Abstract

Declines in motor function with advancing age have been attributed to changes occurring at all levels of the neuromuscular system. However, the impact of aging on the control of muscle force by spinal motor neurons is not yet understood. In this study on 20 individuals aged between 24 and 75 yr (13 men, 7 women), we investigated the common synaptic input to motor neurons of the tibialis anterior muscle and its impact on force control. Motor unit discharge times were identified from high-density surface EMG recordings during isometric contractions at forces of 20% of maximal voluntary effort. Coherence analysis between motor unit spike trains was used to characterize the input to motor neurons. The decrease in force steadiness with age (R2 = 0.6, P < 0.01) was associated with an increase in the amplitude of low-frequency oscillations of functional common synaptic input to motor neurons (R2 = 0.59; P < 0.01). The relative proportion of common input to independent noise at low frequencies increased with variability (power) in common synaptic input. Moreover, variability in interspike interval did not change and strength of the common input in the gamma band decreased with age (R2 = 0.22; P < 0.01). The findings indicate that age-related reduction in the accuracy of force control is associated with increased common fluctuations to motor neurons at low frequencies and not with an increase in independent synaptic input.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The influence of aging on the role of spinal motor neurons in accurate force control is not yet understood. We demonstrate that aging is associated with increased oscillations in common input to motor neurons at low frequencies and with a decrease in the relative strength of gamma oscillations. These results demonstrate that the synaptic inputs to motor neurons change across the life span and contribute to a decline in force control.

Keywords: aging, common synaptic input, force steadiness, neural drive to muscles

INTRODUCTION

The fluctuations in force during steady isometric contractions increase in proportion to the average force, a phenomenon referred to as signal-dependent noise (Enoka et al. 1999; Harris and Wolpert 1998; Jones et al. 2002). The neural origin of these fluctuations is uncertain. Previous studies have suggested that they may be associated with either variability (Taylor et al. 2003) or synchrony of the times at which motor neurons discharge action potentials (Datta and Stephens 1990; Semmler and Nordstrom 1998). In addition, properties of the motor unit pool, such as the range of twitch amplitudes and of recruitment thresholds, have also been suggested to impact force variability by influencing signal-dependent noise (Jones et al. 2002).

Force fluctuations during steady contractions increase with advancing age (Birren et al. 2006; Dayanidhi and Valero-Cuevas 2014; Enoka et al. 1999; Galganski et al. 1993) concurrent with remodeling of motor unit populations (Fling et al. 2009). For example, the number of recruited motor units for generating a relative force level (Brown 1972; McNeil et al. 2005) and their discharge rate decrease with aging (Connelly et al. 1999; Erim et al. 1999; Kallio et al. 2012; Vaillancourt et al. 2003), whereas their discharge variability increases (Soderberg et al. 1991). Nonetheless, the decline in force accuracy appears to be unrelated to the remodeling of motor unit populations (Barry et al. 2007). Rather, the responsible mechanisms likely involve the synaptic input that motor neurons receive in the relevant bandwidth for force generation.

Some of the excitatory and inhibitory input to motor neurons from supraspinal regions and muscle afferents is shared within and between motor neuron pools (Keen and Fuglevand 2004; Laine et al. 2015; Lawrence et al. 1985). This common input can originate from shared (divergent) structural connections or correlated inputs to motor neurons (Boonstra et al. 2016). Because the neural drive to muscles corresponds to the integration of the activity by a motor neuron population, the independent inputs are attenuated and the net force is mainly attributable to the common (shared or correlated) inputs (Baldissera et al. 1998; Farina and Negro 2015). Therefore, assuming an approximately linear transmission of common input by the pool of motor neurons (Negro and Farina 2011), the neural drive to muscle produces a force that reflects the low-frequency components of the common synaptic input (Farina et al. 2014, 2016). Accordingly, previous studies have suggested that low-frequency oscillations in force (<0.5 Hz) during voluntary contractions can be modulated by increasing the frequency of oscillation with visual feedback and motor training (Fox et al. 2013; Lodha and Christou 2017; Moon et al. 2014; Park et al. 2017).

If the shared (common) input to motor neurons changes with age, there should be an associated effect on force control. The purpose of our study was to examine the association between an estimate of common synaptic input and force steadiness during submaximal isometric contractions performed by adults with a broad range of ages. We hypothesized that variability in functional common synaptic input to motor neurons increases with age and that this increase explains the reduction in force steadiness.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants.

Twenty adults (age range: 24–75 yr, median age: 43 yr; 13 men, 7 women) participated in the study. Inclusion criteria comprised no previous history of lower limb related pathology or surgery. Also, none of the subjects reported any neurological disorder or consumed any neurotropic medication within the 24 h before the experiment. Participants signed an informed consent form after having read and understood all experimental procedures and risks. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental design.

The participants sat on a chair in an upright position with the right foot attached to a pedal that was connected to a force transducer (Biodex Multi Joint System 3; Biodex Medical Systems, Shirley, NY). They were initially asked to perform a maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) force three times, with 3 min of rest within trials. After a brief rest (~5 min), they were then instructed to perform an isometric contraction with the dorsiflexor muscles and to match a target force displayed on a monitor placed at a distance of 1.5 m. The gain of the visual feedback was standardized for all participants to avoid differences in the cue perception. The target force was set at 20% MVC, and the participants were asked to reach this level in 5 s, to hold it for 30 s, and then to relax for 5 s. The choice of this force level was based on the known trends for the coefficient of variation for force and the need to minimize fatigue. The coefficient of variation for force is known to decrease rapidly until ~10% MVC (Moritz et al. 2005); thus this force range was avoided. Moreover, greater forces would have evoked changes in coherence analysis due to fatigue (Castronovo et al. 2015a).

EMG and force.

High-density surface electromyographic (HD-sEMG) signals were recorded from the tibialis anterior muscle during isometric contractions with a 256-channel EMG amplifier (EMG-USB2; OT Bioelettronica, Turin, Italy) and semidisposable adhesive grids with 64 electrodes that were 8 mm apart. The skin was shaved and cleansed before the electrode grid was attached with adhesive foam. The EMG signals were recorded in monopolar mode, amplified, sampled at 2,048 samples/s, and digitized with a 12-bit A/D converter. Ankle dorsiflexor force was sampled at 5,000 samples/s and synchronized with the EMG recordings.

Data processing.

EMG and force signals were analyzed with custom-made software developed in MATLAB (MathWorks). The data were extracted from a 30-s segment of the steady contraction.

HD-sEMG signals were decomposed into trains of motor unit discharge times with a state-of-the art algorithm based on convolutive blind-source separation (Holobar and Zazula 2007; Negro et al. 2016a). The accuracy of decomposition for each identified spike train was assessed through a validated measure (Negro et al. 2016a), so that only spike trains with an accuracy of >90% were retained for further analysis. Discharges corresponding to interspike intervals <10 ms and >250 ms, which occurred rarely (<2% of the total discharges), were discarded. These interspike intervals correspond to instantaneous discharge rates that are uncommon during steady contractions (Bigland and Lippold 1954; De Luca et al. 1982; Moritz et al. 2005; Pascoe et al. 2011) and thus presumably corresponded to decomposition errors. Instantaneous and average discharge rate were then computed for each identified motor unit, together with the coefficient of variation for the interspike intervals.

The neural drive to muscle was assessed from the low-frequency components of the composite discharge times by low-pass filtering of the composite spike train (CST) with a 400-ms Hanning window (De Luca 1985) and detrending of the output. The detrended signal produces the force oscillations and therefore represents the (common) noise in the input with respect to force generation. The variability of this signal, which we refer to as “common noise,” was quantified by its standard deviation (SD; square root of the signal power). In this way, a basic model of input to motor neurons during a constant-force contraction was specified as follows (Castronovo et al. 2015a):

| (1) |

where vi(t) is the net synaptic current received by the pool of N (i = 1…N) motor neurons that depends on μi, the constant offset determining the target force level (constant force), sC(t), the common oscillatory input to all motor neurons with a scaling factor αi specific for each motor neuron, and ni(t), the independent input for each motor neuron. According to this simple model, the fluctuations in force during the contraction can be attributed only to the varying term sC(t), as all the other components are filtered out in the averaging process.

According to the model in Eq. 1, the common component transmitted to the CST comprises a constant part, which corresponds to the generation of the target force (common control signal), and a variable part, which generates the fluctuations around the target force (common noise). The common component of the synaptic input was assumed to be transmitted approximately linearly by the motor neuron pool to form the CST (Negro and Farina 2011), whereas the independent component was attenuated by averaging the CST.

The neural drive to muscle was further assessed in the full-frequency bandwidth by coherence analysis between motor unit discharge times (Farmer et al. 1993). This was accomplished by computing coherence functions between the CSTs for groups of motor units. Coherence estimates increase monotonically with the number of motor units used to derive each CST (Castronovo et al. 2015b; Farina et al. 2012; Negro et al. 2016b), with a rate of change that depends on the ratio between the common and independent components of the synaptic input. Therefore, we analyzed the rate of increase in coherence peaks for CSTs based on one pair of motor units or two groups of five motor units (Negro et al. 2016b). Coherence was computed in all cases with nonoverlapping 1-s Hanning windows. Coherence values (C) were then averaged across 100 permutations of motor units and transformed to standard z score by first converting them to Fisher’s values [] and then normalizing them to the variance of estimation [, where L is the number of segments used to calculate coherence in the absence of overlapping]. The coherence estimate bias was identified as the average coherence in the frequency range 100–250 Hz (Baker et al. 2003) and subtracted from the coherence functions. Coherence profiles were then analyzed in the delta (1–5 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (13−21 Hz), and gamma (32–100 Hz) bands.

Force traces for each subject were resampled at 1,000 samples/s to match the sampling rate of the discharge times. Force steadiness was quantified as both the SD and the coefficient of variation (SD divided by mean, in %) for force.

Statistical analysis.

Discharge rate and coefficient of variation for interspike interval were expressed as the average ± SD across the identified motor units for each subject. A linear regression analysis was performed to investigate the associations between age and discharge rate, interspike interval variability, force oscillations, coherence magnitude at different frequency bands, and variability of common synaptic input. The same analysis was also performed to examine the relation between coherence peaks and number of motor units used for coherence analysis, in each frequency band. A Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to assess the difference in coherence magnitude when using one pair of motor units or two groups of five motor units in each frequency band. Significance level was set for P values < 0.05.

RESULTS

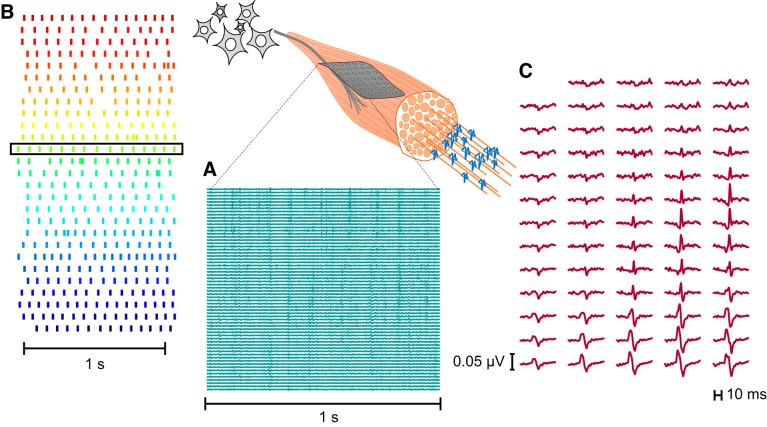

A total of 356 motor units were identified from the 20 subjects (18 ± 4 motor units per subject; Table 1). Figure 1 shows an example of a 64-channel high-density EMG signal and its decomposition recorded from a representative subject. The interference EMG is separated into its neural component (Fig. 1B) and its muscular action potentials (Fig. 1C).

Table 1.

Discharge rate, coefficient of variation for ISI, and number of motor units decomposed from EMG for all subjects

| Subject ID | Age, yr | Discharge Rate, pps | Coefficient of Variation for ISI, % | No. of MUs Decomposed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S01 | 24 | 12.3 ± 1.1 | 18.0 ± 6.3 | 11 |

| S02 | 25 | 13.2 ± 1.1 | 26.4 ± 7.4 | 12 |

| S03 | 29 | 11.8 ± 1.2 | 16.3 ± 4.4 | 24 |

| S04 | 29 | 9.4 ± 0.8 | 12.4 ± 2.2 | 19 |

| S05 | 30 | 9.9 ± 1.2 | 11.7 ± 4.2 | 18 |

| S06 | 31 | 11.7 ± 1.2 | 16.2 ± 4.1 | 15 |

| S07 | 31 | 11.1 ± 1.0 | 15.9 ± 4.5 | 22 |

| S08 | 34 | 11.3 ± 1.2 | 21.2 ± 3.9 | 14 |

| S09 | 35 | 12.2 ± 0.9 | 22.4 ± 8.5 | 14 |

| S10 | 40 | 11.4 ± 1.2 | 16.5 ± 5.3 | 16 |

| S11 | 46 | 10.2 ± 1.2 | 17.7 ± 6.7 | 27 |

| S12 | 51 | 11.7 ± 0.9 | 16.0 ± 2.8 | 19 |

| S13 | 51 | 10.8 ± 1.7 | 18.2 ± 2.3 | 16 |

| S14 | 52 | 10.3 ± 1.1 | 19.2 ± 2.7 | 20 |

| S15 | 63 | 9.4 ± 1.0 | 15.5 ± 3.3 | 17 |

| S16 | 68 | 13.4 ± 1.5 | 14.4 ± 2.3 | 25 |

| S17 | 69 | 10.7 ± 1.1 | 14.6 ± 1.5 | 15 |

| S18 | 72 | 10.4 ± 1.5 | 18.8 ± 5.8 | 21 |

| S19 | 74 | 11.7 ± 1.8 | 30.7 ± 5.4 | 13 |

| S20 | 75 | 11.1 ± 1.4 | 25.2 ± 3.3 | 18 |

| Average ± SD | 46.4 ± 18.1 | 11.2 ± 1.1 | 18.4 ± 4.8 | 18.0 ± 4.3 |

Discharge rates and coefficients of variation for interspike interval (ISI) are presented as average ± SD across the motor neuron pool for each subject, listed in order of increasing age. Number of decomposed motor units (MUs) is the total number for each subject.

Fig. 1.

Identification of motor unit action potentials and discharge times from high-density surface EMG. A: a 64-electrode grid was attached to the skin over tibialis anterior to record EMG signals. B: exact discharge times of motor neurons were estimated by blind-source separation from multichannel EMG recordings. Each row represents a motor neuron, and each vertical line denotes the time at which an action potential was discharged. C: multichannel motor unit action potential waveform for one of the identified motor units. Discharge time of the corresponding motor neuron is indicated by the black box in B.

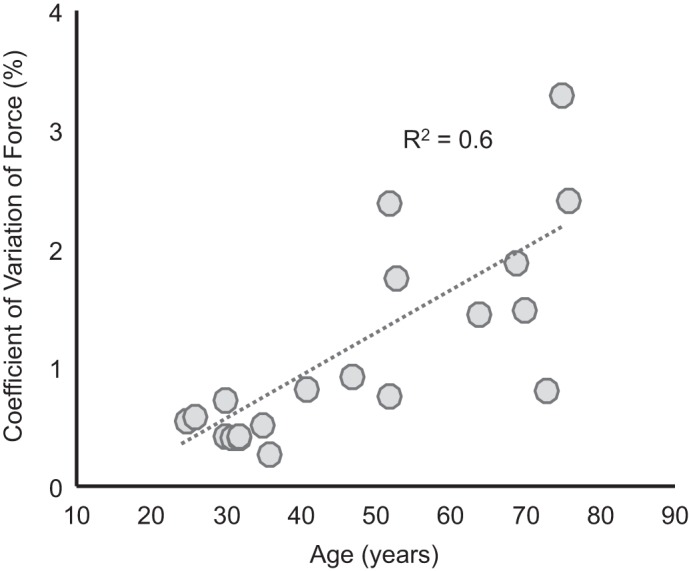

Force steadiness decreased with age (R2 = 0.6, P < 0.001; Fig. 2). However, neither motor neuron discharge rate nor the coefficient of variation for interspike interval was associated with age (R2 = 0.02, P = 0.5 and R2 = 0.09, P = 0.2, respectively). Table 1 lists the discharge characteristics of the identified motor units for each subject.

Fig. 2.

Force steadiness declines with age: coefficient of variation for force as a function of age. Dotted line represents linear fit to the data (R2 = 0.6, P < 0.001).

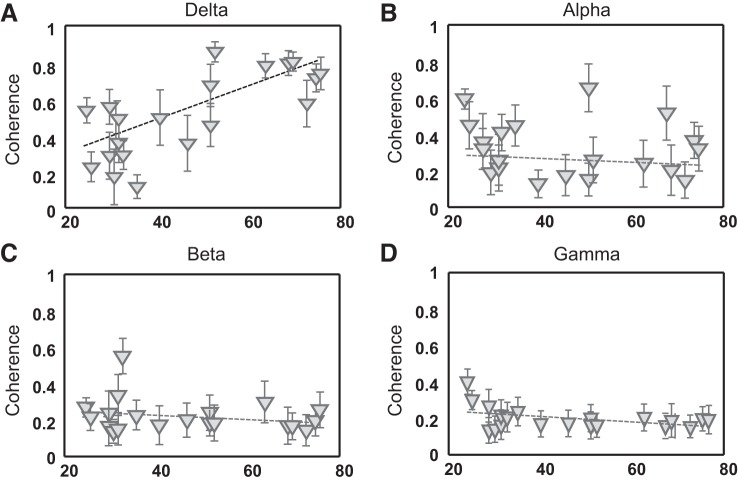

The influence of age on the neural drive to tibialis anterior was assessed in the frequency domain through coherence analysis. The analysis was performed with either pairs of motor units or two groups of five motor units. Figure 3 shows the association between age and coherence peak values in the four frequency bands analyzed for the groups of five motor units. The magnitude of coherence was significantly greater for all frequency bands when using five motor units in each group (average magnitude: delta 0.5 ± 0.2, alpha 0.3 ± 0.2, beta 0.2 ± 0.1, gamma 0.1 ± 0.1) with respect to motor unit pairs (average magnitude: delta 0.24 ± 0.15, alpha 0.1 ± 0.04, beta 0.06 ± 0.02, gamma 0.05 ± 0.01) (P < 0.001). This finding indicates the presence of common synaptic input to the pool of motor neurons for all frequencies in the subject sample (Negro et al. 2016b). The results with pairs or groups of five motor units were consistent for the delta band, indicating an increase in coherence magnitude with age (motor unit pairs: R2 = 0.6, P < 0.001; groups of 5 motor units: R2 = 0.6, P < 0.001). Conversely, a decrease in the gamma band coherence was only significant for the two groups of five motor units (R2 = 0.2, P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Coherence magnitude changes with age. Average (SD) peak coherence values over 100 permutations are reported as a function of age when using 2 groups of 5 motor units for its calculation. Coherence peaks are reported for 4 frequency bands: delta (1–5 Hz; A), alpha (8–12 Hz; B), beta (13–31 Hz; C), gamma (32–100 Hz; D). Dashed lines represent the linear regression for each data set.

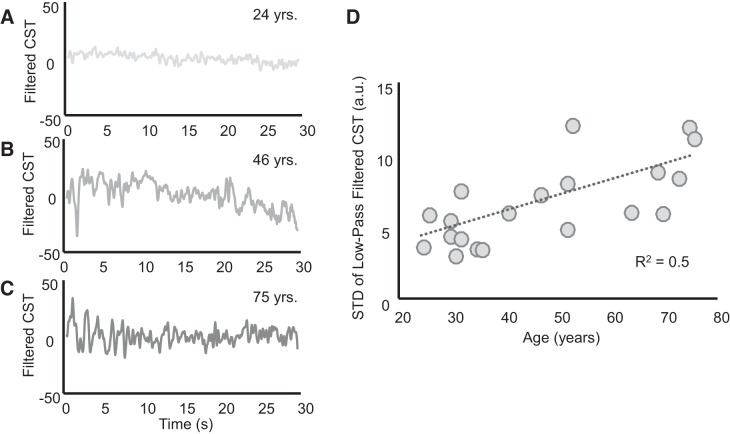

From a functional perspective (Boonstra et al. 2016), the shared synaptic input to motor neurons comprises an ideal control signal that would match the target force exactly and common noise, which determines the force fluctuations around the target. Both shared inputs are effectively transmitted into the discharge times of the motor units (as graphically represented in Fig. 2 of Farina and Negro 2015). This distribution of input has also been expressed mathematically (e.g., Castronovo et al. 2015a). When performing a steady isometric contraction, the target force is constant and therefore the control signal corresponds to the shared input that determines the DC component of the neural drive to the muscle. If only this component was present, the applied force would match the target exactly, corresponding to the low-pass filtered version of the neural drive to the muscle (Farina et al. 2016; Farina and Negro 2015). Conversely, the force fluctuations are due to the remaining frequency components of the neural drive, which we have termed common noise. Importantly, these statements refer to a functional analysis of the input-output of the motor neurons, which is the only type of analysis possible given the available measurements, and are not intended to represent specific anatomical pathways that determine the shared input (Boonstra et al. 2016). Figure 4, A–C, show representative examples of variability in the neural drive (due to common input fluctuations) to the muscle (tibialis anterior) for three subjects of different ages. In these examples, the magnitude of the fluctuations increases with age. Across all subjects, there was a positive relation between the magnitude (SD) of the common input fluctuations and age (R2 = 0.5, P < 0.001; Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Variability of low-frequency oscillations of the neural drive to muscle increases with age. The effective neural drive to the muscle was estimated by low-pass filtering the composite spike trains (CSTs) of the identified motor neurons. This filtered signal corresponds to an estimate of the common synaptic input that the motor neurons receive (Farina et al. 2016). A–C: filtered and detrended composite discharge times for 3 subjects of different ages. D: common noise [standard deviation (STD) of the filtered and detrended CST] increased as a function of age (R2 = 0.5, P < 0.001). a.u., Arbitrary units.

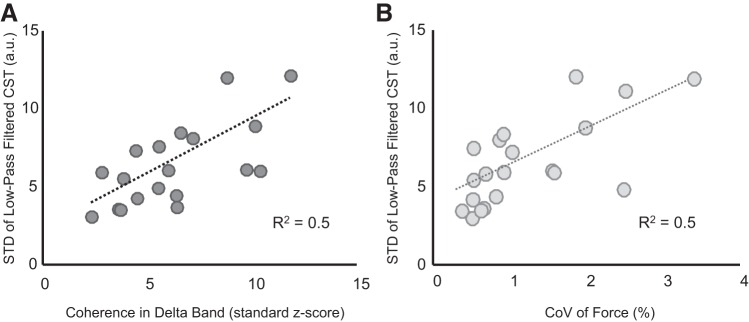

The relation between the age-associated increases in coherence in the delta band and the variability in the neural drive to muscle was quantified with a correlation analysis. Figure 5A shows a significant positive association (R2 = 0.5, P < 0.001), indicating that the increase in low-frequency (delta band) coherence between motor unit spike trains was correlated with increased power of the common input rather than decreased independent noise. The power of the fluctuations of the neural drive also directly influenced force steadiness, as indicated by a significant positive relation between the coefficient of variation for force and the variability of the neural drive to the muscle (R2 = 0.5, P < 0.001; Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Association between coherence in the low-frequency band and force steadiness. The effective neural drive to the muscle was estimated by low-pass filtering the composite spike trains (CSTs) of the identified motor neurons. The association between variability in neural drive (due to common input fluctuations) with coherence magnitude in the delta band (A) and with coefficient of variation (CoV) for force (B) is shown. A: the positive linear association (R2 = 0.5, P < 0.001) suggests that the observed increase in coherence magnitude at low frequencies was due to the increased variability of the common input. B: the positive linear association (R2 = 0.5, P < 0.001) indicates that the increasing power of low-frequency oscillations of the neural drive (due to common input fluctuations) was directly related to force steadiness.

Finally, the coefficient of variation for the interspike interval was associated with the variability of common input in the delta band (R2 = 0.3, P < 0.05) but not with the coefficient of variation for force (R2 = 0.2, P = 0.1). Indeed, the common input that determines force fluctuations influences the variability of the interspike interval only in a narrow band (i.e., delta band). The weak association between variability of interspike interval and of common input in the delta band is due to the fact that t interspike interval variability depends on the full-frequency bandwidth of the input, including the delta band, which is a small part of the neural drive bandwidth.

DISCUSSION

We investigated age-related changes in common synaptic input to motor neurons innervating the tibialis anterior muscle during isometric contractions. The main findings were that the decrease in force steadiness with advancing age was associated with an increase in low-frequency common synaptic input, but not independent synaptic noise, received by the motor neuron pool. Moreover, we observed a significant decrease, although it was a weak association, with age in the magnitude of coherence at higher frequencies (gamma band).

The ability to match a target force during an isometric contraction decreased with age (Fig. 2), which is consistent with previous observations (Enoka et al. 2003; Fox et al. 2013; Laidlaw et al. 2000; Ofori et al. 2010; Tracy 2007). However, in contrast to some previous studies (Semmler et al. 2000; Tracy et al. 2005), our results indicate that age-related differences in force steadiness were not associated with either discharge rate or coefficient of variation for interspike interval. One feature of our study that differed from earlier studies is that we enrolled participants with a continuous distribution of ages (24–75 yr) rather than discrete groups of young and old adults. Nonetheless, our results clearly demonstrate that the coefficient of variation for force during steady isometric contractions was not associated with the instantaneous variations in discharge of individual motor units. Since these are mainly due to independent input to each motor neuron, we conclude that independent synaptic noise to the motor neurons did not change with age and did not influence force variability. Rather, it was the common (not independent) variability in interspike interval exhibited by the activated motor units that was the primary determinant of force accuracy (Farina et al. 2016).

Coherence between motor unit discharge times in the delta band increased with age (Fig. 3A). The delta band reflects the variations in the neural drive to the muscle that impact force generation (De Luca and Erim 1994). Greater coherence values in the delta band underlie an increase in the ratio between the power of common and independent synaptic inputs (Farina and Negro 2015). An increase in coherence may therefore be due to either an increase in the oscillations (power) of common input or a decrease in power of the independent input. We identified the former as the main age-related effect, as the strength of coherence was positively associated with the variability of the neural drive in the delta band (Fig. 5). Conversely, we did not observe age-related changes in the instantaneous discharge variability of individual motor neurons, which is strongly influenced by independent input to the motor neurons (Dideriksen et al. 2012).

Collectively, our results show that aging mainly induces an increase in the common but not independent input to the motor neuron pool and that the fluctuations of the common input determine the impairment in force control (Jones et al. 2002; Sosnoff and Newell 2011). Therefore, the signal-dependent noise in force control (Enoka et al. 1999; Harris and Wolpert 1998; Jones et al. 2002) is derived from the common synaptic inputs to the motor neuron pool in the low-frequency bandwidth. The decrease in force steadiness observed for conditions such as fatiguing contractions (Castronovo et al. 2015a), nociceptive stimulation (Farina et al. 2012), and stroke (Castronovo et al. 2017), therefore, is also likely attributable to increased fluctuations of the common input to motor neurons.

We also observed a significant decrease in the strength of gamma oscillations with age (Fig. 3D), although the association with age was weaker than for the delta band. Gamma oscillations are thought to reflect activity in the primary motor cortex, supplementary motor cortex, and premotor cortex (Feige et al. 2000), especially during tasks that require attention, involve high-cognitive loads, or involve visual perception (Tallon-Baudry 2009; Womelsdorf et al. 2007). Gamma oscillations have also been extensively associated with perceptual processes (Böttger et al. 2002; Fries et al. 2001). Although the gamma components of the neural drive to muscle do not directly influence force because of their high frequency, they can be considered as markers of the cortical activity that determines the drive to the muscle in the force bandwidth. In our study, participants were asked to look at the screen placed in front of them and to carefully follow the target force. Even though the task was not cognitively challenging, it did require a certain level of attention. Therefore, age-associated decreases in the high-frequency components of the neural drive to muscle may have reflected an impairment in the cortical control that contributed to the augmented fluctuations of common input at lower frequencies (Kwon et al. 2012; Lodha and Christou 2017; Park et al. 2017). Because of the weak association between gamma coherence and age and the relatively small sample size in our study, however, this interpretation should be further tested in future studies.

We did not observe an effect of aging on coherence in the alpha and beta bands. The alpha band (up to 12 Hz) may be mainly related to afferent activity (Conway et al. 1995; Vallbo and Wessberg 1993) and recurrent inhibition (Williams and Baker 2009), whereas the beta band (up to 30 Hz) likely reflects the oscillatory activity in the corticospinal pathways (Conway et al. 1995; Farmer et al. 1993; Salenius et al. 1997). There is no consensus on age-related modifications in these frequency bands. Some studies have reported a decline in alpha oscillations with age (Böttger et al. 2002; Gola et al. 2012; Sewards and Sewards 1999), suggesting a relation between this frequency range and the decrease in visual awareness that is impaired in older adults (Sewards and Sewards 1999) . In contrast, some studies have shown changes in beta-band coherence during child development (Petersen et al. 2010) and across adulthood (Farmer et al. 2007; James et al. 2008) as a result of age-related improvements in the ability to control the ankle joint position, but others have reported no changes in the coherence between muscles in the same band (Graziadio et al. 2010; Jaiser et al. 2016; Semmler et al. 2003). When analyzing a broad range of ages, we found no association between age and the alpha/beta band oscillations in the neural drive to muscle. As for the gamma coherence, these results must be confirmed on a greater sample size in future studies. Moreover, the results were obtained at a single force level, and the observed effects of age may be different at other forces.

In discussing our results, we assumed that the neural drive to muscles is mainly determined by an approximately linear transmission of common synaptic input by the pool of motor neurons. From this assumption, we inferred that the common input responsible for force variability is in the low-frequency bandwidth and that fluctuations in the neural drive in this bandwidth reflected fluctuations in common input. Although this assumption of linearity is supported by simulation (Negro et al. 2009) and experimental evidence (Negro et al. 2016b), it cannot be excluded that high-frequency components of the common synaptic input involve some nonlinear demodulation into low-frequency components of the neural drive to muscle (i.e., nonlinear transmission of common input) (Watanabe and Kohn 2015). Even in the case of nonlinear transmission, however, an essential condition for the input to motor neurons to influence force generation is that it is shared across the motor neuron pool (Farina et al. 2016). Therefore, the main conclusion of this study remains valid: fluctuations in the common synaptic input to motor neuron pools correspond to variability in the neural drive to muscle that impairs force accuracy. Indeed, even in the case of nonlinear transmission of synaptic input, independent input to the motor neurons cannot influence force control (Watanabe and Kohn 2015).

In conclusion, aging is accompanied by an increase in low-frequency fluctuations of the neural drive to muscles that challenge the accuracy of force control. Moreover, our findings indicate that the decline in force accuracy is attributable to the augmented fluctuations in the common synaptic input to motor neurons rather than any independent synaptic input. Also, the power of the high-frequency (>30 Hz, gamma band) oscillations in the synaptic input to the motor neuron pool, which are of cortical origin, declines with advancing age. However, the source of the increase in the variability of common synaptic input remains to be determined.

GRANTS

This work was partly supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (grant agreement no. 660905), by the European Research Council (projects DEMOVE and Interspine), by the Obel Family Foundation in Denmark, by the Kong Christian den Tiendes Fond of Denmark, and by the Slovenian Research Agency (research core funding no. P2-0041 and project J2-7357).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.M.C., N.M.-K., and D.F. conceived and designed research; A.M.C. performed experiments; A.M.C. and D.F. analyzed data; A.M.C., N.M.-K., A.J.T.S., A.H., R.M.E., and D.F. interpreted results of experiments; A.M.C. prepared figures; A.M.C., R.M.E., and D.F. drafted manuscript; A.M.C., N.M.-K., A.J.T.S., A.H., R.M.E., and D.F. edited and revised manuscript; A.M.C., N.M.-K., A.J.T.S., A.H., R.M.E., and D.F. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Baker SN, Pinches EM, Lemon RN. Synchronization in monkey motor cortex during a precision grip task. II. Effect of oscillatory activity on corticospinal output. J Neurophysiol 89: 1941–1953, 2003. doi: 10.1152/jn.00832.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldissera F, Cavallari P, Cerri G. Motoneuronal pre-compensation for the low-pass filter characteristics of muscle. A quantitative appraisal in cat muscle units. J Physiol 511: 611–627, 1998. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.611bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry BK, Pascoe MA, Jesunathadas M, Enoka RM. Rate coding is compressed but variability is unaltered for motor units in a hand muscle of old adults. J Neurophysiol 97: 3206–3218, 2007. doi: 10.1152/jn.01280.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigland B, Lippold OC. Motor unit activity in the voluntary contraction of human muscle. J Physiol 125: 322–335, 1954. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birren JE, Schaie KW, Klaus W, Abeles RP, Gatz M, Salthouse TA. Handbook of the Psychology of Aging. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boonstra TW, Farmer SF, Breakspear M. Using computational neuroscience to define common input to spinal motor neurons. Front Hum Neurosci 10: 313, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttger D, Herrmann CS, von Cramon DY. Amplitude differences of evoked alpha and gamma oscillations in two different age groups. Int J Psychophysiol 45: 245–251, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8760(02)00031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WF. A method for estimating the number of motor units in thenar muscles and the changes in motor unit count with ageing. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 35: 845–852, 1972. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.35.6.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castronovo AM, Negro F, Conforto S, Farina D. The proportion of common synaptic input to motor neurons increases with an increase in net excitatory input. J Appl Physiol 119: 1337–1346, 2015a. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00255.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castronovo AM, Negro F, Farina D. Theoretical model and experimental validation of the estimated proportions of common and independent input to motor neurons. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2015: 254–257, 2015b. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2015.7318348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castronovo M, Mrachacz-Kersting N, Landi F, Jørgensen H, Severinsen K, Farina D. Motor unit coherence at low frequencies increases together with cortical excitability following a brain-computer interface intervention in acute stroke patients. In: Converging Clinical and Engineering Research on Neurorehabilitation II: Proceedings of ICNR 2016, edited by Ibáñez J, Gonzalez-Vargas J, Azorín JM, Akay M, Pons JL. Berlin: Springer, 2017, p. 1001–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly DM, Rice CL, Roos MR, Vandervoort AA. Motor unit firing rates and contractile properties in tibialis anterior of young and old men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 87: 843–852, 1999. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.2.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway BA, Farmer SF, Halliday DM, Rosenberg JR. On the relation between motor-unit discharge and physiological tremor. In: Alpha and Gamma Motor Systems, edited by Durbaba R, Gladden MH, Taylor A. New York: Springer, 1995, p. 596–598. [Google Scholar]

- Datta AK, Stephens JA. Synchronization of motor unit activity during voluntary contraction in man. J Physiol 422: 397–419, 1990. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp017991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayanidhi S, Valero-Cuevas FJ. Dexterous manipulation is poorer at older ages and is dissociated from decline of hand strength. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 69: 1139–1145, 2014. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca CJ. Control properties of motor units. J Exp Biol 115: 125–136, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca CJ, Erim Z. Common drive of motor units in regulation of muscle force. Trends Neurosci 17: 299–305, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca CJ, LeFever RS, McCue MP, Xenakis AP. Behaviour of human motor units in different muscles during linearly varying contractions. J Physiol 329: 113–128, 1982. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dideriksen JL, Negro F, Enoka RM, Farina D. Motor unit recruitment strategies and muscle properties determine the influence of synaptic noise on force steadiness. J Neurophysiol 107: 3357–3369, 2012. doi: 10.1152/jn.00938.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoka RM, Burnett RA, Graves AE, Kornatz KW, Laidlaw DH. Task- and age-dependent variations in steadiness. Prog Brain Res 123: 389–395, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)62873-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoka RM, Christou EA, Hunter SK, Kornatz KW, Semmler JG, Taylor AM, Tracy BL. Mechanisms that contribute to differences in motor performance between young and old adults. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 13: 1–12, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S1050-6411(02)00084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erim Z, Beg MF, Burke DT, de Luca CJ. Effects of aging on motor-unit control properties. J Neurophysiol 82: 2081–2091, 1999. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.5.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina D, Negro F. Common synaptic input to motor neurons, motor unit synchronization, and force control. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 43: 23–33, 2015. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina D, Negro F, Dideriksen JL. The effective neural drive to muscles is the common synaptic input to motor neurons. J Physiol 592: 3427–3441, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.273581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina D, Negro F, Gizzi L, Falla D. Low-frequency oscillations of the neural drive to the muscle are increased with experimental muscle pain. J Neurophysiol 107: 958–965, 2012. doi: 10.1152/jn.00304.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina D, Negro F, Muceli S, Enoka RM. Principles of motor unit physiology evolve with advances in technology. Physiology (Bethesda) 31: 83–94, 2016. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00040.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer SF, Bremner FD, Halliday DM, Rosenberg JR, Stephens JA. The frequency content of common synaptic inputs to motoneurones studied during voluntary isometric contraction in man. J Physiol 470: 127–155, 1993. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer SF, Gibbs J, Halliday DM, Harrison LM, James LM, Mayston MJ, Stephens JA. Changes in EMG coherence between long and short thumb abductor muscles during human development. J Physiol 579: 389–402, 2007. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.123174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feige B, Aertsen A, Kristeva-Feige R. Dynamic synchronization between multiple cortical motor areas and muscle activity in phasic voluntary movements. J Neurophysiol 84: 2622–2629, 2000. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.5.2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fling BW, Christie A, Kamen G. Motor unit synchronization in FDI and biceps brachii muscles of strength-trained males. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 19: 800–809, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox EJ, Baweja HS, Kim C, Kennedy DM, Vaillancourt DE, Christou EA. Modulation of force below 1 Hz: age-associated differences and the effect of magnified visual feedback. PLoS One 8: e55970, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P, Reynolds JH, Rorie AE, Desimone R. Modulation of oscillatory neuronal synchronization by selective visual attention. Science 291: 1560–1563, 2001. doi: 10.1126/science.1055465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galganski ME, Fuglevand AJ, Enoka RM. Reduced control of motor output in a human hand muscle of elderly subjects during submaximal contractions. J Neurophysiol 69: 2108–2115, 1993. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.6.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gola M, Kamiński J, Brzezicka A, Wróbel A. β Band oscillations as a correlate of alertness—changes in aging. Int J Psychophysiol 85: 62–67, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziadio S, Basu A, Tomasevic L, Zappasodi F, Tecchio F, Eyre JA. Developmental tuning and decay in senescence of oscillations linking the corticospinal system. J Neurosci 30: 3663–3674, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5621-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris CM, Wolpert DM. Signal-dependent noise determines motor planning. Nature 394: 780–784, 1998. doi: 10.1038/29528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holobar A, Zazula D. Multichannel blind source separation using convolution kernel compensation. IEEE Trans Signal Process 55: 4487–4496, 2007. doi: 10.1109/TSP.2007.896108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiser SR, Baker MR, Baker SN. Intermuscular coherence in normal adults: variability and changes with age. PLoS One 11: e0149029, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LM, Halliday DM, Stephens JA, Farmer SF. On the development of human corticospinal oscillations: age-related changes in EEG-EMG coherence and cumulant. Eur J Neurosci 27: 3369–3379, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KE, Hamilton AF, Wolpert DM. Sources of signal-dependent noise during isometric force production. J Neurophysiol 88: 1533–1544, 2002. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallio J, Søgaard K, Avela J, Komi P, Selänne H, Linnamo V. Age-related decreases in motor unit discharge rate and force control during isometric plantar flexion. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 22: 983–989, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen DA, Fuglevand AJ. Common input to motor neurons innervating the same and different compartments of the human extensor digitorum muscle. J Neurophysiol 91: 57–62, 2004. doi: 10.1152/jn.00650.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M, Baweja HS, Christou EA. Ankle variability is amplified in older adults due to lower EMG power from 30-60 Hz. Hum Mov Sci 31: 1366–1378, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw DH, Bilodeau M, Enoka RM. Steadiness is reduced and motor unit discharge is more variable in old adults. Muscle Nerve 23: 600–612, 2000. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine CM, Martinez-Valdes E, Falla D, Mayer F, Farina D. Motor neuron pools of synergistic thigh muscles share most of their synaptic input. J Neurosci 35: 12207–12216, 2015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0240-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence DG, Porter R, Redman SJ. Corticomotoneuronal synapses in the monkey: light microscopic localization upon motoneurons of intrinsic muscles of the hand. J Comp Neurol 232: 499–510, 1985. doi: 10.1002/cne.902320407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodha N, Christou EA. Low-frequency oscillations and control of the motor output. Front Physiol 8: 78, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil CJ, Doherty TJ, Stashuk DW, Rice CL. Motor unit number estimates in the tibialis anterior muscle of young, old, and very old men. Muscle Nerve 31: 461–467, 2005. doi: 10.1002/mus.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon H, Kim C, Kwon M, Chen YT, Onushko T, Lodha N, Christou EA. Force control is related to low-frequency oscillations in force and surface EMG. PLoS One 9: e109202, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz CT, Barry BK, Pascoe MA, Enoka RM. Discharge rate variability influences the variation in force fluctuations across the working range of a hand muscle. J Neurophysiol 93: 2449–2459, 2005. doi: 10.1152/jn.01122.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negro F, Farina D. Linear transmission of cortical oscillations to the neural drive to muscles is mediated by common projections to populations of motoneurons in humans. J Physiol 589: 629–637, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.202473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negro F, Holobar A, Farina D. Fluctuations in isometric muscle force can be described by one linear projection of low-frequency components of motor unit discharge rates. J Physiol 587: 5925–5938, 2009. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.178509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negro F, Muceli S, Castronovo AM, Holobar A, Farina D. Multi-channel intramuscular and surface EMG decomposition by convolutive blind source separation. J Neural Eng 13: 026027, 2016a. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/13/2/026027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negro F, Yavuz UŞ, Farina D. The human motor neuron pools receive a dominant slow-varying common synaptic input. J Physiol 594: 5491–5505, 2016b. doi: 10.1113/JP271748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofori E, Samson JM, Sosnoff JJ. Age-related differences in force variability and visual display. Exp Brain Res 203: 299–306, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2229-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Casamento-Moran A, Yacoubi B, Christou EA. Voluntary reduction of force variability via modulation of low-frequency oscillations. Exp Brain Res 235: 2717–2727, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00221-017-5005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe MA, Holmes MR, Enoka RM. Discharge characteristics of biceps brachii motor units at recruitment when older adults sustained an isometric contraction. J Neurophysiol 105: 571–581, 2011. doi: 10.1152/jn.00841.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen TH, Kliim-Due M, Farmer SF, Nielsen JB. Childhood development of common drive to a human leg muscle during ankle dorsiflexion and gait. J Physiol 588: 4387–4400, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.195735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salenius S, Portin K, Kajola M, Salmelin R, Hari R. Cortical control of human motoneuron firing during isometric contraction. J Neurophysiol 77: 3401–3405, 1997. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.6.3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semmler JG, Kornatz KW, Enoka RM. Motor-unit coherence during isometric contractions is greater in a hand muscle of older adults. J Neurophysiol 90: 1346–1349, 2003. doi: 10.1152/jn.00941.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semmler JG, Nordstrom MA. Motor unit discharge and force tremor in skill- and strength-trained individuals. Exp Brain Res 119: 27–38, 1998. doi: 10.1007/s002210050316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semmler JG, Steege JW, Kornatz KW, Enoka RM. Motor-unit synchronization is not responsible for larger motor-unit forces in old adults. J Neurophysiol 84: 358–366, 2000. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewards TV, Sewards MA. Alpha-band oscillations in visual cortex: part of the neural correlate of visual awareness? Int J Psychophysiol 32: 35–45, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8760(98)00062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderberg GL, Minor SD, Nelson RM. A comparison of motor unit behaviour in young and aged subjects. Age Ageing 20: 8–15, 1991. doi: 10.1093/ageing/20.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosnoff JJ, Newell KM. Aging and motor variability: a test of the neural noise hypothesis. Exp Aging Res 37: 377–397, 2011. doi: 10.1080/0361073X.2011.590754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallon-Baudry C. The roles of gamma-band oscillatory synchrony in human visual cognition. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 14: 321–332, 2009. doi: 10.2741/3246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AM, Christou EA, Enoka RM. Multiple features of motor-unit activity influence force fluctuations during isometric contractions. J Neurophysiol 90: 1350–1361, 2003. doi: 10.1152/jn.00056.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy BL. Force control is impaired in the ankle plantarflexors of elderly adults. Eur J Appl Physiol 101: 629–636, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00421-007-0538-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy BL, Maluf KS, Stephenson JL, Hunter SK, Enoka RM. Variability of motor unit discharge and force fluctuations across a range of muscle forces in older adults. Muscle Nerve 32: 533–540, 2005. doi: 10.1002/mus.20392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt DE, Larsson L, Newell KM. Effects of aging on force variability, single motor unit discharge patterns, and the structure of 10, 20, and 40 Hz EMG activity. Neurobiol Aging 24: 25–35, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallbo AB, Wessberg J. Organization of motor output in slow finger movements in man. J Physiol 469: 673–691, 1993. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe RN, Kohn AF. Fast oscillatory commands from the motor cortex can be decoded by the spinal cord for force control. J Neurosci 35: 13687–13697, 2015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1950-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ER, Baker SN. Renshaw cell recurrent inhibition improves physiological tremor by reducing corticomuscular coupling at 10 Hz. J Neurosci 29: 6616–6624, 2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0272-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womelsdorf T, Fries P. The role of neuronal synchronization in selective attention. Curr Opin Neurobiol 17: 154–160, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]