four basic residues critical for the ion selectivity and pore blocker sensitivity of TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 3547–3552, 2015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502291112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peterson WM, Meggyesy C, Yu K, Miller SS. Extracellular ATP activates calcium signaling, ion, and fluid transport in retinal pigment epithelium. J Neurosci 17: 2324–2337, 1997. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02324.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quinn RH, Quong JN, Miller SS. Adrenergic receptor activated ion transport in human fetal retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42: 255–264, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schänzler M, Fahlke C. Anion transport by the cochlear motor protein prestin. J Physiol 590: 259–272, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.209577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]