Abstract

Aberrant degradation of proteins is associated with many pathological states, including cancers. Mass spectrometric analysis of the tumor peptidome has the potential to provide biological insights on proteolytic processing in cancer. However, attempts to use the tumors peptidome information in cancer research have been fairly limited to date, largely due to the lack of effective approaches for robust peptidomics identification and quantification, and the prevalence of confounding factors and biases associated with sample handling and processing. To address this need, we have recently developed an effective and robust analytical platform as well as a novel informatics approach for comprehensive analyses of tissue peptidomes. The ability of this new peptidomics pipeline for high-throughput, comprehensive, and quantitative peptidomics analysis, as well as the suitability of clinical ovarian tumor samples with postexcision delay limited to less than 60min before freezing for peptidomics analysis, has been demonstrated. These initial analyses set a stage for further determination of molecular details and functional significance of the peptidomic activities in ovarian cancer.

1. INTRODUCTION

By avoiding the digestion of proteins into peptides, as applied in conventional bottom-up proteomics, peptidomics can provide otherwise unobtainable insights on posttranslational modifications (PTMs) and endogenous proteolytic products. For example, our recent study of blood plasma peptidome revealed strikingly different peptidomics profiles between samples from breast cancer (BrCa) patients and healthy controls, despite the very similar bottom-up proteomic profiles, showing the potential of peptidomics to reveal endogenous proteolytic processing information to which conventional bottom-up proteomics is effectively blind (Shen, Tolic, et al., 2010). Recent studies in cell lines have also identified proteolytic products of intracellular and intercellular proteins that appear to be stable bioactive molecules with explicit roles in cellular signaling pathways, rather than simple transient protein degradation products (Cunha et al., 2008; Gelman, Sironi, Castro, Ferro, & Fricker, 2011). Therefore, peptidomics provides important insights into the activity of various endogenous proteases, as well as potential information on other biologically active peptides (Lopez-Otin & Overall, 2002; Villanueva et al., 2006). Broad- and large-scale peptidomics studies using advanced liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) have been increasingly conducted to characterize endogenous peptides in different biological samples, including cell lines (Fricker, Gelman, Castro, Gozzo, & Ferro, 2012; Gelman et al., 2011), body fluids (Fiedler et al., 2007; Villanueva et al., 2006), as well as tissues (Xu et al., 2015), for biomarker screening or clinically related studies.

Interpreting the significance of the peptidomic components identified from clinical tissue samples in a biological context is also of biomedical interest, and particularly the ability to differentiate between specific regulated events that convey biological information and more general protein degradation. Identifying the natural proteases and their associated pathways in clinical tissue samples and exploring the biological significance of the pro-tease/substrate interaction has the potential to provide novel insights into the mechanisms of molecular tumor pathology (Shahinian et al., 2013). To achieve this goal, it is desirable that the peptidomics pipeline provides comprehensive peptidome coverage and robust quantification, which is dependent on each step of the pipeline, including peptide extraction and/or enrichment/fractionation, separation, LC-MS data acquisition, as well as the subsequent informatics analysis (Tinoco & Saghatelian, 2011). Other issues related to peptidomics analysis of clinical samples, e.g., the ability to efficiently extract the full repertoire of peptides from complicated clinical tissue samples while maintaining the “original” status of the samples (e.g., avoiding potential confounding factors), also need to be considered. For example, postmortem stability is potentially problematic for peptidomic studies (Zhu & Desiderio, 1993), as are issues, associated with the handling of clinical samples, including degradation associated with postexcision delay, making it difficult to characterize the “true” peptidome of clinical tumor samples.

We have recently developed and applied a highly effective, label-free quantitative peptidomics pipeline to characterize the peptidomes in human ovarian cancer (OvCa) tumor samples. The ability of the platform to achieve highly reproducible measurements and comprehensive peptidomic coverage was demonstrated (Wu et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015). Compared to the conventional LC-MS/MS-based pipeline, the use of a novel LCMS-based informatics approach, informed quantification (IQ), provided not only significantly improved peptidome coverage but also dramatically reduced “missing values” across different sample analyses. In addition, analyses of tumor samples undergoing controlled postexcision delay of 5–60min showed little or no effect of warm ischemia time on peptidomes from the OvCa tumors, an important observation supporting the utility of peptidomic approaches. In line with other observations, the proteasome was observed as the potential major contributor to human OvCa tumor peptidomes (Xu et al., 2015). These results demonstrate that robust quantitative peptidomics analysis can be effectively performed on clinical tumor samples using our peptidomics platform. We anticipate continued application of this platform to further determine molecular details and functional significance of the peptidomic activities in cancers.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Ovarian Tumor Samples

Ovarian tumor tissues (FIGO stage IIIC or IV) were collected from three patients with high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma under IRB-approved protocols. Prior to performing primary tumor resection and before any compromise to the vascular supply, a portion of ovarian tumor attached to the omentum was rapidly resected. The tumor specimen was immediately dissected into four contiguous and adjacent specimens strips each no larger than 10×3×3mm, and placed into cryovials and frozen in liquid nitrogen at four different time points (0, 5, 30, and 60min, at room temperature). All specimens were then stored in −80°C freezers until cryopulverization using a Covaris CP02 Cryoprep device (Covaris, Woburn, MA). All procedures were carried out on dry ice to maintain tissue in a powdered, frozen state.

2.2. Sample Preparation

For peptide extraction, extraction buffer containing 0.25% acetic acid and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added into approximately 20mg (wet weight) pulverized OvCa tumor samples at a ratio of 1:10 (w:v). Mixed samples were homogenized on ice for 1min, sonicated with three short bursts of 10s followed by intervals of 5min for cooling on ice bed, and centrifuged at 4°C, 14,000× g for 30min. The supernatant was filtered in an Amicon Ultracel 30-kDa MWCO filter tube (Millipore, Billerica, MA) by centrifugation (4°C, 8000× g) to remove peptides larger than 30kDa. The flow-through was concentrated in Speed-Vac (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and its peptidome content was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

2.3. LC-MS/MS Analysis

The peptidomics samples were analyzed using nanoACQUITY UPLC® system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) coupled on-line to a LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). A 110cm×75μm i.d. (flow rate 200nL/min) fused-silica capillary column packed with 3-μm Jupiter C18 bonded particles (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) was used. Mobile phases consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid acetonitrile (B) were operated with effective gradient profile of (min:%B): 0:1, 6:8, 60:12, 225:35, 291:45, 300:95. The LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent mode acquiring high-resolution collision-induced dissociation (CID) scans (R =15,000, 5×104 target ions) after each full MS scan (R =60,000, 1×106 target ions) for the top six most abundant ions (400–2000 m/z). An isolation window of 2Th and a normalized collision energy of 35 were used for CID. The dynamic exclusion time was 60s.

2.4. Data Analysis

Peptide identification and quantification were carried out using the IQ approach as described previously (Wu et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015). Briefly, a comprehensive peptide database was first created by combining confident identifications (<1% false identification rate; precursor mass error less than 10ppm) derived from independent search of MS/MS spectra from all analyses using MS-GF+ (Kim & Pevzner, 2014), MS-Align+ (Liu et al., 2012), and the Unique Sequence Tags (Shen, Liu, et al., 2010) algorithms, respectively, against the human NCBI database (Build 37.3). IQ uses the m/z values of the theoretical isotopic profile derived based on the peptide sequences that were included in the peptide database to guide the extraction of the observed isotopic profile from the summed mass spectra in each individual analysis. Least-squares fitting of the theoretical isotopic profile on the observed profile is then performed (Jaitly et al., 2009). After alignment of mass and the LC elution time, the processed data were filtered by fit score (<0.1), normalized elution time tolerance (<2.5%), and mass accuracy (<10ppm), followed by manual validation to eliminate false positives (Slysz et al., 2014). The abundance from different charge states is added up for the specific peptide for quantification. For comparison, the data sets were also analyzed using the PNNL-developed accurate mass and time (AMT) tag approach (Smith et al., 2002; Zimmer, Monroe, Qian, & Smith, 2006) as previously described (Wu et al., 2015). The identified peptides from the IQ and AMT analyses were finally grouped to nonredundant protein lists using IDpicker3 (Holman, Ma, & Tabb, 2012).

The intensities of peptides were first Log10 transformed and then median normalized across all samples. Pearson correlation, unsupervised hierarchical clustering, and ANOVA and moderated F-test (for evaluating changes in the peptidome over time using a kinetics-based regression model) were performed in R using corresponding R packages (Xu et al., 2015); the resulting P-values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method.

The ProteinCoverageSummarizer tool developed in-house and corresponding protein databases were used to map the unique peptide sequences into proteins. The frequency of various amino acids within the cleavage site (P6–1, P1–6′) from all identified peptides was analyzed (Schechter & Berger, 1968). For each peptide, N- and C-terminal cleavage sites were analyzed as PX_Up and PX_Down, respectively, the frequencies of which were plotted together for individual P sites. Frequencies of amino acids at all 12 P sites were analyzed to identify potential proteases based on the protease cleavage rules which were adopted from the comprehensive publication by Keil (1992). Gene List Analysis was conducted using Panther (http://www.pantherdb.org/) to obtain biological information (e.g., function, pathway) of the precursor proteins.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Robust Characterization of the Tumor Peptidome

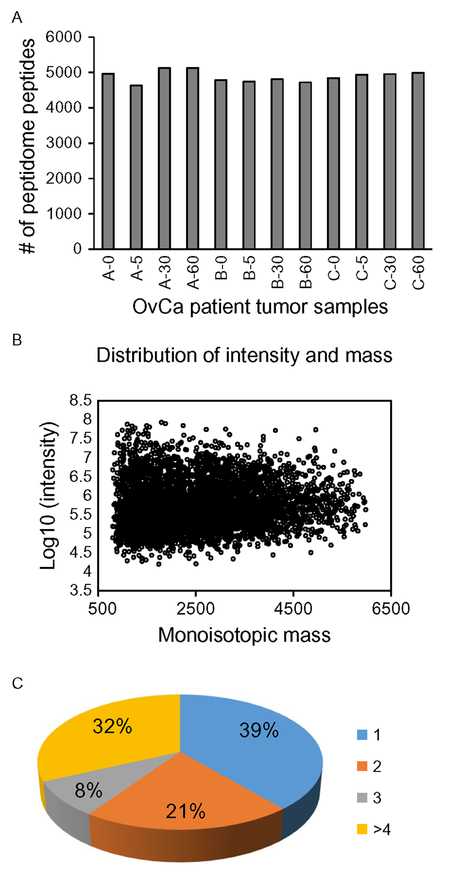

A total of 5756 distinct peptides ranging from 500 to ~6000Da (Fig. 1A) were identified and quantified (label-free) from analyses of 12 ovarian cancer tumor tissue samples (from three patients, each with four time points). The number of identified peptides was highly consistent across samples (4952±285; CV=5.8%) (Fig. 1B), demonstrating the good, consistent peptidome coverage of the analytical platform. These peptides were mapped into 974 distinct precursor proteins (peptidome peptides, their precursor proteins, and original peptide intensities from each ovarian tumor sample are available in supplemental table S2 of Xu et al., 2015); >60% of these proteins have more than one peptidome peptides identified (Fig. 1C). To our knowledge, our study represents the broadest characterization and first quantitative analysis of human cancer tumor peptidomes. This entire quantitative peptidomics platform encompassing sample preparation, LC-MS analysis, and data analysis provides a foundation for future peptidomics applications in biological and translational studies in cancer.

Fig. 1.

Summary of peptide identifications from OvCa tumor samples. Bar graphs show the numbers of identified peptides from each OvCa tumor (A). The intensities of identified peptides (Log10 values) from OvCa tumor samples were plotted against their monoisotopic masses (Da), showing a similar peptide intensity range but different mass ranges (B). The distributions of the precursor proteins in terms of number of unique peptidome peptide identifications are shown in pie graph (C). Modified with permission from Xu, Z., Wu, C., Xie, F., Slysz, G. W., Tolic, N., Monroe, M. E., et al. (2015). Comprehensive quantitative analysis of ovarian and breast cancer tumor peptidomes. Journal of Proteome Research, 14, 422–433, available at http://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/pr500840w. These figures are licensed under American Chemical Society (ACS) AuthorChoice, and further permission requests should be directed to the ACS.

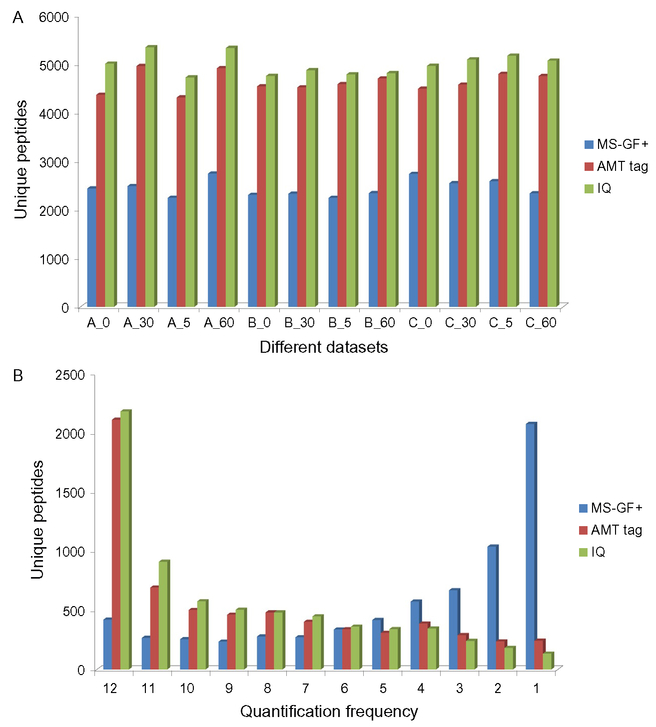

3.2. IQ Analysis Significantly Improves Data Quality

The OvCa peptidomics studies benefitted significantly from data analysis afforded by the new IQ approach. As an example, we compared the IQ analysis results of the OvCa data (LC-MS data) to those obtained through conventional analyses such as MS-GF+ (MS/MS data) and the AMT tag strategy (LC-MS data) (Wu et al., 2015). As expected, MS-GF+ suffers from the undersampling issue of typical data-dependent acquisition of MS/MS data and hence provided much lower peptidome coverage and less consistent results for each individual analysis (Fig. 2A). IQ and AMT tag analyses both use a database consisting of peptides identified from database search of all MS/MS spectra from the entire peptidomics datasets, yet IQ provided higher peptidome coverage, and more importantly, less missing data across the entire datasets (Fig. 2B). We attribute this to IQ using all isotopic peaks as opposed to the AMT tag method (Smith et al., 2002; Zimmer et al., 2006) which uses individually deisotoped spectra, resulting in improved sensitivity, better distinguished overlapping features, more accurate quantification, and better reproducibility.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of identification and quantification results from MS-GF+, AMT tag, and IQ analyses. (A) Comparison of number of identified unique peptides in each sample for MS-GF+ (blue), AMT (red), and IQ (green). (B) Distribution of quantification frequency among all samples for MS-GF+ (blue), AMT tag (red), and IQ (green). Adapted with permission from Wu, C., Monroe, M. E., Xu, Z., Slysz, G. W., Payne, S. H., Rodland, K. D., et al. (2015). An optimized informatics pipeline for mass spectrometry-based peptidomics. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 26, 2002–2008. These figures are licensed under Springer, and further permission requests should be directed to Springer.

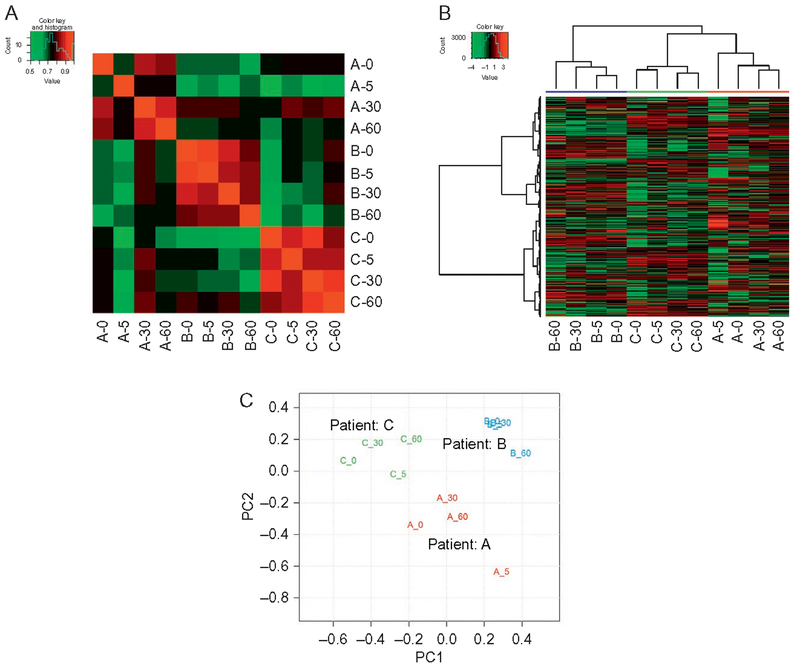

3.3. Negligible Effects From Postexcision Delay

Pearson correlation analysis, unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis, principle component analysis (PCA), and a kinetics-based regression analysis were performed to assess the ischemic effect on the OvCa tumor peptidome. Despite considerable overlap (95.4%) of the precursor proteins in all three patients (supplemental table S2 of Xu et al., 2015), the pairwise peptide intensities of all three patients were poorly correlated (Fig. 3A). In contrast, peptides of the four time point samples from the same patient showed much better correlation, supporting good reproducibility of the analytical platform and indicating that any potential ischemic effect on the peptidome is much smaller than the patient-to-patient difference. The clustering analysis (Fig. 3B) and PCA analysis (Fig. 3C) showed similar trends: the peptide intensity patterns changed significantly across the three patients, and the four time point samples for each patient had more similar peptidome profiles and were clustered together. The kinetics-based regression analysis results indicated that none of the peptides was significantly changing across the three patients as a result of 60-min ischemic stress (data not shown). Overall, results from all these analyses indicated that the ischemic effect contributing to variations in the OvCa tumor peptidome within the first 60min after excision, if any, is much less significant than that of patient heterogeneity. This is consistent with our previous observations from bottom-up proteomics analysis of the same set of OvCa tumor time course samples (Mertins et al., 2014), i.e., the overall protein abundance does not change significantly with up to 60min postexcision delay.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of the OvCa peptidome data demonstrated minimal ischemic effect within 60min of postexcision delay. (A) Pearson correlation, (B) unsupervised hierarchical clustering, and (C) PCA analyses of all OvCa tumor samples (four time point samples from each of the three patients). It is evident that potential ischemic effect on tumor peptidome as a result of up to 60min postexcision delay is much smaller than patient heterogeneity. Modified with permission from Xu, Z., Wu, C., Xie, F., Slysz, G. W., Tolic, N., Monroe, M. E., et al. (2015). Comprehensive quantitative analysis of ovarian and breast cancer tumor peptidomes. Journal of Proteome Research, 14, 422–433, available at http://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/pr500840w. These figures are licensed under American Chemical Society (ACS) AuthorChoice, and further permission requests should be directed to the ACS.

Peptidomics profiles have been previously reported as capable of discriminating cancer types such as breast, prostate, and bladder cancer, and healthy controls (Villanueva et al., 2006). We have also shown even two patient-derived xenografts derived from the same subtype of breast cancer (basal) can be clearly separated by their peptidomics profiles (Xu et al., 2015). In the case of OvCa, tumor peptidome samples from different patients were also clearly separated. These results suggest that tumor peptidomics profiles are sensitive to human pathophysical status and human heterogeneity, and not affected by the ischemia caused by postexcision delay (up to 60min as tested), and hence could provide highly valuable information on endogenous proteolytic events for cancer studies.

3.4. No Strong Correlation Between the OvCa Peptidome Peptides and the Abundance/Stability of Their Precursor Proteins

The OvCa peptidome precursor proteins were compared to the list of the most abundant proteins from our previous bottom-up study of the same OvCa tumors (Mertins et al., 2014). Of the 974 nonredundant protein groups identified in OvCa peptidome, 238 were among the 500 most abundant proteins in the OvCa tumors, and 34 of these 238 proteins were among the 50 most abundant proteins. Further comparing the distributions of the spectral counts of the peptidome precursor proteins and the entire list of protein identifications in the bottom-up studies (9498 proteins) showed that more than 25% of the OvCa peptidome precursor proteins are relatively low abundance proteins in the proteome. Moreover, the relative abundances for the same precursor protein in the proteome and peptidome do not correlate well (R2 <0.2; results not shown). There are many potentially interesting low abundance precursor proteins that were identified with multiple peptidome peptide identifications. By comparing the OvCa peptidome precursor proteins with the 600 proteins in A549 cell and 6000 proteins in Hela cell with the highest turnover rates (Boisvert et al., 2012; Doherty, Hammond, Clague, Gaskell, & Beynon, 2009), we found 67 matched proteins in the A549 cell study and 684 matched proteins in the Hela cell study. Only 5 precursor proteins were among the top 50 unstable proteins in A549 cell, and only 53 were among the top 500 category in Hela cell. Overall, our data suggest that there is no strong correlation between the peptides identified in OvCa peptidome and the abundance/stability of the proteins from which these peptides are derived.

The biological processes in which the precursor proteins are involved were analyzed using gene ontology. Approximately 25% of the 974 precursor proteins in ovarian cancer, representing the most prevalent proteolytic substrates, were participating in metabolic processes. The second largest group of peptidome precursor proteins (~15%) was relevant to the cellular processes including cellular component morphogenesis, neural development, and immune responses. The rest of the precursor proteins were participating in processes such as transport, cell communication, reproduction, cellular component organization, and apoptosis, counting for two-thirds of total biological processes. However, none of these represent more than 10% of the total biological processes (Xu et al., 2015). These results suggest that protein degradation is a global event in OvCa tumors.

3.5. Chymotrypsin Activity From the Proteasome Subunit Is Likely the Major Contributor to the OvCa Peptidome

For peptides identified from OvCa samples, the most frequently observed amino acids at P1 position were Leu, Lys, and Phe (Fig. 4A). When normalized to the relative abundance of each amino acid within all human proteome, these amino acids were still the most common in the P1 position (Fig. 4B). Predominant amino acids at P1′ position of the cleavage sites were Leu, Val, Phe, Ala, and Ser (Fig. 4C and D). This suggests the involvement of chymotrypsin that preferentially cleaves proteins at Phe, Tyr, and Trp with high specificity and at Leu, Met, and His with lower specificity (Keil, 1992), for producing the OvCa peptidome peptides. Similar analyses of the residues performed for other sites (P2–6, P2–6′) suggest the involvement of other proteases such as enterokinase and pepsin (data not shown). The percentages of terminal and internal peptides in OvCa peptidome were also examined, and the results showed that 82% of the 5756 peptides were internal peptides while 17% were terminal ones. In addition, 54% of the peptides were within the length range of 3–23 amino acids.

Fig. 4.

Cleavage specificity analysis at P1 and P1′ sites for OvCa peptidome peptides.(A) Number of peptides undergoing cleavages is shown on the y-axis for all P1 amino acids. P1_Down, downstream P1 site on the peptides; P1_Up, upstream P1 site. (B) P1 amino acid frequency in (A) was adjusted to the relative abundance of each amino acid in all human proteins. Ratio of 1.0 indicates that corresponding amino acid present in the cleavage site has the same frequency in overall human protein amino acid composition, while >1.0 suggests an amino acid found more frequently in the cleavage site than elsewhere in the peptides. (C) As in (A) except for the P1′ position. (D) As in (B), except for the P1′ position. Modified with permission from Xu, Z., Wu, C., Xie, F., Slysz, G. W., Tolic, N., Monroe, M. E., et al. (2015). Comprehensive quantitative analysis of ovarian and breast cancer tumor peptidomes. Journal of Proteome Research, 14, 422–433, available at http://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/pr500840w. These figures are licensed under American Chemical Society (ACS) AuthorChoice, and further permission requests should be directed to the ACS.

One of the major intracellular protein degradation pathways is mediated by the proteasome, which generally cleaves proteins after hydrophobic residues by its chymotrypsin-like β5 subunit, and after basic residues by its trypsin-like β2 subunit (Voges, Zwickl, & Baumeister, 1999; Zwickl, Voges, & Baumeister, 1999). The length of the proteasomal cleavage products ranges from 3 to ~23 amino acid residues (Glickman & Ciechanover, 2002; Wenzel,Eckerskorn,Lottspeich,&Baumeister, 1994). In addition, proteasomal degradation is expected to produce a larger number of internal fragments, whereas the proteolytic products of other cytoplasmic proteases are terminal ones (Nixon et al., 1994). OvCa peptidome consisted of peptides rich in Leu, Lys, and Phe at P1 position, more than half of the peptides fell within the range of proteasome products, and the majority of which were internal peptides. These analyses suggest that the chymotrypsin activity, which is possibly from the proteasome subunit, is the major, but not the only, contributor to the OvCa peptidome.

We further examined the cleavage specificities of amino acid residues at the N-terminus and C-terminus of identified OvCa peptidome peptides. Ala and Ser were the most frequently observed amino acids at the starting position of the peptides, which were derived from N-terminus of precursor proteins with the first Met cleaved off; for the other N-terminal, all C-terminal, and overall peptidome peptides, no amino acid was observed with prominent frequency (data not shown). Based on the MEROPS database search (http://merops.sanger.ac.uk/index.shtml), an uncharacterized methionyl dipeptidase (Van Damme et al., 2009) (Met-Xaa dipeptidase) which most frequently cleaves Ala and Ser after Met matched the observed cleavage pattern, suggesting the involvement of N-terminal Methionine Excision (NME) in the generation of OvCa peptidome. In addition, ~51% of the Met at P1 position of all OvCa peptidome peptides was contributed by the NME process. Therefore, in addition to the contribution of proteasome subunit’s low chymotrypsin specificity for Met, NME process gives rise to the distinctive prevalence of Met at P1 position of all OvCa peptidome peptides (Fig. 4B).

NME is an important proteolytic pathway regulating the diversity of N-terminal amino acids of proteins, conserved from prokaryotes to eukaryotes. Although Met is the first amino acid of newly synthesized proteins, it is often removed from the mature proteins for nonbulky N-terminal residue to avoid immediate degradation by ubiquitin–proteasome system (Sherman, Stewart, & Tsunasawa, 1985). Besides being part of the protein maturing mechanism, recent data suggest that NME also serves to regulate protein’s half-life based on N-end rule at posttranslational level throughout development, tumorigenesis and in response to abiotic stress. For example, retained Met, Ser, Ala, Thr, Val, or Gly at N-terminus generally stabilize proteins for half-lives longer than 20h, while proteins with N-terminal Phe, Leu, Asp, Lys, or Arg have half-lives of 3min or less in mammals (Varshavsky, 1996). Therefore, NME is tightly regulated with other mechanisms including ubiquitin–proteasome pathway to determine the fate of proteins under various circumstances (Giglione, Boularot, & Meinnel, 2004). Our data revealed the prominent contribution of NME for the generation of OvCa tumor peptidome peptides. Based on the N-end rule, those proteins starting with nonbulky residues such as Ser, Ala, Thr, and Val are generally stabilized for longer half-lives instead of undergoing proteolytic process, suggesting that NME contributes possibly at translational level rather than serving as a switch for protein degradation at posttranslational level in OvCa tumor cells.

4. CONCLUSIONS

The study of low-molecular-weight bioreactive peptides, protein degradation products, and small intact proteins (i.e., the peptidome) is often criticized as being less sensitive, less reproducible, and as vulnerable to a lack of controls in sample collection and preparation (Fricker, Lim, Pan, & Che, 2006; Leichtle, Dufour, & Fiedler, 2013). Herein, we developed and evaluated a robust, efficient, and quantitative peptidomics platform and demonstrated its utility for in-depth characterization of the human ovarian tumor peptidome. Our study also indicates that warm ischemia effects are negligible up to 60min of postexcision delay in OvCa tumor peptidome, providing a basis for proper tumor specimen processing, handling, and selection for tumor peptidomics studies. Furthermore, we have shown that protein degradation is a global event in OvCa tumors, and that chymotrypsin and trypsin activities of proteasome subunits are the major contributors to the OvCa tumor peptidome. The observation that the cancer peptidome differs in a controlled, but unspecified, manner between the known subtypes of BrCa and between BrCa and OvCa (Xu et al., 2015) suggests that there are cancer-specific changes in the regulation of normal proteolytic processes. The observation that varying times of warm ischemia, from 0 to 60min, introduced less variability in the peptidome profile than that observed between subjects in actual clinical samples of OvCa suggests that these cancer-specific proteolytic process are tightly regulated, and not merely a nonspecific increase in protein degradation. These observations suggest that a more extensive and tightly controlled analysis of tumor peptidomes, including the use of normal control tissues and clinical metadata, has the potential to provide new and potentially useful insights regarding cancer biology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Portions of this work were supported by the Grant U24CA160019, from the National Cancer Institute Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC), National Institutes of Health Grant P41GM103493, and Department of Defense Interagency Agreement MIPR2DO89M2058. The experimental work described herein was performed in the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a national scientific user facility sponsored by the DOE and located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, which is operated by Battelle Memorial Institute for the DOE under Contract DE-AC05–76RL0 1830.

REFERENCES

- Boisvert FM, Ahmad Y, Gierlinski M, Charriere F, Lamont D, Scott M, et al. (2012). A quantitative spatial proteomics analysis of proteome turnover in human cells. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 11, M111 011429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha FM, Berti DA, Ferreira ZS, Klitzke CF, Markus RP, & Ferro ES (2008). Intracellular peptides as natural regulators of cell signaling. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283, 24448–24459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty MK, Hammond DE, Clague MJ, Gaskell SJ, & Beynon RJ (2009). Turnover of the human proteome: Determination of protein intracellular stability by dynamic SILAC. Journal of Proteome Research, 8, 104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler GM, Baumann S, Leichtle A, Oltmann A, Kase J, Thiery J, et al. (2007). Standardized peptidome profiling of human urine by magnetic bead separation and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clinical Chemistry, 53, 421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker LD, Gelman JS, Castro LM, Gozzo FC, & Ferro ES (2012). Peptidomic analysis of HEK293T cells: Effect of the proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin on intracellular peptides. Journal of Proteome Research, 11, 1981–1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker LD, Lim J, Pan H, & Che FY (2006). Peptidomics: Identification and quantification of endogenous peptides in neuroendocrine tissues. Mass Spectrometry Reviews, 25, 327–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman JS, Sironi J, Castro LM, Ferro ES, & Fricker LD (2011). Peptidomic analysis of human cell lines. Journal of Proteome Research, 10, 1583–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giglione C, Boularot A, & Meinnel T (2004). Protein N-terminal methionine excision.Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 61, 1455–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman MH, & Ciechanover A (2002). The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: Destruction for the sake of construction. Physiological Reviews, 82, 373–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman JD, Ma ZQ, & Tabb DL (2012). Identifying proteomic LC-MS/MS data sets with Bumbershoot and IDPicker. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics, 1–15, Chapter 13, Unit 13.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaitly N, Mayampurath A, Littlefield K, Adkins JN, Anderson GA, & Smith RD (2009). Decon2LS: An open-source software package for automated processing and visualization of high resolution mass spectrometry data. BMC Bioinformatics, 10, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil B (1992). Specificity of proteolysis. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, & Pevzner PA (2014). MS-GF+ makes progress towards a universal database search tool for proteomics. Nature Communications, 5, 5277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichtle AB, Dufour JF, & Fiedler GM (2013). Potentials and pitfalls of clinical peptidomics and metabolomics. Swiss Medical Weekly, 143, w13801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Sirotkin Y, Shen Y, Anderson G, Tsai YS, Ting YS, et al. (2012). Protein identification using top-down. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 11, M111 008524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Otin C, & Overall CM (2002). Protease degradomics: A new challenge for proteomics. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology, 3, 509–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertins P, Yang F, Liu T, Mani DR, Petyuk VA, Gillette MA, et al. (2014). Ischemia in tumors induces early and sustained phosphorylation changes in stress kinase pathways but does not affect global protein levels. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 13, 1690–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RA, Saito KI, Grynspan F, Griffin WR, Katayama S, Honda T, et al. (1994). Calcium-activated neutral proteinase (calpain) system in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 747, 77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter I, & Berger A (1968). On the active site of proteases. 3. Mapping the active site of papain; specific peptide inhibitors of papain. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 32, 898–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahinian H, Loessner D, Biniossek ML, Kizhakkedathu JN, Clements JA, Magdolen V, et al. (2013). Secretome and degradome profiling shows that Kallikrein-related peptidases 4, 5, 6, and 7 induce TGFbeta-1 signaling in ovarian cancer cells. Molecular Oncology, 8, 68–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Liu T, Tolic N, Petritis BO, Zhao R, Moore RJ, et al. (2010). Strategy for degradomic-peptidomic analysis of human blood plasma. Journal of Proteome Research, 9, 2339–2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Tolic N, Liu T, Zhao R, Petritis BO, Gritsenko MA, et al. (2010). Blood peptidome-degradome profile of breast cancer. PLoS One, 5, e13133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F, Stewart JW, & Tsunasawa S (1985). Methionine or not methionine at the beginning of a protein. BioEssays, 3, 27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slysz GW, Steinke L, Ward DM, Klatt CG, Clauss TR, Purvine SO, et al. (2014). Automated data extraction from in situ protein-stable isotope probing studies. Journal of Proteome Research, 13, 1200–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RD, Anderson GA, Lipton MS, Pasa-Tolic L, Shen Y, Conrads TP, et al. (2002). An accurate mass tag strategy for quantitative and high-throughput proteome measurements. Proteomics, 2, 513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinoco AD, & Saghatelian A (2011). Investigating endogenous peptides and peptidases using peptidomics. Biochemistry, 50, 7447–7461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme P, Maurer-Stroh S, Plasman K, Van Durme J, Colaert N, Timmerman E, et al. (2009). Analysis of protein processing by N-terminal proteomics reveals novel species-specific substrate determinants of granzyme B orthologs. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 8, 258–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshavsky A (1996). The N-end rule: Functions, mysteries, uses. Proceedings of the NationalAcademy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93, 12142–12149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva J, Shaffer DR, Philip J, Chaparro CA, Erdjument-Bromage H, Olshen AB, et al. (2006). Differential exoprotease activities confer tumor-specific serum peptidome patterns. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 116, 271–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voges D, Zwickl P, & Baumeister W (1999). The 26S proteasome: A molecular machine designed for controlled proteolysis. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 68, 1015–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel T, Eckerskorn C, Lottspeich F, & Baumeister W (1994). Existence of a molecular ruler in proteasomes suggested by analysis of degradation products. FEBS Letters, 349, 205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Monroe ME, Xu Z, Slysz GW, Payne SH, Rodland KD, et al. (2015). An optimized informatics pipeline for mass spectrometry-based peptidomics. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 26, 2002–2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Wu C, Xie F, Slysz GW, Tolic N, Monroe ME, et al. (2015). Comprehensive quantitative analysis of ovarian and breast cancer tumor peptidomes. Journal of Proteome Research, 14, 422–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, & Desiderio DM (1993). Methionine enkephalin-like immunoreactivity, substance P-like immunoreactivity and beta-endorphin-like immunoreactivity postmortem stability in rat pituitary. Journal of Chromatography, 616, 175–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer JS, Monroe ME, Qian WJ, & Smith RD (2006). Advances in proteomics data analysis and display using an accurate mass and time tag approach. Mass Spectrometry Reviews, 25, 450–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwickl P, Voges D, & Baumeister W (1999). The proteasome: A macromolecular assembly designed for controlled proteolysis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 354, 1501–1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]